Abstract

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an inherited neurocutaneous disease characterized by multiple hamartomas in multiple organs. However, there is limited evidence about neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in patients with TSC, and routine screening of NETs is not recommended in the guidelines. Insulinomas are also an extremely rare disease. According to our knowledge, we presented the 10th TSC patient diagnosed with insulinoma in the literature. Thirty-two years old male patient diagnosed with TSC at the age of 27 due to typical skin findings, renal angiomyolipoma, history of infantile seizures, and cranial involvement was referred to our clinic. The main symptoms of the patient were palpitations, diaphoresis, confusion, and symptoms were improved after consuming sugary foods. Seventy-two hours fasting test was performed, and a low glucose level at 41 mg/dl, a high insülin level at 21.65 µIU/mL, and a high C-peptide level at 7.04 ng/mL were found at the 8th hour. In addition, a 12x7 mm lesion in the pancreatic tail was detected in abdominal imaging. Ga-68 PET-CT (gallium-68 positron emission tomography-computed tomography) detected an increased uptake of Ga-68 in the pancreatic tail. The patient underwent distal pancreatectomy, and pathological evaluation was consistent with an insulinoma. The patient’s symptoms improved postoperatively. Since in nearly all TSC cases, as in our case, neuropsychiatric abnormalities, such as epilepsy, are one of the main disease manifestations, and these symptoms may be confused with the clinical manifestations of hypoglycemia in insulinoma. Therefore, patients with newly developed neurological symptoms and behavioral defects should be evaluated in terms of insulinoma.

Keywords: Tuberous sclerosis complex, Insulinoma, Neuroendocrine tumors

INTRODUCTION

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an inherited neurocutaneous disorder caused by mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 tumor suppressor genes and characterized by multiple hamartomas in multiple organs (1, 2). The incidence of TSC has been estimated to be 1 in 5,800 live births, and clinical expression is quite variable (1, 2). Dermatological findings (tubers with hamartomatous cortical, subependymal nodules, subependymal giant cell tumor), neurocognitive disorders (infantile generalized seizures, learning disability, autism spectrum), renal lesions (angiomyolipomas, cysts, and renal cell carcinomas), and rhabdomyoma are observed in the disease course. However, there is limited evidence about neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in patients with TSC, and routine screening of NETs is not recommended in current guidelines (2).

Insulinomas are an extremely rare (annual incidence 1-3 / million) disease, but it is the most common functional pancreatic NETs. The most common clinical manifestation is fasting hypoglycemia with neuroglycopenic symptoms in these patients (3). Although insulinoma is mostly observed sporadically, approximately 5% of the cases are observed with syndromes (3).

The first insulinoma case in TSC patients was reported in 1959 (4). After that total of 9 cases diagnosed with insulinoma in patients with TSC have been reported (4-12). According to our knowledge, we presented the 10th TSC patient diagnosed with insulinoma in the literature.

CASE REPORT

Thirty-two years old male patient was referred to our outpatient clinic from the nephrology clinic. He had a seizure starting at the age of 1, and his seizures were controlled with antiepileptic treatment. Nodular pathological signals in the frontal-occipital regions, right caudate nucleus, and both ventricles were detected in the brain MRI taken due to the history of seizures at the age of 27. The lesion in the upper pole of the left kidney was detected in abdominal CT screening at the age of 27. The partial nephrectomy was performed, and the pathology result was found angiomyolipoma. Our patient was diagnosed with TSC at the age of 27 due to typical skin findings, renal angiomyolipoma, a history of infantile seizures, and cranial involvement. The patient received carbamazepine 300 mg and ramipril 5 mg. The patient’s mother also had TSC, and renal transplantation has been planned due to chronic kidney failure in his mother.

