Key Points

Question

What outcomes are associated with delays in the diagnosis and treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP)?

Findings

In this large database cohort study of 135 034 patients with hypercalcemia, those who were identified as high-risk and without a diagnosis and whose duration of workup or time from diagnosis to treatment exceeded 1 year experienced increased disease sequelae.

Meaning

These findings suggest that missed diagnoses and prolonged time to diagnosis and treatment of PHP are associated with increased disease burden.

This cohort study examines the consequences of missed diagnoses and prolonged time to diagnosis and treatment of primary hyperparathyroidism.

Abstract

Importance

Despite access to routine laboratory evaluation, primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP) remains underdiagnosed and undertreated.

Objective

To determine the consequences associated with missed diagnoses and prolonged time to diagnosis and treatment of PHP.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This is a retrospective cohort study of patients older than 40 years with 2 instances of hypercalcemia during 2010 to 2020 and 3 years of follow-up. Patients were recruited from 63 health care organizations in the TriNetX Research Network. Data analysis was performed from January 2010 to September 2020.

Exposures

Elevated serum calcium.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Existing symptoms and diagnoses associated with PHP (osteoporosis, fractures, urolithiasis, major depressive disorder, anxiety, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, malaise or fatigue, joint pain or myalgias, constipation, insomnia, polyuria, weakness, abdominal pain, headache, nausea, amnesia, and gallstones) compared in patients deemed high-risk and without a diagnosis and matched controls, and those who experienced times from documented hypercalcemia to diagnosis and diagnosis to treatment within or beyond 1 year.

Results

There were 135 034 patients analyzed (96 554 women [72%]; 28 892 Black patients [21%] and 88 010 White patients [65%]; 3608 Hispanic patients [3%] and 98 279 non-Hispanic patients [73%]; mean [SD] age, 63 [10] years). Two groups without a documented diagnosis of PHP were identified as high risk: 20 176 patients (14.9%) with parathyroid hormone greater than or equal to 50 pg/mL and 24 905 patients (18.4%) with no parathyroid hormone level obtained or recorded explanation for hypercalcemia. High-risk patients experienced significantly increased rates of all associated symptoms and diagnoses compared with matched controls. Just 9.7% of those with hypercalcemia (13 136 patients) had a diagnosis of PHP. Compared with individuals who received a diagnosis within 1 year of hypercalcemia, those whose workup exceeded 1 year had significantly increased rates of major depressive disorder, anxiety, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, malaise or fatigue, joint pain or myalgias, polyuria, weakness, abdominal pain, and headache at 3 years. The rate of osteoporosis increased from 17.1% (628 patients) to 25.4% (935 patients) over the study period in the group with delayed diagnosis. Among those with a diagnosis, 5280 patients (40.2%) underwent parathyroidectomy. Surgery beyond 1 year of diagnosis was associated with significantly increased rates of osteoporosis and hypertension at 3 years after diagnosis compared with those treated within 1 year.

Conclusions and Relevance

Many patients were at high risk for PHP without a documented diagnosis. Complications in these patients, as well as those who received a diagnosis after prolonged workup or time to treatment, resulted in patient harm. System-level interventions are necessary to ensure proper diagnosis and prompt treatment of PHP.

Introduction

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP) is caused by a benign overgrowth of single or multiple parathyroid glands. It is the most common cause of hypercalcemia,1,2 with a prevalence of 0.1% to 1.0% and incidence of 28 cases per 100 000.3,4,5 A biochemical diagnosis is made in the setting of elevated calcium and nonsuppressed parathyroid hormone (PTH).1 Classic symptomatic PHP is associated with osteoporosis, fracture, and urolithiasis. However, the diagnosis can be missed because patients may present with nonspecific symptoms. These include memory loss, severe fatigue, depression, sleep disturbances, bone and joint pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD),6 and gallstones,7,8 which deteriorate quality of life.9 Although it is benign, PHP is associated with hypertension (HTN) and increased risk of cardiovascular mortality.10

Treatment for PHP is predominantly surgical via excision of the abnormal glands. According to the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons guidelines,11 surgery is indicated for any of the following criteria: (1) presence of symptoms; (2) calcium elevation greater than 1 mg/dL above the upper limit of normal; (3) osteoporosis or history of fractures; (4) nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, or 24-hour urine calcium greater than 400 mg/dL; (5) estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min; and (6) diagnosis at age 50 years or younger. Parathyroidectomy improves bone density, lowers fracture risk, reduces nephrolithiasis, and improves neuropsychological symptoms.12

Because many patients are asymptomatic and PHP is incidentally discovered, the diagnosis is frequently not actively pursued to identify candidates for surgery.13,14,15,16,17,18,19 In this cohort study, we sought to use the largest sample size to date from health care organizations (HCOs) across the US to determine the outcomes associated with missed diagnoses, increased time to diagnosis, and treatment delay on patients. We hypothesized that all would be associated with increased symptoms and diagnoses associated with PHP.

Methods

Data were collected from the TriNetX Research Network (Cambridge, Massachusetts), which provided access to electronic medical records from approximately 58 million individuals aged 40 years and older from 63 HCOs across the US.20 TriNetX is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, only contains deidentified data, and was exempted by the Penn State institutional review board from the need for informed consent, in accordance with 45 CFR §46. This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cohort studies. Race and ethnicity were determined from the database and were analyzed in this study to control for demographic differences between cohorts.

