Key Points

Question

What are the trends in pediatric mental health emergency department (ED) visits and factors associated with pediatric mental health ED revisits?

Findings

This cohort study included more than 200 000 children seen at 38 US children’s hospitals from 2015 to 2020. Mental health ED visits increased by 8% annually, with 13% of patients revisiting within 6 months; markers of disease severity and health care access were associated with revisits.

Meaning

These findings suggest that pediatric mental health ED visits and revisits are increasing, and identifying patients at high risk of revisit provides an opportunity for tailored interventions to improve mental health care delivery.

This cohort study uses Pediatric Health Information System data to describe trends in mental health pediatric emergency department revisits.

Abstract

Importance

Pediatric emergency department (ED) visits for mental health crises are increasing. Patients who frequently use the ED are of particular concern, as pediatric mental health ED visits are commonly repeat visits. Better understanding of trends and factors associated with mental health ED revisits is needed for optimal resource allocation and targeting of prevention efforts.

Objective

To describe trends in pediatric mental health ED visits and revisits and to determine factors associated with revisits.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cohort study, data were obtained from 38 US children’s hospital EDs in the Pediatric Health Information System between October 1, 2015, and February 29, 2020. The cohort included patients aged 3 to 17 years with a mental health ED visit.

Exposures

Characteristics of patients, encounters, hospitals, and communities.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was a mental health ED revisit within 6 months of the index visit. Trends were assessed using cosinor analysis and factors associated with time to revisit using mixed-effects Cox proportional hazards regression.

Results

There were 308 264 mental health ED visits from 217 865 unique patients, and 13.2% of patients had a mental health revisit within 6 months. Mental health visits increased by 8.0% annually (95% CI, 4.5%-11.4%), whereas all other ED visits increased by 1.5% annually (95% CI, 0.1%-2.9%). Factors associated with mental health ED revisits included psychiatric comorbidities, chemical restraint use, public insurance, higher area measures of child opportunity, and presence of an inpatient psychiatric unit at the presenting hospital. Patients with psychotic disorders (hazard ratio [HR], 1.42; 95% CI, 1.29-1.57), disruptive or impulse control disorders (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.30-1.42), and neurodevelopmental disorders (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.14-1.30) were more likely to revisit. Patients with substance use disorders (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.55-0.66) were less likely to revisit.

Conclusions and Relevance

Markers of disease severity and health care access were associated with mental health revisits. Directing hospital and community interventions toward identified high-risk patients is needed to help mitigate recurrent mental health ED use and improve mental health care delivery.

Introduction

Families of children with mental health needs increasingly rely on the emergency department (ED) for care. From 2007 to 2016, pediatric mental health ED visits in the US increased by more than 60% at all hospital EDs and by more than 120% at children’s hospitals. The ongoing surge in pediatric mental health ED visits may be associated with a combination of factors, including a worsening crisis of pediatric mental illness and shortage of mental health clinicians.

Mental health ED visits and hospitalizations have longer lengths of stay and incur higher costs than non–mental health visits. As mental health visits have surged, ED lengths of stay have increased, worsening preexisting overcrowding at children’s hospital EDs. Pediatric mental health ED visits are commonly repeat visits, and most revisits occur within 6 months of initial presentation. However, previous research on pediatric mental health ED revisits has been limited to state-based or single-center studies, which may be subject to local or regional forces.

A better understanding of trends and factors associated with mental health ED revisits would allow for improved resource allocation and interventions tailored to high-risk patients, including implementation of focused prevention efforts and mental health–specific service delivery. Therefore, our objectives were to describe (1) trends in pediatric mental health ED visits and revisits and (2) factors associated with mental health ED revisits overall and among the subgroup of patients discharged from the ED.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of mental health ED visits to US children’s hospitals between October 1, 2015, and February 29, 2020. Data were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), an administrative database that contains billing, demographic, and resource utilization data from 49 tertiary care US children’s hospitals. We included data from 38 hospitals that had complete discharge and billing data and all variables of interest available. Estimates of county-level pediatric psychiatrist and psychologist counts were obtained from the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System, and corresponding county-level pediatric population counts were obtained from the 2015-2019 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. The Children’s Hospital Los Angeles institutional review board determined our study exempt from review due to use of a coded database that does not contain identifiable protected health information. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study Population

We evaluated pediatric mental health ED visits between October 1, 2015, and February 29, 2020. We defined mental health ED visits as those with either (1) a principal diagnosis within a subset of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Disorders Classification System (CAMHD-CS) groups or (2) a principal or secondary diagnosis of intentional self-harm, using previously defined International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes. We combined the 1769 included diagnoses into 11 clinically meaningful mental health diagnosis groups based on CAMHD-CS groups and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) categories (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). The CAMHD-CS diagnosis groups with a small number of encounters in our study population were combined into an “other disorders” group. The 11 groups were anxiety disorders, eating disorders, disruptive or impulse control disorders, mood disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders (eg, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism), psychotic disorders, somatic symptom disorders, substance use disorders, suicidal ideation or self-harm, trauma disorders (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder), and other disorders (eg, CAMHD-CS dissociative disorders, mental health symptoms, miscellaneous disorders, and personality disorders). We excluded visits for patients who died at the index visit or who did not have complete data on all variables of interest.

