Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented suffering to the lives and livelihoods of indigenous people across the country, especially in the south-eastern parts of Bangladesh, but the situation has rarely reported by the mass media and academic literature. This study was an attempt to find out the impacts and vulnerabilities of COVID-19 on the indigenous Chakma community at Rangamati sadar (sub-district) of Rangamati (district) in the Chattogram Hill Tracts (CHT) area, Bangladesh. It also aimed to investigate how indigenous people respond to the pandemic and how they can develop resilience to adapt to the adverse situation. For conducting this study, a critical ethnographic approach was adopted, along with participant observation, in-depth interview, and focus group (FGs) for collecting data in the study area. The findings of the study indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic severely affects the traditional way of life, mythology, culture, food security, economic activities, and educational activities, along with increasing health risks for the people of the indigenous community. However, indigenous people respond to this pandemic in their own ways, involving their ancestors’ works, avoiding dependence on market systems, keeping faith in traditional medicines, building close relation to nature, along with following some health guidelines announced by government. This work refutes the existing mainstream discourse that indigenous people are unwittingly vulnerable and docile in their waiting for outside assistance.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Vulnerabilities, Indigenous community, Response, and Resilience

1. Introduction

More than 370 million indigenous people live in over 90 countries, constituting approximately 5% of the global total population. They have long been threatened in their way of life, culture, and religion by the many facades of colonialism and globalization, apart from facing severe impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2]. The recent outbreak of Novel Corona virus as a global crisis has exacerbated indigenous peoples' living conditions, as well as multiple vulnerabilities to their lives and livelihoods [3]; [2]. Moreover, because they live in remote areas with poor communication system, many indigenous people cannot receive support from the government or other organizations [4]. Indigenous people are a high-risk group for infection with COVID-19 due to their severe experience of discrimination, social exclusion, stigma, land dispossession, and a high prevalence of malnutrition [5,6].

All over the world, indigenous communities possess almost the same characteristics that contribute to their susceptibility to the COVID-19 pandemic. In comparison to the mainstreaming population, indigenous people have the highest rates of extreme poverty, morbidity, and mortality across the world's developing to developed countries [7]. These factors contribute to creating a vulnerable situation that makes indigenous people more at risk of death from COVID-19 [1,8,9].

In Bangladesh, more than 54 indigenous people live in different parts of the country, constituting about 1.8% of the total population [10]:3, [11]. Indigenous people in Bangladesh possess distinct culture, language, and heritage and mainly live in the hilly area of the south-eastern part of the country known as the Chattogram Hill Tracts (CHT) [12,13]. Throughout history, indigenous people have been deprived in terms of socio-economic development/indicators such as health, education, income, food consumption, women's empowerment, etc. They remain below the national average in these areas. Historically, indigenous people have largely depended on natural resources for their subsistence, but because of rising dispossession of land and resources triggered by conflict/exclusion and climate change, their lives and livelihoods have become extremely susceptible [[12], [13], [14]]. Moreover, these existing challenges for indigenous people have been exacerbated by the recent global crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

On March 26, 2020, the government announced a country-wide shutdown/lockdown to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and people in indigenous communities began to face food scarcity, as well as declining income opportunities, unemployment, scarcity of hygienic materials, and other daily necessities in their area [2,13]. The upshots of COVID-19 on indigenous people are colossal, and the direct results include mortality from severe illness, limited access to food, adjusting to local diets, and economic losses resulting from lockdown [2,5]. Considering all the traits, this paper sheds light on the impacts, and vulnerabilities of COVID-19 on indigenous people in the Chattogram Hill Tracts area. This paper also aims to explore the local responses of indigenous people to COVID-19 in the pandemic situation.

2. COVID-19 and indigenous people in global perspectives

Apart from other COVID-19-related issues in the recent world, the recent literature on the COVID-19 pandemic focuses primarily on the impacts and vulnerabilities of mainstream people. There is a research gap on how COVID-19 affects marginalized social groups, such as indigenous people in Bangladesh and around the world. They are a forgotten group, and their voices and situation are hidden in mainstream news reports and academic writing. To a certain extent, it reflects the phenomenon of social exclusion in Bangladesh and the rest of the world. Thus, this study aims to uncover the hidden voice and experience of indigenous people during the period of pandemic and lockdown situation. This study also reveals the responses, resilience, and coping strategies of these hidden marginal groups in Bangladesh.

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious virus that has recently caused a global crisis due to acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In December 2019, the virus was first detected in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province in China, and has since broken out across the world, stemming the ongoing Coronavirus 2019-20 pandemic [[6], [15]]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced the 2019–20 coronavirus outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020, and a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [16].

Despite the fact that sufficient vaccines were produced in developed countries, most governments followed a policy of confinement, shutdown, or lockdown to stop the virus's spread and relieve strain on health systems. This lockdown was unprecedented, as more than 4.5 billion people across the globe were confined and isolated in their home or residence in the early months of 2020 [15]. The effectiveness of lockdown is context-specific, as the diffusion of virus is tailored by population density, social mixing, attitudes of human beings, behaviors, and environmental factors, whereas the health effect is regulated by age, prevailing nutrition status, comorbidities, and health care capacity [17]. The curves of the coronavirus infections are thus diverse across countries and settings, and lockdown implementation is mostly dependent on the substantial socio-economic and health consequences of a particular country or territories, which could potentially raise a debate about the appropriateness and applicability of this strategy to control the spread of coronavirus in poor and middle-income countries in the world (LMICs) [[15], [16]].

Indigenous people are extremely vulnerable to COVID-19 for several reasons. Along with health conditions and the respiratory system increasing the risk of COVID-19 mortality, indigenous people rarely have proper access to hygienic materials such as soap, personal protective equipment (PPE), masks, sanitizers, medicines, clean water, and public sanitation in their community, which also trigger an increase in the infection rate [13,18].

In Latin America, due to the unfavorable environment and poor health situation, indigenous people envisage severe effects of COVID-19. Many indigenous people in this region are vulnerable, and being isolated from their community due to lockdown made them more fragile to cope with the new situation. Indigenous people living in slums do not have access to hygienic environment and live without basic water or sewage services. Many of the indigenous people are seen to adjust their traditional life system by altering their food and eating habits, resulting in changes their epidemiological profiles and their current exposure diversified diseases, i.e., high blood pressure, diabetes, gastric dysfunctions, cancer, etc. [[5], [9]].

Racism and exclusion toward ethnic people had intensified during the pandemic situation, especially in India, where people from the northeastern part of the country had been thrown out of their residential hotels and rented houses. They were forbidden from taking public transportation or purchasing food and other necessities from grocery stores. Many ethnic and lower-cast people, including women, had been exploited without cause, and many of them were living in the city with fear and anxiety. The outbreak of COVID-19 had made these people more vulnerable in that locality [19]. The situation of the pandemic was overwhelming in many low- and middle-income countries, as the government's actions to control it had turned to harshness from the police and security forces. During the lockdown/shutdown periods, hundreds of poor and destitute indigenous people were seen dying due to starvation, and those venturing out in misery were brutalized by the police and law enforcement authority [19].

