Key Points

Question

Is testing for coronary heart disease before kidney transplant associated with reduced early posttransplant death or myocardial infarction?

Findings

In this quasiexperimental, instrumental variable analysis cohort study of 79 334 adult, Medicare-insured, first-time kidney transplant recipients in the US from 2000 to 2014, testing within 12 months before kidney transplant was not associated with any change in death or myocardial infarction within 30 days after transplant (rate difference [reference, no testing], 1.9%; 95% CI, 0%-3.5%).

Meaning

The study results suggest that the current practice of testing for coronary heart disease before kidney transplant may not be associated with reduced adverse outcomes early after transplant.

Abstract

Importance

Testing for coronary heart disease (CHD) in asymptomatic kidney transplant candidates before transplant is widespread and endorsed by various professional societies, but its association with perioperative outcomes is unclear.

Objective

To estimate the association of pretransplant CHD testing with rates of death and myocardial infarction (MI).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included all adult, first-time kidney transplant recipients from January 2000 through December 2014 in the US Renal Data System with at least 1 year of Medicare enrollment before and after transplant. An instrumental variable (IV) analysis was used, with the program-level CHD testing rate in the year of the transplant as the IV. Analyses were stratified by study period, as the rate of CHD testing varied over time. A combination of US Renal Data System variables and Medicare claims was used to ascertain exposure, IV, covariates, and outcomes.

Exposures

Receipt of nonurgent invasive or noninvasive CHD testing during the 12 months preceding kidney transplant.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was a composite of death or acute MI within 30 days of after kidney transplant.

Results

The cohort comprised 79 334 adult, first-time kidney transplant recipients (30 147 women [38%]; 25 387 [21%] Black and 48 394 [61%] White individuals; mean [SD] age of 56 [14] years during 2012 to 2014). The primary outcome occurred in 4604 patients (244 [5.3%]; 120 [2.6%] death, 134 [2.9%] acute MI). During the most recent study period (2012-2014), the CHD testing rate was 56% in patients in the most test-intensive transplant programs (fifth IV quintile) and 24% in patients at the least test-intensive transplant program (first IV quintile, P < .001); this pattern was similar across other study periods. In the main IV analysis, compared with no testing, CHD testing was not associated with a change in the rate of primary outcome (rate difference, 1.9%; 95% CI, 0%-3.5%). The results were similar across study periods, except for 2000 to 2003, during which CHD testing was associated with a higher event rate (rate difference, 6.8%; 95% CI, 1.8%-12.0%).

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this cohort study suggest that pretransplant CHD testing was not associated with a reduction in early posttransplant death or acute MI. The study findings potentially challenge the ubiquity of CHD testing before kidney transplant and should be confirmed in interventional studies.

This instrumental variable analysis examines the association of pretransplant coronary heart disease testing with rates of death and myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) screening is a cornerstone of kidney transplant (KTx) evaluation and, to our knowledge, is recommended by every guideline to date. Testing, either noninvasive or invasive, in asymptomatic patients awaiting KTx is prevalent in practice. In studies of US Medicare beneficiaries, 40% of transplant recipients underwent CHD testing during the year before KTx. High rates of testing have persisted despite multiple large randomized clinical trials (RCTs) published during the 2000s that argued against CHD screening in asymptomatic patients. Proponents of screening contend that these trials did not include patients with advanced kidney disease and/or did not examine perioperative risk specifically. Furthermore, regulatory agencies have previously used posttransplant survival as the main metric to evaluate and accredit transplant programs, creating an incentive to avoid perioperative events that may be associated with early death.

Despite the ubiquity of the practice, to our knowledge, a positive association of CHD screening with KTx outcomes has not been demonstrated. The International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches–Chronic Kidney Disease (ISCHEMIA-CKD) trial found no benefit to an invasive strategy of coronary angiography followed by revascularization vs guideline-directed medical therapy in asymptomatic patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The results remained null in a prespecified subset of KTx candidates. These recent results further challenged the traditional practice, and some members of the nephrology and transplant community have suggested de-escalating CHD screening in asymptomatic KTx candidates. A particular motivation is how heavy testing requirements may pose as a barrier to KTx, especially for individuals already at risk for poor access; thus, de-escalation may allow for more equitable access to KTx.

Prior attempts to estimate the effect of CHD screening using observational data have been hampered by confounding by indication. Lentine et al found that patients who underwent CHD testing were more likely to have acute myocardial infarction (MI) after KTx. In that study, patients selected for CHD testing likely had a higher baseline risk of MI than patients selected for no testing, a classic case of confounding by indication. Dunn et al attempted to overcome confounding by indication by using a propensity-matched cohort design, and the study demonstrated no difference in 30-day post-KTx outcomes based on pre-KTx CHD testing. While promising, propensity matching can only reduce confounding introduced by observed covariates and cannot account for unobserved covariates; thus, it is an imperfect tool for establishing causality.

