Abstract

The kinetics of infection and the pathogenic effects on the reproductive function of laboratory mice infected with Bartonella birtlesii recovered from an Apodemus species are described. B. birtlesii infection, as determined by bacteremia, occurred in BALB/c mice inoculated intravenously. Inoculation with a low-dose inoculum (1.5 × 103 CFU) induced bacteremia in only 75% of the mice compared to all of the mice inoculated with higher doses (≥1.5 × 104). Mice became bacteremic for at least 5 weeks (range, 5 to 8 weeks) with a peak ranging from 2 × 103 to 105 CFU/ml of blood. The bacteremia level was significantly higher in virgin females than in males but the duration of bacteremia was similar. In mice infected before pregnancy (n = 20), fetal loss was evaluated by enumerating resorption and fetal death on day 18 of gestation. The fetal death and resorption percentage of infected mice was 36.3% versus 14.5% for controls (P < 0.0001). Fetal suffering was evaluated by weighing viable fetuses. The weight of viable fetuses was significantly lower for infected mice than for uninfected mice (P < 0.0002). Transplacental transmission of Bartonella was demonstrated since 76% of the fetal resorptions tested was culture positive for B. birtlesii. The histopathological analysis of the placentas of infected mice showed vascular lesions in the maternal placenta, which could explain the reproductive disorders observed. BALB/c mice appeared to be a useful model for studying Bartonella infection. This study provides the first evidence of reproductive disorders in mice experimentally infected with a Bartonella strain originating from a wild rodent.

Bartonella spp. are gram-negative, hemotropic, and fastidious bacteria that are isolated from a wide range of hosts, including humans, felids, ruminants, and rodents (6). Seven of these emerging pathogens have been associated to a variety of acute or subacute human diseases, including Carrion's disease (17), trench fever (3), cat scratch disease (CSD) (4), bacillary angiomatosis (20), Parinaud's oculoglandular syndrome (4), neuroretinitis (19), fever and neurological symptoms (37), and endocarditis (8, 16, 28, 34). Beside these clinical entities, asymptomatic infections have also been described in humans infected with some Bartonella species (Bartonella bacilliformis and B. quintana), which were isolated from the blood of apparently healthy humans (17, 35). Similarly, natural infection in animals, such as cats with B. henselae, B. clarridgeiae, or B. koehlerae, is mainly considered to be asymptomatic, despite long-lasting bacteremia (9, 14, 21, 38). However, several reports indicated that experimental B. henselae infection in cats induces various symptoms, such as fever, anorexia, lymphadenopathy (23, 31), or reproductive failure (13). Furthermore, Glaus et al. (11) reported in naturally infected Bartonella sick cats an association between seropositivity and stomatitis and a variety of diseases of the kidneys and the urinary tract.

Until now, only two types of murine models have been described. A homologous model, using several species of Bartonella isolated from wild rodents (25, 26), and a heterologous infection of mice with B. henselae (18, 32). The latter led to pathologic changes such as lymphadenopathy, as observed for CSD in humans or in experimental infection in cats, but failed to reproduce long-term bacteremia. Furthermore, the very high inoculum doses used in these experiments may be much higher than those occurring in natural infections. The homologous model did reproduce asymptomatic bacteremia in cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) and white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus). However, these two wild rodent species are not easy to maintain in laboratory conditions, and their immune system is not well defined.

The objectives of the present study were (i) to establish a new model of persistent infection with Bartonella, using BALB/c mice, and (ii) to investigate the pathogenicity of Bartonella on the reproductive functions of laboratory mices. B. birtlesii type strain (CIP106294T) was used as inoculum and was injected into BALB/c mice (5). This model allowed us to demonstrate that Bartonella induces reproductive failure in laboratory mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Adult BALB/c (inbred), 8 to 10 weeks old, were purchased from Charles River/Iffa-Credo (L'Arbresle, France). They were used in these experiments at between 8 and 16 weeks of age. They were free of specific viral and bacterial pathogens according to the results of the routine screening procedure performed by the manufacturer. The mice were housed in microisolator cages and provided with food and water ad libitum. The animals were culture negative for Bartonella infection, prior to experimental infection, as ascertained by blood plating onto agar. All mice were also seronegative for B. birtlesii antibodies.

Bacteria.

B. birtlesii (IBS325 strain) was used for the experimental infection. This strain was originally isolated from a field mouse, Apodemus sp. It was identified as a Bartonella species by phenotypic and genotypic characterization and designated as B. birtlesii sp. nov. IBS 325T (CIP106294T) (5).

