Abstract

The formation of attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions on gut enterocytes is central to the pathogenesis of enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) Escherichia coli, enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), and the rodent pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Genes encoding A/E lesion formation map to a chromosomal pathogenicity island termed the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE). Here we show that the LEE-encoded proteins EspA, EspB, Tir, and intimin are the targets of long-lived humoral immune responses in C. rodentium-infected mice. Mice infected with C. rodentium developed robust acquired immunity and were resistant to reinfection with wild-type C. rodentium or a C. rodentium derivative, DBS255(pCVD438), which expressed intimin derived from EPEC strain E2348/69. The receptor-binding domain of intimin polypeptides is located within the carboxy-terminal 280 amino acids (Int280). Mucosal and systemic vaccination regimens using enterotoxin-based adjuvants were employed to elicit immune responses to recombinant Int280α from EPEC strain E2348/69. Mice vaccinated subcutaneously with Int280α, in the absence of adjuvant, were significantly more resistant to oral challenge with DBS255(pCVD438) but not with wild-type C. rodentium. This type-specific immunity could not be overcome by employing an exposed, highly conserved domain of intimin (Int388–667) as a vaccine. These results show that anti-intimin immune responses can modulate the outcome of a C. rodentium infection and support the use of intimin as a component of a type-specific EPEC or EHEC vaccine.

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) are important causes of severe infantile diarrheal disease. EPEC and EHEC colonize the gastrointestinal mucosa and, by subverting intestinal epithelial cell function, produce a characteristic histopathological feature known as the attaching and effacing (A/E) lesion (35). The A/E lesion is characterized by localized destruction (effacement) of brush border microvilli, intimate attachment of the bacterium to the host cell membrane, and the formation of an underlying pedestal-like structure in the host cell. EPEC and EHEC are members of a family of enteric bacterial pathogens which use A/E lesion formation to colonize the host. E. coli cells capable of forming A/E lesions have also been recovered from diseased cattle (8), rabbits (24), pigs (2), and dogs and cats (6). Similarly, the mouse pathogen Citrobacter rodentium causes colitis in mice as a consequence of its ability to colonize murine large intestinal enterocytes via A/E lesion formation (4, 41).

Genes implicated in A/E lesion formation map to a pathogenicity island termed the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) (16). The LEE pathogenicity island, which is present in EPEC, EHEC, and C. rodentium, is regarded as being necessary for bacteria to promote the induction of A/E lesions on epithelial cells. The LEE region encodes a type III secretion system: the secreted proteins EspA, EspB, and EspD among others; an outer membrane adhesin termed intimin; and a translocated intimin receptor, Tir (44).

Studies on intimin in EPEC, EHEC, and C. rodentium have demonstrated its importance in bacterial colonization and virulence (10, 12, 41). The receptor binding domain of intimin molecules are localized to the C-terminal 280 amino acids of intimin (Int280) (14). Furthermore, based on sequence variation within Int280, five distinct intimin subtypes (α, β, γ, δ, and ɛ) have been described (1, 36). Intimin α is specifically expressed by a group of EPEC clone 1 strains. Intimin β is mainly associated with clone 2 EPEC and EHEC strains, C. rodentium and rabbit-specific EPEC, while intimin γ is associated with EHEC O157:H7 (34). Recently, the structure of Int280α complexed with Tir was determined by X-ray crystallography (31). The structure shows that Int280α comprises three separate domains, two immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains and a C-type lectin-like module. Intimin is also the target of host immune responses in infected animals (15) and humans (37, 40), although little is known about the host immune response to other LEE-encoded antigens. Intimin has also been promoted as a potential candidate vaccine antigen based on the ability of antiserum raised against intimin from EHEC O157:H7 to inhibit adherence of this strain to HEp-2 cells (17).

The absence of small animal models to study EPEC or EHEC directly has made the study of host response to infection problematic. In this case, conclusions about EPEC and EHEC need to be drawn from studies of other pathogens that colonize via A/E lesion formation. In this respect, C. rodentium infection of mice offers an advantage because of the wide availability of gene knockout strains and immunological reagents available for this species. While an imperfect model of EPEC and EHEC infection, C. rodentium infection of mice nevertheless represents the best small-animal model in which to study luminal microbial pathogens relying on A/E lesion formation for colonization of the host.

The A/E lesion induced by C. rodentium is ultrastructurally identical to those formed by EHEC and EPEC in animals and human intestinal in vitro organ culture, although the target tissue specificity differs between the last two pathogens (38). In experimentally or naturally infected mice, large numbers of C. rodentium organisms can be recovered from the colon and infection is associated with crypt hyperplasia and mucosal erosion (3, 22, 25). Oral infection of mice with live wild-type C. rodentium or intracolonic inoculation of dead bacteria induces a CD3+ and CD4+ T-cell infiltrate into the colonic lamina propria and a strong T-helper type 1 immune response (21, 22). This response is not observed in mice inoculated with an intimin mutant of C. rodentium but is seen in mice inoculated with C. rodentium complemented with intimin α from EPEC E2348/69 (22).

The aims of this study were to measure immune responses to LEE-encoded antigens in mice infected with C. rodentium and determine whether infected animals develop acquired immunity. Furthermore, this study tested the hypothesis that an intimin-based vaccination regimen may modulate the outcome of a subsequent C. rodentium infection.

The results demonstrate that mice develop acquired immunity to C. rodentium and that parenteral immunization of mice with intimin can significantly limit colonization and disease caused by experimental C. rodentium infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female, specific-pathogen-free C3H/Hej mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Olac (Bichester, United Kingdom). All mice were housed in individual ventilated cages with free access to food and water.

Bacterial strains.

A nalidixic acid-resistant isolate of C. rodentium (formerly C. freundii biotype 4280) was used in these studies. The nalidixic acid-resistant phenotype of this strain facilitates enumeration of the number of viable C. rodentium cells present in colonic tissues of experimentally infected mice. DBS255 is an eae mutant of C. rodentium and is avirulent in mice. Plasmid pCVD438 is a recombinant plasmid containing the eae gene from EPEC strain E2348/69 (intimin α). Thus, DBS255(pCVD438) is a C. rodentium eae mutant complemented with the eae gene from EPEC strain E2348/69 (intimin α). This strain expresses biologically active intimin and is virulent in mice (15).

