Abstract

Background

Electronic clinical decision support tools (eCDS) are increasingly available to assist General Practitioners (GP) with the diagnosis and management of a range of health conditions. It is unclear whether the use of eCDS tools has an impact on GP workload. This scoping review aimed to identify the available evidence on the use of eCDS tools by health professionals in general practice in relation to their impact on workload and workflow.

Methods

A scoping review was carried out using the Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework. The search strategy was developed iteratively, with three main aspects: general practice/primary care contexts, risk assessment/decision support tools, and workload-related factors. Three databases were searched in 2019, and updated in 2021, covering articles published since 2009: Medline (Ovid), HMIC (Ovid) and Web of Science (TR). Double screening was completed by two reviewers, and data extracted from included articles were analysed.

Results

The search resulted in 5,594 references, leading to 95 full articles, referring to 87 studies, after screening. Of these, 36 studies were based in the USA, 21 in the UK and 11 in Australia. A further 18 originated from Canada or Europe, with the remaining studies conducted in New Zealand, South Africa and Malaysia. Studies examined the use of eCDS tools and reported some findings related to their impact on workload, including on consultation duration. Most studies were qualitative and exploratory in nature, reporting health professionals’ subjective perceptions of consultation duration as opposed to objectively-measured time spent using tools or consultation durations. Other workload-related findings included impacts on cognitive workload, “workflow” and dialogue with patients, and clinicians’ experience of “alert fatigue”.

Conclusions

The published literature on the impact of eCDS tools in general practice showed that limited efforts have focused on investigating the impact of such tools on workload and workflow. To gain an understanding of this area, further research, including quantitative measurement of consultation durations, would be useful to inform the future design and implementation of eCDS tools.

Keywords: General practice, Workload, Electronic clinical decision support, Consultations, Diagnosis, Risk

Introduction

UK General Practitioners (GPs) manage a high and rising workload of increasingly complex patient care with many competing demands to attend to within time-limited consultations [1]. This, and ongoing recruitment and retention challenges, has led to a GP workforce ‘crisis’ [2–5]. The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced further pressures on general practice, with associated back-logs of consultations, diagnoses, and referrals [6–9]; GP workload therefore continues to be an increasingly pressing issue for health professionals, patients and policy makers.

Clinical decision support (CDS) tools are used by health professionals to assist with clinical decision making in relation to screening, diagnosis and management of a range of health conditions [10–14]. Many CDS tools exist for use in primary care and more recently are being embedded in electronic form (eCDS) within practice IT systems, drawing directly on data within patients’ electronic medical records (EMR) for their operation [11, 15, 16]. Many Clinical Commissioning Groups and Primary Care Networks have supported the introduction of eCDS tools that facilitate diagnosis and expedite referral for certain conditions, such as cancer, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. For the purpose of this article, an eCDS tool is defined as any electronic or computerised tool which provides an output pertaining to a possible diagnosis and/or management of a health condition, using patient-specific information.

The workload implications of GPs using eCDS tools during consultations are unclear. One way of examining GP workload is to evaluate the duration of consultations [18], although that is only a single element of GP work, not including time taken for managing referrals, investigations, results, and general administration, undertaking training, and supervising colleagues [19, 20]. The duration of consultations and the ‘flow’ of patients through consulting sessions, however, provide key ways of measuring workload as these have an impact upon GPs’ levels of stress throughout the working day [21–23]. Understanding whether using eCDS tools impacts consultation duration and patient ‘flow’ through consulting sessions may help facilitate the implementation of eCDS tools into practice.

Here we aimed to establish if there is pre-existing evidence on potential workload, including impact on consultation durations, associated with the use of eCDS tools by health professionals in general practice and primary care. The objective of this literature review therefore was to identify the available evidence on using eCDS tools and analyse their impact on workload.

Methods

A systematic scoping review was undertaken to identify literature using the stages set out in the Arksey and O’Malley methodological framework, enhanced by more recent recommendations [24, 25]. This method enables examination of the extent, range and nature of research activity with an aim of identifying all existing relevant literature.

A broad research question was used: What is known from the existing literature about the use of eCDS tools by health professionals in general practice/primary care and the associated impact on workload and patient ‘flow’ through consulting sessions?

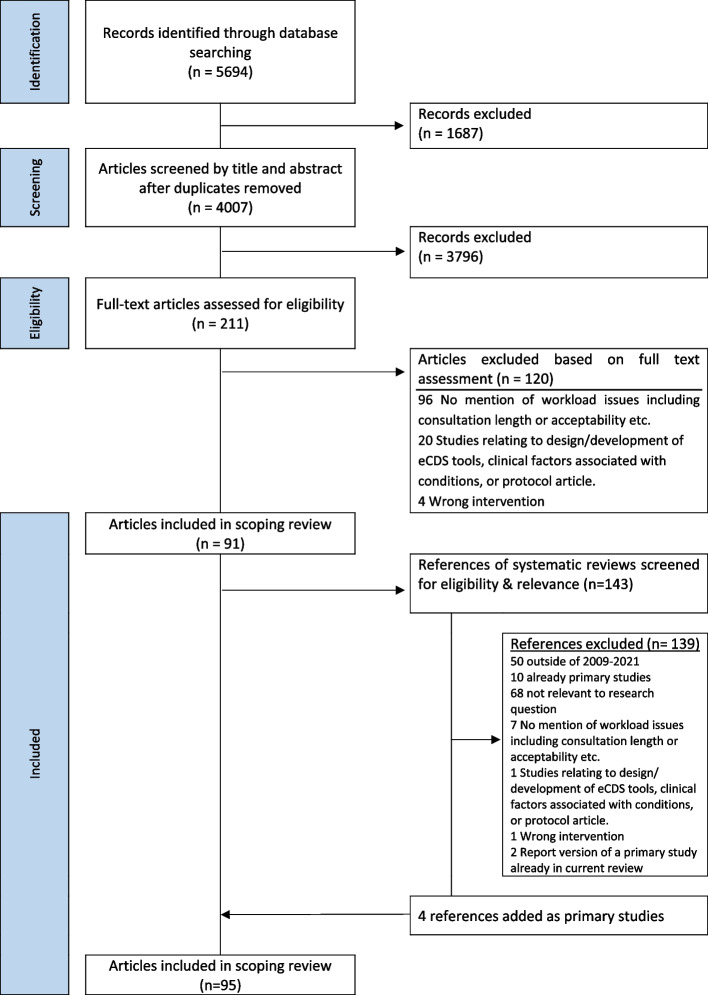

An initial scoping search was conducted using the databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), HMIC (Ovid) and Web of Science (TR). Keywords from titles and abstracts identified by this search, and index terms used to describe these articles, were identified (see Fig. 1). A second search across the same databases was then undertaken using the identified keywords and index terms, and studies collated for abstract and title screening to identify relevant full-text articles to be reviewed. The searches were conducted in September 2019 and updated in August 2021. The review extensively targeted articles in written English, and published in a ten-year period prior to the initial search date. This time period was selected in order to identify research on eCDS in the context of today’s general practice and primary care, and to manage review in context of available resources. A comprehensive search strategy and set of search terms used is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Search terms

The review aimed to identify research studies, reports and articles, including literature reviews, investigating the use of eCDS tools by all health professionals in relation to their impact on workload, such as consultation duration. The focus on ‘health professionals’ in primary care, not just on GPs, was intentional – we sought to identify all relevant contextual research. Therefore, studies concerning any type of health condition, eCDS tool, healthcare context within primary care or health professional were eligible. Both quantitative and qualitative evidence were included. Systematic reviews were included as studies in their own right, and thereafter the references of studies included in those reviews were screened for eligibility and relevance. Eligible and relevant references within a systematic review were then included in addition to those primary studies identified by the original searches. Studies relating specifically to the design or development of eCDS tools, and those focussing on clinical factors associated with specific conditions, were excluded. Protocol articles were excluded if the published results article of the same study were available.

