Key Points

Question

Is pessary therapy noninferior to surgery in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse?

Findings

In this noninferiority randomized clinical trial that included 439 participants, subjective improvement was reported by 76.3% of participants in the pessary group and by 81.5% of participants in the surgery group at 24 months, a difference that did not meet the prespecified noninferiority margin of 10 percentage points.

Meaning

Among patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, an initial strategy of pessary therapy, compared with surgery, did not meet criteria for noninferiority with regard to patient-reported improvement at 24 months.

Abstract

Importance

Pelvic organ prolapse is a prevalent condition among women that negatively affects their quality of life. With increasing life expectancy, the global need for cost-effective care for women with pelvic organ prolapse will continue to increase.

Objective

To investigate whether treatment with a pessary is noninferior to surgery among patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The PEOPLE project was a noninferiority randomized clinical trial conducted in 21 participating hospitals in the Netherlands. A total of 1605 women with symptomatic stage 2 or greater pelvic organ prolapse were requested to participate between March 2015 through November 2019; 440 gave informed consent. Final 24-month follow-up ended at June 30, 2022.

Interventions

Two hundred eighteen participants were randomized to receive pessary treatment and 222 to surgery.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was subjective patient-reported improvement at 24 months, measured with the Patient Global Impression of Improvement scale, a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very much better to very much worse. This scale was dichotomized as successful, defined as much better or very much better, vs nonsuccessful treatment. The noninferiority margin was set at 10 percentage points risk difference. Data of crossover between therapies and adverse events were captured.

Results

Among 440 patients who were randomized (mean [SD] age, 64.7 [9.29] years), 173 (79.3%) in the pessary group and 162 (73.3%) in the surgery group completed the trial at 24 months. In the population, analyzed as randomized, subjective improvement was reported by 132 of 173 (76.3%) in the pessary group vs 132 of 162 (81.5%) in the surgery group (risk difference, −6.1% [1-sided 95% CI, −12.7 to ∞]; P value for noninferiority, .16). The per-protocol analysis showed a similar result for subjective improvement with 52 of 74 (70.3%) in the pessary group vs 125 of 150 (83.3%) in the surgery group (risk difference, −13.1% [1-sided 95% CI, −23.0 to ∞]; P value for noninferiority, .69). Crossover from pessary to surgery occurred among 118 of 218 (54.1%) participants. The most common adverse event among pessary users was discomfort (42.7%) vs urinary tract infection (9%) following surgery.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, an initial strategy of pessary therapy, compared with surgery, did not meet criteria for noninferiority with regard to patient-reported improvement at 24 months. Interpretation is limited by loss to follow-up and the large amount of participant crossover from pessary therapy to surgery.

Trial Registration

Netherlands Trial Register Identifier: NTR4883

This randomized clinical trial of adult women with stage 2 or greater pelvic organ prolapse compared the effects of treatment with surgery vs pessary.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is a prevalent condition among women, often causing bothersome vaginal bulge symptoms as well as urinary, bowel, or sexual dysfunction.1 The reported prevalence varies widely between studies, ranging from 3% to 50%.2

Pessary therapy and surgery are both effective treatment options for pelvic organ prolapse.3 Although pessary therapy is minimally invasive, a systematic review (2016) and another study performed in 2021, reported that adverse effects such as discomfort, pain, and excessive discharge were associated with discontinuation of treatment in as many as 24% to 49% of women within 12 to 24 months.4,5 Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse is associated with surgical complications and as many as 2 out of 10 women with pelvic organ prolapse experience recurrence of bothersome pelvic organ prolapse symptoms.6

Studies comparing pessary to surgery are scarce, observational in nature, have large variations in study design and outcome measures, and have high losses to follow-up.7,8,9,10 A recent observational cohort study performed by this research group, reported that more women reported subjective improvement following surgery as compared with pessary therapy.4 Two systematic reviews and the guideline from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence on the management of pelvic organ prolapse urge the need for randomized clinical trials with long-term follow-up to generate evidence about patient satisfaction following surgery and with pessary therapy for pelvic organ prolapse.3,11,12 Such trials would optimize treatment selection and facilitate counseling of patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse.

Thus, a randomized clinical trial comparing pessary and surgery in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse was performed. The hypothesis was that a strategy of pessary as initial therapy is noninferior to initial prolapse surgery. In this research article, the 24-month follow-up data of the multicenter randomized clinical trial are presented.

Methods

Trial Design

This trial was designed to investigate noninferiority of pessary therapy to surgery as treatment for pelvic organ prolapse. The study protocol is available online (Supplement 1).13 Ethical approval was obtained by the ethics committee of the Utrecht University Medical Center. The study was identified as highly relevant by the Dutch Urogynecology Research Consortium and a major patients’ organization on pelvic floor disorders (Bekkenbodem4all). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Eligible women were referred to the hospital by their general practitioner. Women with a prolapse stage of 2 or greater, according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System, and moderate to severe prolapse symptoms, defined as a prolapse domain score greater than 33 on the validated Dutch version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory, were included.14,15 Women with prior prolapse or incontinence surgery or prior pessary use were excluded. Coexisting stress urinary incontinence was not among the exclusion criteria. Before randomization, participants had to successfully complete a 30-minute pessary fitting trial to be eligible. During the inclusion period, many women declined participation in the trial because they wanted to make their own choice of treatment. Therefore, an observational cohort was started alongside the randomized clinical trial. Women who declined participation in the trial (because they desired to choose their treatment) were asked to participate in the observational cohort, of which the results have recently been published.4

