Abstract

Background:

This study aims to determine whether Hepatitis C (HCV) treatment improves health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) actively engaged in substance use, and which variables are associated with improving HRQL in patients with OUD during HCV treatment.

Methods:

Data are from a prospective, open-label, observational study of 198 patients with OUD or opioid misuse within 1 year of study enrollment who received HCV treatment with the primary endpoint of Sustained Virologic Response (SVR). HRQL was assessed using the Hepatitis C Virus Patient Reported Outcomes (HCV-PRO) survey, with higher scores denoting better HRQL. HCV-PRO surveys were conducted at Day 0, Week 12, and Week 24. A mixed-effects model investigated which variables were associated with changing HCV-PRO scores from Day 0 to Week 24.

Results:

Patients had a median age of 57 and were predominantly male (68.2%) and Black (83.3%). Most reported daily-or-more drug use (58.6%) and injection drug use (IDU) (75.8%). Mean HCV-PRO scores at Day 0 and Week 24 were 64.0 and 72.9, respectively. HCV-PRO scores at Week 24 improved compared with scores at Day 0 (8.7; p<0.001). Achieving SVR (10.4; p<0.001) and receiving medications for OUD (MOUD) at Week 24 (9.5; p<0.001) were associated with improving HCV-PRO scores. HCV-PRO scores increased at Week 24 for patients who experienced no decline in IDU frequency (8.1; p<0.001) or had a UDS positive for opioids (8.0; p<0.001) or cocaine (7.5; p=0.003) at Week 24.

Conclusion:

Patients with OUD actively engaged in substance use experience improvement in HRQL from HCV cure unaffected by ongoing substance use. Interventions to promote HCV cure and MOUD engagement could improve HRQL for patients with OUD.

Keywords: Patient Reported Outcome Measures; Opioid-Related Disorders; Quality of Life; Hepatitis C, Chronic; Mental Health

Introduction

Hepatitis C (HCV) infection remains a public health crisis despite recent advances in treatment. At the start of 2020, there were an estimated 56.8 million HCV infections globally (Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators, 2022), while in the United States, annual HCV infections are estimated to have risen from 24,700 in 2012 to 57,500 in 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Particularly at risk are individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD), who have a high prevalence of HCV infection resulting from injection drug use (IDU) (Degenhardt et al., 2017).

Although providers and insurance companies often deny HCV treatment with direct acting-antivirals (DAA) to patients who engage in substance use (Barua et al., 2015), studies have shown that patients with OUD engaging in IDU achieve high rates of HCV cure with DAA treatment (Grebely et al., 2018; Read et al., 2017; Scherz et al., 2018). Moreover, by co-locating HCV treatment with medications for OUD (MOUD), patients with OUD experience improved outcomes for both their OUD and HCV (Rosenthal et al., 2020; Severe et al., 2020).

Along with its hepatic and extrahepatic effects, HCV infection has been associated with a reduction in health-related quality of life (HRQL) (Whiteley et al., 2015), as measured by patient-reported outcomes (PRO) (Z. Younossi & Henry, 2015). Recently, major health organizations have put an emphasis on measuring HRQL. Health care insurers have used HRQL to evaluate various patient outcomes (Hanmer et al., 2022), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States has made measuring HRQL a goal of the Healthy Peoples 2020 initiative (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2022). One tool used for PRO measurements in patients infected with HCV is the Hepatitis C Virus Patient Reported Outcomes (HCV-PRO) survey, a self-administered survey designed for adults with chronic HCV infection that measures the psychological, physical, social, and role-functioning effects of HCV (Anderson, Baran, Dietz, et al., 2014).

Previous research using other PRO measurement tools has shown that HCV treatment with DAA is associated with improved HRQL, particularly in patients who achieve sustained virologic response (SVR) (Marcellin et al., 2017). Improvements in HRQL during HCV treatment have been shown in patients with OUD receiving MOUD (Dalgard et al., 2022; Schulte et al., 2020), including in those who engage in IDU and achieve SVR (Gormley et al., 2021). However, it is unknown whether HCV treatment improves HRQL in patients with OUD not receiving MOUD, or which variables are associated with improving HRQL in patients with OUD during HCV treatment. To answer these questions, we evaluated HCV-PRO survey data from the previously reported ANCHOR study (Rosenthal et al., 2020), which assessed a model of treatment providing HCV DAA therapy and optional co-located MOUD treatment for patients with OUD, recent opioid use, and chronic HCV.

