Abstract

The optimization of extraction, chemical characterization, and the evaluation of antioxidant activity and α-amylase inhibition capacities of the cell wall polysaccharides extracted from Aspergillus niger ATCC 1004 were studied in this paper. The response surface methodology through a factorial design of three levels indicated the optimal conditions for extraction: pH 13 and 180 min. Characterization results showed that the polysaccharide is glucogalactan, consisting of β-D-galactose-linked units (1 → 6) and β-D-linked glucose (1 → 3). The antioxidant activity was evaluated through three in vitro assays. It could effectively scavenge DPPH, ABTS and hydroxyl radicals with inhibition rates of 82.12%, 75.87% and 79.24, respectively, at 6.4 mg/mL, which were higher than those of the other polysaccharides. For inhibitory activity against α-amylase, a blocking effect of 53.7% was observed at a concentration of 2 mg/mL. Therefore, the cell wall polysaccharides of Aspergillus niger, (1 → 3)(1 → 6)-β-D-glucogalactan, seem to be a promising source for use as an antioxidant, in addition to holding an in vitro hypoglycemic potential.

Keywords: Polysaccharide, Aspergillus niger, α-amylase, Biological activity

Introduction

Polysaccharides are abundant in nature in different structures, chemical compositions, degrees of branching, bond types and molecular weights. Its action is closely associated with such aspects (Hajji et al. 2019). In addition, they have the particularity of being biodegradable and renewable. These characteristics contribute to their being one of the most important biomolecules in life sciences and becoming an object of study in the search for new applications, being widely explored after the development of biotechnology (Li et al. 2018).

Among the natural polysaccharides, plants are the most studied source, followed by fungi (Ren et al. 2019a, b). In fungi, these biomolecules participate as a component of the cytosol and cell wall and as an excreted polysaccharide. β-Glucans are the predominant form found (Feofilova 2010). Filamentous fungi are a promising source of polysaccharides and stand out in addition to demonstrating considerable biological activities, being easy to obtain, their production being easily controlled and applicable at an industrial level and having low toxicity (Darwesh et al. 2018).

The more recently disclosed and visionary polysaccharide application is related to medical-pharmaceutical practice (Yu et al. 2018), and they hold interest in clinics due to their usage in different pathologies, acting as anti-inflammatory (Hou et al. 2020), antitumor (Zhu et al. 2020), promising immunomodulators (Staczek et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2017) and antioxidant agents (Ma et al. 2020).

The Aspergillus genus is widely studied for biotechnological applications. Xie et al. (2022) reported of polysaccharides of Aspergillus cristatus, the ability to strengthen immune function, exhibit immunomodulatory activity, attenuate intestinal injury and improve intestinal barrier function, balance intestinal microbiota dysbiosis and maintain intestinal homeostasis. An extracellular branched galactomannan obtained from the species Aspergillus terreus exhibited antioxidant activity (Wang et al. 2013).

This study aimed to optimize extraction using RSM to purify and characterize Aspergillus niger cell wall polysaccharides using spectroscopy and chemical techniques. Studies on antioxidant activity and amylase inhibiting capacity provide a basis for future studies related to means of altering oxidative and digestive processes.

Materials and methods

A. niger culture conditions

A. niger was incubated in potato dextrose agar medium for 5 days at 30 °C for its activation (BOD SL200/90 Incubator—SOLAB). Subsequently, fermentation was continued in liquid medium, pH 5.0, containing 10 g/L D-glucose, 3 g/L yeast extract, 3 g/L malt extract, and 5 g/L peptone dissolved in 125 mL distilled water, following the methodology described by Chang et al. (2018). The flasks were incubated with three 2-cm discs carrying the microorganism. Fermentation was performed at 150 rpm for 120 h in a rotary mixer (Shaker incubator SL 222, SOLAB). The medium liquid culture was then vacuum-filtered (vacuum filtration pump TE-0582, TECNAL), and the biomass was dried in a standard laboratory oven at 50 °C for subsequent biopolymer extraction (Dong et al. 2009).

