Key Points

Question

Are racial disparities in high school students’ sense of school belonging associated with cardiometabolic health in adulthood?

Findings

In this cohort study of a national sample of 4830 US children, adolescents, and young adults, attending a school that had a greater Black-White gap in school belonging was associated with an increased risk of diabetes and more risk factors for metabolic syndrome 13 years later among Black students.

Meaning

Fostering a more equitable and inclusive sense of school belonging across racial groups may have implications for cardiovascular health disparities in students.

Abstract

Importance

School belonging has important implications for academic, psychological, and health outcomes, but the associations between racial disparities in school belonging and health have not been explored to date.

Objective

To examine associations between school-level racial disparities in belonging and cardiometabolic health into adulthood in a national sample of Black and White children, adolescents, and young adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective cohort study of a US national sample of 4830 Black and White students (National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health) followed up for 13 years. The study was conducted from 1994 to 1995 for wave 1 and in 2008 for wave 4. Data were analyzed from June 14 to August 13, 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

School-level racial disparities in belonging at baseline were calculated as the mean level of school belonging for Black students minus the mean level of school belonging for White students at the school that they attended when they were aged 12 to 20 years. Diabetes and metabolic syndrome were measured as outcomes for these same participants at 24 to 32 years of age.

Results

The study included 4830 students. For wave 1, mean (SD) age was 16.1 (1.7) years, and for wave 4, 29.0 (1.7) years. A total of 2614 (54.1%) were female, 2219 were non-Hispanic Black (45.9%), and 2611 were non-Hispanic White (54.1%). Among Black students, attending a school with a greater Black-White disparity in school belonging (more negative scores) was associated with an increased risk for diabetes (odds ratio, 0.66 [95% CI, 0.46-0.95]) and more risk factors for metabolic syndrome (rate ratio, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.90-1.00]) in adulthood 13 years later. These associations persisted above individual-level controls (age, sex, and body mass index) and school-level controls (school size, percentage of Black students, and percentage of Black teachers) and were not explained by either an individual’s own perception of school belonging or the mean level of belonging across the whole school.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this prospective cohort study of US students, racial disparities in school belonging were associated with risks for diabetes and metabolic syndrome in Black students. Among students, fostering a more equal sense of school belonging across racial groups may have implications for health disparities in the cardiometabolic domain into adulthood.

This cohort study investigates racial disparities in school belonging and prospective associations with cardiometabolic health in adulthood.

Introduction

After more than a year of remote school for many students because of the COVID-19 pandemic, seeking ways to help them reengage with in-person school has become a pressing societal concern in the United States. One important factor in this regard is students’ sense of school belonging, defined as perceptions of feeling accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school environment. A large body of literature has documented reliable associations between school belonging and better academic outcomes (eg, better grades and lower dropout rates), psychological well-being (eg, higher self-esteem, fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms, and lower rates of suicide attempts), and behavioral outcomes (eg, lower rates of substance use, fewer conduct problems, and fewer violent behaviors).

School belonging can be assessed at the individual or school level. At the school level, aggregated belonging levels across students in a school reflect the school’s overall social climate. Social climate includes the quality of student-teacher and student-student relationships, the teaching and learning environment, and the values and expectations a school upholds. Within a school, however, perceptions of belonging can often vary by racial groups. In general, students from racial and ethnic minority groups are less likely to feel included, accepted, and respected at school; report less positive relationships with adults at school; and are less likely to see their groups represented in authority positions compared with White students. The degree to which White students and students from racial and ethnic minority groups differ in their perceptions of belonging at the same school thus suggests the different social experiences of these groups at school and may provide an indication of that school’s racial climate.

A larger gap, or racial disparities, in school belonging between White students and students of racial and ethnic minority groups have implications for academic, behavioral, and even possibly health outcomes. For example, a sense of belonging among Black students relative to White students at a school was associated with a less significant gap in suspension rates between Black and White students. Similarly, schools with smaller Black-White gaps in school belonging also had smaller Black-White gaps in academic achievement.