Study selection was guided by: (i) an initial team meeting to discuss inclusion and exclusion criteria, (ii) all abstracts and full text articles were independently reviewed by two reviewers, and (iii) team meetings were held throughout the process to discuss and resolve conflicts of agreement. The following key information was gathered from the included studies: author(s), year of publication, study origin, study aims, type of eCDS tool in study, study population/context, methods, and outcome measures. EF, a health services researcher, classified the key findings into categories, defined as consultation duration-related (‘perceived’ or ‘objectively-measured’), or ‘other’ workload-related. The articles were organised using Covidence review software, then collated in a descriptive format using Microsoft Excel, and reviewed to summarise the key findings.

Results

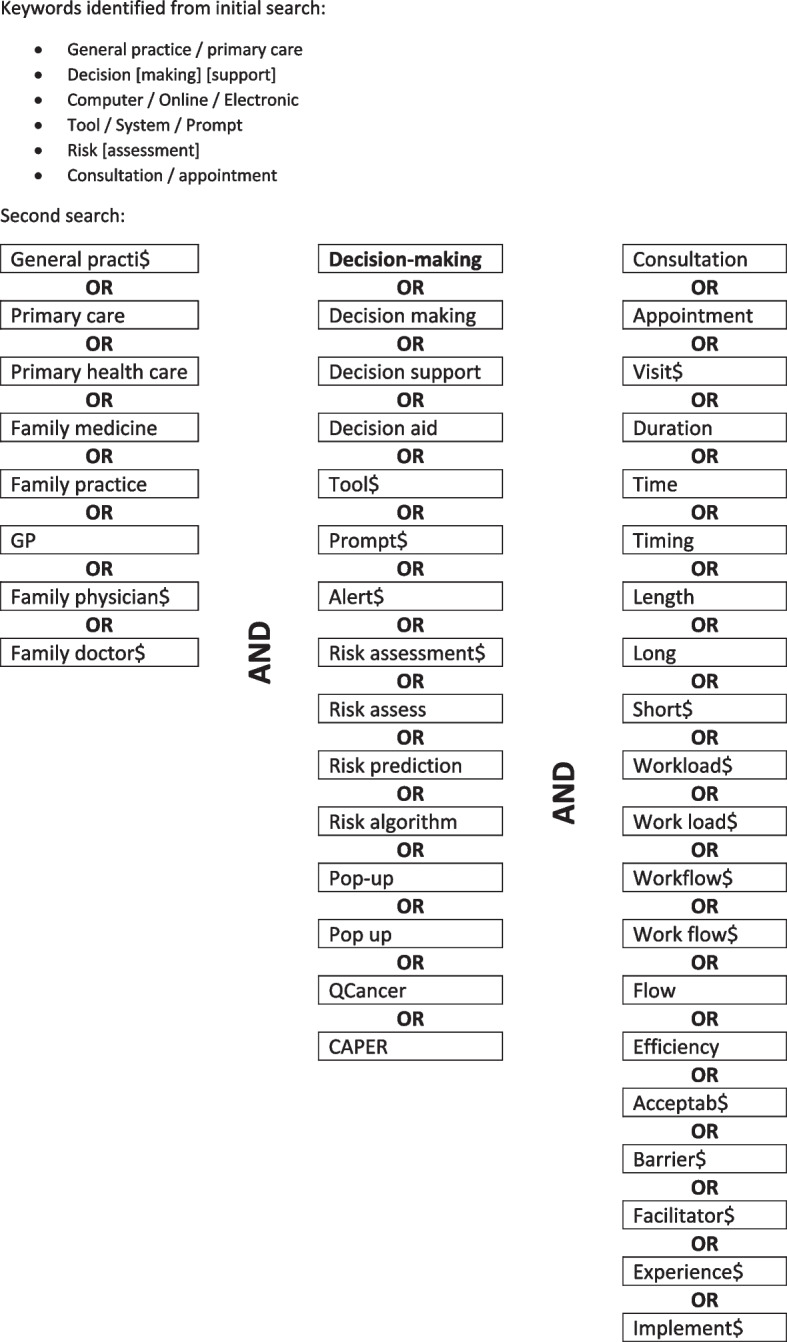

The database search yielded 5694 publications (4007 after removal of duplicates, Fig. 2). After screening titles and abstracts, 211 publications were selected for full-text screening. Of these, 120 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, resulting in 91 publications being included in the scoping review. Four of these articles were systematic reviews; screening of eligibility and relevance of references included in those reviews led to the inclusion of a further four articles. The total 95 included articles referred to 87 research studies.

Fig. 2.

Summary of the screening process

Description of included articles

All studies were conducted in high-income countries, with the exception of one from Sub-Saharan Africa. A third of the articles from the studies originated in the USA (36), with UK and Australian articles comprising another third (21 and 11 respectively). A further 18 publications originated in Canada and mainland Europe, with the remaining studies conducted in New Zealand (2), South Africa (2) and Malaysia (1). For most articles workload was not the main focus, with only 16 examining it either as a main focus or as one of the aims.

The most common clinical areas of focus among the eCDS tools studied were cancer risk assessment (15 articles), cardiovascular disease (11), and prescribing for various conditions (10). Other common clinical areas included: blood-borne viruses (3 articles), and various other long-term conditions (14 articles, including those on diabetes, chronic kidney disease, asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and hypertension). Smaller numbers focussed on tools for other conditions including: transient ischaemic attack and stroke, abdominal aortic aneurysm, respiratory infections, psychiatric disorders, skin conditions, hearing loss, and familial conditions (one or two publications on each). Some tools were also designed to support general delivery of care across a range of domains such as maternal and child health, occupational health, behavioural health, and geriatric home care.

A third of articles (31) utilised purely qualitative methods, almost all of which included interviews and/or focus groups with health professionals. One exception reported conversation analysis of audio- and video-recorded consultations and another study reported observations of consultations. Twenty-eight articles reported quantitative methods; 23 involved a survey of health professionals and/or analysis of EMR data or usage data from the investigated tool. The other quantitative articles included three randomised controlled trials and two observational studies. The remaining 28 articles utilised mixed methodologies. The majority of these involved either a survey of health professionals plus qualitative interviews/focus groups (n = 12) or an analysis of EMR/tool usage data in addition to qualitative interviews, focus groups and/or observations (n = 15). Four further articles were systematic reviews, two involving qualitative synthesis and one being a mixed-methods narrative review. All included articles are summarised in the data extraction table (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data extraction table

| Authors | Origin | Aims | Context | Methods | Outcome measures | Key findings of interest | Impact on time/workload |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad et al. 2010 [26] | Canada | To enhance understanding about computer-assisted health-risk assessments (HRA) from physicians’ perspectives regarding benefits and concerns/challenges |

Condition of focus: Domestic violence Setting: 1 family practice clinic Tool: Health Risk Assessment tool - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No, guides visit - User-driven: Physician - Risk score: No |

Qualitative interviews |

(1) What do you think of your experience with the HRA? (2) How would you describe its potential across various risks and visits? (3) Would you recommend such HRA in a family practice setting? 4) What factors are important for its implementation in a family practice setting? |

Theme 2: perceived risks & challenges (subtheme: length of visit) - Some expressed concern about the increase in length of the visit - Others managed the time pressure by offering follow-up visits or viewed the task of risk review as a professional obligation even if it meant increases in the consultation time - Follow-up visit offered in order to avoid “taking time away” from other waiting patients - ‘Patient readiness'—not always the right time to address in the visit |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed views |

| Arts et al. 2017 [27] | Netherlands | To investigate the effectiveness of a CDSS as measured by GPs' adherence to the Dutch GP guideline for patients with Atrial Fibrilation |

Condition of focus: Stroke prevention in AF Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS using antithrombotic guidelines - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Physician - Risk score: Yes |

Quantitative RCT |

Primary: Difference in the proportion of patients with AF treated in accordance with the guideline between the intervention and control groups Secondary: reasons GPs provided for deviating from the guideline and how they responded to required justification |

Limited evidence for effectiveness, attributed to low usage Reasons for low usage discussed in a separate qualitative evaluation, but included barriers relating to lack of time, too many alert notifications and tool functionality limitations |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: lack of time, too many alerts |

| Arts et al. 2018 [28] | Netherlands | To identify remediable barriers which led to low usage rates seen in RCT |