Outcome Measures and Variable Definitions

We defined the index visit as the first mental health ED visit during the study period for each patient. Our primary outcome was a mental health ED revisit, defined as the earliest mental health ED visit within 6 months (180 days) of the index ED visit. We chose 6 months as the cutoff because mental health revisits within 6 months are more likely to be clinically associated with treatment at the index visit, and this cutoff is commonly used in the literature. We evaluated only the first revisit for each patient and did not include multiple revisits.

We used the Andersen model of health care utilization, which provides a means for understanding access to care and resource utilization, as a conceptual framework for variable selection in our statistical modeling. We studied patient, encounter, hospital, and community variables to account for predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors as described in the Andersen model. We incorporated factors associated with predisposition to using medical care (predisposing), including both demographic factors (age and sex) and social constructs (race and ethnicity as delineated by the PHIS). We included factors associated with access to care (enabling), including urbanicity of the patient’s home address based on Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes, distance to the hospital (from the centroid of the home zip code to the centroid of the presenting hospital’s zip code), insurance type, and mental health clinician densities in the county of each hospital (calculated by dividing the number of active child psychiatrists and child psychologists in the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System by the pediatric population). We also included patient zip code–level Child Opportunity Index (COI), a composite measure of neighborhood resources based on 29 indicators related to educational, health and environmental, and socioeconomic conditions. We included factors associated with higher severity or complexity of illness (need), including mental health diagnosis group, presence of a complex chronic condition, psychiatric comorbidities (defined as diagnoses from ≥2 DSM-5 categories), chemical restraint use, weekend or weekday presentation, time of presentation, disposition, and intensive care unit admission.

We included presence of an inpatient psychiatric unit as a factor because hospitals with inpatient psychiatric units may have different resources and referral patterns that influence the types of patients seen. We defined hospitals with an inpatient psychiatric unit as those that submitted psychiatric unit bed charges for each month of the study and hospitals without a psychiatric unit as those that never submitted psychiatric unit charges. For hospitals where the monthly psychiatric charges were inconsistent, we confirmed the presence or absence of a psychiatric unit through manual review (eMethods in Supplement 1). Hospitals that opened or closed an inpatient psychiatric unit during the study period or for which we were unable to determine psychiatric unit status were excluded.

Data Analysis

Trends in Pediatric Mental Health ED Visits and Revisits

In consideration of seasonal variation in mental health visits, we graphed cumulative change in mental health ED visits from October 2015 alongside relative month-specific change in mental health ED visits by comparing the number of visits each month with the same month in the baseline year (October 2015 to September 2016). We then conducted cosinor analysis to model relative time trends in mental health and non–mental health ED visits and revisits while accounting for seasonality of data. We graphically assessed the data to confirm they met the key assumption of sinusoidal seasonality for the cosinor model. For analysis of time trends in overall mental health ED revisits, we included all mental health revisits (rather than limiting to the index encounter for each patient) and analyzed only visits before September 2019 to allow 6 months for revisit before the study end. We separately analyzed time trends for each diagnosis group.

Factors Associated With Mental Health ED Revisits

We first performed a univariable analysis between each factor and mental health ED revisit within 6 months. For our primary analysis, we used Cox proportional hazards regression modeling to assess time to mental health revisit within 6 months. We used number of days from the index visit as the time scale and right-censored at 6 months (180 days) from the index visit and at the end of the study period. We graphically assessed for violations in the proportional hazards assumption using survival curves and Schoenfeld residuals for each variable, and we determined that model assumptions were satisfied. To account for the research design effect of patients nested within hospitals, we included hospital as a random effect in our Cox proportional hazards regression modeling.

We performed multiple stratified subanalyses using separate Cox proportional hazards regression models. First, we assessed factors associated with revisit for only patients discharged from the ED. Second, we assessed factors associated with revisit for each of the 4 most common diagnosis groups (suicidal ideation or self-harm, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and disruptive or impulse control disorders). Third, we assessed factors associated with revisit for each of the 3 included age groups (3-7, 8-12, and 13-17 years) to capture differences across the range of ages studied.

Sensitivity Analysis

Only 61.9% of mental health ED revisits in our study cohort occurred within 6 months. We therefore performed a sensitivity analysis repeating the main model to assess time to mental health revisits without censoring at 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

For all models and significance testing, we used a 2-sided α of .05 and reported 95% CIs. Statistical analysis was performed using the data.table, ggplot2, season, survival, and coxme packages in R, version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Study Sample