Ideally, the transplant community could conduct an RCT that compares pretransplant CHD screening with no screening in asymptomatic KTx candidates in the manner suggested by Kasiske et al. However, in practice, such a study has not materialized because of regulatory concerns, health systems factors, and genuine clinical uncertainty and equipoise. The Canadian-Australasian Randomized Trial of Screening Kidney Transplant Candidates for Coronary Artery Disease (CARSK) study is an ongoing RCT to test whether surveillance CHD screening reduces cardiovascular events in already waitlisted KTx candidates. Only surveillance CHD screening was examined, as transplant programs were reluctant to participant if they had to forego CHD screening altogether. Most of the patients will be recruited outside the US; thus, future uptake in the US is unclear.

As a complement to CARSK, whose results will not be available for several years, we conducted an instrumental variable (IV) analysis in a real-life, US cohort. An IV analysis attempts to draw causal inference from observational data. The key is the selection of an IV, an exposure that is associated with an outcome only through the mediation of the actual exposure of interest. Example studies used distance from the nearest facility with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) capacity and facility-level PCI rate as IVs for PCI, the exposure of interest. In one analysis, IV analysis yielded less biased estimates (compared with criterion-standard estimates from RCTs) than multivariate adjustments and propensity score matching. Modeling on the second study, we selected the facility/program-level CHD testing rate as the IV for pretransplant CHD testing. Because transplant programs display variability in CHD testing behavior that is not explained by patient characteristics and patients generally select transplant programs based on geographic proximity, insurance network, and/or waitlist/transplant outcomes that are not directly associated with CHD testing behavior, we assumed that the program-level CHD testing rate would only be associated with a patient’s clinical outcome as mediated through that patient’s receipt of CHD testing. The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that pretransplant CHD testing was associated with a lower rate of cardiac events after KTx.

Methods

Patient Cohort

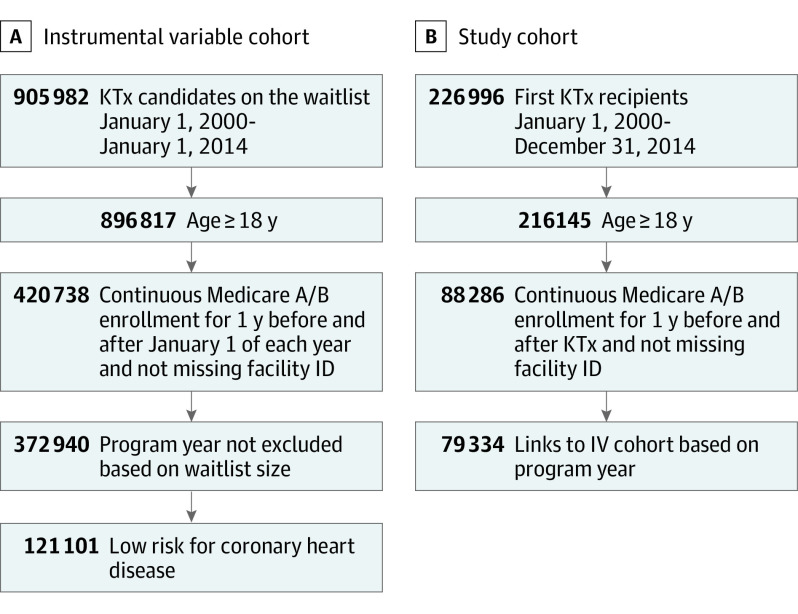

We created 2 cohorts in the study (Figure 1). For the study cohort, we included all adult, first-time KTx recipients from 2000 through 2014 in the US Renal Data System with at least 1 year of uninterrupted Medicare Parts A and B before and after transplant (2 years total). To construct IVs, we created an IV cohort, which was defined as adult, low-risk KTx candidates on each transplant program’s waitlist on January 1 of each year. Stanford University's institutional review board approved this research, and the need for informed consent was waived as the study was conducted on an identified retrospective registry.

Figure 1. Assembly of Instrument Variable (IV) and Study Cohorts.

KTx indicates kidney transplant.

