Abstract

A guinea pig model of experimental legionellosis was established for assessment of virulence of isolates of Legionella longbeachae. The results showed that there were distinct virulence groupings of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains based on the severity of disease produced in this model. Statistical analysis of the animal model data suggests that Australian isolates of L. longbeachae may be inherently more virulent than non-Australian strains. Infection studies performed with U937 cells were consistent with the animal model studies and showed that isolates of this species were capable of multiplying within these phagocytic cells. Electron microscopy studies of infected lung tissue were also undertaken to determine the intracellular nature of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 infection. The data showed that phagosomes containing virulent L. longbeachae serogroup 1 appeared bloated, contained cellular debris and had an apparent rim of ribosomes while those containing avirulent L. longbeachae serogroup 1 were compact, clear and smooth.

Legionella longbeachae serogroup 1 was first recognized as a pathogenic species of Legionella capable of causing pneumonia in 1980 (24). A second serogroup was also described in the same year in the only published report of isolation of this serogroup from a patient (5). Only two serogroups are defined for this species, distinguished from each other by direct fluorescent antibody staining. In the United States, serogroup 1 is associated with sporadic disease and is represented in the 10 to 15% of cases of pneumonia caused by species of Legionella other than L. pneumophila (33).

In Australia, there have been numerous cases of pneumonia caused by L. longbeachae serogroup 1, many clustered in time (6, 21, 23, 45; E. Gabbay, W. B. De Boer, J. A. Waring, and Q. A. Summers, Letter, Med. J. Aust. 164:704, 1996). Nearly half of all cases of pneumonia caused by Legionella in South Australia are due to L. longbeachae serogroup 1 (6, 45), which reflects the national trend (34, 36; Gabbay et al., letter). Infections due to L. longbeachae serogroup 1 have been reported in countries such as New Zealand, Sweden, Germany, Japan, Denmark, Canada, and The Netherlands (6, 20, 43).

Early investigations begun on this species in our laboratory suggested that L. longbeachae serogroup 1 was present in Australian commercial potting mix, where it was shown to survive for long periods of time (38). A survey of soil samples from Australia, Europe, and the United Kingdom determined that L. longbeachae was present in a large proportion of the Australian soil samples; however, all of the soil samples from Europe and the United Kingdom were negative for this species (39). L. longbeachae serogroup 1 has also been isolated from potting mix in Japan (20). Recently, a report summarizing the findings of a Legionnaires' disease investigation in California, Oregon, and Washington suggests that transmission from potting soil has occurred for the first time in the United States (7), although soil surveys for Legionella have not been conducted there (7). L. longbeachae organisms have been detected in water (35); however, this may not be the preferred ecological niche for the organism.

Nearly all of the studies undertaken to understand pathogenesis of Legionella have focused on L. pneumophila serogroup 1. A few studies have been undertaken with L. micdadei, the second most common etiologic agent of Legionnaires' disease in the Unites States (19, 33). L. micdadei infects primarily immunocompromised hosts, but this pathogen causes substantially fewer infections than L. pneumophila. Few virulence studies have been undertaken with L. longbeachae (25, 27), and little is known of the intracellular life cycle of the organism and what factors may contribute to pathogenicity. L. longbeachae serogroup 2 has been examined by intraperitoneal injection into guinea pigs and for the ability to infect and multiply in a protozoan model of infection using Tetrahymena pyriformis and Hartmannella vermiformis (13, 37, 44). L. longbeachae serogroup 2 ATCC 33484 has also been shown to replicate in guinea pig macrophages and A/J, C57BL/6, and DBA/2 mouse peritoneal macrophages (17). L. longbeachae serogroup 1 replicates in U937 cells (27) but is unable to replicate in Mono Mac-6 cells or in Acanthamoebae castellanii (14, 25). A recent publication from our laboratory has shown that an L. longbeachae serogroup 1 clinical isolate is capable of causing death and disease in guinea pigs exposed to an aerosol dose of the organism, similar to the observation with L. pneumophila (10, 12). The histological appearance of the lungs taken from the animal was consistent with a severe acute pneumonia, and this was similar to that seen with L. pneumophila serogroup 1 (12).

Here, the aerosol in vivo model of infection of guinea pigs was used to examine a panel of L. longbeachae isolates in order to assess differences in virulence within the species. Several strains of L. longbeachae were also tested for their ability to infect macrophage-like U937 cells, as it is generally assumed that disease caused by L. pneumophila is due to the ability of the organism to grow within alveolar macrophages and is a hallmark of virulent Legionella strains (8, 11, 22, 27).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

Isolates of Legionella used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains were routinely cultured on charcoal yeast extract α-ketoglutarate (CYE) plates (21) at 35°C. For counts in lung tissue, Legionella organisms were plated on CYE plates containing pimafucin (250 mg/liter), polymyxin B (80,000 IU/liter), and vancomycin (2 mg/liter). Prior to experimental work the classification of the L. longbeachae isolates was confirmed using molecular methods developed in this laboratory (21, 29) (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Legionella strain | Description (geographic originf) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strains | ||

| 130b | ATCC BAA-74; Wadsworth strain | 27 |

| Corby | Clinical isolate | 18 (obtained from J. Helbig) |

| L. longbeachae serogroup 2 | ATCC 33484; Tucker 1 strain | ATCCa (5) |

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 (O)cd | ATCC 33462; type strain (Long Beach 4) | ATCC (24) |

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 (R)ce | ATCC 33462; type strain (Long Beach 4) | ATCC |

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains | ||

| A5H5 | Clinical isolate (QLD, Australia) | 12 |

| A4C5 | Clinical isolate (SA, Australia) | This study |

| A5H3 | Clinical isolate (QLD, Australia) | This study |

| A5E1 | Clinical isolate (VIC, Australia) | This study |

| L6C9 | Environmental isolate (SA, Australia) | This study |

| K5H9 | Environmental isolate (QLD, Australia) | This study |

| K4A1 | Environmental isolate (SA, Australia) | This study |

| K8B9 | Environmental isolate (WA, Australia) | This study |

| Atlanta-5 | Clinical isolate (United States) | CDCb (2) |

| LA-24 | Clinical isolate (United States) | CDC (2) |

| D-63 | Clinical isolate (Ohio) | CDC |

| D-493 | Clinical isolate (California) | CDC |

| D-880 | Clinical isolate (Massachusetts) | CDC |

| D-1056 | Clinical isolate (New Mexico) | CDC |

| D-1624 | Clinical isolate (Israel) | CDC |

| D-1750 | Clinical isolate (Georgia) | CDC |

| D-1959 | Clinical isolate (Ohio) | CDC |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. Obtained from Robert Benson.

