This genetic association study examines polygenic risk scores (PRS) for schizophrenia and groups with different liabilities to schizophrenia spectrum disorders to detect associations between PRS and the likelihood of receiving a prescription of clozapine relative to other antipsychotics.

Key Points

Question

Are polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia (PRS-SCZ) associated with a psychosis liability spectrum and a clinician’s decision to prescribe clozapine?

Findings

In this genetic association study with 2344 participants from 2 cohorts, we found that PRS-SCZ loading was highest among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders taking clozapine, followed by those taking other antipsychotics, their relatives, and unrelated healthy controls. In addition, PRS-SCZ was positively associated with a clozapine prescription relative to other antipsychotics.

Meaning

While in this study PRS-SCZ loading increased with greater psychosis liability, in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and a relatively high PRS-SCZ, clozapine is more likely to be prescribed.

Abstract

Importance

Predictors consistently associated with psychosis liability and course of illness in schizophrenia (SCZ) spectrum disorders (SSD), including the need for clozapine treatment, are lacking. Longitudinally ascertained medication use may empower studies examining associations between polygenic risk scores (PRSs) and pharmacotherapy choices.

Objective

To examine associations between PRS-SCZ loading and groups with different liabilities to SSD (individuals with SSD taking clozapine, individuals with SSD taking other antipsychotics, their parents and siblings, and unrelated healthy controls) and between PRS-SCZ and the likelihood of receiving a prescription of clozapine relative to other antipsychotics.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This genetic association study was a multicenter, observational cohort study with 6 years of follow-up. Included were individuals diagnosed with SSD who were taking clozapine or other antipsychotics, their parents and siblings, and unrelated healthy controls. Data were collected from 2004 until 2021 and analyzed between October 2021 and September 2022.

Exposures

Polygenic risk scores for SCZ.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Multinomial logistic regression was used to examine possible differences between groups by computing risk ratios (RRs), ie, ratios of the probability of pertaining to a particular group divided by the probability of healthy control status. We also computed PRS-informed odd ratios (ORs) for clozapine use relative to other antipsychotics.

Results

Polygenic risk scores for SCZ were generated for 2344 participants (mean [SD] age, 36.95 years [14.38]; 994 female individuals [42.4%]) who remained after quality control screening (557 individuals with SSD taking clozapine, 350 individuals with SSD taking other antipsychotics during the 6-year follow-up, 542 parents and 574 siblings of individuals with SSD, and 321 unrelated healthy controls). All RRs were significantly different from 1; RRs were highest for individuals with SSD taking clozapine (RR, 3.24; 95% CI, 2.76-3.81; P = 2.47 × 10−46), followed by individuals with SSD taking other antipsychotics (RR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.95-2.72; P = 3.77 × 10−22), parents (RR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.25-1.68; P = 1.76 × 10−6), and siblings (RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.21-1.63; P = 8.22 × 10−6). Polygenic risk scores for SCZ were positively associated with clozapine vs other antipsychotic use (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.22-1.63; P = 2.98 × 10−6), suggesting a higher likelihood of clozapine prescriptions among individuals with higher PRS-SCZ.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, PRS-SCZ loading differed between groups of individuals with SSD, their relatives, and unrelated healthy controls, with patients taking clozapine at the far end of PRS-SCZ loading. Additionally, PRS-SCZ was associated with a higher likelihood of clozapine prescribing. Our findings may inform early intervention and prognostic studies of the value of using PRS-SCZ to personalize antipsychotic treatment.