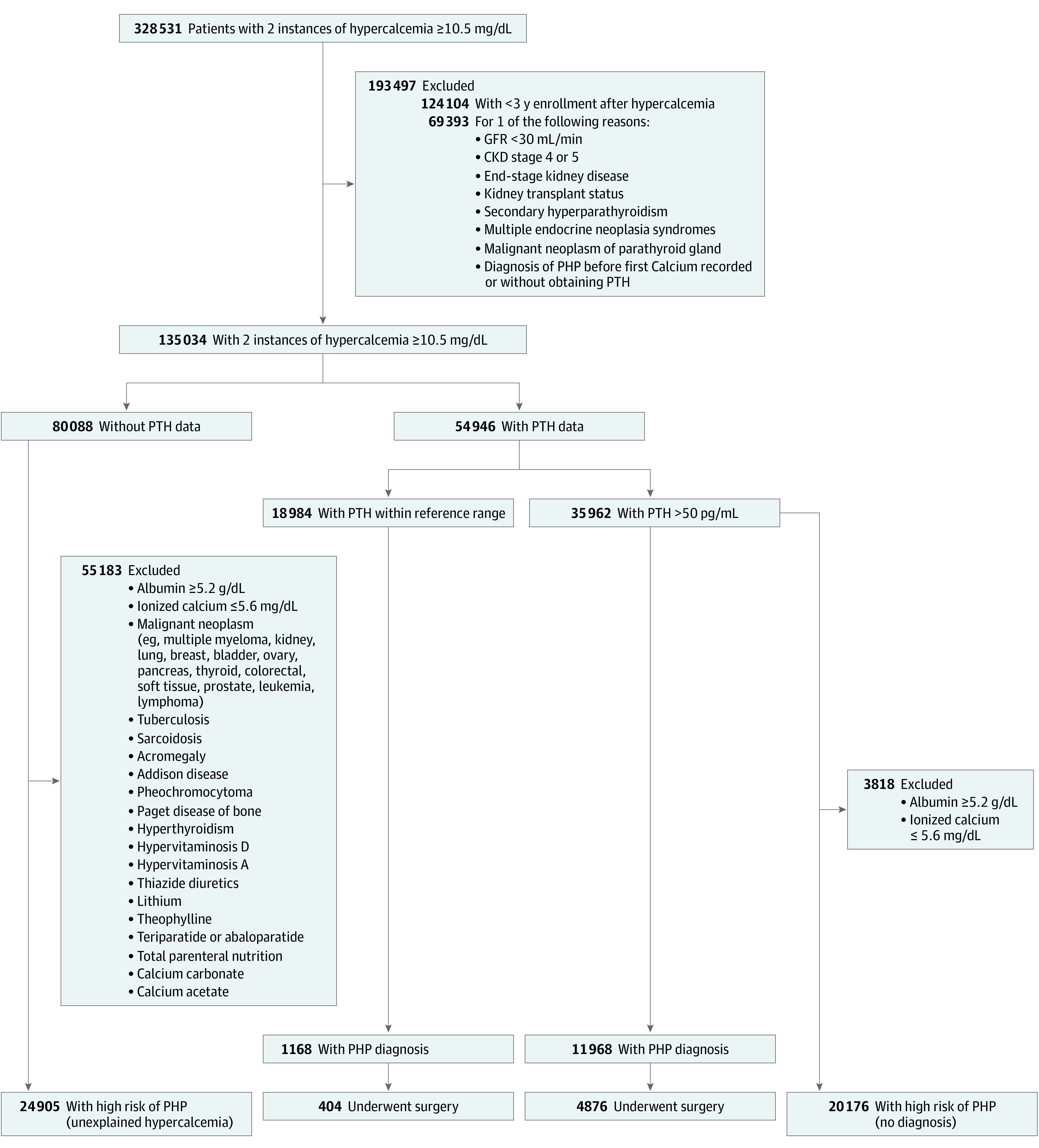

The database was queried using diagnosis and procedure codes to identify patients with at least 2 instances of documented hypercalcemia (serum calcium ≥10.5 mg/dL; to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.25) during 2010 to 2020. Individuals younger than 40 years were excluded to avoid differences in the definition of hypercalcemia based on age.21 Serum calcium of greater than or equal to 10.5 mg/dL was a conservative threshold for hypercalcemia to account for variations among laboratories.22 To ensure that patients were not lost to follow-up, records were included only if they had continuous enrollment in the database 3 years after initial documentation of hypercalcemia. In addition, those with history of severe kidney insufficiency (glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min) or kidney transplant were excluded to eliminate potential confounding effects of secondary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism. Patients with hyperparathyroidism in the context of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 or 2A, parathyroid carcinoma, or a documented diagnosis of PHP before their first calcium level or without record of PTH levels were also excluded (Figure).

Figure. Flowchart of Cohort With Hypercalcemia.

To convert albumin to grams per liter, multiply by 10; calcium to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.25; parathyroid hormone (PTH) to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1. CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; PHP, primary hyperparathyroidism.

Patients with hypercalcemia were grouped according to whether their PTH levels had been obtained. To identify individuals at high risk for undiagnosed PHP among those without recorded PTH, additional criteria were applied to distinguish hypercalcemia that may have been due to other causes (a complete list is shown in the Figure).23,24 Patients with ionized calcium within the reference range (≤5.6 mg/dL) or albumin greater than or equal to 5.2 g/dL (to convert to grams per liter, multiply by 10) were separated from high-risk groups to account for artificial elevations in serum calcium. Codes used to execute the search are available in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Two groups were identified with a high probability of undetected PHP: (1) patients with hypercalcemia in the setting of PTH greater than or equal to 50 pg/mL (to convert to nanograms per liter, multiply by 1) and (2) those with unexplained hypercalcemia without further workup (Figure). Although the reference laboratory range for PTH is 10 to 65 pg/mL, concentrations as low as 25 pg/mL may be abnormally elevated and indicative of PHP in the setting of hypercalcemia.25,26 Therefore, PTH greater than or equal to 50 pg/mL was chosen as a conservative cutoff for this study.27,28 We assumed the latter group was at high risk for PHP because more than 90% of hypercalcemia cases are attributed to malignant neoplasms or PHP,29 and we excluded patients with malignant neoplasms or other potential causes of hypercalcemia. Although it is possible that some patients with undiagnosed malignant neoplasms were classified as high risk, it is much more likely that this group had undiagnosed PHP given the indolent nature of symptoms compared with those of cancer.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed from January 2010 to September 2020. Statistical analyses were performed within TriNetX to compare rates of symptoms and associated diagnoses between each high-risk group and controls (osteoporosis or osteopenia, fractures, urolithiasis, major depressive disorder [MDD], anxiety disorders, HTN, GERD, malaise or fatigue, joint pain or myalgias, constipation, insomnia, polyuria, weakness, abdominal pain, headache, nausea, amnesia, and gallstones).6 Two control groups were created by querying TriNetX for individuals without hypercalcemia with no history of elevated PTH, a diagnosis of PHP, or an exclusionary condition. The second control group also excluded patients with any of the aforementioned alternative causes of hypercalcemia. To limit confounding, the first high-risk group was compared with the first control group, whereas the second high-risk group was compared with the second control group. All comparisons were 1:1 propensity score–matched for age, sex, ethnicity, and race using nearest neighbor methods without replacement, and a caliper of 0.1 times the SD. Additional similar analyses were conducted comparing each high-risk group, patients with a confirmed diagnosis of PHP with controls, each high-risk group with those with a confirmed diagnosis, cohorts with varying PTH thresholds, patients who received a diagnosis within or beyond 1 year of the first instance of hypercalcemia, and patients treated within or beyond 1 year of diagnosis.

Outcomes were recorded during multiple time frames following the first instance of hypercalcemia: 0 to less than or equal to 1 year, 366 days to less than or equal to 2 years, and 731 days to less than or equal to 3 years. The exception was analysis of time from diagnosis to surgery, where time of diagnosis served as the index event. For this analysis, patients who did not have 3 years of follow-up after diagnosis were also excluded. To compare mean calcium and PTH levels between cohorts, 2-sided t tests were performed. Statistical significance was defined as P < .003, determined by applying a Bonferroni correction for 18 tests to an α of .05. To explore the association of region, regional data were used to compare the odds that patients identified as high-risk belonged to HCOs in the southern, northeastern, midwestern, and western US. Data analysis was performed within the TriNetX platform.

Results

Among 135 034 patients with hypercalcemia who met the inclusion criteria (28 892 Black patients [21%] and 88 010 White patients [65%]; 3608 Hispanic patients [3%] and 98 279 non-Hispanic patients [73%]), 96 554 (72%) were female and 38 466 were (28%) male, with a mean (SD) age of 63 (10) years at first documentation of hypercalcemia. Complete demographics are described in Table 1. The number of individuals analyzed at each stage of the study are presented in the Figure.

Table 1. Cohort Demographics.

| Clinical characteristica | Patients, No. (%) (N = 135 034) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 96 554)b | Male (n = 38 466)b | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63.3 (10.3) | 61.4 (10.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2573 (2.7) | 1035 (2.7) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 70 418 (72.9) | 27 861 (72.4) |

| Unknown | 23 563 (24.4) | 9570 (24.9) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 1306 (1.4) | 505 (1.3) |

| Black or African American | 21 963 (22.8) | 6929 (18.0) |

| White | 62 007 (64.2) | 26 003 (67.6) |

| Otherc | 419 (0.4) | 191 (0.5) |

| Unknown | 10 859 (11.2) | 4838 (12.6) |

Sex, ethnicity, and race were classified according to documentation in electronic medical records.

Fourteen patients had an unknown sex.

Other race included American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.

Laboratory Testing and Diagnosis

Of 135 034 patients with hypercalcemia, 54 946 (40.7%) underwent further evaluation via obtaining PTH levels (Figure). Of the patients whose PTH levels were obtained, 13 136 (23.9%) had a diagnosis of PHP, 17 816 (32.4%) had PTH less than 50 pg/mL and no diagnosis, and the remaining 23 994 (43.7%) had PTH greater than or equal to 50 pg/mL yet did not receive a diagnosis. After excluding 3818 patients with elevated albumin or normal ionized calcium in the latter group, 20 176 patients (14.9% of the entire cohort) were identified as the first high-risk cohort.

Within the initial hypercalcemic group, 80 088 patients (59.3%) did not have PTH levels obtained (Figure). Among those without PTH levels available, 55 183 (68.9%) had other potential causes for hypercalcemia, whereas 24 905 (31.1%, or 18.4% of the entire cohort) lacked another explanation for hypercalcemia and had no diagnosis of PHP. This represented the second high-risk group.

Incidence of Symptoms in High-risk Patients Without a Diagnosis

Compared with matched controls without hypercalcemia, high-risk patients with hypercalcemia and PTH greater than or equal to 50 pg/mL experienced significantly increased rates of all symptoms and diagnoses associated with PHP (Table 2). Patients with unexplained hypercalcemia without documented additional workup also experienced significantly increased rates vs controls (Table 2). Over the 3-year follow-up, the first high-risk group had significantly increased rates of most symptoms and diagnoses vs the second high-risk group, with the exception of abdominal pain, amnesia, and gallstones (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Patients with confirmed PHP had significantly increased rates of all disease sequelae vs controls (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients in High-risk Group 1 and Patients in High-risk Group 2 Compared With Matched Controls.

| Time and diagnosis | Patients, No. (%) after matching | OR (95% CI) | P valueb | Patients, No. (%) after matching | OR (95% CI) | P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk group 1 (n = 20 175)a | Matched controls (n = 20 175) | High-risk group 2 (n = 24 905)c | Matched controls (n = 24 905) | |||||

| 0 to ≤1 y | ||||||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 2662 (13.2) | 1099 (5.4) | 2.64 (2.45-2.84) | <.001 | 1423 (5.7) | 1065 (4.3) | 1.36 (1.25-1.47) | <.001 |

| Fractures | 719 (3.6) | 478 (2.4) | 1.52 (1.35-1.71) | <.001 | 691 (2.8) | 603 (2.4) | 1.15 (1.03-1.29) | .01 |

| Urolithiasis | 771 (3.8) | 281 (1.4) | 2.81 (2.45-3.23) | <.001 | 746 (3.0) | 378 (1.5) | 2.00 (1.77-2.27) | <.001 |

| MDD | 2009 (10.0) | 1393 (6.9) | 1.49 (1.39-1.60) | <.001 | 2507 (10.1) | 1565 (6.3) | 1.67 (1.56-1.78) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorders | 1920 (9.5) | 1347 (6.7) | 1.47 (1.37-1.58) | <.001 | 2481 (10.0) | 1689 (6.8) | 1.52 (1.43-1.62) | <.001 |

| HTN | 9107 (45.1) | 6231 (30.9) | 1.84 (1.77-1.92) | <.001 | 8872 (35.6) | 5795 (23.3) | 1.83 (1.76-1.90) | <.001 |

| GERD | 2952 (14.6) | 2047 (10.1) | 1.52 (1.43-1.61) | <.001 | 3186 (12.8) | 2241 (9.0) | 1.48 (1.40-1.57) | <.001 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 2065 (10.2) | 1328 (6.6) | 1.62 (1.51-1.74) | <.001 | 2086 (8.4) | 1455 (5.8) | 1.47 (1.38-1.58) | <.001 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 3461 (17.2) | 2385 (11.8) | 1.55 (1.46-1.63) | <.001 | 3745 (15.0) | 2834 (11.4) | 1.38 (1.31-1.45) | <.001 |

| Constipation | 1247 (6.2) | 719 (3.6) | 1.78 (1.54-1.96) | <.001 | 1334 (5.4) | 687 (2.8) | 2.00 (1.82-2.19) | <.001 |

| Insomnia | 885 (4.4) | 524 (2.6) | 1.72 (1.54-1.92) | <.001 | 937 (3.8) | 570 (2.3) | 1.67 (1.50-1.86) | <.001 |

| Polyuria | 874 (4.3) | 506 (2.5) | 1.76 (1.58-1.97) | <.001 | 905 (3.6) | 607 (2.4) | 1.51 (1.36-1.68) | <.001 |

| Weakness | 1374 (6.8) | 872 (4.3) | 1.62 (1.48-1.77) | <.001 | 1413 (5.7) | 891 (3.6) | 1.62 (1.49-1.77) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 2142 (10.6) | 1573 (7.8) | 1.41 (1.31-1.50) | <.001 | 3067 (12.3) | 1916 (7.7) | 1.69 (1.59-1.79) | <.001 |

| Headache | 1104 (5.5) | 794 (3.9) | 1.41 (1.29-1.55) | <.001 | 1320 (5.3) | 891 (3.6) | 1.51 (1.38-1.65) | <.001 |

| Nausea | 814 (4.0) | 498 (2.5) | 1.66 (1.48-1.86) | <.001 | 1013 (4.1) | 567 (2.3) | 1.82 (1.64-2.02) | <.001 |

| Amnesia | 738 (3.7) | 506 (2.5) | 1.48 (1.32-1.66) | <.001 | 992 (4.0) | 566 (2.3) | 1.78 (1.61-1.98) | <.001 |

| Gallstones | 373 (1.8) | 217 (1.1) | 1.73 (1.46-2.05) | <.001 | 480 (1.9) | 282 (1.1) | 1.72 (1.48-1.98) | <.001 |

| 366 d to ≤2 y | ||||||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 2718 (13.5) | 1070 (5.3) | 2.78 (2.58-2.99) | <.001 | 1461 (5.9) | 1002 (4.0) | 1.49 (1.37-1.61) | <.001 |

| Fractures | 647 (3.2) | 367 (1.8) | 1.79 (1.57-2.04) | <.001 | 581 (2.3) | 370 (1.5) | 1.58 (1.39-1.81) | <.001 |

| Urolithiasis | 651 (3.2) | 198 (1.0) | 3.36 (2.87-3.95) | <.001 | 539 (2.2) | 225 (0.9) | 2.43 (2.08-2.84) | <.001 |

| MDD | 1909 (9.5) | 1164 (5.8) | 1.71 (1.58-1.84) | <.001 | 2088 (8.4) | 1213 (4.9) | 1.79 (1.66-1.92) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorders | 1740 (8.6) | 1105 (5.5) | 1.63 (1.51-1.76) | <.001 | 2056 (8.3) | 1379 (5.5) | 1.54 (1.43-1.65) | <.001 |

| HTN | 8940 (44.3) | 5057 (25.1) | 2.38 (2.28-2.48) | <.001 | 7814 (31.4) | 4327 (17.4) | 2.17 (2.08-2.27) | <.001 |

| GERD | 2690 (13.3) | 1606 (8.0) | 1.78 (1.67-1.90) | <.001 | 2676 (10.7) | 1643 (6.6) | 1.70 (1.60-1.82) | <.001 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 1531 (7.6) | 898 (4.5) | 1.76 (1.62-1.92) | <.001 | 1487 (6.0) | 958 (3.8) | 1.59 (1.46-1.73) | <.001 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 3327 (16.5) | 2004 (9.9) | 1.79 (1.69-1.90) | <.001 | 3167 (12.7) | 2285 (9.2) | 1.44 (1.36-1.53) | <.001 |

| Constipation | 1001 (5.0) | 472 (2.3) | 2.18 (1.95-2.44) | <.001 | 935 (3.8) | 443 (1.8) | 2.15 (1.92-2.42) | <.001 |

| Insomnia | 725 (3.6) | 395 (2.0) | 1.86 (1.65-2.11) | <.001 | 754 (3.0) | 418 (1.7) | 1.83 (1.62-2.06) | <.001 |

| Polyuria | 786 (3.9) | 420 (2.1) | 1.91 (1.69-2.15) | <.001 | 724 (2.9) | 515 (2.1) | 1.42 (1.27-1.59) | <.001 |

| Weakness | 948 (4.7) | 547 (2.8) | 1.77 (1.59-1.97) | <.001 | 949 (3.8) | 548 (2.2) | 1.76 (1.58-1.96) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 1698 (8.4) | 949 (4.7) | 1.86 (1.72-2.02) | <.001 | 2020 (8.1) | 1102 (4.4) | 1.91 (1.77-2.06) | <.001 |

| Headache | 923 (4.6) | 505 (2.5) | 1.87 (1.67-2.09) | <.001 | 890 (3.6) | 543 (2.2) | 1.66 (1.49-1.85) | <.001 |

| Nausea | 598 (3.0) | 292 (1.4) | 2.08 (1.81-2.40) | <.001 | 614 (2.5) | 277 (1.1) | 2.25 (1.95-2.59) | <.001 |

| Amnesia | 635 (3.1) | 373 (1.8) | 1.73 (1.52-1.96) | <.001 | 683 (2.7) | 336 (1.3) | 2.06 (1.81-2.35) | <.001 |

| Gallstones | 265 (1.3) | 124 (0.6) | 2.15 (1.74-2.67) | <.001 | 264 (1.1) | 107 (0.4) | 2.48 (1.98-3.11) | <.001 |

| 731 d to ≤3 y | ||||||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 2945 (14.6) | 1254 (6.2) | 2.58 (2.41-2.76) | <.001 | 1635 (6.6) | 1117 (4.5) | 1.50 (1.38-1.62) | <.001 |

| Fractures | 679 (3.4) | 418 (2.1) | 1.65 (1.46-1.86) | <.001 | 616 (2.5) | 424 (1.7) | 1.46 (1.29-1.66) | <.001 |

| Urolithiasis | 644 (3.2) | 175 (0.9) | 3.77 (3.19-4.46) | <.001 | 549 (2.2) | 230 (0.9) | 2.42 (2.07-2.82) | <.001 |

| MDD | 2024 (10.0) | 1200 (5.9) | 1.76 (1.64-1.90) | <.001 | 2087 (8.4) | 1247 (5.0) | 1.74 (1.61-1.87) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorders | 1835 (9.1) | 1163 (5.8) | 1.64 (1.52-1.77) | <.001 | 2175 (8.7) | 1433 (5.8) | 1.57 (1.46-1.68) | <.001 |

| HTN | 9124 (45.2) | 5346 (26.5) | 2.29 (2.20-2.39) | <.001 | 8121 (32.6) | 4670 (18.8) | 2.10 (2.01-2.19) | <.001 |

| GERD | 2800 (13.9) | 1760 (8.7) | 1.69 (1.58-1.80) | <.001 | 2801 (11.2) | 1803 (7.2) | 1.62 (1.53-1.73) | <.001 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 1574 (7.8) | 917 (4.5) | 1.78 (1.63-1.93) | <.001 | 1488 (6.0) | 1028 (4.1) | 1.48 (1.36-1.60) | <.001 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 3285 (16.3) | 2082 (10.3) | 1.69 (1.59-1.79) | <.001 | 3246 (13.0) | 2361 (9.5) | 1.43 (1.35-1.51) | <.001 |

