This cluster randomized clinical trial assesses whether the use of population-based electronic screening in addition to standard targeted clinician education increases the early detection of psychosis and decreases the duration of untreated psychosis, compared with clinician education alone.

Key Points

Question

Does population-based electronic screening for first-episode psychosis (FEP) or psychosis spectrum disorder in community settings increase early detection and reduce the duration of untreated psychosis?

Findings

In this cluster randomized clinical trial, a population-based technology-enhanced screening plus clinician education identified more individuals with psychosis spectrum disorder than clinician education alone. No significant difference in duration of untreated psychosis for FEP across groups was detected.

Meaning

Population-based screening for FEP in community mental health settings substantially increases identification of individuals with psychosis spectrum disorders but does not reduce the overall duration of untreated psychosis, so reduction efforts must also specifically target delays between symptom onset and first contact with mental health services.

Abstract

Importance

Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is essential to improving outcomes for people with first-episode psychosis (FEP). Current US approaches are insufficient to reduce DUP to international standards of less than 90 days.

Objective

To determine whether population-based electronic screening in addition to standard targeted clinician education increases early detection of psychosis and decreases DUP, compared with clinician education alone.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cluster randomized clinical trial included individuals aged 12 to 30 years presenting for services between March 2015 and September 2017 at participating sites that included community mental health clinics and school support and special education services. Eligible participants were referred to the Early Diagnosis and Preventative Treatment (EDAPT) Clinic. Data analyses were performed in September and October 2019 for the primary and secondary analyses, with the exploratory subgroup analyses completed in May 2021.

Interventions

All sites in both groups received targeted education about early psychosis for health care professionals. In the active screening group, clients also completed the Prodromal Questionnaire–Brief using tablets at intake; referrals were based on those scores and clinical judgment. In the group receiving treatment as usual (TAU), referrals were based on clinical judgment alone.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes included DUP, defined as the period from full psychosis onset to the date of the EDAPT diagnostic telephone interview, and the number of individuals identified with FEP or a psychosis spectrum disorder. Exploratory analyses examined differences by site type, completion rates between conditions, and days from service entry to telephone interview.

Results

Twenty-four sites agreed to participate, and 12 sites were randomized to either the active screening or TAU group. However, only 10 community clinics and 4 school sites were able to fully implement population screening and were included in the final analysis. The total potentially eligible population size within each study group was similar, with 2432 individuals entering at active screening group sites and 2455 at TAU group sites. A total of 303 diagnostic telephone interviews were completed (178 [58.7%] female individuals; mean [SD] age, 17.09 years [4.57]). Active screening sites reported a significantly higher detection rate of psychosis spectrum disorders (136 cases [5.6%], relative to 65 [2.6%]; P < .001) and referred a higher proportion of individuals with FEP and DUP less than 90 days (13 cases, relative to 4; odds ratio, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.10-0.93; P = .03). There was no difference in mean (SD) DUP between groups (active screening group, 239.0 days [207.4]; TAU group 262.3 days [170.2]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cluster trial, population-based technology-enhanced screening across community settings detected more than twice as many individuals with psychosis spectrum disorders compared with clinical judgment alone but did not reduce DUP. Screening could identify people undetected in US mental health services. Significant DUP reduction may require interventions to reduce time to the first mental health contact.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02841956

Introduction

The duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is a consistent predictor of clinical and functional outcomes.1,2 In the United States, mean DUP is between 1 and 3 years,3 far beyond the 90 days recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).4 Although specialty first-episode psychosis (FEP) programs are more common in the United States recently,5 their standard approaches to outreach, screening, and engagement are ineffective at reducing DUP.6,7 There are 2 phases to DUP: delay from symptom onset to contact with a health care professional (“demand-side” DUP) and delay from such contact to appropriate treatment initiation (“supply-side” DUP).8,9 Studies suggest that supply-side delays are the greatest contribution to DUP, because psychosis is often underdiagnosed in community mental health settings.10,11 This study focuses on identifying individuals with early psychosis in such settings and strengthening the referral pathway to FEP services to reduce DUP.

Population-based screening for psychosis in community mental health settings represents a feasible, efficient, and effective strategy for improving detection of individuals with FEP. In 2 studies completed in the Netherlands, screening led to significantly more individuals with psychosis being referred to FEP care compared with standard referral processes.12,13 However, this has yet to be tested in the United States, where the public mental health system is fragmented and underresourced and serves a population facing a variety of barriers to access.14 A nonrandomized study reported an association between reduced DUP and a comprehensive approach to both demand- and supply-side barriers,15 but the approach did not include screening.

In phase 1 of a 2-phase trial to reduce DUP (NCT02841956), we examined whether tablet-based population screening for psychosis at first contact for mental health services would reduce DUP and increase the number of appropriate referrals to FEP care. A cluster randomized trial design was used across the catchment area to simplify study procedures at the clinic level and minimize the risk of contamination. We hypothesized that, when added to clinician education about early psychosis, population-based technology-enhanced screening would reduce DUP and identify more individuals with FEP, compared with clinician education alone.