Immunization and oral infection of mice.

For intranasally (i.n.) immunized mice, animals were lightly anesthetized with gaseous halothane and 30 μl of a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution containing antigen applied to the nares. Mice were i.n. immunized on days 0, 14, and 28 and orally challenged between days 42 and 44. For subcutaneously (s.c.) immunized mice, animals received s.c. injections with 150 μl of antigen mixture in PBS on the left side of the abdomen. As per i.n. immunization, mice were s.c. immunized on days 0, 14, and 28 and orally challenged between days 42 and 44. Bacterial inocula were prepared by culturing bacteria overnight at 37°C in L broth containing nalidixic acid (100 μg/ml) (C. rodentium) or L broth containing nalidixic acid (100 μg/ml) plus chloramphenicol (50 μg/ml) [for DBS255(pCVD438)]. After incubation, bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in an equal volume of PBS. A 1/10 dilution of bacteria in PBS was then prepared and mice were orally inoculated, without anesthetic, using a gavage needle with 200 μl of the bacterial suspension. The viable count of the inoculum was determined by retrospective plating on L agar containing appropriate antibiotics.

Enterotoxins and recombinant proteins.

Recombinant porcine heat-labile toxin (LT) and the mutant derivatives LTK63 and LTR72 were kindly provided by M. Pizza and R. Rappuoli (Chiron Vaccines, Siena, Italy) and were prepared as described previously (32). LT is a potent mucosal immunogen and has well-described systemic and mucosal adjuvant properties (42). LTR72 and LTK63 are derivatives of LT that have reduced (LTR72) or absent (LTK63) ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Nevertheless, LTR72 and LTK63 act as mucosal adjuvants for coadministered antigens (13, 18). Recombinant Int280α, which represents the C-terminal 280 amino acids of intimin (Int660–939) from EPEC strain E2348/69, was purified as described previously (27). Int388–667, which corresponds to two putative Ig-like domains upstream of Int280α, was purified as a polyhistidine-tagged polypeptide as described (5). EspA (28) and Tir-M, the intimin-binding domain of Tir (20), were also purified as polyhistidine-tagged polypeptides. EspB from EPEC strain E2348/69 and Int280β from EPEC strain O114:H2 were expressed as maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusions in E. coli and purified by nickel affinity chromatography as previously described (15, 28). Purified MBP was purchased from Sigma (Poole, United Kingdom). A preparation of soluble proteins from C. rodentium was generated by repeated sonication of a concentrated suspension of bacteria cultured overnight in L broth. Insoluble proteins were removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant removed and stored at −20°C. The concentration of protein solutions was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Measurement of pathogen burden.

At selected time points postinfection, mice were killed by cardiac exsanguination under terminal anesthesia or by cervical dislocation. Spleens, livers, and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) were then aseptically removed. The distal 6 cm of colon was also removed, and this piece of tissue was weighed after removal of fecal pellets. Spleens, livers, lymph nodes, and colons were then homogenized mechanically using a Seward 80 stomacher (Seward Medical, London, England), and the number of viable bacteria in organ homogenates was determined by viable count on medium containing appropriate antibiotics.

Analysis of humoral immune responses.

At selected times postimmunization, 0.2 ml of blood was collected from the tail vein of immunized mice, and sera were collected and stored at −20°C until analyzed. For analysis of antigen-specific antibody responses, wells of microtiter plates (Maxisorb plates; Nunc) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl of a bicarbonate solution (pH 9.6) containing Int280α (2.5 μg/ml), EspA (1.5 μg/ml), EspB (1.5 μg/ml), Tir-M (1 μg/ml), ovalbumin (Ova) (60 μg/ml), MBP (5 μg/ml), Int388–667 (1.5 μg/ml), or C. rodentium whole-cell lysate (20 μg/ml). After washing with PBS-Tween 20, wells were blocked by addition of 1.5% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h. Plates were then washed twice with PBS-Tween 20 before sera from individual mice were added and serially diluted in PBS-Tween 20 containing 0.2% (wt/vol) BSA, and then plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. For the determination of IgA antibody titers, wells were washed with PBS-Tween 20 before addition of 100 μl of an IgA horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Dako, Ely, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) diluted 1/1,000 in PBS-Tween 20 containing 0.2% (wt/vol) BSA for 2 h at 37°C. For the determination of total IgG responses, a 1/1,000 dilution of an HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG polyclonal antibody was applied for 2 h. For the determination of antigen-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibody titers in mouse serum, biotinylated rat monoclonal antibodies against IgG1 and IgG2a (Pharmingen, Hull, United Kingdom), used at concentrations previously shown to give equivalent optical densities when assayed against identical amounts of purified IgG1 or IgG2a, respectively, were used as secondary antibodies for 2 h. After washing with PBS/Tween-20, a 1/1,000 dilution of strepavidin-HRP was added for 2 h. Finally, after washing with PBS-Tween 20, bound antibody was detected by addition of o-phenylenediamine substrate (Sigma) and the A490 was measured. Titers were determined arbritarily as the reciprocal of the serum dilution corresponding to an optical density of 0.3. The minimum detectable titer was 100.

Statistical analysis.

The nonparametric Mann-Whitney t test or Student's t test was employed for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Mice infected with C. rodentium mount immune responses to LEE-encoded antigens.

