Abstract

Corydalis saxicola Bunting (CSB), whose common name in Chinese is Yanhuanglian, is a herb in the family Papaveraceae. When applied in traditional Chinese medicine, it is used to treat various diseases including hepatitis, abdominal pain, and bleeding haemorrhoids. In addition, Corydalis saxicola Bunting injection (CSBI) is widely used against acute and chronic hepatitis. This review aims to provide up-to-date information on the botanical distribution, description, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and clinical applications of CSB. A comprehensive review was implemented on studies about CSB from several scientific databases, such as SciFinder, Elsevier, Springer, ACS Publications, Baidu Scholar, CNKI, and Wanfang Data. Phytochemical studies showed that 81 chemical constituents have been isolated and identified from CSB, most of which are alkaloids. This situation indicates that these alkaloids would be the main bioactive substances and that they have antitumour, liver protective, antiviral, and antibacterial pharmacological activities. CSBI can not only treat hepatitis and liver cancer but can also be used in combination with other drugs. However, the relationships between the traditional uses and modern pharmacological actions, the action mechanisms, quality standards, and the material basis need to be implemented in the future. Moreover, the pharmacokinetics of CSBI in vivo and the toxicology should be further investigated.

Keywords: botany, Corydalis saxicola, clinical applications, phytochemistry, pharmacology, traditional uses

1. Introduction

Corydalis saxicola Bunting (CSB), which is called Yanhuanglian in Chinese, is a species of Corydalis DC., is a genus in the family Papaveraceae. CSB is mainly distributed on rocky cliffs or in alpine caves in southwestern China, including Guangxi, Guizhou, Hubei, Shanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, Zhejiang [1]. CSB is a traditional Chinese folk medicine in southwestern China, where the bitter-tasting and cool-natured whole plant can be used as a medicine that has the effects of heat clearing and detoxification, damp elimination, pain alleviation, and haemostasis [2]. In tradition, the whole plant of CSB, namely Yan-huang-lian is used to cure diseases in Chinese folk. On the basis of traditional Chinese medicine theories, its use spectrum contains acute conjunctivitis, corneal pannus, acute abdominal pain, hemorrhoidal bleeding, haematochezia, swelling, hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer [3,4,5]. Until now, pharmacological studies have provided evidence that this ethnomedicine can treat liver diseases and show that it also has significant pharmacological properties such as anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-oxidative, analgesic, and hepatoprotective effects [6,7,8]. Clinically, Corydalis saxicola Bunting injection (CSBI) was approved for production in Guangxi in 1982 [1] and is the exclusive variety in production in China. In 2002, the national medicine standard (Z20026725) was obtained by landmark upgrading and national standard rectification. CSBI is clinically used for patients with acute and chronic hepatitis.

Although a large number of studies have been carried out on CSB, many aspects of CSB remain unclear, such as monomer component exploration, the establishment of quality standards, the mechanism of CSB therapeutic effects, and combination mechanism. Additionally, toxicological studies need to be strengthened to support its therapeutic safety. In this paper, the botanical properties, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, and clinical applications of CSB are reviewed. This review can provide a reference for deep research and application of this plant.

2. Database Search Method

This review of CBS on its botanical distribution and description, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activity, clinical applications, and toxicity assessment is based on a variety of reliable databases such as Scifinder, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Wiley, ACS, CNKI, Springer, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Baidu Scholar, as well as other published materials (Ph.D. and M.Sc. dissertations and books). The literature was searched and accessed using the keywords “Corydalis saxicola Bunting”, “Corydalis saxicola Bunting total alkaloids”, and “dehydrocavidine” which are related to the present review.

3. Botanical Distribution and Description

CSB can be found in southwestern China with a wide distribution in Chongqing (Chengkou), Guangxi (Debao, Fengshan, Jingxi), Guizhou (Dushan, Weng’an, Zunyi), Hubei (Yichang), Shanxi (Mianxian), Sichuan, Yunnan (Xichou), and Zhejiang (Ningbo), among other areas [9,10]. Notably, it is mainly distributed in western and northwestern Guangxi, especially Donglan, Bama, Du’an, Jingxi, and Debao. It has stringent requirements for environmental conditions and is produced in extremely low yield. The distribution of this plant is limited to limestone mountain areas and is a stone mountain endemic species. It grows primarily on rocky cliffs or in alpine caves at elevations of 600–1690 m, reaching 2800–3900 m in southwestern Sichuan, with a growth temperature of 15–25 °C [10,11,12].

CSB is a light green soft herb that can grow up to 30–40 cm high and has thick main roots and single to multi-headed rhizomes. The stems can be branched or unbranched. The branches are opposite to the leaves and are scape-shaped. The basal leaves are approximately 10–15 cm long with a long stalk, the leaves are approximately the same length as the petioles with two or one pinnate cleft, and the last pinnate is wedge-shaped to obovate, approximately 2–4 cm long and 2–3 cm wide, with unequal 2–3 splits or thick round teeth at the edges. The raceme is approximately 7–15 cm long, with many flowers that are first dense, then alienated. The bracts are elliptic to lanceolate, whole, and the lower part is approximately 1.5 cm long and 1 cm wide while the upper part narrows, all of which are longer than the pedicels. The length of the pedicel is approximately 5 mm. The flowers are golden yellow and flat. The sepals are like triangles, and in their entirety are approximately 2 mm long. The outer petals are wider and acuminate, and the coronal process is limited to the keel process but does not reach the top. The upper petals are approximately 2.5 cm long with the distance accounting for approximately 1/4 of the full length of the petals, slightly bent down, and the end is cystic. The lower petals are approximately 1.8 cm long, and the base looks like a small tumour protrusion. The inner petals are approximately 1.5 cm long, with a thick crown protruding from the top. The stamen bundles are lanceolate, tapering above the middle. The stigma is two-forked, with two cleft papillae at the top of each branch. The capsule is linear and recurved, approximately 2.5 cm long, with 1 row of seeds [10]. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The pictures of Corydalis saxicola Bunting.

4. Traditional Uses

As a type of folk medicinal herb in South China, various classical ancient Chinese books, including “Guizhou folk medicine”, “Traditional Chinese Medicine Dictionary”, “Chinese Materia Medica”, “Flora of Guangxi”, and “Flora of Yunnan”, have recorded the traditional medicinal uses of CSB. Based on the theory of traditional Chinese medicine, CSB has been widely used in the treatment of various diseases for a long time, such as heat clearance and detoxification, damp elimination, pain alleviation, haemostasis, erosion of the mucous membranes in the oral cavity, dysentery, eyes of fire, eye shade, diarrhoea, stomachache, bleeding haemorrhoids, hepatitis, jaundice, ascites, cirrhosis, and hepatoma [13,14,15,16]. For example, direct oral administration of 6 g of CSB is used to treat acute abdominal pain. For the treatment of pile ale bleeding and red dysentery, 15 g of CSB soaked in 50 g of steamed liquor is taken orally. In addition, CSB can be mixed with other medicines to treat diseases. For example, for the treatment of eyes of fire and eye shade, CSB (3 g), Gentiana scabra Bunge (3 g), and “Shang Mei Pian” (1.5 g) are ground together into powder, steamed in a porcelain cup, and finally dipped into the eye with a lantern. An injection containing the total alkaloids of CSB has a good effect on hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatoma [12,17]. CSB is mainly used orally (decoction, 3–15 g) and externally (put on the affected area after grinding in the appropriate amount). When using CSB, dry and spicy foods should be avoided. Due to diverse traditional and folk uses of it, CSB has been extensively studied by numerous chemists and biologists.

