Abstract

This study quantifies the revenue earned on all brand-name inhalers approved by the US Food and Drug Administration from 2000 to 2021 and compared earnings before and after expiration of primary patents on these products.

Inhalers remain the cornerstone therapy for patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Over the past several decades, brand-name manufacturers have continued to sell most inhalers at high prices without the threat of direct generic competition. They have arranged for long periods of market exclusivity by obtaining patents not just on the active ingredients (primary patents) but also on peripheral aspects of these products, such as the propellants and delivery devices (secondary patents), and by shifting active ingredients to different devices (device hops), thereby adding new secondary patents.1,2

Delays in generic competition have reduced patient access and led to unnecessary health care spending.2,3 To better understand the financial value of patents to inhaler manufacturers, we quantified the revenue earned on all brand-name prescription inhalers approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from 2000 to 2021 and compared earnings before and after expiration of primary patents on these products.

Methods

We identified patents on FDA-approved inhalers for the treatment of asthma and COPD using the FDA’s Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (Orange Book) (eMethods in the Supplement). We extracted the claims of each patent from Google Patents to determine whether patents covered the active ingredients or other aspects of the product in question. Data on sales revenue (net of rebates) earned in the US were obtained from 10-K filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission and company annual reports.

Individual products with the same active ingredients marketed by a single manufacturer were classified as the same inhaler line. Because manufacturers reported aggregated revenue on inhaler lines such as Advair (fluticasone and salmeterol) rather than providing a breakdown for Advair Diskus and Advair HFA, we focused on inhaler lines as the primary unit of analysis. Within each inhaler line, we recorded the number of device hops. In years when data on US revenue were missing, imputations were performed (eMethods in the Supplement).

The main analysis compared the revenue earned when the primary patents were active vs the revenue earned after the primary patents expired. In a sensitivity analysis, we quantified revenue on products with only active secondary patents that were free from generic competition (eMethods in the Supplement). Revenue was adjusted for inflation to 2021 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers. Analyses were performed in Excel version 16 (Microsoft).

Results

The FDA approved 39 brand-name inhalers across 32 inhaler lines from 2000 to 2021 (Table). These products were linked to 18 primary patents and 239 secondary patents. Revenue data were available for 21 inhaler lines, which represented more than 90% of the US market based on a prior analysis of Medicare Part D spending.4

Table. Expiration of Key Patents on Inhalers Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, 2000-2021.

| Inhaler line | Active ingredients | No.a | Regulatory events | Revenue earned, $, in billions (%)b | Total revenue, $, in billions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First approved | Primary patents expire | Secondary patents expire | Active primary patents | Active secondary patents | All patents expired | ||||

| Inhaled corticosteroid | |||||||||

| Qvar | Beclomethasone | 2 | Sep 15, 2000 | Preapproval | Jan 25, 2039 | 0 | 4.0 (100) | 0 | 4.0 |

| Pulmicort | Budesonide | 1 | Jul 12, 2006 | Preapproval | May 8, 2018 | 0 | 10.9 (97.3) | 0.3 (2.7) | 11.2 |

| Alvesco | Ciclesonide | 1 | Jan 10, 2008 | Jan 9, 2013 | Feb 1, 2028 | 0.1 (20) | 0.4 (80) | 0 | 0.5 |

| Aerospan | Flunisolide | 1 | Jan 27, 2006 | Preapproval | Jul 7, 2015 | ||||

| ArmonAirc | Fluticasone | 1 | Jan 27, 2017 | Preapproval | Aug 16, 2036 | ||||

| Arnuityc | Fluticasone | 1 | Aug 20, 2014 | Aug 3, 2021 | Oct 11, 2030 | 0.3 (100) | <0.1 | 0 | 0.3 |

| Floventc | Fluticasone | 2 | Sep 29, 2000 | May 14, 2004 | Aug 26, 2026 | 3.9 (25.2) | 11.6 (74.8) | 0 | 15.5 |

| Asmanex | Mometasone | 2 | Mar 30, 2005 | Preapproval | Mar 17, 2018 | ||||

| Long-acting β-agonist | |||||||||

| Foradil | Formoterol | 2 | Feb 16, 2001 | Preapproval | Nov 28, 2020 | 0 | 0.3 (100) | 0 | 0.3 |

