Abstract

Background

To examine the impact of the lockdown period of the pandemic on COVID-19 phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in migraine patients.

Methods

A total of 73 patients, including 39 migraine and 34 controls, completed the study during the lockdown period. The patients were evaluated using the Structured Headache Questionnaire, PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) (PCL-5) and COVID-19 Phobia Scale via the telephone-based telemedicine method.

Results

Migraine patients had significantly lower scores in all subgroups of the COVID-19 Phobia Scale (mean = 42.33 ± 12.67) than those in the healthy control group (mean = 52.88 ± 13.18). PCL-5 scale scores in migraine patients were significantly lower (mean = 27.18 ± 14.34) compared to the healthy controls (Mean = 34.03 ± 14.36). Migraine attack frequency decreased or did not change in 67% of the patients during the lockdown period.

Conclusion

Acute stress response to an extraordinary situation such as a pandemic may be more controlled in migraine patients, yet specific phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder have been reported more frequently in patients with migraine under normal living conditions. We interpreted that the life-long headache-associated stress may generate a tendency to resilience and resistance to extraordinary traumatic events in migraine patients.

Keywords: COVID-19, Migraine, Phobia, PTSD

Background

Migraine is a complex neuro-vasculo-inflammatory disorder and the third most common disease in the world. Migraine is 2–3 times more frequent in women, with a prevalence rate of 21.1% [1, 2]. Genetic and environmental mechanisms both play a complex role in the pathogenesis and attacks can be triggered by various factors including emotional stress, lifestyle changes, or dietary contents. Various studies evaluated the impact of nutrition, fluid consumption, sleep disturbances, lifestyle changes, and stress on migraine attacks. Skipping meals and fasting were frequently reported among the accepted ‘triggers’ of migraine headache attacks. In a study evaluating 1207 migraine patients with and without aura, it was found that fasting was a headache trigger in 57% of patients, stress, hormonal fluctuations (among women) and sleep disturbance were the most common migraine triggers [3]. Healthy lifestyle choices including regular sleep, stress management, and regular eating can prevent attacks and the transformation of chronic migraine over time [4].

On the other hand, exposure to extreme stress, even if emotional, can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [5]. PTSD is a chronic clinical syndrome resulting from exposure to traumatic events that involve a perceived threat to life or physical health. Its symptoms include 3 main elements and must be present over a period of at least 1 month: (1) re-experience of traumatic events, (2) persistent avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, and emotional dullness (3) increasing symptoms of physiological arousal [6]. Although there is a similar frequency of exposure to trauma among groups, PTSD is observed more common in migraine patients compared to the general population (14–25% versus 1–12%) and more common in patients with chronic migraine than episodic migraine patients (43% vs 9%) [7].

In addition, community studies established an association between migraine and specific phobia such as agoraphobia or zoophobia [8]. In a study by Korkmaz et al. the comparison of the migraine patient and control groups based on SCL-90-R findings demonstrated that the phobia scores of migraine patients (0.64 ± 0.75) were higher than that of controls (0.24 ± 0.29) [9].

COVID-19 has still been the most life-threatening pandemic of the century and with a global huge impact. According to data from the world health organization, more than 165 million cases have been reported in 214 countries with almost 3.5 million deaths [10].

Headache, with some distinctive features is one of the early manifestations of COVID-19 and may appear as an isolated symptom in some patients [11–13]. It seems that the SARS CoV-2 virus can not only cause systemic infection and neurological symptoms, but also induce psychological symptoms of fear, anxiety, and phobia in the community.

The first COVID-19 case in Turkey was detected in March 2020. To reduce the risk of contamination and ensure isolation of the public, a period of lockdown was applied with strict restrictions quite different from daily routine. During the lockdown period, fear of the COVID-19 disease, uncertainties, and future anxieties were the major stress factors for people. On the other hand, patients had to counteract factors such as more regular daily life, less work-related stress due to a flexible working schedule and the presence of health policy assuring drug availability without renewal of prescription. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the impact of the lockdown period on COVID-19 phobia and PTSD scales and the frequency of attacks in migraine patients.

