Abstract

Introduction

Graves’ disease (GD) and concomitant thyroid nodules can be found in up to 44% of all cases, of which up to 17% are determined as malignant tumors. Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) seems to be found extremely rarely, which causes belated diagnosis.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old man was diagnosed with GD. Neck ultrasound revealed suspicious thyroid nodule, a fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed, and it revealed microfollicular hyperplasia, Bethesda IV. The patient was operated on and the histological examination confirmed MTC. Genetic testing revealed the sporadic form of MTC. Six weeks after the initial surgery, elevated tumor markers confirmed the persistence of the disease. The patient underwent a pyramidal lobe removal with a unilateral central compartment lymph node dissection. Histological analysis confirmed typical changes of MTC and a spread of the disease. 2 months after the lymphadenectomy, tumor markers and imaging examination revealed suspicious lymph nodes; this discovery was followed by a bilateral lymph nodes dissection and persistence of MTC confirmation.

Conclusion

An early detection of sporadic MTC with concomitant GD is challenging. We want to emphasize the benefits of calcitonin (Ctn) measurement in the blood sample and a Ctn immunocytochemistry detection in the case of an autoimmune thyroid disease and suspicious thyroid nodule before the radical treatment, despite the lack of universal recommendations for routine Ctn measurement, in order to reach an earlier diagnosis of the cancer, and to perform a more radical surgical treatment.

Keywords: Graves’ disease, Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Calcitonin

INTRODUCTION

An estimated mean prevalence of hyperthyroidism in Europe is 0.75% and 1.3% in USA (1, 2). According to epidemiological studies, the most frequent cause of hyperthyroidism is Graves’ disease (GD), with up to 20-30 annual cases per 100.000 individuals (3, 4), and has a population prevalence of 1–1.5%. Approximately 3% of women and 0.5% of men develop GD during their lifetime (5). Recent studies show that GD associated with thyroid nodules could be found in up to 44% of cases (6). The preoperative detection of thyroid nodules in GD shows a higher risk for thyroid cancer; the prevalence differs widely among different studies and reaches up to 17% (7, 8). The most common histological type of thyroid carcinoma in GD is papillary carcinoma, followed by follicular carcinoma. According to recent meta-analysis, the coexistence of GD and medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) seems to be very rare: MTC accounted for 0.6% of all cases in patients with GD (9). Until 2019, only 15 cases of this coincidence were reported in the literature, however, the coexistence of GD and MTC seemed to be incidental, with no clear relationship between gender, clinical features, tumor diameter (10). A timely diagnosis of MTC is challenging in clinical practice since MTC has no clinical signs and symptoms in the initial stages, and no specific ultrasonographic features. GD can also mask signs of a malignant process.

We will present a clinical case of recurrent sporadic MTC associated with GD in a middle-aged male, we will discuss whether it is possible to suspect cancer in its earliest stages and will compare with similar clinical cases.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 50-year-old man presented to an endocrinologist in July 2018, with complaints of weight loss (7 kg/8 months), general weakness and paroxysmal tachycardia. He had a history of euthyroid autoimmune thyroiditis in 2013: a supplementation of selenium was started and continued for several months. In 2017, the patient was diagnosed with thyrotoxicosis (thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) 0.003 uIU/mL (0.4 – 3.6), free thyroxine (FT4) 2.14 ng/dL (0.7 – 1.6), free triiodothyronine (FT3) 9.05 ng/L (2.17 – 3.35)): a treatment with methimazole 10 mg, twice a day, was started. He denied having any other chronic disease and had no history of cancer in his family.

Physical examination

The patient’s general physical examination did not show any clinically significant changes: a regular heart rate of 74 beats per minute, blood pressure 140/74 mmHg, height 180 cm, weight 61 kg (BMI 18.83 kg/m2). The local examination of the thyroid showed an enlarged and firm thyroid, without any palpable nodules.