Condition of focus: Stroke prevention in AF Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS using antithrombotic guidelines - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Physician - Risk score: Yes |

Mixed: quantitative survey + focus group | Barriers and facilitators for CDSS use |

More than 75% of GPs answered the question: "What were the most important reasons for not opening the recommendations?" citing reasons relating to lack of time Many felt there was lack of time during the appointment to perform the suggested actions. Some GPs scheduled follow up appointments for this purpose |

Perception Impact on time: Increase |

| Baron et al. 2017 [29] | USA | To evaluate the value and feasibility of three examples of CDS relating to occupational health in five primary care group practices |

Condition of focus: Occupational Health Setting: Primary Care Tool: CDS using guidelines - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Physician - Risk score: No |

Qualitative:- interviews + observations |

Interviews: - physicians' daily work patterns - experience with EMRs and CDS - attitudes and practice regarding consideration of health factors encountered in a patient’s job - how patients' work data is collected in the EMR Observations: - workflow data through observations of clinic staff |

The amount of clinical time the CDS tools would require was a prominent concern 1 of 7 themes: clinician acceptance is affected by whether CDS adds or saves time |

Perception Impact on time: No conclusion |

| Bauer et al. 2014 [30] | USA |

To examine the attitudes and opinions of paediatric users’ toward the Child Health Improvement through Computer Automation (CHICA) system |

Condition of focus: Child Health Setting: Community paediatric clinics Tool: Child Health Improvement (CHICA) CDS for paediatric visits - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No, guides visit - User-driven: Physician & patient - Risk score: No |

Quantitative: survey + free text | General acceptability and satisfaction |

Critical opinions of CHICA were that it wasted time and money. This perception persisted in spite of informal time-flow studies in one of the clinics showing that CHICA did not create significant delays Approximately half of respondents reported that it did slow down clinic |

Perception and objective measure showed conflict Impact on time: Increase (perception), no impact (objective) Driving perception: lack of time, workflow disruption |

| Carlfjord et al. 2011 [31] | Sweden | To explore how staff at 6 Primary Health Care units experienced implementation of a tool for lifestyle intervention in primary health care |

Condition of focus: Preventive care Setting: PHC units Tool: CDS for lifestyle intervention & preventive services - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Patient-completed - Risk score: Unclear |

Qualitative: focus groups + interviews |

- Overall working situation coinciding with the implementation process - Experiences of implementation activities and the tool - How to address lifestyle issues with patients - Openness to innovations |

GPs' perception of workload already being too heavy and accommodating never-ending changes such as the lifestyle intervention tool may threaten independence and bring extra work |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: workload already heavy |

| Carlfjord et al. 2012 [32] | Sweden | Qualitative evaluation of the 2011 study to explore staff’s perceptions of handling lifestyle issues, including the consultation as well as the perceived usefulness of the tool |

Condition of focus: Preventive care Setting: PHC units Tool: CDS for lifestyle intervention & preventive services - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Patient-completed - Risk score: Unclear |

Qualitative: focus groups |

Staff responses to two scenarios: - How to handle the patient/consultation - Advice to give to another clinic considering implementing the tool |

Lifestyle issues tend to be forgotten when the workload is increasing, despite interest and awareness of its importance Many staff members found it difficult to initiate a conversation about lifestyle, particularly alcohol consumption, when the patient is seeking care for something else Time is too pressured to be focused on lifestyle/prevention especially in acute times/low resources |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: no time for preventive care |

| Chiang et al. 2017 [33] | Australia | To test the acceptability and feasibility of the Treat to Target CVD (T3CVD), an EMR-based CDS tool, for the evaluation of Absolute CVD Risk in general practice |

Condition of focus: Cardiovascular Disease Setting: 1 general practice Tool: CDS for CVD risk assessment - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Automatic, based on EMR data - Risk score: Yes, for patients with > 10% risk of CVD |

Qualitative interviews |

Acceptability and feasibility of the T3CVD tool, including GPs’ experiences with the tool in real-world clinical practice, under a framework of 3 themes: - patient control - clinical quality of care - technology capability/capacity |

GPs described how the ACVDR assessment pop-up necessitated additional time, often needing to arrange a follow-up visit if there was no time to discuss While the tool had capacity to save time by automating information provision rather than GPs manually accessing the existing CVD risk tool, it is potentially disruptive and adds to many existing pop-ups |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed views |

| Chiang et al. 2015 [15] | Australia | To explore the use of a cancer risk tool, which implements the QCancer model, in consultations and its potential impact on clinical decision making |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: General Practice Tool: QCancer risk tool - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes, for each of 10 cancers |

Qualitative: simulated consultations + interviews |

1. Coherence 2. Cognitive participation 3. Collective action 4. Reflexive monitoring |

Tool was easy and quick to use, but introducing the emotive topic of cancer caused anxiety. Risk output 'too confronting' to use in a consultation and could lead to a loss of control over the consultation and time being used to reassure which may lead to overrunning by 20-30 m GPs thought pop-up alerts would add to alert fatigue |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: impact on conversation |

| Crawford et al. 2011 [34] | Scotland | To understand primary care practitioners’ views towards screening for diabetic foot disease and their experience of the SCI-DC system |

Condition of focus: Diabetic foot disease Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for screening - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Unclear |

Qualitative interviews | Views on and use of decision support systems, specifically SCI-DC | The duplication of effort to complete the SCI-DC and then the GP IT system through which the practice receives remuneration is unnecessarily time consuming. Integration into GP IT systems is central to its adoption |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: stand-along system, double data entry needed |

| Curry et al. 2011 [35] | Canada |

To explore two issues in the implementation of CDS for Diagnostic Imaging: - Will physicians incorporate decision-support technology into their clinical routines? - Will physicians follow clinical advice when Provided? |

Condition of focus: Diagnostic imaging Setting: Family Medicine clinic Tool: CDS to guide decisions to order imaging - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative analysis of useage data + qualitative interviews |

Quantitative—usage by clinicians Qualitative—perceived effects of taking part in the study and challenges |

The largest challenge was perceived interference with usual work flows, specifically the interactivity between EMR and the CDS (perceived to be too slow, although measured as less than 1 s). The time for physicians to interact with CDS was also perceived to be too long Time taken to use tool (described in Methods) 2 min 15 s as follows: - 1 min to enter data, 5 s for CDS to check if appropriate - < 1 min for clinician to look at recommendation if not appropriate - 10 s to complete DI order if still required |

Perception and objective measure of time to use tool showed conflict Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: slow software, workflow disruption |

| Dikomitis et al. 2015 [36] | UK | To collect data on the (non)use of electronic risk assessment tools (eRATs) and on the experiences of using the tool in everyday practice |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: General Practice Tool: eRATs - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Qualitative interviews |

Normalisation Process Model: (1) interactional workability (2) relational integration (3) skill-set workability (4) contextual integration |

Interactional workability—GPs' reactions to the on-screen prompts was influenced by different factors: - the approach of the doctor - the GP’s clinical experience - time pressures in specific consultations Contextual integration—most issues related generally to new interventions being implemented: - GPs expected to multi-task within one consultation - constant time pressures - prompt fatigue is a risk if added to an already 'busy screen' and alerts may not be responded to - concern over workload for secondary care |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: lack of time |

| Duyver et al. 2010 [37] | Belgium |

To explore GPs' perceptions of feasibility and added value of the MDS-HC as a geriatric assessment tool and to investigate potential barriers and facilitating factors regarding the implementation of this tool in an ambulatory community setting |

Condition of focus: Geriatric care Setting: General Practice Tool: Home care assessment tool - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Quantitative: survey + free text |

Four assessment areas: (1) technical acceptability (2) clinical relevance of the tool (3) management and optimization of health care planning (4) valorisation of the role of the GP |