The lockdown period contained some regulations, such as a flexible working schedule, reduced capacity of outpatient clinics, and admissions of only emergencies to hospitals. Therefore, telemedicine applications have also become an important tool to reduce complication and recurrence rates, particularly for chronic diseases. Telemedicine means providing healthcare services using information communication technologies regardless of distance. Applications can be video conferencing, e-mail, web-based, or telephone-based. Especially teleconsultations are widely applied with potential benefits of improved access to information, care delivery, professional education, and reduced health care costs [14, 15].

Methods

This study conducted during the first lockdown period in 2020. Ethical approval was obtained from both Ministry of Health Ethical Committee and Local Ethical Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. None of the patients, healthy controls or their households had COVID-19 diagnosis.

Subjects

All patients with migraine diagnosis (ICDH 1.1, 1.3) who were admitted to the Department of Neurology Algology Headache Outpatient Clinic for the last 6 months were evaluated by telemedicine method by two headache experts during the COVID-19 lockdown period.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with migraine without aura and chronic migraine according to the ICHD-3 criteria and healthy controls who did not have any neuro-psychiatric comorbid diseases or health disorders, in general, were included in the study. 18–65 years old female migraine patients or subjects were included due to the high prevalence of migraine in women [16, 17].

Exclusion criteria

Migraine patients who were less than 18-year-old, more than 65 years old, and who had headaches other than migraine were excluded. In the control group, patients with a history of psychiatric illness and who had any headaches were excluded. All patients who had COVID-19 disease during the study period or did not complete surveys were excluded.

Among 78 patients diagnosed with migraine and controls, 73 patients were enrolled in the present study. Patients who did not complete questionnaire (n = 3) and patients who did not deliver written inform consent (n = 2) were excluded from the study.

Study period and design of a telemedicine-based questionnaire

The present study was conducted during the first lockdown period in March 16–June 1, 2020, in Turkey. Since outpatient clinics were closed except for emergencies due to the COVID-19 pandemic, phone interview was completed by headache specialists using a questionnaire. The questionnaire included questions about demographic characteristics and migraine attacks, the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) and the COVID-19 Phobia scale for which Turkish validity and reliability studies were conducted [18]. The COVID-19 Phobia scale consisted of 20 questions in which Psychological, Psychosomatic, Economic and Social factors are evaluated. Physiological factors measure an individual's or relative's anxiety about getting COVID-19. The economic factors subscale assesses COVID-19 disease's anxiety about running out of cleaning equipment and food and stocking. The psychosomatic factors subscale assesses somatic symptoms caused by anxiety for COVID-19. The social factors subscale evaluates how much individuals avoid social relationships due to COVID-19 [18]. All items in the scale are rated on a 5-point scale between ‘strongly disagree’ [1] and ‘strongly agree [5]’. Scores on the scale can range from 20 to 100, and a higher score indicates a greater phobia in the counted subscales and total scale [19].

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluations were made using the SPSS 21.0 IBM package program. In all evaluations, parametric tests were used in the analysis of the data, as they showed normal distribution in terms of dependent variables. The person conducting the analysis was blind to the groups. When the number of people in the new groups fell below 30, nonparametric analyzes were used. Descriptive analysis methods were used in the evaluation of sociodemographic data, and T-Test, Mann–Whitney U, and Kruskal–Wallis analysis methods were used when comparing group.

Results

Thirty-nine women with diagnosis of episodic migraine (79%) and chronic migraine (21%) completed the study. Demographic features were summarized in Table 1. Twenty-eight (71.7%) of 39 patients were followed up for more than 3 years with a diagnosis of migraine. Eleven (28.3%) patients were diagnosed in the last 3 years. Twenty-six (66.7%) of the patients did not have any comorbid disease. Four (10.3%) patients had hypertension (HT), 2 (5.3%) patients had diabetes mellitus (DM), 2 (5.3%) patients had asthma, 3 (7.7%) patients had hypothyroidism and the other 2 (5.3%) patients had both HT and DM.

Table 1.