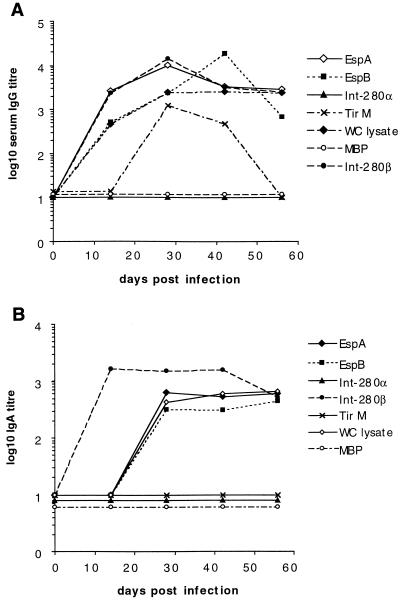

Proteins encoded by genes in the LEE pathogenicity island are necessary for bacteria to attach and induce A/E lesion formation on the surface of epithelial cells (16). Serum antibody responses in mice infected with wild-type C. rodentium were analyzed to determine if LEE-encoded proteins were recognized by the host immune system. Mice infected orally with C. rodentium mounted serum IgG (Fig. 1A) and IgA (Fig. 1B) antibody responses that recognized antigens in a whole-cell lysate of C. rodentium. Infected mice also mounted serum IgG and IgA responses which cross-reacted with EspA and EspB from EPEC 2348/69 (Fig. 1). TirM-specific IgG (Fig. 1A), but not IgA responses (Fig. 1B), were also detected in sera of infected mice. As expected, sera from mice infected with wild-type C. rodentium (which expresses intimin β) did not recognize Int280α from EPEC strain E2348/69 but did cross-react with Int280β from EPEC 0114:H2 (Fig. 1). With the exception of TirM (the intimin binding domain of Tir), serum IgG antibody responses to all antigens were detectable 2 weeks postinfection and were maximal 4 to 6 weeks postinfection. IgG responses to TirM were of a lower titer and became undetectable 8 weeks postinfection (Fig. 1A). These data imply that several LEE-encoded antigens are expressed in vivo during an infection with C. rodentium and are targets of the host immune response.

FIG. 1.

Mice infected with C. rodentium mount IgG and IgA antibody responses to LEE-encoded virulence determinants. C3H/Hej mice (n = 5) were orally infected with 107 CFU of C. rodentium, and sera were collected on days 14, 28, 42, and 56. The data depict the mean serum IgG (A) and IgA (B) antibody titers to the LEE-encoded antigens Int280α, Int280β, EspA, EspB, and TirM and to antigens from a whole-cell (WC) lysate. Immune responses to the control antigen, MBP, were not detected. The antibody titer was arbitrarily defined as the reciprocal of the dilution giving an optical density of 0.3 at 490 nm.

Mice infected with C. rodentium develop acquired immunity.

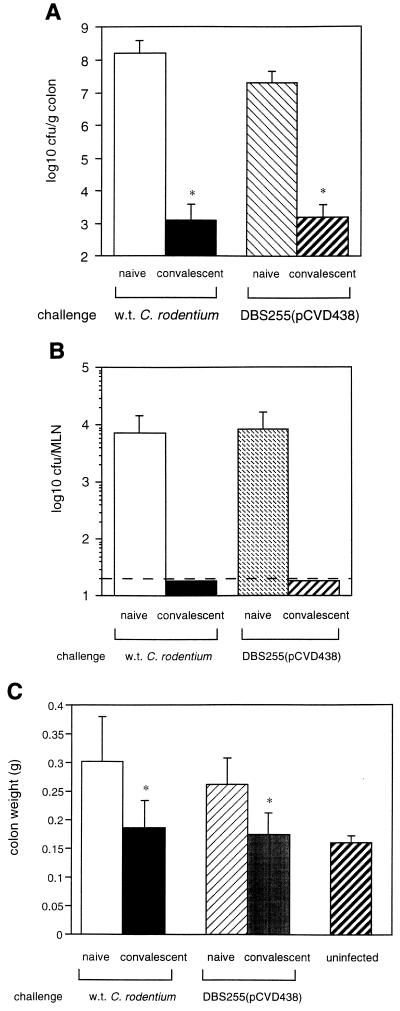

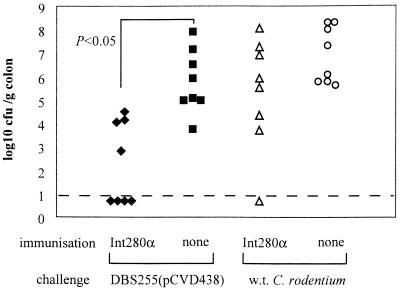

The development of acquired immunity to enteric bacterial pathogens which colonize via the formation of A/E lesions has been implied (11) but never formally shown in animals or humans. To address this, two groups of C3H/Hej mice were orally infected with 7 × 107 CFU of C. rodentium. Three months later, one group of convalescent mice was rechallenged with 8 × 108 CFU of wild-type C. rodentium and the second group was rechallenged with 2 × 109 CFU of a C. rodentium strain expressing α intimin [DBS255(pCVD438)]. Age- and sex-matched naive mice were orally challenged in parallel with convalescent mice. Eleven days after challenge the pathogen burden in mouse tissues was determined in all groups. Compared to naive animals, convalescent mice harbored significantly fewer challenge bacteria in colons (Fig. 2A) and draining lymph nodes (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the colon weights of challenged mice, a good indicator of the degree of infection-driven pathology in the mucosa (22), were substantially lower in convalescent mice compared to naive animals (Fig. 2C). These data clearly show that mice infected with C. rodentium develop acquired immunity to reinfection with C. rodentium strains expressing either homologous or heterologous intimin types.

FIG. 2.

Mice infected with C. rodentium develop acquired immunity. C3H/Hej mice (n = 16) were orally infected with 7 × 107 CFU of C. rodentium. Three months later, half the convalescent mice were rechallenged with 8 × 108 CFU of wild-type C. rodentium, and the other half were challenged with 2 × 109 CFU of DBS255(pCVD438). The data depict the mean number of wild-type (w.t.) C. rodentium or DBS255(pCVD438) (error bars, standard deviation) recovered from the colons (A) or the MLNs (B) of convalescent mice or age-matched naive mice 11 days after oral challenge. Significantly fewer wild-type C. rodentium or DBS255(pCVD438) organisms were recovered from the colons of convalescent mice (∗, P < 0.05). (C) Immunity to C. rodentium also prevents colonic pathology. The data depict the mean colon weights (error bars, standard deviation) of convalescent mice or age-matched naive 11 days after oral rechallenge. The mean colon weight of rechallenged convalescent mice was significantly less than that of naive mice (∗, P < 0.05). These data reflect one of two separate experiments which gave similar results.

Induction of Int280α-specific immune responses using mucosal or parenteral immunization strategies.

Intimin plays an essential role in the formation of A/E lesions and an important role in the pathogenesis of EPEC, EHEC, and C. rodentium (10, 12, 15). The demonstrated importance of intimin in facilitating bacterial colonization in vivo led to the hypothesis that an intimin-based vaccine may prevent infections caused by bacteria which colonize the host via A/E lesion formation. To address this hypothesis, a highly purified preparation of recombinant Int280α from EPEC E2348/69 was used as an immunogen in mucosal and parenteral vaccination regimes. Mice were vaccinated i.n. or s.c. with or without the use of E. coli LT or mutant derivatives as adjuvants.