Exposure

We used Medicare claims data to ascertain the primary exposure, which was whether a KTx recipient underwent nonurgent CHD testing (invasive or noninvasive) during the 12 months before KTx. We identified these tests based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and Current Procedural Terminology codes with diagnosis-related group codes (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). Because claims codes are not accompanied by an indication for testing, we approximated the urgency of testing by the place of service. We defined an urgent CHD test as follows (and included only nonurgent tests): (1) any noninvasive CHD test done on the day of or after an emergency department (ED) visit, or done during the dates covered by a hospitalization; (2) any coronary angiogram done on the day of or after an ED visit; and (3) any coronary angiogram done during a hospitalization with MI listed as a diagnosis (see eAppendix 1 in the Supplement for the relevant diagnosis-related group codes). These definitions concord with prior studies.

IV Definition

This study’s IV was the program-level CHD testing rate, which was defined as the proportion of adult, low-risk KTx candidates on each transplant program’s waitlist on January 1 of each year (denominator) who underwent nonurgent CHD testing during that calendar year (numerator). The IV ranged from 0 (no low-risk candidate tested) to 1 (every low-risk candidate tested). Low-risk was defined as the absence of major risk factors, including being older than 60 years, diabetes, and known CHD. We defined IV in low-risk patients on statistical grounds to maximize interprogram variability in the CHD testing rate. One may reasonably expect that most programs would opt to test high-risk candidates; therefore, interprogram variability would be lower if we defined IV in high-risk candidates. As a sensitivity analysis, we performed the analysis using an alternative definition of IV as the proportion of adult, high-risk KTx candidates (ie, having any of the 3 major risk factors listed previously) on the waitlist who underwent nonurgent CHD testing.

To assess the spread of IV in the exposure, we plotted the program-level CHD testing (y-axis) against the waitlist volume (x-axis) for each program-year. To maximize the ability of the IV to detect a meaningful difference in outcomes, we needed a cluster of program-years with a good spread of IV that was independent of waitlist volume, a potential residual confounder. Based on this analysis, we excluded the extremes of program size (waitlist volume <30 [25th percentile] or >868 [99th percentile]). eAppendix 2 in the Supplement further details the rationale for exclusions with graphical illustrations.

Outcome

The primary outcome was a composite of death or acute MI within 30 days of after KTx, which was adjusted for age, sex, race, education, dialysis vintage, history of CHD, diabetes, and transplant type (living vs deceased). Death was obtained from the patient file. Acute MI was defined from Medicare Part A claims (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement).

Covariates

We obtained covariates that were specific to the transplant programs and individual patients in the study cohort (ie, KTx recipients). For transplant programs, we obtained covariates for every calendar year in the study: annual transplant volume and annual waitlist size (defined as the transplant program’s waitlist size on January 1 of that calendar year). For patients, we obtained the following covariates: demographic characteristics (from the patient file), highest educational attainment (from the transplant candidate registration file), transplant type (living vs deceased donor, from the transplant file), dialysis vintage (from the treatment history file), and claims-based comorbidities based on 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient claims that were separated by at least a day within a 1-year lookback window as described by Elixhauser et al.

Statistical Analysis

We examined the balance of covariates across quintiles of IV using the standardized mean difference (SMD), for which we calculated the SMD among each pair of quintiles (ie, quintile 1 vs quintile 2, quintile 1 vs quintile 3, and so on) and kept the largest absolute difference. An SMD less than 0.2 indicated a small difference in covariates across quintiles, which we believed to be negligible given the multiple testing resulting from 5 comparator groups. We stratified analyses by era (2000-2003, 2004-2007, 2008-2011, 2012-2014), as there was a noticeable shift in the IV (ie, prevalence of CHD testing) during the latter eras (eAppendix 3 in the Supplement). We performed a 2-stage residual inclusion IV model with the primary output of rate difference or difference in the occurrence of the primary outcome (death or acute MI within 30 days of transplant) that was associated with pretransplant CHD testing. We used 1000 bootstrap samples of the IV model within each stratum to calculate the 95% CI around the point estimate. We summarized the results across strata by weighted average using the inverse variance method. We conducted the analysis using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Statistical significance was set at P < .05 unless otherwise specified.

Results

Cohorts and Baseline Characteristics

To create the IV, we included 121 101 waitlist candidates in the IV cohort (Figure 1A). To examine outcomes, we created a study cohort of 79 334 adult, first-time KTx recipients with 1 year of Medicare Parts A and B coverage before and after KTx from 2000 to 2014 (Figure 1B). The proportion of low-risk, waitlisted patients who underwent elective CHD (IV cohort: eligible patients on the waitlist on January 1 of each year) was 0.13; the number ranged from 0 to 0.44 across programs. The Table displays the baseline characteristics at the program-year and patient (study cohort) within each quintile of IV (main exposure) as stratified by era. As expected, the proportion of study patients who underwent CHD testing during the 12 months before KTx increased monotonically across increasing IV quintiles. The SMD analysis indicated good balancing of patient-level characteristics (SMD <0.2). Some residual imbalances in the transplant program volumes remained (SMD >0.2), although the trends were not monotonic (ie, the highest transplant volumes were in the middle-quintile IV programs, not in the highest or lower-quintile IV programs). Of the 34 688 KTx recipients who underwent CHD testing during the year before KTx, the median time between CHD testing and KTx was 188 days (IQR 98-275 days). A total of 8125 (23%) underwent testing on or before joining the waitlist, whereas 26 563 (77%) underwent testing after joining the waitlist.