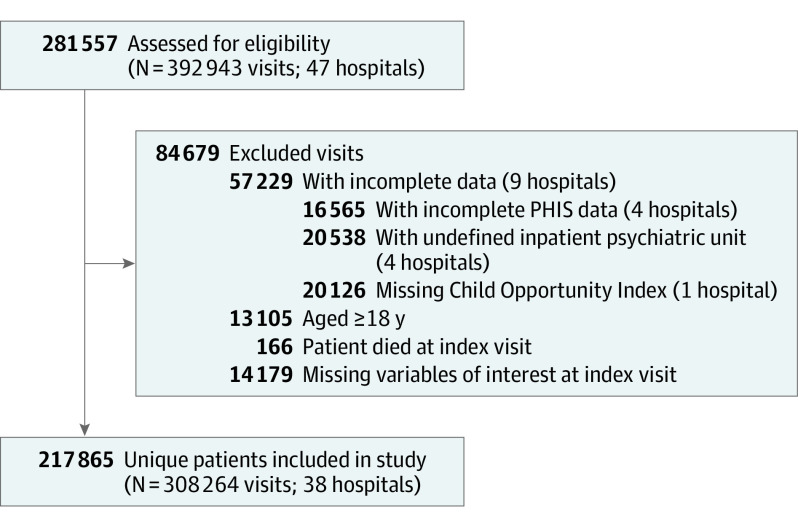

There were 308 264 mental health ED visits from 217 865 unique patients at the 38 included hospitals (Figure 1). Mental health ED visits made up 4.0% of all ED visits. The majority of patients with mental health ED visits were girls (56.0% vs 44.0% boys; mean [SD] age, 13.0 [3.2] years), non-Hispanic White (50.4% vs 1.6% Asian American, 17.3% Hispanic, and 22.3% non-Hispanic Black), had public insurance (50.3%), and lived in an urban area (84.4%) (Table 1). The most common diagnosis groups were suicidal ideation or self-harm (28.7%), mood disorders (23.5%), anxiety disorders (10.4%), and disruptive or impulse control disorders (9.7%). Overall, 28 716 (13.2%) patients had a mental health ED revisit within 6 months.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Included Patients.

Visits from patients older than 18 years were included in the data set initially to capture revisits that occurred after a patient’s 18th birthday for those patients who were younger than 18 at the index visit and had a mental health emergency department revisit after turning 18. Those visits in which they were aged 18 years or older were then excluded from further visit counts and trend analyses. PHIS indicates Pediatric Health Information System.

Table 1. Patient Demographics and Factors Associated With Mental Health Emergency Department Revisits Within 6 Months of the Index Visit.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (N = 217 865) | Patients with revisits (n = 28 716 [13.2%]) | |||

| Predisposing factors | ||||

| Age group, y | ||||

| 3-7 | 16 041 (7.4) | 1940 (6.8) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 8-12 | 64 601 (29.7) | 9655 (33.6) | 1.27 (1.21-1.33) | |

| 13-17 | 137 223 (63.0) | 17 121 (59.6) | 1.04 (0.99-1.09) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 121 922 (56.0) | 15 980 (55.6) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Male | 95 943 (44.0) | 12 736 (44.4) | 0.93 (0.91-0.96) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Asian American | 3533 (1.6) | 432 (1.5) | 0.89 (0.81-0.98) | |

| Hispanic | 37 705 (17.3) | 4322 (15.1) | 0.88 (0.85-0.92) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 48 595 (22.3) | 6960 (24.2) | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 109 862 (50.4) | 14 562 (50.7) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Othera | 18 170 (8.3) | 2440 (8.5) | 0.93 (0.89-0.98) | |

| Enabling factors | ||||

| Insurance type | ||||

| Public | 109 537 (50.3) | 16 024 (55.8) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Private | 92 741 (42.6) | 11 247 (39.2) | 0.81 (0.78-0.83) | |

| Other | 15 587 (7.2) | 1445 (5.0) | 0.79 (0.74-0.83) | |

| Child Opportunity Index | ||||

| Very low | 52 798 (24.2) | 7196 (25.1) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Low | 37 637 (17.3) | 4473 (15.6) | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | |

| Moderate | 39 621 (18.2) | 5181 (18.0) | 1.06 (1.02-1.11) | |

| High | 38 512 (17.7) | 4968 (17.3) | 1.06 (1.02-1.11) | |

| Very high | 49 297 (22.6) | 6898 (24.0) | 1.08 (1.03-1.12) | |

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Urban | 183 872 (84.4) | 25 165 (87.6) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Suburban | 18 352 (8.4) | 2136 (7.4) | 1.03 (0.98-1.08) | |

| Rural | 15 641 (7.2) | 1415 (4.9) | 0.85 (0.79-0.90) | |

| Distance quartile | ||||

| First (closest) | 55 323 (25.4) | 8556 (29.8) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Second | 54 309 (24.9) | 7722 (26.9) | 0.91 (0.88-0.94) | |

| Third | 53 798 (24.7) | 6932 (24.1) | 0.78 (0.75-0.81) | |

| Fourth (farthest) | 54 435 (25.0) | 5506 (19.2) | 0.63 (0.60-0.66) | |

| Child psychiatrists per 10 000 children, median (IQR) | 1.51 (0.93-2.41) | 1.59 (1.26-2.93) | 1.00 (0.89-1.13) | |

| Child psychologists per 10 000 children, median (IQR) | 1.58 (1.23-2.93) | 1.76 (1.11-3.15) | 1.09 (0.97-1.22) | |

| Need factors | ||||

| Mental health diagnosis group | ||||

| Suicidal ideation or self-harm | 62 432 (28.7) | 6918 (24.1) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Disorders | ||||

