Abstract

A Th1 immune response involving gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production is required to eliminate Chlamydophila abortus infections. In this study, the role of interleukin-12 (IL-12) in protecting against C. abortus infection was investigated using IL-12−/− and wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice to determine the role of this Th1-promoting cytokine. IL-12−/− mice were able to eliminate the C. abortus infection in a primary infection. However, there was a delay in the clearance of bacteria when IL-12−/− mice were infected with a sublethal dose of C. abortus, the delay being associated with a lower production of IFN-γ. The low level of IFN-γ was essential for survival of IL-12−/− infected mice. Both WT and IL-12−/− mice developed a Th1 immune response against C. abortus infection, since they both produced IFN-γ and immunoglobulin G2a antibody isotype. In addition, when mice were given a secondary infectious challenge with C. abortus, a protective host response which resolved the secondary infection was developed by both WT and IL-12−/− mice. The lack of IL-12 resulted in few infiltrating CD4+ T cells in the liver relative to the number in WT mice, although the number of CD8+ T cells was slightly higher. The more intense Th1 response presented by WT mice may have a pathogenic effect, as the animals showed higher morbidity after the infection. In conclusion, these results suggest that although IL-12 expedites the clearance of C. abortus infection, this cytokine is not essential for the establishment of a protective host response against the infection.

Chlamydophila abortus (Chlamydia psittaci serotype 1) is a gram-negative intracellular bacterium that replicates in cell phagosomes, thus preventing their fusion with lysosomes (12). This bacterium, which has been recorded worldwide, is the etiologic agent of enzootic abortion in small ruminants, infecting the placenta and causing abortion during the last trimester of gestation (35). In addition to the economic losses it causes, this pathogen also represents a potential zoonotic risk for pregnant women (7).

Mouse models have been widely used to study the pathogenesis and immune response to chlamydial infections. Mice experimentally infected with the bacteria show a fever syndrome followed by abortion. This syndrome is similar to that presented in the natural infection of chlamydial abortion in humans and small ruminants. The host response is immediately activated in organs such as the liver and the spleen. Meanwhile, the bacteria replicate in the placenta, which is an immunocompromised organ (6). Although innate immune mechanisms, especially neutrophils, play an important role (3), chlamydial infection is ultimately controlled by a specific Th1 immune response characterized by the production of high levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and the presence of T cells, particularly CD8+ T cells (5, 9, 11, 25, 26). However, the mechanisms involved in the development of this cellular immune response have been poorly studied in C. abortus infection. In murine experimental infections with other species of the family Chlamydiaceae, such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydophila pneumoniae, this response has been defined, at least in part, as being interleukin-12 (IL-12)-dependent (15, 21). We have recently reported that IL-12 is produced early during C. abortus infection (5), and it has been reported that treatment with exogenous IL-12 confers immediate and long-term protection in susceptible BALB/c mice intranasally infected with C. abortus (17).

IL-12 is a heterodimeric cytokine, which is produced primarily by phagocytic cells and dendritic cells in response to infections caused by intracellular pathogens such as bacteria (19, 39), fungi (10, 23), protozoa (1, 14), and viruses (24, 28). It has been reported that IL-12 increases NK cell and T-lymphocyte cytotoxic activity, favors Th1 differentiation, and triggers the production of IFN-γ and other proinflammatory cytokines (22, 41). However, some recent findings point to a more complicated picture, the role of IL-12 in the immune response to certain intracellular pathogens seeming to be ambiguous. Indeed, this cytokine has both protective and pathogenic functions in infections with species such as Plasmodium (43, 44) and Leishmania (37). Furthermore, in the host response to some virus infections, a Th1 response was established in the absence of IL-12. This response was characterized by both T-cell IFN-γ release and immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) production (29, 42).

The aim of this study, therefore, was to further define the role of endogenous IL-12 in host resistance against C. abortus infection. For this purpose, we used wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice, a strain that is relatively resistant to chlamydial infection (8), and IL-12 p40-deficient mice (IL-12−/−) to assess the IL-12-mediated mechanisms that control the primary replication of the bacteria in the immune response to C. abortus infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Eight-week-old female C57BL/6J (H-2b) mice and IL-12 p40-deficient (IL-12−/−) mice were purchased from Harlan UK Limited (Blackthorn, England) and Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine), respectively. They were free of common viral and bacterial pathogens, as determined by routine screening procedures performed by the suppliers.

Microorganisms and infection.

Mice were infected with the abortion-causing C. abortus strain AB7, isolated from an ovine abortion (34). The bacteria were propagated in the yolk sacs of developing chicken embryos and titrated by enumerating inclusion-forming units (IFUs) on McCoy cells, as described by Buendía et al. (3). Standardized aliquots were frozen at −80°C until used.

WT and IL-12−/− mice were challenged by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with 106 IFUs of C. abortus in 0.1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2), 0.1 M. For each experiment, a group of mice of each strain were inoculated with 0.1 ml of sterile PBS as a noninfected control.

At 4, 10, and 16 days postinfection (p.i.), mice of each strain were killed, and samples of liver, spleen, and serum were collected under aseptic conditions. Additional infected mice of each strain were killed on day 42 p.i. to measure the concentrations of IgG isotypes in serum. To study the immune response to secondary infection, WT and IL-12−/− mice were given a secondary challenge of 106 IFUs 6 weeks after a first challenge with 106 IFUs. These mice were killed 1 and 3 days after the secondary infectious challenge, and samples of liver, spleen, and serum were removed.