Methods

The study and study procedures were approved by the University of California, Davis, institutional review board. All participants and any parents who were included provided written informed consent. Participants were help-seeking individuals presenting for services at participating sites from March 4, 2015, to September 30, 2017. Data analyses were performed in September and October 2019 for the primary and secondary analyses, with the exploratory subgroup analyses completed in May 2021. Reporting followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline.

Four site types were targeted: middle/high schools (student support or special education services), emergency department/inpatient psychiatric hospitals, outpatient community mental health clinics (CMHCs), and pediatric primary care clinics. Individual sites were excluded from the analysis if they were unable to implement population-based screening or they lacked a potential comparison site of the same type (eMethods and eTable in Supplement 1).

All individuals aged 12 to 30 years who could read English and presented at the participating referral sites were potentially eligible. Exclusion criteria at referral were age younger than 18 years and no guardian present; condition deemed delirious, intoxicated, or unsafe; and documented IQ less than 70. Race and ethnicity data, which were self-reported by the patients, were collected to allow for an exploratory analysis related to populations whose health care needs are underserved, such as those in racial and ethnic minority groups. Additional exclusion criteria used during the telephone interview are described in the eMethods in Supplement 1. The trial protocol is provided in Supplement 2.

Procedures

Randomization

We stratified sites by service type and randomized an equivalent number to receive either standard clinician referral (hereafter, treatment as usual [TAU]) or population screening (hereafter, the active screening group) (eFigure in Supplement 1). Seeds to initiate random number sequences were selected randomly. Clients and clinicians were not blinded to trial group because of their involvement in study processes. Study staff conducting telephone interviews were not blinded because of the clinic coordination procedures.

Education Training

Clinical and administrative staff at all sites were provided a standardized 1-hour early-psychosis education training by a licensed clinical psychologist (T.A.N., J.D.R., K.B., T.A.L.). This training covered the rationale for early identification and intervention, how to identify early signs and symptoms, Early Diagnosis and Preventative Treatment (EDAPT) clinic inclusion/exclusion criteria and referral procedures, and an explanation of EDAPT coordinated specialty care services. Training reviewed how to address common participant questions and enhance motivation for engagement using didactic methods and role-play exercises. Study staff contacted site leadership at least monthly to review study implementation and schedule new staff trainings.

Active Screening Group

In addition to education training, active site staff completed a 30-minute training about tablet screening administration, referral procedures, and tablet maintenance. The study application included an informed consent process, basic demographic questionnaire, and the Prodromal Questionnaire–Brief (PQ-B).16 Administration details about the study application are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 1.

Referral Process

If the study application (active screening group only) or clinical judgment (either group) indicated an appropriate referral, clients were offered an EDAPT telephone interview (eMethods in Supplement 1). Site staff were encouraged to refer within the initial clinical evaluation period (defined as 60 days in Sacramento County), although they could refer a client at any time. If a client declined, staff sent a deidentified fax referral form so research staff could record outcomes for all participants with eligible screens/referrals.

Assessment Workflow

Participants were invited for an in-person clinical assessment if the telephone interview indicated either attenuated or threshold psychosis, consistent with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (version 4.0).17 At their clinic intake assessment, participants provided written informed consent to complete questionnaires and link their telephone interview and clinical intake data. Participants were given $25 as compensation for completing all study procedures.

Measure: Prodromal Questionnaire–Brief

The PQ-B is a brief screening tool designed to assess attenuated positive symptoms related to clinical high-risk syndrome and determine the need for a more thorough evaluation.16,18,19 It comprises 21 positive symptom items, recording symptom presence and associated distress or impairment on a 5-point Likert scale. Two scoring thresholds were adopted (eMethods in Supplement 1).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and univariate comparisons were used to summarize data. The definition of DUP was number of days from the onset of psychotic symptoms to the EDAPT telephone interview, at which point the number of individuals per group was counted. This end point was adopted in place of the originally proposed clinic intake because of unexpected clinic staffing issues that caused delays between telephone screen and intake (eMethods in Supplement 1). Comparisons of DUP in the active screening and TAU groups were done by estimating and testing a multilevel linear model to account for clustering by site.

Detection rates were determined by calculating the proportion of individuals identified with FEP (psychosis onset ≤2 years) or psychosis spectrum disorder (clinical high risk or any-duration psychosis) as numerators and the total number of individuals seen for a first appointment at the study sites as denominators, calculated by study group. Comparisons were conducted using relative risk (RR), consistent with previous studies that examined detection rates of different screening strategies.20 Missing data were not imputed.

