Key Points

Question

Is procrastination associated with subsequent health outcomes among university students?

Findings

In this cohort study of 3525 Swedish university students, procrastination was associated with worse subsequent mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress symptom levels), having disabling pain in the upper extremities, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (poor sleep quality and physical inactivity), and worse levels of psychosocial health factors (higher loneliness and more economic difficulties).

Meaning

This study suggests that procrastination may be associated with a range of health outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Procrastination is prevalent among university students and is hypothesized to lead to adverse health outcomes. Previous cross-sectional research suggests that procrastination is associated with mental and physical health outcomes, but longitudinal evidence is currently scarce.

Objective

To evaluate the association between procrastination and subsequent health outcomes among university students in Sweden.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study was based on the Sustainable University Life study, conducted between August 19, 2019, and December 15, 2021, in which university students recruited from 8 universities in the greater Stockholm area and Örebro were followed up at 5 time points over 1 year. The present study used data on 3525 students from 3 time points to assess whether procrastination was associated with worse health outcomes 9 months later.

Exposure

Self-reported procrastination, measured using 5 items from the Swedish version of the Pure Procrastination Scale rated on a Likert scale from 1 (“very rarely or does not represent me”) to 5 (“very often or always represents me”) and summed to give a total procrastination score ranging from 5 to 25.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Sixteen self-reported health outcomes were assessed at the 9-month follow-up. These included mental health problems (symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress), disabling pain (neck and/or upper back, lower back, upper extremities, and lower extremities), unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (poor sleep quality, physical inactivity, tobacco use, cannabis use, alcohol use, and breakfast skipping), psychosocial health factors (loneliness and economic difficulties), and general health.

Results

The study included 3525 participants (2229 women [63%]; mean [SD] age, 24.8 [6.2] years), with a follow-up rate of 73% (n = 2587) 9 months later. The mean (SD) procrastination score at baseline was 12.9 (5.4). An increase of 1 SD in procrastination was associated with higher mean symptom levels of depression (β, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09-0.17), anxiety (β, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.04-0.12), and stress (β, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.08-0.15), and having disabling pain in the upper extremities (risk ratio [RR], 1.27; 95% CI, 1.14-1.42), poor sleep quality (RR, 1.09, 95% CI, 1.05-1.14), physical inactivity (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.11), loneliness (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.12), and economic difficulties (RR, 1.15, 95% CI, 1.02-1.30) at the 9-month follow-up, after controlling for a large set of potential confounders.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study of Swedish university students suggests that procrastination is associated with subsequent mental health problems, disabling pain, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, and worse psychosocial health factors. Considering that procrastination is prevalent among university students, these findings may be of importance to enhance the understanding of students’ health.

This cohort study evaluates the association between procrastination and subsequent health outcomes among university students in Sweden.

Introduction

Procrastination is defined as voluntarily delaying an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off because of the delay1 and is common, especially among younger people.2,3 It is estimated that at least half of university students engage in consistent and problematic procrastination, such as postponing studying for examinations or writing papers.1,4 Procrastination is described as a form of self-regulatory failure linked to personality traits such as impulsiveness,5,6 distractibility, and low conscientiousness.1,7 An individual’s tendency to procrastinate is relatively stable over time, but specific procrastination behaviors are influenced by contextual factors such as task aversiveness.1 For some students, procrastination is occasional and related to specific academic tasks, while for others it is more of a general disposition, potentially affecting academic achievements8 and health.

Cross-sectional studies suggest that procrastination is associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress as well as loneliness and reduced life satisfaction.2,9,10,11 Procrastination is also associated with prevalent general physical health problems,12 cardiovascular disease,13 and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors.12,14,15

Students engaged in university studies have high levels of freedom and low structure, which places high demands on their capacity to self-regulate.16 These high demands on self-regulation may explain the high prevalence of procrastination among university students and make persons who are prone to procrastinate more vulnerable to the negative consequences of procrastination while at the university.16

The procrastination health model12,17 suggests that a general tendency to procrastinate is associated with negative health outcomes by increasing levels of stress, reducing healthy behaviors, and delaying treatment.12,17,18 However, the causal direction between procrastination and health outcomes is not well understood and could be bidirectional, with poor physical or mental health reducing energy levels and motivation, potentially leading to more procrastination.