Isolation of C. abortus from spleen and liver.

The course of infection was evaluated by counting IFUs from the spleen and the liver after isolation of C. abortus on McCoy cell monolayers, the method previously described by Buendía et al. (3). The cranial portion of the spleen and one lobe of the liver were examined, and the number of IFUs per gram was calculated. The detection limit was 2.6 log IFUs per sample.

Liver histopathology.

Samples of livers from WT and IL-12−/− mice were collected and fixed in 10% formalin in PBS, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin wax at 56°C. Sections (5-μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin-eosin for histopathologic evaluation of qualitative aspects of liver infection. In the evaluation of liver pathology, inflammatory circular lesions formed by leukocytes were considered infectious foci. The number of foci was counted in 20 fields (8,500 μm2/field) of every section of liver tissue.

Phenotypic characterization of immune response in liver.

Liver samples were snapfrozen with 2-methylbutane cooled with liquid nitrogen for immunophenotypical characterization of the cellular infiltrate, as previously described (26). Cryosections (5-μm thick) were treated with an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex technique, and rat monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against mouse leukocyte antigens were used as primary antibodies. Anti-CD4 (clone CT-CD4) and anti-CD8 (clone CT-CD8) MAbs were purchased from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, Calif.). A goat biotinylated anti-rat Ig mouse-adsorbed polyclonal antibody (Caltag) was used as the secondary antibody. CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte subpopulations were determined in 20 fields (17,000 μm2/field) from sections of the same lobe of the liver for each mouse.

Spleen cell culture.

The caudal half of the spleens taken from mice was ground through a sieve with a 100-μm mesh, depleted of erythrocytes by ammonium chloride treatment, and washed with RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland). After the cells were counted, 5 × 105 cells/ml were resuspended in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco), 200 mM l-glutamine, and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol with 2.5 μg of fungizone, 100 IU of penicillin, and 10 μg of streptomycin per ml (all from Sigma, Madrid, Spain), and plated at 1 ml/well in 24-well plates (Corning, Cambridge, Mass.). For specific activation, elementary bodies (EB) of C. abortus (50 μg/ml) purified on a Urografin (Schering, Madrid, Spain) gradient as previously described (4) were added. In order to compare the nonspecific activation of lymphocytes, 5 μg of concanavalin A (ConA) (Sigma) per ml was added. Incubation was performed for 48 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Cytokine analysis.

IFN-γ concentrations were determined in serum and in splenocyte culture supernatants. A sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocol described in the PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.) catalogue was used for measuring this cytokine. The capture antibody was R4-6A2, and the biotinylated detection antibody was XMG1.2. All antibodies were purchased from PharMingen. Biotin-conjugated antibody was detected with a horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin conjugate (PharMingen) and a soluble substrate, ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid); Sigma]. The optical density was read at 450 nm. Culture supernatants were also assayed for IL-4 using an ELISA kit (Endogen Inc., Woburn, Mass.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. IL-18 was detected in serum by an ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). The levels of cytokines were expressed in nanograms per milliliter.

Evaluation of IgG isotypes in serum.

Sera from five infected mice of each strain were collected at 42 days p.i. and stored at −20°C until examined by ELISA for IgG1 and IgG2a responses as previously described (11). The titer for individual mice was taken as the highest serum dilution with an optical density value greater than the means + 3 standard deviations for sera from five noninfected mice.

In vivo IFN-γ neutralization.

Anti-mouse IFN-γ hybridoma (XMG-6) was a gift from Eric Y. Denkers (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.). Hybridoma cells were grown at high density in an MAb production kit (Diagnostic Chemicals Limited, Oxford, Conn.). The antibody-containing medium was recovered and sterile filtered, and the MAb was purified. The MAb was administered to WT and IL-12−/− mice by intravenous injection 24 h before infection, at the time of infection, and 3 days p.i. at a dose of 0.4 mg. A group of mice were injected with rat IgG as a control group. Another group of noninfected mice received the XMG-6 MAb treatment. Mice were i.p. infected with 106 IFUs of C. abortus in 0.1 ml of PBS and killed at 4 and 10 days p.i.

Statistical analysis.

Evaluation of statistical differences between data obtained from WT and mutant mice was performed by the two-tailed Student's t test. A probability (P) value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

IL-12 KO mice clear C. abortus infection and display lower disease morbidity.

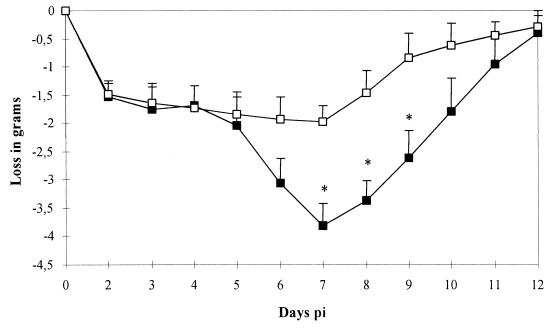

IL-12−/− and parental WT mice were infected with a sublethal dose of 106 IFUs of C. abortus strain AB7. In comparison with IL-12−/− mice, the WT mice exhibited higher morbidity, especially between days 6 and 9 p.i., as determined by more acute signs of sickness, including lethargy, ruffled fur, lack of alertness, weakness, and a more pronounced decrease in body weight (Fig. 1). These symptoms were still present at day 8 p.i., although after this date WT mice started to resolve the syndrome with a slow recovery in body weight until there were no symptoms at day 10 p.i. In contrast, infected IL-12−/− mice showed almost no signs of acute disease. When mice were infected with a potentially lethal dose (107 IFUs/mouse), WT mice showed 60% mortality, while IL-12−/− mice showed only 25% mortality after 16 days p.i. (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of C. abortus infection on weight loss of C57BL/6 (WT) mice (■) and IL-12−/− mice (□). Groups of 10 mice were infected with a challenge dose of 106 IFUs of C. abortus, and body weight was monitored daily. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. ∗, statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