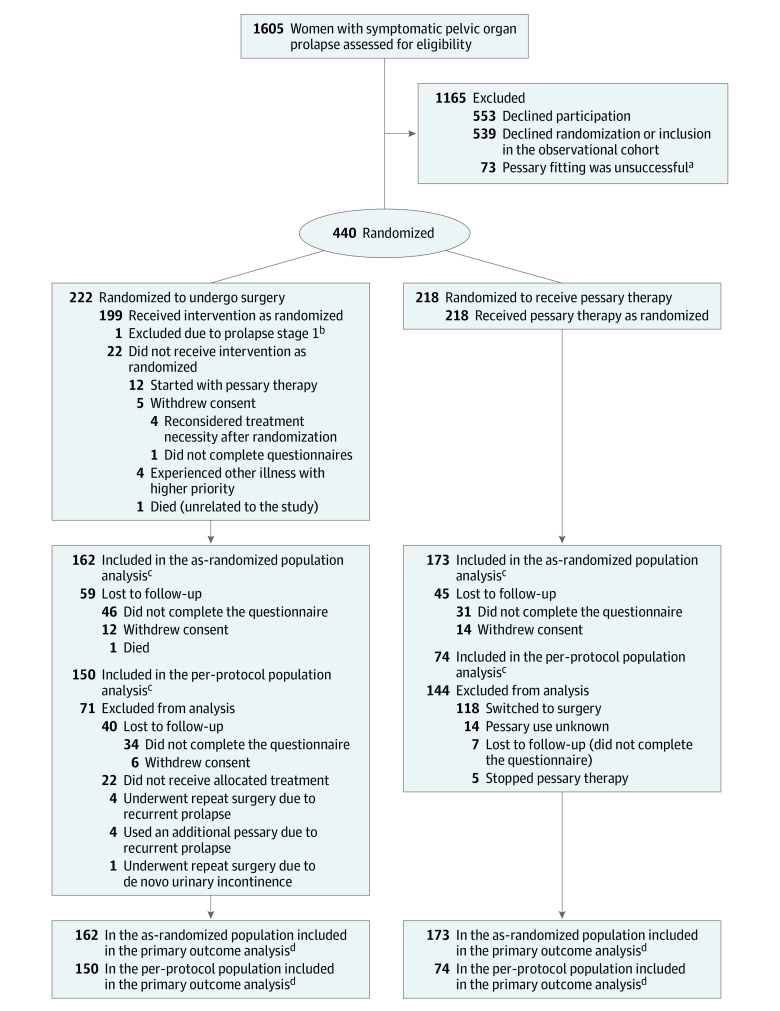

Randomization

After written informed consent, participants were randomized to either treatment group in a ratio of 1:1 (Figure 1) using a web-based randomization interface (ALEA) by a research nurse on site. After entering each woman’s initials and confirming inclusion criteria on the website, a unique number for randomization was generated. Randomization used random permuted block sizes of 2 and 4 and was stratified by center. Treatment allocation was not concealed.

Figure 1. Study Population Randomized to Surgery or Pessary Therapy.

aThese women were included in the cohort “fitting failure.”

bOne participant was excluded after randomization and excluded from all further analyses.

cThe as-analyzed population and the per-protocol population were used to assess the primary outcome. The full analysis set contained the entire population, as randomized with their initially allocated treatment, irrespective of adherence. The per-protocol population consisted of all women randomized to pessary therapy who continued pessary use at 24 months and all women randomized to surgery without receiving additional treatment (ie, pessary or repeat surgery). Results based on the as-randomized population, as well as those based on the per-protocol population were used for the overall conclusion about noninferiority of pessary treatment as compared with surgery in this trial.

dThe primary outcome was subjective improvement at 24 months, measured with the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I), a validated single-item questionnaire ranging from very much better to very much worse on a 7-point Likert scale.

Interventions

All participating gynecologists had fitted at least 100 pessaries and performed at least 100 vaginal pelvic organ prolapse surgeries prior to study initiation. Supportive and occlusive pessaries were allowed because both were proven to be effective.16 In case of pessary expulsion, a trial of another size/shape of pessary was offered. Frequency of pessary cleaning by women who self-managed, was left to personal judgement, with a minimum of at least every 4 months. If self-management was not preferred or possible, women were seen at least every 4 months by their gynecologist or general practitioner.

Surgical procedures were performed according to the Dutch guidelines.17 The surgical technique was left to the discretion of the gynecologist and determined in shared decision with the patient. Conventional transvaginal anterior colporrhaphy was the standard procedure for anterior vaginal wall prolapse, and posterior colporrhaphy was the standard procedure for posterior vaginal wall prolapse. For uterine descent, vaginal hysterectomy or uterine preserving techniques were performed.18,19 Abdominal repairs (ie, sacrocolpopexy) were also permitted.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was subjective improvement at 24 months, measured with the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I), a validated single-item questionnaire ranging from very much better to very much worse on a 7-point Likert scale.20 Subjective improvement was defined as a response of much better or very much better.21 PGI-I responses were collected at 12 and 24 months.

Secondary outcomes and the assessment tools used for measurement included perceived severity of symptoms (Patient Global Impression of Severity [PGI-S]), pelvic floor distress (Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory [PFDI-20]), disease-specific quality of life (Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire [PFIQ-7]), and sexual functioning (Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised [PISQ-IR]). Results of the general quality of life assessment, measured with the EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D), were used for a cost-effective analysis, which will be reported separately. All questionnaires were validated, reliable, and responsive to change in women with pelvic organ prolapse.22,23,24,25,26

The PGI-S assesses perceived severity of prolapse-related symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from nonsevere to severe. Reduction of at least 1 point from baseline was considered as success.27 The PGI-S was part of the initial study design because in Dutch practice it is always combined with the PGI-I. It was included in the statistical analysis plan although it was inadvertently not registered in the study protocol. The PFDI-20 assesses the patient’s experienced bother of pelvic organ prolapse on specific prolapse (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory [POPDI-6]), bladder (Urinary Distress Inventory, Short Form [UDI-6]), and bowel (Colorectal-Anal Distress Inventory [CRADI-8]) symptoms.28 The PFIQ-7 comprises 3 scales: the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ-7), the Urinary Impact Questionnaire (UIQ-7), and the Colorectal-Anal Impact Questionnaire (CRAIQ-7).28 Higher scores indicate more bothersome symptoms (PFDI-20) or more effect on daily activity (PFIQ-7); the subscale scores vary between 0 and 100, and the total scores range between 0 and 300.28 The minimally clinical important difference (MCID) for the summary score of the PFDI-20 was −22.9, and for the PFIQ-7, it was −28.6.23 The PISQ-IR evaluates sexually active and sexually inactive women.25,29 For sexually active women there are 6 domain-specific subscales with a higher score indicating better female sexual functioning. For sexually inactive women, there are 4 domain-specific subscales with a higher score indicating greater effect of pelvic organ prolapse on female sexual functioning.25 The subscale scores range from 1 to 4 or 1 to 5, depending on the specific domain (Table 1). For sexually active women, an overall summary score was calculated. The summary score ranges from 1 to 4.6 in case a sexual partner is present, and from 1 to 4.71 without a sexual partner.30 The MCID for the summary score of the PISQ-IR is only available for women receiving surgery and is 0.31 points.31 All responses to the secondary outcome questionnaires were collected at baseline, 12-month follow-up, and 24-month follow-up. Other secondary outcomes included crossover of therapy at 24 months and adverse events.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Baseline characteristics | Surgery group (n=221)a | Pessary group (n=218)a |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 64.7 (9.2) | 64.8 (9.5) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)b | 25.3 (23.2-27.9) | 25.2 (23.4-27.2) |