Table. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort of First-time Kidney Transplant Recipients by Quintile of the Instrumental Variable as Stratified by Eraa.

| Characteristic | Quintile (range) of program-predicted CHD testing rate in kidney transplant candidates (instrument), % | Max SMDb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: 2000-2003 | 1 (0-6.6) | 2 (6.6-8.4) | 3 (8.4-10.0) | 4 (10.0-13.7) | 5 (13.7-44.4) | NA |

| Transplant program-years, No. | 107 | 82 | 99 | 114 | 137 | NA |

| Annual transplant volume, median (IQR) | 66 (33-108) | 91 (67-126) | 84 (54-129) | 79 (50-136) | 63 (43-99) | 0.36 |

| Annual waitlist volume, median (IQR) | 198 (129-411) | 310 (233-403) | 231 (157-481) | 317 (211-446) | 216 (141-372) | 0.35 |

| Patients, No. | 3063 | 3117 | 3457 | 3596 | 3684 | NA |

| CHD testing, No. (%) | 766 (25) | 873 (28) | 1072 (31) | 1474 (41) | 1768 (48) | 0.06 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 50 (39-60) | 50 (39-60) | 50 (39-61) | 51 (40-62) | 53 (41-64) | 0.003 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 1225 (40) | 1278 (41) | 1417 (41) | 1402 (39) | 1474 (40) | NA |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 1838 (60) | 1839 (59) | 2040 (59) | 2194 (61) | 2210 (60) | 0.02 |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||||

| Black | 1254 (41) | 1153 (37) | 1037 (30) | 1115 (31) | 1105 (30) | 0.22 |

| White | 1654 (54) | 1777 (57) | 2005 (58) | 2230 (62) | 2284 (62) | 0.01 |

| Otherc | 155 (5) | 187 (6) | 415 (11) | 251 (7) | 295 (7) | 0.14 |

| Education, No. % | ||||||

| Some college and greater | 888 (29) | 779 (25) | 899 (26) | 899 (25) | 1032 (28) | 0.10 |

| High school and less | 1409 (46) | 1496 (48) | 1487 (43) | 1546 (43) | 158 (43) | 0.09 |

| Dialysis vintage, median (IQR), y | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-5) | 0.09 |

| CHD, No. (%) | 459 (15) | 499 (16) | 588 (17) | 683 (19) | 737 (20) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 1195 (39) | 1278 (41) | 1314 (38) | 1474 (41) | 1547 (42) | 0.05 |

| Transplant type, % living donor | 674 (22) | 561 (18) | 761 (22) | 755 (21) | 847 (23) | 0.09 |

| Era: 2004-2007 | 1 (0-7.8) | 2 (7.8-10.8 | 3 (10.8-13.1) | 4 (13.1-15.2) | 5 (15.2-31.5) | NA |

| No. of transplant program-years | 171 | 133 | 124 | 116 | 178 | NA |

| Annual transplant volume, median (IQR) | 60 (37-98) | 71 (38-108) | 75 (44-136) | 81 (45-178) | 75 (48-107) | 0.31 |

| Annual waitlist volume, median (IQR) | 182 (126-296) | 258 (156-450) | 320 (151-546) | 350 (227-508) | 252 (163-359) | 0.44 |

| Patients, no. | 4532 | 4159 | 4147 | 4461 | 5328 | NA |

| CHD testing, No. % | 1224 (27) | 1414 (34) | 1741 (42) | 2052 (46) | 2984 (56) | 0.09 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 53 (41-63) | 53 (41-63) | 54 (43-64) | 54 (43-65) | 55 (43-65) | 0.03 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 1767 (39) | 1622 (39) | 1617 (39) | 1740 (39) | 1971 (37) | NA |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 2765 (61) | 2537 (61) | 2530 (61) | 2721 (61) | 3357 (63) | 0.01 |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||||