Pre-operative ultrasound (US)

A high-resolution US examination of the neck reported a diffuse enlargement with decreased echogenicity, as well as a small markedly hypoechoic nodule of 0.9x0.7 cm in the middle portion of the left thyroid lobe, showing multiple micro- and macrocalcifications (EU-TIRADS 5). The findings in the diffuse tissue could signify either autoimmune thyroiditis or GD; the area in the left lobe of the thyroid could reveal either an old, calcified thyroid nodule or a possible thyroid cancer. No change in the cervical lymph nodes was observed.

Pre-operative laboratory tests and treatment

The preoperative thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO-Ab) levels were 941 IU/mL (0–12), thyroglobulin antibodies (Tg-Ab) levels 360 IU/mL (0-100) and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies (TSHR-Ab) levels 53 IU/mL (0-9); therefore, GD and autoimmune thyroiditis were confirmed. The methimazole dose was adjusted and the hormonal profile before the surgery reached normal ranges.

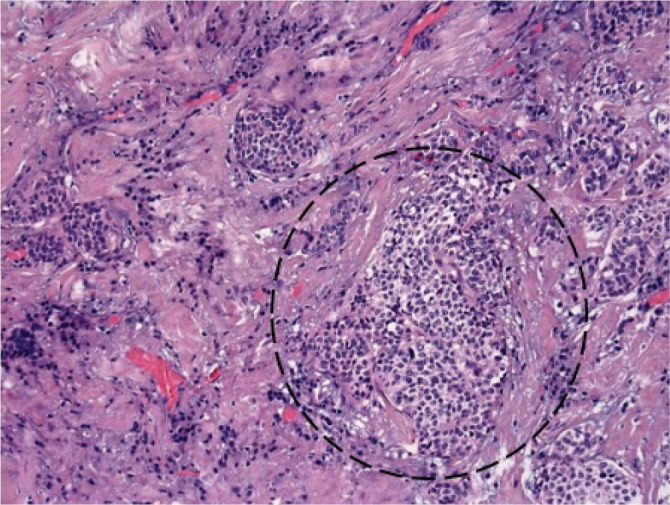

Pre-operative fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy from a nodule of the left thyroid lobe due to high risk of malignancy was done and FNA cytology was reported as microfollicular hyperplasia (Fig. 1), Bethesda IV. A case of follicular neoplasm could not be rejected, and the pathologist suggested these cytological findings combine with the clinical features.

Figure 1.

Microfollicular hyperplasia. Microfollicular and trabecular architecture are formed by numerous thyrocytes with enlarged, monomorphic, and eccentric nuclei, and grainy vacuolated cytoplasm. Expressed proliferation, numerous resorption vacuoles.

Because of the findings in the thyroid US, the microfollicular pattern and category IV in the FNA cytology, malignancy was suspected. The patient underwent a total thyroidectomy two weeks later, 47 g of thyroid tissue were removed. A treatment with 100 ug levothyroxine, once a day, was started.

Histological examination

The histological examination of the left thyroid lobe specimen showed an infiltrative growth of 0.9 cm tumor, with cells containing coarse and finely granular chromatin, arranged in nests in the background of the diffuse thyrotoxic goiter. The tumor showed positive immunostaining with calcitonin (Ctn) antibodies. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of MTC (Figs 2, 3).

Figure 2.

Histological findings of a primary tumor. Infiltrative growth of 0.9 cm tumor, with cells containing coarse granular chromatin, arranged in nests in the background of the diffuse thyrotoxic goiter. The nuclei are enlarged with a decreased amount of cytoplasm and intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemical staining for Ctn.

