Key Points

Question

In patients with cirrhosis who have undergone liver transplant, what is the association between frailty, before and after transplant, and posttransplant global functional health?

Findings

In this cohort study of 358 liver transplant recipients, pre- and 1-year posttransplant frailty were associated with posttransplant global functional health. Pretransplant frailty was strongly associated with frailty 1 year after liver transplant.

Meaning

The study results potentially provide a foundation for interventions and therapeutics that target frailty that are administered pre- and/or early posttransplant that may improve the health and well-being of liver transplant recipients.

Abstract

Importance

Frailty has been recognized as a risk factor for mortality after liver transplant (LT) but little is known of its association with functional status and health-related quality of life (HRQL), termed global functional health, in LT recipients.

Objective

To evaluate the association between pre-LT and post-LT frailty with post-LT global functional health.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective cohort study was conducted at 8 US LT centers and included adults who underwent LT from October 2016 to February 2020.

Exposures

Frail was defined by a pre-LT Liver Frailty Index (LFI) score of 4.5 or greater.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Global functional health at 1 year after LT, assessed using surveys (Short Form-36 [SF-36; summarized by physical component scores (PFC) and mental component summary scores (MCS)], Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale) and performance-based tests (LFI, Fried Frailty Phenotype, and Short Physical Performance Battery).

Results

Of 358 LT recipients (median [IQR] age, 60 [53-65] years; 115 women [32%]; 25 [7%] Asian/Pacific Islander, 21 [6%] Black, 54 [15%] Hispanic White, and 243 [68%] non-Hispanic White individuals), 68 (19%) had frailty pre-LT. At 1 year post-LT, the median (IQR) PCS was lower in recipients who had frailty vs those without frailty pre-LT (42 [31-53] vs 50 [38-56]; P = .002), but the median MCS was similar. In multivariable regression, pre-LT frailty was associated with a −5.3-unit lower post-LT PCS (P < .001), but not MCS. The proportion who had difficulty with 1 or more Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (21% vs 10%) or who were unemployed/receiving disability (38% vs 29%) was higher in recipients with vs without frailty. In a subgroup of 210 recipients with LFI assessments 1 year post-LT, 13% had frailty at 1 year post-LT. Recipients who had frailty post-LT reported lower adjusted SF-36–PCS scores (coefficient, −11.4; P < .001) but not SF-36–MCS scores. Recipients of LT who had frailty vs those without frailty 1 year post-LT also had worse median (IQR) Fried Frailty Phenotype scores (1 [1-2] vs 1 [0-1]) and higher rates of functional impairment by a Short Physical Performance Battery of 9 or less (42% vs 20%; P = .01).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, pre-LT frailty was associated with worse global functional health 1 year after LT. The presence of frailty after LT was also associated with worse HRQL in physical, but not mental, subdomains. These data suggest that interventions and therapeutics that target frailty that are administered before and/or early post-LT may help to improve the health and well-being of LT recipients.

This cohort study examines the association between frailty before and after liver transplant with global functional health after liver transplant.

Introduction

To date, a primary focus of liver transplant on survival has delivered promising and ever improving outcomes: more than 90% live to 1 year, and more than 75% live to 5 years.1 However, for patients with cirrhosis who experience debilitating symptoms of weakness, fatigue, limited mobility, and decreased cognition, the hope of liver transplant extends beyond years lived. Patients considering liver transplant hope to regain health.

The World Health Organization has defined health as “the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”2 In other words, health is a concept that extends beyond survival alone. However, in liver transplant, to our knowledge, few studies have focused on recipients’ health and well-being after liver transplant. Thus, much less is known about which factors are most relevant to health and well-being in this population. As the quantity of posttransplant years of life improves, it is crucial to better understand the factors, particularly those that are modifiable, that contribute to patients’ quality of life during those posttransplant years.

We previously demonstrated that one of these potentially modifiable factors, frailty, is common and associated with mortality before and after liver transplant.3,4,5,6,7 But to our knowledge, whether frailty is also associated with poor health after liver transplant has not yet been investigated. We hypothesized that pretransplant frailty would be associated with worse posttransplant health and well-being, as measured by metrics of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and physical functioning, and that posttransplant frailty would also be associated with worse posttransplant health and well-being.

Methods

Study Population

We analyzed data from the Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FrAILT) study, a multicenter, prospective observational cohort study of liver transplant patients. Eligibility criteria included: (1) cirrhosis, (2) being listed for liver transplant, and (3) frailty assessment in the pretransplant ambulatory setting. Patients with severe cognitive dysfunction at screening (given concerns with providing informed consent) or who did not speak English, Spanish, or Chinese (given the availability of study materials) were excluded. The institutional review board at each participating site approved this study, which adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.8

Patients were included in this analysis if they underwent liver transplant from October 2016 to February 2020 and had complete patient-reported assessments of HRQL through 1 year posttransplant. The final cohort included participants from 8 US transplant centers: University of California, San Francisco (n = 146), Duke University (Durham, North Carolina; n = 47), Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois; n = 42), Columbia University Medical Center (New York, New York; n = 35), Baylor University Medical Center (Dallas, Texas; n = 34), Johns Hopkins Medical Institute (Baltimore, Maryland; n = 24), University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; n = 20), and Loma Linda University (Loma Linda, California; n = 10).