| Black | 1496 (33) | 1248 (30) | 1161 (28) | 1561 (35) | 1705 (32) | 0.12 |

| White | 2765 (61) | 2412 (58) | 2654 (64) | 2543 (57) | 3250 (61) | 0.13 |

| Otherc | 271 (6) | 499 (12) | 332 (9) | 357 (8) | 373 (7) | 0.14 |

| Education, No. (%) | ||||||

| Some college and greater | 1360 (30) | 1248 (30) | 1244 (30) | 1472 (33) | 1545 (29) | 0.08 |

| High school and less | 2311 (51) | 2038 (49) | 2074 (51) | 2052 (46) | 2504 (47) | 0.10 |

| Dialysis vintage, median (IQR), y | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-5) | 0.17 |

| CHD, No. (%) | 906 (20) | 873 (21) | 954 (23) | 1115 (25) | 1492 (28) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 2039 (45) | 1872 (45) | 1908 (46) | 1918 (43) | 2504 (47) | 0.06 |

| Transplant type, % living donor | 725 (16) | 790 (19) | 954 (23) | 937 (21) | 1066 (20) | 0.09 |

| Era: 2008-2011 | 1 (0-9.2) | 2 (9.2-12.2) | 3 (12.2-15.3) | 4 (15.3-17.8) | 5 (17.8-33.3) | NA |

| Transplant program-years, No. | 173 | 135 | 136 | 138 | 167 | NA |

| Annual transplant volume, median (IQR) | 50 (33-104) | 70 (44-99) | 77 (48-113) | 71 (37-142) | 70 (41-126) | 0.01 |

| Annual waitlist volume, median (IQR) | 223 (147-438) | 280 (189-566) | 363 (207-623) | 316 (186-576) | 317 (235-560) | 0.10 |

| Patients, No. | 4596 | 3992 | 4581 | 4562 | 5211 | NA |

| CHD testing, No. (%) | 1195 (26) | 1357 (34) | 2061 (45) | 2144 (47) | 3074 (59) | 0.04 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 55 (44-65) | 55 (43-65) | 54 (44-64) | 56 (45-66) | 57 (46-66) | 0.05 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 1838 (40) | 1517 (38) | 1787 (39) | 1734 (38) | 1980 (38) | |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 2759 (60) | 2475 (62) | 2794 (61) | 2828 (62) | 3231 (62) | 0.01 |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||||

| Black | 1379 (30) | 1597 (40) | 1512 (33) | 1323 (29) | 1668 (32) | 0.22 |

| White | 2941 (63) | 2116 (53) | 2749 (60) | 2828 (62) | 3074 (59) | 0.20 |

| Otherc | 276 (6) | 279 (7) | 320 (7) | 411 (9) | 469 (9) | 0.01 |

| Education, No. (%) | ||||||

| Some college and greater | 1655 (36) | 1557 (39) | 1604 (35) | 1642 (36) | 1876 (36) | 0.09 |

| High school and less | 2160 (47) | 2076 (52) | 2382 (52) | 2781 (50) | 2345 (45) | 0.45 |

| Dialysis vintage, median (IQR), y | 4 (2-5) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-6) | 0.11 |

| CHD, No. (%) | 919 (20) | 918 (23) | 1145 (25) | 1232 (27) | 1459 (28) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 2252 (49) | 1916 (48) | 2291 (50) | 2235 (49) | 2658 (51) | 0.02 |

| Transplant type, % living donor | 920 (20) | 758 (19) | 825 (18) | 867 (19) | 938 (18) | 0.05 |

| Era: 2012-2014 | 1 (0-10.7) | 2 (10.7-13.9) | 3 (13.9-16.9) | 4 (16.9-21.6) | 5 (21.6-46.7) | NA |

| Transplant program-years, No. | 136 | 117 | 91 | 87 | 115 | NA |

| Annual transplant volume, median (IQR) | 53 (35-86) | 64 (35-109) | 90 (42-165) | 74 (35-185) | 66 (41-113) | 0.41 |

| Annual waitlist volume, median (IQR) | 301 (186-436) | 313 (188-588) | 475 (224-828) | 395 (235-885) | 399 (277-582) | 0.35 |

| Patients, No. | 4857 | 4527 | 4639 | 4537 | 4354 | NA |

| CHD testing % | 24 | 31 | 39 | 46 | 56 | 0.14 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 57 (46-66) | 56 (45-66) | 56 (45-66) | 57 (45-66) | 56 (45-66) | 0.04 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 1894 (39) | 1766 (39) | 1809 (39) | 1679 (37) | 1611 (37) | |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 2963 (61) | 2761 (61) | 2830 (61) | 2858 (63) | 2743 (63) | 0.01 |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||||