| Risk-increasing aspects, No. (%)c | 58 (26.2) | 71 (32.6) |

| Parity, median (IQR) [No.] | 2 (2-3) [220] | 2 (2-3) [215] |

| History of third- or fourth-degree perineal tear, No./total (%) | 8/200 (4.0) | 6/195 (3.1) |

| Postmenopausal, No./total (%) | 185/205 (90.2) | 186/201 (92.5) |

| History of gynecological surgery, No. (%) | 28 (12.7) | 22 (10.1) |

| Hysterectomy, No. (%) | 14 (6.3) | 14 (6.4) |

| Family history of prolapse, No./total (%) | 107/216 (49.5) | 106/218 (48.6) |

| Duration of symptoms, median (IQR), mo. [No.] | 6 (3-24) [216] | 6 (2-24) [211] |

| Vaginal atrophy, No./total (%) | 110/192 (57.3) | 106/187 (56.7) |

| Prolapse stage, No. (%) | ||

| 2 (Moderate) | 102 (46.2) | 85 (39.0) |

| ≥3 (Severe) | 119 (53.8) | 133 (61.0) |

| Site of prolapse, No. (%)d | ||

| Cystocele | 192 (86.9) | 193 (88.5) |

| Rectocele | 63 (28.5) | 69 (31.7) |

| Uterine prolapse | 104 (47.0) | 98 (44.9) |

| PGI-S, No. (%) | (n=205) | (n=205) |

| 1 (Not severe) | 9 (4.4) | 13 (6.3) |

| 2 (Mild) | 50 (24.4) | 48 (23.4) |

| 3 (Moderate) | 112 (54.6) | 99 (48.3) |

| 4 (Severe) | 34 (16.6) | 45 (22.0) |

| PFDI-20 domain score, mean (SD)e | (n=208) | (n=210) |

| POPDI-6 | 28.7 (15.6) | 29.5 (19.3) |

| CRADI-8 | 12.1 (12.6) | 13.9 (15.1) |

| UDI-6 | 25.2 (20.0) | 26.0 (22.0) |

| PFDI-20 total score | 65.9 (37.8) | 69.3 (45.7) |

| PFIQ-7 domain score, mean (SD)e | (n=205) | (n=208) |

| UIQ-7 | 16.6 (19.3) | 18.0 (20.5) |

| CRAIQ-7 | 6.4 (12.7) | 8.3 (16.3) |

| POPIQ-7 | 14.8 (18.3) | 14.4 (19.9) |

| PFIQ-7 total score | 37.9 (41.0) | 40.8 (47.5) |

| PISQ-IR sexually active, mean (SD)f | (n=112) | (n=116) |

| Partner-related: indicates assessment of partner-related impactsg | 3.4 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.6) |

| Condition-specific: indicates assessment of condition-specific impacts on activityh | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.6) |

| Global quality: indicates global quality rating of sexual qualityg | 2.6 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) |

| Condition impact: indicates condition-specific impact on sexual qualityg | 3.2 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.7) |

| Arousal-orgasm: indicates assessment of arousal, orgasmh | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.6) |

| Desire: indicates assessment of sexual desireh | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.6) |

| Summary scorei | 3.3 (0.3) | 3.3 (0.3) |

| PISQ-IR sexually inactive, mean (SD)j | (n=90) | (n=90) |

| Partner-related: indicates partner-related reasons for not being activeg | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.7 (1.0) |

| Condition-specific: indicates condition-specific reasons for not being activeg | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.9) |

| Global quality: indicates global quality rating of sexual qualityh | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.7) |

| Condition impact: indicates condition impact on sexual qualityg | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.8) |

Abbreviations: CRADI-8, Colorectal-Anal Distress Inventory; CRAIQ-7, Colorectal-Anal Impact Questionnaire; MCID, minimally clinical important difference; PFDI-20, Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory; PFIQ-7, Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire; PGI-S, Patient Global Impression of Severity; PISQ-IR, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA [International Urogynecological Association]-Revised; POPDI-6, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory; POPIQ-7, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire; UDI-6, Urinary Distress Inventory, Short Form; UIQ-7, Urinary Impact Questionnaire.

Indicates the number of patients except for categories where another number is reported.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Risk-increasing aspects includes at least 1 of the following: smoking, the use of antidepressants, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, and obesity.

Site of prolapse is not mutually exclusive.

For the PFDI-20 as well as for the PFIQ-7 subscale, scores range from 0 to 100. The total score is a sum of the subscale scores (range, 0-300). Higher scores indicate more impact of pelvic organ prolapse. The MCID for the total score of the PFDI-20 is −22.9 points, and for the the PFIQ-7, it is −28.6 points. The number of patients applies to all subscales.

Higher scores indicate better sexual functioning. The number of patients applies to all subscales.

Score range, 1 to 4.

Score range, 1 to 5.

The summary score ranges from 1 to 4.6 in cases with a sexual partner and from 1 to 4.71 without a sexual partner. The MCID for the summary score for women receiving surgery is 0.31 points.

Higher scores indicate greater impact of condition on sexual functioning. The number of patients applies to all subcategories.

Post Hoc Outcomes

Post hoc outcomes included change in sexual status (sexually active to sexually inactive or vice versa) and de novo dyspareunia. De novo dyspareunia was measured by comparing the response to the question “how often do you feel pain during intercourse” (question 11 on the PISQ-IR) between baseline and follow-up. De novo dyspareunia was defined if women answered never or rarely at baseline and sometimes, usually, or always at follow-up.

Data Collection

Patient-reported outcomes were collected at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 months, and 24 months. Limesurvey, version 2.6.7, was used for sending out questionnaires and storing the responses.32 On site, research nurses collected patient data from the electronic patient file and visits in electronic case report forms (OpenClinica). Serious adverse events were monitored and reported by the local investigator. Monitoring of the study was coordinated by the Dutch Research Consortium and executed by a qualified internal monitor.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was estimated for demonstrating noninferiority of pessary therapy compared with surgery against a margin of 10% risk difference. The noninferiority margin was based on the expectation that 80% of women would report successful treatment (either pessary or surgery) after 2 years.13,33 To achieve 80% power using a 1-sided α level of .05, recruitment of 396 patients was needed. Allowing for 10% loss in follow-up, 436 patients were planned to be recruited.