Methods

Trial Design

ANCHOR was a prospective, open-label, observational study of patients with OUD and chronic HCV infection (Rosenthal et al., 2020). 198 patients diagnosed with OUD or opioid misuse within 1 year of study enrollment were treated with HCV DAA for 8-12 weeks, with the primary endpoint of SVR. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or breastfeeding, had decompensated liver disease, or had contraindications to receiving DAA.

After baseline assessments were completed at study enrollment, patients returned within 2 weeks to start DAA. The day of DAA initiation was designated Day 0, and patients were seen for on-treatment visits at Weeks 4, 8, and 12 after Day 0. At Week 24, patients were assessed for SVR, defined as having an undetectable HCV RNA level 12 weeks after receiving the last dose of DAA. Patients not receiving MOUD at study enrollment could initiate buprenorphine at any time during the study. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Maryland, and all procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines. Patients gave their informed consent to participate in ANCHOR.

Study Visits and Assessments

Baseline Assessments

At study enrollment, the patient’s demographics, medications, substance use history, IDU history, substance use treatment history, social history, and self-reported history of mental illness were recorded. OUD severity was assessed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) OUD criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). OUD scores can range from 0 to 11, with higher scores denoting more severe OUD. MOUD status was assessed by asking patients whether they were receiving MOUD.

Substance Use Behavior and MOUD

IDU was assessed with the Darke HIV Risk-Taking Behavior Survey (Darke et al., 1991), a validated survey containing six questions that rate IDU behavior, at Day 0, Week 12, and Week 24. Decline in IDU was obtained by measuring changes in IDU frequency—categorized as either daily or more, less than daily, or none—from Day 0 to Week 24. If IDU was not recorded at Week 24, then decline in IDU was obtained by measuring changes in IDU frequency from Day 0 to Week 12. Decline in IDU was categorized into two groups: increase or no change in IDU frequency and decrease in IDU frequency.

Severity of alcohol use was assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C), a 3-item screening questionnaire for alcohol consumption that has been validated for identifying hazardous alcohol use and alcohol use disorder (Bush et al., 1998), at Day 0 and Week 24. A urine drug screen (UDS) was obtained to determine if it was positive or negative for non-prescribed opioids; positive or negative for cocaine; and positive or negative for substances besides non-prescribed opioids and cocaine including amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and phencyclidine (PCP). The first UDS was obtained either at the baseline visit or Day 0, after which UDSs were obtained at Week 12 and Week 24. MOUD status was assessed at Day 0, Week 12, and Week 24.

HCV-PRO Survey

HRQL during HCV treatment was assessed using the HCV-PRO survey. The HCV-PRO survey has been validated in patients who are receiving or have completed HCV treatment (Anderson, Baran, Erickson, et al., 2014). The HCV-PRO score is calculated from 16 items that rate specific symptoms on a five-point scale. The total score can range from 0 to 100, with higher scores denoting greater HRQL and better functioning. The HCV-PRO survey was administered at Day 0, Week 12, and Week 24.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were reported using numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were reported using either means with standard deviations or, when appropriate, medians with quartiles, after assessing normality using Q-Q plots and Shapiro Wilk’s tests. Means for HCV-PRO scores by demographic at baseline, Day 0, Week 12, and Week 24 were obtained using either an independent t test or Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) when appropriate. Associations between categorical variables were examined using either a Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. The effects of different variables on HCV-PRO scores were estimated using a linear mixed effects model. Variables at baseline (age, gender, history of mental illness, and HIV status) and at Week 24 (achieving SVR, decline in IDU, receiving MOUD, UDS positive for opioids, and UDS positive for cocaine) were considered in the linear mixed effects model. Subject effect was considered as the random effect. The linear mixed effects model was used to determine associations between the outcome variable HCV-PRO scores, the variables included in the model, and the effect of time. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp), STATA (Stata Corp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC) and SAS (SAS Institute Inc 2013. SAS/ACCESS® 9.4 Interface to ADABAS: Reference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.). A p-value of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance, and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to report results.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Demographics

Demographics for the 198 patients enrolled in ANCHOR are listed in Table 1. The median age was 57 years (range 29-72 years), and patients were predominantly male (68.2%) and Black (83.3%). Most were unstably housed (55.1%), received some form of income (56.1%), completed at least a high school level of education (59.6%), and reported a history of incarceration (89.4%). Very few (6.6 %) were co-infected with HIV.