| Black | 1457 (30) | 1359 (30) | 1298 (28) | 1497 (33) | 1567 (36) | 0.04 |

| White | 3108 (64) | 2897 (64) | 2830 (61) | 2677 (59) | 2525 (58) | 0.14 |

| Otherc | 292 (5) | 271 (6) | 511 (10) | 363 (8) | 262 (7) | 0.14 |

| Education, No. (%) | ||||||

| Some college and greater | 2040 (42) | 1947 (43) | 2041 (44) | 2087 (46) | 1872 (43) | 0.05 |

| High school and less | 2380 (49) | 2309 (51) | 2227 (48) | 2132 (47) | 2177 (50) | 0.07 |

| Dialysis vintage, median (IQR), y | 4 (3-6) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-6) | 0.03 |

| CHD, No. (%) | 923 (19) | 951 (21) | 1067 (23) | 1089 (24) | 1045 (24) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 2429 (50) | 2263 (50) | 2180 (47) | 2132 (47) | 2090 (48) | 0.07 |

| Transplant type, % living donor | 777 (16) | 724 (16) | 742 (16) | 817 (18) | 697 (16) | 0.06 |

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; max, maximum; NA, not applicable; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Each observation represents a program-year (program characteristics) or patient. Continuous variables are presented as median (IQR) and categorical variables are presented as number (percentages).

Max (SMD) refers to the maximum standardized difference of all combinations of pairs (of quintiles).

Other includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Pacifier Islander, or other.

Analysis

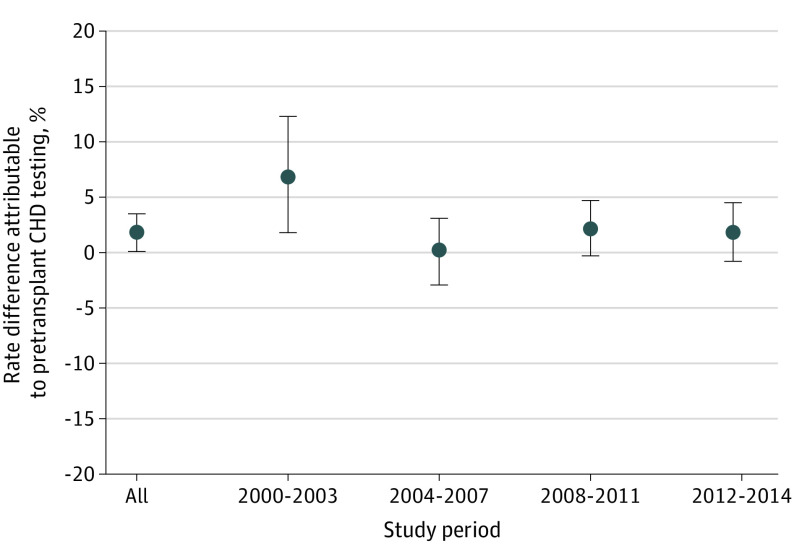

A total of 4604 patients (5.3%) in the study cohort reached the primary outcome of death or acute MI within 30 days of after KTx (120 [2.6%] death, 134 [2.9%] acute MI). During the study period, the 30-day event rate decreased from 6.6% from 2000 to 2003 to 4.4% from 2012 to 2014. The main analysis showed that, compared with a reference of no testing, pretransplant CHD testing was not associated with a change in the rate of primary outcome at 30 days (rate difference, 1.9%; 95% CI, 0%-3.5%) (Figure 2). The effect sizes across the eras were constant except for 2000 to 2003, when a slight increase in event rate (greater than the basal rate of 6.6%) associated with CHD testing was observed (rate difference, 6.8%; 95% CI, 1.8%-12.3%). A sensitivity analysis that excluded covariates from the model (eAppendix 4 in the Supplement) and used the alternative definition of IV (program-level CHD testing rate in high-risk candidates; eAppendix 5 in the Supplement) showed largely the same results.

Figure 2. Association of Pretransplant Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) Testing With Death or Acute Myocardial Infarction Rate Within 30 Days Posttransplant.

Discussion

This IV analysis using registry and claims data was unable to show that CHD screening before KTx protected against cardiac events (death or nonfatal MI) within 30 days after KTx. We selected our outcome to be an early perioperative event, as the ISCHEMIA-CKD trial demonstrated that up-front angiography and revascularization do not appear to be associated with lower rates of major adverse cardiac events in stable patients with advanced CKD. Whether routine testing and, when abnormal, revascularization are associated with reduced rates of perioperative cardiovascular events or death in KTx candidates remains an open question.