In the present study, we sought to understand the implications of an institutional climate—here defined as the racial gap in belonging between Black and White students at the same school—for the cardiometabolic health of these students into young adulthood. This research question represents a test of the theory that living in a system that conveys an unequal status, value, or opportunities for certain groups will be associated with adverse health outcomes for members of those groups. These theories propose that the health inequalities found in our society are a consequence of certain groups experiencing the cumulative impact of a lifetime of social, economic, and political exclusion and marginalization and that these experiences “weather” physiologic systems, resulting in earlier health deterioration for marginalized groups. Although, to our knowledge, no study has directly addressed the question of associations between racial gaps in school belonging and physical health outcomes, related studies on other aspects of school racial climates suggest such associations might exist. For example, when students from racial and ethnic minority groups attend schools that explicitly emphasize the value of racial diversity in their mission statements, they have lower levels of metabolic symptoms, insulin resistance, and inflammation compared with such students who attend schools that do not emphasize diversity. Conversely, when academically oriented Black students attended schools that had larger Black-White gaps in punishment rates, these students had higher levels of insulin resistance in adulthood compared with those who attended schools with relatively equal punishment rates. These findings suggest that the efforts that schools make to create fair, equitable, and inclusive environments have implications for students’ physical health, particularly for students from racial and ethnic minority groups.

The present study investigated associations between school-level racial disparities in belonging and cardiometabolic health into adulthood in a prospective national study of Black and White students across the United States. Specifically, we tested whether Black students who attended schools with smaller Black-White disparities in high school belonging would have lower risk of adult diabetes and metabolic syndrome (MetS) relative to those who attended schools with larger Black-White gaps in school belonging. In contrast, we hypothesized that racial disparities in school belonging would not be associated with the cardiometabolic health of White students.

Methods

Sample

In this cohort study, data were used from waves 1 and 4 of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, a nationally representative sample of children, adolescents, and young adults in grades 7 to 12 in 1994 and 1995 (see eAppendix 1 in the Supplement for details). The study involved in-school questionnaires, in-home interviews, and school administrator questionnaires at wave 1 as well as biological data collection in 2008 at wave 4. The sample for this study consisted of participants who self-identified as non-Hispanic Black or non-Hispanic White (all others were excluded from analyses). Race was coded as 0 for non-Hispanic White and 1 for non-Hispanic Black. The total analytic sample consisted of 4830 individuals (when diabetes was tested as an outcome) and 4076 individuals (when MetS was tested as an outcome) who had complete data on relevant variables at waves 1 and 4. This study was approved by the University of North Carolina institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from participants. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was followed.

Measures

School-Level Belonging

At wave 1, all students at school completed a 5-item school belonging questionnaire. The mean score of each Black student at a school was calculated to create a Black school-level belonging score, and the same was done for White students. A school’s Black-White belonging gap was calculated as the Black belonging score minus the White belonging score. More negative numbers indicated a greater gap between Black and White belonging in the direction of Black students experiencing lower levels of school belonging than White students at the same school.

Adult Type 2 Diabetes

At wave 4, field researchers collected whole-blood spot samples from a finger capillary prick for analysis of glycosylated hemoglobin and glucose. Criteria for diabetes are presented in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement and are in line with those of previous National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health studies. A total of 395 of 4830 participants (8.2%) were classified as having diabetes.

Adult MetS

At wave 4, MetS was diagnosed as described in eAppendix 1 of the Supplement. Because MetS can fall along a continuum of severity, a MetS score for number of risk factors for metabolic syndrome was calculated (number of signs exceeding threshold).

Covariates

Individual-level covariates included participant age, sex, body mass index, and, in supplemental analyses, individual school belonging score. School-level covariates included school size, percentage of Black teachers, percentage of Black students, and the overall school-level belonging score.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted from June 14 to August 13, 2021, with Mplus version 8.2 (Muthén & Muthén), using the type = COMPLEX command with sampling weights from wave 4 and identifying the included study sample as a subpopulation of the original survey-weighted cohort. The models specified clustering at the level of school to account for the nonindependence of observations among participants attending the same schools. For the binary outcome of diabetes, we used a logistic regression model with a logit link. For the number of risk factors for MetS, we used a Poisson regression model with a log-linear link. Models included the independent variables of school-level Black-White belonging gap (continuous variable) and student race (0 = White, 1 = Black), as well as the interaction of Black-White belonging gap × race. All models included the covariates described earlier. We followed standard guidelines for interpreting significant interactions, which involved plotting estimated outcome values (probabilities of diabetes and number of risk factors for MetS) from low (−2 SDs below the mean) to high (2 SDs above the mean) values of the school-level Black-White belonging gap for each race. School belonging was standardized to facilitate interpretation. P values were calculated with 2-sided t tests (estimate/SE) and statistical significance was indicated by P < .05.

