Abstract

Anti-spike receptor binding domain (S-RBD) antibody against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) which best correlates with virus-neutralizing antibody is useful for estimating the period of protection and identifying the timing of additional booster doses. Long-term transition of the S-RBD antibody titer and the antibody responses among healthy individuals remain unclear. In the present study, therefore, we monitored the S-RBD antibody titers of 16 healthcare workers every 4 weeks for 76 weeks after vaccination with a fourth dose of mRNA-1273 (Moderna) following three doses of BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) using two commercial automated immunoassays (Roche and Abbott). Two antibody responses to the vaccine were similar with an up-down change before and after the second (weeks 3), third (weeks 40) and fourth (week 72) vaccinations, but the titer did not fall below the assay's positivity threshold in any individual. The peak level of the geometric mean titer (GMT) in the Roche assay was highest after the third vaccination, and that in Abbott assay was highest after the fourth vaccination but almost equal to that after the third vaccination. Both the geometric mean fold rise (GMFR) demonstrated by the Roche and Abbott assays were highest after the third vaccination. Antibody titers determined by the Roche and Abbott assays showed a positive strong correlation (correlation coefficient: 0.70 to 0.99), but the ratio (Roche/Abbott) of antibodies demonstrated by both assays increased 0.46- to 8.26-fold between weeks 3 and 76. These findings will be helpful for clinicians when interpreting results for SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels and considering future vaccination strategies.

Keywords: BNT162b, mRNA-1273, Vaccine, SARS-CoV-2, S-RBD antibody

BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccine and mRNA-1273 (Moderna) have shown promising efficacy and safety during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [1]. Neutralizing antibodies are produced by vaccination and natural infection, preventing further infection and reducing the risk of aggravation [2]. However, functional severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) neutralization assays are not feasible anywhere for attaining biosafety level 3. In contrast, measurement of antibodies in serum/plasma recognizing defined antigens can be performed rapidly and easily using various commercial automated immunoassays [3]. Among antigen-specific antibody isotypes, the level of IgG against the spike protein receptor binding domain (S-RBD) best correlates with the virus-neutralizing antibody titer [2,4]. Therefore, S-RBD antibody plays an important role as an mRNA vaccine-induced antibody. Quantification and standardization of S-RBD antibody is necessary in order to evaluate the immunogenicity and efficacy of vaccines and establish thresholds for protective correlates. Therefore, an international standard for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control [NIBSC] 20/136) was issued by the WHO for better comparison of SARS-CoV2-specific antibody levels [5]. The Roche and Abbott automated immunoassays have been commercially available and broadly used as in vitro diagnostic medical devices (CE-IVD) for SARS-CoV-2 antibody determination. Both assays quantify antibodies directed against the S-RBD and have been referenced against the first WHO standard for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, thus providing results in terms of binding antibody units (BAU)/mL. Some previous studies have investigated the antibody response using various automated S-RBD antibody assays before and after vaccination at a specific time point or in the short term [1,3,[6], [7], [8]]. However, few long-term sequential data in specific individuals are available. The aim of this prospective study was to observe and compare the long-term transitions of S-RBD antibody titers determined by the Roche and Abbott automated assays following three doses of homogeneous BNT162b2 and a fourth dose of mRNA-1273.

This prospective study was approved by the institutional review board of Ehime University Hospital (Approval Number: 2103033). All participants provided written informed consent to donate blood for measurement of SARS CoV-2 S-RBD antibody. Blood samples were collected before the first vaccination, 3 weeks after the first vaccination, and every 4 weeks after the second vaccination. Samples were stored at −80 °C until ready for use. Measurements of S-RBD antibodies were performed using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA; Roche, Elecsys® Anti-SARS-CoV-2S(200)RUO) on a Cobas e602 analyzer and chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA; Abbott, Architect® SARS-CoV-2 IgGⅡ) on an Architect™ i1000SR analyzer. The Roche assay detects total antibodies directed against the viral spike protein receptor-binding domain (S-RBD) and 0.8 U/ml is used as the cutoff for positivity. The Abbott assay quantifies IgG-type antibodies against the S-RBD and 50 AU/ml is used as the threshold for positivity. Antibody units were converted to BAU/mL in accordance with the manufacturers’ information regarding the WHO Standard. The conversions for the Roche and Abbott tests were U/ml * 1.0 = BAU/ml and AU/ml * 0.143 = BAU/ml, respectively (8). We excluded prior SARS-CoV-2 infection using the Roche Elecsys® SARS-CoV-2 ECLIA, which detects total antibodies to the viral nucleocapsid antigen. All analysis was performed using JMP version 14 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). A significance level of p < 0.05 was used in the analysis.