Exploratory analyses compared the number of individuals identified with a DUP below the WHO recommendation of 90 days21 across groups and differences in case identification by site type using RR. Participant attrition at different points of the process (eg, accepted referral to EDAPT, completed telephone interview) were examined using a Pearson χ2 test. A comparison of supply-side DUP between conditions, defined as the period between presenting at the participating site and completion of the telephone diagnostic assessment, was conducted using a multilevel linear model, consistent with the primary analysis. Supply DUP totals were log-transformed before analysis because of skew. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) was used for randomization and analysis (PROC MIXED procedure).

Results

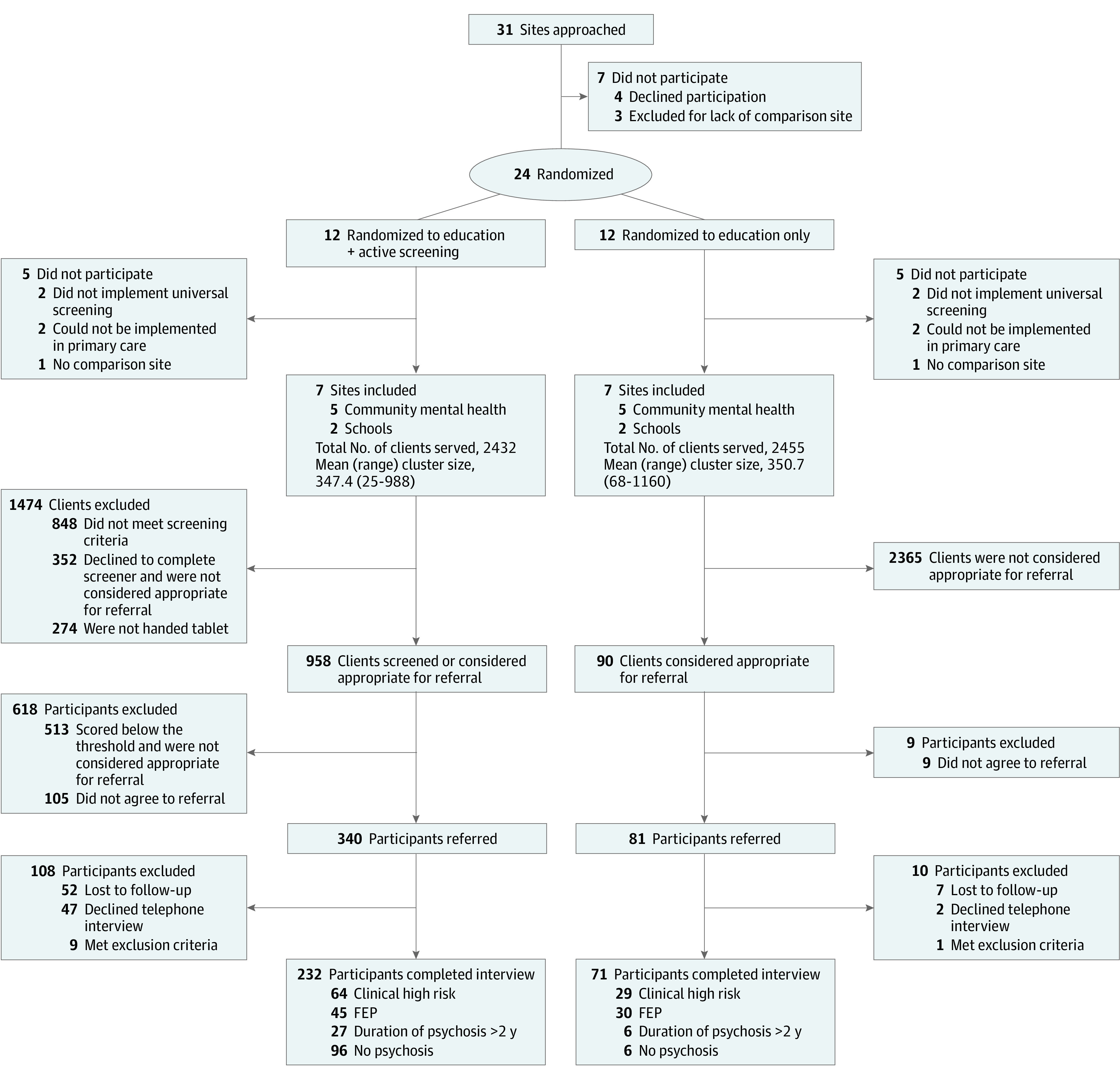

Figure 1 contains the study CONSORT diagram. We approached 31 sites for participation; 24 sites agreed and were randomized by type. However, only 10 CMHC and 4 school sites were able to fully implement population screening and were included in the final analysis. The total potentially eligible population size within each study group was similar (active screening group, n = 2432; TAU group, n = 2455). In the active screening group, 340 individuals were referred, and 232 completed the telephone interview. Sites in the TAU group identified 90 individuals for referral based on clinical judgment; 81 agreed to be referred, and 71 completed the telephone interview.

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram for the Study.