Results

Diabetes

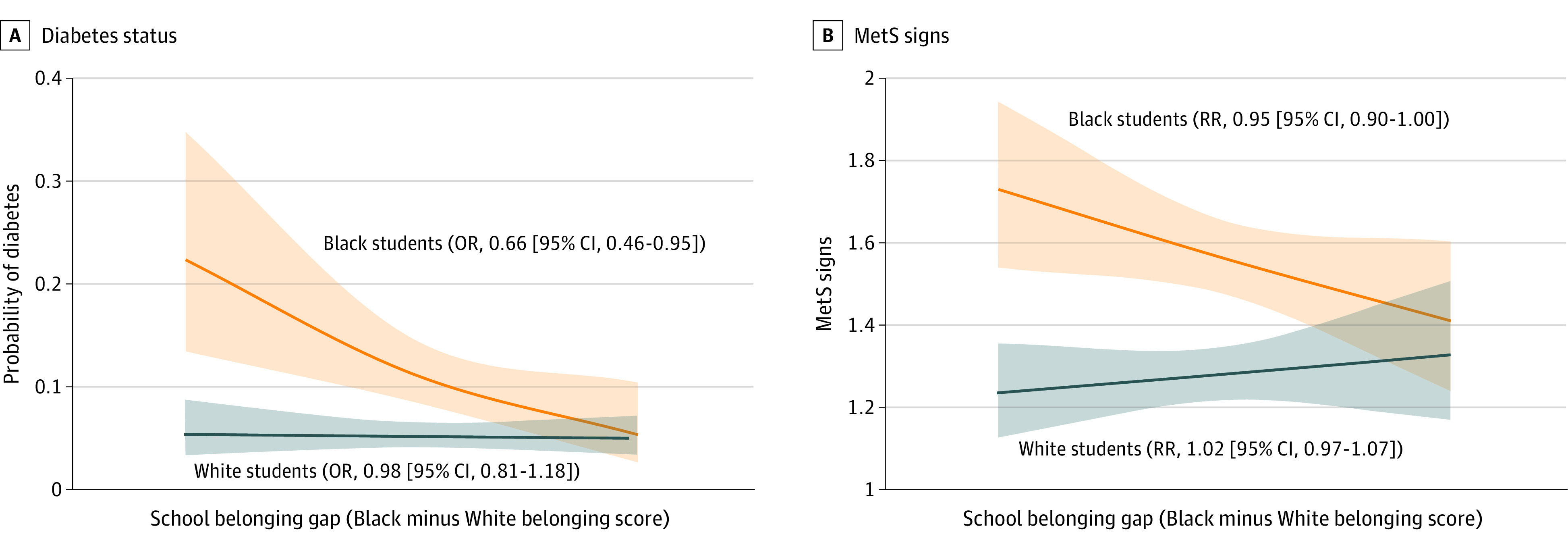

The study included 4830 students. For wave 1, mean (SD) age was 16.1 (1.7) years, and for wave 4, 29.0 (1.7) years. A total of 2216 students were male (45.9%), 2614 were female (54.1%), 2219 were non-Hispanic Black (45.9%), and 2611 were non-Hispanic White (54.1%). We tested associations of the Black-White gap in school belonging, participant race, and their interaction with risk for diabetes at 24 to 32 years of age. See Table 1 and Table 2 and eAppendix 2 in the Supplement for descriptive information about the study. There was a significant interaction between race and the Black-White school belonging gap (β = −0.39; 95% CI, −0.73 to −0.04; P = .03). The school belonging gap was not associated with risk of adult diabetes among non-Hispanic White participants (odds ratio, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.81-1.18]). However, when non-Hispanic Black students attended schools with a larger Black-White gap in school belonging (2 SDs below the mean, or more negative values in the Black-White difference score), they had a higher risk of adult diabetes compared with those who attended schools with smaller Black-White gaps in belonging (2 SDs above the mean) (odds ratio, 0.66 [95% CI, 0.46-0.95]) (Table 3 and Figure).