During the study period, around 5% of the study cohort had a cardiac event within 30 days after KTx. Pretransplant CHD testing was associated with a statistically nonsignificant change in the probability of that event, with a directionality pointing toward possible harm (up to 3.5% increase in absolute risk of event). This finding was consistent with prior observational studies that used propensity scores, including a recent study derived from a national prospective cohort from the UK. Screening was associated with an increased event rate during the earliest era from 2000 to 2003 by a 6.8% absolute increase (95% CI, 1.8%-12.3%), which was greater than the basal 30-day event probability of 6.6%. This unexpected finding for substantial harm may be associated with residual confounding due to an imbalance in unobserved transplant program characteristics (discussed further in Limitations). Alternatively, 2003 saw the approval of the first drug-eluting stent in the US; previously, the standard was bare metal stents. That screening may have been associated with elective revascularization and stenting with bare metal stents, which were associated with increased perioperative risk, and that this was then associated with a signal for harm during the earlier eras remains a possibility. This highlights the point that even what appears to be innocuous screening may be associated with harm when used broadly in asymptomatic patients.

We included all adult, Medicare-insured, first-time KTx recipients in the study cohort in an attempt to maximize generalizability. Therefore, the study results ought to apply to KTx recipients who received testing before and after joining the waitlist. We created our IV in low-risk waitlisted candidates to maximize interprogram variability in CHD testing rates. The statistical justification, as well as the fact that a sensitivity analysis defining IV in high-risk waitlist candidates yielded essentially the same results, suggests that this study is applicable to screening in high-risk and low-risk KTx candidates.

The finding suggests that CHD screening may not protect against early posttransplant events is plausible. The Coronary Artery Revascularization Prophylaxis (CARP) study, undertaken in patients undergoing elective vascular operation, has shown that elective preoperative coronary artery revascularization in patients with stable cardiac symptoms does not significantly alter the postoperative outcome. The study population of CARP is similar to KTx candidates, in that they are enriched in CHD risk factors, including age (mean age of 66 years), smoking (approximately 45%), and peripheral vascular disease (study inclusion criteria), and one-third had 3-vessel CHD. The failure of elective preoperative revascularization to reduce risk in the high-risk CARP cohort suggests that screening in KTx candidates, presumably for the purpose of identifying patients for preoperative revascularization, could be similarly ineffective at reducing cardiac events.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the study include the use of IV to attempt to draw causal inference between CHD screening and posttransplant outcomes and the use of validated approaches to capture comorbidity and track posttransplant events from administrative data. The main limitation is residual confounding that may not be fully resolved by the quasiexperimental IV study design. Two sources of hidden biases exist that may be associated with the validity of the exclusion restriction assumption. First, facility/program characteristics are potential residual confounders. Transplant volume differs in transplant programs with different rates of CHD testing, and volume is usually inversely associated with outcome (ie, higher-volume programs generally perform better). Therefore, transplant volume may introduce a collider bias, for which it is associated with the IV (rate of CHD testing) and the outcome. However, the association between transplant volume and CHD testing rates in the present study is not monotonic: programs with intermediate levels of CHD testing have the highest volume. Therefore, it is unclear if collider bias can fully invalidate our IV. Second, KTx programs may have different thresholds for risk acceptance overall; more risk-tolerant programs may elect for higher-intensity CHD testing protocol to safeguard against adverse outcomes. This is a limitation that can only be overcome by interventional designs. Also, our ascertainment of CHD testing is based on Medicare A claims; testing submitted to private insurers or financed via the Organ Acquisition Cost Center would not be included. Therefore, our IV may not be accurately classifying the relative intensity of CHD testing at each program. Finally, as a claims-based study, details on CHD testing and comorbidities are less granular. For instance, we are unable to identify the actual indication for CHD testing. Nonetheless, use of a claims-based algorithm to exclude likely urgent testing is consistent with the literature.

Conclusions

This quasiexperimental cohort study using program-level CHD testing as an IV was unable to demonstrate that pretransplant CHD testing was associated with reduced early death and MI within 30 days of KTx. There is even a potential signal that CHD testing was associated with harm during the earlier study eras. Ideally, a US-based RCT can verify or disprove these results. However, in places where such a study is not possible, pragmatic studies in countries with less perceived regulatory pressure and a more integrated health delivery system (eg, CARSK) offer the best hope. Studies such as ours, in an US population using quasiexperimental methods, potentially help to complement these interventional studies in other countries and may pave the way to deescalating CHD testing before KTx.

eAppendix 1. ICD, CPT and DRG codes used in this study

eAppendix 2. How we excluded the extremes of program size from IV cohort

eAppendix 3. Baseline characteristics by quintile of instrumental variable, unstratified by era

eAppendix 4. Effects of pretransplant CHD testing on death or acute myocardial infarction rate within 30 days posttransplant, with (main analysis) and without covariates

eAppendix 5. Effects of pretransplant CHD testing on death or acute myocardial infarction rate within 30 days posttransplant, using testing intensity in high-risk waitlisted candidates as the instrumental variable

