Abstract

During entry, human papillomavirus (HPV) traffics from the cell surface to the endosome and then to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and Golgi apparatus. HPV must transit across the TGN/Golgi and exit these compartments to reach the nucleus to cause infection, although how these steps are accomplished is unclear. Combining cellular fractionation, unbiased proteomics, and gene knockdown strategies, we identified the coat protein complex I (COPI), a highly conserved protein complex that facilitates retrograde trafficking of cellular cargos, as a host factor required for HPV infection. Upon TGN/Golgi arrival, the cytoplasmic segment of HPV L2 binds directly to COPI. COPI depletion causes the accumulation of HPV in the TGN/Golgi, resembling the fate of a COPI binding–defective L2 mutant. We propose that the L2-COPI interaction drives HPV trafficking through the TGN and Golgi stacks during virus entry. This shows that an incoming virus is a cargo of the COPI complex.

HPV, a cancer-causing human pathogen, is shown to hijack the protein-sorting complex COPI during cellular entry.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) accounts for approximately 4.5% of all cancers worldwide (1). It is the primary cause of cervical cancer and accounts for a substantial fraction of other anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers (2). In addition, HPV causes a wide variety of warts, including common warts, plantar warts, and anogenital warts (3). Because of incomplete understanding of many aspects of HPV infection including entry of the virus into cells, there are no specific antiviral drugs that target HPV.

The HPV capsid, which encases the ~8-kb DNA genome, consists of 72 pentamers of the major viral capsid protein L1 and up to 72 copies of the minor capsid protein L2 (4). When fully assembled, the diameter of the capsid is approximately 55 nm (5). To cause infection, L1 binds to heparin sulfate proteoglycans at the plasma membrane of the host cell or in the extracellular matrix. This interaction imparts conformational changes to L1 that allow for cleavage of the N terminus of L2 by the extracellular protease furin (6–8). Subsequent transfer of HPV to an unknown entry receptor (8, 9) promotes virus endocytosis, enabling the viral particle to reach the endosome where the low pH induces partial capsid disassembly (10).

The partially disassembled HPV in the endosome is targeted to γ-secretase, a transmembrane protease, through the action of the p120 catenin (11). γ-Secretase then deploys an unconventional chaperone activity to promote the insertion of L2 into the endosome membrane and then into the cytoplasm (12, 13), a process driven by a C-terminal cell-penetrating peptide on L2 (14, 15). Membrane insertion allows for the bulk of L2 to protrude into the cytosol and recruit cytosolic trafficking factors, such as the retromer sorting complex that delivers the virus to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) (16–19). Several studies report L2-mediated trafficking of incoming viral components to the TGN and Golgi apparatus and possibly the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) before nuclear entry (20–22). An artificial transmembrane protein named JX4 traps incoming HPV in the TGN/Golgi compartment and inhibits infection, implying that transit through these compartments is required for infection (19).

How HPV transits the TGN and the Golgi apparatus and exits these compartments to reach the nucleus to cause infection remains unclear. Studies suggest that during transient nuclear envelope breakdown in mitosis (23, 24), transport vesicles containing HPV move from the TGN and/or Golgi apparatus to condensed chromosomes in the nucleus in an L2-dependent fashion (20, 25, 26). Throughout this transport process, the virus is thought to remain protected within a membrane-bound vesicle, with the viral DNA becoming exposed to the nucleoplasm only after mitosis is complete and the nuclear envelope reforms (27).

The retromer-L2 interaction at the endosome membrane generates vesicles that transport the incoming virus to the TGN. The subsequent transport of HPV through the TGN and Golgi stacks (a process we collectively designate here as “Golgi transit”) presumably requires other more distal-acting retrograde trafficking factors, but the identity of the host sorting machinery promoting these steps in HPV entry remains unknown. We hypothesize that successful HPV trafficking during entry requires the sequential binding of different cytosolic sorting factors to the L2 segment that protrudes into the cytoplasm. The Sapp laboratory described a mutant HPV16 L2 protein in which two highly conserved arginine residues at positions 302 and 305 (located in the cytosol when L2 protrudes into the cytoplasm) are changed to alanine (R302/5A; Fig. 1A) (28). When cells are infected with pseudovirus (PsV) containing this L2 mutant, the mutant L2 protein accumulates in the TGN along with its encapsidated DNA and thus infection is blocked (28). Follow-up studies by the Sapp laboratory suggest that the R302/5A mutant may dissociate from the TGN but fails to associate with mitotic chromatin and is subsequently reabsorbed into the TGN compartment (27). The segment of L2 that contains R302/R305 has also been identified as a nuclear retention signal and a chromatin binding domain (29, 30).

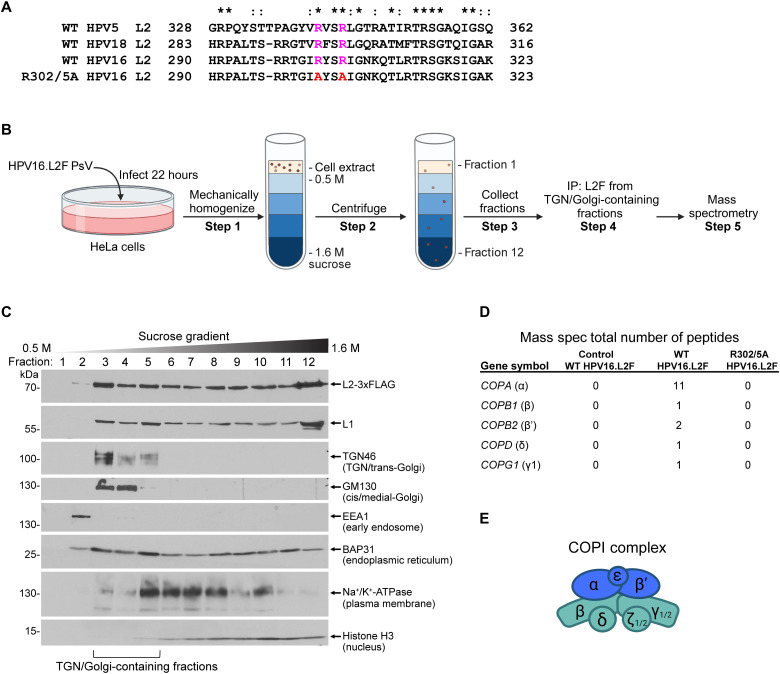

Fig. 1. Cell fractionation identifies COPI as an HPV-interacting host factor at the TGN/Golgi.

(A) Sequence alignment of the L2 protein of various HPV types. Two conserved arginine residues (magenta) are mutated to alanine (red) in R302/5A HPV16 L2. Asterisks indicate fully conserved residues. Colons indicate conservation between groups of strongly similar properties. Multiple sequence alignment of full-length L2 was performed with Clustal Omega, and the fragments containing the di-arginine motif are shown. (B) Overview of cellular fractionation to isolate material for mass spectrometry analysis. See the main text for details. Figure created with BioRender.com. (C) Representative blots from fractionated extract obtained after step 3. Extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Fractions 3 to 5 containing TGN46 and GM130 were pooled before FLAG-immunoprecipitation (step 4) and mass spectrometry (step 5). (D) Total number of peptides corresponding to subunits of the COPI complex identified by mass spectrometry (step 5). WT, material obtained from cells infected with WT HPV16.L2F PsV; R302/5A, material obtained from cells infected with R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV; control, material obtained from cells that were uninfected but mixed with WT HPV16.L2F PsV between steps 3 and 4. See table S1 for a complete list of peptides identified by mass spectrometry. (E) Simplified diagram of the COPI complex. Blue and green represent the two subcomplexes of COPI (32). Figure created with BioRender.com.

We hypothesized that L2 plays a central role in passage through the Golgi stacks separate from chromatin binding and nuclear entry and that the R302/5A mutant is defective for binding a cellular factor required for this process. Here, using a combination of a cellular fractionation method, an unbiased proteomics approach, and a gene knockdown (KD) strategy, our data reveal that the multisubunit COPI protein complex is a critical host factor during HPV infection. COPI is a major cytosolic sorting protein complex that functions to transport cellular cargos within the TGN/Golgi compartments and out of the Golgi and into the ER (31, 32). We find that upon arrival of the incoming virion to the TGN, HPV L2 directly binds to a cargo recognition subunit of COPI (33). We further show that a short peptide from L2 containing R302/R305 is sufficient to bind COPI and that COPI depletion causes the accumulation of HPV16 in the TGN/Golgi. In addition, the R302/5A L2 mutant HPV that accumulates in the TGN/Golgi is defective for COPI binding. These results indicate that the L2-COPI interaction is required for trafficking of HPV through the TGN and Golgi stacks during entry and identify an incoming virus as a cargo for this vesicle sorting complex.

RESULTS

Cell fractionation identifies COPI as an HPV-interacting host factor at the TGN/Golgi

We studied HPV entry using a well-established HPV PsV system that is composed of assembled viral capsid proteins L1 and L2, along with a reporter plasmid expressing a reporter protein such as green fluorescent proteins (GFPs) instead of the viral genome (34–36). This PsV system allows us to study wild-type (WT) HPV16 as well as L2 mutants including R302/5A. Furthermore, the PsVs contain a 3xFLAG epitope tag appended to the C terminus of L2 (called “L2F”), allowing us to use an anti-FLAG antibody to immunoprecipitate and detect the virus throughout the entry process (20). Because key intracellular trafficking steps of the HPV PsV resemble that of HPV generated by stratified keratinocyte raft cultures (37), insights from the study of HPV PsV entry continue to illuminate bona fide HPV infection events.

To elucidate the mechanism of Golgi transit, we hypothesized that during entry HPV binds to a Golgi-associated factor that sorts HPV out of the TGN or between Golgi stacks and that the R302/5A L2 mutant is unable to undergo Golgi transit because it cannot interact with this putative factor. To explore these hypotheses, we first confirmed that WT HPV16.L2F infects HeLa and HaCaT cells [via a pathway sensitive to the γ-secretase inhibitor XXI, as expected (28, 38)], but the R302/5A HPV16.L2F mutant virus is defective (fig. S1, A and B). We then used the proximity ligation assay (PLA) to assess whether R302/5A HPV16 accumulates in the TGN/Golgi [previous studies used immunofluorescence colocalization and did not examine Golgi stack markers (27, 28)]. PLA is an antibody–based assay in which a fluorescent signal is generated when two target proteins are proximal (~40 nm) to each other. If one of the proteins is a cellular organelle marker and the other is an HPV structural protein, then appearance of a fluorescent signal indicates arrival of HPV to (or near) that organelle (39). Accordingly, HeLa cells were infected with WT HPV16.L2F or R302/5A HPV16.L2F for different times, fixed, incubated with anti-L1 antibody and antibodies recognizing TGN46 and GM130 (widely used as TGN and cis-/medial-Golgi stack markers, respectively), and subjected to PLA to detect localization of HPV in the TGN or Golgi apparatus. In PLA assays, we used PsV containing a reporter plasmid expressing luciferase or red fluorescent protein instead of GFP to prevent possible interference with the green fluorescent signals generated by PLA.