5. Phytochemistry

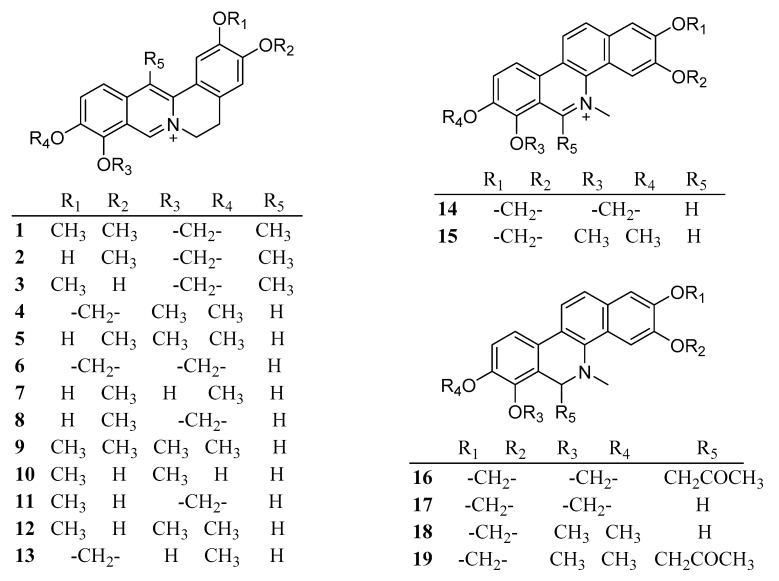

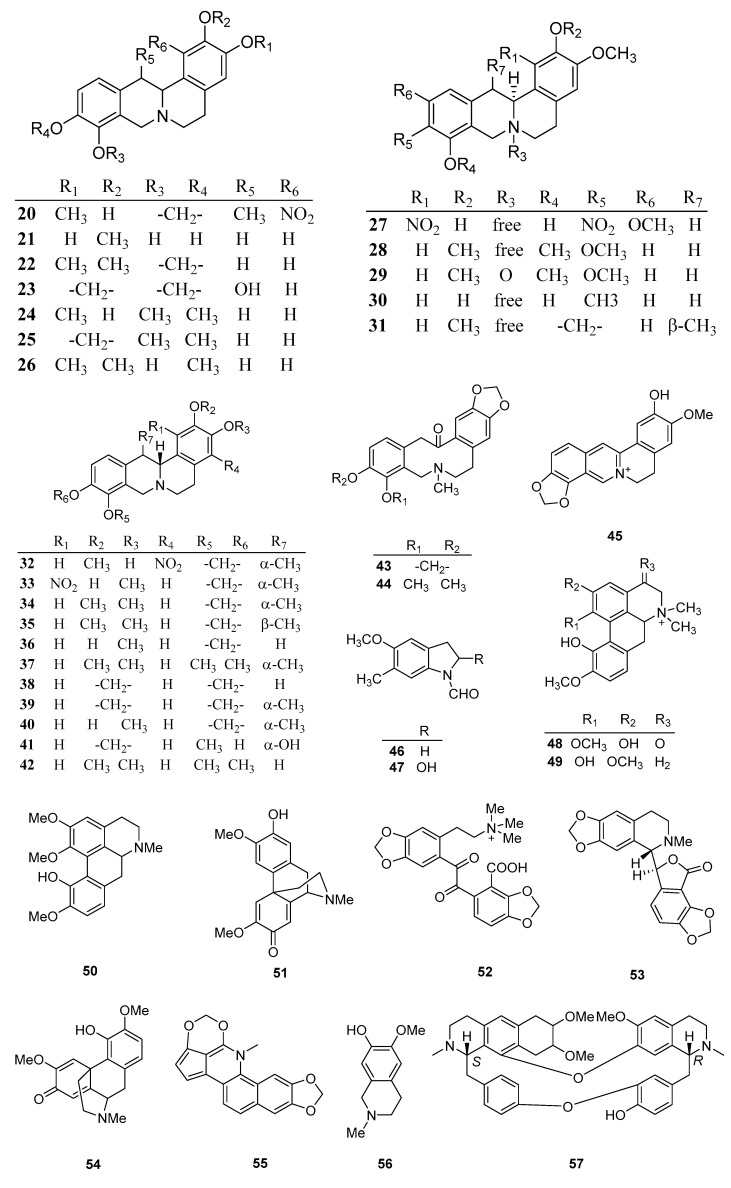

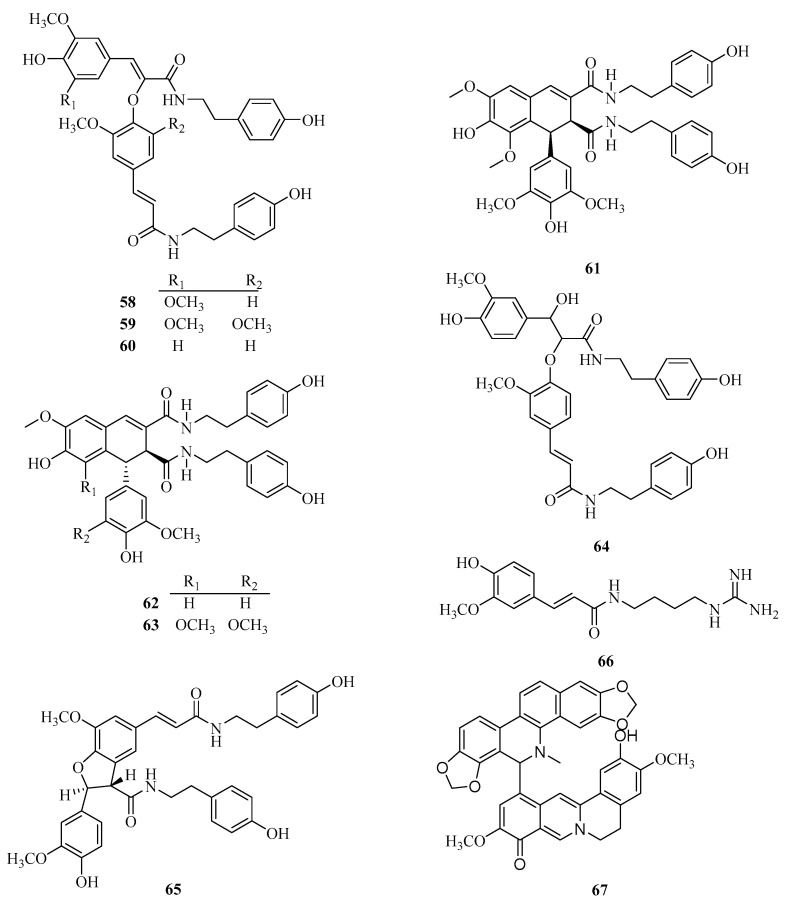

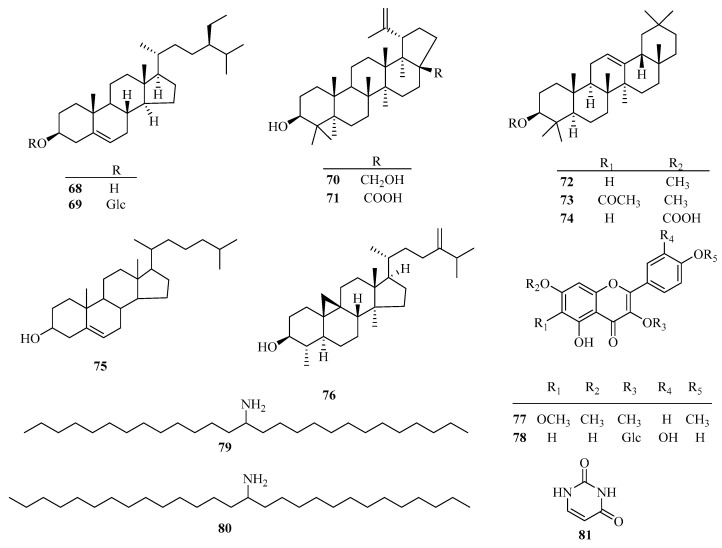

A research team from Guangxi in China reported on CSB in 1980. To date, 81 chemical components including alkaloids, steroids, and flavonoids, have been separated and identified from CSB (Table 1). The chemical structures of these 81 compounds are shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

The phytoconstituents isolated from Corydalis saxicola Bunting.

| NO. | Name | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight | Plant Parts | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dehydrocavidine | C21H20NO4 | 350.14 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 2 | dehydroapocavidine | C20H18NO4 | 336.12 | Root | [18] |

| 3 | dehydroisoapocavidine | C20H18NO4 | 336.12 | Whole plant | [15] |

| 4 | berberine | C20H18NO4 | 336.12 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 5 | dehydroisocorypalmine | C20H20NO4 | 338.14 | Whole plant | [15] |

| 6 | coptisine | C19H14NO4 | 320.09 | Root | [18] |

| 7 | tetradehydroscoulerine | C19H18NO4 | 324.12 | Whole plant | [15] |

| 8 | dehydrocheilanthifoline | C19H16NO4 | 322.11 | Whole plant | [19] |

| 9 | palmatine | C21H22NO4 | 352.15 | Root | [18] |

| 10 | dehydrodiscretamine | C19H18NO4 | 324.12 | Whole plant | [19] |

| 11 | thalifaurine | C19H16NO4 | 322.11 | Root | [18] |

| 12 | jatrorrhizine | C20H20NO4 | 338.14 | Whole plant | [13] |

| 13 | berberrubine | C19H16NO4 | 322.11 | Whole plant | [20] |

| 14 | sanguinarine | C20H14NO4 | 332.09 | Whole plant | [6] |

| 15 | chelerythrine | C21H18NO4 | 348.12 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 16 | 6-acetonyl-5,6-dihydrosanguinarine | C23H19NO5 | 389.13 | Root | [18] |

| 17 | dihydrosanguinarine | C20H15NO4 | 333.10 | Root | [18] |

| 18 | dihydrochelerythrine | C21H19NO4 | 349.13 | Root | [18] |

| 19 | 8-acetonyldihydrochelerythrine | C24H23NO5 | 405.16 | Whole plant | [6] |

| 20 | 1-nitro-apocavidine | C20H20N2O6 | 384.13 | Whole plant | [14] |

| 21 | 2, 9, 10-thrihydroxy-3-methoxytetrahydroprotoberberine | C18H19NO4 | 313.13 | Whole plant | [16] |

| 22 | sinactine | C20H21NO4 | 339.15 | Whole plant | [16] |

| 23 | (−)-13β-hydroxystylopine | C19H17NO5 | 339.34 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 24 | tetrahydrocolumbamine | C20H23NO4 | 341.16 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 25 | canadine | C20H21NO4 | 339.15 | Whole plant | [2] |

| 26 | tetrahydropalmatrubine | C20H23NO4 | 341.16 | Whole plant | [16] |

| 27 | (−)-2,9-dihydroxyl-3,11-dimethoxy-1,10-dinitrotetrahydroprotoberberine | C19H19N3O8 | 417.12 | Whole plant | [6] |

| 28 | (+)-tetrahydropalmatine | C21H25NO4 | 355.15 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 29 | (−)-corynoxidine | C21H25NO5 | 371.17 | Whole plant | [6] |

| 30 | (−)-scoulerine | C19H21NO4 | 327.15 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 31 | (−)-cavidine | C21H23NO4 | 353.16 | Root | [18] |

| 32 | (+)-4-nitroisoapocavidine | C20H20N2O6 | 384.13 | Whole plant | [6] |

| 33 | (+)-1-nitroapocavidine | C20H20N2O6 | 384.13 | Whole plant | [6] |

| 34 | (±)-cavidine | C21H23NO4 | 353.16 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 35 | (+)-thalictrifoline | C21H23NO4 | 353.16 | Whole plant | [21] |

| 36 | (+)-cheilanthifoline | C19H19NO4 | 325.13 | Whole plant | [16] |

| 37 | corydaline | C22H27NO4 | 369.19 | Root | [18] |

| 38 | stylopine | C19H17NO4 | 323.12 | Root | [18] |

| 39 | mesotetrahydrocorysamine | C20H19NO4 | 337.13 | Whole plant | [16] |

| 40 | apocavidine | C20H21NO4 | 339.15 | Whole plant | [16] |

| 41 | 13-β-hydroxystylopine | C19H17NO5 | 339.11 | Whole plant | [16] |

| 42 | (−)-tetrahydropalmatine | C21H25NO4 | 355.18 | Whole plant | [19] |

| 43 | protopine | C20H19NO5 | 353.13 | Whole plant | [17] |

| 44 | allocryptopine | C21H23NO5 | 369.16 | Whole plant | [20] |

| 45 | berbinium | C19H16NO4+ | 322.11 | Whole plant | [15] |

| 46 | 1-formyl-5-methoxy-6-methylindoline | C11H13NO2 | 191.09 | Whole plant | [15] |

| 47 | 1-formyl-2-hydroxy-5-methoxy-6-methylindoline | C11H13NO3 | 207.09 | Whole plant | [15] |

