Abstract

Heat-labile enterotoxin from enterotoxinogenic Escherichia coli is not only an important cause of diarrhea in humans and domestic animals but also possesses potent immunomodulatory properties. Recently, the nontoxic, receptor-binding B subunit of heat-labile enterotoxin (EtxB) was found to induce the selective death of CD8+ T cells, suggesting that EtxB may trigger activation of proapoptotic signaling pathways. Here we show that EtxB treatment of CD8+ T cells but not of CD4+ T cells triggers the specific up-regulation of the transcription factor c-myc, implicated in the control of cell proliferation, differentiation, and death. A concomitant elevation in Myc protein levels was also evident, with peak expression occurring 4 h posttreatment. Preincubation with c-myc antisense oligodeoxynucleotides demonstrated that Myc expression was necessary for EtxB-mediated apoptosis. Myc activation was also associated with an increase of IκBα turnover, suggesting that elevated Myc expression may be dependent on NF-κB. When CD8+ T cells were pretreated with inhibitors of IκBα turnover and NF-κB translocation, this resulted in a marked reduction in both EtxB-induced apoptosis and Myc expression. Further, a non-receptor-binding mutant of EtxB, EtxB(G33D), was shown to lack the capacity to activate Myc transcription. These findings provide further evidence that EtxB is a signaling molecule that triggers activation of transcription factors involved in cell survival.

Heat-labile enterotoxins (Etx) from Escherichia coli and cholera toxin from Vibrio cholerae are hexameric AB5 toxins (27) responsible for causing severe and, at times life-threatening, diarrheal disease (17). Their toxicity is attributable to the enzymatic activity of the A subunit, which catalyzes ADP ribosylation of the α subunit of the trimeric GTP-binding protein Gs and leads to activation of adenylate cyclase and a concomitant elevation in cyclic AMP levels (19). The B-subunit pentamers of these toxins, which bind to monosialoganglioside GM1 (28, 29, 41), are widely thought of as delivery vehicles required for triggering uptake and internalization of the A subunit. However, recent studies on the immunological properties of recombinant preparations of the E. coli Etx B subunit (EtxB) and cholera toxin B subunit suggest that they may activate cell signaling pathways in their own right (46), leading to potent modulatory effects on the immune system. For example, EtxB has been found to exert direct effects on leukocyte populations, leading to enhanced activation and survival of B cells (31); altered differentiation of CD4+ T cells, and preferential induction of apoptosis in CD8+ T cells (10, 33, 44, 51). GM1 binding was essential for these effects since they were not induced by a non-receptor-binding mutant of EtxB, EtxB(G33D) (32). The differential effect of EtxB on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is not caused by a difference in GM1 receptor density, since the extent of B-subunit binding is the same in both T-cell subsets. Rather, EtxB was found to cause the translocation of specific transactivating NF-κB complexes in CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells (37, 39). NF-κB is a stress-responsive transcriptional factor activated by many stimuli (25, 26). It has recently become apparent that NF-κB can activate cell death pathways (13, 26) by transcriptional activation of one of its target genes, c-myc (9, 38, 43). The c-myc oncogene has been implicated in control of cell proliferation and differentiation, as well as neoplastic transformation (9). Myc associates with the Max protein (Myc-associated factor X) and activates gene transcription by cobinding to promoter regions containing an “E-box element” (1, 3). In addition to heterodimer formation with Myc, Max also forms Max-Max homodimers and can heterodimerize with members of a network of Myc antagonist proteins (Mad family, Mxi, and Mnt), which can compete for occupation of E-box elements and lead to repression of transcription (12). As for NF-κB, Myc has been shown to participate in the regulation of apoptosis (43). Inappropriate expression of c-myc can result in programmed cell death in different cell types, including fibroblasts, hepatocytes, epithelial cells, and lymphoid cells (35, 43). Recent findings have suggested that expression of c-myc sensitizes cells to proapoptotic stimuli by inducing cytochrome c release (20) and/or activating the caspase proteolytic cascade (21, 30). Notwithstanding these observations, some studies indicate that Myc can play an antiapoptotic role (7). For example, in anti-immunoglobulin (Ig)-stimulated B cells, Myc is involved in rescuing cells from apoptosis by transcriptional activation of a variety of genes involved in the cell cycle (43, 48, 50). The apparently contrasting role of Myc indicates that the molecule possesses a dual function capable of promoting either proliferation or apoptosis (11, 15).

Here we demonstrate that increased Myc expression participates in the EtxB-mediated induction of cell death in CD8+ T cells. The implications of these findings for understanding the potent immunomodulatory properties of EtxB are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All reagents were purchased by Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.) unless otherwise stated. SN50, a cell-permeable inhibitor of NF-κB translocation, was purchased from Biomol Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, Pa.). Recombinant preparations of EtxB and EtxB(G33D) were purified from cultures of Vibrio sp. strain 60 harboring plasmid pMMB68 and pTRH64, respectively, as reported previously (32).

Mice.

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan Olac (Bicester, United Kingdom) and maintained in the departmental animal facility. Mice were 8 to 10 weeks of age at the time of the experiments.

Isolation of murine T cells.

