Abstract

Since interleukin-6 (IL-6) may promote Th2 responses, we infected BALB IL-6-deficient (IL-6−/−) mice with Leishmania major. There was not a significant difference between the courses of infection (lesion size and parasite burden) in IL-6−/− and wild-type mice, but IL-6−/− mice expressed lower levels of Th2- and Th1-associated cytokines.

Perhaps the best-studied example of a disease in which Th1 and Th2 cells dictate the outcome of the infection is cutaneous leishmaniasis induced by Leishmania major. Mice that develop a Th1 response to infection with L. major (e.g., C57BL/6 mice) recover from their infections, whereas mice that develop a Th2 response (e.g., BALB/c mice) succumb to infection (reviewed in references 3, 10, 16, and 18). Among the many regulators of Th development, it has been suggested that interleukin-6 (IL-6) favors the outgrowth of Th2 cells (19). Several cell types, including macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells, produce IL-6. Originally thought of as a B-cell growth factor, IL-6 is now known to have effects on several components of the immune system (1, 24).

Work by Moskowitz et al. (15) showed that C57BL/6 IL-6−/− and wild-type C57BL/6 mice recovered from infections with L. major with the same kinetics. However, since C57BL/6 mice do not develop a Th2 response when infected with L. major, these experiments did not address the question of whether IL-6 is involved in Th2 development against infection with L. major. To address this question, it is necessary to investigate the role of IL-6 in the development of an anti-L. major Th2 response in susceptible BALB mice.

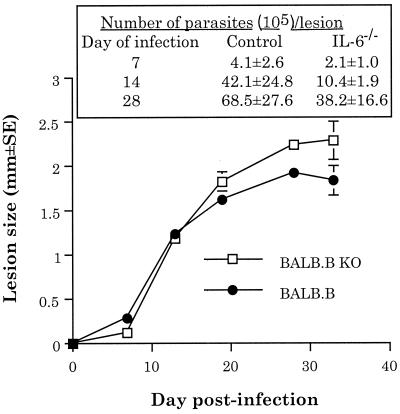

The course of infection with L. major in IL-6−/− BALB.B mice does not significantly differ from the course of infection in susceptible wild-type BALB.B mice.

In pilot experiments, we determined whether the amounts of IL-6 produced by susceptible and resistant mice differed. We utilized an in vitro priming system, which we have previously reported mimics the in vivo response to L. major (23). In this system, we found that cells from susceptible mice produced between two- and fourfold more IL-6 than cells from resistant mice.

Because this result suggested that IL-6 secretion correlates with susceptibility to infection with L. major, we hypothesized that IL-6−/− BALB.B mice (6) (BALB.B/AiTac-[KO]IL-6 N9; Taconic Farms, Germantown, N.Y.) would be more resistant to infection with L. major than susceptible wild-type BALB.B mice (C.B10-H2b/LilMcdJ [BALB.B10]; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine). BALB.B mice (as well as other BALB congenics, such as BALB.K) are as susceptible to infection with L. major as BALB/c mice are; all of the mice die from infection at the same time postinfection (4). Groups of five mice each were infected subcutaneously with 2 × 106 L. major promastigotes (LV39) in one hind footpad. The lesion progression and parasite burden were monitored as described elsewhere (11, 23). Contrary to our hypothesis, the lesion size (Fig. 1) in IL-6−/− BALB.B mice was not significantly different from that seen in wild-type susceptible BALB.B mice (three-way analysis of variance followed by all pairwise multiple-comparison posthoc t tests [Student-Newman-Keuls method]; differences were considered significant at a P of <0.05). However, the lesion size did not fully reflect the extent of pathology in these experiments. In the three replicate experiments performed, the pathology associated with infection in the IL-6−/− mice was consistently more severe than that in control BALB.B mice. That is, lesions on IL-6−/− mice ulcerated and became necrotic more rapidly (5 to 7 days earlier) than those on control BALB.B mice.

FIG. 1.

The course of infection with L. major in susceptible BALB.B mice does not significantly differ from the course of infection in IL-6−/− BALB.B mice. The results shown are averages of three independent experiments ± standard errors of the mean. KO, knockout.