| 48 | saxicolaline A | C20H22NO5 | 356.15 | Root | [18] |

| 49 | (+)-magnoflorine | C20H24NO4 | 342.17 | Root | [18] |

| 50 | (+)-isocorydine | C20H23NO4 | 341.16 | Whole plant | [19] |

| 51 | (−)-pallidine | C19H21NO4 | 327.15 | Whole plant | [19] |

| 52 | N-methylnarceimicine | C22H22NO8 | 428.13 | Root | [18] |

| 53 | adlumidine | C20H17NO6 | 367.11 | Root | [18] |

| 54 | (−)-salutaridine | C19H21NO4 | 327.15 | Root | [18] |

| 55 | cavidilinine | C19H13NO4 | 319.08 | Whole plant | [20] |

| 56 | corypalline | C11H15NO2 | 193.11 | Whole plant | [19] |

| 57 | oxyacanthine | C37H40N2O6 | 608.29 | Whole plant | [22] |

| 58 | corydalisin A | C37H38N2O9 | 654.26 | aerial parts | [1] |

| 59 | corydalisin B | C38H40N2O10 | 684.27 | aerial parts | [1] |

| 60 | cannabisin F | C36H36N2O8 | 624.25 | aerial parts | [1] |

| 61 | corydalisin C | C38H40N2O10 | 684.27 | aerial parts | [1] |

| 62 | cannabisin D | C36H36N2O8 | 624.25 | aerial parts | [1] |

| 63 | 1,2-dihydro-6,8-dimethoxy-7-hydroxyl-1-(3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)-N1, N2-bis[2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]-2,3-naphthalene dicarboxamide | C38H40N2O10 | 684.27 | aerial parts | [1] |

| 64 | cannabisin E | C36H38N2O9 | 642.26 | aerial parts | [1] |

| 65 | grossamide | C36H36N2O8 | 624.25 | aerial parts | [1] |

| 66 | feruloylagmatine | C15H22N4O3 | 306.17 | Whole plant | [19] |

| 67 | corysaxicolaine A | C39H30N2O8 | 654.20 | aerial parts | [7] |

| 68 | β-sitosterol | C29H50O | 414.39 | Whole plant | [22] |

| 69 | daucosterol | C35H60O6 | 576.44 | Whole plant | [22] |

| 70 | betulin | C30H50O2 | 484.43 | Whole plant | [22] |

| 71 | betulinic acid | C30H48O3 | 498.41 | Whole plant | [22] |

| 72 | β-amyrin | C30H50O | 426.39 | Whole plant | [20] |

| 73 | β-amyrin acetate | C32H52O2 | 468.40 | Whole plant | [22] |

| 74 | (+)-oleanolic acid | C30H48O3 | 454.38 | Whole plant | [22] |

| 75 | cholesterol | C27H46O | 386.35 | Whole plant | [23] |

| 76 | cycloeucalenol | C30H50O | 426.39 | Whole plant | [22] |

| 77 | 5-hydroxy-3′, 4′, 6, 7-tetramethoxyflavone | C19H18O7 | 358.11 | Whole plant | [20] |

| 78 | quercetin-3-O-β-D-galactoside | C21H20O12 | 461.10 | Whole plant | [20] |

| 79 | tetra-amino-27 alkane | C27H57N | 395.45 | Whole plant | [23] |

| 80 | tetra-amino-28 alkane | C28H59N | 409.46 | Whole plant | [23] |

| 81 | uracil | C4H4N2O2 | 112.03 | Whole plant | [20] |

Figure 2.

Chemical structures isolated from Corydalis saxicola Bunting.

5.1. Alkaloids

Alkaloids are key secondary metabolites of CSB. Due to the diversity of their structures and biological activities, an increasing number of studies on alkaloids have been conducted in China in recent decades. To date, 67 kinds of alkaloids have been identified and reported in CSB, such as berberines, protoberberines, benzophenanthridines, protoberberines, benzyltetrahydroisoquinolines, aporphines, protopines, and lignin amides (1–67) (Table 1). Six alkaloids with high purity were obtained from the crude n-butanol extract of CSB by high-speed counter-current chromatography: (−)-scoulerine (30), (+)-isocorydine (50), dehydrocheilanthifoline (8), dehydrocavidine (1), palmatine (9), and berberine (4) [24]. To investigate the phytochemical composition of CSB, the whole plant is usually selected as the source. As a rapid separation strategy, high-speed counter-current chromatography is the major majority approach to the isolation of the main components of it. The results basically show that alkaloids are the main components of CSB and the content of dehydrocavidine is the highest one.

5.2. Others

With the exception of alkaloids, 14 non-alkaloids were isolated and identified from CSB, including 9 steroids (68–76), 2 flavonoids (77–78), 2 alkanes (79–80), and 1 uracil (81) [22,23]. The research on other types of natural products is rarely performed apart from the alkaloids. Therefore, it is urgent to explore novel leading compound with biological activity in future discovery.

6. Pharmacology

In recent decades, modern pharmacological studies have shown that CSB has a wide range of pharmacological activities, such as anticancer, hepatoprotective, anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV), central nervous system, immune function enhancement, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antioxidant, antibacterial, and choleretic effects. A large number of studies have reported that the crude extracts and chemical constituents of CSB have strong biological activity both in vivo and in vitro. In addition, research on the activity of CSB has mainly focused on alkaloids. The pharmacological effects of CSB reported in recent years are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pharmacological activities of Corydalis saxicola Bunting.

| Tested Substance | Assay, Organism, or Cell Line | Biological Results | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticancer activity | CSBTA | Walker 256 induced bone pain and osteoporosis in rats, Breast Cancer Cells, RAW 264.7 macrophage cells, Walker 256 cells | Improved bone pain and osteoporosis in rats, suppressed expression of Rankl, down regulated the ratio of RANKL/OPG, inhibited pathways of NF-κB and c-Fos/NFATc1 to suppressed osteoclast formation | [25] |

| CSBTA | A549 cells | Inhibition migration of A549 cells by suppressing Cdc42 or Vav1 | [8] | |

| CSBTA | A549 cells | Inhibited tumor growth by down-regulating Survivin, reduced the degree of bone destruction | [26] | |

| CSBTA | A549 cells | Inhibited the migration ability of A549 cells, decreased the expression of Cdc42 protein | [27] | |

| CSBTA | A549 cells | Inhibition proliferation, induced apoptosis and up regulation of caspase and down of survivin | [28] | |

| CSBTA and cis-platinum | A549 cells | Inhibition proliferation | [29] | |

| CSBTA | Tca8113 cells | Induced apoptosis and suppression of Bcl-2 | [30] | |

| CSBTA | Tca8113 cells | Inhibition proliferation, induced apoptosis | [31] | |

| CSBTA | Tca8113 cells | Inhibition proliferation and telomerase activity | [32] | |

| CSBTA | CNE-1 | 112.41 µg/mL (IC50) | [23] | |

| CSBTA | CNE-2 | 123.46 µg/mL (IC50) | [23] | |

| CSBTA | A2780 | 148.40 µg/mL (IC50) | [23] | |

| CSBTA | SKOV3 | 128.51 µg/mL (IC50) | [23] | |

| CSBTA | PM2 | 166.66 µg/mL (IC50) | [23] | |

| CSB injection | mouse sarcoma S180 | The average tumor inhibition rate was more than 30% | [33] | |

| CSB injection | ehrlich ascites tumor | The average tumor inhibition rate was more than 30% | [33] | |

| CSB injection and aristolochic acid | mouse sarcoma S180 | The average tumor inhibition rate was more than 50% | [33] | |

| CSB injection and aristolochic acid | ehrlich ascites tumor | The average tumor inhibition rate was more than 50% | [33] | |

| CSB injection | mouse sarcoma S180 | Some inhibition and inhibited respiration | [17] | |

| CSB injection | ehrlich ascites tumor | Some inhibition and inhibited respiration | [17] | |

| CSB injection | liver cancer | Some inhibition and inhibited respiration | [17] | |

| CSB injection | ascites cancer | Some inhibition and inhibited respiration | [17] | |

| CSB injection | rat sarcoma 256 | Some inhibition and inhibited respiration | [17] | |

| CSB injection | mouse peritoneal macrophages | Significantly enhanced phagocytosis | [17] | |

| CSB injection | S180 | Inhibition of respiratory metabolism | [34] | |

| CSB injection | HAC | Inhibition of respiratory metabolism | [34] | |

| CSB injection | EAC | Inhibition of respiratory metabolism | [34] | |

| CSB injection | S180, HAC, EAC, W256, rat | Significantly inhibition | [35] | |

| CSB injection | S180, HAC, EAC, W256 | Killing effect | [36] | |

| aqueous extract | HepG2 | Inhibition proliferation and migration | [25] | |

| Corydalisin A | MGC-803 | 83.56 ±1.89 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin A | HepG2 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin A | T24 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin A | NCI-H460 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin A | Spca-2 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin B | MGC-803 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin B | HepG2 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin B | T24 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin B | NCI-H460 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin B | Spca-2 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin C | MGC-803 | 8.81 ±2.05 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin C | HepG2 | 22.23 ±1.85 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin C | T24 | 9.62 ±1.46 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin C | NCI-H460 | 25.79 ±1.04 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Corydalisin C | Spca-2 | 17.28 ±1.29 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin F | MGC-803 | 10.10 ±1.15 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin F | HepG2 | 38.93 ±1.07 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin F | T24 | 11.54 ±1.49 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin F | NCI-H460 | 30.96 ±1.27 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin F | Spca-2 | 22.23 ±1.44 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin E | MGC-803 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin E | HepG2 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin E | T24 | 46.54 ±1.62 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin E | NCI-H460 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin E | Spca-2 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin D | MGC-803 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin D | HepG2 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin D | T24 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin D | NCI-H460 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Cannabisin D | Spca-2 | > 100 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| 1,2-dihydro-6,8-dimethoxy-7-hydroxy-1-(3,5-dimethoxy-4- hydroxyphenyl)-N 1, N 2 -bis [2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) ethyl]-2,3-naphthalene dicarboxamide | MGC-803; HepG2;T24; NCI-H460; Spca-2 |

55.16 ±0.78 μM (IC50); > 100 μM (IC50); 48.15 ±1.09 μM (IC50); > 100 μM (IC50); 43.89 ±1.57 μM (IC50) |

