Abstract

Anti-tumor compounds from natural products are being investigated as possible alternatives for cancer chemotherapeutics that have serious adverse effects and tumor resistance. Calystegia silvatica was collected from the north coast of Egypt and extracted via methanol and n-hexane sub-fraction. The biologically active compounds of Calystegia silvatica were identified from the methanol and n-hexane extracts from the leaves and stems of the plant using GC-MS and HPLC. The antitumor properties of both parts of the plant were investigated against cancer and non-cancer cell lines using the MTT assay, and the IC50 in comparison to doxorubicin was calculated. The main compounds identified in the methanol extract were cis-vaccenic acid and trans-13-octadecenoic acid in the leaves and stems, respectively, and phenyl undecane and 3,7,11,15 tetramethyl-2-hexadeca-1-ol in the n-hexane extracts of the leaves and stems, respectively. Both parts of the plant contained fatty acids that have potential antitumor properties. The methanol extract from the stems of C. silvatica showed antitumor properties against HeLa, with an IC50 of 114 ± 5 μg/mL, PC3 with an IC50 of 137 ± 18 μg/mL and MCF7 with an IC50 of 172 ± 15 μg/mL, which were greater than Caco2, which had an IC50 of 353 ± 19 μg/mL, and HepG2, which had an IC50 of 236 ± 17 μg/mL. However, the leaf extract showed weak antitumor properties against all of the studied cancer cell lines (HeLa with an IC50 of 208 ± 13 μg/mL, PC3 with an IC50 of 336 ± 57 μg/mL, MCF7 with an IC50 of 324 ± 17 μg/mL, Caco2 with an IC50 of 682 ± 55 μg/mL and HepG2 with an IC50 of 593 ± 22 μg/mL). Neither part of the plant extract showed any cytotoxicity to the normal cells (WI38). Therefore, C. silvatica stems may potentially be used for the treatment of cervical, prostate and breast cancer.

Keywords: cancers, cytotoxicity, Calystegia Silvatica, phytochemistry

1. Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide. Among surgery and radiation treatment modalities, chemotherapy remains the modality of choice for cancer therapy, particularly in patients with advanced stages of the disease [1,2,3]. However, the use of chemotherapeutic agents for cancer therapy is hindered because of severe long-term side effects and the development of drug resistance caused by inactivation and drug metabolism by different enzymes such as cytochromes P450 [4,5,6,7,8,9]. These factors limit the use of chemotherapeutic agents, making it a significant challenge in cancer therapy. Recent developments have enabled cancer researchers to better explore the potential use of natural products for cancer therapy. Fortunately, several natural products with various chemical structures and different pharmacological activities have shown promise in combating different cancers, these include alkaloids, terpenoids and flavonoids [6,10,11,12,13]. Therefore, collective efforts are needed to discover new therapeutic opportunities for cancer treatment arising from natural products.

The genus Calystegia R.Br., family Convolvulaceae, is represented by only one species—Calystegia silvatica subsp. silvatica—in Egypt. It is found in gardens and orchards in the Mediterranean region, Iran, western Europe and Australia [14]. It has been used for the treatment of fever, urinary tract disorders, constipation and reduced bile production (cholagogue) [15]. Additionally, it has been used for rheumatoid arthritis as an anti-inflammatory and pain killer [16,17], resolvent for pimples [18] and as an anti-tuberculosis treatment [16]. Lipids have reportedly been identified as the primary active components of the latex of C. silvatica [19]. Additionally, C. sepium is a species with strong relations to C. silvatica, which has been used to demonstrate the existence of resin glycosides known as calestegins [20,21]. The aerial parts of C. sepium have been used to isolate seven hexasaccharide resin glycosides, known as calsepins 1–7. Lung cancer cells (A549) showed cytotoxicity when exposed to calysepin 4 [22]. Two resin glycosides, calystegines A and B, were also isolated from the aerial parts of Calystegia sepium. Calystegine B showed an antitumor effect by preventing the assembly of tumor microtubule proteins of cancer cells [20,21]. Three cancer cell lines, including glioma cells (U87-MG), epidermal cell lines (A431) and breast cancer cells (MCF7), have been killed by a methanolic extract comprising the leaves of C. sepium compared to HGF-1 as normal cells [23]. There are no published data regarding the antitumor properties of C. silvatica in the literature; therefore, this is the first investigation of the antitumor effects of this plant against certain cancer cell lines.

2. Results

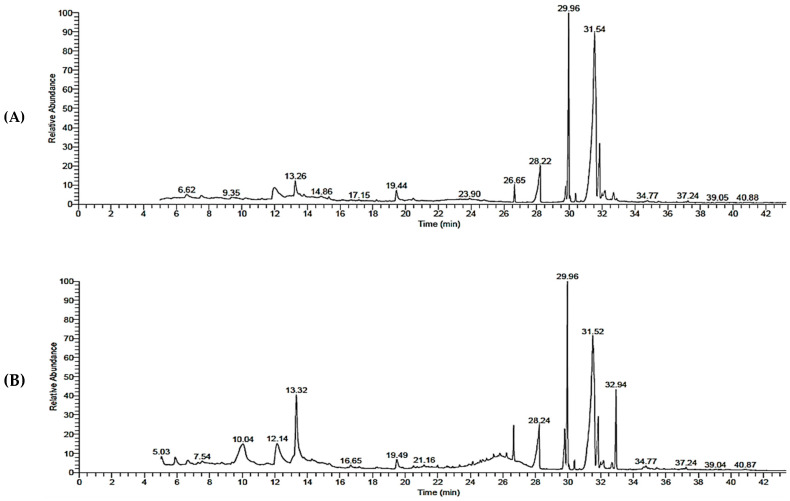

The compounds identified in the methanol extract from the leaves and stems of C. silvatica via gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) revealed fatty acids, phenols, sterols ketones and hydrocarbons. The fatty acids hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester (RA = 2.08% and RA = 3.60%), hexadecanoic acid (RA = 6.26% and RA = 6.30%), 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester (RA = 1.92% and RA = 4.63%), 9-octadecenoic acid, methyl ester (RA = 24.52% and RA = 18.64%), octadecanoic acid, methyl ester (RA = 1.05% and RA = 0.87%) and octadecanoic acid (RA = 10.71% and RA = 6.77%) were found in the leaves and stems, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 1). However, the fatty acids cis-5,8,11,14,17-eicosapentaenoic acid (RA = 0.8%) and cis-vaccenic acid (RA = 38.32%) were found in leaves, and trans-13-octadecenoic acid (RA = 25.06%) was found in stems. The iridoid glycoside proceroside (RA = 0.72%), 9-oxabicyclo [3.3.1]nonan-2-one, 5-hydroxy- (RA = 0.66%), essential oil 3,5-heptadienal, 2-ethylidene-6-methyl (RA = 2.82%), polyacetylene (S,Z)-Heptadeca-1,9-dien-4,6-diyn-3-ol (RA = 0.40%), organic aromatic compound naphthalenes 1,2-dihydro-1,5,8-trimethyl naphthalene (RA = 0.47%) and sesquiterpene alcohol cedran-diol, 8S,13- (RA = 0.35%) were found in the leaves. However, the ketone 2-nonanone, O-methyloxime (RA = 1.16%), 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl (RA = 5.4%), benzofurans derivative 2,3-dihydro-benzofuran (RA = 5.53%), phenol 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol (RA = 8.93%), aromatic compound 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-dione (RA = 1.46%), nitrile derivative tetraacetyl-d-xylonic nitrile (RA = 0.59%), sterol 9,10-secocholesta-5,7,10 (19)-triene-3,24,25-triol (RA = 0.57%) and tributyl citrate (RA = 8.05%) were found in the stems (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Biological compound identification of methanol extract from Calystegia silvatica leaves and stems using GC/MS.

| No. | Leaves | Stems | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | MW | M.F. | Category | Rt | RA% | Rt | RA% | |

| 1 | 2-nonanone, O-methyloxime | 171 | C10H21NO | Ketone | 5.88 | 1.16 | ||

| 2 | 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl | 144 | C6H8O4 | Aromatic organic compound | 10.04 | 5.4 | ||

| 3 | 2,3-dihydro-benzofuran | 120 | C8H8O | Benzofurans derivatives | 12.12 | 5.53 | ||

| 4 | 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol | 150 | C9H10O2 | Phenol aromatic organic compound | 13.32 | 8.93 | ||

| 5 | 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-dione | 180 | C10H12O3 | Aromatic organic compound | 19.49 | 1.46 | ||

| 6 | Tetraacetyl-d-xylonic nitrile | 343 | C14H17NO9 | Aromatic nitro compound | 26.22 | 0.59 | ||

| 7 | Hexadecanoic acid, Methyl ester | 270 | C17H34O2 | Fatty acid methyl ester | 26.65 | 2.08 | 26.65 | 3.60 |

| 8 | Hexadecanoic acid | 256 | C16H32O2 | Fatty acid | 28.21 | 6.26 | 28.23 | 6.30 |

| 9 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl Ester | 294 | C19H34O2 | Fatty acid methyl ester | 29.78 | 1.92 | 29.80 | 4.63 |

| 10 | 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | 296 | C19H36O2 | Fatty acid methyl ester | 29.95 | 24.53 | 29.96 | 18.64 |

| 11 | Octadecanoic acid, Methyl ester | 298 | C19H38O2 | Fatty acid methyl ester | 30.39 | 1.05 | 30.39 | 0.87 |

| 12 | trans-13-Octadecenoic acid | 282 | C18H34O2 | Fatty acid | 31.52 | 25.06 | ||

| 13 | Octadecanoic acid | 284 | C18H36O2 | Fatty acid | 31.85 | 10.71 | 31.85 | 6.77 |

| 14 | 9,10-secocholesta-5,7,10(19) -triene-3,24,25-triol | 416 | C27H44O3 | Sterol | 32.00 | 0.57 | ||

| 15 | Tributyl citrate | 360 | C18H32O7 | Carbonyl compound | 32.49 | 8.05 | ||

| 16 | Proceroside | 548 | C29H40O10 | Iridoid glycoside | 6.62 | 0.72 | ||

| 17 | 9-Oxabicyclo [3.3.1]nonan-2-one, 5-hydroxy | 156 | C8H12O3 | Bicyclo aromatic compound | 7.52 | 0.66 | ||

| 18 | 3,5-Heptadienal, 2-ethylidene-6-methyl | 150 | C10H14O | Essential oil | 13.26 | 2.82 | ||

| 19 | (S,Z)-Heptadeca-1,9-dien-4,6-diyn-3-ol | 244 | C17H24O | Polyacetylene | 13.79 | 0.40 | ||

| 20 | 1,2-dihydro-1,5,8-trimethyl Naphthalene | 172 | C13H16 | Naphthalenes derivatives | 15.31 | 0.47 | ||

| 21 | Cedran-diol, 8S,13 | 238 | C15H26O2 | Sesquiterpene | 20.46 | 0.35 | ||

| 22 | cis-Vaccenic acid | 282 | C18H34O2 | Omega-7 fatty acid | 31.55 | 38.32 | ||

| 23 | cis-5,8,11,14,17-Eicosapentaenoic Acid | 302 | C20H30O2 | Fatty acid | 31.99 | 0.80 | ||

Figure 1.