B. birtlesii was plated on 5% defibrinated rabbit blood brain heart infusion (BHI) agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 35°C (Sanyo incubator). The culture was harvested after 9 days, suspended in fetal calf serum, and aliquoted as stock culture at −80°C. B. birtlesii was passaged once in BALB/c mice before the stock inoculum was established. Grown bacteria were harvested in normal saline, and inoculum doses were adjusted by turbidimetry. The culture purity and number of CFU injected into the mice were established by culturing a 10 fold-dilution of inoculum on 5% defibrinated rabbit BHI agar in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 15 days.

Bacteria harvested from blood or fetuses were confirmed to be Bartonella sp. by PCR, using primers BHCS 781 and BHCS 1137, as described by Norman et al. (29).

Blood sampling and culture.

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of 2,2, 2-tribromoethanol (250 mg/kg; Aldrich) 5 min before aseptic cardiac puncture. Blood samples (100 μl) were collected in EDTA vacuum tubes (Greiner). Blood collection was performed on each mouse just prior to and after inoculation and at different times, as described below. The EDTA-blood was subjected to osmotic shock with distilled water and centrifugation (300 × g for 60 min at room temperature; Jouan E96). The resulting blood pellet was resuspended in 250 μl of BHI broth. Then, 50 μl of undiluted or 10-fold-diluted suspension was immediately plated in duplicate on 5% defibrinated rabbit blood BHI agar in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. CFU were counted 15 days after plating. The detection threshold of bacterial concentration was equivalent to 50 CFU per ml or per fetus. The bacteremia was expressed as the mean number of CFU per milliliter of blood after we took into account the volume of the blood pellet.

Experimental design.

In two preliminary experiments, BALB/c mice were infected with 1.5 × 103 to 3 × 105 CFU of B. birtlesii intravenously (i.v.) in the lateral tail vein (n = 40) (Table 1). In addition, to evaluate the effect of gender on bacteremia in mice, eight male and eight female BALB/c mice were inoculated i.v. with 2.5 × 105 CFU. Blood samples were collected from each mouse prior to infection and weekly until up to 4 weeks of consecutive negative cultures.

TABLE 1.

Bacteremia in BALB/c mice after infection by the i.v. route with different doses of B. birtlesii

| Expt | No. of mice | Inoculum (CFU/mouse) | Bacteremia at day 15 p.i. (range [CFU/ml of blood]) | Duration of bacteremia (range [days]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 3 × 104 | 1.5 × 104–9 × 104 | 49–56 |

| 8 | 3 × 105 | 2.5 × 104–9 × 104 | 49–56 | |

| 2 | 8 | 1.5 × 103 | 0–4.9 × 103 | 0–56 |

| 8 | 1.5 × 104 | 1 × 104–3.7 × 104 | 42–56 | |

| 8 | 1.5 × 105 | 1 × 104–3 × 104 | 56 |

To evaluate whether B. birtlesii infection adversely affected the reproductive outcome, female BALB/c mice (n = 48) were initially inoculated i.v. with either apyrogenic saline (n = 20) or 6 × 104 CFU of B. birtlesii (n = 28) after being randomly designated as either a control or an infected animal. Nine days after inoculation, 20 infected and 20 control female mice were simultaneously bred with 20 uninfected male BALB/c mice (1 male for 2 females). The remaining eight infected female mice were not bred and were used as an inoculum control. After mating with a male, the female mice were observed daily for the formation of a vaginal plug. The females with a vaginal plug were then individually caged in microisolators. Pregnancy was timed according to the appearance of the copulatory plug. All mice were humanely killed on day 18 of gestation and examined for the presence of viable, resorbed, and dead fetuses. Fetal resorption was identified on the basis of small fetal size (<3 mm) and lack of discernible fetal tissues at an implant site containing placental tissue. Fetal resorptions and dead and viable fetuses were all collected and frozen at −20°C before culture. All of the viable fetuses were weighed (Sartorius PT210; precision, 0.01 g), humanely killed, and their spleen and liver were aseptically collected and frozen at −20°C before culture. Pregnant mouse blood was collected during cesarean section. Blood of the 20 males used in the reproduction experiment was collected 4 weeks after mating with infected females. As a control, the blood of the eight infected nonreproductive female mice was collected on days 0, 8, 15, 21, 28, 35, and 42 postinfection (p.i.). Mouse blood was collected into an EDTA tube and immediately plated as described above.

