Abstract

Given the popularity of social media and the growing presence of these tools in the daily lives of individuals, research about the elements that can be linked to their problematic use appears to be of great importance. The objective of this study was to investigate the factors that may contribute to the levels of social media addiction, by focusing on the role of alexithymia, body image concern, and self-esteem, controlled for age and gender. A sample of 437 social media users (32.5% men, 67.5% women; Mage = 33.44 years, SD = 13.284) completed an online survey, including the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale, Body Image Concern Inventory, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale, together with a demographic questionnaire. Results showed a significant association between alexithymia and social media addiction, with the total mediation of body image concern (and more in detail, body dissatisfaction) and the significant moderation of self-esteem. Gender and age showed significant effects in these relationships. Such findings may offer further insights into the field of clinical research on social media addiction and may provide useful information for effective clinical practice.

Keywords: addiction, behavioral addiction, technological addiction, problematic social media use, body image, body dissatisfaction, body image concern, body dysmorphism, alexithymia, self-esteem

1. Introduction

In the last years, the use of social media has grown exponentially, becoming an integral part of everyday life for many individuals [1,2,3]. In fact, social media are online platforms that allow you to engage in many types of entertainment and social activities, for example, by socializing, creating content and interacting with that of others, and looking for information, without geographical or temporal constraints [4,5,6]. Although the scientific literature highlights a potential positive role of this medium on psychological well-being [7], attention has also been paid to some problematic outcomes that may affect some individuals, who may develop an addiction [8,9]. Social media addiction is a behavioral addiction linked to the use of technologies [10] defined as “being overly concerned about social media, driven by an uncontrollable motivation to log on to or use social media, and devoting so much time and effort to social media that it impairs other important life areas” (p. 4054) [11]. The symptoms of this condition include salience, tolerance, conflict, withdrawal, relapse, and mood modification [9,12], and this condition has been associated with higher levels of stress [13], depression [14], anxiety [15], sleep disorders [16], interpersonal problems [17], decreased work performance [18], and a lower life satisfaction [19].

Given the clinical relevance of this disease and its associated problems, the scientific literature has placed a growing focus on the exploration of risk and of the protective factors for this addiction (see Sun and Zhang [20] for a review). Studying the underlying elements of this pathological condition can provide valuable insights to identify the populations most at risk towards which to direct preventive interventions, on the one hand. On the other hand, it can support the efficacy of the clinical practice, expanding helpful knowledge to develop personalized therapeutic interventions on the characteristics of the subjects and targeted on the variables having a significant role in protecting or increasing the risk of resulting in problematic social media use. In this line, the present research examined the factors that may intervene in contributing to the levels of social media addiction, by focusing on the role of alexithymia, body image concern, and self-esteem.

Alexithymia is a multidimensional construct that falls within the framework of emotional dysregulation, and is characterized by a reduced ability to identify and describe feelings, difficulty in distinguishing feelings from bodily sensations, constrained imaginative processes, and poor introspective thinking [21,22]. It has been linked to both physical [23,24] and mental [25,26] illness, as well as the tendency to seek external regulation of one’s emotions through compulsive behaviors [21]. Consistently, scientific research has indeed highlighted its central role in contributing to vulnerability to the addiction onset [27] and its severity [28], whether it is substance abuse or problematic behavior [29,30]. More in detail, previous evidence also supports its association with technological addictions, including online gambling [31], problematic smartphone use [32], and, specifically, social media addiction [33].

Parallelly, the difficulty in identifying and symbolizing emotional experiences, as well as in distinguishing feelings from bodily sensations, can contribute to a perception of emotional emptiness, which in turn, may favor an exaggerated focus on the physical details of one’s body and an erroneous and distorted interpretation of one’s own body image [34,35]. In fact, previous evidence shows a significant and positive association between alexithymia and body image concern [36]. The body image construct refers to the perception and evaluation of individuals on their bodies [34]. On the other hand, dysmorphic concern is characterized by “intense concern about, and preoccupation with, a perceived defect in appearance, excessive checking or camouflaging of the defect, social avoidance, and reassurance seeking” [37] (p. 229). Previous evidence highlighted the negative influence of a negative perception of one’s body image on mental health, showing negative associations with depression [38], social anxiety [39], eating disorders [40], and exercise addiction [41], to name a few. Furthermore, recent research found relationships between body dissatisfaction and internet addiction [42], problematic smartphone use [43], and social media addiction [44], supporting the possibility that the use of the internet can represent a coping mechanism (maladaptive) aimed at temporary escape from unpleasant dysregulated feelings and negative perceptions of oneself, which in the long term may hesitate in addiction [45,46].

In this framework, it is not surprising that self-esteem has presented negative associations with social media addiction [19]. Self-esteem could be defined as a global evaluation of oneself that determines a positive or negative attitude towards the self [47]. It has been related to high mental health [48] and, in the field of addiction, it has negative relationships with substance use [49], gambling disorder [50], and exercise addiction [41], as well as technological addictions, such as internet addiction [51], internet gaming disorder [52], and problematic smartphone use [53]. In light of this evidence, the deepening of the protective role of self-esteem on social media addiction appears relevant, by exploring not only the direct associations between these two constructs but also the moderating effects of self-esteem in the relationships between other intervening factors. Investigating this aspect, in fact, could offer interesting insights of practical and clinical relevance.

Given the aforementioned evidence, this research investigated the relationships between factors that may influence the levels of social media addiction, focusing on alexithymia, body image concern, and self-esteem. To achieve this goal, a moderated mediation model was implemented, hypothesizing that:

H1.

Alexithymia will be positively associated with social media addiction;

H2.

Body image concern will mediate the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction;

H3.

Self-esteem will be a significant moderator in the model.

Since previous studies have shown the influence of age and gender on the considered variables [54,55], these factors were controlled as covariates to test the solidity of the interactions hypothesized in the model.

Finally, the role of body image concern was deepened, by implementing a second model exploring the parallel mediation of the body image concern subdimensions (dysmorphic symptoms and symptom interference) in the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction, further investigating the moderation of self-esteem, and controlling for the effects of gender and age.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

A sample of 437 social media users (32.5% men; 67.5% women) was involved in this research (see Table 1). Their mean age was 33.44 years (SD = 13.284), and most of them declared themselves to be single (59.5%), employees (36.4%), and have a high school diploma (36.6%). They were recruited online, by posting a link to the survey hosted on the Google Form platform. Participation was voluntary, and anonymity and privacy were guaranteed. Each participant was informed of the general objective of the research and provided electronically informed consent before starting the compilation. All the procedures of this research were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Integrated Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Institute (IPPI; protocol code 006/2022).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale

The Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) [56] is a six-item self-report measure used to assess the levels of problematic social network use, according to the conceptualization of the components model of behavioral addiction [12]. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (“very rarely”) to 5 (“very often”). The Italian version [57] was used in this research, showing good internal consistency in the present sample (α = 0.80).

2.2.2. Body Image Concern Inventory

The Body Image Concern Inventory (BICI) [37] is a 19-item self-report measure used to assess dysmorphic body image concerns. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“always”), and may be grouped into two subdimensions: dysmorphic symptoms and symptom interference. Both the total score and the subscales of the Italian version [55] were used in this research, showing good internal consistency in the present sample (total score, α = 0.94; dysmorphic symptoms, α = 0.93; symptom interference α = 0.75).

2.2.3. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [58] is a 10-item self-report measure used to assess the levels of personal self-esteem. Items are rated on a four-point Likert scale, from 0 (“strongly disagree”) to 3 (“strongly agree”). The Italian version [59] was used in this research, showing good internal consistency in the present sample (α = 0.89).

2.2.4. Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale

The Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) [60,61] is a 20-item self-report measure used to assess the levels of alexithymia. Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), and may be grouped into three subdimensions: difficulty identifying feelings; difficulty describing feelings; externally oriented thinking. The total score of the Italian version [62] was used in this research, showing good internal consistency in the present sample (α = 0.82).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 437).

| Characteristics | M ± SD | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 33.44 ± 13.284 | ||

| Sex | |||

| Males | 142 (32.5%) | ||

| Females | 295 (67.5%) | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 260 (59.5%) | ||

| Married | 79 (18.1%) | ||

| Cohabiting | 81 (18.5%) | ||

| Separated | 3 (0.7%) | ||

| Divorced | 12 (2.7%) | ||

| Widowed | 2 (0.5%) | ||

| Education | |||

| Middle School diploma | 17 (3.9%) | ||

| High School diploma | 160 (36.6%) | ||

| University degree | 115 (26.3%) | ||

| Master’s degree | 108 (24.7%) | ||

| Post-lauream specialization | 37 (8.5%) | ||

| Occupation | |||

| Student | 103 (23.6%) | ||

| Working student | 59 (13.5%) | ||

| Artisan | 6 (1.4%) | ||

| Employee | 159 (36.4%) | ||

| Entrepreneur | 13 (3.0%) | ||

| Freelance | 39 (8.9%) | ||

| Homemaker | 11 (2.5%) | ||

| Manager | 5 (1.1%) | ||

| Trader | 2 (0.5%) | ||

| Retired | 22 (5.0%) | ||

| Unemployed | 18 (4.1%) | ||

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS (v. 21.0; IBM, New York, NY, USA) software for Windows. Pearson correlation was used to examine the association between the variables. Then, two moderated mediation models were tested, by using the macro-program PROCESS 3.4 (Model 59) [63]. The first one was implemented to examine the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction with the mediation of body image concern, also exploring the moderating role of self-esteem. The second model investigated the parallel mediation of the two body image concern subdimensions (dysmorphic symptoms and symptom interference) in the association between alexithymia and social media addiction, further exploring the moderating role of self-esteem. In both the models, it was controlled for gender (men coded as 0 and women coded as 1) and age as possible covariates. To probe the statistical stability of the models, the Johnson–Neyman procedure [64] and the bootstrap technique (5000 bootstrapped samples with 95% CI) [65] were used. The Johnson–Neyman procedure [64] allows the assessing of the conditional indirect effects of alexithymia on social media addiction at the three levels of self-esteem, i.e., −1 SD mean, +1 SD. The bootstrap technique provides bootstrapped confidence intervals (from boot LLCI to boot ULCI), which support the significance of the effect when they do not include zero [65]. Finally, the evaluation of the final moderated mediation model was enriched by examining the R2 index, such that: R2 < 0.02 = very weak effect; 0.02–0.12 = weak effect; 0.13–0.26 = moderate effect; R2 > 0.26 = substantial effect [66].

3. Results

The correlation analysis showed significant associations among the variables (see Table 2). Specifically, social media addiction was significantly and positively correlated with alexithymia (r = 0.348, p < 0.01), body image concerns (r = 0.481, p < 0.01), dysmorphic symptoms (r = 0.474, p < 0.01), and symptom interference (r = 0.378, p < 0.01). Parallelly, social media addiction was significantly and negatively related to self-esteem (r = −0.369, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social media addiction | 1 | 0.384 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.378 ** | −0.369 ** |

| 2. Alexithymia | 1 | 0.471 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.408 ** | −0.546 ** | |

| 3. Body image concerns | 1 | 0.990 ** | 0.773 ** | −0.563 ** | ||

| 4. Dysmorphic symptoms | 1 | 0.676 ** | −0.547 ** | |||

| 5. Symptom interference | 1 | −0.485 ** | ||||

| 6. Self-esteem | 1 |

Note: Bold values indicate significant p-values. **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

A significant and positive total effect was found in the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction (β = 0.33, p < 0.001; BootLLCI = 0.0978; BootULCI = 0.1702; H1), controlling for age (β = −0.32, p < 0.001; BootLLCI = −0.1419; BootULCI = −0.0845), and gender (β = 0.14, p < 0.001; BootLLCI = 0.6202; BootULCI = 2.2295).

As shown in the first moderated mediation model, alexithymia was also significantly and positively associated with body image concern (β = 0.44, p < 0.001; BootLLCI = 0.2852; BootULCI = 0.8585), which in turn, was significantly and positively related to social media addiction (β = 0.65, p < 0.001; BootLLCI = 0.0855; BootULCI = 0.3193; H2). Furthermore, self-esteem significantly moderated the association between body image concern and social media addiction (H3): ∆R2 = 0.010, F(1, 429) = 6.290, p < 0.05. This data was further detailed by exploring the conditional indirect effects of alexithymia on social media addiction at three levels of the moderator (−1 SD, mean, +1 SD): the effect was significant at lower (estimate = 0.043; BootLLCI = 0.0218; BootULCI = 0.0681) or medium (estimate = 0.023; BootLLCI = 0.0107; BootULCI = 0.0392) levels of self-esteem, and became non-significant at higher levels of self-esteem (estimate = 0.009; BootLLCI = −0.0026; BootULCI = 0.0243). With regards to the covariates, being female was associated with higher levels of body image concerns (β = 0.22, p < 0.001; BootLLCI = 4.7926; BootULCI = 9.3005) and showed no significant relationship with social media addiction (p = 0.165; BootLLCI = −0.2390; BootULCI = 1.4025), unlike age, which was significantly and negatively related to both the variables (β = −0.16, p < 0.001, BootLLCI = −0.2514, BootULCI = −0.1028 and β = −0.26, p < 0.001, BootLLCI = −0.1188, BootULCI = −0.0620, respectively). Finally, when the mediation of body image concert with the moderation of self-esteem and the effect of gender and age were considered in the model, the direct effect in the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction became non-significant (β = 0.30, p = 0.077; BootLLCI = −0.0160; BootULCI = 0.2673), suggesting for a fully moderated mediation explaining the 35% of the variance (a substantial effect): R2 = 0.346, F(7, 429) = 22.417, p < 0.001.

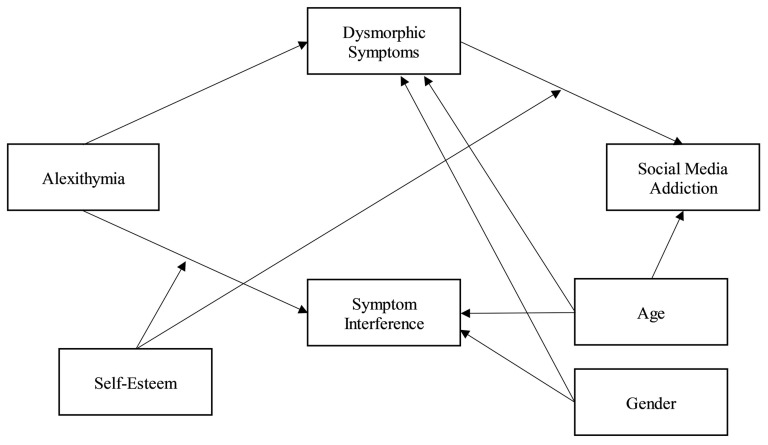

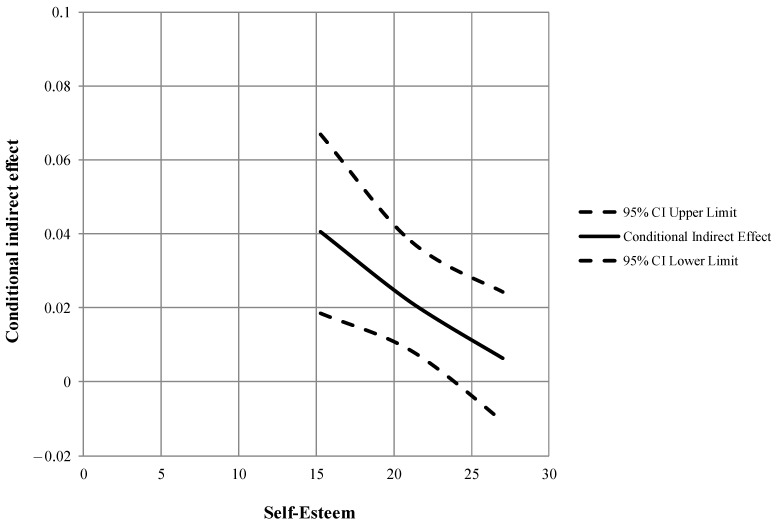

Concerning the results of the second moderated mediation model (see Figure 1), alexithymia was significantly and positively associated with the body image concerns subdimensions (dysmorphic symptoms, β = 0.35, p < 0.05; symptom interference, β = 0.75, p < 0.001). Furthermore, self-esteem significantly moderated the relationship between alexithymia and symptom interference, such that as self-esteem levels increased, the association between alexithymia and symptomatic interference weakened: ∆R2 = 0.024, F(1, 431) = 15.149, p < 0.001. Then, dysmorphic symptoms were significantly and positively related to social media addiction (β = 0.76, p < 0.001), unlike symptom interference (β = −1.00, p = 0.596). In addition, the relationship between dysmorphic symptoms and social media addiction was significantly moderated by self-esteem: ∆R2 = 0.010, F(1, 427) = 6.368, p < 0.05. This data was further detailed by exploring the conditional indirect effects of alexithymia on social media addiction at three levels of the moderator (−1 SD, mean, +1 SD; see Figure 2): the effect was significant at lower (estimate = 0.041; BootLLCI = 0.0185; BootULCI = 0.0669) or medium (estimate = 0.022; BootLLCI = 0.0083; BootULCI = 0.0378) levels of self-esteem, and became non-significant at higher levels of self-esteem (estimate = 0.006; BootLLCI = −0.0107; BootULCI = 0.0242).

Figure 1.

The association between alexithymia and social media addiction, exploring the role of dysmorphic symptoms, symptoms interference, and self-esteem, controlling for age and gender: a moderated mediation model. Note: Only the emerged significant relationships have been graphically represented.

Figure 2.

Conditional indirect effect of alexithymia on social media addiction at values of the moderator self-esteem through dysmorphic symptoms.

With regards to the covariates, being female was associated with higher levels of dysmorphic symptoms (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) and symptom interference (β = 0.13, p < 0.01), and showed no significant relationship with social media addiction (p = 0.196), unlike age which was significantly and negatively related to both the body image concern subdimensions (dysmorphic symptoms, β = 0.17, p < 0.001; symptom interference, β = −0.09, p < 0.05) and social media addiction (β = −0.26, p < 0.001). Finally, when the mediation and moderation effects, as well as the influence of gender and age, were considered in the model, the direct effect in the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction became non-significant (β = 0.34, p = 0.056), suggesting for a fully moderated mediation explaining the 35% of the variance (a substantial effect): R2 = 0.348, F(9, 427) = 25.370, p < 0.001.( see Table 3)

Table 3.

Unstandardized coefficients and 95% bias-corrected confidence interval of the totally moderated mediation model.

| Antecedent | Consequent | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | Y | ||||||||||

| Coeff. | SE | p | 95% BootCI | Coeff. | SE | p | 95% BootCI | Coeff. | SE | p | 95% BootCI | |

| X | 0.387 | 0.151 | 0.011 | [0.1409; 0.6316] | 0.185 | 0.036 | <0.001 | [0.1014; 0.2661] | 0.137 | 0.071 | 0.053 | [−0.0033; 0.2848] |

| W | −0.457 | 0.339 | 0.178 | [−1.0178; 0.1050] | 0.146 | 0.081 | 0.073 | [−0.0339; 0.3207] | 0.399 | 0.139 | 0.004 | [0.1255; 0.6646] |

| X * W | −0.006 | 0.007 | 0.384 | [−0.0175; 0.0051] | −0.007 | 0.002 | <0.001 | [−0.0100; −0.0029] | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.406 | [−0.0095; 0.0036] |

| M1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.279 | 0.079 | <0.001 | [0.1090; 0.4503] |

| M2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.164 | 0.309 | 0.596 | [−0.7710; 0.4180] |

| M1 * W | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.009 | 0.004 | 0.012 | [−0.0174; −0.0013] |

| M2 * W | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.010 | 0.016 | 0.052 | [−0.0193; 0.0418] |

| C1 | −0.160 | 0.037 | <0.001 | [−0.2256; −0.0933] | −0.018 | 0.009 | 0.040 | [−0.0308; −0.0042] | −0.090 | 0.015 | <0.001 | [−0.1174; −0.0612] |

| C2 | 6.232 | 1.018 | <0.001 | [4.1992; 8.1766] | 0.783 | 0.244 | 0.002 | [0.2931; 1.2398] | 0.536 | 0.414 | 0.196 | [−0.2488; 1.3410] |

| Constant | 290.494 | 80.134 | <0.001 | [16.2017; 43.3204] | −0.088 | 10.952 | 0.964 | [−4.4608; 4.5435] | −10.083 | 30.339 | 0.746 | [−7.2095; 5.1512] |

|

R2 = 0.418; F(5, 431) = 61.906, p < 0.001 |

R2 = 0.318; F(5, 431) = 40.252, p < 0.001 |

R2 = 0.348; F(9, 427) = 25.380, p < 0.001 |

||||||||||

Note: SE = standard error; Coeff = unstandardized coefficient; 95% BootCI = 95% bias-corrected confidence interval; X = alexithymia; M1 = dysmorphic symptoms; M2 = symptom interference; W = self-esteem; C1 = age; C2 = gender; Y = social media addiction.

4. Discussion

Given the rapid spread and popularity of social media [67], the scientific community is vigilant and active in investigating how the use of these tools can promote subjective well-being or, on the contrary, lead to problematic behaviors and disorders [68]. The present study fits into this line of research, focusing on the factors that may be associated with social media addiction by investigating the role of alexithymia, body image concern, and self-esteem, controlling for age and gender.

First, results showed a significant association between alexithymia and social media addiction, supporting the first hypothesis (H1). This is in line with previous evidence [69] and research on other technological addictions [70], further confirming the role of alexithymia as a risk factor for addiction [27,30] and, more generally, for psychopathology [71,72]. On the other hand, the data showed that the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction was significantly and totally mediated by body image concern, according to the second hypothesis (H2). Indeed, alexithymic individuals tend to have reduced social skills, more difficulties in establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships, lower perception of social support, and higher levels of anxiety in relational interactions [73,74], and can therefore perceive themselves as undesirable and physically inadequate [35]. From this perspective, social media can be seen as a safer and less risky context for developing relationships [75]. Indeed, the results of this research highlighted the significance of this indirect path only for subjects with lower levels of self-esteem, who played the role of moderator in the relationship between body image concern and social media addiction, in line with the third hypothesis (H3). This is consistent with previous evidence finding a significant mediation effect of self-esteem in the indirect path toward behavioral addiction [36,41] and showing that higher levels of self-esteem were associated with a lower perception of the importance of social media and a lower intensity of use [76]. Therefore, the data of this study suggest that individuals with lower self-esteem may rely on social media to compensate for their emotional and social deficiencies by seeking reassurance and socialization, risking more of developing an addiction to them [77].

Such findings were further investigated in the second model (see Figure 1), showing that the mediation of body image concern in the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction was mainly explained by the significant effect of the dysmorphic symptoms subdimension, with the moderation of self-esteem. This data can be read considering that social media provides more control over self-presentation than face-to-face interactions [78], offering subjects with lower self-esteem the possibility to selectively share positive aspects of themselves to compensate for dissatisfaction with their own body [79]. In fact, previous evidence showed that subjects with higher body dissatisfaction tend to have a higher positive self-presentation on social media [80]. Therefore, social media becomes a compensatory solution to satisfy the psychological needs of individuals, limiting, however, the possibility of developing more adaptive strategies and increasing the levels of dependence on these tools [81].

Finally, the role of gender and age as potential confounders was controlled in performing both models. Concerning gender, it showed a significant effect on social media addiction when considered as a confounder of the total effect between alexithymia and social media addiction, in line with previous results, supporting that women present higher levels of problematic social media use than men [82]. However, when body image concern or its subdimensions were inserted in the models, being female was significantly associated with these factors and the direct effect on social media addiction became non-significant. These data provided further evidence of the greater risk of experiencing higher levels of body dysmorphism in women [55], and further detailed the scientific literature concerning the relationship between gender and social media addiction (e.g., [54]). With regards to age, older participants showed lower levels of both social media addiction and body image concern (or its subdimensions). Indeed, previous research highlighted that young people are more dedicated to using social media, increasing the risk of developing an addiction [83,84]. Furthermore, the relationship between body image concern and age was consistent with recent longitudinal research showing that satisfaction increased across the lifespan, both for men and women [85].

The present study also has some limitations that should be highlighted. First, the cross-sectional design of this study implies the need to be cautious in interpreting the causal links between the variables, however solidly based on the scientific literature. Longitudinal research is required to provide further evidence of these relationships. Furthermore, only self-report measures were used. The application of a multimethod approach (e.g., by integrating self-report measures with interviews) could be a strategy for future research to overcome the well-known method biases linked to self-reported data collection. Finally, a non-clinical sample was involved in this study. Although the conducted analyses allow for a dimensional approach, future research could replicate these models in clinical samples to confirm these results.

Despite these limitations, the results of this research may provide helpful insights for mental health professionals to elaborate tailored and personalized interventions. First, the association between social media addiction and body image concern has been further detailed, by considering the latter not only in its total dimension but also in its constitutive subdimensions [37]. This allowed highlighting the role of body dysmorphism, providing more specific information to favor a better understanding of the disorder. Furthermore, the results suggest the importance of evaluating the levels of alexithymia in subjects with social media addiction and the possibility of focusing on this aspect of the clinical intervention especially those who, precisely, also present body dysmorphism, confirming the importance of maintaining research attention on the study of alexithymia and emotional dysregulation in the field of addiction [27,30]. Finally, supporting the possibility of elaborating precise interventions both for clinical and preventive activities, the results also highlight a greater strength of the relationships between the risk factors for social media addiction in subjects with low self-esteem, in young people, and in women. Therefore, these data provide information on a specific target to which interventions should be directed, favoring their effectiveness and maximizing the available resources.

5. Conclusions

Although the use of the internet offers multiple opportunities and benefits, such as maintaining social relationships [4], remote working [86], and online therapy [87], to name a few, for some individuals this means also exposes them to the risk of developing technological addictions [88]. This study focused on social media addiction, highlighting the contribution of alexithymia, body image concern, and self-esteem through a moderated mediation model. The results offer interesting insights for clinical practice. Specifically, it should be noted that the relationship between alexithymia and social media addiction is totally mediated by body image concern (and, more specifically, by body dysmorphism), highlighting, however, that this path was significant only for subjects with lower self-esteem levels. This data has important practical implications for the planning of treatment interventions. In fact, although alexithymia and body image concern showed positive responses to therapy [89,90], the results of this study highlight the importance of working above all on self-esteem levels to limit the effect of these factors on social media addiction. Finally, the analysis of the confounders has made it possible to identify specific populations that may be most at risk, that is, women and younger subjects, towards which to direct any preventive activities. In conclusion, taken together these data offer further insights into the field of clinical research on social media addiction and may provide useful information for effective clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.; methodology, A.G. and E.T.; formal analysis, A.G. and E.T.; investigation, A.G.; data curation, A.G. and E.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G. and E.T.; writing—review and editing, A.G. and E.T.; supervision, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Integrated Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Institute (IPPI; protocol code 006/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Ho S.S., Lwin M.O., Lee E.W. Till logout do us part? Comparison of factors predicting excessive social network sites use and addiction between Singaporean adolescents and adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;75:632–642. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kizgin H., Jamal A., Dey B.L., Rana N.P. The impact of social media on consumers’ acculturation and purchase intentions. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018;20:503–514. doi: 10.1007/s10796-017-9817-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuss D.J., Griffiths M.D. Online Social Networking and Addiction—A Review of the Psychological Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2011;8:3528–3552. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8093528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treem J.W., Dailey S.L., Pierce C.S., Biffl D. What we are talking about when we talk about social media: A framework for study. Sociol. Compass. 2016;10:768–784. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng C., Lau Y.C., Luk J.W. Social capital–accrual, escape-from-self, and time-displacement effects of internet use during the COVID-19 stay-at-home period: Prospective, quantitative survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e22740. doi: 10.2196/22740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan T., Chester A., Reece J., Xenos S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2014;3:133–148. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verduyn P., Ybarra O., Résibois M., Jonides J., Kross E. Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2017;11:274–302. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carbonell X., Panova T. A critical consideration of social networking sites’ addiction potential. Addict. Res. Theory. 2017;25:48–57. doi: 10.1080/16066359.2016.1197915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuss D.J., Griffiths M.D. Social Networking Sites and Addiction: Ten Lessons Learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14:311. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Błachnio A., Przepiorka A. Personality and positive orientation in Internet and Facebook addiction. An empirical report from Poland. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;59:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreassen C., Pallesen S. Social network site addiction–An overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014;20:4053–4061. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J. Subst. Use. 2005;10:191–197. doi: 10.1080/14659890500114359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain Z., Griffiths M.D. Problematic social networking site use and comorbid psychiatric disorders: A systematic review of recent large-scale studies. Front. Psychiatry. 2018;9:686. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keles B., McCrae N., Grealish A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth. 2020;25:79–93. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu C., Ma J. Social media addiction and burnout: The mediating roles of envy and social media use anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 2020;39:1883–1891. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9998-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong H.Y., Mo H.Y., Potenza M.N., Chan M.N.M., Lau W.M., Chui T.K., Pakpour A.H., Lin C.-Y. Relationships between Severity of Internet Gaming Disorder, Severity of Problematic Social Media Use, Sleep Quality and Psychological Distress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:1879. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17061879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller K.W., Dreier M., Beutel M.E., Duven E., Giralt S., Wölfling K. A hidden type of internet addiction? Intense and addictive use of social networking sites in adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;55:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan N.A., Khan A.N., Moin M.F. Self-regulation and social media addiction: A multi-wave data analysis in China. Technol. Soc. 2021;64:101527. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawi N.S., Samaha M. The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2017;35:576–586. doi: 10.1177/0894439316660340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Y., Zhang Y. A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research. Addict. Behav. 2021;114:106699. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor G.J., Bagby R.M., Parker J.D. The alexithymia construct: A potential paradigm for psychosomatic medicine. Psychosomatics. 1991;32:153–164. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(91)72086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor G.J. Recent developments in alexithymia theory and research. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2000;45:134–142. doi: 10.1177/070674370004500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrozzino D., Porcelli P. Alexithymia in gastroenterology and hepatology: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:470. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martino G., Caputo A., Vicario C.M., Catalano A., Schwarz P., Quattropani M.C. The relationship between alexithymia and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:2026. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sagar R., Talwar S., Desai G., Chaturvedi S.K. Relationship between alexithymia and depression: A narrative review. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2021;63:127. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_738_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westwood H., Kerr-Gaffney J., Stahl D., Tchanturia K. Alexithymia in eating disorders: Systematic review and meta-analyses of studies using the Toronto Alexithymia Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2017;99:66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gori A., Topino E., Craparo G., Bagnoli I., Caretti V., Schimmenti A. A comprehensive model for gambling behaviors: Assessment of the factors that can contribute to the vulnerability and maintenance of gambling disorder. J. Gambl. Stud. 2022;38:235–251. doi: 10.1007/s10899-021-10024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gori A., Topino E., Cacioppo M., Craparo G., Schimmenti A., Caretti V. An addictive disorders severity model: A chained mediation analysis using structural equation modeling. J. Addict. Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1080/10550887.2022.2074762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craparo G., Ardino V., Gori A., Caretti V. The relationships between early trauma, dissociation, and alexithymia in alcohol addiction. Psychiatry Investig. 2014;11:330–335. doi: 10.4306/pi.2014.11.3.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caretti V., Gori A., Craparo G., Giannini M., Iraci-Sareri G., Schimmenti A. A New Measure for Assessing Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders: The Addictive Behavior Questionnaire (ABQ) J. Clin. Med. 2018;7:194. doi: 10.3390/jcm7080194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topino E., Gori A., Cacioppo M. Alexithymia, Dissociation, and Family Functioning in a Sample of Online Gamblers: A Moderated Mediation Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:13291. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang H., Wan X., Lu G., Ding Y., Chen C. The Relationship Between Alexithymia and Mobile Phone Addiction Among Mainland Chinese Students: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry. 2022;13:754542. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.754542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martingano A.J., Konrath S., Zarins S., Okaomee A.A. Empathy, narcissism, alexithymia, and social media use. Psychol. Pop. Media. 2022;11:413–422. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iacolino C., Pellerone M., Formica I., Lombardo E.M.C., Tolini G. Alexithymia, body perception and dismorphism: A study conducted on sportive and non-sportive subjects. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2017;14:400–406. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Berardis D., Serroni N., Campanella D., Carano A., Gambi F., Valchera A., Conti C., Sepede G., Caltabiano M., Pizzorno A.M., et al. Alexithymia and its relationships with dissociative experiences, body dissatisfaction and eating disturbances in a non-clinical female sample. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2009;33:471–479. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9247-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gori A., Topino E., Pucci C., Griffiths M.D. The Relationship between Alexithymia, Dysmorphic Concern, and Exercise Addiction: The Moderating Effect of Self-Esteem. J. Pers. Med. 2021;11:1111. doi: 10.3390/jpm11111111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Littleton H.L., Axsom D., Pury C.L. Development of the body image concern inventory. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005;43:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao Y., Knoesen N.P., Deng Y., Tang J., Castle D.J., Bookun R., Hao W., Chen X., Liu T. Body dysmorphic disorder, social anxiety and depressive symptoms in Chinese medical students. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010;45:963–971. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang A., Hofmann S.G. Relationship between social anxiety disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:1040–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kollei I., Schieber K., de Zwaan M., Svitak M., Martin A. Body dysmorphic disorder and nonweight-related body image concerns in individuals with eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013;46:52–59. doi: 10.1002/eat.22067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gori A., Topino E., Griffiths M.D. Protective and Risk Factors in Exercise Addiction: A Series of Moderated Mediation Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:9706. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leménager T., Hoffmann S., Dieter J., Reinhard I., Mann K., Kiefer F. The links between healthy, problematic, and addicted Internet use regarding comorbidities and self-concept-related characteristics. J. Behav. Addict. 2018;7:31–43. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emirtekin E., Balta S., Sural İ., Kircaburun K., Griffiths M.D., Billieux J. The role of childhood emotional maltreatment and body image dissatisfaction in problematic smartphone use among adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:634–639. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen R., Newton-John T., Slater A. The relationship between Facebook and Instagram appearance-focused activities and body image concerns in young women. Body Image. 2017;23:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masur P.K., Reinecke L., Ziegele M., Quiring O. The interplay of intrinsic need satisfaction and Facebook specific motives in explaining addictive behavior on Facebook. Comput. Human Behav. 2014;39:376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walburg V., Mialhes A., Moncla D. Does school-related burnout influence problematic Facebook use? Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016;61:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Wesleyan University Press; Middletown, CT, USA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harter S. The Construction of the Self: Developmental and Sociocultural Foundations. Guilford Publications; New York, NY, USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamme Peterson C., Buser T.J., Westburg N.G. Effects of familial attachment, social support, involvement, and self-esteem on youth substance use and sexual risk taking. Fam. J. 2010;18:369–376. doi: 10.1177/1066480710380546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi J., Kim K. The Relationship between Impulsiveness, Self-Esteem, Irrational Gambling Belief and Problem Gambling Moderating Effects of Gender. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:5180. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bozoglan B., Demirer V., Sahin I. Loneliness, self-esteem, and life satisfaction as predictors of Internet addiction: A cross-sectional study among Turkish university students. Scand. J. Psychol. 2013;54:313–319. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beard C.L., Haas A.L., Wickham R.E., Stavropoulos V. Age of initiation and internet gaming disorder: The role of self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017;20:397–401. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2017.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Servidio R. Fear of missing out and self-esteem as mediators of the relationship between maximization and problematic smartphone use. Curr. Psychol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01341-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stănculescu E., Griffiths M.D. Social media addiction profiles and their antecedents using latent profile analysis: The contribution of social anxiety, gender, and age. Telemat. Inform. 2022;74:101879. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2022.101879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luca M., Giannini M., Gori A., Littleton H. Measuring dysmorphic concern in Italy: Psychometric properties of the Italian Body Image Concern Inventory (I-BICI) Body Image. 2011;8:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andreassen C.S., Billieux J., Griffiths M.D., Kuss D.J., Demetrovics Z., Mazzoni E., Pallesen S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2016;30:252–262. doi: 10.1037/adb0000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Monacis L., De Palo V., Griffiths M.D., Sinatra M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J. Behav. Addict. 2017;6:178–186. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenberg M. Conceiving the Self. Basic Books; New York, NY, USA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Prezza M., Trombaccia F.R., Armento L. La scala dell’autostima di Rosenberg: Traduzione e validazione Italiana [The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Italian translation and validation] Giunti Organ. Spec. 1997;223:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bagby R.M., Parker J.D., Taylor G.J. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale—I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994;38:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bagby R.M., Taylor G.J., Parker J.D. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale–II. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994;38:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bressi C., Taylor G., Parker J., Bressi S., Brambilla V., Aguglia E., Allegranti I., Bongiorno A., Giberti F., Bucca M., et al. Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: An Italian multicenter study. J. Psychosom. Res. 1996;41:551–559. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayes A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis Second Edition: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson P.O., Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Stat. Res. Mem. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Preacher K.J., Hayes A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ, USA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng C., Lau Y.C., Chan L., Luk J.W. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addict. Behav. 2021;117:106845. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keum B.T., Wang Y.W., Callaway J., Abebe I., Cruz T., O’Connor S. Benefits and harms of social media use: A latent profile analysis of emerging adults. Curr. Psychol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03473-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Youssef L., Hallit R., Akel M., Kheir N., Obeid S., Hallit S. Social media use disorder and alexithymia: Any association between the two? Results of a cross-sectional study among Lebanese adults. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care. 2021;57:20–26. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mahapatra A., Sharma P. Association of Internet addiction and alexithymia–A scoping review. Addict. Behav. 2018;81:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pinna F., Manchia M., Paribello P., Carpiniello B. The impact of alexithymia on treatment response in psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:311. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hemming L., Haddock G., Shaw J., Pratt D. Alexithymia and its associations with depression, suicidality, and aggression: An overview of the literature. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10:203. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lyvers M., Hanigan C., Thorberg F.A. Social interaction anxiety, alexithymia, and drinking motives in Australian university students. J. Psychoact. Drugs. 2018;50:402–410. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2018.1517228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Timoney L.R., Holder M.D. Correlates of alexithymia. In: Timoney L.R., Holder M.D., editors. Emotional Processing Deficits and Happiness. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2013. pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lyvers M., Cutinho D., Thorberg F.A. Alexithymia, impulsivity, disordered social media use, mood and alcohol use in relation to facebook self-disclosure. Comput. Human Behav. 2020;103:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Błachnio A., Przepiorka A., Rudnicka P. Narcissism and self-esteem as predictors of dimensions of Facebook use. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016;90:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saiphoo A.N., Halevi L.D., Vahedi Z. Social networking site use and self-esteem: A meta-analytic review. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2020;153:109639. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Casale S., Fioravanti G. Why narcissists are at risk for developing Facebook addiction: The need to be admired and the need to belong. Addict. Behav. 2018;76:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Melioli T., Rodgers R.F., Rodrigues M., Chabrol H. The role of body image in the relationship between Internet use and bulimic symptoms: Three theoretical frameworks. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015;18:682–686. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu Q., Sun J., Li Q., Zhou Z. Body dissatisfaction and smartphone addiction among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020;108:104613. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu Q.X., Fang X.Y., Wan J.J., Zhou Z.K. Need satisfaction and adolescent pathological internet use: Comparison of satisfaction perceived online and offline. Comput. Human Behav. 2016;55:695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kircaburun K., Alhabash S., Tosuntaş Ş.B., Griffiths M.D. Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the Big Five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020;18:525–547. doi: 10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Andreassen C.S., Torsheim T., Brunborg G.S., Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol. Rep. 2012;110:501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dailey S.L., Howard K., Roming S.M., Ceballos N., Grimes T. A biopsychosocial approach to understanding social media addiction. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020;2:158–167. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hockey A., Milojev P., Sibley C.G., Donovan C.L., Barlow F.K. Body image across the adult lifespan: A longitudinal investigation of developmental and cohort effects. Body Image. 2021;39:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Felstead A., Henseke G. Assessing the growth of remote working and its consequences for effort, well-being and work-life balance. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2017;32:195–212. doi: 10.1111/ntwe.12097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gori A., Topino E., Brugnera A., Compare A. Assessment of professional self-efficacy in psychological interventions and psychotherapy sessions: Development of the Therapist Self-Efficacy Scale (T-SES) and its application for eTherapy. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022;78:2122–2144. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bisen S.S., Deshpande Y.M. Understanding internet addiction: A comprehensive review. Ment. Health Rev. 2018;23:165–184. doi: 10.1108/MHRJ-07-2017-0023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Norman H., Marzano L., Coulson M., Oskis A. Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on alexithymia: A systematic review. Evid. Based Ment. Health. 2019;22:36–43. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2018-300029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Griffiths C., Williamson H., Zucchelli F., Paraskeva N., Moss T. A systematic review of the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for body image dissatisfaction and weight self-stigma in adults. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2018;48:189–204. doi: 10.1007/s10879-018-9384-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.