Statistical Analysis

The analyses followed a prespecified statistical analysis plan, and detailed information is available in Supplement 2. The primary outcome, measured using the PGI-I, was dichotomized as subjective improvement (much or very much) or not (all other reported values), and the risk difference was estimated. A 1-sided 95% CI was used to assess noninferiority, in line with the 1-sided test α of 5%. When the lower limit of the confidence interval of the risk difference included or extended below the noninferiority margin of −10%, noninferiority was not proven. The Farrington-Manning test was used to calculate a P value for noninferiority. Populations used for assessing the primary outcome were the population analyzed as randomized, as well as a per-protocol population. The full analysis set contained the entire population as randomized with their initially allocated treatment and irrespective of adherence. The per-protocol population consisted of all women randomized to pessary therapy who continued pessary use at 24 months, and all women randomized to surgery without receiving additional treatment (ie, pessary or repeat surgery). Both results based on the population as randomized, as well as those based on the per-protocol population, were used for the overall conclusion about noninferiority of pessary treatment as compared to surgery in this trial.

For dichotomous secondary outcomes, relative risks with 2-sided 95% CIs were estimated. Statistical testing was conducted using a χ2 test. Continuous secondary outcomes were analyzed using the t test or Mann-Whitney U test, depending on normality, and described as mean (SD) or median (IQR) as appropriate. Differences in PFDI-20, PFIQ-7, and PISQ-IR scores were reported with 2-sided 95% CIs obtained by bootstrapping (10 000 replications). A 2-sided P value of ≤.05 was considered as statistically significant.

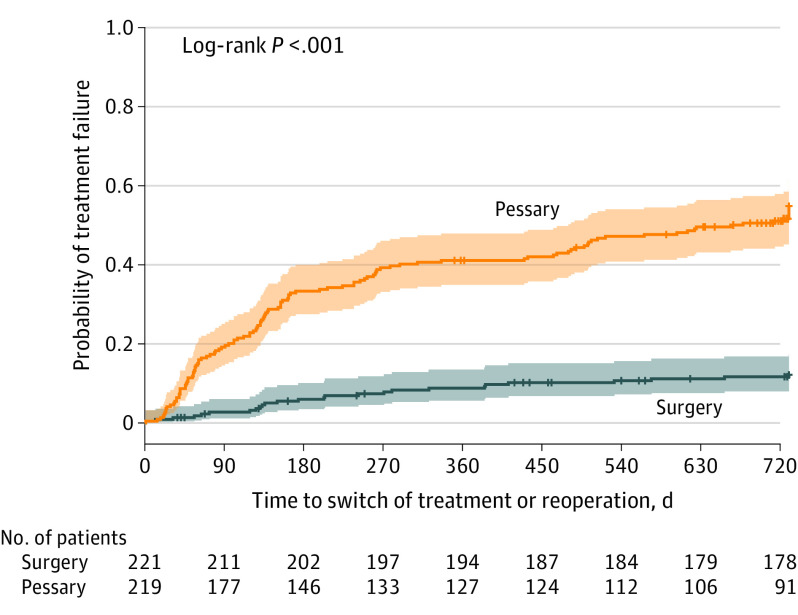

Time to discontinuation of initial treatment, reoperation, switching from pessary to surgery, or additional use of a pessary by women after surgery was analyzed by plotting a Kaplan-Meier curve and log-rank test.

For primary outcomes of patients in the as-randomized population, as well as the per-protocol population, who were lost to follow-up due to missing status, sensitivity analyses were specified using multiple imputation to assess robustness of results, especially if noninferiority would be shown (eAppendix in Supplement 3). SPSS version 27 (IBM) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) were used for statistical analyses. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory.

Results

Trial Population

Between March 2015 and November 2019, a total of 1605 women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse were asked to participate, of whom 440 gave written informed consent (Figure 1). Common reasons for not participating were the desire to choose treatment or failed pessary fitting. At baseline, the population consisted of 218 women in the pessary group and 222 women in the surgery group. Baseline analyses were performed for 221 women in the surgery group; 1 woman did not meet inclusion criteria and was excluded (Figure 1). Patient characteristics and questionnaire scores at baseline were similar (Table 1). Treatment details at initiation are shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 3. All 218 women randomized to receive pessary therapy initiated treatment. Of the 221 women randomized to the surgery group, 199 (90.0%) underwent surgery (Figure 1). No concomitant stress urinary incontinence surgery was performed. At 24 months, outcome data were available for 173 women (79.3%) in the pessary group and 162 women (73.3%) in the surgery group (Figure 1).

Primary Outcomes

Primary outcomes are shown in Table 2. With respect to the population as randomized, at 24 months, subjective improvement was reported by 132 of 173 (76.3%) women in the pessary group and by 132 of 162 (81.5%) women in the surgery group (risk difference, −6.1% [1-sided 95% CI, −12.7 to ∞]; P value for noninferiority = .16). Regarding the per-protocol population, the proportion of women in the pessary group who reported improvement was 52 of 74 (70.3%) compared with 125 of 150 (83.3%) women in the surgery group (risk difference, −13.1% [1-sided 95% CI, −23.0 to ∞]; P value for noninferiority = .69). Multiple imputation of missing outcomes did not alter these results (eTable 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 3).

Table 2. Population as Randomized and Per-Protocol Analysis of the Primary and Secondary Outcomes at 24 Months.

| Population as randomized | Per-protocol analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group, mean (SD)a | Difference (95% CI) | P value | Group, mean (SD)a | Difference (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Surgery (n=162) | Pessary (n=173) | Surgery (n=150)b | Pessary (n=74)b | |||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| PGI-I: improvement, No./total (%)c | 132/162 (81.5) | 132/173 (76.3) | −6.1% (−12.7 to ∞)d | .16e | 125/150 (83.3) | 52/74 (70.3) | −13.1% (−23.0 to ∞)d | .69e |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| PGI-S: improvement, No./total (%) | 134/157 (85.4) | 121/162 (74.7) | −10.7% (−19.3 to −2.0)d | .02f | 125/145 (86.2) | 50/70 (71.4) | −14.7% (−20.2 to −9.1)d | .005f |

| Change in PFDI-20 domain scoreg | (n=162) | (n=170) | (n=150) | (n=74) | ||||

| POPDI-6 | −23.3 (15.3) | −21.6 (22.1) | 1.7 (−2.4 to 5.8)h | .41 | −23.9 (15.2) | −19.9 (21.5) | 4.0 (−1.4 to 9.4)h | .15 |

| CRADI-8 | −3.9 (13.2) | −3.5 (13.4) | 0.4 (−2.4 to 3.3)h | .78 | −4.4 (13.1) | −2.5 (12.3) | 1.9 (−1.7 to 5.4)h | .30 |

| UDI-6 | −13.7 (19.4) | −10.7 (20.6) | 3.0 (−1.2 to 7.3)h | .16 | −13.9 (19.6) | −8.1 (18.8) | 5.8 (0.5 to 11.1)h | .03 |

| Irritative | NA | NA | NA | NA | −18.1 (29.0) | −12.7 (30.3) | 5.4 (−2.8 to 13.7)h | .19 |