Table 1:

Demographics

| Characteristic | Number of Patients |

|---|---|

| Total | 198 [100]a |

| Age, median (Q1,Q3), years | 57 (52,61) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 135 [68.2] |

| Female | 63 [31.8] |

| Race | |

| Black | 165 [83.3] |

| White | 26 [13.1] |

| Alaska Native or Native American | 1 [0.5] |

| More than one race | 4 [2] |

| Other | 2 [1] |

| Housing | |

| Stable | 89 [44.9] |

| Unstable | 109 [55.1] |

| Income | |

| Yes | 111 [56.1] |

| No | 87 [43.9] |

| Level of education | |

| High school or more | 118 [59.6] |

| Less than high school | 80 [40.4] |

| History of incarceration | |

| Never incarcerated | 13 [6.6] |

| Within 1 year | 23 [11.6] |

| More than 1 year | 154 [77.8] |

| Missingb | 8 [4] |

| HIV status | |

| Positive | 13 [6.6] |

| Negative/Unknown | 185 [93.4] |

| History of mental illness | |

| Yes | 118 [59.6] |

| No | 68 [34.3] |

| Missing | 12 [6.1] |

| Engaged in mental health treatment | |

| Yes | 26 [13.1] |

| No | 33 [16.7] |

| Missing | 139 [70.2] |

| Psychiatric diagnoses | |

| Depressive disorders | 55 [27.8] |

| Bipolar disorders | 47 [23.7] |

| Anxiety disorders | 36 [18.2] |

| Trauma-related disorders | 19 [9.6] |

| Psychotic-spectrum disorders | 12 [6.1] |

| Sleep-related disorders | 3 [1.5] |

| Personality disorders | 2 [1] |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity Disorder | 1 [0.5] |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1 [0.5] |

| Other | 1 [0.5] |

| Prescribed psychotropic medications | |

| Yes | 70 [35.4] |

| No | 127 [64.1] |

| Missing | 1 [0.5] |

| Classes of psychotropic medications | |

| Antidepressants | 42 [21.2] |

| Antipsychotics | 34 [17.2] |

| Anxiolytics | 32 [16.2] |

| Sleep aids | 14 [7.1] |

| Mood stabilizers | 11 [5.6] |

| Stimulants | 2 [1] |

| OUD score, median (Q1,Q3) | 10 (7,11) |

| Hazardous alcohol use | |

| Yes | 70 [35.4] |

| No | 128 [64.6] |

| Drug usec within the past 3 months | |

| Daily or more | 116 [58.6] |

| Less than daily | 73 [36.9] |

| None within the past 3 months | 9 [4.5] |

| Injection drug use | |

| Within 3 months | 150 [75.8] |

| Within 3-12 months | 7 [3.5] |

| None within 12 months | 41 [20.7] |

| Injection drug use in the last month | |

| Daily or more | 60 [30.3] |

| Less than daily | 62 [31.3] |

| None in the last month | 76 [38.4] |

| Opioids in urine drug results | |

| Yes | 151 [76.3] |

| No | 40 [20.2] |

| Missing | 7 [3.5] |

| Cocaine in urine drug results | |

| Yes | 104 [52.5] |

| No | 87 [43.9] |

| Missing | 7 [3.5] |

| Other drugsd in urine drug results | |

| Yes | 26 [13.1] |

| No | 165 [83.3] |

| Missing | 7 [3.5] |

| Medication for opioid agonist therapy | |

| Methadone | 77 [38.9] |

| Buprenorphine | 31 [15.7] |

| Not currently prescribed | 90 [45.5] |

Abbreviations: Q1,Q3: first quartile, third quartile

Percent of patients who gave a response in each subgroup

Data not available

Excludes marijuana

Includes amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, phencyclidine

Substance Use

At baseline, the median OUD score was 10, indicating severe OUD. In the 3-month period preceding study enrollment, 58.6% of patients reported using drugs daily or more, 36.9% reported using drugs less than daily, and 4.5% reported using no drugs. The vast majority (75.8%) reported IDU within the past three months, nearly a third (30.3 %) engaged in daily IDU during the previous month, and more than half (54.5%) were receiving MOUD. At Day 0, approximately a third (35.4%) met criteria for hazardous alcohol use based on the AUDIT-C questionnaire. Of the 191 patients who had a UDS at Day 0, 76.3 % had a UDS positive for opioids, 52.5% had a UDS positive for cocaine, and 13.1 % had a UDS positive for other substances besides non-prescribed opioids and cocaine.