In HeLa cells infected with either WT HPV16.L2F or R302/5A HPV16.L2F, similar levels of L1-TGN46 PLA signals were observed at 24 hours postinfection (hpi) (fig. S1C, top row; quantified in fig. S1D), indicating that the R302/5A virus can enter host cells and reach the TGN. In contrast, at 30 hpi, when WT virus had largely exited the TGN/Golgi compartment en route to the nucleus, we observed an approximately 4.7-fold increased L1-TGN46 PLA signal in cells infected with the mutant compared to WT (fig. S1C, bottom row; quantified in fig. S1D). However, there is not an absolute block to departure of the mutant from the TGN, because we also detected an L1-GM130 PLA signal at 24 hpi in cells infected with WT or R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV (fig. S1, E and F). At 30 hpi, the mutant PsV displayed approximately twofold accumulation in the GM130-positive compartment compared to WT PsV. As expected, only a low background level of PLA signal was detected in uninfected cells at any time point examined (fig. S1, C to F). These data confirm that the R302/5A virus accumulates in the TGN/Golgi, consistent with previous reports that showed increased colocalization of TGN46 with reporter plasmid DNA and L2 (27, 28).

To identify TGN/Golgi-associated host factors that bind to WT but not R302/5A L2 during infection, we used a cellular fractionation/proteomics approach. Cells were infected with WT HPV16.L2F or R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV. At 22 hpi (before the mutant PsV accumulates in TGN), cells were mechanically homogenized, and the resulting extract was subjected to ultracentrifugation over a discontinuous sucrose gradient (Fig. 1B, steps 1 and 2). After centrifugation, gradient fractions were collected (Fig. 1B, step 3), and a portion of each fraction was subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by immunoblotting with antibodies that mark different cellular compartments, HPV L1, or HPV L2 (FLAG). Our analysis showed that fractions 3 to 5 in infected (Fig. 1C) and uninfected (fig. S1G) cells contained the TGN and Golgi organelle markers TGN46 and GM130. In infected cells, these fractions also contained a pool of HPV16 L1 and L2. The TGN/Golgi-containing fractions of infected cells were then combined, lysed, and subjected to FLAG immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1B, step 4), which isolated similar levels of L2 from either WT or R302/5A infected cells (fig. S1H). The precipitated material was analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify potential virus-interacting host components that coprecipitated with L2F in each condition (Fig. 1B, step 5). As a control, TGN/Golgi-containing fractions derived from uninfected cells were mixed with purified WT HPV16.L2F PsV before immunoprecipitation and processed as above (“control” lane; fig. S1H). We presume that any host factors that interact with L2 under this condition are cellular components that bound to HPV after homogenization, instead of during infectious cellular entry of HPV.

As expected, the mass spectrometry results identified comparable levels of peptides corresponding to HPV L1 and L2 in samples derived from cells infected with WT HPV16.L2F, R302/5A HPV16.L2F, or from the control sample (fig. S1I). Peptides corresponding to five of the seven subunits of the COPI protein sorting complex (α, β, β′, δ, and γ; with the exception of ε and ζ) were found in the sample derived from cells infected with WT but not from the control sample with admixed PsV (Fig. 1D). The COPI peptides were not recovered from the immunoprecipitates from cells infected with R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV (the entire mass spectrometry data are available in table S1).

COPI is a multisubunit cytosolic sorting complex (Fig. 1E) that facilitates cargo trafficking within the TGN/Golgi and between the Golgi and ER [reviewed in (31–33)]. COPI is generally considered a retrograde sorting complex, but it can also sort proteins in an anterograde direction (see Discussion). This protein sorting complex displays several features consistent with being a Golgi transit factor for HPV: It associates with WT HPV localized to the TGN/Golgi during entry, it fails to associate with an L2 mutant HPV defective for Golgi transit, and it is known to display intrinsic sorting activity with cellular retrograde cargos.

The di-arginine motif in the L2 protein mediates binding between HPV16 and COPI upon TGN/Golgi arrival

To verify the mass spectrometry findings, we performed coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) and immunoblotting experiments. Extracts derived from uninfected cells or cells infected for 22 hours with WT HPV16.L2F or R302/5A HPV16.L2F were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an antibody against the β-COP subunit, and the precipitated material was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. We found that precipitation of β-COP selectively pulled down L2-3xFLAG from cells infected with WT but not the mutant PsV (Fig. 2A, top); as a negative control, an irrelevant immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody did not pull down L2-3xFLAG from the WT-infected cells because β-COP was not precipitated. Similar findings were found when antibodies recognizing β′-COP (Fig. 2B, top) or γ-COP (Fig. 2C, top) were used for immunoprecipitation. Combined with the mass spectrometry data in the preceding section, these data demonstrate that HPV engages the COPI complex in cells in a manner that requires arginine residues that are mutated in the trafficking defective R302/5A mutant.

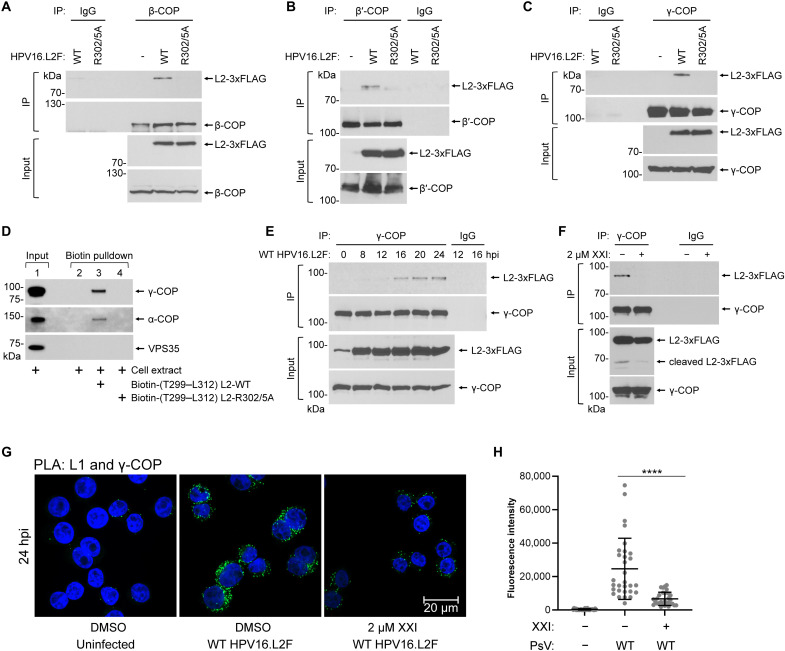

Fig. 2. The di-arginine motif in the L2 protein mediates binding between HPV16 and COPI upon TGN/Golgi arrival.

(A) Whole-cell extracts of HeLa cells uninfected or infected with WT or R302/5A HPV16.L2F for 22 hours were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti–β-COP antibody or a rabbit normal IgG as a negative control. Immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed with anti-FLAG and anti–β-COP antibodies. (B) As in (A), except an anti-β′-COP antibody was used. (C) As in (A), except an anti–γ-COP antibody was used. (D) Whole-cell extracts of uninfected HeLa cells were incubated with biotin-tagged peptides containing residues T299 to L312 of the WT HPV16 L2 (lane 3) or the corresponding R302/5A mutant (lane 4). Samples precipitated with streptavidin-beads were analyzed with antibodies recognizing α-COP, γ-COP, or retromer subunit VPS35. (E) WT HPV16.L2F–infected HeLa cells were lysed at different hpi for immunoprecipitation experiments as in (C). (F) HeLa cells were infected with WT HPV16.L2F for 20 hours in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 2 μM XXI and subjected to immunoprecipitation experiments as in (C). (G) HeLa-S3 cells were uninfected or infected with WT HPV16.L2F in the presence of DMSO or 2 μM XXI. At 24 hpi, PLA (signals shown in green) was performed with antibodies recognizing HPV16 L1 and γ-COP. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. (H) PLA fluorescence intensity per cell in multiple images as in (G) was measured, and the individual cell fluorescence intensity values, means, and SDs of 30 cells are shown. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance. ****P < 0.0001.

To assess whether a short segment of the L2 protein containing the arginine residues at positions 302 and 305 is sufficient to bind to COPI, we performed pulldown experiments with 14-residue peptides consisting of HPV16 L2 positions 299 to 312 (Fig. 1A). Peptides consisting of the WT HPV16 L2 sequence (TGIRYSRIGNKQTL) or the corresponding mutant sequence in which arginine 302 and arginine 305 are substituted with alanine (TGIAYSAIGNKQTL, with the mutated amino acids in bold) were synthesized with an N-terminal biotin tag. Peptides were incubated with extracts of uninfected HeLa cells for 2 hours. Peptides and associated proteins were then pulled down with streptavidin beads and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 2D (lanes 3 and 4), the WT but not the mutant peptide bound to α-COP and γ-COP. As expected, neither peptide bound the VPS35 subunit of retromer, which binds to a different sequence near the C terminus of L2 (18). This experiment demonstrates that a short segment derived from the middle of the L2 protein is sufficient to bind COPI and that a conserved di-arginine motif within this segment is required for the L2-COPI interaction.

To determine when the HPV-COPI interaction occurs during entry, we performed a time course experiment. Extracts derived from HeLa cells infected with WT HPV16.L2F for various times were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an antibody against γ-COP, and the precipitated material was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using a FLAG (L2) antibody. L2-3xFLAG coimmunoprecipitated with γ-COP starting at 16 hpi (Fig. 2E, top), a time point when HPV reaches the TGN (12, 17, 18, 20). Moreover, impairing HPV arrival to the TGN by inhibiting the upstream host factor γ-secretase with the chemical XXI prevented co-IP between γ-COP and HPV L2 (Fig. 2F, top); as expected, XXI blocked γ-secretase–mediated cleavage of L2 (Fig. 2F, input). Together, these biochemical data suggest that HPV interacts with COPI upon arrival in the TGN.