Introduction

Genetic factors are estimated to explain 60% to 80% of the liability to schizophrenia (SCZ). To date, 270 common risk loci contributing to SCZ have been identified,1 highlighting the polygenic nature of SCZ. To summarize the aggregate risk that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) may confer, polygenic risk score (PRS) analysis was developed.2,3

In bipolar disorder, PRS studies have evinced how polygenic liability is associated with lithium response and symptom severity,4,5 showing promise for the use of PRSs to stratify patients and stage disorders. However, conflicting PRS findings are reported for disease severity and treatments in SCZ,6,7 such as clozapine, a medication generally reserved for patients unresponsive to 2 or more trials of antipsychotic drugs.8

Here, by ascertaining the use of clozapine and other antipsychotics in relatively sizable, largely longitudinal, and well-characterized cohorts, we aimed to overcome some of the limitations of previous studies examining associations between PRS-SCZ and antipsychotic treatment choices. In addition, to deepen the understanding of possible differences in PRS-SCZ loading across a psychosis liability spectrum, we explored PRS-SCZ loading across individuals with SSD taking clozapine, those taking other antipsychotics during the 6-year follow-up, their relatives, and unrelated healthy controls.

Methods

Data were collected from 2004 until 2021 and analyzed between October 2021 and September 2022. Ethical approval for all studies was obtained from the applicable institutional review boards in each country. The study was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants from the longitudinal Genetic Risk and Outcome in Psychosis (GROUP) cohort9 were in 1 of the following 5 groups: individuals with SSD taking clozapine (n = 186, defined as clozapine use at ≥1 of the 3 time points during follow-up; with additional participants from the cross-sectional Clozapine International Consortium [CLOZIN] cohort, n = 687),10 individuals with SSD for whom only antipsychotics other than clozapine had been recorded at 3 time points during the 6-year follow-up (n = 524), their siblings (n = 731) and parents (n = 695), and unrelated healthy controls (n = 369). GROUP and CLOZIN (3192 participants in total) are observational cohorts conceived to elucidate genetic determinants of SSD (eMethods in Supplement 1).

Genotyping, genotype- and participant-level quality control, genotype imputation, PRS procedures, and computation of explained variances are based on previously described methods (eMethods, eTables 1 and 2, and eFigure 1 in Supplement 1).9,10 Polygenic risk scores for SCZ were derived from a European-ancestry study1 and generated by applying a bayesian framework method that uses continuous shrinkage (cs) on SNP effect sizes. PRS-cs-auto is robust to varying genetic architectures, provides substantial computational advantages, and enables multivariate modeling of local linkage disequilibrium patterns (eTable 3 and eMethods in Supplement 1).11

We used multinomial logistic regression (using the multinom function in the nnet R package)12,13 to assess possible differences in mean PRS-SCZ across the 5 groups: individuals with SSD taking clozapine, individuals with SSD taking other antipsychotics, their siblings, their parents, and unrelated healthy controls. Risk ratios (RRs) were defined as ratios of the probability of pertaining to 1 of 4 groups divided by the probability of being an unrelated healthy control.12

We then examined associations between PRS-SCZ and clozapine prescribing decisions by using logistic regression models of PRS-SCZ on medication status (clozapine vs other antipsychotics). We also grouped individuals into PRS quintiles and estimated odds ratios (ORs) by logistic regression for SCZ case-control status (unrelated healthy controls vs clozapine users and vs other antipsychotic users), as well as medication status in each quintile relative to the lowest risk quintile. Sensitivity analyses accounting for possible influences of covariates and PRS methodology were conducted to verify the robustness of our findings (eMethods in Supplement 1). Precision estimates are given using 95% CI. The statistical significance threshold was Bonferroni corrected (multinomial regression: P < .05/12 = .004; regular logistic regression: P < .05/3 = .017).