FEP indicates first-episode psychosis.

The Table contains descriptive statistics for the 303 individuals who completed a telephone interview (mean [SD] age, 17.09 years [4.57]; 178 [58.7%] female individuals). Individuals in the active screening group were 1.6 years older (t = –2.62, P = .009), included 14.2% more female individuals (χ2 = 4.02, P = .05), and were less likely to have private health insurance (χ2 = 42.12, P < .001). No correlation between DUP and entry order was detected (r = –0.04, P = .61), so this was not included in subsequent analyses.

Table. Demographic Data for Individuals Who Completed the Telephone Interview.

| No. (%) | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Active screening group | TAU group | χ2 | P value | |

| Individuals referreda | 421 | 340 | 81 | NA | NA |

| Phone interviews completed | 303 | 232 | 71 | NA | NA |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| First-episode psychosis | 75 (24.8) | 45 (19.4) | 30 (42.3) | 15.25 | <.001 |

| Clinical high risk | 93 (30.7) | 64 (27.6) | 29 (40.8) | 4.49 | .03 |

| Duration of psychosis >2 y | 33 (10.9) | 27 (11.6) | 6 (8.5) | 0.57 | .45 |

| No psychosis | 102 (33.7) | 96 (41.4) | 6 (8.5) | 26.4 | <.001 |

| Raceb | |||||

| African American | 91 (30.0) | 70 (30.2) | 21 (29.6) | 0.009 | .92 |

| American Indian | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Asian | 16 (5.3) | 12 (5.2) | 4 (5.6) | 0.023 | .88 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| White | 120 (39.6) | 87 (37.5) | 33 (46.5) | 1.83 | .18 |

| More than 1 race | 33 (10.9) | 23 (9.9) | 10 (14.1) | 0.974 | .32 |

| Other | 43 (14.2) | 40 (17.2) | 3 (4.2) | 7.563 | .006 |

| Ethnicityb | 0.391 | .53 | |||

| Hispanic | 101 (33.3) | 80 (34.5) | 21 (29.6) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 200 (66.0) | 152 (65.5) | 48 (67.6) | ||

| Sex | 4.51 | .03 | |||

| Male | 125 (41.3) | 88 (37.9) | 37 (52.1) | ||

| Female | 178 (58.7) | 144 (62.1) | 34 (47.9) | ||

| Insurance status | 42.12 | ||||

| MediCal/uninsured | 256 (84.5) | 213 (91.8) | 43 (60.6) | <.001 | |

| Private insurance | 46 (15.2) | 18 (7.8) | 28 (39.4) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 17.09 (4.57) | 17.47 (4.81) | 15.86 (3.40) | t = –2.62 | .009 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; TAU, treatment as usual.

Includes individuals with positive results on screening and those determined by clinical judgment in the active screening group.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported and the data collected for exploratory analyses of populations whose health care needs are underserved, such those in racial and ethnic minority groups. The Other group included self-reported races that did not match the other categories listed.

In the active screening group, 626 individuals (26%) were not given the tablet (eg, client arrived late, clinician forgot to give the tablet) or declined screening and were not referred based on clinical judgment. Of the 445 individuals identified for referral, 105 (24%) refused. Modifications to the screening threshold to improve specificity led to 7 clients not being referred. Of the 340 participants referred, 99 (29%) declined the telephone interview or were lost to follow-up. In the TAU group, 90 participants were considered appropriate for a referral, but 9 declined (10%), while 9 individuals (11%) who were referred refused the telephone interview or were lost to follow-up. Dropout rates were significantly higher in the active screening group both at the referral agreement stage and at the point of engagement in the telephone screen (χ2 = 8.25, P = .004; and χ2 = 11.12, P < .001, respectively).