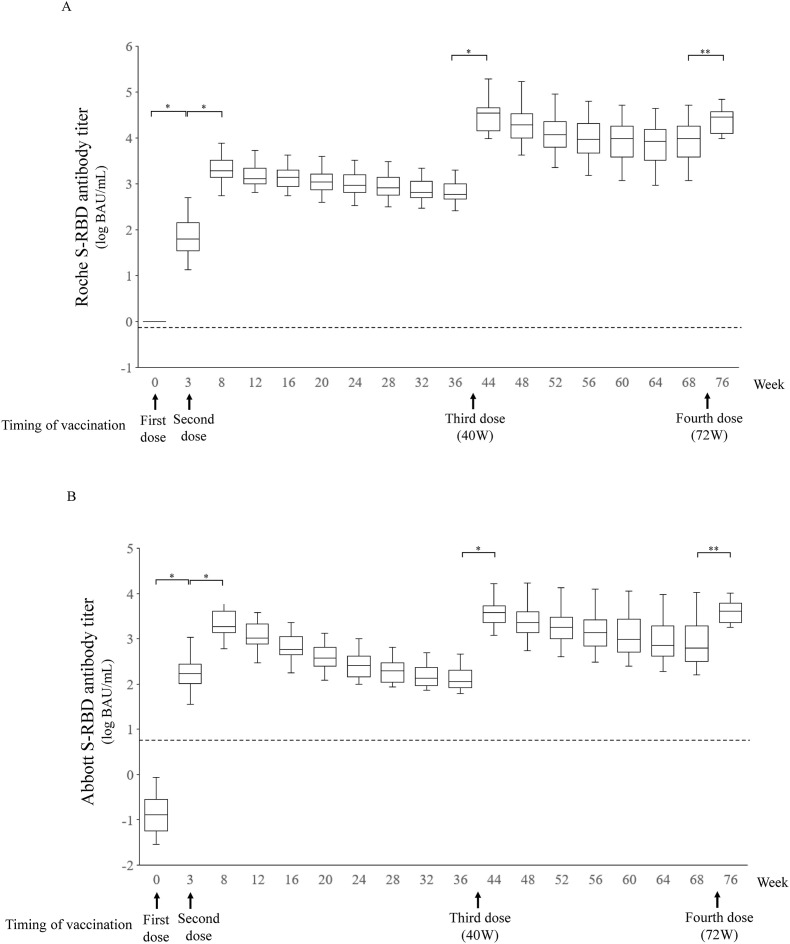

This study was performed between March 15, 2021, and September 9, 2022. Sixteen healthcare workers (HCWs) who employed at Ehime University Hospital participated. The participants ranged in age from 23 to 56 years with a mean of 40 ± 11.8 years with no difference in gender (male 8, female 8) and none had underlying diseases. They were all received three doses of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine at 0 week (first vaccination), 3 weeks (second vaccination), and 40 weeks (third vaccination). Four did not receive a fourth dose of the mRNA-1273 vaccine at 72 weeks (fourth vaccination) because of COVID-19 infection and vaccine rejection. The transitions of both measured antibody titers are shown in Fig. 1 A and B. The antibody responses to the vaccine were similar, with a dramatic increase after the first, second, third and fourth vaccinations. The rates then levelled off rapidly and gradually reached a plateau after the second and third vaccinations, but no titers below the assay positivity thresholds were observed. The geometric mean titer (GMT) and geometric mean fold rise (GMFR) for S-RBD antibodies and a comparison of the Roche and Abbott assays are shown in Table 1 . The peak GMTs for antibodies following the second, third and fourth doses were 2134 BAU/mL (95% confidence interval: CI, 1482–3073), 31,104 (19,534–49526) and 23,834 (16,045–35404) for Roche, and 2068 (1435–2980), 3921 (2562–6001) and 3798 (2636–5471) for Abbott, respectively. The GMFRs for the second, third, and fourth doses were 32.4 (95% CI, 20.6–51.0), 45.3 (30.8–66.8) and 5.53 (3.95–7.75) for Roche, and 12.3 (9.2–16.6), 29.2 (20.8–41.1) and 6.12 (4.42–8.48) for Abbott, respectively. Thus, antibody levels detected by the Roche assay increased 33.6-fold (95% CI, 15.8–51.4) between weeks 3 (after the first dose) and 8 (after the second dose), 25.6-fold (15.6–35.5) between weeks 8 and 44 (after the third dose), and 0.96-fold (0.86–1.06) between weeks 44 and 76 (after the fourth dose), whereas those detected by the Abbott assay increased 14.2-fold (10.1–18.2) between weeks 3 and 8, 2.41-fold (1.27–3.55) between weeks 8 and 44, and 1.28-fold (1.10–1.45) between weeks 44 and 76. The average ratio of antibody detected by the Roche and Abbott assays at the time of each blood collection increased 0.46–8.26-fold from weeks 3–48, and decreased thereafter, reaching a plateau at 6.42–7.36-fold. The antibody titers detected by the two assays showed a positive correlation (correlation coefficient: 0.70 to 0.99) during the study period (As representative data, scatter graphs after each vaccination are shown in Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 S protein receptor binding domain (S-RBD) antibody levels measured by the Roche and Abbott immunoassays. Antibody titers measured by the Roche (A) and Abbott (B) immunoassays are shown. Horizontal lines in the boxes show median values, the notches indicating a 95% confidence interval of the median. Dotted lines indicate the threshold for positivity (Roche: 0.8 BAU/mL, Abbott 7.1 BAU/mL). *, P < 0.0001 in Wilcoxon tests with Bonferroni adjustment (p < 0.0029). Sixteen healthy individuals (who started vaccination in March 2021) had specimens collected before vaccination, 3 weeks after the first vaccination, and 4 weeks apart after the second vaccination. Arrows indicate vaccination timing. One of the participants lacked measurements for after weeks 12, 16, 20, 60, 64 and 68 because of poor physical condition and COVID-19 infection. Four of the participants lacked measurements after 76 weeks because of COVID-19 infection and vaccine rejection. All participants lacked measurements at 40 and 72 weeks.

Table 1.

Geometric mean titer (GMT) and geometric mean fold rise (GMFR) for anti-SARAS-CoV2 spike protein receptor binding domain (S-RBD) antibodies and comparison between the Roche and Abbott assays.

| Number of vaccination | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week after number of vaccination | 3 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 28 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 28 | 32 |

| Week after initial vaccination |

3 |

8 |

12 |

16 |

20 |

24 |

28 |

32 |

36 |

44 |

48 |

52 |

56 |

60 |

64 |

68 |

76 |

| Number of subjects | 16 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 12 |

| Roche S-RBD antibody | |||||||||||||||||

| GMT (BAU/mL) | 66 | 2134 | 1624 | 1463 | 1189 | 1049 | 915 | 766 | 686 | 31,104 | 20,470 | 12,662 | 9710 | 8092 | 6716 | 8092 | 23,834 |

| 95% CI | 39–170 | 1482–3073 | 1140–2316 | 1031–2076 | 817–1731 | 742–1485 | 661–1268 | 559–1049 | 498–946 | 19,534–49526 | 11,977–34985 | 7195–22284 | 5382–17516 | 4257–15380 | 3473–12986 | 4257–15,380 | 16,045–35,404 |

| GMFR | 32.41 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 45.33 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 5.53 | |

| 95% CI | 20.60–50.99 | 0.63–0.77 | 0.83–0.97 | 0.76–0.86 | 0.88–0.96 | 0.84–0.91 | 0.80–0.87 | 0.85–0.94 | 30.77–66.78 | 0.58–0.75 | 0.58–0.66 | 0.73–0.82 | 0.77–0.81 | 0.80–0.86 | 0.85–0.91 | 3.95–7.75 | |

| Abbott S-RBD antibody | |||||||||||||||||

| GMT (BAU/mL) | 168 | 2068 | 1103 | 633 | 388 | 262 | 196 | 156 | 134 | 3921 | 2565 | 1939 | 1503 | 1235 | 938 | 864 | 3798 |

| 95% CI | 110–255 | 1435–2980 | 750–1622 | 428–937 | 267–564 | 182–378 | 140–276 | 112–216 | 97–185 | 2562–6001 | 1556–4230 | 1148–3277 | 846–2668 | 657–2319 | 491–1794 | 439–1700 | 2636–5471 |

| GMFR | 12.34 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 29.20 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.92 | 6.12 | |

| 95% CI | 9.17–16.61 | 0.47–0.53 | 0.54–0.61 | 0.57–0.65 | 0.67–0.76 | 0.71–0.79 | 0.76–0.83 | 0.82–0.91 | 20.76–41.08 | 0.57–0.75 | 0.70–0.82 | 0.72–0.83 | 0.78–0.86 | 0.73–0.80 | 0.87–0.98 | 4.42–8.48 | |

| Comparison between Roche and Abbott antibody | |||||||||||||||||

| Roche/Abbott ratio, average | 0.46 | 1.13 | 1.60 | 2.46 | 3.25 | 4.23 | 4.92 | 5.14 | 5.32 | 8.10 | 8.26 | 6.78 | 6.71 | 6.72 | 7.36 | 7.10 | 6.42 |

| 95% CI | 0.29–0.63 | 0.89–1.36 | 1.26–1.95 | 2.02–2.89 | 2.62–3.87 | 3.46–5.00 | 3.98–5.87 | 4.20–6.09 | 4.44–6.20 | 7.29–8.91 | 7.16–9.35 | 5.82–7.73 | 5.84–7.60 | 5.76–7.66 | 6.34–8.39 | 6.05–8.14 | 6.05–8.14 |

| correlation coefficient | 0.93 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.95 |

| P value | <0.0001 | 0.0026 | 0.0023 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0007 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: S-RBD, spike protein receptor binding domain; GMT, geometric mean titer; BAU, binding antibody units; CI, confidence interval; GMFR, geometric mean fold rise.

The correlation between the two antibody titers was determined by Pearson's correlational analysis.

Fig. 2.

Linear regression for Roche and Abbott S-RBD antibody titers after each vaccination. The dotted lines are the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the regression lines. n, number; w, weeks.

SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD assays have been and are still widely used for serological studies. There has been a need for quantitative data on the immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and, ideally, to find protection correlates. In this prospective observational study, we confirmed and compared the longitudinal changes in SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD antibody titers after a fourth dose of mRNA-1273 (Moderna) following three doses of BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) among 16 HCWs using two commercially available automated immunoassays (Roche and Abbott). There is a concern that antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 may not be long-lasting. However, our data showed that antibody titers after the second vaccination were maintained above the detection cut-off during the long-term until the fourth vaccination. Our results appear in line with those reported previously [[8], [9], [10]]. These findings also confirm the efficacy of the assay types (ECLIA and CLIA used in this study), which have been reported to possess better diagnostic accuracy [11]. Despite the fact that the third vaccine was administered approximately 9 months after the second, and that the fourth vaccine was administered approximately 8 months after the third, the GMTs and GMFRs of SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD antibody detected by both assays increased dramatically. This strongly suggests that the immunogenicity elicited by the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine is maintained for a long time, indicating the effectiveness of the additional vaccination. On the other hand, the peak GMTs after the fourth vaccination detected by both assays were almost equal to, and slightly lower than, those after the third, with no significant difference between the two vaccines. This finding was consistent with results from the UK and Israel, indicating that there might be a ceiling or maximum S-RBD antibody titer [1,12]. Also, the GMFRs (9- to 15-fold) before and after the fourth dose in the UK and Israeli studies were higher than those (5- to 6-fold) found in our study [1,12]. This difference was due to the fact that our study participants maintained high S-RBD antibody titers before the fourth dose. Thus, individuals with high antibody titers before vaccination are unlikely to gain much of a booster effect from additional doses, and thus it might be possible to delay the timing of the booster. It is unclear how long the accumulated booster reaction will last. Further follow-up is needed to ascertain the effect of additional mRNA vaccination.

The GMTs and GMFRs for SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD antibody detected by the Roche assay were higher than those detected by the Abbott assay. In addition, the antibody ratio between the two assays increased over time. Thus, the antibody response detected by the Roche assay appeared to be larger and longer than that detected by the Abbott assay. This discrepancy may have been attributable to some differences between the two assays. First, the Roche assay may be more sensitive to qualitative changes than the Abbott assay because the former measures total antibodies including IgG, IgM and IgA whereas the latter measures only IgG antibody. Second, there may be a difference in the epitope of the S-RBD antibody that each assay recognizes. Third, there may be a difference in the assay types (ECLIA and CLIA). This type of discrepancy between the two assays has been similarly reported by Perkmann [8].

The strong correlation of the S-RBD antibody titer between the Roche and Abbott assays persisted during the study period, indicating the kinetic stability of the S-RBD antibody in both assays. A previous study of neutralizing antibody and S-RBD antibody found an optimal cut-off of 10,300 BAU/ml for the Roche assay against the Omicron variant, with 67.2% sensitivity and 90.6% specificity [13]. In contrast, the antibody titer measured by the Abbott assay giving approximately 95% effectiveness in preventing infection is considered to be cut-off of 590 BAU/ml, based on correlation with the plaque reduction neutralization test [14]. Interestingly, at 16 weeks after the third vaccination (the Omicron variant being dominant in Japan) in our study, the antibody titer (9710 BAU/mL, 95% CI 5382–17,516) measured by the Roche assay suggested the possibility of infection risk, but the antibody titer (1503, 846–2668) measured by the Abbott assay did not. Of course, this result might imply that each method differentially predicts the degree of infection risk. This discrepancy in the interpretation of antibody titers between the two assays might imply that the results are not necessarily reliable for control of COVID-19 infection. Thus, it is meaningful that we have obtained sequential data from the same individuals using different assays.

The main strength of this study was that it involved long-term observation of antibody titers after COVID-19 mRNA vaccinations and side-by-side evaluation using two different immunoassays. Study limitations included a small sample size, and the homogeneous demographic characteristics of the HCWs, who were relatively young and healthy, which would have potentially limited the generalizability of our findings. Moreover, we assessed only anti-S-RBD IgG levels, and not neutralizing antibodies and cellular immunity.

In conclusion, we have examined the long-term transition of S-RBD antibody titers measured by the Roche and Abbott immunoassays following the first to fourth mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in healthcare workers. The data were have obtained will be important for interpretation of future studies and for consideration of vaccination strategies based on SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD antibody levels.

Authorship statement

All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria. KS and YT drafted the article. KS was the chief investigator and responsible for the data analysis. All authors contributed to the writing of the final manuscript. All authors critically revised the report, commented on drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final report.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank the HCW volunteers who donated their blood at Ehime University Hospital. The work was supported by a donation from Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank.

References

- 1.Munro A.P.S., Feng S., Janani L., Cornelius V., Aley P.K., Babbage G., et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines given as fourth-dose boosters following two doses of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 or BNT162b2 and a third dose of BNT162b2 (COV-BOOST): a multicentre, blinded, phase 2, randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(8):1131–1141. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Beltran W.F., Lam E.C., Astudillo M.G., Yang D., Miller T.E., Feldman J., et al. COVID-19-neutralizing antibodies predict disease severity and survival. Cell. 2021;184(2):476–488.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkmann T., Perkmann-Nagele N., Koller T., Mucher P., Radakovics A., Marculescu R., et al. Anti-spike protein assays to determine SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels: a head-to-head comparison of five quantitative assays. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9(1) doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00247-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujigaki H., Inaba M., Osawa M., Moriyama S., Takahashi Y., Suzuki T., et al. Comparative analysis of antigen-specific anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody isotypes in COVID-19 patients. J Immunol. 2021;206(10):2393–2401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2001369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knezevic I., Mattiuzzo G., Page M., Minor P., Griffiths E., Nuebling M., et al. WHO International Standard for evaluation of the antibody response to COVID-19 vaccines: call for urgent action by the scientific community. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(3):e235–e240. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujigaki H., Yamamoto Y., Koseki T., Banno S., Ando T., Ito H., et al. Antibody responses to BNT162b2 vaccination in Japan: monitoring vaccine efficacy by measuring IgG antibodies against the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(1) doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01181-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikezaki H., Nomura H., Shimono N. Dynamics of anti-Spike IgG antibody level after the second BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination in health care workers. J Infect Chemother. 2022;28(6):802–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2022.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perkmann T., Mucher P., Perkmann-Nagele N., Radakovics A., Repl M., Koller T., et al. The comparability of anti-spike SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests is time-dependent: a prospective observational study. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(1) doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01402-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangia A., Serra N., Cocomazzi G., Giambra V., Antinucci S., Maiorana A., et al. Cellular and humoral immune responses and breakthrough infections after two doses of BNT162b vaccine in healthcare workers (HW) 180 days after the second vaccine dose. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.847384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamayoshi S., Yasuhara A., Ito M., Akasaka O., Nakamura M., Nakachi I., et al. Antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 decline, but do not disappear for several months. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;32 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovac M., Risch L., Thiel S., Weber M., Grossmann K., Wohlwend N., et al. EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood for SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10(8):593. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10080593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regev-Yochay G., Gonen T., Gilboa M., Mandelboim M., Indenbaum V., Amit S., et al. Efficacy of a fourth dose of Covid-19 mRNA vaccine against Omicron. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(14):1377–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2202542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Beltran W.F., St Denis K.J., Hoelzemer A., Lam E.C., Nitido A.D., Sheehan M.L., et al. mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell. 2022;185(3):457–466.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbott Diagnostics. Architect SARS-COV-2 IgG II quant instructions for use, H18566R01. IL, USA: Abbott Diagnostics.