Some of the strongest support for the causal claims of the procrastination health model comes from studies on the effects of treating procrastination. Results from randomized clinical trials suggest that intervening on procrastination with psychological treatments can reduce subsequent levels of depression and anxiety and improve quality of life.19 However, the evidence is limited as there are only a few studies, with a focus solely on mental health outcomes.19

The procrastination health model provides a useful theoretical foundation for how procrastination could affect different health outcomes.12,17 However, longitudinal evidence from studies of procrastination and subsequent health outcomes is scant and focuses on only 1 or a few health outcomes.20,21,22,23 Furthermore, most studies have limited control for important confounders, including other health problems, age, and sociodemographic factors. Also, no study has, to our knowledge, controlled for the potential reverse causation that may arise if health problems increase procrastination.

In this study, we investigated the associations between procrastination and a range of subsequent health outcomes while controlling for a large set of potential confounders, including prior levels of the outcomes. This method allows for stronger conclusions regarding the causal direction24 between procrastination and health outcomes and can provide a broader picture of the potential associations between procrastination and health.

We aimed to evaluate the associations between procrastination and 16 health outcomes at the end of a 9-month period. The outcomes include mental health, disabling pain, and several unhealthy lifestyle behaviors and psychosocial health factors. Following the procrastination health model,12,17 we hypothesized that higher levels of procrastination would be associated with worse health outcomes at follow-up.

Methods

Design and Study Population

The cohort for this study came from the Sustainable University Life study,25 which followed up Swedish university students for 1 year using web-based surveys. Undergraduate or graduate students (up to and including masters’ level) at full-time educational programs, with at least 1 year left of their education were eligible to participate. Students were recruited from 8 universities in the greater Stockholm area and Örebro. Data collection was ongoing from August 19, 2019, to December 15, 2021. The targeted universities represent a convenience sample and were selected to provide a variety of different types of disciplines, such as medicine, technology, social sciences, and economics and were restricted to universities in a limited geographical area to enable physical presence by study staff. The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority and all participants provided informed consent electronically. More information about the study methods and data collection is available in the study protocol.25 This study is reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

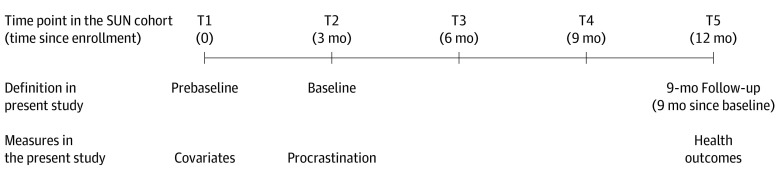

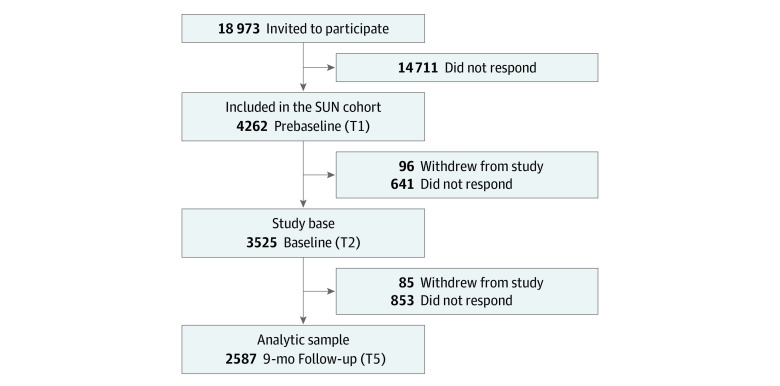

Eligible students were informed about the study during an in-class presentation and/or by an email with a link to the survey. Students who agreed to participate were followed up every 3 months for 1 year at 5 time points. In the present data analysis, the first time point was defined as prebaseline and was used for measures of the covariates. The second time point was defined as the baseline and was used for the procrastination measure and the fifth time point was defined as the 9-month follow-up and used for measurement of the health outcomes (Figure 1). The follow-up period of 9 months represents the length of an academic year, which we believe is adequate for procrastination to manifest its potential associations with different health outcomes. The sample was restricted to those responding at baseline and included 3525 participants; the follow-up rate was 73% (n = 2587) at the 9-month follow-up (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Timeline of Data Collection in the Sustainable University Life (SUN) Cohort and How Data Were Organized for the Present Study.