However, though indigenous people experienced severe impacts and vulnerabilities of COVID-19 pandemic but many communities had responded the situation effectively by introducing community lockdowns, monitoring movements, doing quarantine to outsiders, and isolating suspected people notwithstanding having limitation of getting timely information and constraints of suitable resources and equipment. Despite there being fears and anxiety about the unknown virus among the indigenous community, they had responded to it in their own ways to overcome the vulnerability. People in indigenous communities not only received relief from different organizations but also worked hard on their land to produce crops to minimize food shortages. Many of the indigenous communities had successfully implemented their food production systems and managed the natural resources in their territory. These communities were not worried about food shortages as they worked collectively to improve their local food production and make sustainable resource management decisions (AIPP, 2020). Considering this trait, the current study aims to uncover the hidden voices and experience of indigenous people during the period of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

3. Methodology

We adopted critical ethnography as a methodology in this study. Critical ethnography based on critical social theory aims to critique and alter social structure ‘to emancipate well-beings from the miserable conditions that subjugated them’ [20]:244 cited in Ref. [21]. It always emphasizes a moral obligation to fight against social injustice, inequity, or oppression for marginalized groups or communities in society [22]; Thomas, 1993, cited in Ref. [23]. In critical ethnographical research, researcher focuses on challenging the unequal power relationship by researching the struggles of the weak and powerless against it, with the overall aim of uncovering social injustice and seeking to change society. This study followed the epistemology of critical social theory, in which it criticized social, political, and other structures to generate knowledge to foster a democratic society and liberate indigenous people from the adversity of the COVID-19 pandemic situation and their deprivation from mainstream society. Critical ethnography not only gives us a critical lens to understand the experience of the indigenous people from their perspective, but also gives us a reflexive lens to see sensitively our power relationship with our informants. As outside academic research, we clearly understood we have unequal subject position with local people. We learned to be humble and listen to local voices, respecting their own interpretation.

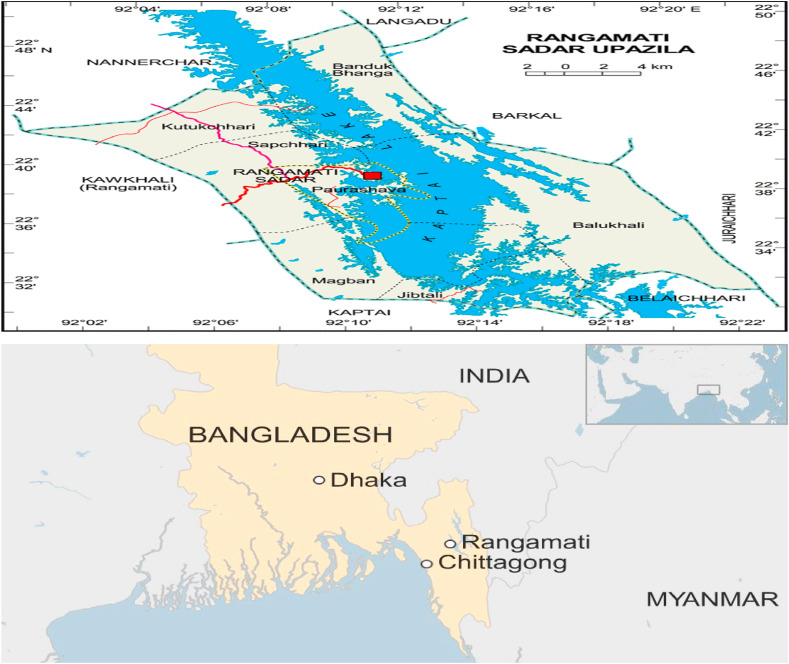

This study was carried out in Rangamati sadar (sub-district) of Rangamati (district) through several field visits from October 2019 to March 2020 and June 2020 to October 2020 (due to an outbreak of COVID-19, after March 2020, we used both online and field visit for data collection). The logic behind choosing this area as a study site was that it was one of the most vulnerable and COVID-19-affected areas among indigenous communities in the Chattogram Hill Track area. Moreover, as a mainstream researcher, this site was comparatively easy-going for communication and less challenging than a remote area. This project initially confined itself to focusing on the impact and vulnerability of climate change induced hazards on indigenous people, but when the novel coronavirus had spread across the world, including Bangladesh, this research extended its objectives and tried to focus on the impacts and vulnerabilities of COVID-19 on indigenous people and their responses to overcome them. Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Demonstrating the study sites at Kutukchhari and Sapchhari unions of Rangamati sadar (sub-district) of Rangamati (district) in Bangladesh.

Conducting ethnographic fieldwork is always challenging for the researcher, especially if the participants find the researcher belonging to a dominant society in the country. As researchers from outside and working in city in Bangladesh, we recognized that indigenous people were being excluded by the mainstream society. Due to this situation, we faced difficulties starting our fieldwork in the Chattogram Hill Tracts area. We had always wondered how the Chakma community members (who we wanted to interview) would react to us. Would they think that we had a desire to collect information for the purpose of exploiting them? Would they accept us as a trustworthy member for their community and share their suffering about the Bengali community to us? All these questions were always on our minds when we entered the indigenous community to conduct our ethnographic study. However, during the ethnographic fieldwork visit, we hardly encountered this difficulty because first author's student Amlan Chakma (of the Chakma community) was with us, who established rapport with the indigenous people and assisted us in becoming acquainted with this community. Then, indigenous people started to share their suffering from the environment as well as from the mainstream society. At first, they felt embarrassed to speak about the sufferings of the Bengali people, as the first author was a Bengali. But first author assured them that they could keep him in their beliefs and share everything that was happening to them. Moreover, having student Amlan Chakma with us gave them confidence that we would be trustworthy people with whom they could share their sufferings. First author also tried to convince them by uttering the fact that he also belonged to minority people like them (in terms of religion) in Bangladesh who was occasionally experienced exploitation from Bengali Muslim in the society. When they heard that the first author was Hindu in terms of religion, they expressed that their religion (Buddhism) was also very similar to his and thus, they felt a sense of integrity. By expressing identity in this way, we tried to be very close to the minds of indigenous people to obtain the authentic data of that community.

When the pandemic was at its peak, lockdown was imposed in CHT like other parts of the country and we paused our physical fieldwork following the restriction of COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, we had confined ourselves to the room and collected data online, as we had very limited access to the indigenous community. At the time, student Amlan Chakma (a local resident) was conducting fieldwork in the Chakma community, largely in accordance with WHO guidelines, and he was connected to me for data collection. He also connected me with respondents online (through his device) if there was an available network, and I collected information from the respondents. Otherwise, I collected information from my students after the field visit. We also provided masks and hand sanitizer to the respondents to curtail transmission during pandemic periods.

In this study, participant observation was employed as a tool for data collection. Through participant observation, we learned about the behavior and attitudes of participants in the Chakma community, that helped us find knowledgeable informants to collect data. We also understood the social order and the cultural norms of the Chakma community through participant observation [24]:179). Our participation in different events of the indigenous community helped to get a complete picture of the way of life of indigenous people, their behavior, the nature of vulnerability they faced in the pandemic situation, and the coping strategy they employed to overcome this hazard. Participant observation also helped this study get firsthand knowledge about the indigenous peoples’ survival experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic situation and the impediments that made their lives susceptible during lockdown periods.

For conducting this study, in-depth interview was adopted for data collection. The logic behind choosing this method for data collection was that, it is a strong tool for capturing qualitative data by soliciting respondents’ perceptions in their own words [25]. Furthermore, this method is more flexible and practical, as it is not restricted to fixed questions [26], which aided in the investigation of in-depth and vivid information from indigenous people about their suffering as a result of the pandemic situation and how they responded to this COVID-19-related hazard in their community. Given this context, the current study selected 55 respondents (45 indigenous people and 10 stakeholders) from Rangamati sadar upazila (sub-district) of Rangamiti districts for data collection. COVID-19-affected and non-affected indigenous people aged (15–70) from the selected area were the unit of this study. The household leaders were given priority to choose as participant in the study, and only one participant was taken from each household to avoid redundancy of information.