Study Procedures

Pretransplant

Physical frailty was assessed using the Liver Frailty Index (LFI; http://liverfrailtyindex.ucsf.edu), which comprises grip strength, chair stands, and balance.9 A higher LFI score indicates a greater degree of frailty. Participants underwent testing at every pretransplant visit, the timing of which was determined by the patient’s hepatologist independently of study participation. Frailty was defined by a previously established cut point of 4.5 or greater.7

Posttransplant

At 12 months after transplant, participants underwent an assessment of health and well-being using measures of disability, HRQL, and, in a subset of participants, physical function (eTable 1 in the Supplement). These measures were selected based on a conceptual model developed by Nagi10 and adapted by researchers in the field of lung transplant.11 In Nagi’s disablement model, organ impairment (eg, cirrhosis) is associated with functional limitations that can be tested in the research setting (eg, physical frailty), which are associated with limitations in performing necessary (or expected) tasks within one’s physical and sociocultural environment (eg, disability).10 The specific measures were:

-

Measures of disability and HRQL: administered to all participants, whether in person or via telemedicine.

Medical Outcomes Survey 36-item Short Form survey (SF-36), version 1. Includes 6 physical and 2 mental subdomains (from 0 to 100), with higher scores indicating better HRQL. Raw scores were converted to t scores based on US general population normative age-adjusted and sex-adjusted scores. Physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores were created from the subdomains using publicly available code.12 We considered 5 SF-36 points as the minimally important difference.13

Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs.14,15 Participants were asked if they were able to perform each of the 6 ADLs and 8 IADLs without assistance. Difficulty with 1 or more ADLs or IADLs was considered impairment.

Work status. Participants were asked, “Are you currently working, retired, or receiving disability?” Participants were grouped as not working if they were receiving disability and/or were unemployed.

-

Measures of physical frailty/function. Administered to participants (n = 210) who presented in person for their 1-year posttransplant visit. This cohort represented a subgroup (n = 210) of the total number of participants in this study due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which abruptly halted in-person visits during this research study.

The LFI9 score represented physical frailty.

Fried Frailty Phenotype.16 An established metric of physical frailty comprising gait speed, exhaustion, physical activity, unintentional weight loss, and weakness. A Fried Frailty Phenotype score of 3 or more indicates frailty.16,17

Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).18 An established metric of lower extremity strength19 comprising gait speed, balance, and chair stands. A SPPB cutoff of 9 or less was considered functionally impairment.17

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were reported as medians (IQRs, as indicated by the values at the first and third quartiles) or percentages and compared by frailty status using the Mann-Whitney or χ2/Fisher exact tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Select baseline characteristics were also reported and compared for participants who had assessments with performance-based metrics at the same time as survey-based metrics at 1 year posttransplant vs those who did not. The primary predictor was frailty, as measured by the pretransplant LFI at the time closest to transplant. We used linear regression to evaluate the association between pretransplant frailty and posttransplant HRQL. We then performed a multivariable analysis that included variables selected a priori that might confound the association between frailty and posttransplant HRQL: age, female sex, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and diabetes. Multinomial logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between pretransplant frailty and work status (not working vs working and retired vs working). Secondary analyses were conducted to evaluate the association between posttransplant frailty and posttransplant HRQL. A complete case analysis was used, as all covariates included in the multivariable models had complete data.

Two sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the stability of the associations between frailty and HRQL PCS and MCS scores. To assess whether the association between pretransplant frailty and the PCS and MCS scores differed significantly by time from assessment to transplant, an interaction analysis was performed by including a frailty by time interaction in the multivariable models (including both main effects simultaneously). We also conducted the primary regression analysis while controlling for center.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute). Hypothesis tests were 2-sided, and the significance threshold was set to P < .05.

Results

Data from 358 patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplant were analyzed for this study; 68 (19%) were classified as having frailty. Compared with those without frailty, patients with frailty differed significantly by race and ethnicity and etiology of cirrhosis, with higher percentages of non-Hispanic White individuals (87% vs 64%) and individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (44% vs 25%), and were less likely to have HCC (24% vs 38%; P = .02), but were similar by age, sex, and body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). Median (IQR) Model of End-stage Liver Disease/sodium scores at assessment (21 [15-26] vs 17 [12-22]; P < .001) and transplant (26 [19-31] vs 21 [15-27]; P < .001) were significantly higher in those with frailty vs without frailty, as were rates of ascites (60% vs 34%; P < .001) and hepatic encephalopathy (67% vs 51%; P = .02). The median (IQR) time from assessment to transplant was 1.7 months (0.5-3.6) in those with frailty and 2.8 (1.2-5.6) in those without frailty (P = .02) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the 358 Patients Categorized by Pretransplant Frailty as Defined by an LFI Score of 4.5 or Higher.