| Stress | NA | NA | NA | NA | −3.3 (24.3) | 0.7 (22.4) | 4.0 (−2.6 to 10.7)h | .23 |

| Obstructive/discomfort | NA | NA | NA | NA | −20.4 (26.3) | −12.2 (23.6) | 8.2 (1.1 to 15.4)h | .02 |

| PFDI-20 total score | −41.0 (37.1) | −35.7 (44.4) | 5.3 (−3.4 to 14.0)h | .24 | −42.2 (37.6) | −30.4 (39.3) | 11.8 (0.5 to 22.3)h | .04 |

| Change in PFIQ-7 domain scorei | (n=160) | (n=169) | (n=148) | (n=72) | ||||

| UIQ-7 | −10.7 (17.4) | −10.2 (20.0) | 0.5 (−3.5 to 4.4)h | .81 | −10.8 (17.4) | −10.6 (18.6) | 0.2 (−4.9 to 5.3)h | .93 |

| CRAIQ-7 | −2.6 (12.9) | −3.2 (13.4) | −0.6 (−3.5 to 2.1)h | .65 | −2.5 (12.3) | −1.7 (10.4) | 0.8 (−2.3 to 3.9)h | .61 |

| POPIQ-7 | −12.3 (20.4) | −11.6 (19.8) | 0.7 (−3.6 to 5.0)h | .73 | −12.8 (20.7) | −11.4 (20.5) | 1.4 (−4.4 to 7.1)h | .63 |

| PFIQ-7 total score | −25.5 (40.5) | −24.8 (44.6) | 0.7 (−8.5 to 10.0)h | .88 | −26.0 (40.8) | −22.9 (38.6) | 3.1 (−8.2 to 14.0)h | .59 |

| Change in PISQ-IR sexually active, domain scorej | (n=69) | (n=78) | (n=65) | (n=30) | ||||

| Partner-related: indicates assessment of partner-related impacts | −0.04 (0.5) | 0.06 (0.5) | 0.10 (−0.04 to 0.26)h | .17 | −0.07 (0.5) | 0.15 (0.5) | 0.22 (0.03 to 0.4)h | .04 |

| Condition-specific: indicates assessment of comdition-specific impacts on activity | 0.12 (0.5) | 0.13 (0.5) | 0.01 (−0.15 to 0.17)h | .91 | 0.11 (0.5) | 0.11 (0.5) | 0.00 (−0.2 to 0.2)h | .98 |

| Global quality: indicates global quality rating of sexual quality | −0.12 (0.6) | −0.08 (0.5) | 0.04 (−0.13 to 0.22)h | .62 | −0.10 (0.6) | −0.10 (0.5) | 0.00 (−0.2 to 0.2)h | .98 |

| Condition impact: indicates condition-specific impact on sexual quality | 0.51 (0.7) | 0.31 (0.6) | −0.20 (−0.41 to 0.00)h | .05 | 0.48 (0.7) | 0.28 (0.5) | −0.20 (−0.4 to 0.04)h | .11 |

| Arousal-orgasm: indicates assessment of arousal, orgasm | 0.06 (0.5) | 0.09 (0.5) | 0.03 (−0.13 to 0.20)h | .68 | 0.05 (0.5) | 0.13 (0.5) | 0.08 (−0.1 to 0.3)h | .49 |

| Desire: indicates assessment of sexual desire | −0.06 (0.5) | −0.04 (0.6) | 0.02 (−0.15 to 0.19)h | .77 | −0.09 (0.5) | −0.02 (0.7) | 0.07 (−0.2 to 0.3)h | .63 |

| Summary score | 0.08 (0.3) | 0.08 (0.3) | 0.00 (−0.08 to 0.09)h | .95 | 0.07 (0.3) | 0.09 (0.2) | 0.02 (−0.09 to 0.1)h | .73 |

| Change in PISQ-IR not sexually active, domain scorek | (n=58) | (n=50) | (n=52) | (n=27) | ||||

| Partner-related: indicates partner-related reasons for not being active | −0.06 (1.0) | 0.23 (0.8) | 0.29 (−0.04 to 0.62)h | .10 | −0.04 (1.0) | 0.19 (0.8) | 0.23 (−0.1 to 0.6)h | .28 |

| Condition-specific: indicates condition-specific reasons for not being active | −0.12 (0.9) | 0.05 (1.1) | 0.17 (−0.21 to 0.56)h | .39 | −0.13 (1.0) | 0.05 (1.1) | 0.18 (−0.3 to 0.6)h | .48 |

| Global quality: indicates indicates global quality rating of sexual quality | −0.01 (0.6) | 0.17 (0.6) | 0.18 (−0.05 to 0.42)h | .14 | 0.02 (0.6) | 0.19 (0.7) | 0.17 (−0.1 to 0.5)h | .28 |

| Condition impact: indicates condition impact on sexual quality | −0.27 (0.7) | −0.09 (0.7) | 0.18 (−0.08 to 0.46)h | .18 | −0.29 (0.7) | −0.12 (0.9) | 0.17 (−0.2 to 0.6)h | .40 |

Abbreviations: CRADI-8, Colorectal-Anal Distress Inventory; CRAIQ-7, Colorectal-Anal Impact Questionnaire; NA, not applicable; PFDI-20, Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory; PFIQ-7, Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire; PGI-I, Patient Global Impression of Improvement; PGI-S, Patient Global Impression of Severity; PISQ-IR, Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA [International Urogynecological Association]-Revised; POPDI-6, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory; POPIQ-7, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire; UDI-6, Urinary distress Inventory, Short Form; UIQ-7, Urinary Impact Questionnaire.

Data are reported as mean (SD) unless otherwise stated. Ranges, anchors and minimally clinical important differences for the outcomes can be found in Table 1. Results of the observational cohort can be found in a published article.4

Explanation for the number of women in the per-protocol analysis: the surgery group excludes women who did not undergo surgery (22), had repeat surgery because of a recurrence of prolapse (4), had repeat surgery because of de novo urinary incontinence (1) and who additionally used a pessary because of a recurrent prolapse (4); the pessary group excludes women who later also had surgery (118), stopped pessary therapy (5) and those for whom it was unknown if they used a pessary (14).

Responses range from very much better to very much worse on a 7-point Likert scale.

Values indicate risk difference. Differences for PGI-I are reported with a 1-sided 95% CI.

Analysis used the Farrington-Manning test for noninferiority against the noninferiority margin of −10%.

Analysis used the χ2 test, risk difference 95% CI.

A negative change indicates improvement.

Values indicate mean difference with a 2-sided bootstrapped 95% CI for the difference of means.