| Constipation | 1017 (5.0) | 511 (2.5) | 2.04 (1.83-2.28) | <.001 | 948 (3.8) | 513 (2.1) | 1.88 (1.69-2.10) | <.001 |

| Insomnia | 774 (3.8) | 436 (2.2) | 1.81 (1.60-2.03) | <.001 | 765 (3.1) | 484 (1.9) | 1.60 (1.43-1.79) | <.001 |

| Polyuria | 849 (4.2) | 511 (2.5) | 1.69 (1.51-1.89) | <.001 | 737 (3.0) | 525 (2.1) | 1.42 (1.26-1.59) | <.001 |

| Weakness | 1034 (5.1) | 577 (2.9) | 1.84 (1.65-2.04) | <.001 | 914 (3.7) | 587 (2.4) | 1.58 (1.42-1.75) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 1725 (8.6) | 1041 (5.2) | 1.72 (1.59-1.86) | <.001 | 2056 (8.3) | 1145 (4.6) | 1.87 (1.73-2.01) | <.001 |

| Headache | 848 (4.2) | 480 (2.4) | 1.80 (1.61-2.02) | <.001 | 892 (3.6) | 542 (2.2) | 1.67 (1.50-1.86) | <.001 |

| Nausea | 576 (2.9) | 289 (1.3) | 2.02 (1.75-2.33) | <.001 | 575 (2.3) | 303 (1.2) | 1.92 (1.67-2.21) | <.001 |

| Amnesia | 681 (3.4) | 404 (2.0) | 1.71 (1.51-1.94) | <.001 | 737 (3.0) | 379 (1.5) | 1.97 (1.74-2.24) | <.001 |

| Gallstones | 267 (1.3) | 132 (0.7) | 2.04 (1.65-2.51) | <.001 | 296 (1.2) | 144 (0.6) | 2.07 (1.69-2.53) | <.001 |

| Entire study period (0-3 y) | ||||||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 4447 (22.0) | 2221 (11.0) | 2.29 (2.16-2.42) | <.001 | 2758 (11.1) | 2012 (8.1) | 1.42 (1.33-1.51) | <.001 |

| Fractures | 1450 (7.2) | 1044 (5.2) | 1.42 (1.31-1.54) | <.001 | 1501 (6.0) | 1166 (4.7) | 1.31 (1.21-1.41) | <.001 |

| Urolithiasis | 1262 (6.3) | 470 (2.3) | 2.80 (2.51-3.12) | <.001 | 1315 (5.3) | 637 (2.6) | 2.12 (1.93-2.34) | <.001 |

| MDD | 3218 (16.0) | 2253 (11.2) | 1.51 (1.43-1.60) | <.001 | 3824 (15.4) | 2491 (10.0) | 1.63 (1.55-1.72) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorders | 3097 (15.4) | 2177 (10.8) | 1.50 (1.41-1.59) | <.001 | 3889 (15.6) | 2772 (11.1) | 1.48 (1.40-1.56) | <.001 |

| HTN | 11 187 (55.5) | 8114 (40.2) | 1.85 (1.78-1.93) | <.001 | 11 436 (45.9) | 7813 (31.4) | 1.86 (1.79-1.93) | <.001 |

| GERD | 4602 (22.8) | 3430 (17.0) | 1.44 (1.33-1.52) | <.001 | 5035 (20.2) | 3588 (14.4) | 1.51 (1.44-1.58) | <.001 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 3687 (18.3) | 2428 (12.0) | 1.63 (1.54-1.73) | <.001 | 3812 (15.3) | 2716 (10.9) | 1.48 (1.40-1.56) | <.001 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 6266 (31.1) | 4591 (22.8) | 1.53 (1.46-1.60) | <.001 | 6786 (27.2) | 5395 (21.7) | 1.35 (1.30-1.41) | <.001 |

| Constipation | 2335 (11.6) | 1316 (6.5) | 1.88 (1.75-2.01) | <.001 | 2447 (9.8) | 1306 (5.2) | 1.97 (1.84-2.12) | <.001 |

| Insomnia | 1592 (7.9) | 994 (4.9) | 1.65 (1.52-1.79) | <.001 | 1675 (6.7) | 1034 (4.2) | 1.67 (1.54-1.80) | <.001 |

| Polyuria | 1905 (9.4) | 1205 (6.0) | 1.64 (1.52-1.77) | <.001 | 1871 (7.5) | 1319 (5.3) | 1.45 (1.35-1.56) | <.001 |

| Weakness | 2522 (12.5) | 1670 (8.3) | 1.58 (1.52-1.77) | <.001 | 2639 (10.6) | 1690 (6.8) | 1.63 (1.53-1.74) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 3979 (19.7) | 2844 (14.1) | 1.50 (1.42-1.58) | <.001 | 5188 (20.8) | 3406 (13.7) | 1.66 (1.58-1.74) | <.001 |

| Headache | 2155 (10.7) | 1453 (7.2) | 1.54 (1.44-1.65) | <.001 | 2462 (9.9) | 1636 (6.6) | 1.56 (1.46-1.67) | <.001 |

| Nausea | 1518 (7.5) | 919 (4.6) | 1.71 (1.57-1.86) | <.001 | 1795 (7.2) | 1009 (4.1) | 1.84 (1.70-1.99) | <.001 |

| Amnesia | 1484 (7.4) | 965 (4.8) | 1.58 (1.45-1.72) | <.001 | 1852 (7.4) | 1005 (4.0) | 1.91 (1.77-2.07) | <.001 |

| Gallstones | 708 (3.5) | 442 (2.2) | 1.62 (1.44-1.83) | <.001 | 866 (3.5) | 475 (1.9) | 1.85 (1.65-2.08) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HTN, hypertension; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio.

High risk-group 1 included a total of 20 176 patients with hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone greater than or equal to 50 pg/mL.

Statistical significance is defined as P < .003.

High-risk group 2 included 24 905 patients with unexplained hypercalcemia and no further workup.

Compared with patients with a diagnosis, over the entire study period (0-3 years), the first high-risk group had significantly decreased rates of osteoporosis, urolithiasis, GERD, malaise and fatigue, polyuria, and weakness; however, there were no differences in other symptoms (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). There were also individual years when the first high-risk group experienced increased rates of certain symptoms (anxiety, insomnia, and HTN). The first high-risk group had 40% and 50% decreased odds of osteoporosis and urolithiasis, respectively, but had less than a 10% decrease or increase of other disease sequelae vs patients with a diagnosis. Conversely, the second high-risk group experienced significantly decreased rates of all disease sequelae vs those with confirmed PHP (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Documented PHP was associated with significantly elevated calcium levels compared with both the first high-risk group whose PTH levels were obtained (10.90 vs 10.80 mg/dL; difference, 0.10 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.09-0.11 mg/dL; P < .001) and second high-risk group whose PTH levels were not obtained (10.90 vs 10.70 mg/dL; difference, 0.20 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.19-0.21 mg/dL; P < .001). Patients with a diagnosis also had significantly elevated PTH values vs the first high-risk group (107.00 vs 93.00 pg/mL; difference, 14.00 pg/mL; 95% CI, 12.20-15.80 pg/mL; P < .001) (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Furthermore, 1371 patients (6.8%) in high-risk group 1, 1402 patients (5.6%) in high-risk group 2, and 1199 (9.1%) of those with a confirmed diagnosis had a normal calcium level that later became elevated.

Altering PTH Cutoffs

Stratifying PTH cutoffs to 40, 50, 65, and 100 pg/mL was not associated with proportionate increases in disease sequelae for the first high-risk group as well as the group with a diagnosis. The high-risk group with stratified PTH values was compared with matched controls (eTable 5 and eTable 6 in Supplement 1), the overall group who received a diagnosis (eTable 7 and eTable 8 in Supplement 1), and the group with a diagnosis stratified by PTH levels (eTable 9 and eTable 10 in Supplement 1).

Rates of Missed Diagnoses by Region

Among the total cohort of patients with hypercalcemia (135 034 patients), 55 243 (40.9%) records were from patients who sought care in the South, 36 725 (27.2%) were in the Northeast, 25 955 (19.2%) were in the Midwest, 8737 (6.5%) were in the West, and 8374 (6.2%) were in an unknown region or outside the US. In each region, 18 114 patients (32.8%) in the South, 11 683 (31.8%) in the Northeast, 6986 (26.9%) in the Midwest, and 2477 (28.3%) in the West were considered high-risk and without a diagnosis. Compared with the South, patients in the Northeast (odds ratio [OR], 0.95; 95% CI, 0.90-1.00; P = .002), Midwest (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80; P < .001), and West (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.80-0.90; P < .001) were less likely to be high-risk and not have a diagnosis.

Association of Time to Diagnosis With Symptoms

Just 13 136 patients (9.7%) with hypercalcemia received a diagnosis of PHP (Figure). Of these individuals, 3686 (28.1%) received a diagnosis within 1 year and 9450 (71.9%) received a diagnosis after 1 year of their first instance of hypercalcemia. Patients who received a diagnosis within the first year were more likely to be symptomatic during that time; they had increased rates of osteoporosis, urolithiasis, MDD, anxiety, HTN, malaise and fatigue, constipation, weakness, abdominal pain, headache, nausea, and amnesia. However, by 2 to 3 years, those with workups exceeding 1 year had significantly increased rates of MDD, anxiety, HTN, GERD, malaise and fatigue, joint pain and myalgias, polyuria, weakness, abdominal pain, and headache (Table 3). Of note, rates of osteoporosis within this delayed group increased from 17.1% (628 patients) to 25.4% (935 patients) over the course of the study period (Table 3). The cohort who received a diagnosis within 1 year had significantly increased mean calcium (11.10 vs 10.80 mg/dL; difference, 0.30 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.28-0.32 mg/dL; P < .001) and PTH (121 vs 102 pg/mL; difference, 19 pg/mL; 95% CI, 15-23 pg/mL; P < .001) values compared with those who received a diagnosis beyond 1 year (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Table 3. Diagnoses and Symptoms in 9450 Patients Who Received a Diagnosis >1 Year vs 3686 Patients Who Received a Diagnosis ≤1 Year After Laboratory Abnormality.

| Time and diagnosis | Patients, No. (%) after matching | OR (95% CI) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis >1 y after hypercalcemia (n = 3681) | Diagnosis ≤1 y after hypercalcemia (n = 3681) | |||

| 0 to ≤1 y | ||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 628 (17.1) | 1257 (34.1) | 0.40 (0.36-0.44) | <.001 |

| Fractures | 156 (4.2) | 168 (4.6) | 0.93 (0.74-1.16) | .50 |

| Urolithiasis | 255 (6.9) | 552 (15.0) | 0.42 (0.36-0.49) | <.001 |

| MDD | 438 (11.9) | 594 (16.1) | 0.70 (0.62-0.80) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorders | 381 (10.4) | 494 (13.4) | 0.75 (0.65-0.86) | <.001 |

| HTN | 1878 (51.0) | 2065 (56.1) | 0.82 (0.74-0.89) | <.001 |

| GERD | 676 (18.4) | 767 (20.8) | 0.86 (0.76-0.96) | .008 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 463 (12.6) | 665 (18.1) | 0.65 (0.57-0.74) | <.001 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 788 (21.4) | 807 (21.9) | 0.97 (0.87-1.08) | .59 |

| Constipation | 269 (7.3) | 405 (11.0) | 0.64 (0.54-0.75) | <.001 |

| Insomnia | 168 (4.6) | 177 (4.8) | 0.95 (0.76-1.18) | .62 |

| Polyuria | 209 (5.7) | 266 (7.2) | 0.77 (0.64-0.93) | .007 |

| Weakness | 332 (9.0) | 435 (11.8) | 0.74 (0.64-0.86) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 468 (12.7) | 561 (15.2) | 0.81 (0.71-0.93) | .002 |

| Headache | 258 (7.0) | 327 (8.9) | 0.77 (0.65-0.92) | .003 |

| Nausea | 191 (5.2) | 252 (6.8) | 0.75 (0.61-0.90) | .003 |

| Amnesia | 135 (3.7) | 288 (7.8) | 0.44 (0.36-0.55) | <.001 |

| Gallstones | 81 (2.2) | 106 (2.9) | 0.76 (0.57-1.02) | .06 |

| 366 d to ≤2 y | ||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 786 (21.4) | 877 (23.8) | 0.87 (0.78-0.97) | .01 |

| Fractures | 158 (4.3) | 119 (3.2) | 1.34 (1.05-1.71) | .02 |

| Urolithiasis | 245 (6.7) | 300 (8.1) | 0.80 (0.67-0.96) | .01 |

| MDD | 452 (12.3) | 413 (11.2) | 1.11 (0.95-1.28) | .16 |

| Anxiety disorders | 382 (10.4) | 337 (9.2) | 1.15 (0.99-1.34) | .08 |

| HTN | 1944 (52.8) | 1568 (42.6) | 1.51 (1.38-1.65) | <.001 |

| GERD | 699 (19.0) | 541 (14.7) | 1.36 (1.20-1.54) | <.001 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 400 (10.9) | 345 (9.4) | 1.18 (1.01-1.37) | .03 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 754 (20.5) | 634 (17.2) | 1.24 (1.10-1.37) | <.001 |

| Constipation | 247 (6.7) | 230 (6.2) | 1.08 (0.90-1.30) | .42 |

| Insomnia | 147 (4.0) | 141 (3.8) | 1.04 (0.83-1.32) | .72 |

| Polyuria | 171 (4.6) | 171 (4.6) | 1.00 (0.81-1.24) | >.99 |

| Weakness | 269 (7.3) | 221 (6.0) | 1.23 (1.03-1.48) | .02 |

| Abdominal pain | 434 (11.8) | 376 (10.2) | 1.18 (1.02-1.36) | .03 |

| Headache | 226 (6.1) | 187 (5.1) | 1.22 (1.00-1.49) | .05 |

| Nausea | 141 (3.8) | 125 (3.4) | 1.13 (0.89-1.45) | .32 |

| Amnesia | 125 (3.4) | 154 (4.2) | 0.81 (0.63-1.02) | .08 |

| Gallstones | 56 (1.5) | 65 (1.8) | 0.86 (0.60-1.23) | .41 |

| 731 d to ≤3 y | ||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 935 (25.4) | 866 (23.5) | 1.11 (1.00-1.23) | .06 |

| Fractures | 163 (4.4) | 118 (3.2) | 1.40 (1.10-1.78) | .006 |

| Urolithiasis | 293 (8.0) | 244 (6.6) | 1.22 (1.02-1.45) | .03 |

| MDD | 479 (13.0) | 370 (10.1) | 1.34 (1.16-1.45) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorders | 436 (11.8) | 334 (9.1) | 1.35 (1.16-1.57) | <.001 |

| HTN | 1980 (53.8) | 1480 (40.2) | 1.73 (1.58-1.90) | <.001 |

| GERD | 729 (19.8) | 509 (13.8) | 1.54 (1.36-1.74) | <.001 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 443 (12.0) | 310 (8.4) | 1.49 (1.28-1.73) | <.001 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 802 (21.8) | 620 (16.8) | 1.38 (1.22-1.55) | <.001 |

| Constipation | 251 (6.8) | 199 (5.4) | 1.28 (1.06-1.55) | .01 |

| Insomnia | 180 (4.9) | 139 (3.8) | 1.31 (1.05-1.64) | .02 |

| Polyuria | 211 (5.7) | 134 (3.6) | 1.61 (1.29-2.01) | <.001 |

| Weakness | 281 (7.6) | 176 (4.8) | 1.65 (1.36-2.00) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 435 (11.8) | 294 (8.0) | 1.54 (1.32-1.80) | <.001 |

| Headache | 233 (6.3) | 172 (4.7) | 1.38 (1.13-1.69) | .002 |

| Nausea | 147 (4.0) | 120 (3.3) | 1.23 (0.97-1.58) | .09 |

| Amnesia | 151 (4.1) | 140 (3.8) | 1.08 (0.86-1.37) | .51 |

| Gallstones | 61 (1.7) | 47 (1.3) | 1.30 (0.89-1.91) | .17 |

| 1-3 y | ||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 1179 (32.0) | 1163 (31.6) | 1.02 (0.99-1.13) | .69 |

| Fractures | 253 (6.9) | 194 (5.3) | 1.33 (1.09-1.61) | .004 |

| Urolithiasis | 395 (10.7) | 397 (10.8) | 0.99 (0.86-1.15) | .94 |

| MDD | 638 (17.3) | 554 (15.1) | 1.18 (1.05-1.34) | .008 |

| Anxiety disorders | 577 (15.7) | 495 (13.4) | 1.20 (1.05-1.36) | .007 |

| HTN | 2267 (61.6) | 1814 (49.3) | 1.65 (1.50-1.81) | <.001 |

| GERD | 973 (26.4) | 743 (20.2) | 1.42 (1.27-1.58) | <.001 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 697 (18.9) | 539 (14.6) | 1.36 (1.20-1.54) | <.001 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 1168 (31.7) | 959 (26.1) | 1.32 (1.19-1.46) | <.001 |

| Constipation | 416 (11.3) | 350 (9.5) | 1.21 (1.04-1.41) | .01 |

| Insomnia | 243 (6.6) | 214 (5.8) | 1.15 (0.95-1.38) | .16 |

| Polyuria | 329 (8.9) | 269 (7.3) | 1.25 (1.05-1.47) | .01 |

| Weakness | 465 (12.6) | 341 (9.3) | 1.42 (1.22-1.64) | <.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 713 (19.4) | 552 (15.0) | 1.36 (1.21-1.54) | <.001 |

| Headache | 386 (10.5) | 301 (8.2) | 1.32 (1.12-1.54) | <.001 |

| Nausea | 256 (7.0) | 209 (5.7) | 1.24 (1.03-1.50) | .02 |

| Amnesia | 227 (6.2) | 241 (6.5) | 0.94 (0.78-1.13) | .50 |

| Gallstones | 98 (2.7) | 92 (2.5) | 1.07 (0.80-1.42) | .66 |

Abbreviations: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HTN, hypertension; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio.