Free comments from GPs: - Long and fastidious encoding - CDS was too long, added admin workload - Excellent concept, worth making easier and shorter to use |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: slow software |

| Eaton et al. 2012 [38] | USA |

To examine Abdominal Aortic Anneurysm (AAA) screening ordering in an academic primary care internal medicine clinic that uses physician reminders based on real-time CDS for preventive screening and to identify why screening ordering rates vary among providers |

Condition of focus: Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) Setting: Primary Care clinic Tool: CDS for AAA screening - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Quantitative: records review |

Features of the first visit during the study: - visit date - visit type (general medical examination vs. other type) - provider role (staff physician vs. other) - provider gender - was AAA screening ultrasound was ordered during the visit |

Visit time (based on the fixed length of different visit types) is an important determinant for preventive screening Patients more likely to have screening ultrasound ordered during longer medical examinations, which usually has more time allotted (40 min) and often has a disease-prevention component During longer medical examinations, 24% of eligible patients had the recommended AAA screening ordered, compared with only 6% during shorter visits |

Objective measure of time for whole consultations (via proxy of visit type) Impact on time: Increase |

| Laforest et al. 2019 [39] | UK |

To review the tools available, clinician attitudes and experiences, and the effects on patients of genetic cancer risk assessment in general practice |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: General Practice Tool: range of risk assessment tools, including web-based, risk-stratification, and paper-based - Embedded/linked with EMR: Range - Interruptive alert: Range - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Range |

Systematic review |

1. What tests/tools are available to identify increased genetic risk of cancer in general practice? 2. What are clinicians’ attitudes towards Screening/testing population groups for genetic cancer risk? 3. What are the levels of patient knowledge, satisfaction, and anxiety in relation to tests and communication by a GP about cancer risk? 4. What are patients’ risk perceptions following screening/testing for genetic cancer risk in primary care? 5. What are the outcomes of referrals following genetic cancer risk identification in general practice? |

5 studies examined GP attitudes: - Owens et al. (43): some providers concerned over the time needed to counsel patients who were newly determined as at high risk, and regarding liability for not successfully providing risk counselling - Wu et al. (45): physicians at two primary care clinics felt they were already collecting high-quality family histories and that the tool would negatively impact their workflow. Physicians believed that patients would redirect discussions away from physician priorities and, instead, focus on tool recommendations. However, post-implementation, 86% of physicians found the tool improved their practice, and none reported adverse effects on workflow GPs were worried about the impact of risk assessment on patient anxiety, particularly if discussions with whole families would be required. GPs were concerned about their ability to explain risk and implications in short, routine appointments |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed views |

| Fathima et al. 2014 [40] | Australia |

To systematically review randomized controlled trials evaluating effectiveness of CDS in the care of people with asthma and COPD and to identify the key features of those systems that have the potential to overcome health system barriers and improve outcomes |

Condition of focus: Asthma & COPD Setting: Primary care Tool: range of CDS systems, including prevention & management, providing guidelines - Embedded/linked with EMR: Range - Interruptive alert: Range - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: No |

Systematic Review (qualitative syntheses) |

Assessment of intervention effects 1. Type of CDS intervention 2. Effectiveness of CDS: - Clinical outcomes - Healthcare process measures - User workload and efficiency outcomes - Relationship-centred outcomes - Economic outcomes - Use and Implementation outcomes |

Workload and efficiency outcomes assessed included asthma documentation by ED doctors, consultation time, time for disposition decision in the ED, and user knowledge These were assessed as the primary outcome by two trials, of which one trial showed significant improvement in rate of asthma documentation. The other trial did not show any effect from the use of CDS on the time taken to make a disposition decision 83% of studies of CDS tools which were stand-alone in design had favourable clinical outcomes, compared with 38% of embedded designs. This may be due to alert fatigue and too low a threshold for alerts being generated Low evidence provided by studies re user workload & efficiency. One RCT in a hospital ED measured consultation time as a marker of workflow efficiency, finding no significant difference in consultation time between the intervention group compared with control |

Objective measure of time for whole consultations (1 study in a systematic review) Impact on time: neither increase nor decrease |

| Finkelstein et al. 2017 [41] | USA | To implement a comprehensive informatics framework to promote breast cancer risk assessment and chemoprevention in primary care that was informed by potential user feedback (usability testing to determine barriers and facilitators affecting the toolbox use by providers) |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: Primary care Tool: Breast cancer risk assessment & chemoprevention - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Clinician & patient - Risk score: Yes |

Qualitative interviews | Ease of use, content, navigation | Ease of use: notifications were noted to be too time consuming to process |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: Lack of time |

| Fox et al. 2014 [42] | USA | To evaluate adherence to an evidence-based Chronic Kidney Disease computer decision-support checklist in patients treated by Primary Care Physicians compared with usual care at a single site |

Condition of focus: Chronic Kidney Disease Setting: Primary care clinic Tool: CDS checklists for CKD - Embedded/linked with EMR: Unclear - Interruptive alert: No, guides visit - User-driven: Clinic staff - Risk score: No |

Quantitative records review | Clinical measures of CKD management |

Comment that the checklist was used to create a priority and incorporated into workflow so that CKD was treated appropriately. This is a step above a simple alert at the point of care and circumvented alert fatigue The 'extra time' needed for PCP to improve CKD care did not seem to adversely affect other areas of preventive care |

Perception Impact on time: Neither increase nor decrease Driving perception: did not take time away from other areas of preventive care |

| Gill et al. 2019 [43] | USA | To examine the impact of Point Of Care CDS on diabetes management in small- to medium- sized independent primary care practices that had adopted the PCMH model of care |

Condition of focus: Diabetes Setting: Primary care practices Tool: CDS for diabetes management - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No, guides visit - User-driven: Automatic - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative analysis of EMR data + qualitative interviews |

Quantitative: Clinical measures of diabetes management Qualitative: Barriers to and facilitators of successful implementation of CDS that achieved optimal diabetes management |

Barriers impeding implementation of the CDS included time and reimbursement in light of the need for time to implement team-based care, not specifically regarding the impact of the CDS on visit lengths |

Perception Impact on time: No conclusion |

| Green et al. 2015 [36, 44] | UK | To explore GPs’ experiences of incorporating Risk Assessment Tools (RATs) for lung and bowel cancers into their practice and to identify constraints and facilitators to the wider dissemination of the tools in primary care |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: General Practice Tool: paper-based RATs - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: Yes |

Qualitative interviews | GPs' experiences of the implementation process and their use of the RATs in practice | A minority of participants did not feel RATs added to practice: "I’m not sure it fits into the consultation in a natural way of making a decision about the management of that patient. It’s one more thing to fit into a busy ten minute consultation” |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: workload already heavy |

| Gregory et al. 2017 [45, 46] | USA | To examine asynchronous alert-related workload in the EMR as a predictor of burnout in primary care providers (PCPs), in order to inform interventions targeted at reducing burnout associated with alert workload |

Condition of focus: Generic Setting: Primary care Tool: inbox-style EMR alerts - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative survey + focus groups |

Subjective alert workload (perception of time available to complete tasks) Objective alert workload (actual hours spent) Burnout (scale) |

Quantitative: subjective alert workload was positively related to 2/3 dimensions of burnout. Subjective alert workload was also generally predictive of burnout, whereas objective alert workload was not This suggest that it is the perception of alert burden that predicts burnout, rather than the actual amount of time spent attending to alerts Qualitative: time spent managing alerts was a major theme in focus group discussion and survey comments |

Perception and objective measure of workload showed conflict Impact on workload: Mixed views |

| Harry et al. 2019 [47] | USA | To identify adoption barriers and facilitators before implementation of CDS for cancer prevention in primary care |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: Primary care clinics Tool: CDS for cancer prevention & screening - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No, guides visit - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: Unclear |

Qualitative interviews |

1. Factors that facilitate or hinder key informant support for the intervention 2. Key informant knowledge and beliefs about the intervention and tension for change 3. The relative advantage(s) of the intervention compared with other interventions currently available in the EMR 4. Relevant organizational culture norms and values related to cancer prevention and screening 5. Factors that may foster adoption from a key informant perspective 6. Related external policies and incentives 7. Implementation climate |