[1] | |

| grossamide | MGC-803 | 26.95 ±1.24 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| grossamide | HepG2 | 40.75 ±0.88 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| grossamide | T24 | 21.19 ±1.53 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| grossamide | NCI-H460 | 36.38 ±1.39 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| grossamide | Spca-2 | 27.22 ±1.72 μM (IC50) | [1] | |

| Dehydrocavidine | SMMC-7721 | Significantly inhibition | [37] | |

| palmatine | SMMC-7721 | Significantly inhibition | [37] | |

| Dehydrocavidine | Tca8113 | Significantly inhibition, suppression of NF-kappa B, P50 and P60 | [38] | |

| CSBTA | Tca8113 | Significantly inhibition, suppression of NF-kappa B, P50 and P60 | [38] | |

| Dehydrocavidine | Tca8113 | Inhibition proliferation, telomerase activity and the expression of hTERT | [39] | |

| Pallidine | DNA topoisomerase I | Strong inhibitory effect on human DNA topoisomerase I | [19] | |

| scoulerine | DNA topoisomerase I | Strong inhibitory effect on human DNA topoisomerase I | [19] | |

| chelerythrine | unknown | Have certain anticancer effect | [21] | |

| (−)-13β-hydroxystylopine | unknown | Have certain anticancer effect | [21] | |

| Corysaxicolaine A | T24 | 7.63 μM (IC50) | [7] | |

| Corysaxicolaine A | A549 | 13.32 μM (IC50) | [7] | |

| Corysaxicolaine A | HepG2 | 12.39 μM (IC50) | [7] | |

| Corysaxicolaine A | MGC-803 | 9.98 μM (IC50) | [7] | |

| Corysaxicolaine A | SKOV3 | 12.36 μM (IC50) | [7] | |

| Hepatoprotective effects | CSBTA | rats | Interventional treatment of chronic liver injury | [40] |

| CSBTA | HSC-T6 | Induced apoptosis and autophagy | [41] | |

| CSBTA | CYP450s in rats | CYP1A2 (IC50, 38.08 μg/mL; Ki, 14.3 μg/mL), CYP2D1 (IC50, 20.89 μg/mL; Ki, 9.34 μg/mL), CYP2C6/11 (IC50 for diclofenac and S-mephenytoin, 56.98 and 31.59 μg/mL; Ki, 39.0 and 23.8 μg/mL), CYP2B1 (IC50, 48.49 μg/mL; )Ki, 36.3 μg/mL) | [42] | |

| CSBTA | chronic hepatotoxicity in rats | Restored the levels of 2-oxoglutarate, citrate, hippurateand taurine | [43] | |

| CSBTA | acute hepatic injury rats | Significantly reduced the content of AST, ALT | [44] | |

| chronic hepatic injury rats | Significantly increased the level of serum TP, reduced the content of AST, ALT, AKP, LN and HA | [45] | ||

| CSBTA | immune hepatic injury rat | Reduced serum GOT activity, IL-4, increased the rate of IFN-γ/IL-4 | [46] | |

| CSBTA | rats | Have certain preventive and therapeutic effect on acute liver injury and on chronic liver fibrosis | [47] | |

| CSBTA | rats | Obvious protective effect on acute liver injury, inhibited the formation of chronic liver fibrosis | [48] | |

| CSBTA | hepatic fibrosis rats | Inhibited the expression of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 | [49] | |

| CSBTA | acute hepatic injury rats | Increased the content of AST, ALT and SOD, reduced MDA |

[50] | |

| aqueous extract | liver fibrosis in rats | Regulated the level of some amino acids, identified 157 potential targets of CS and265 targets of liver fibrosis | [51] | |

| aqueous extract | acute hepatic injury rats | Improved deviations of metabolites (soleucine, alanine, glutamine, phosphocholine and glycerol) | [52] | |

| aqueous extract | acute hepatic injury rats | Increased the content of AST, ALT and SOD, reduced MDA |

[53] | |

| aqueous extract | acute hepatic injury rats | Reduced the contents of AST and ALTpromote the production of mouse hemolysin antibody LD50 = 298.5 mg·kg-1 |

[54] | |

| aqueous extract | acute hepatic injury rats | Reduced the content of AST and ALT | [55] | |

| Dehydrocavidine | HSC-T6 | Inhibition proliferation, induced apoptosis | [56] | |

| palmatine | HSC-T6 | Inhibition proliferation, induced apoptosis | [56] | |

| berberine | HSC-T6 | Inhibition proliferation, induced apoptosis | [56] | |

| Dehydrocavidine | hepatic fibrosis rats | Reduced hepatic hydroxyproline, increases urinary hydroxyproline |

[57] | |

| Dehydrocavidine | liver injury in rats | Down regulated EPHX2, HYOU1, GSTM3, Sult1a2 and P450, reduce free radical, lose weight, MDA, ALT, AST, ALP and TBIL | [58] | |

| Dehydrocavidine | liver injury in rats | Increased ALT, AST and TBIL, Reduces the inflammatory cell infiltration of cell degeneration and necrosis and damages the ultrastructure of liver cells | [59] | |

| Anti-HBV activity | extract | Duck hepatitis B virus | Reduced DHBV-DNA | [60] |

| total extract of root | HBsAg | 0.17 mg/mL (IC50) | [18] | |

| total extract of root | HBeAg | <0.04 mg/mL (IC50) | [18] | |

| Saxicolalines A | HBsAg | 2.19 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| Saxicolalines A | HBeAg | >2.81μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| N-methylnarceimicine | HBsAg | 1.22 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| N-methylnarceimicine | HBeAg | 1.84 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| 6-acetonyl-5,6-dihydrosanguinarine | HBsAg | 6.55 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| 6-acetonyl-5,6-dihydrosanguinarine | HBeAg | >2.54 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| dihydrochelerythrine | HBsAg | <0.05 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| dihydrochelerythrine | HBeAg | <0.05 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| adlumidine | HBsAg | 1.35 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| adlumidine | HBeAg | >2.73 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| (−)-salutaridine | HBsAg | 0.26 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| (−)-salutaridine | HBeAg | 0.43 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| palmatine | HBsAg | >4.26 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| palmatine | HBeAg | >4.26 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| protopine | HBsAg | 2.61 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| protopine | HBeAg | >4.25 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| coptisine | HBsAg | 2.74 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| coptisine | HBeAg | 3.19 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| (+)-magnoflorine | HBsAg | >4.39 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| (+)-magnoflorine | HBeAg | >4.39 μM (IC50) | [18] | |

| dehydrocheilanthifoline | HepG2.2.15 | 115.95 μM (CC50) | [3] | |

| dehydrocheilanthifoline | HBsAg | 15.84 ± 0.36 μM (IC50) | [3] | |

| dehydrocheilanthifoline | HBeAg | 17.12 ± 0.45 μM (IC50) | [3] | |

| dehydrocheilanthifoline | Extracellular DNA | 15.08 ± 0.66 μM (IC50) | [3] | |

| dehydrocheilanthifoline | Intracellular DNA | 7.62 ± 0.24 μM (IC50) | [3] | |

| dehydrocheilanthifoline | Intracellular cccDNA | 8.25 ± 0.43 μM (IC50) | [3] | |

| Crude extract | HBsAg | 0.16 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| Crude extract | HBeAg | < 0.04 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| 6-acetonyl-5, 6-dihydrosanguinarine | HBsAg | 0.65 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| 6-acetonyl-5, 6-dihydrosanguinarine | HBeAg | >1.00 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| dihydrochelerythrine | HBsAg | <0.02 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| dihydrochelerythrine | HBeAg | <0.02 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| adlumidine | HBsAg | 0.50 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| adlumidine | HBeAg | >1.00 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| (−)-salutaridine | HBsAg | 0.09 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| (−)-salutaridine | HBeAg | 0.15 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| palmatine | HBsAg | >1.50 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| palmatine | HBeAg | >1.50 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| protopine | HBsAg | 0.92 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| protopine | HBeAg | >1.50 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| coptisine | HBsAg | 0.88 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| coptisine | HBeAg | >1.02 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| (+)-magnoflorine | HBsAg | >1.50 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| (+)-magnoflorine | HBeAg | 1.50 mg/mL (IC50) | [61] | |

| dehydrocavidine | HBsAg | 33% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| dehydrocavidine | HBeAg | 22% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| dehydroapocavidine | HBsAg | 39% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| dehydroapocavidine | HBeAg | 24% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| dehydroisoapocavidine | HBsAg | 29% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| dehydroisoapocavidine | HBeAg | 23% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| berberine | HBsAg | 8% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| berberine | HBeAg | 7% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| dehydroisocorypalmine | HBsAg | 6% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| dehydroisocorypalmine | HBeAg | 6% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| coptisine | HBsAg | 6% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| coptisine | HBeAg | 9% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| tetradehydroscoulerine | HBsAg | 7% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| tetradehydroscoulerine | HBeAg | 6% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| berbinium | HBsAg | 9% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| berbinium | HBeAg | 6% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| 1-formyl-5-methoxy-6-methylindoline | HBsAg | 2% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| 1-formyl-5-methoxy-6-methylindoline | HBeAg | 7% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| 1-formyl-2-hydroxy-5-methoxy-6-methylindoline | HBsAg | 5% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| 1-formyl-2-hydroxy-5-methoxy-6-methylindoline | HBeAg | 3% inhibition [62.5 μg/mL] | [15] | |

| Enhancement of immune function | CSBTA | rats | CSBTA (40 μg/mL) began to enhance, enhanced the levels of T cell production of IFN-γ and IL-2 | [62] |

| Antioxidant activity | CSBTA | rats | Reduced the of content MDA and increase SOD activity, enhance the antioxidant capacity of rat liver | [63] |

| cavidine | DPPH assay | 6.85 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| cheilanthifoline | DPPH assay | 0.25 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| tetrahydropalmatine | DPPH assay | 3.79 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| stylopine | DPPH assay | 2.56 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| canadine | DPPH assay | 2.18 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| dehydrocavidine | DPPH assay | 16.51 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| dehydrocheilanthifoline | DPPH assay | 1.63 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| berberine | DPPH assay | 7.40 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| pallidine | DPPH assay | 1.00 mg/mL (IC50) | [2] | |

| Effects on the central nervous system | CSBTA | rats | Reduced the content of DOPAC, HVA, 5-HT and 5-HIAA, the level of DA has no effect (50, 100 mg/kg CSBTA) | [64] |

