Abstract

Streptococcus gordonii is generally considered a benign inhabitant of the oral microflora, and yet it is a primary etiological agent in the development of subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE), an inflammatory state that propagates thrombus formation and tissue damage on the surface of heart valves. Strain FSS2 produced several extracellular aminopeptidase and fibrinogen-degrading activities during growth in culture. In this report we describe the purification, characterization, and cloning of a serine class dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase, an x-prolyl dipeptidyl-peptidase (Sg-xPDPP, for S. gordonii x-prolyl dipeptidyl-peptidase), produced in a pH-controlled batch culture. Purification of this enzyme by anion exchange, gel filtration, and hydrophobic interaction chromatography yielded a protein monomer of approximately 85 kDa, as shown by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under denaturing conditions. However, under native conditions, the protein appeared to be a homodimer on the basis of gel filtration and PAGE. Kinetic studies indicated that purified enzyme had a unique and stringent x-prolyl specificity that is comparable to both the dipeptidyl-peptidase IV/CD26 and lactococcal x-prolyl dipeptidyl-peptidase families. Nested PCR cloning from an S. gordonii library enabled the isolation and sequence analysis of the full-length gene. A 759-amino-acid polypeptide with a theoretical molecular mass of 87,115 Da and a calculated pI of 5.6 was encoded by this open reading frame. Significant homology was found with the PepX gene family from Lactobacillus and Lactococcus spp. and putative x-prolyl dipeptidyl-peptidases from other streptococcal species. Sg-xPDPP may serve as a critical factor for the sustained bacterial growth in vivo and furthermore may aid in the proteolysis of host tissue that is commonly observed during SBE pathology.

Streptococcus gordonii, classified in the Streptococcus mitis group of oral streptococci, is a well-studied member of the viridans family of streptococci (53). These primary colonizers serve a necessary role in the establishment of microbial communities that are characteristic of healthy dental plaque. Although considered benign inhabitants of the oral microflora, viridans members have been implicated in the systemic disease infective endocarditis (IE) (9, 26). The progression of this disease state requires (i) trauma (congenital or disease related) to the endothelial valve surface such that it is predisposed to colonization, (ii) adhesion of organisms to the modified valve surface after their entry into the bloodstream via the oral cavity, and (iii) the propagation of infected vegetation consisting of a fibrin-platelet meshwork (50). Despite the uniform susceptibility of these streptococci to β-lactam antibiotics and their lack of classical streptococcal virulence factors, they can cause life-threatening disease and/or chronic inflammation with periods of latency and several defined stages (10, 14)

The ability of these organisms to colonize biofilm surfaces at two distinct microenvironments has prompted studies of their dynamic metabolism and patterns of gene expression. Streptococcus sanguinis, studied as a model for viridans pathogenesis, expresses cell surface adhesins and platelet aggregation-associated proteins that facilitate both colonization and thrombosis at the infected lesion (12, 15). In addition, metabolic activities have been shown to dictate the availability of cell surface receptors manifested during the recruitment of planktonic bacteria to plaque or the attachment to a new biofilm surface (4, 12). Upon entry into the bloodstream, bacteria undergo a shift in pH from mildly acidic plaque (6.0 to 6.5) to the neutral pH (7.3) of the blood (41). In vivo expression technology was employed on the S. gordonii rabbit model of IE to detect genes activated in the new environment, with the alkaline shift in pH correlating with enhanced bacterial growth, upregulation of the msrA oxidative stress gene (52), and the induction of genes encoding carbohydrate metabolism enzymes, protein transporters, and cell surface proteins (22). The expression and secretion of glycosidase and peptidase activities, as examined in pH-controlled batch cultures, was found to be down-regulated by acid growth conditions and up-regulated by growth in a neutral pH environment supplemented with serum (13). Chemostat growth also uncovered a pH-dependent thrombin-like activity, which was considered more important in the tissue model than on tooth surfaces (32). This could reflect selective pressure for the organism to adapt novel enzymatic mechanisms for a changing environment.

It is presumed that S. gordonii obtains necessary protein nutrients from salivary glycoproteins in the oral cavity, while it utilizes plasma proteins when growing on heart surfaces. This use of plasma proteins by oral streptococci as carbon and nitrogen sources would ostensibly benefit growth in the vegetation. Certainly, proteolytic and peptide transport systems for viridans members have been described (1, 7, 17, 18, 25, 45, 54), and it has been shown that small peptides can be imported into S. sanguinis, while those exceeding size limitations would require further hydrolysis by endo- and exopeptidases present on the surface or secreted by these cells (8). One such activity that facilitates these metabolic requirements, a dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) with Gly-Pro-pNa hydrolyzing activity, has been detected in culture supernatant of S. gordonii (8, 19) yet has remained undefined. In this report we describe the purification, characterization, and cloning of a novel extracellular x-prolyl DPP that derives from S. gordonii FSS2 (Sg-xPDPP), a strain previously isolated from the bloodstream of a patient with subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

H-Gly-Pro-pNa, H-Arg-Pro-pNa, H-Ala-Ala-pNa, N-Suc-Gly-Pro-pNa, L-Pro-pNa, H-Gly-Arg-pNa, H-Gly-pNa, Sar-Pro-Arg-pNa, Di-isopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP), Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine-chloromethyl ketone (TLCK), Nα-p-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK), iodoacetamide, O-phenanthroline, aprotinin, bestatin, apstatin, β-mercaptoethanol, Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro-amide, sexual agglutination peptide, sleep-inducing peptide, substance P, des-Arg1 bradykinin, bradykinin, kallidin, lymphocyte-activating pentapeptide fragment, and fibrin polymerization inhibitor were obtained from Sigma. Pefabloc SC, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin, and E-64 were from Boehringer Mannheim. Z-Ala-Pro-pNa, H-Ala-Ala-pNa, H-Ala-Phe-pNa, H-Lys-pNa, H-Arg-pNa, protein kinase C fragment, Arg-Pro, and fibrin inhibitory peptide were from Bachem. Protein kinase C peptide was from American Peptide Company. Human RANTES, MIP-1β, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor were from PeproTech. H-Glu-(NHO-Bz) pyrollidide and diprotin A were from Calbiochem. α-1-Proteinase inhibitor and α-2-macroglobulin were gifts from Athens Research and Technology (Athens, Ga.).