| Mood | 51 170 (23.5) | 8100 (28.2) | 1.16 (1.12-1.20) | |

| Anxiety | 22 585 (10.4) | 2242 (7.8) | 0.95 (0.90-1.00) | |

| Disruptive or impulse control | 21 167 (9.7) | 3640 (12.7) | 1.36 (1.30-1.42) | |

| Trauma | 11 604 (5.3) | 1618 (5.6) | 1.03 (0.98-1.09) | |

| Neurodevelopmental | 8416 (3.9) | 1299 (4.5) | 1.22 (1.14-1.30) | |

| Substance use | 7750 (3.6) | 459 (1.6) | 0.60 (0.55-0.66) | |

| Somatic symptom | 3686 (1.7) | 393 (1.4) | 1.04 (0.94-1.15) | |

| Eating | 3308 (1.5) | 424 (1.5) | 1.18 (1.06-1.30) | |

| Psychotic | 2283 (1.0) | 435 (1.5) | 1.42 (1.29-1.57) | |

| Other | 23 464 (10.8) | 3188 (11.1) | 1.25 (1.19-1.31) | |

| Multiple psychiatric comorbidities | ||||

| No | 143 635 (65.9) | 16 025 (55.8) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 74 230 (34.1) | 12 691 (44.2) | 1.34 (1.30-1.38) | |

| Complex chronic condition | ||||

| No | 206 071 (94.6) | 27 220 (94.8) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 11 794 (5.4) | 1496 (5.2) | 0.96 (0.91-1.02) | |

| Disposition | ||||

| Discharged | 126 725 (58.2) | 14 566 (50.7) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Admitted | 61 584 (28.3) | 10 005 (34.8) | 1.29 (1.25-1.34) | |

| Transferred | 29 556 (13.6) | 4145 (14.4) | 1.40 (1.34-1.45) | |

| Intensive care unit stay | ||||

| No | 215 210 (98.8) | 28 508 (99.3) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 2655 (1.2) | 208 (0.7) | 0.61 (0.53-0.70) | |

| Chemical restraint use | ||||

| No | 210 088 (96.4) | 27 590 (96.1) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 7777 (3.6) | 1126 (3.9) | 1.22 (1.15-1.30) | |

| Day of presentation | ||||

| Weekday | 179 974 (82.6) | 23 891 (83.2) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Weekend | 37 891 (17.4) | 4825 (16.8) | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | |

| Hour of presentation | ||||

| 8 am-4 pm | 88 021 (40.4) | 11 412 (39.7) | 1 [Reference] | |

| 4 pm-12 am | 104 579 (48.0) | 14 266 (49.7) | 1.05 (1.02-1.08) | |

| 12 am-8 am | 25 265 (11.6) | 3038 (10.6) | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | |

| Inpatient psychiatric unit | ||||

| No | 75 767 (34.8) | 7869 (27.4) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Yes | 142 098 (65.2) | 20 847 (72.6) | 1.59 (1.29-1.96) | |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Other included non-Hispanic patients who were American Indian, Pacific Islander, multiple, or other races.