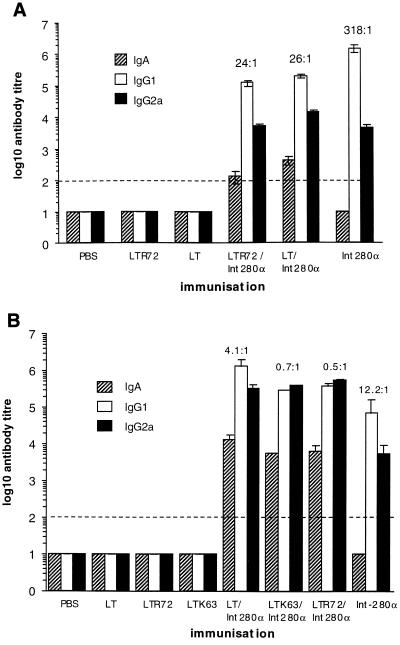

Mice were s.c. immunized three times, on days 0, 14, and 28, with 10 μg of Int280α with or without adjuvant. Mice immunized with Int280α in the absence of adjuvant mounted serum IgG1 and IgG2a but not IgA antibody responses to Int280α (Fig. 3A). The coadministration of LT or LTR72 with Int280α prompted a more rapid Ig response to Int280α (data not shown) but did not, however, increase the magnitude of the final Int280α-specific IgG1 or IgG2a titer compared to that obtained in mice s.c. immunized with Int280α alone (Fig. 3A). Surprisingly, s.c. coadministration of LT or LTR72 with Int280α prompted a weak Int280α-specific serum IgA response, although this occurred in only a small number of mice. Int280α-specific IgG1 was the predominant IgG subclass elicited by parenteral vaccination, although the ratio of IgG1 to IgG2a was reduced when Int280α was coadministered with the adjuvant LT or LTR72 (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Humoral immune responses to Int280α in mice immunized with Int280α plus or minus an enterotoxin-based adjuvant. (A) The data depict the mean (error bars, standard deviation) IgA, IgG1, and IgG2a serum antibody responses in mice immunized s.c. (n = 5) (A) or i.n. (n = 5) (B) with 10 μg of Int280α plus or minus 1 μg of the indicated enterotoxin-based mucosal adjuvant. Mice were immunized on three separate occasions, 2 weeks apart. Serum antibody responses were measured 12 days after the last immunization. The ratio of IgG1 to IgG2a is shown above the respective columns. The dashed line represents the limit of detection.

In mucosal immunization regimes, mice were immunized i.n. three times, on days 0, 14, and 28, with 10 μg of Int280α with or without an enterotoxin-based adjuvant. Mice i.n. administered 10 μg of Int280α mounted serum IgG1 and IgG2a, but not IgA, antibody responses to Int280α. Codelivery of 1 mg of LT, LTR72, or LTK63 with Int280α significantly increased the serum IgG1 and IgG2a antibody response to Int280α. Moreover, the addition of a mucosal adjuvant resulted in the induction of Int280α-specific serum IgA responses (Fig. 3B). Analysis of Int280α-specific IgG subclasses in i.n. immunized mice showed a predominance of IgG1 over IgG2a. As occurred in s.c. immunized mice, the ratio of IgG1 to IgG2a was reduced when Int280α was coadministered with an enterotoxin-based adjuvant (Fig. 3B).

Collectively, these data show that Int280α is immunogenic in vivo and that enterotoxin-based adjuvants can modulate the kinetic and isotype of the elicited humoral immune response.

Efficacy of Int280α-based vaccination strategies for the prevention of C. rodentium colonization in C3H/Hej mice.