| Arcapta | Indacaterol | 1 | Jul 1, 2011 | Feb 25, 2025 | Oct 11, 2028 | ||||

| Striverdi | Olodaterol | 1 | Jul 31, 2014 | May 12, 2025 | Oct 16, 2030 | ||||

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonist | |||||||||

| Tudorza | Aclidinium | 1 | Jul 23, 2012 | Feb 10, 2025 | Mar 13, 2029 | 0.5 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| Seebri | Glycopyrrolate | 1 | Oct 29, 2015 | Preapproval | Oct 20, 2028 | ||||

| Spiriva | Tiotropium | 2 | Jan 30, 2004 | Jul 30, 2018 | Apr 16, 2031 | 25.7 (84.5) | 4.7 (15.5) | 0 | 30.5 |

| Incruse | Umeclidinium | 1 | Apr 30, 2014 | Dec 18, 2027 | Oct 11, 2030 | 1.3 (100) | 0 | 0 | 1.3 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β-agonist | |||||||||

| Symbicort | Budesonide and formoterol | 1 | Jul 21, 2006 | Preapproval | Oct 7, 2029 | 0 | 15.6 (100) | 0 | 15.6 |

| Advairc | Fluticasone and salmeterol | 2 | Aug 24, 2000 | Aug 12, 2008 | Aug 26, 2026 | 26.1 (38.3) | 42.1 (61.7) | 0 | 68.2 |

| AirDuoc | Fluticasone and salmeterol | 1 | Jan 27, 2017 | Preapproval | Aug 16, 2036 | ||||

| Breoc | Fluticasone and vilanterol | 1 | May 10, 2013 | May 21, 2025 | Oct 11, 2030 | 4.3 (100) | 0 | 0 | 4.3 |

| Dulera | Mometasone and formoterol | 1 | Jun 22, 2010 | Preapproval | Nov 21, 2020 | 0 | 3.1 (93.9) | 0.2 (6.1) | 3.3 |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonist and long-acting β-agonist | |||||||||

| Duaklir | Aclidinium and formoterol | 1 | Mar 29, 2019 | Feb 10, 2025 | Mar 13, 2029 | <0.1 (100) | 0 | 0 | <0.1 |

| Bevespi | Glycopyrrolate and formoterol | 1 | Apr 25, 2016 | Preapproval | Mar 17, 2031 | 0 | 0.2 (100) | 0 | 0.2 |

| Utibron | Glycopyrrolate and indacaterol | 1 | Oct 29, 2015 | Feb 25, 2025 | Oct 20, 2028 | ||||

| Stiolto | Tiotropium and olodaterol | 1 | May 21, 2015 | May 12, 2025 | Oct 16, 2030 | ||||

| Anoro | Umeclidinium and vilanterol | 1 | Dec 18, 2013 | Dec 18, 2027 | Nov 29, 2030 | 2.4 (100) | 0 | 0 | 2.4 |

| Inhaled corticosteroid, long-acting muscarinic antagonist, and long-acting β-agonist | |||||||||

| Breztri | Budesonide, glycopyrrolate, and formoterol | 1 | Jul 23, 2020 | Preapproval | Mar 17, 2031 | 0 | 0.1 (100) | 0 | 0.1 |

| Trelegyc | Fluticasone, umeclidinium, and vilanterol | 1 | Sep 18, 2017 | Dec 18, 2027 | Nov 29, 2030 | 2.6 (100) | 0 | 0 | 2.6 |

| Short-acting β-agonist | |||||||||

| ProAir | Albuterol | 2 | Oct 29, 2004 | Preapproval | Aug 16, 2036 | 0 | 7.7 (100) | 0 | 7.7 |

| Ventolin | Albuterol | 1 | Apr 19, 2001 | Preapproval | Aug 26, 2026 | 0 | 7.3 (98.6) | 0.1 (1.4) | 7.4 |

| Xopenex | Levalbuterol | 1 | Mar 11, 2005 | Preapproval | Oct 8, 2024 | 0 | 2.4 (100) | 0 | 2.4 |

| Short-acting muscarinic antagonist | |||||||||

| Atrovent | Ipratropium | 1 | Nov 17, 2004 | Preapproval | Jan 17, 2030 | ||||

| Short-acting muscarinic antagonist and short-acting β-agonist | |||||||||

| Combivent | Ipratropium and albuterol | 1 | Oct 7, 2011 | Preapproval | Oct 16, 2030 | ||||

The number of products per inhaler line. Inhalers with different strengths or device types under the same New Drug Application were considered a single product.