Murine mesenteric lymph node cells were isolated as described previously (33). For the purification of specific T-cell populations, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin and 5 mM EDTA prior to addition of specific antibodies conjugated with magnetic cell-sorting colloidal superparamagnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbuch, Germany) for 35 min on ice (45). CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were negatively selected using antibodies to CD8 and CD45R(B220) or to CD4 and CD45R(B220), respectively. In experiments where CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated from the same lymph node preparation, CD4+ T cells were negatively selected, while CD8+ T cells were positively selected with anti-CD8 antibodies. No significant differences in gene activation were observed between CD8+ T cells negatively or positively selected. Labeled cell suspensions were applied to visible-spectrum selection columns (Miltenyi Biotec), and the negative fractions were eluted. All CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations were >95% pure as revealed by flow cytometry.

Lymphocyte cultures.

Purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 at a concentration between 2 × 106/ml and 5 × 106/ml in alpha-modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 4 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU of penicillin, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom). When cultures were treated with various agents the following concentrations were used unless otherwise stated: EtxB, 30 μg/ml; EtxB(G33D), 30 μg/ml; N-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK), 25 μM; SN50, 50 μg/ml; and dl-α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), 5 mM (Calbiochem, Nottingham, United Kingdom).

Multiprobe RNase protection assay.

The RNase protection assay was performed as indicated in the manual provided in the RiboQuantTM Multiprobe RNase protection assay system for the mouse Myc proto-oncogene (mMyc template array; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). Briefly, total RNA from purified CD8+ and CD4+ mesenteric T cells was prepared by LS TRI-reagent protocol and quantified both spectrometrically and electrophoretically (Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer–1% agarose gel). The Pharmingen multiprobe set contained a series of cDNA templates for Sin3, c-myc, N-myc, L-myc, B-myc, max, Mad1, mxi, Mad3, Mad4, mnt, and the housekeeping gene L32 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) to allow normalization of the samples. The multiprobe template set was transcribed as antisense RNA probes by T7 RNA polymerase in the presence of [α-32P]UTP (ICN, Irvine, Calif.). Labeled probes were hybridized overnight with 4 to 5 μg of total RNA, after which free probe and other single-stranded RNA species were digested with RNases A and T1. The remaining “RNase-protected” probes were purified and resolved by urea-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Mouse control RNA and yeast tRNA were also run. The expressed genes were detected by autoradiography, and the level of gene expression was determined using the Scion Image program (Scion Corporation, Frederick, Md.). To accurately establish the identity of each protected fragment, we have analyzed their migration distances against a plotted standard curve of the migration distance for undigested probe versus nucleotide length on a logarithmic scale.

Flow cytometry.

To quantify apoptotic CD8+ T cells after EtxB treatment, cell cycle analysis was performed. The proportion of CD8+ T cells in the apoptotic subdiploid (G0/G1) stage was determined by flow cytometry analysis of the DNA content following staining with propidium iodide as described previously (34).

AS-ODN treatments.

Myc antisense and nonsense phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides (AS-ODNs and NS-ODNs) (40) were synthesized (Sigma-Genosys, Pampisford, United Kingdom) and were added directly to the culture medium at a concentration of 10 μM for 4 h prior to EtxB treatment. Sequences used were as follows: antisense c-myc, CACGTTGAGGGGCAT; and nonsense c-myc, AGTGGCGGAGACTCT.

Western blotting.

After each treatment, purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were washed in fresh culture medium and subjected to freeze-thaw lysis with liquid nitrogen, followed by incubation in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 supplemented with 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium fluoride, and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate on ice for 30 min. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and protein concentrations were determined using a commercially available kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). Cell lysates with equivalent protein content (∼50 μg) were electrophoresed in a sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel and were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Protein content after the transfer was visualized by Ponceau staining, and intensity was calculated by using the Scion Image program, as described previously. No differences in loading have been observed in the data shown. Myc and IκBα protein levels were detected using polyclonal rabbit antibodies against Myc and IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.). Horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

RESULTS

EtxB specifically activates c-myc expression in CD8+ T cells.