Comparison of the groups in terms of COVID-19 phobia scale and PCL-5 scale scores

| Scales | Group | n | Mean | s | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-5 | Migraine patient | 39 | 27.18 | 14.34 | 69.64 | − 2.034* | 0.046 |

| Control | 34 | 34.03 | 14.36 | ||||

| Covid-19 phobia scale total score | Migraine patient | 39 | 42.33 | 12.67 | 68.81 | − 3.473** | 0.001 |

| Control | 34 | 52.88 | 13.18 | ||||

| Physiological factors | Migraine patient | 39 | 18.20 | 6.03 | 70.84 | − 2.593* | 0.012 |

| Control | 34 | 21.71 | 5.50 | ||||

| Psychosomatic factors | Migraine patient | 39 | 5.74 | 2.40 | 65.44 | − 2.039* | 0.046 |

| Control | 34 | 7 | 2.81 | ||||

| Economic factors | Migraine patient | 39 | 5.38 | 2.03 | 49.20 | − 3.498** | 0.001 |

| Control | 34 | 7.91 | 3.76 | ||||

| Social factors | Migraine patient | 39 | 13.18 | 5.31 | 69.63 | − 2.241* | 0.028 |

| Control | 34 | 15.97 | 5.31 |

*p < 0.05

**p < 0.01

Six out of 39 migraine patients were not receiving any prophylactic treatment. Thirty-three patients were using prophylactic treatment for migraine attacks: 14 beta-blockers (propranolol 40–80 mg /day or metoprolol 50 mg/day), 10 duloxetine (60 mg/day), 3 amitriptyline (10–25 mg/day) 6 topiramate (50–100 mg/day). Twenty-eight (85%) patients who received prophylactic treatment continued to use their medications regularly during lockdown period. Five (15%) patients stopped their medication completely during the lockdown. All patients were receiving analgesic, antiemetic or triptan during migraine attacks. Also, there was no significant alteration their sleep pattern (67%) or appetite (72%) was detected.

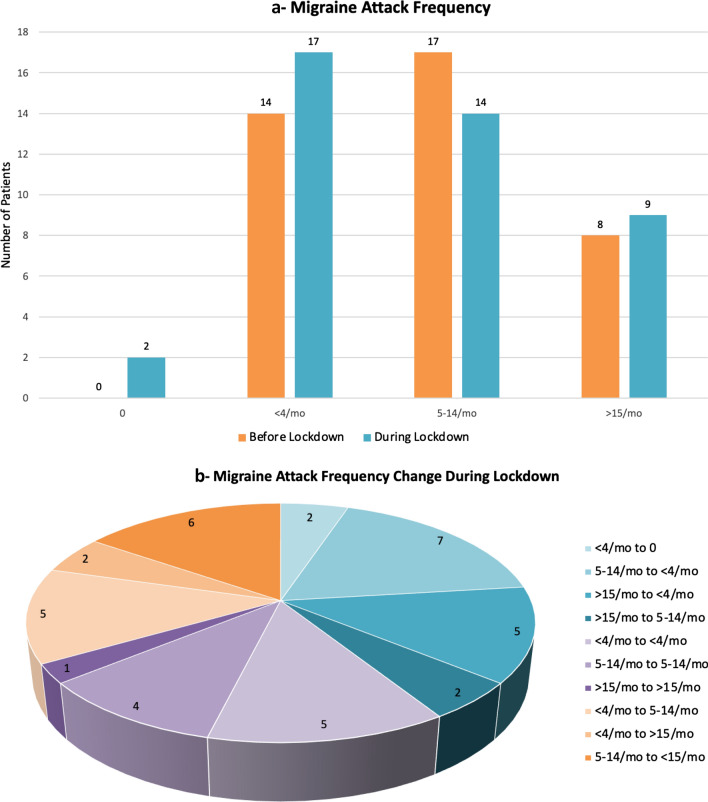

Migraine attack frequency were classified in 4 categories: none, < 4/month, 5–14/month and > 15/month. Migraine attack frequencies before and during lockdown period is given in Fig. 1a. Notably 2 patients had no attack during lockdown period. Migraine attacks were not increased in 26 patients (67%) patients. Migraine attack frequency change in each patient is given in Fig. 1b. Migraine attack frequency decreased in 16 (41%) of 39 patients during lockdown period. There was no change in the frequency of headache attacks in 10 (25.7%) patients. Increase in the frequency of migraine attacks was observed in only 13 (33.3%) patients (Fig. 1b—Migraine Attack Frequency). Nine out of the 13 patients whose attack frequency increased during the lockdown did not changed their headache treatment, but 3 out of 13 patient discontinued preventive treatment. Other 1 (7.7%) patient was already not on prophylactic treatment.