Some of the revenue during the study period was generated on products that were approved in the inhaler line before 2000, including products with ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) that were phased out by the US Food and Drug Administration beginning in 2009. The 5 inhaler lines in the cohort with 1 or more products approved before 2000 were Flovent (a CFC-containing version was approved in 1996; Flovent Rotadisk was approved in 1997), Ventolin (a CFC-containing version was approved in 1981; Ventolin Rotahaler was approved in 1988), Pulmicort (Pulmicort Turbuhaler was approved in 1997), Atrovent (a CFC-containing version was approved in 1986), and Combivent (a CFC-containing version was approved in 1996). Inhaler lines with only products approved before 2000 were excluded from the analysis.

Advair, AirDuo, ArmonAir, and Flovent contain fluticasone propionate and Arnuity, Breo, and Trelegy contain the longer-acting fluticasone furoate.

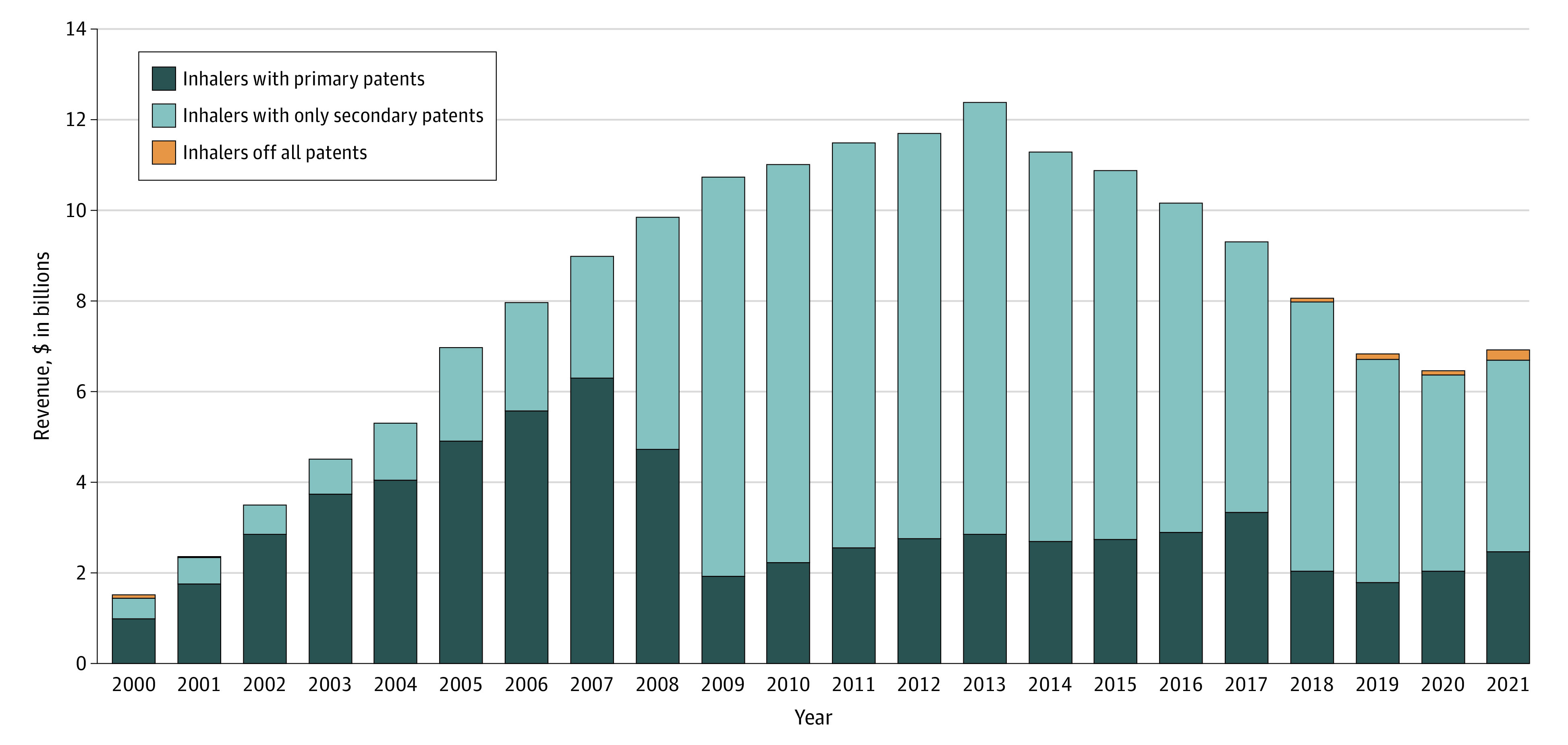

Manufacturers earned $178.1 billion on inhalers during the study period: $67.2 billion (38%) when primary patents were active, $110.3 billion (62%) after primary patents had expired but when secondary patents were active, and $613 million (<1%) after all patents had expired (Figure). Advair (fluticasone and salmeterol) had the highest revenue at $68.2 billion (38% earned before primary patent expiration and 62% after) followed by Spiriva (tiotropium) at $30.5 billion (85% earned before primary patent expiration and 15% after). Ninety-eight percent of the $110.3 billion earned by manufacturers on inhaler lines that were protected exclusively by secondary patents accrued during periods when these products faced no generic competition.

Figure. Revenue Earned in the US on Brand-Name Inhaler Lines Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, 2000-2021.

Manufacturers earned $67.2 billion in revenue on inhaler lines when primary patents were active (depicted in dark blue), $110.3 billion on inhaler lines when only secondary patents were active (light blue), and $613 million in revenue after inhalers had gone off patent (orange). Of the data points, 20% (53/264) (representing 14% of total revenue) were imputed and 3% (8/264) were missing (eMethods in the Supplement). Some of the revenue was earned on inhalers that had been approved before the start of the study period but were marketed from 2000 to 2021. Three inhaler lines (Pulmicort, Ventolin, and Xopenex) had corresponding nebulizer suspensions or solutions that were sold in the US; revenue from these products were included. Teva and Sunovion reported data on North American sales rather than US sales alone (their revenue accounted for 8% of total inhaler revenue).