Histopathological analysis.

Placentas with discernible material from pregnant mice were collected from three infected mice (19 placentas) and two noninfected mice (15 placentas) and were fixed in 3% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. After the samples were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin wax at 56°C, 5-μm sections were cut, stained with hematoxylin-eosin-safran, and analyzed for histopathological changes. Some sections were subsequently stained with Congo red. Each anatomic site from the maternal placenta (endometrium of the uterus and decidua basalis) and the fetal placenta (chorionic plate, trophoblast giant cell zone, and labyrinthine zone) was assessed independently for histopathological changes by two Board-certified veterinary pathologists.

Statistical analysis.

For bacteremic curves, data are expressed as geometric means ± the standard error (SE) of the mean. The data were analyzed by analysis of variance of repeated measures (StatView Software, version 5.0; Abacus concept, Berkeley, Calif.). The mean bacterium level of pregnant and nonpregnant mice and the arithmetic means of fetus weight between the experimental and control groups were compared by Student's t test. The homogeneity of the occurrence of fetal resorption and dead fetus was evaluated between infected and uninfected females by using the chi-square test. Significance of all the analyses was established at P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

Susceptibility of BALB/c mice to i.v. infection with B. birtlesii.

Eight BALB/c female mice were inoculated i.v. with 3 × 104 CFU of B. birtlesii, and eight BALB/c female mice were inoculated with 3 × 105 CFU of B. birtlesii (Table 1, experiment 1, and Fig. 1). Bacteremia was detected on day 8 p.i. and reached a peak (mean bacteremia, 5 × 104 CFU/ml) on day 14, regardless of the number of injected bacteria. Bacteremia then decreased and became negative by, on average, 10 weeks after inoculation. None of the mice presenting with bacteremia relapsed during the 4 weeks following the last observed positive culture, regardless of the number of injected bacteria. Bacteremia persisted at least until day 49 p.i. in BALB/c mice.

FIG. 1.

B. birtlesii bacteremia kinetics in BALB/c mice after i.v. infection. Mice (n = 8 per group) were infected with 3 × 104 (A) or 3 × 105 (B) CFU of B. birtlesii. No bacteremia was detected at day 0. Data are expressed as the mean ± the SE for each dot.

Evaluation of low doses of inoculum was performed in a second experiment. Three different doses (1.5 × 103, 1.5 × 104, and 1.5 × 105 CFU) of B. birtlesii were injected by the i.v. route into eight BALB/c mice per dose (Table 1, experiment 2). Bacteremia levels obtained in the second experiment were compared with those of the previous experiment (Table 1). In these two experiments, the geometric mean levels of bacteremia obtained with different doses were not statistically different. For the 1.5 × 103 CFU inoculum, bacteremia did not occur in all inoculated mice, since only six of the eight mice (75%) became bacteremic. In contrast, for inoculum doses of ≥1.5 × 104 CFU, all inoculated mice became bacteremic.

Effect of gender and reproductive status of mice on bacteremia.

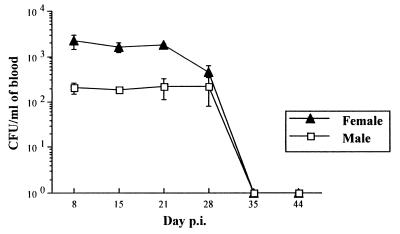

All male (n = 8) and female (n = 8) BALB/c mice inoculated simultaneously by the i.v. route with 2.5 × 105 CFU became bacteremic. The bacteremia was significantly higher in females than in males. The peak of B. birtlesii infection occurred between day 7 and day 30 p.i., and bacteremia disappeared on day 35 p.i. (Fig. 2) for both genders. The comparison of bacteremia levels between 8 nonpregnant and 12 pregnant mice showed that gestation amplified the number of CFU per milliliter of blood. The levels of bacteremia were, respectively, 0.2 × 103 and 0.6 × 103 CFU per ml on day 18 of gestation (day 28 p.i.), and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05).

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of bacteremia in male and virgin female BALB/c mice after i.v. infection with 2.5 × 105 CFU of B. birtlesii. No bacteremia was detected at day 0. Data (obtained from eight mice) are expressed as the mean ± the SE.

Effect of Bartonella infection on the reproductive function of BALB/c mice.