The spectra of methanol extract from Calystegia silvatica by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry: (A) leaves extract; (B) stems extract.

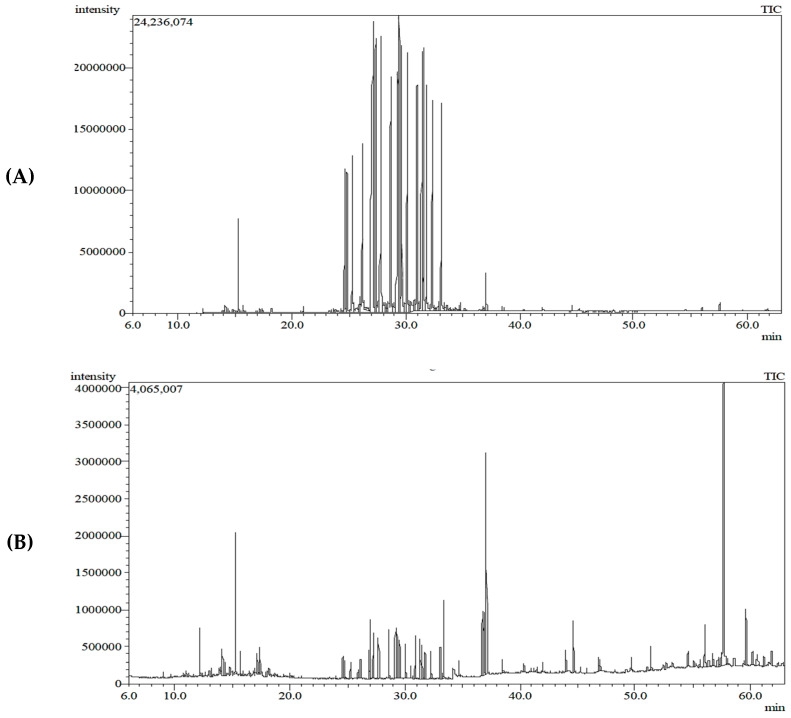

On the other hand, the major identified chemical constituents of lipids via the GC-MS analysis of an n-hexane extract from the leaves and stems of C. silvatica were alkane hydrocarbons undecane (with a relative abundance (RA) of 0.10% and 1.58%, respectively), methyl undecane (RA = 0.29% and RA = 1.85%, respectively), methyl dodecane (RA = 0.10% and RA = 1.99%, respectively), benzenes phenyl undecane (RA = 16.21% and RA = 4.65%, respectively), phenyl decane (RA = 10.11% and RA = 2.72%, respectively) and 2-phenyl tridecane (RA = 4.30% and RA = 1.15%, respectively) (Table 2 and Figure 2). The leaves and stems both contained fatty acids methyl ester 9,12, octadecanoic, methyl ester (RA = 0.10% and RA = 4.12%, respectively). The leaves and stems also contained the diterpene, 3,7,11,15 tetramethyl-2-hexadeca-1-ol (with a relative abundance of 0.53% and 8.10%, respectively), the phthalate ester bis (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (RA = 0.1% and RA = 2.11%, respectively), beta-sitosterol acetate, a sterol, (RA = 0.10% and RA = 2.69%, respectively) and the sterol ergost-25-ene-3,5,6,12-tetrol (3.beta.,5.alpha.,6.beta.,12.beta.) (RA = 0.25% and RA = 0.76%, respectively). However, the octadecenoic acid, 12 hydroxy, methyl ester (RA = 0.44%), 9,12,octadecadienoic acid, 2 hydroxy-1 (hydroxy methyl) ethyl ester (RA = 0.91%) and hexadecenoic acid, 2-hydroxyl-1-(hydroxy methyl) ethyl ester (RA = 1.12%) were the fatty acids found in the stems, but they were not detected in the leaves. Campesterol (RA = 0.79%), stigmasterol (RA = 0.35%), obtusifiol (RA = 0.41%) and cholest-5-en-3-ol, 24-propylidene (RA = 0.40%) were the identified sterols found in stems only. Additionally, 9,19-cyclolanost-24-en-3-ol, (3 beta) (RA = 1.05%), betulinaldehyde (RA = 4.24%) and lanostan-3-ylacetate (RA = 1.1%) were the triterpenes found in the stems. Additionally, other compounds found in the stems were the oxygenated sesquiterpenes longifolenaldehyde (RA = 1.08%) and the diterpene thunbergol (RA = 0.85%). The only compound that was found in the leaves was 7-phenyl eicosane (RA = 0.99%), but it was not detected in the stems (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Biological compound identification of n-hexane extract from Calystegia silvatica leaves and stems using GC/MS.

| No. | Leaves | Stems | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | MW | M.F. | Category | Rt | RA% | Rt | RA% | |

| 1 | Undecane | 156 | C11H24 | Alkane hydrocarbon | 12.16 | 0.10 | 12.15 | 1.58 |

| 2 | Methyl undecane | 170 | C12H26 | Branched alkane hydrocarbon | 14.02 | 0.29 | 14.15 | 1.85 |

| 3 | Methyl dodecane | 184 | C13H28 | Branched alkane hydrocarbon | 17.16 | 0.10 | 17.16 | 1.99 |

| 4 | 2-Phenyl decane | 218 | C16H26 | Benzene | 23.50 | 10.11 | 24.60 | 2.72 |

| 5 | 6-phenyl decane | 232 | C18H3O | Benzene | 25.73 | 0.28 | 20.17 | 1.71 |

| 6 | 7-phenyl eicosane | 358 | C26H46 | Eicosyl benzene | 25.93 | 0.99 | ||

| 7 | Phenyl undecane | 232 | C17H28 | Benzene | 26.78 | 16.21 | 26.91 | 4.65 |

| 8 | 2-phenyl tridecane | 260 | C19H32 | Benzene | 33.15 | 4.30 | 33.07 | 1.15 |

| 9 | Octadecenoic acid, 12 hydroxy, methyl ester | 312 | C19H36O3 | Fatty acid methyl ester | 40.34 | 0.44 | ||

| 10 | 9,12,octadecadienoic acid, 2 hydroxy-1(hydroxy methyl) ethyl ester | 354 | C21H38O4 | Fatty acid ethyl ester | 46.81 | 0.91 | ||

| 11 | Hexadecenoic acid, methyl ester | 270 | C17H34O2 | Fatty acid methyl ester | 33.42 | 1.12 | 33.38 | 2.90 |

| 12 | Nonadec-1-ene | 266 | C19H38 | Essential oil | 34.69 | 0.24 | 34.7 | 0.50 |

| 13 | 9,12, octadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 294 | C19H34O2 | Fatty acid methyl ester | 36.85 | 0.10 | 36.73 | 4.12 |

| 14 | 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-2-hexadeca-1-ol | 296 | C10H40O | Diterpene | 37.10 | 0.53 | 37.08 | 8.10 |

| 15 | Hexadecenoic acid, 2-hydroxyl-1-(hydroxy methyl) ethyl ester | 330 | C19H38O4 | Fatty acid ethyl ester | 43.99 | 1.12 | ||

| 16 | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate | 390 | C24H38O4 | Phthalate ester | 44.62 | 0.1 | 44.6 | 2.11 |

| 17 | Lanostan-3-yl-acetate | 472 | C32H56O2 | Triterpenoid | 51.39 | 1.1 | ||

| 18 | Campesterol | 400 | C28H48O | Sterol | 54.60 | 0.79 | ||

| 19 | Stigmasterol | 454 | C29H48O | Sterol | 55.09 | 0.35 | ||

| 20 | Obtusifiol | 426 | C30H50O | Sterol | 55.66 | 0.41 | ||

| 21 | Beta-sitosterol acetate | 456 | C31H52O2 | Sterol | 56.00 | 0.10 | 56.05 | 2.69 |

| 22 | Cholest-5-en-3-ol, 24-propylidene, (3 beta) | 426 | C30H50O | Sterol | 56.37 | 0.40 | ||

| 23 | Ergost-25-ene-3,5,6,12-tetrol, (3.beta.,5.apha.,6.beta.,12.beta.) | 448 | C28H48O | Sterol | 57.6 | 0.25 | 56.74 | 0.76 |

| 24 | 9,19-Cyclolanost-24-en-3-ol, (3.beta.) | 426 | C30H50O | Triterpene | 57.45 | 1.05 | ||

| 25 | Betulinaldehyde | 440 | C30H48O2 | Triterpenes | 59.64 | 4.24 | ||

| 26 | Longifolenaldehyde | 220 | C15H24O | Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 60.19 | 1.08 | ||

| 27 | Thunbergol | 290 | C20H34O | Diterpene | 60.62 | 0.85 | ||

Figure 2.

The spectra of n-hexane extract from Calystegia silvatica by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry: (A) leaves extract; (B) stems extract.