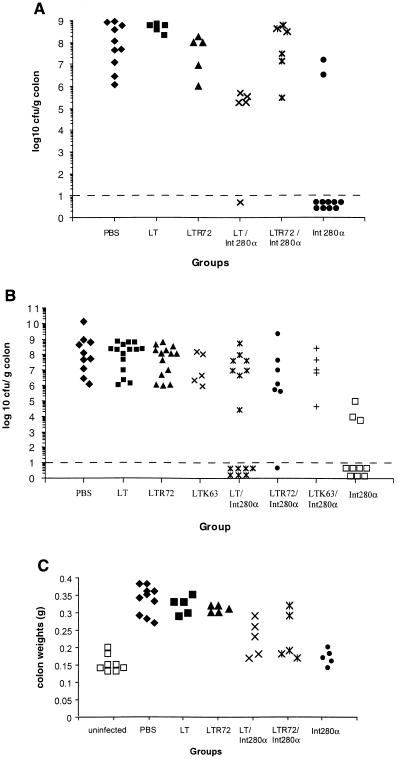

DBS255(pCVD438), a recombinant C. rodentium strain which only expresses intimin α, is virulent in mice, and induces mucosal pathology in the distal colon similar to that induced by wild-type C. rodentium (22). To determine whether vaccination with Int280α could modulate the outcome of infection with DBS255(pCVD438), mice were i.n. or s.c. immunized three times, on days 0, 14, and 28, with 10 μg of Int280α with or without adjuvant. In separate experiments, mice were orally challenged with between 2 × 107 to 3 × 107 CFU of DBS255(pCVD438) 13 or 16 days after the last immunization. Mice were killed 14 days postchallenge, the colon of each mouse was weighed and homogenized, and the pathogen burden was determined by viable count. Mice immunized s.c. with PBS or adjuvant alone had uniformly high C. rodentium counts in the colon (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the colons of mice immunized s.c. (Fig. 4A) with Int280α alone harbored significantly fewer challenge bacteria than the colons of naive or control animals. Surprisingly, mice immunized with Int280α together with a mucosal adjuvant were more susceptible to colonic infection than mice which received Int280α alone (Fig. 4A). Similar results were obtained in i.n. immunized mice. Mice immunized i.n. with PBS or an adjuvant had uniformly high C. rodentium counts in the colon (Fig. 4B). The pathogen burden was reduced, however, if mice were immunized i.n. with Int280α alone. As occurred in s.c. immunized animals, the addition of a mucosal adjuvant with Int280α negated some of the protective efficacy of i.n. vaccination using Int280α alone (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Vaccination using Int280α alone protects mice from C. rodentium colonization. C3H/Hej mice were immunized three times, 2 weeks apart, and orally challenged with 2 × 107 to 3 × 107 CFU of DBS255(pCVD438) 13 or 16 days after the last immunization. Mice were killed 14 days after challenge, and the number of viable DBS255(pCVD438) organisms present in colonic tissue was determined by viable count. The data depict the number of challenge bacteria recovered from the colons of individual mice immunized either s.c. (A) or i.n. (B) with 10 μg of Int280α plus or minus 1 μg of an enterotoxin-based mucosal adjuvant. In the group immunized s.c., significantly fewer C. rodentium cells were recovered from the colons of mice vaccinated with Int280α compared to PBS-immunized mice (∗, P < 0.05 [Mann-Whitney t test]). In i.n. immunized mice, significantly fewer C. rodentium cells were recovered from the colons of mice vaccinated with Int280α plus or minus LT compared to PBS-immunized mice (∗, P < 0.05 [Mann-Whitney t test]). The dashed line represents the limit of detection. These data are pooled from two separate experiments. (C) Mice immunized with Int280α s.c. also developed less severe colitis. The data depict the individual colon weights of s.c. vaccinated mice 14 days after challenge. The colon weights of Int280α-immunized mice were significantly less than those of PBS-, LT-, or LTR72-immunized mice (P < 0.05 [Student's t test]) and not significantly different from those observed for uninfected controls.

Colitis in C. rodentium-infected mice is characterized by crypt hyperplasia and an increase in colon weight per unit length (22). One effect of limiting DBS255(pCVD438) infection in the colon of Int280α-immunized mice was to diminish the severity of colitis as measured by colon weight. Mice immunized s.c. with Int280α alone had significantly lower colon weights per unit length than animals immunized with PBS, LT, or LTR72 (Fig. 4C).

Taken together, these data show that an appropriately administered Int280α-based vaccine modulates the severity of a C. rodentium infection and, correspondingly, the extent of colitis in infected animals.

An Int280α-based vaccination strategy limits systemic dissemination of C. rodentium

The vaccine efficacy attained by s.c. immunization with Int280α alone was verified in a further experiment. Groups of C3H/Hej mice (n = 5) were vaccinated s.c. three times, 2 weeks apart, with 10 μg of the irrelevant antigen Ova, 10 μg of Int280α, or 10 μg of PBS. All mice were orally challenged with 3 × 107 CFU of DBS255(pCVD438) 14 days after the last immunization. C3H/Hej mice which received 10 μg of Int280α s.c. had significantly fewer challenge bacteria in colons (Table 1) compared to either PBS or Ova immunized mice. In addition, there were significantly fewer challenge bacteria in spleens and MLNs of Int280α-immunized mice compared to Ova-immunized mice.

TABLE 1.

s.c. vaccination with Int280α limits systemic dissemination of DBS255(pCVD438)

| Immunization | No. of DBS255(pCVD438) MLNs/tissuea

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | MLN | Colon | |

| Ova | 3.04 ± 1.7 | 4.27 ± 0.6 | 8.13 ± 0.7 |

| PBS | 2.72 ± 1.85 | 3.07 ± 1.13 | 7.78 ± 2.05 |

| Int280α | 1.12 ± 0.95c | 1.6 ± 1.24c | 1.58 ± 1.24b |

Values are geometric means ± standard deviations.

Significantly different from Ova- or PBS-immunized mice (P <0.05 [Student's t test]).

Significantly different from Ova-immunized mice (P < 0.05 [Student's t test]).

Specificity of immunity elicited by Int280α vaccination.

Five distinct intimin subtypes (α, β, γ, δ, and ɛ) have been described based on sequence variation within the C-terminal 280 amino acids. These intimin subtypes are also antigenically different (1). Therefore, a vaccine based on Int280α may not necessarily protect against infections caused by E. coli strains expressing a heterologous intimin type. To address this hypothesis in the context of C. rodentium infection, C3H/Hej mice were vaccinated s.c. three times with 10 μg of Int280α or PBS and then orally challenged with 108 CFU of DBS255(pCVD438) or 108 CFU of wild-type C. rodentium (which expresses intimin β). Mice vaccinated with Int280α were resistant to DBS255(pCVD438) infection but not to wild-type C. rodentium infection. Mice vaccinated with PBS were susceptible to infection with both DBS255(pCVD438) and wild-type C. rodentium (Fig. 5). These data imply that immunity elicited by Int280α vaccination is specific for this intimin type and does not offer cross-protection against strains bearing a heterologous intimin type.

FIG. 5.

Vaccination using Int280α alone does not prevent colonic colonization by C. rodentium expressing Int280β. C3H/Hej mice (n = 8/group) were immunized s.c. with 10 μg of Int280α alone, three times, 2 weeks apart, and orally challenged with 108 CFU of DBS255(pCVD438) or 108 CFU of wild-type (w.t.) C. rodentium. The data depict the numbers of challenge bacteria recovered from the colons of individual mice 15 days later. Fewer DBS255(pCVD438) cells were recovered from the colons of mice immunized with Int280α alone compared to the number recovered from naive mice (P = 0.05 [Mann-Whitney t test]). The data are pooled from two separate experiments. The dashed line represents the limit of detection.