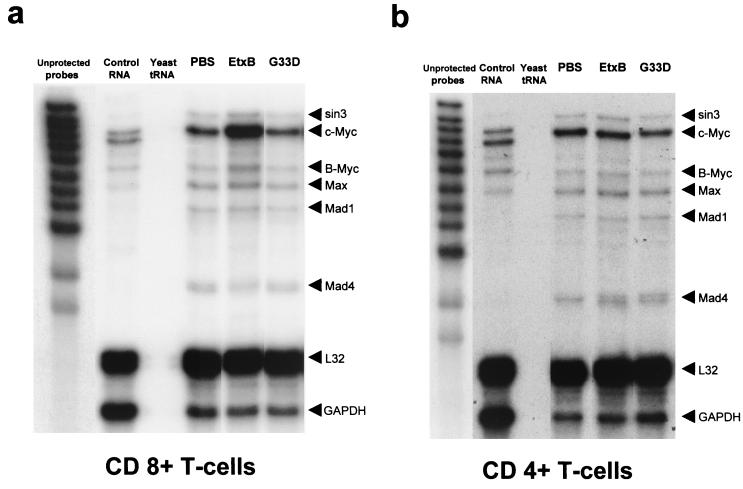

In previous studies, it has been observed that NF-κB is activated on EtxB treatment of mesenteric lymph node cultures containing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (37, 39). Since c-myc is a target gene of NF-κB transcriptional activity, we have tested if Myc family members were also affected by EtxB treatment. To assess this, we used a highly sensitive and specific mouse Myc multiprobe RNase protection assay system that allows the simultaneous detection of expression of c-myc, L-myc, B-myc, Max, Mnt, Sin3, Mxi, and Mad family members. Incubation of CD8+ T cells with EtxB induced a large (up to ca. sevenfold) increase in c-myc expression (Fig. 1a and c) with a peak activation occurring at 6 h posttreatment. Apart from a slight elevation in Sin3 and B-myc RNA expression (up to twofold), no significant transcriptional activation of Max or Mad1 was observed, while Mad4 RNA transcripts were slightly down-regulated (Fig. 1a). Protected probes for L-Myc, Mxi, Mad3, and Mnt were barely detectable in samples derived from either PBS- or EtxB-treated CD8+ cells. It is noteworthy that the elevation in c-myc mRNA levels after EtxB treatment is not counterbalanced by a corresponding transcriptional activation of genes encoding Myc antagonist proteins (i.e., the Mad family which can normally compete for occupation of E-box elements and lead to repression of c-myc transcription). In order to demonstrate that GM1 receptor binding was essential in EtxB-mediated c-myc activation, we assessed if the non-receptor-binding mutant, EtxB(G33D), elicited a similar effect. EtxB(G33D) treatment failed to activate any member of the c-myc family or c-myc antagonist genes (Fig. 1a and c).

FIG. 1.

EtxB induces c-myc gene expression in CD8+ T cells. Purified CD8+ (a) and CD4+ (b) T cells derived from mesenteric lymph nodes were incubated for 6 h in the presence of PBS, 30 μg of EtxB/ml, or 30 μg of EtxB(G33D)/ml. Total RNA was extracted and hybridized with a labeled myc multiprobe template set as described in Materials and Methods. Unprotected probes, mouse control RNA, and yeast tRNA were also run simultaneously with the samples. Identical results were obtained on three independent occasions. Quantification of c-myc gene expression in CD8+ (c) and CD4+ (d) T cells incubated for 4 and 6 h in the presence of PBS (white columns), 30 μg of EtxB/ml (black columns), and 30 μg of EtxB(G33D)/ml (grey columns) was obtained by normalizing c-myc band intensity in comparison with the GAPDH housekeeping gene. Mean values ± standard deviations of three independent experiments are shown.

The effect of EtxB treatment on c-myc expression in CD4+ T cells was also tested. In contrast to CD8+ T cells, EtxB failed to induce the expression of either c-myc or genes involved in modulation of Myc function in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1b and d). No c-myc activation in CD4+ T cells occurred up to 18 h post-EtxB treatment (data not shown).

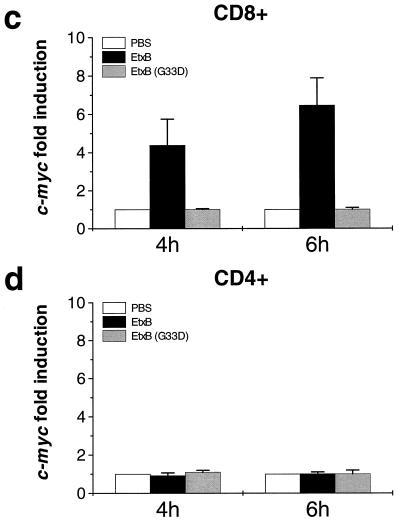

Activation of c-myc gene expression by EtxB is associated with an increase in Myc and decrease in IκBα protein levels.

When CD8+ T cells were treated with 30 μg of EtxB/ml for different time periods and Western blot analysis was performed using a polyclonal rabbit anti-Myc antiserum, a clear increase in Myc protein expression was observed 4 to 6 h post-EtxB treatment (Fig. 2a). As expected, no activation of Myc protein expression was observed in CD4+ T cells following EtxB treatment (Fig. 2a). Myc expression was associated with alterations in IκBα turnover, consistent with NF-κB activation. Polyclonal anti-IκBα antibodies were used to probe immunoblots of total cellular proteins from CD8+ T cells treated for various lengths of time with EtxB and cycloheximide, a protein synthesis inhibitor. The results shown in Fig. 2b demonstrate that EtxB treatment leads to a more rapid turnover of IκBα protein levels compared with what is seen in PBS-treated cells. A decrease of IκBα levels was observed after 2 h of EtxB/cycloheximide treatment (Fig. 2b). Moreover, to further corroborate the link between Myc and NF-κB activation, we tested the effect of SN50, a permeable peptide that specifically blocks the intracellular recognition of the nuclear localization sequence of homo- and heterodimers of NF-κB and inhibits their nuclear translocation (23). CD8+ T cells preincubated for 2 h with 50 μg of SN50/ml and for a further 6 h with EtxB showed no increase in Myc protein levels, in contrast to that observed by treating cells with EtxB alone (Fig. 2c).

FIG. 2.