Bacterial growth.

S. gordonii FSS2 (previously called S. sanguinis FSS2 [29]) was stored and maintained (at −80°C) as previously described (32). Frozen cells were inoculated into autoclaved medium containing 20 g of trypticase peptone (BBL)/liter, 5 g of yeast extract (Difco)/liter, 2 g of NaCl/liter, 0.1 g of CaCl2/liter, 4 g of K2HPO4/liter, and 1 g of KH2PO4/liter. Glucose (10 g/liter) and l-arginine (0.5 g/liter) were sterile filtered and subsequently added. A static culture (200 ml) was grown overnight at 37°C and used to inoculate a 4-liter starter culture, in turn used to inoculate a 15-liter stirred batch culture which was grown in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% N2 at 37°C with the pH held constant at 7.5 by addition of 5 M KOH using a pH controller (Cole Parmer). Cultures were harvested in early stationary phase at a point when the bacteria had metabolized all available glucose and the addition of base had ceased.

Enzymatic assay

Amidolytic activities of crude samples and purified protease were measured using the substrate H-Gly-Pro-pNa (1 mM final concentration) in assay buffer A (50 mM Tris, 1 mM CaCl2 [pH 7.8]) at 37°C. Assays were performed in 0.1 ml on 96-well plates using a thermostated microplate reader, and the release of p-nitroaniline was measured at 405 nm (Spectramax; Molecular Devices). Inhibition assays involved preincubation of pure enzyme with inhibitor for 10 min at 37°C followed by measurement of residual activity. Additional pNa substrates were treated identically.

Enzyme purification

Cell-free culture filtrate (14.5 liters) was obtained after centrifugation (20 min, 4°C at 6,000 × g) of the batch culture. Proteins in the filtrate were precipitated over several hours at 4°C with ammonium sulfate to a final concentration of 80%, and the precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 40 min. Protein pellets were obtained upon centrifugation as previously described. Pellets were resuspended in 200 ml of buffer A and dialyzed over 2 days (4°C), with changes, against 40 volumes of the same buffer. All column chromatography steps were performed at 4°C, except for fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) separations that were done at room temperature. The dialyzed fractions were applied to a DE52 (Whatman) column (2.5 by 30 cm, 150 ml) equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 3 column volumes of buffer A at 1 ml/min. A gradient from 0 to 1 M NaCl in buffer A was applied over a total volume of 700 ml. Peak activity that eluted was pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration to 32 ml by using a 10K membrane (Filtron). The concentrated sample was divided into three equal fractions that were separately loaded onto a Superdex 75 HR 10/30 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with gel filtration buffer (50 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.02% sodium azide [pH 7.8]) at 1 ml/min. Peak activities of all runs were combined and concentrated to 22 ml. Ammonium sulfate was added to the fraction in order to give a final salt concentration of 1 M. This sample was then applied to a phenyl-Sepharose HP column (1.5 by 9 cm, 15 ml) equilibrated with 200 mM potassium phosphate–1 M ammonium sulfate (pH 7.5) at 0.5 ml/min. The column was washed with high-salt buffer (120 ml) until an A280 baseline was reached and then was subjected to a 250-ml gradient of 1.0 to 0.0 M ammonium sulfate utilizing 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5). Active fractions were pooled and dialyzed against 20 volumes of buffer A over a 24-h period. The dialyzed sample was concentrated to 37 ml and then applied to a Mono Q HR 10/10 fast protein liquid chromatography column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) that was equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with equilibration buffer until the baseline stabilized. A linear gradient (0 to 500 mM NaCl in buffer A) over 100 ml was applied, and peak enzyme activity was eluted between 200 and 250 mM NaCl. This activity was pooled, dialyzed against 10 volumes of buffer B (25 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2 [pH 7.4]), and applied to a Cibacron blue Sepharose CL-6B column (1 ml) equilibrated with buffer B. Activity flowed through the matrix and was collected while bound, and nonspecific protein was eluted in high-salt buffer B. Final purification to remove additional contaminants involved the use of a Gly-Pro Sepharose affinity column (1 ml). Enzyme obtained from the previous step was loaded onto the column that was previously equilibrated with buffer B. It was then washed with 10 column volumes of this buffer, and a linear gradient (0 to 1 M NaCl in buffer B) over 30 ml was applied. Peak activity was eluted between 150 to 200 mM NaCl and was concentrated to 2.5 ml using a 10K Microsep.

Protein determination

Protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid reagent kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Electrophoresis and autoradiography

Enzyme purity was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a 10% acrylamide gel and the Tris-HCl/Tricine buffer system, according to the method of Schägger and von Jagow (49). Nondenaturing gel electrophoresis (48) in a 4 to 20% gradient gel and gel filtration were used to obtain the molecular weight of the native protein. To confirm the identity of Sg-xPDPP as a serine protease, 5 μg of pure enzyme was incubated with 500 nCi of [1,3-3H]DFP for 30 min at 25°C in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5. Cold DFP (10 mM final concentration) was used to quench the reaction and labeled protein was run on SDS-PAGE, followed by fixing in 2,5-diphenyloxazole, drying of the gel, and exposure to X-ray film (XAR; Eastman Kodak) over a 96-h period. For amino-terminal sequence analysis, Sg-xPDPP was resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by electroblotting to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using 10 mM 3-(cyclohexylamino) propanesulfonic acid–10% methanol, pH 11 (30). The blot was air dried and the band was submitted for sequencing.

Enzyme kinetics and specificity.

Kinetic values were measured using H-Gly-Pro-pNa at various concentrations ranging from 20 μM to 10 mM, with a fixed enzyme concentration at 2 nM, in 100 mM Tris (pH 7.8) at 37°C. Vmax and Km values were obtained through hyperbolic regression analysis (shareware from J. S. Easterby, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom). Specificity studies utilized Sg-xPDPP incubated with 5 μg of peptide in a 1:1,000 molar ratio. Reactions occurred in 100-μl volumes with 100 mM Tris (pH 7.8) at 37°C for 2 h. Digestions were terminated by acidification with 10 μl of 10 M HCl followed by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 5 min). The entire supernatant was applied to reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an LC-18 column (25 by 4.6 mm, 5 μm) (Supelco) equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoracetic acid in HPLC-grade water and developed with an acetonitrile gradient (0 to 80% in 0.08% trifluoracetic acid over 50 min). Peaks were manually collected and analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry

Peptides and native Sg-xPDPP were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)–time of flight on a Hewlett-Packard G2030A mass spectrometer. The instrument was operated at an accelerating voltage of 28 kV, an extractor voltage of 7 kV, and a pressure of 9.33 × 10−5 Pa. Samples were dissolved in sinapic acid and ionized from the probe tip using a nitrogen laser source. Calibration was performed using mixtures of peptides and proteins of known molecular masses.

N-terminal and internal sequencing

Proteins and peptides were sequenced by Edman degradation in a model Procise-cLC sequencer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) operated using the manufacturer's protocol. For internal sequencing, proteins were in-gel digested with trypsin (sequence grade; Promega) and the peptides were extracted (46), with their masses being determined by reflectron MALDI-time of flight mass spectrometry using a Bruker Daltonics ProFlex instrument (42). Selected peptides were sequenced by Edman degradation.

Cloning of Sg-xPDPP gene.

DNA from S. gordonii was purified using the Purgene DNA isolation kit (Gentra, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The N-terminal fragment of the xPDPP gene was obtained using a PCR approach, and degenerate primers were designed for the N-terminal (MRYNQY) and internal (NVIDWL) peptides. Two putative N-terminal primers and one internal primer (all containing BamHI sites [underlined]) were synthesized (nt-1-dpp, 5′-CGCGGATCCATGCGNTAYAAYCARTA-3′; nt-2-dpp, 5′-CGCGGATCCATGAGRTAYAAYCARTA-3′; and int-1-dpp, 5′-CGCGGATTCARCCARTCDATNACRTT-3′, respectively). PCR was performed using Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.), 1 μg of S. gordonii DNA, and 500 ng of the primers (94°C for 1 min, 65°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, 32 cycles). A single 965-bp-long PCR product was obtained, gel purified, digested with BamHI, subcloned into the BamHI site of pUC19, and sequenced. The obtained sequence was used to search the unfinished S. gordonii database, available at The Institute of Genomic Research (TIGR) website (ftp://ftp.tigr.org/pub/data/s_gordonii/). Several overlapping contigs were found, and this approach resulted in the identification of a 2,280-bp-long open reading frame (ORF) carrying the Sg-xPDPP gene. Subsequently, two PCR primers encoding the N and C termini of DPPIV were synthesized (5′-AGTGGATCCATGCGTTACAACCAGTATAG-3′ and 5′-TTTGGATCCTCAAGATTTCTTGTGAGGC-3′) and used in the PCR to obtain the full-length DNA fragment encoding DPPIV. The 2,298-bp-long PCR product was gel purified, digested with BamHI, subcloned into the BamHI site of pUC19, and sequenced on both strands.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence obtained for the Sg-xPDPP gene was deposited in GenBank under accession number AY032733.

RESULTS

Enzyme purification.

Earlier growth experiments indicated the presence of an extracellular Gly-Pro-pNa activity in culture media. Detection of this amidolytic activity in cell-free filtrate was dependent upon growth maintained in a pH range of 6 to 7.5 (unpublished results). In this report, maximum activity was achieved using a 14.5-liter batch culture held at pH 7.5 by addition of base and harvested during early stationary growth. An 80% ammonium sulfate precipitation concentrated extracellular proteins to a workable volume despite the large decrease in enzymatic yield. The subsequent chromatographic steps (DE52 anion-exchange, Superdex 75 gel filtration, and phenyl-Sepharose hydrophobic chromatography) successfully removed high- and low-molecular-weight contaminants, medium pigments, and peptides and amino acids away from the Gly-Pro-pNa activity with a minimal drop in yield. The Mono Q step increased specific activity by 16-fold, although the yield was reduced 50%. CB Sepharose chromatography served as a negative step, enabling activity to flow through the matrix while higher-affinity proteins and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (40) remained bound. The final step, utilizing Gly-Pro Sepharose, resulted in a single, sharp peak of purified protein. Concentrated fractions corresponded to high specific activity, a greater than 6,000-fold purification, and 1% yield from the starting batch culture (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Purification of Sg-xPDPP

| Step | Volume (ml) | Total activity (U)a | Total protein (mg) | Sp act (U/mg) | Purification (fold) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture filtration | 14,500 | 134,117 | 58,000 | 2.3 | 1 | 100 |

| Ammonium sulfate precipitation | 320 | 47,663 | 9,504 | 5.0 | 2 | 36 |

| DE52 anion exchange | 32 | 41,717 | 3,290 | 12.7 | 6 | 31 |

| Superdex 75 gel filtration | 22 | 38,063 | 2,168 | 17.6 | 8 | 28 |

| Phenyl-Sepharose chromatography | 37 | 35,708 | 1,125 | 31.7 | 14 | 27 |

| Mono Q, FPLC | 10 | 17,063 | 35 | 487.5 | 211 | 13 |

| CB Sepharose, FPLC | 15 | 4,180 | 7 | 593.0 | 258 | 4 |

| Gly-Pro Sepharose, FPLC | 3 | 1,370 | 0.97 | 14,153 | 6,153 | 1 |

Based on enzymatic activity using H-Gly-Pro-pNa, where 1 U is 1 μmol of pNa released per s.

Physical properties.

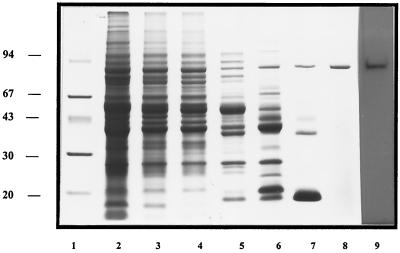

SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified enzyme (Fig. 1) showed a single protein band, as judged by both Coomassie and silver staining (the latter is not shown), with an approximate mass of 85 kDa. Analysis of the protein by MALDI revealed a laser intensity peak that corresponded to a mass of 86,977.6 Da. Protein analyzed on a 4 to 20% native gradient gel and Superdex 200 gel filtration indicated a molecular mass between 150 and 200 kDa, providing evidence for homodimer formation in the native state. This was ablated by heat treatment, SDS denaturation, and MALDI analysis. This suggested that the dimer was stabilized by weak ionic-electrostatic conditions. Isoelectric focusing (data not shown) produced a pI of 4.9 for the native protein. The Gly-Pro-pNa activity was optimum at pH 8.0, with activity detected over a broad phosphate buffer range of 5.0 to 10.0. The optimum temperature for Gly-Pro-pNa hydrolysis was determined to be between 45 and 50°C. The enzyme in its pure form was unstable over a 15-h period at 37 and 25°C (complete loss of activity) and at 4°C (75% loss of activity), while storage at −20°C over several months exhibited minimal activity loss.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of fractions from the purification of Sg-x-PDPP and the autoradiography of the purified peptidase. Lane 1, 15 μg of molecular mass markers (phosphorylase B, 94 kDa; bovine serum albumin, 67 kDa; ovalbumin, 43 kDa; carbonic anhydrase, 30 kDa; soybean trypsin inhibitor, 20 kDa). The following lanes contained boiled, reduced samples: lane 2, 140 μg of 80% ammonium sulfate precipitate; lane 3, 102 μg of eluted peak from DE52 anion exchange; lane 4, 98 μg of peak from Superdex 75 gel filtration wash; lane 5, 55 μg of eluted peak from phenyl Sepharose; lane 6, 39 μg of eluted peak from Mono Q anion exchange; lane 7, 15 μg of CB Sepharose flow-through; lane 8, 6 μg of purified Sg-xPDPP from Gly-Pro Sepharose; lane 9, autoradiograph of [3H]DFP-labeled enzyme exposed for 96 h to X-ray film.

Enzyme specificity

Of the 14 chromogenic endo- and aminopeptidase substrates tested on purified enzyme (Table 2), only three (H-Gly-Pro-pNa, H-Ala-Pro-pNa, and H-Arg-Pro-pNa) were rapidly hydrolyzed. Weaker activity (<10%) was detected against H-Ala-Ala-pNa. A maximum rate of hydrolysis occurred against H-Gly-Pro-pNa, and Michaelis-Menten kinetics were measured using this substrate. A Vm of 15.2 μmol min−1 and a Km of 378 μM were observed with 2 nM of enzyme.

TABLE 2.

Relative amidolytic activitya of Sg-xPDPP against various substrates

| Substrate | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|

| H-Gly-Pro-pNa | 100 |

| H-Ala-Pro-pNa | 81 |

| H-Arg-Pro-pNa | 63 |

| H-Ala-Ala-pNa | 8 |

| H-Gly-Arg-pNa | 0 |

| H-Ala-Phe-pNa | 0 |

| H-Arg-pNa | 0 |

| H-Lys-pNa | 0 |

| H-Ala-pNa | 0 |

| H-Gly-pNa | 0 |

| L-Pro-pNa | 0 |

| Suc-Gly-Pro-pNa | 0 |

| Z-Ala-Pro-pNa | 0 |

| Sar-Pro-Arg-pNa | 0 |

Activity against H-Gly-Pro-pNa hydolysis taken as 100.

To obtain further information on cleavage specificity, various peptides were tested as substrates for Sg-xPDPP (Table 3). Proteolysis was confirmed on peptides between 4 to 17 residues, with a proline residue in the P1 position. A major impediment for cleavage was the presence of Pro in P1′. There were no additional restrictions for amino acids present in the P2 and P1′ sites. The general formula for proteolysis was deduced as NH2-Xaa-Pro(Ala)-↓-Yaa-(Xaa)n, where Yaa could represent any residue except Pro, Xaa could represent any amino acid, and n represents nonquantified Xaa residues C terminal of the Yaa residue. The combined data for synthetic and peptide substrates fit a profile that was consistent with previous data for gram-positive bacterial x-prolyl DPPs (11, 20, 21, 28, 33, 34, 36) and gram-negative DPPIV families (2, 56). Extended-time incubation with peptides failed to yield additional peptide fragments, indicating the absence of endopeptidase activity or contaminating aminopeptidases. Proteolysis of CC chemokines (RANTES and MIP-1β), which presented an unblocked x-prolyl N terminus, was not observed under identical conditions as peptide substrates. The inability of Sg-xPDPP to catalyze endospecific proteolysis was tested on whole protein substrates (azocasein, gelatin, collagen type IV, and fibrinogen). Internal digestion was not observed after standard incubations and SDS-PAGE analysis (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Cleavage specificity of Sg-xPDPP on peptide substrates

| Substrate | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Sexual agglutination peptide | Arg-Gly-Pro-Phe-Pro-Ile |

| Protein kinase C fragment | Arg-Phe-Ala-Arg-Lys-Gly-Ala-Leu-Arg-Gln-Lys-Asn-Val |

| Substance P | Arg-Pro-↓-Lys-Pro-↓-Gln-Gly-Leu-Met |

| Bradykinin | Arg-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe-Ser-Pro-Phe-Arg |

| des-Arg1 bradykinin | Pro-Pro-↓-Gly-Phe-Ser-Pro-Phe-Arg |

| Dipeptide A | Arg-Pro |

| Sleep-inducing peptide | Trp-Ala-↓-Gly-Gly-Asp-Ala-Ser-Gly-Glu |

| Fibrin polymerization inhibitor | Gly-Pro-↓-Arg-Pro |

| Fibrin inhibitory peptide | Gly-Pro-↓-Arg-Pro-Pro-Glu-Arg-His-Gln-Ser |

| Protein kinase C peptide | Gly-Pro-↓-Lys-Thr-Pro-Gln-Lys-Thr-Ala-Asn-Thr-Ile-Ser-Lys-Phe-Asp-Cys |

| Kallidin | Lys-Arg-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe-Ser-Pro-Phe-Arg |

| Lymphocyte-activating pentapeptide | Leu-Pro-Pro-Ser-Arg |

↓, Cleavage site.

Inhibition and activation studies.

Autoradiography of purified Sg-xPDPP radiolabeled with [1,3-3H]DFP (Fig. 1, lane 9) positively identified the protease as a member of the serine class. Further studies with class-specific inhibitors (Table 4) supported this assignment. Sensitivity to serine protease inhibitors (Pefabloc, PMSF, and 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin) was observed, while cysteine class (iodoacetamide and E64) and metallo class (EDTA and 1,10-orthophenanthroline) members had little or no effect on activity. Compounds specific for aminopeptidase B and leucine aminopeptidase (bestatin) and aminopeptidase P (apstatin) were not inhibitory. However, Sg-xPDPP was highly sensitive to the DPPIV/CD26-specific inhibitors, H-Glu-pyrollidide and diprotin A (Ile-Pro-Ile), as evidenced by 50% inhibitory concentration values of approximately 100 μM. Human plasma inhibitors, α-1-proteinase inhibitor and α-2-macroglobulin, had no effect on enzymatic activity. Sg-xPDPP activity was also inhibited by the heavy metal ions Zn2+ and Co2+ at 0.5 and 5 mM, respectively. Complete inactivation occurred in the presence of 1% SDS detergent. Activity was unaffected by reducing agents and urea. Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro-amide served as a competitive inhibitor, while the dipeptide, Gly-Pro, provided no inhibition. In contrast, Gly-Gly moderately stimulated pNa hydrolysis.

TABLE 4.

Inhibition profile of Sg-xPDPP

| Inhibitor | Concn or percent | % of residual activity |

|---|---|---|

| DFP | 10 mM | 0 |

| Pefabloc | 1 mM | 55 |

| PMSF | 5 mM | 51 |

| 3,4-Dichloroisocoumarin | 5 mM | 0 |

| TLCK | 10 mM | 96 |

| TPCK | 10 mM | 100 |

| Aprotinin | 600 μM | 97 |

| Bestatin | 250 μM | 99 |

| Apstatin | 1 mM | 100 |

| H-Glu-pyrollidide | 100 μM | 56 |

| 1 mM | 11 | |

| Diprotin | 100 μM | 47 |

| 1 mM | 10 | |

| E-64 | 1 mM | 85 |

| Iodoacetamide | 1 mM | 100 |

| EDTA | 1 mM | 106 |

| 1,10-Orthophenanthroline | 10 mM | 99 |

| l-Cysteine | 5 mM | 100 |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 5 mM | 87 |

| Gly-Gly | 5 mM | 117 |

| Gly-Pro | 10 mM | 105 |

| Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro-amide | 4 mM | 62 |

| Co2+ | 500 μM | 57 |

| Zn2+ | 5 mM | 42 |

| Ca2+ | 5 mM | 103 |

| SDS | 1% | 7 |

| Urea | 2 mM | 100 |

Sg-xPDPP sequence analysis and gene structure.

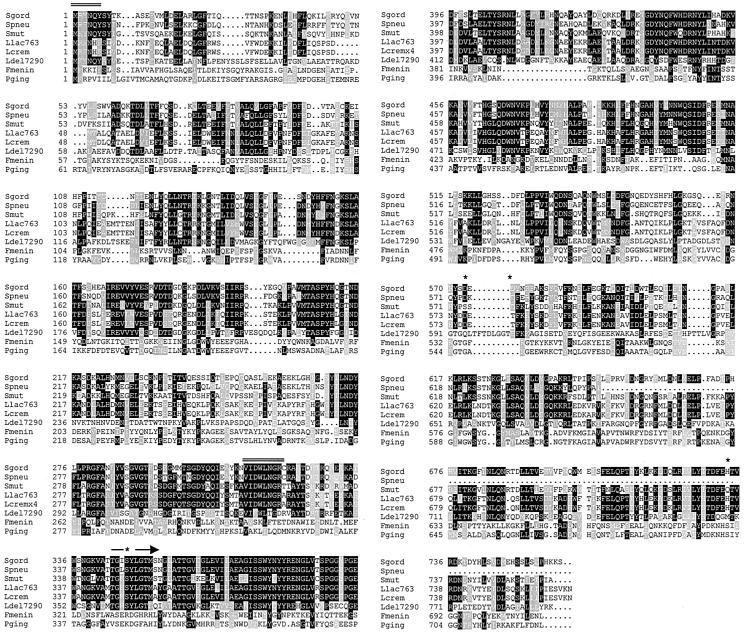

N-terminal and internal sequences facilitated the construction of degenerate primers. PCR against an FSS2 library resulted in the isolation of a 960-bp fragment that represented the N terminus of the protein. This product was used to search the genomic clone of a relatively uncharacterized S. gordonii strain in the Unfinished Microbial Genomes database of TIGR. An ORF of 2,280 bp was identified and was found to correspond to Sg-xPDPP on the basis of the conservation of protein-derived peptides. Primers were designed from the electronic sequence, and a PCR approach was used to obtain a full-length DNA fragment encoding DPPIV. A 759-amino-acid polypeptide with a theoretical molecular mass of 87,115 Da and a calculated pI of 5.6 was encoded by this ORF. This is in agreement with the observed experimental mass, while the native-state dimer is produced by association of two identical monomers. There is no evidence for posttranslational modifications of the gene product. The homology search (Fig. 2) performed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information TBLASTN tool against EMBL, DDBJ, GenBank, and PDB databases indicated that Sg-xPDPP is a new member of the x-prolyl DPP S15 family grouped in the SC clan of serine peptidases (5). This family had previously consisted of peptidases that derive from lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus spp. and Lactococcus spp.), known as PepX (51). Sg-xPDPP shares the closest homology with putative genes uncovered in Streptococcus pneumoniae (72% identity) and Streptococcus mutans (57% identity) while maintaining only 48% and 34% identity with Lactococcus and Lactobacillus, respectively. Sg-xPDPP displays evolutionary divergence from bacterial members of the DPPIV (S9) family, Flavobacterium meningosepticum (10% identity), and Porphyromonas gingivalis (11% identity), although it shares functional similarities. The active-site serine has been identified in the PepX gene of L. lactis as Ser348 inside the motif GKSYLG (6). Thus, by analogy Ser347 of Sg-xPDPP is likely to be the active-site residue. Streptococcal xPDPPs and PepX have nearly identical residues flanking the catalytic motif, except for a hydrophobic amino acid replacing a charged Lys in the second position. Based upon homology to SC peptidases with Ser-Asp-His active-site nomenclature, Asp574 and Asp576 and His733 of Sg-xPDPP are likely candidates for the catalytic triad (44). A computer-assisted search for protein localization predicted neither signal sequence sites nor transmembrane regions in the protein (37). Although lacking an export signal and predicted to be cytoplasmic, activity detected on the cell surface and within supernatant revealed 20% of activity to be extracellular.

FIG. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of Sg-xPDPP, putative streptococcal PepX genes, and other bacterial homologues. Sequences of Sg-xPDPP (Sgord) deduced from FSS2 genome, putative x-PDPPs from gene products of S. pneumoniae (Spneu) and S. mutans (Smut), cloned x-PDPP from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis 763 (Llac763), Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris (Lcrem), Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis (Ldel17290), and cloned DPPIV from Flavobacterium meningosepticum (Fmenin) and Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pging) were aligned using the ClustalW multiple sequence alignment tool according to homology modeling (grey boxes indicate similarity and black boxes indicate identity). The putative catalytic residues (serine, aspartic acid, and histidine) are denoted with asterisks. The arrow marks a consensus motif flanking the active-site serine in members of the x-PDPP family (PepX). Double lines represent N-terminal and internal fragments used to generate a 965-bp PCR product.

Southern blot analysis revealed Sg-xPDPP to be a single-copy gene (data not shown). The 2.3-kb ORF was examined in the electronic database for the presence of promoter elements and additional genes. Three ORFs were revealed and designated ORF 1 (760 codons), ORF 2 (277 codons), and ORF 3 (236 codons). Sg-xPDPP is coded by ORF 1, while ORFs 2 and 3 are oriented upstream on complementary strands in reverse directions. A ribosome binding site was identified 5 bp upstream of the start codon. The putative transcription start site was found 33 bp from the start Met as well as the TATA (−10 box) and −35 region promoters. ORF 2 is 118 bp upstream from the start codon of ORF 1. The protein specified by ORF 2 has close to 70% identity with a hypothetical 30.9-kDa protein found in the PepX 5′ region of L. lactis (31, 38) and shares significant homology to the glycerol uptake facilitator (Glpf) from S. pneumoniae (47). ORF 3 is 1,091 bp upstream from ORF 1 and encodes a 236-amino-acid protein with no significant homology to proteins in the aforementioned databases.

DISCUSSION

This report describes the purification, characterization, cloning, and sequence analysis of an extracellular x-prolyl DPP from S. gordonii FSS2. This activity has been described in studies concerning tripeptide degradation systems of S. sanguinis and S. mutans (8) and collagen degradation by S. gordonii Challis in the IE model (19). Our work presents the first biochemical and genetic studies of purified enzyme. Filtrate obtained from a pH-controlled culture of S. gordonii FSS2 enabled the purification of Sg-xPDPP by more than 6,000-fold. The preparation was determined to be homogenous and consisted of two identical, noncovalently attached monomers in the native state. Inactivation studies revealed a serine class catalytic mechanism in which DPPIV family inhibitors appear to be the most effective. Specificity studies were conducted using paranitroanalides and peptides smaller than 20 residues. Limited proteolysis was observed upon incubation with either substrate. The requirement of Pro or Ala in the penultimate position and prohibition of Pro in the P1′ site define the specific nature of this peptidase.

Collectively, the biochemical data are consistent with studies on DPPIV-like peptidases from S. mitis (11), Streptococcus thermophilus (33), and Streptococcus salivarius (35). Comparison of the Sg-xPDPP protein sequence with that of cloned x-prolyl DPPs reveals significant homology (41% average identity) with PepX gene products of lactic acid bacteria (31, 34). Putative genes for x-prolyl DPP were identified in unfinished microbial genomes for S. mutans and S. pneumoniae and maintained 57% and 72% identity to Sg-xPDPP, respectively. The consensus sequence, GXSYLG, is present at the active site of PepX and streptococcal members. Phylogenetically related viridans members, S. pneumoniae and S. gordonii, maintain hydrophobic residues at the second position which are contrasts to basic residues conserved in other species. The PepX gene and streptococcal analogue appear to have diverged from a common ancestor that bears little sequence homology to the DPPIV/CD26 family of eukaryotic and gram-negative peptidases. Sg-xPDPP closely resembles members of the S15 family (EC 3.4.14.11), yet our discovery of streptococcal members with remarkable evolutionary conservation may warrant a change in nomenclature.

The localization of peptidases outside of the cell is considered to be a necessary mechanism for the degradation and intracellular transport of endopeptidase-liberated peptides. Currently, all reported x-prolyl DPP members from gram-positive bacteria have been associated either with cytoplasmic membrane or with whole-cell extracts (24). Sg-xPDPP represents the first peptidase from this group isolated from an extracellular source. Sequence analysis did not reveal an N-terminal signal sequence, LPXTG motif (39), or posttranslational modifications that could account for translocation from the cytoplasm. We found the gene for Sg-xPDPP to be single copy, ruling out the possibility of an altered form of the peptidase. Previous reports have suggested that such enigmatic transport is the result of specific leakage of cytoplasmic aminopeptidase from cells (51) or the shedding of protease-peptidoglycan complexes as a consequence of cell wall turnover (19). In S. gordonii G9B, extracellular protein profiles were altered by changes in pH, growth medium composition, and rate of growth (23). Additionally, the secretion of two cytoplasmic proteins from S. gordonii, a GAPDH (40) and collagenase (19), was observed upon growth at a constant, neutral pH. In studies conducted by Harty et al., specific activities of extracellular proteases (thrombin-like, Hageman factor, and collagenase) from FSS2 increased severalfold upon a shift in pH from 6.5 to 7.5 (13).These data are consistent with maximum detection of our Sg-xPDPP activity at a controlled pH of 7.5. Furthermore, the peak of Gly-Pro-pNa activity occurred during early stationary phase, when excess glucose had been exhausted. The alkaline environment of the buffered vegetation that contacts the bloodstream may be more suitable for enzyme release from the cell. An extracellular peptidase would therefore better serve the nutritional requirements of the bacteria in fibrin and/or extracellular matrix surroundings versus the carbohydrate-rich oral environment.

The biological significance of Sg-xPDPP outside of the cell would serve a threefold purpose: (i) the production of proline-containing dipeptides that could subsequently be transported into the cell, (ii) a synergy with other secreted proteases that would permit the degradation of host proteins, and (iii) the modification of bioactive peptides at the endothelium. L. lactis and other lactic acid bacteria are unable to import free Pro, which must be transported in a peptide-bound configuration (24). A tripeptide transport system was identified in S. sanguinis that permitted the assimilation of free amino acids by membrane-bound and intracellular proteolysis. It was further concluded that x-prolyl dipeptides were insufficient for transport (8). This is counterintuitive to the action of Sg-xPDPP that results in high concentrations of extracellular dipeptides. In S. gordonii, uptake could be driven by an inwardly directed chemical gradient maintained by fluctuating levels of extracellular and cell-associated products of peptide hydrolysis. The limited cleavage specificity of Sg-xPDPP prohibits the independent proteolysis of constituents within and surrounding the thrombotic vegetation.

Neither type IV collagen nor fibrin(ogen) was a suitable substrate for the enzyme. This contrasts with the finding of Juarez and Stinson of a Gly-Pro-pNa activity capable of endopeptidase attack on native collagen (19). Culture supernatant of FSS2 yielded several endopeptidase activities capable of degrading denatured collagen, fibrinogen, and azocasein. Two additional extracellular aminopeptidases, an Arg-specific aminopeptidase and PepV tripeptidase (J. M. Goldstein et al., unpublished data), would participate in the acquisition of small peptides from the protein meshwork surrounding the bacteria.

Although Sg-xPDPP achieved proteolysis of all suitable peptides tested, there is an apparent restriction of substrate size. Three cytokines tested (RANTES, MIP-1β, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor), presenting unblocked x-prolyl motifs, failed to undergo cleavage upon extended incubations and increased enzyme/substrate molar ratios. This is in contrast to the activities of DPPIV/CD26 members which facilitate the N-terminal proteolysis of these larger substrates despite their high catalytic similarity to the PepX members (16, 43). Sequence divergence in specificity pockets and the presence of adhesion domains, absent in gram-positive peptidases, may contribute to this phenomenon. The removal of two dipeptides from substance P was observed, and this heptapeptide product has been found to display biological activity more potent than that of the intact peptide (55). Additionally, the concerted action of an extracellular Arg aminopeptidase and Sg-xPDPP produces a truncated form of bradykinin that has lost essential residues for receptor activation (3). The combined effect of these modifications may result in local changes in vascular permeability and smooth muscle contraction at the infected endothelium. The truncation of fibrin inhibitory peptides by Sg-xPDPP could have consequences on thrombus formation and the overall growth of the vegetation. The soluble tetrapeptide (GPRP), representing the N terminus of the fibrin α-chain, blocks the polymerization of fibrin monomers, leading to blocked polymerization, decreased clotting, and increased clotting times (27). The minimum structural unit (GPR) is required for inhibitory action. Sg-xPDPP may inactivate circulating inhibitor in the growing thrombus and alter the balance between polymerization and fibrinolysis in favor of a growing vegetation. Future studies will focus on the expression and knockout of Sg-xPDPP in order to evaluate its relative contributions to streptococcal virulence and survival at the site of infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DE-097621.

We thank TIGR for utilization of the unfinished database.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson C, Sund M L, Linder L. Peptide utilization by oral streptococci. Infect Immun. 1984;43:555–560. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.555-560.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banbula A, Bugno M, Goldstein J, Yen J, Nelson D, Travis J, Potempa J. Emerging family of proline-specific peptidases of Porphyromonas gingivalis: purification and characterization of serine dipeptidyl peptidase, a structural and functional homologue of mammalian prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1176–1182. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1176-1182.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhoola K D, Figueroa C D, Worthy K. Bioregulation of kinins: kallikreins, kininogens, and kininases. Pharmacol Rev. 1992;44:1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burne R A. Oral streptococci … products of their environment. J Dent Res. 1998;77:445–452. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770030301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chich J F. X-Pro-dipeptidyl peptidase. In: Barrett A J, Rawlings N D, Woessner J F, editors. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 403–405. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chich J F, Chapot-Chartier M P, Ribadeau-Dumas B, Gripon J C. Identification of the active site serine of the X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Lactococcus lactis. FEBS Lett. 1992;314:139–142. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80960-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowman R A, Baron S S. Influence of hydrophobicity on oligopeptide utilization by oral streptococci. J Dent Res. 1990;69:1847–1851. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690121101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowman R A, Baron S S. Pathway for uptake and degradation of X-prolyl tripeptides in Streptococcus mutans VA-29R and Streptococcus sanguinis ATCC 10556. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1477–1484. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760081001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas C W, Heath J, Hampton K K, Preston F E. Identity of viridans streptococci isolated from cases of infective endocarditis. J Med Microbiol. 1993;39:179–182. doi: 10.1099/00222615-39-3-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drangsholt M T. A new causal model of dental diseases associated with endocarditis. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:184–196. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukasawa K M, Harada M. Purification and properties of dipeptidyl peptidase IV from Streptococcus mitis ATCC 9811. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1981;210:230–237. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong K, Ouyang T, Herzberg M C. A streptococcal adhesion system for salivary pellicle and platelets. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5388–5392. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5388-5392.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harty D W, Mayo J A, Cook S L, Jacques N A. Environmental regulation of glycosidase and peptidase production by Streptococcus gordonii FSS2. Microbiology. 2000;146:1923–1931. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herzberg M C. Platelet-streptococcal interactions in endocarditis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1996;7:222–236. doi: 10.1177/10454411960070030201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzberg M C, Meyer M W. Effects of oral flora on platelets: possible consequences in cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1138–1142. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann T, Faust J, Neubert K, Ansorge S. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD 26) and aminopeptidase N (CD 13) catalyzed hydrolysis of cytokines and peptides with N-terminal cytokine sequences. FEBS Lett. 1993;336:61–64. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Homer K A, Whiley R A, Beighton D. Proteolytic activity of oral streptococci. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;55:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90005-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkinson H F, Baker R A, Tannock G W. A binding-lipoprotein-dependent oligopeptide transport system in Streptococcus gordonii essential for uptake of hexa- and heptapeptides. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:68–77. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.68-77.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juarez Z E, Stinson M W. An extracellular protease of Streptococcus gordonii hydrolyzes type IV collagen and collagen analogues. Infect Immun. 1999;67:271–278. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.271-278.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalid N M, Marth E H. Purification and partial characterization of a prolyl-dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Lactococcus helveticus CNRZ 32. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:381–388. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.2.381-388.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiefer-Partsch B, Bockelmann W, Geis A, Teuber M. Purification and characterization of an X-prolyl-dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from the cell wall proteolytic system of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;31:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kili A O, Herzberg M C, Meyer M W, Zhao X, Tao L. Streptococcal reporter gene-fusion vector for identification of in vivo expressed genes. Plasmid. 1999;42:67–72. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knox K W, Hardy L N, Markevics L J, Evans J D, Wicken A J. Comparative studies on the effect of growth conditions on adhesion, hydrophobicity, and extracellular protein profile of Streptococcus sanguinis G9B. Infect Immun. 1985;50:545–554. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.545-554.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kok J. Genetics of the proteolytic system of lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;7:15–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konings W N, Poolman B, Driessen A J. Bioenergetics and solute transport in lactococci. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1989;16:419–476. doi: 10.3109/10408418909104474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korzenioswki O M, Kaye D. Infective endocarditis. In: Braunwald E, editor. Heart disease. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1992. pp. 1078–1105. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laudano A P, Doolittle R F. Studies on synthetic peptides that bind to fibrinogen and prevent fibrin polymerization. Structural requirements, number of binding sites, and species differences. Biochemistry. 1980;19:1013–1019. doi: 10.1021/bi00546a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lloyd R J, Pritchard G G. Characterization of X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manning J E, Hume E B, Hunter N, Knox K W. An appraisal of the virulence factors associated with streptococcal endocarditis. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:110–114. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-2-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsudaira P. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayo B, Kok J, Venema K, Bockelmann W, Teuber M, Reinke H, Venema G. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:38–44. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.38-44.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayo J A, Zhu H, Harty D W, Knox K W. Modulation of glycosidase and protease activities by chemostat growth conditions in an endocarditis strain of Streptococcus sanguinis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1995;10:342–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1995.tb00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer J, Jordi R. Purification and characterization of X-prolyl-dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase from Lactobacillus lactis and from Streptococcus thermophilus. J Dairy Sci. 1987;70:738–745. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)80068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer-Barton E C, Klein J R, Imam M, Plapp R. Cloning and sequence analysis of the X-prolyl-dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase gene (pepX) from Lactobacillus delbruckii subsp. lactis DSM7290. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;40:82–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00170433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mineyama R, Saito K. Purification and characterization of dipeptidyl peptidase IV from Streptococcus salivarius HHT. Microbios. 1991;67:37–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyakawa H, Kobayashi S, Shimamura S, Tomita M. Purification and characterization of an X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus LBU-147. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:2375–2381. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. Expert system for predicting protein localization sites in gram-negative bacteria. Proteins. 1991;11:95–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nardi M, Chopin M C, Chopin A, Cals M M, Gripon J C. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of an X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCDO 763. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:45–50. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.45-50.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navarre W W, Schneewind O. Surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:174–229. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.174-229.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson D, Goldstein J M, Boatright K, Harty D W, Cook S L, Hickman P J, Potempa J, Travis J, Mayo J A. pH-regulated secretion of a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Streptococcus gordonii FSS2: purification, characterization, and cloning of the gene encoding this enzyme. J Dent Res. 2001;80:371–377. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800011301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nolte W A. Defense mechanisms of the mouth. In: Nolte W A, editor. Oral microbiology. C. V. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Company; 1982. pp. 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pohl J, Hubalek F, Byrnes M E, Nielsen K R, Woods A, Pennington M W. Assignment of three disulfide bonds in ShK toxin: a potent potassium channel inhibitor from sea anenome Stichodactyla helianthus. Pept Sci. 1995;1:291–297. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Proost P, De Meester I, Schols D, Struyf S, Lambeir A M, Wuyts A, Opdenakker G, De Clercq E, Scharpe S, Van Damme J. Amino-terminal truncation of chemokines by CD26/dipeptidyl-peptidase IV. Conversion of RANTES into a potent inhibitor of monocyte chemotaxis and HIV-1 infection. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7222–7227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rawlings N D, Polgar L, Barrett A J. A new family of serine-type peptidases related to prolyl oligopeptidase. Biochem J. 1991;279:907–908. doi: 10.1042/bj2790907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogers A H, Pfennig A L, Gully N J, Zilm P S. Factors affecting peptide catabolism by oral streptococci. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1991;6:72–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1991.tb00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenfeld J, Capdevielle J, Guillemot J C, Ferrara P. In-gel digestion of proteins for internal sequence analysis after one- or two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 1992;203:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90061-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saluja S K, Weiser J N. The genetic basis of colony opacity in Streptococcus pneumoniae: evidence for the effect of box elements on the frequency of phenotypic variation. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:215–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schägger H. Native electrophoresis for isolation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation protein complexes. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:190–202. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullam P M. Host-pathogen interactions in the development of bacterial endocarditis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1994;7:304–309. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan P S, Poolman B, Konings W N. Proteolytic enzymes of Lactococcus lactis. J Dairy Res. 1993;60:269–286. doi: 10.1017/s0022029900027606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vriesema A J M, Dankert J, Zaat S A J. A shift from oral to blood pH is a stimulus for adaptive gene expression of Streptococcus gordonii CH1 and induces protection against oxidative stress and enhanced bacterial growth by expression of msrA. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1061–1068. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1061-1068.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whiley R A, Beighton D. Current classification of the oral streptococci. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1998;13:195–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willcox M D, Patrikakis M, Knox K W. Degradative enzymes of oral streptococci. Aust Dent J. 1995;40:121–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1995.tb03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yajima H, Kitagawa K. Studies on peptides. XXXIV. Conventional synthesis of the undecapeptide amide corresponding to the entire amino acid sequence of bovine substance P. Chem Pharm Bull. 1973;21:682–683. doi: 10.1248/cpb.21.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoshimoto T, Tsuru D. Proline-specific dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Flavobacterium meningosepticum. J Biochem. 1982;91:1899–1906. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]