To attempt to confirm the results shown in Fig. 1, and because lesion pathology and parasite burden within lesions do not always correlate (11), we also determined the numbers of parasites in the lesions of infected BALB.B and IL-6−/− BALB.B mice by using published techniques (11). IL-6−/− BALB.B mice had somewhat fewer parasites within their lesions at all times tested; however, these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 1). Taken as a whole, the data showed small differences (both positive and negative) between the susceptibilities of IL-6−/− mice and control BALB.B mice to infection with L. major. However, none of these differences was statistically significant.

IL-6 deficiency down regulates the expression of both Th1- and Th2-associated cytokines in BALB.B mice infected with L. major.

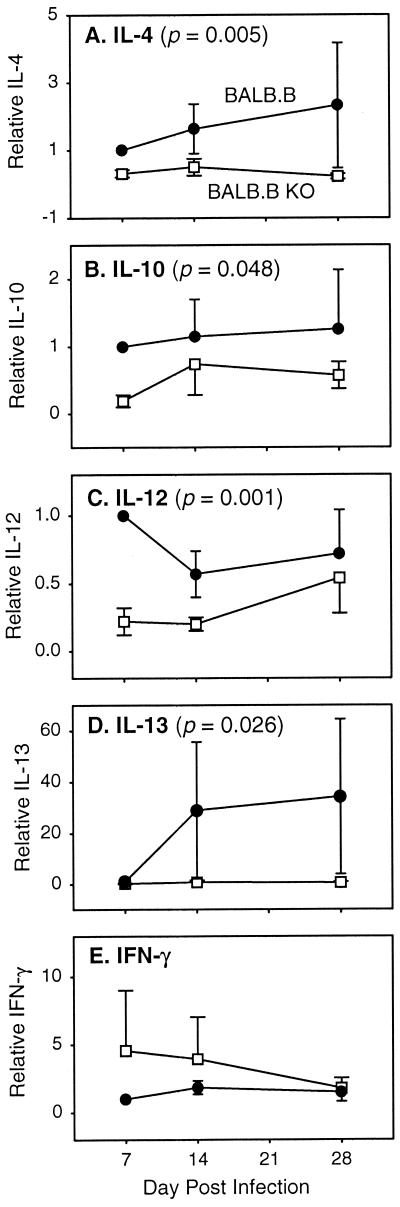

In an effort to explain the mechanism underlying the lack of effect of IL-6 on susceptibility to infection with L. major, we measured the expression of mRNA for five different cytokines involved in the immune response to the parasite. We measured IL-4 and IL-13 mRNA levels, since these cytokines drive Th2 responses (3, 10, 12, 18). We measured IL-12 and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) mRNA levels, since these factors are critical for the development of a Th1 response and the subsequent destruction of L. major (3, 10, 18). Finally, we also measured levels of IL-10 mRNA expression, since IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ cross regulate each other's expression (3, 10, 14, 18, 23).

Two mice per experimental group were killed, and lesion-draining popliteal and inguinal lymph nodes were removed and processed using published techniques (13). There was no difference in lymph node size between groups (data not shown). Competitors and primers for mouse β-actin, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and IFN-γ were generated according to published procedures (13, 17). A competitor for mouse IL-13 was constructed in our laboratory by PCR using primers (CGCTGGCGGGTTCTGTGTACTGGATGGAGGCGGATAAAGTTG and GCCTCTC CCCAGCAAAGTCTCTACGATACGGGAGGGCTTACC AT) and the pCRII-TOPO plasmid (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.) as the template DNA. IL-13 primers (CGCTGGCGGGTTCTGTGTA and GCCTCTCCCCAGCAAAGTCT) and all other primers (13, 17) were purchased from Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, Md.).

Fluorescent-band intensities were determined as peak heights for each lane of agarose gels using the 1D-Multi function of AlphaEase image analysis software, version 5 (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, Calif.). The ratio of peak heights for competitor and cDNA bands was plotted against the number of competitor molecules added per reaction on a log-log scale, and the coefficients of a least-squares regression line were calculated using SigmaPlot graphical software version 5 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.). The number of specific cDNA molecules per reaction equals antilog (−intercept/slope).

First, it should be mentioned that baseline and spontaneous production of all cytokines measured did not differ (P > 0.05) between uninfected control BALB.B and IL-6−/− BALB.B mice except for IFN-γ. Baseline expression of IFN-γ in IL-6−/− BALB.B mice was 69% of that seen in BALB.B mice (P = 0.047). Therefore, for IFN-γ mRNA expression, the results are normalized to the average uninfected IFN-γ levels for each mouse strain.