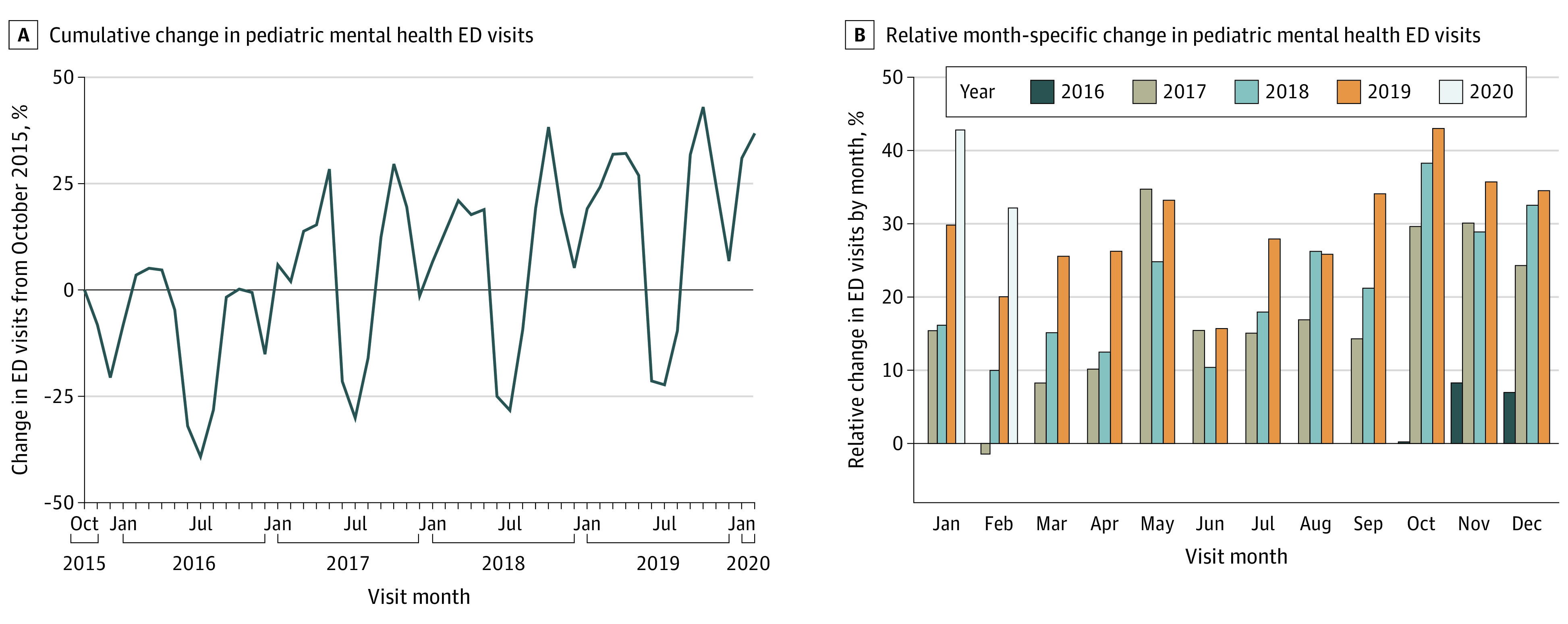

Trends in Pediatric Mental Health ED Visits and Revisits

Mental health ED visits increased from the study start in October 2015, with visits showing large seasonal variation (Figure 2A). By the end of the study period, monthly mental health ED visits increased in each month by up to 43% from the baseline year (Figure 2B). Cosinor analysis revealed that mental health ED visits increased by 8.0% annually (95% CI, 4.5%-11.4%), whereas all other visits increased by 1.5% annually (95% CI, 0.1%-2.9%). Meanwhile, mental health ED revisits increased by 6.3% annually (95% CI, 2.7%-9.9%), but the percentage of mental health ED visits with a revisit remained stable. Patients presenting with somatic disorders (26.3% annually; 95% CI, 20.4%-32.2%), trauma disorders (18.3% annually; 95% CI, 13.2%-23.5%), suicidal ideation or self-harm (15.3% annually, 95% CI, 10.9.1%-19.7%), and eating disorders (15.0% annually; 95% CI, 12.1%-17.8%) had the largest increases in ED visits. No illness category saw a decrease over the study period.

Figure 2. Change in Pediatric Mental Health Emergency Department (ED) Visits.

Factors Associated With Mental Health ED Revisits

We found a significant univariable association between mental health revisit and each covariate except sex and complex chronic condition (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed multiple factors associated with time to ED revisit within 6 months (Table 1).

Factors were grouped into predisposing, enabling, and need according to the Andersen model of health care utilization. Predisposing social constructs associated with revisits included race and ethnicity, with non-Hispanic White patients more likely to revisit (reference) and Asian American patients (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81-0.98), Hispanic patients (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.85-0.92), and patients of other race (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.89-0.98) less likely to revisit. Enabling factors associated with shorter time to revisit included having public insurance compared with private (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.78-0.83) or other (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.74-0.83) insurance and very high COI compared with very low COI (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03-1.12). Need factors associated with revisit included psychiatric comorbidities (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.30-1.38), chemical restraint use (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.15-1.30), and diagnosis group. Compared with patients with suicidal ideation or self-harm, patients with psychotic disorders (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.29-1.57), disruptive or impulse control disorders (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.30-1.42), neurodevelopmental disorders (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.14-1.30), eating disorders (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.30), and mood disorders (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20) were more likely to revisit. Patients with substance use disorders (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.55-0.66) were less likely to revisit. Patients presenting to a hospital with an inpatient psychiatric unit were also more likely to revisit (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.29-1.96).

Subanalyses

In the subanalysis of patients discharged from the ED, most factors remained stable (Table 2). By diagnosis group, race and ethnicity and COI were no longer significantly associated with revisit for patients presenting with disruptive or impulse control disorders (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). By age group, presenting with a disruptive or impulse control disorder was associated with revisits in all age groups (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Furthermore, patients aged 8 to 12 years were more likely to revisit if they had a psychotic disorder (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.01-1.52), whereas patients aged 13 to 17 years were more likely to revisit if they had a neurodevelopmental disorder (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.32-1.63), somatic symptom disorder (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.15-1.46), eating disorder (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.16-1.47), or psychotic disorder (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.38-1.73). In the sensitivity analysis of mental health ED revisits without limitation on time, most factors had similar HRs (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Factors Associated With Mental Health Emergency Department Revisits Within 6 Months for Patients Discharged From the Index Emergency Department Visit.