To assess the COPI-HPV interaction in intact cells, we performed PLA with antibodies recognizing γ-COP and HPV L1. At 24 hpi, PLA signals between γ-COP and HPV16 L1 were observed. Consistent with co-IP results, PLA signals were inhibited by treating cells with XXI, which prevents HPV trafficking to the TGN (Fig. 2G, quantified in H) (20). These imaging data suggest that transport of HPV to the TGN positions the virus proximal to the COPI complex, in agreement with our biochemical findings that HPV physically engages COPI when the virus reaches the TGN.

COPI directly binds to HPV16 L2 in vitro

To test whether HPV L2 binds directly to COPI, we incubated purified mammalian COPI complex with either purified WT HPV16.L2F PsV or the control protein enhanced GFP (EGFP)–FLAG (Fig. 3A), and the samples were subjected to FLAG immunoprecipitation. γ-COP coprecipitated with L2-3xFLAG but not EGFP-FLAG (Fig. 3B, top), suggesting that the HPV particle directly interacts with the COPI complex.

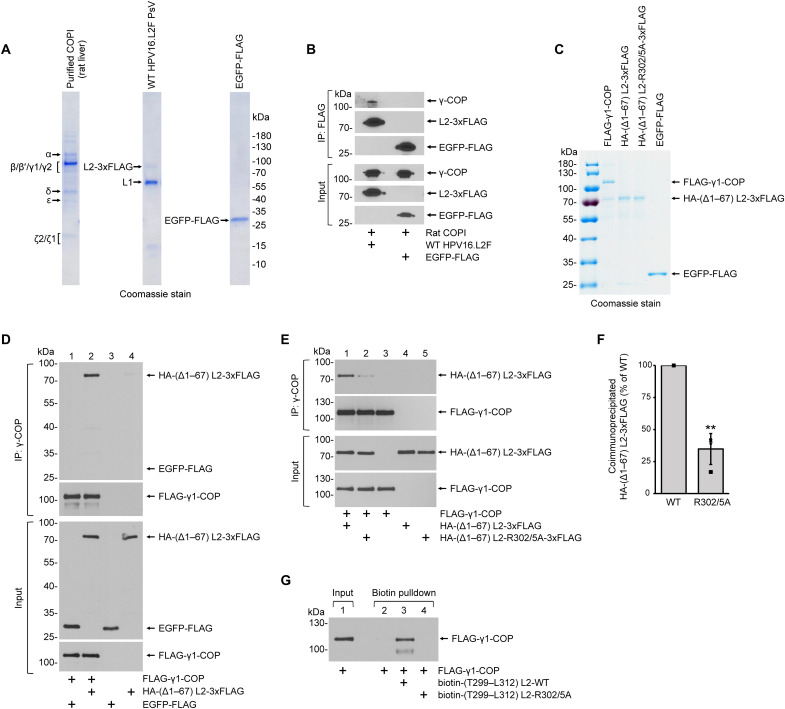

Fig. 3. COPI directly binds to HPV16 L2 in vitro.

(A) Coomassie stain (left to right): purified rat liver COPI with subunits marked left of the gel, WT HPV16.L2F PsV purified from HEK 293T cells, and purified C-terminal FLAG-tagged EGFP. (B) The rat COPI complex was incubated with WT HPV16.L2F PsV or EGFP-FLAG. Samples from immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG beads were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies recognizing FLAG or human γ-COP. (C) Coomassie stain of purified proteins. FLAG-γ1-COP, N-terminal FLAG-tagged human γ1-COP; HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG, HPV16 L2 (amino acids 1 to 67 deleted) tagged with N-terminal HA and C-terminal 3xFLAG; HA-(Δ1–67) L2-R302/5A-3xFLAG, HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG with R302/5A mutation. (D) FLAG-γ1-COP was incubated with EGFP-FLAG or HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG followed by immunoprecipitation using anti–γ-COP antibodies. Coimmunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting for HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG and EGFP-FLAG (anti-FLAG antibody) or FLAG-γ1-COP (anti–γ-COP antibody). (E) Same experiments as in (D) except that HA-(Δ1–67) L2-R302/5A-3xFLAG was analyzed for the comparison with HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG. (F) Quantification of the coimmunoprecipitated proteins shown in top of (E). The protein band intensity of HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG (WT) or HA-(Δ1–67) L2-R302/5A-3xFLAG (R302/5A) was normalized to that of FLAG-γ1-COP in the same precipitated sample. Data represents means normalized to WT and SDs (n = 4). A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance. **P < 0.01. (G) Biotin peptide pulldown as in (Fig. 2D), except biotinylated peptides were incubated with the purified FLAG-γ1-COP. Precipitated samples were immunoblotted with an antibody recognizing γ-COP.

To determine whether γ-COP, a subunit of the COPI complex that has been shown to bind cellular cargo (40, 41), binds directly to L2, we conducted in vitro binding assays with purified FLAG-γ1-COP (lacking the other COPI subunits) and a hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged HPV16 L2-3xFLAG protein lacking the N-terminal 67 amino acids [HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG] (Fig. 3C). The N terminus of L2 contains a putative transmembrane domain (amino acids 45 to 67) (42). Upon insertion, the C-terminal portion of the L2 (amino acids 68 to 473) is positioned into the cytosol where binding to COPI could take place. When purified FLAG-γ1-COP was incubated with either EGFP-FLAG or HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG and the samples subjected to immunoprecipitation using a γ-COP antibody, only HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG but not EGFP-FLAG was pulled down (Fig. 3D, top, compare lanes 2 to 1). As expected, in the absence of FLAG-γ1-COP, the γ-COP antibody did not pull down HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG (Fig. 3D, top, lane 4), indicating that the presence of γ1-COP is needed to coimmunoprecipitate L2. These findings demonstrate that γ1-COP directly interacts with the portion of L2 thought to protrude into the cytoplasm.

Because the mutant R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV did not associate with the COPI complex during viral entry in cells (Fig. 2, A to C) and because a short peptide from L2 containing the R302/5A mutation could not bind to COPI in a cellular extract (Fig. 2D), we asked whether a purified L2 protein containing the same mutation can engage γ1-COP in the in vitro system. Accordingly, we purified HA-(Δ1–67) L2-R302/5A-3xFLAG (Fig. 3C) and tested its ability to bind to purified FLAG-γ1-COP as above. Our results showed that the mutant L2 protein displayed significantly reduced efficiency in binding to γ1-COP when compared to the corresponding WT L2 protein (Fig. 3E, top, compare lanes 2 to 1; quantified in 3F). The requirement and competency of the di-arginine motif for binding to γ-COP were also evident in the peptide pulldown assay when purified FLAG-γ1-COP instead of the cell extract was used (Fig. 2D). After incubating the corresponding biotinylated peptides with the purified FLAG-γ1-COP in vitro, the L2 peptide carrying the WT di-arginine motif was sufficient to pull down FLAG-γ1-COP, whereas the peptide harboring the R302/5A mutation was defective (Fig. 3G).

Together, these findings are consistent with our biotin-L2 peptide pulldowns and co-IPs from extracts of infected cells and our mass spectrometry results, demonstrating that the di-arginine motif of L2 at positions 302 and 305 in HPV16 plays a critical role in mediating direct contact with the COPI complex.

COPI promotes HPV infection

Because we identified COPI as a direct HPV L2–binding partner during entry, we asked whether COPI is important during HPV entry. We used small interfering RNA (siRNA)–mediated KD to deplete the individual COPI subunits in HeLa cells and tested the effect on PsV infection. Isoforms of γ-COP and ζ-COP (γ1/γ2 and ζ1/ζ2) (43, 44) were also examined. The transcript levels of all the COPI subunits, with the exception of ζ1-COP, were effectively reduced by their corresponding siRNAs (fig. S2A). After KD, cells were infected with WT HPV16.L2F PsV containing the GFP reporter plasmid, and virus infection was assessed by flow cytometry to analyze GFP expression as an indication of successful delivery of the pseudoviral genome to the nucleus. WT HPV16.L2F infection was severely impaired by α-COP (COPA), β-COP (COPB1), β′-COP (COPB2), δ-COP (COPD), and γ1-COP (COPG1) KD when compared to control [scrambled (Scr) siRNA-treated] cells (Fig. 4A); a similar pattern was seen when GFP expression was analyzed by immunoblotting (fig. S2B). Notably, these required subunits are the same ones that associate with incoming WT HPV as assessed by the proteomics analysis of infected cells (Fig. 1D). The lack of phenotype in cells depleted of ε-COP may be due to its nonessential role for retrograde transport as reported in prior studies in yeast and human cells (45, 46). Of these five COPI subunits required for HPV infection, KD of α-COP and γ1-COP did not affect the level of the other subunits, while KD of β-COP, β′-COP, or δ-COP reduced the level of the others to varying extents (fig. S2C).

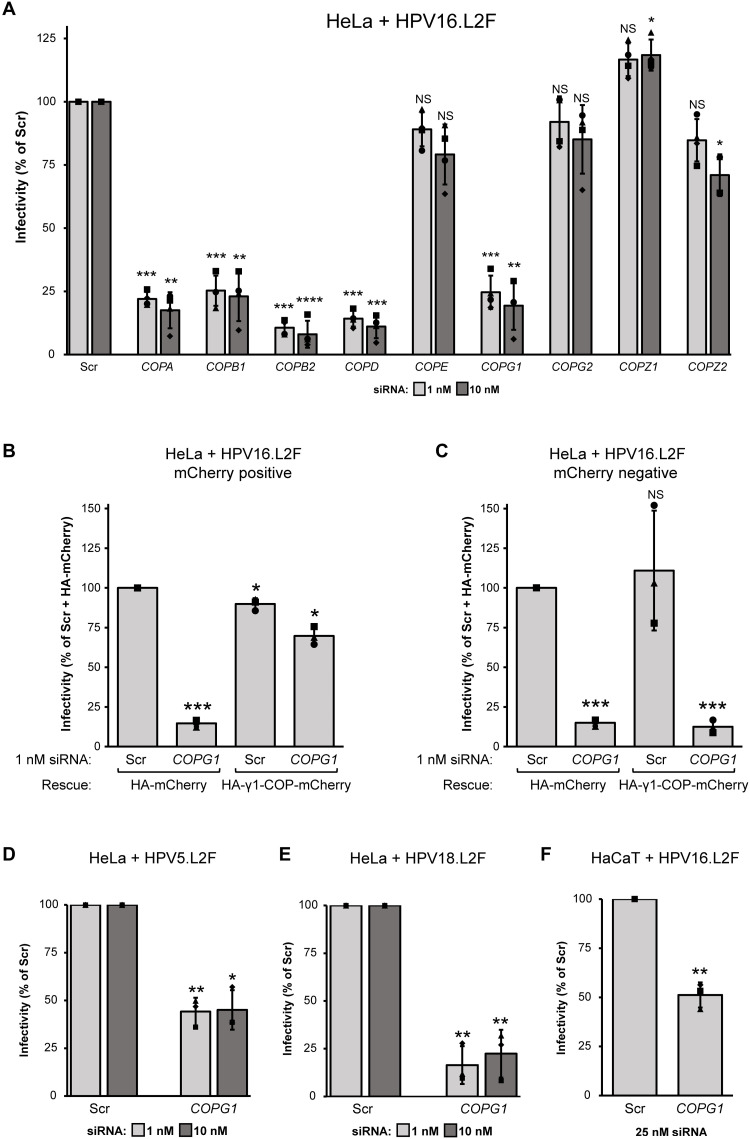

Fig. 4. COPI promotes HPV infection.

(A) HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNA for 24 hours were infected with WT HPV16.L2F PsV containing a GFP reporter plasmid. At 48 hpi, flow cytometry was used to determine the fraction of GFP-expressing cells. The results were normalized to the infected fraction of cells treated with Scr siRNA. The means and SDs are shown (n = 3). A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance compared to Scr siRNA–treated cells. NS, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with Scr or COPG1 siRNAs for 9 hours, followed by another transfection with DNA constructs for 15 hours for the expression of HA-γ1-COP-mCherry or the control HA-mCherry. The transfected cells were then infected with WT HPV16.L2F PsV containing a GFP reporter plasmid. At 48 hpi, flow cytometry was used to measure GFP and mCherry fluorescence. The fraction of cells expressing GFP in the mCherry-positive population is graphed. The results were normalized to the infected fraction of cells cotransfected with Scr siRNA and HA-mCherry–expressing plasmid. Data from three independent experiments were analyzed and presented as in (A). (C) As in (B), except the fraction of cells expressing GFP in the mCherry-negative population is graphed. (D) As in (A), except WT HPV5.L2F PsV was used. (E) As in (A), except WT HPV18.L2F PsV was used. (F) As in (A), except HaCaT cells were transfected with pooled Scr or COPG1 siRNAs for 48 hours before infection with WT HPV16.L2F PsV.

Despite blocking HPV infection (Fig. 4A), KD of γ1-COP did not affect the localization pattern of the Golgi marker GM130 (fig. S2D, first column) or β′-COP (fig. S2D, second column). In addition, γ1-COP KD did not significantly alter cell cycle progression, as measured by the percentage of cells in G1, S, or G2 + M phases compared to control cells (fig. S2, E and F). Membrane integrity and cell viability, as monitored by the ability of cells to exclude 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stain, were also largely unaffected by γ1-COP KD (fig. S2G). Moreover, γ1-COP KD cells supported infection by another nonenveloped DNA virus, SV40 (fig. S2H, left) despite robust depletion of γ1-COP protein levels (fig. S2I, left). In contrast, KD of small glutamine-rich tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein alpha (SGTA) (fig. S2H, right), a host factor important for SV40 infection (47), reduced SV40 infection as expected (fig. S2I, right). These findings demonstrate that depletion of γ1-COP did not globally disrupt cellular integrity, strongly suggesting that COPI plays a specific and critical role during HPV infection.

To establish that the COPI KD phenotype is not due to an off-target effect, we performed a KD-rescue experiment with γ1-COP fused to mCherry to allow monitoring of γ1-COP expression. Cells transfected with the Scr or COPG1 siRNA were cotransfected with the control plasmid HA-mCherry or the siRNA-resistant rescue construct HA-γ1-COP-mCherry (fig. S2J) and then infected with WT HPV16.L2F PsV. Flow cytometry analyses revealed that most cells expressed the exogenous mCherry-fusion proteins and that expression levels were similar in each condition (fig. S2K). In cells expressing HA-mCherry, KD of γ1-COP blocked infection, as expected (Fig. 4B; compare second to first bar). However, if HA-γ1-COP-mCherry is expressed in cells depleted of γ1-COP, then infection was largely restored (Fig. 4B, compare fourth to second bar), while expression of HA-γ1-COP-mCherry in cells transfected with control siRNA did not increase HPV infection (Fig. 4B, compare third to first bar). Moreover, this restoration of infection in γ1-COP KD cells was not observed in cells not expressing HA-γ1-COP-mCherry (i.e., mCherry negative) (Fig. 4C, compare fourth to second bar). These results demonstrate that the block in HPV infection from the COPG1 siRNA is due to loss of γ1-COP and not to unintended off-target effects, firmly establishing a crucial function of the COPI complex in HPV infection.

We next evaluated whether COPI is used as an entry factor by different HPV types. Depletion of γ1-COP attenuated infection by HPV5 (Fig. 4D) or HPV18 (Fig. 4E) PsVs. When different siRNAs (pooled) were used to KD γ1-COP in human HaCaT skin keratinocytes (fig. S2L), HPV16 infection was blunted as well (Fig. 4F). Thus, COPI is used by divergent HPV types to support infection in cell types relevant to HPV infection.

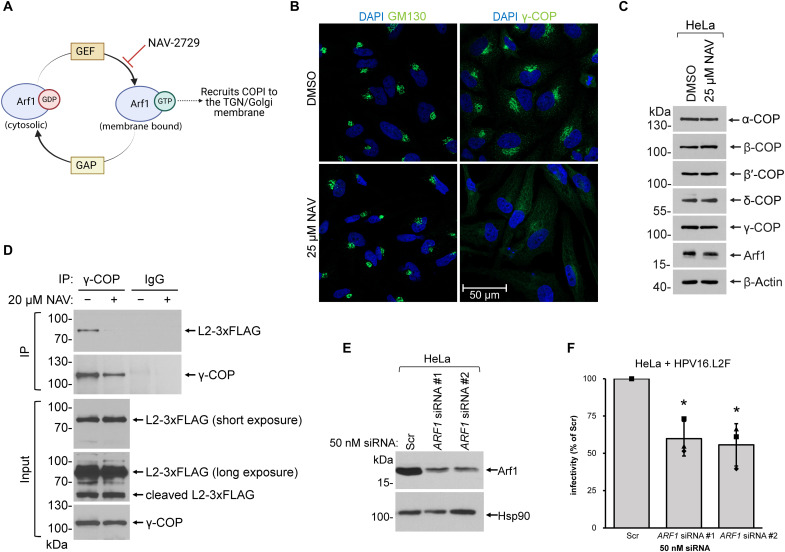

Arf1-dependent COPI recruitment to the TGN/Golgi is critical for HPV infection

Our model thus far posits that HPV, via the L2 protein protruding in the cytosol, captures COPI when the virus reaches the TGN/Golgi to promote virus infection. This model presumes that HPV L2 binds to COPI at the cytosolic surface of TGN/Golgi membranes. To test whether proper targeting of COPI to these membranes is required for HPV infection, we disrupted COPI recruitment to the TGN/Golgi membrane by inhibiting the small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) Arf1. Arf1 cycles between guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP)– and guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–bound states, a process regulated by nucleotide exchange factors and GTPase-activating proteins [guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase activating proteins] (Fig. 5A) (48). When a GEF replaces GDP with GTP on cytosolic Arf1, the resulting Arf1-GTP is directed to the TGN/Golgi membrane; this, in turn, recruits COPI to the membrane (49). The chemical inhibitor NAV-2729 (NAV) inhibits nucleotide exchange on Arf1 (50, 51), thus preventing Arf1 from binding to the TGN/Golgi membrane and subsequent recruitment of COPI.

Fig. 5. Arf1-dependent COPI recruitment to the TGN/Golgi is critical for HPV infection.

(A) Overview of COPI recruitment to the Golgi membrane by the small GTPase Arf1. The chemical inhibitor NAV disrupts Arf1 nucleotide exchange. Figure created with BioRender.com. (B) HeLa cells treated with DMSO or 25 μM of NAV for 48 hours were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with antibodies recognizing GM130 (green, first column) or γ-COP (green, second column). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Representative images of a single, medial Z plane taken by confocal microscopy are shown. (C) HeLa cells treated with DMSO or 25 μM NAV for 48 hours were lysed, and the resulting whole-cell extract was analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. β-Actin, loading control. (D) HeLa cells were infected with WT HPV16.L2F for 22 hours in the presence of DMSO or 20 μM NAV. Immunoprecipitation experiments followed by immunoblotting were carried out as in (Fig. 2C). (E) HeLa cells treated with the indicated siRNA for 72 hours were lysed, and the resulting whole-cell extract was analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies recognizing Arf1 or Hsp90 as a loading control. (F) Infectivity analysis as in (Fig. 4A) except cells were treated with Scr or ARF1 siRNA before infection (n = 3). A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance compared to Scr siRNA–treated cells. *P < 0.05.

In untreated cells, γ-COP displayed a concentrated, asymmetric perinuclear distribution that was slightly more disperse than the GM130 distribution, consistent with a TGN/Golgi localization (Fig. 5B, top row). As expected, NAV treatment resulted in a diffuse distribution of γ-COP, while leaving the Golgi structure intact as assessed by GM130 staining (Fig. 5B, bottom row). In addition, the levels of the individual COPI subunits (as well as Arf1) were unaffected by inhibitor treatment as assessed by Western blotting (Fig. 5C). These results confirm that NAV treatment prevents the localization of γ-COP to the TGN/Golgi membrane, without disrupting cellular levels of COPI or Arf1.

NAV-treatment prevented COPI (γ-COP) from binding to HPV16 L2 in infected cells as assessed by co-IP (Fig. 5D, top), suggesting that proper localization of COPI to the TGN/Golgi membrane is important for the HPV L2–COPI interaction. Notably, NAV-treatment did not block formation of the cleaved form of L2 (Fig. 5D, input, long exposure), indicating that this inhibitor did not disrupt endocytosis of HPV to the endosomes where γ-secretase typically cleaves L2. NAV treatment also blocked WT HPV16.L2F infection in a concentration-dependent manner in both HeLa and HaCaT cells, as analyzed by flow cytometry (fig. S3A) or immunoblotting for reporter gene expression (fig. S3B), but membrane integrity was not perturbed by NAV treatment (fig. S3C). Our findings are consistent with prior studies that reported chemical inhibition of Arf1-GTPase reduces HPV infection (21, 52). However, we did observe that NAV treatment affected cell cycle progression (fig. S3D), making the infection data difficult to interpret. To evaluate the role of Arf1 without disrupting mitosis, we directly depleted Arf1 itself using two different siRNAs (Fig. 5E) and found that infection was consistently reduced (Fig. 5F) while leaving membrane integrity (fig. S3E) and cell cycle progression unperturbed (fig. S3, F and G). Together, these findings indicate that COPI recruitment to the TGN/Golgi membrane, a step regulated by the Arf1-GTPase, is critical for COPI-dependent HPV infection.

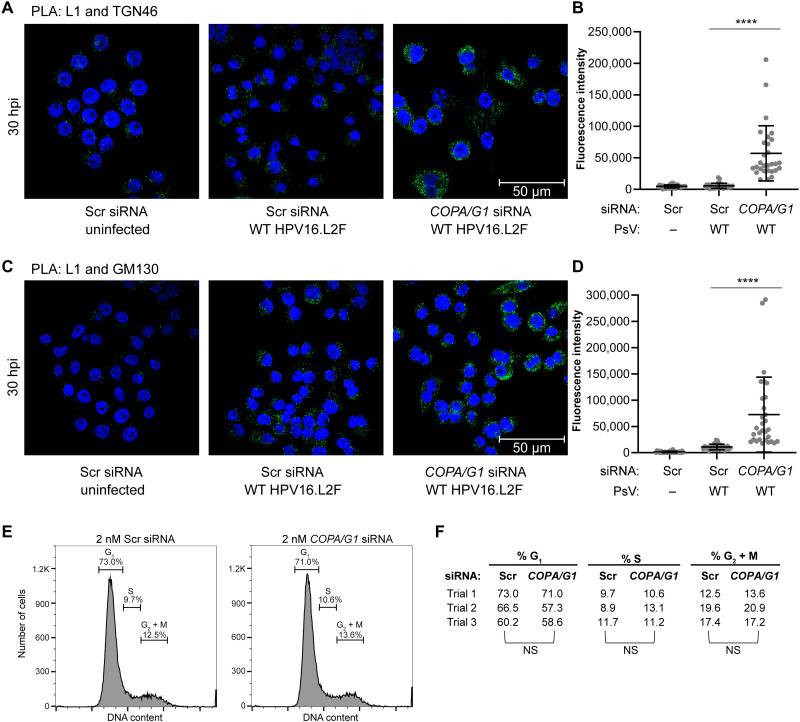

The COPI complex drives TGN/Golgi transit of HPV

What role does the HPV L2–COPI interaction play during virus entry? The COPI complex normally binds to a cellular transmembrane cargo at the TGN/Golgi, triggering a budding process that generates a COPI-coated vesicle harboring the cargo, which is then transported to the target membrane where fusion occurs (31–33). Given that COPI vesicles with a typical outer diameter of 60 to 100 nm (53, 54) are large enough to carry a partially disassembled HPV particle (diameter ≦ 55 nm), we hypothesize that the membrane-inserted L2 protein mimics a transmembrane protein, deploying its cytosolic region to bind to COPI associated with the TGN/Golgi membrane. After budding, the ensuing formation of an HPV-containing vesicle enables trafficking of incoming HPV beyond the TGN.

To test whether COPI is required for HPV trafficking, we probed the fate of HPV under COPI KD. At 30 hpi in cells infected with WT HPV16.L2F, we found that KD of α-COP and γ1-COP significantly increased the PLA signal between L1 and TGN46 compared to cells treated with Scr siRNA (Fig. 6A, quantified in B), much like the effect of the R302/5A mutation in L2. Similarly, there was a significant increase of L1-GM130 PLA signal at this time point in the KD cells (Fig. 6C, quantified in D). KD of α-COP and γ1-COP did not affect cell cycle progression (Fig. 6, E and F). These findings demonstrate that without functional COPI, HPV is impaired for passage through the TGN/Golgi compartment, indicating that COPI functions during entry to support trafficking from the TGN and within the Golgi stacks. This idea is consistent with the finding that the R302/5A mutant HPV which cannot interact with COPI also accumulates in the TGN and GM130 compartments (fig. S1, C to F). Hence, the COPI complex engages HPV L2 as a cargo, driving Golgi transit of the HPV particle to enable infection.

Fig. 6. The COPI complex drives TGN/Golgi transit of HPV.

(A) HeLa-S3 cells treated with 2 nM Scr or a mixture of 1 nM COPA and 1 nM COPG1 (COPA/G1) siRNA for 18 hours were uninfected or infected with WT HPV16.L2F PsV. At 30 hpi, PLA was performed with antibodies recognizing HPV16 L1 and TGN46 (PLA signals shown in green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Multiple images as in (A) were analyzed and presented as in (Fig. 2H). ****P < 0.0001. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (C) As in (A), except PLA was performed with antibodies recognizing HPV16 L1 and GM130. (D) As in (B), except images as in (C) were analyzed. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (E) HeLa cells transfected with the indicated siRNA for 48 hours were incubated with Hoechst 33342 and analyzed by flow cytometry to measure relative Hoechst 33342 fluorescence (DNA content). The percentage of cells in each phase is indicated. The representative histograms of three independent experiments are shown. (F) Summary of cell cycle phase distributions as in (E). Statistical significance for each phase was determined by a two-tailed, paired t test. NS, not significant (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Given the widespread distribution of HPV infection and the global burden of HPV-associated cancers (55), there is pressing need to elucidate the cellular infection mechanisms of this important human pathogen. During entry, HPV is transported from the cell surface to the TGN and Golgi apparatus on its journey to the nucleus, but it is not known how HPV transits the TGN and the Golgi stacks before nuclear entry. We show here that the COPI cellular protein sorting complex directly engages the HPV L2 capsid protein to mediate transit of HPV through the Golgi during virus entry.

Specifically, using a combination of an unbiased proteomics approach, cell-based and in vitro binding studies, along with gene silencing and chemical inhibitor experiments, we identified the COPI retrograde sorting complex as a host factor essential for HPV infection. COPI KD significantly reduced HPV infection; inhibition appears to be a specific result of impaired L2-COPI binding and not due to a global disruption of the TGN/Golgi compartment, based on Golgi marker staining, cell viability and cell cycle analysis, and on the lack of effect on SV40 infection, another nonenveloped DNA virus. We note that KD conditions for COPI and Arf1 that we used in this study are mild and do not disrupt the cell cycle but are sufficient to inhibit HPV infection, whereas harsh KD treatments such as high concentration of siRNAs or longer periods of KD of these protein sorting components are likely to be toxic and thus their effects on HPV entry would not be possible to interpret. Nevertheless, the inhibition of infectivity caused by the R302/5A mutation, which inhibits L2-COPI binding, provides additional evidence that the inhibition of infection is due to impaired L2-COPI binding but not overall cell dysfunction.

Our results support a model in which incoming HPV, via its L2 capsid protein protruding into the cytoplasm, directly binds the COPI complex upon TGN arrival to mediate subsequent trafficking steps during virus entry. γ-COP, an established cargo-binding subunit of the multisubunit COPI sorting complex (33), can interact in vitro with the segment of the L2 protein that is exposed in the cytoplasm after membrane protrusion during entry. In addition, we identified a conserved di-arginine motif located at position 302 and 305 in the cytoplasmic segment of the HPV16 L2 protein that is required for binding to COPI. Like COPI KD, a mutation in the di-arginine motif that blocks COPI binding caused HPV accumulation in the TGN and Golgi. Although the COPI complex usually binds to di-lysine K(X)KXX motifs at the C-terminal tail of cellular transmembrane cargos (56), noncanonical di-arginine motifs in some cellular cargos can also interact with COPI and mediate trafficking (57–59).

Previous studies showed that HPV is directed from the endosome to the TGN by the retromer, a cytosolic protein sorting complex that binds to L2 at the endosome membrane by 8 hours after infection (17), whereas we show here that COPI, a distinct protein sorting complex, binds L2 later (16 hpi) when the virus reaches the TGN. Both retromer and COPI normally bind to cellular transmembrane proteins. Although HPV is a nonenveloped virus and lacks classic transmembrane proteins, the virus uses a unique strategy to bind to cytoplasmic protein sorting complexes. Namely, incoming HPV inserts a segment of the L2 protein through the membranes of vesicular compartments to expose short, discrete protein binding sites in the cytoplasm, thus mimicking classic transmembrane cargos. Early during trafficking, retromer interacts with HPV L2 at a retromer binding site located near the cell-penetrating peptide at the C terminus of L2 (18). Dissociation of retromer from L2 is required for exit of HPV from the endosome and entry into the TGN (60), at which time COPI binds to L2 at a site ~150 residues N-terminal to the retromer binding site to mediate the next steps of trafficking through the TGN/Golgi. It is possible that the same L2 molecule can sequentially bind to different host cell trafficking complexes as more of the L2 protein protrudes into the cytoplasm, but because each HPV capsid can contain up to 72 copies of L2, it is also possible that different molecules of L2 within an individual viral particle may recruit the retromer or COPI at different stages of entry.

How does the L2/COPI interaction support HPV infection, and more generally, what is the role of the L2 segment encompassing the R302/R305 di-arginine motif? The segment of L2 that contains the COPI binding site (amino acid segments 188 to 332) can function as a “chromatin-binding region” (30), and mutations in this region including R302/5A abrogated the ability of an ectopically expressed L2-EGFP fusion protein to be retained in the nucleus and colocalize with mitotic chromosomes. As we show here, L2 binds directly to γ-COP, and the COPI binding defect of the of R302/5A mutant is evident in vitro with purified proteins, in peptide pulldown experiments, and in infected cells as measured by co-IP. Thus, the impaired binding of R302/5A HPV PsV to COPI is due to a direct inhibition of binding and is not an indirect effect due to impaired binding of L2 to chromatin.

It is difficult to ascribe a precise trafficking defect to the loss of the L2-COPI interaction without further experiments, but it is clear that in the absence of the interaction HPV accumulates in TGN and GM130-positive compartments and infection is inhibited. There are two broad not necessarily exclusive models that may explain this observation. In infection studies with PsV containing mutations in the central segment of L2, the viral genome and L2 accumulated in the TGN46 compartment at a time when the WT virus had exited the TGN, and microtubule-associated virus trafficking and chromosome association during the late stages of mitosis were inhibited (27, 28). These results suggest that the chromatin-binding region of L2 tethers L2 to host chromosomes during mitosis to allow L2 and the viral DNA to exit the Golgi compartment and be retained in the nucleus in association with chromosomes. In the absence of such tethering, mitotic Golgi fragments containing L2 appear to coalesce back into Golgi upon completion of mitosis, resulting in a phenotype of “Golgi retention” (27). Therefore, the phenotypes of the R302/5A mutant and COPI KD may be due to impaired chromatin association and the attendant resorption of the incoming virus into Golgi compartments and the TGN. However, this model does not readily account for our discoveries that COPI, a protein sorting complex normally active in and around the Golgi apparatus, binds directly to L2 upon TGN entry and is a required HPV entry factor, whose absence causes HPV to accumulate in the TGN/Golgi compartments.

Given our results and the known role of COPI in mediating trafficking of cellular transmembrane proteins between different subcellular compartments, we propose that COPI directly mediates trafficking of HPV-containing vesicles within the TGN/Golgi compartment via its canonical sorting activity acting on the cytoplasmic segment of L2. This interpretation is consistent with the original suggestion of Sapp and colleagues (28) that the R302/R305 segment is required “for interacting with a TGN egress factor that is required to carry the pseudogenome to a subsequent compartment.” It is also possible that the segment of L2 that contains the R302/R305 di-arginine motif plays multiple roles during viral entry. It might both bind to COPI to mediate passage through the Golgi and tether the virus to mitotic chromosomes to mediate nuclear retention. Further work is required to determine whether the coalescence of the R302/5A mutant virus back into the TGN is due to impaired COPI binding, reduced chromatin binding, or to some other effect of the mutation.

Neither COPI KD nor the R302/5A mutation blocks arrival of HPV into the GM130 compartment, implying that these manipulations cause an incomplete block to exit from the TGN. It is possible that the level of KD achieved does not cause complete functional depletion of COPI or that COPI retains low level binding to the mutant L2 protein, possibly to secondary binding sites in L2. Consistent with the latter idea, residual binding of γ-COP to mutant L2 is apparent in the in vitro binding experiments (Fig. 3, E and F), although such an interaction is too weak or transient to observe in co-IPs from cell extracts. Alternatively, there may be minor COPI-independent mechanisms that allow HPV to progress beyond the TGN but that are not sufficient to support departure of the virus from the Golgi. If defective L2-COPI interaction causes the virus to accumulate in Golgi compartments distal to the TGN by restricting passage of HPV through the Golgi or out of the Golgi, then ongoing anterograde trafficking would redistribute this virus back into the more TGN-proximal compartments. In addition, at later times, more incoming virus arrives in the TGN and Golgi without efficient means to exit. A combination of these factors may cause the observed accumulation of HPV in multiple Golgi compartments at late stages of entry.

Prior studies also found that COPI is located at ER exit sites and may play a role in anterograde cargo trafficking from the ER to the Golgi as well (61–63). We propose that COPI facilitates HPV trafficking between multiple compartments along the TGN-Golgi stack-ER axis, possibly in both a retrograde and anterograde direction. As noted above, such a broad action of COPI coupled with incomplete inhibition at any individual step would cause HPV to accumulate throughout the various compartments along this axis. Another intriguing possibility is that COPI-dependent Golgi transit of HPV might target the virus directly to the nucleus, bypassing the ER, to promote infection. There are reports of a COPI-mediated pathway linking the Golgi and nucleus (64, 65). A recent study also suggests that a RanBP10/importin/dynein-motor complex facilitates trafficking of HPV from the Golgi into the nucleus during mitosis (66). Moreover, COPI-coated vesicles are involved in Golgi-vesiculation during mitosis (67), a process that also requires active Arf1 (68). Additional experiments are needed to decipher the precise role of COPI in vesicular transport of HPV through the Golgi, the infectious route of HPV after the COPI-dependent step(s), and the mechanism of HPV nuclear entry and retention.

Although earlier studies found that brefeldin A and golgicide A, drugs that inhibit GDP-GTP exchange on Arf1 (69–72), reduced HPV infection (21, 52), a specific role for COPI during HPV entry was not examined in these studies. The findings reported here identify a role of COPI in directly engaging the incoming HPV particle, allowing trafficking through the Golgi leading to infection. Moreover, although COPI has been shown to support the life cycle of many viruses, such as vaccinia, polio, influenza, and hepatitis C viruses (73–75), the mechanism by which COPI is exploited by these viruses during infection remains unclear. By contrast, our data identify an incoming viral particle that is recognized as a direct cargo for the COPI sorting complex during virus entry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and inhibitors

Antibodies and inhibitors used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Antibodies and inhibitors.

WB, Western blot; IP, immunoprecipitation; IF, immunofluorescence; PLA, proximity ligation assay.

| Antibodies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen | Species | Catalog no./source | Application |

| FLAG | Mouse | F3165; Millipore Sigma | WB, IP |

| HPV16 L1 | Mouse | MAB885; Millipore Sigma | WB |

| α-COP | Rabbit | HPA028024; Millipore Sigma | WB |

| β-COP | Rabbit | A304-724A; Thermo Fisher Scientific | WB, IP |

| β′-COP | Rabbit | PA5-96557; Invitrogen | WB, IP, IF |

| γ-COP | Rabbit | 12393-1-AP; Proteintech | WB, IP, IF, PLA |

| δ-COP | Rabbit | 23843-1-AP; Proteintech | WB |

| Arf1 | Rabbit | 10790-1-AP; Proteintech | WB |

| TGN46 | Rabbit | ab50595; Abcam | WB, PLA |

| GM130 | Rabbit | ab52649; Abcam | WB, IF, PLA |

| EEA1 | Rabbit | C45B10; Cell Signaling | WB |

| BAP31 | Rat | MA3-002; Invitrogen | WB |

| Na+/K+-ATPase | Rabbit | ab76020; Abcam | WB |

| Histone H3 | Rabbit | 9715S; Cell Signaling | WB |

| GFP | Mouse | 632380; Takara Bio Clontech | WB |

| SGTA | Rabbit | 11019-2-AP; Proteintech | WB |

| β-Actin | Rabbit | 4967S; Cell Signaling | WB |

| Hsp90 | Mouse | sc13119; Santa Cruz Biotechnology | WB |

| HA | Rat | ROAHAHA; Roche | WB |

| HPV16 L1 | Mouse | 554171; BD | PLA |

| SV40 T antigen | Mouse | sc-147; Santa Cruz Biotechnology | IF |

| VPS35 | Rabbit | Ab157220; Abcam | WB |

| Other antibodies | Species | Catalog no./source | Application |

| Anti-mouse IgG peroxidase | Goat | A4416; Millipore Sigma | WB |

| Anti-rabbit IgG peroxidase | Goat | A4914; Millipore Sigma | WB |

| Anti-rat IgG peroxidase | Rabbit | A5795; Millipore Sigma | WB |

| Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 | Goat | A11008; Thermo Fisher Scientific | IF |

| Anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 | Goat | A11032; Thermo Fisher Scientific | IF |

| Normal rabbit IgG | Rabbit | NI01; Millipore Sigma | IP |

| Inhibitors | |||

| Compound | Solvent | Catalog no./source | Concentration |

| XXI | DMSO | 565790; Millipore Sigma | 1–2 μM |

| NAV | DMSO | SML2238; Millipore Sigma | 10–25 μM |

DNA constructs

The p16sheLL, p5sheLL, and p18sheLL plasmids were gifts from J. Schiller (National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD; Addgene plasmids #37320, #46953, and #37321) and were modified into p5sheLL.L2F, p16sheLL.L2F, and p18sheLL.L2F, respectively, which consist of WT L1 and 3xFLAG-tagged L2 of corresponding HPV types, as previously described (12). The R302/5A mutation in L2 was introduced to p16sheLL.L2F by site-directed mutagenesis. The pcDNA3.1 plasmids expressing GFP with a C-terminal S-tag were used as pseudoviral genomes (reporter plasmids) as previously described (11). The Gaussia luciferase coding sequence from phGluc (Addgene plasmid #22522) was cloned into pCINeo-EGFP (obtained from C. Buck, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD; Addgene plasmid #46949), replacing the EGFP sequence, and the resulting construct was used as the reporter of HPV16 PsV for the PLA assay. Alternatively, HPV16 PsV packaging a reporter plasmid pCAG-HcRed (Addgene plasmid #11152) was used for PLA. The COPG1 coding sequence was amplified from complementary DNA (cDNA) of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and cloned into the pFLAG-CMV2 vector in frame with the 5′ FLAG for FLAG-γ1-COP recombinant protein production. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce siRNA-resistant/synonymous mutations on the COPG1 siRNA target site. To generate pCMVTNT-HA-COPG1-mCherry construct, siRNA-resistant COPG1 was cloned into the pCMVTNT-HA-KPNA2 plasmid, a gift from B. Paschal (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA), replacing KPNA2, and an mCherry sequence was inserted before the stop codon of COPG1. COPG1 coding sequence was further removed to generate pCMVTNT-HA-mCherry, which was used as the control vector. HPV16 L2 fragment (amino acids 68 to 473) with 3xFLAG epitope tag was amplified from p16sheLL.L2F and cloned into this pCMVTNT-HA vector to generate the pCMVTNT-HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG construct, and the R302/5A mutation was further introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. pcDNA3.1(−)-EGFP-FLAG was described before (76). All plasmids constructed in this study were verified by sequencing.

Cell culture

HEK 293T [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), catalog no. CRL-3216], HeLa (ATCC, catalog no. CCL-2), and HeLa-S3 (ATCC, catalog no. CCL-2.2) cells were obtained from ATCC. HeLa-Sen2 cells, a HeLa derivative, were generated as described in (77). HaCaT cells were purchased from AddexBio Technologies. HEK 293TT cells were obtained from C. Buck (National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD). All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. HeLa cells (ATCC, catalog no. CCL-2) were used throughout this study unless otherwise specified.

HPV PsV production

HPV PsVs were produced by cotransfecting HEK 293TT cells with indicated reporter plasmid and p16sheLL.L2F (WT or R302/5A), p5sheLL.L2F, or p18sheLL.L2F using polyethyleneimine (PEI; Polysciences Inc.). Packaged PsVs were purified by density gradient centrifugation in OptiPrep (Millipore Sigma) as described (34, 35). The purified PsVs were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining for L1 and L2 to assess the quality. Encapsidated reporter plasmids of equivalent amount of WT and R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV were quantified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using primers for the reporter gene to validate that equivalent numbers of plasmid were encapsidated.

Sucrose gradient fractionation

The protocol for sucrose gradient fractionation to isolate TGN/Golgi-containing cellular fractions was shared by Y. Wang (University of Michigan) (78) and adapted for our purposes. HeLa cells were plated in 15-cm plates and grown to ~80% confluency. Cells were then infected with equivalent amounts of WT HPV16.L2F PsV [~100 μg of PsV per 15-cm plate; multiplicity of infection (MOI), ~4], R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV, or left uninfected. A total of 12 15-cm plates per condition were processed as follows. At 22 hpi, cells were washed once with 500 mM NaCl to remove residual virus followed by three ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) washes. Cells were resuspended in HBS buffer [10 mM Hepes (pH 7.2), 1 mM Mg(OAc)2, 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)] and homogenized by passing 20 times through an 8-μm clearance ball-bearing homogenizer (Isobiotech). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000g for 10 min, and the resulting supernatant was layered over a sucrose gradient composed of 1-ml 1.6 M, 1-ml 1.4 M, 2-ml 1.2 M, 3-ml 1.0 M, 2-ml 0.8 M, and 1-ml 0.5 M sucrose in MEB buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl, 20 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 15 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT] supplemented with 250 mM KCl. The sucrose gradients were ultracentrifuged at 30,000 rpm in a SW40Ti swinging-bucket rotor (Beckman) at 4°C for 20 hours. After centrifugation, 12 fractions were collected from top to bottom. A portion of each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting to identify the TGN/Golgi-containing fractions.

Immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry using pooled sucrose fractions

Samples from fractions 3 to 5 (TGN/Golgi-containing fractions) were pooled, incubated with 1% Triton X-100 on ice for 10 min, and centrifuged at 16,100g for 10 min. The resulting supernatants were collected, and ~150 ng of WT HPV16.L2F PsV was added per 1 ml of the uninfected sample lysate (called control). The samples were then incubated with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (~8 μg of antibody per 1 ml of lysate) (F3165; Millipore Sigma) at 4°C overnight, and the immune complex was captured with protein G–coated magnetic beads (Invitrogen, 10003D) at 4°C for 1 hour. Beads were washed four times with 0.1% Triton X-100 in HBS buffer. Bound proteins were eluted with 1% SDS in HN buffer (50 mM Hepes and 150 mM NaCl) and denatured by incubating at 90°C for 10 min. A portion of eluate was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting to confirm that equivalent amounts of L2-3xFLAG were precipitated from WT or R302/5A-infected conditions or control. The remaining eluate was treated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and incubated on ice for 10 min. The sample was subjected to centrifugation, and the precipitated material washed twice with acetone. The precipitate was subject to mass spectrometry analysis at the Taplin Mass-Spectrometry Core Facility (Harvard Medical School). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed using an Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Proximity ligation assay

HeLa-Sen2 or HeLa-S3 cells (5 × 104) were seeded onto glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. After overnight incubation, the cells were infected with equivalent amounts of WT (MOI, ~100) or R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV or left uninfected. In Fig. 2G, cells were treated with 2 μM XXI or an equivalent volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (as a vehicle control) 0.5 hours before infection with HPV16.L2F PsV. In Fig. 6 (A to D), cells were transfected with 2 nM siRNA 18 hours before infection with HPV16.L2F PsV. At 24 or 30 hpi, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized with 0.1% saponin, and incubated with mouse anti-L1 antibody (1:1000 to 2500 dilution) and with rabbit anti-TGN46 antibody (1:200 to 1000 dilution), rabbit anti–γ-COP antibody (1:2000 dilution), or rabbit anti-GM130 antibody (1:100 dilution) at 4°C overnight. PLA was performed with Duolink reagents (Millipore Sigma) as described before (39). Briefly, cells were incubated with PLA probes in a humidified chamber for 1 hour at 37°C. Ligation was performed for 45 min at 37°C, and amplification was performed for 3 hours at 37°C. Coverslips were mounted with mounting medium containing DAPI (Abcam, ab104139) and visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Images were processed by ZEN software (Zeiss) and quantitatively analyzed by Fiji software (79) to measure the total fluorescence intensity per cell in each sample. All PLA experiments were performed independently at least two (in most cases three) times with similar results. Because it is difficult to directly compare the quantitative results between experiments, datapoints are shown with the means and SDs from one representative independent experiment. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance.

siRNA transfection

siRNA oligos used in this study are listed in the Table 2. Six- or 12-well plates were seeded with 1 to 3 × 105 HeLa or HaCaT cells per well and simultaneously reverse-transfected with indicated siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Table 2. siRNA oligos for gene-KDs.

| siRNA | Sequence | Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Scr | Predesigned | QIAGEN; catalog no. 1027281 |

| COPA | CCAUUGAUCCCACUGAGUUCA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| COPB1 | UACGUUAAUUAACGUGCCAAU | Sigma-Aldrich |

| COPB2 | CCCAUUAUGUUAUGCAGAU | Sigma-Aldrich |

| COPD (ARCN1) | GAAAGUUGUUUGUCCGUAU | Sigma-Aldrich |

| COPE | ACGAGCUGUUCGACGUAAA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| COPG1 | CUUGUAAUCUGGAUCUGGA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| COPG2 | CCGAAUUGCCAGUCGCUUA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| COPZ1 | GGGAAUAGUUCAUAGGGAA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| COPZ2 | GGGCUCAUCCUACGAGAAU | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Pooled COPG1 | GAGGGUGGCUUUGAGUAUA; GCAAACACGCCGUCCUUAU; GAAGAGGCUGUGGGUAAUA; GGAGGCCCGUGUAUUUAAU | Dharmacon |

| Pooled Scr | UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUAC; AUGUAUUGGCCUGUAUUAG; AUGAACGUGAAUUGCUCAA; UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA | Dharmacon |

| SGTA | CAGCCUACAGCAAACUCGGCAACUA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| ARF1 #1 | GGCUUUAGAGCUGUGUUGA | Sigma-Aldrich |

| ARF1 #2 | GCCUGAUCCUUCGUGGUGGA | Sigma-Aldrich |

DNA transfection

For KD-rescue experiments, 2.1 × 105 HeLa cells per well were reverse-transfected with 1 nM siRNA of Scr or COPG1 in six-well plates for 9 hours. Attached cells were washed with PBS twice and then transfected with 0.7 μg of pCMVTNT-HA-mCherry or 1 μg of pCMVTNT-HA-COPG1-mCherry plasmids for 15 hours using the transfection reagent FuGENE HD (Promega). Transfected cells were washed with PBS twice and infected with WT HPV16.L2F for 48 hours. Infectivity was analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the fraction of GFP-expressing cells among mCherry-expressing or mCherry-negative cells in the same culture. Alternatively, before infection, whole-cell extract of cells with the same treatment was collected for immunoblot analyses. For recombinant protein production, HEK 293T cells were seeded in 10-cm plates for 24 hours to reach ~80% confluency and then transfected with 3 μg of indicated plasmids for 48 hours using the transfection reagent PEI.

Reverse transcription qPCR

qPCR primers used in this study are listed in Table 3. HeLa cells (3 × 105) per well were seeded in six-well plates and simultaneously reverse-transfected with the indicated siRNA. Twenty-four hours later, cells were harvested and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One microgram of RNA from each condition was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad).

Table 3. DNA primers for qPCR analyses.

| Target | Sequence |

|---|---|

| COPA | Fwd: CGTGGAGACAGAAAGGAAGAAG; Rev.: AGGTTTGAGTGGGTGAAATAGG |

| COPB1 | Fwd: CCTGATGCTCCTGAACTGATAC; Rev.: CTCGATCCTGATCTGCATGAAT |

| COPB2 | Fwd: AGCTATTCCCTGCTGGTTTC; Rev.: CAACTCTGGTCCTCTGTTCTTT |

| COPD | Fwd: CATGAGGAGAAGGTGTTCAGAG; Rev.: CTCTTCGGGCCTGTTGTAAT |

| COPE | Fwd: CCTGAGGTGACAAACCGATAC; Rev.: AGCCTGTCAAAGTCGTTCTC |

| COPG1 | Fwd: GAAGAGGGTGGCTTTGAGTATAA; Rev.: TCGATGAACTCGCACAGATG |

| COPG2 | Fwd: CCATGTGAGAGGTCCGATAAAG; Rev.: GCCTGGACCTCACCAATAAA |

| COPZ1 | Fwd: TCTTGCAGTTCTGGGAGTAAAG; Rev.: AGGGAGCATGTGAGCATAATC |

| COPZ2 | Fwd: TTGGTGCTGGACGAGATTG; Rev.: CGCCATCATCTGCCCTAAA |

| GAPDH | Fwd: CCCTTCATTGACCTCAACTACA; Rev.: ATGACAAGCTTCCCGTTCTC |

HPV infectivity

To quantify HPV infectivity by flow cytometry, HeLa or HaCaT cells were treated as indicated and infected with HPV16.L2F, HPV5.L2F, or HPV18.L2F PsV (MOI, <1) containing a GFP reporter construct. Where indicated, inhibitors (XXI or NAV) were added at time of infection. An equivalent volume of the carrier DMSO was added to the control cultures. At 48 hpi, cells were washed with PBS, harvested by trypsinization, and resuspended in PBS containing 2% FBS and DAPI (0.1 μg/ml). For KD-rescue experiments, trypsin without phenol red was used to prevent interference of the mCherry signal. Flow cytometry was performed with a Bio-Rad ZE5 cell analyzer (University of Michigan Flow Cytometry Core Facility). After gating for size and singlets, the population of DAPI-negative cells (~2 × 104 cells) was analyzed for GFP or mCherry fluorescence. Data are presented as the means and SDs of three independent experiments. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance.

To analyze HPV infectivity by immunoblotting, HeLa or HaCaT cells were treated as indicated and infected with HPV16.L2F PsV containing a GFP reporter construct. At 48 hpi, cells were washed with PBS, harvested by scraping, and lysed in HN buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 for 10 min on ice. Cells were centrifuged at 16,100g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was incubated with SDS sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol, denatured by incubating at 90°C for 10 min, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting for GFP.

Membrane integrity

DAPI exclusion as measured by flow cytometry was used to assess membrane integrity. Nonpermeabilized cells were washed with PBS, harvested by trypsinization, and resuspended in PBS containing 2% FBS and DAPI (0.1 μg/ml). Flow cytometry was performed with a Bio-Rad ZE5 cell analyzer (University of Michigan Flow Cytometry Core Facility). After gating for size and singlets, the percentage of DAPI-negative cells was calculated. Data are presented as the means and SDs of three independent experiments. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Cell cycle analysis

DNA content was measured using Hoechst 33342 staining and flow cytometry analysis. Nonpermeabilized cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (10 μg/ml; Bio-Techne) at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were then washed with PBS, harvested by trypsinization, and resuspended in PBS containing 2% FBS. Flow cytometry was performed with a Bio-Rad ZE5 cell analyzer (University of Michigan Flow Cytometry Core Facility). The percentage of cells in G1, S, or G2 + M phases was visibly determined from control cell cultures using FlowJo software (BD). Data from three independent experiments are presented as the percentage of cells in each phase. A two-tailed, paired t test was used to determine statistical significance between the KD and control cells for each cell cycle phase.

SV40 infection

HeLa cells (1 × 105) were seeded onto glass coverslips in a 12-well plate and simultaneously reverse-transfected with siRNA for 24 hours. Cells were then infected with SV40 (MOI, ~0.1) for 24 hours to reach ~10% infection, fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100/tris-buffered saline (TBS)/3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 20 min, and blocked with 0.2% Tween-20/TBS/3% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibody recognizing SV40 large T antigen was diluted in 0.2% Tween-20/TBS/3% BSA and incubated with cells overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibody was also diluted in 0.2% Tween-20/TBS/3% BSA and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Coverslips were mounted with mounting medium containing DAPI (Abcam, ab104139) and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. The number of cells expressing SV40 large T antigen was scored relative to the total number of cells. Data are presented as the means and SDs of three independent experiments. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Immunofluorescence

HeLa cells (1 × 105) were seeded onto glass coverslips in a 12-well plate and treated as indicated. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100/TBS/3% BSA for 20 min, and blocked with 0.2% Tween-20/TBS/3% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies were diluted in 0.2% Tween-20/TBS/3% BSA and incubated overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies were also diluted in 0.2% Tween-20/TBS/3% BSA and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Coverslips were mounted with mounting medium containing DAPI (Abcam, ab104139) and visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss LSM 800 confocal laser scanning microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 40×/1.4 oil differential interference contrast M27 objective). Representative images were chosen out of two independent experiments.

Immunoprecipitation

HeLa cells were grown to ~80% confluency in 10-cm plates and infected with equivalent amounts of WT HPV16.L2F (MOI, <1) or R302/5A HPV16.L2F PsV or left uninfected. For HPV inhibitor experiments, XXI (2 μM) or NAV (20 μM) was added at time of infection. An equivalent volume of the carrier DMSO was added to the control cultures. At the indicated time after infection, cells from one 10-cm plate were washed with PBS three times and lysed in 400 μl of 1% Triton X-100 in HN buffer containing 1 mM PMSF and were incubated on ice for 10 min. For time course immunoprecipitation experiments, the second PBS wash was supplemented with 300 mM NaCl to reduce cell surface–bound HPV before cell lysis. After centrifugation at 16,100g for 10 min, the resulting supernatant was incubated with indicated antibodies (~2.5 μg/ml) at 4°C overnight. The immune complex was captured with protein G–coated magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10003D) at 4°C for 1 hour. Beads were washed with lysis buffer and incubated at 95°C for 10 min in SDS sample buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol.

Biotin peptide pulldown assay

Peptides consisting of the WT HPV16 L2 sequence (TGIRYSRIGNKQTL) or the R302/5A HPV16 L2 sequence (TGIAYSAIGNKQTL) were synthesized with an N-terminal biotin tag (GenScript). Peptides were dissolved in DMSO, and peptide stocks (5 mg/ml) were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. HeLa cells (1 × 106) were plated in 6-cm dishes. Twenty-four hours later, cells were collected by trypsinization, washed with PBS, and lysed with 165 μl of Hepes buffer [1% Triton X-100, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT] supplemented with Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The lysate was incubated on ice for 45 min followed by centrifugation at 14,000g for 15 min. The resulting supernatant was incubated with 10 μg of biotinylated peptide for 2 hours at 4°C. Fifty microliters of streptavidin magnetic beads (Pierce, 88817) were prewashed three times with Hepes buffer and then added to the lysates and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C. The beads were captured and washed three times with Hepes buffer and incubated at 100°C for 10 min in 2× SDS sample buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol. For the biotin peptide pulldown assay using purified FLAG-γ1-COP, same conditions were used except that ~100 ng of FLAG-γ1-COP instead of cellular extracts was incubated with 10 μg of biotinylated peptide and captured with 30 μl of streptavidin magnetic beads.

Preparation of recombinant proteins

Two 10-cm plates of HEK 293T cells transfected with indicated plasmid for 48 hours were harvested and lysed in 1.2 ml of HN buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM PMSF on ice for 20 min. Following centrifugation at 16,100g for 10 min, the resulting supernatant was incubated with anti-FLAG M2 antibody–conjugated agarose beads (Millipore Sigma, A2220) at 4°C overnight. The beads were recovered by centrifugation and washed once with HN buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM PMSF, twice with HN buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM PMSF supplemented with 300 mM NaCl and 2 mM adenosine triphosphate, and then once with HN buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM PMSF. The recombinant proteins were eluted twice with 3xFLAG peptide (150 μg/ml; Millipore Sigma) in HN buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM PMSF at room temperature for 30 min. A portion of the sample was analyzed alongside with BSA under standard concentrations by SDS-PAGE followed by SimplyBlue SafeStain (Invitrogen) to assess the quality and quantity of purified recombinant proteins.

In vitro binding assay

For in vitro binding assay with rat COPI complex, the reconstituted COPI complex purified from rat liver as described in (78) was a gift from Y. Wang (University of Michigan); WT HPV16.L2F PsV particle was prepared as described in the “HPV PsV production” section; EGFP-FLAG was purified from HEK 293T cells with anti-FLAG M2 antibody–conjugated agarose beads, and Amicon Ultracel-10K Centrifugal Filters (Millipore Sigma) was applied to remove 3xFLAG peptide from the EGFP-FLAG eluate. About 1250 ng of rat COPI was incubated with ~300 ng of WT HPV16.L2F PsV or ~300 ng of EGFP-FLAG in the reaction buffer (HN buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100) at 37°C for 45 min with mild agitation. Anti-FLAG M2 antibody–conjugated magnetic beads (Millipore Sigma, M8823) were added to the reaction for a further incubation at room temperature for 30 min with mild agitation. Beads were recovered and washed with reaction buffer and eluted with SDS sample buffer (without reducing agent) at 95°C for 5 min. Eluate was separated from beads and supplemented with 1% 2-mercaptoethanol and incubated at 95°C for another 5 min and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting.

For in vitro binding assay using purified recombinant proteins, ~100 ng of FLAG-γ1-COP was incubated with ~80 ng of HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG, ~80 ng of HA-(Δ1–67) L2-R302/5A-3xFLAG, or ~800 ng of EGFP-FLAG in the reaction buffer (HN buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM PMSF) at 37°C for 1 hour with mild agitation. Anti–γ-COP antibodies were added into reactions for a further incubation at 37°C for 30 min with mild agitation. The immune complex was captured with protein G–coated magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10003D) at 37°C for 20 min. Beads were washed with reaction buffer and incubated at 95°C for 10 min in SDS sample buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol.

Statistical analysis

Quantitation of HPV infectivity by flow cytometry

Flow cytometry data were processed by Everest software (Bio-Rad). After gating for size and singlets, the population of DAPI-negative cells (~2 × 104 cells per condition) was analyzed for GFP or mCherry fluorescence. Data are presented as the means and SDs of three independent experiments. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Quantitation of cell cycle by flow cytometry

DNA content was measured by Hoechst 33342 staining. The percentage of cells in G1, S, or G2 + M phases was visibly determined from control cell cultures using FlowJo software (BD). Data from three independent experiments are presented as the percentage of cells in each phase. A two-tailed, paired t test was used to determine statistical significance between the KD and control cells for each cell cycle phase.

Quantitation of PLA

Images were analyzed by Fiji software (79) to measure the total fluorescence intensity per cell in each sample. Approximately 30 cells from 10 representative images were quantified for each condition. All PLA experiments were performed independently at least two times with similar results. Because it is difficult to directly compare the quantitative results between experiments, data points are shown with the means and SDs from one representative independent experiment. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Quantitation of SV40 infectivity

Images were analyzed by Fiji software (79) to count the number of cells expressing SV40 large T antigen out of the total number of cells. Approximately 5 × 103 cells were analyzed for each condition. Data are presented as the means and SDs of three independent experiments. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Western blot quantification

In Fig. 3F, Western blots from three independent experiments were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The protein band intensity of HA-(Δ1–67) L2-3xFLAG (WT) or HA-(Δ1–67) L2-R302/5A-3xFLAG (R302/5A) was normalized to that of FLAG-γ1-COP in the same precipitated sample. Data represents means normalized to WT and SDs of four independent experiments. A two-tailed, unequal variance t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI150897 and AI064296 (to B.T.), R01AI150897 (to D.D.), and F31AI152365 (to M.C.H.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: M.C.H., T.-T.W., and B.T. Methodology: M.C.H., T.-T.W., and Y.T. Investigation: M.C.H., T.-T.W., and Y.T. Supervision: B.T. and D.D. Writing—original draft: B.T. Writing—review and editing: M.C.H., T.-T.W., Y.T., D.D., and B.T.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S3

Table S1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.C. de Martel, M. Plummer, J. Vignat, S. Franceschi, Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int. J. Cancer 141, 664–670 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC, “Cancers Associated with Human Papillomavirus, United States—2014–2018,” USCS Data Brief, no. 26 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA, 2021).

- 3.J. C. Cardoso, E. Calonje, Cutaneous manifestations of human papillomaviruses: A review. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 20, 145–154 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]