| Patient characteristicsa | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 358 [100%]) | Frailty index categories | |||

| Frailty (≥4.5) (n = 68 [19%]) | No frailty (<4.5) (n = 290 [81%]) | |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 60 (53-65) | 60 (54-66) | 60 (53-64) | .36 |

| Female | 115 (32) | 26 (38) | 89 (31) | .23 |

| Male | 243 (68) | 42 (62) | 201 (69) | .23 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 24 (7) | 2 (3) | 22 (8) | .004 |

| Black | 20 (6) | 1 (2) | 19 (7) | |

| Hispanic White | 55 (15) | 4 (6) | 51 (17) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 245 (68) | 60 (87) | 185 (64) | |

| Other | 14 (4) | 1 (2) | 13 (4) | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 28 (25-32) | 29 (26-35) | 28 (25-32) | .16 |

| Etiology of liver disease | ||||

| Chronic hepatitis C | 76 (21) | 13 (19) | 63 (22) | .03 |

| Alcohol | 81 (23) | 11 (16) | 70 (24) | |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 102 (28) | 30 (44) | 72 (25) | |

| Cholestatic | 42 (12) | 7 (10) | 35 (12) | |

| Other | 57 (16) | 7 (11) | 50 (17) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 127 (36) | 16 (24) | 111 (38) | .02 |

| MELDNa, median (IQR) | ||||

| At assessment | 18 (12-23) | 21 (15-26) | 17 (12-22) | <.001 |

| At transplant | 22 (16-28) | 26 (19-31) | 21 (15-27) | <.001 |

| Last LFI (pretransplant), median (IQR) | 3.9 (3.4-4.3) | 4.9 (4.7-5.4) | 3.7 (3.3-4.1) | <.001 |

| Albumin level, median (IQR), g/dL | 3.2 (2.7-3.7) | 2.9 (2.5-3.5) | 3.2 (2.8-3.8) | <.001 |

| Ascites | 140 (39) | 41 (60) | 99 (34) | <.001 |

| Liver encephalopathy | 188 (54) | 43 (67) | 145 (51) | .02 |

| Transplant characteristics | ||||

| SLK | 17 (5) | 5 (7) | 12 (4) | .26 |

| LDLT | 66 (18) | 8 (12) | 58 (20) | .12 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; LFI, Liver Frailty Index; MELDNa, Model for End-stage Liver Disease-Sodium; SLK, simultaneous liver kidney transplant.

SI conversion factor: To convert albumin to g/L, multiply by 10.

Mann-Whitney or χ2 tests.