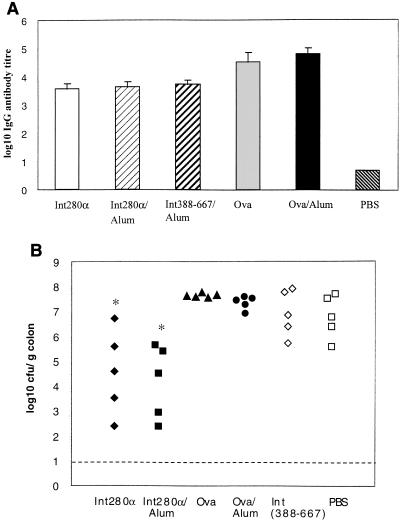

An approach which bypasses the apparent specificity of Int280α vaccination is to use domains of intimin that are conserved between intimin subtypes; this type of vaccine might evoke protective immunity against a range of pathogenic E. coli strains possessing diverse intimin types. To address this hypothesis in the context of C. rodentium, mice were vaccinated with a recombinant polypeptide corresponding to amino acids 388 to 667 of the mature intimin molecule. The amino acid sequence of this region of intimin, which corresponds to two putative surface-exposed Ig-like domains, is highly conserved across all intimin types. Mice were vaccinated s.c. three times, 2 weeks apart, with Int388–667 in the presence of the adjuvant Al(OH)3. In parallel, mice were vaccinated s.c. with Int280α plus or minus Al(OH)3. Control groups of mice received the irrelevant antigen, Ova, in the presence or absence of Al(OH)3. Measurement of serum IgG antibody responses to the three different antigens demonstrated the induction of robust humoral immune responses to each antigen (Fig. 6A). The coadministration of alum with Int280α or Ova did not, however, increase the final magnitude of the IgG response (Fig. 6A). All mice were orally challenged with 6 × 107 CFU of DBS255(pCVD438) 12 days after the last immunization. The number of viable DBS255(pCVD438) cells in the colons (Fig. 6B), spleens and draining lymph nodes (data not shown) of challenged mice was determined 12 days later. As previously shown (Fig. 4A), mice immunized s.c. with Int280α were significantly more resistant to DBS255(pCVD438) challenge compared to PBS-immunized mice (P = 0.03 for Int280α s.c. versus PBS s.c.; P = 0.02 for Int280α-alum s.c. versus PBS s.c.). Resistance to challenge in mice vaccinated with Int280α was independent of the use of Al(OH)3 as an adjuvant. In contrast, mice immunized with Int388–667 were as susceptible to DBS255(pCVD438) colonization as PBS-immunized mice or mice immunized with Ova (Fig. 6B). These results imply that Int388–667 is not a protective antigen or alternatively that the method of Int388–667 vaccination evoked immune responses which were not sufficiently robust or of an inappropriate type to offer protection to mice challenged with DBS255(pCVD438).

FIG. 6.

s.c. administration of Int388–667 elicits immune responses but does not prevent colonic colonization by C. rodentium. C3H/Hej mice (n = 5/group) were immunized s.c. three times, 2 weeks apart, with 10 μg of Int280α alone or Int280α emulsified in alum. Similarly, mice were immunized with 10 μg of Int388–667 emulsified in alum. Control mice were immunized with PBS, 10 μg of Ova, or 10 μg of Ova emulsified in alum. (A) The data depict the mean (error bars, standard deviation) serum IgG antibody titers specific for Int280α, Int388–667 or Ova after three immunizations. All mice were orally challenged with 6 × 107 CFU of DBS255(pCVD438) 12 days after the last immunization. (B) The data depict the numbers of challenge bacteria recovered from the colons of individual mice 14 days later. There were significantly fewer challenge bacteria in colons of mice immunized with Int280α alone (∗, P < 0.05 versus PBS group [Mann-Whitney t test]) or Int280α emulsified in alum (∗ P < 0.05 versus PBS group [Mann-Whitney t test]) compared to PBS-immunized mice.

DISCUSSION

The host immune response to pathogens that colonize the gut via formation of A/E lesions is poorly described. Here we show that the LEE-encoded antigens intimin, EspA, EspB, and, to a lesser extent, TirM are the targets of significant and long-lived humoral immune responses in mice infected with C. rodentium. Furthermore, our data show that mice previously infected with C. rodentium develop acquired immunity to reinfection with a C. rodentium strain expressing either a homologous or heterologous intimin type. This is the first study to definitively demonstrate acquired immunity to a pathogen that colonizes the host via the formation of A/E lesions. C. rodentium infection of mice can also be employed as a model system in which to test LEE-encoded proteins as candidate vaccine antigens. In this system, Int280α was used as a vaccine to ameliorate the severity of an infection caused by a recombinant C. rodentium strain expressing intimin α. This represents the first in vivo evidence to support the use of defined intimin domains as candidate EPEC or EHEC vaccine antigens.

Rapid and significant progress has been made defining the molecular basis of EPEC- and EHEC-host cell interactions in vitro (reviewed in reference 44). Conversely, however, immunological responses during and after in vivo infection have been poorly described. IgG antibodies against bundle-forming pili, EspB, EspA, and intimin have been detected in the sera of many but not all Brazilian children naturally infected with EPEC (33). The same antigens are also recognized by IgA antibodies in the colostrum of mothers in Mexico (37). The intimin binding domain of Tir, TirM, is also recognized by serum IgG and colostrum IgA antibodies from Brazilian mothers (40). Children infected with EHEC also mount serum Ig responses to intimin, Tir, EspA, and EspB (23, 29). These data from humans match the spectrum of antibody responses detected in sera of mice infected with C. rodentium. Infected mice develop serum IgG and IgA antibody responses to Int280β, TirM, EspB, and EspA. These studies complement existing data demonstrating the induction of mucosal IgA responses to intimin and EspB in C. rodentium-infected mice (15). Collectively, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that the LEE-encoded antigens TirM, EspB, EspA, and intimin are expressed in vivo and are exposed to B cells in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue and/or lamina propria of humans infected with EPEC or mice infected with C. rodentium. In turn, immune responses to these antigens may potentially contribute to immune-mediated resolution of infection.

The development of acquired immunity to EPEC infection in humans has been alluded to (11) but not convincingly shown. In this study, animals previously infected with C. rodentium were highly resistant to rechallenge with either wild-type C. rodentium or DBS255(pCVD438). Resistance to bacterial colonization also prevented the development of infectious colitis in these mice. These data demonstrate that the immune response which develops during C. rodentium infection or subsequent to resolution of infection is of an appropriate magnitude, type, and specificity to prevent reinfection. This is an important observation and should, in the future, allow a dissection of the components of the acquired immune response which mediate immunity. These kinds of studies will help facilitate the rational design of vaccines to prevent infections caused by pathogens that induce A/E lesions.