Fig. 1.

a Migraine attack frequency. b Migraine attack frequency change during lockdown

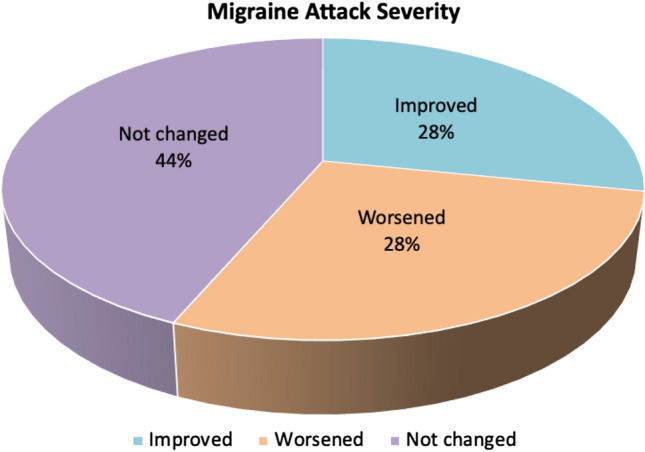

Migraine attack severity decreased in 11 (28%) of 39 patients during this period. Migraine attack severity had not change in 17 (44%) patients. Worsening of the pain attack severity was observed in 11 (28%) patients (Fig. 2—Migraine Attack Severity).

Fig. 2.

Migraine attack severity

The number of analgesics and/or triptans used for abortive migraine medication was decreased in 15 (38.5%) of 39 patients. On the other hand, the number of analgesics used was increased in 15 (38.5%) patients, in whom 13 of these patients had increased frequency of migraine attacks and other had arthralgia.

The groups that make up the sample were compared in terms of applied PCL-5, Covid-19 Phobia Scale total and subscale scores, and the results are shown in Table 1. Significant differences were found between groups in PCL-5 (t = − 2.034, p < 0.05), Covid-19 Phobia Scale (t = − 3.473, p < 0.01), Physiological Factors subscale (t = − 2.593, p < 0.05), Psychosomatic Factors subscale (t = − 2.039, p < 0.05), Economic Factors subscale (t = − 3.498, p < 0.01), and Social Factors subscale (t = − 2.241, p < 0.05) scores. Migraine patients (Mean = 27.18 ± 14.34) received significantly lower PCL-5 scale scores than those in the healthy control group (Mean = 34.03 ± 14.36). Similarly, migraine patients (Mean = 42.33 ± 12.67) had significantly lower Covid-19 Phobia Scale scores than those in the healthy control group (Mean = 52.88 ± 13.18). Again, migraine patients (Mean = 18.20 ± 6.03) had significantly lower Physiological Factors subtest scores than those in the healthy control group (Mean = 21.71 ± 5.50). Migraine patients (Mean = 5.74 ± 2.40) had significantly lower Psychosomatic Factors subtest scores than healthy control group (Mean = 7 ± 2.81). Migraine patients (Mean = 5.38 ± 2.03) had significantly lower Economic Factors subtest scores than the healthy control group (Mean = 7.91 ± 3.76). Likewise, migraine patients (Mean = 13.18 ± 5.31) had significantly lower Social Factors subtest scores compared to healthy control group (Mean = 15.97 ± 5.31).

COVID-19 phobia scale and PCL-5 scale scores were statistically indifferent among 3 groups of migraine patients in whom attack frequency was increased, decreased or unchanged. In terms of applied COVID-19 phobia and PCL-5 scale scores, migraine patients using duloxetine or amitriptyline were compared with those who did not use. There was no significant difference between these two groups in terms of any applied scale scores (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antidepressant use on PCL-5 and COVID-19 phobia scale

| Scales | Antidepressant use (SNRI and/or TCA) | n | Mean | Mean Total | u | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-5 | Yes | 13 | 19.27 | 250.5 | 159.5 | 0.780 |

| No | 26 | 20.37 | 529.5 | |||

| Covid-19 phobia scale total score | Yes | 13 | 19 | 247 | 156 | 0.713 |

| No | 26 | 20.50 | 533 | |||

| Physiological factors | Yes | 13 | 19.85 | 258 | 167 | 0.965 |

| No | 26 | 20.08 | 522 | |||

| Psychosomatic factors | Yes | 13 | 17.62 | 229 | 138 | 0.368 |

| No | 26 | 21.19 | 551 | |||

| Economic factors | Yes | 13 | 19.35 | 251.5 | 160.5 | 0.803 |

| No | 26 | 20.33 | 528.5 | |||

| Social factors | Yes | 13 | 16.88 | 219.5 | 128.5 | 0.231 |

| No | 26 | 21.56 | 560.5 |

Discussion

This is the first study that evaluated COVID-19 phobia in migraine patients during the lockdown period of the pandemic. We found significantly lower COVID-19 phobia scores in migraine patients compared to the healthy controls. In accordance with the total test score, all subgroup scores of the COVID-19 phobia scale were lower in patients with migraine. Reduced PTSD PCL-5 scale scores in migraine patients were consistent with COVID-19 phobia results. In parallel to these data, migraine attack frequency was found to be decreased or not changed in 67% of the patients during the lockdown period. We interpreted the data that acute stress response in migraine patients to an extraordinary condition during the COVID-19 pandemic may not be as exaggerated as healthy controls.

Psychiatric comorbidities including anxiety and mood disorders were reported in 23.1% of patients with migraine headache [23] and lifetime social phobia frequency was found in 4% of migraine patients [23]. Specific phobia was higher in patients with migraine headaches than in the control group [9]. However, we found that specific COVID-19 phobia was unexpectedly lower during the alarming, extraordinary conditions of the lockdown period. It was also notable that the physiological, psychosomatic, economic, and social subscales of the COVID-19 phobia test were also significantly different in migraine patients.

COVID-19 phobia scale, applied to the migraine patients for the first time detected lower scores than the control group. Though specific phobia and post-traumatic stress disorder have been reported more frequently in patients with migraine under normal living conditions, we suggest that migraine headache patients might be more resilient to unpredicted, panicking events.

Regarding the treatment, 13 migraine patients were taking duloxetine or amitriptyline. The latter two drugs have been given at a low dose to benefit from their sedative effect, and the antidepressant efficacy was not expected at this lowest dose. Still, we evaluated whether the lower scores in migraine patients were related to the antidepressants used for migraine prevention. Yet, phobia and PCL-5 scale scores were not different between migraine patients using duloxetine or amitriptyline and those patients without these drugs. This finding showed that COVID-19 phobia was not related to antidepressant use in the present study. In addition, the application of all these questionnaires by two headache professionals and the correlation between PTSD and COVID-19 phobia scale scores increase the reliability of the study results.

Studies on stress adaptation in migraine patients are limited, yet perceived stress was reported to be higher in migraine patients with an increased frequency of attacks [24]. No significant difference was found in the ‘Upset because of something that happened unexpectedly’ subgroup in the perceived stress scale when patients with migraine were compared with the control group, while other subgroup scores were significantly higher in migraineurs [24]. These results are in line with our data and support that the reaction to extraordinary, unexpected, and alarming stress could be different in migraine patients. It may also imply that migraine patients can be resistant to stress in extraordinary circumstances.

Reaction to lockdown stress during a pandemic has not been reported in adults, yet two studies evaluated stress response and anxiety symptoms during COVID-19 to the lockdown period, in children and adolescents with migraine. The frequency of migraine attacks and anxiety symptoms was found to be decreased or not changed in most patients during the lockdown period. It was related to reduced environmental challenges and stress [21]. In a multicenter study in children aged 5–18 years, pain characteristics and COVID-19 anxiety, general anxiety, and depression were evaluated in patients with migraine with or without aura and tension-type headache [21]. Headache frequency and severity of attacks were reduced, and the authors emphasized that reduced school effort and anxiety were the most important factors to explain headache improvement [21]. Likewise, it has been established that lifestyle change is the main factor affecting headache [22].

During the lockdown period in our country, strict quarantine rules were applied, and many places have a high risk of contamination such as schools, shopping malls, cafes, restaurants, hotels, hairdressers, and beauty salons were suspended. Curfew restrictions were imposed especially on weekends and some public holidays. As a result of all these measures, the great majority of the people in the country had to spend most of the day at home. Also, many people limited their social activities and relationships due to contagion concerns.

Conventional hospital services were the most affected area. Admission to hospitals decreased significantly due to the limitation of an outpatient clinic in most hospitals and the patients seeing the hospital as a dirty area. In this environment where face-to-face meetings could not be as comfortable as they used to be, telemedicine applications became a new communication method for the medical field. Our patients were called from the phone numbers registered in the system. Their current clinical status was noted, the patients were advised, and the treatment was arranged for those with increased migraine frequency. Our patients welcomed our calls. They were informed about the study and tests were applied.

As an important trigger for migraine, we can see the impact of stress and lifestyle changes on the migraine attack frequency. Work stress, insomnia, some food and drinks and lighting systems increase attacks in patients with migraine [20]. In our patients, decrease in work stress and intensity, less exposure to external stressor factors (factors such as shopping mall lights, crowded environment, noise), more regular and healthy meals (homemade food, reduced fast food consumption, less skipping meals) attention to water consumption might be important modulating factors on migraine attacks.

Migraine attack frequency was reduced or not changed in 67% of the patients. In parallel, analgesic intake was significantly lower in 38% and not changed in 23% of migraine patients. Therefore, we think that reduced stress and relaxing factors such as regular living, and flexible working schedules played a role in these patients. No new treatment was prescribed for any of the patients, and the majority continued their current treatment. A new easy prescription policy that abortive and preventive medications were delivered to the patients without visiting the hospital could contribute to that result. On the other hand, increased attack frequency was detected in 33% of migraine patients in whom the stressors were more prominent.

Health care facilities/health coverage is free for citizens in Turkey. During the lockdown period, all COVID-19 patients had free access to hospitals and even private hospitals provided treatment without any charge. In addition, economic support has been given to the unemployed, and rent payments were delayed by the government. Our subjects in the study group continued to get their basic monthly salary during the lockdown period. All of these have been effective in alleviating some economic concerns.

The relatively late entry of COVID-19 into our country provided a valuable short time to take measures for preparation and informing the community compared to countries that encountered the virus earlier. In addition to the later emergence of the pandemic, a lower total number of COVID-19 infections and particularly deaths in Turkey [25] could take part in the low phobia associated with COVID-19. Therefore, the public might show less panic reaction and anxiety. Nonetheless, these factors were inadequate to explain why migraine patients had lower PTSD and phobia scores than healthy controls.

The COVID-19 pandemic and social isolation had a positive impact on the attack frequency and severity in our migraine patients who were trying to adapt to the new world regulations. The attack frequency did not increase in most of the patients. As a result of the factors such as being isolated in a safe home environment, having healthy and regular nutrition, and decreased stress related to work and socialization, the frequency and severity of attacks decreased in patients, and consequently, the use of analgesics was reduced.

COVID-19 phobia was evaluated for the first time in migraine patients along with the PCL-5 scale during the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Another strength of the study is that two headache experts completed the phone interview with migraine patients. Also, enrolled patients were previously registered in our headache clinic and their clinical features were well known.

One of the limitations of the study is that the sample size of the study was not sufficient for subgroup analysis. The socioeconomic status, lifestyle, and environmental factors were not similar in migraine patients during the lockdown period. The duration was not adequate to obtain follow-up data. Considering the country-specific differences in economic, and sociocultural dynamics, and management of the pandemic, COVID-19 phobia results of migraine patients could be unique in this study and cannot be generalized globally.

Conclusion

We reported for the first time that COVID-19 phobia was lower in migraine patients compared to healthy controls during the lockdown. PTSD test results supported COVID-19 phobia data in migraine patients. Also, reduced migraine attack frequency, headache severity, and use of abortive medication were in line with COVID-19 phobia scores. We believe the reaction to unexpected and alarming stress due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic may be more controlled in migraine patients, suggesting that migraine patients can be resilient to stress in extraordinary situations. The results of this study emphasize that improving triggers such as stress, sleep, and meals are effective in controlling migraine attacks even in an extraordinary situation such as the lockdown period of the pandemic. We interpreted that the life-long headache-associated stress may generate a tendency to resilience and resistance to extraordinary traumatic events in migraine patients. The latter such an intriguing possibility needs to be investigated by further clinical studies.

Author contributions

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from [third party name] but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of [third party name].

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/ or publication of this article.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Gazi University Medicine Faculty Ethics Committee. All participants signed the informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Çile Aktan, Email: drcilezengin@hotmail.com.

Tuğçe Toptan, Email: tugcetoptan@hotmail.com.

Çisem Utku, Email: cisemutku@gmail.com.

Hayrunnisa Bolay, Email: hbolay@gazi.edu.tr.

References

- 1.Yeh WZ, Blizzard L, Taylor BV. What is the actual prevalence of migraine? Brain Behav. 2018;8(6):e00950. doi: 10.1002/brb3.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozdemir G, Aygül R, Demir R, et al. Migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic properties in the eastern region of Tresurkey: a population-based door-to-door survey. Turk J Med Sci. 2014;44(4):624–629. doi: 10.3906/sag-1307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner DP, Smitherman TA, Penzien DB, et al. Nighttime snacking, stress, and migraine activity. J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21(4):638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmura MJ. Triggers, protectors, and predictors in episodic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22(12):81. doi: 10.1007/s11916-018-0734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yehuda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):108–14. doi: 10.1056/NJEMra012941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ertuğrul K (ed) American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC

- 7.Peterlin BL, Tietjen G, Meng S, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in episodic and chronic migraine. Headache. 2008;48(4):517–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merikangas KR, Angst J, Isler H. Migraine and psychopathology. Results of the Zurich cohort study of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(9):849–853. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810210057008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korkmaz S, Kazgan A, Korucu T, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in migraine patients and their attitudes towards psychological support on stigmatization. J Clin Neurosci. 2019;62:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed 17 June 2021

- 11.Bolay H, Gül A, Baykan B. COVID-19 is a real headache! Headache. 2020;60(7):1415–1421. doi: 10.1111/head.13856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uygun Ö, Ertaş M, Ekizoğlu E, et al. Headache characteristics in COVID-19 pandemic-a survey study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01188-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toptan T, Aktan Ç, Başarı A, et al. Case series of headache characteristics in COVID-19: headache can be an isolated symptom. Headache. 2020;60(8):1788–1792. doi: 10.1111/head.13940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mars M, Scott R. Telemedicine service use: a new metric. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e178. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong Z, Li N, Li D, et al. Telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences from Western China. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(5):e19577. doi: 10.2196/19577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolay H, Ozge A, Saginc P, et al. Gender influences headache characteristics with increasing age in migraine patients. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(9):792–800. doi: 10.1177/0333102414559735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavlovic JM, Akcali D, Bolay H, et al. Sex-related influences in migraine. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95(1–2):587–593. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boysan M, Özdemir PG, Özdemir O, Selvi Y, Yılmaz E, Kaya N. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (PCL-5) Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(3):306–316. doi: 10.1080/24750573.2017.1342769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arpaci I, Karataş K, Baloğlu M. The development and initial tests for the psychometric properties of the COVID-19 phobia scale (C19P-S) Pers Individ Dif. 2020;164:110108. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann J, Recober A. Migraine and triggers: post hoc ergo propter hoc? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17(10):370. doi: 10.1007/s11916-013-0370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dallavalle G, Pezzotti E, Provenzi L, et al. Migraine symptoms improvement during the COVID-19 lockdown in a cohort of children and adolescents. Front Neurol. 2020;11:579047. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.579047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papetti L, Loro PAD, Tarantino S, et al. I stay at home with headache. A survey to investigate how the lockdown for COVID-19 impacted on headache in Italian children. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(13):1459–1473. doi: 10.1177/0333102420965139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semiz M, Şentürk IA, Balaban H, et al. Prevalence of migraine and co-morbid psychiatric disorders among students of Cumhuriyet University. J Headache Pain. 2013;14(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An YC, Liang CS, Lee JT, et al. Effect of sex and adaptation on migraine frequency and perceived stress: a cross-cectional case-control study. Front Neurol. 2019;5(10):598. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) - statistics and research. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Accessed 17 June 2021

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from [third party name] but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of [third party name].