Focus group interview may be denoted as a research technique that collects data through group interaction on a topic determined by the researcher. We adopted focus group interview to get broad view about the effects and susceptibility of COVID-19 on the indigenous community. For conducting this project, five focus group interviews were conducted: two with male indigenous people, another two were with female indigenous people, and the rest with NGO workers, members, and volunteers of that area. Respondents were informed and invited formally before organizing the FGs following health guidelines. They were conversant regarding the purposes, objectives, and outcome of the study project before arranging the FGs. Each focus group was comprised of 8–10 participants with heterogeneous ages, religions, occupations, and diverse backgrounds. Researcher moderated the discussion in the group, and a research assistant helped the researcher write the information that arose in the discussion.

As the purpose of this research is to assess the impacts and vulnerability of COVID-19 on indigenous people and their response to combat it, we selected knowledgeable indigenous peoples from the study area by employing criterion-purposive sampling. Criterion-purposive sampling helps us select relevant participants specifically to address the requirements of research objectives and goals.

We used qualitative thematic analysis to carry out the study. For this reason, data analysis followed description, analysis of themes, and interpretation of researchers [27]. Data analysis in this research started immediately with the field work and continued throughout the study and even beyond. This data analysis comprised with the generation of themes and the interpretation of the procured data. In the beginning of the research, both the themes and interpretation of data were likely to be in a tentative form. This was a recursive process where themes, data interpretations, and data gathering were likely to evolve over time [28]. Following this process, an impression and interpretation were made throughout the study, and at the end, a bulk of interpretation might come when most of the data collection would be finished and an overall view of the situation might emerge from the interpretation [28]. We finished fieldwork after “theoretical saturation” which means when no new themes or new insights were obtained, we closed our field work [29].

The project has been approved by the Human Subject Ethics Subcommittee (HSESC) (or its Delegates) of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (HSESC Reference number: HSEARS20190826003). To maintain ethical consideration, this study followed the individual informed consent process.

4. Result of the study

4.1. Socio-demographic profiles of the participants and stakeholders in CHT

Indigenous people in CHT do not have sufficient opportunity to get an education as there are not enough educational institutions in the locality. Due to a poor communication system and being situated at an educational institution far from their residence, many indigenous people become unable to send their children to school or colleges. The literacy rate among indigenous people is not satisfactory, as only 29% and 20% of people are primary and secondary educated, respectively. A large portion of people are illiterate, and their number is approximately 34%. Due to the limited employment opportunity in CHT, a large portion of people depend on agriculture for their subsistence, as 25% of respondents indicated, and only 14% of respondents depend on agro-based labor for their livelihoods. Only 3% of respondents work for the government, and 18% knit clothes in addition to being housewives (see Table 1 ). The income level of indigenous people is not satisfactory, as almost half of the respondents’ (45%) income is below 10,000 BDT and only 7% earn more than 30,000 BDT monthly. Almost all respondents in the indigenous community need to spend all of their money on family expenses and even borrow money from others to meet their family demands, according to 89% of respondents, whose average monthly cost is around 00–20,000 BDT. Women in indigenous communities also work in agriculture to help their husbands, as well as knitting traditional clothing to sell in the market to cover family expenses. Among the respondents in the study area, approximately 49% are men and 50% are women, 78% are married and 14% are unmarried, and the rest are widows (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profiles of the participants and stakeholders in CHT.

| Socio- demographic profiles | N = 55 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Educational status | ||

| Illiterate | 19 | 34.55 |

| Primary | 16 | 29.09 |

| Secondary | 11 | 20.00 |

| Higher Secondary | 5 | 9.09 |

| Graduate | 3 | 5.45 |

| Post-graduate | 1 | 1.82 |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 27 | 49.09 |

| Women | 28 | 50.91 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 43 | 78.18 |

| Unmarried | 8 | 14.55 |

| Widow | 4 | 7.27 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Farmer/Jhum cultivation | 14 | 25.45 |

| Agro-labor | 8 | 14.55 |

| Govt. Job | 2 | 3.64 |

| Teacher | 3 | 5.45 |

| Businessman | 4 | 7.27 |

| Housewife/Knitting clothes | 10 | 18.18 |

| Headman/Karbary | 4 | 7.27 |

| Volunteer/NGO workers | 2 | 3.64 |

| Administrative leader/workers | 5 | 9.09 |

| Wage Labor | 3 | 5.45 |

| Age of the respondents | ||

| 15–29 | 9 | 16.36 |

| 30–39 | 11 | 20.00 |

| 40–49 | 12 | 21.82 |

| 50–59 | 8 | 14.55 |

| 60–69 | 10 | 18.18 |

| 70- Above | 5 | 9.09 |

| Income of the respondents (BDT) | ||

| 00-10,000 | 25 | 45.45 |

| 11,000–20,000 | 19 | 34.55 |

| 21,000–30,000 | 7 | 12.73 |

| 31,000-Above | 4 | 7.27 |

| Expenditures of the respondents (BDT) | ||

| 00-10,000 | 27 | 49.09 |

| 11,000–20,000 | 22 | 40.00 |

| 21,000–30,000 | 4 | 7.27 |

| 31,000-Above | 2 | 3.64 |

Source: Fieldwork (Here one USD equal to 85 BDT)

4.2. Perceptions of indigenous people toward COVID-19

News of COVID-19 spread among the indigenous community through mass media such as television, radio, newspapers, and other news portals. Some indigenous people also talked about the virus in the community. At first, indigenous people did not pay much attention to this virus because it was then only found in China and not in Bangladesh or elsewhere. Moreover, they had come to know that it spreads out in winter season in cold weather. Therefore, in Bangladesh, it could not become more severe as winter comes here only two months. Moreover, the virus first appeared in Bangladesh in the early days of summer. So indigenous people could not find anything worrying in the initial stage. Nevertheless, on March 8, 2020, when the first case of Corona virus was detected in Bangladesh and the detection rate was gradually increasing, both the mainstream and indigenous communities became worried about the virus. In this context, one of the indigenous interviewees said:

“When the Corona virus was detected in Wuhan, China, first, we got the news from television and thought that it might not come to Bangladesh due to the prevalence of hot weather. From the media, we had also come to know that wearing mask could protect the spread of this virus from human beings to human beings. Unfortunately, when the virus was first detected in Bangladesh in March, it also blew out speedily and made devastating situation in Bangladesh. At first, we felt worried about the virus because we did not know anything about its nature, but after getting the news from the government, we tried to follow that to protect ourselves from the virus.”

From the interpretation of the transcript about the perception of COVID-19, it is found that indigenous people believe that the Novel Corona virus is nothing but the curse of God, and being angry with humankind, God sends this virus to the universe due to increasing unsocial and evil activities on earth. Moreover, nature is frequently exploited by the misdeeds of human kind, so it also takes revenge by offering this deadly disease/virus to the human beings that compel them (human beings) to confine themselves in houses and restrict them from exploiting the motherly universe. Indigenous people believe that the universe could return to normal ways and the virus might be gone if people satisfy God by following ritualistic activities and prayer and by discontinuing all evil tasks.

4.3. Impacts and vulnerabilities of COVID-19 on indigenous people

When the Novel Corona Virus broke out in Bangladesh in the middle of this ethnographic fieldwork, indigenous people, like mainstream people, had no comprehensive knowledge of the virus because it was the first time for the people of Bangladesh as well as the rest of the world. As a result, when the first COVID-19 patient was discovered in Bangladesh, people all over the country became concerned about what they could do to protect themselves. Having no knowledge about the nature of the virus, people kept keen eyes on the government's information and guidelines, but sometimes the contradictory guidelines of the government made people confused about their dos and don'ts regarding the virus's protection, as indigenous people claimed.