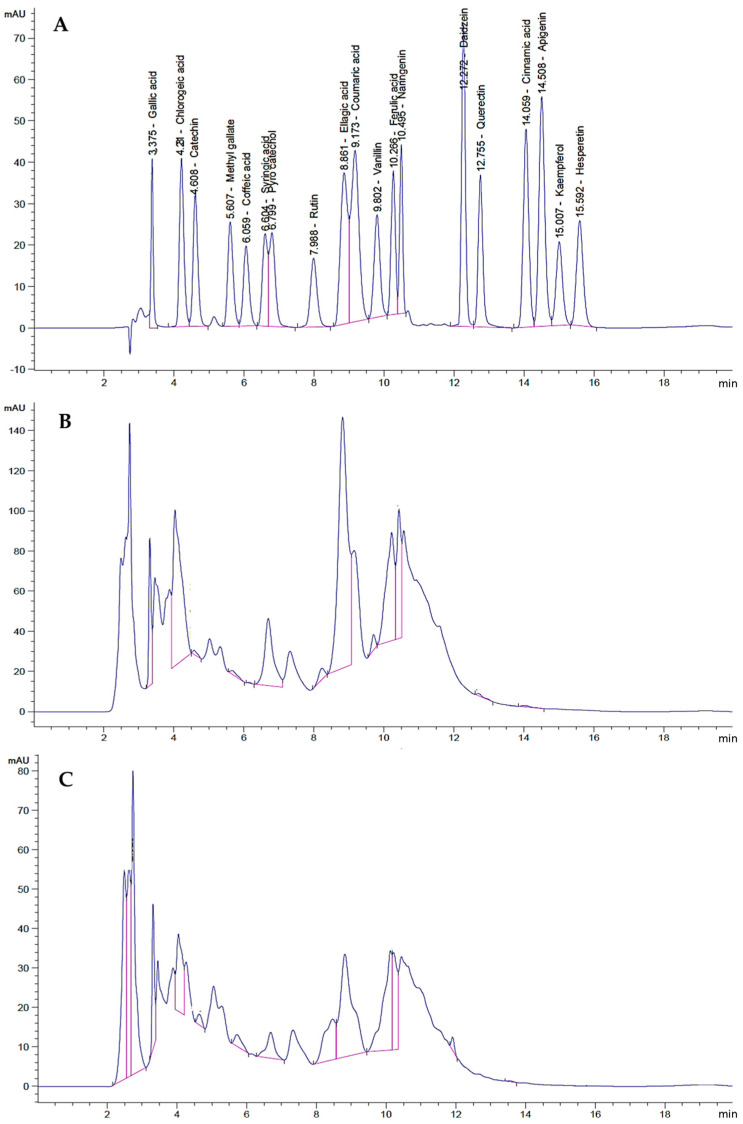

The total phenolic contents of the leaves and stems of C. silvatica were 21.18 mg and 17.30 mg GAE/g of dry weight (DW), respectively, and the total flavonoids were 7.10 mg and 12.45 mg CE/g DW, respectively. The HPLC was used to identify and quantify the phenolic compounds that exist in the methanolic extract from the leaves and stems of C. silvatica. (Table 3). As a result, phenolic acids, polyphenols, tannins, flavanones, flavonoids, isoflavone and carboxylic acids were identified in both parts of the plant. The leaves and stems contained the phenolic acid gallic acid, at a concentration of 1.05 mg/100 g dry weight (DW) and 0.5 mg/100 g DW, respectively, and the phenolic acid ferulic acid, at a concentration of 0.28 mg/100 g DW and 0.60 mg/100 g DW, respectively. The polyphenols found in the leaves and stems were catechin, at a concentration of 0.19 mg/100 g DW and 0.24 mg/100 g DW, respectively, and caffeic acid, at a concentration of 0.1 mg/100 g DW and 0.003 mg/100 g DW, respectively. Additionally, the phenolic compounds found in the leaves and stems were pyrocatechol, at a concentration of 3.14 mg/100 g DW and 0.36 mg/100 g DW, respectively, and coumaric acid, at a concentration of 2.40 mg/100 g DW and 0.19 mg/100 g DW, respectively. The phenylacrylate polyphenol compound chlorogenic acid was found in the leaves and stems at a concentration of 1.78 mg/100 g D.W and 0.42 mg/100 g DW, respectively. Additionally, the methyl gallate (gallate ester) was found in the leaves and stems at a concentration of 0.06 mg/100 g DW and 0.10 mg/100 g DW, respectively. The leaves and stems also contained tannin ellagic acid at a concentration of 0.69 mg/100 g DW and 0.21 mg/100 g DW, respectively. The benzaldehyde vanillin was found to have a concentration of 0.07 mg/100 g DW and 0.02 mg/100 g DW in the leaves and stems, respectively. The flavanone naringenin was found in the leaves and stems at a concentration of 0.67 mg/100 g DW and 0.08 mg/100 g DW, respectively. The monocarboxylic acid cinnamic acid was found to have the lowest concentration in the leaves and stems (0.01 mg/100 g DW and 0.001 mg/100 g DW, respectively), as compared to other identified phenolic compounds. However, the flavonoid quercetin was found in the leaves at a concentration of 0.05 mg/100 g DW, and the isoflavone daidzein was found in the stems at a concentration of 0.05 mg/100 g DW. Other phenolic compounds—syringic acid, apigenin, kaempferol and hesperetin—were not detected in the leaves or stems (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Phenolic compound identification of methanol extract from Calystegia silvatica leaves and stems via HPLC.

| Leaves | Stems | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Compounds | MW | M.F. | Category | Rt | mg/100 g D. W |

Rt | mg/100 g D. W |

| 1 | Gallic acid | 170 | C7H6O5 | Phenolic acids | 3.31 | 1.05 | 3.31 | 0.50 |

| 2 | Chlorogenic acid | 354 | C16H18O9 | Phenylacrylate polyphenol compound | 4.03 | 1.78 | 4.04 | 0.42 |

| 3 | Catechin | 290 | C15H14O6 | Polyphenol | 4.57 | 0.19 | 4.63 | 0.24 |

| 4 | Methyl gallate | 184 | C8H8O5 | Gallate ester | 5.66 | 0.06 | 5.71 | 0.10 |

| 5 | Caffeic acid | 180 | C9H8O4 | Polyphenol | 6.14 | 0.01 | 6.14 | 0.003 |

| 6 | Pyrocatechol | 110 | C6H6O2 | Phenolic compounds | 6.69 | 3.14 | 6.69 | 0.36 |

| 7 | Ellagic acid | 302 | C14H6O8 | Tannins | 8.23 | 0.69 | 8.46 | 0.21 |

| 8 | Coumaric acid | 164 | C9H8O3 | Phenolic compound | 8.82 | 2.40 | 8.81 | 0.19 |

| 9 | Vanillin | 152 | C8H8O3 | Benzaldehydes | 9.71 | 0.07 | 9.69 | 0.02 |

| 10 | Ferulic acid | 194 | C10H10O4 | Phenolic acid | 10.22 | 0.28 | 10.21 | 0.06 |

| 11 | Naringenin | 580.5 | C27H32O14 | Flavanones | 10.43 | 0.67 | 10.44 | 0.08 |

| 12 | Quercetin | 302 | C15H10O7 | Flavonoid | 12.72 | 0.05 | ||

| Daidzein | 254 | C15H10O4 | Isoflavone | 11.905 | 0.05 | |||

| 13 | Cinnamic acid | 148 | C9H8O2 | Monocarboxylic acid | 14.01 | 0.01 | 13.51 | 0.001 |

Figure 3.

The HPLC chromatogram of methanol extract from Calystegia silvatica: (A) standard chromatogram; (B) leaves chromatogram; (C) stems chromatogram.