Table 1. School-Level Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| School, No. (%) | 54 (100) |

| Size, No. (%) | |

| Small (1-400 students) | 8 (14.8) |

| Medium (401-1000 students) | 27 (50.0) |

| Large (1001-4000 students) | 19 (35.2) |

| Black teachers, % | 16.56 (19.41) |

| Non-Hispanic Black students, % | 25.98 (19.75) |

| School belonging | |

| School-level mean value | 3.49 (0.18) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 3.51 (0.21) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3.40 (0.22) |

| Black-White gap | −0.11 (0.20) |

Table 2. Individual-Level Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Students, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | |

| Total | 2611 (54.1) | 2219 (45.9) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1264 (48.4) | 952 (42.9) |

| Female | 1347 (51.6) | 1267 (57.1) |

| Wave 1, mean (SD) | ||

| Age, y | 16.12 (1.69) | 16.04 (1.66) |

| BMI | 22.29 (4.45) | 23.31 (4.80) |

| School belonging | 3.65 (0.77) | 3.62 (0.75) |

| Wave 4 | ||

| Diabetes | 116 (4.4) | 279 (12.6) |

| Metabolic syndrome, mean (SD) | 1.29 (1.15) | 1.60 (1.13) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Table 3. Black-White Gap in School Belonging and Race as Factors Associated With Adult Cardiometabolic Risk.

| Factora | Diabetes, OR (95% CI) | No. of risk factors for metabolic syndrome, RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| No. | 4830 | 4076 |

| Primary results | ||

| Black-White gap in school belonging (White), 1 SD | 0.98 (0.81-1.18) | 1.02 (0.97-1.07) |

| Black-White gap in school belonging (Black), 1 SD | 0.66 (0.46-0.95) | 0.95 (0.90-1.00) |

| Covariates | ||

| Male sex | 0.97 (0.67-1.40) | 1.88 (1.74-2.03) |

| Age (wave 1), 1 y | 1.03 (0.95-1.11) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) |

| BMI (wave 1), 1 | 1.08 (1.06-1.10) | 1.05 (1.04-1.05) |

| School size (small, medium, or large) | 1.07 (0.81-1.41) | 0.92 (0.86-0.97) |

| School % of Black teachers, 1% | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) |

| School % of non-Hispanic Black students, 1% | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) |

| School-level mean school belonging, 1 SD | 0.93 (0.79-1.09) | 0.97 (0.93-1.00) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); OR, odds ratio; RR, rate ratio.

For each factor, the contrast is provided.

Figure. Associations of Racial Gap in School Belonging With Cardiometabolic Outcomes Among Non-Hispanic Black and Non-Hispanic White Students.

Diabetes status (A) and metabolic syndrome (MetS) signs (B) (at 24-32 years) as a function of the Black-White gap in school belonging (at 12-20 years) and race. The x-axis ranges from −2 SDs (Black students having much lower levels of belonging than White students) to 2 SDs. Shaded areas indicate 95% CIs. OR indicates odds ratio; RR, rate ratio.

Metabolic Syndrome

There was a significant interaction of school belonging gap by race for MetS (β = −0.07; 95% CI, −0.13 to −0.01; P = .02). The gap in belonging was not associated with the number of risk factors for MetS among non-Hispanic White participants (rate ratio, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.97-1.07]). In contrast, when non-Hispanic Black students attended schools that had a larger Black-White gap in school belonging, they had a higher number of risk factors for MetS as adults compared with those who attended schools with smaller Black-White gaps in belonging (rate ratio, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.90-1.00]) (Table 3 and Figure).

Supplemental Analyses

To test whether associations might be explained by participants’ own perceptions of school belonging, we added individual-level school belonging, as well as its interaction with race, in the regression models. All school-level belonging interactions (for diabetes, β = −0.39 [95% CI, −0.74 to −0.04; P = .03]; for MetS, β = −0.07 [95% CI, −0.13 to −0.01; P = .02]) and simple main-effects contrasts reported earlier remained significant (diabetes school belonging gap for non-Hispanic Black students: odds ratio, 0.66 [95% CI, 0.47-0.95]; MetS school belonging gap for non-Hispanic Black students: odds ratio, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.90-1.00]) (see eTable 1 in the Supplement for details). Additional information about controlling for school racial and ethnic composition is included in eAppendix 2 and eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Discussion

The present study found that when Black students attended schools in which there was a greater gap between Black and White students’ sense of school belonging, they had an increased risk for diabetes and more risk factors for MetS in adulthood 13 years later compared with Black students who attended schools with a smaller racial gap in school belonging. In contrast, racial disparities in school belonging were not associated with the cardiometabolic health of White students. These associations accounted for a number of individual-level factors, including sex and body mass index, as well as school-level factors, including the racial composition of students and teachers. Results also held when we controlled for schools’ mean belonging scores, which suggests that the overall mean belonging score in a school can mask systemic variability in social experiences by groups. The results of the present study emphasize that it is the racial disparities in school belonging (the difference between how well Black students feel they belong compared with White students at the same school) that are associated with cardiometabolic health in young adulthood, particularly for individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups.