The lower morbidity rate was not associated with more effective elimination of the bacteria. In the spleen, the level of infection at 4 days p.i. was similar in WT and IL-12−/− mice (Table 1). However, at 10 days p.i., there were still 4.24 ± 0.07 log IFUs/g in the spleen of IL-12−/− mice, while the bacterial level was below the level of detection (2.6 log IFUs) in WT mice at this time. In the liver, although knockout (KO) mice always showed a higher level of infection than WT mice, the differences were not significant at either 4 or 10 days p.i. (Table 1). Although bacterial clearance seemed to be more effective in WT mice, no bacteria were detected in the spleen or the liver of IL-12−/− mice at 16 days p.i. Thus, even in the absence of IL-12, these mice were able to resolve the infection, although with slightly delayed kinetics compared to WT mice.

TABLE 1.

Bacteria in spleen and liver of C57BL/6 (WT) and IL-12−/− infected mice after isolation of C. abortusa

| Days p.i. | Mean log IFUs/g ± SD

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen

|

Liver

|

|||

| WT | IL-12−/− | WT | IL-12−/− | |

| 4 | 7.86 ± 0.11 | 7.90 ± 0.21 | 7.16 ± 0.03 | 7.32 ± 0.08 |

| 10 | <2.6 | 4.24 ± 0.17* | 4.25 ± 0.29 | 4.97 ± 0.70* |

| 16 | <2.6 | <2.6 | <2.6 | <2.6 |

Mice were injected i.p. with 106 IFUs of C. abortus in 0.1 ml of PBS. At the indicated time points, groups of five were sacrificed, and samples of liver and spleen were taken. After isolation on McCoy cell monolayers, the number of inclusions was determined by indirect immunofluorescence, and results are expressed as the log of the means ± standard deviations. Results are from one representative experiment of three independent experiments. *, statistically significant difference between WT and IL-12−/− mice (P > 0.05).

In the absence of IL-12, C. abortus induces diminished IFN-γ production without a concomitant increased Th2 response.

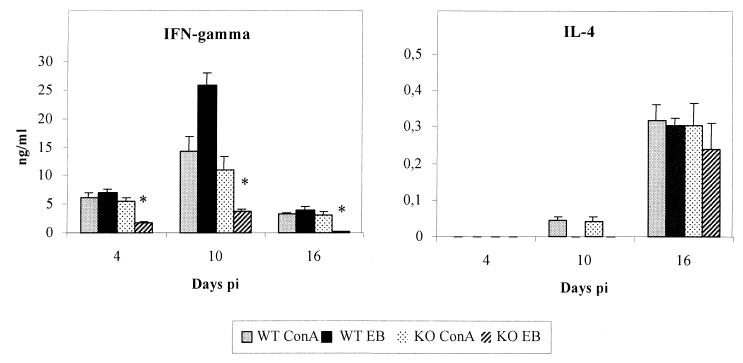

IL-12 is a cytokine that enhances IFN-γ production, and it is believed to play an important role in specific immunity by promoting Th1 cell differentiation. In our experiment, spleen cells were stimulated with purified EB of C. abortus or ConA, and IFN-γ and IL-4 production was determined in cell culture supernatants. When splenocytes were stimulated with EB, IFN-γ production was detected in the splenocyte cultures of WT infected mice, with the highest levels being observed on day 10 p.i. (Fig. 2). IFN-γ production was present but significantly diminished in infected IL-12−/− mice. The maximum level was reached at day 10 but was eightfold lower than in WT mice. When cells were stimulated with ConA, the differences were not significant between the two strains of mice. These data show that the differences in in vitro cytokine production are due to differences in the antigen-specific response and not to general differences in T-cell responsiveness. In both KO and WT infected mice, IL-4 production in cultured spleen cells stimulated with EB did not exceed background levels (30 pg/ml) during the first 2 weeks of infection. After 16 days p.i., the level of this cytokine was similar in both WT and IL-12−/− mice. When cells were cultured in medium without EB or ConA, neither IFN-γ nor IL-4 was detected. Serum IFN-γ was only detected on day 4 p.i. in both groups of mice. As above, the level in WT mice was much higher than in IL-12−/− mice (65.84 ± 5.64 and 1.20 ± 0.18 ng/ml, respectively). Serum IFN-γ levels returned to baseline levels on day 10 p.i. for both KO and WT mice.

FIG. 2.