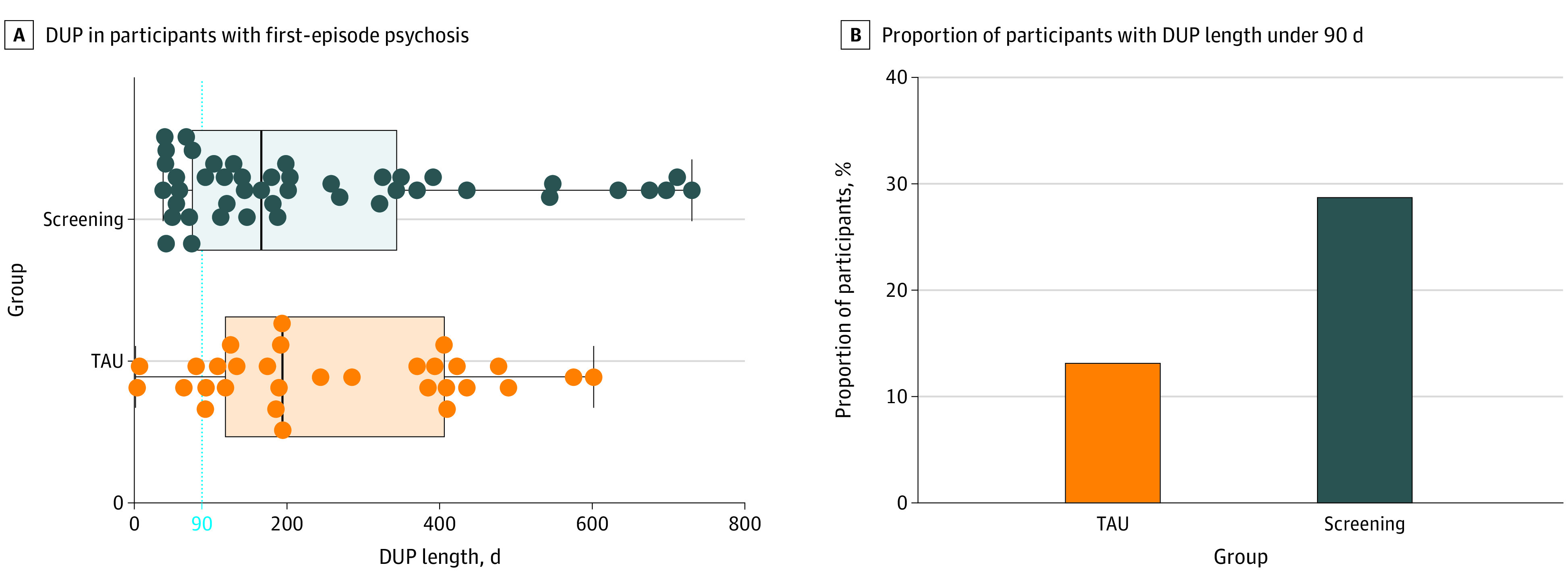

Duration of Untreated Psychosis

Mean (SD) DUP in the active screening group was 239.0 days (207.4) and 262.3 days (170.2) in the TAU group; the median DUP in the active screening group was 167.0 days and 194.5 days in the TAU group (Figure 2A). This difference was not significant (F1,60 = 0.06, P = .80). When the primary analysis was performed in CMHCs only, the mean (SD) DUP in the active screening group was 241.1 days (209.4) and 271.9 days (171.5) in the TAU group. This difference was also not statistically significant (F1,60 = 0.17, P = .68).

Figure 2. Duration of Untreated Psychosis (DUP) Among Participants With First-Episode Psychosis in the Active and Treatment as Usual (TAU) Groups.

In each group in A, the box boundaries indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, with the internal vertical line indicating the median. The whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. Individual dots represent each participant in the data set.

An exploratory analysis (Figure 2B) examined the proportion of individuals per group with a DUP shorter than the WHO-recommended maximum of 90 days.21 The active screening group identified a significantly higher proportion of individuals with DUP less than 90 days (n = 13) compared with TAU (n = 4; OR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.10-0.93).

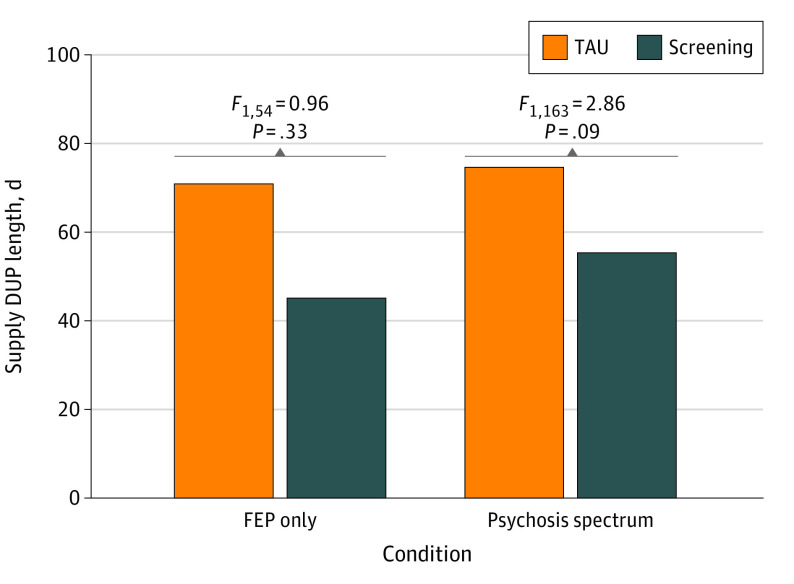

Figure 3 illustrates an exploratory analysis comparing supply-side DUP across both groups. For individuals with FEP, the mean (SD) number of days between first presentation at the referral site to the EDAPT telephone interview was 44.8 (60.1) in the active screening group and 70.6 days (77.7) in the TAU group. After log transformation because of skew, no significant difference was detected (F1,54 = 0.96, P = .33). When all psychosis spectrum cases were considered, the mean (SD) number of days was 54.96 (82.96) in the active screening group and 74.42 (91.87) in the TAU group, which after log transformation was also a nonsignificant difference (F1,163 = 2.86, P = .09).