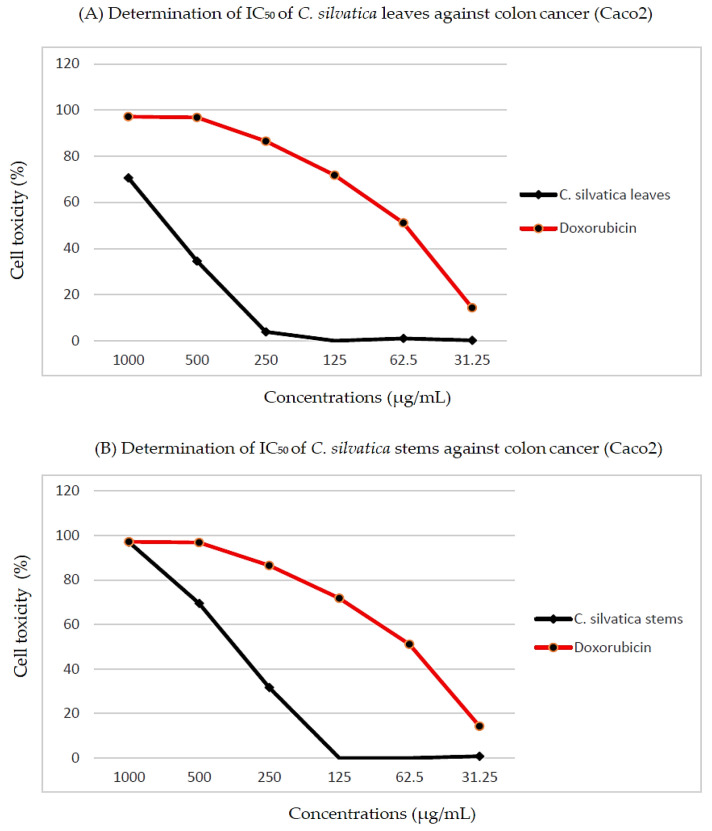

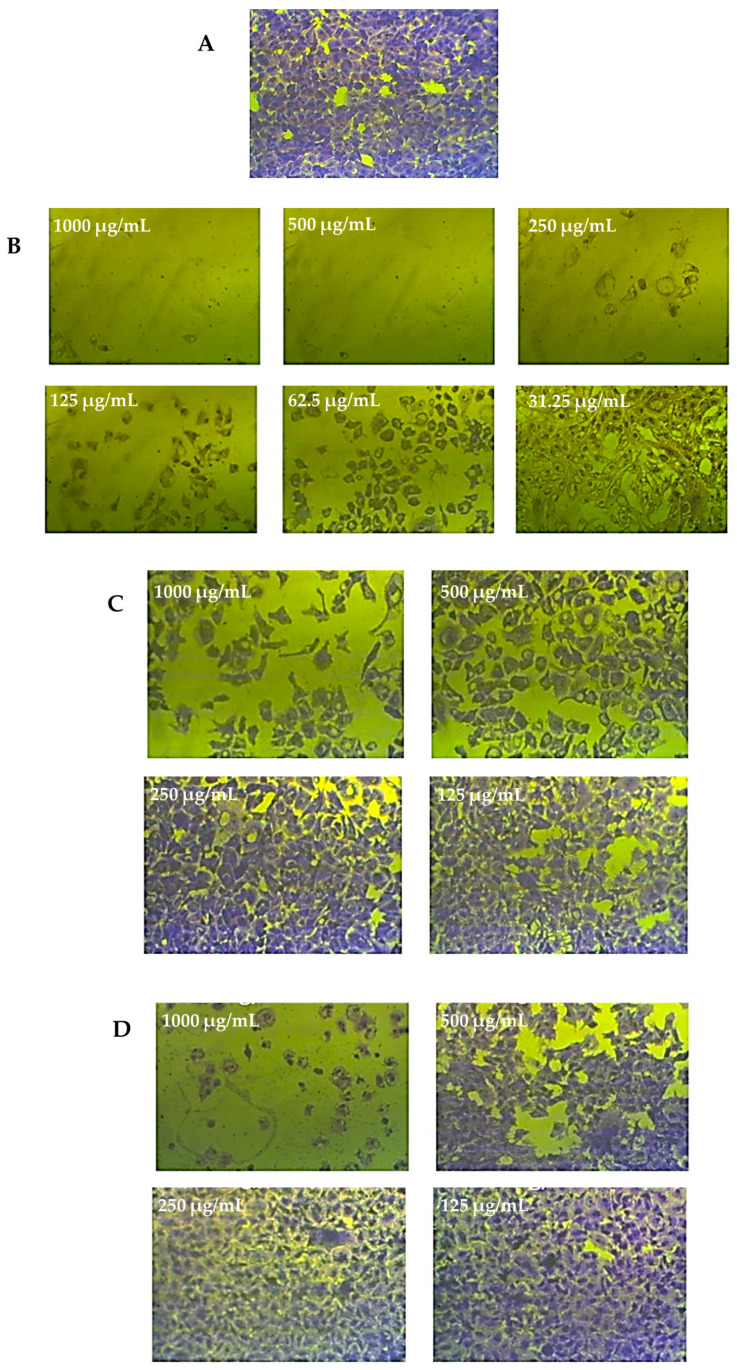

The percentage of cytotoxicity was represented as [cell viability percentage – 100] and plotted on the Y-axis; the concentration of the extracts from leaves and stems was plotted on the X-axis to calculate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50). For example, the IC50 of the leaves extract against colon cancer was 682 ± 55 μg/mL, and it was 353 ± 19 μg/mL for the stems extract (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Determination of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of (A) C. silvatica leaves extract and (B) C. silvatica stems extract against colon cancer (Caco2).

The antitumor properties of C. silvatica leaves and stems against colon cancer (Caco2), cervical cancer (HeLa), prostate cancer (PC3), breast cancer (MCF7), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) and normal human fetal lung fibroblast (WI38) cell lines were studied using an MTT assay. Dunnett’s test was used to compare the calculated IC50 values of the leaves and stems extracts to the positive control, doxorubicin. Based on the NCI criteria, the methanol extract from the leaves and stems exhibited different cytotoxicities against all of the cancer cell lines (Table 4). The antitumor properties of C. silvatica stems against cervical cancer (HeLa) (114 ± 5 μg/mL), prostate cancer (PC3) (137 ± 18 μg/mL) and breast cancer (MCF7) (172 ± 17 μg/mL) were moderate compared to doxorubicin. However, the antitumor properties of stems against colon cancer (CaCo2) (353 ± 19 μg/mL) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) (236 ± 17 μg/mL) were weak compared to the positive control. In contrast, the cytotoxicities of leaves on cervical cancer (HeLa) (IC50 = 208 ± 13 μg/mL), prostate cancer (PC3) (IC50 = 336 ± 57 μg/mL) and breast cancer (MCF7) (IC50 = 324 ± 17 μg/mL) were weak compared to doxorubicin. However, the leaves did not show any antitumor properties against colon cancer (Caco2) (IC50 = 682 ± 55 μg/mL) or hepatocellular carcinoma (IC50 = 593 ± 33 μg/mL). Interestingly, neither the extract from leaves nor from stems showed any cytotoxicity to normal human fetal lung fibroblast (WI38) with an IC50 of 543 ± 33 μg/mL and 408 ± 4 μg/mL, respectively, compared to the positive control. The selectivity index of the methanol extract from C. silvatica leaves and stems was estimated as described above. Therefore, no cytotoxic selectivity was shown for the leaves extract from C. silvatica in any of the studied cancer cell lines (values < 3). However, the stems extract showed cytotoxic selectivity in HeLa (3.5) and prostate cancer (3) but not in colon cancer (1.7), breast cancer (1.1) or hepatocellular carcinoma (2.3) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Antitumor effects of Calystegia silvatica methanol extract on cancer and normal cell lines.

| a IC50 (µg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Leaves | Stems | Doxorubicin (Positive Control) |

| b CaCo2 | 682 ± 55 *** | 353 ± 19 *** | 70.1 ± 1 |

| c HeLa | 208 ± 13 *** | 114 ± 5 *** | 40 ± 2 |

| d PC3 | 336 ± 57 *** | 137 ± 18 * | 38 ± 2 |

| e MCF7 | 324 ± 17 *** | 172 ± 15 *** | 36 ± 6 |

| f HepG2 | 593 ± 22 *** | 236 ± 17 *** | 44 ± 3 |

| g WI38 | 543 ± 33 *** | 408 ± 4 *** | 51 ± 4 |

a IC50: The half-maximal inhibitory concentration, b colon cancer (Caco2), c cervical cancer (HeLa), d prostate cancer (PC3), e breast cancer (MCF7), f hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) and g normal human fetal lung fibroblast (WI38). The findings are shown as mean ± standard deviation. * p = 0.05, ** p = 0.001 and *** p = 0.0001 show significant changes compared to a positive control. The Calystegia silvatica stems and leaves extracts and doxorubicin were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), then Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test.

Table 5.

Selectivity index values of Calystegia silvatica methanol extract from leaves and stems for Caco2, HeLa, PC3, MCF7 and HepG2 cancer cell lines.

| a SI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extract | b Caco2 | c HeLa | d PC3 | e MCF7 | f HepG2 |

| Leaves | 0.8 | 2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| Stem | 1.1 | 3.5 | 3 | 2.3 | 1.7 |

| Doxorubicin | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

a SI: selectivity index, b colon cancer (Caco2), c cervical cancer (HeLa), d prostate cancer (PC3), e breast cancer (MCF7) and f hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2). Compounds with values higher than 3 are more active against cancerous cells than non-cancerous (WI38) cells.

