Psychological and Cognitive Sciences Correction for “Empirical audit and review and an assessment of evidentiary value in research on the psychological consequences of scarcity,” by Michael O’Donnell, Amelia S. Dev, Stephen Antonoplis, Stephen M. Baum, Arianna H. Benedetti, N. Derek Brown, Belinda Carrillo, Andrew L. Choi, Paul Connor, Kristin Donnelly, Monica E. Ellwood-Lowe, Ruthe Foushee, Rachel Jansen, Shoshana N. Jarvis, Ryan Lundell-Creagh, Joseph M. Ocampo, Gold N. Okafor, Zahra Rahmani Azad, Michael Rosenblum, Derek Schatz, Daniel H. Stein, Yilu Wang, Don A. Moore, and Leif D. Nelson, which was published October 28, 2021; 10.1073/pnas.2103313118 (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2103313118).

The authors note, “We thank Philip Fernbach, Christina Kan, and John Lynch for alerting us to discrepancies between the materials we used in our replication attempt of their study and their original materials (1). Due to these discrepancies, we have removed the reporting of the results of our initial replication attempt of this study from the corrected Brief Report. We have conducted an additional replication attempt of this study, the results and method of which are available at https://osf.io/ezw6p/ (2).

Separately, Anuj Shah, Jiaying Zhao, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Eldar Shafir noted some data analytic errors in some of our replication attempts of their work (3). We note these analytic errors here and have corrected them.

Shah et al. (2018), Study 3 (4): In our initial analysis, we did not include participants who submitted 0 clicks on the primary dependent variable in the data for our analysis. We preregistered that we would exclude ‘those without click-data’ (i.e., 0 clicks) on the basis that Shah et al indicated in their original paper that ‘Click-data were missing from 5 participants…’ (Shah et al., 2018, p. 11). However, in their comment on our article, Shah et al. indicated that ‘0’ clicks should be considered valid responses, so we have redone the analysis, including these responses. Moreover, Shah et al. correctly pointed out that we did not drop outliers on the income measure. Upon inspection of the data, we found 24 respondents who indicated that their recalculated income was greater than or equal to 3 standard deviations below the mean and should have been excluded from the analysis. Our initial analysis generated an effect size estimate of r = 0.027, 95% CI [−0.026, 0.081] and our corrected analysis generated an effect size estimate of r = 0.033, 95% CI [−0.019, 0.085]. Shah et al. also noted that in our initially posted SI, we included a link to an analysis in our project archive that was based on scrambled data. Although we did not use this analysis in our Brief Report, nor did we base any of our reported results on this scrambled data file, because we included a link to it in our SI, we note the error here.

Shah et al. (2015), Study 6 (5): In our initial analysis, we failed to remove duplicate data points from two participants in our dataset. We dropped the second duplicate response from both of these participants (2 responses total) and repeated our initial data analysis. Our initial analysis generated an effect size estimate of r = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.046, 0.223], and our corrected analysis generated an effect size estimate of r = 0.09, 95% CI [−0.047, 0.224].

Finally, we described the 20 effects we attempted to replicate in our Brief Report as each being significant in the original; however, two of these effects were originally published null results (6, 7). Thus, 18 of the effects we attempted to replicate were significant when they were originally published.

The details for these corrections are all archived here: https://osf.io/6uh2s/ (8).”

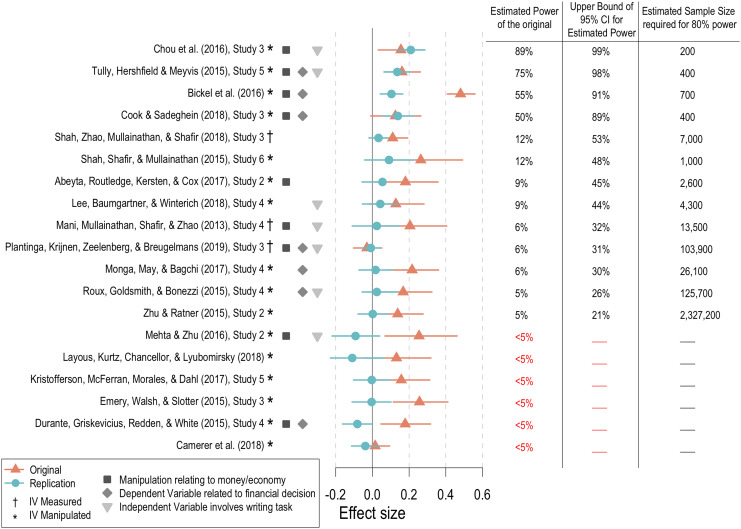

The corrected Fig. 1 and its legend appear below. The SI Appendix 01 has been updated, and the article text has been updated throughout to reflect the corrections described above.

Fig. 1.

The Leftmost columns indicate common features among the replicated studies, and the Middle column depicts effect size (correlation coefficients) for the original and replication studies. Effect sizes are bounded by 95% CIs. The Right columns indicate the estimated power in the original studies (third column from the Right), the upper bound of the 95% CI for estimated power in the original (second column from the Right), and an estimated sample size required for 80% power, based on the replication effect (Rightmost column).

Additionally, a reference was omitted from the article. The complete reference appears below. The online version has been corrected.

19. M. O’Donnell et al., Empirical audit and review and an assessment of evidentiary value in research on the psychological consequences of scarcity. Open Sci. Framework, 10.17605/OSF.IO/A2E96 (2022).

1. P. M. Fernbach, C. Kan, J. G. Lynch Jr., Squeezed: Coping with constraint through efficiency and prioritization. J. Consum. Res. 41, 1204–1227 (2015).

2. D. Schatz et al., Fernbach, Kan, & Lynch, 2015 - Study 2 replication (Schatz). Open Sci. Framework, 10.17605/OSF.IO/EZW6P (2022).

3. A. K. Shah, J. Zhao, S. Mullainathan, S. Shafir, A scarcity literature mischaracterized with an empirical audit. PsyArXiv. April 6, 2022. 10.31234/osf.io/gphcz (2022).

4. A. K. Shah, J. Zhao, S. Mullainathan, E. Shafir, Money in the mental lives of the poor. Soc. Cogn. 36, 4–19 (2018).

5. A. K. Shah, E. Shafir, S. Mullainathan, Scarcity frames value. Psychol. Sci. 26, 402–412 (2015).

6. C. F. Camerer et al., Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 637–644 (2018).

7. A. Plantinga, J. M. Krijnen, M. Zeelenberg, S. M. Breugelmans, Evidence for opportunity cost neglect in the poor. J. Behav. Dec. Making 31, 65–73 (2018).

8. M. O’Donnell et al., Additional materials. Open Sci. Framework, 10.17605/OSF.IO/6UH2S (2022).