Figure 3. Supply-Side Duration of Untreated Psychosis (DUP) Length in Days by Condition.

FEP indicates first-episode psychosis; TAU, treatment as usual.

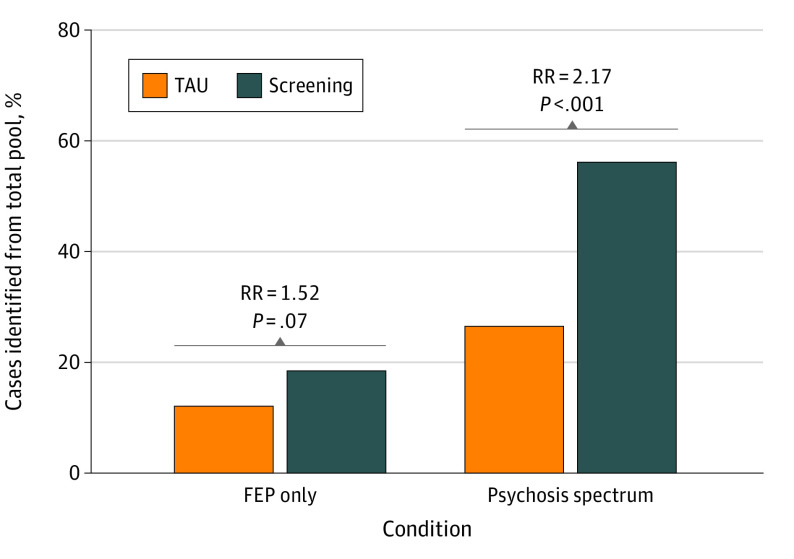

Detection Rates

Of 2432 clients in the active screening group, 45 individuals (1.9%) were diagnosed with FEP, and 136 individuals (5.6%) were diagnosed with a psychosis spectrum disorder at the telephone interview. Of 2455 potentially eligible clients in the TAU group, 30 individuals (1.2%) were diagnosed with FEP, and 65 individuals (2.6%) were diagnosed with a psychosis spectrum disorder (Figure 4). Although the active screening identified 50% more FEP cases relative to TAU, this difference did not reach statistical significance (RR, 1.52; χ2 = 3.19; P = .07). However, the active screening group identified significantly more psychosis spectrum cases (RR, 2.17; χ2 = 26.86; P < .001).

Figure 4. Proportion of Cases of First-Episode Psychosis (FEP) and Psychosis Spectrum Disorder Identified Across All Potentially Eligible Individuals Encountered.

RR indicates relative risk; TAU, treatment as usual.

Detection Rates by Site Type

Of the 2004 clients seen at CMHC sites in the active screening group, 44 individuals were diagnosed with FEP and 129 were diagnosed with psychosis spectrum disorder, a detection rate of 2.2% and 6.4%, respectively. This compares with 428 students in the active screening group seen in school settings, which led to 1 individual being identified with FEP and 7 with a psychosis spectrum disorder, detection rates of 0.2% and 1.6%, respectively (eTable in Supplement 1). When detection rates by group were examined for CMHCs only, the primary findings remained unchanged (FEP: RR, 1.53; χ2 = 3.20; P = .07; psychosis spectrum: RR, 2.13; χ2 = 25.43; P < .001).

Discussion

This study suggests that population-based electronic screening for early psychosis in CMHCs is an effective strategy to increase the number of appropriate referrals to specialty early-psychosis clinics, particularly individuals with clinical high risk, consistent with a screening trial in the Netherlands.13 The intervention also significantly increases the proportion of referred individuals who meet the WHO-recommended maximum DUP of 90 days,21 indicating this may represent an effective method to hasten the pathway to care for at least a subset of clients. However, the intervention did not significantly reduce DUP.

Results indicate that population screening for early psychosis is feasible to implement in CMHCs in the United States. In the active screening group, almost 1000 screens were completed in 7 locations across a broad geographical area. The overall sample had high racial and ethnic diversity, with 39.6% of individuals identifying as White and 33% Hispanic, although those who did not read English were excluded. In a qualitative interview study conducted in conjunction with this trial, health care professionals were positive about the intervention, reporting that it supported ongoing clinical activities, was feasible to implement alongside current practice, and was acceptable to clients, and the software design of the study application was well-liked.22 Future work should explore screening acceptability among individuals using the services and family members.