Results

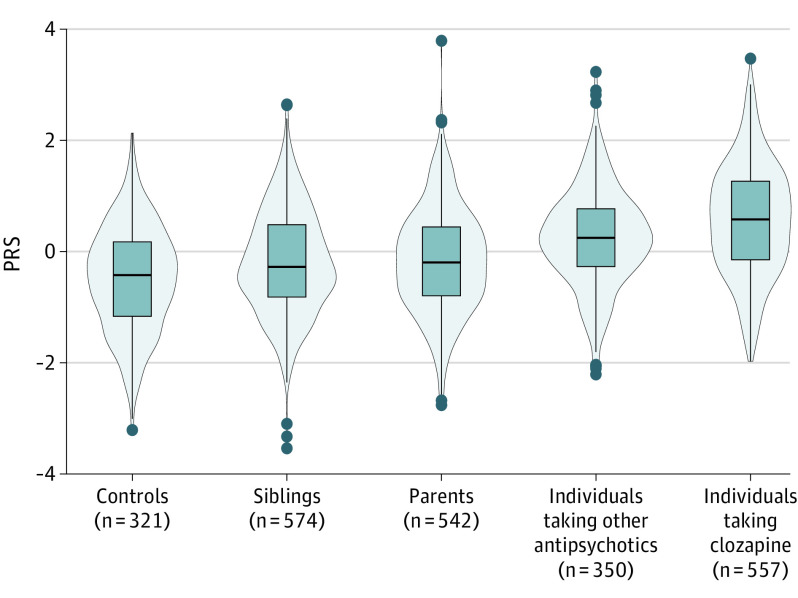

Polygenic risk scores for SCZ were generated for the 2344 participants (mean [SD] age, 36.95 years [14.38]; 994 female individuals [42.4%]) remaining after quality control (Figure 1; eTables 3 and 4 in Supplement 1). All RRs were significantly different from 1 (Figure 1; eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Risk ratios were highest in individuals with SSD taking clozapine (RR, 3.24; 95% CI, 2.76-3.81; P = 2.47 × 10−46), followed by those taking other antipsychotics (RR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.95-2.72; P = 3.77 × 10−22), parents (RR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.25-1.68; P = 1.76 × 10−6), and siblings (RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.21-1.63; P = 8.22 × 10−6).

Figure 1. Scaled Distributions of Polygenic Risk Scores for Schizophrenia (PRS-SCZ).

Individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who were taking clozapine had the highest PRS-SCZ, followed by individuals taking other antipsychotics, parents, siblings, and controls. All differences were statistically significant (t test P < .001), except for the parents-siblings comparison (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). PRS-SCZ was z scored in all samples and visualized per group. The mean PRS-SCZ is 0; hence, PRS values for controls are lower than 0. The bar in the middle of the box plot is the median PRS-SCZ for individuals in each group. The box plot rectangle is delimited by the 25th and 75th percentiles. The widths of the violins reflect the data distributions; the dots represent outliers outside the interval (Q1 − 1.5 × IQR; Q3 + 1.5 × IQR, where Q indicates quartile).