Differences in diabetes and MetS were found for school-level racial disparities in belonging over and above individual-level belonging. Individual school belonging refers to how well a particular student believes he or she is accepted, supported, and included by others. It is possible that individual perceptions are shaped more strongly by a student’s friendship circles, whereas school-level belonging more broadly captures the institutional social climate. Indeed, other researchers have posited that structural or institutional race-related factors can operate and affect health even without an individual’s awareness of it. Thus, these findings highlight the importance of studies that go beyond the individual level and seek to understand the role that institutional-level factors play in health disparities.

How do racial disparities in school belonging come to be associated with adult diabetes and MetS in students from racial and ethnic minority groups? In schools with a greater racial gap in belonging, students from racial and ethnic minority groups may witness poorer-quality interracial interactions among teachers and peers, a school system that disproportionately punishes students from racial and ethnic minority groups and excludes them from opportunities, and environments that are dismissive of the cultural values and backgrounds of students from racial and ethnic minority groups. In these environments, students from racial and ethnic minority groups may experience differential treatment, threats to their social identity, and reminders of ways in which their social group is not as valued. In contrast, schools with a smaller racial gap in belonging may foster a more positive and welcoming school climate by communicating their commitment to diversity and inclusion explicitly, by conveying an equal status and equal opportunities for participation for students from all groups, and by including diverse cultural perspectives in school curricula and activities.

In turn, the weathering theory of health disparities posits that health develops in response to social, physical, and economic environmental conditions and, in particular, that population health is affected by people’s experiences with social marginalization. Weathering of bodies is thought to be intensified by exposure to multiple, persistent stressors that are experienced when institutions stigmatize and disadvantage certain groups (eg, in the school setting for students from racial and ethnic minority groups). These stressors dysregulate physiologic systems, increasing health vulnerability and leading to the early onset of health problems in these groups. For example, these experiences are associated with physiologic stress profiles, including heightened inflammation, which over time is known to be associated with cardiometabolic outcomes, such as insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, and with health-compromising behaviors, including unhealthy eating behaviors and sedentary lifestyles that are also associated with diabetes and other cardiometabolic disorders over time. A recent review found support for the weathering hypothesis across a variety of health outcomes.

Consistent with the present study, other empirical studies have found support for the associations between structural or institutional race-related factors and health outcomes in adults. For example, Black individuals living in a state or county with higher levels of structural racism had higher levels of body mass index and were more likely to have had a myocardial infarction. Neighborhoods that have higher levels of racial segregation have a larger Black-White gap in hypertension rates. Furthermore, neighborhood-level social factors (eg, violence) have been found to be associated with inflammatory markers and type 2 diabetes beyond individual-level factors (eg, personal exposure to violence), consistent with the present study’s findings of persistent school-level associations after controlling for individual factors. Similarly, in the school domain, school-level belonging has been positively associated with student optimism and negatively associated with bullying beyond individual-level belonging.

Although, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine how racial disparities in school belonging are associated with physical health, the present findings are consistent with nascent evidence associating other aspects of school climate with health. For example, academically oriented Black students who attended schools with larger Black-White gaps in student punishment had higher levels of insulin resistance as adults. Lower levels of school connectedness also have been associated with greater adolescent substance use and, for adolescent girls, higher body mass index. In contrast, when schools make efforts to create more equitable and welcoming environments, students from racial and ethnic minority groups display better health outcomes. For example, students from racial and ethnic minority groups who attended schools that emphasized diversity (vs schools that did not) had lower levels of metabolic symptoms, insulin resistance, and inflammation. In addition, living in an ethnically based residential house (ie, where residents have a shared interest and/or membership in a cultural group) in college reduced the association between expected discrimination and inflammation among a sample of Latinx college students relative to matched nonresidents. Furthermore, a brief and simple intervention to increase school belonging improved the self-reported health of Black college students and reduced their number of physician visits during the next 3 years, providing causal evidence for the association between school belonging interventions and students’ health. Together with the present study’s findings, this literature suggests that a school’s racial climate may have implications for the health of students from racial and ethnic minority groups.