Statistical significance is defined as P < .003.

Association of Time From Diagnosis to Surgery With Symptoms

Only 5280 (40.2%) of all patients with PHP diagnosed underwent parathyroidectomy (Figure). Among them, 4361 (82.6%) were treated within 1 year of diagnosis and 919 (17.4%) were treated beyond 1 year. There were 1398 patients who were then excluded from analysis because of lack of follow-up 3 years after diagnosis. Those treated within 1 year of diagnosis experienced higher rates of MDD, GERD, and constipation during that same year and had reductions in all symptoms after surgery. Conversely, delayed surgery beyond 1 year resulted in significantly increased rates of osteoporosis and HTN by 2 to 3 years after diagnosis compared with those treated within 1 year (Table 4).

Table 4. Diagnoses and Symptoms in 919 Patients Who Underwent Surgery >1 Year vs 4361 Patients Who Underwent Surgery ≤1 Year After Diagnosis of Primary Hyperparathyroidisma.

| Time and diagnosis | Patients, No. (%) after matching | OR (95% CI) | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery >1 y after diagnosis (n = 748) | Surgery ≤1 y after diagnosis (n = 748) | |||

| 0 to ≤1 y | ||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 277 (37.0) | 299 (40.0) | 0.88 (0.72-1.09) | .24 |

| Fractures | 42 (5.6) | 36 (4.8) | 1.18 (0.75-1.86) | .49 |

| Urolithiasis | 109 (14.6) | 131 (17.5) | 0.80 (0.61-1.06) | .12 |

| MDD | 103 (13.8) | 154 (20.6) | 0.62 (0.47-0.81) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorders | 80 (10.7) | 113 (15.1) | 0.67 (0.50-0.91) | .01 |

| HTN | 436 (58.3) | 471 (63.0) | 0.82 (0.67-1.01) | .06 |

| GERD | 154 (20.6) | 235 (31.4) | 0.57 (0.45-0.72) | <.001 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 112 (15.0) | 137 (18.3) | 0.79 (0.60-1.03) | .08 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 191 (25.5) | 200 (26.7) | 0.94 (0.75-1.18) | .60 |

| Constipation | 62 (8.3) | 97 (13.0) | 0.61 (0.43-0.85) | .003 |

| Insomnia | 48 (6.4) | 40 (5.3) | 1.21 (0.79-1.87) | .38 |

| Polyuria | 58 (7.8) | 54 (7.2) | 1.08 (0.74-1.59) | .69 |

| Weakness | 67 (9.0) | 74 (9.9) | 0.90 (0.63-1.27) | .54 |

| Abdominal pain | 124 (16.6) | 108 (14.4) | 1.18 (0.89-1.56) | .25 |

| Headache | 40 (5.3) | 68 (9.1) | 0.57 (0.38-0.85) | .005 |

| Nausea | 40 (5.3) | 48 (6.4) | 0.82 (0.54-1.27) | .38 |

| Amnesia | 42 (5.6) | 58 (7.8) | 0.71 (0.47-1.07) | .10 |

| Gallstones | 18 (2.4) | 21 (2.8) | 0.85 (0.45-1.62) | .63 |

| 366 d to ≤2 y | ||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 258 (34.5) | 210 (28.1) | 1.35 (1.08-1.68) | .007 |

| Fractures | 33 (4.4) | 22 (2.9) | 1.52 (0.88-2.64) | .13 |

| Urolithiasis | 90 (12.0) | 65 (8.7) | 1.44 (1.03-2.01) | .03 |

| MDD | 114 (15.2) | 104 (13.9) | 1.11 (0.84-1.48) | .46 |

| Anxiety disorders | 89 (11.9) | 75 (10.0) | 1.21 (0.88-1.68) | .25 |

| HTN | 441 (59.0) | 353 (47.2) | 1.61 (1.31-1.97) | <.001 |

| GERD | 185 (24.7) | 138 (18.4) | 1.45 (1.13-1.86) | .003 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 96 (12.8) | 75 (10.0) | 1.32 (0.96-1.82) | .09 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 175 (23.4) | 148 (19.8) | 1.24 (0.97-1.59) | .09 |

| Constipation | 69 (9.2) | 42 (5.6) | 1.71 (1.15-2.54) | .008 |

| Insomnia | 32 (4.3) | 37 (4.9) | 0.86 (0.53-1.39) | .54 |

| Polyuria | 57 (7.6) | 36 (4.8) | 1.63 (1.06-2.51) | .02 |

| Weakness | 49 (6.6) | 30 (4.0) | 1.68 (1.05-2.67) | .03 |

| Abdominal pain | 108 (14.4) | 83 (11.1) | 1.35 (1.00-1.84) | .05 |

| Headache | 53 (7.1) | 37 (4.9) | 1.47 (0.95-2.26) | .08 |

| Nausea | 42 (5.6) | 28 (3.7) | 1.53 (0.94-2.50) | .09 |

| Amnesia | 28 (3.7) | 28 (3.7) | 1.00 (0.59-1.71) | >.99 |

| Gallstones | 19 (2.5) | 14 (1.9) | 1.37 (0.68-2.75) | .38 |

| 731 d to ≤3 y | ||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 288 (38.5) | 181 (24.2) | 1.96 (1.57-2.75) | <.001 |

| Fractures | 23 (3.1) | 28 (3.7) | 0.82 (0.47-1.43) | .48 |

| Urolithiasis | 72 (9.6) | 63 (8.4) | 1.16 (0.81-1.65) | .42 |

| MDD | 106 (14.2) | 96 (12.8) | 1.12 (0.83-1.51) | .45 |

| Anxiety disorders | 88 (11.8) | 81 (10.8) | 1.10 (0.80-1.51) | .57 |

| HTN | 433 (57.9) | 361 (48.3) | 1.47 (1.20-1.81) | <.001 |

| GERD | 161 (21.5) | 148 (19.8) | 1.11 (0.87-1.43) | .41 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 92 (12.3) | 74 (9.9) | 1.28 (0.92-1.77) | .14 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 194 (25.9) | 160 (21.4) | 1.29 (1.01-1.64) | .04 |

| Constipation | 56 (7.5) | 39 (5.2) | 1.47 (0.97-2.24) | .07 |

| Insomnia | 39 (5.2) | 35 (4.7) | 1.12 (0.70-1.79) | .63 |

| Polyuria | 43 (5.7) | 44 (5.9) | 0.98 (0.63-1.51) | .91 |

| Weakness | 47 (6.3) | 32 (4.3) | 1.50 (0.95-2.38) | .08 |

| Abdominal pain | 88 (11.8) | 66 (8.8) | 1.38 (0.98-1.93) | .06 |

| Headache | 43 (5.7) | 46 (6.1) | 0.93 (0.61-1.43) | .74 |

| Nausea | 28 (3.7) | 36 (4.8) | 0.77 (0.46-1.27) | .31 |

| Amnesia | 29 (3.9) | 28 (3.7) | 1.04 (0.61-1.76) | .89 |

| Gallstones | 16 (2.1) | 16 (2.1) | 1.00 (0.50-2.02) | >.99 |

| 1-3 y | ||||

| Osteopenia or osteoporosis | 362 (48.4) | 257 (34.4) | 1.79 (1.46-2.21) | <.001 |