In Fig. 2, the data from three replicate experiments have been normalized and are presented as the fold difference of the IL-6−/− group compared to the control. This approach allowed for a statistical analysis of all experiments, and P values are presented in the figure. IL-6 deficiency led to depressed expression of all mRNAs analyzed except that of IFN-γ.

FIG. 2.

Expression of cytokine mRNA in lesion-draining lymph nodes. mRNA levels are shown for wild-type (●) and IL-6−/− (□) mice relative to wild-type mice on day 7. The data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean for three independent experiments. Values of P are shown for the treatment factor (wild-type versus IL-6 deficient) from a three-way analysis of variance in which the three factors were treatment, day, and experimental trial.

Finally, it should be noted that we also measured IL-6 mRNA expression levels in IL-6−/− and control BALB.B mice and that IL-6 mRNA could not be detected in BALB.B IL-6−/− mice.

Our results agree with those of Moskowitz et al. (15), who showed that IL-6 had little effect in resistant C57BL/6 mice infected with L. major. They also agree with those of Saha et al. (20), who showed that treatment with an anti-IL-6 antibody was therapeutic for susceptible BALB/c mice infected with L. major; however, as was the case in this study using IL-6-deficient mice (Fig. 1), it did not cause the animals to recover from their infections. Therefore, IL-6 can be involved in the development of a Th2 response in susceptible BALB/c mice infected with L. major; however, IL-6 is not required for the development of that response. Alternatively, since it has been suggested that the Th2 response seen in BALB/c mice infected with L. major results from cross-reactivity with an environmental antigen(s) (5), the results presented here may suggest that IL-6 is not required for the maintenance of a Th2 response to L. major.

It is interesting that in BALB.B IL-6−/− mice infected with L. major, the levels of expression of mRNA for both Th1- and Th2-associated cytokines (except IFN-γ) were reduced (Fig. 2). This pattern of cytokine response is not unique. For example, IL-6−/− mice have been reported to produce lower levels of IL-4 but unchanged levels of IFN-γ in other experimental settings (2, 25). The results presented here are also in partial agreement with those of Saha et al. (20), who showed that treating BALB/c mice with an anti-IL-6 antibody lowered production of IL-4 (as was the case here [Fig. 2]) but increased production of IFN-γ (while IFN-γ mRNA expression was unchanged or slightly elevated here [Fig. 2]). This discrepancy may be due to the different systems analyzed. Therefore, in the BALB.B IL-6−/− mouse system examined here, IL-6 deficiency appeared to generally lower the set point for the expression of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines but not their overall balance of expression. As a result, BALB.B IL-6−/− mice remained susceptible to infection with L. major.

Others have also reported that IL-6 can affect the development of both type 1 and type 2 immune responses. The literature regarding the effect of IL-6 on the development of immune responses is large; however, representative examples of the diverse effects of IL-6 include the following: (i) IL-6 is required for the development of a Th1 response (26), (ii) IL-6 is required for the development of a Th2 response (19), and (iii) IL-6 is required for the development of both a Th1 and Th2 response (21).

Although IL-6 is not required for the development of either a Th1 or a Th2 response in mice infected with L. major, it can affect the immune responses to other pathogens, albeit variably. IL-6 is not required for the development of a Th2 response in mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni, but it has an important regulatory role (8, 9). In one study, IL-6 appeared to be critical for the development of resistance of mice to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (an infection in which a type 1 response leads to resistance [7]), but in another study IL-6 was not essential for the development of immunity to M. tuberculosis (22). Finally, IL-6 can also compromise the ability of mice to resist viral infection (6).

