Key Points

Question

When medical devices that had been cleared under the FDA’s 510(k) pathway are subject to Class I recalls, how often did the predicates for these devices also have a history of recalls?

Findings

In this cross-sectional analysis of 156 cases of 510(k)–authorized devices with Class I recalls from 2017 through 2021, 44.1% used predicates with Class I recalls. In addition, 48.1% of these devices were subsequently used as predicates to authorize descendant devices later subject to Class I recalls. The risk of a Class I recall was 6.40 times higher for descendants that used predicates with Class I recalls than for devices using Class I recall–free predicates.

Meaning

Stronger safeguards are needed to prevent problematic predicate selection and ensure patient safety.

Abstract

Importance

In the US, nearly all medical devices progress to market under the 510(k) pathway, which uses previously authorized devices (predicates) to support new authorizations. Current regulations permit manufacturers to use devices subject to a Class I recall—the FDA’s most serious designation indicating a high probability of adverse health consequences or death—as predicates for new devices. The consequences for patient safety are not known.

Objective

To determine the risk of a future Class I recall associated with using a recalled device as a predicate device in the 510(k) pathway.

Design and Setting

In this cross-sectional study, all 510(k) devices subject to Class I recalls from January 2017 through December 2021 (index devices) were identified from the FDA’s annual recall listings. Information about predicate devices was extracted from the Devices@FDA database. Devices authorized using index devices as predicates (descendants) were identified using a regulatory intelligence platform. A matched cohort of predicates was constructed to assess the future recall risk from using a predicate device with a Class I recall.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Devices were characterized by their regulatory history and recall history. Risk ratios (RRs) were calculated to compare the risk of future Class I recalls between devices descended from predicates with matched controls.

Results

Of 156 index devices subject to Class I recall from 2017 through 2021, 44 (28.2%) had prior Class I recalls. Predicates were identified for 127 index devices, with 56 (44.1%) using predicates with a Class I recall. One hundred four index devices were also used as predicates to support the authorization of 265 descendant devices, with 50 index devices (48.1%) authorizing a descendant with a Class I recall. Compared with matched controls, devices authorized using predicates with Class I recalls had a higher risk of subsequent Class I recall (6.40 [95% CI, 3.59-11.40]; P<.001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Many 510(k) devices subjected to Class I recalls in the US use predicates with a known history of Class I recalls. These devices have substantially higher risk of a subsequent Class I recall. Safeguards for the 510(k) pathway are needed to prevent problematic predicate selection and ensure patient safety.

This cross-sectional study evaluates the frequency of new devices receiving US Food and Drug Administration approval through its 510(k) pathway based on predicate devices that had been subject to a Class 1 recall.

Introduction

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) enables 99% of medical devices to progress to market under the 510(k) pathway.1 510(k) clearance requires manufacturers to demonstrate that new devices are “substantially equivalent” to already authorized “predicate” devices.2 To determine substantial equivalence, the FDA assesses whether new devices have similar indications for use and technological characteristics or whether any differences raise new concerns. Accordingly, the FDA relies on its “prior determination that a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness exists for the predicate device.”2

The 510(k) regulatory framework is grounded in 2 assumptions. First, for substantial equivalence to be legitimate, differences between devices and predicates should be limited in scope and function.2,3,4 Second, for predicates to be meaningful proxies for future device performance, regulators should be confident in predicate safety and effectiveness.

Given these assumptions, it is counterintuitive that many predicates are authorized without clinical testing and that current FDA regulations do not prohibit voluntarily recalled devices from serving as predicates for future device authorizations.4,5,6 Of greatest concern are Class I recalls, a designation the FDA assigns to devices with a reasonable probability of causing serious adverse health consequences or death.7 However, it remains unknown how often devices subject to Class I recalls are later used as predicates and how the use of recalled devices in authorization decisions affects the downstream risk of a Class I recall. Accordingly, this study evaluated the lineages of predicates for medical devices cleared under the 510(k) pathway and subject to Class I recalls from 2017 through 2021 to determine the frequency with which recalled devices use predicates subject to Class I recalls and the subsequent risk of a Class I recall in the newly authorized device.

Methods

Study Design and Sample Construction

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of 510(k) devices subject to Class I recalls from January 1, 2017, through December 31, 2021. We constructed our sample using the FDA’s annual log of Class I medical device recalls.8 Some recalled devices were listed multiple times in the annual log, and some listings included links to multiple official entries in the FDA’s Medical Device Recall database.9 To evaluate whether a repeat listing or entry referred to different devices, we examined the 510(k) numbers of each device listed for each entry.