Although our results are encouraging in terms of feasibility and identification of more young people in the community with psychosis spectrum disorders, they also highlight several challenges. Because of unexpected clinic staffing shortages and outcome measurement at the telephone screen, our figures underreport the full length of supply-side DUP, which would also extend to treatment initiation. Consequently, the true DUP for these participants is longer than the number of days reported here, and some people may have not actually initiated or fully engaged in treatment. Substantial dropout at the point of referral and telephone interview was detected, particularly in the active group (active screening group, 45.8% dropout; TAU group, 20% dropout). This highlights the “leaky pipeline” from identification to linkage for specialty care. Reasons behind this high dropout rate are unclear and merit future exploration to attenuate attrition and enhance the effect of screening. A second challenge was the number and types of sites excluded from the analysis (7 sites [23%]). Two sites lacked a comparator site of the same strata type (emergency department/inpatient psychiatric hospital and community mental health respite center) in the opposite study group. Primary care settings faced too many logistical challenges to administer screening and provide feedback, consistent with issues documented in the literature (eg, brief appointments with a large range and complexity of presenting issues and limitations on staff availability23). Consequently, we determined that the feasibility and validity of early-psychosis screening in primary care merited a separate investigation, which is currently ongoing.

Finally, implementation of screening in schools is challenging. Four schools had too few staff for the number of individuals presenting for care at any given time and were only able to do ad hoc screening. School settings that provide broad social-emotional support were better able to implement screening with a wide array of students compared with special education services, but they still struggled with parent engagement to obtain consent for treatment referral.24 In a related qualitative study, we identified ethical concerns, logistics, screening population, and stigma as factors contributing to feasibility of screening in school settings.24 Fewer cases, and likely shorter DUP, would be expected overall in schools where screening was a selected prevention strategy compared with the indicated prevention approach in CMHCs.25 Based on the present study, we can only conclude that population-based screening is feasible in CMHCs and some school support settings to identify psychosis spectrum disorders.

In this study, relative to TAU, the active screening group detected more individuals with psychosis spectrum disorder but no differences in DUP length. However, if the prevalence of psychosis is equivalent across groups and 1 group detects significantly more cases, DUP length comparisons are only appropriate if DUP is equivalent between detected and undetected cases. This assumption is problematic, given it is likely that cases that are more challenging to identify remain unidentified for a longer period. Furthermore, in those undetected cases, DUP length continues to increase until later detection. This highlights the issue of using DUP length as a metric to evaluate the effectiveness of DUP reduction efforts.

Notably, a recent meta-analysis failed to detect any significant associations with various DUP interventions, such as availability of FEP clinical services or training of health care professionals, compared with control conditions.14 The multiple contributors to delayed access in the US public mental health system may produce a majority of delays before the point of entering mental health care, thus reducing our ability to find a significant difference in DUP in the current study. Therefore, screening efforts within health care services should be combined with demand-side approaches that focus on reducing the length of time before an individual presents to services, such as community awareness campaigns (as studied by others26,27) and identifying individuals seeking services on the internet.28 Additionally, the fragmentation and complexity of the mental health care system in the United States can prolong DUP for individuals who must find a health care professional who offers FEP services and takes their insurance and has capacity to see them. Increased mental health block grant set-aside funds for FEP care can address this supply-side issue but are not sufficient to provide care for the number of individuals who need it.29 Reducing DUP requires efforts to increase awareness and identification of individuals with psychosis, while also addressing barriers to access of appropriate care. Future work should evaluate the effect of combining both demand-side and supply-side DUP reduction strategies15 in randomized trials.

The greatest challenge to implementing population-based early-psychosis screening is the high false-positive rate. Being mistakenly identified as potentially at risk for psychosis can lead to distress and stigma.30 To minimize its effect, screening staff must be trained to assure individuals who screen positively that this finding only indicates more assessment may be useful and is not diagnostic. Specialty care staff who complete telephone screens and assessments must be equally well trained in these issues to manage the expectations and fears associated with additional evaluation. Additionally, screening resulted in a substantial increase in the referral rate. Consequently, significant resources are needed to support widespread screening across a large community, which comes with a significant opportunity cost.

In sum, this study targets a very specific point in the pathway to specialty care with a technology-enhanced solution to identify more individuals with early psychosis and hasten their access. Going forward, a multifaceted approach incorporating strategies to reduce both demand-side and supply-side DUP holds the most promise. Building on recent successful combined strategies, we recommend adding population screening to community education, stigma reduction, and improved pathways to care online, in conjunction with the broadening of insurance coverage and interventions designed to facilitate full engagement in specialty treatment.15,31,32 This may be a more effective and comprehensive solution to reduce DUP overall and thus improve long-term client outcomes.

Limitations

Some limitations of the study should be acknowledged. As mentioned above, our figures underreported the full length of supply-side DUP because of unexpected clinic staffing shortages. These staffing shortages would also affect treatment initiation. Substantial dropout at the point of referral and telephone interview was detected for reasons that are unclear. Different study sites, such as primary care clinics, faced challenges in implementing screening and reporting feedback; schools struggled with staffing issues and parent engagement. Furthermore, using DUP length as a measure when evaluating DUP reduction relies on the assumption that DUP is equivalent between detected and undetected cases, but cases that are more challenging to identify may remain unidentified for a longer period and increase the DUP length until later detection.