T indicates time point.

Figure 2. Flowchart of the Inclusion of Participants.

The definition of each time point (T) in the present study (T1, T2, and T5) refers to the time point in the Sustainable University Life (SUN) Cohort (Figure 1). Note that T3 and T4 are not shown here, because data from these time points were not used for the main analyses.

Measures

Exposure: Procrastination

Procrastination was measured using 5 items from the Swedish version of the Pure Procrastination Scale (PPS).26 The items were rated on a Likert scale from 1 (“very rarely or does not represent me”) to 5 (“very often or always represents me”) and summed to give a total procrastination score ranging from 5 to 25. The short version of the PPS includes items 4 through 8 from the full PPS and has shown adequate psychometric properties in nonclinical samples.26,27 In this sample, the scale had a Cronbach α of 0.92 at baseline and a test-retest reliability (Pearson r) of 0.79 over 3 months and of 0.75 over 9 months.

Outcomes

We assessed a range of health outcomes at the 9-month follow-up, including mental health problems (symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress), disabling pain (neck and/or upper back, lower back, upper extremities, and lower extremities), unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (poor sleep quality, physical inactivity, weekly tobacco use, monthly cannabis use, daily alcohol use, and breakfast skipping), psychosocial health factors (loneliness and economic difficulties), and general health. For more information on the outcome measures, see eMethods 1 in Supplement 1.

Confounders

Potential confounders were selected using the modified disjunctive cause criterion.28 This approach is a feasible alternative to directed acyclic graphs when the causal knowledge needed to produce a reliable directed acyclic graph is unavailable.28 We used the same set of covariates in all the outcome models, as has been suggested for outcome-wide studies.29 The covariate set included all outcome variables at prebaseline to limit the risk of reverse causation,30 as well as age, gender, highest parental level of education, previous physical and psychiatric diagnoses, civil status, place of birth, and university education type. All covariates were measured at prebaseline to ensure that none were mediators between procrastination and the outcomes. Information on covariate measurement and coding is provided in eMethods 1 in Supplement 1.

Statistical Analysis

The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1, both for the full sample and across quartiles of procrastination (procrastination score range, 5-25; first quartile, 5-9; second quartile, 10-12; third quartile, 13-17; and fourth quartile, 18-25). To assess whether procrastination was associated with the health outcomes at follow-up, we used the outcome-wide approach,29 a newly developed analytic approach to study associations between an exposure and multiple outcomes. We built separate multivariable regression models for each of the outcomes to assess the association between baseline procrastination and the different outcomes at the 9-month follow-up. For continuous outcomes, linear regression models were used. For binary outcomes, modified Poisson regressions31 were used (rather than logistic regression models because some outcomes were relatively common).

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants Prebaseline for the Full Sample and by Quartiles of Procrastination Levelsa.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample (N = 3525) | Procrastination quartileb | ||||

| First (n = 1052) | Second (n = 713) | Third (n = 1003) | Fouth (n = 757) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 24.8 (6.2) | 25.3 (6.7) | 24.8 (6.3) | 24.7 (6.2) | 24.0 (5.5) |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 2229 (63) | 674 (64) | 458 (64) | 640 (64) | 457 (60) |

| Male | 1274 (36) | NRc | NRc | NRc | NRc |

| Other | 22 (1) | NRc | NRc | NRc | NRc |

| Education type | |||||

| Medical or health | 1688 (48) | 556 (53) | 343 (48) | 471 (47) | 318 (42) |

| Technical | 1407 (40) | 354 (34) | 274 (38) | 413 (41) | 366 (48) |

| Social science or humanities | 294 (8) | 100 (10) | 68 (10) | 79 (8) | 47 (6) |