PCP time limitations were a major concern. PCPs are being asked to do more with less time, including seeing more patients in a day, making some PCPs wonder how to fit the CDS into the visit It was perceived to be 5–10 min to use the tool, which would add time pressure as appointments are usually 'already 20 min behind' However, some same informants who mentioned time constraints also said that this would only be a limitation until PCPs learned the CDS tools |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: Lack of time |

| Hayward et al. 2013 [48] | UK | To understand how GPs interact with prescribing CDS in order to inform deliberation on how better to support prescribing decisions in primary care |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for prescribing - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative analysis of useage data + conversation analysis |

Timing of computer tasks and utterances Prescribing alerts and responses Conversation analysis |

Total mean duration of consultation: 9 min 3 s - time before prescribing = 5 min 47 s - during prescribing = 1 min 47 s - time after prescribing = 1 min 30 s Timing of alerts was problematic as they interrupt in order to correct decisions already made rather than to assist earlier deliberations. By the time an alert appears the GP will have potentially spent several minutes considering, explaining, negotiating, and reaching agreement with the patient, possibly given instructions, and printed information about treatment. An alert in the final seconds of the task increases the probability of it being ignored |

Objective measure of time of whole consultations Impact on time: neither increase nor decrease |

| Henderson et al. 2013 [49, 50] | UK |

To determine uptake of online diagnostic CDS and impact on clinical decision-making and patient management and to elicit users’ views of utility |

Condition of focus: Generic Setting: General Practice Tool: online diagnostic CDS - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Mixed: focus group + survey | Whether and how well the system had been embedded in everyday practice, based on the evidence available from the focus groups and post-use survey |

Low usage reported There was conflict at the organisational level, as agreement to participate in the study had been primarily by practice managers, while CDS use was to be by clinicians. This was linked to the major issue of no time having been identified for clinicians to use the system during a consultation Searches took 4 min within a 10 min consultation: ‘We have so many things thrown at us…the PCT telling us to do this and that you can get a little overwhelmed.’ (GP) |

Perception and objective measure of time to use tool Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: workload already heavy |

| Heselmans et al. 2012 [51] | Belgium | To assess users’ perceptions towards the implemented EBMeDS, the investigation of user interactions with the system and possible relationships between perceptions and use |

Condition of focus: Generic Setting: Family Practice Tool: CDS for a range of conditions - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative survey + qualitative interviews |

Qualitative: factors that may account for acceptance and use of EBMeDS Quantitative: computer-recorded user interactions with the system over evaluation period of 3 months to assess the actual use of the system |

Although majority of FPs were positive about the system, the most important reasons to neglect reminders related to the number of reminders and lack of time to read them (44%). However, 35% reported they could perform their tasks faster using the system Quantitative analysis of physicians’ log files:- Study measured number of seconds for a reminder to be closed after appearing, but this is only referred to in the discussion: - reminders open for less than 3 s were assumed to have been 'clicked away' (ie ignored) - 49% of alerts were open for < 2 s and 32.5% open for < 3 s which suggests that sensitivity threshold may have been too low |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed views |

| Hirsch et al. 2012 [52] | Germany | To evaluate the uptake of an interactive, transactional, and evidence-based library of decision aids and its association to decision making in patients and physicians in the primary care context |

Condition of focus: Range Setting: Primary Care Tool: CDS for a range of conditions, including CVD, AF, CHD, diabetes and depression - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Quantitative survey |

Which module was used and how detailed the steps of the shared decision making process were discussed using a four point scale Physicians were asked who made the decision at the end of the consultation, and for a subjective appraisal of consultation length (“unacceptably extended”, “acceptably extended”, “neither nor”, “shortened”) |

Subjective appraisal of consultation length: in 8.9% of consultations physicians said that they were “unacceptably extended” by the CDS, 76.3% of consultations were “acceptably extended”, 14.2% “neither nor”, and 0.5% were “shortened” Majority of physicians stated that the consultation length was either not extended or ‘acceptably’ extended Log files analysis reported average consulting time was 8 min, so use of CDS was therefore not extending the usual 10 min appointment slot |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed views |

| Holt et al. 2018 [53] | UK |

To identify the barriers to automated stroke risk assessment linked to invitations and screen reminders in primary care (AURAS-AF) |

Condition of focus: Stroke prevention in Atrial Fibriliation Setting: General Practice Tool: stroke risk assessment - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Mixed: quantitative analysis of useage data + interviews |

Quantitative: coded data indicating the responses to the screen prompts Qualitative: Researcher-led issues around AURAS-AF, and allowed people to express their own experiences and priorities |

Time available and the patient's own agenda dictated whether the alert was used to introduce the topic into the consultation. In some cases, GPs recognised that the timing was not right to initiate a discussion GP estimated the alert added 5–10 min more on the consult ('so you leave it') |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: impact on conversation |

| Hoonakker et al. 2012 [54] | USA | To examine barriers, and possible improvements to a tool, HeartDecision (HD) |

Condition of focus: Cardiovascular disease Setting: Primary care Tool: cardiac risk assessment - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Mixed: quantitative time study + survey + qualitative interviews + observations |

A stop watch was used to measure the time the physicians spent on the different pages of the tool Survey: additional information about the need for such tools, use of the tool, barriers against its use, facilitators, and possible improvements |

The time study showed that on average, physicians spent 13 min using the tool, which is 'too long' for a regular patient visit, which lasts on an average 10 min |

Objective measure of time to use tool Impact on time: Increase |

| Kortteisto et al. 2012 [55] | Finland | To assess and describe in depth the specific reasons for HPs using or not using the eCDS in primary care |

Condition of focus: Generic Setting: Primary care clinic Tool: CDS for a range of conditions - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Mixed: focus group + survey |

Focus groups: general ideas about the eCDS, experiences of the use, practical problems, advantages /disadvantages for work, barriers to use and facilitators, and development issues Survey: system’s capacity and quality, as well as its perceived usefulness and ease of use |

Common barrier was busy practice in primary care ‘When I am busy, I don’t look for anything really.’ ‘Nothing more than simply doing what I have to do.’ Within 'functionality', majority of clinicians reported it was 'rapid enough' Within ‘usefulness’, drug alerts 'motivate' but 'take time' and 'requires more time for paperwork' |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed views |

| Krog et al. 2018 [56] | Denmark | To explore facilitators and barriers to using the eMDI in psychometric testing of patients with symptoms of depression in Danish general practice |

Condition of focus: Depression Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for diagnosis/monitoring of patients with depression - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Qualitative interviews | Determinants for using the eMDI in relation to the GPs’ capability, opportunity and motivation to change clinical behaviour |

eMDI was a 'timesaver' compared to the paper version because of cutting out need for data entry or printing and scanning which frees up time for other tasks, e.g. more time for dialogue in the consultation (i.e. 'better' consultations through improved use of consultation time and prioritisation of GPs' time) However, for some interviewees, time and efficiency aspects have worked as a barrier because of lack of time to change routines and experiences with the eMDI as being too time-consuming when filled in during the consultation |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed view |

| Lafata et al. 2016 [57] | USA |

To evaluate the association of exam room use of EMRs, HRA tools, and self-generated written patient reminder lists with patient–physician communication, recommended preventive health service delivery, and visit length |

Condition of focus: Generic Setting: Primary care Tool: range of tools, including EMR tools, risk assessment tools and written patient lists - Embedded/linked with EMR: Range - Interruptive alert: Range - User-driven: Range - Risk score: n/a |

Quantitative: observational |

1. Visit length (face-to-face interaction time in minutes between patients and physicians); 2. Patient engagement communication behaviour; 3. Physician–patient-centred communication behaviour; and 4. Physician delivery of evidence-based preventive health services |

On average, physicians spent almost 27 min with the patient (SD = 10 min) Mean visit length was longer for patients who used a self-generated written reminder list compared to patients who did not use such a list (30.0 vs. 26.5 min). Visit length was also significantly longer when the EMR was accessed in the exam room compared to those visits in which the EMR was not accessed in the exam room (27.7 vs. 23.9 min) Visits that included exam room–based use of the EMR lasted, on average, just over 3 min more than visits in which the EMR was not accessed in the exam room The use of a HRA instrument was not associated with increased visit length, but was not associated with decreased length either |