Posttransplant Metrics of Global Functional Health

Self-reported Metrics

SF-36

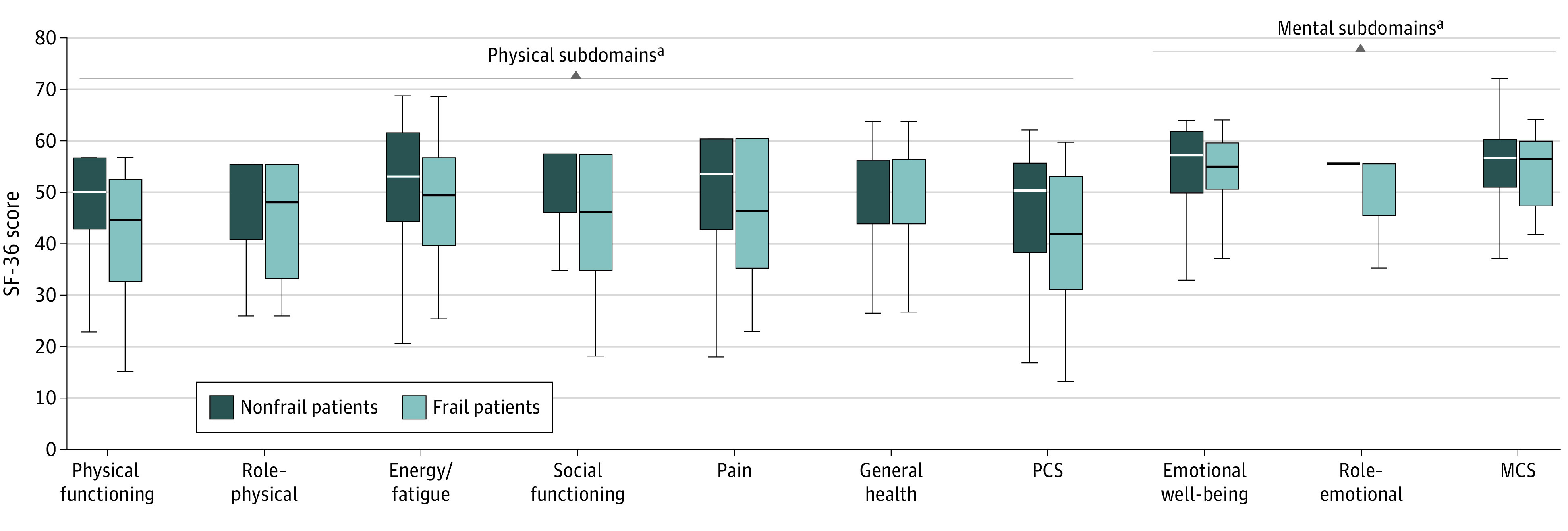

The Figure displays the scores of the SF-36 survey that participants reported at 1 year posttransplant as categorized by the 8 subdomains as well as the summary PCS and MCS scores. Compared with recipients without frailty, recipients with frailty reported significantly lower scores in each of the 6 physical subdomains; consequently, the median (IQR) PCS scores were lower in recipients with vs without frailty by nearly twice the minimally important difference (42 [31-53] vs 50 [38-56]; P = .002). Self-reported scores in the 2 mental subdomains were similar between the 2 groups, in which was associated with similar median MCS scores recipients with vs without frailty (57 [48-59] vs 57 [51-60]; P = .25) (Table 2).

Figure. Short Form-36 (SF-36) Subdomains by Frailty Status.

MCS indicates mental component scores; PCS, physical component scores.

aP < .05.

Table 2. Survey-Based Metrics of 1 Year Posttransplant Global Functional Health by Pretransplant Frailty Status in 358 FrAILT Study Participants Who Underwent Liver Transplant.

| Post-transplant metricsa | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 358 [100%]) | Pretransplant frailty status | |||

| Frailty (≥4.5) (n = 68 [19%]) | No frailty [<4.5] (n = 290 [81%]) | |||

| Difficulty with ≥1 ADL | 24 (7) | 8 (12) | 16 (6) | .10 |

| Needs assistance with individual ADL components | ||||

| Bathing | 11 (3) | 4 (6) | 7 (2) | .13 |

| Dressing | 14 (4) | 4 (6) | 10 (4) | .31 |

| Toileting | 7 (2) | 0 | 7 (2) | .36 |

| Transferring | 11 (3) | 1 (2) | 10 (4) | .70 |

| Continence | 22 (6) | 2 (3) | 20 (7) | .40 |

| Feeding | 8 (2) | 0 | 8 (3) | .36 |

| Difficulty with ≥1 IADL | 43 (12) | 14 (21) | 29 (10) | .02 |

| Needs assistance with individual IADL components | ||||

| Use phone | 3 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | .47 |

| Shopping | 21 (6) | 6 (9) | 15 (5) | .25 |

| Food preparation | 14 (4) | 5 (8) | 9 (3) | .15 |

| Housekeeping | 14 (4) | 4 (6) | 10 (4) | .31 |

| Laundry | 14 (4) | 3 (5) | 11 (4) | .73 |

| Transportation | 14 (4) | 5 (8) | 9 (3) | .15 |

| Manage medications | 17 (5) | 6 (9) | 11 (4) | .10 |

| Handle finances | 13 (4) | 5 (8) | 8 (3) | .08 |

| Work status | ||||

| Yes | 124 (35) | 14 (21) | 110 (38) | .02 |

| No | 109 (30) | 26 (38) | 83 (29) | |

| Retired | 125 (35) | 28 (41) | 97 (33) | |

Abbreviations: ADL, Activities of Daily Living; FrAILT, Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

Mann-Whitney or Fisher exact tests.

In univariable analysis, pretransplant frailty was associated with worse SF-36 PCS scores (coefficient, −5.33; 95% CI, −8.37 to −2.29; P < .001). This remained nearly unchanged (coefficient, −5.34; 95% CI, −8.39 to −2.30; P < .001) after adjustment for potential confounders (age, female sex, HCC status, and diabetes) (Table 3). Compared with those without frailty, patients with frailty, on average, had SF-36 PCS scores that were 5 points lower. Pretransplant frailty was not associated with MCS in either univariable (coefficient, −0.34; P = .58) or multivariable (coefficient, −1.60; P = .19) analyses (Table 3).

Table 3. Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations Between Variables and 1 Year Posttransplant Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores.