| Economic | 85 (2) | 28 (3) | 16 (2) | 28 (3) | 13 (2) |

| Other | 51 (1) | 14 (1) | 12 (2) | 12 (1) | 13 (2) |

| Civil status | |||||

| Single | 1975 (56) | 494 (47) | 395 (55) | 594 (59) | 492 (65) |

| Cohabiting partner | 1133 (32) | 435 (41) | 227 (32) | 294 (29) | 177 (23) |

| Noncohabiting partner | 417 (12) | 123 (12) | 91 (13) | 115 (11) | 88 (12) |

| Place of birth | |||||

| Sweden | 2826 (80) | 859 (82) | 579 (81) | 797 (79) | 591 (78) |

| Other Nordic countries | 118 (3) | 38 (4) | 23 (3) | 31 (3) | 26 (3) |

| Other Europe | 192 (5) | 57 (5) | 41 (6) | 61 (6) | 33 (4) |

| Outside Europe | 389 (11) | 98 (9) | 70 (10) | 114 (11) | 107 (14) |

| Highest parental educational level | |||||

| University | 2553 (72) | 747 (71) | 513 (72) | 737 (73) | 556 (73) |

| Less than university | 972 (28) | 305 (29) | 200 (28) | 266 (27) | 201 (27) |

| Previous diagnoses, mean (SD), No.d | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.9 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.4) |

| Mental health score, mean (SD) | |||||

| Depression symptoms | 4.7 (4.7) | 2.9 (3.6) | 4.1 (4.2) | 5.0 (4.4) | 7.3 (5.4) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 3.0 (3.3) | 2.1 (2.9) | 2.7 (3.1) | 3.2 (3.2) | 4.2 (4) |

| Stress symptoms | 6.3 (4.6) | 5.0 (4.3) | 6.0 (4.3) | 6.7 (4.4) | 7.9 (4.8) |

| Disabling pain | |||||

| Neck and/or upper back | 405 (11) | 90 (9) | 84 (12) | 117 (12) | 114 (15) |

| Lower back | 364 (10) | 86 (8) | 62 (9) | 117 (12) | 99 (13) |

| Upper extremities | 436 (12) | 90 (9) | 98 (14) | 137 (14) | 111 (15) |

| Lower extremities | 545 (15) | 123 (12) | 106 (15) | 162 (16) | 154 (20) |

| Lifestyle behaviors | |||||

| Poor sleep quality | 1893 (54) | 380 (36) | 351 (49) | 605 (60) | 557 (74) |

| Physically inactive | 1831 (52) | 438 (42) | 364 (51) | 548 (55) | 481 (64) |

| Daily alcohol use | 51 (1) | 7 (1) | 17 (2) | 12 (1) | 15 (2) |

| Weekly tobacco use | 542 (15) | 136 (13) | 130 (18) | 141 (14) | 135 (18) |

| Monthly cannabis use | 72 (2) | 12 (1) | 17 (2) | 16 (2) | 27 (4) |

| Breakfast skipping | 878 (25) | 188 (18) | 160 (22) | 246 (25) | 284 (38) |

| Psychosocial health factors | |||||

| Loneliness | 1485 (42) | 273 (26) | 275 (39) | 477 (48) | 460 (61) |

| Economic difficulties | 555 (16) | 110 (10) | 110 (15) | 172 (17) | 163 (22) |

| Poor general health | 113 (3) | 14 (1) | 11 (2) | 34 (3) | 54 (7) |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

Procrastination was measured at baseline, while all covariates and outcomes were measured prebaseline. Percentages of some categorical variables do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

The procrastination score ranged from 5 to 25, with the quartiles 9 (25th percentile), 12 (50th percentile), and 17 (75th percentile). Participants were categorized based on their procrastination score as follows: 5 to 9, first quartile; 10 to 12, second quartile; 13 to 17, third quartile; and 18 to 25, fourth quartile.

The gender categories “male” and “other” are not presented for procrastination quartiles because the “other” category had low cell counts (<5). The gender category “other” included participants responding “Other” or “Do not want to identify with either of these identities.”

The previous diagnoses variable is a count indicating how many of the following diagnoses the participants had received: rheumatic diseases; allergies; respiratory diseases; cardiovascular diseases; gastrointestinal diseases; diabetes; diseases in urinary tracts or internal or external genitals; diseases in the nervous system, eyes, or ears; mental disorders; tumors or cancers; and attention deficits or learning disabilities.