After accounting for all duplicates, we identified all unique 510(k) devices associated with Class I–designated recalls from 2017 through 2021 and used these index devices to study predicate lineages.

Data Collection

We used the Devices@FDA database to determine each index device’s regulatory history and used the recall listing to determine the scope of the recall.10 We used the FDA’s Medical Device Recalls database to investigate whether the index device had prior recalls of any class before the most recent Class I recall from 2017 through 2021 (index year).9 When available, we analyzed decision memos to determine the type (eg, clinical vs nonclinical) and quality of evidence used to support market authorization.

Outcome Measures

We assessed predicate selection, clearance timelines, specialty classification, the number of units recalled, history of prior recalls, and evidence quality for each device. For devices that had undergone clinical testing, we assessed whether the trial used a randomized design, the study population size, and the length of follow-up.

Predicate Device Analysis

We reviewed decision memos available in the Devices@FDA database to identify the predicate(s) used by index devices to determine substantial equivalence. Some index devices cited the same predicate(s) (see eMethods section of Supplement 1). We accounted for all duplicates and used the Devices@FDA database to collect information about clearance year, regulatory classification, and evidence quality for each unique predicate.

Predicate Lineage Analysis

Because predicates can be used to authorize multiple devices, a comprehensive assessment of recall trends across predicate lineages required expanding our analysis beyond index devices to include all potential devices authorized by predicates (descendants).

To identify the descendant devices of predicates with known Class I recalls, we used Basil Systems, a commercially available regulatory intelligence platform (referred to hereafter as regulatory intelligence platform) that contains the entire text of all public regulatory filings in FDA databases and uses artificial intelligence to cross-reference and identify associations across different devices.11 We considered descendant devices authorized through September 1, 2022. To validate the regulatory intelligence platform, we examined each descendant device’s decision memo to confirm that the predicate was an index device from our sample (see the eMethods section of Supplement 1). Because some descendant devices cited multiple index devices in the sample as their predicates, we accounted for all duplicates, and then analyzed the regulatory and recall history of each descendant device.

For each predicate-descendant relationship, we assessed the amount of time that the descendants were marketed before the predicate Class I recall and assessed the recall history of descendants. Because manufacturers may continue using recalled predicates for future device authorizations, we determined whether predicate safety concerns preceded the authorization of its descendants.5,6 If so, we determined whether the FDA had terminated (indicating that the agency deemed the manufacturer’s efforts to remove or correct the defective device to be sufficient to prevent a future recall of the device for the same reason) a preceding recall before the predicate’s use in the authorization of its descendants.12 We then replicated this analysis to identify all descendants authorized using index devices as predicates and repeated the same process for validation and recall timeline reconstruction.

Matched Cohort Analysis

Lastly, we sought to assess the risk of a Class I recall for devices that used predicates subject to Class I recalls compared with devices that used recall-free predicates. We used the Devices@FDA database to identify 510(k) devices authorized within 12 months of a recalled device and with the same product code. We then selected the device that was closest in authorization date, had a different manufacturer (because device recalls are usually initiated by manufacturers who may have similar regulatory considerations across products), used predicates that were not included in the lineage of index devices, and was never subject to a recall of any class (because many index devices had recalls before the study period, so a true control would need to account for safety events across the entire product life cycle) as the matched control (for further information, see Supplement 1). Predicates and descendants were identified for each control device and examined for history of recalls.

Statistical Analyses

We described the characteristics of index devices, predicates, and descendants using proportions and median with interquartile range. We calculated risk ratios (RRs) to assess the association between use of a predicate subject to a Class I recall and the likelihood that a descendant was subject to a recall and calculated P values using the Fisher exact test. Two-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata SE version 17.0 (StataCorp).