| CSBTA | rats | Reduced activity (25 mg/kg CSBTA) | [65] | |

| CSBTA | monkey | Reduced activity (12 mg/kg CSBTA) | [65] | |

| CSBTA | cats | Reduced activity (10-15 mg/kg CSBTA) | [65] | |

| CSBTA | rats | Reduced irritated response (50 mg/kg CSBTA) | [65] | |

| CSBTA | rats | 77% suppressed conditional emission (50 mg/kg CSBTA) | [65] | |

| CSBTA | rats | Increased the hypnotic time of pentobarbital sodium by more than 2 to 4 times (25 mg/kg CSBTA) | [65] | |

| CSBTA | rabbit | Activity slow down (20-30 mg/kg CSBTA) | [65] | |

| CSBTA | rats | LD50 = 223 mg/kg | [65] | |

| CSBTA | rats | Reduced the arthritis (50 mg/kg CSBTA) | [66] | |

| Dehydrocavidine | rats | Reduced the content of DA and HVA | [67] | |

| Dohydrocyaidine | rats | Reduced spontaneous activity | [68] | |

| Dohydrocyaidine | rats | Synergistic effect with barbiturates | [68] | |

| Anti-inflammatory activity | CSBTA | M1 macrophages | Obvious toxic effect on the activity of M1-Mφ, significantly reduced the mRNA level of IL-6, TNF-α, CD86, IL-1β | [69] |

| CSBTA | rats | Significantly inhibited the addition of capillary permeability, and suppressed exudation, edema and connective tissue hyperplasia | [70] | |

| Corydalis saxicola suppository | chronic pelvic inflammatory disease model rats | Significantly inhibited the uterine swelling, significantly reduced the spleen index, hemameba, neutrophil, TNF-α, IL-6 and MDA, improved thymus index, ovary index, lgG, lgM and SOD | [71] | |

| Corydalis saxicola rectal suppository | rats | Obvious inhibited ear swelling, the addition of capillary permeability, and writhing reaction in rat | [72] | |

| Analgesic effect | CSBTA | rats | Reduced the level of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β and PGE2. inhibited the overexpression level of DRG, TG, p-p38 and TRPV1 | [73] |

| CSBTA | rats | Inhibited the "writhing reaction" in rat (50 mg/kg CSBTA), improve the "pain closure" of rats to heat stimulation (100 mg/kg CSBTA) | [66] | |

| Dohydrocyaidine | rats | The effects of sedative, analgesic, and spasmolysis, LD50 = 71.6±2.92 mg/kg | [68] | |

| deheydrocavidine | unknown | Have certain sedative and analgesic effects | [21] | |

| Antibacterial activity | CSBTA | staphylococcus aureus | 17.8 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] |

| CSBTA | staphylococcus aureus | 70.0 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | streptococcus pyogenes | 20.5 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | streptococcus pyogenes | 70.0 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | streptococcus faecalis | 17.8 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | 70.0 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| CSBTA | escherichia coli | 35.5 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | 70.0 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| CSBTA | pseudomonas aeruginosa | 70.0 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | >300 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| CSBTA | shigella flexneri | 16.8 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | 35.5 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| CSBTA | salmonella typhi | 35.5 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | 70.0 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| CSBTA | salmonella enteritidis | 16.8 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | 70.0 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| CSBTA | klebsiella pneumoniae | 70.0 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | 130.0 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| CSBTA | proteus | 70.0 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | 130.0 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| CSBTA | candida albicans | 130.0 mg/mL (MIC) | [74] | |

| CSBTA | > 300 mg/mL (MBC) | [74] | ||

| extract | staphylococcus aureus | 20.0 mg/mL (MIC) | [75] | |

| extract +Cefradine | staphylococcus aureus | 0.375 (FIC) synergistic effect | [75] | |

| extract + Levofloxacin | staphylococcus aureus | 0.5 (FIC) synergistic effect | [75] | |

| extract + Fosfomycin | staphylococcus aureus | 1.5 (FIC) irrelevant effect | [75] | |

| extract + Penicillin | staphylococcus aureus | 0.375 (FIC) synergistic effect | [75] | |

| dehydrocarvidine | gram-positive strains; gram-negative bacterium |

Have certain inhibitory effect on gram-positive strains, minimum concentration is 0.078 mg/mL, and has no inhibitory effect on gram-negative bacteria | [76] | |

| deheydrocavidine | staphylococcus aureus; beta hemolytic streptococcus; corynebacterium diphtheriae; penicillin-resistant white staphylococcus aureus |

Have an inhibiting effect | [21] | |

| dohydrocyaidine | rats | Antibacterial effect | [68] | |

| ChOleretic effects | CSBTA | guinea pig | Bile secretion is temporarily reduced | [66] |

| extract | rats | Increased the amount of bile excretion | [77] | |

| Other activities | CSBTA | rats | Intervention of host co-metabolism and intestinal flora in rats with intestinal flora imbalance | [78] |

| CSBTA | rats | Significantly decreased the levels of plasma total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in rats, regulated blood lipid levels in high-fat diet rats | [79] | |

| Dehydrocarvidine | rats | The transport of dehydrocavidine was carried out in vitro at different intestine segments | [80] | |

| Dehydrocarvidine | Caco-2 cells | The bi-directional transport of dehydrocavidine in Caco-2 monolayer model showed significant difference | [80] |

6.1. Anticancer Activity

6.1.1. Crude Extracts

Cancer is still the leading cause of mortality among humans. Many parts of the body can trigger the growth of cancer cells, and the emergence of cancer poses a very large threat to human health. Recent studies have provided evidence that the anticancer activity of CSB is mainly related to its alkaloid compounds. Corydalis saxicola Bunting total alkaloids (CSBTA) has shown cytotoxicity against five cancer cell lines: CNE-1 (IC50 = 112.41 µg/mL), CNE-2 (IC50 = 123.46 µg/mL), A2780 (IC50 = 148.40 µg/mL), SKOV3 (IC50 = 128.51 µg/mL), and PM2 (IC50 = 166.66 µg/mL) [23].

CSB extracts can increase actin filament disassembly and cofilin-1 activity, and decrease Cdc42 protein expression in A549 cells to reduce the migration ability of cells [27]. Additionally, CSBTA inhibits migration of A549 cells by suppressing cell division cycle 42 or vav guanine nucleotide exchange factor 1 [8]. Another study found that the effects of CSBTA on the proliferation of A549 lung cancer cells displayed a time–dose relationship; with increasing concentration of CSBTA, the apoptosis rate of A549 cells increased, the expression of caspase-3 mRNA was upregulated, and the expression of survivin mRNA was downregulated [28]. Moreover, CSBTA combined with cisplatin can enhance the inhibition of proliferation of A549 cells [29].

A study confirmed that CSBTA inhibited the growth of A549 cell-transplanted tumours by downregulating survivin in nude mice, and it can also reduce the degree of bone destruction in bone metastases [26]. Furthermore, CSBTA attenuate Walker 256-induced bone pain and osteoporosis by suppressing the RANKL-induced NF-κB and c-Fos/NFATc1 pathways in rats [25].

The above five studies reported the activity of CSBTA on A549 cells, while there have also been studies on CSBTA in Tca8113 cells. CSBTA can significantly inhibit the proliferation and apoptosis of human tongue squamous cell carcinoma Tca8113 cells in a time-dependent and dose-dependent manner [31]. Additionally, [30] found that CSBTA could promote apoptosis of Tca8113 cells by inhibiting the expression of Bcl-2 at the mRNA and protein levels. [32]. Overall, as a leading compound targeting tumour pathway, CSBTA is promising for developing into a novel anticancer drug.

CSBI has been reported to exert a certain inhibitory effect on mouse S180 sarcoma and Ehrlich ascites tumours, with an average inhibition rate of more than 30%. In addition, the combination of CSBI and phagocytic acid can enhance the antitumour effects, with the average tumour inhibition rate reaching over 50% [33]. The antitumour activity of CSBTA was further evaluated through in vitro, semi-in vivo, in vivo, methylene blue reduction, and cell staining methods, and the results showed that CSBTA had a certain inhibitory effect on sarcoma 180 Ehrlich ascites carcinoma in mice and sarcoma 256 in rats [17,34,35]. Lu’s test reported that CSBTA could inhibit respiratory metabolism in S180, HAC, and EAC tumour cells [34]. The water extract of CSB can inhibit the proliferation and migration of HepG2 liver cancer cells, and its mechanism may be related to the upregulation of NF-κB p65 expression [25]. Therefore, the water extract of CSB and CSBTA has excellent antitumour activity against a variety of tumour cells. However, what specific components take effect in the water extract is still unclear and needs to be further explored.

6.1.2. Isolated Phytochemicals

Eight lignanamides (corydalisin A (58), corydalisin B (59), corydalisin C (61), cannabisin F (60), cannabisin E (64), cannabisin D (62), 1,2-dihydro-6,8-dimethoxy-7-hydroxy-1-(3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)-N1,N2-bis-[2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]-2,3-naphthalene dicarboxamide (63), and grossamide (65)) exhibited anticancer activity against five tumour cell lines (MGC-803, HepG2, T24, NCI-H460, and Spca-2; IC50 > 8.81 ± 2.05 μM). Meanwhile, corydalisin C may induce apoptosis via both the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways and downregulation of Bcl-2 and FasL expression in a time-dependent manner [1]. Dehydrocavidine (1) and palmatine (9) can inhibit the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma SMMC-7721 cells [37]. Dehydrocavidine (1) significantly inhibited the proliferation of human tongue squamous cell carcinoma Tca8113 cells and decreased the expression of NF-κB, telomerase activity and the expression of hTERT [38,39]. (−)-Pallidine (51) and (−)-scoulerine (30) have strong inhibitory effects on human DNA topoisomerase I [19]. Chelerythrine (15) and (−)-13β-hydroxystylopine (23) have certain anticancer effects [21]. Corysaxicolaine A (67) displayed obvious inhibitory effects on the tested human cancer cells (T24, A549, HepG2, MGC-803, SKOV3), with IC50 values of 7.63, 13.32, 12.39, 9.98, and 12.36 μM, respectively [7]. However, there is little research on the mechanisms of these individual compounds or their anticancer activity in vivo. Elucidating the anticancer activity and mechanism of CSBTA and its individual compounds should be the focus of future research.