In summary, IL-6 deficiency reduces the expression of both Th1- and Th2-associated cytokines in BALB mice infected with L. major, but it does not alter the susceptible phenotype of the mice. Indeed, taking the results presented here in conjunction with the results of others, it appears that the effect that IL-6 may have on the development of either a Th1 or Th2 response cannot be predicted. Rather, each experimental system must be examined on a case-by-case basis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AI-29955.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira S, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6 in biology and medicine. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:1–78. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anguita J, Rincon M, Samanta S, Barthold S W, Flavell R A, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi-infected, interleukin-6-deficient mice have decreased Th2 responses and increased Lyme arthritis. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1512–1515. doi: 10.1086/314448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogdan C, Rollinghoff M. The immune response to Leishmania: mechanisms of parasite control and evasion. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:121–134. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howard J G, Hale C, Chan-Liew W L. Immunological regulation of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. 1. Immunogenetic aspects of susceptibility to Leishmania tropica in mice. Parasite Immunol. 1980;2:303–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1980.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Julia V, McSorley S S, Malherbe L, Breittmayer J-P, Girard-Pipau F, Beck A, Glaichenhaus N. Priming by microbial antigens from the intestinal flora determines the ability of CD4+ T cells to rapidly secrete IL-4 in BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania major. J Immunol. 2000;165:5637–5645. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, Fruedenberg M, Lamers M, Kishimoto T, Zinkernagel R, Bluethmann H, Kohler G. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;368:339–342. doi: 10.1038/368339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladel C H, Blum C, Dreher A, Reifenberg K, Kopf M, Kaufmann S H E. Lethal tuberculosis in interleukin-6-deficient mutant mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4843–4849. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4843-4849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Flamme A C, MacDonald A S, Pearce E J. Role of IL-6 in directing the initial immune response to schistosome eggs. J Immunol. 2000;164:2419–2426. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.La Flamme A C, Pearce E J. The absence of IL-6 does not affect Th2 cell development in vivo, but does lead to impaired proliferative, IL-2 receptor expression, and B cell responses. J Immunol. 1999;162:5829–5837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Launois P, Tacchini-Cottier F, Parra-Lopez C, Louis J A. Cytokines in parasitic diseases: the example of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;17:157–180. doi: 10.3109/08830189809084491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lima H C, Bleyenberg J, Titus R G. A simple method for quantifying Leishmania in tissues of infected animals. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:80–82. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(96)40010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthews D J, Emson C L, McKenzie G L, Jolin H E, Blackwell J M, McKenzie A N. IL-13 is a susceptibility factor for Leishmania major infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:1458–1462. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mbow M L, Bleyenberg J A, Hall L R, Titus R G. Phlebotomus papatasi sand fly salivary gland lysate downregulates a Th1, but upregulates a Th2, response in mice infected with Leishmania major. J Immunol. 1998;161:5571–5577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris S C, Madden K B, Adamovicz J J, Gause W C, Hubbard B R, Gately M K, Finkelman F D. Effects of IL-12 on in vivo cytokine gene expression and Ig isotype selection. J Immunol. 1994;152:1047–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moskowitz N H, Brown D R, Reiner S L. Efficient immunity against Leishmania major in the absence of interleukin-6. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2448–2450. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2448-2450.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. Th1 and Th2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Platzer C, Richter G, Überla K, Müller W, Blöcker H, Diamantstein T, Blankenstein T. Analysis of cytokine mRNA levels in interleukin-4-transgenic mice by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1179–1184. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiner S L, Locksley R M. The regulation of immunity to Leishmania major. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:151–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rincon M, Anguita J, Nakamura T, Fikrig E, Flavell R A. Interleukin (IL)-6 directs the differentiation of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:461–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saha B, Saini A, Germond R, Perrin P J, Harlan D M, Davis T A. Susceptibility or resistance to Leishmania infection is dictated by the macrophages evolved under the influence of IL-3 or GM-CSF. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2319–2329. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199907)29:07<2319::AID-IMMU2319>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samoilova E B, Horton J L, Hilliard B, Liu T S, Chen Y. IL-6-deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: roles of IL-6 in the activation and differentiation of autoreactive T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:6480–6486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders B M, Frank A A, Orme I M, Cooper A M. Interleukin-6 induces early gamma interferon production in the infected lung but is not required for generation of specific immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3322–3326. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3322-3326.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soares M B P, David J R, Titus R G. An in vitro model for infection with Leishmania major that mimics the immune response in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2837–2845. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2837-2845.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taga T, Kishimoto T. GP130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:797–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Homer R J, Chen Q, Elias J A. Endogenous and exogenous IL-6 inhibit aeroallergen-induced Th2 inflammation. J Immunol. 2000;165:4051–4061. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto M, Yoshikazi K, Kishimoto T, Ito H. IL-6 is required for the development of Th1 cell-mediated murine colitis. J Immunol. 2000;164:4878–4882. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]