| Characteristic | Patients with revisits (n = 14 566 [11.5%]), No. (%) | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | ||

| Age group, y | ||

| 3-7 | 1281 (8.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| 8-12 | 5277 (36.2) | 1.23 (1.16-1.31) |

| 13-17 | 8008 (55.0) | 1.13 (1.06-1.20) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 7516 (51.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 7050 (48.4) | 0.94 (0.91-0.98) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Asian American | 234 (1.6) | 0.93 (0.81-1.06) |

| Hispanic | 2302 (15.8) | 0.83 (0.78-0.87) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3548 (24.4) | 0.97 (0.93-1.02) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 7298 (50.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| Othera | 1184 (8.1) | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) |

| Enabling factors | ||

| Insurance type | ||

| Public | 8056 (55.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Private | 5733 (39.4) | 0.83 (0.79-0.86) |

| Other | 777 (5.3) | 0.73 (0.68-0.79) |

| Child Opportunity Index | ||

| Very low | 3752 (25.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Low | 2224 (15.3) | 1.03 (0.98-1.09) |

| Moderate | 2522 (17.3) | 1.06 (1.00-1.12) |

| High | 2481 (17.0) | 1.07 (1.01-1.14) |

| Very high | 3587 (24.6) | 1.09 (1.03-1.16) |

| Urbanicity | ||

| Urban | 12 974 (89.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| Suburban | 1028 (7.1) | 1.01 (0.94-1.09) |

| Rural | 564 (3.9) | 0.85 (0.77-0.94) |

| Distance quartile | ||

| First (closest) | 4738 (32.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Second | 3948 (27.1) | 0.89 (0.85-0.93) |

| Third | 3472 (23.8) | 0.76 (0.73-0.80) |

| Fourth (farthest) | 2408 (16.5) | 0.64 (0.60-0.68) |

| Child psychiatrists per 10 000 children, median (IQR) | 1.59 (1.25-2.93) | 0.98 (0.87-1.10) |

| Child psychologists per 10 000 children, median (IQR) | 1.76 (1.09-3.15) | 1.10 (0.98-1.24) |

| Need factors | ||

| Mental health diagnosis group | ||

| Suicidal ideation or self-harm | 2885 (19.8) | 1 [Reference] |

| Disorders | ||

| Mood | 3178 (21.8) | 1.03 (0.98-1.09) |

| Anxiety | 1799 (12.4) | 0.84 (0.79-0.89) |

| Disruptive or impulse control | 2161 (14.8) | 1.23 (1.15-1.30) |

| Trauma | 959 (6.6) | 0.87 (0.81-0.94) |

| Neurodevelopmental | 814 (5.6) | 1.06 (0.98-1.16) |

| Substance use | 336 (2.3) | 0.50 (0.45-0.56) |

| Somatic symptom | 170 (1.2) | 1.09 (0.93-1.27) |

| Eating | 111 (0.8) | 1.29 (1.07-1.56) |

| Psychotic | 99 (0.7) | 1.81 (1.48-2.22) |

| Other | 2054 (14.1) | 1.10 (1.04-1.17) |

| Multiple psychiatric comorbidities | ||

| No | 10 391 (71.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 4175 (28.7) | 1.41 (1.35-1.46) |

| Complex chronic condition | ||

| No | 14 273 (98.0) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 293 (2.0) | 0.95 (0.85-1.07) |

| Chemical restraint use | ||

| No | 14 336 (98.4) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 230 (1.6) | 1.70 (1.49-1.94) |

| Day of presentation | ||

| Weekday | 12 248 (84.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| Weekend | 2318 (15.9) | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) |

| Hour of presentation | ||

| 8 am-4 pm | 6546 (44.9) | 1 [Reference] |

| 4 pm-12 am | 7052 (48.4) | 1.07 (1.03-1.10) |

| 12 am-8 am | 968 (6.6) | 1.00 (0.93-1.07) |

| Inpatient psychiatric unit | ||

| No | 3825 (26.3) | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 10741 (73.7) | 1.57 (1.27-1.94) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Other included non-Hispanic patients who were American Indian, Pacific Islander, multiple, or other races.

Discussion

In this cohort study of mental health visits at US children’s hospital EDs from 2015 to 2020, we found that mental health ED visits increased by 8% annually, whereas all other visits increased by 1.5% annually. Mental health ED revisits increased by more than 6% annually, but the proportion of mental health ED visits with a revisit remained stable. Factors associated with mental health ED revisits were multifactorial, and we found important differences in revisits across diagnosis groups and by markers of health care access. There were few differences in factors in subanalyses by discharge status, mental health diagnosis, and age group.

The trends we observed in pediatric mental health ED visits and revisits show that the problem of increasing pediatric mental health ED visits has not abated. We found that the proportion of mental health ED visits with a revisit remained stable, which may reflect that the factors associated with revisit did not change substantially during the study period, even as the pediatric mental health crisis worsened. In addition, previous literature has indicated that many children who present to the ED for mental health reasons have low acuity, so it is possible that children with low acuity, who are less likely to revisit, contributed to the stability we observed in revisit percentage. However, the significant increase in the raw number of revisits is still concerning, as increased visits overwhelm existing care models and result in worse outcomes for ED patients with and without mental health emergencies.

We identified significant differences in revisits across diagnosis groups. Consistent with previous literature, we found that patients with diagnoses associated with behavior disturbance, including disruptive or impulse control disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, and psychotic disorders, were at highest risk of revisit. The agitation and aggressive behavior seen in these illnesses may contribute to revisits. Although patients with mood disorders had a high risk of revisit, those with suicidal ideation or self-harm were not among those most likely to revisit. The mixed findings of whether patients with intentional self-harm are likely to revisit may reflect challenges in differentiating suicide attempt from nonsuicidal self-injurious behavior on the basis of diagnostic codes alone, as well as the heterogeneity in this patient population. It is also possible that given the gravity of intentional self-harm, such patients receive more intensive care after ED or inpatient discharge, which may lead to fewer revisits or prolonged inpatient hospital stays.