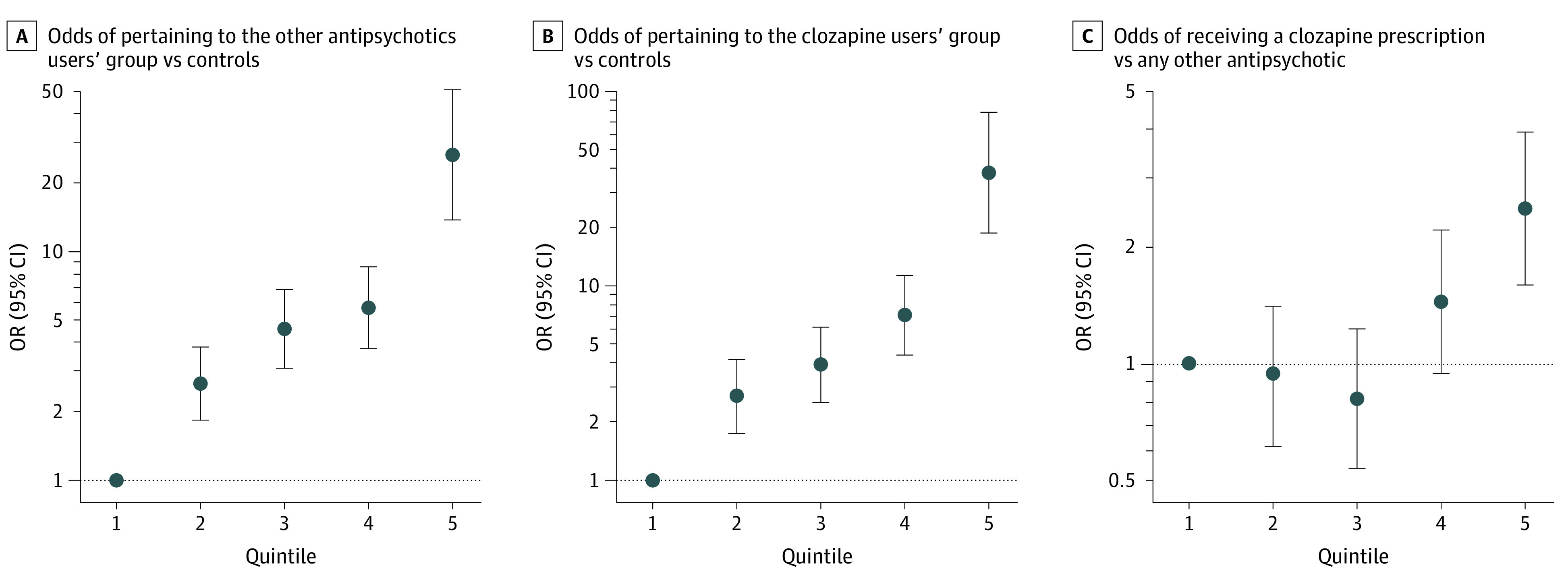

In addition, PRS-SCZ was positively associated with clozapine use (OR for clozapine vs other antipsychotic use, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.22-1.63; P = 2.98 × 10−6) (Table). Odds ratios increased with greater numbers of SCZ risk alleles in each group, reaching the maximum OR for the fifth quintile when comparing individuals taking clozapine with unrelated healthy controls (OR, 38.21; 95% CI, 18.96-78.11) (Figure 2A and B).

Table. Odds of Antipsychotic Prescriptions and Explained Variances Based on PRS-SCZ in Individuals With SSD.

| Model | Case (No. of individuals) | Control (No. of individuals) | R2 observed, 50:50a | OR (95% CI) | P value of logistic regression OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clozapine (557) | Other antipsychotics (350) | 2.59 | 1.41 (1.22-1.63) | 2.98 × 10−6 |

| 2 | Clozapine (557) | Controls (321) | 22.05 | 2.99 (2.51-3.57) | 3.57 × 10−34 |

| 3 | Other antipsychotics (350) | Controls (321) | 13.99 | 2.45 (2.02-2.98) | 1.82 × 10−19 |

| 4 | Any antipsychotic (907) | Controls (321) | 18.45 | 2.75 (2.35-3.22) | 3.49 × 10−36 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; PRS, polygenic risk score; SCZ, schizophrenia; SSD, schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Variance explained on the observed scale R2 with 50:50 ascertainment. When transforming variance explained in SSD-control status (model 4; 18.45%) to the liability scale (with an approximate prevalence of SSD = 0.01), an explained variance of 13.78% is found, which is in line with previous findings.1 (The eMethods section in Supplement 1 contains details.)

Figure 2. Odds Ratios by Polygenic Risk Profile.

Odds ratios (ORs) increased with greater number of schizophrenia risk alleles in each group, with maximums reached in the fifth quintiles for individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who were taking other antipsychotics relative to controls (panel A: OR, 26.41; 95% CI, 13.72-50.84), for clozapine users relative to controls (panel B: OR, 38.21; 95% CI, 18.96-78.11), and for clozapine users relative to users of other antipsychotics (panel C: OR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.80-3.93). Odds ratios are shown in a log scale on the y-axis by genetic risk score profile; note the change in scale on each y-axis. Polygenic risk scores were divided into quintiles (1 = lowest, 5 = highest), and 4 dummy variables were created to contrast quintiles 2 through 5 to quintile 1 as reference. Odds ratios and 95% CIs were estimated using logistic regression.

