Abstract

For over a century, polyclonal antibodies have been used to treat snakebite envenoming and are still considered by the WHO as the only scientifically validated treatment for snakebites. Nevertheless, moderate innovations have been introduced to this immunotherapy. New strategies and approaches to understanding how antibodies recognize and neutralize snake toxins represent a challenge for next-generation antivenoms. The neurotoxic activity of Micrurus venom is mainly due to two distinct protein families, three-finger toxins (3FTx) and phospholipases A2 (PLA2). Structural conservation among protein family members may represent an opportunity to generate neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against family-conserved epitopes. In this work, we sought to produce a set of monoclonal antibodies against the most toxic components of M. altirostris venom. To this end, the crude venom was fractionated, and its major toxic proteins were identified and used to generate a panel of five mAbs. The specificity of these mAbs was characterized by ELISA and antivenomics approaches. Two of the generated mAbs recognized PLA2 epitopes. They inhibited PLA2 catalytic activity and showed paraspecific neutralization against the myotoxicity from the lethal effect of Micrurus and Naja venoms’ PLA2s. Epitope conservation among venom PLA2 molecules suggests the possibility of generating pan-PLA2 neutralizing antibodies.

Keywords: phospholipase A2, monoclonal antibody, neutralization PLA2 activity, enzymatic activity, myotoxicity

1. Introduction

Coral snakes are a large monophyletic group of over 80 small- to medium-sized colorful species of the Elapid family. Notable for their colorful red, yellow/white, and black colored banding, basal coral snake lineages originated in Asia [1,2] and are currently represented by two genera in the Old World (Calliophis and Sinomicrurus) and by three (Leptomicrurus, Micruroides, and Micrurus) in the New World [1,3,4]. However, separating Micrurus from Leptomicrurus is not a scientific consensus [3,5]. Extant New World coral snakes are widely distributed in the southern range of many temperate U.S. states, throughout Central America, and most of South America to central Argentina [6].

Envenomation by New World coral snakes is characterized by local manifestations, including myonecrosis [7,8], cardiovascular effects [9], and predominantly systemic neurotoxicity leading to respiratory arrest and death in severe cases [10,11,12]. A number of micrurine species have their venoms analyzed by venomic and transcriptomic approaches, including those from M. surinamensis [13,14]; M. corallinus [14,15,16]; M. altirostris [16]; M. nigrocinctus [17]; M. mipartitus [18]; M. frontalis, M. ibiboboca, M. lemniscatus, and M. spixii, [14,19,20,21]; M. tener tener [22]; M. laticollaris [23]; M. fulvius [24,25]; M. mosquitensis and M. alleni [26]; M. dumerilii [27]; M. tschudii [28]; M. clarki [29]; M. pyrrhocryptus [30]; M. ruatanus [31]; M. browni browni [32]; and more recently M. yatesi [33]. These studies have revealed that post-synaptic α-neurotoxins of the three-finger toxins (3FTx) family [34] and pre-synaptic phospholipase A2 (PLA2) molecules [35,36,37] represent the main toxin classes of Micrurus venoms. However, the relative abundance of these toxins varies widely between species [38]. Venomics combined with protein biochemical characterizations has contributed to a deeper understanding of the molecular determinants of the clinical effects of coral snake envenomation [22,23,32,39,40].

The Brazilian commercial Elapidic antivenom is produced at Butantan Institute (São Paulo) and Ezequiel Dias Foundation (Minas Gerais) by hyper-immunization of horses with equal amounts of venom from M. corallinus and M. frontalis [41], two snake species endemic to the south and southeast regions of Brazil. It has been reported that this antivenom is inefficient in fully neutralizing the neurotoxicity and lethality of some heterologous Micrurus species present in different geographic regions of the country [42,43,44,45]. An interesting aspect of some Micrurus venoms, especially those from M. lemniscatus and M. altirostris, is that despite having suitable antigens inducing a satisfactory immune response in horses, the generated antibodies have poor neutralizing capacity [44]. Additionally, the Brazilian commercial antivenom is ineffective in neutralizing lethality. In the case of M. altirostris, it has been demonstrated that its venom departs from others in immunochemical profile, biological activities, and toxin composition [16,42,44,45,46]. This species is distributed in southern Brazil, Uruguay, northeast Argentina, and Paraguay [47].

New strategies and immunization approaches are thus needed to generate improved antivenoms with a broader clinical usefulness landscape. In this regard, lethality and neurotoxicity among Micrurus species can be ascribed to just a few toxins, mainly PLA2 and 3FTx families [13,25,39,40]. This offers the possibility of generating an antivenom comprising a restricted set of anti-PLA2 and anti-3FTx neutralizing antibodies, like those already developed against certain scorpion and snake venoms [48,49,50]. As a proof-of-concept and the first step towards this goal, we have produced and analyzed the immunoreactivity of a set of monoclonal antibodies against the most toxic components of M. altirostris venom. Two PLA2-specific monoclonal antibodies cross-reacted with all the PLA2 molecules from M. altirostris venom, inhibiting their catalytic activity and myotoxicity. They also exhibited paraspecificity against PLA2s from Naja naja venom, demonstrating the conservation of paraspecific neutralizing epitopes across the Elapid family.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of the Major Toxic Components of M. altirostris Venom

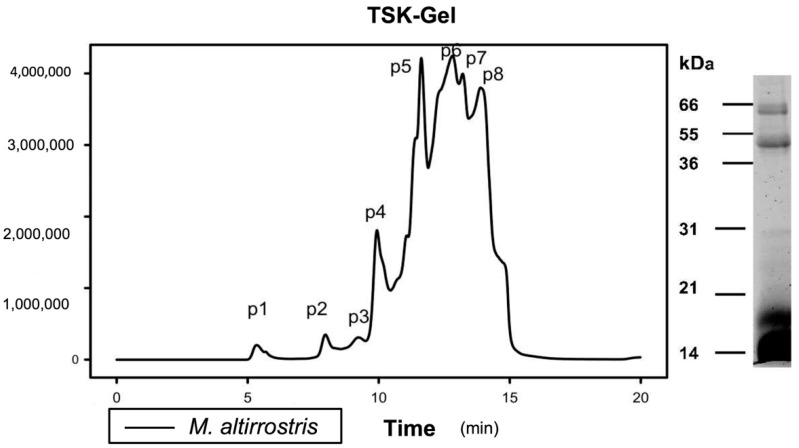

The toxicity of M. altirostris was analyzed using a toxicovenomics approach [51]. Briefly, the venom was fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography and measuring the LD50 of each manually collected fraction (Figure 1). Eight fractions were collected, and doses up to 8 μg/20 g per mouse were injected. Four fractions, P4, P6, P7, and P8, caused lethal effects, with LD50 of 3.3, 6.92, 7.07, and 2.97 μg per animal, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1.

M. altirostris venom fractionation by gel filtration. The crude venom (20 mg) was submitted on TSK®-gel filtration. On the right side, an SDS-PAGE (15%) of the same venom was carried out under reducing conditions.

Table 1.

An overview of lethal toxicity of M. altirostris venom compounds. The venom was fractionated by TSK-gel filtration (Figure 1), and the samples peak 1 to peak 8 (P1–P8) were identified by chromatogram comparison of RP-HPLC analyses (Figures S1 and S2). For the samples that showed lethality with less than 8 μg/mice (~20 g), determined by six mice/dose, the LD50 is indicated next to the sample number.

| Gel Filtration Sample (LD50 μg/Animal) |

RP-HPLC Analyses | Protein Identification * |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 31 | LAO |

| P2 | 31 | LAO |

| P3 | 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 | PLA2 |

| P4 (3.3) | 17 20, 21, 23–25 |

3FTx (10.1%) PLA2 |

| P5 | 30 1–5, 7, 8, 10, 13, 16 20, 21, 22, 23 |

LIPA 3FTx PLA2 |

| P6 (6.92) | 1–9, 13 21 |

3FTx PLA2 (6.3%) |

| P7 (7.07) | 1–9, 13 21 |

3FTx PLA2 (6.3%) |

| P8 (2.97) | 2, 3, 5, 8, 1. | 3FTx |

* LAO—L-amino-oxidase; PLA2 phospholipase A2; 3FTx—three-finger toxin.