We observed important findings related to access to health care, with both public insurance and higher COI being associated with shorter time to mental health ED revisit. The inverse association between COI and revisit is in contrast to previous studies that found lower COI to be associated with hospital and emergency medical service use for other conditions. There are a number of reasons that could explain these findings, including differences in mental health referral patterns for patients from high vs low COI neighborhoods. Children with mental health clinicians are more likely to revisit the ED, possibly because of greater severity of illness, increased referral for crisis evaluation by their clinician, or greater mental health literacy among parents of when to seek emergency care. Thus, patients from low COI neighborhoods may be less likely to have a mental health clinician and less likely to be referred to the ED. The association between illness severity and COI as it relates to revisiting the ED is not yet known. Further exploration of these differences and the role of personal factors and neighborhood context in ED use and geographic access to mental health services is needed.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we could not account for revisits or readmissions outside of PHIS hospitals. Second, we were unable to capture detailed clinical information, such as previous psychiatric hospitalization, preferred language, or mental health resources available at the presenting hospital, which may be associated with revisits. However, we attempted to capture markers of disease severity through our inclusion of variables pertaining to multiple diagnoses and medications and mental health resources through our inclusion of inpatient psychiatric unit status. Third, available International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes cannot distinguish intentional self-harm with and without suicide attempt, making it difficult to distinguish subtleties in the risk of revisit between these populations. Fourth, we were only able to quantify the number of licensed pediatric psychiatrists and psychologists, which may underestimate the true number of mental health professionals at large. Fifth, we evaluated the trend in ED visits and revisits nationally but did not take into account hospital-level variation in our trend analysis; as such, hospital-specific trends may differ from our national estimate. Fifth, because we determined the time to revisit based on initial presentation, we did not take into account the length of stay for patients who were admitted to a hospital, during which time they would not be able to revisit. However, average length of stay for pediatric mental health admissions is 7 days, a small fraction of the 6-month time to revisit that we used as our primary outcome. Furthermore, we found that the majority of associated factors remained stable in our subanalysis of discharged patients and, thus, do not believe that our findings are attenuated.

Conclusions

Pediatric mental health ED visits and revisits are increasing rapidly. Factors associated with mental health revisits in this cohort study include presenting mental health diagnosis and markers of severe disease and health care access. Improved intervention services for patients with a behavioral health crisis are needed on a hospital and systems level to reduce pediatric mental health ED use and ensure access to appropriate follow-up care, with a particular focus on those patients most likely to revisit.

eMethods

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision Codes for Mental Health Diagnoses

eTable 2. Univariable Factors Associated With Mental Health Emergency Department Revisits Within 6 Months

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Emergency Department Revisits Within 6 Months by Diagnosis Group

eTable 4. Factors Associated With Emergency Department Revisits Within 6 Months by Age Group

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis of Factors Associated With Time to Ever Having a Mental Health Emergency Department Visit

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Lo CB, Bridge JA, Shi J, Ludwig L, Stanley RM. Children’s mental health emergency department visits: 2007-2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20191536. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas CR, Holzer CE III. The continuing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(9):1023-1031. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000225353.16831.5d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, Duffy ME, Binau SG. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(3):185-199. doi: 10.1037/abn0000410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahajan P, Alpern ER, Grupp-Phelan J, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) . Epidemiology of psychiatric-related visits to emergency departments in a multicenter collaborative research pediatric network. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(11):715-720. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181bec82f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torio CM, Encinosa W, Berdahl T, McCormick MC, Simpson LA. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: national estimates of cost, utilization and expenditures for children with mental health conditions. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):19-35. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grupp-Phelan J, Mahajan P, Foltin GL, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network . Referral and resource use patterns for psychiatric-related visits to pediatric emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(4):217-220. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31819e3523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nash KA, Zima BT, Rothenberg C, et al. Prolonged emergency department length of stay for US pediatric mental health visits (2005-2015). Pediatrics. 2021;147(5):e2020030692. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-030692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frosch E, dosReis S, Maloney K. Connections to outpatient mental health care of youths with repeat emergency department visits for psychiatric crises. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(6):646-649. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_0646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cloutier P, Thibedeau N, Barrowman N, et al. Predictors of repeated visits to a pediatric emergency department crisis intervention program. CJEM. 2017;19(2):122-130. doi: 10.1017/cem.2016.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leon SL, Cloutier P, Polihronis C, et al. Child and adolescent mental health repeat visits to the emergency department: a systematic review. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(3):177-186. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Children’s Hospital Association . Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). Accessed December 2, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/phis

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . The National Plan and Provider Enumeration System downloadable file (data set and code book). Accessed June 14, 2021. https://download.cms.gov/nppes/NPI_Files.html

- 13.University of Michigan Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center . The child and adolescent psychologist workforce, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.behavioralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Y5P3_The-Child-and-Adolescent-BH-Workforce_Full-Report.pdf