Furthermore, compared with those in the first PRS-SCZ quintile, individuals in the fifth PRS quintile had the highest odds of receiving a clozapine prescription relative to another antipsychotic (OR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.80-3.93) (Figure 2C). Finally, results of all sensitivity analyses aligned with all aforementioned findings (eResults, eTables 5 and 6, and eFigures 2, 3, 4, and 5 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing PRS-SCZ across a 5-group psychosis liability spectrum. By applying a range of analyses, we consistently demonstrate that individuals taking clozapine have the highest PRS-SCZ loading, followed by individuals using other antipsychotics, their relatives, and unrelated healthy controls. Moreover, PRS-SCZ was positively associated with the likelihood of receiving a prescription of clozapine vs another antipsychotic.

Clinical psychiatry decision-making is informed by a range of features; for example, episode severity and recurrence rates may guide relapse prevention efforts. Although in our study the variance explained by PRS in medication status (clozapine or other antipsychotics) was modest (2.6%), implications of our findings include the potential of combining clinical features with PRSs to stratify individuals with first-episode psychosis. Thus, estimates of likelihoods to determine individuals’ future need of clozapine use could one day become more precise. Future studies may establish how integrating clinical features with PRSs may allow for personalized interventions (eAppendix in Supplement 1).

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the 6-year follow-up, the sample size for a genetic study with pharmacotherapeutic data, and the diversity of analyses all pointing to similar strengths and directions of associations. Limitations include the lack of symptom-level data, daily functioning, and relapse data longitudinally, as well as a lack of additional groups of patients (eg, individuals with first-episode psychosis) from multiple ancestries. Future work should include such data to assess whether PRS-SCZ improves prediction models of clozapine prescription probability relative to clinical features alone and to allow for further comparisons between a wider range of SCZ groups. Second, although antipsychotic use in the GROUP cohort was assessed at 3 time points during a 6-year follow-up period, we cannot rule out that these individuals were prescribed clozapine later in life. On a similar note, medication use in the GROUP cohort was verified for the 6 months predating cohort entry. However, because all GROUP participants reported 2 or fewer lifetime psychotic episodes at study entry, and clozapine guidelines stipulating that clozapine be considered after 2 or more failed antipsychotic trials are strictly followed in the Netherlands, it is highly unlikely that individuals had been taking clozapine before cohort entry. Additionally, our approach is conservative as such possible former clozapine users and late-in-life clozapine users were currently classified as using other antipsychotics.

Conclusions

In this study, PRS-SCZ loading differed between groups of individuals with SSD, their relatives, and unrelated healthy controls, with patients taking clozapine at the far end of PRS-SCZ loading. In addition, PRS-SCZ was associated with a higher likelihood of clozapine prescribing. Our findings add to a growing body of evidence showing that PRS loading varies across mental illness categories within the same diagnostic spectrum. Moreover, the results described here illustrate how individuals who are prescribed an advanced-step treatment modality may be at the far extreme of PRS-SCZ loading relative to other liability groups. The association between PRS-SCZ and clozapine prescription we uncovered sets the stage for projects probing the utility of PRSs in personalizing treatment for individuals with SSD.