Procrastination and all continuous outcome measures were standardized (mean = 0, SD = 1). Estimates for continuous outcomes are thus interpreted as the difference in the outcome as measured in SDs associated with a 1-SD increase in procrastination, and estimates for the binary outcomes are interpreted as the risk ratio (RR) of the outcome associated with a 1-SD increase in procrastination. All models were adjusted for the set of prebaseline confounders described. For unadjusted estimates, see eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Visual inspection of the residuals from all models indicated fairly linear associations between procrastination and the outcomes. The homoscedasticity and distribution of the residuals were not assessed because they typically have minor impact on the regression estimates,32 but the modified Poisson models still applies robust SEs. This analytic strategy deviates from the ones prespecified in our study protocol25 but was selected as it was deemed most appropriate for the research questions. Analyses were conducted using R, version 4.1.2 (R Group for Statistical Computing).

Missing Data

Outcome data were missing for 938 participants not responding at the 9-month follow-up, and the main analyses were performed as complete-case analyses (n = 2587). Prebaseline characteristics stratified by missingness at the 9-month follow-up are presented in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. We had complete data on the exposure and all covariates, except for the sleep quality variable. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) had missing data on 3 items for sleep disturbances for 9% (n = 225) of the respondents in the analytic sample due to a technical error at the beginning of data collection. These missing data were handled by imputing the person-mean of the items for sleep disturbances.

Sensitivity Analyses

First, we computed the E-value33,34 that assesses how strongly unmeasured and residual confounding would need to be associated with the exposure and the outcomes on the RR scale to reduce the point estimates to the null. When the 95% CIs did not include the null, we also computed the E-value of the 95% CI bound closest to the null, to assess the strength of unmeasured and residual confounding needed to shift the 95% CI to include the null. Second, we calculated the point-biserial correlation between procrastination at baseline and missingness at follow-up to investigate the possibility of selection bias in relation to the internal validity. No association between the exposure and loss to follow-up indicates that selection bias cannot affect the internal validity, but only the external validity.35 Third, we conducted analyses controlling for prior levels of procrastination, as has been suggested for outcome-wide studies.29 These analyses had to be performed with a 6-month follow-up because we did not have data on procrastination at prebaseline (eMethods 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Fourth, the robustness of our results to the person-mean imputation of values on the PSQI was assessed by performing multiple imputation for the 3 missing items (eMethods 3 in Supplement 1).

Results

At prebaseline, the study included 3525 participants (2229 women [63%] and 1274 men (36%); mean [SD] age, 24.8 [6.2] years) (Table 1). The mean (SD) procrastination score at baseline was 12.9 (5.4). Gender and age were similar across levels of procrastination, but participants with higher levels of procrastination tended to be more likely to study technical sciences, be single, and have been born outside of Europe. All outcome variables showed higher prevalence or mean levels at prebaseline among participants with higher procrastination levels at baseline.

Table 2 presents the results from the outcome regression models. At the 9-month follow-up, a 1-SD increase in procrastination was associated with higher mean symptom levels of depression (β, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09-0.17), anxiety (β, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.04-0.12), and stress (β, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.08-0.15) as well as having disabling pain in the upper extremities (RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.14-1.42), poor sleep quality (RR, 1.09, 95% CI, 1.05-1.14), physical inactivity (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.04-1.11), loneliness (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.12), and economic difficulties (RR, 1.15, 95% CI, 1.02-1.30). The results showed no clear evidence of associations between procrastination and subsequent disabling pain in other body regions; use of tobacco, alcohol, or cannabis, breakfast skipping; or general health afer adjustment for the prebaseline covariates.

Table 2. Procrastination and Subsequent Health Outcomesa.

| Outcome | β or RR (95% CI) | E-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE | LCL | ||

| Mental health, β (95% CI) | |||

| Depression symptoms | 0.13 (0.09-0.17) | 1.57 | 1.45 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 0.08 (0.04-0.12) | 1.41 | 1.27 |

| Stress symptoms | 0.11 (0.08-0.15) | 1.53 | 1.41 |

| Disabling pain, RR (95% CI) | |||

| Neck and/or upper back | 1.09 (0.96-1.24) | 1.41 | NA |

| Lower back | 1.03 (0.90-1.18) | 1.22 | NA |

| Upper extremities | 1.27 (1.14-1.42) | 1.86 | 1.53 |

| Lower extremities | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.23) | 1.44 | NA |