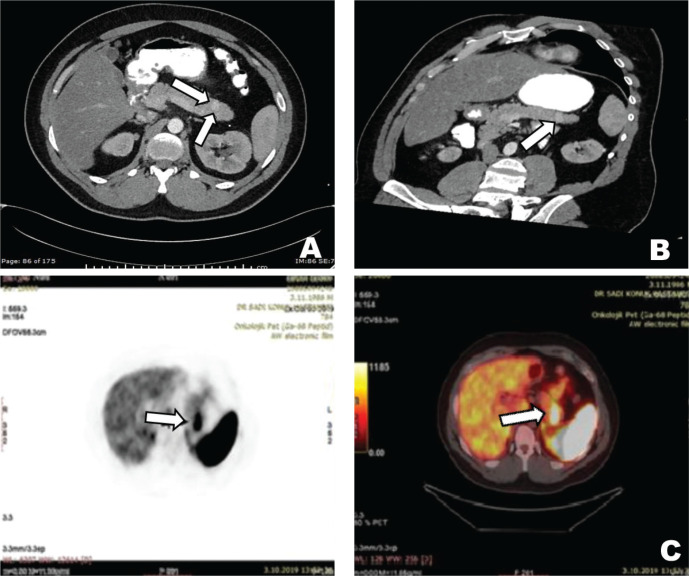

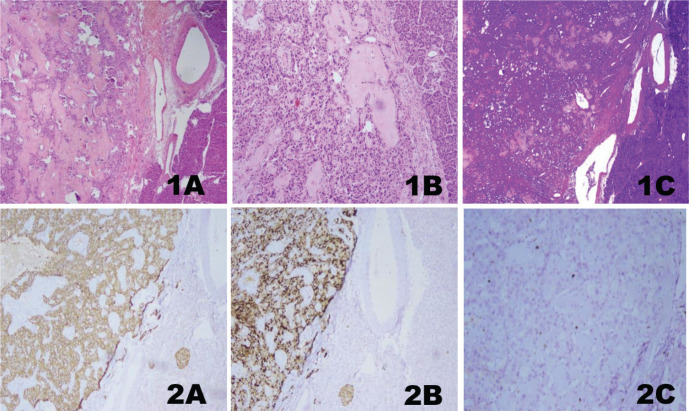

The main symptoms of the patient at admission were palpitations, diaphoresis, confusion, and these symptoms were improved with consuming sugary foods. The symptoms started about one year ago and have increased gradually during the last four months. The patient woke up nearly every night to consume sugary food and kept some sugary food with him wherever he went, especially during the last four months. There was no history of newly developed syncope or seizure. In the physical examination, the patient’s height was 168 cm, and the patient’s weight was 78 kg. He had angiofibromas on the face, trunk, and neck. His blood pressure and the other systems’ examination were normal. In laboratory examination, fasting glucose level was found to be 64 mg/dL and insulin level at 34 µIU/mL; other laboratory parameters were within normal limits (Table 1). Seventy-two hours fasting test was performed on the patient due to the symptoms of hypoglycemia. When the patient developed symptomatic hypoglycemia at the 8th hour of the test, a low glucose level at 41 mg/dL, a high insülin level at 21.65 µIU/mL, and a high C-peptide level at 7.04 ng/mL were found. The urine sulfonylurea screen test was negative. A lesion with a 12x7 mm size in the pancreatic tail and multiple lesions with fat densities in both kidneys were detected in the abdominal CT (Fig. 1). Increased uptake of Ga-68 DOTATATE (SUV max: 22.7) in the pancreatic tail was detected in Ga-68 PET-CT (gallium-68 positron emission tomography-computed tomography) (Fig. 1). The patient was diagnosed with insulinoma with clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings. As a result, the patient underwent a distal pancreatectomy. In pathological evaluation, there was no lymphovascular invasion, the mitotic rate was 1/10 at a high power field, and the Ki-67 index was low (%1). Chromogranin A and synaptophysin staining were positive, while vimentin and CD10 staining were negative. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed a low-grade tumor of NETs consistent with an insulinoma (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, insulin staining was not routinely available at our institution, so it was not performed. The patient’s symptoms improved postoperatively. The follow-up of the patient in our clinic is ongoing during the 2-year period after the operation, and the symptoms of hypoglycemia were not observed in our patient.

Table 1.

Laboratory results of the patient

| Result | Reference Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 63 | 74-106 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.8 | 0.7-1.2 mg/dL |

| ALT | 28 | 10-36 U/L |

| Albumin | 4.1 | 3.5-5.2 g/dL |

| Sodium | 142 | 136-145 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 5.08 | 3.5-5.1 mmol/L |

| Calcium | 9.7 | 8.6-10.2 mg/dL |

| HGB | 14 | 12.9-15.9 g/dL |

| HCT | 40 | 39-49 % |

| Free T4 | 1.31 | 0.93-1.7 ng/dl |

| TSH | 1.69 | 0.27-4.2 µıU/mL |

| Cortisol | 14 | 5-25 µg/dL |

| IGF-1 | 243 | 94-210 ng/ml |

| Insulin | 34.8 | 1.9-23 µIU/mL |

| 8th hour of the72 hours fasting test | ||

| Glucose | 41 | 74-106 mg/dL |

| Insulin | 21. 6 | 1.9-23 µIU/mL |

| C-peptide | 7.04 | 0.9-7.1 ng/mL |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HGB, hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; IGF-1, Insulin-like growth factor-1.