Results

Index Device Characteristics

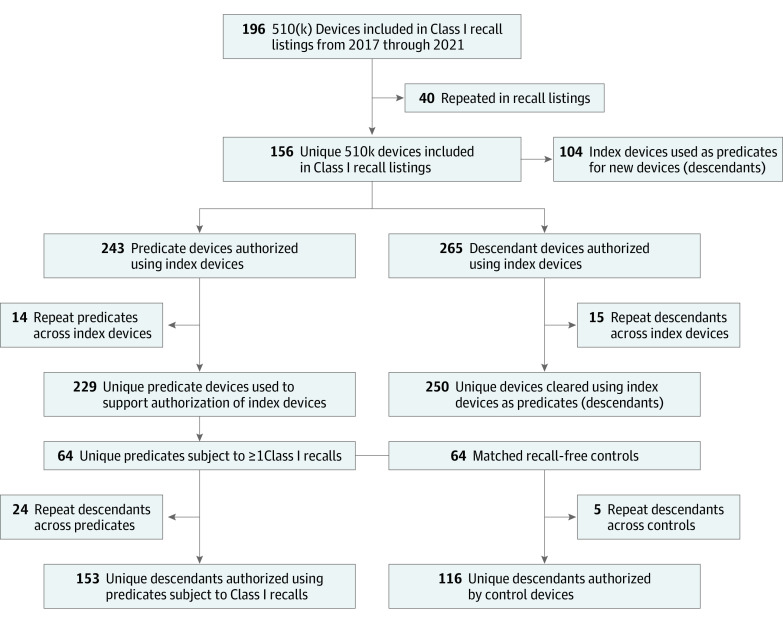

We identified a total of 135 entries in the FDA’s annual log of Class I recall listings that included 510(k) devices from 2017 through 2021. The median number of units recalled globally across these events was 9345 (IQR, 887-174 655). The most common FDA-determined cause for recall was device or software design (33.3%). The reason for recall was not publicly available for many devices (14.8%). These recall events encompassed 196 devices, of which 40 were duplicates, yielding a final sample of 156 unique index devices subject to a Class I recall (Figure).

Figure. Device Identification and Study Population Construction.

Among these 156 devices, the most common specialty categorizations were for cardiology (46 [29.5%]), anesthesiology (32 [20.5%]), and general hospital (28 [18.0%]). The most common product codes were for infusion pumps (11 [7.1%]), neurological stereotaxic instruments (8 [5.1%]), and noncontinuous ventilators (7 [4.5%]). The sample included 16 life-sustaining or supporting devices (10.3%) and 11 implantable devices (7.1%; Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of 510(k) Devices With Class I Recalls Between 2017-2021.

| No. (%) (n = 135) |

|

|---|---|

| Total No. of 510(k) Class I recall events | |

| 2021 | 24 (17.8) |

| 2020 | 21 (15.6) |

| 2019 | 36 (26.7) |

| 2018 | 24 (17.8) |

| 2017 | 30 (22.2) |

| No. of units recalled globally due to index device recall, median (IQR) | 9345 (887-174 655) |

| FDA-determined cause for recall | |

| Device or software design issue | 45 (33.3) |

| Process control issue | 21 (15.6) |

| Reason under investigation by firm | 20 (14.8) |

| Nonconforming material or component | 15 (11.1) |

| Component design or selection | 10 (7.4) |

| Component change control | 7 (5.2) |

| Use error | 4 (3.0) |

| Othera | 13 (9.6) |

| No. of unique 510(k) devices subject to Class I recalls | 156 |

| Regulation medical specialties | 130 |

| Cardiovascular | 46 (29.5) |

| Anesthesiology | 32 (20.5) |

| General hospital | 28 (18.0) |

| Neurology | 16 (10.3) |

| General and plastic surgery | 8 (5.1) |

| Most common product codes | |

| FRN (pump, infusion) | 11 (7.1) |

| HAW (neurological stereotaxic instrument) | 8 (5.1) |

| BZD (ventilator, noncontinuous, respirator) | 7 (4.5) |

| CBK (ventilator, continuous, facility use) | 7 (4.5) |

| DSP (system, balloon, intra-aortic and control) | 7 (4.5) |

| Special device designations | 156 |

| Life-sustaining or support device | 16 (10.3) |

| Implanted device | 11 (7.1) |

| Use of clinical data in 510(k) application | 156 |

| No clinical testing | 119 (76.3) |

| Information about device evidence unavailableb | 15 (9.6) |

| Insufficient information in decision memoc | 13 (8.3) |

| Included clinical data | 9 (5.8) |

| Recall history | |

| Time between clearance and recall of any class, median (IQR), y | 4.3 (1.6-10.7) |

| Time between clearance and first Class I recall, median (IQR), y | 7.3 (2.9-13.2) |

| No. of unique recalls per device, median (IQR) | 2 (1-4) |

| Subject to multiple recalls of any class | 86 (55.1) |

| Subject to multiple Class I recalls | 44 (28.2) |

Other reasons included unknown or determined by manufacturer, employee error, environmental control, labeling design, process change control, reprocessing controls, and software design.

No decision memo was posted for the index device in the Devices@FDA database, and as such, it was not possible to determine what, if any, premarket clinical testing was conducted.

Decision memo was available in the Devices@FDA database for the index device but did not state explicitly whether premarket clinical testing was conducted.