Mental Health

At baseline, most patients (59.6 %) reported a history of mental illness. Patients reported receiving diagnoses of depressive disorders (27.8%), bipolar disorders (23.7%), anxiety disorders (18.2%), trauma-related disorders (9.6%), and psychotic-spectrum disorders (6.1%). Approximately a third (35.4%) reported taking psychotropic medications. While data regarding mental health engagement were not documented for most (70.2%) patients, 13.1% reported engagement in mental health treatment.

HCV-PRO Scores

HCV-PRO Scores at Day 0

The mean HCV-PRO score at Day 0 was 64.0 (±20.6). HCV-PRO scores at Day 0 were higher for males (p=0.006), those with at least a high school level of education (p=0.017), those without a history of mental illness (p<0.001), those engaged in mental health treatment (p=0.023), and those not prescribed psychotropic medications (p=0.010) (Supplemental Table 1).

Individual Items of HCV-PRO During HCV Treatment

As shown in Table 2, there was a significant increase in scores for 13 of the 16 items of the HCV-PRO from Day 0 to Week 24. Almost all the increase in scores occurred between Day 0 and Week 12.

Table 2:

Changes in Mean Scores of HCV-PRO Items Over 24 Weeks

| HCV-PRO Item | Change in Mean from Day 0 to Week 12 |

P Value | Change in Mean from Day 0 to Week 24 |

P Value | Change in Mean from Week 12 to Week 24 |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I felt too tired during the day to get done what I needed | +0.50 | <0.001 | +0.58 | <0.001 | +0.01 | 0.907 |

| I needed to pace myself to finish what I had planned | +0.26 | 0.035 | +0.27 | 0.030 | −0.01 | 0.918 |

| I felt forced to spend time in bed | +0.05 | 0.661 | +0.25 | 0.028 | +0.23 | 0.045 |

| My muscles felt weak | +0.49 | <0.001 | +0.39 | <0.001 | −0.05 | 0.669 |

| I could not get comfortable during the day | +0.48 | <0.001 | +0.67 | <0.001 | +0.14 | 0.211 |

| I was unable to think clearly or focus on my thoughts | +0.49 | <0.001 | +0.43 | <0.001 | −0.03 | 0.776 |

| I was forgetful | +0.26 | 0.024 | +0.33 | 0.002 | −0.03 | 0.815 |

| Having hepatitis C affected my sex life | +0.06 | 0.631 | +0.12 | 0.321 | +0.05 | 0.617 |

| I felt bothered by pain or physical discomfort | 0.13 | 0.283 | +0.18 | 0.175 | 0.12 | 0.420 |

| I found it hard to meet people or make new friends because of my hepatitis C | +0.20 | 0.004 | +0.12 | 0.105 | −0.03 | 0.629 |

| Having hepatitis C was very stressful to me | +0.59 | <0.001 | +0.58 | <0.001 | −0.08 | 0.474 |

| I felt downhearted and sad | +0.49 | <0.001 | +0.50 | <0.001 | +0.03 | 0.829 |

| I felt restless or on edge | +0.25 | 0.022 | +0.29 | 0.014 | +0.09 | 0.394 |

| I felt little interest in doing things | +0.29 | 0.011 | +0.31 | 0.008 | +0.03 | 0.785 |

| I had difficulty sleeping or slept too much | +0.31 | 0.024 | +0.38 | 0.004 | +0.09 | 0.550 |

| Hepatitis C lowered my quality of life | +0.44 | <0.001 | +0.39 | 0.001 | −0.03 | 0.769 |

HCV-PRO Scores at Week 24

Most participants (83.3 %) remained in the study at Week 24. Patients who did not remain in the study at Week 24 (16.7%) were more likely to lack stable housing (p=0.034) and less likely to report a history of incarceration (p=0.044) at baseline. They were also more likely to have a UDS positive for cocaine (p=0.018) and a UDS positive for substances other than non-prescribed opioids and cocaine (p=0.018) at Day 0 (Supplemental Table 2).