A. niger polysaccharide extraction

The dried biomass powder (1 g) was extracted using 50 mL of sodium hydroxide solution at different pH values (11, 12 and 13) and extraction times (60, 120 and 180 min). The suspension was centrifuged (206BL-EXCELSA Model) at 3600 rpm for 15 min. The precipitate was discarded, and 3 times the volume of absolute ethanol was added to the supernatant, which was energetically stirred and allowed to stand overnight at 4 °C. The precipitated polysaccharides were isolated by centrifugation at 3600 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The crude polysaccharide precipitate was dried at 50 °C until constant weight. The biopolymers were measured by the phenol‒sulfuric acid method. The yield of polysaccharide was measured by the following equation:

Experimental design

A three-level factorial design from the response surface methodology (RSM) was applied, with two independent variables (pH and extraction time) that were studied in three variation levels, and the central point for the pH value was equal to 12 and 120 min for extraction time. All the calculations and graphs were built using Statistica™ software version 10.0, including the analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Medium molecular weight (MWn) and degree of polymerization (DPn)

The MWn and DPn were calculated through the methodology proposed by Vettori et al. (2012) from the measure of the reducing sugar value using 3,5-dinitrosalicyclic acid (DNS) according to Miller (1959) and the total carbohydrate dosage by phenol‒sulfuric acid according to DuBois et al. (1956). Equation of Vettori et al. (2012):

Polysaccharide purification

The polysaccharide sample (15 mg/mL) was applied to a 30 × 1.0 cm Sephadex™ G-100 column (Sigma™, EUA) previously equilibrated in sodium citrate–phosphate buffer (0.05 mol L-1, pH 7.0), which was also used as the mobile phase. The fractions (1.5 mL) were collected, and the total polysaccharides in each fraction were measured using the phenol‒sulfuric acid methodology (DuBois et al. 1956).

Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and 1H and.13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

The biopolymers were characterized using FTIR (Varian Inova 500 model). The dried polymer was milled and pressed into pellets for FTIR spectral measurements in the frequency interval ranging from 4000 to 500 cm−1, with 20 scans. 1D and 2D NMR spectra, including 1H, 13C, 1H-13C heteronuclear singular quantum correlation (HSQC), were obtained using spectra at 343 K in a Varian Inova 500 spectrometer that works at 11.7 T, examining 1H at 500 MHz and 13C at 125 MHz, through a direct probe. The sample was dissolved in a D2O/DMSO (6:1) solvent system and transferred to an NMR tube. DMSO was used as a reference for chemical change.

Polysaccharide monomeric composition

The A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide (20 mg) was hydrolyzed with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at 90 °C for 8 h, followed by evaporation (Ruthes et al. 2013). After hydrolysis, the remaining powder was solubilized in ultrapure water, and the solution was filtered and then analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an Aminex™ column HPX-87H (300 mm × 7.8 mm i.d.) (9 μm) (BIO-RAD, California, EUA), and refractive index detector. The injection volume was 20 µL. A 0.01 N H2SO4 solution was used as the mobile phase in isocratic mode at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 25 °C. The following sugar reference standards were applied for the identification of the retention peaks: glucose, rhamnose, galactose, mannose, arabinose and xylose, all of which underwent hydrolysis treatment identical to that received by the polysaccharide. The monosaccharide composition was determined in two independent experiments with consistent results.

Evaluation of antioxidant activity

DPPH free radical scavenging assay

The DPPH scavenging activity of polysaccharide samples was examined according to the previous method described by Brand-Williams et al. (1995), with modifications. In the assay, 100 µL of sample (0.8, 1.6, 2.4, 3.2, 4.0, 4.8, 5.6 and 6.4 mg/mL) was added to 3.9 mL of a DPPH methanolic solution (0.06 mM). After 20 min at 25 °C, the absorbance was assessed at 517 nm. The DPPH radical scavenging activity was calculated by the following equation:

where A0 represents the absorption of the negative control (DPPH system with sample solvent) and A1 represents the absorption of the DPPH system with sample addition. The antioxidant activity was measured using Trolox as a positive control.

ABTS radical scavenging assay

The ABTS radical scavenging of polysaccharides was assessed with the method of Re et al. (1999) with modifications. The radical was previously prepared by reaction of ABTS salt (7 mM) with potassium persulfate (2.45 mM) and keeping the mixture protected with light at room temperature for 16 h before use. The stock ABTS+ solution was diluted in ethanol (0.7 ± 0.005 absorbance) and incubated with 30 µL of the sample (0.8, 1.6, 2.4, 3.2, 4.0, 4.8, 5.6 and 6.4 mg/mL) and 3 mL of the ABTS ethanolic solution. Absorbance was assessed at 734 nm after 6 min of incubation. Trolox was used as a positive control. The scavenging rate was calculated with the following equation:

where A0 represents the absorption of the negative control (ABTS system with sample solvent) and A1 represents the absorption of the ABTS system with sample addition.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was examined according to the method reported by Jing et al. (2018). One milliliter of ferrous sulfate (9 mmol/L) was mixed with 1 mL salicylic acid (9 mmol/L), 1 mL polysaccharide sample solution with different concentrations (0.8, 1.6, 2.4, 3.2, 4.0, 4.8, 5.6, 6.4 mg/mL) and 1 mL of hydrogen peroxide (8.8 mmol/L). The reaction was incubated in a water bath (37 °C) for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 510 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The scavenging rate was calculated with the following equation:

where A0 represents the absorption of the negative control and A1 represents the absorption of the system with sample addition.

Evaluation of α-amylase inhibitory capacity

The α-amylase inhibitory activity was estimated according to the method described by Chen et al. (2013), with modifications: 0.1 mL of porcine pancreatic α-amylase solution (2 mg/mL) in citrate–phosphate buffer (2 mg/mL, pH 6) was added to 0.1 mL of polysaccharide solution at different concentrations (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/mL), and subsequently, 0.1 mL of starch solution was added (1.0 mg/mL). The reactional mixture was then incubated at 50 °C for 10 min. The reactional process was interrupted for the accretion of 0.02 mL of DNS, and consecutively, it was placed in a water bath at 100 °C for 5 min. The reaction mixture was diluted by adding 2 mL of distilled water, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. Acarbose was used as a positive control.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD) based on independent experiments. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were detected by ANOVA and Tukey’s post-test using GraphPad™ 7.00.

Results and discussion

Polysaccharide extraction

The three-level factorial design was applied to set up the best conditions for A. niger polysaccharide extraction. The experimental results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Three-level factorial design applied for the determination of the optimum conditions for time and pH in the A. niger polysaccharides extraction

| Experiment | Time (min) | pH | Observed yield (%) | Estimated yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 180 ( + 1) | 11 ( – 1) | 3.48 | 3.37 |

| 2 | 180 ( + 1) | 12 (0) | 4.56 | 4.98 |

| 3 | 180 ( + 1) | 13( + 1) | 7.30 | 6.98 |

| 4 | 120 (0) | 11 ( – 1) | 2.94 | 2.76 |

| 5C | 120 (0) | 12 (0) | 3.60 | 3.54 |

| 5C | 120 (0) | 12 (0) | 3.40 | 3.54 |

| 5C | 120 (0) | 12 (0) | 3.70 | 3.54 |

| 6 | 120 (0) | 13(+ 1) | 4.48 | 4.72 |

| 7 | 60 ( – 1) | 11 ( – 1) | 2.38 | 2.65 |

| 8 | 60 ( – 1) | 12 (0) | 2.96 | 2.60 |

| 9 | 60 ( – 1) | 13 ( + 1) | 2.88 | 2.95 |

The coded values are shown in parentheses

C central point

Based on the results obtained through RSM using two independent variables (pH and extraction time) in three levels, which totaled 11 experiments, surface and area graphics were built and are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Response surface plots and area showing the effects of time and pH on the yield of A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide a Response surface graphic b Area graphic

After the analysis of the response surface graphic (Fig. 1), it was possible to determine that the ideal extraction point in the experimental scope was 180 min and 13 for time and pH, respectively, thereby providing a polysaccharide maximum yield of approximately 7.3%. A study by Wu et al. (2016) with polysaccharides isolated from Paecilomyces hepialid showed a yield of 11.08% during the extraction under the conditions of 9 °C for temperature and 190 min for time, using water as a solvent. These results are similar to those found in this study; however, for A. niger polysaccharides, the extraction conditions were different concerning the solvent, which could explain the difference.

The quadratic function originated after the application of the three-level factorial design that describes the behavior of pH and time and regarding total yield is described in the equation:

Yield (%) = (39.093 ± 13.826) – (0.163 ± 0.016)T – (5.470 ± 2.309)pH + (0.199 ± 0.096)(pH)2 + (0.014 ± 0.001)(T)(pH)

where T is the temperature in °C.

Table 2 shows the analysis of variance (ANOVA) obtained from the evaluation of time and pH in A. niger polysaccharide extraction.

Table 2.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for time and pH optimization of the A. niger polysaccharides extraction

| Variation Source | SS | DF | MS | Fcalculated | Ftable | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 17.2786 | 5 | 3.4557 | 27.40 | 5.50 | 0.96 |

| Residue | 0.6305 | 5 | 0.1261 | |||

| Lack-of-fit | 0.5838 | 3 | 0.1946 | 8.34 | 19.16 | |

| Pure Error | 0.0467 | 2 | 0.0233 | |||

| Total SS | 17.9091 | 10 |

SS Square Sum; DF Degrees of Freedom; MS Mean Square

In view of Table 2, it can be deduced that the model is well fitted, showing an Fcalculated greater than Ftable for the regression (27.40 > 5.50), with a confidence interval of 95%. The resulting coefficient of determination, R2, was 0.96, which means that 96% of the results can be explained by the experimental model. The model did not show lack-of-fit, since Fcalculated is lower than Ftable (8.34 < 19.16). Therefore, the results point to a representative statistical treatment, they are trustworthy, and the optimized conditions can be used for A. niger polysaccharide extraction, providing a superior yield.

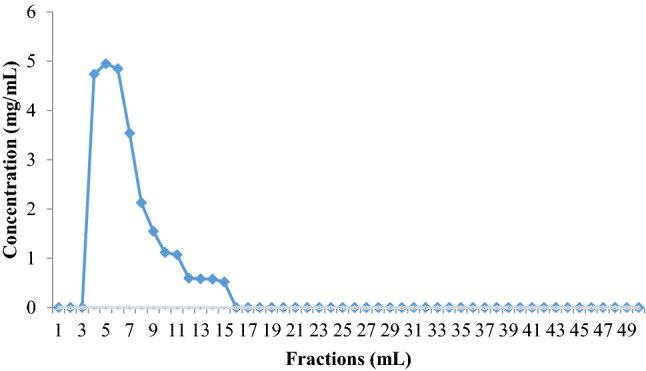

Polysaccharide purification

Chromatography in a Sephadex™ G-100 column was used for the purification process, and the results showed the presence of only one simetric peak (Fig. 2). Such data indicated the occurrence of only one type of polysaccharide, with the degree of polymerization and molecular weight estimated to be 23 and 375 × 107 Da, respectively, according to the methodology of Vettori et al. (2012).

Fig. 2.

Elution profile of A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide in Sephadex™ G-100 column previously equilibrated in sodium citrate–phosphate buffer (pH 7.0)

Different chromatographic techniques are applied with the purpose of isolating polysaccharides from other types of polysaccharides or from impurities. Gel filtration chromatography is a purification method for neutral and anionic polymers; it is widely used and presents a satisfactory response. Biopolymer separation occurs according to its molecular weight and hydrodynamic volume (Valasques Junior et al. 2017).

Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Figure 3 shows the spectroscopic profile in the infrared region that allowed the identification of the functional group characteristics of polysaccharides.

Fig. 3.

FT-IR spectrum of A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide

It is possible to affirm from the spectrum analysis that bands in the range from 3238 cm−1 refer to an -OH axial stretching (Valasques Junior et al. 2017); the signal at 2921 cm−1 is related to a -CH axial stretching, and the one at 1637 cm−1 is credited to the -HOH folding vibration (Guo et al. 2013); the -CH2 group flexion vibration is observed at 1325 cm−1 (Wang et al. 2017), and the band in the 1000–1200 cm−1 region is attributed to the axial deformation vibration of the -COC group existing in a carbon six atoms ring characteristic of polysaccharides (Valasques Junior et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018). The band at approximately 532 cm−1 is characteristic of glucan-type carbohydrates (Synytsya and Novak 2014). The band 775.53 cm-1 is found in an anomeric region of the fingerprint (950–750 cm-1) (Arunkumar et al. 2021).

Analysis of monomeric composition

The polysaccharide was hydrolyzed by TFA and analyzed by HPLC associated with a refractive index detector (HPLC-RI), which revealed its monomeric composition (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

HPLC-RI chromatogram of A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide monomeric composition

Distinct retention peaks were observed related to different sugars available in the biopolymer composition of A. niger. Comparing the polysaccharide sample with the standard retention times, it is proposed that its monomeric composition is galactose (9.5 min) and glucose (8.8 min). The retention time of 18.1 min was characteristic of the galactose reference standard as for that of glucose.

Lu et al. (2017) studied the sulfated polysaccharide structure of Antrodia cinnamomea and identified the predominance of the monosaccharides galactose and glucose, as well as in this research, characterizing it as a glucogalactan.

NMR spectroscopy

The HSQC results (Fig. 5a) showed signals at δ 104.0/5.42 (C1/H1), δ 69.3/3.73 (C2/H2), δ 80.2/3.98 (C3/H3), δ 72.0/4.14 (C4/H4), δ 71.2/3.65 (C5/H5) and δ 63.1/3.76/387 (C6/H6a/H6b), corresponding to (1 → 6)-β-D-Gal units. Moreover, HSQC (Fig. 5a) also showed β-D-Glu signals at δ 107.5/5.21 (C1/H1), δ 72.00/3.85 (C2/H2), δ 84.2/4.41 (C3/H3), δ 72.03/4.00 (C4/H4), δ 72.1/4.10 (C5/H5), and δ 63.4/3.70/3.75 (C6/H6a/H6b), corresponding to (1 → 3)-β-D-linked units (Mirzadeh et al. 2019; Valasques Junior et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2018).

Fig. 5.

2D NMR analysis results of A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide a HSQC spectrum b Proposed structure of A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide Glu: Glucose Gal: Galactose

Therefore, according to these results, based on analysis of the composition of monosaccharides, IR and HSQC, the polysaccharide is a substituted glucogalactan consisting of β-D-galactose with linkages (1 → 6) and β-D-glucose with linkages (1 → 3). The repeat unit of the primary structure in polysaccharides was proposed and is shown in Fig. 5b.

Antioxidant activity

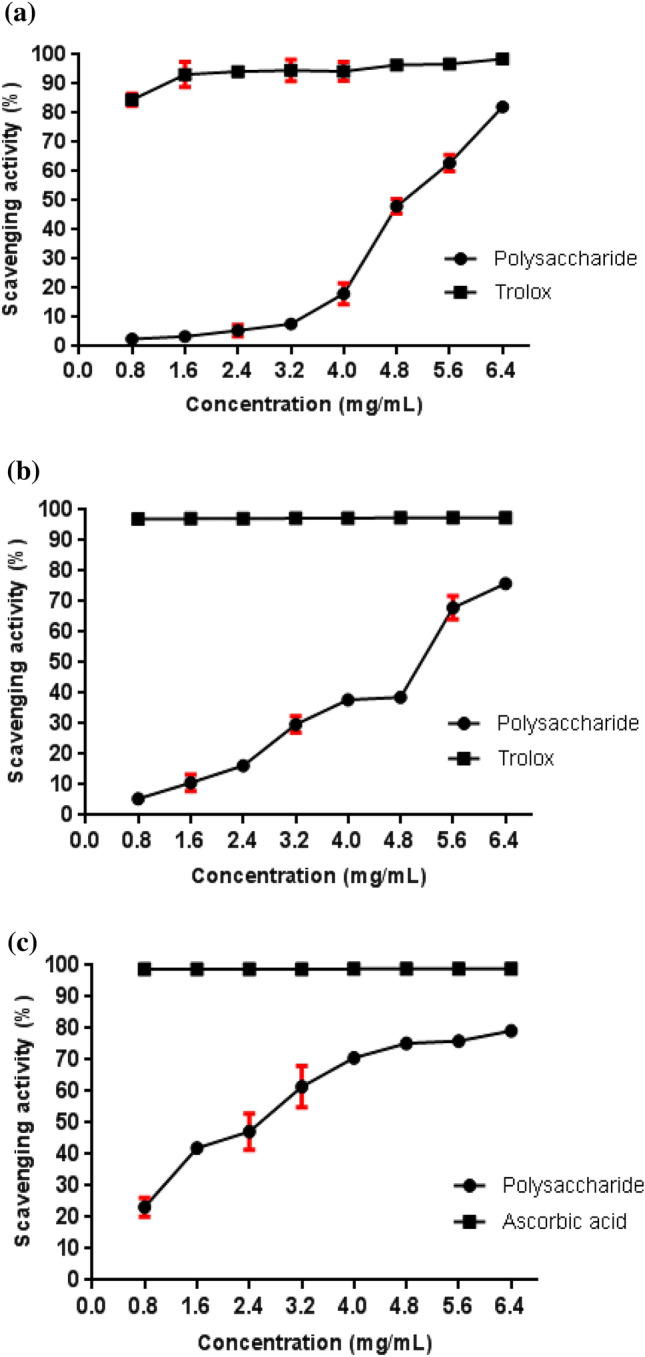

DPPH is a relatively unstable free radical that can accept a hydrogen atom or electrons to form a stable molecule. For that reason, it is extensively used for the evaluation of free radical clearance activity (Qu et al. 2016).

Figure 6a shows that the DPPH free radical-scavenging activity was concentration dependent. At the greater concentration (6.4 mg/mL), the polysaccharide and Trolox clearance activities were 82.12% and 98.51%, respectively. These results indicate that the biopolymer in this study exhibits antioxidant potential in scavenging DPPH free radicals, thus confirming its antioxidant activity.

Fig. 6.

Scavenging effects of A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide compared with positive control a DPPH assay b ABTS radicals assay c Hydroxyl radical scavenging

In their study with polysaccharides extracted from Bletilla striata, Qu et al. (2016) found a DPPH clearance activity of approximately 40% at a concentration of 5 mg/mL, while the polysaccharide in this study demonstrated, at a concentration of 4.8 mg/mL, an activity near 50%, showing superior activity when compared with their research. Wang et al. (2013) identified a DPPH radical-scavenger activity of 79.1% in Aspergillus terreus polysaccharides at a concentration of 6.0 mg/mL, which is a very close value to that found for the A. niger polysaccharide at a similar concentration.

The ABTS radical is commonly used for antioxidant activity evaluation of natural extracts (Ye et al. 2016). From the graphic below (Fig. 6b), it can be highlighted that the capacity to scavenge ABTS free radicals was also polysaccharide concentration dependent. The ABTS radical clearance maximum activity was achieved at 6.4 mg/mL, where it reached 75.94% of activity.

In a study with Hohenbuehelia serotine polysaccharide conducted by Li and Wang (2016), a maximum ABTS free radical-scavenging activity of approximately 50% was obtained at 6.0 mg/mL, and A. niger polysaccharide demonstrated an activity value close to 70% at the same concentration, highlighting a greater antioxidant potential.

Hydroxyl radicals are highly active and can react with practically any biomolecule, causing severe damage to tissues and organs (Mirzadeh et al. 2019). The removal of hydroxyl radicals is important for protecting vital systems. Therefore, polysaccharides can be a viable alternative since they donate electrons or hydrogen atoms to eliminate hydroxyl radicals (Khaskheli et al. 2015). The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of A. niger polysaccharide is shown in Fig. 6c.

An increase in the concentration of polysaccharides could significantly improve the inhibition rate of hydroxyl radicals. The activity of polysaccharides at a concentration of 4.0 mg/mL was 70.66%, higher than that reported by Ren et al. (2019a, b), in which the polysaccharides presented 34.43 and 35.62% activity at the same concentration.

The presence of carboxyl groups in polysaccharides gives these biomolecules a chelating capacity and consequently antioxidant activity. A greater hydroxyl sequestering effect and reducing power depends both on the number of hydroxyls and their position in the molecule (Wang et al. 2016).

The polysaccharide exhibited a variable degree of free radical eliminating activity in a concentration-dependent way for both antioxidant activity tests and was demonstrated to be a promising tool for its use as an antioxidant, and it should be explored with this purpose.

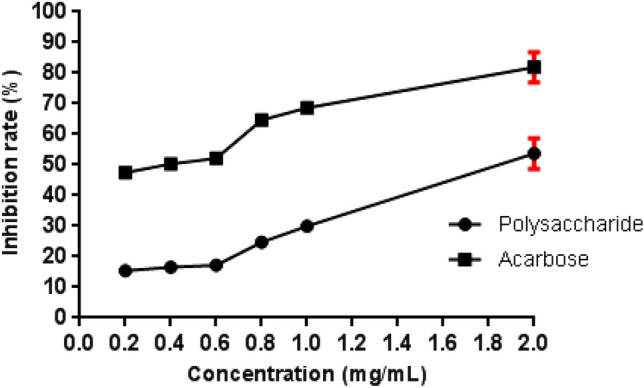

Evaluation of α-amylase inhibitory capacity

Attention has been directed to α-amylase natural inhibitors due to their use as hypoglycemiant agents. This is explained by the fact that α-amylase inhibitors can delay carbohydrate absorption since they diminish the release of glucose from starch, inhibiting the activity of carbohydrate hydrolyzing enzymes in the small intestine (Xu et al. 2018).

The inhibitory activity of A. niger polysaccharide and acarbose on α-amylase was assessed, and the results are shown in Fig. 7. The evaluated sample had a dose-dependent blocking effect on α-amylase, as evidenced by 53.7% inhibition at the greater concentration (2 mg/mL), but was lower than that of the positive control acarbose at the same concentration, since it presented an activity of 81.8%.

Fig. 7.

α-Amylase inhibition capacity by A. niger ATCC 1004 polysaccharide

Wang et al. (2018) assessed the α-amylase inhibitory capacity of an exopolysaccharide from Lachnum sp. filamentous fungus before chemical modification, demonstrating inhibition of approximately 55% at 5 mg/mL. This result was close to the result found in this study, but at a lower concentration.

Conclusions

The three-level factorial experimental design allowed us to establish the optimal conditions for extraction, 180 min for time and 13 for pH. The chemical characterization suggested that the sample extracted from the Aspergillus niger cell wall is glucogalactan, consisting of (1 → 6)-linked β-D-galactose units branched and (1 → 3)-linked β-D-glucose, with a molecular weight equal to 375 × 107 Da. In addition, the polysaccharide had a strong antioxidant capacity. The α-amylase inhibition assay also exhibited significant results when compared with other research, and more detailed studies should be carried out on its hypoglycemiant activity. Hence, the polysaccharide extracted from the Aspergillus niger ATTC 1004 cell wall was demonstrated to be a product with possible biological use regarding its action in biochemical disorders associated with oxidative stress.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank State University of Southwest Bahia (UESB), Coordination for Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Bahia Research Support Foundation (FAPESB), and Multicentric Program in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (PMBqBM-UESB).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

Footnotes

Access number: Aspergillus niger ATCC 1004 [40018] – Coleção de Micro-organismos de Referência em Vigilância Sanitária da Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Access number in other collections: ATCC 1004, CBS 104.57.

References

- Arunkumar K, Raja R, Kumar VB, Joseph A, Shilpa T, Carvalho IS. Antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of sulfated polysaccharides from five different edible seaweeds. J Food Measure Charact. 2021;15(1):567–576. doi: 10.1007/s11694-020-00661-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset CLWT. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 1995;28(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YH, Chang KS, Chen CY, Hsu CL, Chang TC, Jang HD. Enhancement of the efficiency of bioethanol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae via gradually batch-wise and fed-batch increasing the glucose concentration. Fermentation. 2018;4(2):45. doi: 10.3390/fermentation4020045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Chen H, Tian J, Wang Y, Xing L, Wang J. Chemical modification, antioxidant and α-amylase inhibitory activities of corn silk polysaccharides. Carbohyd Polym. 2013;98(1):428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwesh OM, Sultan YY, Seif MM, Marrez DA. Bio-evaluation of crustacean and fungal nano-chitosan for applying as food ingredient. Toxicol Rep. 2018;5:348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CH, Xie XQ, Wang XL, Zhan Y, Yao YJ. Application of Box-Behnken design in optimisation for polysaccharides extraction from cultured mycelium of Cordyceps sinensis. Food Bioprod Process. 2009;87(2):139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2008.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PT, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28(3):350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feofilova EP. The fungal cell wall: modern concepts of its composition and biological function. Microbiology. 2010;79(6):711–720. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Mao W, Li Y, Gu Q, Chen Y, Zhao C, Li N, Wang C, Liu X. Preparation, structural characterization and antioxidant activity of an extracellular polysaccharide produced by the fungus Oidiodendron truncatum GW. Process Biochem. 2013;48(3):539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2013.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajji M, Hamdi M, Sellimi S, Ksouda G, Laouer H, Li S, Suming Li, Nasri M. Structural characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of a novel polysaccharide from Periploca laevigata root barks. Carbohyd Polym. 2019;206:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C, Chen L, Yang L, Ji X. An insight into anti-inflammatory effects of natural polysaccharides. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;153:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing H, Zhang Q, Liu M, Zhang J, Zhang C, Li S, Ren Z, Gao Z, Liu X, Jia L. Polysaccharides with antioxidative and antiaging activities from enzymatic-extractable mycelium by Agrocybe aegerita (Brig.) Sing. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/1584647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaskheli SG, Zheng W, Sheikh SA, Khaskheli AA, Liu Y, Soomro AH, Feng X, Sauer MB, Wang YF, Huang W. Characterization of Auricularia auricula polysaccharides and its antioxidant properties in fresh and pickled product. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;81:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wang L. Effect of extraction method on structure and antioxidant activity of Hohenbuehelia serotina polysaccharides. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;83:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Niu Y, Xing P, Wang C. Bioactive polysaccharides from natural resources including Chinese medicinal herbs on tissue repair. Chin Med. 2018;13(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13020-018-0166-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MK, Lin TY, Hu CH, Chao CH, Chang CC, Hsu HY. Characterization of a sulfated galactoglucan from Antrodia cinnamomea and its anticancer mechanism via TGFβ/FAK/Slug axis suppression. Carbohyd Polym. 2017;167:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.02.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JS, Liu H, Han CR, Zeng SJ, Xu XJ, Lu DJ, He HJ. Extraction, characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from Pouteria campechiana seed. Carbohyd Polym. 2020;229:115409. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31(3):426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh M, Arianejad MR, Khedmat L. Antioxidant, antiradical, and antimicrobial activities of polysaccharides obtained by microwave-assisted extraction method: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Li C, Zhang C, Zeng R, Fu C. Optimization of infrared-assisted extraction of Bletilla striata polysaccharides based on response surface methodology and their antioxidant activities. Carbohyd Polym. 2016;148:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biol Med. 1999;26(9–10):1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Q, Chen J, Ding Y, Cheng J, Yang S, Ding Z, Dai Q, Ding Z. In vitro antioxidant and immunostimulating activities of polysaccharides from Ginkgo biloba leaves. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;124:972–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Bai Y, Zhang Z, Cai W, Del Rio FA. The preparation and structure analysis methods of natural polysaccharides of plants and fungi: a review of recent development. Molecules. 2019;24(17):3122. doi: 10.3390/molecules24173122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthes AC, Carbonero ER, Córdova MM, Baggio CH, Sassaki GL, Gorin PAJ, Santos ARS, Iacomini M. Fucomannogalactan and glucan from mushroom Amanita muscaria: Structure and inflammatory pain inhibition. Carbohyd Polym. 2013;98(1):761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staczek S, Zdybicka-Barabas A, Pleszczyńska M, Wiater A, Cytryńska M. Aspergillus niger α-1, 3-glucan acts as a virulence factor by inhibiting the insect phenoloxidase system. J Invertebr Pathol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synytsya A, Novak M. Structural analysis of glucans. Ann Transl Med. 2014 doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.02.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valasques Junior GL, Boffo EF, Santos JDG, Brandão HN, Mascarenhas AJ, Cruz FT, Assis SA. The extraction and characterisation of a polysaccharide from Moniliophthora perniciosa CCMB 0257. Nat Product Res. 2017 doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1285302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vettori MHPB, Franchetti SMM, Contiero J. Structural characterization of a new dextran with a low degree of branching produced by Leuconostoc mesenteroides FT045B dextransucrase. Carbohyd Polym. 2012;88(4):1440–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.02.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Mao W, Chen Z, Zhu W, Chen Y, Zhao C, Li N, Yan M, Liu X, Guo T. Purification, structural characterization and antioxidant property of an extracellular polysaccharide from Aspergillus terreus. Process Biochem. 2013;48(9):1395–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2013.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Hu S, Nie S, Yu Q, Xie M. Reviews on mechanisms of in vitro antioxidant activity of polysaccharides. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/5692852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Shao C, Liu L, Guo X, Xu Y, Lü X. Optimization, partial characterization and antioxidant activity of an exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus plantarum KX041. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;103:1173–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hou G, Li J, Surhio MM, Ye M. Structure characterization, modification through carboxymethylation and sulfation, and in vitro antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of a polysaccharide from Lachnum sp. Process Biochem. 2018;72:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2018.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Zhang M, Xie M, Dai Z, Wang X, Hu B, Hong Y, Zeng X. Extraction, characterization and antioxidant activity of mycelial polysaccharides from Paecilomyces hepiali HN1. Carbohyd Polym. 2016;137:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Bai Y, Chen G, Dong W, Peng Y, Xu W, Sun Y, Zeng X, Liu Z. Immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from the mycelium of Aspergillus cristatus, isolated from Fuzhuan brick tea, associated with the regulation of intestinal barrier function and gut microbiota. Food Res Int. 2022;152:110901. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Niu X, Liu N, Gao Y, Wang L, Xu G, Li X, Yang Y. Characterization, antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of degraded polysaccharides from blackcurrant (Ribesnigrum L.) fruits. Food Chem. 2018;243:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.09.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z, Wang W, Yuan Q, Ye H, Sun Y, Zhang H, Zeng X. Box-Behnken design for extraction optimization, characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity of Cicer arietinum L. hull polysaccharides. Carbohyd Polym. 2016;147:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Shen M, Wang Z, Wang Y, Xie M, Xie J. Sulfated polysaccharide from Cyclocarya paliurus enhances the immunomodulatory activity of macrophages. Carbohyd Polym. 2017;174:669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Shen M, Song Q, Xie J. Biological activities and pharmaceutical applications of polysaccharide from natural resources: a review. Carbohyd Polym. 2018;183:91–10. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu D, Fang L, Zhao X, Zhou A, Xie J. A galactomann glucan derived from Agaricus brasiliensis: purification, characterization and macrophage activation via MAPK and IκB/NFκB pathways. Food Chem. 2018;239:603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Qian C, Zhou F, Guo J, Chen N, Gao C, Jin B, Ding Z. Antipyretic and antitumor effects of a purified polysaccharide from aerial parts of Tetrastigma hemsleyanum. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]