eMethods

eResults

eAppendix. Discussion of future directions

eReferences

eTable 1. Summary of SNP QC steps for genetic data

eTable 2. 20 Complex-LD regions and long-range LD regions which were excluded from PRS analysis

eTable 3. Demographics, characteristics, and data processing of the 5 groups that were compared

eTable 4. Age and sex of the study population after QC per each of the 5 groups

eTable 5. Multinomial logistic regression results (relative to unrelated healthy controls)

eTable 6. Logistic regression results of PRS-SCZ differences between groups

eTable 7. Group comparisons of polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia (PRS-SCZ)

eFigure 1. Individuals’ first two genetic ancestry principal components after all PCA-based exclusions of genetic outliers

eFigure 2. Mean adjusted (residualized) PRS-cs-auto-SCZ per group

eFigure 3. Mean PRSice per group

eFigure 4. Odds ratio by adjusted (residualized) PRS-cs-auto risk score profile

eFigure 5. Odds ratio by PRS-ice risk score profile

Nonauthor collaborators

References

- 1.Trubetskoy V, Pardiñas AF, Qi T, et al. ; Indonesia Schizophrenia Consortium; PsychENCODE; Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium; SynGO Consortium; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature. 2022;604(7906):502-508. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04434-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, et al. ; International Schizophrenia Consortium . Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460(7256):748-752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ni G, Zeng J, Revez JA, et al. ; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . A comparison of ten polygenic score methods for psychiatric disorders applied across multiple cohorts. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;90(9):611-620. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amare AT, Schubert KO, Hou L, et al. ; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . Association of polygenic score for major depression with response to lithium in patients with bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(6):2457-2470. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0689-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman JRI, Gaspar HA, Bryois J, Breen G; Bipolar Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium . The genetics of the mood disorder spectrum: genome-wide association analyses of more than 185,000 cases and 439,000 controls. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;88(2):169-184. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pardiñas AF, Smart SE, Willcocks IR, et al. ; Genetics Workstream of the Schizophrenia Treatment Resistance and Therapeutic Advances (STRATA) Consortium and the Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) . Interaction testing and polygenic risk scoring to estimate the association of common genetic variants with treatment resistance in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(3):260-269. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wimberley T, Gasse C, Meier SM, Agerbo E, MacCabe JH, Horsdal HT. Polygenic risk score for schizophrenia and treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(5):1064-1069. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rey Souto D, Pinzón Espinosa J, Vieta E, Benabarre Hernández A. Clozapine in patients with schizoaffective disorder: a systematic review. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Engl Ed). 2021;14(3):148-156. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pazoki R, Lin BD, van Eijk KR, et al. ; GROUP Investigators . Phenome-wide and genome-wide analyses of quality of life in schizophrenia. BJPsych Open. 2020;7(1):e13. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okhuijsen-Pfeifer C, van der Horst MZ, Bousman CA, et al. ; GROUP (Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis) investigators . Genome-wide association analyses of symptom severity among clozapine-treated patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):145. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-01884-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge T, Chen CY, Ni Y, Feng YA, Smoller JW. Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1776. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09718-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Florio A, Mei Kay Yang J, Crawford K, et al. Post-partum psychosis and its association with bipolar disorder in the UK: a case-control study using polygenic risk scores. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(12):1045-1052. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00253-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 4th ed. Springer; 2002. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-21706-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eResults

eAppendix. Discussion of future directions

eReferences

eTable 1. Summary of SNP QC steps for genetic data

eTable 2. 20 Complex-LD regions and long-range LD regions which were excluded from PRS analysis

eTable 3. Demographics, characteristics, and data processing of the 5 groups that were compared

eTable 4. Age and sex of the study population after QC per each of the 5 groups

eTable 5. Multinomial logistic regression results (relative to unrelated healthy controls)

eTable 6. Logistic regression results of PRS-SCZ differences between groups

eTable 7. Group comparisons of polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia (PRS-SCZ)

eFigure 1. Individuals’ first two genetic ancestry principal components after all PCA-based exclusions of genetic outliers

eFigure 2. Mean adjusted (residualized) PRS-cs-auto-SCZ per group

eFigure 3. Mean PRSice per group

eFigure 4. Odds ratio by adjusted (residualized) PRS-cs-auto risk score profile

eFigure 5. Odds ratio by PRS-ice risk score profile

Nonauthor collaborators