For the 165 patients who remained in the study at Week 24, the mean HCV-PRO score was 72.9 (±20.4), which was higher than their mean score at Day 0 (63.8; p<0.001). As shown in the paired t-tests listed in Table 3, most subgroups had HCV-PRO scores that were higher at Week 24 than Day 0.

Table 3:

Comparison of HCV-PRO Scores at Baseline and Week 24 for Patients Who Remained in the Study at Week 24

| Variables Recorded at Baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Numbera | HCV-PRO Score (SD) at Baseline |

HCV-PRO Score (SD) at Week 24 |

P Value |

| Total | 165 | 63.8 (±20.3) | 72.9 (±20.4) | <0.001 |

| Gender | 165 | |||

| Male | 115 | 66.4 (±20.9) | 74.4 (±19.3) | <0.001 |

| Female | 50 | 57.8 (±17.4) | 69.5 (±22.5) | 0.002 |

| Race | 165 | |||

| Black | 141 | 64.1 (±20.7) | 73.4 (±20.4) | <0.001 |

| Non-Black | 24 | 62.2 (±17.9) | 70.1 (±20.7) | 0.088 |

| Housing | 165 | |||

| Stable | 80 | 64.0 (±21.8) | 75.3 (±19.6) | <0.001 |

| Unstable | 85 | 63.7 (±18.9) | 70.6 (±20.9) | <0.001 |

| Income | 165 | |||

| Yes | 95 | 66.0 (±20.5) | 75.2 (±20.2) | <0.001 |

| No | 70 | 60.8 (±19.7) | 69.8 (±20.4) | 0.001 |

| Level of education | 165 | |||

| High school or more | 99 | 67.0 (±19.7) | 76.1 (±19.2) | <0.001 |

| Less than high school | 66 | 59.1 (±20.3) | 68.1 (±21.3) | <0.001 |

| History of incarceration | 157 | |||

| Never incarcerated | 8 | 59.8 (±24.4) | 70.5 (±26.6) | 0.385 |

| Within 1 year | 17 | 69.4 (±14.0) | 71.9 (±19.8) | 0.662 |

| More than 1 year | 132 | 62.9 (±20.9) | 72.3 (±20.4) | <0.001 |

| HIV status | 165 | |||

| Positive | 9 | 65.3 (±25.5) | 72.7 (±21.6) | 0.349 |

| Negative/Unknown | 156 | 63.7 (±20.0) | 72.9 (±20.4) | <0.001 |

| History of mental illness | 156 | |||

| Yes | 95 | 58.8 (±20.4) | 68.7 (±20.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 61 | 71.0 (±17.7) | 79.4 (±17.4) | <0.001 |

| Engaged in mental health treatment | 49 | |||

| Yes | 22 | 70.4 (±20.7) | 76.9 (±14.3) | 0.200 |

| No | 27 | 58.0 (±18.8) | 66.2 (±25.3) | 0.085 |

| Prescribed psychotropic medications | 164 | |||

| Yes | 55 | 60.5 (±19.2) | 68.8 (±17.6) | 0.006 |

| No | 109 | 65.5 (±20.8) | 74.9 (±21.5) | <0.001 |

| Drug use within the past 3 months | 165 | |||

| Daily or more | 93 | 62.6 (±20.1) | 71.2 (±20.6) | <0.001 |

| Less than daily | 66 | 65.2 (±20.9) | 74.8 (±20.1) | <0.001 |

| None within the past 3 months | 6 | 67.5 (±18.0) | 78.1 (±20.2) | 0.135 |

| Injection drug use | 165 | |||

| Within 3 months | 126 | 63.7 (±20.8) | 72.1 (±21.0) | <0.001 |

| Within 3-12 months | 6 | 62.8 (±11.6) | 78.4 (±13.7) | 0.011 |

| None within the past 12 months | 33 | 64.3 (±19.8) | 74.9 (±19.3) | 0.004 |

| Injection drug use in the last month at Day 0 | 165 | |||

| Daily or more | 48 | 63.0 (±20.4) | 70.4 (±19.9) | 0.009 |

| Less than daily | 52 | 63.0 (±20.9) | 71.7 (±22.6) | 0.005 |

| None in the last month | 65 | 65.1 (±19.9) | 75.7 (±18.8) | <0.001 |

| Injection drug use in the last month at Week 24 | 163 | |||

| Daily or more | 23 | 59.8 (±21.7) | 63.5 (±20.2) | 0.462 |

| Less than daily | 40 | 63.1 (±20.0) | 67.38 (±22.0) | 0.178 |

| None in the last month | 100 | 65.0 (±20.2) | 77.2 (±18.6) | <0.001 |

| Hazardous alcohol use at Day 0 | 165 | |||

| Yes | 58 | 62.9 (±17.4) | 72.4 (±20.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 107 | 64.3 (±21.7) | 73.2 (±20.2) | <0.001 |

| Hazardous alcohol use at Week 24 | 164 | |||

| Yes | 41 | 63.2 (±19.6) | 70.2 (±24.6) | 0.065 |

| No | 123 | 64.1 (±20.6) | 74.0 (±18.8) | <0.001 |

| Opioids in urine drug results at Day 0 | 160 | |||

| Yes | 125 | 63.2 (±20.2) | 71.2 (±20.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 35 | 67.5 (±21.4) | 79.3 (±18.2) | <0.001 |

| Opioids in urine drug results at Week 24 | 156 | |||

| Yes | 109 | 62.4 (±20.3) | 70.3 (±20.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 47 | 69.3 (±17.9) | 79.5 (±18.3) | 0.001 |

| Cocaine in urine drug results at Day 0 | 160 | |||

| Yes | 81 | 63.7 (±20.3) | 71.6 (±21.0) | <0.001 |

| No | 79 | 64.6 (±20.7) | 74.4 (±20.0) | <0.001 |

| Cocaine in urine drug results at Week 24 | 156 | |||

| Yes | 79 | 61.5 (±19.5) | 69.0 (±21.7) | 0.002 |

| No | 77 | 67.6 (±19.7) | 77.2 (±18.3) | <0.001 |

| Other drugs in urine drug results at Day 0 | 160 | |||

| Yes | 17 | 59.5 (±20.3) | 69.0 (±20.8) | 0.117 |

| No | 143 | 64.7 (±20.5) | 73.4 (±20.5) | <0.001 |

| Other drugs in urine drug results at Week 24 | 156 | |||

| Yes | 16 | 60.9 (±16.3) | 57.0 (±19.9) | 0.519 |

| No | 140 | 64.9 (±20.1) | 74.9 (±19.8) | <0.001 |

| Medication for opioid agonist therapy at Day 0 | 165 | |||

| Yes | 101 | 62.7 (±19.4) | 73.7 (±20.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 64 | 65.6 (±21.7) | 71.7 (±20.9) | 0.022 |

| Medication for opioid agonist therapy at Week 24 | 165 | |||

| Yes | 133 | 62.9 (±20.0) | 73.0 (±20.0) | <0.001 |

| No | 32 | 67.8 (±21.2) | 72.5 (±22.1) | 0.265 |

| Achieved SVR at Week 24b | 165 | |||

| Yes | 146 | 63.6 (±20.2) | 74.1 (±19.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 19 | 65.6 (±21.3) | 64.1 (±24.7) | 0.810 |