Mating occurred 10 to 14 days after the injection of B. birtlesii, but no blood collection was performed on the 20 pregnant mice until cesarean section. All 20 infected pregnant females were euthanized on day 18 of gestation, which corresponded to days 28 to 32 p.i., as were the 20 uninfected pregnant female mice. The peak of bacteremia in the eight nonpregnant control-infected mice occurred 21 days after injecting B. birtlesii (data not shown).

More B. birtlesii-infected mice were not pregnant at the time of cesarean section (5 [26.3%] of 19 mice with a vaginal plug) than for the uninfected control mice (2 [11.7%] of 17 mice with a vaginal plug) (Table 2). All inoculated females were bacteremic at that time. The total number of dead and viable fetuses and the mean number of total fetuses by litter were lower for infected females, but the differences were not statistically significant (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Reproductive performance and effect on litter size and fetus resorption or weight in female BALB/c mice infected with B. birtlesii (infected mice) or with normal saline solution (noninfected mice)

| Parameter | Noninfected mice | Infected mice | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of females | 20 | 20 | NDf |

| No. of vaginal plugs | 17 | 19 | ND |

| No. of gravid females at time of cesarean section | 15 | 14 | ND |

| Total no. of fetusesa | 110 | 91 | ND |

| Mean no. of fetusesa/litter (range) | 7.3 ± 1.8 (4–10) | 6.5 ± 2.4 (3–10) | NSg |

| Mean wt (g) of 18-day-old fetusesb | 1.09 ± 0.17 | 0.99 ± 0.16 | <0.0002c |

| No. of mice with one resorption or more (%) | 8 (53.3) | 13 (92.9) | <0.0001d |

| No. of resorbed and/or dead fetuses (%) | 16 (14.5) | 33 (36.3) | <0.0001d |

| No. of positive cultures in fetal resorptions (%) | ND | 16 (76c) | ND |

That is, viable, resorbed, and dead fetuses.

That is, viable fetuses only.

Student t test.

Chi-square test.

A total of 16 of 22 fetal resorption cultures.

ND, not determined.

NS, not significant.

The mean weight of viable 18-day-old fetuses from infected females (0.99 ± 0.16 g) was significantly lower than that from uninfected mice (1.09 ± 0.17 g) (P < 0.0002). In that experiment, 13 (92.9%) of the 14 gravid infected mice presented resorbed and dead fetuses, whereas only 8 (53.3%) of the 15 gravid uninfected mice showed fetal resorption (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). The percentage of resorbed and dead fetuses from infected mice (33 of 91, 36.3%) was significantly different from that of uninfected mice (16 of 110, 14.5%) (P < 0.0001). Seventy-six percent (16 of 21) of fetal resorptions tested were positive for culture of B. birtlesii, but none of the liver-spleen extracts of 58 viable fetuses born from infected mice were positive. None of the 20 males was bacteremic 4 weeks after mating with infected females.

Pathology findings.

The histopathological analysis of the placentas of the infected mice, compared to the analysis of the noninfected mouse placentas, showed some lesions in the maternal placenta. The lesions were seen in the vessels of the endometrium of all 19 placentas from the three infected mice. These lesions were not seen in the 15 placentas from the two noninfected mice. The lumen of the vessels contained a high number of neutrophil granular cells. The wall of the vessels appeared more eosinophilic, thickened, and infiltrated by neutrophils that were sometimes degenerated (Fig. 3). A homogeneous eosinophilic Congo red-negative material was observed in the vessel's wall and was typical of fibrinoid necrosis. A neutrophilic leukocytoclastic vasculitis with moderate fibrinoid necrosis was then observed in the endometrial vessels of the placenta. The degree of severity of the lesions observed varied among the different placentas from the same infected pregnant mouse. No specific lesions were observed in the fetal placentas of either infected or noninfected mice. We were not successful to detect Bartonella antigens by immunostaining with polyclonal antibodies (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Histopathological findings. The lesions are seen in the vessels of the endometrium. The muscular wall (M) is thickened, due to an eosinophilic deposit suggestive of fibrinoid necrosis. Neutrophils (N) are present in large numbers in the lumen (L) of the vessels and are seen infiltrating the vessel wall. Magnification, × 800.

DISCUSSION

We have established a new murine model of Bartonella infection using BALB/c mice infected with B. birtlesii isolated from Apodemus sp. This model allowed us to investigate the influence of inoculum doses, gender, and reproductive status on the course of Bartonella experimental infection. Furthermore, we demonstrated reproductive failure in infected pregnant mice.