Objective measure of time of whole consultations Impact on time: neither increase nor decrease |

| Litvin et al. 2012 [58] | USA |

To describe use of the CDS, as well as facilitators and barriers to its adoption, during the first year of the 15-month intervention |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: Primary care practices Tool: CDS for antibiotic prescribing for Acute Respiratory Infections - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Physician - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative analysis of EMR data + qualitative interviews and observations |

Using EMR data, CDS use was calculated at the practice level as the number of encounters at which an ARI diagnosis (or multiple diagnoses) using the CDS was made divided by the number of all encounters at which an ARI diagnosis was made, regardless of CDS use Qualitative data were recorded during practice site visits using a structured site visit field note Group interviews with staff elicited facilitators and barriers of CDS adoption |

Organisational factors: - Barrier: 'use of CDS alters workflow' - Facilitator: perception that CDS speeds up the visit and shortens documentation time. Others felt that the CDS did not affect the length of the visit. None reported that the CDS slowed the visit |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed view |

| Lugtenberg et al. 2015 [59] | Netherlands | To investigate the exposure to and experiences with the CDS quality improvement intervention, to gain insight into the factors contributing to the intervention’s impact |

Condition of focus: Generic Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for range of activities, including patient data registration, prescribing and management - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative analysis of usage data + survey + qualitative interviews |

Quantitative: - NHGDoc data to measure exposure to the intervention in both study groups - Survey data on exposure to and experiences with the CDS intervention Qualitative: range of barriers that GPs and PNs perceive in using NHGDoc or similar CDS in practice |

Survey: - Limited time available during and after consultation (60% of GPs and 16% of PNs) - Too much additional work required during and after consultation (60% of GPs, 27% of PNs) |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: Lack of time |

| Lugtenberg et al. 2015 [59–61] | Netherlands |

To identify perceived barriers to using large-scale implemented CDS, covering multiple disease areas in primary care |

Condition of focus: Range Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for range of conditions, including CVD, asthma/COPD, diabetes, thyroid disorders, viral hepatitis, AF, subfertility, gastro protection and chronic renal failure - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Qualitative focus groups | Value of CDS in a primary care setting, CDS in an ideal world, experiences with using CDS with the example of NHGDoc, perceived advantages and disadvantages, and barriers to using them in practice |

The system’s responsiveness was a problem, with the loading of alerts taking too long Many physicians mentioned that using CDS has a negative effect on patient communication during consultation and is considered a barrier to their use Discrepancy between a patient’s reason for visiting and the alert content was a reason not to use it Limited time during consultations made it difficult to use the CDS, as well as the additional work it requires |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: slow software, workload already heavy |

| Pannebakker et al. 2019 [62] | England |

To understand GP and patient perspectives on the implementation and usefulness of the eCDS |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: General Practice Tool: - Type: CDS for melanoma - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Qualitative interviews | GP and patient perspectives | Some reflected on how using CDS did not intrude in a consultation, and that it could help with saving time during or after a consultation |

Perception Impact on time: Decrease Driving perception: efficiency, reduced time needed for data entry |

| Peiris et al. 2009 [63] | Australia | To develop a valid CDS tool that assists Australian GPs in global CVD risk management, and to preliminarily evaluate its acceptability to GPs as a point-of-care resource for both general and underserved populations |

Condition of focus: Cardiovascular disease Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for CVD risk management - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Mixed: quantitative survey + qualitative interviews |

Survey: GP attitudes about the tool and management provided Interviews: general attitudes about the tool and its impact on the consultation; a review of specific tool outputs; recommendations for future tool development |

Challenges: - Time pressures introduced by incorporating CVD risk management into routine care - Extra work seen in cases where the GP didn't expect CVD risk to be high, but these instances were few - Future automation of the tool (e.g. pre-population with data) seen as important Recommendations - ‘Too wordy' to read whilst with patient. For a consultation, 'you've got 15 min at most' |

Perception Impact on time: Neither increase nor decrease Driving perception: work was increased only where risk was unexpectedly high, but this was not often |

| Rieckert et al. 2018 [64] | Germany |

To examine how GPs experienced the PRIMA-eDS tool, how GPs adopted the recommendations provided by the CMR, and explore GPs’ ideas on future implementation |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS to prevent inappropriate medication in older populations - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Qualitative interviews |

1. Polypharmacy in everyday practice 2. Using the eCRF 3. General overview of the comprehensive medication review 4. Output of the CMR and how GPs responded to the recommendations 5. Implementation of the tool into daily practice routine |

Entering patient data into the eCRF was time-consuming. After a period of familiarisation utilisation became easier and faster ‘For the first one I took 45 min I think and in the end it took me ten minutes’. (GP 14) Retrieving additional information provided by the tool was perceived as being too time-consuming |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed views |

| Rickert et al. 2019 [65] | Germany |

To examine how GPs experienced the PRIMA-eDS tool, how GPs adopted the recommendations provided by the CMR, and explore GPs’ ideas on future implementation |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS to prevent inappropriate medication in older populations - Embedded/linked with EMR: No - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Quantitative survey | Use of and attitudes toward the CMR, its recommendations, and future use |

Prerequisites for the future use of the PRIMA-eDS tool: Technical limitations were rated by 93% of GPs as important for future use of PRIMA-eDS, data security by 86%, and time requirement by 85% DISCUSSION: Previous research has shown that physicians ignored alerts when this was not the reason for the patients’ visit, as often there was not enough time to deal with both |

Perception Impact on time: Unclear |

| Robertson et al. 2011 [66] | Australia | To determine GPs’ access to and use of electronic information sources and CDS for prescribing |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for prescribing - Embedded/linked with EMR: - Interruptive alert: - User-driven: GP - Risk score: No |

Qualitative interviews |

Electronic resources/CDS: - advantages and disadvantages of electronic over paper-based resources, - valued features of electronic decision support systems, - features of alerts and reminders (content, presentation and perceived usefulness), - support and training needs |

GPs mentioned the pressures of a 10- to 15-min consultation, that their information needs were immediate at the point of care. GPs wanted relevant information presented concisely, easily searchable, integrated in the workflow and embedded in clinical software (the need to logon or go outside the main programme was seen as a burden and time waster) |

Perception Impact on time: Unclear |

| Sperl-Hillen et al. 2018 [67] | USA |

To evaluate whether the CDS intervention can improve 10-year CVD risk trajectory in patients in primary care setting |

Condition of focus: Cardiovascular disease Setting: Primary Care Tool: assessment of CV risk - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Quantitative: analysis of EMR + survey |

Primary: CV risk values and clinical impact of the CDS system Secondary: Pre- and post (18 m) survey of Primary Care physicians: - Confidence and preparedness to address CV risk with patients - Satisfaction and perceptions with the CDS |

PCPs reported that the CDS helped them to initiate discussions about CV risk (94%), improved CV risk factor control (98%), saved time when talking about CV risk with patients (93%), enabled efficient elicitation of patient treatment preferences (90%), supported shared decision making (95%), and influenced treatment recommendations (89%) |

Perception Impact on time: Decrease Driving perception: saved time in conversations with patients |

| Sperl-Hillen et al. 2019 [68, 69] | USA | To evaluate improvements to clinical outcomes, impact on clinic workflow, use of CDS and satisfaction among clinicians |

Condition of focus: Chronic disease Setting: Primary Care clinics Tool: CDS for chronic disease management & preventive care - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: - User-driven: GP - Risk score: |

Quantitative: analysis of EMR, CDS useage data, survey of clinicians |

Clinical outcomes Impact on clinic workflow CDS use rates Clinician satisfaction |

93 percent reported it saved time when talking to patients about CV risk factor control |

Perception Impact on time: Decrease Driving perception: saved time in conversations with patients |

| Sukums et al. 2015 [70, 71] | Sub-Saharan Africa | To describe health workers’ acceptance and use of the eCDS for maternal care in rural primary health care (PHC) facilities of Ghana and Tanzania and to identify factors affecting successful adoption of such a system |