EtxB induces c-myc protein overexpression and IκBα degradation in CD8+ T cells. (a) CD8+ and CD4+ mesenteric T cells were incubated for 4 and 6 h in the presence of PBS and 30 μg of EtxB/ml. −, absence of EtxB; +, presence of EtxB. The Myc level is denoted on the left in kilodaltons. (b) Total IκBα degrades faster in CD8+ T cells treated with EtxB. CD8+ T cells were incubated with cycloheximide (20 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of 30 μg of EtxB/ml, and the reaction was terminated at the time points shown. IκBα level is denoted on the left in kilodaltons. (c) SN50 blocks EtxB-induced c-myc protein expression in CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cells were preincubated for 2 h with 50 μg of SN50/ml and were then treated for a further 6 h in the presence of 30 μg of EtxB/ml. Myc and IκBα protein levels were detected by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. The Myc level is denoted on the left in kilodaltons. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments.

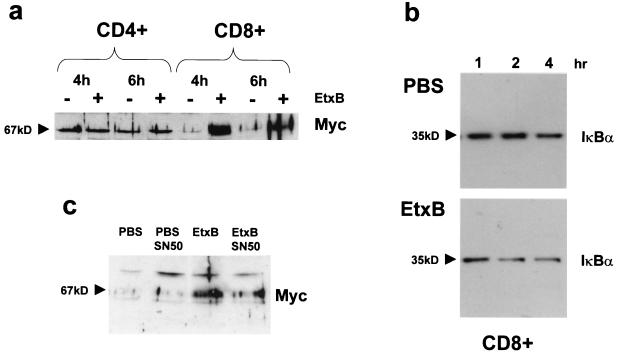

Myc AS-ODNs reduce EtxB-induced apoptosis in CD8+ T cells.

We assessed if Myc was also involved in the apoptotic process induced by EtxB in CD8+ T cells. The expression of the c-myc gene was blocked by using phosphorothioate-derivatized AS-ODNs complementary to the 5′ end of the second exon, which includes the translation start codon (16, 40). NS-ODNs with the same base composition as those of the c-myc antisense were also employed (40). Purified CD8+ T cells were preincubated for 4 h in the presence of 10 μM Myc AS-ODNs or NS-ODNs. EtxB was then added at a concentration of 30 μg/ml for a further 24 h, and cell cycle analysis was performed by flow cytometry following DNA staining with propidium iodide. As previously observed (33), EtxB treatment caused an increase in the proportion of CD8+ T cells containing subdiploid DNA below the G0/G1 peak, characteristic of cells undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 3a and b). As shown in Fig. 3c, pretreatment with Myc AS-ODNs significantly reduced the appearance of subdiploid DNA in CD8+ T cells treated with EtxB. Western blot analysis confirmed that treatment with Myc AS-ODNs reduced the level of both basal and EtxB-induced Myc protein expression (Fig. 3d).

FIG. 3.

Myc AS-ODNs reduce EtxB-induced apoptosis in CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cells were incubated with PBS (a) or EtxB (b). (c) EtxB-treated cells were also preincubated for 4 h with 10 μM Myc AS-ODNs. Cells were then stained with propidium iodide, and the proportion of CD8+ T cells in the apoptotic subdiploid (G0/G1) stage was determined by flow cytometry analysis. The percentage of total subdiploid cells is indicated on top of the respective peak. (d) CD8+ T cells were sham treated or preincubated for 4 h with 10 μM Myc AS-ODNs in the presence or absence of 30 μg of EtxB/ml, and the reaction was terminated at 6 h. Myc protein levels were detected as described in Materials and Methods and measured in kilodaltons, as marked on the left. The results shown in the figure are typical of three independent experiments.

Three experiments were carried out to determine the reduction of apoptosis by Myc AS-ODNs. CD8+ T cells were preincubated for 4 h with 10 μM Myc AS-ODNs or NS-ODNs and were then treated with 30 μg of EtxB/ml. They were then stained with propidium iodide, and the percentage of CD8+ T cells in the apoptotic subdiploid stage was determined by flow cytometry. Mean values ± standard deviations of the three experiments were as follows: cells in PBS, 26.6% ± 7.1% apoptotic cells; cells in EtxB, 44.2% ± 5.7%; cells treated with EtxB and Myc NS-ODNs, 42.6% ± 3.4%; cells treated with EtxB and Myc AS-ODNs, 28.2% ± 4.3%.

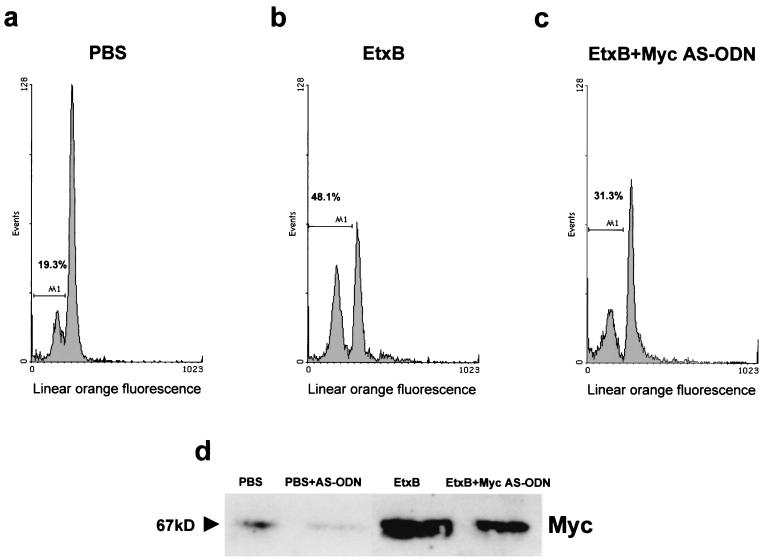

TPCK treatment reduces EtxB-induced apoptosis and Myc expression in CD8+ T cells.