IFN-γ and IL-4 production in spleen cells of C. abortus-infected C57BL/6 (WT) and IL-12−/− (KO) mice. Spleen cells were stimulated with ConA (5 μg/ml) and purified EB of C. abortus (50 μg/ml), and the presence of IFN-γ and IL-4 in cell culture supernatants was determined 48 h later. The results are the means and standard deviation for five mice. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. Cytokine production in spleen cells from noninfected mice was below the detection limit (<50 pg/ml for IFN-γ and <30 pg/ml for IL-4). ∗, statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in the production of IFN-γ between WT mice and IL-12−/− mice when cells were stimulated with EB.

IFN-γ is the major cytokine which promotes antibody class switching to the IgG2a isotype. Though the antibody levels were very low in the sera from infected mice, we found similar levels of the two IgG isotypes IgG1 and IgG2a in both mutant and WT mice. However, the titer of IgG2a was always higher than that of IgG1 in both groups of mice (1:200 for IgG2a and 1:50 for IgG1).

IL-12-deficient mice display delayed formation of inflammatory foci and a diminished number of CD4+ T cells in the liver.

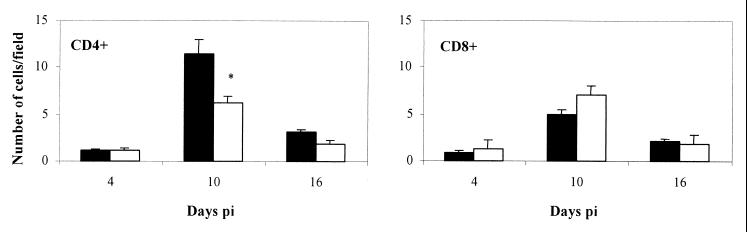

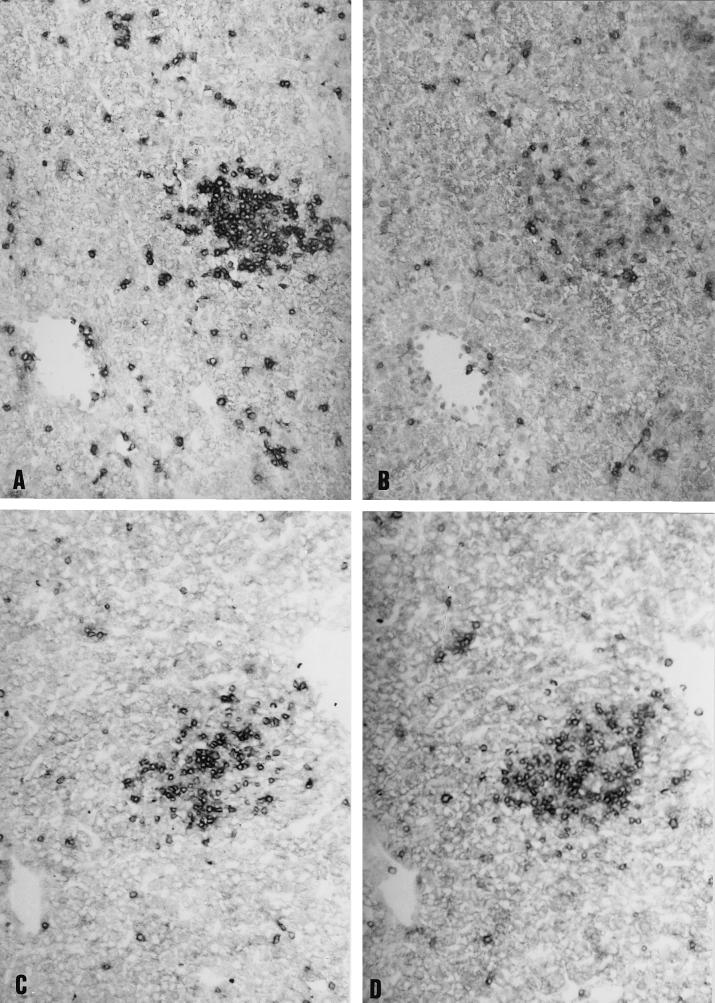

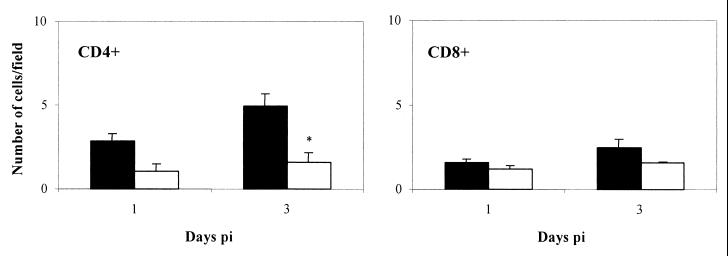

The liver is a primary target organ for the replication of C. abortus in a systemic infection (6). Characteristic lesions include perifocal hepatitis with inflammatory foci composed of leukocytes surrounding infected cells (3, 5). For this reason the liver was selected for histopathological analysis and the in situ characterization of leukocyte subpopulations. At day 4 p.i., WT mice showed a higher number of inflammatory foci (1.23 ± 0.2/field) than the IL-12−/− mice (0.72 ± 0.1/field). In both mutant and WT mice, these foci were composed mainly of neutrophils, with some macrophages and very few lymphocytes. No differences in the number of foci between WT and IL-12−/− mice were found at 10 days p.i. (data not shown). At this time, in situ phenotypic characterization of the lymphocyte subpopulations showed a significantly higher number of CD4+ T cells both in the foci and infiltrating the parenchyma in WT than in IL-12−/− mice (Fig. 3 and 4). On the contrary, the number of CD8+ T cells was higher in the inflammatory foci of IL-12−/− mice, although not to a statistically significant extent (Fig. 3 and 4). At day 16 p.i., most of the foci had disappeared, and those remaining were very small. There was a corresponding decrease in the number of T cells in the remaining foci (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in liver sections of WT mice (■) and IL-12−/− mice (□) after i.p. inoculation of 106 IFUs of C. abortus. Adjacent liver sections were labeled for CD4+ and CD8+ cells. The number of cells was counted in 20 fields (17,000 μm2/field) of every liver section. The results are the means and standard deviation for five mice. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. ∗, statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

FIG. 4.