Only 9 index devices (5.8%) underwent premarket clinical testing. Of these, only 1 had a randomized controlled trial, with the remaining 8 devices either relying on retrospective studies or registry data or lacking further information about the clinical studies.13 Of the remaining index devices, 119 (76.3%) did not undergo clinical testing, and clinical testing could not be determined for 28 (17.9%) due to missing or insufficient information in the Devices@FDA database.

Of the 156 index devices subject to a Class I recall from 2017 through 2021, 86 (55.1%) were subject to at least 1 additional prior recall, including 44 (28.2%) with multiple Class I recalls. For these index devices, the median time elapsed between authorization and either their first recall of any class was 4.3 years (IQR, 1.6-10.7) or their first Class I recall was 7.3 years (IQR, 2.9-13.2).

Predicate Device Characteristics

Of the 156 index devices, information about predicates was not publicly available for 29 devices. The remaining 127 index devices cited 243 predicates, of which 14 were repeated across multiple index devices, yielding a total of 229 unique predicates (Table 2). Index devices used a median of 1 predicate (IQR, 1-2) to establish substantial equivalence. The median time elapsed between predicate authorization and index device clearance was 4.0 years (IQR, 2.0-7.9). Of the 127 index devices citing predicates, 92 (72.4%) used a predicate that had been subject to a recall, with 56 (44.1%) using a predicate subject to a Class I recall.

Table 2. Characteristics of Predicate Devices Used to Support Clearance of Recalled 510(k) Devices.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total No. of predicates cited by index devices | 243 |

| No. of predicates per device, median (IQR) | 1 (1-2) |

| Time between predicate and index device clearance, median (IQR), y | 4.0 (2.0-7.9) |

| No. of index devices with information about predicatesa | 127 |

| Using recalled predicates | 92 (72.4) |

| Using a predicate with ≥1 Class I–designated recall | 56 (44.1) |

| Total No. of unique predicatesb | 229 |

| Use of clinical data in predicate device’s 510(k) application | |

| Included clinical data | 10 (4.4) |

| No clinical testing | 137 (59.8) |

| Insufficient information in decision letterc | 35 (15.3) |

| Information about device evidence unavailabled | 47 (20.5) |

| No. of recalls per predicate, median (IQR) | 1 (0-2) |

| Predicate devices with history of recall | 123 (53.7) |

| Recalled predicate devices with at ≥1 Class I–designated recall | 64 (28.0) |

Of the 156 index devices, 127 had information available about their predicates.

Of the 243 predicates identified for the 127 index devices, 14 were duplicates (cited by multiple index devices); 229 reflects the number of unique predicates.

Decision memo was available in the Devices@FDA database for the index device but did not state explicitly whether premarket clinical testing was conducted.

No decision memo was posted for the index device in the Devices@FDA database, and as such, it was not possible to determine what, if any, premarket clinical testing was conducted.

Of the 229 unique predicates, only 10 (4.4%) were authorized using clinical data of safety and effectiveness, of which only 2 predicates included data from a randomized clinical trial.14,15 The decision memos for the other 8 devices did not include details about the clinical study. Of the remaining predicates, 137 (59.8%) did not undergo clinical testing and 82 (35.8%) could not be assessed for evidence quality due to missing or insufficient information in the Devices@FDA database. Among the 229 unique predicates, 123 (53.7%) were subject to at least 1 recall and 64 (28.0%) were subject to at least 1 Class I recall. The median number of recalls per predicate was 1 (IQR, 0-2).

Predicate Lineage Analysis

The 64 predicates subject to Class I recalls were used to support the authorization of a total of 177 descendant devices, with a median of 2 descendants (IQR, 1.5 to 3.5) per predicate (Table 3). Of these, 24 descendants shared common predicates, resulting in a total of 153 unique descendant devices (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). New devices were authorized a median of 4.7 years (IQR, 2.1 to 8.1) after predicate authorization and had been on the market for a median of 1.6 years (IQR, −0.4 to 7.2) prior to the Class I recall of their predicate. There were 88 instances (49.7%) when a predicate was subject to a recall of any class before being used for new device authorization. At least 1 of these recalls remained open (not yet terminated by the FDA, meaning the agency had not yet deemed the manufacturer’s actions sufficient to prevent the recall from recurring) at the time of the descendant’s authorization in 57 instances (64.8%). In 51 instances (28.8%), the predicate was subject to a Class I recall before being used to clear a descendant device, with this Class I recall still open (nonterminated) at the time of descendant authorization in 28 cases (54.9%).