Possibly laboratory attenuated.

O, original isolate of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 ATCC 33462 (Long Beach 4), obtained in 1987.

R, recently obtained isolate of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 ATCC 33462 (Long Beach 4), obtained in 1997.

Abbreviations of Australian states: QLD, Queensland; SA, South Australia; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Infection of guinea pigs.

Outbred guinea pigs, IMVS colored stock (Veterinary Services, Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science [IMVS], Gilles Plains, South Australia, Australia), weighing between 200 and 700 g were inoculated via the aerosol route essentially as described previously (12). The test suspension of Legionella organisms was prepared from a 48-h CYE plate of growth in sterile tap water. A dose of approximately 109 organisms total was used for each test strain exposure. The actual number of organisms in the dose was determined retrospectively by serial 10-fold dilution in sterile tap water. In some aerosol experiments, the actual numbers of Legionella organisms that had been retained in the lungs of exposed guinea pigs were determined as described previously (12). After exposure, the animals were removed and placed in cages with only animals exposed to the same Legionella strain. The animals were checked two to three times daily for signs of illness, and weights were recorded. Animals were monitored for 7 days after exposure, and results were recorded on a separate work sheet for each animal in the test group. Symptoms noted included: activity (lethargy), signs of labored breathing, food intake, and water consumption. Animals that were very sick, as evidenced by extreme lethargy and labored breathing, determined as unlikely to survive more than a few hours, were euthanatized as a requirement of the IMVS animal ethics committee (policy approval no. 27/96).

Infection of macrophage-like U937 cells.

U937 cells are a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line that differentiate into nondividing, glass-adherent cells with the phenotypic characteristics of macrophages, when treated with phorbol esters (41). To assess the relative infectivity of L. longbeachae strains for U937 cells, 50% infective doses (ID50) were determined. The ID50, defined as the minimum inoculum size that yielded intracellular L. longbeachae in 50% of the inoculated monolayers, was determined using previously published methods (9, 28). The ID50 was determined, after 72 h of incubation, and calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (9, 32).

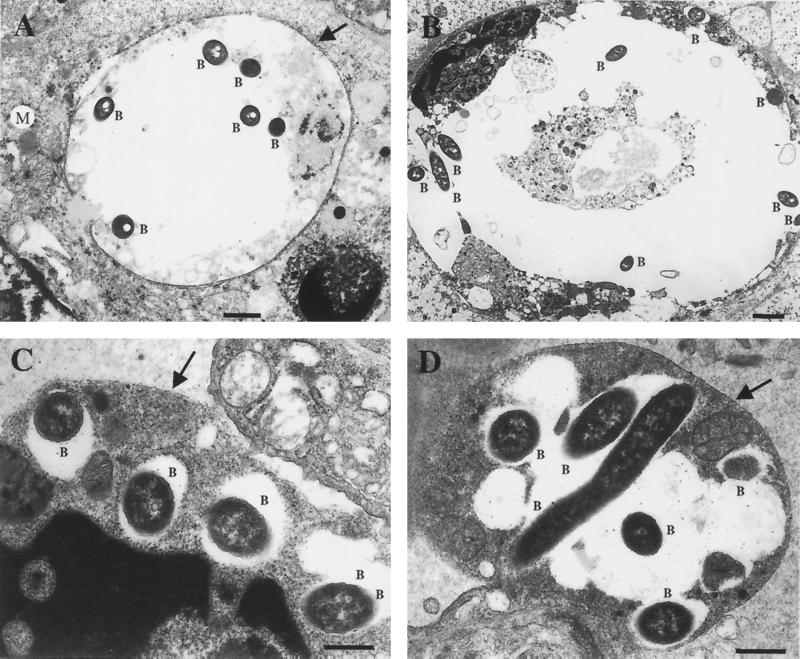

Electron microscopy.

L. longbeachae serogroup 1 ATCC 33462, an avirulent strain that is possibly laboratory attenuated, and a highly virulent Australian clinical isolate, strain A5H5, were chosen for examination by electron microscopy to determine the nature of intracellular infection of this species. The strains were inoculated into one guinea pig each, using the aerosol model of infection, with a standardized dose of 109 organisms as outlined above. At day 3 postinfection, the guinea pigs were euthanatized and the lungs were removed and placed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. Sections were prepared for transmission electron microscopy as follows. Briefly, lungs were postfixed by immersion in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 h, and this was followed by dehydration in methanol and infiltration and embedding in Spurr's epoxy resin. Survey sections (0.5 μm) were stained with toluidine blue and scanned by light microscopy to define areas containing bacteria for ultrastructural examination. Ultrathin sections (0.1 μm) were then cut, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined in a JEOL1200EXII transmission electron microscope.

RESULTS

Assessment of virulence of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains using an aerosol model of infection.

Strains of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 were assessed for their ability to cause disease in five guinea pigs exposed to a dose (approximately 109 organisms) of each test strain. On average, approximately 105 organisms are retained in the lungs when a test dose of 109 organisms is used (12). This was confirmed by measurement of retained doses in experiments conducted at various points in time (data not shown). Results for each isolate were plotted as percentage of weight gain or loss for each animal versus number of days after exposure. The results were compared to each other and to a similarly generated plot for a strain of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 (Corby) (18) and L. longbeachae serogroup 1 ATCC 33462.

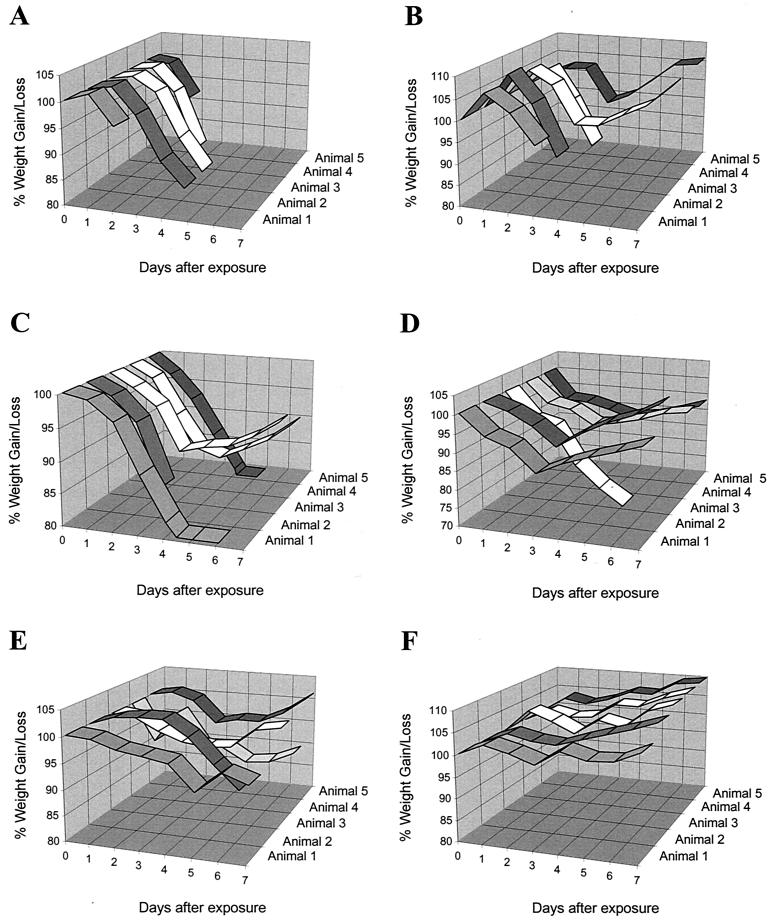

The Corby strain of L. pneumophila is a highly virulent isolate that produces a severe disease in guinea pigs. Infection with this strain caused rapid weight loss and death in 4 days or less for all five test animals (Fig. 1A). A similar severe infection was observed for L. pneumophila (Philadelphia-1) (12). Strains of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 showed differences in their ability to cause disease in this model of infection based on number of deaths and the severity of the disease, as shown by weight loss and time to death (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Percentage of weight gain or loss in guinea pigs exposed to an aerosol of different strains of Legionella. Guinea pig death is indicated by termination of the ribbon graph prior to the end of the experiment at day seven. Animals were exposed to a test dose of approximately 109 CFU and were classified into virulence groups according to the severity of the disease produced. Statistical groupings were assigned based on time to death using the SAS statistical package version 6 (SAS Institute Inc.). Type 1 L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains were highly virulent. The mean number of days before death occurred ranged from 4 to 5.8. The disease produced was similar to that observed for strains of L. pneumophila and a representative graph of infection with the Corby strain is shown (A). L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strain A5H5 (B), K4A1, K8B9, A5E1, D-880, and D-493 clustered in this group. Type 2 strains were moderately virulent strains. The mean number of days before death occurred ranged from 6.4 to 7.6. L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strain K5H9 (C), A5H3 (D), A4C5, L6C9, Atlanta-5, D-63, and D-1750 clustered in this group. Type 3 classified strains were relatively avirulent strains and generally were unable to kill any animals, although one strain killed one animal. The mean number of days before death determined for this group was 7.8 to 8. L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains D-1624, LA-24 (E), D-1056, and D-1959 (F) clustered in this group.

Cluster analysis based on the total number of animals killed by each test strain of L. longbeachae defined three statistically significant groupings, classified as type 1, 2, or 3. Type 1 strains killed four or five guinea pigs and included one non-Australian isolate (D-493) and an Australian isolate (K8B9). Type 2 strains were of moderate virulence and killed two to three animals in each test group. Five Australian isolates clustered in this category (A5E1, A5H5, K5H9, L6C9, and K4A1) as well as two non-Australian isolates (Atlanta-5 and D-880). Type 3 strains were avirulent or killed only one guinea pig and represented the least virulent cluster grouping based on number of animals killed. Interestingly, six non-Australian strains of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 clustered in this group (LA-24, D-1959, D-1056, D-1624, D-63, and D-1750) as well as two Australian isolates (A5H3 and A4C5), both of which killed one guinea pig each. The type strain L. longbeachae serogroup 1 (ATCC 33462) would also be included in the type 3 cluster by default, as both the original stock (obtained in 1987) and the more recent stock (obtained in 1997) are unable to establish clinical disease even at doses as high as 1010 (12) (see Table 3). All Australian isolates tested were able to cause disease and death in this animal model. Fisher's exact test (two tailed) also confirmed that the groups defined by the cluster analysis were statistically different from each other (P = 5.36 × 10−7).

TABLE 3.

Analysis of virulence of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains in a guinea pig model of infection

| Strain | Origin | Dose (CFU)a | Commentb | No. of deaths/no. of guinea pigs | Day(s) when deaths occurred | Classificationc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 33462 (R)d | United States | 1 × 1010 | No symptoms | 0/3 | Type 3 | |

| LA-24 | United States | 5.5 × 109 | No symptoms | 0/5 | Type 3 | |

| D-1056 | United States | 7.5 × 108 | All animals symptomatic | 0/5 | Type 3 | |

| D-1624 | Israel | 1.5 × 109 | No symptoms | 0/5 | Type 3 | |

| D-1959 | United States | 3.5 × 109 | Animal that died symptomatic | 1/5 | 6 | Type 3 |

| D-63 | United States | 1.32 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 1/5 | 3 | Type 2 |

| D-1750 | United States | 8.9 × 108 | Some animals symptomatic | 1/5 | 4 | Type 2 |

| Atlanta-5 | United States | 1.4 × 109 | Animals that died symptomatic | 2/5 | 4 | Type 2 |

| A5H3 | Australia | 1.4 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 1/5 | 5 | Type 2 |

| A4C5 | Australia | 1.2 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 1/5 | 3 | Type 2 |

| K5H9 | Australia | 1 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 3/5 | One each at days 3, 5 and 6 | Type 2 |

| L6C9 | Australia | 1.54 × 109 | Some animals symptomatic | 2/5 | 3 | Type 2 |

| A5E1 | Australia | 1.3 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 3/5 | 3 | Type 1 |

| A5H5 | Australia | 1.3 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 3/5 | 3 | Type 1 |

| K8B9 | Australia | 2 × 109 | Symptoms only in survivor | 4/5 | 3 | Type 1 |

| K4A1 | Australia | 1.6 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 3/5 | 3 | Type 1 |

| D-880 | United States | 1.2 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 3/5 | Two at day 3, one at day 4 | Type 1 |

| D-493 | United States | 1.9 × 109 | All animals symptomatic | 5/5 | 3 | Type 1 |

Dose of test strain placed in the nebulizer bowl.

Symptoms include change in activity, change in food or water consumption, and labored breathing. Weight change was observed for every animal irrespective of avirulence and hence is not considered here.

Cluster analysis groupings based on mean time to death.

See Table 1, footnote e.

Further analysis of the raw data suggested that some virulent strains, defined above, killed the test animals more rapidly than others even though the total number of dead animals was the same for each. Therefore, mean time to death was also assessed as a variable for statistical grouping of L. longbeachae strain virulence, using cluster analysis (Table 2). Mean time to death is a suitable variable of analysis due to the low numbers of guinea pigs exposed (five in each test group) and also because this variable captures severity of the outcome of the experiment. Cluster analysis defined four groupings; however, cluster four contained only one strain, D-493. For simplicity of comparison strain D-493 was defined as a type 1 strain, as are cluster three strains, as statistical analysis using total number of animals killed as a variable suggested a type 1 classification for this isolate (see above). Thus, the three virulence groupings observed using mean time to death as a variable were similar to that observed using number of animals killed. Type 1 strains were highly virulent, with a mean number of days to death ranging from 4 to 5.8 (Table 2). The onset of death in some animals was very sudden, and the severity of disease was similar to that produced by strains of L. pneumophila, which would also fall into this category based on these criteria (Fig. 1A) (12). Type 2, moderately virulent strains, caused death of test animals after a mean number of days ranging from 6.4 to 7.6. The last category, type 3 strains, had a mean time to death of 7.8 to 8 days. The Wilcoxon rank sum test determined that the clusters (1, 2, and 3, or three of the four combined) were statistically significantly different from each other, with P values of 0.0187 (C1 versus C2), 0.0001, (C1 versus C3), and 0.0001 (C2 versus C3). The Wilcoxon rank sum test is a nonparametric test and was used because the time-to-death data were not normally distributed, and therefore the assumptions of parametric tests such as the t test are not met (or are violated). The same groupings were seen using median time to death as a variable for nonnormally distributed data.

TABLE 2.

Cluster analysis groupings based on mean time to death

| Cluster | Time to death (day)

|

Grouping | Origin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Meana | Medianb | SDc | |||

| 1 | LA-24 | 8 | 8 | 0.00000 | Type 3 | United States |

| D-1056 | 8 | 8 | 0.00000 | Type 3 | United States | |

| D-1624 | 8 | 8 | 0.00000 | Type 3 | Israel | |

| D-1959 | 7.8 | 8 | 0.44721 | Type 3 | United States | |

| 2 | D-63 | 7.2 | 8 | 1.78885 | Type 2 | United States |

| D-1750 | 7.4 | 8 | 1.34164 | Type 2 | United States | |

| Atlanta-5 | 6.8 | 8 | 1.64317 | Type 2 | United States | |

| A5H3 | 7.6 | 8 | 0.89443 | Type 2 | Australia | |

| A4C5 | 7.2 | 8 | 1.78885 | Type 2 | Australia | |

| K5H9 | 6.6 | 7 | 1.67332 | Type 2 | Australia | |

| L6C9 | 6.4 | 8 | 2.19089 | Type 2 | Australia | |

| 3 | A5E1 | 5.6 | 4 | 2.19089 | Type 1 | Australia |

| A5H5 | 5.6 | 4 | 2.19089 | Type 1 | Australia | |

| K8B9 | 4.8 | 4 | 1.78885 | Type 1 | Australia | |

| K4A1 | 5.6 | 4 | 2.19089 | Type 1 | Australia | |

| D-880 | 5.8 | 5 | 2.04939 | Type 1 | United States | |

| 4 | D-493 | 4 | 4 | 0.00000 | Type 1 | United States |

The mean number of days before death due to that strain occurred.

The median number of days before death due to that particular strain.

Standard deviation based on the mean number of days until death.

L. longbeachae strain classification of virulence type, based on mean-time-to-death variable cluster analysis, is summarized with the aerosol experiment results in Table 3.

Infectivity of L. longbeachae strains in U937 cells.

ID50s were determined at 72 h postinfection, for empirically selected strains of L. longbeachae, in a U937 model of infection (Table 4) (9). Two infections were set up for each test strain, although a result was not achieved in duplicate for two strains, K4A1 and ATCC 33462. An L. pneumophila positive control (strain 130b) was also set up in each experiment, as it is well established that this strain can replicate efficiently in U937 cells (8, 11, 27, 28).

TABLE 4.

Infectivities of Legionella for U937 cells

| Species | Strain | ID50a | Virulence in guinea pigs | Typeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 (O)cd | ATCC 33462 Long Beach 4 | 4.55 ± 0.13 | Avirulent | 3 |

| L. longbeachae serogroup 2c | ATCC 33484 | 4.62 ± 0.27 | Avirulent | 3 |

| 5.60 ± 0.28 | ||||

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 | A5H3 | 2.20 ± 0.25 | One of five died | 2 |

| 2.88 ± 0.28 | ||||

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 | A4C5 | 1.36 ± 0.10 | One of five died | 2 |

| 2.70 ± 0.42 | ||||

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 | L6C9 | 3.08 ± 0.14 | Two of five died | 2 |

| 2.85 ± 0.15 | ||||

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 | K5H9 | 2.53 ± 0.13 | Three of five died | 2 |

| 4.00 ± 0.0 | ||||

| L. pneumophila serogroup 1 | 130b | 2.73 ± 0.13 | Virulent | 1 |

| 3.08 ± 0.28 | ||||

| 2.04 ± 0.19 | ||||

| 2.38 ± 0.18 | ||||

| 3.00 ± 0.28 | ||||

| 3.10 ± 0.13 | ||||

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 | A5H5 | 2.60 ± 0.28 | Three of five died | 1 |

| 3.14 ± 0.10 | ||||

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 | A5E1 | 3.20 ± 0.25 | Three of five died; rapid death | 1 |

| 3.30 ± 0.0 | ||||

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 | K8B9 | 2.27 ± 0.30 | Four of five died; rapid death | 1 |

| 2.30 ± 0.0 | ||||

| L. longbeachae serogroup 1 | K4A1 | 3.08 ± 0.30 | Three of five died | 1 |

The ID50 is expressed as a log value ± the standard deviation (expressed as a log value). Values for different infections are shown for each strain if available.

Virulence grouping based on mean-time-to-death cluster analysis data (Table 2).

Possibly laboratory attenuated.

See Table 1, footnote d.

L. pneumophila (130b) was able to infect the U937 cells exhibiting an ID50 of <1,200 bacteria (Table 4), consistent with previously published observations (27, 28). All of the Australian isolates of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 were infective for U937 cells and had ID50s that were comparable to each other and to those of L. pneumophila (130b), with the exception of strain K5H9 (Table 4). Strain K5H9 had a variable infectivity, with an ID50 of 102 bacteria in one infection and 104 in a replicate test (Table 4). Interestingly, this strain killed three of five guinea pigs in the aerosol model but grouped as a type 2 strain based on time to death. This may reflect the slower-progressing disease caused by this organism, which may be related to its ability to establish infection in macrophages. The L. longbeachae ATCC 33462 (serogroup 1) and ATCC 33484 (serogroup 2) type strains both appeared incapable of intracellular growth (Table 4). High ID50s of 104 bacteria suggest that the strains are impaired for intracellular replication within U937 cells (27). The result does not preclude the possibility, however, that these isolates may still be capable of surviving within the U937 cells. In general, the ability of Australian isolates of L. longbeachae to infect U937 cells correlated well with their ability to cause disease in an animal model of infection (Table 4).

Transmission electron microscopy analysis of lung tissue infected with L. longbeachae serogroup 1.

In mammalian and protozoan host cells, L. pneumophila serogroup 1 replicates intracellularly in a specialized phagosome surrounded by host cell rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (1, 15, 42). Electron microscopy of L. longbeachae serogroup 1-infected lung tissue was therefore undertaken to determine the intracellular location of this species. Lungs were taken from guinea pigs 3 days postinfection with L. longbeachae serogroup 1, strains ATCC 33462 and A5H5, and hence sections were not representative of a particular stage of infection.

Phagosomes containing the virulent A5H5 strain were observed in macrophages by electron microscopy (Fig. 2A and B). Some phagosomes appeared quite large in relation to the total size of the macrophage and contained several bacteria (Fig. 2B). Mitochondria and host cell organelles were seen in close proximity to the phagosomes containing the bacteria, and the membrane appeared to be surrounded by electron-dense structures (ribosomes) (Fig. 2A). Phagosomes containing several A5H5 bacteria (Fig. 2B) were also seen and may be representative of later stages of infection. The membrane of these potential later-stage vacuoles did not appear to be surrounded with ribosomes but generally appeared to be associated with host cell organelles.

FIG. 2.

Electron micrograph showing the intracellular location of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains. Lungs were taken from a guinea pig infected with strains ATCC 33462 and A5H5, 3 days after exposure. (A) L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strain A5H5 bacteria (B) observed in a membrane bound vacuole within a macrophage. Potential ribosome studding of the vacuole membrane is shown by an arrow. Host organelles such as mitochondria (M) appear associated with the vacuole. Magnification, ×9,540; bar, 1 μm. (B) Ultrathin sections of a vacuole containing several A5H5 bacteria. Magnification, ×6,360; bar, 1 μm. (C) Macrophage with four membrane vacuoles, each containing one L. longbeachae serogroup 1 ATCC 33462 bacterium. Magnification, ×23,850; bar, 0.5 μm. The arrow indicates the macrophage membrane. (D) Phagosome within a macrophage containing several ATCC 33462 bacteria. The membrane of the vacuole appears smooth walled. Magnification, ×19,875; bar, 0.5 μm. The arrow indicates the phagosome membrane.

The attenuated avirulent ATCC 33462 L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strain was also found in phagosomes in macrophages (Fig. 2C and D). Figure 2C may represent an early event just after uptake of the bacteria into the macrophage cell with four phagosomes, each containing a single bacterium. Figure 2D could represent a later stage of infection in which several phagosomes have fused to form one large phagosome, containing a few bacteria, or it may depict replication of the bacteria. Sections were prepared from lungs removed at day 3 of the infection, making it difficult to distinguish between these two scenarios. The vacuole containing these bacteria was surrounded by a smooth membrane that did not appear to be associated with any host organelles or ribosomes. Association of phagosomes with host cell organelles and ribosomes was not apparent in any of the fields examined (data not shown). Large vacuoles containing several bacteria, observed for the A5H5 strain, were not seen with ATCC 33462. In general, phagosomes containing the ATCC 33462 strain were small and relatively clear in comparison with those containing the virulent A5H5 strain. Strain A5H5 was generally associated with larger phagosomes that contained several bacteria and that also appeared to contain cellular debris.

DISCUSSION

Statistical analysis of the raw animal experiment data determined three L. longbeachae serogroup 1 virulence types based on the ability of the organism to cause disease in experimentally infected guinea pigs. Initially, change in weight (weight difference) was thought to be a good predictor of virulence of a particular strain, as it is a symptom that can be easily measured and recorded. However, statistical cluster analysis of weight differences did not distinguish avirulent strains, which did not kill test animals, from those that were clearly virulent as evidenced by death of more than half of the animals in the test group (data not shown). Strains that killed test animals quickly would not allow time for a large weight loss to occur and hence would not be distinguished from those strains that did not produce severe weight loss symptoms and were avirulent. The results indicated that weight difference was not a good indicator of overall virulence of a particular strain of L. longbeachae, although it was a good indicator of overall health of the animal.

Statistical cluster analysis using mean time to death as a variable was used to classify L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains into three virulence types. Type 1, highly virulent strains, rapidly killed most animals in the test group, and the majority of isolates in this category were from Australia, although two non-Australian isolates also fell into this group. Type 2 strains killed fewer animals and caused a slower-progressing disease than did type 1 strains and the remaining Australian isolates grouped in this category, as did three non-Australian isolates. Type 3 strains were mostly avirulent and were unable to cause disease, although one strain that killed one animal on day 6 also fell into this category. This group contained only non-Australian isolates. No Australian isolate tested was avirulent in the aerosol model.

U937 infection studies indicated that the Australian isolates of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 were capable of infecting these cells at levels comparable to L. pneumophila and other virulent species. The results with our original ATCC 33462 type strain in this model of infection are in contrast to those of O'Connell et al., who showed that this same strain (Long Beach 4) was able to infect U937 cells, with an ID50 of <1,000 bacteria (27). It is unusual for a strain to be capable of infecting macrophages and unable to cause disease in an animal model of infection (27). The result suggested that the original ATCC 33462 isolate had become attenuated. A more recent stock of ATCC 33462 type strain was purchased and tested to ensure that the original stock had not become laboratory attenuated. The recent stock was also avirulent in the guinea pig animal mode, even with a test dose of 1010 organisms (Table 3). Postmortem examination of the lungs determined that small foci of infection were evident, although these did not appear to manifest themselves through other symptoms. The L. longbeachae serogroup 2 ATCC type strain is also avirulent in the animal model (12). The recently obtained stock of ATCC 33462 (obtained in 1997) was not assessed in U937 cells. Interestingly, the ATCC 33462 type strain has been tested in macrophage-like Mono Mac 6 cells by other workers, who found that it was unable to replicate in this cell type (25). It is possible that some strains of L. longbeachae may be more sensitive to attenuation resulting from delayed storage or freeze-drying processes, factors more likely to occur when cultures are sent to overseas laboratories. The passage history of isolates and laboratory attenuation is an important factor in the interpretation of results of this study. However, all isolates used were stored immediately, and the freshest subculture was used in all experiments. Additionally the presence of virulent isolates among the non-Australian strains argues against laboratory attenuation of virulence. Overall, the U937 model results were consistent with the animal model data, as strains that could infect the U937 cells were also capable of causing disease in this aerosol model. However, the results also support the idea that virulence is a multifactorial process and in probability involves more than just the ability to infect macrophage cells; therefore, this alone may not necessarily be a good indicator of the pathogenic capability of a particular strain.

The incidence of disease due to L. longbeachae serogroup 1 in Australia may, in part, be due to the inherent virulence of Australian isolates in comparison with those from elsewhere. The animal model data suggest that Australian strains may be inherently more virulent than overseas isolates. Statistical cluster analysis showed a strong trend for a higher proportion of Australian isolates to fall into virulent groups while the relatively avirulent grouping contained only non-Australian isolates. Whether this is a true reflection of inherent virulence in the Australian isolates is difficult to ascertain. The groupings are reflections of trends in the data and are by no means exact, due to the small number of animals tested for each strain and the relatively small number (n = 18) of isolates tested. Factors that may influence these groupings may be variations in the test dose administered and the innate resistance of the outbred guinea pigs used in the study, thus influencing disease outcome.

Alternatively, other factors may influence the increased incidence of disease due to L. longbeachae serogroup 1 in Australia. Differences in the components and manufacture processes of potting mix elsewhere in comparison with Australia may play a role. L. longbeachae serogroup 1 has been shown to principally reside in potting soil rather than water (38). It has been found in potting mixes and the waste wood products of Australian samples but not in potting mixes obtained from Europe and the United Kingdom (39). Soil surveys for Legionella have not been conducted in the United States (7), although a recent report suggests transmission from potting soil has occurred for the first time in the United States (7). L. longbeachae serogroup 1 and other Legionella species have been found in potting mixes, in composted plant matter from home gardens, and in bulk composting depots (16). Temperatures in the composting heaps were within the optimal range (25 to 35°C) for the multiplication of soil Legionella. Hence, composting may be an important step in the amplification of Legionella species in the environment (16, 34). It has been proposed that the relative rarity of infection due to L. micdadei, in comparison with L. pneumophila, may be due, in part, to differences in growth kinetics in the environment rather than to a genuine difference between the two species (4). Climatic and industry-related conditions in Australia may favorably influence the numbers of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 species in the environment. Increased incidence of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 in Australia may also be a reflection of increased surveillance for this species in Australia in comparison with elsewhere. It has been proposed that legionellosis is underreported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, due to failure to obtain the appropriate diagnostic tests in cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology, difficulty of culturing Legionella from clinical specimens, and difference in state protocols regarding reporting of disease due to this organism (7).

Very little is known about the intracellular life cycle of L. longbeachae and what factors contribute to pathogenesis. These factors may be shared with L. pneumophila and other species of Legionella or they may be unique. L. micdadei shares some virulence features with L. pneumophila, such as Mip (26) and flagella (3), but the former is not taken up by coiling phagocytosis (31) and does not appear to replicate in a specialized phagosome associated with the host ER (46). A recent comparative study of virulence traits of L. pneumophila and L. micdadei has also determined that the two species also appear to use distinct mechanisms to parasitize macrophages (19).

As an initial approach to understanding the intracellular nature of pathogenesis of L. longbeachae serogroup 1, transmission electron microscopic examination of infected lung tissue was undertaken. The data were difficult to interpret as the sections were taken from infected lung tissue and not from macrophage cells infected in vitro. Under in vitro conditions, various stages of infection can be examined and compared with each other. In these experiments lungs were taken from infected animals three days after exposure and hence may reflect all stages of infection together with the immunogenic response of the guinea pig to infection.

Relatively few ATCC 33462 bacteria were seen in comparison to A5H5, most likely due to clearance of bacteria from the lung, since this strain is avirulent in an animal model (12). Strain ATCC 33462 was also found in phagosomes that differed morphologically from those containing the virulent A5H5 strain since they were small, did not appear associated with host cell organelles and often contained a single bacterium. In contrast phagosomes containing the virulent A5H5 strain appeared to be associated with host cell organelles and in some cases were surrounded by electron dense structures. This observation was in agreement with the results of a recent publication by Gerhardt et al. that determined L. longbeachae serogroup 1 ATCC 33462 is able to induce ribosome studded phagosomes in Mono Mac 6 cells that associate with the host cell rough ER (14). The results for the ATCC 33462 type strain, L. longbeachae serogroup 1 in this study, while in contrast to those of Gerhardt et al., are not surprising, as our stock of this isolate is unable to cause disease in an animal model of infection and hence is unlikely to be competent for intracellular growth within macrophages. In conclusion, the data suggest that virulent strains of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 replicate in a specialized phagosome in a manner similar to L. pneumophila serogroup 1 (1, 15, 42).

However, our observation of large vacuoles containing several A5H5 bacteria that appeared to be filled with debris and did not show any significant ribosome studding was in conflict with this postulate. The morphology of these large vacuoles suggested that they represented phagosomes that had fused with host cell lysosomes. The vacuoles appeared to contain much debris, possibly due to uptake of cellular debris by the macrophage. Lungs taken from animals infected with strain A5H5 exhibit severe damage and consolidation, suggesting that this is likely (12). In addition the bacteria within these large vacuoles did not appear to be damaged, further suggesting that virulent strains of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 may survive and multiply within phagosomes that have fused with lysosomes. It is known that L. micdadei multiplies in macrophages in phagosomes that do not associate with host cell ribosomes and that fuse with lysosomes (31, 46). Therefore, our observations also suggest that L. Longbeachae serogroup 1 strains might replicate in a phagolysosome similar to that reported for L. micdadei (46). However, recent studies focusing on the replication phase of the L. pneumophila intracellular life cycle have shown that vacuoles containing this pathogen accumulate lysosomal markers as they develop, suggesting that the organism is delivered to a lysosomal compartment during intracellular replication and hence survives in lysosomal vacuoles (40). The same authors also noted that vacuoles containing replicating L. pneumophila organisms that were more than 24 h old frequently contained granular and membranous material indicative of a phagolysosomal existence for the bacteria, consistent with our observations (40). Therefore, the intracellular life cycle of L. longbeachae is more closely aligned with that of L. pneumophila than that of L. micdadei. This model fits well with the animal model data, which suggest that this strain of Legionella is potentially as virulent as L. pneumophila, while L. micdadei primarily infects immunocompromised hosts and is less virulent in animal and cell culture models of infection (19).

The study highlights the need to study other species of Legionella as well as multiple strains within species. It has been proposed, based on U937 infection studies, that one isolate of a given species judged as noninfective does not mean that all strains within that species are noninfective (27), consistent with our findings. The results of the animal studies are of interest as previous studies with L. longbeachae serogroup 1 suggest that it is remarkably clonal (21, 30), which is in disagreement with the range of virulence observed in this study with this species. A more detailed analysis of L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strains may reveal factors that are unique to type 1 strains and are lacking in less virulent type 2 and 3 isolates. Work is in progress to elucidate the intracellular lifestyle of L. longbeachae and the factors, other than Mip (12), that may be important in pathogenesis of this species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Rebecca Cooper Medical Research Foundation and the Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Medical Research Foundations for assistance with the purchase of laboratory equipment.

We also thank Nicole Chamberlain, Department of Public Health, University of Adelaide, for statistical analysis of the animal model data and helpful discussions. Thanks also go to Peter Sutton-Smith (Division of Tissue Pathology, IMVS) for preparation of sections for transmission electron microscopy and for helpful discussions and to Robert Benson from the CDC for the L. longbeachae strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu Kwaik Y. The phagosome containing Legionella pneumophila within the protozoan Hartmannella vermiformis is surrounded by the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2022–2028. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2022-2028.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aye T, Wachsmuth K, Feeley J C, Gibson R J, Johnson S R. Plasmid profiles of Legionella species. Curr Microbiol. 1981;6:389–394. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangsborg J M, Hindersson P, Shand G, Hoiby N. The Legionella micdadei flagellin: expression in Escherichia coli K 12 and DNA sequence of the gene. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 1995;103:869–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Best M G, Stout J E, Yu V L, Muder R R. Tatlockia micdadei (Pittsburgh pneumonia agent) growth kinetics may explain its infrequent isolation from water and the low prevalence of Pittsburgh pneumonia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1521–1522. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.6.1521-1522.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bibb W F, Sorg R J, Thomason B M, Hicklin M D, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J, Wulf M R. Recognition of a second serogroup of Legionella longbeachae. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;14:674–677. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.6.674-677.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron S, Roder D, Walker C, Feldheim J. Epidemiological characteristics of Legionella infection in South Australia: implications for disease control. Aust N Z J Med. 1991;21:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1991.tb03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legionnaires' Disease associated with potting soil—California, Oregon, and Washington, May-June 2000. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:777–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cianciotto N, Eisenstein B I, Engleberg N C, Shuman H. Genetics and molecular pathogenesis of Legionella pneumophila, an intracellular parasite of macrophages. Mol Biol Med. 1989;6:409–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cianciotto N P, Eisenstein B I, Mody C H, Toews G B, Engleberg N C. A Legionella pneumophila gene encoding a species-specific surface protein potentiates initiation of intracellular infection. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1255–1262. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1255-1262.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cianciotto N P, Eisenstein B I, Mody C H, Engleberg N C. A mutation in the mip gene results in an attenuation of Legionella pneumophila virulence. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:121–126. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowling J N, Saha A K, Glew R H. Virulence factors of the family Legionellaceae. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:32–60. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.32-60.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle R M, Steele T W, McLennan A M, Parkinson I H, Manning P A, Heuzenroeder M W. Sequence analysis of the mip gene of the soilborne pathogen Legionella longbeachae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1492–1499. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1492-1499.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fields B S, Barbaree J M, Shotts E B, Jr, Feeley J C, Morrill W E, Sanden G N, Dykstra M J. Comparison of guinea pig and protozoan models for determining virulence of Legionella species. Infect Immun. 1986;53:553–559. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.553-559.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerhardt H, Walz M J, Faigle M, Northoff H, Wolburg H, Neumeister B. Localization of Legionella bacteria within ribosome-studded phagosomes is not restricted to Legionella pneumophila. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;192:145–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horwitz M A. Formation of a novel phagosome by the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1983;158:1319–1331. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.4.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes M S, Steele T W. Occurrence and distribution of Legionella species in composted plant materials. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2003–2005. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.2003-2005.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izu K, Yoshida S, Miyamoto H, Chang B, Ogawa M, Yamamoto H, Goto Y, Taniguchi H. Grouping of 20 reference strains of Legionella species by the growth ability within mouse and guinea pig macrophages. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jepras R I, Fitzgeorge R B, Baskerville A. A comparison of virulence of two strains of Legionella pneumophila based on experimental aerosol infection of guinea-pigs. J Hyg (London) 1985;95:29–38. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400062252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi A D, Swanson M S. Comparative analysis of Legionella pneumophila and Legionella micdadei virulence traits. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4134–4142. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4134-4142.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koide M, Saito A, Okazaki M, Umeda B, Benson R F. Isolation of Legionella longbeachae serogroup 1 from potting soils in Japan. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:943–944. doi: 10.1086/520470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanser J A, Adams M, Doyle R, Sangster N, Steele T W. Genetic relatedness of Legionella longbeachae isolates from human and environmental sources in Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2784–2790. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2784-2790.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levi M H, Pasculle A W, Dowling J N. Role of the alveolar macrophage in host defense and immunity to Legionella micdadei pneumonia in the guinea pig. Microb Pathog. 1987;2:269–282. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim I L, Sangster N, Reid D P, Lanser J A. L. longbeachae pneumonia: report of two cases. Med J Aust. 1989;150:599–601. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb136700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKinney R M, Porschen R K, Edelstein P H, Bissett M J, Harris P P, Bondell S P, Steigerwalt A G, Weaver R E, Ein M E, Lindquist D S, Kops R S, Brenner D J. Legionella longbeachae species nova, another etiological agent of human pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:739–741. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-94-6-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumeister B, Schöniger S, Faigle M, Eichner M, Deitz K. Multiplication of different Legionella species in Mac 6 cells and in Acanthamoebae castellanii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1219–1224. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1219-1224.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connell W A, Bangsborg J M, Cianciotto N P. Characterization of a Legionella micdadei mip mutant. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2840–2845. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2840-2845.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connell W A, Dhand L, Cianciotto N P. Infection of macrophage-like cells by Legionella species that have not been associated with disease. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4381–4384. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4381-4384.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearlman E, Jiwa A H, Engleberg N C, Eisenstein B I. Growth of Legionella pneumophila in a human macrophage-like (U937) cell line. Microb Pathog. 1988;5:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratcliff R M, Lanser J A, Manning P A, Heuzenroeder M W. Sequence-based classification scheme for the genus Legionella targeting the mip gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1560–1567. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1560-1567.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ratcliff R M. Genetic and functional studies of the Mip protein of Legionella. Ph.D. thesis. Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rechnitzer C, Blom J. Engulfment of the Philadelphia strain of Legionella pneumophila within pseudopod coils in human phagocytes. Comparison with other Legionella strains and species. APMIS. 1989;97:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed L, Muench J. A simple method for estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reingold A L, Thomason B M, Brake B J, Thacker L, Wilkinson H W, Kuritsky J N. Legionella pneumonia in the United States: the distribution of serogroups and species causing human illness. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:819. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.5.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross I S, Mee B J, Riley T V. Legionella longbeachae in Western Australian potting mix. Med J Aust. 1996;166:387. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb123175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saint C P, Ho L. Legionella longbeachae isolated from water. Med J Aust. 1999;168:96. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb126736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Speers D J, Tribe A E. Legionella longbeachae pneumonia associated with potting mix. Med J Aust. 1994;161:509. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1994.tb127576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steele T W, McLennan A M. Infection of Tetrahymena pyriformis by Legionella longbeachae and other Legionella species found in potting mixes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1081–1083. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1081-1083.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steele T W, Lanser J, Sangster N. Isolation of Legionella longbeachae serogroup 1 from potting mixes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:49–53. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.1.49-53.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steele T W, Moore C V, Sangster N. Distribution of Legionella longbeachae serogroup 1 and other legionellae in potting soils in Australia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2984–2988. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.10.2984-2988.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Swanson M S. Legionella pneumophila replication vacuoles mature into acidic, endocytic organelles. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1261–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundstrom C, Nilsson K. Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U937) Int J Cancer. 1976;17:565–577. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swanson M S, Isberg R R. Formation of the Legionella pneumophila replicative phagosome. Infect Agents Dis. 1993;2:269–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van't Hullenaar N G, van Ketel R J, Kuijper E J, Bakker P J, Dankert J. Relapse of Legionella longbeachae infection in an immunocompromised patient. Neth J Med. 1996;49:202–204. doi: 10.1016/0300-2977(96)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wadowsky R M, Wilson T M, Kapp N K, West A J, Kuchta J M, States S J, Dowling J N, Yee R B. Multiplication of Legionella spp. in tap water containing Hartmannella vermiformis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1950–1955. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.7.1950-1955.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker C, Weinstein P. Review of Legionellosis in South Australia 1990–1999. Communicable Dis Intell. 1992;16:70–71. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinbaum D L, Benner R R, Dowling J H, Alpern A, Pasculle A W, Donowitz G R. Interaction of Legionella micdadei with human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1984;46:68–73. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.68-73.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]