The toxins present in these lethal fractions were identified by comparing their reverse-phase chromatographic profile with the whole venom run under the same conditions of the proteome previously characterized and reported in [16]. Table 1 shows the correlation between fractions from size exclusion and reverse-phase chromatographic separations. P4 comprised mainly PLA2 molecules; P6 and P7 contained 3FTxs and less than 6.4% of PLA2 molecules; and P8 was constituted of 3FTxs (Figures S1 and S2).

2.2. Monoclonal-Based Antivenomics Analyses of Antibodies against M. altirostris Venom Toxins

Size-exclusion chromatography of fraction P5 showed that M. altirostris venom contains roughly equal amounts of 3FTx and PLA2 molecules and is a less toxic fraction. This fraction was selected for mice immunization and subsequent generation of five stable hybridoma cells. Three monoclonal antibodies were specific for 3FTx and two for PLA2 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of the target of monoclonal antibodies. The specificity showed by each monoclonal antibody produced against 3FTx and PLA2 molecules. The reactivity was measured by ELISA (Supplementary Materials).

| Monoclonal | Target | |

|---|---|---|

| 3FTx | PLA2 | |

| 1E8 | ++ 1 | |

| 2G2 | ++ | |

| 2B1 | ++ | |

| 3B2 | +++ | |

| 4B3 | +++ | |

1 The increase of absorbance quantified as follow ++ DO ≤ 2 > 1, +++ DO > 2.

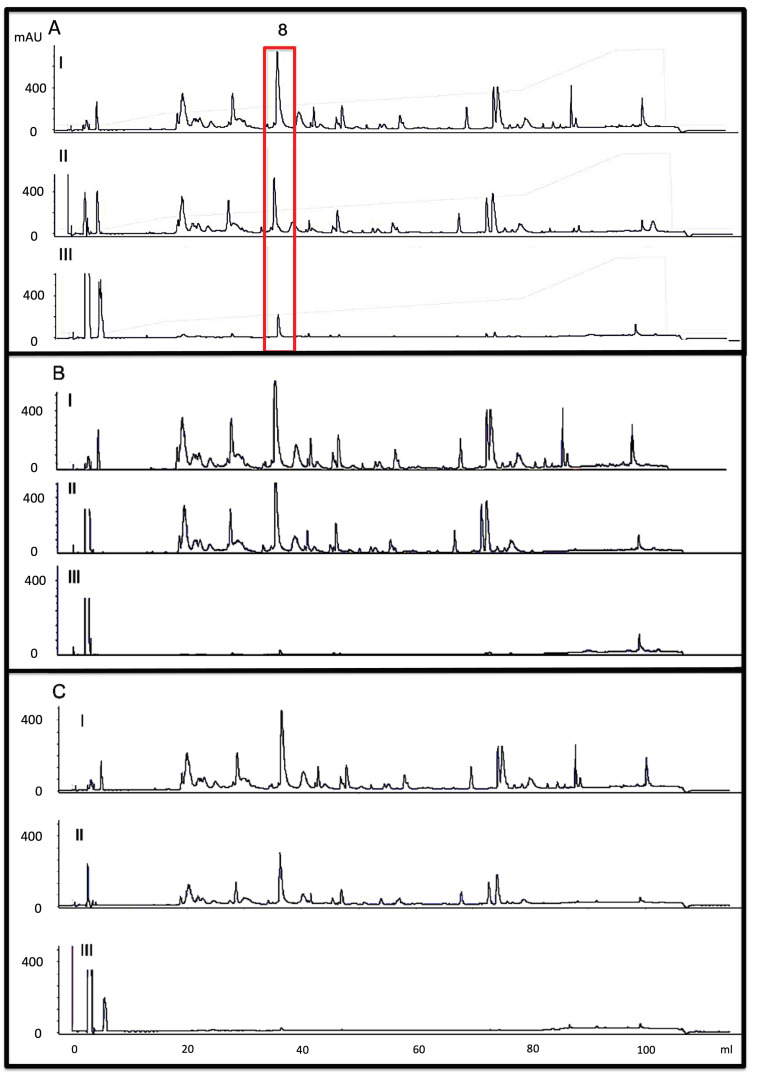

The identification of those toxins exhibiting toxin-family-specific epitopes recognized by mAbs was assessed by affinity chromatography-based antivenomics. Regarding the mAbs recognizing 3FTx (2G2, 2B1, and 4B3), our results revealed that only 4B3 showed specificity for the toxin present at peak 8 (P8), which has a high similarity to postsynaptic type-I α-neurotoxin (transcript MALT0059) with a molecular mass of 6688.2 Da (Figure 2A). Furthermore, 3FTxs displayed a high diversity of proteoforms, the mAbs lacked a broad binding capacity into this toxin family, or showed poor affinity (Figure 2B,C), hindering them for further characterization. On the other hand, monoclonal antibodies exhibited paraspecific binding towards PLA2. All PLA2 molecules from the venom of M. altirostris were recognized by the pair of monoclonal antibodies secreted by clones 3B2 and 1E8. Specifically, mAb 3B2 identified one proteoform eluted in fraction 20 of RP-HPLC (Figure 2D), the PLA2 molecule encoded by transcript F5CPF0 [16]. Except for fraction 20 (Figure 2E) mAb, 1E8 showed a broad binding capacity recognizing all PLA2 molecules, including the transcripts F5CPF1 and AED89576. The paraspecific complementary binding was further investigated to ascertain possible neutralization of the enzymatic and toxic activities of PLA2s.

Figure 2.

Monoclonal-based antivenomics. Five monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were analyzed in these experiments. (A) shows the results to mAb 4B3, (B) to mAb 2G2, (C) to mAb 2B, (D) to mAb 3B2, (E) to mAb 1E8, and Panel (F) to the association of mAb 1E8 and 3B2. The RP-HPLC separation of M. altirostris venom (2 mg) is demonstrated in (A–I), and this chromatogram was used for comparison with (B–F) experiments. The non-bound fractions from monoclonal antibodies’ affinity columns were analyzed in A-II, B-II, C-II, D-II, E-II, and F-II. The reverse-phase separations of the monoclonal-immunocaptured proteins are demonstrated in A-III, B-III, C-III, D-III, and E-III. Red boxes indicate peaks retained by the antibodies. Green box indicate other PLA2 peaks not retained by 3B2 mAB.