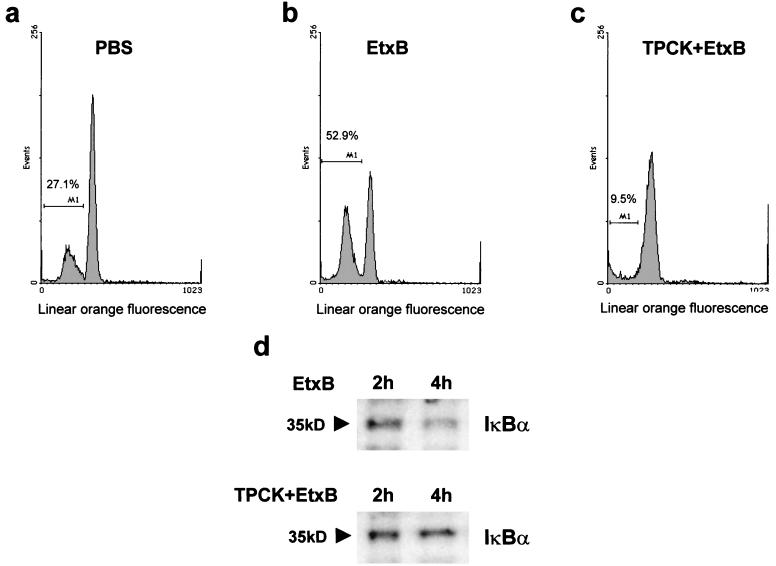

To test if the IκBα/NF-κB pathway is involved in the apoptotic process observed in CD8+ T cells and participates in activation of c-myc expression, the effect of the serine protease inhibitor TPCK, which specifically inhibits IκBα turnover (22, 49), was investigated. Purified CD8+ T cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 25 μM TPCK for 2 h and were subsequently incubated with EtxB for a further 24 h. As expected, EtxB treatment alone led to a considerable increase in the apoptotic population of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4b), while the pretreatment with TPCK, prior to the addition of EtxB, dramatically reduced induction of apoptosis (Fig. 4c). The same effect was observed by pretreating CD8+ T cells with SN50 (39). In addition, levels of IκBα were unaltered in CD8+ T cells treated with TPCK/EtxB, in comparison with the increased IκBα turnover in cells treated with EtxB alone (Fig. 4d).

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of IκBα turnover by TPCK drastically reduces EtxB-induced apoptosis in CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cells were incubated with PBS (a) or 30 μg of EtxB/ml (b). Cells were also preincubated for 2 h with 25 μM TPCK and were subsequently treated with EtxB (c) for a further 24 h. Propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry analysis were performed as for Fig. 3. (d) TPCK reduces IκBα turnover in EtxB-treated CD8+ T cells. CD8+ T cells were incubated with cycloheximide (20 μg/ml) in the presence of 30 μg of EtxB/ml alone or EtxB plus 25 μM TPCK for 2 and 4 h. IκBα protein levels were detected by Western blotting as for Fig. 2b and are denoted on the left in kilodaltons. Identical results were obtained in three independent experiments.

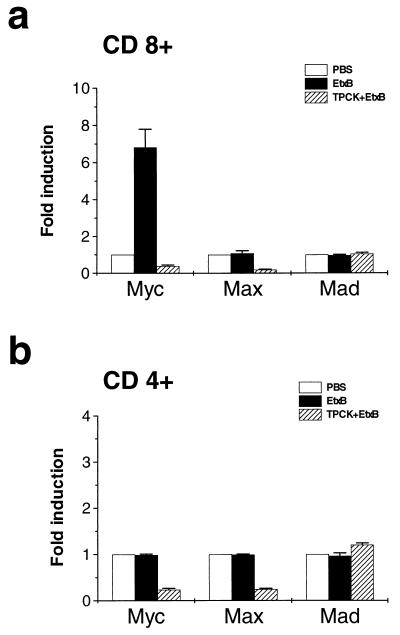

In order to verify if the antiapoptotic effect of TPCK was associated with a lack of up-regulation of Myc expression, the Myc multiprobe RNase protection assay was performed using total RNA isolated from EtxB- and TPCK/EtxB-treated CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. When normalized to that of the L32 housekeeping gene, c-myc and Max expression was reduced in TPCK/EtxB-treated CD8+ T cells, while the Mad repressor factor seemed to be unaffected (Fig. 5a). A similar trend was also observed in CD4+ T cells treated with TPCK and EtxB (Fig. 5b), indicating that in such cells Myc basal expression is likely to depend on NF-κB activation. In addition, Western blot experiments on CD8+ T cells treated with both EtxB and TPCK showed that the EtxB-induced increase in Myc protein expression was completely abolished in cells pretreated with TPCK (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

TPCK down-regulates c-myc expression in CD8+ T cells. CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were preincubated for 2 h in the presence of 25 μM TPCK and were then treated with 30 μg of EtxB/ml for a further 6 h. Total RNA was extracted and hybridized with a labeled myc multiprobe template set. Quantification of c-myc, Max, and Mad1 gene expression in CD8+ (a) and CD4+ (b) T cells treated with PBS (white columns), EtxB (black columns), or a combination of TPCK and EtxB (striped columns) was obtained by normalizing c-myc, Max, and Mad1 expression to L32 housekeeping gene expression. The results are mean values ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In order to elucidate the molecular mechanisms responsible for the potent immunomodulatory properties of EtxB (46), we have investigated the signaling events triggered following binding of EtxB to its receptors on T cells. It has been previously shown (32, 33) that EtxB treatment exerts a differential effect on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, leading to the selective depletion of the CD8+ T-cell subset. In this study, we present evidence for the involvement of c-myc in EtxB-induced apoptosis of CD8+ T cells. Up-regulated expression of c-myc mRNA and protein occurred approximately 2 to 4 h after addition of EtxB (Fig. 1 and 2). In contrast, EtxB failed to induce activation of Myc in CD4+ T cells, which are refractory to EtxB-triggered apoptosis (33). Moreover, partial blocking of Myc protein translation by the use of AS-ODNs resulted in a significant inhibition of EtxB-induced apoptosis in CD8+ T cells. When the non-receptor-binding mutant EtxB(G33D), which fails to trigger CD8+ T-cell depletion (33), was used, Myc activation did not occur (Fig. 1a and c). We therefore propose that GM1 binding by EtxB triggers an elevation in Myc expression in CD8+ T cells and that this in turn contributes to EtxB-mediated apoptosis.

Myc functions as a transcriptional regulator as a part of a network of interacting factors (6). Transcription activation is mediated exclusively by Myc:Max complexes, whereas Max:Max, Max:Mad, and Max:Mxi complexes act as competitors of Myc:Max by binding to the same E-box elements (4, 5). Our findings that there is a specific activation of Myc (Fig. 1 and 2) but not a corresponding increase in the antagonist proteins, such as Mad1, Mxi, and Mnt (12), argue for a transcriptionally active role of Myc during EtxB-induced apoptosis. Given that the Mad1 family proteins have a short half-life and are not elevated by EtxB treatment, this would reduce their ability to repress transcription by antagonizing Myc binding to Max (2). Indeed, it has recently been shown that microinjection of plasmids encoding Mad1 protein was sufficient to rescue fibroblasts from Myc-induced apoptosis (14). Following EtxB treatment, Max expression was also not elevated, and this is in agreement with the generally held view that Max is not highly regulated and that its protein is very stable (2). Consequently, an elevation in Myc expression should alter the prevalence of transactivating Myc:Max heterodimers versus Max:Max transinhibitory homodimers. This is consistent with the fact that increased Max expression in vivo inhibits the function of c-myc in transgenic mice and reduces the rate of lymphoma onset (24).

A central question is how might an increase in transcriptionally active Myc be associated with CD8+ T-cell apoptosis? Although Myc has been postulated to function in an antiapoptotic fashion (7, 48), our findings suggest that at least in CD8+ T cells stimulated with EtxB, Myc up-regulation is associated with an increase in the proportion of cells undergoing apoptosis. This concurs with an emerging view that Myc can play a proapoptotic role in certain systems, and various models have been proposed (18). For example, it has been postulated that the proapoptotic potential of Myc could be related to both alterations in cell cycle control (9) via modulation of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) expression (8) or by induction of cytochrome c release leading to caspase activation (38). ODC is a rate-limiting enzyme of polyamine biosynthesis required for entry into the cell cycle and has been shown to be a transcriptional target of c-myc (8, 36). Using DFMO, a specific irreversible inhibitor of ODC enzymatic activity, at concentrations up to 5 mM, we have observed no effect on EtxB-induced apoptosis in a population of mesenteric CD8+ T cells (data not shown). In contrast, results from our laboratory have shown that caspase 3 is activated during EtxB-induced apoptosis in CD8+ T cells (39), supporting the possibility that a caspase-dependent apoptotic mechanism is initiated by Myc. This is in agreement with the finding that caspase 3 is proteolytically cleaved to active subunits during c-myc-induced apoptosis in Rat1A MycER cells expressing a conditionally active c-myc protein (21). Moreover, in the same study the activity of ODC was not required for the c-myc-mediated apoptosis (21).

The finding that Myc and NF-κB are specifically activated in apoptotic CD8+ T cells and that blocking of NF-κB translocation leads to Myc down-regulation and to rescue of the cells from death suggests that NF-κB participates in the apoptotic process by modulating Myc gene expression (22). In particular SN50, a permeable peptide that specifically inhibits NF-κB translocation (23), was able to block both Myc expression (Fig. 2c) and apoptosis (39) in EtxB-treated CD8+ T cells. A similar effect was also obtained by using the serine protease inhibitor TPCK (Fig. 4 and 5), which can block IκBα degradation and prevent NF-κB translocation to the nucleus. These findings lend further support to the view that the turnover of IκBα and the concomitant activation of NF-κB are responsible for triggering Myc-dependent induction of apoptosis.

How might Myc-induced apoptosis of CD8+ T cells contribute to the potent immunomodulatory properties of EtxB? CD8+ T cells represent an important source of the cytokine gamma interferon, and their temporal depletion from sites of immune induction ought to alter the microenvironment responsible for antigen-driven T-helper responses. Such a modulation of cytokine expression would bias the immune responses towards a Th2 response, characterized by high levels of serum antigen-specific IgG1, mucosal IgA, and CD4+ T cells, which secrete Th2 cytokines such as interleukin 4 (46). Further, EtxB has been successfully evaluated as a possible immunotherapeutic agent for prevention of autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and type I diabetes, which are thought to be a result of cell-mediated, inflammatory Th1 responses (42, 47). While the precise mechanisms responsible for the wide range of effects of EtxB on lymphocyte populations need to be fully explained, it is clear that the differential effects on T-cell subsets and on T-cell differentiation mediated by EtxB arise from alterations in signaling events that result in changes in cell survival and death. This study provides the first clear evidence for a role for Myc in the signaling pathways triggered by EtxB in CD8+ T cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Kenny for purifying both EtxB and EtxB(G33D) and R. Pitman and M. Jackson for helpful discussion and advice. Special thanks go to R. Salmond for kindly providing unpublished observations on the effect of SN50 on EtxB-induced apoptosis of CD8+ T cells. We also thank M. Virji for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amati B, Brooks M W, Levy N, Littlewood T D, Evan G I, Land H. Oncogenic activity of the c-Myc protein requires dimerization with Max. Cell. 1993;72:233–245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90663-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amati B, Land H. Myc-Max-Mad: a transcription factor network controlling cell cycle progression, differentiation and death. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:102–108. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amati B, Littlewood T D, Evan G I, Land H. The c-Myc protein induces cell cycle progression and apoptosis through dimerization with Max. EMBO J. 1993;12:5083–5087. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayer D E, Eisenman R N. A switch from Myc:Max to Mad:Max heterocomplexes accompanies monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2110–2119. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayer D E, Kretzner L, Eisenman R N. Mad: a heterodimeric partner for Max that antagonizes Myc transcriptional activity. Cell. 1993;72:211–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayer D E, Lawrence Q A, Eisenman R N. Mad-Max transcriptional repression is mediated by ternary complex formation with mammalian homologs of yeast repressor Sin3. Cell. 1995;80:767–776. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellas R E, Sonenshein G E. Nuclear factor kappa B cooperates with c-Myc in promoting murine hepatocyte survival in a manner independent of p53 tumor suppressor function. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10:287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bello-Fernandez C, Packham G, Cleveland J L. The ornithine decarboxylase gene is a transcriptional target of c-Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7804–7808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchard C, Staller P, Eilers M. Control of cell proliferation by Myc. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:202–206. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elson C O, Holland S P, Dertzbaugh M T, Cuff C F, Anderson A O. Morphologic and functional alterations of mucosal T cells by cholera toxin and its B subunit. J Immunol. 1995;154:1032–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evan G, Littlewood T. A matter of life and cell death. Science. 1998;281:1317–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facchini L M, Penn L Z. The molecular role of Myc in growth and transformation: recent discoveries lead to new insights. FASEB J. 1998;12:633–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foo S Y, Nolan G P. NF-kappaB to the rescue: RELs, apoptosis and cellular transformation. Trends Genet. 1999;15:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gehring S, Rottmann S, Menkel A R, Mertsching J, Krippner-Heidenreich A, Luscher B. Inhibition of proliferation and apoptosis by the transcriptional repressor Mad1. Repression of Fas-induced caspase-8 activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10413–10420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grandori C, Mac J, Siebelt F, Ayer D E, Eisenman R N. Myc-Max heterodimers activate a DEAD box gene and interact with multiple E box-related sites in vivo. EMBO J. 1996;15:4344–4357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harel-Bellan A, Ferris D K, Vinocour M, Holt J T, Farrar W L. Specific inhibition of c-myc protein biosynthesis using an antisense synthetic deoxy-oligonucleotide in human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1988;140:2431–2435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirst T R. Bacterial toxins and virulence factors in disease. In: Moss J, Iglewski B, Vaughan M, Tu A T, editors. Handbook of natural toxins. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1995. pp. 123–184. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffman B, Liebermann D A. The proto-oncogene c-myc and apoptosis. Oncogene. 1998;17:3351–3357. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hol G J W, Sixma K S, Merritt A E. Structure and function of E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin and cholera toxin B pentamer. In: Moss J, Iglewski B, Vaughan M, Tu A T, editors. Handbook of natural toxins. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1995. pp. 123–184. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juin P, Hueber A O, Littlewood T, Evan G. c-Myc-induced sensitization to apoptosis is mediated through cytochrome c release. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1367–1381. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kangas A, Nicholson D W, Hottla E. Involvement of CPP32/caspase-3 in c-Myc-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 1998;16:387–398. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirillova I, Chaisson M, Fausto N. Tumor necrosis factor induces DNA replication in hepatic cells through nuclear factor kappaB activation. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10:819–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Y Z, Yao S Y, Veach R A, Torgerson T R, Hawiger J. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-kappa B by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization sequence. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14255–14258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindeman G J, Harris A W, Bath M L, Eisenman R N, Adams J M. Overexpressed max is not oncogenic and attenuates myc-induced lymphoproliferation and lymphomagenesis in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1995;10:1013–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.May M J, Ghosh S. Signal transduction through NF-kappa B. Immunol Today. 1998;19:80–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercurio F, Manning A M. Multiple signals converging on NF-kappa B. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:226–232. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merritt E A, Hol W G J. AB(5) toxins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merritt E A, Sarfaty S, Jobling M G, Chang T, Holmes R K, Hirst T R, Hol W G J. Structural studies of receptor binding by cholera toxin mutants. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1516–1528. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merritt E A, Sarfaty S, van den Akker F, L'Hoir C, Martial J A, Hol W G J. Crystal structure of cholera toxin B-pentamer bound to receptor G(M1) pentasaccharide. Protein Sci. 1994;3:166–175. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mochizuki T, Kitanaka C, Noguchi K, Sugiyama A, Kagaya S, Chi S, Asai A, Kuchino Y. Pim-1 kinase stimulates c-Myc-mediated death signaling upstream of caspase-3 (CPP32)-like protease activation. Oncogene. 1997;15:1471–1480. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nashar T O, Hirst T R, Williams N A. Modulation of B-cell activation by the B subunit of Escherichia coli enterotoxin: receptor interaction up-regulates MHC class II, B7, CD40, CD25 and ICAM-1. Immunology. 1997;91:572–578. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00291.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nashar T O, Webb H M, Eaglestone S, Williams N A, Hirst T R. Potent immunogenicity of the B subunits of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin: receptor binding is essential and induces differential modulation of lymphocyte subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:226–230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nashar T O, Williams N A, Hirst T R. Cross-linking of cell surface ganglioside GM1 induces the selective apoptosis of mature CD8+ T lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1996;8:731–736. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Connor P M, Jackman J, Jondle D, Bhatia K, Magrath I, Kohn K W. Role of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in cell cycle arrest and radiosensitivity of Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4776–4780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Packham G, Cleveland J L. c-Myc and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1242:11–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(94)00015-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Packham G, Cleveland J L. The role of ornithine decarboxylase in c-Myc-induced apoptosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;194:283–290. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79275-5_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pitman R S, Hirst T R, Nashar T O, Williams N A. Receptor mediated apoptosis of CD8+ T cells by the B subunits of cholera-like enterotoxins. Biochem Soc Trans. 1998;26:S338. doi: 10.1042/bst026s338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prendergast G C. Mechanisms of apoptosis by c-Myc. Oncogene. 1999;18:2967–2987. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salmond, R. J., R. S. Pitman, M. Soriani, T. R. Hirst, and N. A. Williams. CD8+ T-cell apoptosis induced by Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B-subunit occurs via a novel pathway involving the NF-kB-dependent activation of caspase-8 and caspase-3. Eur. J. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Shi Y, Glynn J M, Guilbert L J, Cotter T G, Bissonnette R P, Green D R. Role for c-myc in activation-induced apoptotic cell death in T cell hybridomas. Science. 1992;257:212–214. doi: 10.1126/science.1378649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sixma T K, Pronk S E, Kalk K H, Van Zanten B A M, Berghuis A M, Hol W G J. Lactose binding to heat-labile enterotoxin revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature. 1992;355:561–564. doi: 10.1038/355561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sobel D O, Yankelevich B, Goyal D, Nelson D, Mazumder A. The B-subunit of cholera toxin induces immunoregulatory cells and prevents diabetes in the NOD mouse. Diabetes. 1998;47:186–191. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson E B. The many roles of c-Myc in apoptosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:575–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Truitt R L, Hanke C, Radke J, Mueller R, Barbieri J T. Glycosphingolipids as novel targets for T-cell suppression by the B subunit of recombinant heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1299–1308. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1299-1308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wigzell H. Specific affinity fractionation of lymphocytes using glass or plastic bead columns. Scand J Immunol. 1976;5(Suppl.):23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1976.tb03853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams N A, Hirst T R, Nashar T O. Immune modulation by the cholera-like enterotoxins: from adjuvant to therapeutic. Immunol Today. 1999;20:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams N A, Stasiuk L M, Nashar T O, Richards C M, Lang A K, Day M J, Hirst T R. Prevention of autoimmune disease due to lymphocyte modulation by the B-subunit of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5290–5295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu M, Arsura M, Bellas R E, FitzGerald M J, Lee H, Schauer S L, Sherr D H, Sonenshein G E. Inhibition of c-myc expression induces apoptosis of WEHI 231 murine B cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5015–5025. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu M, Lee H, Bellas R E, Schauer S L, Arsura M, Katz D, FitzGerald M J, Rothstein T L, Sherr D H, Sonenshein G E. Inhibition of NF-kappaB/Rel induces apoptosis of murine B cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:4682–4690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu M, Yang W, Bellas R E, Schauer S L, FitzGerald M J, Lee H, Sonenshein G E. c-myc promotes survival of WEHI 231 B lymphoma cells from apoptosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1997;224:91–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60801-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yankelevich B, Soldatenkov V A, Hodgson J, Polotsky A J, Creswell K, Mazumder A. Differential induction of programmed cell death in CD8(+) and CD4(+) T cells by the B subunit of cholera toxin. Cell Immunol. 1996;168:229–234. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]