This model differs from those conducted with BALB/c mice infected with B. henselae (18, 32). We obtained a persistent bacteremia, as observed in naturally or experimentally infected cats (1, 22, 23, 33) or cotton rats and white-footed mice (25, 26). The i.v. injection of B. birtlesii into BALB/c mice induced a long-lasting bacteremia, which was already detectable at day 8 p.i. and lasted 5 to 8 weeks p.i. The course of bacteremia was similar to that described by Kosoy et al. (25) in the cotton rat model. With inoculum doses higher than 1.5 × 103 CFU, bacteremia was systematically obtained. There was no significant difference in the bacteremia level regardless of the inoculum dose above that threshold.

This study also demonstrated transplacental transmission of B. birtlesii, which occurred in bacteremic pregnant mice. Our study confirmed the previous observation made by Kosoy et al. (24) of in utero infection in naturally infected rodents. Congenital transmission of Bartonella species in rodents contrasts with the inability to experimentally demonstrate any in utero infection of female cats with B. henselae (1, 13) or domestic cattle (H. J. Boulouis et al., unpublished data). Such differences between congenital infection in mice and that seen in other mammals may be related to the differences in placentation type (hemochorial in rodent and in primates versus endotheliochorial in cats and epitheliochorial in cattle). We were not able to isolate Bartonella from viable fetuses, whereas Kosoy et al. (24) reported bacteremic neonates in naturally infected rodents. Such a difference could be explained in part by the fact that the immune status of the infected mice at the time of gestation was different. In our study, all mice were naive prior to infection and more likely responded immunologically to the infection. In naturally infected mice, the mice may have been multiparous animals and have developed some immunotolerance to Bartonella antigens, as suggested by Kosoy et al. (24).

Our study demonstrates that, in pregnant mice, the concentrations of Bartonella in blood are higher than they are in nonpregnant mice and that B. birtlesii has an abortifacient effect. Gestation enhanced the level of B. birtlesii infection, and the gender of the mice influenced the course of bacteremia. These results suggest that bacterial multiplication could be directly or indirectly under hormonal influence. Furthermore, cellular immunity is known to decline during gestation. Therefore, in gravid mice, the immune response against Bartonella could be impaired.

B. birtlesii infection in mice affected the outcome of pregnancy, causing resorption, fetal death, and fetus weight loss. Significantly higher numbers of resorbed and dead fetuses occurred in infected mice than in uninfected mice, and B. birtlesii was isolated from 76% of the resorbed fetuses tested but not from the spleens and livers of dead and living fetuses. However, the placentas of nonresorbed fetuses showed vascular lesions on the maternal part but not on the fetal part of the placenta. These lesions could be the mild initial phase of a pathological process further leading to fetal death or resorption in infected pregnant mice.

Congenital transmission could be favored by high levels of bacteremia in dams, and fetal resorptions could result from the multiplication of Bartonella in the fetuses or their placentas. Our study showed that Bartonella-positive resorbed fetuses were present at the same time as uninfected fetuses from the same litter. However, the placentas of these uninfected fetuses presented mild vascular lesions. This suggests that the placenta is probably a site of Bartonella multiplication as for the murine model of brucellosis (36).

Finally, in our experiments, the mean weight of the viable fetuses from B. birtlesii-infected mice was significantly lower than the weight of viable fetuses from uninfected mice. However, viable fetuses from Bartonella-infected dams were culture negative. The lower weights of the viable fetuses from infected mice could be explained by fetal suffering during gestation, as suggested at least in part by the presence of microvascular lesions.

Our results also suggest that cellular immune response might participate in Bartonella infection control. Recent studies have demonstrated that some cytokines, such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) are deleterious to fetal survival (7, 15, 27). Preliminary immunological studies with BALB/c mice or cats (12, 32, 33) showed that the Th1 response, inducing a cellular response, was first observed after infection by B. henselae. This response is characterized by the secretion of IFN-γ and interleukin-2. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are also known to induce fetal resorption (2) and are a component of the cell wall of Bartonella (10). LPS, one of the main pathogenic factors of gram-negative bacteria, could be a nonspecific inductor of abortigenic cytokines, such as TNF-α (30). A maternal immune response to Bartonella could have generated such cytokines that were deleterious to fetuses. These results require further investigation to determine the influence of the inoculation period during pregnancy.