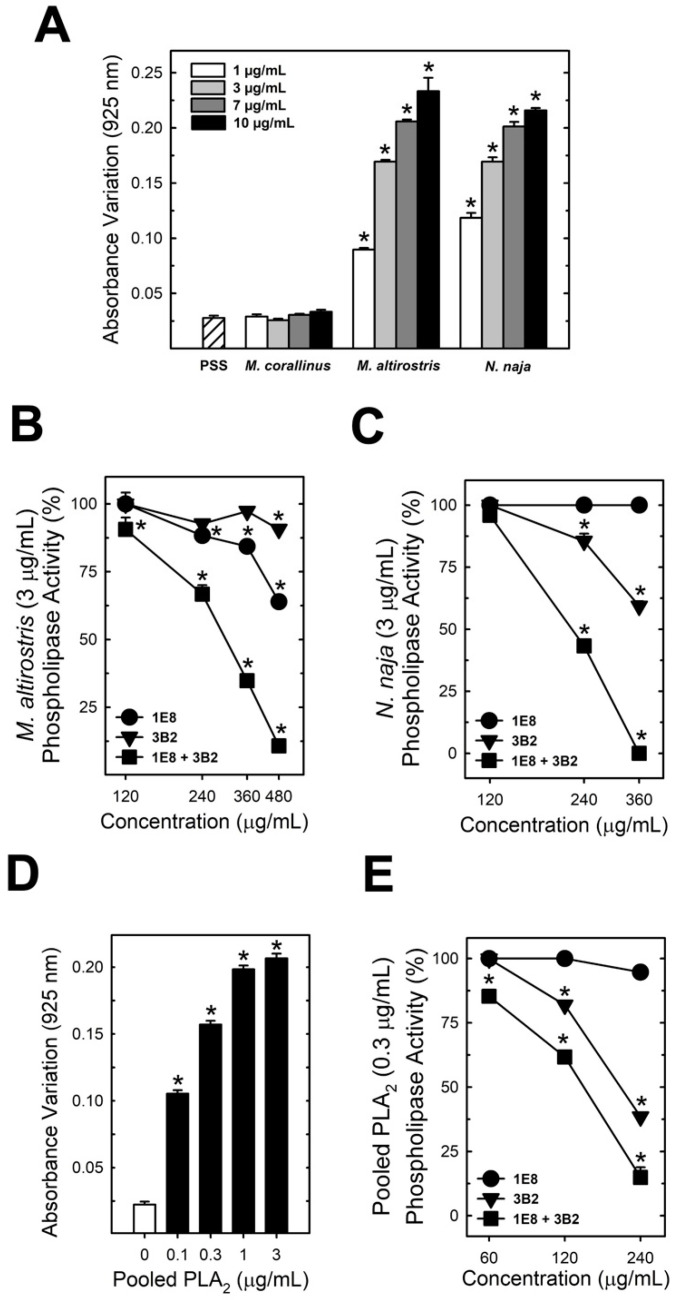

2.3. Neutralization Properties of Monoclonal Antibodies towards PLA2 Toxicity

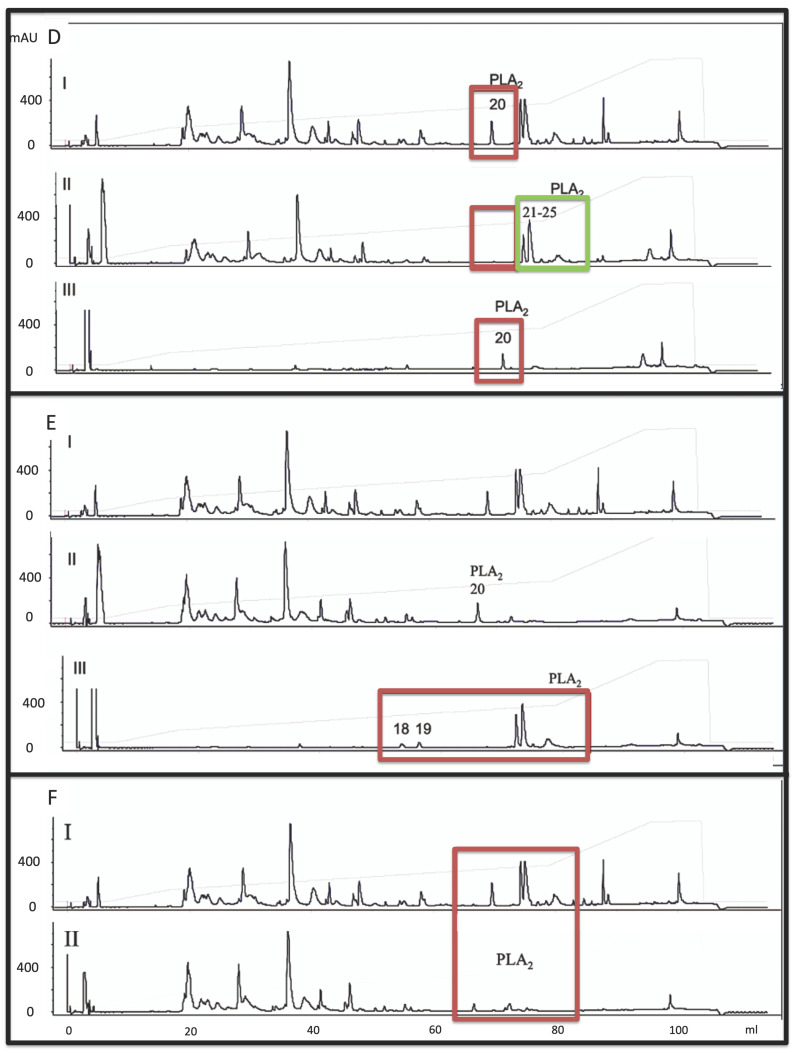

The ability of the mAbs to neutralize PLA2 catalytic activity was tested for the venom of M. altirostris and Naja naja. In addition, a pool of PLA2 from M. altirostris venom (P4 from gel filtration) was used as a positive control (Figure 3A,D). Analysis of the concentration-dependent effect of M. altirostris (1–10 µg), N. naja (1–10 µg) crude venoms, and pooled PLA2 (0.1–3 µg) were used to assess 3 µg of venoms and 0.3 µg of pooled PLA2 as a suitable challenge dose (Figure 3A,D). Neither mAb 3B2 nor 1E8 were 100% efficient in neutralizing the PLA2 activity of 3 µg of M. altirostris venom (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of mAbs on the PLA2 enzymatic activity. Effect of immunoglobulins from clones 1E8 and 3B2 toward phospholipase activity. (A) shows the absorbance variation promoted by M. corallinus, M. altirostris, and Naja naja snakes (1–10 µg/mL) in an egg yolk solution (n = 8). (B,C) display respectively, the inhibition of M. altirostris (3 µg/mL) and N. naja venom (3 µg/mL) phospholipase activity by two immunoglobulins from clones 1E8 and 3B2 alone or as a mixture. (D), the change in the absorbance of egg yolk solution promoted by pooled PLA2 (P4) is shown. (E) displays the inhibition of pooled PLA2 (P4—0.3 µg/mL) by the immunoglobulins from clones 1E8 and 3B2 alone or combined. Data express mean ± SEM. (n = 8) * p < 0.05 vs. venom (B,C) or pooled PLA2 (E). Filled squares represented on (B,C,E) indicate that each mAb was combined according to the concentration indicated in the abscissa axis.

However, the mixture containing the same amount of each mAb enhanced the neutralizing capability (Figure 3B), further pointing to a synergistic effect in the reactivity of the mAb mixture. Similarly, mAbs 3B2 and 1E8 neutralized the enzymatic PLA2 activity of N. naja venom (Figure 3C) and pooled PLA2 (Figure 3E).

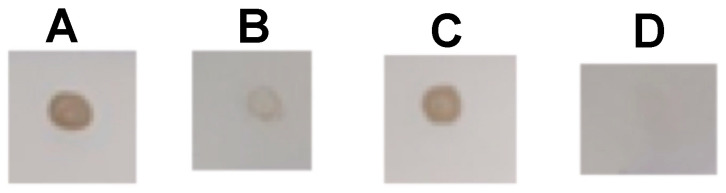

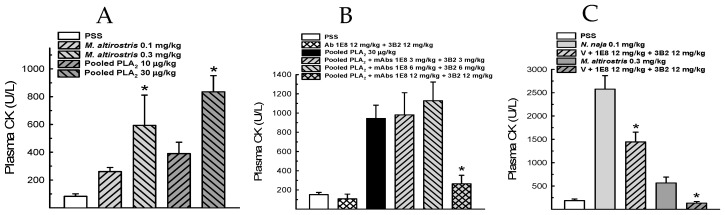

Each antibody was submitted to check its capability to recognize the native or denatured M. altirostris venom. Dot blot results showed that both mAbs were more effective against the native venom (Figure 4). These results point to the presence of conserved epitopes as the structural basis for the capability of mAbs 3B2 and 1E8 binding and inhibition of the enzymatic activity of PLA2 molecules. These results strongly suggest the implications of conformational structure to the epitopes for mAb 1E8 and 3B2. The synergic effect led to the inhibition of PLA2 molecules from phylogenetically distant elapid snakes (Figure 3C). Combined, these antibodies also neutralize PLA2 myotoxicity in vivo (Figure 5). The M. altirostris venom increased the plasma CK activity dose-dependently (Figure 5A).

Figure 4.

Dot blot of the M. altirostris venom against the monoclonal antibodies 1E8 (A,B) and 3B2 (C,D). In (A,C), native venom, (B,D) denatured venom: boiled for 5 min with 5% 2-mercaptoethanol.

Figure 5.

Effect of mAbs on myotoxicity. (A) shows the myotoxic effect of M. altirostris and pooled PLA2 (P4) in mice (n = 4–8). (B) the antagonism of the higher dose of immunoglobulins from clones 1E8 and 3B2 against pooled PLA2 (n = 4). (C) displays the antagonism of this same dose against N. naja and M. altirostris crude venoms. (n = 4). Data express mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 vs. PSS (A) and * p < 0.05 vs. related venom in (B,C).

Monoclonals 1E8 and 3B2 synergically neutralized this activity when pre-incubated with the venom. Similarly, the monoclonal antibodies neutralized the myotoxic activity of the pool of PLA2 (P4—Figure 5B). Regarding N. naja venom, which showed higher myotoxic activity than M. altirostris venom (Figure 5C), the mixture of monoclonal antibodies 1E8 and 3B2 partially antagonized this activity.

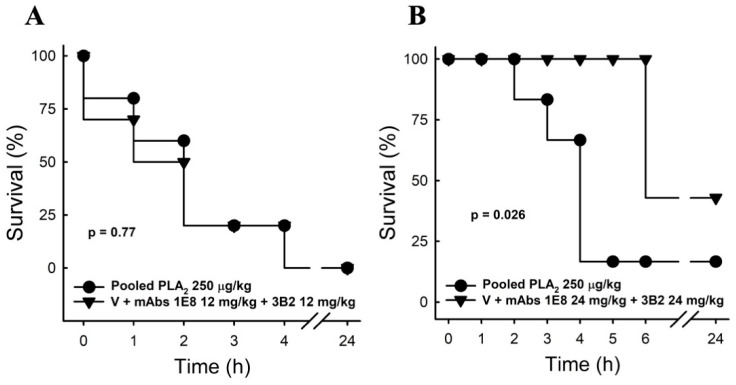

We then evaluated the capacity of these antibodies to neutralize the lethal activity of PLA2s. Since M. altirostris whole venom presents a high lethality also due to 3FTxs, we used the fraction P4 to evaluate the ability of mAbs 1E8 and 3B2 to neutralize the lethality of PLA2. To this end, we pre-incubated mAbs 1E8 and 3B2 (12 or 24 mg/kg each) with 1.5 × DL50 of the pooled PLA2s in fraction P4. The combination of both mAbs (24 mg/kg each) decreased the lethality of the pooled PLA2, thereby increasing by 50% the survival time of all treated animals and protecting more than 60% from death (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Survival curve. Mice were injected with pooled PLA2 alone or premixed for 15 min with immunoglobulins from clones 1E8 and 3B2 (i.p.) 12 mg/kg (A) or 24 mg/kg (B), and survival was observed for 24 h (n = 6–7). Data express the percentage of live mice, and the p-value represents the Mantel–Cox test analysis.

3. Discussion

Since the first experimental snake antivenom was raised in pigeons against the venom from Sistrurus catenatus Sewall, 1887, antivenom technology (essentially using immunization of large mammals with a mixture of crude venoms as antigen) has remained relatively unchanged for most of the 20th century [52]. Only recently, new therapeutic monoclonal antibodies or fragments of antibodies for antagonizing the effects of envenomation caused by spiders, scorpions, and snakes have been reported [48,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Monoclonal and recombinant antibodies have demonstrated effective neutralization activity of low-complexity venoms [59]. In this respect, El Ayeb and Rochat (1988) first generated monoclonal antibodies specific for the Androctonus australis AaH2 toxin, which exhibited neutralizing activity [60]. Licea et al. [61] also characterized a monoclonal antibody that neutralized Centruroides noxius venom on the ratio of 6 ug F(ab’)2 per ug of dose of venom. These approaches have been improving, and new applications in the production of antivenoms are emerging, like the production of humanized-camel single-domain antibodies, scFvs, or recombinant human monoclonals obtained by phage display, among others [53,62,63]. Our present work aimed to generate monoclonal antibodies with broad specificity toward lethal toxins from Micrurus altirostris venom.

Micrurus venoms are not readily available; since these snakes have an ophiophagus diet, they are hardly maintained in captivity. In addition, due to their small size and small gland, they produce a low amount of venom in each extraction, thus hindering the production of anti-elapidic serum [15]. In that sense, obtaining mABs is an important strategy to increase antibody titles. Micrurus venoms are relatively simple regarding the class of lethal toxin families, which comprise mainly 3FTXs and PLA2 molecules [25,29,39]. Likewise, the lethality of M. altirostris venom is triggered by the same protein classes. High toxicity (LD50 of 3.3 and 2.9 µg/mouse) was found on the venom fractions enriched with PLA2s (P4) and 3FTXs (P8), respectively (Table 1). Regarding the PLA2, the venomics analysis identified eight proteoforms (13.7% of total venom protein), and among them five were assigned for the transcripts F5CPF1, F5CPF0, and AED89576, pointing to the presence of isoforms. The transcript F5CPF0 was identified in RP-HPLC peak 20, which was specifically recognized by mAb 3B2. F5CPF1 and AED89576 corresponding to PLA2s, which share a conserved structural epitope recognized by mAb 1E8 (RP-HPLC peaks 21–25).

It is worth mentioning that F5CPF1 and AED89576 showed close phylogenetic relationships with MmipPLA2, the most abundant PLA2 of M. mipartitus venom (accounting for nearly 10% of the total venom protein) [41]. Functional characterization of MmipPLA2 revealed a toxin with low enzymatic activity and myotoxicity but high lethality in mice [40]. A similar functional pattern was found for fraction P4 isolated from M. altirostris venom (Table 1, Figure 3D), highlighting the importance of developing inhibitors for each type of PLA2. The monoclonal antibodies produced here could inhibit the catalytic activity and in vivo myotoxicity of M. altirostris, N. naja venoms, and pooled PLA2. Furthermore, these antibodies increased the survival time of all envenomed animals by 50% by protecting more than 60% from death (Figure 5). It is worth emphasizing that the protocol used for the evaluation of survival uses premixed antibodies/venom proportions, which implies a limitation for a clinical application that must be observed in further experiments.

The results indicate the involvement of two epitopes in this process, both antibodies inhibiting enzymatic and toxic activities. Moreover, these anti-PLA2 mAbs exhibited paraspecificity against PLA2 molecules from N. naja venom, suggesting the conservation of neutralizing paraspecific structural epitopes across the Elapidae family. Both mABs 1E8 and 3B2 recognized structural PLA2 epitopes, demonstrating that despite differences in primary structure, these toxin classes present high immunological similarity, corroborating the existence of antibodies sharing broad neutralization of family-specific snake venom toxic proteins. Chavanayarn et al., 2012 [62], produced Humanized Single Domain Antibodies against the PLA2s from Naja kaouthia, inhibiting enzymatic activity. By modeling and docking analysis, they suggested that these antibodies’ CDR loops are inserted into PLA2 catalytic grooves. We aligned the sequence from Naja naja, Naja atra, and M. altirostris PLA2s and verified manually that the residues from the calcium binding site and lipid binding site are shared between these molecules (Figure S3). Our data indicate that a similar mechanism may be involved. Future structural analyses are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Our results suggest the applicability of mAb 1E8 and 3B2 to supplement current conventional antivenoms to improve the neutralization capacity of the antisera. For example, the Brazilian coral snake antivenom lacks neutralization activity towards the venom of M. altirostris [43,44,45]. The antivenomic analysis revealed low immunoreactivity for some toxins from M. altirostris venom, particularly PLA2 F5CPF0, which entirely escaped immunodepletion by coral snake antivenom [16]. However, this toxin was neutralized by monoclonal antibodies described in this work. Our results demonstrate potential applicability, especially to neutralize the lethal activity of coral snakes from venoms enriched with PLA2, including M. fulvius, M. moscatensis, and M. dumerilli, which have 58%, 55%, and 52% of PLA2, respectively [29]. Furthermore, other preparations may improve antivenoms’ effectiveness, such as combining polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies with neostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor that has been applied to overcome the effects of α-neurotoxins [64,65]. Future studies must confirm if this supplementation to antielapidic sera will produce more protection. Additionally, new immunization strategies were recently driven by the vaccine market and consequently brought a lot of innovation to this area; these include DNA or mRNA vaccines, among others [66,67], and they can be used to develop new antisera.