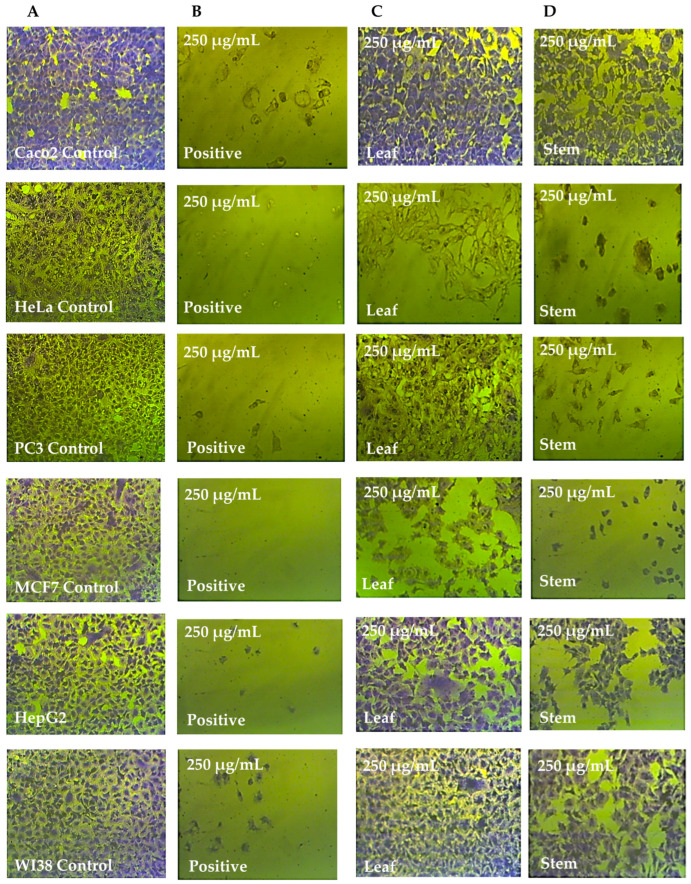

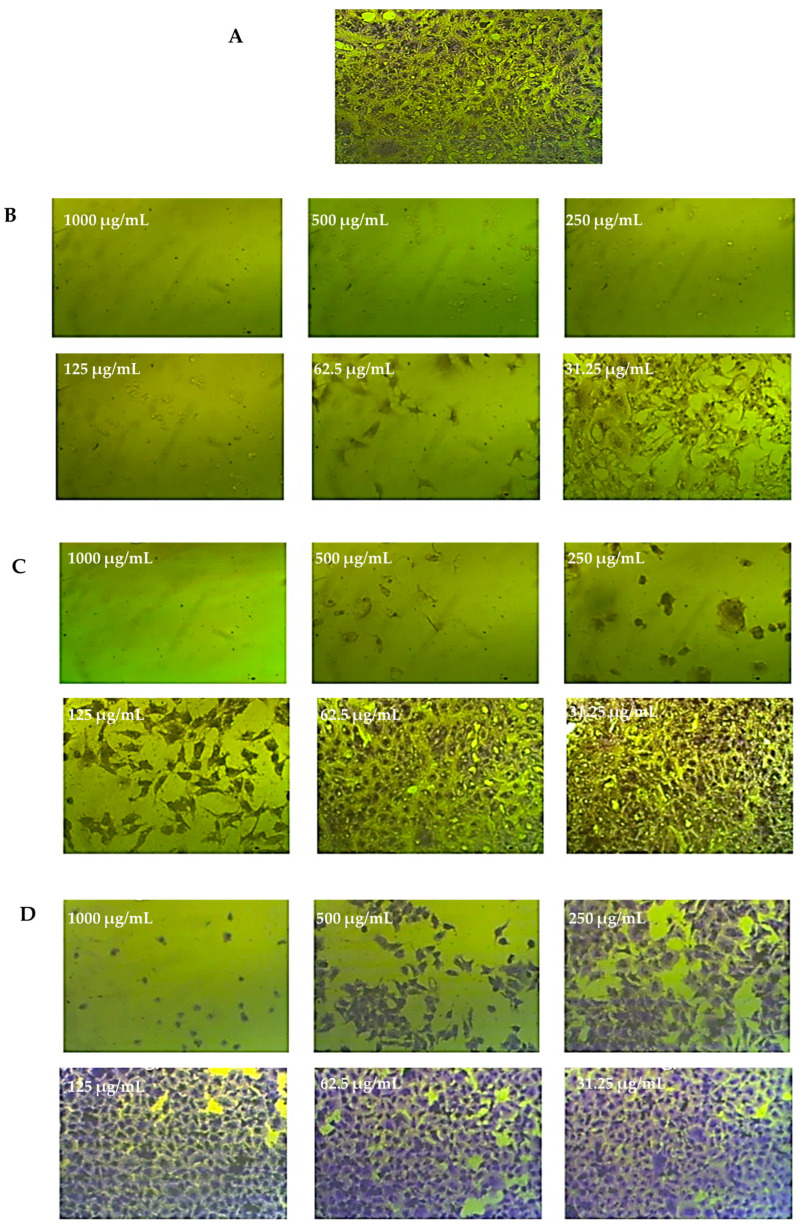

The different cell lines were treated for 72 h with 250 μg/mL of extract from C. silvatica leaves and stems and were microscopically examined. The methanol extract from the leaves of C. silvatica caused a small shrinkage to HeLa and MCF7 cell lines only, while the stems extract caused a significant shrinkage to HeLa, PC3 and MCF7 cancer cell lines, which became rounded and detached. However, Caco2 and HepG2 did not show any change in morphology compared to untreated control cells, and WI38 cell lines did not exhibit any change in morphology when treated with either the leaves or stems of C. silvatica compared to their control cells (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Anticancer effects of Calystegia silvatica leaves and stems extracts in methanol on cancer cell lines: (A) complete monolayer sheets are seen in all of the cancer cell lines that have not been treated; (B) doxorubicin treatment results in rounded and shrunk cells in all of the cancer cell lines; (C) shrunk cells are observed in HeLa and MCF7 cell lines treated with the extract from Calystegia silvatica leaves; however, no morphological changes are observed in Caco2, HepG2 and WI38; (D) the extract from Calystegia silvatica stems used to treat HeLa, PC3, MCF7 and HepG2 cancer cell lines revealed significantly rounded and shrunk cells; however, small rounded and shrunk cells are observed in Caco2 and W138.

Figure 6.

An example of the moderate anticancer effect of the stems extract from Calystegia sylvatica against cervical cancer cell lines (HeLa): (A) complete monolayer sheets of cervical cancer cells (HeLa) that have not been treated; (B) the effect of doxorubicin treatment at different concentrations; (C) the effect of the stems extract from C. sylvatica against HeLa cell lines at different concentrations; (D) the effect of the stems extract from C. sylvatica against normal human fetal lung fibroblast (WI38).

Figure 7.

An example of the weak anticancer effect of the leaves extract from Calystegia sylvatica against colon cancer cell lines (Caco2): (A) complete monolayer sheets of colon cancer cell lines (Caco2) that have not been treated; (B) the effect of doxorubicin treatment at different concentrations; (C) the effect of the leaves extract from C. sylvatica against Caco2 cell lines at different concentrations; (D) the effect of the leaves extract from C. sylvatica against normal human fetal lung fibroblast (WI38) at different concentrations.

3. Discussion

The GC-MS results of the methanol extract from the leaves and stems of C. silvatica revealed the existence of potential antitumor composites. For example, the 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5- dihydroxy-6-methyl found in the stems has been reported to possess an antiproliferative effect [24]. The stems also contained benzofuran derivatives 2,3-dihydro-benzofuran, which has also been reported to have antitumor properties [25]. Additionally, the tetra acetyl-d-xylonic nitrile detected in stems was found to have antitumor and antioxidant properties [26]. The two fatty acids, hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester and hexadecanoic acid, have not been evaluated for their antitumor properties; however, they have been reported to display antioxidant activity [27,28]. However, the fatty acids 9,12-octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester and 9-octadecenoic acid, methyl esters, have been reported to have antitumor and antioxidant properties [29,30], and octadecanoic acid, methyl ester and octadecanoic acid and cis-5,8,11,14,17-eicosapentaenoic acid have been reported to have antitumor properties [31,32]. Interestingly, these compounds were found in significant amounts in the methanol extract from the leaves and stems of C. silvatica, except cis-5,8,11,14,17-eicosapentaenoic acid, which was only detected in the leaves. cis-Vaccenic acid and trans-13-octadecenoic acid were also reported to have antitumor properties [33,34]. Importantly, cis-vaccenic (RA = 38.32%) and trans-13-octadecenoic acid (RA = 25.06%) (Table 1 and Figure 1) were found in the leaves and stems, respectively, in a greater amount than other detected compounds of methanol extract from C. silvatica (Table 1 and Figure 1). The polyacetylene (S,Z)-heptadeca-1,9-dien-4,6-diyn-3-ol has been reported to have antitumor properties [35]. The phenol compound, 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol, has not been evaluated for antitumor properties; however, it has been reported to have anti-inflammatory properties [36]. Additionally, the organic compound (vitamin D with 3 hydroxyl (OH) groups) 9,10-secocholesta-5,7,10(19)-triene-3,24,25-triol has not been evaluated for its antitumor properties, though it has been reported to have antibacterial properties [37]. Moreover, the sesquiterpene alcohol cedran-diol, 8S,13- has not been reported to have antitumor properties; however, it has been reported to have antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties [38]. The ketone 2-nonanone, O-methyloxime has not been evaluated for biological activities until now. The 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-dione and tributyl citrate have also not been evaluated for biological activities. Additionally, the steroid proceroside, essential oil 3,5-Heptadienal, 2-ethylidene-6-methyl, the naphthalene derivative 1,2-dihydro-1,5,8-trimethyl naphthalene and 9-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-2-one, 5-hydroxy- have not been evaluated for biological activities until now.

On the other hand, the identified compounds of the n-hexane extract from the leaves and stems of C. silvatica were reported to have antitumor properties. The diterpene 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl-2- hexadeca-1-ol (RA = 8.10%) has been reported to have antitumor properties [39], which has a higher concentration in the stems than leaves and among other compounds identified in stems. Additionally, the phthalate ester bis (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (RA = 2.11%) has been reported to have antitumor and antioxidant properties [40], and it has a higher concentration in the stems than in leaves. Additionally, campesterol [41], stigmasterol [42], beta-sitosterol acetate [43,44] and obtusifoliol [45] are sterols that are found in the stem and have been reported to have antitumor properties. Betulinaldehyd is a triterpene also found in the stems and has been reported to possess antitumor properties [46]. Importantly, these detected antitumor compounds were found only in the stems of an n-hexane fraction of C. silvatica (Table 2). Therefore, this may explain the greater antitumor effect of stems against cervical cancer (IC50 = 114 ± 5 μg/mL), prostate cancer (IC50 = 137 ± 18 μg/mL) and breast cancer (IC50 = 172 ± 15 μg/mL) compared to leaves that showed an antitumor effect against cervical cancer (IC50 = 208 ± 13 μg/mL), prostate cancer (IC50 = 336 ± 57 μg/mL) and breast cancer (IC50 = 324 ± 17 μg/mL) (Table 3 and Figure 4). Additionally, the stems extract showed SI values of 3 and 3.5 against HeLa and PC3, respectively, this may indicate that the antitumor properties of stems against cancerous cells were greater than non-cancerous (WI38) cells (Table 4). However, thunbergol is an identified diterpene that has not been evaluated for antitumor properties, but it has been reported to have antimicrobial properties [47]. Additionally, the ergost-25-ene-3,5,6,12-tetrol (3.beta.,5.alpha.,6.beta.,12.beta.) and cholest-5-en-3-ol, 24-propylidene, (3 beta) are identified sterols that have not been evaluated for antitumor properties; however, they have been reported to have antioxidant properties [48] and antimicrobial properties [49], respectively. Additionally, the triterpene 9,19-Cyclolanost-24-en-3-ol, (3.beta.) has not been evaluated for antitumor properties; however, it has been reported to have antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [50] (Table 2 and Figure 2). The 9,12,octadecadienoic acid, 2 hydroxy-1 (hydroxy methyl) ethyl ester and hexadecenoic acid, 2-hydroxyl-1-(hydroxy methyl) ethyl ester are identified fatty acids of n-hexane extract that have not been evaluated for antitumor properties; however, they have been reported to have antioxidant properties [51,52]. The nonadec-1-ene is an essential oil that has not been evaluated for antitumor properties; however, it has been reported to display antimicrobial and antioxidant activity [53]. The alkane hydrocarbons methyl undecane, methyl dodecane and the benzenes 2-phenyl decane, 6-phenyl decane, 7-phenyl eicosane, phenyl undecane and 2-phenyl tridecane have not been evaluated for biological activities; however, methyl undecane has been reported to have anti-inflammatory properties [54]. Additionally, some compounds identified in the n-hexane extract that have not been evaluated for biological activities until now are the fatty acid octadecenoic acid, 12 hydroxy, methyl ester, the triterpenoid lanostan-3-ylacetate and the oxygenated sesquiterpenes longifolenaldehyde.