A negative change indicates improvement.

An increase in the delta of change indicates less impact on female sexual functioning and better sexual functioning.

A decrease in the delta of change indicates less impact of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual inactivity.

Secondary Outcomes

With regard to the as-randomized population, significantly fewer women in the pessary group reported improvement on the PGI-S as compared with women in the surgery group (121/162 [74.7%] vs 134/157 [85.4%]; risk difference, −10.7% [95% CI, −19.3 to −2.0]; P = .02). The PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7 showed no significant differences between groups. Sexually active women in the surgery group (mean [SD] score, 0.31 [0.6]) reported significantly greater improvement on the PISQ-IR condition-impact domain (mean difference, −0.20 [95% CI, −0.41 to – 0.00]; P = .05) as compared with the pessary group (mean [SD] score, 0.51 [0.7]). Significant differences for sexually inactive women were not found between groups.

With respect to the per-protocol population, the proportion of women who reported improvement in symptom severity on the PGI-S was significantly lower in the pessary group (50/70 [71.4%]) as compared with the surgery group (125/145 [86.2%]), and the risk difference was −14.7% (95% CI, −20.2 to −9.1; P = .005). On the PFDI-20 questionnaire, women in the surgery group reported significantly more improvement in urinary symptoms (UDI-6) and total symptom bother as compared with pessary treatment. On the UDI-6 scale, the mean (SD) difference in the surgery group was −13.9 (19.6) compared with −8.1 (18.8) in the pessary group (mean difference between groups, 5.8 [95% CI, 0.5 – 11.1]; P = .03). Further analyses of the UDI subscales (stress urinary incontinence, irritative symptoms, and obstructive symptoms) showed that surgery significantly improved obstructive symptoms (mean difference, −20.4 [26.3]) vs pessary use (mean difference, −12.2 [23.6]) (mean between-group difference, 8.2 [95% CI, 1.1 to 15.4]; P = .02). With respect to the total symptom bother, measured with the PFDI-20, both groups demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements, although the mean difference for the surgery group was significantly greater than for the pessary group (−42.2 [37.6] vs −30.4 [39.3]; mean between-group difference, 11.8 [95% CI, 0.5 to 22.3]; P = .04). The PFIQ-7 showed no significant differences between groups. In contrast with the population as randomized, sexually active women in the pessary group reported a statistically significant greater improvement in the partner-related domain (mean difference in the pessary group, 0.15 [0.5] vs in the surgery group, −0.07 [0.5]; mean between-group difference, 0.22 [95% CI, 0.03 to 0.4]; P = .04). For sexually inactive women, no significant differences were observed.

The Kaplan-Meier curve showed women who received pessary therapy requested additional treatment or discontinued pessary therapy significantly sooner compared with women who underwent surgery and required further surgical intervention or additional pessary (P < .001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Time to Additional Treatment or Reoperation.

Colored shading indicates 95% CIs, and the vertical tick marks indicate patients who were censored. Pessary data indicate time to discontinuation of therapy or surgical intervention. Surgery data indicate time to repeat operation or start of additional use of pessary. The median failure observation time in the pessary group was 664 days (IQR, 131-730 days), and for the surgery group, it was beyond 730 days (right-sided censored IQR, 730-730 days).

Post Hoc Outcomes

eTable 4 in Supplement 3 shows changes in sexual status; between groups, no statistically significant differences were found. In the pessary group 6 of 54 (11.1%) women developed de novo dyspareunia, as compared with 6 of 39 (15.4%) in the surgery group (relative risk, 0.7 [95% CI, 0.2 to 2.0]; P = .54). After 24 months, dyspareunia resolved in 11 of 27 (40.7%) women in the pessary group and in 14 of 29 (48.3%) women in the surgery group (relative risk, 0.8 [95% CI, 0.5 to 1.5]; P = .57).

Adverse Events and Crossover

Table 3 summarizes adverse events in both groups. The most common adverse event in the pessary group was discomfort occurring in 42.7% of participants. At 24 months 123 (60.0%) women discontinued pessary use. A total of 118 (54.1%) women switched to surgery. The most common reason to switch was pessary expulsion, which involved 38 women (32.2%) of whom 10 had received at least 1 prior pessary insertion. Median time for pessary expulsion was 11.5 days (IQR, 4.5 to 24.5 days). Detailed information regarding pessary refitting attempts is available in eTable 5 in Supplement 3.

Table 3. Adverse Events and Additional Therapy.

| Group, No./total No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Surgery (n=221) |

Pessary (n=218) |

|

| Discontinued pessary use | NA | |

| 12 mo | 110/211 (52.1) | |

| 24 mo | 123/204 (60.0) | |

| Switched to surgerya | NA | 118/218 (54.1) |

| Reason for switching to surgery | ||

| Pessary expulsion | NA | 38/118 (32.2) |

| Inadequate symptom relief | NA | 20/118 (16.9) |

| Discomfort | NA | 19/118 (16.1) |

| Pain | NA | 15/118 (12.7) |

| Excessive discharge | NA | 12/118 (10.2) |

| Patient reports of incontinence | NA | 11/118 (9.3) |

| Dissatisfied about pessary management | NA | 3/118 (2.5) |

| Additional therapy after surgeryb | 12 (54) | NA |

| Reason for additional therapy after surgery | ||

| Recurrence of prolapse | 8/221 (3.6) | NA |

| Secondary bleeding | 2/221 (0.9) | NA |

| Prolapse of untreated compartment | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Pain after sacrospinous fixation | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| De novo urinary incontinence | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Adverse eventsc | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 20/221 (9.0) | 5/218 (2.3) |

| Uncomplicated urinary tract infection | 15/221 (6.8) | 4/218 (1.8) |

| Recurrent urinary tract infection (≥3/y) | 4/221 (1.8) | 1/218 (0.5) |

| Complicated by pyelonephritis | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Stress urinary incontinence | 7/221 (3.2) | 30/218 (13.8) |

| Urgency urinary incontinence | NA | 2/218 (0.9) |

| Discomfort | NA | 93/218 (42.7) |

| Pessary expulsion | NA | 45/218 (20.6) |

| Excessive discharge | NA | 42/218 (19.3) |

| Vaginal blood loss due to pessary therapy | NA | 25/218 (11.5) |

| Decubitus | NA | 14/218 (6.4) |

| Vaginal atrophy | 4/218 (1.8) | |

| Bladder retention | 11/221 (5.0) | NA |

| Blood loss ≥500 cc due to surgery | 3/221 (1.5) | NA |

| Blood transfusion needed | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Vaginal infection | 2/221 (1) | NA |

| Infected hematoma and multiple abdominal abscesses | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Hematoma | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Rectal lesion | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Sutures after sacrospinous fixation released spontaneously | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Post spinal headache | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Mixed incontinence | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Pyelonephritis | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

| Diedd | 1/221 (0.5) | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

From the 110 women who discontinued pessary therapy at 12 months, 105 switched to surgery and 5 did not undergo any kind of treatment. From the 123 women who discontinued pessary therapy at 24 months, 118 switched to surgery and 5 did not undergo any kind of treatment.