References

- 1.Lentine KL, Costa SP, Weir MR, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease . Cardiac disease evaluation and management among kidney and liver transplantation candidates: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(5):434-480. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Brennan DC, et al. Cardiac evaluation before kidney transplantation: a practice patterns analysis in Medicare-insured dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(4):1115-1124. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05351107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shpigel AA, Saeed MJ, Novak E, Alhamad T, Rich MW, Brown DL. Center-related variation in cardiac stress testing in the 18 months prior to renal transplantation. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1135-1136. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng XS, Liu S, Han J, et al. Trends in coronary artery disease screening before kidney transplantation. Kidney360. 2021;3(3):516-523. doi: 10.34067/KID.0005282021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE, et al. Coronary-artery revascularization before elective major vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2795-2804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. ; COURAGE Trial Research Group . Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(15):1503-1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young LH, Wackers FJ, Chyun DA, et al. ; DIAD Investigators . Cardiac outcomes after screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: the DIAD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(15):1547-1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bangalore S, Maron DJ, O’Brien SM, et al. ; ISCHEMIA-CKD Research Group . Management of coronary disease in patients with advanced kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):1608-1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzog CA, Simegn MA, Xu Y, et al. Kidney transplant list status and outcomes in the ISCHEMIA-CKD trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(4):348-361. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharif A. The argument for abolishing cardiac screening of asymptomatic kidney transplant candidates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(6):946-954. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monson RS, Kemerley P, Walczak D, Benedetti E, Oberholzer J, Danielson KK. Disparities in completion rates of the medical prerenal transplant evaluation by race or ethnicity and gender. Transplantation. 2015;99(1):236-242. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weng FL, Joffe MM, Feldman HI, Mange KC. Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(4):734-745. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn T, Saeed MJ, Shpigel A, et al. The association of preoperative cardiac stress testing with 30-day death and myocardial infarction among patients undergoing kidney transplantation. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baiocchi M, Cheng J, Small DS. Instrumental variable methods for causal inference. Stat Med. 2014;33(13):2297-2340. doi: 10.1002/sim.6128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Camarena A; COST Investigators . Design considerations and feasibility for a clinical trial to examine coronary screening before kidney transplantation (COST). Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(6):908-916. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng XS, Mathew RO, Parasuraman R, et al. Coronary artery disease screening of asymptomatic kidney transplant candidates: a web-based survey of practice patterns in the United States. Kidney Med. 2020;2(4):505-507. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ying T, Gill J, Webster A, et al. Canadian-Australasian randomised trial of screening kidney transplant candidates for coronary artery disease—a trial protocol for the CARSK study. Am Heart J. 2019;214:175-183. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClellan M, McNeil BJ, Newhouse JP. Does more intensive treatment of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly reduce mortality? analysis using instrumental variables. JAMA. 1994;272(11):859-866. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520110039026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stukel TA, Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Alter DA, Gottlieb DJ, Vermeulen MJ. Analysis of observational studies in the presence of treatment selection bias: effects of invasive cardiac management on AMI survival using propensity score and instrumental variable methods. JAMA. 2007;297(3):278-285. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Renal Data System . 2018 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang D, Dalton JE. A unified approach to measuring the effect size between two groups using SAS. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings12/335-2012.pdf

- 23.Terza JV. Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: a practitioners guide to Stata implementation. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://www.stata.com/meeting/chicago16/slides/chicago16_terza.pdf

- 24.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Inverse Variance Method. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nimmo A, Forsyth J, Oniscu G, et al. A propensity score matched analysis indicates screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease does not predict cardiac events in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2021;99(2):431-442. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garabedian LF, Chu P, Toh S, Zaslavsky AM, Soumerai SB. Potential bias of instrumental variable analyses for observational comparative effectiveness research. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(2):131-138. doi: 10.7326/M13-1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abecassis M. Organ acquisition cost centers part I: Medicare regulations—truth or consequence. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(12):2830-2835. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. ICD, CPT and DRG codes used in this study

eAppendix 2. How we excluded the extremes of program size from IV cohort

eAppendix 3. Baseline characteristics by quintile of instrumental variable, unstratified by era

eAppendix 4. Effects of pretransplant CHD testing on death or acute myocardial infarction rate within 30 days posttransplant, with (main analysis) and without covariates

eAppendix 5. Effects of pretransplant CHD testing on death or acute myocardial infarction rate within 30 days posttransplant, using testing intensity in high-risk waitlisted candidates as the instrumental variable