Discussion

Manufacturers of brand-name inhalers listed many more secondary patents than primary patents with the FDA from 2000 to 2021 and earned substantially more revenue on inhalers after active ingredients went off patent compared with revenue generated when the primary patents remained active. Amounts of revenue earned before primary patent expiration varied in part because of the timing of drug approval. The analysis was limited by missing revenue data on a subset of inhalers, although these inhalers represented a small fraction of the overall market.

The current patent and regulatory system rewards minor changes to the delivery systems of existing molecules, diverting incentives for investments in new therapeutic breakthroughs.2 Regulators and lawmakers have begun to scrutinize patenting practices relating to drug-device combinations.5,6 Without substantial reform, patients and payers may continue spending large sums on inhaled products with active ingredients developed decades ago.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editor.

eMethods

References

- 1.Beall RF, Kesselheim AS. Tertiary patenting on drug-device combination products in the United States. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(2):142-145. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman WB, Bloomfield D, Beall RF, Kesselheim AS. Patents and regulatory exclusivities on inhalers for asthma and COPD, 1986-2020. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(6):787-796. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel B, Mayne P, Patri T, et al. Out-of-pocket costs and prescription filling behavior of commercially insured individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(5):e221167. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman WB, Gagne JJ, Kesselheim AS. Trends in Medicare Part D inhaler spending: 2012-2018. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(3):548-550. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202008-1082RL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orange Book Transparency Act of 2020, HR 1503, 116th Cong, Pub L 116-290. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1503/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22H.+R.+1503%22%5D%7D&r=1&s=1

- 6.US Patent and Trademark Office . USPTO-FDA collaboration initiatives. Accessed December 3, 2022. https://www.uspto.gov/initiatives/fda-collaboration

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods