Abstract

Chlamydia pneumoniae causes community-acquired pneumonia and is associated with several chronic diseases, including asthma and atherosclerosis. The intracellular growth rate of C. pneumoniae slows dramatically during chronic infection, and such persistence leads to attenuated production of new elementary bodies, appearance of morphologically aberrant reticulate bodies, and altered expression of several chlamydial genes. We used an in vitro system to further characterize persistent C. pneumoniae infection, employing both ultrastructural and transcriptional activity measurements. HEp-2 cells were infected with C. pneumoniae (TW-183) at a multiplicity of infection of 3:1, and at 2 h postinfection gamma interferon (IFN-γ) was added to the medium at 0.15 or 0.50 ng/ml. Treated and untreated cultures were harvested at several times postinfection. RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed, and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analyses targeting primary transcripts from chlamydial rRNA operons as well as dnaA, polA, mutS, minD, ftsK, and ftsW mRNA were done. Some cultures were fixed and stained for electron microscopic analysis, and a real-time PCR assay was used to assess relative chlamydial chromosome accumulation under each culture condition. The latter assays showed that bacterial chromosome copies accumulated severalfold during IFN-γ treatment of infected HEp-2 cells, although less accumulation was observed in cells treated with the higher dose. Electron microscopy demonstrated that high-dose IFN-γ treatment elicited aberrant forms of the bacterium. RT-PCR showed that chlamydial primary rRNA transcripts were present in all IFN-γ-treated and untreated cell cultures, indicating bacterial metabolic activity. Transcripts from dnaA, polA, mutS, and minD, all of which encode products for bacterial chromosome replication and partition, were expressed in IFN-γ-treated and untreated cells. In contrast, ftsK and ftsW, encoding products for bacterial cell division, were expressed in untreated cells, but expression was attenuated in cells treated with low-dose IFN-γ and absent in cells given the high dose of cytokine. Thus, the development of persistence included production of transcripts for DNA replication-related, but not cell division-related, genes. These results provide new insight regarding molecular activities that accompany persistence of C. pneumoniae, as well as suggesting requirements for reactivation from persistent to productive growth.

Chlamydia pneumoniae and Chlamydia trachomatis are intracellular bacterial pathogens that function as etiologic agents of important human diseases. The former, for example, causes community-acquired pneumonia and has recently been associated with various chronic diseases such as asthma and atherosclerosis (9, 16). C. trachomatis remains a significant cause of infectious, preventable blindness (trachoma) in the developing world (26) and is a sexually transmitted pathogen known to cause fertility deficits in women (26), as well as chronic arthritis in both sexes (for a review, see reference 14). Infections with each organism show high rates of recurrence (3, 8), but currently available information usually does not allow unequivocal differentiation between recurrences due primarily to reinfection and those resulting from chronic, persistent infection. However, the large number of published case reports provide some evidence that C. pneumoniae can cause chronic respiratory infections, and these often are refractory to antibiotic therapy (10). Moreover, the increasingly strong association of C. pneumoniae with such chronic conditions as follicular conjunctivitis (19), adult-onset asthma (9), and atherosclerosis (16, 23) provides substantiation that this organism indeed can persist for extended periods in its human host.

Persistence of C. pneumoniae has been documented in various animal models of infection (18, 20), and studies using several cell culture model systems indicate that activation of chlamydial host cells by immune-regulated cytokines elicits a persistent growth state in this organism (22). This state is nonproductive, involving generation of enlarged, aberrantly shaped, nondividing C. pneumoniae reticulate bodies (RB) that do not mature into infectious elementary bodies (EB). The result of this type of chlamydia-host cell interaction is chronic infection that can be maintained in cell culture for extended periods (17).

Several in vitro models of C. trachomatis persistence have been characterized (1). Interestingly, in one such model system ultrastructural analysis suggested that organisms of this species made persistent in culture by treatment with gamma interferon (IFN-γ) continue to replicate and partition their genomes, even in the absence of subsequent cell division (2). This provides at least a partial explanation for the lack of production of new infectious EB by persistent C. trachomatis; however, no congruent information is available as yet for persistent C. pneumoniae. The present study was undertaken to investigate similar aspects of the molecular genetic behavior of persistent C. pneumoniae, using a well-described cell culture model system.

Data from the chlamydial genome sequence have identified orthologs for dnaA, polA, and mutS, each of which encodes a gene product required for DNA replication and repair (4) in C. pneumoniae; a minD ortholog has also been identified, the product of which is required for chromosome segregation (24). Chlamydiae apparently do not have an ftsZ gene (24) but do possess orthologs for ftsK and ftsW, each of which encodes a product required for cell division (5). In the work described here, we provide information regarding differential expression of these C. pneumoniae DNA replication- and cytokinesis-related genes under conditions of both persistent and productive growth. Our results indicate that mRNA from C. pneumoniae genes encoding products required for chromosome replication, repair, and segregation are synthesized regardless of whether the organism is in a persistent or a productive growth state. Organisms undergoing productive infection express cytokinesis-related transcripts as expected, whereas persistent organisms do not. These observations provide new information concerning the basic biology of chlamydial persistence and may be useful in the design of improved treatment regimens for chronic chlamydial infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and growth of C. pneumoniae.

The human bronchial epithelial cell line HEp-2 was used for growth and propagation of C. pneumoniae. HEp-2 cells were grown in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, Utah), 50 μg of vancomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml, and 10 μg of gentamicin (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) per ml. Cells were routinely maintained at 35°C in 7% CO2 in a water-jacketed CO2 incubator and passaged two or three times per week in 162-cm2 cell culture flasks (Corning Costar, Cambridge, Mass.). C. pneumoniae TW-183 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.) and propagated for 3 days in HEp-2 cells treated with 2 μg of cycloheximide (Sigma) per ml. Chlamydiae were collected from infected-cell sonicates by differential centrifugation, partially purified by centrifugation through a 30% Renografin (Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, N.J.) cushion, and resuspended in sucrose-phosphate buffer (SPB; 0.22 M sucrose, 0.2 M NaH2PO4, 0.2 M Na2HPO4, 5 mM glutamic acid [pH 7.4]), as described previously (15). Stock titers were determined, and stocks were stored at −80°C as described previously (15).

Infection and preparation of cells for nucleic acid analyses.

HEp-2 cells were trypsinized from 162-cm2 flasks, plated onto six-well cell culture plates (Corning Costar) at a density of 1.5 × 106 per well, and incubated overnight at 35°C in 7% CO2. The next day, cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 3 in 2 ml of SPB and centrifuged at 400 × g for 1 h at 30°C. Infected cells were incubated at 35°C for 30 min with rocking. The inocula were then aspirated, and fresh medium was added with or without specified amounts (0.15 or 0.50 ng/ml) of human recombinant IFN-γ (rIFN-γ; Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.). Extra plates were infected and treated to monitor the infection and condition of the host cells. These plates were fixed in absolute methanol, stained with Giemsa, and observed microscopically at each harvest time point. Cells were collected and processed for nucleic acid analysis every 12 h postinfection for the duration of the 96-h experiment. Uninfected control samples were processed at 48 h postinfection. For some control experiments, infected HEp-2 cell cultures were grown in the presence or absence of 2 pg of cycloheximide per ml and harvested at specified times for analyses. Cells from all cultures were collected and centrifuged, and pellets were flash frozen at −80°C. Cells from three plates were pooled (18 wells) for each sample at each harvest time to ensure adequate chlamydial DNA and RNA for analysis.

Ultrastructural analysis.

Monolayers of uninfected HEp-2 cells or cells infected for 48 h with C. pneumoniae and treated with rIFN-γ or left untreated were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and cells were gently removed from culture dishes with a cell scraper. The cells were then collected by centrifugation and fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde (electron microscopy [EM] grade; Sigma) in PBS (pH 7.4) for 2 h at 4°C. Following three washes in PBS, samples were fixed for 1 h at room temperature in 1% osmium tetroxide in PBS. The samples were then dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and embedded in Spurr's resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Ft. Washington, Pa.). Sections of 70 to 80 nm were cut, stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate, and viewed on a Zeiss transmission electron microscope.

Infectivity assays.

Monolayers of HEp-2 cells were infected with C. pneumoniae at a multiplicity of infection of 1 and subsequently treated with rIFN-γ at various doses 2 h postinfection or left untreated. To mimic a typical growth curve, cell sonicates were collected at 72 h and resuspended in SPB. Chlamydial titers from each sample were determined as described for infectivity (15).

Nucleic acid preparation.

Total nucleic acids were prepared from snap-frozen pellets of infected and uninfected HEp-2 cells via homogenization in 65°C buffered phenol and extensive extraction in phenol-chloroform (24:1), as described elsewhere (6). DNA was prepared for quantitative PCR analysis by treatment of total nucleic acid preparations with RNase A plus RNase T1 (Life Technologies). RNA was isolated from the preparations for reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis by treatment with RNase-free DNase 1 (RQ1; Promega Biotech, Madison, Wis.). Each DNA and RNA preparation was extensively extracted with phenol-chloroform and collected as an ethanol precipitate (11). RNA preparations were confirmed to be DNA free by PCR targeting the host β-actin gene in the absence of RT. The integrity of RNA preparations was assessed by visual analysis of ethidium bromide-stained formaldehyde-agarose electrophoresis gels and by RT-PCR targeting of the host actin gene (6, 11).

Real-time PCR analyses.

To assess the accumulation of C. pneumoniae chromosome over time postinfection in host cells treated with cycloheximide or rIFN-γ or left untreated, we adapted a highly quantitative real-time PCR assay system described and tested by others (21). Briefly, the chlamydia-directed primers target the two copies of the 16S rRNA gene on the bacterial chromosome, while assay input is normalized simultaneously to host 18S rRNA gene sequences. The C. pneumoniae-directed primers for the assay were designed using software supplied for this purpose by PE Biosystems (Foster City, Calif.); these primers were 5′-GTTGTTATTTAGTGGCGGAA-3′ and 5′-CCCACCAACAAGCTGATA-3′. Extensive control studies confirmed that only a single amplification product is generated by this primer system and that the product is the appropriate segment of the C. pneumoniae 16S rRNA coding sequence. The human 18S-directed primer system used for normalization was purchased from PE Biosystems and was designed for this use. All assays were done several times, each in triplicate, using a PE Biosystems model 7700 sequence detector with the SYBR green method (12). Data from real-time PCR assays were calculated using sequence detection software, version 1.7, from PE Biosystems.

RT-PCR analyses.

RT was done as previously described (6) with 5 μg of total RNA from each preparation, random hexamers as primers, and murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). cDNA from each reaction was treated with RNase A, RNase T1, and RNase H, extracted several times with phenol-chloroform (24:1), and then collected as an ethanol precipitation (6, 11). The genes targeted in RT-PCR are given in Table 1, along with the primer sequences employed for amplification. Primer sequences were designed using the GeneRunner system (Hastings Software, Hastings, N.Y.) based on published sequence information (http://stdgen.lanl.gov). Each primer set was tested to confirm that chlamydial but not host cell sequences were amplified; control experiments established that all assay systems had approximately equivalent sensitivities and were able to identify transcripts from 10 to 30 bacterial cells. Amplification conditions for the first round of nested reactions were 4 min at 95°C, 35 cycles of 40 s at 95°C, 40 s at the annealing temperature, and 40 s at 72°C, and 10 min at 72°C. Annealing temperatures varied somewhat among the several primer sets. The second nested amplification round was done using similar cycling parameters and 10% of the first-round reaction mixture. The positive control for chlamydial transcriptional activity was demonstration of primary transcripts from the bacterial rRNA operons, as previously described (7). Amplifications were done using Ampli-Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin Elmer) in a thermocycler (model PTC-100; MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.). Products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining of standard agarose electrophoretic gels (11). Representative RT-PCR products were hybridized with internal chlamydial DNA probes to verify their authenticity.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR assays targeting C. pneumoniae mRNA

| Gene | Primer |

|---|---|

| adt1 | 5′-GCCGATACATACTCACGAGCTAAAGAAAG-3′ (outer) |

| 5′-GCGAGGATCGGTCAATACGTTCTTA-3′ (outer) | |

| 5′-GACTGTAATTTATCCGCTACGCGATGTT-3′ (inner) | |

| 5′-GCGAGGATCGGTCAATACGTTCTTA-3′ (inner) | |

| dnaA | 5′-GACCTCTGTTCTTTTGTCCCCTTAGATG-3′ (outer) |

| 5′-GATCTTTAGAGCGTGAGTTTCCCTTA-2′ (outer) | |

| 5′-GCCGCTCCTACAACCCTTTATTCATCC-3′ (inner) | |

| 5′-TCCTTTTTGCTCCGCCTTGTGCTGT-3′ (inner) | |

| polA | 5′-GCTGAGCACTGGACAAATGGGGGAGG-3′ (outer) |

| 5′-GAGGGGTGTATTCTCTGTGTATGG-3′ (outer) | |

| 5′-GGGGAAATGCAGGATTGCCTATAGGTC-3′ (inner) | |

| 5′-CACTACGTAAAGCCTCTAACACCTCTGCAC-3′ (inner) | |

| mutS | 5′-CACTTTGCTATCCTCCACCCTGCTCCA-3′ (outer) |

| 5′-CTGAGTGTCCCGATATCTCTAGGCCCTGC-3′ (outer) | |

| 5′-CGTATCGGGTCTCTGTTTGGTTTTGCTTG-3′ (inner) | |

| 5′-GAGGATCATTCAAGGGAGCGAGGAGC-3′ (inner) | |

| ftsK | 5′-TGGCTAGAGCTGTAGGGATTCATCTGA-3′ (outer) |

| 5′-TAAACTAGCTGCTGCGGCATAACCAA-3′ (outer) | |

| 5′-CTATACGAGCTCAGGGTGCCTACATTTG-3′ (inner) | |

| 5′-TAAACTAGCTGCTGCGGCATAACCAA-3′ (inner) | |

| ftsW | 5′-AGCTCTCATCCGCCAGGTGACCTATC-3′ (outer) |

| 5′-CGAACTCCTCAGCGTAGATTGCGGCA-3′ (outer) | |

| 5′-AGACGTTGGTTGGGGTTCGGTCAGC-3′ (inner) | |

| 5′-CAGGATGAAGGTAGACGTTTAAGCGG-3′ (inner) |

Statistics.

Each real-time PCR assay was performed twice on each of three separate cell preparations, and each tube in each assay was run in triplicate. Standard errors were calculated for the results shown in Fig. 1 and 6 using Excel (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, Wash.).

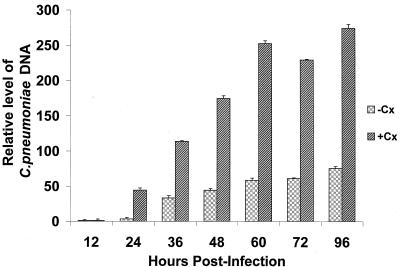

FIG. 1.

Results of quantitative real-time PCR assays to determine the relative level of accumulation of C. pneumoniae chromosomal DNA over time during infection of untreated (−Cx) and cycloheximide-treated (+Cx) HEp-2 cells. Cells were infected with C. pneumoniae TW-183 as described in Materials and Methods, and cultures were harvested at the times indicated. Total DNA was prepared, and a real-time PCR assay system was employed to determine the relative level of chlamydia DNA at each time point. Input into each quantitative assay was normalized to the host 18S rRNA genes, as described in Materials and Methods. Data are triplicate means plus standard errors and are expressed as fold increase in chlamydial DNA over time relative to the value obtained at 12 h postinfection.

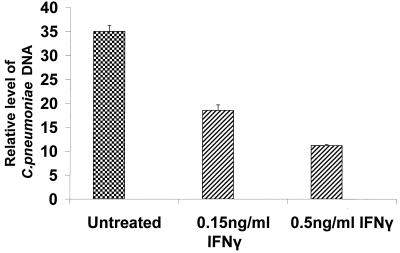

FIG. 6.

Results from quantitative real-time PCR assays to determine the relative level of accumulation of C. pneumoniae chromosomal DNA during infection of untreated infected HEp-2 cells and infected HEp-2 cells treated with either 0.15 or 0.50 ng of rIFN-γ per ml. Cells were infected with C. pneumoniae TW-183 as described in Materials and Methods. Both treated and untreated cultures were grown without cycloheximide and were harvested at 48 h postinfection or posttreatment. DNA was prepared, and a real-time PCR assay system was used to determine the relative level of Chlamydia DNA from each preparation. Input into each assay was normalized to the host 18S rRNA genes, as described in Materials and Methods. Data are triplicate mean values relative to the mean value obtained for untreated cells at 12 h postinfection (not shown). Standard errors are indicated.

RESULTS

Accumulation of chlamydial DNA and expression of DNA replication- and cytokinesis-related genes during infection of HEp-2 cells.

C. pneumoniae completes the standard developmental cycle within HEp-2 cells. However, growth of the organism in infected cell cultures is usually done in the presence of cycloheximide to increase the yield of infectious EB. To provide controls for the relative amount of chlamydial DNA produced under various treatment conditions, including treatment with rIFN-γ (see below), a highly quantitative real-time PCR assay targeting the C. pneumoniae 16S rRNA genes was used. The data shown in Fig. 1 indicate that when chlamydial DNA levels were compared as a function of incubation time in untreated and cycloheximide-treated HEp-2 cells, a time-dependent increase occurred, and as expected, greater amounts of chlamydial chromosome accumulated in cycloheximide-treated than untreated host cells. Part of this observed increase may have been due to less host 18S rRNA in cycloheximide-treated samples, but chlamydial growth does occur to a greater extent in host cells treated with cycloheximide. We found that at 96 h postinfection, the final time point examined in these experiments, the cycloheximide-treated cultures had accumulated in excess of 3.5-fold more chlamydial DNA than the untreated culture. In the treated cultures, accumulation of bacterial chromosome over 96 h was at the level of about 270-fold, indicating seven to eight cell divisions undertaken by each RB within the inclusions. Several repeats of these determinations yielded virtually identical results.

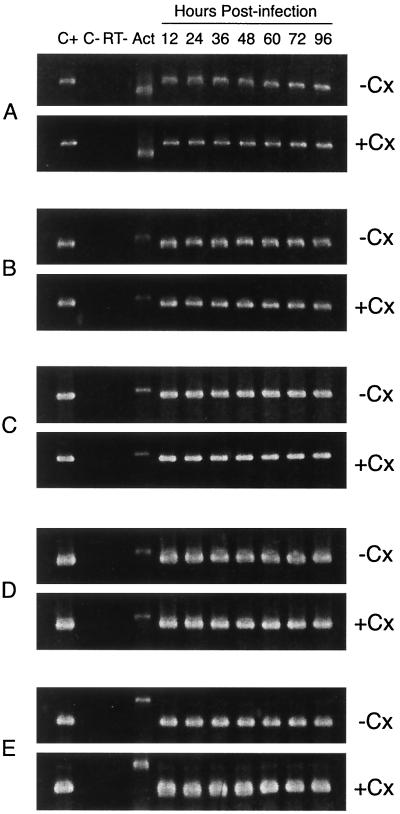

As a control for transcript-related experiments given below, the time course of expression was determined for a panel of C. pneumoniae genes whose products are involved in replication and partition of the bacterial chromosome, as well as the cell division process, in untreated and cycloheximide-treated HEp-2 cells. Figure 2 shows representative results from these nonquantitative RT-PCR studies. In both treated and untreated infected HEp-2 cells, primary transcripts from the rRNA operons were apparent at 12 h postinfection, as was mRNA from adt1, which specifies an ATP-ADP exchange protein of the organism. Similarly, dnaA, polA, and ftsK all were being expressed by 12 h after initiation of infection, the earliest time assayed in both treated and untreated cells; expression of each of these genes continued through 96 h postinfection. Similar results were obtained for mutS, minD, and ftsW (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Representative RT-PCR analyses targeting C. pneumoniae genes whose products are required for chromosomal DNA replication and cell division, as a function of time in infection of untreated (−CX) or cycloheximide-treated (+CX) HEp-2 cells. Cells were infected with chlamydiae and harvested at the indicated times, and RNA was prepared from each harvested culture (see Material and Methods). RT-PCR analyses were performed using primers given in Table 1. (A) Primary rDNA transcripts; (B) adt1 transcript; (C) dnaA transcript; (D) polA transcript; (E) ftsK transcript. Lanes: C+, positive PCR controls for each primer set, using C. pneumoniae DNA as the amplification template; C−, negative RT-PCR controls using cDNA from uninfected HEp-2 cells as the amplification template; RT−, negative control showing the results of PCR with each primer set in the absence of RT of RNA preparations used; ACT, amplification product from an RT-PCR assay targeting host β-actin mRNA. Input into each assay was normalized to the host β-actin transcript. Sizes of the amplification products: primary rRNA, 609 bp; adt1, 433 bp; host actin, 550 bp; dnaA, 410 bp; polA, 405 bp; ftsK, 238 bp.

Effects of IFN-γ on C. pneumoniae development and ultrastructure in IFN-γ-treated HEp-2 cells.

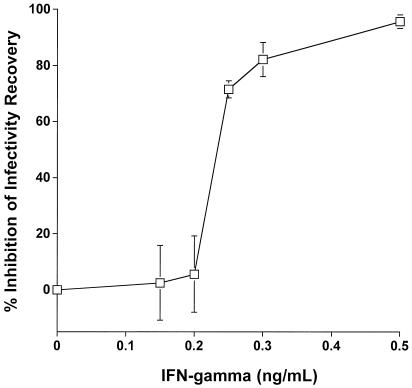

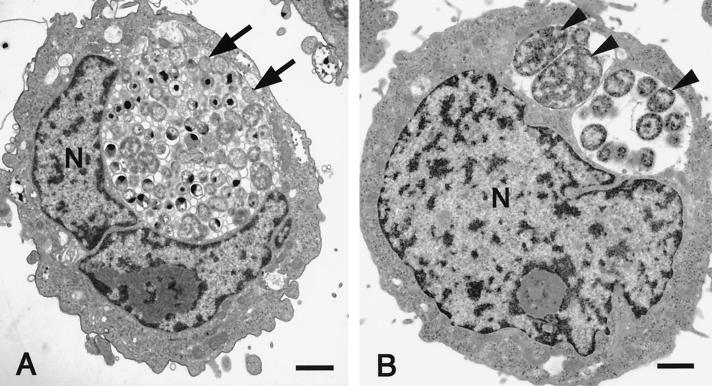

Treatment of HEp-2 cells with rIFN-γ 2 h after infection with C. pneumoniae caused a dose-dependent inhibition of infectivity recovery (Fig. 3). Transmission EM of infected HEp-2 cells demonstrated classic EB and RB developmental forms 48 h postinfection (data not shown). When cells were treated with subinhibitory doses of rIFN-γ, normal-appearing inclusions also were observed after 48 h of growth (Fig. 4A). In contrast, infected HEp-2 cells treated with 0.5 ng of rIFN-γ per ml for 48 h demonstrated essentially universal development of enlarged persistent forms, as judged from EM (Fig. 4B). This form of the organism is indicative of noninfectious, poorly dividing, greatly enlarged, and aberrantly shaped RB and is known to be a result of IFN-γ-mediated induction of the tryptophan-decyclizing enzyme indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase, which limits availability of the required amino acid tryptophan (1). The presence of these aberrant forms was used as a basis for comparison of selected transcriptional activities with organisms progressing through a productive infection in HEp-2 cells.

FIG. 3.

Effect of IFN-γ on C. pneumoniae growth in HEp-2 cells. Cells were treated with the indicated amounts of IFN-γ 2 h postinfection and assayed for infectivity after 3 days of incubation. Results are means for individual samples from each treatment group as a function of the averaged untreated control. All samples were assayed in triplicate, and standard deviations are shown. Samples from cells exposed to 0.15 and 0.5 ng of IFN-γ per ml were used for ultrastructural analyses.

FIG. 4.

Ultrastructural analysis by transmission EM of HEp-2 cells persistently infected for 48 h with C. pneumoniae. (A) Treatment with low levels of IFN-γ (0.15 ng/ml) resulted in the development of typical inclusions containing EB and RB. Normal RB are indicated by arrows. (B) Treatment with 0.50 ng of IFN-γ per ml to induce persistence engenders development of grossly enlarged RB (arrowheads). N, nucleus. Bar = 1 μm.

Viability of C. pneumoniae in untreated and rIFN-γ-treated HEp-2 cell cultures.

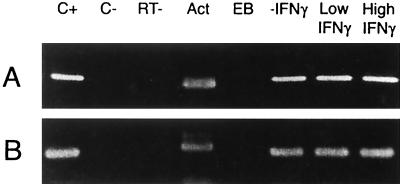

To determine if the morphologically aberrant chlamydiae observed in EM studies exhibit metabolic activity, infected HEp-2 cells treated for 48 h with 0.15 or 0.5 ng of rIFN-γ per ml were assessed for the presence of primary transcripts from the chlamydial rRNA operons. These transcripts were detectable by RT-PCR by 12 h postinfection in chlamydia-infected cells not treated with rIFN-γ, and their expression continued through 96 h (Fig. 2); similarly, the chlamydial adt1 gene was expressed from 12 to 96 h postinfection in untreated cells. Transcripts from these genes were not detectable in chlamydial EB but were demonstrable in infected HEp-2 cells treated with either high- or low-dose rIFN-γ (Fig. 5). These data support the contention that while C. pneumoniae organisms grown in the presence of rIFN-γ assume an aberrant morphologic form, they do remain viable, as judged by the presence of RNA species characteristic of metabolically active bacteria.

FIG. 5.

Representative RT-PCR analyses targeting primary transcripts from the C. pneumoniae rRNA operons (A) and adt1 (B) in untreated infected HEp-2 cells and infected HEp-2 cells treated with low or high doses of rIFN-γ. Cells were infected with chlamydiae and harvested at 48 h posttreatment, and RNA was prepared from each harvested culture (see Material and Methods). RT-PCR analyses were performed using primers given in Table 1. Lanes: C+, positive PCR control for each primer set, using C. pneumoniae DNA as the amplification template. C−, negative RT-PCR control using cDNA from uninfected HEp-2 cells as the amplification template; RT−, negative control showing the results of PCR with each primer set in the absence of RT of RNA preparations used; Act, amplification product from an RT-PCR assay targeting host β-actin mRNA; EB, amplification product from pure EB RNA. Sizes of the amplification products are given in the legend to Fig. 1.

Chromosome replication in rIFN-γ-treated C. pneumoniae.

The control experiments described above indicated that replication of the chlamydial chromosome was under way by 24 h postinfection in both untreated and cycloheximide-treated infected HEp-2 cells (Fig. 1). When the relative levels of C. pneumoniae DNA were compared in untreated cells and those treated for 48 h with 0.15 or 0.5 ng of rIFN-γ per ml, evidence for bacterial chromosome replication in the IFN-γ-treated samples was observed (Fig. 6). Clearly, less bacterial DNA was produced in the cultures treated with 0.5 ng of IFN-γ per ml than in untreated cultures, but these data confirm the contention that persistent C. pneumoniae are metabolically active and that aberrant chlamydial morphology and growth did not cause complete inhibition of genome replication.

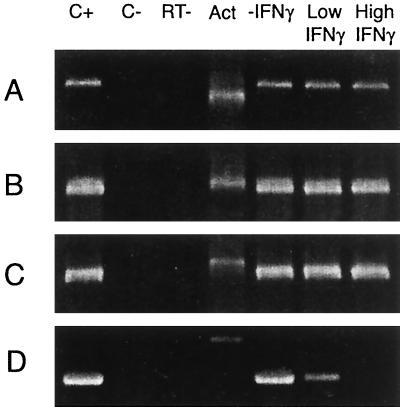

Expression of chlamydial DNA replication- and cytokinesis-related genes in untreated and rIFN-γ-treated infected HEp-2 cells.

Control studies (Fig. 2) clearly indicated that the chlamydial dnaA, polA, ftsK, and ftsW genes are expressed as early as 12 h postinfection in HEp-2 cells, regardless of whether the cells are treated with cycloheximide. To determine whether these chlamydial DNA replication- and cytokinesis-related genes are expressed during persistent growth induced by cytokine treatment, we assessed the presence of mRNA encoding them in RNA prepared from infected HEp-2 cells treated for 48 h with 0.15 or 0.50 ng of rIFN-γ per ml. As indicated by representative assays (Fig. 7), chlamydial DNA replication- and partition-related genes were expressed in rIFN-γ-treated infected HEp-2 cultures regardless of the cytokine concentration in the growth medium. However, amplification products of the chlamydial ftsK and ftsW genes, whose products are required for cell division, were attenuated in cultures treated with 0.15 ng of rIFN-γ per ml, and they were not found in RNA or cDNA preparations from cells grown with the higher cytokine concentration.

FIG. 7.

Representative RT-PCR analyses targeting transcripts from C. pneumoniae DNA replication- and cell division-related genes in untreated infected HEp-2 cells and infected HEp-2 cells treated with low or high doses of rIFN-γ. Cells were infected with chlamydiae and harvested at 48 h posttreatment, and RNA was prepared from each harvested culture (see Material and Methods). RT-PCR analyses were performed using primers given in Table 1. (A) primary rRNA transcripts; (B) dnaA; (C) polA; (D) ftsK. Lanes: C+, positive PCR control for each primer set, using C. pneumoniae DNA as the amplification template; C−, negative RT-PCR control, using cDNA from uninfected HEp-2 cells as the amplification template; RT−, negative control showing the results of PCR with each primer set in the absence of RT of RNA preparations used; ACT, amplification product from an RT-PCR assay targeting host β-actin mRNA. Input was normalized to the host β-actin mRNA. Sizes of the amplification products are given in the legend to Fig. 1.

DISCUSSION

Active ocular or urogenital infection with C. trachomatis represents a clinically significant event. However, it is now clear that long-term, persistent infection with this organism often engenders severe and difficult-to-treat sequelae. Similarly, the pneumonia resulting from respiratory infection by C. pneumoniae can be significant, but increasing evidence supports both the existence and the clinical importance of chronic infection with this organism. Evidence also argues that this latter state may be of the most import in terms of overall human health. A good deal of information is currently available concerning biochemical and molecular genetic characteristics of persistent C. trachomatis. For example, morphologic and microbiologic studies indicate that during persistence, cells of this organism are characterized by a reduced capacity for the enlarged and aberrantly shaped RB to undergo cell division but that these abnormal intracellular organisms continue to replicate their genomes (2). Failure to undergo cell division has been noted for IFN-γ-mediated induction of persistence in C. pneumoniae (22), and data in the present report provide an explanation for that lack of cytokinesis. Results of RT-PCR analyses, targeting C. pneumoniae genes whose products are required for chromosomal DNA replication and partition, indicate that those genes are expressed during IFN-γ-induced persistent infection. In contrast, genes required for bacterial cell division either are not expressed or are expressed only at an extremely low level during persistence, thus essentially eliminating cytokinesis during this growth state. The functional result of expression of DNA replication and segregation genes by the bacterium should be accumulation of chlamydial chromosome; the results presented here confirm that C. pneumoniae DNA does indeed accumulate during cytokine-induced persistence, although the level of accumulation is low.

We did not attempt to quantitate relative transcript levels for the C. pneumoniae genes assayed in either untreated or IFN-γ-treated infected HEp-2 cells. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that the ftsK and ftsW mRNAs were missed in the analysis of the high-dose-cytokine-treated samples. Control studies not shown here indicated that the relative sensitivities of the RT-PCR assay systems employed are approximately equivalent, and each of the assays routinely identifies the targeted transcripts from 10 to 30 bacterial cells. In the untreated infected cells, amplified products from the dnaA, mutS, minD, polA, ftsK, and ftsW cDNA were demonstrable even after the first round of the nested PCR. In the low-dose-rIFN-γ-treated cells, products from the replication-related genes were easily identifiable after the two amplification rounds, as they were in cDNA from the high-dose-cytokine-treated cells. No products for the two cytokinesis-related genes could be identified even after the second, nested amplification in cells treated with 0.50 ng of cytokine per ml, although the nonnested assays for primary transcripts from the rRNA operons gave clear products from the same RNA-cDNA preparations. The important point is that we could identify no products derived from either of the cytokinesis-related mRNAs in the high-dose-rIFN-γ-treated infected HEp-2 cells, indicating that expression of the two cell division-related genes is severely attenuated, even if it is not completely abolished, during cytokine-induced persistent C. pneumoniae infection.

This study provides important new information regarding gene regulation patterns intrinsic to intracellular chlamydial growth, during both active and persistent infection. Clearly, differential gene expression does occur in these two states, almost certainly as a result of modulation of the host cell environment. One mechanism by which chlamydiae might sense host environmental changes is through a two-component signaling system, as has been described for a variety of other bacterial pathogens (13). For example, a histidine kinase (designated Cpn 0584; http://www.stdgen.lanl.gov) has been identified in the C. pneumoniae genome, and this enzyme shows possible two-component regulatory activity. Importantly, a recent study has shown that C. trachomatis exhibits differential, developmentally regulated expression of its three sigma factors, and it has been postulated that this pattern of expression reflects a more global pattern of chlamydial gene expression (25). Congruent information is not yet available for transcription of C. pneumoniae sigma factor genes, but experiments are now under way to meet this need. The present study necessarily required selecting genes to study their transcriptional activity under various growth conditions. More complete analysis of C. pneumoniae and host cell transcription patterns will require microarray analyses. These studies are also in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AR-42541 and AI-44055 (A.P.H.) and AI 19782 and AI 42790 (G.I.B.).

G.I.B. and A.P.H. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beatty W L, Morrison R P, Byrne G I. Persistent chlamydiae: from cell culture to a paradigm for chlamydial pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:686–699. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.686-699.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beatty W L, Morrison R P, Byrne G I. Reactivation of persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in cell culture. Infect Immun. 1995;63:199–205. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.199-205.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blythe M J, Katz B P, Batteiger B E, Ganser J A, Jones R B. Recurrent genitourinary chlamydial infection in sexually active female adolescents. J Pediatr. 1992;121:487–493. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81812-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bremer H, Churchwood G. Control of cyclic chromosome replication in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:459–475. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.459-475.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donachie W D. The cell cycle of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;18:6713–6721. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerard H C, Whittum-Hudson J A, Hudson A P. Genes required for assembly and function of the protein synthetic system in Chlamydia trachomatis are expressed early in elementary to reticulate body transformation. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;255:637–642. doi: 10.1007/s004380050538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gérard H C, Schumacher H R, El-Gabalawy H, Goldback-Mansky R, Hudson A P. Chlamydia pneumoniae infecting the human synovium are viable and metabolically active. Microb Pathog. 2000;29:17–24. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grayston J T. Background and current knowledge of Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:S402–S410. doi: 10.1086/315596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn D L, Dodge R W, Golubjatnikov R. Association of Chlamydia pneumoniae (strain TWAR) infection with wheezing, asthmatic bronchitis, and adult onset asthma. JAMA. 1991;266:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammerschlag M R, Chirgwin K, Roblin P M, Gelling M, Dumornay W, Mandel L, Smith P, Schachter J. Persistent infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae following acute respiratory illness. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:178–182. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harwood J, editor. Basic DNA and RNA protocols. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiratsuka M, Agatsuma Y, Mizugaki M. Rapid detection of CYP2C9*3 alleles by real time fluorescence PCR based on SYBR green. Genet Metab. 1999;68:357–362. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inman R D, Whittum-Hudson J A, Schumacher H R, Hudson A P. Chlamydia and associated arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:254–262. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalayoglu M V, Byrne G I. Induction of macrophage foam cell formation by Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:725–729. doi: 10.1086/514241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuo C-C, Shor A, Campbell L A, Fukushi H, Patton D L, Grayston J T. Demonstration of Chlamydia pneumoniae in atherosclerotic lesions of coronary arteries. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:841–849. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kutlin A, Roblin P M, Hammerschlag M R. In vitro activities of azithromycin and ofloxacin against Chlamydia pneumoniae in a continuous-infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2268–2272. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laitinen K, Laurila A L, Leinonen M, Saikku P. Reactivation of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in mice by cortisone treatment. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1488–1490. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1488-1490.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leitman T, Brooks D, Moncada J, Schachter J, Dawson C, Dean D. Chronic follicular conjunctivitis associated with Chlamydia psittaci or Chlamydia pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1335–1340. doi: 10.1086/516373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malinverni R, Kuo C-C, Campbell L A, Grayston J T. Reactivation of Chlamydia pneumoniae lung infection in mice by cortisone. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:593–594. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathews S A, Volp K M, Timms P. Development of a quantitative gene expression assay for Chlamydia trachomatis identified temporal expression of sigma factors. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:354–358. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta S J, Miller R D, Ramirez J A, Summersgill J T. Inhibition of Chlamydia pneumoniae replication in HEp-2 cells by interferon-γ: role of tryptophan catabolism. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1326–1331. doi: 10.1086/515287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saikku P, Leinonen M, Mattila K, Ekman M R, Nieminen M S, Makela P H, Huttunen J, Valtonen V. Serologic evidence of an association of a novel Chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988;ii:983–985. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephens R S. Molecular genetics of Chlamydia. In: Bowie W R, Caldwell H D, Chernesky M A, et al., editors. Chlamydial infections. Bologna, Italy: Societa Editrice Esculapio; 1994. pp. 377–386. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Timms P, Mathews S. Gene regulation in Chlamydia. Proc Eur Soc Chlamydia Res. 2000;4:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinstock H, Dean D, Bolan G. Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1994;8:797–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]