Two divergent patterns of coral snakes’ venom composition, 3FTx-rich and PLA2-rich, have been revealed by proteomics studies [20,28,29]. Our work indicates the potential use of monoclonal antibodies 1E8 and 3B2 for neutralizing the PLA2 molecules of PLA2-rich venoms of coral snakes from Central and North America.

4. Conclusions

Our present work aimed to generate monoclonal antibodies with broad specificity toward lethal toxins from Elapidae venom. The toxicity was analyzed using the toxicovenomics approach, and all PLA2 molecules were recognized by the pair of monoclonal antibodies, pointing to a synergistic effect in the reactivity. These antibodies increased by 50% the survival time of all envenomed animals by protecting more than 60% from death. They inhibited PLA2 catalytic activity and showed paraspecific neutralization against the myotoxicity from the lethal effect of Micrurus altirrostris and Naja naja venoms’ PLA2s. Epitope conservation among venom PLA2 molecules suggests the conservation of neutralizing paraspecific structural epitopes across the Elapidae family and the possibility of generating pan-PLA2 neutralizing antibodies.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Materials

Crude venom of M. altirostris was pooled from adult specimens from Southern Brazil and kept in the serpentarium of Núcleo de Ofiologia de Porto Alegre (NOPA), Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, under the register of IBAMA no. 1/43/1999/000764-9, and Sisgen code A9F3694. Crude venoms were lyophilized and stored at −20 °C until use. Naja naja (batch no. V-9125) venom was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (Saint Louis, MS, USA). Creatine kinase (CK) activity was determined using a CK NAC® kit from Bioclin (Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil). Male Swiss mice (20.0 ± 2.0 g) used for the study received water and food ad libitum and were kept under a natural light cycle. Animal handling was conducted in agreement with Ethical Principles in Animal Research and approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation from Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro and from Instituto Vital Brazil (CEUA-UFRJ: no. 01200.001568/2013-87; CEUA-IVB: no. 001/2016).

5.2. ELISA

Microtiter plates were coated with the proteins eluted (1 µg/well) in the different reverse-phase HPLC fractions isolated as described [16]. Plates were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) before incubating with monoclonal antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were then washed with PBS with 0.05% Tween 20, and antigen-antibody complexes were detected using the peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG/ortho-phenylenediamine colorimetric method, following the manufacturer’s (Sigma, Saint Louis, MS, USA) instructions. Absorbance was recorded at 492 nm.

5.3. M. altirostris Venom Fractionation and In Vivo Toxicity Analysis (LD50)

Crude venom (20 mg in Tris-HCl pH 7.5) was fractionated by TSK®-gel size-exclusion chromatography and yielded eight fractions. To determine the median lethal dose (LD50), we followed the protocol described by World Health Organization [68]. Briefly, 0.5 mL of the whole venom and the manually collected fractions from the TSK® column (in PBS) were intraperitoneally administered to 18–22 g male Swiss mice. Six mice were used for each dose (four dose levels per test), and deaths occurring within 24 h were recorded. The LD50 was calculated by probit analysis, using the formula LD50 = LD100 − ∑ (a × b)/n, where: n = total number of animals in the group; a = the difference between two successive doses of administered extract/substance; b = the average number of dead animals in two successive doses; and LD100 = lethal dose causing 100% death of all test animals [60].

The Identification of venom components eluted in the gel-filtration chromatographic fractions was performed by chromatogram comparison with the venomic characterization previously described in [16]. Briefly, the venom or gel-filtration fractions were separated by reverse-phase HPLC using a Shimadzu chromatograph and a Teknokroma Europa C18 (0.4 cm × 25 cm, five μm particle size, 300 Å pore size) column eluted at 1 mL/min with a linear gradient of (5–70%) of 0.1% TFA in water (solution A) and 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (solution B). The absorbance was recorded at 214 nm, and peaks were manually collected.

5.4. Production and Purification of Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs)

Monoclonal antibodies were produced as described by [69] with modifications. Briefly, BALB/c mice were inoculated with fraction five (P5) of M. altirostris venom. The P5 was chosen because it presents the two main families of toxins in a similar ratio. Furthermore, the low toxicity allowed increasing the amount of toxins from P5 up to 30 μg per animal in the immunization process. Then, popliteal lymph node cells from BALB/c mice were fused with SP2-O cells (2:1) using polyethylene glycol 4000 (Merck). Hybrid cells were selected in RPMI 1640 medium plus 3% HAT (hypoxanthine 10 mM, aminopterin 40 mM and thymidine 1.6 mM) (GibcoBRL) containing 10% FCS (GibcoBRL) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The supernatant was screened for toxin-specific antibodies by ELISA, as described above. Antibody-secreting cells were expanded and cloned twice at limiting dilution. The mAbs contained in the culture supernatants were purified by affinity chromatography on protein-A Sepharose (Pharmacia) equilibrated in borate saline buffer (BSB), pH 8.5. The proteins were eluted in 0.2 glycine/HCl buffer, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 2.8, and dialyzed in BSB.

5.5. Monoclonal-Based Antivenomics

We employed the second-generation affinity chromatography-based antivenomic protocol [70]. To this end, 400 μL of NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) were packed in a column and washed with 10–15 matrix volumes of cold 1 mM HCl, followed by two matrix volumes of coupling buffer (0.2 M NaHCO3, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.3) to adjust the pH of the column between 7.0–8.0. Then, 1 mg of monoclonal antibody in 300 µL of coupling buffer was incubated with the activated matrix in an orbital shaker overnight at 4 °C. Non-saturated reactive NHS-matrix functional groups were blocked with 400 μL of 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, overnight at 4 °C in an orbital shaker. The affinity columns were 6× washed alternating at high (0.1 M acetate buffer, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 4.0–5.0) and low pH (0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5). Before incubating with crude venom, the affinity matrix was equilibrated with five matrix volumes of binding buffer (PBS). For the immunoaffinity assay, 300 μg of M. altirostris venom were incubated 3 h with the matrix at room temperature (~25 °C) in an orbital shaker. As a specificity control, 300 μL of Sepharose 4 Fast Flow matrix was incubated with venom, and the mock column was developed in parallel to the immunoaffinity column. After eluting the non-binding fraction, the affinity column was washed twice with PBS. The immunocaptured venom proteins were eluted with 2.5 matrix volumes of elution buffer (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.0) and neutralized with neutralization buffer (1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0). The non-retained and the immunocaptured venom fractions were fractionated by reverse-phase HPLC and identified by overlap with the chromatogram reported in the previous homologous venom proteome characterization study [16].

5.6. Dot Blot

For the dot blot, denatured venom, after boiling (5 min) with 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, or native M. altirostris crude venoms were applied directly to membranes (strips) of nitrocellulose at a concentration of 10 μg/μL. The nitrocellulose-sensitized membranes were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with a blocking solution (5% skim milk in Tris-saline) under constant stirring. At the end of the reactive group blocking, the membranes were washed for 3 min each with Tris-saline. Then the membranes were incubated with monoclonal antibodies 1E8 or 3B2 for 2 h under constant stirring at room temperature. Membranes were subjected to a new wash cycle with Tris-saline and incubated for 2 h under continuous stirring with peroxidase-labeled mouse anti-IgG sheep antibody diluted 1:5000 in Tris-saline containing 1% skim milk. The reaction was developed with the chromogenic substrate, 0.05% 4-chloro-1-naphthol in 15% methanol, and color was developed by adding 0.03% H2O2.

5.7. Phospholipase Activity In Vitro

Phospholipase A2 activity was assessed by the turbidimetric assay [71] adapted by [72]. The stock substrate was prepared by shaking one chicken egg yolk in 150 mM NaCl to a final volume of 100 mL. This substrate was stored at 4 °C until used. For the PLA2 activity assay, a 1 mL substrate solution containing 0.63 mL of a 10% dilution of the egg yolk stock suspension, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.01% taurocholic acid, and 5.0 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), was freshly prepared. Then, 0.13 mL of this solution was added to each microtiter plate well containing either 0.07 mL of saline, venom alone, or venom/mAb mixture. The ELISA microplate was kept at 37 °C during the procedure. The reaction was started by adding venom (1–30 µg/mL) of Micrurus altirostris, M. corallinus, Naja naja, or a pool of PLA2 purified from M. altirostris venom (0.1–3 µg/mL) into the yolk solution. The concentration of 3 µg/mL of venoms and 0.3 µg/mL of pooled PLA2 was chosen to challenge the mAb 1E8 and 3B2 (60–480 µg/mL) alone or mixed; the absorbance of the solutions was measured at 925 nm every 5 min for 30 min for crude venom and 60 min for pooled PLA2. Data were expressed as absorbance reduction and percentage venom activity.