Figure 1.

12x7 mm hypervascular solid lesion with increased enhancement in the tail of the pancreas in axial CT images (A), hypervascular solid lesion in the tail of the pancreas in arterial phase multiplanar reformation CT images (B), and focal increased Ga-68 DOTATATE uptake in the tail of the pancreas (suvMAX: 22.78) (C).

Figure 2.

Histological hematoxylin-eosin stained features of the pancreatic tissue H&E;x40 (1A), histological hematoxylin-eosin stained features of the pancreatic tissue H&E;x100 (1B), acellular eosinophilic areas and amyloid deposits (1C), immunohistochemical evaluation of diffuse positive synaptophysin (2A), immunohistochemical evaluation of diffuse positive chromogranin (2B), and immunohistochemical evaluation of Ki-67 proliferation index (1%) (2C).

DISCUSSION

We present a case of insulinoma detected in a patient followed up with TSC. Our patient was a 10th TSC patient diagnosed with insulinoma, according to our knowledge. Although the incidence of NETs is higher in patients with TSC than in the general population, current guidelines for TSC do not include standard investigations for screening for NETs, including pituitary, parathyroid, gastroenteropancreatic, and adrenomedullary NETs (2, 13). 10% of the pancreatic NETs are associated with syndromes such as MEN1 syndrome and von Hippel Lindau syndrome, and less commonly, neurofibromatosis type 1 and TSC (14). In the literature, insulinoma was diagnosed in 9 patients followed up with TSC. The mean age of these patients was 35 (range, 18 years to 67 years), and the mean tumor diameter was 4.7 cm (range, 7 mm to 21 cm) (4-12).

Insulinomas are very rare pancreatic NETs. In the Mayo clinical series of 237 insulinoma patients, the mean age at diagnosis was 50 years (range 17 to 86 years), 6 % of the insulinomas (14 patients) had MEN1 syndrome, and approximately 10% of the cases were multiple (3). In TSC patients with insulinoma, the mean age at diagnosis was younger than the sporadic cases, and one case had multiple tumors (3-12). The common manifestations of insulinoma are fasting hypoglycemia, and the episodes of neuroglycopenic and autonomic symptoms of hypoglycemia are commonly observed in these patients (4-12). In nearly all TSC patients, as in our patient, neuropsychiatric abnormalities such as epilepsy are one of the main disease manifestations, and these symptoms may be confused with the clinical manifestations of hypoglycemia in insulinoma (4-12). Surgical resection is the treatment for insulinomas and offers the chance of a cure. All TSC patients with insulinoma underwent surgery, and, as in our case, the symptoms of insulinoma improved postoperatively (4-12).

TSC is an autosomal dominant genetic disease that is caused by a mutation in either the TSC1 gene or the TSC2 gene (1, 2). These genes encode hamartin and tuberin proteins, and the hamartin-tuberin complex inhibits the activity of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). When the mutation develops, mTOR is constantly activated, and as a result, cell metabolism, growth, and proliferation are altered in a large number of tissues (1, 2). TSC is characterized by the development of multiple hamartomas in many organ systems. Therefore, the clinical expression of the disease is highly variable (2). Our patient had dermatological findings, neurocognitive disorders, and renal and cranial lesions. The mTOR pathway was shown to be associated with increased insulin synthesis and pancreatic cell mass (15, 16). Some studies suggest that refractory or metastatic insulinoma cases may respond to treatment with an inhibitor of mTOR with an effect on insulin secretion and apoptosis (17, 18). Shigeyama et al. showed that hyperinsulinemia and hypoglycemia with increased pancreatic beta cells were observed in mice deficient in the TSC2 gene (16). Therefore, in the presence of these data, mTOR activation due to TSC1 and TSC2 gene mutations also observed in the pathogenesis of TSC may be associated with the existence of insulinoma in patients with TSC (10, 16). The mutation in the TSC2 gene was also found in our patient.

In conclusion, current guidelines for TSC do not include standard investigation for insulinomas. Since neuropsychiatric abnormalities were one of the main disease symptoms in the patient with TSC may be confused with the clinical manifestations of insulinoma. Therefore, TSC patients with newly developed neurological symptoms and behavioral defects should be evaluated in terms of insulinoma. In addition, clarifying the common pathogenesis of insulinoma and TSC in these patients would be crucial in the management of patients with insulinoma who could not undergo surgery.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Osborne JP, Fryer A, Webb D. Epidemiology of tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:125–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krueger DA, Northrup H, International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus G Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Placzkowski KA, Vella A, Thompson GB, Grant CS, Reading CC, Charboneau JW, Andrews JC, Lloyd RV, Service FJ. Secular trends in the presentation and management of functioning insulinoma at the Mayo Clinic, 1987-2007. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1069–1073. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutman A, Leffkowitz M. Tuberous sclerosis associated with spontaneous hypoglycaemia. Br Med J. 1959;2:1065–1068. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5159.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davoren PM, Epstein MT. Insulinoma complicating tuberous sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:1209. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.12.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H, Kerr A, Morehouse H. The association between tuberous sclerosis and insulinoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1543–1544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boubaddi NE, Imbert Y, Tissot B, Chapus JJ, Dupont E, Gallouin D, Masson B, De Mascarel A. Insulinome sécrétant et sclérose tubéreuse de Bourneville [Secreting insulinoma and Bourneville’s tuberous sclerosis] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1997;21:343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Berre JP, Bey Boeglin M, Duverger V, Garcia C, Bordier L, Dupuy O, Mayaudon H, Bauduceau B. Crise comitiale et sclérose tubéreuse de Bourneville: penser à l’insulinome [Seizure and Bourneville tuberous sclerosis: think about insulinoma] Rev Med Interne. 2009;30:179–180. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eledrisi MS, Stuart CA, Alshanti M. Insulinoma in a patient with tuberous sclerosis: is there an association? Endocr Pract. 2002;8:109–112. doi: 10.4158/EP.8.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang MY, Yeoh J, Pondicherry A, Rahman H, Dissanayake A. Insulinoma and Tuberous Sclerosis: A Possible Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Pathway Abnormality? J Endocr Soc. 2017;1:1120–1123. doi: 10.1210/js.2017-00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comninos AN, Yang L, Abbara A, Dhillo WS, Bassett JHD, Todd JF. Frequent falls and confusion: recurrent hypoglycemia in a patient with tuberous sclerosis complex. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6:904–909. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Qahtani MS, Bojal SA, Alqarzaie AA, Alqahtani AA. Insulinoma in tuberous sclerosis: An entity not to be missed. Saudi Med J. 2021;42:332–337. doi: 10.15537/smj.2021.42.3.20200490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworakowska D, Grossman AB. Are neuroendocrine tumours a feature of tuberous sclerosis? A systematic review. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:45–58. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, Chan JA, Dillon JS, Heaney AP, Kunz PL, O’Dorisio TM, Salem R, Segelov E, Howe JR, Pommier RF, Brendtro K, Bashir MA, Singh S, Soulen MC, Tang L, Zacks JS, Yao JC, Bergsland EK. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Consensus Guidelines for Surveillance and Medical Management of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas. 2020;49:863–881. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhan HX, Cong L, Zhao YP, Zhang TP, Chen G, Zhou L, Guo JC. Activated mTOR/P70S6K signaling pathway is involved in insulinoma tumorigenesis. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:972–980. doi: 10.1002/jso.23176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shigeyama Y, Kobayashi T, Kido Y, Hashimoto N, Asahara S, Matsuda T, Takeda A, Inoue T, Shibutani Y, Koyanagi M, Uchida T, Inoue M, Hino O, Kasuga M, Noda T. Biphasic response of pancreatic beta-cell mass to ablation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2971–2979. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01695-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard V, Lombard-Bohas C, Taquet MC, Caroli-Bosc FX, Ruszniewski P, Niccoli P, Guimbaud R, Chougnet CN, Goichot B, Rohmer V, Borson-Chazot F, Baudin E, French Group of Endocrine Tumors Efficacy of everolimus in patients with metastatic insulinoma and refractory hypoglycemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:665–674. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulke MH, Bergsland EK, Yao JC. Glycemic control in patients with insulinoma treated with everolimus. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):195–197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0806740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]