| Factor | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Physical component summary score | ||||

| Pretransplant frailty | −5.33 (−8.37 to −2.29) | <.001 | −5.34 (−8.39 to −2.30) | <.001 |

| Age, per year | −0.12 (−0.23 to −0.007) | .04 | −0.07 (−0.19 to 0.05) | .24 |

| Female sex | −2.40 (−4.98 to 0.19) | .07 | −2.83 (−5.39 to −0.27) | .03 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | −2.60 (−5.12 to −0.08) | .04 | −2.87 (−5.54 to −0.20) | .04 |

| Diabetes | −2.26 (−4.80 to 0.28) | .08 | −1.53 (−4.04 to 0.99) | .23 |

| Mental component summary score | ||||

| Pretransplant frailty | −0.34 (−1.51 to 0.84) | .58 | −1.60 (−4.01 to 0.82) | .19 |

| Age, per year | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.19) | .03 | 0.12 (0.03 to 0.22) | .01 |

| Female sex | −2.74 (−4.75 to −0.72) | .01 | −2.67 (−4.70 to −0.63) | .01 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | −0.55 (−2.54 to 1.43) | .58 | −2.03 (−4.15 to 0.09) | .06 |

| Diabetes | −0.37 (−2.37 to 1.62) | .71 | −0.62 (−2.61 to 1.38) | .54 |

Two sensitivity analyses were performed. Controlling for covariates, the association between pretransplant frailty and the PCS and MCS scores did not differ significantly by time from assessment to transplant (frailty to time interaction: estimate, 0.001; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.01; P = .89 for MCS; estimate, −0.01; 95% CI, −0.02 to 0.01; P = .41 for PCS). Controlling for center and covariates, PCS had a frailty regression coefficient of −5.03 (95% CI, −8.10 to −2.00; P = .001), and MCS had a frailty regression coefficient of −1.40 (95% CI, −3.83 to –1.04; P = .26).

Disability

Most participants reported independence of ADLs; there were no significant differences in abilities to perform ADLs without assistance at 1 year posttransplant between recipients with vs without frailty (Table 2). On the other hand, 14 participants with frailty (21%) reported difficulty with at least 1 IADL at 1 year posttransplant, compared with 29 (10%) participants without frailty (P = .02). Although differences in each individual posttransplant IADL did not meet statistical significance by pretransplant frailty status, there were more apparent differences in abilities to manage transportation, medications, and finances (Table 2).

Work Status

Work status 1 year after liver transplant differed significantly overall between participants with (26 unemployed/receiving disability [38%], 28 retired [41%], 14 employed [21%]) or without (83 unemployed/receiving disability [29%], 97 retired [33%], 110 employed [38%]) frailty (P = .02) (Table 2). Compared with participants without frailty and controlling for age, participants with frailty had 2.5 times the odds of not working (vs working; odds ratio, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.2-5.0; P = .01) and 2.0 times the odds of being retired (vs working; odds ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 0.9-4.4; P = .07), respectively.

Performance-Based Metrics

We analyzed data from the subgroup of FrAILT study participants who had assessments with performance-based metrics at the same time as survey-based metrics at 1 year posttransplant (n = 210). Participants with (vs without) performance-based metrics of global functional health were slightly younger (59 vs 61 years; P = .03) but were otherwise similar by demographic characteristics (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Median (IQR) PCS scores (48 [37-54] vs 52 [37-56]; P = .04) were lower in those with vs without performance metrics of global functional health. Median MCS scores were also lower, but both groups were substantially greater than the population mean of normative scores of 50 (56 [48-60] vs 58 [53-61]; P = .02).

LFI

At 1 year posttransplant, median (IQR) LFI scores were significantly worse in participants who displayed pretransplant frailty than those who did not (4.0 [3.5-4.6] vs 3.4 [2.8-3.8]) (Table 4). Few recipients (5%) who were frail pretransplant met criteria for being robust, whereas 43% with no frailty pretransplant met criteria for being robust (P < .001). Correspondingly, a greater proportion of recipients who had frailty pretransplant had frailty posttransplant (27 vs 10%).

Table 4. Performance-Based Metrics of 1 Year Posttransplant Global Functional Health by Pretransplant Frailty Status in the Subgroup of 210 FrAILT Study Participants.

| Metrics at 1 y posttransplanta | Median (IQR) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 210 [100%]) | Pretransplant frailty status | |||

| Frailty (≥4.5) (n = 41 [20%]) | No frailty (<4.5) (n = 169 [80%]) | |||

| LFI score (1 y post-transplant) | 3.4 (2.9 to 4.0) | 4.0 (3.5 to 4.6) | 3.4 (2.8 to 3.8) | <.001 |

| LFI components | ||||

| Grip strength z score | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.8) | −0.1 (−0.9 to 0.5) | 0.2 (−0.4 to 0.8) | .01 |

| Chair stands per second | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.5) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) | <.001 |

| % With balance <30 s | 10 | 19 | 8 | .05 |

| Frailty categories, % | ||||

| Robust | 36 | 5 | 43 | <.001 |

| Prefrailty | 51 | 68 | 47 | |

| Frailty | 13 | 27 | 10 | |

| Fried frailty phenotype | 1 (0 to 2) | 1 (1 to 2) | 1 (0 to 1) | .01 |

| % With Fried frailty phenotype ≥3 | 11 | 15 | 10 | .39 |

| Fried frailty phenotype components, % | ||||

| Weakness | 31 | 49 | 27 | .01 |

| Slowness | 12 | 15 | 12 | .60 |

| Exhausted | 17 | 20 | 16 | .64 |

| Low physical activity | 28 | 34 | 27 | .34 |

| Unintentional weight loss | 15 | 24 | 12 | .08 |

| Average walk speed, m/s | 4.2 (3.4 to 5.1) | 4.4 (3.6 to 5.9) | 4.1 (3.3 to 5.0) | .08 |