Abbreviations: SD: standard deviation; SVR: sustained virologic response

Only included patients who provided a response

Only obtained at Week 24

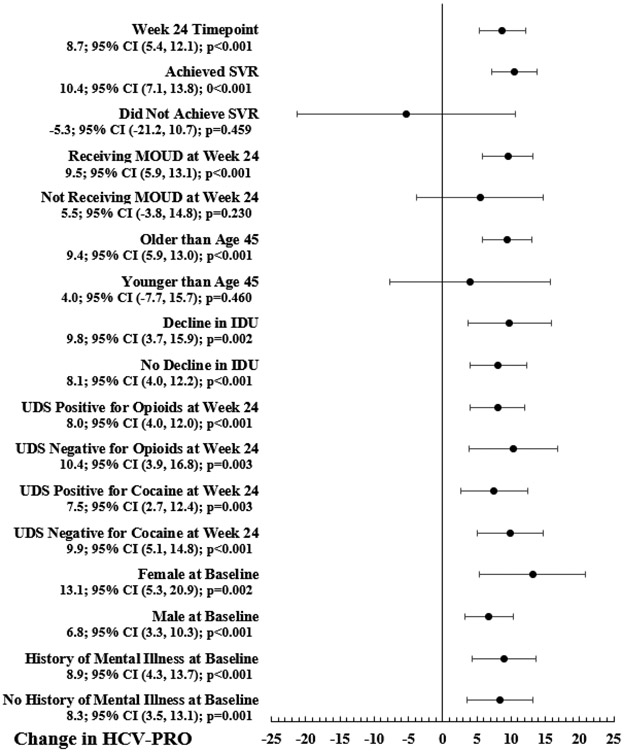

Change in HCV-PRO Scores from the Day 0 to Week 24 Timepoint

A mixed effects model measured the change in HCV-PRO scores from the Day 0 to Week 24 timepoint. 147 patients met criteria for inclusion in the model. Figure 1 shows the changes in HCV-PRO scores for each variable included in the model. Compared with the Day 0 timepoint, the Week 24 timepoint was associated with a significant increase in HCV-PRO scores (N=147; 8.7; 95% CI 5.4, 12.1; p<0.001).

Figure 1: Change in HCV-PRO Scores from the Day 0 to Week 24 Timepoint for Variables Included in the Mixed Effects Model.

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; SVR: sustained virologic response; MOUD: medication for opioid use disorder; IDU: injection drug use; UDS: urine drug screen

*HIV status at baseline is not shown in Figure 1 because there were too few patients whose HIV status was positive to include them in the mixed effects model

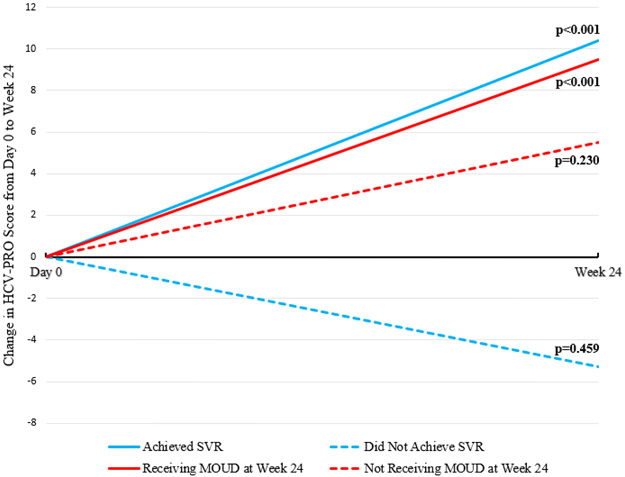

As shown in Figure 2, significant increases in HCV-PRO scores were associated with achieving SVR (N=131; 10.4; 95% CI 7.1, 13.8; p<0.001) and receiving MOUD at Week 24 (N=118; 9.5; 95% CI 5.9, 13.1; p<0.001). There was no significant change in HCV-PRO scores associated with not achieving SVR (N=16; −5.3; 95% CI −21.2, 10.7; p=0.459) or not receiving MOUD at Week 24 (N=29; 5.5; 95% CI −3.8, 14.8; p=0.230). Age older than 45 was associated with a significant increase in HCV-PRO scores (N=128; 9.4; 95% CI 5.9, 13.0; p<0.001), but age younger than 45 was not associated with a change in HCV-PRO scores (N=19; 4.0; 95% CI −7.7, 15.7; p=0.460).

Figure 2: Change in HCV-PRO Scores from the Day 0 to Week 24 Timepoint by SVR and MOUD Status.

Abbreviations: SVR: sustained virologic response; MOUD: medication for opioid use disorder *p values denote the significance of the increase in HCV-PRO scores from the Day 0 to Week 24 timepoint

Other variables associated with increases in HCV-PRO scores were decline (N=53; 9.8; 95% CI 3.7, 15.9; p=0.002) and increase or no change in IDU frequency (N=94; 8.1; 95% CI 4.0, 12.2; p<0.001); UDS positive (N=103; 8.0; 95% CI 4.0, 12.0; p<0.001) and negative (N=44; 10.4; 95% CI 3.9, 16.8; p=0.003) for opioids at Week 24; UDS positive (N=75; 7.5; 95% CI 2.7, 12.4; p=0.003) and negative (N=72; 9.9; 95% CI 5.1, 14.8; p<0.001) for cocaine at Week 24; females (N=45; 13.1; 95% CI 5.3, 20.9; p=0.002) and males (N=102; 6.8; 95% CI 3.3, 10.3; p<0.001) at baseline; history of mental illness (N=88; 8.9; 95% CI 4.3, 13.7; p<0.001) and no history of mental illness (N=59; 8.3; 95% CI 3.5, 13.1; p=0.001) at baseline; and HIV status negative or unknown at baseline (N=142; 8.7; 95% CI 5.3, 12.1; p<0.001). The model only included 5 patients whose HIV status was positive at baseline, which were too few for measuring the change in HCV-PRO score for this variable.