Associations of diabetes and MetS with racial disparities in school belonging were not observed among White students, possibly because they are typically not stigmatized in school settings and perceive the values of diversity as less relevant to them. Moreover, these findings are consistent with previous research showing that White students did not gain health benefits from attending schools that emphasized the value of diversity nor from an intervention that increased students’ sense of school belonging.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include the use of a national sample, data that spanned more than a decade, and the ability to combine survey data across the entire student population of numerous schools to compute school-level belonging. The limitations of this study include not having measures of diabetes or MetS at wave 1; hence, we were unable to examine change in cardiometabolic health from adolescence to adulthood. Also, this study was observational, and thus there is the possibility of unmeasured variables that could have confounded the findings. Such unmeasured variables would need to be ones that covary with racial disparities in school belonging and that are associated with the cardiometabolic health of Black but not White students. Future studies should test alternative explanations, perhaps associated with school extracurricular activities or resources, and should also conduct interventions fostering racial equity in school belonging that would enable stronger causal conclusions. Future studies should also investigate schools with different types of racial and ethnic compositions, such as majority Latinx or Asian schools. In addition, institutional climates are difficult to operationalize, and this study took only 1 approach (of many), the findings of which are open to alternative interpretations. Finally, this study focused on high school climates. Future research would benefit from examining how climates in other institutions, including colleges, workplaces, and health care settings, are associated with health among individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups.

Conclusions

The findings of this cohort study demonstrated that greater equality in school belonging across racial groups was prospectively associated with cardiometabolic outcomes, including lower risk of diabetes and MetS signs in adulthood, among individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups. These findings have implications for health disparities research, which has revealed striking differences by race across numerous health outcomes. The findings from the present study suggest that school climates provide 1 important context that may be associated with the emergence of health disparities and its persistence into adulthood. Targeting earlier periods of life for intervention, such as childhood and adolescence, may be an effective strategy for setting healthy trajectories that continue into adulthood. For example, to the extent that schools can cultivate more equitable, inclusive, and welcoming climates (eg, by incorporating culturally diverse perspectives into school curricula, by supporting clubs and activities for diverse student groups, and by encouraging subtle, brief reflections that normalize doubts about belonging), students from racial and ethnic minority groups may experience not only a more positive school environment but also better long-term cardiometabolic health. Because schools can reach large numbers of youth and because youth spend so much of their day in the school environment, such institutional-level approaches to reducing health disparities might have broader-reaching effects relative to individual- or family-level approaches. With heightened attention being paid to the 56 million US schoolchildren who experienced school disruptions because of COVID-19, understanding the implications of racial disparities in school belonging, particularly during this critical return-to-school year, may be important for establishing and ensuring the future health of our younger generation.

eAppendix 1. Methods

eAppendix 2. Results

eReferences.

eTable 1. Black-White Gap in School Belonging and Race as Predictors of Cardiometabolic Risk, Controlling Individual School Belonging

eTable 2. Black-White Gap in School Belonging and Race as Predictors of Cardiometabolic Risk, Controlling School Percentage of Hispanic and Other Race Students