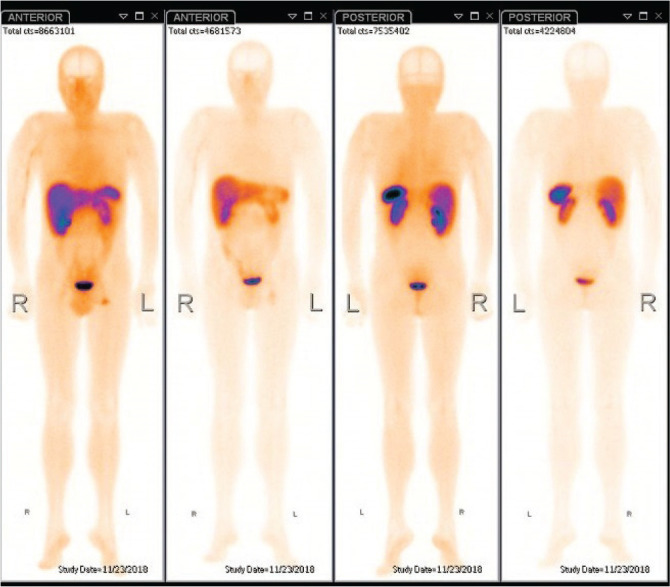

Post–operative imaging examination

Neither computed tomography (CT) nor X-ray showed any pathological changes. The neck US revealed a ~6.3x2.8 mm residual pyramidal lobe of the thyroid, on the left side of the thyroid cartilage. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with 99 mTc-Tektrotyd and single-photon-emission CT (SPECT) were carried out to visualize a suspected spread of the disease. However, the imaging did not show any tumor or metastasis with expression of somatostatin receptors (Fig. 4). One-week later, iodine-123-metaiodobenzylguanidine (123I-MIBG) scintigraphy was used to exclude expression of adrenergic receptors. A small adrenergic receptor-rich area was visualized left of the midline at the level of the vocal cords (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with 99mTc-Tektrotyd + neck, chest and abdominal SPECT/CT. No tumor or metastasis with expression of somatostatin receptors was found.

Figure 5.

Adrenergic receptor scintigraphy with 123I-MIBG + neck, chest and abdomen SPECT/CT. Area of adrenergic receptors slightly left of the midline, in front of the vocal cords.

Post-operative laboratory results

Six weeks after the initial surgery, laboratory tests showed elevated levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (11.8 ng/mL; (0–5.8)), Ctn (410 pg/mL (0-14.4)), with normal ionized calcium, total calcium and phosphorus levels. Plasma free metanephrines and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels were measured to rule out multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) syndrome; both levels were within normal ranges. The patient was also seen by a geneticist and underwent genetic testing to exclude MEN2 syndrome. A Germline REarranged during Transfection (RET) proto-oncogene mutation was not identified and the diagnosis of sporadic MTC was confirmed.

Further evaluation and management

Because of the elevated tumor marker levels and the presence of a small adrenergic receptor-rich area detected with MIBG scintigraphy, the persistence of cancer was suspected. Thyroid US was performed several times to evaluate the lymph nodes. The cervical lymph nodes appeared smaller than 1 cm at the level VI on the left side, without visible metastatic changes. The small adrenergic receptor-rich area, which was visualized on MIBG scintigraphy, revealed normal thyroid tissue, possibly from the pyramidal lobe. Pyramidal lobe removal and unilateral central compartment lymph node dissection were considered because the initial tumor was detected in the middle portion of the left thyroid lobe. In 2 out of 5 dissected lymph nodes (up to 0.8 cm), tumor cells with “salt-and-pepper” chromatin (Fig. 6) and amyloid deposits (Fig. 7) were found. These findings confirmed the typical changes of MTC and the spread of the disease. The tissue of the pyramidal lobe was without pathological changes.

Figure 6.

Lymph node. Tumor cells with “salt-and-pepper” chromatin.

Two months after the lymphadenectomy, tumor marker levels remained elevated (Ctn 194.8 pg/mL, CEA 9.2 ng/mL). The clinical case was discussed in a multidisciplinary team, neck CT and US were carried out. Radiological examination revealed suspicious lymph nodes, no bigger than 1 cm, in the left lateral compartment zones (level III and IV). The persistence of the disease was suspected, the patient underwent a third surgery; a bilateral lymph nodes dissection was performed. The histological examination showed MTC metastasis in 3 out of 8 dissected lymph nodes in the left lateral compartment: the maximum diameter of the dissected lymph node was 1.2 cm with a 0.55 cm metastasis. The lymph nodes of the right lateral compartment, up to 1.4 cm, appeared reactive, without metastatic changes. 3 months after the last lymphadenectomy, the tumor marker levels still remained elevated (Ctn 95 pg/mL, CEA 9.1 ng/mL). The persistence of cancer was suspected and a whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18] F-FDG) was carried out. However, no metabolically active tumor was detected.