| Fractures | 46 (6.1) | 40 (5.3) | 1.16 (0.75-1.79) | .51 |

| Urolithiasis | 114 (15.2) | 88 (11.8) | 1.35 (1.00-1.82) | .05 |

| MDD | 149 (19.9) | 136 (18.2) | 1.12 (0.87-1.45) | .39 |

| Anxiety disorders | 130 (17.4) | 113 (15.1) | 1.18 (0.90-1.56) | .23 |

| HTN | 496 (66.3) | 407 (54.4) | 1.65 (1.34-2.03) | <.001 |

| GERD | 234 (31.3) | 191 (25.5) | 1.33 (1.06-1.66) | .01 |

| Malaise or fatigue | 155 (20.7) | 122 (16.3) | 1.34 (1.03-74) | .03 |

| Joint pain or myalgias | 280 (37.4) | 234 (31.3) | 1.31 (1.06-1.63) | .01 |

| Constipation | 104 (13.9) | 63 (8.4) | 1.76 (1.26-2.45) | <.001 |

| Insomnia | 54 (7.2) | 58 (7.8) | 0.93 (0.63-1.36) | .69 |

| Polyuria | 88 (11.8) | 67 (9.0) | 1.36 (0.97-1.90) | .07 |

| Weakness | 86 (11.5) | 55 (7.4) | 1.64 (1.15-2.33) | .006 |

| Abdominal pain | 162 (21.7) | 127 (17.0) | 1.35 (1.04-1.75) | .02 |

| Headache | 87 (11.6) | 71 (9.5) | 1.26 (0.90-1.73) | .18 |

| Nausea | 66 (8.8) | 56 (7.5) | 1.20 (0.83-1.73) | .34 |

| Amnesia | 47 (6.3) | 45 (6.0) | 1.05 (0.69-1.60) | .83 |

| Gallstones | 30 (4.0) | 23 (3.1) | 1.31 (0.76-2.29) | .33 |

Abbreviations: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HTN, hypertension; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio.

Note that 1398 patients were excluded from this analysis because they did not have follow-up 3 years after diagnosis.

Statistical significance is defined as P < .003.

Time from diagnosis to surgery within 1 year vs surgery beyond 1 year was associated with increased calcium (11.00 vs 10.90 mg/dL; difference, 0.10 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.06-0.15 mg/dL; P < .001) and PTH (135 vs 112 pg/mL; difference, 23 pg/mL; 95% CI, 12-34 pg/mL; P < .001) (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Among the 7856 patients (59.8%) who did not undergo surgery, 1169 (14.9%) were prescribed bisphosphonates, 380 (4.8%) were prescribed cinacalcet, and 177 (2.3%) were prescribed a combination for medical management. The remainder did not have documented treatment.

Discussion

The reported range of patients with hypercalcemia whose PTH levels are obtained is 23.4% to 33.0%.13,15,18,19 Approximately 43% of those with hypercalcemia have PHP.15 However, the condition is diagnosed in just 1.3% to 8.0% of patients.15,18,19 The findings of this cohort study are consistent with historical data, noting a workup including PTH for approximately 2 of 5 patients. We found that 33.3% of patients with hypercalcemia were at high risk for PHP but did not receive a diagnosis. When added to the 9.7% with a diagnosis, the actual prevalence of PHP in patients with hypercalcemia could be over 43%. Patients in the South had the greatest likelihood of being high-risk and not receiving a diagnosis. More than one-quarter may have not received a diagnosis even in the Midwest, which had the lowest rate of undetected PHP. This is indicative of a problem affecting patients throughout the US.

Prior studies13,14,15,16,17,18,19 have reported the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of PHP. Because the disease is often asymptomatic,30 whether it had a clinically meaningful impact on patients was unknown. Our study shows that patients at high risk who did not have a diagnosis experienced significantly increased disease sequelae vs matched controls. Compared with patients with a diagnosis, the high-risk group whose PTH levels were obtained had decreased rates of some, no difference in others, and increased rates of other associated symptoms and diagnoses. Differentiating these groups were patients with a diagnosis who were more likely to have classic PHP manifestations, such as osteoporosis and urolithiasis. Symptoms and diagnoses in patients whose PHP went undiagnosed likely contributed to decreased quality of life and increased use of medical services and associated costs. This is especially noteworthy, considering that parathyroidectomy is a cost-effective cure associated with substantial improvement in symptoms.9,12,31,32,33

It is unclear why patients with unexplained hypercalcemia did not undergo measurement of PTH. Although this group experienced increased rates of symptoms and diagnoses associated with PHP, their symptoms were considerably less severe compared with those with PTH measurements. It may be that they were considered to be asymptomatic and therefore did not undergo further workup. Diagnostic evaluation should not be restricted to the most symptomatic patients; therefore, this represents an opportunity for improvement. Furthermore, research indicates that patients who are labeled asymptomatic may still report symptoms when prompted or after undergoing cognitive testing.12 Our review only reported the rates of those symptoms that were coded, which likely underrepresented the true incidence of symptomatic patients. This suggests that there should be a strong suspicion for hyperparathyroidism in patients with hypercalcemia.34

A possible explanation for missed diagnoses in patients with hypercalcemia and inappropriately nonsuppressed PTH between 50 and 65 pg/mL could be they were not identified because their PTH levels were within the reference range. Patients without a diagnosis with frankly elevated PTH greater than or equal to 65 pg/mL may be explained by the fact that clinicians often attribute hypercalcemia to other causes, even in patients with elevated PTH.35

Another contributing factor for missed diagnoses may be that high-risk patients had lower calcium and PTH levels vs those whose PHP was diagnosed. Similarly, patients who experienced delayed diagnosis or time to treatment also had lower calcium and PTH compared with the timely diagnosis and treatment groups. Although greater PTH levels increased the likelihood of diagnosis and treatment, they did not correlate with disease burden in our study, a finding consistent with prior literature.36

Among patients with a PHP diagnosis, those whose workup took over a year had significantly increased rates of disease sequelae over time, as seen at 2 to 3 years after hypercalcemia. Our study found that 40.2% of patients underwent surgical management after diagnosis, which is within the reported range of 16.8% to 67.2%.15,17,18,19 Patients who waited longer than 1 year from diagnosis to surgery also had increased rates of serious complications such as osteoporosis and HTN over time. Therefore, efforts to reduce diagnostic and treatment delays are worthwhile endeavors. Raising awareness about the diagnosis of PHP is important because it will lead to the evaluation of those associated conditions that should prompt referral to surgery as per the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons guidelines.11

Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective study of US patients to date, representing 30% of the population older than 40 years, which increases the generalizability of these results.37 However, it is not without limitations. If a patient received some of their workup outside an included HCO, they may be incorrectly categorized as having had an insufficient workup. This is unlikely because the TriNetX Research Network data are obtained from large HCOs with multiple inpatient and outpatient facilities. The analysis is limited by the accuracy of data entry in the electronic medical records. Both shortcomings are minimized by filtering for patients with at least 2 documented levels of hypercalcemia and at least 3 years of follow-up, suggesting established care within an included HCO. Given the variability in calcium reference ranges by as much as 0.5 mg/dL,22 this study did not include patients with calcium levels between 10.0 to 10.5 mg/dL, which may have been flagged as elevated by some laboratories. Some patients who were excluded as having another explanation for hypercalcemia may have had concomitant undiagnosed PHP. These limitations and the strict exclusion criteria may have underestimated the true prevalence of undiagnosed PHP. Conversely, our analysis assumed that all patients considered high risk actually had PHP.

Conclusions

The findings of this cohort study suggest that many patients at high risk for PHP may not have a diagnosis and may be untreated despite experiencing associated symptoms and diagnoses. These findings were widespread across the US. Patients with prolonged time from hypercalcemia to diagnosis and diagnosis to treatment reported increased disease sequelae over time. Therefore, system-level interventions aimed at ensuring proper diagnoses and reducing duration of workup and time to treatment are necessary for improved outcomes.

eMethods. Diagnosis (ICD-10) and Procedure (CPT) Codes

eTable 1. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients in the First (Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥50 pg/mL Without a Documented Diagnosis) (n = 20,176) and Second (Unexplained Hypercalcemia and No Further Workup) (n = 24,905) High-risk Groups for PHP

eTable 2. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients Diagnosed With PHP (n = 13,136) Compared to Matched Controls

eTable 3. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in High-risk Group 1 (Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥50 pg/mL) (n = 20,176) and High-risk Group 2 (Unexplained Hypercalcemia and No Further Workup) (n = 24,905) Compared to Those Diagnosed (n = 13,136)

eTable 4. Lab Values for Patient Cohorts

eTable 5. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥40 (n = 23,969) or 50 pg/mL (n = 20,176) Without a Documented Diagnosis of PHP Compared to Matched Controls

eTable 6. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥65 (n = 14,959) or 100 (n = 7,387) pg/mL Without a Documented Diagnosis of PHP Compared to Matched Controls

eTable 7. Comparing Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥40 (n = 23,969) or 50 pg/mL (n = 20,176) Without a Documented Diagnosis With Those Diagnosed (n = 13,136)

eTable 8. Comparing Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥65 (n = 14,959) or 100 pg/mL (n = 7,387) Without a Documented Diagnosis With Those Diagnosed (n = 13,136)

eTable 9. Comparing Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥40 (n = 23,969) or 50 pg/mL (n = 20,176) Without a Documented Diagnosis With Those Diagnosed With Similar PTH Levels (n = 12,294 for PTH ≥40 and n = 11,968 for ≥50 pg/mL)

eTable 10. Comparing Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥65 (n = 14,959) or 100 pg/mL (n = 7,387) Without a Documented Diagnosis With Those Diagnosed With Similar PTH Levels (n = 11,262 for PTH ≥65 and n = 8,192 for ≥100 pg/mL)