5.8. Myotoxic Activity In Vivo

We evaluated the myotoxicity of M. altirostris, N. naja venoms, and P4 (pooled PLA2) by measuring the increase of plasma CK activity induced by intra-muscular (i.m.) injection of venom alone or associated with mAb (3B2 and 1E8). The venom was dissolved in physiological saline solution (PSS) to a final volume of 0.16 mL and injected into the rear thigh of mice as described previously [73,74]. Negative controls consisted of mice injected with the same volume of PSS. To evaluate the antimyotoxic activity of the mAb (3B2 and 1E8), the protocol used was pre-incubation. Before injection, the venoms were dissolved in PSS and incubated with mAb 3B2, 1E8 (1:1) for 15 min at room temperature. The doses used here were based on the dose-response study, from which we chose the most effective ones. Enzyme activity was expressed as international units, where 1 U is the amount that catalyzes the transformation of 1.0 µmol of the substrate at 25 °C per minute.

5.9. Inhibition of Lethality by mAbs

To evaluate the lethality effect of pooled PLA2 (P4) and the protection by mAb (3B2 and 1E8) in mice (groups of 6–7), we used the method as described in [75] with modification. Briefly, 1.5 LD50 (5 µg/animal or 250 µg/kg) of P4 and the mAb (12 and 24 mg/kg of each mAb) were pre-incubated for 15 min and then administered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Mice were observed for 24 h. Each hour the number of survivors was counted.

5.10. Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. The number of experiments performed is provided in the legends of the figures, for instance, as (n = 5), meaning there were five samples analyzed in one experiment. One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to compare groups with one variable, followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test. For two variables, Two-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. The p-value < 0.05 was used to indicate a significant difference between the means. The software GraphPad Prism version 5.01 was used to provide statistical analysis. Graphs were made using the Sigmaplot program version 10.0.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia Castanheiras (IVB) for her support at the LD50 experiments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/toxins15010015/s1, Figure S1:The chromatograms separation of M. altirostris venom by RP-HPLC showing the peaks that were previously identified [15]; Figure S2: The chromatograms separation of TSK fractions by RP-HPLC; Figure S3: Alignment of phospholipases A2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C-N., J.J.C. and R.B.Z.; methodology, C.C.-N., M.A.S., R.T.-A., M.M.-M. and J.G.F.; validation, C.C.-N., M.A.S. and L.S.; formal analysis, C.C.-N., M.A.S., J.G.F. and L.S.; investigation, C.C.-N., M.M.-M., M.A.S., J.G.F., M.L.-A. and M.L.M.-A.; resources, J.J.C., P.A.M. and R.B.Z.; data curation, C.C.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.-N.; writing—review and editing, C.C.-N., M.A.S., J.J.C., P.A.M. and R.B.Z.; visualization, C.C.-N. and M.A.S.; supervision, J.J.C., P.A.M., L.S. and R.B.Z.; project administration, R.B.Z.; funding acquisition, J.J.C., P.A.M. and R.B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Animal handling was conducted in agreement with Ethical Principles in Animal Research and approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro and Instituto Vital Brazil on 1 June 2016 and 6 October 2016, respectively, under the protocol numbers (CEUA-UFRJ: no. 01200.001568/2013-87; and CEUA-IVB: no. 001/2016; dates: 1 June 2016 and 6 October 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Key Contribution