| Lifestyle behaviors, RR (95% CI) | |||

| Poor sleep quality | 1.09 (1.05-1.14) | 1.41 | 1.27 |

| Physical inactivity | 1.07 (1.04-1.11) | 1.35 | 1.24 |

| Daily alcohol use | 1.05 (0.71-1.56) | 1.29 | NA |

| Weekly tobacco use | 0.96 (0.89-1.04) | 1.24 | NA |

| Monthly cannabis use | 1.21 (0.91-1.62) | 1.71 | NA |

| Breakfast skipping | 1.03 (0.97-1.09) | 1.19 | NA |

| Psychosocial health factors, RR (95% CI) | |||

| Loneliness | 1.07 (1.02-1.12) | 1.35 | 1.17 |

| Economic difficulties | 1.15 (1.02-1.30) | 1.57 | 1.17 |

| Poor general health | 1.14 (0.97-1.34) | 1.54 | NA |

Abbreviations: LCL, lower confidence limit; NA, not applicable; PE, point estimate; RR, relative risk.

All models were adjusted for the set of prebaseline covariates described, including all outcomes prebaseline. Procrastination and all continuous outcomes were standardized (mean = 0 and SD = 1), and β is the standardized effect size.

For estimates with a 95% CI that excluded the null, the E-values suggested that unmeasured confounders would need to increase the risk of both procrastination and the outcomes by 35% to 86%, depending on the outcome, to move the point estimates to the null (Table 2). The point-biserial correlation between procrastination at baseline and missingness at the follow-up was 0.05. Outcome levels at prebaseline were generally somewhat higher in the group that was missing at the 9-month follow-up (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The associations between procrastination and health outcomes 6 months later, while controlling for prior procrastination levels, were similar to the results in the main analysis (eMethods 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Using multiple imputation for the 3 missing items on the PSQI gave results identical to the main analysis when rounded to the second decimal place (eMethods 3 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this cohort of Swedish university students, higher levels of procrastination were associated with worse subsequent mental health (depression, anxiety, and stress symptom levels), having disabling pain in the upper extremities, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (poor sleep quality and physical inactivity), and worse levels of psychosocial health factors (higher loneliness and more economic difficulties) 9 months later. We found no clear associations between procrastination and subsequent disabling pain in other body regions (neck and/or upper back, lower back, or lower extremities), other unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (alcohol, tobacco, or cannabis use and breakfast skipping), or general health.

The identified associations are in the same direction, but to a lesser magnitude, than those reported in most previous studies on procrastination and health outcomes.1,2,9,10,12 There are several potential reasons for this difference in magnitude, such as the use of different scales to measure procrastination and the health outcomes. However, the arguably largest difference between this study and most previous studies is that we controlled for an extensive set of potential confounders. To our knowledge, this is the first study of procrastination and health outcomes to adjust for prior levels of the outcomes. As shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 1, when controlling for prior levels of the outcome variables, the unadjusted estimates of associations between procrastination and the health outcomes corresponded more closely to those of some previous studies.2,9,10 By adjusting for prebaseline levels of the outcome variables, we reduced the risk of reverse causality.30 Still, interpreting these association as causal effects requires the assumptions of no unmeasured or residual confounding, selection bias, or other biases affecting the associations,36 assumptions that are unlikely to be fully met in the present study. We do believe, however, that our results may correspond more closely to the consequences that interventions targeting procrastination would have for different health outcomes, than those of earlier cross-sectional studies.