Table 3. Characteristics of Predicate Lineages for Devices Subject to Class I Recalls.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Predicates subject to Class I recalls with predicate lineages | |

| Total No. | 64 |

| Devices authorized using predicatesa | 177 |

| Authorized devices per predicate, median (IQR) | 2 (1.5 to 3.5) |

| Time between predicate clearance and new device clearance, median (IQR), y | 4.7 (2.1 to 8.1) |

| Time between new device clearance and predicate Class I recall, median (IQR), y | 1.6 (−0.4 to 7.2) |

| Predicates recalled prior to new device clearance | 88 (49.7) |

| Preceding predicate recalls still open (nonterminated) when new device cleared, No. (subtotal %) | 57 (64.8) |

| Predicates subject to Class I recalls before new device clearance | 51 (28.8) |

| Preceding predicate Class I recalls still open (nonterminated) when new device cleared, No. (subtotal %) | 28 (54.9) |

| Index devices subject to Class I recalls with predicate lineagesb | |

| Total No. | 104 |

| Authorized using index devices as predicates, total No.c | 265 |

| Authorized devices per index device, median (IQR) | 2 (1 to 3) |

| Time between index device clearance and new device clearance, median (IQR), y | 4.2 (2.3 to 7.9) |

| Time between new device clearance and index device Class I recall, median (IQR), y | 2.8 (−0.4 to 7.7) |

| Index devices recalled before new device clearance | 134 (50.6) |

| Preceding index device recall still open (nonterminated) when new device cleared, No. (subtotal %) | 95 (70.9) |

| Index device subject to Class I recall before new device clearance | 76 (28.7) |

| Index device Class I recall still open (nonterminated) when new device cleared, No. (subtotal %) | 53 (69.7) |

| Index device authorizing devices later subject to any class recall | 63 (60.6) |

| Index device authorizing devices later subject to Class I recall | 50 (48.1) |

Refers to the cohort of 64 predicates subject to Class I recalls

Of the 156 index devices, 104 were documented in the regulatory intelligence platform as having been used as predicates for future device authorizations. These descendant relationships were subsequently validated using the Devices@FDA database.

Refers to the cohort of 104 index devices subject to Class I recalls.

Of the 156 index devices subject to Class I recalls, 104 also served as predicates for future devices, with 265 total authorized descendants and a median of 2 descendants (IQR, 1 to 3) per index device. Fifteen descendants were repeated across index device lineages, resulting in 250 unique descendants (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Descendants were cleared a median of 4.2 years (IQR, 2.3 to 7.9) after index device authorization, and had been on the market for a median of 2.8 years (IQR, −0.4 to 7.7) after the Class I recall of the index device serving as their predicate. There were 134 instances (50.6%) when an index device was subject to a recall of any class before being used for new device authorization, with this preceding recall remaining open (nonterminated) in 95 (70.9%) of these cases. In 76 instances (28.7%), the index device was subject to a Class I recall before being used to clear a descendant device, with this Class I recall still open (nonterminated) at the time of descendant authorization in 53 cases (69.7%). Of the 104 index devices later used as predicates, 63 (60.6%) supported authorization of a device that was later recalled, including 50 (48.1%) that authorized a device later subject to a Class I recall.

Matched Cohort Analysis

We identified matched controls for each of the 64 predicate devices subject to a Class I recall (Table 4). The median time elapsed between clearance of predicates (devices used to support the authorization of index devices and subject to Class I recalls) and their matched control (devices never subject to recalls) was 0.7 months (IQR, −2.4 to 2.5). Predicates authorized a total of 177 devices (153 unique), with 120 descendants (67.8%) subject to recalls of any class, and 103 (58.2%) subject to Class I recalls. Controls authorized a total of 121 devices (116 unique), with 25 control descendants (20.7%) subject to recalls of any class, and 11 (9.1%) subject to Class I recalls. The median number of descendants per device was 2 (IQR, 1.5 to 3.5) for predicates and 1 (IQR, 1 to 2) for controls. Compared with controls, devices that used predicates subject to Class I recalls had greater risk of a subsequent recall of any class (RR, 3.28 [95% CI, 2.28 to 4.72]; P < .001), including Class I recalls (RR, 6.40 [95% CI, 3.59 to 11.40]; P < .001).

Table 4. Risk of Class I Device Recall According to Predicate Recall Status.

| Characteristics | Cases (predicates with Class I recalls) | Matched controlsa | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Device population | |||

| Sample size, total No. | 64 | 64 | |

| Median months between clearance of cases and matched controls (IQR) | 0.7 (−2.4 to 2.5) | ||

| Descendant devices | |||

| Sample size, total No. | 177 | 121 | |

| Predicates per device, median (IQR) | 2 (1.5 to 3.5) | 1 (1 to 2) | |

| Descendant devices with recalls of any class, No. (%) | 120 (67.8) | 25 (20.7) | |

| Descendant devices with Class I recalls, No. (%) | 103 (58.2) | 11 (9.1) | |

| Statistical analyses, risk ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Relative risk of device recall of any class if authorized using a predicate subject to a Class I recall | 3.28 (2.28 to 4.72) | <.001 | |

| Relative risk of Class I device recall if authorized using a predicate subject to a Class I recall | 6.40 (3.59 to 11.40) | <.001 |

Matching was based on authorization date, manufacturer, and recall status for any class of recall.

Discussion

Among the 156 medical devices cleared under the 510(k) pathway and subject to a Class I recall from 2017 through 2021, 44.1% were authorized using predicates that were also subject to Class I recalls. Devices that were authorized using these predicates were 6.40 times more likely to be subject to a Class I recall than were devices that used recall-free predicates. Predicates had low rates of premarket clinical testing (4.4%) and were still used as predicates even after safety concerns arose in the postmarket setting (28.8%), including 28 cases for which devices were authorized while the predicate’s Class I recall was still ongoing. To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically illustrate how devices with known safety issues were more likely to have been authorized using a predicate with known safety issues support the clearance of new devices, many of which were subsequently found to have safety issues (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Moreover, we show that these devices were then used to support the clearance of new devices, many of which subsequently were found to have safety issues. Thus, problematic predicate selection may propagate safety concerns for 510(k) devices subject to Class I recalls, affecting multiple generations of devices.

Our study extends the prior literature by documenting the frequency with which recalled devices have a recalled predicate and the risk that these devices will subsequently be subject to a Class I recall. This study also extends the literature on predicate selection—which has historically been unidirectional because FDA databases do not enable researchers to determine whether a given device has been used to support future authorizations—by using a regulatory intelligence platform.16,17,18,19,20,21,22 Doing so, we reconstructed predicate lineages and found the risk of a future Class I recall was much higher when using a predicate with a Class I recall than using a control with no prior recalls. The findings therefore corroborate the concerns about predicate selection raised in both case studies of device recalls and by the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine), and systematically characterize the prevalence and public health implications of the practice of problematic predicate selection permitted under current regulations.4,20,23

The federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act appropriately prohibits devices from serving as predicates if they are subject to mandatory recalls, but there is a loophole.24,25 Manufacturers may use, and the FDA may authorize, devices that use recalled predicates if the predicate was recalled voluntarily by the manufacturer.5,6 Voluntary, manufacturer-initiated recalls are the usual approach for medical device recalls, with the FDA exercising its recall power only 3 times between 1990 and 2010.4 The FDA notes that “a submitter is permitted to cite as a predicate a device that has been recalled by the manufacturer due to safety concerns,” and estimates that this affects less than 1% of the approximately 3000 devices authorized annually under the 510(k) pathway.1,5,26 However, our study shows that this practice is common among devices subject to Class I recalls, with 28.8% of predicate descendants and 28.7% of index device descendants authorized after the Class I recall had occurred. Notably, most of these Class I recalls were still active at the time of new device authorization, meaning that descendants were being cleared using predicates for which safety concerns were not only known but had yet to be resolved. The consequences of this so-called recalled predicate loophole are clinically significant, with a median of 9345 units recalled for each Class I recall entry.

Concerns about the recalled predicate loophole are longstanding. The Safety of Untested and New Devices Act of 2012 sought to provide the FDA with the authority to prohibit the use of recalled predicates and improve public reporting of predicate lineages and associated safety signals.27 However, the legislation, along with other agency-level proposals to reform predicate oversight, did not progress into law or final rules.26,28 Instead, the FDA has sought to address concerns about device safety by implementing new performance standards, as reflected in the agency’s Safety and Performance Based Pathway for 510(k).29 Yet these steps do not resolve the fundamental regulatory gaps in the 510(k) pathway, which account for most Class I recalls.1,30,31 Meaningful improvements in device safety will require new standards for predicate selection, including guardrails against the use of devices subject to Class I recalls as predicates and robust requirements for manufacturers to disclose safety issues across predicate lineages.

Our findings also substantiate concerns about 510(k)’s evidentiary standards. An Institute of Medicine report previously noted that “clearance of a 510(k) submission was not a determination that the cleared device was safe or effective” because the FDA frequently determines substantial equivalence using “devices that were never individually evaluated for safety and effectiveness.”4 Indeed, only 11% of predicates have undergone clinical testing, with most studies using nonrandomized designs, small sample sizes, and short follow-up periods.4 This observation was consistent with our study of Class I recalls, with only 5.8% of index devices and 4.4% of predicates in our sample undergoing premarket clinical testing. Although the justification for 510(k)’s reduced standards was devices’ low- to moderate-risk nature, the implication of a Class I recall—serious adverse health consequences or death—suggests that current evidentiary expectations are misaligned with the true risk of such products. In fact, the baseline recall rate among predicate controls in our sample was higher than the average recall rate reported in the literature for 510(k) devices overall and for specialty-specific devices, illustrating the heterogeneity in risk among certain devices and product codes.32,33,34,35 Previous scholarship has also documented this misalignment, which has persisted even as more devices are cleared under 510(k) in lieu of the Premarket Approval pathway.36,37 These trends, coupled with the increase in Class I recalls, suggest that FDA’s risk classification framework may merit a reevaluation to ensure device safety.38

In addition, our results reveal the lack of transparency in medical device regulation. Although manufacturers are required by law to report information about clinical and nonclinical testing, previous research has highlighted low rates of compliance.39,40 In our study, we were able to obtain the regulatory history for most index devices. However, public information about predicates was missing for 17.3% of index devices, and information about premarket performance testing was insufficient or missing for 17.9% of index devices and 35.8% of predicates, respectively. Information gaps were primarily attributed to devices authorized before the early 2000s and illustrate the continued need for improvements in public transparency.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the FDA databases do not provide sufficiently detailed information about the reason for a given device’s recall to allow for a determination of the degree to which a previous predicate recall may be related to an index device recall. Second, our analysis of predicates was limited to devices for which regulatory filings were publicly available, which generally was not the case for devices authorized before 2000. This precluded multigenerational analyses of predicate lineages and posed limitations for the regulatory intelligence platform because the text-based analysis can only be performed for documents available in the public domain.41 Third, the matched cohort analysis was limited by the fact that recalls are initiated at the discretion of manufacturers rather than by a defined threshold for patient harm, potentially limiting the reliability of using Class I recalls as the exposure that differentiates cases and controls.

Conclusions

Many 510(k) devices subjected to Class I recalls in the US use predicates with a known history of Class I recalls. These devices have substantially higher risk of a subsequent Class I recall. Safeguards for the 510(k) pathway are needed to prevent problematic predicate selection and ensure patient safety.

eMethods. Sample construction, repeats within predicate lineages, validation of Basil Systems platform, matched cohort analysis

eFigure 1. Use and Consequences of Using Recalled Predicates in the 510(k) Pathway

eTable 1. Recall characteristics for unique descendant devices

eTable 2. Risk ratios for unique descendant devices

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Darrow JJ, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. FDA regulation and approval of medical devices, 1976-2000. JAMA. 2021;326(5):420-432. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The 510(k) program: evaluating substantial equivalence in premarket notifications. US Food and Drug Administration. February 5, 2018. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/510k-program-evaluating-substantial-equivalence-premarket-notifications-510k

- 3.Goldberger BA. The evolution of substantial equivalence in FDA’s premarket review of medical devices. Food Drug Law J. 2001;56(3):317-337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine . Medical Devices and the Public’s Health: the FDA 510(k) Clearance Process at 35 Years. The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho S. Fixing a 510(k) loophole: in support of the Sound Devices Act of 2012. April 10, 2012. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/11940233/ho_2012.pdf?sequence=1

- 6.Markey EJ. Defective devices, destroyed lives: loophole leaves patients unprotected from flawed medical devices. March 22, 2012. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.markey.senate.gov//imo/media/doc/Defective%20Devices%20Destroyed%20Lives%20FINAL.pdf

- 7.Recalls background and definitions. US Food and Drug Administration. July 31, 2014. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/safety/industry-guidance-recalls/recalls-background-and-definitions

- 8.Medical device recalls. US Food and Drug Administration. August 8, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-safety/medical-device-recalls

- 9.Medical device recalls database. US Food and Drug Administration. April 22, 2022. Accessed September 3, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfres/res.cfm

- 10.Devices@FDA database. US Food and Drug Administration. April 18, 2022. Accessed September 3, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/devicesatfda/index.cfm

- 11.Basil Systems. 2022. Accessed September 3, 2022. https://basilsystems.com/

- 12.Recalls, corrections, and removals (devices). US Food and Drug Administration. September 29, 2020. Accessed November 27, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/postmarket-requirements-devices/recalls-corrections-and-removals-devices

- 13.510(k) premarket notification: K162901. US Food and Drug Administration. November 21, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K162901

- 14.510(k) premarket notification: K173352. US Food and Drug Administration. November 21, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfPMN/pmn.cfm?ID=K173352

- 15.510(k) premarket notification: K113455. US Food and Drug Administration. November 21, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K113455

- 16.Ardaugh BM, Graves SE, Redberg RF. The 510(k) ancestry of a metal-on-metal hip implant. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):97-100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1211581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosh J, Bell CM, Urbach DR. The 510(k) ancestry of transvaginal mesh: when the subject is not a predicate. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(8):701-702. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liebeskind AY, Chen AC, Dhruva SS, Sedrakyan A. A 510(k) ancestry of robotic surgical systems. Int J Surg. 2022;98:106229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adashi EY, Robison KM, Cohen IG. Deadly legacy—the 510(k) path to medical device clearance. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(3):185-186. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.5558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadakia KT, Beckman AL, Ross JS, Krumholz HM. Renewing the call for reforms to medical device safety—the case of Penumbra. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(1):59-65. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zargar N, Carr A. The regulatory ancestral network of surgical meshes. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Premkumar A, Zhu A, Ying X, et al. The interconnected ancestral network of hip arthroplasty device approval. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(24):e1362-e1369. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman A. Predicate creep: the danger of multiple predicate devices. Ann Health Law. 2014;23:127-139. November 23, 2022. https://www.luc.edu/media/lucedu/law/centers/healthlaw/pdfs/advancedirective/pdfs/issue11/11_Freeman_Formatted.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.21 US Code § 360c—classification of devices intended for human use. Legal Information Institute. 2022. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/21/360c

- 25.21 CFR 810: medical device recall authority. US Food and Drug Administration. March 29, 2022. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-H/part-810

- 26.510(k) working group: preliminary report and recommendations. US Food and Drug Administration. August 2010. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/files/about%20fda/published/CDRH-Preliminary-Internal-Evaluations----Volume-I--510%28k%29-Working-Group-Preliminary-Report-and-Recommendations.pdf

- 27.Safety of Untested and New Devices Act of 2012. HR 3847, 112th Cong (2012). Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/112/bills/hr3847/BILLS-112hr3847ih.pdf

- 28.Nussbaum A. FDA device chief says approval “loophole” needs to be closed. Bloomberg. February 28, 2012. Accessed August 27, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/112691/download

- 29.Safety and performance based pathway. US Food and Drug Administration. September 20, 2019. Accessed September 3, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/safety-and-performance-based-pathway

- 30.Rathi VK, Ross JS. Modernizing the FDA’s 510(k) pathway. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(20):1891-1893. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1908654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Redberg RF, Dhruva SS. Moving from substantial equivalence to substantial improvement for 510(k) devices. JAMA. 2019;322(10):927-928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubin JR, Simon SD, Norrell K, Perera J, Gowen J, Cil A. Risk of recall among medical devices undergoing US Food and Drug Administration 510(k) clearance and premarket approval, 2008-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e217274. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.7274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somberg JC, McEwen P, Molnar J. Assessment of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular medical device recalls. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(11):1899-1903. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Day CS, Park DJ, Rozenshteyn FS, Owusu-Sarpong N, Gonzalez A. Analysis of FDA-approved orthopaedic devices and their recalls. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(6):517-524. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rathi VK, Gadkaree SK, Ross JS, et al. US Food and Drug Administration clearance of moderate-risk otolaryngologic devices via the 510(k) process, 1997-2016. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157(4):608-617. doi: 10.1177/0194599817721689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuckerman DM, Brown P, Nissen SE. Medical device recalls and the FDA approval process. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(11):1006-1011. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redberg RF, Dhruva SS. Medical device recalls: get it right the first time: comment on “Medical device recalls and the FDA approval process.” Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(11):1011-1012. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Recall Index, 2022: product recall United States. Edition 2: medical devices. Accessed August 30, 2022.2022. https://marketing.sedgwick.com/acton/media/4952/us-2022-recall-index-report-download-edition-2-pr

- 39.Safe Medical Devices Act of 1990. HR 3095, 101st Cong (1990). Accessed September 3, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/3095

- 40.Zuckerman D, Brown P, Das A. Lack of publicly available scientific evidence on the safety and effectiveness of implanted medical devices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1781-1787. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pai DB. Mapping the genealogy of medical device predicates in the United States. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Sample construction, repeats within predicate lineages, validation of Basil Systems platform, matched cohort analysis

eFigure 1. Use and Consequences of Using Recalled Predicates in the 510(k) Pathway

eTable 1. Recall characteristics for unique descendant devices

eTable 2. Risk ratios for unique descendant devices

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement