Abstract

After ingestion by mosquitoes, gametocytes of malaria parasites become activated and form extracellular gametes that are no longer protected by the red blood cell membrane against immune effectors of host blood. We have studied the action of complement on Plasmodium developmental stages in the mosquito blood meal using the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei and rat complement as a model. We have shown that in the mosquito midgut, rat complement components necessary to initiate the alternative pathway (factor B, factor D, and C3) as well as C5 are present for several hours following ingestion of P. berghei-infected rat blood. In culture, 30 to 50% of mosquito midgut stages of P. berghei survived complement exposure during the first 3 h of development. Subsequently, parasites became increasingly sensitive to complement lysis. To investigate the mechanisms involved in their protection, we tested for C3 deposition on parasite surfaces and whether host CD59 (a potent inhibitor of the complement membrane attack complex present on red blood cells) was taken up by gametes while emerging from the host cell. Between 0.5 and 22 h, 90% of Pbs21-positive parasites were positive for C3. While rat red and white blood cells stained positive for CD59, Pbs21-positive parasites were negative for CD59. In addition, exposure of parasites to rat complement in the presence of anti-rat CD59 antibodies did not increase lysis. These data suggest that parasite or host molecules other than CD59 are responsible for the protection of malaria parasites against complement-mediated lysis. Ongoing research aims to identify these molecules.

Complement is a major component of the innate defense system of vertebrates. It consists of 12 soluble plasma proteins and a number of soluble or membrane-bound regulatory complement control proteins. The complement cascade may be activated by three different routes: the antibody-dependent classical pathway or the antibody-independent alternative and lectin pathways (reviewed in reference 30). However, parasites and other pathogens have developed mechanisms to resist complement attack. Evasion can occur at various steps in the complement cascade and may be accomplished via acquisition of host complement control molecules or by expression of pathogen-specific inhibitors (for reviews, see references 14 and 17).

Although development of malaria parasites is mainly intracellular, parasites are exposed to immune factors of the vertebrate host during extracellular phases of their life, for example, in the mosquito midgut (reviewed in reference 23). When the sexual stages (female and male gametocytes) enter the mosquito midgut, gametogenesis is induced, and within minutes postactivation, the gametes have emerged from red blood cells (4). The extracellular gametes fuse to form a zygote. After 5 to 6 h, a protrusion starts to elongate from the zygote and the parasite develops into a banana-shaped, motile, invasive ookinete, a process which requires 18 to 20 h to complete in Plasmodium berghei (13). From the moment that the parasites leave the red blood cell, they are exposed to immune effector components of host blood present in the mosquito blood meal, such as antibodies, leukocytes, and complement (5, 8, 18, 26).

Little is known about the mechanisms by which malaria parasites evade complement attack or, indeed, whether complement remains active in mosquito blood meals. It was demonstrated that gametes and zygotes of the avian malaria parasite Plasmodium gallinaceum were resistant to damage by the alternative pathway of complement in host (chicken) serum but sensitive to damage by nonhost (including human, sheep, and guinea pig) serum. Experiments on in vitro-cultured zygotes and ookinetes suggested that resistance to lysis by homologous complement was lost 6 to 8 h postinduction of gametogenesis, although if the zygotes were fed to mosquitoes in the presence of native chicken serum, their infectivity declined 2 to 3 h earlier (8, 9). Those authors inferred from their experiments that complement must remain active in the mosquito midgut for 3 to 4 h. Mild trypsin treatment of zygotes reduced the resistance of P. gallinaceum to host complement, indicating the involvement of surface proteins in the resistance mechanism (9).

Studies on the transmission of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium yoelii suggested that this parasite was susceptible to attack by the alternative pathway of mouse complement. Lower levels of infection were obtained in mosquitoes fed on P. yoelii-infected complement-sufficient DBA/1 mice than in those fed on C5-deficient DBA/2 mice, and C3 deposition on zygotes was observed by immunofluorescence (27). In contrast, following gametocyte feeds of P. berghei, no difference was observed between mosquito infections (oocyst numbers) from C5-deficient DBA/2 and complement-sufficient mice (23).

The aim of this study was to investigate complement activity in mosquito blood meals and to analyze the complement sensitivity of mosquito midgut stages of P. berghei. We have investigated for the first time whether, and for how long, components of the alternative pathway of complement (factor B and factor D) remain active in midguts of Anopheles stephensi fed on noninfected or infected Wistar rats. Consumption of C3 and C5 in midgut samples was determined by Western blot analyses, and the susceptibility of P. berghei mosquito midgut stages to the alternative pathway of rat complement was examined during their development in vitro. Under the experimental conditions used, P. berghei macrogametes and zygotes showed resistance to rat complement. To obtain some insight into the molecular mechanism underlying the protection of these stages, we examined the deposition of C3 on the parasite surface and the role of host complement-regulatory molecules in parasite protection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling of mosquito blood meals.

A. stephensi mosquitoes, strain SD500, were maintained under standard conditions (27°C, 80% relative humidity) (22). Starved mosquitoes were fed for 20 min on noninfected or infected male Wistar rats. Immediately postfeeding or at various time points afterwards (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h), 25 or 50 midguts of fully engorged mosquitoes were dissected into 25 or 50 μl, respectively, of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing protease inhibitors (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM; benzamidine, 10 mM [final concentrations]). The midgut contents were released by disrupting the guts with a needle, cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 3 min), and the supernatant was frozen immediately at −70°C. Serum samples of noninfected or infected rats to which protease inhibitors had been added (same final concentrations as stated above) were frozen at −70°C.

Measurement of complement levels in mosquito blood meals. (i) Factor B and factor D activities.

A stable C3 convertase (CVFBb) can be formed from cobra venom factor (CVF) and factor B in the presence of factor D and Mg2+ ions. This feature was exploited to measure factor B and factor D activities in mosquito blood meal samples and to compare these with activities in control rat serum samples (11, 16). CVF at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml (or PBS as a control) was added to 5 μl of rat serum or 5 μl of mosquito sample and incubated for 15 min at 37°C to allow convertase formation. The amount of CVFBb formed depends exclusively on the amount of active factor B and factor D in the sample. Activity of the preformed convertase CVFBb was measured by its ability to convert C3 into C3b. As a source of C3, 2 μl of normal human serum (diluted 1:2 in PBS–20 mM EDTA to prevent any further activation of complement) was added to 2 μl of sample. Samples were again incubated for 15 min at 37°C to allow conversion of human C3 by the preformed CVFBb convertase. Conversion of C3 was analyzed by two-dimensional crossed immunoelectrophoresis (16) using an in-house polyclonal sheep anti-human C3 antibody, X124 (diluted 1:100 in agarose-veronal buffer [pH 8.6]–10 mM EDTA). When C3 becomes activated, C3b and other breakdown products migrate faster in the agarose gel than C3, giving rise to the appearance of two rockets in the second dimension. The areas under the C3 and C3b rockets were measured, and the percentage of C3b was determined using the formula [b × (a + b)−1] × 100, where a is the area of the C3 rocket and b is the area of the C3b rocket.

C3 and C5.

Consumption of C3 or C5 in rat serum or mosquito samples was determined by Western blot analyses using a sheep anti-rat C3 polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:1,000 in PBS–5% skim milk; BioDesign, Saco, Maine) or a chicken anti-human C5 polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:1,000 in PBS–skim milk; AMS Biotechnology, Abindgdon, United Kingdom). Samples were run on sodium dodecyl sulfate–7.5% polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany), probed with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated donkey anti-sheep antibody (1:2,000; Sigma) or goat anti-chicken antibody (1:2,000; AMS Biotechnology), and then developed using nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate substrate (Zymed; Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, United Kingdom). The software NIH Image Analyzer was used to measure band intensities of C3 alpha chain and C5 alpha chain.

Exposure of parasites to rat complement in vitro.

As a complement source, normal rat serum (NRatS) was prepared as follows: freshly drawn blood was allowed to clot at room temperature in a glass container for 1 h and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g, and the serum was aliquoted and frozen at −70°C. As a control, this rat serum was heat inactivated by incubation at 56°C for 30 min.

P. berghei ANKA strain, clone 2.34, was used throughout this study. Gametocyte-infected blood was obtained from either Theiler's Original mice or male Wistar rats. Although mice are usually used as vertebrate hosts for P. berghei, rats are also suitable hosts for growth and transmission of this parasite (23). Ookinete cultures were prepared as described previously (31). If required, the cultures were depleted of red blood cells at approximately 1 h postgametogenesis (i.e., following fertilization), by either density centrifugations (12% Nycodenz) or dextran precipitation of red blood cells (1).

Samples from ookinete cultures were taken at 1, 4, 8, 11, and 22 h after the beginning of culture and centrifuged to remove the supernatant. Ten microliters of cell pellet was mixed with the same or twice the volume of NRatS or heat-inactivated rat serum (HIRatS) in triplicate in a 96 (U-shaped)-well plate, to give a final serum concentration of 50 or 67%, respectively. Controls receiving HIRatS were included for each sample and each time point. Following an incubation at 19°C for 2 h, 100 μl of RPMI medium was added to dilute the serum. The samples were washed once with medium, resuspended in 100 μl of medium, and returned to culture. Two experiments were carried out in which parasite samples were taken at earlier time points (0.5 and 1 h) and exposed to NRatS or HIRatS for only 1 h. At 24 h postinitiation of cultures, the number of viable ookinetes was determined, using Pbs21 as a marker. Pbs21 is a surface molecule expressed specifically by macrogametes, zygotes, and ookinetes of P. berghei (3). One microliter of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-Pbs21 monoclonal antibody (MAb) 12.1 (31) (diluted 1:300 in medium) and 3 μl of propidium iodide (50 μg/ml in PBS) were added to 100 μl of culture. Samples were mixed and incubated for approximately 15 min. Pbs21-positive ookinetes were counted in an Improved Neubauer chamber using a fluorescence microscope. The viability of the ookinetes was assessed by propidium iodide exclusion. The percent survival of ookinetes was calculated as follows: number of viable ookinetes in experimental culture × 100/number of viable ookinetes in control cultures.

In some experiments, a function-blocking antibody to the protective molecule CD59 was included to establish whether its presence would enhance the lysis of macrogametes and zygotes of P. berghei. In these cases, 10 μl of anti-rat CD59 MAb 6D1 (800 μg/ml) (12) or 10 μl of RPMI medium (negative control) was mixed with the cell pellet before the serum was added. From enriched cultures, 1 × 104 to 2 × 104 macrogametes and zygotes (10 μl) were used per well. Following serum incubation for 2 h, samples were washed with RPMI medium and the number of viable macrogametes and zygotes was determined as described above.

Indirect fluorescent-antibody test (IFAT).

Parasite samples taken at 1, 4, 8, 11, and 22 h were prepared as described above. After 0.5 h of incubation in NRatS or HIRatS, 100 μl of PBS–2% bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA) was added. Samples were briefly centrifuged, washed once more with PBS-BSA, resuspended in 100 μl of PBS-BSA, and incubated for 0.5 h with 1 μl of FITC-labeled anti-Pbs21 12.1 MAb (diluted 1:100 in PBS-BSA) to identify macrogametes, zygotes, and immature and mature ookinetes. After washing in PBS-BSA, cells were incubated for 0.5 to 1 h with either biotinylated mouse anti-rat C3 MAb ED11 (diluted 1:500 in PBS-BSA; Accurate Chemicals, Westbury, United Kingdom) or biotinylated mouse-anti-rat CD59 MAb 6D1 (diluted 1:50 to 1:100 in PBS-BSA) (12). Cells were washed twice with PBS-BSA, followed by 0.5 h of incubation in conjugate (streptavidin-Texas Red [Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.] or avidin-rhodamine [Sigma-Aldrich Co. Ltd., Dorset, United Kingdom]; 1:100 in PBS-BSA). After washing, cells were resuspended in 400 μl of PBS-BSA, fixed in 900 μl of PBS-BSA–1% paraformaldehyde, and kept at 4°C.

Alternatively, enriched parasites at 2 h postinitiation of the culture were incubated in NRatS or HIRatS for 5 min, washed with PBS-BSA, and incubated with biotinylated anti-rat C3 polyclonal antibody (diluted 1:500 in PBS-BSA; BioDesign) or biotinylated mouse anti-rat CD59 MAb (6D1; diluted 1:50 in PBS-BSA) for 0.5 h at room temperature. Following a brief wash, cells were incubated with a mixture of streptavidin-Texas Red conjugate and FITC-labeled anti-Pbs21 MAb 12.1 to identify zygotes. The CD59 labeling was amplified by a further 0.5-h incubation with a biotinylated antistreptavidin antibody (Vector Laboratories) followed by streptavidin-Texas Red conjugate. After a 0.5-h incubation, cells were washed and fixed in PBS-BSA–1% paraformaldehyde.

RESULTS

Complement levels in the mosquito midgut.

As a first step in the investigation, levels of components of the alternative pathway of complement in blood meals of mosquitoes fed on uninfected or infected male Wistar rats were determined. Rats were used instead of mice in these experiments because complement activity of mouse serum is weak and may be even more so under the conditions which are suitable for maintaining P. berghei mosquito midgut stages (19 to 21°C). In addition, rat complement components are more readily measured than mouse complement components.

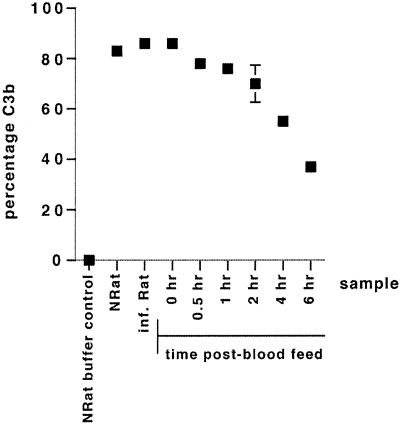

Survival of factors B and D in mosquito blood meals taken from rats was measured by their ability to generate a C3 convertase in association with CVF. The CVFBb convertase activity generated in midgut samples was measured by its ability to convert C3 into C3b and was compared to the level of CVFBb activity that could be generated in samples of NRatS and sera of P. berghei-infected rats. No conversion of C3 to C3b was observed in samples when CVF was omitted (NRatS buffer control) (Fig. 1). In samples containing NRatS, sera from malaria-infected rats (n = 2), and mosquito blood meals immediately postfeeding, more than 80% of the C3 was converted to C3b by the CVFBb convertase. In mosquito midgut samples taken at 0.5 and 1 h postfeeding, 79% (±2.5%) and 77% (±4.5%) of C3 conversion, respectively, were detected. Factor B and/or factor D activity began to decline in mosquito midguts from 2 h onwards. By 4 h, only 55% (±2.5%) of C3 was converted to C3b, while by 6 h, C3 conversion had declined to 40% (±5%) (Fig. 1). Similar results were obtained with samples of mosquitoes fed on noninfected rats (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Factor B and factor D activities in rat sera and samples of mosquitoes fed on P. berghei-infected rats were measured by their ability to generate a convertase with CVF and thereby convert human C3 into C3b. The amount of C3 conversion was measured by crossed immunoelectrophoresis, and the levels of C3b are expressed as a percentage of total C3. The mean percentage of C3b (± standard error of the mean) from two independent experiments is shown.

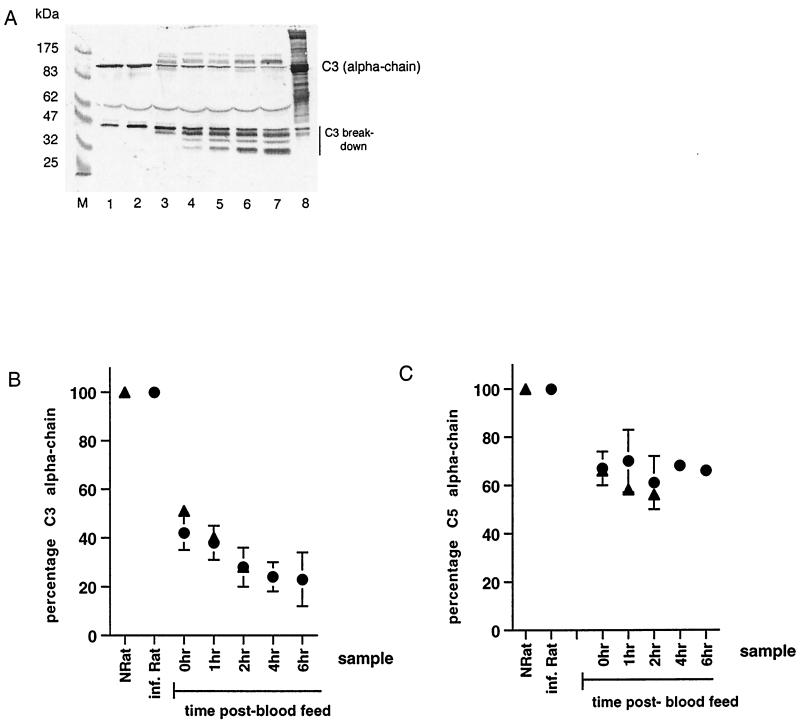

The fate of fluid-phase C3 in serum and mosquito midgut samples was analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 2A and B). In NRatS or serum from infected rats, the alpha chain of C3 was equally abundant (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2). A band of approximately 46 kDa, likely to represent the product of the first factor I cleavage of C3b, was visible in both samples, showing slightly stronger intensity in infected-rat serum. In samples of mosquitoes fed on infected rats taken immediately and 1 h postfeeding, the intensity of the C3 alpha-chain band decreased to approximately 40% (±7%) of that found in the serum of an infected rat (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4, and B), while the number and intensity of C3 breakdown product bands increased. This effect was more pronounced in midgut samples taken at later time points (2 to 6 h) (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 to 7, and B). The decline in intensity of the C3 alpha-chain band and the parallel increase of C3 breakdown bands suggest activation of C3 after blood ingestion by mosquitoes.

FIG. 2.

(A) Western blot analysis of C3 in rat serum and in mosquito midguts fed on P. berghei-infected rats, detected by sheep polyclonal anti-rat C3. The band representing the alpha chain of C3 is indicated. The band at 62 kDa is probably the beta chain of C3. Breakdown products of C3 run below 47 kDa. Lane M, molecular mass markers; lane 1, normal rat serum; lane 2, serum of a P. berghei-infected rat; lanes 3 to 7, mosquito midgut samples taken at 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h post-blood feed, respectively; lane 8, sample of partially purified human C3 which cross-reacts with the sheep polyclonal anti-rat C3 antibody. (B) Proportion of intact C3 in midguts of mosquitoes fed on P. berghei-infected (n = 2) or noninfected rats. The intensity of the C3 alpha-chain band in rat serum or mosquito midgut samples, visualized by Western blot analysis (panel A shows an example), was measured using NIH Image Analyzer software. The amount of C3 alpha chain (mean ± standard error of the mean) in midgut samples was expressed as a percentage of C3 alpha chain in sera of P. berghei-infected rats. ▴, normal rat; ●, P. berghei-infected rat. (C) Proportion of intact C5 in midguts of mosquitoes fed on P. berghei-infected (n = 2) or noninfected rats. The C5 alpha-chain band in rat serum or mosquito midgut samples was visualized by Western blot analysis (not shown) and measured using NIH Image Analyzer software. The amount of C5 alpha chain (mean ± standard error of the mean) in midgut samples was expressed as a percentage of C5 alpha chain in sera of P. berghei-infected rats. ▴, normal rat; ●, P. berghei-infected rat.

In all mosquito midgut samples, two bands with molecular masses of 111 and 100 kDa (just above and below the C3 alpha-chain band) resulted from cross-reaction of the sheep anti-rat C3 polyclonal antibody with mosquito molecules as demonstrated by Western blot analysis on midguts from sugar-fed mosquitoes (data not shown).

Less C5 conversion than C3 conversion occurred in midgut samples (Fig. 2C). In samples taken immediately after the 20-min feeding period (0 h), the intensity of the C5 alpha-chain band had decreased to 60 to 70% of that in the serum controls and remained at that level.

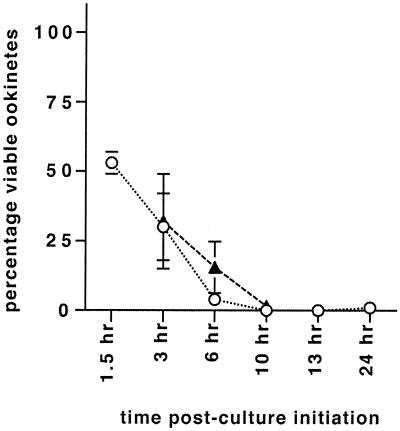

Complement sensitivity of parasites from fertilization to ookinete.

The sensitivity of macrogametes, zygotes, and developing ookinetes to the alternative pathway of complement was assessed by counting viable Pbs21-positive ookinetes in 24-h cultures after the parasites had been exposed to NRatS or HIRatS for 2 h at various time points during their development. The same serum sample was used throughout the course of one experiment to ensure that any observed differences in parasite survival were not due to variation in the levels of lytic activity between batches of sera. Dead parasites were easily recognized: they were reduced in size, Pbs21 labeling was not homogenous, and they were propidium iodide positive. In all samples exposed to NRatS, the number of viable ookinetes was reduced compared to that in samples exposed to HIRatS. When the parasites were derived from mice, 53% (±4%) of parasites were viable in samples exposed to complement from 0.5 to 1.5 h (n = 2) postgametogenesis. By 3 h, parasites in samples exposed to serum for 1 or 2 h (n = 2 and 7, respectively) were only 30% (±12%) viable. Parasites exposed later during in vitro development were increasingly affected by complement: in samples exposed from 4 to 6 h (n = 5) postgametogenesis or later, 4% (±2.8%) or fewer parasites survived exposure to NRatS (Fig. 3). The effect was similar whether parasites originated from mice or rats (Fig. 3). These results suggest that a proportion of P. berghei macrogametes and zygotes are protected against NRatS during the first 3 h of development, after which they become very sensitive to exposure to NRatS compared to HIRatS (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Resistance of P. berghei mosquito midgut stages to rat complement. Parasite survival is expressed as the mean percentage (± standard error of the mean) of live ookinetes in 24-h cultures after samples had been exposed to normal rat serum for 2 h at various time points during their development. All samples were tested in triplicate. Heat-inactivated controls were included for each time point and each sample, giving the reference point (100%) for expected parasite survival in the absence of complement. ○, ookinetes per mouse (mouse-derived parasites); ▴, ookinetes per rat (parasites derived from rats).

Molecules potentially involved in parasite protection.

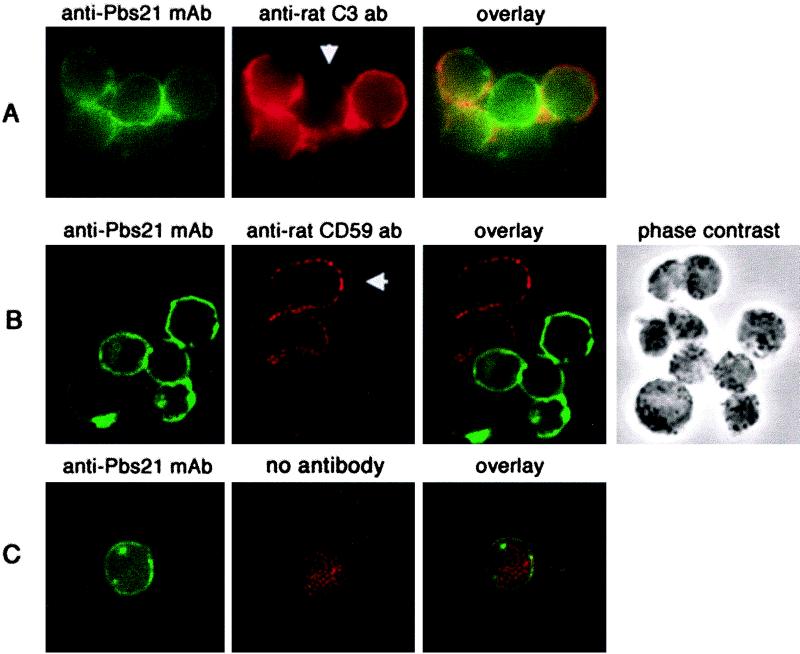

To analyze the molecular mechanisms of parasite protection against the alternative pathway of complement, we first examined whether or not C3 was deposited on macrogametes and zygotes. IFAT analyses revealed deposition of rat C3 on Pbs21-positive parasites taken at all time points, even those that showed protection against complement attack (Fig. 4A). For example, approximately 90% of zygotes showed considerable C3 deposition in IFATs (Fig. 4A), but 30 to 50% of them survived complement exposure during the first 3 h of zygote development (Fig. 3; Table 1). The observed resistance of parasites to rat complement may be due either to parasite molecules that are specifically expressed for this purpose or to acquisition of host complement control proteins. To establish whether or not emerging gametes acquire host molecules expressed on red blood cell membranes, such as DAF, a decay acceleration factor for C3 and C5 convertases (20), or CD59, a potent inhibitor of the membrane attack complex (MAC) (7), immunofluorescent-antibody staining was performed. Using anti-rat DAF MAbs (25) in this technique, no cell staining was observed on either host cells or parasites, although the same antibodies produced positive results in fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of rat red blood cells (data not shown). In IFATs using an anti-rat CD59 antibody, infected and noninfected rat red blood cells were CD59 positive, while parasites which were positive for Pbs21 were CD59 negative, suggesting that no host CD59 was taken up by emerging macrogametes (Fig. 4B). To further substantiate this result, the effect of adding 6D1 (a function-blocking antibody against CD59 [12]) upon lysis of the gametes and zygotes was tested. In experiments in which 6D1 MAb had been added to enriched macrogamete-zygote preparations, the presence of the antibody had no effect on parasite survival (Table 1), further suggesting that the parasites do not have CD59 on their surfaces. Collectively, these data suggest that host CD59 is not involved in protection of P. berghei mosquito midgut stages against complement-mediated attack.

FIG. 4.

Detection of C3 or CD59 on macrogamete and zygote surfaces in vitro. An FITC-labeled anti-Pbs21 antibody (green fluorescence) was used to visualize macrogametes and zygotes. (A) C3 deposition on macrogametes and zygotes following exposure to rat complement. Approximately 90% of Pbs21-positive parasites were positive for C3 deposition (red fluorescence). Note that the parasite in the middle shows hardly any C3 deposition (arrowhead). (B) While rat cells (white blood cells and infected or noninfected red blood cells [arrowhead]) stained positive for CD59 (red fluorescence), macrogametes and zygotes were almost completely negative for CD59. Occasionally, a few red dots were observed on parasite surfaces. (C) Negative control, with the first antibodies (anti-rat C3 or anti-rat CD59) omitted.

TABLE 1.

Survival of P. berghei macrogametes and zygotes exposed to NRatS in the presence or absence of anti-rat CD59 MAb 6D1a

| Prepn of enriched macrogametes and zygotes | MAb 6D1 | Mean no. of live Pbs21-positive cells/μl of culture (SEM) exposed to:

|

% of live macrogametes and zygotesb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRatS | HIRatS | |||

| Nycodenz | Absent | 25 (4) | 31 (2) | 80 |

| Present | 34 (10) | 45 (2) | 75 | |

| Dextran | Absent | 30 (5) | 62 (10) | 49 |

| Present | 46 (16) | 83 (13) | 54 | |

Parasites were separated from red blood cells by density centrifugation on Nycodenz or by dextran precipitation of red blood cells. Approximately 1 × 104 to 2 × 104 parasites were used per well and were exposed for 2 h to rat serum with or without MAb 6D1 (200 μg/ml) starting 1 to 2 h postgametogenesis; each experiment was done in triplicate.

HIRatS = 100% control.

DISCUSSION

Activation of the alternative pathway of complement requires the binding of C3i or C3b to factor B. C3 consists of two subunits, an alpha chain of approximately 115 kDa and a beta chain of approximately 65 kDa. Upon activation, a 10-kDa fragment (C3a) is removed from the alpha chain, leaving C3b. C3b that does not bind to an activator surface is rapidly degraded further into fragments of various molecular masses ranging from 27 to 75 kDa. C3b is itself a component of the alternative pathway C3 convertase, C3bBb. However, the alternative pathway is activated continuously at a low level due to hydrolysis of C3 to form C3i, which can substitute for C3b in this role. The other component of the convertase is Bb, which is generated when factor B binds to C3b (or C3i), and is cleaved by factor D. This releases a small fragment, Ba, and generates the enzymatically active complex C3bBb (or C3iBb). Amplification of this process occurs on foreign (activating) surfaces where C3b is protected from degradation by factors I and H. Binding of additional C3b to the C3bBb complex produces the C5 convertase, (C3b)2Bb, which cleaves C5 into C5a and C5b, which initiates formation of the MAC. C5b binds to C6 and C7, producing a complex which can associate with cell membranes; subsequent binding of C8 and C9 forms a pore in the membrane that results in lysis of the attacked cell (reviewed in reference 30).

Previous studies suggested that malaria parasites are protected against the alternative pathway of complement, at least in the early stages of development in the mosquito midgut (8, 9). To establish whether or not the alternative pathway of complement is active in the mosquito midgut, we investigated the activity and presence of its components (factor B, factor D, C3, and C5) in blood from A. stephensi midgut samples. Factor B and factor D activities could be measured in mosquito blood meals for up to 6 h postingestion, although by 4 h the activity had dropped to about 50% of its original level. The decline in intensity of the intact C3 alpha chain and appearance of C3 breakdown products as demonstrated in Western blot analyses are consistent with C3 activation during and after blood passage into the mosquito midgut, which includes the time of gametogenesis and zygote formation. Mosquito tissue, bacteria present in the mosquito midgut, and parasites ingested with the blood meal could all activate the complement cascade. C3b that was bound to cell surfaces following activation to generate C3 and C5 convertases would have escaped our measurement. However, the experiment was designed to evaluate the amount of intact C3 (that was still available for activation) in mosquito midguts, and therefore only the fluid phase of the midgut contents was included. It is unlikely that the breakdown of C3 is due to mosquito digestive enzymes, because little enzymatic activity has been measured in mosquito guts during the first 6 h (2, 19); rather, it suggests activation of C3. Although C5 levels in midgut samples were less affected than C3 levels, the intensity of the C5 alpha-chain band dropped to 60 to 70% of that found in rat serum, suggesting activation of C5. Our data indicate that the components necessary to form the C3 and C5 convertases of the alternative pathway of complement and to initiate MAC formation were present and active in mosquito blood meals for several hours after blood meal ingestion.

Consistent with these data are the findings that in culture (permissive for development of ookinetes) P. berghei macrogametes and zygotes were resistant to lysis by rat complement. However, between 4 and 6 h into their development, parasites became increasingly sensitive to rat complement. In P. berghei, retort forms (immature ookinetes of stages II and III [13]) are visible 5 to 6 h postinitiation of cultures, coinciding with the increased sensitivity of developing ookinetes to complement-mediated lysis but also, interestingly, with the decline in complement levels described above. In that respect, it is interesting that during the development of P. gallinaceum zygotes into ookinetes, macrogamete- and zygote-specific surface molecules are shed by the developing parasite while new surface proteins are being expressed (6).

Resistance of P. berghei mosquito midgut stages to the alternative pathway of complement is also consistent with previous results which showed that there was no difference in oocyst numbers in A. stephensi regardless whether mosquitoes had fed on P. berghei-infected C5-deficient DBA/2 mice or on complement-sufficient BALB/c mice (23). However, using a closely related rodent malaria parasite, Tsuboi et al. (27) reported that mouse complement reduced the infectivity of P. yoelii to mosquitoes. Much higher oocyst numbers were counted on midguts of mosquitoes fed on C5-deficient DBA/2 mice than on midguts of mosquitoes fed on complement-sufficient DBA/1 mice. Supplementation of C5-deficient mouse serum with serum from DBA/1 mice or purified human C5 reintroduced the reduction in parasite transmission. However, in 4-h samples of mosquito midguts, zygote numbers were similar in mosquitoes fed on complement-deficient and complement-sufficient mice, whereas numbers of retort forms and mature ookinetes were reduced in mosquitoes fed on complement-sufficient mice (27). These data suggest that (i) mouse complement is active in the midgut of A. stephensi mosquitoes and (ii) P. yoelii macrogametes and zygotes do in fact show protection against complement. If it were the macrogametes and zygotes that were sensitive to lysis by complement, one would expect to see fewer zygotes in the 4-h sample of mosquitoes fed on complement-sufficient mice than in mosquitoes fed on complement-deficient mice. One possible explanation for the apparent complement sensitivity of P. yoelii may lie in the speed of development of P. yoelii in mosquito vectors (27, 28). In A. stephensi mosquitoes, immature and even mature ookinetes of P. yoelii were found after 4 h (27), implying that zygotes started to transform into retort forms earlier than that, when we have shown that complement is still active in the mosquito midgut. It is possible that the reported reduction of P. yoelii in the mosquito midgut (27) reflects the sensitivity of the transforming zygotes to complement. P. berghei develops much more slowly in the mosquito, perhaps as a result of lower temperature requirements (20°C for P. berghei versus 25°C for P. yoelii). P. berghei ookinetes are found from 12 h after blood meal ingestion, peaking at 18 to 20 h (29), whereas ookinete numbers of P. yoelii in A. stephensi peak at around 8 h (28). As mentioned above, in P. berghei the transition of zygotes into retort forms in vitro starts at around 5 to 6 h postgametogenesis (references 13 and 24 and our unpublished observations) and coincides with an increased sensitivity to complement-mediated lysis of P. berghei.

Grotendorst et al. demonstrated a loss of complement resistance following trypsinization of zygotes, suggesting that the protective entity is a surface protein(s) (9). Those authors further demonstrated that this molecule(s) functioned in a species-restricted fashion (9), a description which could be applicable either to parasite proteins specifically expressed for the purpose or to host complement control molecules acquired by the parasite. Complement control proteins expressed by red blood cells include CD59, a potent inhibitor of the MAC (7), and DAF, which accelerates the decay of C3 and C5 convertases (20), glucosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored molecules which may insert into lipid bilayers and transfer between cells (15). Both of these molecules have been shown to possess species specificity to various degrees according to the particular species involved (10, 21). While CD59 is abundantly expressed on rat erythrocyte membranes, DAF is expressed at much lower levels (25), which may be the reason that we were unable to detect a signal in IFATs. It was conceivable that P. berghei gametes could take up host complement control proteins like CD59 while emerging from the red blood cell envelope, but the experimental data show that this is not the case. These data suggest that either no host CD59 was taken up by emerging macrogametes or, if it was taken up initially, then after 2 h of development (when these parasite stages still showed resistance against complement lysis) it had almost completely disappeared from the surface of zygotes. Further studies to elucidate the molecular mechanism of complement evasion by early mosquito midgut stages of P. berghei parasites are under way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by SmithKline Beecham. A.D. is a Royal Society University Research Fellow.

We are grateful to Rodney Oldroyd for his useful advice on the crossed immunoelectrophoresis technique and to Paul Morgan for provision of GD1 antibody.

REFERENCES

- 1.Augustin R. Techniques for the study and assay of reagins in allergic subjects. In: Weir D M, editor. Handbook of experimental immunology. 3rd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1978. pp. 45.44–45.45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billingsley P F, Hecker H. Blood digestion in the mosquito, Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae): activity and distribution of trypsin, aminopeptidase, and alpha-glucosidase in the midgut. J Med Entomol. 1991;28:865–871. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/28.6.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco A R, Paez A, Gerold P, Dearsly A L, Margos G, Schwarz R T, Barker G, Rodriguez M C, Sinden R E. The biosynthesis and post-translational modification of Pbs21, an ookinete-surface protein of Plasmodium berghei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;98:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butcher G A, Sinden R E, Billker O. Plasmodium berghei: infectivity of mice to Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. Exp Parasitol. 1996;84:371–379. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter R, Gwadz R W, Green I. Plasmodium gallinaceum: transmission-blocking immunity in chickens. II. The effect of antigamete antibodies in vitro and in vivo and their elaboration during infection. Exp Parasitol. 1979;47:194–208. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(79)90073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter R, Kaushal D C. Characterization of antigens on mosquito midgut stages of Plasmodium gallinaceum. III. Changes in zygote surface proteins during transformation to mature ookinete. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1984;13:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(84)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies A, Simmons D L, Hale G, Harrison R A, Tighe H, Lachmann P J, Waldmann H. CD59, an LY-6-like protein expressed in human lymphoid cells, regulates the action of the complement membrane attack complex on homologous cells. J Exp Med. 1989;170:637–654. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grotendorst C A, Carter R. Complement effects of the infectivity of Plasmodium gallinaceum to Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. II. Changes in sensitivity to complement-like factors during zygote development. J Parasitol. 1987;73:980–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grotendorst C A, Carter R, Rosenberg R, Koontz L C. Complement effects on the infectivity of Plasmodium gallinaceum to Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. I. Resistance of zygotes to the alternative pathway of complement. J Immunol. 1986;136:4270–4274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris C L, Spiller O B, Morgan B P. Human and rodent decay-accelerating factors (CD55) are not species restricted in their complement-inhibiting activities. Immunology. 2000;100:462–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison R A. Purification, assay, characterization of complement proteins from plasma. In: Herzenberg L A, Weir D M, Blackwell C, editors. Weir's handbook of experimental immunology. 5th ed. II. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Science; 1996. pp. 75.1–75.50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes T R, Piddlesden S J, Williams J D, Harrison R A, Morgan B P. Isolation and characterization of a membrane protein from rat erythrocytes which inhibits lysis by the membrane attack complex of rat complement. Biochem J. 1992;284:169–176. doi: 10.1042/bj2840169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janse C J, Mons B, Rouwenhorst R J, Van der Klooster P F, Overdulve J P, Van der Kaay H J. In vitro formation of ookinetes and functional maturity of Plasmodium berghei gametocytes. Parasitology. 1985;91:19–29. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000056481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jokiranta T S, Jokipii L, Meri S. Complement resistance of parasites. Scand J Immunol. 1995;42:9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kooyman D L, Byrne G W, Logan J S. Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol anchor. Exp Nephrol. 1998;6:148–151. doi: 10.1159/000020516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laurell C B. Quantitative estimation of proteins by electrophoresis in agarose gel containing antibodies. Anal Biochem. 1966;15:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(66)90246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leid R W. Parasites and complement. Adv Parasitol. 1988;27:131–168. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60354-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lensen A H W, Bolmer-van de Vegte M, van Gemert G J, Eling W M C, Sauerwein R W. Leukocytes in a Plasmodium falciparum-infected blood meal reduce transmission of malaria to Anopheles mosquitoes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3834–3837. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3834-3837.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller H M, Catteruccia F, Vizioli J, della Torre A, Crisanti A. Constitutive and blood meal-induced trypsin genes in Anopheles gambiae. Exp Parasitol. 1995;81:371–385. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholson-Weller A, Burge J, Fearon D T, Weller P F, Austen K F. Isolation of a human erythrocyte membrane glycoprotein with decay-accelerating activity for C3 convertases of the complement system. J Immunol. 1982;129:184–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rollins S A, Zhao J, Ninomiya H, Sims P J. Inhibition of homologous complement by CD59 is mediated by a species-selective recognition conferred through binding to C8 within C5b-8 or C9 within C5b-9. J Immunol. 1991;146:2345–2351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinden R E. Infection of mosquitoes with rodent malaria. In: Crampton J M, Beard C B, Louis C, editors. Molecular biology of insect disease vectors: a method manual. London, United Kingdom: Chapman and Hall; 1997. pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinden R E, Butcher G A, Billker O, Fleck S L. Regulation of infectivity of Plasmodium to the mosquito vector. Adv Parasitol. 1996;38:53–117. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinden R E, Hartley R H, Winger L. The development of Plasmodium ookinetes in vitro: an ultrastructural study including a description of meiotic division. Parasitology. 1985;91:227–244. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000057334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiller O B, Hanna S M, Morgan B P. Tissue distribution of the rat analogue of decay-accelerating factor. Immunology. 1999;97:374–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tirawanchai N, Winger L A, Nicholas J, Sinden R E. Analysis of immunity induced by the affinity-purified 21-kilodalton zygote-ookinete surface antigen of Plasmodium berghei. Infect Immun. 1991;59:36–44. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.36-44.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuboi T, Cao Y M, Torii M, Hitsumoto Y, Kanbara H. Murine complement reduces infectivity of Plasmodium yoelii to mosquitoes. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3702–3704. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3702-3704.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaughan J A, Hensley L, Beier J C. Sporogonic development of Plasmodium yoelii in five anopheline species. J Parasitol. 1994;80:674–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaughan J A, Narum D, Azad A F. Plasmodium berghei ookinete densities in three anopheline species. J Parasitol. 1991;77:758–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walport M J, Lachmann P J. Complement. In: Lachmann P J, Peters D K, Rosen F S, Walport M J, editors. Clinical aspects of immunology. 5th ed. Vol. 1. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1993. pp. 1287–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winger L A, Tirawanchai N, Nicholas J, Carter H E, Smith J E, Sinden R E. Ookinete antigens of Plasmodium berghei. Appearance on the zygote surface of an Mr 21 kD determinant identified by transmission-blocking monoclonal antibodies. Parasite Immunol. 1988;10:193–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1988.tb00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]