To this day, the patient is following up with an oncologist. The disease is defined as in stable remission, with tumor markers higher than the upper limit, and a normal thyroid function with levothyroxine therapy.

DISCUSSION

It was previously thought that thyroid carcinoma in GD was a rare phenomenon (9). Since no clear pathognomonic features of MTC and GD are revealed, an early diagnosis of MTC, especially in GD, may represent a diagnostic challenge in clinical practice. After a review of literature, we decided to analyze possible causes of the late diagnosis and the spread of MTC in the background of GD in our patient.

A definite mechanism of carcinogenesis in thyroid tissue in GD still remains unclear. Current hypotheses include TSH binding to the TSH receptor and stimulation of the receptor. The stimulation may promote invasiveness and angiogenesis of cancer (11, 12). Such findings are seen in differentiated thyroid cancer and concomitant GD. In 1966, Williams discovered that MTC originated from the parafollicular C-cells of the thyroid (13). Later research revealed that C-cells do not have a TSH receptor on their surface. It was thought that the mechanism may be associated with MEN2 syndrome, however, in the end, none of the reported cases of GD with MTC were diagnosed as MEN syndrome. Thus, the mechanism of the association of GD with MTC is still unclear (14, 15).

Other authors tried to analyze general characteristics of the patients, diagnosed with concomitant GD and MTC. According to the literature, 80% of reported cases represented female gender. The mean age of patients reported in the literature was 44 years at presentation with a range of 30–70 years, thus our patient was in conformity with reported rates (10, 16). However, the exact mechanism of these links is not completely clarified, additional studies are needed.

Early detection and a timely surgery are crucial for a better prognosis of MTC. The thyroid US is considered the golden standard for thyroid imaging, because of its high sensitivity (17, 18). According to different authors, MTC may differ from papillary thyroid carcinoma in position, lesion size, shape, margins, vascularization, echogenicity, and presence of size of a cystic change, other studies have revealed similar or statistically insignificant differences between calcification in the MTC group, when compared with other types of thyroid cancer, thus, there are no generally approved recommendations on how to differentiate between malignancies (19-22). Other published clinical cases of coincidental GD and MTC also revealed variable US malignancy features (23, 24). In our case, only microcalcifications indicated a possible malignancy in the background of autoimmune thyroiditis or GD.

The C-cells of the thyroid produce several biologically active substances, of which Ctn and CEA are valuable tumor markers of MTC. However, Ctn and CEA are nonspecific, and levels can be affected in patients with other malignancies, chronic diseases and other conditions. Based on these factors, a routine measurement of Ctn and CEA in patients with thyroid nodules, without a suspicion of MTC, remains controversial (18). In the other hand, Silvestre C. et al. reported that a Ctn level measurement has a greater sensitivity than cytology (25). Similar clinical cases show that measurement of MTC tumor markers can lead to more accurate preoperative diagnosis which leads to a more radical surgical treatment. In the clinical case described by Donckier et al. (24), FNA biopsy of suspicious nodule in the background of GD, as in our case, was reported as Bethesda class IV follicular neoplasm, serum Ctn was highly elevated, a total thyroidectomy was performed with intraoperative confirmation of MTC, and this justified an adequate surgical extent with no further relapse of the diseases. Recently published clinical case of incidentally discovered MTC in the post-operative Graves’ patient also highlight possible benefits of preoperative Ctn measurement in case of nodular GD (26). However, in our case, preoperative Ctn measurement was not performed. Postoperative Ctn and CEA levels were elevated, indicating a recurrence of the disease or the incomplete removal of the MTC through radical surgery.

One of the most accurate diagnostic tools for the evaluation of thyroid nodules is FNA, when indicated. However, in clinical practice, the diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of FNA cytology may vary widely in cases of MTC (27-29). Recent meta-analysis reported that only 56% of histologically proven MTCs were correctly detected by cytology, and that immunohistochemistry analysis was rarely carried out on the FNA aspirate (30). In the case of autoimmune thyroid diseases (GD or autoimmune thyroiditis), type A folicular epithelium turns into type B epithelium (Hurthle cells, oncocytes or oxyphilic cells). Cytological examination showed that chromatin in those cells is not smooth: it may be similar to chromatin in MTC cells. Therefore, in the case of an autoimmune disease and clinical suspicion of malignancy, it is appropriate to differentiate these two pathologies by using immunocytochemistry (31). As well as in our case, Donckier JE et al. recently published a case report analyzing occurence of MTC with GD. The authors highlithed the possible link between autoimmunity, inflammation and carcinogenesis and hypothesized that the association of these two pathologies was not coincidental (24). In our case, the cytoplasmic intranuclear inclusions were not visible, the cells were formed in microfolicular/trabecular structures, and the chromatin was not smooth; in the absence of liquid based cytology and immunocytochemistry, the conclusion of microfolicular hyperplasia was made with a recommendation to combine the findings with other data. We want to emphasize that despite the possibility of a coincidental finding, in the case of autoimmune thyroid disease, when no evident features of papillary thyroid carcinoma are seen in cytological examination, the small size of the tumor is incompatible with follicular thyroid cancer (32, 33), therefore, MTC should be considered despite the absence of typical MTC features. In those cases, we recommend performing serum Ctn or an immunocytochemical staining for Ctn in order to achieve successful radical surgery and to prevent additional operations.

Approximately one-third of all MTC patients and more than 75% of patients with palpable MTC are diagnosed with a metastatic disease in surrounding tissues or regional lymph nodes (34, 35). When considering the extent of surgery in a case of thyroid tumor, it is crucial to evaluate the involvement of lymph nodes. US is considered to be the first-line imaging choice for lymph node assessment. However, based on different literature sources, the sensitivity of US in detecting metastatic lymph nodes of thyroid cancer varies widely, ranging from 30 to 95%, and is particularly more sensitive in the evaluation of lateral cervical compartment, compared to the central compartment lymph nodes. The difference in the sensitivity of US and the diagnostic accuracy may be influenced mainly by the expertise of the radiologist (36, 37). Thus, even if obvious US malignancy features in the lymph nodes are not detected, lymphadenectomy should be considered, depending on the localization of the tumor (38). Lymph node metastases can be predicted by identifying the location of the primary tumor within the thyroid gland. Tumors in the middle portion of the thyroid gland tend to spread first to the central compartment (38). Reoperation should also be considered in cases with persistently elevated tumor marker levels (39). Since we did not have any data about cervical metastases, the first lymphadenectomy was performed depending on the localization of the tumor. In the other hand, the determination of preoperative Ctn or stimulation tests would have led to a radical lymphadenectomy. The secondary lymphadenectomy included compartmental dissection of the image-positive lateral neck compartment, as recommended by the American Thyroid Association (40).

Genetic testing presents significant advantages for MTC diagnosis, especially since the morphologic heterogeneity in FNA cytology does not help to differentiate thyroid tumors. MTC can occur as an inherited or sporadic case and is associated in most cases with germline or somatic RET proto-oncogene mutations, respectively. We have performed a genetic analysis for RET oncogene mutations, however, no RET gene mutations were found and sporadic MTC with concomitant GD was confirmed. Only one clinical case of MTC occurring in GD in association with a RET proto-oncogene mutation has been reported, thus the association is still unclear (24). Genetic counseling and genetic testing for RET mutations are recommended in all MTC patients according to guidelines (40) and by other authors in concomitant GD and MTC (24).

In conclusion, early detection of sporadic MTC, especially with concomitant GD is challenging and complicated, making the prognosis less favorable. Many diagnostic tools are not sensitive or specific enough, and false negative results can mask the spread of a malignant process. We want to emphasize, that in the case of an autoimmune thyroid disease, presenting with clinical and cytological suspicion of a malignant tumor, it is always appropriate to think of MTC, to measure Ctn concentrations in a blood sample, and to perform Ctn immunocytochemistry before the surgery, combined with the results of a lymph nodes assessment with US, which can lead to earlier diagnosis of the cancer, and a more radical surgical treatment, including a lymphadenectomy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Garmendia Madariaga A, Santos Palacios S, Guillén-Grima F, Galofré JC. The incidence and prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in Europe: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):923–931. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, Hannon WH, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, Braverman LE, Serum TSH. T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):489–499. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussain YS, Hookham JC, Allahabadia A, Balasubramanian SP. Epidemiology, management and outcomes of Graves' disease-real life data. Endocrine. 2017;56(3):568–578. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith TJ, Hegedus L. Graves’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1552–1565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyström HF, Jansson S, Berg G. Incidence rate and clinical features of hyperthyroidism in a long-term iodine sufficient area of Sweden (Gothenburg) 2003-2005. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;78(5):768–776. doi: 10.1111/cen.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi HH, McHenry CR. Coexistent thyroid nodules in patients with Graves' disease: What is the frequency and the risk of malignancy? Am J Surg. 2018;216(5):980–984. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papanastasiou A, Sapalidis K, Goulis DG, Michalopoulos N, Mareti E, Mantalovas S, Kesisoglou I. Thyroid nodules as a risk factor for thyroid cancer in patients with Graves' disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies in surgically treated patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2019;91(4):571–577. doi: 10.1111/cen.14069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber KJ, Solorzano CC, Lee JK, Gaffud MJ, Prinz RA. Thyroidectomy remains an effective treatment option for Graves' disease. Am J Surg. 2006;191(3):400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staniforth JUL, Erdirimanne S, Eslick GD. Thyroid carcinoma in Graves' disease: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2016;27:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sapalidis K, Papanastasiou A, Michalopoulos N, Mantalovas S, Giannakidis D, Koimtzis GD, Florou M, Poulios C, Mantha N, Kesisoglou II. A Rare Coexistence of Medullary Thyroid Cancer with Graves Disease: A Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:1398–1401. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.917642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazzaferri EL. Thyroid cancer and Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70(4):826–829. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-4-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filetti S, Belfiore A, Amir SM, Daniels GH, Ippolito O, Vigneri R, Ingbar SH. The role of thyroid-stimulating antibodies of Graves' disease in differentiated thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(12):753–759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198803243181206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams ED. Histogenesis of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid. J Clin Pathol. 1966;19(2):114–118. doi: 10.1136/jcp.19.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu H, Cheng L, Jin Y, Chen L. Thyrotoxicosis with concomitant thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26(7):R395–R413. doi: 10.1530/ERC-19-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habra MA, Hijazi R, Verstovsek G, Marcelli M. Medullary thyroid carcinoma associated with hyperthyroidism: a case report and review of the literature. Thyroid. 2004;14(5):391–396. doi: 10.1089/105072504774193249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan SH, Rather TA, Makhdoomi R, Malik D. Nodular Graves’ disease with medullary thyroid cancer. Indian J Nucl Med. 2015;30:341–344. doi: 10.4103/0972-3919.164022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rago T, Cantisani V, Ianni F, Chiovato L, Garberoglio R, Durante C, Frasoldati A, Spiezia S, Farina R, Vallone G, Pontecorvi A, Vitti P. Thyroid ultrasonography reporting: consensus of Italian Thyroid Association (AIT), Italian Society of Endocrinology (SIE), Italian Society of Ultrasonography in Medicine and Biology (SIUMB) and Ultrasound Chapter of Italian Society of Medical Radiology (SIRM) J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41(12):1435–1443. doi: 10.1007/s40618-018-0935-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S, Shin JH, Han BK, Ko EY. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: comparison with papillary thyroid carcinoma and application of current sonographic criteria. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(4):1090–1094. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SH, Kim BS, Jung SL, Lee JW, Yang PS, Kang BJ, Lim HW, Kim JY, Whang IY, Kwon HS, Jung CK. Ultrasonographic findings of medullary thyroid carcinoma: a comparison with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10(2):101–105. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu MJ, Liu ZF, Hou YY, Men YM, Zhang YX, Gao LY, Liu H. Ultrasonographic characteristics of medullary thyroid carcinoma: a comparison with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(16):27520–27528. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu J, Li X, Wei X, Yang X, Zhao J, Zhang S, Guo Z. The application value of modified thyroid imaging report and data system in diagnosing medullary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2019;8(7):3389–3400. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng ZW, Zhang YJ, Li W, Shi T, Wu SG, Tan J. Relapse of hyperthyroidism after hemithyroidectomy in concurrent medullary thyroid cancer and Graves' disease. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2013;114(9):544–546. doi: 10.4149/bll_2013_114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donckier JE, Fervaille C, Bertrand C. Occurrence of sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma in Graves' disease in association with a RET proto-oncogene mutation. Acta Clin Belg. 2021:1–4. doi: 10.1080/17843286.2021.1920124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silvestre C, Sampaio Matias J, Proença H, Bugalho MJ. Calcitonin Screening in Nodular Thyroid Disease: Is There a Definitive Answer? Eur Thyroid J. 2019;8(2):79–82. doi: 10.1159/000494834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akin R, Gilley D, Tassone P. Incidentally discovered medullary thyroid carcinoma in the post-operative Graves' patient-A case report. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43(3):103450. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tee YY, Lowe AJ, Brand CA, Judson RT. Fine-needle aspiration may miss a third of all malignancy in palpable thyroid nodules: a comprehensive literature review. Ann Surg. 2007;246(5):714–720. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180f61adc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravetto C, Colombo L, Dottorini ME. Usefulness of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma: a retrospective study in 37,895 patients. Cancer. 2000;90(6):357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caraway NP, Sneige N, Samaan NA. Diagnostic pitfalls in thyroid fine-needle aspiration: a review of 394 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1993;9(3):345–350. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840090320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trimboli P, Treglia G, Guidobaldi L, Romanelli F, Nigri G, Valabrega S, Sadeghi R, Crescenzi A, Faquin WC, Bongiovanni M, Giovanella L. Detection rate of FNA cytology in medullary thyroid carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2015;82(2):280–285. doi: 10.1111/cen.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs . WHO Classification of Tumours, 4th Edition. In: Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, Rosai J, editors. 10. 2017. pp. 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamran SC, Marqusee E, Kim MI, Frates MC, Ritner J, Peters H, Benson CB, Doubilet PM, Cibas ES, Barletta J, Cho N, Gawande A, Ruan D, Moore FD, Jr, Pou K, Larsen PR, Alexander EK. Thyroid nodule size and prediction of cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(2):564–570. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Hakami HA, Alqahtani R, Alahmadi A, Almutairi D, Algarni M, Alandejani T. Thyroid Nodule Size and Prediction of Cancer: A Study at Tertiary Care Hospital in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7478. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roman S, Lin R, Sosa JA. Prognosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1252 cases. Cancer. 2006;107(9):2134–2142. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moley JF, DeBenedetti MK. Patterns of nodal metastases in palpable medullary thyroid carcinoma: recommendations for extent of node dissection. Ann Surg. 1999;229(6):880–888. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi JS, Kim J, Kwak JY, Kim MJ, Chang HS, Kim EK. Preoperative staging of papillary thyroid carcinoma: comparison of ultrasound imaging and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(3):871–878. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang HS, Orloff LA. Efficacy of preoperative neck ultrasound in the detection of cervical lymph node metastasis from thyroid cancer. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(3):487–491. doi: 10.1002/lary.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Wei WJ, Ji QH, Zhu YX, Wang ZY, Wang Y, Huang CP, Shen Q, Li DS, Wu Y. Risk factors for neck nodal metastasis in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: a study of 1066 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(4):1250–1257. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin LX, Moley JF. Surgery for lymph node metastases of medullary thyroid carcinoma: A review. Cancer. 2016;122(3):358–366. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wells SA, Jr, Asa SL, Dralle H, Elisei R, Evans DB, Gagel RF, Lee N, Machens A, Moley JF, Pacini F, Raue F, Frank-Raue K, Robinson B, Rosenthal MS, Santoro M, Schlumberger M, Shah M, Waguespack SG, American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma Revised American Thyroid Association guidelines for the management of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2015;25(6):567–610. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]