This study provides the first evidence of reproductive disorders in mice experimentally infected with B. birtlesii, found in wild rodents. Furthermore, our model of long-lasting bacteremia in BALB/c mice will be highly suitable for studying the humoral and cellular immune responses in this laboratory animal species, since all the tools necessary to investigate immune response in laboratory mice are available.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by 2-year grant 99-1800 of the Ministry of National Education, Resarch, and Technology (Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie, Maladies Infectieuses et Parasitaires) and grant 99/7468 of the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC).

We are grateful to Corinne Bouillin, Christelle Gandoin, Valérie Mezières, Sylvie Manin, and Danièle Couillard for technical assistance. We thank Didier Lacombe for animal care, and Chao-Chin Chang, Laurent Tiret, and René Chermette for their comments and suggestions on the manuscript. We are grateful to A. M. Wall of the Translation Department of INRA for reviewing the English version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott R, Chomel B, Kasten R, Floyd-Hawkins K, Kikuchi Y, Koehler J, Pedersen N. Experimental and natural infection with Bartonella henselae in domestic cats. Comp Immun Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;20:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9571(96)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baines M G, Duclos A J, de Fougerolles A R, Gendron R L. Immunological prevention of spontaneous early embryo resorption is mediated by nonspecific immunostimulation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1996;35:34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass J W, Vincent J M, Person D A. The expanding spectrum of Bartonella infections. I. Bartonellosis and trench fever. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:2–10. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bass J W, Vincent J M, Person D A. The expanding spectrum of Bartonella infections. II. Cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:163–179. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199702000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bermond D, Heller R, Barrat F, Delacour G, Dehio C, Alliot A, Monteil H, Chomel B, Boulouis H-J, Piémont Y. Bartonella birtlesii sp. nov., isolated from small mammals (Apodemus spp.) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1973–1979. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-6-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breitschwerdt E B, Kordick D L. Bartonella infection in animals: carriership, reservoir potential, pathogenicity, and zoonotic potential for human infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:428–438. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.3.428-438.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buendia A J, Montes de Oca R, Navarro J A, Sanchez J, Cuello F, Salinas J. Role of polymorphonuclear neutrophils in a murine model of Chlamydia psittaci-induced abortion. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2110–2116. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2110-2116.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly J S, Vorthington M G, Brenner D J, Moss C W, Hollis D G, Weyant R S, Steigerwalt A G, Weaver R E, Daneshvar M I, O'Connor S P. Rochalimea elizabethae sp. nov. isolated from a patient with endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;30:872–881. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.872-881.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Droz S, Chi B, Horn E, Steigerwalt A G, Withney A M, Brenner D J. Bartonella koehlerae sp. nov., isolated from cats. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1117–1122. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1117-1122.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foca A, Matera G, Liberto M C, Diana R, Pollio A, Martucci M, Gulletta M. In vitro effects of LPS from Bartonella quintana on inflammator mediators. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;37:288. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaus T, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Greene C, Glaus B, Wolfensberger C, Lutz H. Seroprevalence of Bartonella henselae infection and correlation with disease in cats in Switzerland. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2883–2885. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2883-2885.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guptill L, Slater L N, WU C C, Lin T L, Glickman L T, Welch D F, HogenEsch H. Experimental infection of young specific pathogen-free cats with Bartonella henselae. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:206–216. doi: 10.1086/514026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guptill L, Slater L N, WU C C, Lin T L, Glickman L T, Welch D F, Tobolski J, HogenEsch H. Evidence of reproductive failure and lack of perinatal transmission of Bartonella henselae in experimentally infected cats. Vet Immun Immunopathol. 1998;65:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(98)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurfield A N, Boulouis H J, Chomel B B, Heller R, Kasten R W, Yamamoto K, Piémont Y. Coinfection with Bartonella clarridgeiae and Bartonella henselae and with different Bartonella henselae strains in domestic cats. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2120–2123. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2120-2123.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haddad E K, Duclos A J, Lapp W S, Baines M G. Early embryo loss is associated with the prior expression of macrophage activation markers in the decidua. J Immunol. 1997;158:4886–4892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes A H, Greenough T C, Balady G J, Regnery R L, Anderson B E, O'Keane J C, Fonger J D, McCrone E L. Bartonella henselae endocarditis in an immunocompetent adult. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1004–1007. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ihler G M. Bartonella bacilliformis: dangerous pathogen slowly emerging from deep background. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karem K L, Dubois K A, McGill S L, Regnery R L. Characterization of Bartonella henselae-specific immunity in Balb/c mice. Immunology. 1999;97:352–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerkhoff F T, Bergmans A M, van der Zee A, Rothova A. Demonstration of Bartonella grahamii DNA in ocular fluids of a patient with neuroretinitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4034–4038. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4034-4038.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koehler J E, Sanchez M A, Garrido C S, Whitfeld M J, Chen F M, Berger T G, Rodriguez-Barradas M C, Leboit P E, Tappero J W. Molecular epidemiology of Bartonella infections in patients with bacillary angiomatosis-peliosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1876–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kordick D L, Wilson K H, Sexton D J, Hadfield T L, Berkhoff H A, Breitschwerdt E B. Prolonged Bartonella bacteremia in cats associated with cat-scratch disease patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3245–3251. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3245-3251.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kordick D L, Breitschwerdt E B. Relapsing bacteremia after blood transmission of Bartonella henselae to cats. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:492–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kordick D L, Brown T T, Shin K, Breitschwerdt E B. Clinical and pathologic evaluation of chronic Bartonella henselae or Bartonella clarridgeiae infection in cats. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1536–1547. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1536-1547.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosoy M Y, Regnery R, Kosaya O, Jones D, Marston E, Childs J. Isolation of Bartonella-spp. from embryos and neonates of naturally infected rodents. J Wildl Dis. 1998;34:305–309. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-34.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosoy M Y, Regnery R, Kosaya O, Childs J. Experimental infection of cotton rats with three naturally occurring Bartonella species. J Wildl Dis. 1999;34:305–309. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-35.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosoy M Y, Saito E K, Green D, Marston E L, Childs J. Experimental evidence of host specificity of Bartonella infection in rodents. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;23:221–238. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9571(99)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin H, Mosmann T R, Guilbert T R, Tuntipopat S, Wegmann T G. Synthesis of T helper 2-type cytokines at the maternal fetal interface. J Immunol. 1993;151:4562–4573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurin M, Raoult D. Bartonella (Rochalimea) quintana infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:273–292. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norman A F, Regnery R, Jameson P, Greene C, Krause D C. Differentiation of Bartonella-like isolates at the species level by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism in the citrate synthase gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1797–1803. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1797-1803.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nowicki S, Selvarangan R, Anderson G. Experimental transmission of Neisseria gonorrhoeae from pregnant rat to fetus. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4974–4976. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4974-4976.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Reilly K L, Bauer R W, Freeland R L, Foil L D, Hughes K J, Rohde K R, Roy A F, Stout R W, Triche P C. Acute clinical disease in cats following infection with a pathogenic strain of Bartonella henselae LSU16. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3066–3072. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3066-3072.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regnath T, Mielke M E A, Arvand M, Hahn H. Murine model of Bartonella henselae infection in the immunocompetent host. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5534–5536. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5534-5536.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regnery R L, Rooney J A, Johnson A M, Nesby S L, Manzewitsch P, Beaver K, Olson J G. Experimentally induced Bartonella henselae infections followed by challenge exposure and microbial therapy in cats. Am J Vet Res. 1996;12:1714–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roux V, Eykyn S J, Wyllie S, Raoult D. Bartonella vinsonii subsp berkhoffii as an agent of a febrile blood culture-negative endocarditis in a human. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1698–1700. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1698-1700.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rydkina E, Roux V, Tarasevich I, Raoult D. Lice, Rickettsia prowazekii, and Bartonella quintana. In: Raoult D, Brouqui P, editors. Rickettsiae and rickettsial diseases at the turn of the third millenium. Paris, France: Elsevier; 1999. pp. 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobias L, Cordes D O, Schurig G G. Placental pathology of the pregnant mouse inoculated with Brucella abortus strain 2308. Vet Pathol. 1993;30:119–129. doi: 10.1177/030098589303000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welch D F, Caroll K C, Hofmeister E K, Persing D H, Robison D A, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J. Isolation of a new subspecies, Bartonella vinsonii subsp. arupensis, from a cattle rancher: identity with isolates found in conjunction with Borrelia burgdorferi and Babesia microti among naturally infected mice. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2598–2601. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2598-2601.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson D L, Sexton D J, Hadfield T L, Berkhoff H A, Breitschwerdt E B. Prolonged Bartonella bacteremia in cats associated with cat-scratch disease patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3245–3251. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3245-3251.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]