Immunophenotypic characterization of liver T cells from C57BL/6 (WT) and IL-12−/− mice during C. abortus infection. Adjacent liver sections from WT (A and B) and IL-12−/− (C and D) mice were labeled for CD4+ (A and C) and CD8+ (B and D) T cells. Note that CD4+ cells were more numerous in WT mice (A) than in IL-12−/− mice (C), although there were more CD8+ cells in IL-12−/− mice (D) than in WT mice (B). Magnification, ×200.

IL-12 is not necessary for resolving a secondary infectious challenge.

To further assess the role of IL-12 in the protective response, we determined the ability of IL-12−/− mice to clear C. abortus during a secondary immune response. Mutant and WT mice were immunized with a sublethal dose of C. abortus (106 IFUs) to allow complete elimination of bacteria by 6 weeks after infection. Mice were then infected with the same dose, 106 IFUs. At 3 days p.i., no symptoms were shown by WT or IL-12−/− mice. Furthermore, the number of bacteria in the spleen of infected mice indicated a titer below the detection limit (2.6 log IFUs) in both WT and IL-12-deficient mice, indicating efficient immunity to the secondary challenge of C. abortus even in the absence of IL-12.

To determine the level of cytokines during the secondary immune response, spleen cells were stimulated with EB or ConA, and IFN-γ and IL-4 production was determined in cell culture supernatants. As in primary infection, IFN-γ production was significantly higher in WT than in IL-12−/− lymphocytes at 3 days p.i. (52.71 ± 6.85 and 3.85 ± 0.53 ng/ml, respectively) when they were stimulated with EB. Whereas IL-4 levels were below the detection limit in the WT mice (<30 pg/ml), some production of IL-4 was detected in IL-12−/− splenocytes (96 ± 14 pg/ml) 3 days after the secondary infectious challenge. When cytokines were detected in serum, the IFN-γ level at 1 day after the secondary challenge was again much higher in the WT mice than in IL-12−/− mice (53.52 ± 7.99 and 6.45 ± 1.06 ng/ml, respectively), returning to baseline levels 2 days later.

Histopathological analysis showed very mild perifocal hepatitis in the liver of both WT and KO mice, with small inflammatory foci and a perivascular lymphocyte infiltrate. At 3 days after secondary challenge, there was a significantly higher number of CD4+ T cells in WT mice than in IL-12−/− mice (Fig. 5). The number of CD8+ T cells increased very slightly during secondary infection. The inflammatory foci disappeared in subsequent days, and the number of T cells quickly returned to baseline values (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Immunophenotypic characterization of liver T cells from WT (■) and IL-12−/− (□) mice after a secondary infectious challenge with 106 IFUs of C. abortus. Adjacent liver sections were immunolabeled for CD4+ and CD8+ cells. Cell number was counted in 20 fields (17,000 μm2/field) of every liver section. The results are the means and standard deviation for five mice. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. ∗, statistically significant difference (P < 0.05).

C. abortus infection induces production of IL-18.

IL-18 is a cytokine that shares many functions with IL-12, and the two cytokines can operate synergistically (2). Thus, IL-18 is a possible candidate for the production of IL-12-independent IFN-γ and, hence, for the development of a protective response in IL-12−/− mice. We have analyzed the levels of IL-18 in the serum of infected mice to determine the presence of this cytokine during primary and secondary infection. Our results demonstrated that C. abortus infection induced the production of IL-18. Although IL-18 levels were higher in mutant mice than in WT mice in the early stages of infection, (5.38 ± 1.21 and 3.66 ± 0.85 ng/ml, respectively, at day 4 p.i.) no statistical differences were found at any time point investigated. After a secondary infectious challenge, the level of IL-18 was again slightly higher in IL-12−/− mice than in WT mice (4.46 ± 1.08 and 1.68 ± 0.47 ng/ml, respectively), but there were no significant differences between the two groups of mice (data not shown).

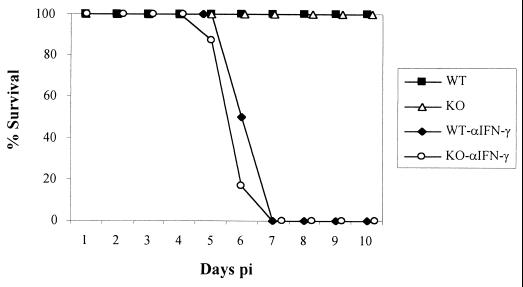

IL-12-independent IFN-γ is necessary to resolve infection.