Repeat surgery was performed 9 times. One woman had repeat surgery twice. An additional pessary was used by 4 women (all because of a recurrent prolapse).

Adverse events in the pessary group occurred in 162 women.

Unrelated study event.

In the surgery group the most common complication was postoperative urinary tract infection, which occurred in 20 (9%) women. Three (1.5%) women had ≥500cc blood loss, one (0.5%) needed a blood transfusion. A bowel lesion, recognized during surgery, was successfully treated in 1 woman without further clinical implications. Twelve (5.4%) women in the surgery group underwent additional therapy (eg, pessary or repeat operation) after surgery. Of these 12 women, 8 underwent additional surgery (3.6%), and 4 used an additional pessary. One woman (0.5%) underwent 2 additional surgeries (first release of sacrospinous fixation sutures due to pain, followed by the Manchester-Fothergill procedure to correct recurrent pelvic organ prolapse). An additional pessary was used in 4 (1.8%) women because of recurrent prolapse, after the initial surgical repair failed.

Discussion

This trial showed that among patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, an initial strategy of pessary therapy, compared with surgery, did not meet criteria for noninferiority with regard to patient-reported improvement.

The crossover rate from pessary therapy to surgery was high (54.1%). Although reported subjective improvement was higher following surgery as compared with pessary in this trial (81.5% vs 76.3%), as well as in the observational cohort (83.3% vs 74.4%),4 the marked difference in percentage of women crossing over from pessary to surgery is interesting. The observational cohort showed a crossover rate of 23.6%, which is much lower than observed in this trial.4 Personal-level demographic and clinical characteristics have shown to play an important role in the decision to participate in clinical trials, and therefore, they are likely to differ between the trial and cohort population.34 Women without strong preconceived ideas on treatment choices may not only be more willing to be randomized, but they may also be more reluctant to continue allocated pessary therapy if subjective improvement would not meet their expectations. The knowledge that crossover was allowed may have lowered the threshold to do so. While this possible selection bias may limit the generalizability of this trial, it also reflects daily practice in women often relying on the advice of their general practitioner or gynecologist. For evidence-based counseling and shared decision-making, women should be informed about the high possibility of needing to switch pessary to surgical intervention.

In this trial, results of pessary therapy in the as-randomized population were substantially influenced by the effect of surgery. Conversely, per-protocol analyses of pessary users also presented a highly selected group. Crossover favors the study hypothesis of noninferiority, and both population as-randomized and per-protocol analyses should indicate similar results for the study to be reliable.35,36 In this trial, noninferiority of pessary therapy could not be demonstrated in either analysis.

In both this trial and observational cohort performed alongside the trial, pessary expulsion was the most common reason for switching to surgery.4 These findings suggest that despite a pessary fitting procedure, accurate prediction of which women can be successfully treated with a pessary is not optimal. New developments, such as estimating the appropriate pessary size based on 3-D perineal ultrasound genital hiatal dimensions, may reduce pessary expulsion.37 Furthermore, women should be counseled that pessary therapy might involve multiple pessary fittings, as suggested by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guideline.12

Regarding pelvic floor distress, the population as-randomized and per-protocol analyses indicated conflicting results. In contrast with existing literature, the population as-randomized analysis did not demonstrate differences in symptom bother between groups.4,8,9,26 However, in line with prior studies, the per-protocol analysis showed a favorable effect of surgery on micturition symptoms and the total PFDI-20 score.4,9 Since the per-protocol analysis and prior comparative studies showed this beneficial effect of surgery, it is likely that surgery indeed has a more positive effect on micturition symptoms as compared with pessary therapy. Looking at the subscales of the UDI-6, the surgery group reported significantly greater improvement in obstructive bladder symptoms, as compared with the pessary group. Obstructive bladder symptoms can be caused by anatomical obstruction of the outflow tract or functional problems including detrusor underactivity.38,39 A recent systematic review on the effect of pelvic organ prolapse surgery on bladder function, as measured with urodynamic investigation, showed both a reduction in outflow obstruction as well as regaining detrusor activity.40 Unfortunately, no studies on urodynamic changes after pessary therapy are available that could explain the difference between surgery and pessary that this study demonstrated.

With respect to sexual functioning, one study which also used the PISQ-IR, showed a superior effect of surgery on the condition-impact domain.31 This finding indicates that after surgery, women experienced less fear of prolapse-related symptoms and experienced higher satisfaction in their sex life. The per-protocol analysis did not confirm this. Instead, women in the pessary group reported superior outcomes on the partner-related domain. This implies that women experienced an increase in sexual desire, were more satisfied with the frequency of their sexual activity, and that pessary use was accepted by sexually active women. This finding is in line with a systematic review reporting that women who continue pessary use perceive some improvement in female sexual functioning.41 It is recommended for future studies to use the PISQ-IR as an outcome tool evaluating sexual functioning to collect more data.

Strengths

Strengths of this trial include the 24-month follow-up, the randomized design, the use of validated outcome measures, and the multicenter participation, all of which enhance generalizability of the findings.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, interpretation is limited by the loss to follow-up and the large number of participants who crossed over from pessary therapy to surgery. The failure to demonstrate noninferiority might be related to the number of participants included in the primary analyses. Due to the higher loss to follow-up rate than predicted (24% vs 10%), the analysis of the primary outcome at 24 months was conducted on data of 334 women instead of 396. This lower sample size in turn led to a wider confidence interval exceeding the noninferiority margin. If the target sample size had been achieved, noninferiority might have been demonstrated. Given the high crossover rate affecting the per-protocol population however, even the target sample size could have led to noninferiority being rejected.

Second, the analyses of the as-randomized and per-protocol populations showed conflicting results on the PFDI-20 and PISQ-IR questionnaires and therefore these data should be interpreted with caution.

Third, there was a substantial portion of nonresponders at 24-month follow-up for the PISQ-IR, as compared to other outcomes. This likely reflects the difficulty women experience in reporting about intimate sexual functioning.

Fourth, the surgical treatment in this study was limited to pelvic organ prolapse repair without concomitant surgery for stress urinary incontinence. Caution is warranted in generalizing these results to women who will have surgery to address both pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence.