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Bilezikian JP, Bandeira L, Khan A, Cusano NE. Hyperparathyroidism. Lancet. 2018;391(10116):168-178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31430-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padmanabhan H. Outpatient management of primary hyperparathyroidism. Am J Med. 2011;124(10):911-914. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopinath P, Mihai R. Hyperparathyroidism. Surgery. 2011;29(9):451-458. doi: 10.1016/j.mpsur.2011.06.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cordellat IM. Hyperparathyroidism: primary or secondary disease? Rheumatol Clin. 8(5):287-291. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conrad DN, Olson JE, Hartwig HM, Mack E, Chen H. A prospective evaluation of novel methods to intraoperatively distinguish parathyroid tissue utilizing a parathyroid hormone assay. J Surg Res. 2006;133(1):38-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madkhali T, Alhefdhi A, Chen H, Elfenbein D. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2016;32(1):58-66. doi: 10.5152/UCD.2015.3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger M, Dy B, McKenzie T, Thompson G, Wermers R, Lyden M. Rates of hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism among patients with porcelain gallbladder. Am J Surg. 2020;220(1):127-131. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito Y, Takami H, Abdelhamid Ahmed AH, et al. Association of symptomatic gallstones and primary hyperparathyroidism: a propensity score-matched analysis. Br J Surg. 2021;108(10):e336-e337. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dulfer R, Geilvoet W, Morks A, et al. Impact of parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism on quality of life: a case-control study using Short Form Health Survey 36. Head Neck. 2016;38(8):1213-1220. doi: 10.1002/hed.24499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher SB, Perrier ND. Primary hyperparathyroidism and hypertension. Gland Surg. 2020;9(1):142-149. doi: 10.21037/gs.2019.10.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilhelm SM, Wang TS, Ruan DT, et al. The American Association of Endocrine Surgeons guidelines for definitive management of primary hyperparathyroidism. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(10):959-968. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah-Becker S, Derr J, Oberman BS, et al. Early neurocognitive improvements following parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(3):775-780. doi: 10.1002/lary.26617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quilao RJ, Greer M, Stack BC Jr. Investigating the potential underdiagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(4):773-777. doi: 10.1002/lio2.415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enell J, Bayadsi H, Lundgren E, Hennings J. Primary hyperparathyroidism is underdiagnosed and suboptimally treated in the clinical setting. World J Surg. 2018;42(9):2825-2834. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4574-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Press DM, Siperstein AE, Berber E, et al. The prevalence of undiagnosed and unrecognized primary hyperparathyroidism: a population-based analysis from the electronic medical record. Surgery. 2013;154(6):1232-1237. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dombrowsky A, Borg B, Xie R, Kirklin JK, Chen H, Balentine CJ. Why is hyperparathyroidism underdiagnosed and undertreated in older adults? Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. 2018;11:1179551418815916. doi: 10.1177/1179551418815916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapey IM, Jaunoo SS, Hanson C, Jaunoo SR, Thrush S, Munro A. Primary hyperparathyroidism: how many cases are being missed? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(4):294-296. doi: 10.1308/003588411X13020175704352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balentine CJ, Xie R, Kirklin JK, Chen H. Failure to diagnose hyperparathyroidism in 10,432 patients with hypercalcemia: opportunities for system-level intervention to increase surgical referrals and cure. Ann Surg. 2017;266(4):632-640. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alore EA, Suliburk JW, Ramsey DJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary hyperparathyroidism across the Veterans Affairs health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(9):1220-1227. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.TriNetX Analytics Network . Accessed November 16, 2022. https://trinetx.com

- 21.Portale A. Blood calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium. In: Favus M, ed. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. 4th ed. Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 1999:115-118. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein D. Serum calcium. Chapter 143. In: Walker KH, Hall WD, Hurst JW, ed. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Butterworths; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shane E. Etiology of hypercalcemia. UptoDate. 2021. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-of-hypercalcemia

- 24.Horwitz M. Hypercalcemia of malignancy: mechanisms. UptoDate. 2020. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hypercalcemia-of-malignancy-mechanisms

- 25.Cusano NE, Bilezikian JP. Parathyroid hormone in the evaluation of hypercalcemia. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2680-2681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant FD, Conlin PR, Brown EM. Rate and concentration dependence of parathyroid hormone dynamics during stepwise changes in serum ionized calcium in normal humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71(2):370-378. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-2-370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rejnmark L, Amstrup AK, Mollerup CL, Heickendorff L, Mosekilde L. Further insights into the pathogenesis of primary hyperparathyroidism: a nested case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):87-96. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowley R, Gittoes N. How to approach hypercalcaemia. Clin Med (Lond). 2013;13(3):287-290. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.13-3-287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vakiti A, Mewawalla P. Malignancy-related hypercalcemia. January 2022. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29494030

- 30.Silverberg SJ, Walker MD, Bilezikian JP. Asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Densitom. 2013;16(1):14-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zanocco K, Heller M, Sturgeon C. Cost-effectiveness of parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(suppl 1):69-74. doi: 10.4158/EP10311.RA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burney RE, Jones KR, Christy B, Thompson NW. Health status improvement after surgical correction of primary hyperparathyroidism in patients with high and low preoperative calcium levels. Surgery. 1999;125(6):608-614. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(99)70224-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gopinath P, Sadler GP, Mihai R. Persistent symptomatic improvement in the majority of patients undergoing parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395(7):941-946. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0689-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renaghan AD, Rosner MH. Hypercalcemia: etiology and management. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(4):549-551. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asban A, Dombrowsky A, Mallick R, et al. Failure to diagnose and treat hyperparathyroidism among patients with hypercalcemia: opportunities for intervention at the patient and physician level to increase surgical referral. Oncologist. 2019;24(9):e828-e834. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bargren AE, Repplinger D, Chen H, Sippel RS. Can biochemical abnormalities predict symptomatology in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism? J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(3):410-414. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.06.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.US Census Bureau . Age and sex composition in the United States: 2019. October 8, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2019/demo/age-and-sex/2019-age-sex-composition.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Diagnosis (ICD-10) and Procedure (CPT) Codes

eTable 1. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients in the First (Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥50 pg/mL Without a Documented Diagnosis) (n = 20,176) and Second (Unexplained Hypercalcemia and No Further Workup) (n = 24,905) High-risk Groups for PHP

eTable 2. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients Diagnosed With PHP (n = 13,136) Compared to Matched Controls

eTable 3. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in High-risk Group 1 (Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥50 pg/mL) (n = 20,176) and High-risk Group 2 (Unexplained Hypercalcemia and No Further Workup) (n = 24,905) Compared to Those Diagnosed (n = 13,136)

eTable 4. Lab Values for Patient Cohorts

eTable 5. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥40 (n = 23,969) or 50 pg/mL (n = 20,176) Without a Documented Diagnosis of PHP Compared to Matched Controls

eTable 6. Associated Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥65 (n = 14,959) or 100 (n = 7,387) pg/mL Without a Documented Diagnosis of PHP Compared to Matched Controls

eTable 7. Comparing Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥40 (n = 23,969) or 50 pg/mL (n = 20,176) Without a Documented Diagnosis With Those Diagnosed (n = 13,136)

eTable 8. Comparing Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥65 (n = 14,959) or 100 pg/mL (n = 7,387) Without a Documented Diagnosis With Those Diagnosed (n = 13,136)

eTable 9. Comparing Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥40 (n = 23,969) or 50 pg/mL (n = 20,176) Without a Documented Diagnosis With Those Diagnosed With Similar PTH Levels (n = 12,294 for PTH ≥40 and n = 11,968 for ≥50 pg/mL)

eTable 10. Comparing Diagnoses and Symptoms in Patients at High Risk of PHP With Hypercalcemia and PTH ≥65 (n = 14,959) or 100 pg/mL (n = 7,387) Without a Documented Diagnosis With Those Diagnosed With Similar PTH Levels (n = 11,262 for PTH ≥65 and n = 8,192 for ≥100 pg/mL)

Data Sharing Statement