As shown above, infected IL-12−/− mice produced a very low level of IFN-γ compared to WT mice at the beginning of the infection. To address the importance of this IL-12-independent IFN-γ in the development of a protective response, IFN-γ was neutralized in WT and IL-12−/− mice. In the absence of IFN-γ, all infected WT and KO mice showed acute signs of illness starting at 2 days p.i., and all mice died 5 to 6 days p.i. (Fig. 6). The level of infection in the liver at 4 days p.i. was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in neutralized KO and neutralized WT mice (8.36 ± 0.04 and 7.99 ± 0.05 log IFUs/g, respectively) than in nonneutralized KO and WT mice (7.23 ± 0.08 and 7.12 ± 0.03 log IFUs/g, respectively). There was no significant differences in the number of bacteria isolated from the spleen of IFN-γ-neutralized and nonneutralized mice (data not shown). These data support the concept that in the absence of IL-12, alternative mechanisms of generating IL-12-independent IFN-γ are essential for the establishment of a protective immune response against C. abortus infection.

FIG. 6.

Survival of WT and IL-12−/− mice given anti-IFN-γ MAb (XMG-6). Groups of six mice were infected with 106 IFUs of C. abortus. The MAb was administered to WT and IL-12−/− mice 24 h before infection, at the time of infection, and 3 days p.i. Mice were monitored dairy, and mortality rates were calculated.

DISCUSSION

In this study we used IL-12-deficient mice to determine whether the absence of IL-12, widely regarded as the initiation cytokine for Th1-cell-mediated immunity (38), alters the course of a C. abortus infection. We found that resistance, as measured by bacterial load, is related to the presence of IL-12, since WT mice had a lower bacterial level in the liver and resolved the spleen infection earlier than IL-12−/− mice. The inflammatory foci in the liver appeared earlier and in higher numbers in WT mice than in IL-12−/− mice. These foci were composed mainly of neutrophils, which may provide a first line of defense against C. abortus, as demonstrated in previous studies (3, 26). In line with this, the earlier inflammatory response that developed in WT mice may be related to the chemotactic role of IL-12 for leukocytes (16, 30, 31).

Importantly, despite a slight increase in susceptibility, we have demonstrated that IL-12−/− mice were able to clear bacteria from the spleen and the liver in the first 2 weeks after infection. This is in contrast to the findings of studies on Chlamydia trachomatis infection, where IL-12-neutralized mice could not clear bacteria even 20 days after control mice had done so (33), or C. pneumoniae infection, where IL-12−/− mice were not able to clear bacteria from the lungs even by 60 days p.i. (36). Our data indicate that although IL-12 clearly plays a role in the establishment of an early Th1 response in the WT mice, mutant mice developed a residual IFN-γ production. This residual IFN-γ present in the IL-12−/− mice might be sufficient to induce the host response and hence might contribute to the elimination of the bacteria. When IFN-γ was neutralized, both WT and mutant mice died at 6 days p.i. and the number of bacteria at 4 days p.i. was 10-fold higher than in nontreated mice. This result confirms that the low level of IFN-γ present in IL-12−/− mice is essential for the survival of the animals. The crucial role of IFN-γ in the host response against C. abortus infection has been described previously (25). Perry et al. (32) found that host resistance following genital infection with serovar D of C. trachomatis was independent of IL-12. The infection was early controlled by local IFN-γ, presumably produced by cells of the innate immune system. In our study, the low IFN-γ level detected in the absence of IL-12 was enough to reduce the C. abortus burden, and it was followed by an influx of CD8+ cells in the inflammatory foci that, we hypothesize, could complete the clearance of the infection. Indeed, previous studies have shown the important role of CD8+ T cells for the host response to C. abortus infection (5, 9, 11).

In our study there were no differences in the production of IL-4 between WT and KO mice. This is in accord with recent studies in which IL-12-deficient BALB/c mice but not C57BL/6 mice secreted elevated levels of IL-4 under conditions inducing Th1 development in WT mice (13). Related to this, in studies of Cryptococcus infection, IL-12-deficient mice showed an increased susceptibility to the infection partly associated with a polarized Th2 response (10). In our study, IL-4 was detected at the same time that the infection came under control in both WT and deficient mice, but follow-up studies will be necessary to assess the role of this cytokine in C. abortus infection.

When mice were given a secondary infectious challenge with C. abortus, no differences between IL-12−/− mice and WT mice were found with regard to resolution of the secondary infection. Therefore, IL-12 seems to be dispensable for developing an efficient immune response to secondary C. abortus infection. Similarly, other authors have reported a limited role of IL-12 in secondary infection of mice undergoing pulmonary infection with C. abortus (17).

Since the above results indicated the presence of mechanisms to compensate for lack of IL-12, we investigated the production of IL-18. It was found that C. abortus infection induces production of IL-18. The exact role of this cytokine in C. abortus infection remains to be investigated, although it has been identified as a factor showing potent IFN-γ-inducing activity (18), compensating for some of the functional activities of IL-12 (39), and acting synergistically with IL-12 (27).

We found that a high level of this cytokine was also responsible for inducing massive neutrophil infiltration and hepatic necrosis (unpublished data). In other studies of the host response against Leishmania donovani, it was shown that although IL-12 has a role in protective immunity, it induces hepatic immunopathology (37). It has also been reported that IL-12 and IFN-γ are involved in the pathogenesis of liver injury in infections with Plasmodium berghei (44). The pathogenic role of an exacerbated Th1 response could be especially important for the case of abortion-causing intracellular pathogens, such as C. abortus. Other authors have reported that high production of IFN-γ, beneficial for eliminating microbial infection, can adversely affect pregnancy outcome (20). Future studies would be necessary to address the effect of a reduced IFN-γ level in pregnancy using IL-12 inhibitors.