The HPLC analysis for phenolic compounds in the methanol extract revealed that the leaves and stems extracts contained several phenolic and flavonoid compounds that could potentially contribute to the antitumor effect of C. silvatica against the studied cancer cell lines. Gallic acid is an identified phenolic acid that has been reported to have an antitumor effect [55]. Additionally, chlorogenic acid is a phenylacrylate polyphenol compound that has been reported to have antitumor properties [56]. The identified polyphenols with antitumor properties in C. silvatica extract are catechin [57] and caffeic acid [58]. Methyl gallate (gallate ester) has also been reported to have antitumor properties [59]. The identified phenolic compounds with antitumor properties are coumaric acid [60], ferulic acid [61] and pyrocatechol [62]. The vanillin is an identified benzaldehyde that has been reported to possess antitumor properties [63]. Additionally, ellagic acid is a tannin and has been reported to have antitumor properties [64]. Naringenin is a flavanone that has been reported to have antitumor properties [65]. Additionally, the flavonoid quercetin found in the leaves has been reported to have antitumor properties [38], and the isoflavone daidzein found in the stems has also been reported to have antitumor properties [66]. The identified monocarboxylic acid cinnamic acid has been reported to have antitumor properties [67].

C. sepium, which has a close affiliation to C. silvatica, showed an antitumor effect against breast cancer cells (MCF7), epidermal cell line (A431) and glioma cell line (U87-MG) compared to HGF-1 as normal cells [23]. These findings are in line with our MTT assay results in which the methanol extract from C. silvatica stems demonstrated an antitumor effect against breast cancer cell lines (MCF7) without cytotoxicity to the normal human fetal lung fibroblast (WI38). This study showed that stem extracts of C. silvatica have a higher antitumor effect than leaf extracts against most of the tested cancer cells without affecting the non-cancer cells. This may be due to the number of compounds that have antitumor properties found in the stems more than in the leaves. Therefore, the extract from the stems of C. silvatica may have potential antitumor properties against cervical, prostate and breast cancer but not against colon cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma; however, the extract from the leaves has weak antitumor effects.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

Aerial parts of C. silvatica in the flowering stage were collected from the Al Alamein region, which is about 101 km from Alexandria, Egypt. Dr. Iman Al-Gohary from the Desert Research Centre (DRC), Cairo, Egypt, identified the samples. Voucher specimens were placed in the Center’s Herbarium (CAIH-0042R). Both parts of the plant were washed using tap water and dried for 10 days at 25 °C in a ventilated room in the shade and were subsequently powdered separately [68].

4.2. Extraction and Fractionation

4.2.1. Methanol Extract Preparation

Two hundred grams of the air-dried powdered plant leaves and stems was extracted using the cold percolation technique. The extract was then placed on an orbital shaker for 72 h at 25 °C using 500 mL of 70% methanol three times (500 mL each time). A Buchner funnel was used to filtrate the methanol extracts. Then, the methanol was completely eliminated from the methanol extracts via concentration under reduced pressure at 40 °C and a rotary evaporator. In a dissector, the residues were dried to provide dry weights of 24.68 g/100 g for the leaves and 14.93 g/100 g for the stems. The bioactive components were identified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of the crude methanol extracts [68,69].

4.2.2. GC-MS Analysis for the Methanol Extract

A Thermo Scientific TRACE 1310 gas chromatograph was coupled to an ISQLT single quadrupole mass spectrometer. The ionization voltage was 70 eV, the ionization mode was EI and the column was DB5-MS, 30 m, 0.25 mm ID (J & W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA). The temperature program was as follows: 40 °C for 3 min, 280 °C for 5 min, 5 °C/min to 290 °C (held for 1 min) and then static at 7.5 °C/min. The injector temperature was 200 °C, the detector was 300 °C and the flow rate of the carrier gas, helium, was 1 mL/min. The WILEY and NIST Mass Spectral Databases were employed as search libraries [68].

4.2.3. n-Hexane Sub-Fraction Extract Preparation

The lyophilized crudes of the methanol extract from 2.5 g of leaves and stems were redissolved in 250 mL of distilled water. Then, a separatory funnel was used to partition the redissolved crude with n-hexane for 24 h. Utilizing a rotary evaporator at 40 °C, the n-hexane sub-fraction was condensed to dryness at reduced pressures. The dried fractions of leaves and stems were 1.3 g and 0.86 g, respectively, and they were analyzed using GC-MS [11,69].

4.2.4. GC-MS Analysis for n-Hexane Sub-Fraction Extract

The Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 (Tokyo, Japan) is equipped with a split/splitless injector and Rtx-5MS fused bonded column (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 m film thickness) from Restek (Bellefonte, PA, USA), which were utilized to record the mass spectra. The starting column temperature was raised to 300 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min for 5 min and was then maintained there for 2 min (isothermal). The temperature of the injector was 250 °C. The helium carrier gas flowed at a rate of 1.41 mL/min. All mass spectra were recorded using the following settings: 60 mA filament emission current, 70 eV ionization voltage and a 200 °C ion source, and the split mode injections of samples that were diluted (1% v/v) were carried out (split ratio 1:15) [69].

4.2.5. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Determination

The Folin–Ciocalteu method was used to quantify the phenolic compounds [11,70]. A volume of 0.25 mL of the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (2 N) was added to 0.2 mL of the 80% methanolic extract in a volumetric flask (10 mL). Saturated sodium carbonate (1 mL) (20% in distilled water) was added after three minutes, and the volume was completed with distilled water. A Unicam UV-visible Spectrometer was used to measure the absorbance of blue color after 1 h at λmax 725 nm against a blank (distilled water). Gallic acid was used to obtain a standard calibration curve. The results were represented as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry weight (D.W) [11,70].

An aluminum chloride colorimetric method was used to quantify the total flavonoid content [11,70]. Distilled water with a volume of 1.25 mL was used to dilute the methanolic extract (0.25 mL). A 5% NaNO2 solution was then added to the mixture in a volume of 75 µL. After 6 min, 150 µL of a 10% AlCl3.6H2O solution was added, and the combination was left to stand for an additional 5 min. Then, 0.5 mL of a 1 M NaOH solution was added, and the mixture was then completed with 2.5 mL of distilled water. The absorbance was measured at λmax 510 nm against the blank (distilled water). The (+)-catechin was used to obtain a standard calibration curve. The results were represented as milligrams of catechin equivalents (CE) per gram of dry weight.

4.2.6. HPLC Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

Standards

HPLC reagents: methanol and acetonitrile (HPLC grade) were purchased from SDS (Peypin, France), and trifluoroacetic acid was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) for phenolic compound analysis. Milli- Q (Millipore, MA, USA) was used to provide distilled water. Phenolic standards: gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, catechin, methyl gallate, caffeic acid, syringic acid, pyrocatechol, rutin, ellagic acid, coumaric acid, vanillin, ferulic acid, naringenin, daidzein, quercetin, cinnamic acid, apigenin, kaempferol and hesperetin were obtained from Sigma Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All phenolic standards had a 98% purity level.

Quantitative analysis of phenolic compounds via HPLC

The previously prepared methanolic extract from the leaves and stems of C. silvatica. (200 mg) was dissolved in HPLC-grade acetonitrile (2 mL). An Agilent 1260 series reverse-phase HPLC apparatus (Agilent, USA) was used for phenolic compound analysis. The separation of phenolic compounds was performed using an Eclipse C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm i.d., 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of water (A) and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 0.9 mL/min. The mobile phase was programmed consecutively in a linear gradient as follows: 0 min (82% A); 0–5 min (80% A); 5–8 min (60% A); 8–12 min (60% A); 12–15 min (82% A); 15–16 min (82% A); 16–20 min (82%A). The samples were monitored at 280 nm using a multi-wavelength detector. The injection volume was 5 μL for each of the sample solutions. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. Standard flavonoids and phenolic acids were prepared as 10 mg/50 mL stock solution in methanol. They were then diluted to reach working concentrations (20–40 µg/mL) and injected into HPLC. The quantities of the detected compounds were expressed as µg/g, and the peak area of the external standards was employed to quantify the phenolic compounds in the methanol extracts from the leaves and stems [11,70].

4.3. Antitumor Properties Evaluation

The cell lines laboratory at Vacsera, Dokkey, Giza, Egypt provided colon cancer (Caco2), cervical cancer (HeLa), prostate cancer (PC3), breast cancer (MCF7), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) and normal human fetal lung fibroblast (WI38).

4.3.1. Culturing

The sterility of the process was maintained using a laminar airflow cabinet. The Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI 1640) was used to sustain the cell culture. A mixture of one percent of antibiotic and antimycotic (10,000 μg/mL streptomycin sulphate, 25 μg/mL amphotericin B and 10,000 U/mL potassium penicillin) and 1% L-glutamine were added to the medium. The 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum was used to supplement the medium [70].