Condition of focus: Antenatal and intrapartum care Setting: Primary Health Care clinics Tool: - Type: CDS for antenatal and intrapartum care - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative survey + interviews |

Perceived challenges affecting the eCDS use through a mid-term- and post- survey at 10 months (midterm) and 18 months (final) after implementation Interviews with the care providers were conducted to explore their views and experiences with the eCDS |

Perceived increase in workload due to the eCDS use reported About one third of providers indicated a lack of time to use the eCDS Reasons given for these challenges: inadequate computer skills, inadequate staffing during busy periods Perceived workload also increased due to simultaneous manual and electronic documentation, which some providers felt to disrupt their work |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: stand-alone data entry, workload already heavy |

| Trafton et al. 2010 [72, 73] | USA | To evaluate the usability of ATHENA-OT, and to identify key needs of clinicians for both integrating the CDSS into their workflow and for opioid prescribing in general |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: Primary Care Tool: CDS for use of opioid therapy for chronic, non-cancer pain - Embedded/linked with EMR: - Interruptive alert: - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative and qualitative observations, survey, interviews and usage data |

Usability of ATHENA-OT Key needs of clinicians |

Qualitative: Many competing time constraints limit use of a CDS for OT. While the CDS streamlines and facilitates practices recommended in the CPG, they still require time to complete Quantitative survey: ATHENA-OT system was rated lowest on expectations that it would save time in visits Provider Shadowing: Clinic visits varied from 13 to 59 min and averaged 31 min. 10/35 visits involved the ATHENA-OT. In these 10 visits, the time ATHENA-OT was used ranged from 3 s to 10 min Clinicians appeared to have reasonable time to use the system. This contradicts clinicians’ self-reported lack of time during visits, reflecting either non-representativeness of the visits observed, or exaggeration of time constraints by clinicians |

Perception and objective measure of time showed conflict Impact on time: mixed views |

| Trinkley et al. 2019 [74] | Canada |

To describe current clinician perceptions regarding beneficial features of CDS for chronic medications in primary care |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: Primary Care Tool: CDS for prescribing chronic medications - Embedded/linked with EMR: - Interruptive alert: - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: No |

Qualitative focus groups |

Beneficial CDS features for chronic medication management in primary care Participants' ideal CDS for chronic medications Potential unintended consequences of the CDS |

Main beneficial features of alerts: (1) non-interruptive alerts; (2) clinically relevant and customisable support; (3) summarisation of pertinent clinical information and (4) improving workflow Alerts were “one more thing to get through” and a barrier to completing tasks. Clinicians reported ‘alert fatigue’, with an overwhelming number of alerts for ‘every patient’ While not universally endorsed, some indicated they liked one alert for lung cancer screening and found it helpful, because it interrupted workflow at the right time No consensus regarding best timing of an interruptive alert. Roughly equal numbers preferred the to alert at: (1) opening of an encounter; (2) ordering or reviewing a medications; (3) entering a diagnosis or (4) at the end of the encounter |

Perception Impact on time: Unclear |

| Voruganti et al. 2015 [75] | Canada | To investigate current practices for assessing risk, awareness and use of risk assessment tools in primary care, and to assess PCPs’ perspectives regarding the usefulness, usability and feasibility of implementing computer-based health risk assessment tools into routine clinical practice |

Condition of focus: Chronic disease Setting: Primary Care Tool: risk assessment for chronic diseases - Embedded/linked with EMR: - Interruptive alert: - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: |

Qualitative focus groups | PCPs' awareness of risk assessment tools, and views on their usefulness, usability and feasibility of routinely using them in clinical practice |

Perceived benefits and shortcomings of tools: - beneficial for initiating discussion, engaging patients in risk discussions, and guiding decision-making by physicians and patients - concern about impact on workflow (“it might bring up a lot more other issues that they [patients] weren’t originally aware of and the discussion might actually… be less directed”) - some felt differently, that “it usually stops a lot of the meandering dialogue that you’d otherwise engage in” Expectations of an ideal risk assessment tool: - number of steps to complete a risk assessment should be minimised to a few clicks |

Perception Impact on time: Mixed view |

| Walker et al. 2017 [76, 77] | Australia |

To examine useability and acceptability of a prototype tool ‘CRISP’ (Colorectal cancer RISk Prediction tool), identify barriers and enablers to implementing CRISP in Australian general practice, and optimize the design of CRISP prior to an RCT |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: General Practice Tool: risk assessment for colorectal cancer - Embedded/linked with EMR: - Interruptive alert: - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: |

Qualitative: simulated consultations + interviews |

Acceptability, usability and implementation strategies were explored at an individual level (GP, PN and PM) and organizational level (the practice) using the four domains of NPT: - Coherence - Cognitive participation - Collective action - Reflexive monitoring |

Collective action - GPs, PNs and PMs all agreed that lack of GP consultation time would limit the use of CRISP by GPs - Consensus that nurses have the capacity, time and expertise to complete the risk assessment as part of routine preventive health consultations - Opinions about who would take responsibility for the final decision about screening advice was split between GPs and PNs; many GPs feared missing a diagnosis |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: lack of time |

| Zazove et al. 2017 [78] | USA |

To develop a model electronic alert that integrates into system 1 thinking (thinking that is fast and intuitive, often occurring without much conscious thought), which family medicine clinicians would use to improve identification of individuals at risk for HL |

Condition of focus: Hearing loss Setting: Family Medicine clinic Tool: risk assessment for hearing loss - Embedded/linked with EMR: - Interruptive alert: - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: |

Mixed: cognitive task analysis interviews |

How often various issues were identified, the root causes of use and non-use of the electronic alert, sample quotes highlighting major issues, and any potential solutions mentioned |

Time pressure with electronic prompts: - Clinicians felt visits were already overloaded, limiting their ability to handle additional alerts. Addressing all recommendations for complex patients requires more than the typical 15-min office visit - Alerts intrude on the doctor-patient relationship, since they rarely address the primary reason for the visit, and the added workload contributes to clinician stress due to falling further behind in the schedule Hearing loss is not easily addressable: - the “time pressure” was due to clinicians being uncomfortable and having to take time to think about how to address HL (ie, being forced into slow and effortful system 2 thinking), which they did not have to do with other conditions |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: workload already heavy |

| Murdoch et al. 2015 [79, 80] | UK | To use conversation analysis to assess the interactional workability of using CDS for telephone triage |

Condition of focus: Same-day appointment requests (range of conditions) Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS to guide nurse-led telephone triage - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No, guides triage call - User-driven: Nurse - Risk score: No |

Qualitative: conversation analysis |

1. Structuring of patient's problem 2. making sense of/managing pt's symptoms in the CDS 3. where pts' experience misaligned with CDS requirements 4. nurse accountability within CDS 5.Consequences of not using CDS on Qs and answers |

Use of CDS impacted call 'trajectory' and caused disruptions 'interactional workability' of using the CDS for telephone triage Eg. Operational problems such as mistyping a symptom or condition led to a 'prolonged pause' while nurse attempted to correct/search around for another term and explain the delay to the patient |

Objective measure of time of whole consultations but timings data not reported Impact on time: unclear |

| Jetelina et al. 2018 [81] | USA |

Proof of concept study: before and after implementation of e-tool |

Condition of focus: Behavioural Health Setting: Primary care clinics Tool: suite of e-tools for Behavioural Health Clinicians - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: No |

Mixed: quantitative surveys + qualitative interviews and observations |

Clinical outcomes and patient experience Acceptability of the e-tools Factors influencing implementation |

Acceptability: - Tool was acceptable and easy to use - Tool added 1 to 2 min to the initial visit but time during follow-up visits by automatically populating the history of the presenting illness and patient instructions at subsequent visits |

Perception Impact on time: Decrease Driving perception: efficiency, reduced time needed for data entry |

| McGinn et al. 2013 [82] | USA | To examine the effect of the tools on diagnostic and treatment patterns and to assess adoption of the tool for each condition |