Conclusions

In this cluster randomized trial, population-based technology-enhanced screening in addition to standard clinician training across community settings detected more than twice as many individuals with psychosis spectrum disorders compared with clinical judgment alone but did not reduce DUP. Screening could identify people undetected in US mental health services. Significant DUP reduction may require interventions to reduce time to the first mental health contact.

eMethods

eTable. Study sites included in analysis

eFigure. Study procedures

eReferences

Trial protocol

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):975-983. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1785-1804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho BC, Alicata D, Ward J, et al. Untreated initial psychosis: relation to cognitive deficits and brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):142-148. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertolote J, McGorry P. Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: consensus statement. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;48:s116-s119. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niendam TA, Sardo A, Savill M, et al. The rise of early psychosis care in California: an overview of community and university-based services. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(6):480-487. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lloyd-Evans B, Crosby M, Stockton S, et al. Initiatives to shorten duration of untreated psychosis: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(4):256-263. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norman RM, Malla AK, Verdi MB, Hassall LD, Fazekas C. Understanding delay in treatment for first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2004;34(2):255-266. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srihari VH, Tek C, Pollard J, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis and its impact in the U.S.: the STEP-ED study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:335. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0335-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birchwood M, Connor C, Lester H, et al. Reducing duration of untreated psychosis: care pathways to early intervention in psychosis services. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(1):58-64. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.125500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boonstra N, Wunderink L, Sytema S, Wiersma D. Detection of psychosis by mental health care services; a naturalistic cohort study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2008;4:29. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-4-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boonstra N, Wunderink L, Sytema S, Wiersma D. Improving detection of first-episode psychosis by mental health-care services using a self-report questionnaire. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(4):289-295. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2009.00147.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rietdijk J, Klaassen R, Ising H, et al. Detection of people at risk of developing a first psychosis: comparison of two recruitment strategies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(1):21-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01839.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, et al. Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1362-1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srihari VH, Ferrara M, Li F, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in a US community: a quasi-experimental trial. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgab057. doi: 10.1093/schizbullopen/sgab057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire–brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42-46. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGlashan TH. Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS). Yale University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loewy RL, Bearden CE, Johnson JK, Raine A, Cannon TD. The Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ): preliminary validation of a self-report screening measure for prodromal and psychotic syndromes. Schizophr Res. 2005;77(2-3):141-149. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loewy RL, Johnson JK, Cannon TD. Self-report of attenuated psychotic experiences in a college population. Schizophr Res. 2007;93(1-3):144-151. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norton LB, Peipert JF, Zierler S, Lima B, Hume L. Battering in pregnancy: an assessment of two screening methods. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(3):321-325. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00429-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertolote J, McGorry P. Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: consensus statement. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;48:s116-s119. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savill M, Skymba HV, Ragland JD, et al. Acceptability of psychosis screening and factors affecting its implementation: interviews with community health care providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(6):689-695. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linzer M, Bitton A, Tu SP, et al. ; Association of Chiefs and Leaders in General Internal Medicine (ACLGIM) Writing Group . The end of the 15-20 minute primary care visit. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(11):1584-1586. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3341-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer MS, Rosenthal A, Bolden KA, et al. Psychosis screening in schools: considerations and implementation strategies. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;14(1):130-136. doi: 10.1111/eip.12858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders ; Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ, eds. Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. National Academies Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connor C, Birchwood M, Freemantle N, et al. Don’t turn your back on the symptoms of psychosis: the results of a proof-of-principle, quasi-experimental intervention to reduce duration of untreated psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:127. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0816-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd-Evans B, Sweeney A, Hinton M, et al. Evaluation of a community awareness programme to reduce delays in referrals to early intervention services and enhance early detection of psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:98. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0485-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birnbaum ML, Rizvi AF, Confino J, Correll CU, Kane JM. Role of social media and the internet in pathways to care for adolescents and young adults with psychotic disorders and non-psychotic mood disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2017;11(4):290-295. doi: 10.1111/eip.12237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radigan M, Gu G, Frimpong EY, et al. A new method for estimating incidence of first psychotic diagnosis in a Medicaid population. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(8):665-673. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corcoran CM. Ethical and epidemiological dimensions of labeling psychosis risk. AMA J Ethics. 2016;18(6):633-642. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.6.msoc2-1606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrara M, Guloksuz S, Li F, et al. Parsing the impact of early detection on duration of untreated psychosis (DUP): applying quantile regression to data from the Scandinavian TIPS study. Schizophr Res. 2019;210:128-134. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moe AM, Rubinstein EB, Gallagher CJ, Weiss DM, Stewart A, Breitborde NJ. Improving access to specialized care for first-episode psychosis: an ecological model. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2018;11:127-138. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S131833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eTable. Study sites included in analysis

eFigure. Study procedures

eReferences

Trial protocol

Data sharing statement