Conclusions

Among patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse, an initial strategy of pessary therapy, compared with surgery, did not meet criteria for noninferiority with regard to patient-reported improvement at 24 months. Interpretation is limited by loss to follow up and the large amount of participant crossover from pessary therapy to surgery.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. Method for Multiple Imputation

eTable 1. Treatment Details at Initiation

eTable 2. Main Outcomes at 24 Months After Multiple Imputation in the Population as Randomized

eTable 3. Main Outcomes at 24 Months After Multiple Imputation in Per-Protocol Analysis

eTable 4. Change of Sexual Status Within 24 Months

eTable 5. Details About Women Who Had Additional Visit Due to a Change in Size/Shape of Pessary

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1027-1038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60462-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weintraub AY, Glinter H, Marcus-Braun N. Narrative review of the epidemiology, diagnosis and pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46(1):5-14. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2018.0581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Geelen JM, Dwyer PL. Where to for pelvic organ prolapse treatment after the FDA pronouncements? a systematic review of the recent literature. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(5):707-718. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Vaart LR, Vollebregt A, Milani AL, et al. Pessary or surgery for a symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: the PEOPLE study, a multicentre prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2022;129(5):820-829. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Albuquerque Coelho SC, de Castro EB, Juliato CR. Female pelvic organ prolapse using pessaries: systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(12):1797-1803. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-2991-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network . Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023-1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamers BH, Broekman BM, Milani AL. Pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse and health-related quality of life: a review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(6):637-644. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1390-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coolen AWM, Troost S, Mol BWJ, Roovers JPWR, Bongers MY. Primary treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: pessary use versus prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(1):99-107. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3372-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung VW, Wohlrab KJ, Madsen A, Raker C. Patient-reported goal attainment and comprehensive functioning outcomes after surgery compared with pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):659.e1-659.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamik MM, Rogers RG, Qualls CR, Komesu YM. Goal attainment after treatment in patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):488.e1-488.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for managing pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11(11):CD004010. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004010.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management. Published April 2, 2019. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123 [PubMed]

- 13.Evaluation Netherlands . Participant information for a comparative study between the cost effectiveness of pessary treatment and surgery in the treatment of prolapse with complaints: the People Study. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://zorgevaluatienederland.nl/evaluations/people

- 14.Utomo E, Korfage IJ, Wildhagen MF, Steensma AB, Bangma CH, Blok BF. Validation of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6) and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7) in a Dutch population. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34(1):24-31. doi: 10.1002/nau.22496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10-17. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cundiff GW, Amundsen CL, Bent AE, et al. The PESSRI study: symptom relief outcomes of a randomized crossover trial of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):405.e1-405.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Federatie Medisch Specialisten . Prolapse: guideline about the best care for patients with prolapse according to current standards. Utrecht, the Netherlands. Reviewed November 13, 2014. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/prolaps/prolaps_-_startpagina.html

- 18.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD004014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietz V, Schraffordt Koops SE, van der Vaart CH. Vaginal surgery for uterine descent; which options do we have? a review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(3):349-356. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0779-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srikrishna S, Robinson D, Cardozo L. Validation of the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) for urogenital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(5):523-528. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1069-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labrie J, Berghmans BL, Fischer K, et al. Surgery versus physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1124-1133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):98-101. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Utomo E, Blok BF, Steensma AB, Korfage IJ. Validation of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ-7) in a Dutch population. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(4):531-544. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2263-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Dongen H, van der Vaart H, Kluivers KB, Elzevier H, Roovers JP, Milani AL. Dutch translation and validation of the pelvic organ prolapse/incontinence sexual questionnaire-IUGA revised (PISQ-IR). Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30(1):107-114. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3718-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers RG, Rockwood TH, Constantine ML, et al. A new measure of sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders (PFD): the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR). Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(7):1091-1103. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2020-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barber MD, Walters MD, Cundiff GW; PESSRI Trial Group . Responsiveness of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI) and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ) in women undergoing vaginal surgery and pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1492-1498. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler J, Shahzeb Khan M, Lindenfeld J, et al. Minimally clinically important difference in health status scores in patients with HFrEF vs HFpEF. JACC Heart Fail. 2022;10(9):651-661. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2022.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):103-113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamińska A, Futyma K, Romanek-Piva K, Streit-Ciećkiewicz D, Rechberger T. Sexual function specific questionnaires as a useful tool in management of urogynecological patients—review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;234:126-130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Constantine ML, Pauls RN, Rogers RR, Rockwood TH. Validation of a single summary score for the Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire-IUGA revised (PISQ-IR). Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(12):1901-1907. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3373-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Vaart LR, Vollebregt A, Pruijssers B, et al. Female sexual functioning in women with a symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse; a multicenter prospective comparative study between pessary and surgery. J Sex Med. 2022;19(2):270-279. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LimeSurvey . Turn questions into answers. Accessed July, 28, 2022. https:www.limesurvey.org

- 33.US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration . Non-inferiority clinical trials to establish effectiveness guidance for industry. November 2016. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/78504/download

- 34.Williams CP, Senft Everson N, Shelburne N, Norton WE. Demographic and health behavior factors associated with clinical trial invitation and participation in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2127792. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tripepi G, Chesnaye NC, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, Jager KJ. Intention to treat and per-protocol analysis in clinical trials. Nephrology (Carlton). 2020;25(7):513-517. doi: 10.1111/nep.13709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2010;1(2):100-107. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.72352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manzini C, Withagen MIJ, van den Noort F, Grob ATM, van der Vaart CH. Transperineal ultrasound to estimate the appropriate ring pessary size for women with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(7):1981-1987. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-04975-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frigerio M, Manodoro S, Cola A, Palmieri S, Spelzini F, Milani R. Detrusor underactivity in pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(8):1111-1116. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3532-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wen L, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Changes in urethral mobility and configuration after prolapse repair. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53(1):124-128. doi: 10.1002/uog.19165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lourenço DB, Duarte-Santos HO, Partezani AD, et al. Urodynamic profile of voiding in patients with pelvic organ prolapse after surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2022. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05086-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wharton L, Athey R, Jha S. Do vaginal pessaries used to treat pelvic organ prolapse impact on sexual function? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(2):221-233. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-05059-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eAppendix. Method for Multiple Imputation

eTable 1. Treatment Details at Initiation

eTable 2. Main Outcomes at 24 Months After Multiple Imputation in the Population as Randomized

eTable 3. Main Outcomes at 24 Months After Multiple Imputation in Per-Protocol Analysis

eTable 4. Change of Sexual Status Within 24 Months

eTable 5. Details About Women Who Had Additional Visit Due to a Change in Size/Shape of Pessary

Data Sharing Statement