Our estimates indicate that the associations between procrastination and subsequent health outcomes are weak. For instance, a 1-SD increase in procrastination was associated with a mean increase in subsequent depression symptoms of only 0.13 SDs, and many of the associations were weaker than this. The follow-up time of 9 months represents 1 academic year and was chosen because we believe this is sufficient induction time for procrastination to lead to health problems. It is possible, however, that these estimates would be stronger for a longer follow-up because the potential negative associations of procrastination with health outcomes could accumulate over time. Still, even though the associations are not very strong, it seems that procrastination could have associations with many different aspects of health, including mental health, physical pain, lifestyle behaviors, and psychosocial health factors. Thus, although it seems that intervening on procrastination is unlikely to produce large associations with any specific health outcome, it could possibly produce small associations with a diverse set of different health outcomes.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The E-value analysis suggests that unmeasured and residual confounding (from, for instance, neuroticism, conscientiousness, or genetic factors) could potentially explain away the observed associations. This potential unmeasured or residual confounding would, however, need to be moderately associated with procrastination and the outcomes, independent of all measured covariates29 (ie, associated with procrastination and the outcomes even after adjusting for all covariates). Given the large number of confounders adjusted for in these analyses, it is likely that a substantial proportion of any unmeasured confounding is already accounted for in our analyses. Controlling for prior procrastination levels gave results similar to those in the main analysis, limiting the risk of reverse causality and unmeasured confounding29 (eMethods 2 and eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

We also have the risk of misclassification of exposure and outcomes, which is probably not an issue for the procrastination measure given that the PPS showed excellent reliability. The outcomes, however, differ somewhat in their psychometric properties, and misclassification may have attenuated the observed associations for some of the outcomes.

We found that procrastination at baseline had a near-null association with loss to follow-up, so it is unlikely that the internal validity of observed associations is subject to selection bias.35 There were, however, small differences in prebaseline characteristics, especially prior outcome levels, between responders and nonresponders, which could affect external validity (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). Furthermore, the sample is not fully representative of the overall Swedish student population (for instance, we have more medical and health and technical students than average). Thus, it is uncertain whether our estimates are generalizable to Swedish students overall or to other populations. Furthermore, our measures were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, which could affect generalizability to other time periods.

Conclusions

This cohort study of Swedish university students suggests that procrastination is associated with subsequent mental health problems, disabling pain, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, and worse psychosocial health factors. Considering that procrastination is prevalent among university students, these findings may be of importance to enhace the understanding of students’ health.

eMethods 1. Assessment of the Outcome and Confounder Variables

eTable 1. Comparisons of Estimates Under Different Adjustments

eTable 2. Characteristics of Participants at Pre-baseline Stratified by Missingness at the Nine-Month Follow-up

eMethods 2. Sensitivity Analysis Controlling for Prior Levels of Procrastination

eTable 3. Procrastination (T3) and Subsequent Health Outcomes Six Months Later (T5), Adjusted for Prior Levels of Procrastination (T2)