References

- 1.Goodenow C. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents. Psychol Sch. 1993;30:79-90. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korpershoek H, Canrinus ET, Fokkens-Bruinsma M, de Boer H. The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: a meta-analytic review. Res Pap Educ. 2020;35:641-680. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joyce HD, Early TJ. The impact of school connectedness and teacher support on depressive symptoms in adolescents: a multilevel analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;39:101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marraccini ME, Brier ZMF. School connectedness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a systematic meta-analysis. Sch Psychol Q. 2017;32(1):5-21. doi: 10.1037/spq0000192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyberg A, Rajaleid K, Westerlund H, Hammarström A. Does social and professional establishment at age 30 mediate the association between school connectedness and family climate at age 16 and mental health symptoms at age 43? J Affect Disord. 2019;246:52-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNeely C, Falci C. School connectedness and the transition into and out of health-risk behavior among adolescents: a comparison of social belonging and teacher support. J Sch Health. 2004;74(7):284-292. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffgen G, Recchia S, Viechtbauer W. The link between school climate and violence in school: a meta-analytic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2013;18:300-309. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reaves S, McMahon SD, Duffy SN, Ruiz L. The test of time: a meta-analytic review of the relation between school climate and problem behavior. Aggress Violent Behav. 2018;39:100-108. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberle E, Guhn M, Gadermann AM, Thomson K, Schonert-Reichl KA. Positive mental health and supportive school environments: a population-level longitudinal study of dispositional optimism and school relationships in early adolescence. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:154-161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen J, McCabe L, Michelli NM, Pickeral T. School climate: research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teach Coll Rec. 2009;111:180-213. doi: 10.1177/016146810911100108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin G, Hansen TL. Racial and ethnic group differences in responses on the CHKS Closing the Achievement Gap Module (CTAG): California Healthy Kids Survey. Factsheet 14. WestEd Health and Human Development Program for the California Department of Education. Published 2012. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://data.calschls.org/resources/FACTSHEET-14_20120502.pdf

- 12.Voight A, Hanson T, O’Malley M, Adekanye L. The racial school climate gap: within-school disparities in students’ experiences of safety, support, and connectedness. Am J Community Psychol. 2015;56(3-4):252-267. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9751-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konold T, Cornell D, Shukla K, Huang F. Racial/ethnic differences in perceptions of school climate and its association with student engagement and peer aggression. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(6):1289-1303. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0576-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattison E, Aber MS. Closing the achievement gap: the association of racial climate with achievement and behavioral outcomes. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;40(1-2):1-12. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9128-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldsmith PA. Schools’ racial mix, students’ optimism, and the Black-White and Latino-White achievement gaps. Sociol Educ. 2004;77(2):121-147. doi: 10.1177/003804070407700202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meier KJ, Wrinkle RD, Polinard JL. Representative bureaucracy and distributional equity: addressing the hard question. J Polit. 1999;61(4):1025-1039. doi: 10.2307/2647552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bottiani JH, Bradshaw CP, Mendelson T. A multilevel examination of racial disparities in high school discipline: Black and White adolescents’ perceived equity, school belonging, and adjustment problems. J Educ Psychol. 2017;109(4):532-545. doi: 10.1037/edu0000155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slopen N, Heard-Garris N. Structural racism and pediatric health—a call for research to confront the origins of racial disparities in health. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(1):13-15. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geronimus AT, Pearson JA, Linnenbringer E, et al. Weathering in Detroit: place, race, ethnicity, and poverty as conceptually fluctuating social constructs shaping variation in allostatic load. Milbank Q. 2020;98(4):1171-1218. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):826-833. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine CS, Markus HR, Austin MK, Chen E, Miller GE. Students of color show health advantages when they attend schools that emphasize the value of diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(13):6013-6018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812068116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen E, Brody GH, Yu T, Hoffer LC, Russak-Pribble A, Miller GE. Disproportionate school punishment and significant life outcomes: a prospective analysis of Black youth. Psychol Sci. 2021;32(9):1375-1390. doi: 10.1177/0956797621998308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furlong MJ, O’Brennan LM, You S. Psychometric properties of the Add Health School Connectedness Scale for 18 sociocultural groups. Psychol Sch. 2011;48:986-997. doi: 10.1002/pits.20609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galliher RV, Rostosky SS, Hughes HK. School belonging, self esteem, and depressive symptoms in adolescents: an examination of sex, sexual attraction status, and urbanicity. J Youth Adolesc. 2004;33:235-245. doi: 10.1023/B:JOYO.0000025322.11510.9d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Georgiades K, Boyle MH, Fife KA. Emotional and behavioral problems among adolescent students: the role of immigrant, racial/ethnic congruence and belongingness in schools. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(9):1473-1492. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9868-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823-832. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550100049038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brody GH, Yu T, Miller GE, Chen E. Resilience in adolescence, health, and psychosocial outcomes. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20161042. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodman E. Metabolic syndrome and the mismeasure of risk. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(6):538-540. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthen BO, Muthen LK. Mplus Users’ Guide (Version 8). Muthen & Muthen; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slaten CD, Ferguson JK, Allen KA, Brodrick DV, Waters L. School belonging: a review of the history, current trends, and future directions. Educ Developmental Psychol. 2016;33(1):1-15. doi: 10.1017/edp.2016.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adkins-Jackson PB, Chantarat T, Bailey ZD, Ponce NA. Measuring structural racism: a guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191(4):539-547. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okonofua JA, Eberhardt JL. Two strikes: race and the disciplining of young students. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(5):617-624. doi: 10.1177/0956797615570365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steele DM, Cohn-Vargas B. Identity Safe Classrooms, Grades K-5: Places to Belong and Learn. Corwin Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher BW, Dawson-Edwards C, Higgins EM, Swartz K. Who belongs in school? examining the link between Black and White racial disparities in sense of school belonging and suspension. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(5):1481-1499. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geronimus AT, James SA, Destin M, et al. Jedi public health: co-creating an identity-safe culture to promote health equity. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:105-116. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gray DL, Hope EC, Matthews JS. Black and belonging at school: a case for interpersonal, instructional, and institutional opportunity structures. Educ Psychol. 2018;53(2):1-17. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2017.1421466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuhlman KR, Horn SR, Chiang JJ, Bower JE. Early life adversity exposure and circulating markers of inflammation in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;86:30-42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen E, Brody GH, Miller GE. What are the health consequences of upward mobility? Annu Rev Psychol. 2022;73:599-628. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-033020-122814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsalamandris S, Antonopoulos AS, Oikonomou E, et al. The role of inflammation in diabetes: current concepts and future perspectives. Eur Cardiol. 2019;14(1):50-59. doi: 10.15420/ecr.2018.33.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1793-1801. doi: 10.1172/JCI29069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill DC, Moss RH, Sykes-Muskett B, Conner M, O’Connor DB. Stress and eating behaviors in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite. 2018;123:14-22. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Sinha R. The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Med. 2014;44(1):81-121. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0090-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23(11-12):887-894. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2012;55(11):2895-2905. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sami W, Ansari T, Butt NS, Hamid MRA. Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2017;11(2):65-71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forde AT, Crookes DM, Suglia SF, Demmer RT. The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;33:1-18.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dougherty GB, Golden SH, Gross AL, Colantuoni E, Dean LT. Measuring structural racism and its association with BMI. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(4):530-537. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lukachko A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:42-50. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kershaw KN, Diez Roux AV, Burgard SA, Lisabeth LD, Mujahid MS, Schulz AJ. Metropolitan-level racial residential segregation and Black-White disparities in hypertension. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(5):537-545. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finegood ED, Chen E, Kish J, et al. Community violence and cellular and cytokine indicators of inflammation in adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;115:104628. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gebreab SY, Hickson DA, Sims M, et al. Neighborhood social and physical environments and type 2 diabetes mellitus in African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Health Place. 2017;43:128-137. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Konishi C, Miyazaki Y, Hymel S, Waterhouse T. Investigating associations between school climate and bullying in secondary schools: multilevel contextual effects modeling. Sch Psychol Int. 2017;38:240-263. doi: 10.1177/0143034316688730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richmond TK, Milliren C, Walls CE, Kawachi I. School social capital and body mass index in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Sch Health. 2014;84(12):759-768. doi: 10.1111/josh.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rheinschmidt-Same M, John-Henderson NA, Mendoza-Denton R. Ethnically-based theme house residency and expected discrimination predict downstream markers of inflammation among college students. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2017;8:102-111. doi: 10.1177/1948550616662130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walton GM, Cohen GL. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science. 2011;331(6023):1447-1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1198364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plaut VC, Garnett FG, Buffardi LE, Sanchez-Burks J. “What about me?” perceptions of exclusion and whites’ reactions to multiculturalism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101(2):337-353. doi: 10.1037/a0022832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407-411. doi: 10.1037/hea0000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69-101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reynolds AJ, Temple JA, Ou SR, et al. Effects of a school-based, early childhood intervention on adult health and well-being: a 19-year follow-up of low-income families. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(8):730-739. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Methods

eAppendix 2. Results

eReferences.

eTable 1. Black-White Gap in School Belonging and Race as Predictors of Cardiometabolic Risk, Controlling Individual School Belonging

eTable 2. Black-White Gap in School Belonging and Race as Predictors of Cardiometabolic Risk, Controlling School Percentage of Hispanic and Other Race Students