4.3.1. Disruption of livelihoods and income generating activities and price hikes in CHT

Indigenous people are not only affected by the outbreak of COVID-19 but also face the crisis of subsistence. Most of the people in CHT depend on natural resources and agricultural activities for their subsistence, but the imposition of lockdown and restrictions on movement make their subsistence difficult to manage. Many of the people in the indigenous community live hand to mouth, so they faced severe vulnerability during the pandemic periods (see Table 2 ). During the lockdown, these people cannot go out for working and face a great problem in their life. In this context, one of the indigenous people demonstrates: “Due to lockdown, we are confined to house and cannot do any income generated activities for family. We also cannot sell our own vegetables and crops or buy our daily commodities due to lockdown, and we lead a very miserable life in the community. Sometimes, we can sell some agro-products but the price is very cheap but the products which we buy are expensive.”

Tables 2.

Impacts and vulnerabilities of COVID-19 on indigenous people.

| Types of vulnerabilities | Impacts and vulnerabilities of COVID-19 on indigenous people |

|---|---|

| Economic & subsistence | Threat of traditional livelihoods; Loss of income generating activities; Cannot sell and buy products in the market; Crops/vegetables are rotten and damaged in the fields; Price hiked and unable to buy necessary products; Loss of jobs; Impede to wave/knit and sell traditional dresses; |

| Deprivation of health-related services | Limited access to expert doctors; Limited access to hygienic material, i.e., masks, sanitizer, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) etc.; No medical health center in the locality; Have to depend on traditional healers; No facilities to COVID-19 test and contact-tracking system; Have no awareness about diseases or risks of diseases; Poor communication impedes to get medical treatment |

| Deprivation of education | Deprivation from getting formal education; Have limited access of online education through TV/internet; Having less aware about getting education; Poor network system to get access of internet/mobile; Limited access to smart phone/computer/TV; Less capability to meet educational expenditures; |

| Disruption of culture & tradition | Disruption of cultural gathering such as harvesting crops, marriage ceremony, celebrating religious function, gossiping etc.; Elderly people are the savior of traditional knowledge, wisdom, and expertise but they are under the great risk of COVID-19; Chakma language is under great threat as elderly people are the main users; |

| Land grabbing and violations | Land is grabbed by settler people; Due to lockdown, cannot get media coverage and support from law enforcement authority; Widow and destitute women loss their lands/belongings; |

| Relief/supports | Getting limited support from GO/NGOs in lockdown periods; Deprived from getting relief/loan; Unequal distribution of relief; |

| Social sufferings | Stigmatized for the infection of COVID-19; Getting negligence to return from city in the community; Inhuman sufferings in quarantine process; No scope to go temple for prayer; |

| Political sufferings | No scope to go outside during lockdown; No freedom to take decision; Political leaders pay no heed to our sufferings; |

Source: field work

Rangamati is one of the most attractive tourist places in Bangladesh, and many indigenous people in this locality directly or indirectly get some earnings from this industry. To demonstrate the point, consider the women of the Chakma community who sell traditional fabrics such as “Pinon Hadi” in local markets. (The traditional dress of the Chakma indigenous people is called “Pinon Hadid.” The upper part of the dress is called Hadi, a piece of cloth worn transversely across the body over the shoulder. The lower part is named Pinon, a sort of long and straight wrap around skirt). The tourists who come from different parts of Bangladesh buy these products with great attraction, but due to the outbreak of COVID-19, people are not allowed to come into Rangamati, and women also cannot sell their products in the market. In this context, one of the Chakma women demonstrates:

“… knit different traditional dresses in our community and get some orders from the businessmen, but due to the prolonged lockdown, we cannot get any orders from the businessmen that reduce our income source. Though income sources are dwindling, costs have risen as we must pay two to three times the real price for everything”

Furthermore, due to the virus outbreak and lockdown situation, the price of every product in CHT has skyrocketed. Shopkeepers claim that due to limited access to products in the market, prices are higher for the products (see Table 2). Though the local administration tries to strictly implement the law, the situation of price hikes is still out of the control of the general public. One Chakma person commented on the price increases, saying, “The price of 5 BDT for a mask reached 40–50 BDT, 90 BDT hand wash became 300–350 BDT, which were essential to buy at the time, but it is out of control for general people. The price of foods and other products has also increased a lot. We have different vegetables and fruits, but we cannot bring them to the market due to the lack of movement of vehicles.” (Here, 1 USD equals 85 Bangladesh Taka (BDT)).

Many indigenous people had worked in garment industries in Dhaka and Chattogram, but prolonged lockdown forced the closure of these industries, consequently, these people lost their jobs and faced severe vulnerability during the pandemic situation (see Table 2).

4.3.2. Deprivation of getting modern health services and educational opportunities to indigenous people in CHT

Many Indigenous people in CHT live in remote hilly areas where people are generally unaware of the diseases and risks posed by COVID-19. If any indigenous people feel sick, due to their poor communication system, they have limited access to consult expert doctors. Moreover, in their locality, there is no medical health center for getting treatment. As a result, they must rely on faith healers and traditional medicine for treatment. During this pandemic situation, there is hardly found any facility to test COVID-19 and provide good treatment. If anyone is affected, it takes several days to conduct the test and receive the report; in some cases, the test is not even possible. In addition, there is a shortage of hygienic materials such as hand sanitizers, masks, gloves, clean water, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other dis-infectious materials that are liable to control the spread of Corona virus quickly in the community. There are some villages in the indigenous community where there are no pavement roads for communication. To get to the main road and take a vehicle to the hospital, two to three canals, or sora, must be crossed, as well as hills. So, it is very difficult to get basic treatment, let alone the standard treatments for indigenous people in the locality (see Table 2). However, sometimes due to cultural affinity or even community belief, they depend on traditional healers for treatment, and only when they feel the severity of any disease, they consult expert doctors in the city hospital. About the medical treatment system, one of the indigenous interviewees demonstrated,“The hospital is far away from our community, and it is expensive for us to get treatment. We seek treatment from traditional healers and rely on traditional medicines for treatment.”

Due to the lockdown and closure of educational institutions, children and young people are deprived of getting a formal education. Due to a poor communication system and insufficient educational institutions/facilities, a large proportion of indigenous people are deprived of getting an education in CHT. During the pandemic, educational institutions introduce education program on television and online but because of poor network and unavailability of televisions among many families in indigenous community, children and young people get deprived of getting education. At the higher education levels, classes are offered online, and for this, it is necessary to get high-speed internet and computer/smart phone facilities. Unfortunately, many indigenous students do not have access to these facilities due to financial constraints. Chakma people consider smartphone and computer to be luxury products. However, those who have smart phones cannot get access to the internet connection due to the poor network system in the hilly area (see Table 2). During interviews, it was discovered that some students climb to the roofs of buildings or the tops of trees in order to get a good internet connection to access the class. Many of these indigenous students stayed in university residence halls for their education during the running of the university at a cheap cost, but they had to return to their village when the university was closed to curb the spread of the Corona virus. About the access to education during COVID-19, one of the indigenous students claimed, “We find difficulty managing money to buy food for our family. Having a smart phone or computer to get access to classes along with an internet connection is a daydream to us because we find even greater difficulty buying educational instruments such as exercise books (khata), pens, pencils, etc. and paying tuition fees.”

4.3.3. Disruption of cultural tradition in indigenous community

COVID-19 has far-reaching impacts on inter-generational activities of indigenous people because throughout history, they have lived collectively, arranging different traditional gatherings, harvesting crops, doing jhum cultivation, celebrating religious functions, arranging marriage ceremonies, playing traditional games, even combating natural and man-made hazards, but the pandemic situation has made them separate, which disrupts their cultural norms and traditions. It not only affects their culture but also individual psychological conditions as well as the physical health of the Chakma community.