- 14.US Census Bureau . 2015-2019 ACS 5-Year Estimates. US Census Burear; 2019. Accessed September 1, 2021. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2019/5-year.html

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zima BT, Gay JC, Rodean J, et al. Classification system for International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification and Tenth Revision pediatric mental health disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(6):620-622. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, Crosby A, Holland K, Proescholdbell S. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;(108):1-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marr M, Horwitz SM, Gerson R, Storfer-Isser A, Havens JF. Friendly faces: characteristics of children and adolescents with repeat visits to a specialized child psychiatric emergency program. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(1):4-10. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leon SL, Polihronis C, Cloutier P, et al. Family factors and repeat pediatric emergency department visits for mental health: a retrospective cohort study. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(1):9-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson R, Davidson P, Baumeister S. Improving access to care. In: Kominski GF, ed. Changing the U.S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; 2013:33-70. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hailu A, Wasserman C. Guidelines for Using Rural-Urban Classification Systems for Community Health Assessment. Washington State Dept of Health; 2016. Accessed August 31, 2021. https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/Documents/1500//RUCAGuide.pdf

- 23.Sills MR, Hall M, Colvin JD, et al. Association of social determinants with children’s hospitals’ preventable readmissions performance. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):350-358. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acevedo-Garcia D, McArdle N, Hardy EF, et al. The Child Opportunity Index: improving collaboration between community development and public health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(11):1948-1957. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric Complex Chronic Conditions Classification System version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster AA, Porter JJ, Monuteaux MC, Hoffmann JA, Hudgins JD. Pharmacologic restraint use during mental health visits in pediatric emergency departments. J Pediatr. 2021;236:276-283.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cutler GJ, Rodean J, Zima BT, et al. Trends in pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions and disposition by presence of a psychiatric unit. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(8):948-955. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.05.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasken C, Wagers B, Sondhi J, Miller J, Kanis J. The impact of a new on-site inpatient psychiatric unit in an urban pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38(1):e12-e16. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnett AG, Dobson AJ. Analysing Seasonal Health Data. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2010. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10748-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tibshirani R. What is Cox’s proportional hazards model? Significance. 2022;19(2):38-39. doi: 10.1111/1740-9713.01633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess KR. Graphical methods for assessing violations of the proportional hazards assumption in Cox regression. Stat Med. 1995;14(15):1707-1723. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoge MA, Vanderploeg J, Paris M Jr, Lang JM, Olezeski C. Emergency department use by children and youth with mental health conditions: a health equity agenda. Community Ment Health J. 2022;58(7):1225-1239. doi: 10.1007/s10597-022-00937-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cloutier P, Kennedy A, Maysenhoelder H, Glennie EJ, Cappelli M, Gray C. Pediatric mental health concerns in the emergency department: caregiver and youth perceptions and expectations. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(2):99-106. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181cdcae1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doan Q, Wong H, Meckler G, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) . The impact of pediatric emergency department crowding on patient and health care system outcomes: a multicentre cohort study. CMAJ. 2019;191(23):E627-E635. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.181426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conrad HB, Hollenbach KA, Gehlbach DL, Ferran KL, Barham TA, Carstairs KL. The impact of behavioral health patients on a pediatric emergency department’s length of stay and left without being seen. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(8):584-587. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newton AS, Ali S, Johnson DW, et al. Who comes back? characteristics and predictors of return to emergency department services for pediatric mental health care. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):177-186. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00633.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldstein AB, Frosch E, Davarya S, Leaf PJ. Factors associated with a six-month return to emergency services among child and adolescent psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(11):1489-1492. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.11.1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kersten EE, Adler NE, Gottlieb L, et al. Neighborhood child opportunity and individual-level pediatric acute care use and diagnoses. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20172309. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramgopal S, Jaeger L, Cercone A, Martin-Gill C, Fishe J. The Child Opportunity Index and pediatric emergency medical services utilization. Prehosp Emerg Care. Published online May 31, 2022. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2022.2076268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krager MK, Puls HT, Bettenhausen JL, et al. The Child Opportunity Index 2.0 and hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2):e2020032755. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-032755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beck AF, Huang B, Wheeler K, Lawson NR, Kahn RS, Riley CL. The Child Opportunity Index and disparities in pediatric asthma hospitalizations across one Ohio metropolitan area, 2011-2013. J Pediatr. 2017;190:200-206.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macy ML, Zonfrillo MR, Cook LJ, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network . Patient- and community-level sociodemographic characteristics associated with emergency department visits for childhood injury. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):711-718.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cummings JR. Contextual socioeconomic status and mental health counseling use among US adolescents with depression. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(7):1151-1162. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0021-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision Codes for Mental Health Diagnoses

eTable 2. Univariable Factors Associated With Mental Health Emergency Department Revisits Within 6 Months

eTable 3. Factors Associated With Emergency Department Revisits Within 6 Months by Diagnosis Group

eTable 4. Factors Associated With Emergency Department Revisits Within 6 Months by Age Group

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis of Factors Associated With Time to Ever Having a Mental Health Emergency Department Visit

Data Sharing Statement