| SPPB | 12 (10 to 12) | 10 (9 to 12) | 12 (11 to 12) | <.001 |

| % With SPPB≤9 | 24 | 42 | 20 | .01 |

| SPPB components | ||||

| Walk score | 4 (4 to 4) | 4 (3 to 4) | 4 (4 to 4) | .04 |

| Balance score | 4 (4 to 4) | 4 (4 to 4) | 4 (4 to 4) | .02 |

| Chair stands score | 4 (3 to 4) | 3 (1 to 4) | 4 (3 to 4) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: FrAILT, Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation; LFI, Liver Frailty Index; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Mann-Whitney or Fisher exact tests.

Fried Frailty Phenotype

Participants who were frail pre-transplant had significantly worse median (IQR) Fried Frailty Phenotype scores at 1 year posttransplant than those without frailty pretransplant (1 [1-2] vs 1 [0-1]) but a similar proportion with Fried Frailty Phenotype score of 3 or more (15% vs 10%) (Table 4). The differences in composite Fried Frailty Phenotype scores between groups was largely driven by 2 components: grip strength and unintentional weight loss (Table 4). Average gait speed was similar between the 2 groups.

SPPB

Median (IQR) SPPB performance was worse in participants with frailty compared with those without frailty pretransplant (10 [9-12] vs 12 [11-12]). The proportion of participants who were impaired by an SPPB score of less than 10 was significantly higher among those with vs without frailty pretransplant (17 [42%] vs 33 [20%]) (Table 4).

Association Between Posttransplant Frailty and Posttransplant HRQL

Frailty at 1 year posttransplant was associated with posttransplant PCS but not MCS. In adjusted analyses, posttransplant frailty, which was defined by an LFI score of 4.5 or more at 1 year posttransplant was inversely associated with PCS (coefficient, −11.4; 95% CI, −15.5 to −7.3; P < .001) but not MCS (coefficient, −2.26; 95% CI, −6.02 to 1.51; P = .24). Compared with those without frailty, patients with frailty, on average, had SF-36 PCS scores that were 11 points lower.

Discussion

Research in liver transplant recipients has largely centered around the outcome of survival and the factors associated with more years of life. What is less well understood is how effectively liver transplant is associated with improved health and well-being, as defined by a more global assessment of physical function, disability, and HRQL. Defining factors that are associated with global functional health will identify areas to target to help patients achieve the outcomes they desire from liver transplant beyond survival alone.

Using data from the prospective multicenter FrAILT study, we identified pretransplant frailty as a major risk factor for unemployment, disability, and poorer HRQL after liver transplant. Furthermore, patients with frailty pretransplant also displayed higher rates of posttransplant frailty by LFI, Fried Frailty Phenotype, and SPPB scores. The results of the final analysis suggest that the presence of frailty at 1 year posttransplant was associated with worse physical HRQL that was nearly twice what is considered clinically important and independent of many of the pretransplant baseline characteristics that we believed may have otherwise confounded this association. While prior studies have established the association between the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), a metric that has been used in hepatology literature as a surrogate for frailty, and posttransplant mortality,20 the present study potentially advances the field by using an objective, performance-based metric of frailty that seems to be a more accurate metric of frailty than the KPS and avoids the weaknesses of a subjective metric, such as KPS, that renders it less suitable for transplant decision-making.21,22

In patients with cirrhosis, the frail phenotype has been conceptualized to be predominantly associated with the combination of undernutrition, muscle wasting, and neuromotor discoordination.23,24 These factors are respectively represented by the 3 tests of the LFI: grip strength, chair stands, and balance.9 These 3 tests assess physical function. So perhaps it is not surprising that, in our study, the LFI was associated with the posttransplant assessments of global health that clustered around physical function, such as questions from the SF-36 (“Does your health limit you in vigorous activities?”, “Do you feel full of pep?”), difficulty with completing IADLs without assistance, return to work, and the LFI itself. This study supports the relevance of Nagi’s conceptual model of disablement, in which functional impairments (in this case, frailty) are associated with worse disability and HRQL.