Condition of focus: Upper Respiratory Tract Infections Setting: Primary care clinics Tool: CDS with clinical prediction rules for 2 URTIs - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: Yes |

Quantitative: analysis of EMR and usage data |

Usage data: number of visits involving: - tool being opened once triggered - calculator being completed - viewing of recommendations and - following of recommendations |

Time not measured or commented on Regarding diagnostic/treatment/management patterns, no significant differences between arms in proportions of visits resulting in patient returning to ED/Outpatient clinic for follow-up High adoption rates reported |

Objective workload measure of follow-up visits Impact on workload: neither increase nor decrease |

| Litvin et al. 2016 [83] | USA | To assess impact on CKD clinical quality measures and facilitators/barriers to use of tools |

Condition of focus: Chronic Kidney Disease Setting: Primary care clinics Tools: CDS tools for CKD, including risk assessment - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: Yes |

Mixed: quantitative analysis of EMR data + qualitative observations and interviews |

Quantitative: CKD clinical quality measures at baseline & 2 years Qualitative: Barriers/facilitators to using tools |

Barriers included mention by some staff that CDS tools required 'extra clicks' and additional steps outside of existing workflow |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: workflow disruption |

| Linder et al. 2009 [84] | USA | To assess effect of CDS on antibiotic prescribing rates for ARI visits |

Condition of focus: Acute Respiratory Infections Setting: Primary care clinics Tool: CDS for ARIs to help reduce inappropriate prescribing - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Clinician - Risk score: Yes |

Quantitative: analysis of EMR data |

Primary: Rate of antibiotic prescribing for ARI visits Secondary: 30-day re-visit rates attributable to ARIs |

Recorded duration of Smart Form use (assume mean) 8.1 m, sd 5.8 m. However, whole visit length not captured/reported and not compared with Usual Care Re-visit rate attributable to ARIs 8% in intervention and 9% in control but not remarked upon in Discussion or quantified as significant or not significant Remarked in discussion that to be effective, CDS must fit as seamlessly as possible into existing workflow and allow clinicians to manage unanticipated interruptions |

Objective measure of time to use tool and revisit rates Impact on time: Unclear Revisit rates not remarked upon |

| Ranta 2013 [85] | New Zealand | To assess feasibility of introducing risk tool to help timely management of TIAs |

Condition of focus: TIA & Stroke Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for TIA & Stroke risk - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Quantitative: analysis of usage data + survey |

Usage of the tool and advice rendered/actions taken by GPs Post-pilot satisfaction of GP users |

GP survey interviews reported 'no major concerns' regarding the time required to enter data (Methods report this to be 3-5 min per TIA patient) Time not formally measured and no indication given of whether time is added to the consultation (perhaps 'acceptably') |

Perception Impact on time: Unclear |

| Price et al. 2017 [86, 87] | Canada | To examine how 40 STOPP rules could be implemented as alerts into practice and the impact on prescribing |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: Family Practices Tool: Screening tool of older people's prescriptions (STOPP) - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Physicians - Risk score: No |

RCT with mixed methods: quantitative analysis of EMR data + interviews |

Quantitative: change in rate of potentially inappropriate prescriptions (PIPs) between arms Qualitative: views on barriers and facilitators of implementation |

Qualitative interviews - 'workflow' cited as a barrier to implementation, along with 'location' of alert on-screen - Workflow not expressed in terms of time (increase or decrease) or sequence of activity and not quantified or measured as time |

Perception Impact on time: Unclear |

| Wan et al. 2010 [88] | Australia | To explore GPs and patients' views of implementing CVAR assessment, including issues regarding identifying patients at risk and the timing and context for assessment |

Condition of focus: Cardiovascular disease Setting: General Practice Tool: Range of electronic and paper-based tools for cardiovascular absolute risk assessment - Embedded/linked with EMR: Unclear - Interruptive alert: Unclear - User-driven: Unclear - Risk score: Yes |

Qualitative interviews | Views of barriers and facilitators of implementing CVAR assessment | No specific e-tool examined and time not mentioned, but a general comment in Discussion that GP workload pressure is an important barrier to increasing preventive activity in general |

GP workload pressure Impact on time/workload: no conclusion |

| Hor et al. 2010 [89] | Ireland | To assess prevalence and use of EMR and any form of CDS for prescribing and to explore perceived benefits of future introduction of CDS-eP, barriers to implementation and presumptive responses to prescribing alerts |

Condition of focus: Prescribing Setting: General Practice Tool: Hypothetical CDS for e-prescribing - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Unclear - Risk score: No |

Quantitative: survey + free text |

Prevalence and use of EMR and any form of CDS for prescribing GPs' perceived benefits of future introduction of CDS-eP, barriers to implementation and presumptive responses to prescribing alerts |

Time not measured but mentioned in GPs' general comments: hypersensitive interruptive alerts whilst prescribing and causing a delay to prescribing by e.g. 20 s would be frustrating |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: workload already heavy |

| Troeung et al. 2016 [90] | Australia | To develop and evaluate performance of the e-screening tool against practice EMR data |

Condition of focus: Familial hypercholesterolaemia Setting: General Practice Tool: screening tool to identify patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: No - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Quantitative: analysis of EMR and tool data | Performance of the e-screening tool | Time reported (10 min) to run the e-screening search, not consultation length |

Objective measure of time to use tool Impact on time: Unclear |

| Jimbo et al. 2013 [91] | USA | To identify PCPs' perceived barriers and facilitators to implementation |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: General Practice Tool: CDS for patients regarding their colorectal cancer screening preferences, linked to computerised reminder alerts for clinicians - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: Patient - Risk score: No |

Qualitative focus groups | Barriers and facilitators to implementation |

Clinicians (majority) identified principal barriers to patients' access to colorectal cancer screening and patients' concerns regarding costs, but also time constraints during visits to discuss the screening options (e.g. could mean a 5–10 min conversation)—the web-based tool completed by patients prior to their visit could potentially save time at the visit Some concerns over how clinician reminder alerts would fit into the usual visit workflow, but not expanded upon |

Perception Impact on time: mixed view |

| Akanuwe et al. 2020 [92] | UK | To explore the views of service users and primary care practitioners on how best to communicate cancer risk information when using QCancer, a cancer risk assessment tool, with symptomatic individuals in primary care consultations to enable them be involved in decisions on referral and cancer investigations |

Condition of focus: Cancer Setting: General Practice Tool: Qcancer risk assessment tool - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Qualitative interviews and focus groups |

Personalising risk information Informing and involving patients Being open and honest Providing time for listening, explaining and reassuring in the context of a professional approach |

‘Talking about risk is quite difficult’ - GP may be reluctant to inform the patient about cancer risk when they themselves were uncertain about the risk calculated or how to communicate this Patients: - GPs should take time to talk to patients to gain their confidence and show they care: 'You wouldn't want to feel that you've been rushed’ - ‘GPs would need more time to use the tools in consultations' GPs: GPs expressed the need to provide more time to provide explanations to patients |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: time needed to use the tools, convey information and show caring |

| Bangash et al. 2020 [93] | USA | To develop a CDS tool for Familial Hypercholesterolemia based on physician feedback from qualitative interviews, usability testing and an implementation survey |

Condition of focus: Familial Hypercholesterolemia Setting: Primary Care Tool: CDS for FH - Embedded/linked with EMR: Yes - Interruptive alert: Yes - User-driven: GP - Risk score: Yes |

Mixed: Qualitative interviews, usability testing + survey |

The most common barrier is the increasing cognitive burden on providers due to EMR complexity and limited time during clinical encounters Most physicians are receptive towards CDS. The only survey item where the majority of the physicians gave either a neutral response or disagreed was regarding the CDS tool ‘not’ increasing time spent with a patient This response reiterated the need for CDS to be designed to increase e ciency and not add to provider burden |

Perception Impact on time: Increase Driving perception: workflow disruption, limited time during consultations |

|

| Bradley et al. 2021 [94] | UK | To synthesise qualitative data of GPs’ attitudes to and experience with a range of CDs to gain better understanding of the factors shaping their implementation and use |