6.2. Hepatoprotective Effects

6.2.1. Crude Extracts

A large number of studies have reported that CSB plays a pivotal role in the treatment of acute and chronic liver injury, liver fibrosis, and liver cirrhosis. Some researchers found that the expression levels of ALT, AST, MDA, and ALP in serum were significantly decreased, and ALB, SOD, and GSH was significantly increased in liver tissue of rats with acute and chronic liver injury after CSBTA intervention [20,39,40,41,45,46,48,49,50,51]. Moreover, CSBTA has an obvious protective effect on acute liver injury caused by CCl4 and can also inhibit the formation of chronic liver fibrosis in rats. The potential mechanisms for this protective effect may be related to anti-lipid peroxidation, inhibition of collagen synthesis, and the promotion of extracellular matrix degradation [48]. However, Bi [46] showed that 0.78 mg/kg and 2.34 mg/kg CSBTA could significantly reduce hepatocyte degeneration, necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and the activity of serum ALT but had no obvious effect on the activity of AST.

Some studies found that CSBTA has hepatoprotective and anti-fibrotic effects on rats with chronic liver fibrosis [47], which may promote the reversal of liver fibrosis by inhibiting the expression of TGF-β1 and MMP-9 [49]. The effects of CSBTA on chronic liver injury induced by CCl4 may include the regulation of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) circulation, intestinal microbial metabolism, and taurine and hypotaurine metabolism disorder [43]. Furthermore, researchers reported that dehydrocavidine (1), palmatine (9), and berberine (4) were shown to induce apoptosis and autophagy in HSC-T6 cells, and suggested that these three components may be the components in CSBTA that are effective against liver fibrosis [41]. Through the biotransformation mediation of CSBTA by CYP450s in the liver, CSBTA-drug interactions might occur through CYP450s inhibition, particularly CYP1A and CYP2D. [42].

This CSB extract could significantly reduce the degree of liver damage, exert a protective effect on acute liver injury caused by acetaminophen [54] and CCl4 [53], respectively. Meanwhile, the therapeutic effects of this CSB extract on acute liver injury induced by CCl4 may be related to regulation of alanine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and glycerol metabolic dysfunction [52,55].

Betulinic acid (71), β-amyrin acetate (73), and (−)-pallidine (51) in a CSB extract may play an anti-fibrotic role by regulating the targets FXR, COX-2, and MMP-1 [78]. 1H NMR was used to study the changes in the sera of rats with liver fibrosis induced by CCl4 treated with this CSB extract, and partial least squares discriminant analysis showed that metabolic disorders were reduced after CSB treatment [51]. In summary, the protective efficiency and anti-fibrosis effects on acute and chronic liver injury of CSBTA provide the scientific basis for the utilization of CSB resources. However, the discrepancy of action mechanism between monomer compounds and extracts needs further explanation.

6.2.2. Isolated Phytochemicals

Through the study of group–effect relationships, Lu [56] reported for the first time that dehydrocavidine (1), palmatine (9), and berberine (4) could significantly inhibit the proliferation of HSC-T6 cells and induce their apoptosis in vitro without obvious cytotoxic effects at effective concentrations. Dehydrocavidine (1) can significantly reduce ALT, AST, and total bilirubin (TBIL) in mice with acute liver injury and effectively reduce CCl4-induced hepatocyte degeneration, necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and ultrastructural destruction [59]. In a rat model of liver fibrosis induced by CCl4, dehydrocavidine (1) could reduce the degree of liver injury and the formation of interstitial fibrous tissue, and its mechanism of liver protection and liver fibrosis inhibition may be related to the extracellular matrix and antioxidant stress [57,58]. To date, most studies have focused on the effects of CSBTA on liver injury and fibrosis, while few studies have focused on its contained individual compounds. More studies should be undertaken that focus on this field.

6.3. Anti-HBV Activity

6.3.1. Crude Extract

HBV causes the disease hepatitis B, and it is also infectious to a certain extent. CSB has been reported to have very good anti-HBV activity. Wang’s experiment proved that the extract of CSB has anti-duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) effects in vivo, as the level of serum DHBV DNA in all CSB groups decreased significantly after treatment. Pathological examination showed that the CSB extract had a protective effect on liver injury induced by DHBV [60].

6.3.2. Isolated Phytochemicals

Zeng et al. [3] isolated dehydrocheilanthifoline (8) from CSB and showed its anti-HBV activity for the first time. The inhibition of HBsAg (IC50 17.12 μM) and HBeAg (IC50 15.58 μM) by dehydrocheilanthifoline was dose- and time-dependent, with obvious anti-HBV activity in vitro. Moreover, the anti-HBV activities of certain compounds isolated from CSB were evaluated, and dihydrochelerythrine (18) and (−)-salutaridine (54) were found to have strong inhibitory effects on HBsAg and HBeAg with IC50 values of <0.02, <0.02 mg/mL for dihydrochelerythrine (18), respectively, and 0.09, 0.15 mg/mL for (−)-salutaridine (54), respectively [61]. Dehydrocavidine (1), dehydroapocavidine (2), and dehydroisoapocavidine (3) had obvious inhibitory effects on HBsAg and HBeAg and showed no toxicity in 2.2.15 cells [15]. Furthermore, the anti-HBV activities of 10 major alkaloids were tested. Among the tested compounds, dihydrochelerythrine (18) exhibited the most potent activity against HBsAg and HBeAg secretion, with IC50 values < 0.05 μM and selectivity index (SI) values > 3.5 [18]. The research mentioned above showed the application value in the prevention and treatment of HBV of CSB. The practical values related to prevention and treatment of HBV indicate that the prevention of HBV utilizing dihydrochelerythrine (18) demands further studies on its mechanism of action.

6.4. Enhancement of Immune Function

Crude Extract

Immune function is the body’s resistance to diseases. The immune function of the human body is mainly manifested in three aspects: immunoligic defence, immunoligic homeostasis, and immunoligic surveillance. A study showed that CSBTA enhanced the haemolytic plaque value and delayed-type hypersensitivity in mice in vivo, enhanced the mixed culture response of allotypic mice splenocytes in vitro, and enhanced the proliferation response of splenocytes stimulated by mitogen. In addition, CSBTA increased the levels of IFN-γ and IL-2 produced by T cells in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that CSBTA is an enhancer of immune regulation [62]. It can be seen from the literature results that CSBTA has a certain effect on enhancing immune function.

6.5. Antioxidant Activity

6.5.1. Crude Extract

The IC50 refers to the measured semi-inhibitory concentration of an antagonist 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) is a relatively stable free radical and which is frequently used as a reactivity model of reactive oxygen species. In a study, when the DPPH radical was eliminated, the absorbance A at the maximum absorption wavelength of 519 nm decreased. CSBTA enhanced the antioxidative ability of rat livers by reducing the content of MDA and increasing the activity of SOD in a dose-dependent manner, which indicated that CSBTA can directly or indirectly alleviate liver cell injury and inflammation through antioxidation, thus playing a very good role in protecting the liver [63].

6.5.2. Isolated Phytochemicals

The IC50 of the free radical scavenging activity of nine alkaloids derived from CSB in vitro ranged from 0.25 to 16.51 mg/mL [2]. The structure–activity relationship study of the antioxidant activity showed that the antioxidant activities of compounds with basic tertiary amines were higher than those of their corresponding basic quaternary amine compounds [2]. The kinetics results showed that the compounds with the highest activity, (−)-pallidine (51) and (+)-cheilanthifoline (36), had non-linear DPPH radical scavenging activity, while the other alkaloids displayed linear DPPH radical scavenging activity, indicating that their DPPH radical scavenging activity was dose-dependent [2]. Despite its strong antioxidant activity, many unknown mechanisms of alkaloids exist, which demands further investigation.

6.6. Effects on the Central Nervous System

6.6.1. Crude Extract

The central nervous system is a group of neurons that regulate a specific physiological function, such as a respiratory center, a thermoregulation center, or a language center. There is increasing evidence showing how phytochemicals influence the central nervous system. They may take effect as anticonvulsants, antidepressants, hypnotic sedation, and anti-senile dementia, and have other pharmacological effects. Some studies have reported that CSB has effects on the central nervous system. A study demonstrated that CSBTA (50, 100 mg/kg) significantly decreased the contents of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), homovanillic acid (HVA), 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), and 5-hydroxyinolacetic acid (5-HIAA) but had no significant effect on the level of dopamine (DA). However, the DA/DOPAC and DA/HVA ratios increased, and the 5-HT/5-HIAA ratio of the limbic system also increased. Thus, it has been suggested that CSBTA can inhibit the metabolism of DA and 5-HT in certain brain regions [64]. Furthermore, CSBTA significantly inhibited caffeine-induced excitatory activity in mice. In general, CSBTA had a calming effect on monkeys and cats. Additionally, in some animals, CSBTA produced catalepsy. The irritation response induced by electrical stimulation was found to be significantly inhibited in mice. The conditioned response of the rats was blocked, but CSBTA showed little effect on the unconditioned response. In a study of the central inhibition mechanism, it was found that CSBTA decreased the levels of 5-HT and 5-HIAA in the striatum [66].

6.6.2. Isolated Phytochemicals

Dehydrocavidine (1), isolated from CSB, can increase the contents of DA and 3-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid in the striatum of normal rats and decrease the contents of DA and HVA in the striatum of model rats [67]. The results suggested that dehydrocavidine (1) can significantly block central DA function in rats. In short, dehydrocavidine (1) is the major contributor of CSB’s effects on the central nervous system.

6.7. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Crude Extracts

Inflammation is a body’s protective response to potentially harmful stimuli. The stimuli can initiate the immune system to provide protection, while the protective mechanism depends on neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, and monocytes. Those cells produce various inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-8, chemokines, eicosanoids, histamine, etc.), which results in acute inflammation. Notably, most Chinese herbal medicines have anti-inflammatory properties. A low dose of CSBTA (0.4375 mg/kg) could significantly inhibit the formation of cotton ball granuloma in mice and reduce the chronic inflammatory response [70]. Furthermore, intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg CSBTA could reduce the degree of foot swelling in rats with Danqing arthritis, but the same dose of subcutaneous radiation had no effect on formalin arthritis in rats [66]. CSBTA ameliorates diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by regulating hepatic PI3K/Akt and TLR4/NF-κB pathways in mice [4]. It has been reported that C. saxicola rectal suppository had obvious inhibitory effects on ear swelling induced by croton oil, on the increase in capillary permeability induced by acetic acid, and on the writhing reaction induced by peritoneal injection of acetic acid [72]. In addition, CSBTA also was shown to effectively suppress M1 polarization of THP-1-derived Mφs, which may improve the inflammatory environment [69]. Some studies have shown that C. saxicola suppository has a certain therapeutic effect on rats with chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, shows good anti-inflammatory effects, and regulates immunity. Its mechanism may be related to the regulation of the expression of the inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-6 and the immune proteins IgG and IgM [71]. Future research should identify which chemical constituents of CSB are responsible for these anti-inflammatory effects.

6.8. Analgesic Effect

6.8.1. Crude Extract

Pain is a kind of disease with complex pathogenesis and serious harm to human physical and mental health. Traditional medicines have long been used in the treatment of pain, and numerous medicinal herbs have been reported to be able to relieve pain effectively. Two studies have proven that CSBTA has good analgesic effects. Subcutaneous injection of CSBTA (50 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg) had an obvious inhibitory effect in the writhing reaction of mice, and CSBTA (10 mg/kg) also improved the pain threshold to heat stimulation in rats in the tail flicking test [66]. In another report, Kuai et al. [73] believed that the therapeutic effects of CSBTA were a result of blocking the activation of TRPV1 by improving neuronal damage, improving the loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers (IENFs), and inhibiting inflammation-induced p38 phosphorylation. Therefore, the analgesic effect of CSBTA initially reported on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy has proposed a novel strategy for the clinical treatment of this disease.

6.8.2. Isolated Phytochemicals

CSB is a Chinese herbal medicine with anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. The main component of CSB, dehydrocavidine (1), has shown sedative and analgesic effects [21,68]. In the future, the chemical composition of the components that produce analgesia need to be further explored and identified.

6.9. Antibacterial Activity

6.9.1. Crude Extract

Infections caused by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are one of the foremost causes of morbidity and mortality globally. However, natural products are the main sources of antimicrobials used in clinical practice, serving as a rich reservoir for the discovery of new antibiotics. As two good indicators for evaluating antimicrobial agents, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) refers to the minimum drug concentration that can inhibit the growth of bacteria in a certain medium, which is the minimum inhibitory concentration. The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) is the minimum concentration required to kill 99.9% of bacteria. CSBTA had inhibitory and bactericidal effects against nine common Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with MIC values ranging from 16.8–130 mg/mL [74]. Additionally, CSBTA exhibited antimicrobial activity with an MIC value of 20 mg/mL against Staphylococcus aureus. Notably, CSBTA combined with penicillin, cefradine, and levofloxacin effectively inhibited S. aureus [75]. The results above indicated that CSB and penicillin, cefradine, and levofloxacin had a synergistic antibacterial effect.

6.9.2. Isolated Phytochemicals

The content of dehydrocavidine (1) from CSB is high, approximately 0.1–0.2%. Dehydrocavidine (1) has inhibitory effects on S. aureus, Streptococcus β-haemolyticus, diphtheria bacilli, and β-streptococcus, as well as penicillin-resistant Staphylococcus albicans and S. aureus [21,68]. In addition, in vitro antibacterial tests further showed that dehydrocavidine (1) had certain inhibitory effects on Gram-positive strains at a minimum concentration of 0.078 mg/mL. However, it had no inhibitory effects on Gram-negative bacteria [76]. Palmatine (9) has a strong inhibitory effect on some common pyogenic cocci and intestinal pathogenic bacteria [81]. The potential mechanism of the antibacterial activity of these compounds needs to be studied in the future.

6.10. Choleretic Effects

Crude Extract

The impairment of bile flow generally results from a decreased function of the liver and gallbladder. Many traditional Chinese medicines are considered to have good choleretic effects. A researcher found that intravenous injection of CSBTA could increase bile excretion in normal Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats [77], which suggested that CSBTA has a regulating protection for the function gallbladder. However, intravenous injection of CSBTA (20 mg/kg) had no cholagogic effect on anesthetized guinea pigs [66]. Its mechanism needs further elaboration.

6.11. Other Activities

Without affecting the normal physiological state of rats, CSBTA can significantly reduce the levels of plasma total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in rats, regulate the level of blood lipids in rats fed a high-fat diet, and protect against fatty liver diseases caused by a high-fat diet [79]. Based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing and untargeted metabolomics analyses, CSBTA is an effective and reliable compound for use in co-metabolism and intestinal flora intervention methods in rats with antibiotic-induced intestinal flora imbalance [78]. Regarding the intestinal mucosal transport of dehydrocavidine (1), it had the ability to be effluxed by transporters, but it showed the characteristics of passive transport at a higher concentration range [80]. Apart from the mentioned activities, we suggest that we should further explore other pharmacological properties of CSB.

7. Clinical Applications

7.1. Icteric Hepatitis

Icteric hepatitis is an injury to the hepatocytes caused by various factors. The destruction of liver tissue leads to a decrease in bilirubin uptake and a decrease in the binding functions of hepatocytes, which leads to an increase in bilirubin in the blood [82,83,84]. The common causes of icteric hepatitis are viral infection, drug injury, alcohol injury, autoimmune factors, and so on. A large number of studies have reported that CSBI has a high total effective rate in the treatment of icteric hepatitis (Table 3).

Table 3.

The clinical application of Corydalis saxicola Bunting.

| Class | Drugs | Cases | Result | Adverse Reaction | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Icteric hepatitis | CSBI | unknow | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 87.5%, the control group was 62.5% (p < 0.01) | [85] | |

| CSBI | 42 | Significantly decreased contents of ALT, AST, γ-GT and TBIL (p < 0.05). | [86] | ||

| CSBI | 60 | The clinical symptoms and liver function in the treatment group were better than those in the control group (p < 0.05) | [87] | ||

| CSBI | 82 | Significantly improved symptoms of fatigue, abdominal distension, hepatalgia and poor appetite; obvious decrease of transaminase and bilirubin | [82] | ||

| CSBI | 98 | Improvement rate of poor appetite, hepatalgia, fatigue and abdominal distension was 85.7%, 84.4%, 76.8% and 87.8%, respectively, summary improvement is 83.4%. Significantly decreased contents of ALT, TBIL | [88] | ||

| CSBI | 29 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 93.1%, the control group was 71.0% (p < 0.05) | [89] | ||

| CSBI | 1 | Caused allergic reactions | Itching, palpitating, chills, fever | [83] | |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge & Yinzhihuang & CSB | 90 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 96.0%, the control group was 82.5% (p < 0.05) | [90] | ||

| Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge & Yinzhihuang & CSB | 90 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 96.0%, the control group was 82.5% (p < 0.05) | Precardiac discomfort, urticaria, skin itching, pain at the injection site | [91] | |

| Viral hepatitis | CSBI | 93 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 91.7%, the control group was 68.9% (p < 0.03) | There were no adverse reactions | [92] |

| CSBI | 50 | Significantly decreased ALT and TBIL (p < 0.05), the total effective rate of the treatment group was 94.0% | [93] | ||

| CSBI | 208 | TBil of treatment group dropped by 71.22%, the control group was 44.30% (p < 0.01); Dbil of treatment group dropped by 67.53% (p < 0.01) | low-grade fever | [94] | |

| CSBI | 360 | Significant difference in improvement rate of hepatalgia and poor appetite (p < 0.01), decreased the levels of T-BILI, D-BILI and ALT | [95] | ||

| CSBI | 60 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 88.23%, the control group was 76.92% (p < 0.05) | Local vascular pain | [96] | |

| CSBI | 33 | Decreased the contents of ALT and AST in a short time, improved protein metabolism | [97] | ||

| Compound Danshen & CSB | 100 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 96.14%, the control group was 64.58% (p < 0.01) | Mild rash | [98] | |

| Acute and chronic hepatitis | CSBI | 93 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 91.7%, the control group was 68.9% (p < 0.03) | There were no adverse reactions | [92] |

| Magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate & CSB | 65 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 89.23%, the control group was 70.14% (p < 0.05) | [99] | ||

| CSB & Telbivudine | 80 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 72.5%, the control group was 50% (p < 0.05) | [100] | ||

| CSB & Danshen injection | 70 | Significantly decreased ALT and TBIL, increased the ratio of A/G | [101] | ||

| Liver cancer | CSBI | 96 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 83.3%, the control group was 72.9% (p < 0.05), Significantly decreased ALT and AST | [102] | |

| CSBI | 96 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 83.3%, the control group was 72.9% (p < 0.05), the QOL of the treatment group (68.6±7.2) more than the control group (60.5±6.1) after treatment (p < 0.05) | [103] | ||

| CSBI | 96 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 79.2%, the control group was 50.0% (p < 0.05), effectively improve the levels of serum IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α, better than the control group | [104] | ||

| CSBI | 96 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 81.3%, the control group was 70.8% (p < 0.05), after treatment, the INF-γ, IL-4 and the ratio of INF-γ/IL-4 in the observation group were significantly better than those in the control group (p < 0.05) | [105] | ||

| CSBI | 120 | After treatment, the liver function recovery effect of the injection group was better than that of the control group (p < 0.05) | fever, skin itch; the injection group (6.7%), the control group (8.3%) |

[106] | |

| CSBI | 96 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 72.9%, the control group was 52.1% (p < 0.05) | [107] | ||

| CSBI | 96 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 83.3%, the control group was 64.4% (p < 0.05) | The adverse effects rate of the treatment group was 20.8%, the control group was 39.6% (p < 0.05) | [108] | |

| CSBI | 96 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 97.92%, the control group was 87.50% (p < 0.05) | The adverse effects rate of the treatment group was 10.42%, the control group was 39.6% (p < 0.05) | [109] | |

| CSBI | 110 | Quality of life improvement rate in the treatment group was 81.82%, the control group was 52.73% (p < 0.05) | [110] | ||

| CSBI | 42 | Significantly decreased the levels of ALT, AST, TBIL and γ-GT | Fever, shiver, skin itch | [86] | |

| CSBI | 60 | Significantly decreased the level of AFP, the white blood cell count goes up | [111] | ||

| CSBI | 46 | Significantly increased the level of ALT and AST (p < 0.05), decreased TBIL (p > 0.05) | [112] | ||

| CSBI & Octreotide | 116 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 96.4%, the control group was 92.9% (p < 0.05) | The adverse effects rate of the treatment group was 5.2%, the control group was 17.2% (p < 0.05) | [113] | |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | CSBI | 126 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 95.3%, the control group was 93.6% (p > 0.05) | Diarrhea, rash | [114] |

| Others | |||||

| Rectal cancer | CSBI | 68 | The total effective rate of the treatment group was 38.24%, the control group was 5.88% (p < 0.05) | [115] | |

| Hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome | CSBI & Ribavirin | 60 | Significantly decreased the duration of fever period and oliguria period, obvious the recovery of AST, ALT, LDH and BUN than the control group (p < 0.05) | [116] | |

| Liver cirrhosis | CSBI | 60 | Significantly effect in relieving symptoms, protecting liver and gallbladder | [117] |

After treating some patients with chronic liver disease and jaundice with CSBI, the symptoms of fatigue, abdominal distension, liver pain, and anorexia were significantly improved [84], and the decreases in transaminase and bilirubin were more obvious [82]. However, after CSBI injection, a patient with acute icteric hepatitis developed symptoms of pruritus, palpitation, chills, and fever, and immediately discontinued the use of CSBI. After discontinuation, the patient did not develop these symptoms again, which were considered to be an allergic reaction to CSBI [83]. All in all, CSBI plays a significant role in acute and chronic hepatitis with a higher total effective rate, but a few adverse reactions occur. Additionally, how to solve those adverse reactions is a potential research point.

In the clinical symptoms and the liver function indexes of some icteric hepatitis, CSBI injection is found to be superior to potassium magnesium aspartate [12,88,89,118], “Yinzhihuang” injection (including baicalin and the extracts of Artemisiacapillaris Thunb, Gardenia jasminoides Ellis, and Lonicera japonica Thunb.) [87]. Meanwhile, the curative effect of CSBI plus sugar once a day was significantly higher than that of 40 mL of Xilikang plus sugar once a day [85]. CSBI can repair liver damage after interventional therapy for advanced liver cancer with hepatocellular jaundice without obvious adverse reactions [86].

In some cases, CSB combined with other drugs for the treatment of icteric hepatitis showed high total effective rate, such as “Yinzhihuang” injection [119], compound glycyrrhizin [120], “Danshen” (Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge), and “Yinzhihuang” [90,91]. In addition, Artemisiae Scopariae Herba (30 g), CSB (30 g), Lysimachia christinae Hance (30 g), Serissa japonica (30 g), Pteris multifida poir (10 g), and Ardisia japonica (10 g) were used in the treatment of acute icteric hepatitis, The contents of TB and ALT decreased compared with those before treatment. Taking these results into account, the combined drug therapy with CSBI has a high efficacy in the treatment of icteric hepatitis in spite of the unknown metabolic interactions and mechanisms of action.

7.2. Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is a group of infectious diseases caused by hepatitis viruses that mainly damage the liver. The clinical manifestations of various hepatitis diseases are similar, as most patients may have digestive tract symptoms, systemic symptoms, jaundice, right upper abdominal pain, and so on.

In some clinical studies, after being treated with CSBI, ALT, and TBIL, levels were significantly decreased in patients with viral hepatitis [93] and chronic viral hepatitis B [92]. Compared with “Yinzhihuang” injection, CSBI has a better effect on patients with acute and chronic viral hepatitis and significantly decreased the levels of ALT, AST, and TBIL [94]; the degrees of reduction in TBIL, DBIL, and ALT were also significantly different [95]. Additionally, compared with diammonium glycyrrhizinate injection, CSBI has more obvious efficacy in the symptoms of jaundice. However, two patients reported that they had local vascular pain during the CSBI infusion, but the pain disappeared after the infusion was completed [96].

CSBI was shown to effectively improve the clinical symptoms of patients with acute and chronic viral hepatitis, and decrease the levels of serum total bilirubin (STB), 1-min bilirubin, ALT, and AST in a short period of time [97]. The effect of CSBI on STB was significantly better than that of potassium magnesium aspartate after 4 weeks of treatment [121]. In addition, “Danshen” injection combined with CSBI was used to treat severe jaundice stemming from viral hepatitis with a total effective rate of 96.14%. There was one mild rash in the treatment group and another in the control group [98]. From the perspective of enzymes, CSBI treats acute and chronic viral hepatitis by reducing the expression of ALT, AST, TBIL, and DBIL.

7.3. Acute and Chronic Hepatitis

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver caused by various factors and is divided into acute and chronic categories. Acute hepatitis is an abnormal liver function that occurs for the first time.

In a study, the levels of serum TBIL and ALT in patients with chronic hepatitis B treated with CSBI were found to be significantly lower than those in the control group, and symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and greasiness were improved [92,122]. In addition, injection of CSBI at the “Zusanli” acupoint can not only treat patients with acute hepatitis but also play the role of acupuncture in dredging meridians, regulating visceral function, strengthening body resistance, and eliminating toxins. Therefore, the combination of the two treatments has a good therapeutic effect; this provides an innovative perspective for the application of CSBI.

Magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate combined with CSBI was used to treat patients with chronic cholestatic hepatitis B [99]. Moreover, CSBI was combined with telbivudine for the treatment of chronic severe hepatitis B [123]. CSBI combined with breviscapine injection for the treatment of chronic severe hepatitis showed that the clinical efficacy in the treatment group was significantly better than that in the control group [100]. Furthermore, it has also been reported that CSBI can be combined with “Danshen” injection or atomolan for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B [101,124]. The above CSBI in combination with other drugs has a significant effect on the treatment of hepatitis B. Hence, assessing the contribution of combined drugs would optimize the combination and facilitate the development of CSBI-related drugs.

7.4. Liver Cancer

Liver cancer refers to malignant tumours occurring in the liver, usually due to primary liver cancer, but including both primary and metastatic liver disease. Primary carcinoma in liver cancer refers to carcinomas occurring in liver cells or intrahepatic bile duct cells. The etiology of primary liver cancer is not completely clear and may be the result of synergistic effects from multiple factors.

The effect of CSBI combined with interventional radiotherapy on liver function and quality of life (QOL) score in the observation group of a study were significantly higher than those in the control group after treatment [102,103]. Additionally, CSBI combined with interventional radiotherapy can effectively improve the clinical efficacy of middle and advanced liver cancer [104,105,107,108], and improve the quality of life of patients with advanced liver cancer [109]. In addition, CSBI had an obvious liver reparative effect after interventional therapy for advanced liver cancer with hepatocellular jaundice with fewer adverse reactions [86,106]. Hence, the combination therapies with CSBI and interventional radiotherapy have been shown to effectively treat liver cancer which encourages medicinal chemistry to further develop and improve therapies.

CSBI combined with hepatic arterial chemoembolization (TACE) significantly improved the immune function and quality of life of patients with advanced liver cancer [110]. CSBI can effectively prevent and treat liver damage after TACE treatment [112]. Moreover, CSBI combined with interventional therapy has a significant effect on relieving clinical symptoms and improving liver function, especially with respect to increasing serum albumin levels in patients with liver cancer [111]. Octreotide combined with CSBI had a significant effect on advanced liver cancer [113], No adverse reactions were observed except for local pain during subcutaneous injection of octreotide, nausea, vomiting, and local vascular prickling when CSBI was added to the treatment [125].

7.5. Hyperbilirubinemia

Bilirubin is a bile pigment that is not only the main pigment in human bile but also an important index of liver function and an important basis for the diagnosis of jaundice [126]. Jaundice may cause the patient’s skin, mucous membranes, and sclera to display yellow staining that may also be accompanied by abdominal distension, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, and other symptoms, some of which are even life-threatening in severe cases [114].

It has been reported that 54 cases of hyperbilirubinemia treated by CSBI showed significant clinical effects, with a total effective rate of 91.47% [126]. CSBI treatment can significantly reduce the degree of neonatal jaundice and shorten its duration, and adverse reactions such as rash and diarrhea were significantly lower in the CSBI treatment group than in the control group [114]. Furthermore, CSBI combined with reduced glutathione is effective in the treatment of hyperbilirubinemia.

7.6. Others

In addition to treating hepatitis and liver cancer, CSBI can also treat a number of other diseases. For example, CSBI has a good clinical effect in the treatment of advanced rectal cancer [115]. When ribavirin and CSBI were combined for the treatment of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, the recovery of AST, ALT, LDH, and BUN levels was more significant [116]. Both CSBI and “Shengmai” injections (the main ingredients include Radix ginseng rubra, Ophiopogon japonicus (Linn. f.) Ker-Gawl. and Schisandra chinensis) had good curative effects in alleviating the symptoms of liver cirrhosis, protecting the liver, and enhancing the gallbladder. However, “Shengmai” injection was notably superior to CSBI in alleviating discomfort in the liver area and yellow skin staining, and especially in reducing serum transaminase and bilirubin [117]. Therefore, in order to fully utilize CSBI, researchers should further explore CSBI alone or in combination with other drugs to treat other diseases.

8. Toxicity Assessment

To date, research on the toxicology and safety of CSB is very limited from both a traditional and modern standpoint.

There are some studies on the toxicity of CSBTA [54,68,83,91], and CSBTA (20 mg/kg/day) may have an inhibitory effect on the growth of rats, which was more obvious after three weeks of administration. In addition, there were no significant changes in SGPT, NPN, or haemogram in dogs after administration of CSBTA (3 mg/kg/day) for 2 or 4 weeks. The animals in both the treatment and control groups showed different degrees of sinus arrhythmias before and after administration [66]. The LD50 of CSBTA administered subcutaneously to mice was determined to be 233 mg/kg [65]. In another study, after oral administration of the CSB extract (560, 450, 360, 290, and 230 mg/kg), most of the mice died from poisoning within 2 days. The LD50 of this CSB extract was 298.5 mg/kg, and the 95% confidence limit was 257.2–346.5 mg/kg [54]. Therefore, this CSBI extract can be considered safe for use in a certain dose range.

There has been only one report on the toxicity of the individual CSB compounds. Acute toxicity from dehydrocavidine manifests as lethargy, weakness, paralysis, and death. The LD50 was determined to be 71.6 ± 2.92 mg/kg. A subtoxicity test administered this compound at dosages of 10 and 5 mg/kg/day. [68]. On the basis of the literature, toxicity tests of pure substances in CSB can be rarely found, which means it is urgent to perform a more toxicological experiment on it to subsequently guide its clinical application.