Taken together, the present results suggest that IL-12 is not essential for the establishment of a host response to control C. abortus infection. Although expediting the early clearance of the bacteria, it may be involved in the pathology associated with the infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Y. Denkers for the generous gift of XMG-6 hybridoma cells and critical review of the manuscript.

This work was partially supported by Comisión Interministeral de Ciencia y Tecnología (CICYT) grant AGF97-0459 and by European Comission (FEDER) grant 1FD97-1242-CO2-01. L. Del Río was the recipient of a predoctoral grant from Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Spain. A. J. Buendía was the recipient of a postdoctoral grant from CajaMurcia, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baszler T V, Long M T, McElwain T F, Mathison B A. Interferon-γ and interleukin-12 mediate protection to acute Neospora caninum infection in BALB/c mice. Int J Parasitol. 1999;29:1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(99)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohn E, Sing A, Zumbihl R, Bielfeldt C, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Heeseman J, Autenrieth I B. IL-18 (IFN-γ-inducing factor) regulates early cytokine production in, and promotes resolution of, bacterial infections in mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buendía A J, Montes de Oca R, Navarro J A, Sánchez J, Cuello F, Salinas J. Role of polymorphonuclear neutrophils in a murine model of Chlamydia psittaci-induced abortion. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2110–2116. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2110-2116.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buendía A J, Salinas J, Sánchez J, Gallego M C, Rodolakis A, Cuello F. Localization by immunoelectron microscopy of antigens of Chlamydia psittaci suitable for diagnosis or vaccine development. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buendía A J, Sánchez J, Del Río L, Garcés B, Gallego M C, Caro M R, Bernabé A, Salinas J. Differences in the immune response against ruminant chlamydial strains in a murine model. Vet Res. 1999;30:495–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buendía A J, Sánchez J, Martínez M C, Cámara P, Navarro J A, Rodolakis A, Salinas J. Kinetics of infection and effects on placental cell populations in a murine model of Chlamydia psittaci-induced abortion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2128–2134. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2128-2134.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buxton D, Henderson D. Infectious abortion in sheep. In Practice. 1999;21:360–368. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buzoni-Gatel D, Bernard F, Pla M, Rodolakis A, Lantier F. Role of H-2 and non-H-2 related genes in mouse susceptibility to Chlamydia psittaci. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:229–233. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buzoni-Gatel D, Guilloteau L, Bernard F, Chardes T, Rocca A. Protection against Chlamydia psittaci in mice conferred by Lyt-2+ cells. Immunology. 1992;77:284–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decken K, Köhler G, Palmer-Lehmann K, Wunderlin A, Mattner F, Magram J, Gately M K, Alber G. Interleukin-12 is essential for a protective Th-1 response in mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4994–5000. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4994-5000.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Rio L, Buendía A J, Sánchez J, Garcés B, Caro M R, Gallego M C, Bernabé A, Cuello F, Salinas J. Chlamydophila abortus (Chlamydia psittaci serotype 1) clearance is associated with the early recruitment of neutrophils and CD8+ T cells in a mouse model. J Comp Pathol. 2000;123:171–181. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2000.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everett K D, Bush R M, Andersen A A. Emended description of the order Chlamydiales, proposal of Parachlamydiaceae fam. nov. and Simkaniaceae fam. nov., each containing one monotypic genus, revised taxonomy of the family Chlamydiaceae, including a new genus and five new species, and standards for the identification of organisms. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:415–440. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galbiati F, Rogge L, Adorini L. IL-12 receptor regulation in IL-12-deficient BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:29–37. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<29::AID-IMMU29>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gazzinelli R T, Wysocka M, Hayashi S, Denkers E Y, Hieny S, Caspar P, Trinchieri G, Sher A. Parasite-induced IL-12 stimulates early IFN-gamma syntesis and resistance during acute infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1994;153:798–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geng Y, Berencsi K, Gyulai Z, Valyi-Nagy T, Gonczol E, Trinchieri G. Roles of interleukin-12 and gamma interferon in murine Chlamydia pneumoniae infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2245–2253. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2245-2253.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha S J, Lee C H, Lee S B, Kim C M, Jang K L, Shin H S, Sung Y C. A novel function of IL-12p40 as a chemotactic molecule for macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;163:2902–2908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, Wang M, Lenz S, Gao D, Kaltenboeck B. IL-12 administered during Chlamydia psittaci lung infection in mice confers immediate and long-term protection and reduces macrophage inflammatory protein-2 level and neutrophil infiltration in lung tissue. J Immunol. 1999;162:2217–2226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawakami K, Koguchi Y, Qureshi M H, Miyazato A, Yara S, Kinjo Y, Iwakura Y, Takeda K, Akira S, Kurimoto M, Saito A. IL-18 contributes to host resistance against infection with Cryptococcus neoformans in mice with defective IL-12 synthesis through induction of IFN-gamma production by NK cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:941–947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kincy-Cain T, Clements J D, Bost K L. Endogenous and exogenous IL-12 augment the protective immune response in mice orally challenged with Salmonella dublin. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1437–1440. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1437-1440.