About the disruption of cultural tradition, one of the elderly Chakma quotes, “In the past, after finishing our work, we sat down under a big tree and gossiped with other people, sang folk songs, and played traditional games, but due to the outbreak of COVID-19, we could not meet in a place and even could not go outside of our house. Consequently, our cultural practices are gradually declining day by day in CHT.”

From the study finding, it is found that the affliction of elderly indigenous people during this pandemic situation is a great loss to the indigenous community because they play a vital leadership role in the community and are the reservoir of traditional knowledge, wisdom, history, mythology, and language of that community. The passing away of elderly indigenous people due to infection by this virus is thus a great loss to their existing culture as a way of life, stock of knowledge, conservation of biodiversity, and ancestral expertise. Even the knowledge of traditional medicines is practiced by elderly indigenous people. Many young Chakma in the Chakma community do not know the Chakma language. Though some of them can read and write, a large portion of them cannot write and can only speak. Elderly people are the saviors of this language, so the sudden demise of these people, may disrupt or extinguish the long traditions of the indigenous community within a few days (see Table 2).

4.3.4. Land grabbing and other exploitations in indigenous community

Indigenous people have a close relationship with land and nature. They recognize land as a sacred object and worship it. During the pandemic situation, some mainstream settlers try to grab lands of indigenous people thinking that because of lockdown nobody could come to help indigenous people. So, they evict indigenous people from their land and grab their land and property. Many times, the media is not seen to cover the news. From the empirical data, it is also found that sometimes law enforcement authorities remain indifferent, even facilitating the environment to exploit the indigenous people. In this case, widow and destitute women in this case face severe vulnerabilities as their lands are frequently grabbed by settlers. In the lockdown periods, several of the hard-core people's lands are grabbed, and they become more vulnerable, losing their last and only resources. Due to the lockdown and pandemic situation, these vulnerable people cannot get any support to protect their lands and lead a very miserable life in the locality (see Table 2).

After losing jobs due to lockdown, hundreds of thousands of indigenous garment workers return to their village, but on the street, they are seized by the law enforcement authority and face exploitation. Many of the women garment workers are also physically and mentally tortured by the law enforcement agency. After waiting for a long time, these workers get released after negotiating with the sub-district and union council chairman and go under quarantine in their locality but cannot get any relief, even food and water, from the administration. During their quarantine, these workers have to manage their foods and other supports from their family (see Table 2).

4.3.5. Socio-political vulnerabilities and indigenous people

During the COVID-19 pandemic situation, indigenous people face multiple vulnerabilities. The people who were affected by COVID-19 face social stigma as people skip them even though they recovered from the diseases. Everybody was afraid to talk with affected people and forced them not to go out of the house even after the recovery. These people lose their position in society. Indigenous people who lose their jobs in the city face stigma when they return to their communities, as the general public does not welcome them warmly if they may bring viruses from the city. These people also lose their decision-making power in the family after losing their jobs. Rumor and misinformation also sometimes deceive indigenous people, and suffer a lot in terms of getting fake medicine, buying traditional medicine at a high price, using a fake amulet to protect against the Corona virus etc. (see Table 2).

4.4. Responses and resilience of indigenous people to COVID-19

When we resume ethnographic field work after the lockdown and the post-first wave of COVID-19 in Bangladesh and CHT, we get exciting information from the indigenous people. Very few indigenous people are affected by COVID-19 and the mortality rate is very low among these people in the indigenous community. From the empirical data and evidence-based perception, it is clear that due to living very close to nature in remote areas and doing hard work in the hills and lands, the resiliency and recovery powers of indigenous people are greater than those people in mainstream society, and thus the mortality rate is very low for the people of this community.

4.4.1. Precautionary measures during the COVID-19 pandemic

Traditionally, indigenous people take different traditional medicines to protect themselves from diseases. To avoid the infections of Corona virus, indigenous people take some precautionary steps. They drink hot water and take lemon tea several times in a day as virus can be crashed if it enters their throat and lung. They also use ginger, cardamom, black cumin, honey, etc. in their everyday lives, so that the virus cannot affect them. Those who are suffering from colds and coughs, take a honey and basil leaf (Tuloshi leaves) mixture as medicine to recover from the diseases. Some people use neem leaves (Azadirachta indica) with slightly hot water for bathing, as this virus may be killed during their baths. Some indigenous people take water stream as vapor into their nose, so that virus becomes ineffective in their throat and nose. The Chakma people who are economically sufficient try to eat vitamin C containing fruits such as oranges, blood oranges (Malta), lemons, grapes, guavas etc. to boost their immune systems. Some of the indigenous people go to faith healers to take amulets (tabij) or traditional medicines to ensure that the Corona virus cannot infect them. Many indigenous people plant traditional medicinal seedlings in their home yards and use this medicine to boost their immune systems (see Table 3 ). Traditionally, throughout the generation they depend on different indigenous medicines to recover from diseases. Moreover, many indigenous people go to temple for prayer to Buddha so that they can remain safe and secure from the evil diseases of the Corona virus.

Tables 3.

Responses and resilience of indigenous people to the COVID-19.

| Responses and resilience of indigenous people to the COVID-19 | |

|---|---|

| Precautionary measures and community resilience | Drink hot water, lemon tea with ginger, cardamom etc. to vanish Novel corona virus; Take Basil (Tulashi) leaves and honey mixture to remove cold; Use neem (Azadirachta indica) leaves with mild hot water for bath; Wear mask maintaining distance, frequently wash hand with soap to curb the spread of virus; Take water stream as vapor into nose & throat to remove virus; Eat vitamin C related foods to boost immune system; Go to faith healers for getting amulet and traditional medicines; Solidarity and mutual co-operation for community resilience; Exchange of foods and supports to overcome vulnerability; Exchange rice in lieu of vegetables with neighbors to fulfill demand; Try to produce all commodities inside the community except iron, oil, and salt; Try to maintain traditional livelihoods following indigenous knowledge and wisdom; Avoid to depend on market to minimize risks of infection; |

| Announcement of lockdown, quarantine procedure and resilience | From their ancestors, follow lock down process; Self-imposed isolation or quarantine is practiced; Religious leaders imposed spiritual lockdown to specific locality; Mandatory for outsiders to quarantine 14 days to enter community; Make jhum house in forest (far distance from community) for arranging quarantine; Search wild foods such as potatoes, vegetables, forest, creepers as foods in quarantine periods along with other foods; Suspected people are kept isolated and sent sample to test; |

| Formulation of policy, village committee, and volunteer works | Village committee monitor the movement of villagers/people to inside and outside; Fence wall is made surrounding the enter point (gate) to monitor and social gathering is restricted such as marriage ceremony, religious festivals, funeral etc.; Only shop keepers and selected people are allowed to go market and bring goods for all villagers maintaining rules; Raise fund by volunteer to help vulnerable people; Spray different busy points for disinfection; Post in Facebook timeline for volunteer works to encourage young people to join the organization; Form sub-groups to work in own area in community level; |

| Relief/getting loan for resilience | Get relief from government/NGOs that is not sufficient; Lend/borrow money from relatives/friends to overcome vulnerability; Mutual co-operation from the neighbors and relatives; Cut of meals three to two even one in distress/lockdown; Use savings to buy foods and other emergency needs; |

| Strengthening traditional livelihoods centering lands and natural resources | Develop resilience centering natural resources and land by collecting and producing crops/vegetables in CHT; Follow ancestral and traditional food production systems; Avoid monetary and market based live as much as possible; Plant timely demandable plants such as orange, lemon, pine apples, guava etc.; Plant traditional medicinal seedlings in home yards; Small scale entrepreneurships such as grocery shops etc.; |

| Rumor may work as local response and resilience | Though rumor/misinformation brings suffering to the people but ultimately it makes people careful about the COVID-19 that help to curb the spread of the virus in the community; Community leader forced suspected member to remain confined in house to avoid unexpected risks of spreading COVID-19 virus whether that person is infected or not; Though rumors have no scientific value and have no direct relation to protect the infection of COVID-19 but it may positively impact to remove mental disorder and bring some happiness to those people who do somethings for protection following rumors; |

| Traditional faith healer and traditional medicines | Depend on faith healer and traditional medicines; Take amulet to protect AVA PIRA virus (respiratory diseases); Faith healers made medicines with traditional plants collecting from forest such as leaves, roots, bark/cortex etc.; Take amulet/tabij and black magic to protect virus; |

| Ritualistic activities to overcome COVID-19 | Stop evil tasks (sin) to curb infection of COVID-19; Stop exploitation to nature to stop COVID-19; Prayer to God to stop spread of COVID-19; Offer puja and oblations to God and religious leaders; Sacred and humanistic works and ritual bestow mental strength to overcome adversity; Sacrifice animals in the names of Ganga and Bon Badshah to recover from corona virus; |

| Response of indigenous women in COVID-19 | Knit traditional fabrics and sell communal market after relaxation of lockdown; Enjoy more freedom than mainstream women to decision making in pandemic situation; Utilize unused lands for horticulture and plant different seedling to fulfil family needs; |

| Restoration of natural environment in lockdown periods and resilience | Restricted consumption of natural resources helps to restore the beauty of natural environment; Closing market and vehicles in Lock down, restore the beauty of nature due to less destruction; Intimate relation with nature makes indigenous people stronger to develop resilience; Maintain traditional life in remote area to cut off infection |

Sources: field work

4.4.2. Announcement of lockdown, formulation of village committee, quarantine procedures, and resilience in CHT

The experience of lockdown is not new to the lives of indigenous people in CHT. Elders in the indigenous community indicate that indigenous people have practiced lockdown since the ancestor periods. The knowledge of indigenous people is formed through observations and experiences spanning hundreds and thousands of years. Throughout the passing of adversity, pandemics, and outbreak of different diseases, indigenous people have gathered this knowledge and wisdom and applied it when they thought it was necessary in their community.

Previously, if a respiratory disease spread throughout the community, the village leader (headman) would impose a lockdown and create a demarcation to prevent other people from entering. In this context, the “cholera” disease can be referred to, which affected a large part of a locality in the past. At that time, also, lockdown and quarantine or self-imposed isolation practices were prevalent in the indigenous community. It may also create a controlled zone where people are not allowed to enter or leave. The spiritual leader of the indigenous community performs spiritual rituals to control the diseases. This leader will spiritually seal off a specific territory so that diseases or evil powers cannot enter and harm them. The traditional faith healers with traditional medicines treat most of the disease in this locality, and many times people get recovered. Generation after generation, indigenous people keep their faith in these traditional medicines and practices for getting treatment (see Table 3).

During the lockdown across the country, a village committee is formed, including the headman and Karbhari (village member) of each village, along with formulating some policies to monitor the villages. This committee strictly controls and monitors the movement of community members in the locality. Every entry point (gate) of a village has a fence wall, and some assigned indigenous people always stay there to monitor the movement of people insides and outside the village. Before implementing the policy strictly during lockdown in the community, those who are community members but stay outside are given a chance to return to the village within a definite timeframe. If they fail to return within that time frame and come later, then they also need to undergo 14 days of quarantine in the locality. After the implementation of the policy of lockdown, no one can enter the community without undergoing 14 days of quarantine and any person from the village has to undergo 14 days of quarantine if they go to the city and return after that (see Fig. 2 ). Social distancing and self-imposed isolation are also implemented in the community, and it is mandatory to wear a mask if any person goes outside the house, and social gatherings restricted, such as marriage ceremonies, funerals, social festivals, etc. If any person enters the community from the city for emergency purpose, he or she cannot stay the night without undergoing quarantine (see Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Doing quarantine in Jhum house (temporary tent) in the forest far away from community.

Source: Field work

During the lockdown periods for maintaining quarantine, some places in the forest are selected that are far away from the community, and a temporary tent (Jhum house) is established there for maintaining quarantine (see Fig. 3 ). Different types of foods, i.e., fried rice, biscuits, rice, vegetable, oil, salt, and other commodities are provided to them, and they (isolated people) need to cook those for eating. During the quarantine time, no money is taken from the isolated person as virus may spread through the money of that parson. After the completion of quarantine, they can pay the money to the member who provides them with foods. Sometimes, family members or relatives provide food to the isolated people, but that must be maintained a distance and cannot be talked to directly. If any member violates the guidelines of the procedure, he/she also needs to undergo a 14-days quarantine in the remote forest. Local administration and goverment. are not seen to provide any food or drinking water to the people who do quarantine in indigenous communities.

Fig. 3.

A temporary Jhum house for undergoing quarantine in the forest premise.

Source: Field work

4.4.3. Unequal relief distributions, hardships, and resilience

In CHT, indigenous people get very little relief from the government as well as other organizations, which is not sufficient for them. The distribution of relief is also not fair as many times this relief cannot reach the root level, where the really affected people are living, as the results of focus group indicate. In this context, one of the Chakma indigenous people demonstrated,

“… get very small amount of relief from the government, and it is 20 kg of rice, 2 L of soybean oil, 500 g of peas (dal), and 500 g of salt over the last 4 months that can fulfill only two weeks of demand in our family. So, in order to survive, we must cut our meals in half and consume them twice a day rather than three times.”

Apart from this relief, the prime minister of Bangladesh announced a fund for the poor. To reduce corruption and ensure that funds are distributed to each vulnerable family, a list is created across the country, and 30 USD (1 USD equals 85 BDT) is sent to their mobile number via a Bkash (mobile money transfer) account. It is a matter of sorrow that corruption is still not stopped, as many rich family names are on the lists and the same numbers are given several times to get more money. The prime minister wants to ensure transparency, but some corrupted officers and leaders use it as a source to devour money during the pandemic situation, as many of the participants highlighted.

During lockdown, indigenous people who have no work or income face huge problems in their lives. Those who have some savings try to use them in conjunction with other sources of relief or earnings (see Table 3). About finding money, one of the Chakma interviewees quoted, “Finding no other ways, I took loan from a NGO to bear the expenditure in my family, hoping to pay back the money by working hard when the pandemic situation would be improved. During the pandemic situation, it is not easy to get a loan or lend money due to uncertainty as nobody can know what is happening in the near future.”

4.4.4. Strengthening the possession of traditional livelihoods centering lands and hills

Indigenous people recognize land and nature as sacred objects and worship them in their lives. Throughout the history, they develop resilience to any adversity centering the lands, hills, and nature. Historically, most of the indigenous people in the Chakma community depend on indigenous land and cultivation systems to generate food, and because of COVID-19, they strongly follow their ancestral and traditional food production systems and try to feed themselves by avoiding depending on external foods and market-based livelihood systems. Rather than following the mainstream system, Chakma people follow their traditional communal works, express solidarity, and reciprocity and limitedly depend on monetary exchange for maintaining their livelihoods. So, when the lockdown is gradually relaxed, indigenous people start to get involved in their agricultural activities more intensively and depend on natural resources as the market-based foods become very expensive and not available sufficiently in the community. In this case, indigenous peoples’ utmost demand is to stop encroachment on traditional lands and the illegal logging of trees for brick fields and other purposes because it also destructs the environment and intensifies the scarcity of forest resources in the hills (see Table 3).

Indigenous people have a very small amount of savings in their lives, and due to their dependency on nature for livelihoods and their limited tendency to accumulate profit, they are destroying the environment. During the pandemic, when indigenous people see that their small savings and rice/foods are gradually consumed, they no longer remain confined in the house. They are scared not only of the Corona virus but also of starvation, as they may run out of food. As the density of population in remote hilly areas is low and most of the people work in hills and forests, they start to work to maintain distance and follow health rules. Along with cultivating paddy and vegetables to fulfill their basic needs of foods, they try to plant timely demandable products in their fields or hills for market, such as oranges, blood oranges (malta), pomelos, lemons, pineapples, guavas, etc. which become money earning products in the COVID-19 period. Some indigenous people also plant traditional medicines in their fields. Many indigenous people who lost their jobs in the city as a result of the Corona virus begin to work in the fields to support their families in the community. Some migrated Chakma people do small scale entrepreneurship in their community or run small grocery shops. They have some savings from their previous jobs and try to recover from their economic hardships in the locality (see Table 3).

For building resilience, indigenous people apply multiple strategies in adverse situations. Those who have rice in the house, for example, try to rely on wild forest resources such as forest creepers, roots, tubes, potatoes, vegetables, mushrooms, and so on for curry and fish in the canal or sora to survive without relying on the market. Only for oil, salt, and other emergency needs, they have to go to market.

In this context, one of the elder Chakma people said, “In the past, there was no market near our community as we did not need to go to the market normally, because we produced almost all the goods for our family in the community. Recently, due to the pandemic, we are trying to get back to our ancestors’ traditional lives, so we can save ourselves and our community from the infection of COVID-19”.

4.4.5. Spreading of rumor and local response and resilience in indigenous community

In CHT, many of the indigenous people fall into the trap of religious leaders through misinformation. One of the religious leaders announced that one child after birth can start to talk and advise people that after 12 a.m. if people pick up water from the well or sora and drink it in one breath, the coronavirus will not affect them anymore. After hearing this news, hundreds of indigenous people began to drink water from the well (sora) to get relief from Corona virus infection. Some indigenous people in the Facebook timeline posted that wine is effective to protect against coronavirus. So many people started to drink wine even more to protect themselves from the diseases caused by the coronavirus. Many of the parents who forbade their son and daughter to drink wine gave them wine for drinking. This trend made many people to become sick and admitted to hospital. About another misinformation one of the interviewees delineate: “Due to wetting in the rain, my daughter caught a cold and fever, and I brought her to a hospital for treatment as the fever continued for several days. Meanwhile, there broke out a rumor in the community that my daughter was infected to corona virus and lockdown was imposed to our house and nobody was talked with us after that. Fortunately, after a few days, my daughter recovered from the fever and is now fully well.”

Though these rumors had given some mental stress and suffering to the people being suspected to COVID-19 infection but it raised awareness among the members to become careful to curb the spread of the virus in the community. So, this rumor worked as a local response to stop the outbreak of Corona virus, because the village leader forced their suspected member to remain confined in house to avoid unexpected risks of spreading COVID-19 infection, and in this case, whether that person was infected or not was not the matter (see Table 3).

Though these types of information have no scientific value and have no direct relation to protecting against COVID-19 infection, they have a positive impact on removing mental disorder and bringing some happiness to those who are very excited and tensed about the virus in the indigenous community. Because they believed that this information was effective for them, it gave them some sort of mental relaxation and strength, even though it has no scientific value at all.

4.4.6. Traditional faith healers, traditional medicines, and resilience from COVID-19

In the indigenous community, the influence of Bodhya (faith healer) is enormous. During the lockdown, indigenous people are not allowed to get treatment outside the community or in the hospital to curb the spread of infection. At that time, only Bodhya (traditional healer) gets the responsibility to treat people in the community. Not only in pandemic time but also year-round, they treat indigenous people professionally. About getting treatment from a faith healer during the pandemic situation, one of the interviewees quote:

“My elder son was suffering from pain in the stomach, so I wanted to consult a doctor in the hospital. The headman of the village asked me if I go to city for consulting doctors, I need to undergo 14 days quarantine. So, I consulted a faith healer for my son, and after getting traditional medicine, he recovered.”

Though these traditional healers have no modern instruments to detect diseases but can heal the symptoms of patients, their capacity to identify disease is commendable as they diagnose patients in their indigenous communities generation after generation. However, if the faith healer (Bodhya) fails to identify the disease, they get help from a doctor and are able to provide treatment to the patients. Moreover, having faith in and dependency on these traditional medicines, indigenous people normally do not consult doctors at hospitals in the city, as many of the indigenous people claimed. However, critical patients and suffering from complex diseases patients are referred to expert doctors in hospital. Faith healers make medicines by hand. They collect different branches, roots, bark or cortex, and leaves of trees and plants from the forest and jungles and grind them with the help of stones to make medicines. Every faith healer plants different traditional medicines in their home yards so that they do not need to visit the jungle to collect medicine for treatment. Though traditional medicine is accepted by all people in the indigenous community, some treatments, such as giving amulets (Tabij) and practicing black magic or pishogue (Tontro-Montro) are not accepted by all people. But many faith healers claim that this treatment is also effective for recovering from diseases. They also sacrifice different animals which is called (Dali) in Chakma language. If anybody becomes suddenly ill, then they arrange Dali rituals in the name of ‘GANGA’ in the river and in the name of ‘BON BADSHA’ in the forest or on land and sacrifice animals. Moreover, many people do vow (Manat) for arranging Dali ritual to recover from diseases. In Chakma language, contagious disease is called ‘AVA PIRA.’ Ava Pira means diseases that spread through the wind (see Table 3). Faith healers claim that they have one type of amulet (Tabij) that can protect people from being affected by contagious diseases. The usages and practices of this amulet has increased greatly in pandemic situation. The price of this amulet is $ 4 USD.

About the usage of this amulet, one of the educated Chakma women quoted: “During the pandemic situation, many people use this amulet to protect themselves from getting infected. Though I was confused about the effectiveness of this periapt to fight the Corona virus, I was bound to use it because my father forced me to use it. To keep my parents happy, I used this amulet during the pandemic situation.”

4.4.7. Ritualistic activities as an instrument to overcome COVID-19

According to the religious leader, COVID-19 is the curse of God. Due to the increase of evil tasks (sins) and exploitation of Mother Earth, this disease has appeared on the planet. If people continue to do such evil tasks and destruct the environment indiscriminately, nature will continue to take revenge by rendering different diseases to the world. The religious leaders urge human beings to stop exploiting the environment and doing unsocial activities. They suggest praying to God every day and offering flowers and worship in the temple to satisfy Him to overcome the curse (see Table 3). About the spiritual power of religion, one of the educated Chakma said:

“We pray to God to satisfy Him and do sacred work for our mental satisfaction. We do not know if the coronavirus is the curse of God or not. Or if it has occurred due to the anger of God or not, but it has happened due to the exploitation of the environment and the hunting of wild animals in the forest. Our sacred work and prayer give us mental strength and happiness, which give us confidence to fight against coronavirus.”

4.4.8. Responses of indigenous women in pandemic situation

Indigenous women in the Chakma community have an undeniable impact on the economy and the family. They are the caregivers and earners in small scale productions in their community. Indigenous women wave different traditional fabrics and sell that in the communal marker for income earnings. Though their income has stopped due to the lockdown in their community but after the relaxation of lockdown, they again start to do their business. They knit traditional dress not only to fulfill their family needs but also meet the orders of the businessmen in the communal market.

Chakma women enjoy more freedom than mainstream women in CHT, so they have much influence in family decisions in Chakma community. Chakma women help their male counterparts grow crops and make money in the community by working as wage labor. Though indigenous women play a significant role in economy of Chakma community ranging from caregiving, cooking, collecting water, caring elders, and disabled people, and preforming different household chores, but still, they face discrimination in terms of wages in the local community. Indigenous women for selling labor get 4 USD but doing the same task a man gets 5 USD in their community. This wage discrimination disappoints women to fully participate in the formal economy but to overcome the economic vulnerability, women take part outdoor works along with doing their household chores. During lockdown, nobody goes outside of their house in the fear of getting infection but those who are economically solvent employ labor in the agriculture field for cultivation. For this purpose, they provide 7 USD for men and 5 USD for women.

Due to the lockdown situation for long time, for the recovery of economic deficiency, indigenous women utilize their unused lands for horticulture and planting different seedlings including fruits such as mangoes, jackfruits, pomelos, lemon, guava, and different vegetables in their home yards and other places. This not only fulfill the demands of foods of their family but also ensure the basic foods of neighbors as they exchange this with the neighbors in the community (see Table 3). In this context, one of the indigenous women said:

“We have experience about how to move forward to overcome adversity as we face this during natural hazards in our locality. Though at the beginning of outbreak of coronavirus, we feel anxious due to having no knowledge about the diseases but now we understand that first we ensure our basic food and then need to isolate us from the outsider. We are giving more efforts during the pandemic and try to utilize all unused lands to produce more crops as we can ensure foods for all members in the community.”

4.4.9. COVID-19 pandemic, indigenous people, and natural environment

Though COVID-19 creates a devastating situation across the world, it has some indirect positive impacts on the natural environment, especially due to the imposition of lockdown in CHT. In a lockdown situation, people cannot move because of the restrictions on driving vehicles and movement. So, the stress on nature by human beings decreases a lot, and nature restores its lost beauty and power. To illustrate the matter, before the lockdown, human beings illegally cut down trees, extracted stones from underneath of the soil, cut down hills, and destroyed the environment indiscriminately. Destruction of the environment is generally caused by mainstream people, but due to the lockdown, they cannot reach the forest because of the lack of vehicles and unfavorable environment. Moreover, due to the close of market, they could not sell these resources in the market. On the other hand, most of the indigenous people live in remote area being very close to nature, they can nurture the nature and make their intimate relation like the previous time of their ancestor. They only extract resources for their own needs and not for capital accumulation, so nature is not affected by the deeds of the indigenous community. One of the interviewees says of the regaining of the lost beauty of the natural environment,

“During the lockdown, we can go more deeply into nature as the mainstream people cannot enter the forest to extract resources indiscriminately due to the restriction of moving vehicles and cannot sell that product due to closure of the market. To avoid infection, we also avoid relying on market-based food and collect forest-based wild foods only for our own consumption, avoiding their sale in the market. So, the stress on nature reduces to a great extent, and it regains its lost beauty.”

Moreover, due to the closure of the market, indigenous people get back to their traditional lives and avoid depending on a market-based economy. It not only curbs the infection of the Corona virus but also provides a good opportunity for indigenous people to come closer to nature. In this situation, it can be said that the relationship of indigenous people with nature gives them more strength to build resilience and overcome the vulnerability of the Corona virus. From the interview transcripts, it is found that the infection rate of COVID-19 is very low in the indigenous community during lockdown, but when the lockdown is relaxed, the number of infections increases due to the lack of proper tracing and testing facilities in the community. The government does not provide sufficient facilities to detect the virus in the community. So indigenous people try to maintain their personal hygienic system in their own ways, following their traditional life (see Table 3).

5. Discussion

This study shed light on to find out the impacts of COVID-19 on indigenous people and the ways how they response to the pandemic in the adverse situation. The study findings indicate that indigenous people are not ignorant but aware of the impacts of COVID-19, and they are facing severe problems due to the prolonged lockdown in the community because most of them live hand-to-mouth for their subsistence [8,13]. The prolonged market closure has caused unprecedented suffering in the lives of indigenous people, as they are unable to market their products and many of their produced resources have rotted and been damaged in the field. Nevertheless, they are coerced to sell their products to the local people at cheap rate to minimize their big loss [[6], [13], [16]]. Government should ensure the fair prices of every product of indigenous people before imposing lockdown. Moreover, there should be arrangement for sufficient amenities to meet the daily needs of indigenous people, but the local government imposed lockdown without considering the situation of indigenous people. Law enforcement agency beat/punished general people if they go outside to buy daily commodity during lockdown but govt. did not pay heed to ensure the supply of daily products of general people. Local administration also failed to monitor the price of daily needs as it was very high in the market, and local producers were also deprived of getting a fair price for their products as it was needed to sell at a low price. Moreover, during quarantine, people's basic needs were not met, and their properties were not secured by the active involvement of the law enforcement agency. The findings of this study might convince government and law enforcement authorities about their roles and responsibilities in disaster, especially in emergency situations. If local government can form a committee with the help of the karbari (headman) of the indigenous community and other leaders in the sub-districts to monitor the market system and execute the lockdown during emergencies, then the suffering of local people can be reduced to a great extent.

Chakma indigenous people live in remote hilly area which is considered as neglected and unreachable place to the development organization, as a result there is not constructed modern medical health center to the community [[2], [6], [9], [13]]. For this reason, indigenous people have only the option to consult with a faith healer/Kabiraj for medical consultation in their locality [13]:17; [9]. There is no detective or contact-tracing facility to sort out COVID-19-affected people, and do not have COVID-19 testing facility. As a result, infection rate increased rapidly and affected people were not separated timely. Due to having no COVID-19 test lab, it took several days to identify COVID-19 patients because samples were sent to Chattogram for testing. This study findings can contribute significantly to policy makers especially to ministry of health to set up modern medical health center in CHT along with providing other medical facilities to curb the transmission of COVID-19 and improve the physical health of indigenous people. Government also can raise awareness among indigenous people and encourage them to consult expert doctors rather than going faith healers/Kabiraj to recover from the virus COVID-19.

The people of indigenous community are deprived from getting education as government has introduced formal education through TV and online due to closure of educational institutions for long times [13]. Insufficient education institutions and a lack of facilities for getting online class, indigenous people deprived of this [6]. Before introducing an online and television-based education program in CHT, the Ministry of Education ignored the need to ensure infrastructure development and the availability of internet and devices to indigenous people. This study can contribute significantly by highlighting the pressing needs of educational facilities in indigenous community, especially during emergency situations. The government should ensure equal access to online education facilities as well as other infrastructural developments for education in CHT before introducing online and television-based education programs in Bangladesh.

During lockdown, poor indigenous people have no food or money due to confinement in their home. In this time, they got very little relief from the government as well as other organizations, which was not sufficient to fulfill their needs [15]. The distribution of relief was not fair as many a time real poor people could not get it and could not reach to the root level where the real affected people were livings due to corruption and mismanagement. Local government was indifferent to ensuring the relief of the affected people and ignored efforts to monitor the situation in the local community. The government should ensure a sufficient budget and proper allocation of relief and support to the indigenous people, especially in emergency situations in the CHT.

Indigenous people never depend on relief or the aid of the government or other welfare organizations for their subsistence. Historically, they have had a limited tendency to save money or accumulate profit for their lives while destroying the environment. During times of adversity, however, rather than waiting for help from GOs or NGOs, they help each other's families in the community by providing food, vegetables, natural resources, and even money, in order to overcome the distress. Moreover, in adversity, along with cultivating paddy and vegetables to fulfill their basic needs, they try to plant timely demandable products in their fields or hills for market, such as oranges, blood oranges (malta), pomelos, lemons, pineapples, guavas, etc. which become money making products in the periods of COVID-19.