4.3.2. MTT Assay

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was employed to measure cytotoxicity. A purple formazan was created from the yellow MTT via a mitochondrial reduction [70]. For inoculation, a 96-well microplate was filled with 1 × 105 cells per well in 100 µL of Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI 1640). Conditions of 5% CO2, 37 °C and 95% humidity were used to incubate the microplate for 24 h to produce a completely formed monolayer sheet. After the cells formed a confluent layer, the growth media was decanted from 96-well microplates. Dimethyl sulfoxide (0.1%) was used to dissolve the methanol extract from the leaves and stems. The dissolved extract was serially diluted using a growth medium to achieve final concentrations of are: 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 and 1000 µg/mL [70]. Confluent cell monolayers were injected with 0.1 mL of the extract at each concentration using a multichannel pipette, and then they were dispersed throughout the 96 wells. The cells that were treated with the extracts were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. For each extract concentration, three wells were used. Control cells were incubated without the extracts from the leaves and stems. Phosphate-buffered saline (Bio Basic Canada Inc., Markham, ON, Canada) was used to dissolve the MTT powder to provide a solution with a 5 mg/mL concentration. Each well received 20 µL of the MTT solution following the completion of the incubation period. A shaker (MPS-1, Biosan, London, UK) was used for mixing, which was performed at 150 rpm for 5 min. The 96-well microplate was then kept for 4 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. A metabolic byproduct of the MTT called formazan was resuspended in 200 µL of DMSO and aggressively shaken for five minutes at 150 rpm. The optical density at 560 nm was determined using a microplate reader. A background reference wavelength of 620 nm was used to adjust the results. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

4.3.3. Determination of IC50 Values

Using GraphPad Prism version 7 (GraphPad software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), the values of the varying concentrations of the IC50 of the methanol extract from C. silvatica and doxorubicin (as a positive control) against colon cancer (Caco2), cervical cancer (HeLa), prostate cancer (PC3), breast cancer (MCF7), hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) and normal human fetal lung fibroblast (WI38) cell lines were computed. Equation (1) was used to determine the percentage of growth inhibition as follows [70]:

| Growth Inhibition (%) = 100 − (mean OD of individual test group/mean OD of control group) × 100 | (1) |

4.3.4. Criteria for Antitumor Effect Levels

The level of cytotoxicity of the methanol extract from C. silvatica was categorized using the Geran protocol and the guidelines of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the USA as follows: highly cytotoxic substances (IC50 ≤ 20 µg/mL), moderately cytotoxic substances (IC50 of 21–200 µg/mL), weakly cytotoxic substances (IC50 of 201–500 µg/mL) and non-cytotoxic substances (IC50 > 501 µg/mL) [71,72].

4.3.5. Selectivity Index

The ratio of a plant extract’s IC50 value in a non-cancer cell line (WI38) to its IC50 value in each cancer cell line is known as the selectivity index. SI values below 3 indicate that the extract is not selective to non-cancer cells [71]. The selectivity indices of the methanol extract were determined using the following Equation (2):

| Selectivity Index = (IC50 of non-cancer cell line (WI38))/(IC50 of a cancer cell line) | (2) |

4.3.6. Microscope

The morphological structures of cell lines were examined using a Nikon 11,881 inverted microscope with objective 8× at various methanol C. silvatica extract concentrations.

5. Conclusions

The methanolic and n-hexane extracts from the leaves and stems of C. silvatica contained a diverse variety of phytochemicals that were identified by GC/MS and HPLC. Most of these phytochemicals had antitumor properties. Most of the phytochemicals that possessed antitumor properties were greater in the stems than in the leaves. Therefore, the antitumor effect of the stems of C. silvatica on cervical cancer (HeLa), prostate cancer (PC3), breast cancer, colon cancer (Caco2) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) was greater than that of the leaves, which showed a weak antitumor effect against all of the studied cancer cell lines. The normal cells were not affected by the cytotoxic activities of either part of the C. silvatica plant. Therefore, the isolation of the bioactive compounds from the stems of C. silvatica and an investigation of their antitumor properties against different cancer cell lines may be required in future work. Additionally, the antitumor properties and a phytochemical investigation of C. silvatica have never been reported before. This study will thus serve as the basis for this plant, and more pharmacological investigations are recommended.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Iman Al-Gohary, Professor of Plant Taxonomy, for identifying and collecting the C. silvatica plants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.M.Y.; formal analysis, Y.M.A.-S.; investigation, D.A.M.M.; methodology, A.M.M.Y. and D.A.M.M.; supervision, Y.M.A.-S.; writing—original draft, A.M.M.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.M.M.Y. and Y.M.A.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Baskar R., Lee K.A., Yeo R., Yeoh K.-W. Cancer and radiation therapy: Current advances and future directions. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2012;9:193–199. doi: 10.7150/ijms.3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alshammari F.O.F.O., Al-Saraireh Y.M., Youssef A.M.M., Al-Sarayra Y.M., Alrawashdeh H.M. Cytochrome P450 1B1 Overexpression in Cervical Cancers: Cross-sectional Study. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2021;10:e31150. doi: 10.2196/31150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Saraireh Y., Alrawashdeh F., Al-Shuneigat J., Alsbou M., Alnawaiseh N., Al-Shagahin H. Screening of Glypican-3 Expression in Human Normal versus Benign and Malignant Tissues: A Comparative Study Glypican-3 expression in cancers. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia. 2016;13:687–692. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Saraireh Y.M., Alboaisa N.S., Alrawashdeh H.M., Hamdan O., Al-Sarayreh S., Al-Shuneigat J.M., Nofal M.N. Screening of cytochrome 4Z1 expression in human non-neoplastic, pre-neoplastic and neoplastic tissues. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020;14:1114. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Saraireh Y.M., Alshammari F., Youssef A.M.M., Al-Sarayreh S., Almuhaisen G.H., Alnawaiseh N., Al Shuneigat J.M., Alrawashdeh H.M. Profiling of CYP4Z1 and CYP1B1 expression in bladder cancers. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:5581. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C., Mai Z., Liu C., Yin S., Cai Y., Xia C. Natural Products in Preventing Tumor Drug Resistance and Related Signaling Pathways. Molecules. 2022;27:3513. doi: 10.3390/molecules27113513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Saraireh Y.M., Alshammari F., Youssef A.M.M., Al-Sarayra Y.M., Al-Saraireh R.A., Al-Muhaisen G.H., Al-Mahdy Y.S., Al-Kharabsheh A.M., Abufraijeh S.M., Alrawashdeh H.M. Cytochrome 4Z1 Expression Is Correlated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Cervical Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021;28:3573–3584. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28050306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Saraireh Y.M., Alshammari F., Youssef A.M.M., Al-Sarayreh S., Almuhaisen G.H., Alnawaiseh N., Al-Shuneigat J.M., Alrawashdeh H.M. Cytochrome 4Z1 Expression is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Colon Cancer Patients. OncoTargets Ther. 2021;14:5249–5260. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S332037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Saraireh Y.M., Alshammari F., Youssef A.M.M., Al-Tarawneh F., Al-Sarayreh S., Almuhaisen G.H., Satari A.O., Al-Shuneigat J., Alrawashdeh H.M. Cytochrome 4Z1 Expression is Associated with Unfavorable Survival in Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. Breast Cancer. 2021;13:565–574. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S329770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youssef A., El-Swaify Z., Al-saraireh Y., Dalain S. Cytotoxic activity of methanol extract of Cynanchumacutum L. seeds on human cancer cell lines. Latin Am. J. Pharm. 2018;37:1997–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youssef A.M.M., El-Swaify Z.A.S. Anti-Tumour Effect of two Persicaria species seeds on colon and prostate cancers. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2018;11:635–644. doi: 10.13005/bpj/1416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youssef A.M.M., El-Swaify Z.A.S., Al-Saraireh Y.M., Al-Dalain S.M. Anticancer effect of different extracts of Cynanchum acutum L. seeds on cancer cell lines. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2019;15:261. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_676_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang M., Lu J.-J., Ding J. Natural Products in Cancer Therapy: Past, Present and Future. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2021;11:5–13. doi: 10.1007/s13659-020-00293-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulos L. Flora of Egypt. Volume 1 Al Hadara Publishing; Cairo, Egypt: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav S., Hemke A., Umekar M. Convolvulaceae: A Morning Glory Plant Review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2018;51:103–117. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dehyab A.S., Bakar M.F.A., AlOmar M.K., Sabran S.F. A review of medicinal plant of Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region as source in tuberculosis drug discovery. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020;27:2457–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karaköse M. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Güce district, north-eastern Turkey. Plant Divers. 2022;44:577–597. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savo V., Giulia C., Maria G.P., David R. Folk phytotherapy of the amalfi coast (Campania, Southern Italy) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135:376–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martins F.M., Lima J.F., Mascarenhas A.A.S., Macedo T.P. Secretory structures of Ipomoea asarifolia: Anatomy and histochemistry. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2012;22:13–20. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang H., Hu J., Li Z., Yin Y. Two new resin glycosides from Calystegia sepium (L.) R. Br. with potential antitumor activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1257:132636. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cordell G.A. Fifty years of alkaloid biosynthesis in Phytochemistry. Phytochemistry. 2013;91:29–51. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv K.-Q., Ji H.-Y., Du G.-X., Peng S., Guo P.-J., Wang G., Zhu Y., Wang Q., Wang W.-Q., Xuan L.-J. Calysepins I–VII, Hexasaccharide Resin Glycosides from Calystegia sepium and Their Cytotoxic Evaluation. J. Nat. Prod. 2022;85:1294–1303. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.2c00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rezadoost M.H., Kumleh H.H., Ghasempour A. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction in breast cancer, skin cancer and glioblastoma cells by plant extracts. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019;46:5131–5142. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04970-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suma A., Ashika B., Roy C.L., Naresh S., Sunil K., Sathyamurthy B. GCMS and FTIR analysis on the methanolic extract of red Vitis Vinifera seed. World J. Pharm. Res. 2018;6:106–113. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hussein H.M. Analysis of trace heavy metals and volatile chemical compounds of Lepidium sativum using atomic absorption spectroscopy, gas chromatography-mass spectrometric and fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:2529–2555. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hameed I.H., Hussein H.J., Kareem M.A., Hamad N.S. Identification of five newly described bioactive chemical compounds in methanolic extract of Mentha viridis by using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. 2015;7:107–125. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adegoke A.S., Jerry O.V., Ademola O.G. GC-MS analysis of phytochemical constituents in methanol extract of wood bark from Durio zibethinus Murr. Int. J. Med. Plants Nat. Prod. 2019;5:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selvamangai G., Bhaskar A. Analysis of phytocomponents in the methanolic extract of Eupatorium triplinerve by GC-MS method. Int. J. Drug Dev. Res. 2013;5:384–391. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reza A.A., Haque M.A., Sarker J., Nasrin M.S., Rahman M.M., Tareq A.M., Khan Z., Rashid M., Sadik M.G., Tsukahara T. Antiproliferative and antioxidant potentials of bioactive edible vegetable fraction of Achyranthes ferruginea Roxb. in cancer cell line. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021;9:3777–3805. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajeswari G., Murugan M., Mohan V. GC-MS analysis of bioactive components of Hugonia mystax L.(Linaceae) Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora S., Kumar G. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) determination of bioactive constituents from the methanolic and ethyl acetate extract of Cenchrus setigerus Vahl (Poaceae) J. Pharm. Innov. 2017;2:635–640. [Google Scholar]