We produced a pair of monoclonal antibodies that neutralize the PLA2 enzymatic and toxic activities of paraspecific venoms (Micrurus altirostris and Naja naja). Our results indicate the possibility of generating pan-PLA2 neutralizing antibodies.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by FAPERJ (grants E-26/010.003016/2014; E-26/200.963/2021 E-26-010.101030/2018 to R.B.Z. E-26/200.920/2021 to PAM); CNPq (Grant 308376/2020-0 to R.B.Z. and 309531/2019-5 to P.A.M.); and BFU2020_PID2020-119593GB-I00 from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Madrid (Spain) to J.J.C.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Slowinski J.B., Keogh J.S. Phylogenetic relationships of elapid snakes based on cytochrome b mtDNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2000;15:157–164. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1999.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slowinski J.B., Boundy J., Lawson R. The Phylogenetic Relationships of Asian Coral Snakes (Elapidae: Calliophis and Maticora) Based on Morphological and Molecular Characters. Herpetologica. 2001;57:233–245. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castoe T.A., Smith E.N., Brown R.M., Parkinson C.L. Higher-level phylogeny of Asian and American coralsnakes, their placement within the Elapidae (Squamata), and the systematic affinities of the enigmatic Asian coralsnake Hemibungarus calligaster. Zool J. Linnean Soc. 2007;15:809–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00350.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell J.A., Lamar W.W. The venomous reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY, USA: 2004. 1032p [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slowinski J.B. A Phylogenetic analysis of the New World coral snakes (Elapidae: Leptomicrurus, Micruroides, and Micrurus) based on allozymic and morphological characters. J. Herpetol. 1995;29:325–338. doi: 10.2307/1564981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roze J.A. Coral Snakes of the Americas: Biology, Identification and Venoms. Krieger Publishing Company; Malabar, FL, USA: 1996. 328p [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gutiérrez J.M., Lomonte B., Portilla E., Cerdas L., Rojas E. Local effects induced by coral snake venoms: Evidence of myonecrosis after experimental inoculations of venoms from five species. Toxicon. 1983;21:777–784. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(83)90066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutiérrez J., Rojas G., da Silva N.J., Núñez J. Experimental myonecrosis induced by the venoms of South American Micrurus (coral snakes) Toxicon. 1992;30:1299–1302. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90446-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weis R., McIsaac R.J. Cardiovascular and muscular effects of venom from coral Micrurus fulvius. Toxicon. 1971;9:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(71)90073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vital-Brazil O. Coral snake venoms: Mode of action and pathophysiology of experimental envenomation. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. S. Paulo. 1987;29:119–126. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46651987000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warrell D.A. Snakebites in Central and South America: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Clinical Management. In: Campbell J.A., Lamar W.W., editors. The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY, USA: 2004. pp. 709–761. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucaretchi F., Capitani E.M., Vieira R.J., Rodrigues C.K., Zannin M., Da Silva N.J., Jr., Casais-e-Silva L.L., Hyslop S. Coral snake bites (Micrurus spp.) in Brazil: A review of literature reports. Clin. Toxicol. 2016;54:222–234. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1135337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olamendi-Portugal T., Batista C.V., Restano-Cassulini R., Pando V., Villa-Hernandez O., Zavaleta-Martínez-Vargas A., Salas-Arruz M.C., de la Vega R.C., Becerril B., Possani L.D. Proteomic analysis of the venom from the fish eating coral snake Micrurus surinamensis: Novel toxins, their function and phylogeny. Proteomics. 2008;9:1919. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aird S.D., da Silva N.J., Jr., Qiu L., Villar-Briones A., Saddi V.A., Grau M.L., Mikheyev A.S., Pires de Campos Telles M. Coralsnake Venomics: Analyses of Venom Gland Transcriptomes and Proteomes of Six Brazilian Taxa. Toxins. 2017;9:187. doi: 10.3390/toxins9060187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leão L.I., Ho P.L., Junqueira-de-Azevedo I.L. Transcriptomic basis for an antiserum against Micrurus corallinus (coral snake) venom. BMC Genom. 2009;5:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrêa-Netto C., Junqueira-de-Azevedo I.deL., Silva D.A., Ho P.L., Leitão-de-Araújo M., Alves M.L., Sanz L., Foguel D., Zingali R.B., Calvete J.J. Snake venomics and venom gland transcriptomic analysis of Brazilian coral snakes, Micrurus altirostris and M. corallinus. J. Proteom. 2011;74:1795. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez J., Alape-Girón A., Angulo Y., Sanz L., Gutiérrez J.M., Calvete J.J., Lomonte B. Venomic and antivenomic analyses of the Central American coral snake, Micrurus nigrocinctus (Elapidae) J. Proteome Res. 2011;10:1816. doi: 10.1021/pr101091a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rey-Suárez P., Núñez V., Gutiérrez J.M., Lomonte B. Proteomic and biological characterization of the venom of the redtail coral snake, Micrurus mipartitus (Elapidae), from Colombia and Costa Rica. J. Proteom. 2011;75:655. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciscotto P.H., Rates B., Silva D.A., Richardson M., Silva L.P., Andrade H., Donato M.F., Cotta G.A., Maria W.S., Rodrigues R.J., et al. Venomic analysis and evaluation of antivenom cross-reactivity of South American Micrurus species. J. Proteom. 2011;74:1810. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanz L., de Freitas-Lima L.N., Quesada-Bernat S., Graça-de-Souza V.K., Soares A.M., Calderón L.A., Calvete J.J., Caldeira C.A.S. Comparative venomics of Brazilian coral snakes: Micrurus frontalis, Micrurus spixii spixii, and Micrurus surinamensis. Toxicon. 2019;166:39. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanz L., Quesada-Bernat S., Ramos T., Casais-E-Silva L.L., Corrêa-Netto C., Silva-Haad J.J., Sasa M., Lomonte B., Calvete J.J. New insights into the phylogeographic distribution of the 3FTx/PLA2 venom dichotomy across genus Micrurus in South America. J. Proteom. 2019;200:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bénard-Valle M., Carbajal-Saucedo A., de Roodt A., López-Vera E., Alagón A. Biochemical characterization of the venom of the coral snake Micrurus tener and comparative biological activities in the mouse and a reptile model. Toxicon. 2013;77:6. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carbajal-Saucedo A., López-Vera E., Bénard-Valle M., Smith E., Zamudio F., de Roodt A., Olvera-Rodríguez A. Isolation, characterization, cloning and expression of an alpha-neurotoxin from the venom of the Mexican coral snake Micrurus laticollaris (squamata: Elapidae) Toxicon. 2013;66:64. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margres M.J., Aronow K., Loyacano J., Rokyta D.R. The venom-gland transcriptome of the eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius) reveals high venom complexity in the intragenomic evolution of venoms. BMC Genom. 2013;14:531. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vergara I., Pedraza-Escalona M., Paniagua D., Restano-Cassulini R., Zamudio F., Batista C.V., Possani L.D., Alagón A. Eastern coral snake Micrurus fulvius venom toxicity in mice is mainly determined by neurotoxic phospholipases A2. J. Proteom. 2014;105:295. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernández J., Vargas-Vargas N., Pla D., Sasa M., Rey-Suárez P., Sanz L., Gutiérrez J.M., Calvete J.J., Lomonte B. Snake venomics of Micrurus alleni and Micrurus mosquitensis from the Caribbean region of Costa Rica reveals two divergent compositional patterns in New World elapids. Toxicon. 2015;107:217. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rey-Suárez P., Núñez V., Fernández J., Lomonte B. Integrative characterization of the venom of the coral snake Micrurus dumerilii (Elapidae) from Colombia: Proteome, toxicity, and cross-neutralization by antivenom. J. Proteom. 2016;136:262. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanz L., Pla D., Pérez A., Rodríguez Y., Zavaleta A., Salas M., Lomonte B., Calvete J.J. Venomic Analysis of the Poorly Studied Desert Coral Snake, Micrurus tschudii tschudii, Supports the 3FTx/PLA2 Dichotomy across Micrurus Venoms. Toxins. 2016;8:178. doi: 10.3390/toxins8060178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lomonte B., Rey-Suárez P., Fernández J., Sasa M., Pla D., Vargas N., Bénard-Valle M., Sanz L., Corrêa-Netto C., Núñez V., et al. Venoms of Micrurus coral snakes: Evolutionary trends in compositional patterns emerging from proteomic analyses. Toxicon. 2016;122:7–25. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olamendi-Portugal T., Batista C.V.F., Pedraza-Escalona M., Restano-Cassulini R., Zamudio F.Z., Benard-Valle M., de Roodt A.R., Possani L.D. New insights into the proteomic characterization of the coral snake Micrurus pyrrhocryptus venom. Toxicon. 2018;153:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lippa E., Török F., Gómez A., Corrales G., Chacón D., Sasa M., Gutiérrez J.M., Lomonte B., Fernández J.J. First look into the venom of Roatan Island’s critically endangered coral snake Micrurus ruatanus: Proteomic characterization, toxicity, immunorecognition and neutralization by an antivenom. Proteomics. 2019;30:198. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bénard-Valle M., Neri-Castro E., Yañez-Mendoza M.F., Lomonte B., Olvera A., Zamudio F., Restano-Cassulini R., Possani L.D., Jiménez-Ferrer E., Alagón A. Functional, proteomic and transcriptomic characterization of the venom from Micrurus browni browni: Identification of the first lethal multimeric neurotoxin in coral snake venom. J. Proteom. 2020;225:103863. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2020.103863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mena G., Chaves-Araya S., Chacón J., Török E., Török F., Bonilla F., Sasa M., Gutiérrez J.M., Lomonte B., Fernández J. Proteomic and toxicological analysis of the venom of Micrurus yatesi and its neutralization by an antivenom. Toxicon. 2022;13:100097. doi: 10.1016/j.toxcx.2022.100097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kini R.M., Doley R. Structure, function and evolution of three-finger toxins: Mini proteins with multiple targets. Toxicon. 2010;56:855. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montecucco C., Rossetto O. How do presynaptic PLA2 neurotoxins block nerve terminals? Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:266. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doley R., Zhou X., Kini R.M. Snake Venom Phospholipase A2 Enzymes. In: Mackessy S.P., editor. Handbook of Venoms and Toxins of Reptiles. CCR Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2009. pp. 173–205. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vulfius C.A., Kasheverov I.E., Starkov V.G., Osipov A.V., Andreeva T.V., Filkin S.Y., Gorbacheva E.V., Astashev M.E., Tsetlin V.I., Utkin Y.N. Inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, a novel facet in the pleiotropic activities of snake venom phospholipases A2. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e115428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lomonte B., Calvete J.J., Fernández J., Pla D., Rey-Suárez P., Sanz L., Gutiérrez J.M., Sasa M. Venomic analyses of coralsnakes. In: da Silva N. Jr., Porras L.W., Aird S.D., da Costa Prudente A.L., editors. Advances in Coralsnake Biology: With an Emphasis on South America. Eagle Mountain Publishing, LC; Eagle Mountain, UT, USA: 2021. pp. 483–516. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rey-Suárez P., Floriano R.S., Rostelato-Ferreira S., Saldarriaga-Córdoba M., Núñez V., Rodrigues-Simioni L., Lomonte B. Mipartoxin-I, a novel three-finger toxin, is the major neurotoxic component in the venom of the redtail coral snake Micrurus mipartitus (Elapidae) Toxicon. 2012;60:851. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rey-Suárez P., Núñez V., Saldarriaga-Córdoba M., Lomonte B. Primary structures and partial toxicological characterization of two phospholipases A2 from Micrurus mipartitus and Micrurus dumerilii coral snake venoms. Biochimie. 2017;137:88. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raw I., G.uidolin R., Higashi K., K.elen E.M.A. Antivenins in Brazil. In: Tu A.T., editor. Handbook of Natural Toxins. Volume 5. Marcel Dekker Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1991. pp. 557–581. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moraes F.V., Sousa-e-Silva M.C.C., Barbaro K.C., Leitão M.A., Furtado M.F.D. Biological and immunochemical characterization of Micrurus altirostris venom and serum neutralization of its toxic activities. Toxicon. 2003;41:71. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abreu V.A., Leite G.B., Oliveira C.B., Hyslop S., Furtado M.F., Simioni L.R. Neurotoxicity of Micrurus altirostris (Uruguayan coral snake) venom and its neutralization by commercial coral snake antivenom and specific antiserum raised in rabbits. Clin. Toxicol. 2008;6:519. doi: 10.1080/15563650701647405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka G.D., Furtado M.F., Portaro F.C., Sant’Anna O.A., Tambourgi D.V. Diversity of Micrurus snake species related to their venom toxic effects and the prospective of antivenom neutralization. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010;4:e622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka G.D., Sant’Anna O.A., Marcelino J.R., Lustoza da Luz A.C., Teixeira da Rocha M.M., Tambourgi D.V. Micrurus snake species: Venom immunogenicity, antiserum cross-reactivity and neutralization potential. Toxicon. 2016;117:59. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2016.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreira K.G., Prates M.V., Andrade F.A., Silva L.P., Beirão P.S., Kushmerick C., Naves L.A., Bloch C., Jr. Frontoxins, three-finger toxins from Micrurus frontalis venom, decrease miniature endplate potential amplitude at frog neuromuscular junction. Toxicon. 2010;1:55. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.da Silva N.J., Sites J.W., Jr. Revision of the Micrurus frontalis Complex (Serpentes: Elapidae) Herpetol. Monogr. 1999;13:142. doi: 10.2307/1467062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riaño-Umbarila L., Olamendi-Portugal T., Morelos-Juárez C., Gurrola G.B., Possani L.D., Becerril B. A novel human recombinant antibody fragment capable of neutralizing Mexican scorpion toxins. Toxicon. 2013;76:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eskafi A.H., Bagheri K.P., Behdani M., Yamabhai M., Shahbazzadeh D., Kazemi-Lomedasht F. Development and characterization of human single chain antibody against Iranian Macrovipera lebetina snake venom. Toxicon. 2021;197:106. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2021.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manson E.Z., Kyama M.C., Gikunju J.K., Kimani J., Kimotho J.H. Evaluation of lethality and cytotoxic effects induced by Naja ashei (large brown spitting cobra) venom and the envenomation-neutralizing efficacy of selected commercial antivenoms in Kenya. Toxicon. 2022;14:100125. doi: 10.1016/j.toxcx.2022.100125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lomonte B., Calvete J.J. Strategies in ‘snake venomics’ aiming at an integrative view of compositional, functional, and immunological characteristics of venoms. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2017;28:23. doi: 10.1186/s40409-017-0117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Espino-Solis G.P., Riaño-Umbarila L., Becerril B., Possani L.D. Antidotes against venomous animals: State of the art and prospectives. J. Proteom. 2009;2:183. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hedegaard L., Laustsen A.H., Pus U., Wade J., Villar P., Boddum K., Slavny P., Masters E.W., Arias A.S., Oscoz S., et al. In vitro discovery of a human monoclonal antibody that neutralizes lethality of cobra snake venom. MAbs. 2022;14:2085536. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2022.2085536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Juste M., Martin-Eauclaire M.F., Devaux C., Billiald P., Aubrey N. Using a recombinant bispecific antibody to block Na+ -channel toxins protects against experimental scorpion envenoming. Cell Mol. Life. 2007;2:206. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6401-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.di Tommaso A., Juste M.O., Martin-Eauclaire M.F., Dimier-Poisson I., Billiald P., Aubrey N. Diabody mixture providing full protection against experimental scorpion envenoming with crude Androctonus australis venom. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:14149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.348912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Figueiredo L.F., Dias-Lopes C., Alvarenga L.M., Mendes T.M., Machado-de-Ávila R.A., McCormack J., Minozzo J.C., Kalapothakis E., Chavez-Olórtegui C. Innovative immunization protocols using chimeric recombinant protein for the production of polyspecific loxoscelic antivenom in horses. Toxicon. 2014;86:59. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alvarenga L.M., Zahid M., di Tommaso A., Juste M.O., Aubrey N., Billiald P., Muzard J. Engineering venom’s toxin-neutralizing antibody fragments and its therapeutic potential. Toxins. 2014;6:2541. doi: 10.3390/toxins6082541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carmo A.O., Chatzaki M., Horta C.C., Magalhães B.F., Oliveira-Mendes B.B., Chávez-Olórtegui C., Kalapothakis E. Evolution of alternative methodologies of scorpion antivenoms production. Toxicon. 2015;97:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manson E.Z., Kyama M.C., Kimani J., Bocian A., Hus K.K., Petrilla V., Legáth J., Kimotho J.H. Development and Characterization of Anti-Naja ashei Three-Finger Toxins (3FTxs)-Specific Monoclonal Antibodies and Evaluation of Their In Vitro Inhibition Activity. Toxins. 2022;14:285. doi: 10.3390/toxins14040285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.El Ayeb M., Rochat H. Production of monoclonal antibodies. Scorpion antitoxins: Characterization and molecular mechanisms of neutralization. Arch. Inst. Pasteur Tunis. 1988;65:29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Licea A.F., Becerril B., Possani L.D. Fab fragments of the monoclonal antibody BCF2 are capable of neutralizing the whole soluble venom from the scorpion Centruroides noxius Hoffmann. Toxicon. 1996;34:843. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(96)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chavanayarn C., Thanongsaksrikul J., Thueng-In K., Bangphoomi K., Sookrung N., Chaicumpa W. Humanized-single domain antibodies (VH/VHH) that bound specifically to Naja kaouthia phospholipase A2 and neutralized the enzymatic activity. Toxins. 2012;4:554–567. doi: 10.3390/toxins4070554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kazemi-Lomedasht F., Yamabhai M., Sabatier J.M., Behdani M., Zareinejad M.R., Shahbazzadeh D. Development of a human scFv antibody targeting the lethal Iranian cobra (Naja oxiana) snake venom. Toxicon. 2019;171:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vital Brazil O., Vieira R.J. Neostigmine in the treatment of snake accidents caused by Micrurus frontalis: Report of two cases. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. S. Paulo. 1996;38:61–67. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46651996000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaeley N., Prasad H., Jr., Singhal A., Subhra Datta S., Galagali S.S. Snakebite Causing Facial and Lingual Tremors: A Case Report. Cureus. 2022;14:e27798. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho W., Gao M., Li F., Li Z., Zhang X.Q., Xu X. Next-Generation Vaccines: Nanoparticle-Mediated DNA and mRNA Delivery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021;10:e2001812. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202001812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brisse M., Vrba S.M., Kirk N., Liang Y., Ly H. Emerging Concepts and Technologies in Vaccine Development. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:583077. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.583077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.World Health Organization (WHO) Annex 5—Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. (WHO Technical Report Series; No. 1004). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kohler G., Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256:495. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pla D., Gutiérrez J.M., Calvete J.J. Second generation snake antivenomics: Comparing immunoaffinity and immunodepletion protocols. Toxicon. 2012;60:688. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.04.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marinetti G.V. The action of phospholipase A on lipoproteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1965;98:554–565. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(65)90152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.da Silva N.M., Arruda E.Z., Murakami Y.L., Moraes R.A., El-Kik C.Z., Tomaz M.A., Fernandes F.F., Oliveira C.Z., Soares A.M., Giglio J.R., et al. Evaluation of three Brazilian antivenom ability to antagonize myonecrosis and hemorrhage induced by Bothrops snake venoms in a mouse model. Toxicon. 2007;50:196. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Melo P.A., Homsi-Brandeburgo M.I., Giglio J.R., Suarez-Kurtz G. Antagonism of the myotoxic effects of Bothrops jararacussu venom and bothropstoxin by polyanions. Toxicon. 1993;31:285. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(93)90146-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Melo P.A., Nascimento M.C., Mors W.B., Suarez-Kurtz G. Inhibition of the myotoxic and hemorrhagic activities of crotalid venoms by Eclipta prostrata (Asteraceae) extracts and constituents. Toxicon. 1994;32:595. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(94)90207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tan K.Y., Tan C.H., Fung S.Y., Tan N.H. Neutralization of the Principal Toxins from the Venoms of Thai Naja kaouthia and Malaysian Hydrophis schistosus: Insights into Toxin-Specific Neutralization by Two Different Antivenoms. Toxins. 2016;8:86. doi: 10.3390/toxins8040086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.