Intimin is an essential virulence determinant of C. rodentium in mice (41) and EHEC in gnotobiotic pigs (12). Intimin also contributes markedly to the virulence of EPEC in humans (10). In these pathogens, intimin most likely contributes to virulence by facilitating tight binding of the bacterium to the epithelial cell membrane via intimin-Tir interactions. The aim of the studies described here was to determine whether vaccine-induced immune responses to Int280α could modulate or prevent in vivo bacterial colonization by C. rodentium strains expressing either homologous or heterologous intimin types. Surprisingly, the most efficacious routes of vaccination for the prevention of C. rodentium colonization in mice were s.c. and i.n. delivery of Int280α in the absence of a mucosal adjuvant. This vaccination regimen significantly reduced the number of viable DBS255(pCVD438) cells but not wild-type C. rodentium recovered from colonic and systemic tissue of orally challenged mice. Vaccination by s.c. or i.n. administration of Int280α also reduced the severity of the colitis that is a characteristic hallmark of C. rodentium infection in the murine colon.

Vaccination using Int280α clearly imparted a degree of type-specific protective immunity to mice. However, the anatomical location and immunological mechanisms through which vaccination confers resistance to DBS255(pCVD438) colonization remains unknown. Indeed, few clues are provided by comparing immune responses elicited by s.c. or i.n. administered Int280α with those of other, less efficacious vaccination methods. Vaccination by s.c. or i.n. administration of Int280α elicited strong Int280α-specific serum IgG responses, with a bias towards IgG1 over IgG2a, and T cells which produced gamma interferon upon antigen restimulation (data not shown). A similar spectrum of responses was elicited in mice immunized parenterally or mucosally with Int280α in the presence of a mucosal adjuvant, although the bias towards IgG1 over IgG2a was typically less pronounced in these animals. Additionally, the use of a mucosal adjuvant with Int280α evoked serum IgA responses in mucosally immunized mice. Despite the absence of an immunological correlate of protection in appropriately immunized animals, the concept of efficacious vaccination against mucosal pathogens by parenteral immunization is not new. For example, mice immunized parenterally with urease admixed with LT or the nontoxic B subunit as adjuvant were as protected from Helicobacter pylori challenge as orally immunized mice (45). Furthermore, numerous parenteral vaccines used in humans, including the Salk polio vaccine and the pneumococcal, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and shigella O-specific polysaccharide conjugates, have proven efficacious (9, 26, 39).

The anatomical location in which vaccine-elicited Int280α-specific immune responses mediate their effect on C. rodentium is unknown. Potentially, Int280α-specific IgG may have an opsonic role for bacteria which translocate across the epithelium. Additionally, Int280α-specific antibodies which have translocated from the serum to the gut lumen via transhepatic delivery mechanisms (7) may interact with luminal C. rodentium and exhibit antiadhesin properties.

One aspect of the humoral immune response to Int280α which was not examined in this study is the avidity of the antigen-specific antibody response. Potentially, administration of Int280α evokes specific antibody responses which are of higher avidity than those elicited by administration of Int280α with an enterotoxin-based mucosal adjuvant. Biologically, relatively high-avidity Int280α-specific antibody may have reduced opsonic activity or blocking capacity and may thereby have a reduced ability to inhibit or limit colonization of DBS255(pCVD438) on the colonic epithelium. The relationship between antibody avidity and biological activity has been clearly demonstrated for vaccine-elicited antibody responses to the capsular polysaccharides from pneumococci and H. influenzae (19, 30, 43).

Collectively, the results presented here support the inclusion of intimin as a component of a type-specific vaccine against pathogens like EPEC and EHEC. Other bacterial proteins shown to be critical for A/E lesion formation and which are recognized by the immune system of infected hosts (e.g., EspA) may also represent attractive candidate vaccine antigens. In addition, this study highlights the usefulness of the C. rodentium mouse model for studying host responses and naturally acquired or vaccine-elicited immunity to a pathogen which uses A/E lesion formation for host colonization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust grants to G.D. and G.F.

M.G.-M. and C.P.S. contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adu-Bobie J, Frankel G, Bain C, Goncalves A G, Trabulsi L R, Douce G, Knutton S, Dougan G. Detection of intimins alpha, beta, gamma, and delta, four intimin derivatives expressed by attaching and effacing microbial pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:662–668. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.662-668.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An H, Fairbrother J M, Desautels C, Mabrouk T, Dugourd D, Dezfulian H, Harel J. Presence of the LEE (locus of enterocyte effacement) in pig attaching and effacing Escherichia coli and characterization of eae, espA, espB and espD genes of PEPEC (pig EPEC) strain 1390. Microb Pathog. 2000;28:291–300. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barthold S W. The microbiology of transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Lab Anim Sci. 1980;30:167–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barthold S W, Coleman G L, Jacoby R O, Livestone E M, Jonas A M. Transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Vet Pathol. 1978;15:223–236. doi: 10.1177/030098587801500209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batchelor M, Knutton S, Caprioli A, Huter V, Zanial M, Dougan G, Frankel G. Development of a universal intimin antiserum and PCR primers. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3822–3827. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3822-3827.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beutin L. Escherichia coli as a pathogen in dogs and cats. Vet Res. 1999;30:285–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouvet J P, Fischetti V A. Diversity of antibody-mediated immunity at the mucosal barrier. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2687–2691. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2687-2691.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.China B, Jacquemin E, Devrin A C, Pirson V, Mainil J. Heterogeneity of the eae genes in attaching/effacing Escherichia coli from cattle: comparison with human strains. Res Microbiol. 1999;150:323–332. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen D, Ashkenazi S, Green M S, Gdalevich M, Robin G, Slepon R, Yavzori M, Orr N, Block C, Ashkenazi I, Shemer J, Taylor D N, Hale T L, Sadoff J C, Pavliakova D, Schneerson R, Robbins J B. Double-blind vaccine-controlled randomised efficacy trial of an investigational Shigella sonnei conjugate vaccine in young adults. Lancet. 1997;349:155–159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)06255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnenberg M S, Tacket C O, James S P, Losonsky G, Nataro J P, Wasserman S S, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Role of the eaeA gene in experimental enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:1412–1417. doi: 10.1172/JCI116717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnenberg M S, Tacket C O, Losonsky G, Frankel G, Nataro J P, Dougan G, Levine M M. Effect of prior experimental human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection on illness following homologous and heterologous rechallenge. Infect Immun. 1998;66:52–58. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.52-58.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnenberg M S, Tzipori S, McKee M L, O'Brien A D, Alroy J, Kaper J B. The role of the eae gene of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in intimate attachment in vitro and in a porcine model. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:1418–1424. doi: 10.1172/JCI116718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douce G, Fontana M, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Intranasal immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of site-directed mutant derivatives of cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2821–2828. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2821-2828.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankel G, Candy D C, Fabiani E, Adu-Bobie J, Gil S, Novakova M, Phillips A D, Dougan G. Molecular characterization of a carboxy-terminal eukaryotic-cell-binding domain of intimin from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4323–4328. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4323-4328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frankel G, Phillips A D, Novakova M, Field H, Candy D C, Schauer D B, Douce G, Dougan G. Intimin from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli restores murine virulence to a Citrobacter rodentium eaeA mutant: induction of an immunoglobulin A response to intimin and EspB. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5315–5325. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5315-5325.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frankel G, Phillips A D, Rosenshine I, Dougan G, Kaper J B, Knutton S. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:911–921. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gansheroff L J, Wachtel M R, O'Brien A D. Decreased adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells in the presence of antibodies that recognize the C-terminal region of intimin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6409–6417. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6409-6417.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giuliani M M, Del Giudice G, Giannelli V, Dougan G, Douce G, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. Mucosal adjuvanticity and immunogenicity of LTR72, a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin with partial knockout of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1123–1132. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granoff D M, Lucas A H. Laboratory correlates of protection against Haemophilus influenzae type b disease. Importance of assessment of antibody avidity and immunologic memory. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;754:278–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartland E L, Batchelor M, Delahay R M, Hale C, Matthews S, Dougan G, Knutton S, Connerton I, Frankel G. Binding of intimin from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to Tir and to host cells. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:151–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins L M, Frankel G, Connerton I, Goncalves N S, Dougan G, MacDonald T T. Role of bacterial intimin in colonic hyperplasia and inflammation. Science. 1999;285:588–591. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins L M, Frankel G, Douce G, Dougan G, MacDonald T T. Citrobacter rodentium infection in mice elicits a mucosal Th1 cytokine response and lesions similar to those in murine inflammatory bowel disease. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3031–3039. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3031-3039.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins C, Chart H, Smith H R, Hartland E L, Batchelor M, Delahay R M, Dougan G, Frankel G. Antibody response of patients infected with verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli to protein antigens encoded on the LEE locus. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:97–101. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-1-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jerse A E, Gicquelais K G, Kaper J B. Plasmid and chromosomal elements involved in the pathogenesis of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3869–3875. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3869-3875.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson E, Barthold S W. The ultrastructure of transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 1979;97:291–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaul D, Ogra P L. Mucosal responses to parenteral and mucosal vaccines. Dev Biol Stand. 1998;95:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly G, Prasannan S, Daniell S, Frankel G, Dougan G, Connerton I, Matthews S. Sequential assignment of the triple labelled 30.1 kDa cell-adhesion domain of intimin from enteropathogenic E. coli. J Biomol NMR. 1998;12:189–191. doi: 10.1023/a:1008227103121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knutton S, Rosenshine I, Pallen M J, Nisan I, Neves B C, Bain C, Wolff C, Dougan G, Frankel G. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:2166–2176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Frey E, Mackenzie A M, Finlay B B. Human response to Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection: antibodies to secreted virulence factors. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5090–5095. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5090-5095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucas A H, Granoff D M. Functional differences in idiotypically defined IgG1 anti-polysaccharide antibodies elicited by vaccination with Haemophilus influenzae type B polysaccharide-protein conjugates. J Immunol. 1995;154:4195–4202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo Y, Frey E A, Pfuetzner R A, Creagh A L, Knoechel D G, Haynes C A, Finlay B B, Strynadka N C. Crystal structure of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli intimin-receptor complex. Nature. 2000;405:1073–1077. doi: 10.1038/35016618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magagnoli C, Manetti R, Fontana M R, Giannelli V, Giuliani M M, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. Mutations in the A subunit affect yield, stability, and protease sensitivity of nontoxic derivatives of heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5434–5438. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5434-5438.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez M B, Taddei C R, Ruiz-Tagle A, Trabulsi L R, Giron J A. Antibody response of children with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection to the bundle-forming pilus and locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded virulence determinants. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:269–274. doi: 10.1086/314549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGraw E A, Li J, Selander R K, Whittam T S. Molecular evolution and mosaic structure of alpha, beta, and gamma intimins of pathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:12–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moon H W, Whipp S C, Argenzio R A, Levine M M, Giannella R A. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1340–1351. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1340-1351.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oswald E, Schmidt H, Morabito S, Karch H, Marches O, Caprioli A. Typing of intimin genes in human and animal enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: characterization of a new intimin variant. Infect Immun. 2000;68:64–71. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.64-71.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parissi-Crivelli A, Parissi-Crivelli J M, Giron J A. Recognition of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence determinants by human colostrum and serum antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2696–2700. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2696-2700.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips A D, Frankel G. Intimin-mediated tissue specificity in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli interaction with human intestinal organ cultures. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1496–1500. doi: 10.1086/315404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robbins J B, Schneerson R, Szu S C. O-specific polysaccharide-protein conjugates for prevention of enteric bacterial diseases. In: Levine M M, Kaper J B, Cobon G S, editors. New generation vaccines. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1997. pp. 803–816. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanches M I, Keller R, Hartland E L, Figueiredo D M, Batchelor M, Martinez M B, Dougan G, Careiro-Sampaio M M, Frankel G, Trabulsi L R. Human colostrum and serum contain antibodies reactive to the intimin-binding region of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli translocated intimin receptor. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30:73–77. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200001000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schauer D B, Falkow S. The eae gene of Citrobacter freundii biotype 4280 is necessary for colonization in transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4654–4661. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4654-4661.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simmons C P, Ghaem-Magami M, Petrovska L, Lopes L, Chain B M, Williams N A, Dougan G. Immunomodulation using bacterial enterotoxins. Scand J Immunol. 2001;53:218–226. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usinger W R, Lucas A H. Avidity as a determinant of the protective efficacy of human antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2366–2370. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2366-2370.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vallance B A, Finlay B B. Exploitation of host cells by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8799–8806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weltzin R, Guy B, Thomas W D, Jr, Giannasca P J, Monath T P. Parenteral adjuvant activities of Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin and its B subunit for immunization of mice against gastric Helicobacter pylori infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2775–2782. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2775-2782.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]