However, what was surprising to us was the lack of association between pretransplant frailty and posttransplant emotional health, despite the fact that frailty has been recognized to have psychological correlates in this population.24,25,26 While these findings could mean nothing more than a lack of an association between pretransplant frailty and posttransplant emotional health, we considered an alternative explanation: posttraumatic growth. In the field of psychology, posttraumatic growth is the “experience of positive psychological change that occurs as a result of highly challenging life crises.”27 Liver transplant recipients, having faced the possibility of death on the wait list, may feel greater optimism and life satisfaction once they are on the other side of the wait list. This may explain why aggregate scores for the MCS were higher than the population mean of 50. This is further supported by data in lung transplant recipients that demonstrated greater improvement in physical, but less for mental, HRQL subdomains.28

How can these data be incorporated into clinical transplant practice? We believe that frailty is a valuable prognostic factor because it is potentially modifiable.29 Pretransplant frailty assessments in this study were conducted in the ambulatory setting, where patients are more clinically stable, offering an opportunity to engage in prehabilitation. However, adherence to prehabilitative interventions in patients with cirrhosis has been reported to be low, likely because of competing demands of portal hypertensive complications, frequent hospitalizations, and difficulty with sustaining engagement for a long time.30 The study data demonstrating the association between posttransplant LFI and posttransplant HRQL PCS, along with relatively high self-reported emotional well-being, suggest that the ideal time for intervention may be immediately after transplant, when the patient has a functioning liver and resolving portal hypertensive complications. In other words, rehabilitation may be more effective than prehabilitation. Research and clinical programmatic efforts focused on early and intensive physical and nutritional interventions immediately after liver transplant are needed to better understand the logistics of implementation and the potential benefits of such an approach.

Patients in the study cohort with NAFLD displayed significantly higher rates of frailty than those without NAFLD as their primary etiology of cirrhosis. This is not surprising, as the components of metabolic syndrome are also known risk factors for frailty, and we have previously reported on the associations between NAFLD and frailty.31 We did not capture posttransplant comorbidities and the presence of posttransplant metabolic syndrome (PTMS) in this cohort, but future studies should seek to understand the association between posttransplant frailty and PTMS. Whether posttransplant rehabilitation can reduce the incidence of PTMS or whether preventing the development of PTMS can improve posttransplant frailty is an intriguing hypothesis to investigate.

Limitations

The study findings must be interpreted in the context of their limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study that included patients with at least 1 year of posttransplant follow-up and offered only a snapshot of posttransplant global functional health, and at a relatively short posttransplant interval. A longitudinal study evaluating changes in global functional health over time, such as has been done in lung transplant recipients,28 is needed. Second, we did not collect the full battery of global functional health metrics pretransplant, so we could not evaluate the pre-to-post transplant change in each of these metrics or pretransplant factors that would not be expected to reverse after liver transplant (eg, chronic musculoskeletal condition). However, prior studies have already demonstrated improvement in HRQL in liver transplant recipients from before to after liver transplant.32,33,34 Third, the FrAILT study only assessed frailty in the ambulatory setting, which was associated with variable timing of the pretransplant frailty assessment and transplant; our results cannot be generalized to patients who were evaluated in the inpatient setting. Lastly, as a result of the suspension of in-person visits due to the COVID-19 pandemic, only a subset of participants underwent posttransplant assessments of LFI, Fried Frailty Phenotype, and SPPB. We did not identify clinically significant demographic differences between those who did and did not have in-person posttransplant assessments. Those who had their 12-month posttransplant visit via telemedicine reported slightly better HRQL, suggesting that the shift to telemedicine was not negatively associated with their overall well-being.

Conclusions

This cohort study potentially offers insights into life beyond survival in liver transplant recipients. Taken together, the data suggest the benefits of liver transplant as a means to achieve overall acceptable global functional health for most patients. However, our analyses identified a subgroup of individuals who are vulnerable to suboptimal global functional health, those with frailty pretransplant, and offer a tool that can be used in clinical practice to identify them: the LFI. As the field moves closer to embracing models of transplant care that incorporate how a patient feels and functions, such as comanagement with palliative care or transplant survivorship programs,35,36,37,38 studies that investigate outcomes other than survival alone are needed. Lastly, the study data lay the foundation for interventions and therapeutics that target frailty that are administered before and/or early posttransplant to improve the global functional health in liver transplant recipients.

eTable 1. Metrics to represent global functional health in this study of liver transplant recipients

eTable 2. Select demographics and survey-based scores of participants, categorized by those who underwent testing with performance-based metrics at 1 year post-transplant and those did not

References

- 1.Kwong AJ, Kim WR, Lake JR, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2019 annual data report: liver. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(suppl 2):208-315. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO remains firmly committed to the principles set out in the preamble to the Constitution. Accessed November 4, 2022. https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution#:~:text=Health%20is%20a%20state%20of,belief%2C%20economic%20or%20social%20condition