- 32.VanderSluis L., Mazurak V.C., Damaraju S., Field C.J. Determination of the relative efficacy of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid for anti-cancer effects in human breast cancer models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2607. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raina S., Sharma V., Sheikh Z.N., Kour N., Singh S.K., Zari A., Zari T.A., Alharby H.F., Hakeem K.R. Anticancer Activity of Cordia dichotoma against a Panel of Human Cancer Cell Lines and Their Phytochemical Profiling via HPLC and GCMS. Molecules. 2022;27:2185. doi: 10.3390/molecules27072185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar D., Kumar R., Khan A. GC-MS analysis of Sapindus marginatus seed extract in petroleum ether. South Asian J. Exp. Biol. 2022;12:767–773. doi: 10.38150/sajeb.12(5).p767-773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan Z., Yang R., Jiang Y., Yang Z., Yang J., Zhao Q., Lu Y. Induction of apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia HL60 cells by panaxynol and panaxydol. Molecules. 2011;16:5561–5573. doi: 10.3390/molecules16075561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubab M., Chelliah R., Saravanakumar K., Barathikannan K., Wei S., Kim J.-R., Yoo D., Wang M.-H., Oh D.-H. Bioactive Potential of 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol and Benzofuran from Brassica oleracea L. var. capitate f, rubra (Red Cabbage) on Oxidative and Microbiological Stability of Beef Meat. Foods. 2020;9:568. doi: 10.3390/foods9050568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohammed G.J., Omran A.M., Hussein H.M. Antibacterial and phytochemical analysis of Piper nigrum using gas chromatography-mass Spectrum and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2016;8:977–996. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anand T., Gokulakrishnan K. Phytochemical analysis of Hybanthus enneaspermus using UV, FTIR and GC-MS. IOSR J. Pharm. 2012;2:520–524. doi: 10.9790/3013-0230520524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gopinath S., Sakthidevi G., Muthukumaraswamya S., Mohan V. GC-MS analysis of bioactive constituents of Hypericum mysorense (Hypericaceae) J. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2013;3:6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Sayed O.H., Asker M.M., Shash S.M., Hamed S.R. Isolation, structure elucidation and biological activity of Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate produced by Penicillium janthinellum 62. Int. J. Chem.Tech. Res. 2015;8:58–66. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saeidnia S., Manayi A., Gohari A.R., Abdollahi M. The story of beta-sitosterol-a review. Eur. J. Med. Plants. 2014;4:590. doi: 10.9734/EJMP/2014/7764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sudha T., Chidambarampillai S., Mohan V. GC-MS analysis of bioactive components of aerial parts of Fluggea leucopyrus Willd.(Euphorbiaceae) J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013;3:126–130. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bao X., Zhang Y., Zhang H., Xia L. Molecular Mechanism of β-Sitosterol and its Derivatives in Tumor Progression. Front. Oncol. 2022;12:926975. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.926975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novotny L., Abdel-Hamid M., Hunakova L. Anticancer potential of β-sitosterol. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2017;2:129. doi: 10.15344/2456-3501/2017/129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aghaei M., Yazdiniapour Z., Ghanadian M., Zolfaghari B., Lanzotti V., Mirsafaee V. Obtusifoliol related steroids from Euphorbia sogdiana with cell growth inhibitory activity and apoptotic effects on breast cancer cells (MCF-7 and MDA-MB231) Steroids. 2016;115:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bębenek E., Chrobak E., Marciniec K., Kadela-Tomanek M., Trynda J., Wietrzyk J., Boryczka S. Biological activity and in silico study of 3-modified derivatives of betulin and betulinic aldehyde. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1372. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitić Z.S., Jovanović B., Jovanović S.Č., Stojanović-Radić Z.Z., Mihajilov-Krstev T., Jovanović N.M., Nikolić B.M., Marin P.D., Zlatković B.K., Stojanović G.S. Essential oils of Pinus halepensis and P. heldreichii: Chemical composition, antimicrobial and insect larvicidal activity. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019;140:111702. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choudhury D.K., Barman T., Rajbongshi J. Qualitative phytochemical screening and GC-MS analysis of Musa sapientum Spadix. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019;8:2456–2460. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hussein H.J., Hameed I.H., Hadi M.Y. Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) technique for analysis of bioactive compounds of methanolic leaves extract of Lepidium sativum. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2017;10:3981–3989. doi: 10.5958/0974-360X.2017.00723.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hasan A., Artika I., Kuswandi T. Analysis of active components of Trigona spp. propolis from Pandeglang Indonesia. Glob. J. Biol. Agric. Health Sci. 2014;3:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adeoye-Isijola M.O., Olajuyigbe O.O., Jonathan S.G., Coopoosamy R.M. Bioactive compounds in ethanol extract of Lentinus squarrosulus Mont-a Nigerian medicinal macrofungus. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2018;15:42–50. doi: 10.21010/ajtcamv15i2.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Marzoqi A.H., Hameed I.H., Idan S.A. Analysis of bioactive chemical components of two medicinal plants (Coriandrum sativum and Melia azedarach) leaves using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2015;14:2812–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Fayoumy E.A., Shanab S.M., Gaballa H.S., Tantawy M.A., Shalaby E.A. Evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of crude extract and different fractions of Chlorella vulgaris axenic culture grown under various concentrations of copper ions. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021;21:51. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-03194-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baky M.H., Shawky E.M., Elgindi M.R., Ibrahim H.A. Comparative Volatile Profiling of Ludwigia stolonifera Aerial Parts and Roots Using VSE-GC-MS/MS and Screening of Antioxidant and Metal Chelation Activities. ACS Omega. 2021;6:24788–24794. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c03627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang Y., Pei J., Zheng Y., Miao Y.-j., Duan B.-z., Huang L.-f. Gallic Acid: A Potential Anti-Cancer Agent. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2021;28:661–671. doi: 10.1007/s11655-021-3345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azarcoya-Barrera J., Wollin B., Veida-Silva H., Makarowski A., Goruk S., Field C.J., Jacobs R.L., Richard C. Egg-Phosphatidylcholine Attenuates T-Cell Dysfunction in High-Fat Diet Fed Male Wistar Rats. Front. Nutr. 2022;9:811469. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.811469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bae J., Kim N., Shin Y., Kim S.-Y., Kim Y.-J. Activity of catechins and their applications. Biomed. Dermatol. 2020;4:8. doi: 10.1186/s41702-020-0057-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Espíndola K.M.M., Ferreira R.G., Narvaez L.E.M., Silva Rosario A.C.R., Da Silva A.H.M., Silva A.G.B., Vieira A.P.O., Monteiro M.C. Chemical and pharmacological aspects of caffeic acid and its activity in hepatocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:541. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee S.-H., Kim J.K., Kim D.W., Hwang H.S., Eum W.S., Park J., Han K.H., Oh J.S., Choi S.Y. Antitumor activity of methyl gallate by inhibition of focal adhesion formation and Akt phosphorylation in glioma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2013;1830:4017–4029. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pei K., Ou J., Huang J., Ou S. p-Coumaric acid and its conjugates: Ddietary sources, pharmacokinetic properties and biological activities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016;96:2952–2962. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim J.K., Park S.U. A recent overview on the biological and pharmacological activities of ferulic acid. EXCLI J. 2019;18:132–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Azaat A., Babojian G., Nizar I. Phytochemical Screening, Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities of Euphorbia hyssopifolia L. against MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cell Line. J. Turkish Chem. Soc. 2022;9:295–310. doi: 10.18596/jotcsa.1021449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arya S.S., Rookes J.E., Cahill D.M., Lenka S.K. Vanillin: A review on the therapeutic prospects of a popular flavouring molecule. Adv. Trad. Med. 2021;21:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s13596-020-00531-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sepúlveda L., Ascacio A., Rodríguez-Herrera R., Aguilera-Carbó A., Aguilar C.N. Ellagic acid: Biological properties and biotechnological development for production processes. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011;10:4518–4523. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stabrauskiene J., Kopustinskiene D.M., Lazauskas R., Bernatoniene J. Naringin and naringenin: Their mechanisms of action and the potential anticancer activities. Biomedicines. 2022;10:1686. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10071686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alshehri M.M., Sharifi-Rad J., Herrera-Bravo J., Jara E.L., Salazar L.A., Kregiel D., Uprety Y., Akram M., Iqbal M., Martorell M. Therapeutic potential of isoflavones with an emphasis on daidzein. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021:6331630. doi: 10.1155/2021/6331630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ruwizhi N., Aderibigbe B.A. Cinnamic acid derivatives and their biological efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:5712. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Youssef A.M., Maaty D.A., Al-Saraireh Y.M. Phytochemistry and Anticancer Effects of Mangrove (Rhizophora mucronata Lam.) Leaves and Stems Extract against Different Cancer Cell Lines. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16:4. doi: 10.3390/ph16010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Youssef A.M.M., EL-Swaify Z.A.S., Maaty D.A., Youssef M.M. Phytochemistry and Antiviral Properties of Two Lotus Species Growing in Egypt. Vitae. 2021;28:e7. doi: 10.17533/udea.vitae.v28n3a348069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Youssef A., El-Swaify Z., Maaty D., Youssef M. Comparative study of two Lotus species: Phytochemistry, cytotoxicity and antioxidant capacity. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2020;8:537–548. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Al-saraireh Y.M., Youssef A.M., Alshammari F.O., Al-Sarayreh S.A., Al-Shuneigat J.M., Alrawashdeh H.M., Mahgoub S.S. Phytochemical characterization and anti-cancer properties of extract of Ephedra foeminea (Ephedraceae) aerial parts. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2021;20:1675–1681. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v20i8.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Al-Saraireh Y.M., Youssef A.M., Alsarayreh A., Al Hujran T.A., Al-Sarayreh S., Al-Shuneigat J.M., Alrawashdeh H.M. Phytochemical and anti-cancer properties of Euphorbia hierosolymitana Boiss. crude extracts. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2021;9:13–23. doi: 10.56499/jppres20.916_9.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.