eMethods 3. Sensitivity Analysis for the Imputation of the Three Missing Items on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Steel P. The nature of procrastination: a meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(1):65-94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beutel ME, Klein EM, Aufenanger S, et al. Procrastination, distress and life satisfaction across the age range—a German representative community study. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steel P, Ferrari J. Sex, education and procrastination: an epidemiological study of procrastinators’ characteristics from a global sample. Eur J Pers. 2013;27(1):51-58. doi: 10.1002/per.1851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day V, Mensink D, O’Sullivan M. Patterns of academic procrastination. J Coll Read Learn. 2000;30(2):120-134. doi: 10.1080/10790195.2000.10850090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gustavson DE, Miyake A, Hewitt JK, Friedman NP. Genetic relations among procrastination, impulsivity, and goal-management ability: implications for the evolutionary origin of procrastination. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(6):1178-1188. doi: 10.1177/0956797614526260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loehlin JC, Martin NG. The genetic correlation between procrastination and impulsivity. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2014;17(6):512-515. doi: 10.1017/thg.2014.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steel P, Svartdal F, Thundiyil T, Brothen T. Examining procrastination across multiple goal stages: a longitudinal study of temporal motivation theory. Front Psychol. 2018;9:327. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KR, Seo EH. The relationship between procrastination and academic performance: a meta-analysis. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;82:26-33. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernie BA, Bharucha Z, Nikčević AV, Marino C, Spada MM. A metacognitive model of procrastination. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:196-203. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirois FM. Procrastination and stress: exploring the role of self-compassion. Self Ident. 2014;13(2):128-145. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2013.763404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rozental A, Forsström D, Hussoon A, Klingsieck KB. Procrastination among university students: differentiating severe cases in need of support from less severe cases. Front Psychol. 2022;13:783570. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.783570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirois FM. “I’ll look after my health, later”: a replication and extension of the procrastination–health model with community-dwelling adults. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43(1):15-26. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sirois FM. Is procrastination a vulnerability factor for hypertension and cardiovascular disease? testing an extension of the procrastination-health model. J Behav Med. 2015;38(3):578-589. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9629-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroese FM, Evers C, Adriaanse MA, de Ridder DTD. Bedtime procrastination: a self-regulation perspective on sleep insufficiency in the general population. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(5):853-862. doi: 10.1177/1359105314540014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroese FM, de Ridder DT. Health behaviour procrastination: a novel reasoned route towards self-regulatory failure. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(3):313-325. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1116019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svartdal F, Dahl TI, Gamst-Klaussen T, Koppenborg M, Klingsieck KB. How study environments foster academic procrastination: overview and recommendations. Front Psychol. 2020;11:540910. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.540910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sirois F, Melia-Gordon M, Pychyl T. “I’ll look after my health, later”: an investigation of procrastination and health. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;35:1167-1184. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00326-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stead R, Shanahan MJ, Neufeld RWJ. “I’ll go to therapy, eventually”: procrastination, stress and mental health. Pers Individ Dif. 2010;49(3):175-180. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozental A, Bennett S, Forsström D, et al. Targeting procrastination using psychological treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1588. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui G, Yin Y, Li S, et al. Longitudinal relationships among problematic mobile phone use, bedtime procrastination, sleep quality and depressive symptoms in Chinese college students: a cross-lagged panel analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):449. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03451-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice KG, Richardson CM, Clark D. Perfectionism, procrastination, and psychological distress. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(2):288-302. doi: 10.1037/a0026643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sternberg N, Luria R, Chandhok S, Vickers B, Kross E, Sheppes G. When Facebook and finals collide—procrastinatory social media usage predicts enhanced anxiety. Comput Human Behav. 2020;109:106358. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tice DM, Baumeister RF. Longitudinal study of procrastination, performance, stress, and health: the costs and benefits of dawdling. Psychological Sci. 1997;8:454-458. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00460.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanderWeele TJ. Can sophisticated study designs with regression analyses of observational data provide causal inferences? JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(3):244-246. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edlund K, Sundberg T, Johansson F, et al. Sustainable UNiversity Life (SUN) study: protocol for a prospective cohort study of modifiable risk and prognostic factors for mental health problems and musculoskeletal pain among university students. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e056489. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozental A, Forsell E, Svensson A, Forsström D, Andersson G, Carlbring P. Psychometric evaluation of the Swedish version of the Pure Procrastination Scale, the Irrational Procrastination Scale, and the Susceptibility to Temptation Scale in a clinical population. BMC Psychol. 2014;2(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s40359-014-0054-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svartdal F, Steel P. Irrational delay revisited: examining five procrastination scales in a global sample. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1927. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VanderWeele TJ. Principles of confounder selection. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(3):211-219. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanderWeele TJ, Mathur MB, Chen Y. Outcome-wide longitudinal designs for causal inference: a new template for empirical studies. Stat Sci. 2020;35(3):437-466, 430. doi: 10.1214/19-STS728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.VanderWeele TJ, Jackson JW, Li S. Causal inference and longitudinal data: a case study of religion and mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1457-1466. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1281-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelman A, Hill J, Vehtari A. Regression and Other Stories. Cambridge University Press; 2020. doi: 10.1017/9781139161879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268-274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haneuse S, VanderWeele TJ, Arterburn D. Using the E-value to assess the potential effect of unmeasured confounding in observational studies. JAMA. 2019;321(6):602-603. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernán MA. Invited commentary: selection bias without colliders. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(11):1048-1050. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernan MA, Robins JM. Causal Inference: What If. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Assessment of the Outcome and Confounder Variables

eTable 1. Comparisons of Estimates Under Different Adjustments

eTable 2. Characteristics of Participants at Pre-baseline Stratified by Missingness at the Nine-Month Follow-up

eMethods 2. Sensitivity Analysis Controlling for Prior Levels of Procrastination

eTable 3. Procrastination (T3) and Subsequent Health Outcomes Six Months Later (T5), Adjusted for Prior Levels of Procrastination (T2)

eMethods 3. Sensitivity Analysis for the Imputation of the Three Missing Items on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement