Abstract

Background

Older people living with HIV (PLWH) are at increased risks of co-morbidities and polypharmacy. However, little is known about factors affecting their needs and concerns about medicines. This systematic review aims to describe these and to identify interventions to improve medicine optimisation outcomes in older PLWH.

Methods and Data Sources

Multiple databases and grey literature were searched from inception to February 2022 including MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, PsychArticles, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials, Abstracts in Social Gerontology, and Academic Search Complete.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies reporting interventions/issues affecting older PLWH (sample populations with mean/median age ≥ 50 years; any aspect of medicine optimisation, or concerns). Quality assessments were completed by means of critical appraisal checklists for each study design. Title and abstract screening was led by one reviewer and a sample reviewed independently by two reviewers. Full-paper reviews were completed by one author and a 20% sample was reviewed independently by two reviewers.

Synthesis

Data were extracted by three independent reviewers using standardised data extraction forms and synthesised according to outcomes or interventions reported. Data were summarised to include key themes, outcomes or concerns, and summary of intervention.

Results

Seventy-nine (n = 79) studies met the eligibility criteria, most of which originated from the USA (n = 36). A few studies originated from Australia (n = 5), Canada (n = 5), Spain (n = 9), and the UK (n = 5). Ten studies originated from Sub-Saharan Africa (Kenya n = 1, South Africa n = 6, Tanzania n = 1, Uganda n = 1, Zimbabwe n = 1). The rest of the studies were from China (n = 1), France (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 1), Saudi Arabia (n = 1) and Ukraine (n = 1). Publication dates ranged from 2002 to 2022. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 15,602 across studies. The factors affecting older PLWH’s experience of and issues with medicines were co-morbidities, health-related quality of life, polypharmacy, drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, adherence, medicine burden, treatment burden, stigma, social support, and patient-healthcare provider relationships. Nine interventions were identified to target older persons, five aimed at improving medication adherence, two to reduce drug interactions, and two for medicine self-management initiatives.

Conclusion

Further in-depth research is needed to understand older PLWH’s experiences of medicines and their priority issues. Adherence-focused interventions are predominant, but there is a scarcity of interventions aimed at improving medicine experiences for this population. Multi-faceted interventions are needed to achieve medicine optimisation outcomes for PLWH.

Trial Registration

This study is registered with PROSPERO registration number: CRD42020188448.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40266-022-01003-3.

Key Points

| Older people living with HIV have various factors that impact on their needs and concerns about medicines (e.g., polypharmacy, treatment burden, adherence support, stigma, and social support). |

| Only a few interventions have been developed to improve medicines optimisation outcomes, but most of these are adherence-focussed. |

| There is a need for further studies to better understand the needs and concerns of older people living with HIV in the UK about their medicines and to design multi-faceted interventions to reflect these. |

Introduction

Globally, about 38 million people continue to live with HIV [1]. Advances in treatment have transformed HIV into a complex chronic condition [2] and more people living with HIV (PLWH) have a near-normal life expectancy [3]. New diagnoses among PLWH over the age of 50 years are on the rise [4]. In the UK, nearly two-thirds (65%) of late HIV diagnoses were among those aged ≥ 65 years [5]. It is estimated that by 2030 nearly 75% of all PLWH will be 50 years or older, with the median age expected to increase gradually over the years [6]. A number of age cut-offs have been used to define older PLWH, ranging from 45 to 55 years old with 50 years and older used frequently across most literature [4, 7, 8]. For the purposes of this review, an ‘older person’ will include anyone aged 50 years or older.

Ageing within the context of HIV is associated with multimorbidity and polypharmacy [9, 10]. Polypharmacy has widely been defined as the use of five or more medicines, [11] and is linked to adverse health outcomes [12]. A recent multinational patient survey conducted in 24 countries including North America, Europe, Australia and China (n = 2112), reported a significantly higher level of polypharmacy among older PLWH (54.6%) compared with younger participants (36.5%, p < 0.001) [10]. The survey also found that people experiencing polypharmacy used an average of 6.5 pills per day, and willingness to change antiretroviral (ARV) regimens to those with a fewer number of medicines was significantly higher among older adults (79.9%) than those under 50 years old (70.1%, p < 0.001) [10]. An earlier study on older PLWH found that participants were taking a median of 13 (range 9–17) medicines, of which eight (range 4–14) were non-ARV medicines [13]. Polypharmacy is associated with regimen complexity, medicine burden, lower treatment satisfaction, potential drug–drug interactions (PDDIs), adverse drug reactions (ADRs), hospitalisation, non-adherence, and contributes to poor health outcomes [9, 10, 12, 14, 15]. A study investigating polypharmacy among PLWH found a correlation between the number of non-ARV medicines used and adverse health outcomes in older individuals [15]. There is a need to understand treatment experiences of older PLWH.

NICE guidelines define medicines optimisation, as “a person-centred approach to safe and effective medicines use, to ensure people obtain the best possible outcomes from their medicines”, which is fundamental in tackling the challenges presented by polypharmacy among older adults [16]. Medicine experiences are the summation of events involving drug therapy that one has encountered in their lives [17]. According to the UK’s Royal Pharmaceutical Society, medicines optimisation aims to understand patients’ experiences and to improve patient outcomes from a holistic perspective [18]. Across the literature, medicines optimisation is implemented through various interventions including medicine reviews [19], deprescribing [14], medicine reconciliations [11, 19], identifying potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP) [19, 20], providing social support, and increasing antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence [11]. A recent systematic review of interventions for frail older persons focused on medicines optimisation in secondary care settings [21], but was not specific to PLWH. Moreover, little is known about medicines optimisation interventions targeted at older PLWH. In some studies, older PLWH have reported concerns around stigma. Older PLWH may experience stigma twofold due to HIV-positive status and ageing [22]. It is therefore vital to understand the needs and concerns of older PLWH and to investigate interventions aimed at improving medicines optimisation outcomes for this population.

The aim of this review was to investigate medicines optimisation needs and interventions for older PLWH. The specific objectives were to determine: (a) the priority issues and concerns of older PLWH about their medicines, and (b) the types of medicines optimisation interventions developed for older PLWH, how they are implemented, and their effectiveness.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The review was registered with the international Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews PROSPERO prior to data abstraction (CRD42020188448) [23].

Study Eligibility—Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included various study designs, including but not limited to randomised, controlled trials (RCTs), before and after experimental studies (controlled and non-controlled), observational studies (cohort studies, case-control, cross-sectional surveys), qualitative research studies, and retrospective and prospective reviews of prescription and/or dispensing records. Case reports and case series were excluded regardless of age composition. Service evaluations and audits conducted to improve medicine-related outcomes in a specific health facility or organisation were excluded. We included studies composed of HIV-positive older adults as the main participants or where the vast majority of participants were of mean/median age 50 years or older. Studies focusing on other age groups besides older persons were excluded (i.e., children, adolescents and younger adults under the age of 50 years). Abstracts did not always report participants’ age, and therefore extra screening of full texts was done to determine if studies met the age eligibility criterion. For studies not reporting the mean/median age of participants within the abstract, the full text was reviewed to ascertain age composition of participants [see Online Supplementary Material (OSM): Appendix 1]. Studies of HIV-negative older adults were excluded from the review. Studies relating to any aspect of medicines optimisation, medicine reviews, medicine reconciliation, deprescribing, or strategies being undertaken to support older PLWH with safe and effective use of ART and/or non-HIV medicines were included. Studies that did not discuss any aspect of medicines optimisation or issues relating to medicines experience or that concerned older persons’ needs in relation to their medicines were also excluded. The search was limited to studies published in English.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

A range of electronic databases were searched from date of inception to February 2022. We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, PsychArticles, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials, Abstracts in Social Gerontology, and Academic Search Complete. We also searched grey literature via OpenGreyTM, including doctoral theses, research reports and other publications. We searched reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews to identify additional studies. A digital referencing manager, Zotero (5.0.89), was used to manage all searches and to remove duplicates. To answer the research question, our Population Intervention Comparison Outcome (PICO) search strategy [24] included key words to maximise our ability to find relevant articles (OSM: Appendix 2). Examples of search terms used include: HIV, AIDS, ageing/aging, older/elderly, medicines, antiretrovirals, HAART/ART, optimis*, intervention, pharmaceutical, medicine-related problems, concerns, needs, issues, outcome. A full list of search terms is provided in the OSM (Appendix 3). The same search strategy was adapted for all databases, with minor changes to the wildcard symbols and truncations for searching different words with similar prefixes.

Selection of Studies

Titles were screened for eligibility by one author (PS). Abstracts and full texts were then independently reviewed by three authors (PS, RC, BK) using pre-specified screening criteria (OSM: Appendix 4). Each study was then categorised into: ‘definitely include’, ‘possibly include’ and ‘definitely exclude’. Full texts for all studies in the ‘definitely include’ and ‘possibly include’ categories were retrieved for assessment against eligibility criteria by PS and then a sample (20%) independently reviewed (RC, SC, BK) [25]. Disagreements at any stage of screening were resolved through discussions among the research team.

Data Extraction, Synthesis Methods, and Risk of Bias Assessment

Data from eligible articles were extracted using a standardised data extraction form (OSM: Appendix 5). One reviewer (PS) led data extraction and a sample of the results (20%) were independently reviewed by two reviewers (RC, SC). Discrepancies in data extracted were resolved by discussion and consensus among the research team.

Synthesis- research papers were categorised thematically (e.g., polypharmacy, treatment burden, medicine burden, adherence) and by the interventions reported (OSM: Appendix 5, Part 2).

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist and the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) were used to assess the risk of bias in and quality of the studies included in the final pool. Specific checklists were used as appropriate for each study design. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with the team. Each question in the appraisal tool was graded as 1 or 0 for meeting or not meeting predefined criteria, respectively; scores and percentages were then calculated to assess overall quality. Overall, studies achieving 0–49% were defined as poor quality, 50–69% were fair quality and 70–100% were of excellent quality.

Results

Study Selection

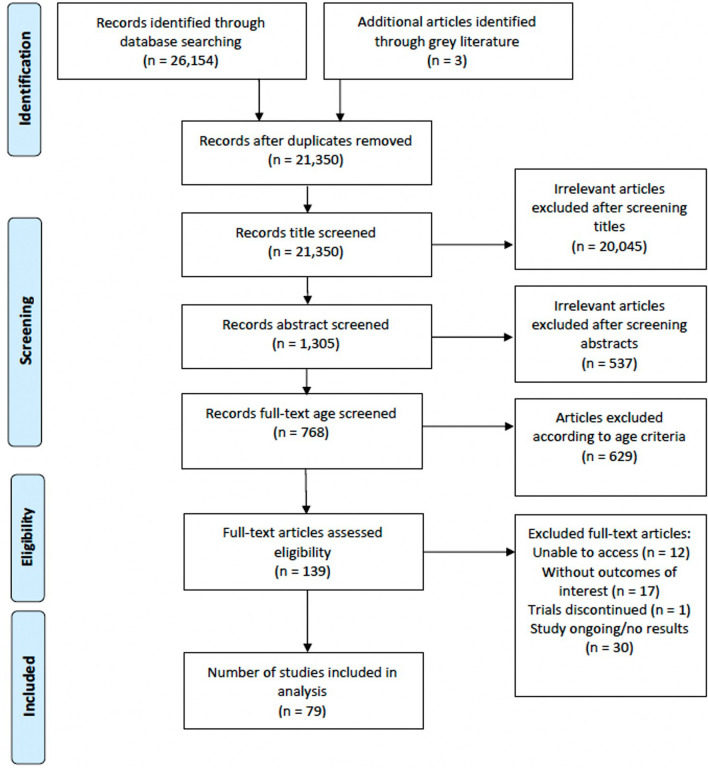

The search identified 26,154 articles from electronic databases and three articles from grey literature. After duplicate removal, 21,350 articles were title screened, of which 1305 were found to be eligible for abstract screening. Of the 1305 abstracts, 768 full texts were searched to determine whether they met the age criterion. 139 remaining articles were then assessed for other eligibility criteria, of which 60 articles were excluded due to either the study not having outcomes of interest (n = 17), the trial being discontinued (n = 1), incomplete study/no results (n = 30), and unable to access due to journal restrictions (n = 12). Overall, 79 (n = 79) studies were included in this review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review

Study Characteristics

The review included 46 cross-sectional studies, 20 qualitative studies, five cohort studies, four RCTs, and four mixed-methods studies. Overall, all articles included were of excellent quality (70–100%). The mean score for the cross-sectional studies was 84% (range 73–90%) based on the AXIS quality assessments. Mean quality scores of 91% (range 70–100%), 91% and 79% (range 71–93%) were obtained for qualitative studies, RCTs and cohort studies, respectively.

The 79 studies that met the inclusion criteria were largely from the USA (n = 36). A few studies originated from Australia (n = 5), Canada (n = 5), Spain (n = 9) and the UK (n = 5). Ten studies originated from Sub-Saharan Africa (Kenya n = 1, South Africa n = 6, Tanzania n = 1, Uganda n = 1 and Zimbabwe n = 1). The rest of the studies were from China (n = 1), France (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 1), Saudi Arabia (n = 1) and Ukraine (n = 1). Publication dates ranged from 2002 to 2022. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 15,602 across individual studies.

Issues Affecting Older People Living with HIV (PLWH)

The studies reviewed showed a wide range of issues affecting older PLWH that impacted on their needs for and experiences of using medicines including co-morbidities, polypharmacy, drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, adherence, stigma, medicine burden, treatment burden, health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and patient and healthcare provider relationships (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author, year (country) | Participant characteristics and study setting | Methods | Intervention reported or tools used for medicine optimisation | Key findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al., 2021 (Pakistan) [65] |

n = 602 32.9% > 50 years Hospital |

Participants were given a validated generic HRQOL questionnaire | EuroQol quality of life scale EQ-5D-3L and Visual Analogue Scale | 59.5% of participants reported no impairment in self-care, however, 63.1% were extremely anxious/depressed. Overall, the mean EQ-5D utility and Visual Analogue Scale scores were 0.388 (SD = 0.41) and 66.20 (SD = 17.22), respectively. Multiple regression analysis has shown that age over 50, the female gender, primary or secondary education, less than a year since HIV diagnosis, having a detectable viral load, and a longer time to ART were all factors significantly associated with HRQOL | The results cannot be generalised to non-adherent PLWH as participants who failed to show up regularly according to their dispensing records were excluded from the study. Moreover, the cross-sectional study design does not allow for causality analysis and there is a possibility of social desirability bias as participants are likely to under-report socially undesirable behaviours |

| Ventuneac et al., 2020 (USA) [53] |

n = 406 M = 50.7 Community |

Intervention study: This study consisted of a single-arm prospective study design with assessments at baseline and 6 months | Rango (mobile health application) | 95% of participants returned for a follow-up visit, with 59% (38/65) of those who were unsuppressed at baseline achieving viral suppression. Viral suppression among Rango participants and those receiving usual care were similar (p = 0.84) and increased in both groups at six months (p < 0.001). Significant difference in the number of unsuppressed participants (n = 65) at baseline who were suppressed (n = 38) at 6 months (p = 0.006) | The findings are limited by the short study duration and a lack of useability data. Usage changes were not analysed over the 6 months |

| Nguyen et al., 2018 (USA) [62] |

n = 176 M = 58.7 years (SD = 5.4) Community |

Data pertaining to HIV-positive participants was obtained from the 2012 baseline cohort from the Research Core of the Rush Centre of Excellence on Disparities in HIV and Aging | The CESD-10, the 30-item MMSE, the 5-item De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale, and the Everyday Discrimination Scale | Participants with good/excellent health showed greater purpose in life, fewer depressive symptoms, more education, and less loneliness than those with poor fair health. Less depressive symptoms, disabilities, adverse life events, and loneliness were associated with higher healthy days index scores. Health-related quality of life was linked to disabilities, smoking status, depression, race/ethnicity, and purpose in life | The cross-sectional study design does not allow for causality interpretations, and self-reported data may include response bias. The participants in this study had good virologic control and thus generalisability to those with less virological control may be reduced |

| DeFulio et al., 2021 (USA) [98] |

n = 50 M = 52.4 years (SD = 10.7) Community |

Intervention study: Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) cap were given to participants attached to their primary ART medication bottle to measure adherence. Participants were placed into either the intervention or control group. Participants were given smart phones that had the intervention app and had to submit videos of medication consumption. At the beginning and every month after surveys were given to participants | Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) cap and smartphone-based intervention app ("SteadyRX") | Participants in the intervention group submitted 75% of required videos, of which 81% met validity criteria, thus indicating a high usability level. Over the study duration the percentage of adherent participants decreased in the control group (p = 0.031). The control group self-reported an average adherence of 91.10% adherence and 94.34% was reported by the intervention group, but this was not a significant difference | A limitation of this study is the small sample size and single site recruitment, reducing generalisability of the findings. Another study limitation could be the lack of requiring a detectable viral load. Finally, the biometric data collecting procedure was flawed, creating another study limitation |

| Lopez-Centeno et al., 2020 (Madrid) [20] |

n = 1292 Median = 69 years (67–73) Community and Hospital pharmacies |

Dispensation registries of community and hospital pharmacies from the Madrid Regional Health Service was analysed between January to June 2017. The Beers criteria was used to identify potentially inappropriate medications among older PLWH | The 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers criteria | Polypharmacy was observed in 65.9% of older PLWH. Cardiovascular (69.7%), gastrointestinal and metabolism (68.2%), and nervous system (61.0%) drugs were among the most prescribed co-medications among participants. At least one potentially inappropriate medication was identified in 37.3% (482) participants. 667 potentially inappropriate medications were identified in 482 participants, 60.8% (293) involved benzodiazepines, and 27.2% (131) involved nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | One limitation to the study is that over-the-counter medicines were not included, this may have led to an under-estimation of potentially inappropriate medications. Moreover, the study is limited by a lack of information on participants co-morbidities, medical managements, such as potential dosage adjustments, and the absence of information on the clinical outcomes of patients with potentially inappropriate medication |

| Jakeman et al., 2021 (Switzerland) [74] |

n = 1019 Median = 70 years Nationwide |

Prescriptions of eligible participants from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) were reviewed to assess anticholinergic (ACH) medication | An average of 5 (± 3.6) non-HIV drugs were taken by participants. 20% of participants were on one ACH medication, reporting average ACH scores of 1.7 (± 1.3). Self-reported neurocognitive impairment was associated with depression and being on one ACH medication | A limitation to this study includes that adherence to ACH medications were not assessed so it cannot be determined if participants were taking their prescribed medications. Dose or duration of ACH medication and history of CNS infection was not evaluated, which all impacts neurocognitive impairment. Self-reported depression rating scales were not available; thus, the diagnosis of depression may have been missed in some of the cohort | |

| Fischetti et al., 2022 (USA) [51] |

n = 1144 Median = 52 years Community |

Data were collected retrospectively via medical chart reviews | Most participants (48%) had one or two co-morbidities, with two participants having 5 co-morbidities. 80% of participants had an undetectable viral load. Higher viral suppression was seen in participants with more co-morbidities (p = 0.009). It was reported that participants with psychiatric disorders had the lowest viral suppression compared to other co-morbidities | Generalisability of the study findings is reduced due to recruitment being from a single site. The number of medications taken per disease and data on disease control was not taken | |

| Hartzler et al., 2019 (USA) [60] |

n = 44 M = 52.3 years Hospital and Community |

Data were collected through focus groups and a survey for demographic information | The study found an emerging theme across staff focus groups of wanting therapy to be patient centred, adaptable, and mission-congruent. Patients reported desiring therapy to have patient autonomy in illness management and fairness among service users. Staff perceived higher compatibility for motivation interviewing than cognitive behavioural therapy or contingency management, this was similar among patients albeit a less robust or reliable pattern | A limitation of the study includes potential bias in participant responses within the focus groups due to social desirability. The generalisability of the study findings is reduced due to the small sample size | |

| Furlotte et al., 2017 (Canada) [92] |

n = 11 Age: 52–67 years Community |

Semi-structured interviews, a checklist of health and social services, and a demographic questionnaire were used to collect data | Three main themes emerged from the interviews: uncertainty, stigma, and resilience. Uncertainty impacting on mental health was reported due to unexpected survival, medical uncertainty, and perception of one's symptoms. Stigma experiences were caused by discrimination in health care interactions, being stigmatised due to physical appearance, anticipated stigma, misinformation, and compounded stigma. Individual approaches to resilience helped participants cope with these experiences, examples include decreasing the space that HIV consumes in their life, making lifestyle changes around the condition, and using social supports | Limitations to the study include that recruitment was of participants attending their local clinic service and the results cannot be generalised to those not attending care services. Full mental health histories were not taken; thus, it is not possible to determine whether participants had mental health concerns before or after their HIV diagnosis | |

| Lee, 2019 (USA) [82] |

n = 97 M ≥ 50 years for all groups Community |

Self-report measures were used to collect data on demographics, ART medication information and medication adherence. Pharmacy and medical records were also used for data collection | Medication adherence, both self-reported and pharmacy-based, or executive functioning was not significantly associated with cigarette smoking. Poor self-reported medication adherence was associated with symptoms of clinical and subclinical levels of anxiety and depression | Generalisability of the study findings are reduced due to recruitment being from a single site. Overall status of health was not measured, which may have impacted the findings. Some participants found the self-reported adherence questionnaire to be difficult to understand, this may have affected the findings, also pharmacy-based adherence data was based on pharmacy refill data, which may not always mean participants are taking the medications they collect | |

| Jacomet et al., 2020 (France) [59] |

n = 1137 M = 50.2 years Hospital and community |

Data were collected through surveys | The presence of co-morbidities was reported in 64.2% of participants and 90% had a undetectable viral load. 58% of participants knew of the medication file, however, only 40% of pharmacists reported to offering it systematically. 32% of participants would like to use the medication file programme, particularly those with shorter ARV duration, a less often undetectable viral load and those who experience anxiety more often | Generalisability of the study results are reduced due to the sample population being predominantly male | |

| Zheng et al., 2022 (China) [61] |

n = 185 M = 58 years (SD = 7.5) Hospital and community |

Data were collected using questionnaires | The Chinese version of the Living with Medicines Questionnaire version 3 (LMQ-3) and the Centre for Adherence Support Evaluation (CASE) Adherence Index | Polypharmacy was reported in 40% of participants. A higher level of medicine-related burden was reported in females, who took more drugs and had a lower monthly income. ART adherence was negatively associated with medicine-related burden (p = 0.001) | Limitations include that data were collected via self-report and was not verified using medical records, prevalence of PDDI in this study may have been underestimated as the Liverpool interaction database does not include information on traditional Chinese medicines or herbal drugs, and as recruitment occurred only at two sites in the Hunan province, findings may not be generalisable elsewhere |

| Uphold et al., 2004 (USA) [46] |

n = 19 (≥ 50 years) and n = 18 (< 40 years) Older group: M = 58 years (SD = 7) Hospital |

Data were collected using electronic medical records | Adverse side effects from highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) were uncommon in the two age groups, with only 4 participants stopping HAART due to adverse effects. Viral load improved significantly for both groups on HAART (p = 0.0001) | Generalisability of the study results are reduced due to the sample population being predominantly male | |

| McInnes et al., 2013 (USA) [81] |

n = 1871 36% = 45–54 years, 43% = 55–64 years and 11.7% ≥ 65 years Community clinics |

Data collected via the Veterans Aging Cohort Study was used to investigate an association between patient electronic personal health record use and ARV adherence. Pharmacy-refill data was used to assess adherence | Personal health record: My HealtheVet | The study found that younger participants (under 45 years) were less adherent than older participants (over 55 years). Participants ≥ 65 years old were less likely to use the personal health record than those < 45 years old. Personal health record use was linked to better adherence | The cross-sectional study design limits the ability to establish a causal relationship between personal health records and adherence. Moreover, there may be unmeasured confounding factors. Pharmacy refill data may overestimate adherence as patients may be collecting their medications without administering them |

| Rosenfeld et al., 2020 (UK) [41] |

n = 100 Median = 56 years (50–87) Hospital and community |

Focus groups, life-history interviews, and surveys were used to collect data | Distinguishing support from HIV-negative (Goffman's 'the wise') people and support based on experiences of PLWH themselves (Goffman's 'the wise'), participants viewed the former as requiring supplementation by the later. Experientially based support varied across groups | A limitation to this study is that focus groups may have led to social desirability bias or moderator bias | |

| Gardenier et al., 2010 (USA) [80] |

n = 56 M = 50.5 years (SD = 8.5) Community (AIDS day health care program) |

Information was extracted from medical records then reviewed and corrected by participants. Participants also completed the Social Provision Scale and the AIDS Clinical Trial Group adherence follow-up instrument | Social Provision Scale (SPS) and the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) adherence follow-up instrument | There was a statistical significance between adherence and social support (p = 0.02). Out of the 51 participants who were prescribed ART, 28 (55%) were adherent. There was a statistically significant difference between CD4 T-cell counts between the adherent and non-adherent group, with the latter being lower (p = 0.004) | The study is limited due to the sample size, recruitment not being randomised, and the participants being recruited at two New York city locations from the AIDS Day Health programme |

| Bosire, 2021 (South Africa) [57] |

n = 15 40–70 years Hospital and community |

Data were collected using an ethnographic approach and through 90-min interviews | Participants access to care to manage their co-morbidities were impeded by fragmentation of care, having multiple clinic appointments, conflicting information, and poor patient-provider communication | The small sample size and single site for recruitment reduces the generalisability of the study findings. Language barriers and the use of an interpreter may have changed the meaning of statements reported by participants | |

| Frazier et al., 2018 (USA) [79] |

n = 3672 over 50 years old Hospital and community |

Matched interview and medical record abstraction data from a surveillance system, the Medical Monitoring Project (MMP), was analysed | Women living with HIV over 50 years old were more likely to be prescribed antiretroviral therapy, be virally supressed, be dose adherent, and are less likely to have received sexually transmitted infection prevention information from a healthcare provider, have condomless sex with a negative or unknown partner and report depression compared to women under 50 years old | The limitations to this study are that generalisability of findings are reduced due data being collected from HIV positive women who are in care and not those who are not receiving medical care and the cross-sectional study design does not allow for causality analysis of findings | |

| Schatz et al., 2021(South Africa) [48] |

n = 23 Age ≥ 50 years Community |

In-depth semi-structured interviews | Perceived shame of sexuality and disrespect by clinical staff, disclosing serostatus to others, affording transport to clinics and co-morbidities were key age-related barriers to ART access. Age-related facilitators were financial and moral support from families and access to social grants | Limitations to this study include the small sample size and recruitment of participants who were already tested and linked to care, reducing the generalisability of the findings. Moreover, there may be other barriers or difficulties relating to not testing, late testing, and failing to attend care services that the study was unlikely to identify due to the sample population | |

| Schatz et al., 2022 (South Africa) [84] |

n = 161, PLWH > 40 years Community |

Focus group discussions | Participants reported fewer negative consequences of discloser in 2018 compared to 2013. Participants reported positive outcomes such as building trust, and greater support with adherence and medication collection | A limitation of the study is that participants in the 2013 focus group were different to those in 2018, which may have influenced the findings | |

| Contreras-Macias et al., 2020 (Spain) [73] |

n = 19 M = 69.4 years Outpatient |

Data were obtained from medical records, the electronic prescription programme, and the outpatient dispensing programme | Medication Regimen Complexity Index (MRCI), The European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) guideline of “Selected Top 10 Drug Classes To Avoid (Top-10-A) in elderly PLWHIV”, and the STOPP-Beers criteria | Polypharmacy was reported in 84.2% (16) of participants and a Top-10-A potentially inappropriate prescription was evident in 47.4% (9) of participants. The most prevalent group of prescribed drugs were benzodiazepines, reported in 30% (6) of participants. 57.9% of participants were complex patients with a MRCI index above 11.25. A higher sum of STOPP-Beers criteria was identified in older patients. Analysis using the t-student test showed a statistically significant relationship between MRCI score and the sum of the STOPP-Beers criteria with increasing age (p < 0.05) | The generalisability of the study findings is reduced by the single-centre study design and small sample size. Moreover, the STOPP-Beers criteria were validated to non-HIV patients 65 years or older |

| Contreras-Macias et al., 2021 (Spain) [70] |

n = 428 M = 50 years (SD = 10.9) Outpatient |

Data were collected using the Capacity-Motivation-Opportunity pharmaceutical care model at routine follow-up appointments | Medication Regimen Complexity Index (MRCI) and the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire | Polypharmacy was identified in 25.9% (111) of participants, with 5.4% (23) being on 11 or more medications. A negative correlation between ED-5D and MRCI scores was identified (p = 0.0002). The relationship between co-morbidity and quality of life was statistically significant in the thyroid-mechanic (p = 0.002) and geriatric-depressive (p = 0.003) patterns | Although the study had a large sample size, the generalisability of the findings is limited due to the study being based at a single urban safety net hospital. Moreover, participants included in the study were those engaged in the care and cannot be generalised to patients who fail to attend care |

| Engelhard et al., 2018 (The Netherlands) [26] |

n = 331 (HIV positive) M = 51 years (SD = 11.2) Outpatient |

HRQOL was measured using a survey in a nationwide sample of PLWH. Data from studies in diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis were added | Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36-item Health Survey | The HIV sample had the lowest mental health score, with the odds of poor mental HRQOL being higher in HIV patients than other groups. The chances of poor physical HRQOL were similar in both the HIV and diabetes groups, but lower in the rheumatoid arthritis group. Poor physical HRQOL among PLWH was linked to a history of AIDS, longer time on combination ART and severe co-morbidity. Being of Sub-Saharan African descent and having CD4+ counts of less than 350 was linked to poor mental HRQOL | A limitation of this study is that comparing HRQOL between different datasets may lead to findings resulting from other unmeasured factors and not the diversity of the diseases. Socioeconomic status, substance use, and sexual orientation were potential confounders that the study was unable to adjust for, due to inconsistent recording across data sets. Other limitations include that disease severity was not corrected for and participant samples of the other diseases were not a national cross-section of the patient populations |

| Moitra et al., 2011 (USA) [87] |

n = 16 M = 52.5 years (SD = 5) Community clinic |

Intervention study: 3–5 weekly 60-min acceptance-based behaviour sessions were conducted in groups of 3–5 participants. Discussions included overall acceptance-based principles, with each session being a stand-alone intervention | Acceptance-based behaviour therapy | 37.5% (6) participants found the groups to be very helpful and another 37.5% (6) found them to be moderately helpful, whilst 25% (4) found them minimally helpful. The study reported that qualitative observations suggested that the acceptance-based intervention strategies were well suited in the target population. A significant point made in every session was that avoiding the realities of living with HIV can lead to worsened health | The small sample size reduces the generalisability of the study. Group formats for each session may have impeded recruitment or undermined treatment acceptability for potential participants |

| Farahat et al., 2020 (Saudi Arabia) [47] |

n = 13 M = 50.1 years Hospital |

Data were collected retrospectively via medical chart reviews | Out of 130 participants that were included, 48.5% had one or more co-morbidities. Diabetes (15.4%), dyslipidaemia (10.8%), hypertension (10.8%) and lymphoma (10.0%) being the most common co-morbidities. An increase in co-morbidities was seen with an increase in age, with 40.7% of participants aged 60 years or older having three or more co-morbidities. Logistic regression analysis showed that only patients aged 50 years and older were more likely to have at least one co-morbidity | The generalisability of the study is limited by the small sample size. Also, the cross-sectional study design does not allow for causality analysis. Moreover, the study did not look at adherence and medical records were reviewed over an 18-year period, but several ART medication doses and durations were missing | |

| Guaraldi et al., 2017 (Italy) [28] |

n = 482 M = 53.9 years (SD = 6.9) Multidisciplinary clinic |

Patients were evaluated using two frailty tools as part of routine protocol | The Frailty Index and frailty phenotype | The frailty phenotype categories were: 51.9% pre-frail, 3.1% frail, and 45% robust. The mean Frailty Index score was 0.28±0.1. Falls and disability were linked to the Frailty Index but not the frailty phenotype | Due to the cross-sectional study design, the Frailty Index could not be assessed over time for the prediction of adverse outcomes. The lack of a HIV-negative control group and more objective tools to assess disability are further limitations |

| Owen et al., 2012 (UK) [71] |

n = 10 Median = 57 (52–78) years Hospital and community |

A biographical narrative approach was used to collect data | Findings showed that some participants were positive about ageing regarding it as progressing towards valued life goals, whereas others were more conflicted with future prospects. The individual's biographic relationship with the HIV epidemic history rather than their age influenced the differences in views of the future. Participants who were involved with HIV for longer were more likely to have interrupted careers due to illness, depend on state benefits, and have damaged social networks | The study findings were limited by the small sample size and recruitment location | |

| Date et al., 2022 (UK) [101] |

n = 164 Age: MOR: median = 59.5 (SD = 50–78) years; standard care: median = 60 (SD = 50–82) years Hospital |

Intervention study: Participants were randomized to either receive standard care or a Medicines Management Optimisation Review (MOR) | Medicines Management Optimisation Review toolkit, the University of Liverpool and Toronto General Hospital HIV drug interaction references, EuroQol five-dimension five-level (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire and visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) | Seventy participants were in the intervention group and ninety-four in the standard care group. Significantly more medicine-related problems were identified in the intervention group at baseline (p = 0.001) and 6 months (p = 0.001). There was a significant reduction in new medicine-related problems at 6 months in the intervention group compared to baseline (p = 0.001), with 44% being resolved at baseline and 51% at 6 months. There were no changes in HRQOL identified between groups or after the intervention. Participants and healthcare professionals found the MOR highly acceptable | The limitations to this study include the sample size, MORs required extra attendance to the clinic which may have precluded some participants, and as this was a feasibility study, it was not powered to measure the effectiveness of the intervention |

| Cho et al., 2018 (USA) [100] |

n = 36 Control group: M = 52 years (SD = 6.6) Intervention group: M = 51 years (SD = 13) Community |

Intervention study: Follow-up focus groups lasting 60–90 min were conducted using semi-structured discussion guides to allow participants to discuss their experiences and any issues with using the mVIP app, after the clinical trial had ended | mVIP (a web-app) | Focus groups revealed the five following themes related to predisposing factors: ease of using the app, being user-friendly, self-efficacy for management of symptoms, design preference of illustrated strategies with videos, and user-control. The four themes identified relating to enabling factors included: information requirements of symptom management, tracking symptoms, fit in lifestyle/living/schedule conditions, and more languages. The five themes reported relating to reinforcing factors included: communication with healthcare providers, information visualisation for each user, social networking, improvement in quality of life, and individual-tailored information quality | The generalisability of the findings may be limited due to the small sample size and the study sample being predominantly female. The app was only in English, therefore PLWH who are primary-Spanish speakers (an underserved population in the USA) were not included in the study |

| McNicholl et al., 2017 (USA) [38] |

n = 248 M = 57.8 years (SD = 5.1) Community |

Intervention study: Electronic medical records were used for medication reconciliations conducted by pharmacists | Pharmacist medication reconciliation, Beers and STOPP criteria, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, and the Veterans Ageing Cohort Study (VACS) Index | Hypertension (56%), depression (52%), COPD/asthma (48%), dyslipidaemia (39%), coronary artery disease (27%), and diabetes (22%) were the most common co-morbidities found. 35% of participants were taking 16 or more medications and 16% were taking more than 20. Beers and STOPP criteria were present in 156 and 134 participants, respectively. 25 contraindicated drug interactions were identified in 20 participants. A mean of 2.2 medications were stopped after medication reconciliation | A limitation to this study is that only a subsample of the clinic’s population was included due to limited resources. Underestimations of the pharmacist’s role in correcting potentially inappropriate prescribing may have occurred as only medications that can be corrected without collaboration and conducted during the clinic visit were measured. Interventions undertaken after the clinic visit was not included |

| Hojilla et al., 2021 (USA) [95] |

n = 584 M = 50.5 years Hospital |

Secondary analysis of data collected from a RCT of behavioural interventions for reducing unhealthy alcohol use in PLWH | Berger HIV stigma scale, the 12-item short form survey (SF-12) | African American participants reported higher personalised stigma scores and disclosure concerns compared to Caucasians. Both Hispanic/Latinx and African American participants were more likely to report having concerns around public attitudes towards PLWH than Caucasians. Woman were more likely to have increased negative self-image scores than men | Sample size limited the studies ability to evaluate correlates of HIV stigma within sex and race/ethnicity subgroups. The generalisability of the results is reduced as participants are an insured cohort with well managed HIV |

| McAllister et al., 2013 (Australia) [88] |

n = 335 M = 52 years Hospital |

Data were collected via anonymous surveys | 19.6% (65) of participants reported meeting pharmacy dispensing costs as difficult or very difficult, 14.6% (49) stated that due to pharmacy dispensing costs they have delayed purchasing medications, and 9% (30) reported stopping medication due to pharmacy costs. Amongst the 19.6% of participants finding difficulty meeting pharmacy costs, 29.2% (19) had stopped medication compared to 4.1% (11) of the remaining 270 patients (p < 0.0001). 5.7% (19) patients found travel to the clinic difficult or very difficult. Difficulty meeting pharmacy and clinic travel costs were independently associated with treatment cessation and interruption. 4.9% of patients reported being asked if they were having difficulty with payments for medication | The study findings are limited due to a single-site recruitment, participants being mostly male, and the lack of viral load data meaning that clinical significance of patient responses could not be determined | |

| Heron et al., 2019 (Australia) [31] |

n = 2406 (HIV-positive) and n = 648,205 (HIV-negative) Age: 45–64 years = 58.9%; 65–74 years = 10.3%; over 75 years = 2.3% Community |

Data were collected directly from MedicineInsight—a national primary care data programme | HIV-positive males were less socioeconomically at a disadvantage than HIV-negative males. The HIV-positive males in this cohort were at an increased risk of cancer, chronic kidney disease, anxiety, depression, and osteoporosis. Younger PLWH are at risk of premature onset of osteoporosis, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. A high prevalence of depression and anxiety was reported among HIV-positive males | A limitation to this study includes the potential of duplicated patient records on MedicineInsight as it is not linked across practices, thus if a patient were to visit more than one practice it would be entered as separate records | |

| McMillan et al., 2019 (Canada) [67] |

n = 716 Age range = 50–92 years and M = 59.2 (SD = 6.5) Outpatient clinic |

Health data routinely collected at the Southern Alberta Clinic that included laboratory, self-reported and clinician-reported results | The 29-item Frailty Index developed for Southern Alberta Clinic | The mean Frailty Index, 0.303 (± 0.128), did not differ between genders. It was not linked to current CD4 counts or nadirs. Frailty Index increased with age, ART duration, and duration since HIV diagnosis. Higher Frailty Indexes was seen in those who died compared to the survivors | The cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to draw conclusions of causality and directionality of the associations found. Another limitation is that the data used was collected for purposes other than calculating frailty, raising questions about accuracy and comprehensiveness |

| Kiplagat et al., 2019 (Kenya) [34] |

n = 57 Age: 50–59 years = 33.3%; 60–69 years = 49.2%; 70–79 = 17.5% Hospital and community |

In-depth interviews and four focus groups were used to collect data | Participants reported that co-morbidities and visiting multiple healthcare providers to manage their HIV as factors that impact their adherence to medication and clinic attendance. Other challenges included poor quality of facilities and patient-provider communications. Matched gender and older age for healthcare providers were reported as preferential by participants | The generalisability of the results is reduced as patients that had been lost to follow up or disengaged from care were not included, also participants included had been in care for at least a year, thus their views and experiences may have improved within that time | |

| Drewes et al., 2021 (Germany) [50] |

n = 897 M = 57 years (SD = 6.7) Community |

Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire | An Adapted version of the negative self-image subscale of the HIV Stigma Scale, the Silver Lining Questionnaire (SLQ), the OSLO 3 Social Support Scale (OSSS-3), and the UCLA Loneliness Scale | 18% (165) of participants reported having one or more falls in the 12 months prior to the study. A higher risk of falling was significantly associated with a lower economic status, living alone and being single. Having one or more co-morbidity increased the risk of falls by 2.5 times. Diseases of the central nervous system, heart disease, rheumatism, osteoporosis, and chronic pain were strongly associated with fall risk. In addition, internalised and experienced HIV stigma, social support, and loneliness were significantly related to a fall risk | The cross-sectional study design does not allow for causality analysis. The self-administered questionnaires may have led to bias on recall and social desirability. The study was not able to fulfil a probability sample of people ageing with HIV in Germany, thus reducing the generalisability of the results. Moreover, several potential risk factors for falls were not included in the analysis of this study, for example, specific medication, problems with balance or gait, or mobility |

| Vinuesa-Hernando et al., 2021 (Spain) [49] |

n = 30 Median = 71 Hospital |

Observational study using data from patient hospital medical records | The Medication Regimen Complexity Index (MRCI), the Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ), the Screening Tool of Older People’s Prescriptions (STOPP) and List of Evidence-baSed depreScriing for CHRONic patients (LESS-CHRON) crtieria | The most common co-morbidities were dyslipidaemia (70%), hypertension (66.7%), diabetes (43.4%), mental health disorders (26.7%). 30% of participants were taking 10 or more medications and 70% were taking more than five. 66.7% of participants were adherent to their medications. The MRCI score of concomitant medications was higher than the score of ART at 18.3 points and 5.1 points, respectively. Potentially inappropriate prescribing was present in 70% of participants according to the STOPP or LESS-CHRON criteria. Polypharmacy was significantly associated with meeting deprescribing criteria (p = 0.008) | Limitations to this study include the use of dispensing records as some information may be missing and the reliability of the information depends on the inputting physician. Furthermore, the small sample size limits the generalisability of the data |

| Rozanova et al., 2020 (Ukraine) [97] |

n = 123 Age = 55–81 years Community |

Data were collected via telephone surveys | Older PLWH with substance misuse disorders maintained their HIV and substance use disorder therapies over the Covid-19 lockdown, however, social support was highlighted to be critical to avoid treatment interruptions | A limitation to this study is that telephone surveys may have led to social desirability bias in participant answers | |

| Chayama et al., 2021 (Canada) [55] |

n = 42 Age = 50+ years Community |

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were used to collect data | Participants viewed co-morbidities as more urgent and prioritised them over HIV. Access to care for co-morbidities were hindered by stigma and discrimination. Participants reported difficulty concurrently managing their co-morbidities and HIV due to poorly managed co-morbidities. Concerns and frustrations were stated regarding the potential impact of ART on the development of co-morbidities. Treatment approaches that integrated services aided engagement with care | The study was only conducted with English speaking participants, thus the opinions and experiences of marginalised individuals such as immigrants and refugees were not collected | |

| Siefried et al., 2017 (Australia) [85] |

n = 522 M = 50.8 years (SD = 12.3) Hospital and community clinics |

A study-provided laptop was used by participants to complete a 204-item questionnaire | University of Liverpool HIV drug interaction database, and the Charlson co-morbidity Index | 77 (14.8%) of participants reported being linked to one or more HIV community organisations or peer support groups. The median duration on ART was 11 years. 78 (14.9%) of participants missed an average of one or more ART medications per month in the 3 previous months | The self-reported nature of the questionnaire for adherence may overestimate true adherence levels. Due to recruitment strategies, there is a risk of selection bias. The study findings are less generalisable to patients without subsidised healthcare, community supports, those with virological failure, females, and heterosexual males |

| Siefried et al., 2018 (Australia) [44] |

n = 522 M = 50.8 years (SD = 12.3) Hospital and community clinics |

Participants were given a 204-item questionnaire on dedicated laptops | 204-question questionnaire incorporating other existing or pre-validated instruments | 292 (55.9%) participants reported having co-morbidities. 392 (75.1%) participants took at least one concomitant drug. The daily pill burden for concomitant drugs was 6 and the ART daily pill burden was 1.2. Cardiovascular, antidepressants, over the counter, endocrine agents and anti-effectives were the most common classes of concomitant medication. 122 (23.4%) participants were taking at least 5 concomitant medications. The concomitant medication taken in 17 participants were contraindicated with their ART. Overall, 730 ART-concomitant combinations were identified as being a potential drug–drug interaction. 178 participants reported adverse drug reactions | A majority of the participants were male and in a country with subsidised healthcare systems, thus reducing generalisability to females and those in countries without subsidisation. The cross-sectional study design does not allow for causality analysis. The study did not collect data on concomitant medication dosage, therefore it cannot report whether dose adjustments would mitigate potential drug–drug interactions |

| Bogart et al., 2021 (USA) [94] |

n = 76 Median = 52.9 (SD = 12.9) Community |

Intervention study: Individually randomised group-treatment trial using cognitive behavioural therapy. Participants were clustered into groups. Semi-structured interviews were conducted post intervention | Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) bottle cap | The intervention group showed improved adherence compared to the control group (electronically monitored: p = 0.06; Self-reported: p = 0.02). There was significantly lower medical mistrust amongst the intervention group compared to the control group (p = 0.02) | Generalisability of the study findings are reduced due to convenience sampling at one community site and the small sample size |

| Harris et al., 2020 (USA) [64] |

n = 35 M = 58.3 years (SD = 5.4) Community and hospital |

Data were collected through surveys, interviews, and focus groups | The Berger HIV Stigma Scale, Perceived Stress Scale, Engagement with Health Care Providers Scale, and the Composite of Engagement in HIV care | 54.3% of participants were reported to be moderately engaged in care. The overall stigma in participants were high and participants were reported to be moderately stressed. There was a significant correlation between engagement in care and the stigma subscales, including negative self-image stigma (p = 0.03). Perceived stress was also associated with overall stigma, disclosure stigma, personalised stigma, negative self-image stigma, and public attitudes stigma. Race was highlighted as an additional cause of stigmatisation among African Americans | Limitations include data collected from surveys being self-reported, and items related to engagement in care were not based on reviews of medical charts. Self-reports may have led to bias on recall and social desirability. The small sample size limits generalisability |

| Mao et al., 2018 (Australia) [37] |

n = 98 Median = 51.5 years (26–65) Community |

Intervention study: A 6-week randomised SMS reminder intervention for ART adherence was conducted, followed by a mixed-method evaluation consisting of one-to-one interviews and a self-completed online survey | SMS reminders to mobile phones | The most common reasons for previous ART interruption were experiencing side effects and attending to other life priorities. There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and control arms at the end of the SMS campaign. A common suggestion for improvement of the intervention was that it should be tailored to each individual's needs and synchronised with their dosing regimens. The SMS campaign had several positive responses, describing impacts beyond ART adherence | The small sample size may reduce generalisability of the findings and limits the ability to find differences between the experiment groups. The cross-sectional mixed methods evaluation does not allow causal conclusions to be drawn. Moreover, evaluation consisted of self-reported data |

| Jiménez-Guerrero et al., 2018 (Spain) [77] |

n = 242 Median = 57.5 years (54–62) Hospital |

Data from electronic clinical records were used with a computer system (Diraya) to identify home treatment and an application for outpatient dispensing (Farmatools). Interactions were identified using four independent prescribers, product specification and an online database (http://www.drugs.com) | http://www.drugs.com | 61% (148) of participants were receiving concomitant treatment and 243 potential interactions were detected among 110 participants. 46 of the interactions were considered severe, whilst 197 were moderate. 76% (35) of the severe interactions were associated with boosted protease inhibitors. Statins and inhaled corticosteroids caused most severe interactions | The retrospective nature of the study could be a limitation, however, being merely descriptive, it may be considered irrelevant. Another limitation could be that over the counter and herbal medicines were not included |

| Knight et al., 2018 (South Africa) [35] |

n = 23 PLWH ≥ 50 years Community |

In-depth semi-structured interviews | Participants received care for both HIV and other conditions provided by different healthcare professionals and at different health facilities. Older PLWH and non-communicable diseases experience several physical and structural barriers to accessing care. These difficulties can worsen health outcomes | A limitation to this study is that recruitment was conducted via referrals from the HIV service, thus this may have led to participants with more or less barriers being missed | |

| Halloran et al., 2019 (UK/Ireland) [14] |

n = 698 PLWH ≥ 50 years and 374 PLWH ≤ 50 years 304 HIV-negative participants≥ 50 years old Hospital |

Potential drug–drug interactions were analysed using two interaction checking tools. The Pharmacokinetic and Clinical Observations in People Over 50 (POPPY) study is a prospective, observational, multicentre study that collected data over a three-year period from 2013 to 2016 | The Lexicomp database and the Liverpool drug interaction database (wwwhiv-druginteractionsorg) | Polypharmacy was prevalent in 65.8, 48.1 and 13.2% in older PLWH, younger PLWH and the HIV-negative group, respectively. This reduced to 29.8% of the older group and 14.2% of the younger group when ARVs were excluded. 36.1% of older PLWH, 20.3% of younger PLWH and 16.4% of the HIV-negative group had a prevalence of ≥ 1 PDDI involving non-ARV medications. The prevalence of ≥ 1 PDDI between ARV and non-ARV medication was 57.3% in older PLWH and 32.4% in younger PLWH | One limitation of this study was a lack of data on dosing information of most medications, leading to some interactions being overestimated. Another limitation is that the medication lists were self-reported by participants, which may have been under-reported. Lexicomp is a sensitive interaction checker and some of the interactions flagged may not be clinically relevant in daily practice |

| John et al., 2016 (USA) [32] |

n = 359 Median = 57 years (50–80) Hospital |

The following four domains were evaluated using a questionnaire: social support, physical health and function, mental health, and behavioural and general health | The Lubben Social Network Scale-6, the Social Provisions Scale, the UCLA 8-item Loneliness Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9), the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7, the Breslau 7-item PTSD screen, and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment | Participants experienced the burden of ageing related conditions over the domains evaluated. Nearly 60% reported mild symptoms of loneliness, 50% showed low social support, 41% had a fall in the last year and 34% met the criteria for possible mild cognitive impairment. Participants 60 years old or over had higher frequencies of balance issues compared to the group aged 50–59 years old. Fewer participants reported "very good" or "excellent" HRQOL in the 50–59 years old age group compared to the older group | The cross-sectional study design meant that changes were not measured over time. The findings may not be generalisable as the participants were largely male and from one city. Patients in long-term care facilities were not included. Most of the participants were diagnosed over 10 years prior, thus results may not be generalisable to newly diagnosed older PLWH |

| Townsend et al., 2007 (USA) [63] |

n = 58 M = 51.5 years (SD = 8.8) Hospital |

Data were collected using electronic medical records | Findings showed a non-significant correlation between viral loads and 6-month pharmacy medication refill-based adherence (r = 0.1). Adherence rates lower or equal to 70% led to CD4+ levels progressively declining. AIDS-related events incidence or past ARV experience did not significant affect the distribution of participant CD4+ levels or adherence | Limitations to this study include that pharmacy refill data was used to measure adherence as patients may have collected their medications but not taken them, the small sample size, and short study duration | |

| Levy et al., 2017 (USA) [36] |

n = 7018 Median = 50 years (39–57) Hospital and community |

Electronic medical records were used for data collection | Half of the participants reported having hypertension, 48% had dyslipidaemia, and 35% had obesity. A higher prevalence of co-morbidities was seen in older PLWH (p < 0.001). Hypertension was reported more in black patients, diabetes and obesity were reported more in female and black patients, and dyslipidaemia was reported more in male and white patients (all p < 0.001). Metabolic co-morbidities were associated with controlled immunovirological factors, longer time since HIV diagnosis, and a greater duration of ART | Limitations to this study include the cross-sectional study design does not allow for temporality or causality analysis, electronic medical records may have missing information, thus this may affect the results. Information on ARV adherence was not collected | |

| Gimeno-Gracia et al., 2014 (Spain) [76] |

n = 130 M = 56.7 years (SD = 6.2) Hospital |

Data were collected from out-patient pharmacy records at a University Hospital in Spain | At the end of the study, 90% of participants had an undetectable viral load and 58% had a CD4 count over 500 cells/mm3. Treatment that was based on protease inhibitors were used by 51.5% of older patients and 54.4% of the younger patients, whilst nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors were used by 43.8 and 39.8%, respectively. The older group used treatments with abacavir more frequently (p = 0.054) and with tenofovir less frequently (0.105) compared to the younger group | Due to the retrospective nature of this study, some data was incomplete. Also, the varying number of years since diagnosis among patients could have influenced their degree of adherence, the ART received, etc. | |

| Gimeno-Gracia et al., 2016 (Spain) [72] |

n = 119 Median = 52 years (51–56) Hospital |

Data were collected retrospectively to compare polypharmacy, percentage of patients that collected each therapeutic drug class, and the median duration of each drug class between older PLWH and the general population | A higher percentage of HIV-positive males had polypharmacy than males from the general population (8.9 vs 4.4%, p = 0.01). This was also true for females from each group, with older and younger groups having 11.3 and 3.4% of polypharmacy, respectively (p = 0.002). HIV-positive participants recieved more gastrointestinal drugs, analgesics, anti-infectives, central nervous system (CNS) agents, and respiratory drugs than the general population. No differences was observed between both groups for cardiovascular drugs. HIV-positive participants had a higher estimated number of treatment days than the males in the general population for CNS agents (p = 0.02), anti-infectives (p < 0.001) and more were receiving sulphonamides (p < 0.001), quinolones (p = 0.009) and macrolides (p = 0.02) | Generalisability of the study is reduced due to single-site recruitment and only a small number of female participants being included | |

| Greene et al., 2014 (USA) [13] |

n = 89 (HIV positive) Median = 64 years (60–82) Community |

Structured interviews were used to obtain demographic data, HIV history and co-morbidity data. Medication lists were reviewed during interviews to obtain medication usage information. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire before the interview with all their prescribed and over-the-counter medication | Lexi-Interact drug interaction software, Beers criteria 2012, and the Anticholinergic Risk Scale | Common co-morbidities amongst the participants were identified as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and depression. An average of 13 medications (2–38) were taken by PLWH, with only an average of four being ARVs, whereas non-HIV participants took an average of six (3–10) medications. There was at least one potentially inappropriate medicine prescribed in 46 (52%) of PLWH. Ten (11%) of the HIV participants had a Category X (avoid combination) interaction and 62 (70%) had at least one Category D (consider modification), with a third of these interactions being between two non-ARV medications. Fifteen (17%) PLWH were identified as having an anticholinergic risk scale ≥ 3 | The study population consisted of highly educated, Caucasian, men who have sex with men, therefore the findings may be less generalisable. The participants were also diagnosed for an average of 20 years, so the data may not be generalisable to older patients diagnosed more recently. Information about dosing was not obtained, therefore drug–drug interactions may have been overestimated, although the findings are consistent with other studies |

| Greene et al., 2018 (USA) [68] |

n = 356 Median = 56 years (53–62) Hospital |

Survey data were collected at two clinics to assess participants social, physical, mental, and cognitive health | The UCLA eight item loneliness scale, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, the Lubben Social Network Scale, and the Patient Health Questionnaire | Symptoms of loneliness was reported in 58% of participants, with the majority having mild loneliness. Lonely participants were more likely to have depressive symptoms, poor or fair HRQOL, have fewer physical supports, be current smokers or at-risk drinkers and/or drug users | The study participants were predominantly male, urban, were 57% white, and had long durations since diagnosis, therefore generalisability is limited. As the study was cross-sectional, temporal relationships between loneliness and depression with HRQOL and functional impairment was not examined. The HRQOL measure used was due to ease of administration but did not have a mental health measure. Also, a measure of stigma was not included, previous research has shown links between loneliness, stigma, and depression |

| Greene et al., 2018 (USA) [27] |

n = 77 surveyed and n = 31 focus groups Median = 58 years (50–77) Hospital |

Data were collected through focus groups and a survey | Findings highlighted the need for greater focus on the following: (1) the need for knowledge expertise in HIV and ageing, (2) a focus on determinants of health (e.g., marginal housing) and on medical conditions, (3) locating speciality services together, and (4) social isolation. These findings informed the creation and design of a multidisciplinary care model for PLWH (the Golden Compass programme) | A limitation of this study includes single-site recruitment and that generalisability of the findings is reduced as non-English-speaking participants were excluded | |

| Kuteesa et al., 2012 (Uganda) [86] |

n = 40 Median = 65 years (50–80) Hospital |

Individual in-depth interviews and focus groups were used to collect data. Observations of clinic interactions were also recorded | Key themes that emerged from the qualitative interviews highlighting distinctive healthcare needs in older PLWH were: difficulty disclosing (8%), stigma (43%), access to care (80%), delayed diagnosis and care-seeking (55%), quality of patient = provider relationship (75%), serodiscordance (20%), adherence support (25%), continuity of care (14%), end-of-life issues (13%) and other issues (20%). Participants reported experiencing stigma due to HIV and ageism. Concerns and anxiety regarding securing future healthcare and the lack of social services was expressed by participants. Problems with transport and food compromised adherence to ART for many participants | Limitations to this study affecting generalisability of the findings include recruitment from a limited geographic area and purposive sampling. Duration since diagnosis may have affected individual perspectives reducing generalisability of the findings as interviews did not indicate any participant to be newly diagnosed | |

| Philbin et al., 2021 (USA) [91] |

n = 59 M = 51 years Hospital and community |

In-depth interviews were used to collect data | Four main groups emerged from those interviewed, firstly, those with few long-acting injection related worries who received episodic injections, secondly, those who had regular injections and did not want anymore, thirdly, those with a history of injection drug use that were worried long-acting injections would trigger a reoccurrence, and lastly, those who currently inject drugs and have few worried around long-acting injections. Most participants who have a history of using injectable medication would prefer long-acting injectable ART, but participants with regular injections already and a history of injection drug use may not | The generalisability of the study findings are limited as they are based on the individual women's experiences and concerns, which may not be relatable to other subpopulations | |

| Katende-Kyenda et al., 2008 (South Africa) [75] |

n = 8999 (HIV-positive) 59.42% = 40–60 years and 1.58% ≥ 60 years National medicine claims database |

Data were collected directly from Interpharm Data systems and analysed. Prescriptions were used to determine if combinations of ARVs could cause possible drug–drug interactions | A clinical significance rating of potential drug–drug interactions as described by Tatro [Drug Interaction Facts 2005 St Louis, MO: Facts and Comparisons (2005)] | Participants received a mean of 2.36 ARVs per prescription. 960 drug–drug interactions were identified. Patients aged 40–60 years old had the highest number of ARV prescriptions and the highest number of drug–drug interactions. The most drug–drug interactions were seen between Indinavir and ritonavir, efavirenz and indinavir, efavirenz and lopinavir/ritonavir | A limitation to the study was that demographic and clinical information was not available on the database. Moreover, dosage information was also not supplied |

| Schreiner et al., 2019 (USA) [42] |

n = 103 M = 53.16 years (SD = 7.2) Community |

Data from a parent study examining physical activity patterns in PLWH was used for secondary analysis to evaluate treatment burden. The parent study used one-to-one interviews and entered responses directly into Research Electronic Data Capture | The Treatment burden Questionnaire-13, the Bullen and Onyx (2007) Social Capital Measurement Tool | Overall, a low level of treatment burden was reported among participants, however, 16% of participants reported experiencing high treatment burden. Treatment burden was significantly associated with number of chronic conditions (p ≤ 0.01) and social capital (p = 0.03). The most prevalent co-morbidities were hypertension, asthma, arthritis, diabetes, hepatitis B/C, and hyperlipidaemia. Remembering to take medications at certain times during the day, paperwork, the limitations linked to taking medications and maintaining a prescribed exercise regimen were items causing the highest treatment burden | Due to treatment burden not being the primary focus of the parent study, the reanalysis could not collect data on other variables of interest. The sampling technique used may have allowed for potential sampling bias, effecting the generalisability of the study findings. PLWH who are not insured or able to afford regular medical care were not represented in this study |

| Hastain et al., 2020 (USA) [29] |

n = 99 Median = 54 years (49–61) Community clinic |

Electronic medical records were used to evaluate ART simplification. Drug–drug interaction scores pre- and post- simplification were calculated. Concomitant medications were identified and evaluated for drug–drug interactions with pre- and post- simplification ART regimens | A drug–drug interaction incidence and severity score was developed and validated and the University of Liverpool's HIV Drug Interaction Checker | A median of 3 ART pills were taken a day. After simplification, the median number of ART pills taken was 2. Discontinuing protease inhibitors and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors occurred frequently and ART changes to integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimens were common. Average interaction scores reduced from 3 (1–6) to 1 (0–2) from pre- to post- simplification. The median number concomitant medication taken was 4.5 | The results may not be generalisable due to the sample size and recruitment from only one urban site. Also, not all ART simplification strategies and HIV medications could be thoroughly evaluated. As the study relied on the completeness and accuracy of electronic medical records, it is possible that over the counter, herbal and non-prescriptions items were not included. Lastly, the scoring system does not reflect the clinical significance of drug–drug interactions, for example, some interactions may need dose adjustments or close monitoring |

| Foster et al., 2009 (USA) [93] |

n = 24 Age range = 50–76 years (M = 57) Community |

Four focus groups were conducted, and supplementary data was obtained using two stigma instruments | The Stigma Impact of HIV scale and the Self-Perceptions of HIV Stigma Scale | Participants reported rarely or not experiencing stigma as they had not disclosed their HIV diagnosis to others. Stigma was reported by participants on the Internalised Shame scale. Qualitative data found four themes associated with stigma: (1) disclosure; (2) stigma experiences; (3) need for HIV/AIDS education; and (4) acceptance of the disease | Limitations to this study include that the focus group setting may have led to response-bias and participants who have been stigmatised not wanting to participate in group discussions, data on sexual orientation and mode of sexual transmission was not collected, and the time since diagnosis ranged broadly between participants, which may have affected perceptions on stigma and disclosure |

| Halkitis et al., 2014 (USA) [66] |

n = 180 M = 55.4 years (SD = 4.6) Community |

Data were drawn from Project Gold, a study of ageing HIV-positive men who have sex with men in New York City. Self-report data was collected for sociodemographic characteristics and clinical markers | The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Adherence Questionnaire, the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II, the HIV Stigma Scale | 109 (57.2%) participants reported at least one suboptimal adherence behaviour, with 36 (20%) missing doses in the 4 days prior to the assessment; 97 (48.3%) failing to take medication on schedule; 40 (24.1%) failing to follow instructions; and 33 (18.3%) missing doses in the weekend prior. Participants who missed a dose in the four days prior had experienced higher levels of HIV-related stigma compared to those who did not miss doses in those days. Depression and HIV-related stigma was associated with failing to take medication on schedule in the four days before (p = 0.05 and p = 0.01, respectively). These factors were also associated with failing to follow instructions on how to take ARVs | Data on adherence and psychosocial factors were collected using self-reports, which could have resulted in under-reporting. The cross-sectional study design limits the studies ability to find causal conclusions and evidence of a history of adherence behaviours and psychosocial behaviours |

| Shippy et al., 2005 (USA) [43] |

n = 160 Age: 50–59 = 85%; 60+ = 15% Community |

A survey was used to collect variables of interest | The increasing group of ageing PLWH are facing isolation from informal networks due to HIV stigma and ageism. 71% of participants lived alone. Family members and partners are critical for informal support, however, only a third of participants had a partner. 86% of participants used Medicaid | The cross-sectional study design does not allow for causality analysis among mental health indicators, social networks, and support needs of older PLWH | |

| Zepf et al., 2020 (USA) [54] |