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krishnan L, Guilbert L J, Wegmann T G, Belosevic M, Mosmann T R. T helper 1 response against Leishmania major in pregnant C57BL/6 mice increases implantation failure and fetal resorptions. Correlation with increased IFN-gamma and TNF and reduced IL-10 production by placental cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:653–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu H, Zhong G. Interleukin-12 production is required for chlamydial antigen-pulsed dendritic cells to induce protection against live Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1763–1769. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1763-1769.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macatonia S E, Hosken N A, Litton M, Vieira P, Hsieh C S, Culpepper J A, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Murphy K M, O'Garra A. Dendritic cells produce IL-12 and direct the development of Th1 cells from naive CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:5071–5079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magee D M, Cox R A. Interleukin-12 regulation of host defenses against Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3609–3613. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3609-3613.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuo R, Kobayashi M, Herndon D N, Pollard R B, Suzuki F. IL-12 protects thermally injured mice from herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;59:623–630. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.5.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCafferty M C, Maley S W, Entrican G, Buxton D. The importance of interferon-γ in an early infection of Chlamydia psittaci in mice. Immunology. 1994;81:631–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montes de Oca R, Buendía A J, Del Río L, Sánchez J, Salinas J, Navarro J A. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils are necessary for the recruitment of CD8+ T cells in the liver in a pregnant mouse model of Chlamydophila abortus (Chlamydia psittaci serotype 1) infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1746–1751. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1746-1751.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura S, Otani T, Ijiri Y, Motoda R, Kurimoto M, Orita K. IFN-gamma-dependent and -independent mechanisms in adverse effects caused by concomitant administration of IL-18 and IL-12. J Immunol. 2000;164:3330–3336. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orange J S, Wang B, Terhorst C, Biron C A. Requirement for natural killer (NK) cell-produced IFN-γ in defense against murine cytomegalovirus infection and enhancement of this defense pathway by IL-12 administration. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1045–1056. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oxenius A, Karrer U, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. IL-12 is not required for induction of type 1 cytokine responses in viral infections. J Immunol. 1999;162:965–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papp Z, Middleton D M, Rontved C M, Foldvari M, Gordon J R, Baca-Estrada M E. Transtracheal administration of interleukin-12 induces neutrophil responses in the murine lung. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20:191–195. doi: 10.1089/107999000312603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearlman E, Lass J H, Bardenstein D S, Diaconu E, Hazlett Jr F E, Albright J, Higgins A W, Kazura J W. IL-12 exacerbates helmint-mediated corneal pathology by augmenting inflammatory cell recruitment and chemokine expression. J Immunol. 1997;158:827–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry L L, Su H, Feilzer K, Messer R, Hughes S, Witmire W, Caldwell H D. Differential sensitivity of distinct Chlamydia trachomatis isolates to IFN-γ-mediated inhibition. J Immunol. 1999;162:3541–3548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry L L, Feilzer K, Caldwell H D. Immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis is mediated by T helper 1 cells through IFN-gamma dependent and independent pathways. J Immunol. 1997;158:3344–3352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodolakis A, Bernard F, Lantier F. Mouse models for evaluation of virulence of Chlamydia psittaci isolated from ruminants. Res Vet Sci. 1989;46:34–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodolakis A, Salinas J, Papp J. Recent advances on ovine chlamydial abortion. Vet Res. 1998;29:275–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rottenberg M E, Gigliotti-Rothfuchs A, Gigliotti D, Ceausu M, Une C, Levitsky V, Wigzell H. Regulation and role of IFN-γ in the innate resistance to infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Immunol. 2000;164:4812–4818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Satoskar A R, Rodig S, Telford S R, Satoskar A A, Ghosh S K, von Lichtenberg F, David J R. IL-12 gene-deficient C57BL/6 mice are susceptible to Leishmania donovani but have diminished hepatic immunopathology. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:834–839. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200003)30:3<834::AID-IMMU834>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott P. IL-12: initiation cytokine for cell-mediated immunity. Science. 1993;260:496–497. doi: 10.1126/science.8097337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sugawara I, Yamada H, Kaneko H, Mizuno S, Takeda K, Akira S. Role of interleukin-18 (IL-18) in mycobacterial infection in IL-18-gene-disrupted mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2585–2589. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2585-2589.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson-Snipes L, Skamene E, Radzioch D. Acquired resistance but not innate resistance to Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin is compromised by interleukin-12 ablation. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5268–5274. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5268-5274.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trinchieri G. Interleukin 12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xing Z, Zganiacz A, Wang J, Divangahi M, Nawaz F. IL-12 independent Th1-type immune responses to respiratory viral infection: requirement of IL-18 for IFN-γ release in the lung but not for the diferentiation of viral-reactive Th1-type lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164:2575–2584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimoto T, Yoneto T, Waki S, Nariuchi H. IL-12-dependent mechanisms in the clearance of blood-stage murine malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei XAT, an attenuated variant of P. berghei NK65. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1674–1681. doi: 10.1086/515301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoshimoto T, Takahama Y, Wang C R, Yoneto T, Waki S, Nariuchi H. A pathogenic role of IL-12 in blood-stage murine malaria lethal strain Plasmodium berghei NK65 infection. J Immunol. 1998;160:5500–5505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]