- 3.Lai JC, Rahimi RS, Verna EC, et al. Frailty associated with waitlist mortality independent of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy in a multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(6):1675-1682. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai JC, Dodge JL, Kappus MR, et al. ; Multi-Center Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FRAILT) Study . Changes in frailty are associated with waitlist mortality in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2020;73(3):575-581. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai JC, Ganger DR, Volk ML, et al. Association of frailty and sex with wait list mortality in liver transplant candidates in the Multicenter Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FRAILT) study. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(3):256-262. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kardashian A, Ge J, McCulloch CE, et al. Identifying an optimal liver frailty index cutoff to predict waitlist mortality in liver transplant candidates. Hepatology. 2021;73(3):1132-1139. doi: 10.1002/hep.31406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai JC, Shui AM, Duarte-Rojo A, et al. Frailty, mortality, and healthcare utilization after liver transplantation: from the Multi-Center Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FRAILT) study. Hepatology. 2022;75(6):1471-1479. doi: 10.1002/hep.32268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghaferi AA, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM. STROBE Reporting Guidelines for Observational Studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6):577-578. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai JC, Covinsky KE, Dodge JL, et al. Development of a novel frailty index to predict mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2017;66(2):564-574. doi: 10.1002/hep.29219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagi SZ. A study in the evaluation of disability and rehabilitation potential: concepts, methods, and procedures. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1964;54(9):1568-1579. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.54.9.1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer JP, Blanc PD, Dean YM, et al. Development and validation of a lung transplant-specific disability questionnaire. Thorax. 2014;69(5):437-442. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Spritzer KL, Dixon WJ. A microcomputer program (sf36.exe) that generates SAS code for scoring the SF-36 Health Survey. Accessed June 29, 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/drafts/DRU1437.html

- 13.Singer JP, Singer LG. Quality of life in lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34(3):421-430. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai JC, Feng S, Terrault NA, Lizaola B, Hayssen H, Covinsky K. Frailty predicts waitlist mortality in liver transplant candidates. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(8):1870-1879. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85-M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavasini R, Guralnik J, Brown JC, et al. Short physical performance battery and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):215. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0763-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thuluvath PJ, Thuluvath AJ, Savva Y. Karnofsky performance status before and after liver transplantation predicts graft and patient survival. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):818-825. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu CQ, Yao F, Mohamad Y, et al. Evaluating the associations between the liver frailty index and Karnofsky performance status with waitlist mortality. Transplant Direct. 2021;7(2):e651. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang CW, Lai JC. Reporting functional status in UNOS: the weakness of the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(7):e13004-e2. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai JC, Sonnenday CJ, Tapper EB, et al. Frailty in liver transplantation: an expert opinion statement from the American Society of Transplantation Liver and Intestinal Community of Practice. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(7):1896-1906. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai JC, Tandon P, Bernal W, et al. Malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis: 2021 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2021;74(3):1611-1644. doi: 10.1002/hep.32049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cron DC, Friedman JF, Winder GS, et al. Depression and frailty in patients with end-stage liver disease referred for transplant evaluation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(6):1805-1811. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong RJ, Mohamad Y, Srisengfa YT, et al. Psychological contributors to the frail phenotype: The association between resilience and frailty in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(1):241-246. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004;15(1):1-18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singer JP, Katz PP, Soong A, et al. Effect of lung transplantation on health-related quality of life in the era of the lung allocation score: a U.S. prospective cohort study. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(5):1334-1345. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams FR, Berzigotti A, Lord JM, Lai JC, Armstrong MJ. Review article: impact of exercise on physical frailty in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(9):988-1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.15491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai JC, Dodge JL, Kappus MR, et al. A multicenter pilot randomized clinical trial of a home-based exercise program for patients with cirrhosis: the Strength Training Intervention (STRIVE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(4):717-722. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu CQ, Mohamad Y, Kappus MR, et al. The relationship between frailty and cirrhosis etiology: from the Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FRAILT) study. Liver Int. 2021;41(10):2467-2473. doi: 10.1111/liv.15006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bownik H, Saab S. Health-related quality of life after liver transplantation for adult recipients. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(S2)(suppl 2):S42-S49. doi: 10.1002/lt.21911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tome S, Wells JT, Said A, Lucey MR. Quality of life after liver transplantation: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2008;48(4):567-577. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onghena L, Develtere W, Poppe C, et al. Quality of life after liver transplantation: state of the art. World J Hepatol. 2016;8(18):749-756. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i18.749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai JC, Ufere NN, Bucuvalas JC. Liver transplant survivorship. Liver Transpl. 2020;26(8):1030-1033. doi: 10.1002/lt.25792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lieber SR, Kim HP, Baldelli L, et al. What survivorship means to liver transplant recipients: qualitative groundwork for a survivorship conceptual model. Liver Transpl. 2021;27(10):1454-1467. doi: 10.1002/lt.26088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lieber SR, Kim HP, Baldelli L, et al. Early survivorship after liver transplantation: a qualitative study identifying challenges in recovery from the patient and caregiver perspective. Liver Transpl. 2022;28(3):422-436. doi: 10.1002/lt.26303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogal SS, Hansen L, Patel A, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance: Palliative care and symptom-based management in decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2022;76(3):819-853. doi: 10.1002/hep.32378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Metrics to represent global functional health in this study of liver transplant recipients

eTable 2. Select demographics and survey-based scores of participants, categorized by those who underwent testing with performance-based metrics at 1 year post-transplant and those did not