Discussion

In this cohort of predominantly middle-aged patients with OUD actively engaged in substance use, we found that HRQL improved after receiving DAA for HCV treatment, but it did not improve in those who did not achieve SVR, were not receiving MOUD at Week 24, or were younger than age 45. Critically, ongoing substance use factors at the Week 24 timepoint such as IDU frequency and UDS results for opioids and cocaine did not negate the HRQL improvements associated with achieving SVR. These findings strengthen the evidence for offering HCV treatment to patients with OUD regardless of whether they continue to use non-prescribed substances, and it reinforces that abstinence should not be a prerequisite for receiving HCV treatment.

Unlike previous studies of HRQL, in which only patients receiving MOUD or stabilized in substance use treatment were included (Dalgard et al., 2022; Gormley et al., 2021; Schulte et al., 2020), the majority of patients in ANCHOR were patients with severe OUD and active IDU who had lower baseline HCV-PRO scores than patients in other studies (Ahn et al., 2020; Anderson, Baran, Erickson, et al., 2014; Castelo et al., 2018; Evon et al., 2018). At screening, slightly less than half of patients were not receiving MOUD, and although buprenorphine could be initiated at any time during HCV treatment, a fifth of the patients remaining at the end of the study were not receiving MOUD. For these reasons, our analysis can demonstrate that HCV treatment is associated with an improvement in HRQL in patients with OUD actively engaged in substance use except for those not receiving MOUD or who do not achieve SVR.

While previous studies investigated HRQL only in patients with OUD who achieved SVR (Dalgard et al., 2022; Gormley et al., 2021), over a tenth of the patients in ANCHOR did not achieve SVR. Our results show that in this population with severe OUD who engage in IDU, SVR was associated with improved HRQL, whereas patients who did not achieve SVR experienced no improvement in HRQL. These findings are both logical, since clearing HCV should resolve the physical and neuropsychiatric impairments responsible for worsening HRQL, and consistent with previous studies measuring HRQL in patient populations with HCV who do not engage in IDU (Fagundes et al., 2020; Saeed et al., 2020; Smith-Palmer et al., 2015; Z. M. Younossi et al., 2014, 2020).

Our results also show that receiving MOUD at Week 24 was associated with an improvement in HRQL, whereas not receiving MOUD at Week 24 was not associated with an improvement in HRQL. These results add to the growing literature of MOUD studies showing that MOUD improves HRQL in OUD patients actively engaged in IDU (Bråbäck et al., 2018; Nosyk et al., 2011), patients stabilized on MOUD experience an improvement in HRQL from HCV treatment (Dalgard et al., 2022; Gormley et al., 2021; Schulte et al., 2020), and providing MOUD during HCV treatment benefits patients with OUD (Rosenthal et al., 2020).

It is notable that HRQL improved for females and those with a history of mental illness, despite HCV-PRO scores being lower at baseline for both groups. Like substance use outcomes in our study, history of mental illness and female gender at baseline did not negate the impact of HCV cure on HRQL during HCV treatment. This highlights how robust the benefits of HCV treatment are even for vulnerable populations and emphasizes how crucial it is to increase the availability of HCV treatment.

One unexpected finding is that those younger than age 45 did not experience a significant improvement in HRQL from HCV treatment. The median age for patients in ANCHOR was 57, and only 19 patients younger than age 45 were included in the mixed effects model. As a result, the sample size in our study may be too low to make meaningful conclusions about how age affects HRQL in patients with OUD receiving HCV treatment.

Finally, our paper addresses a gap in the literature about the cost-effectiveness of HCV treatment for OUD patients. Decisions to treat HCV should account for outcomes other than HCV cure, including changes in HRQL. Information on how HCV treatment affects patients with OUD who engage in IDU can inform clinical decisions, identify areas of intervention, and persuade insurance companies to cover HCV treatment for this population. Previous research has shown that targeted screening of HCV in individuals who engage in IDU is a cost-effective strategy that could increase quality-adjusted life years and improve HCV outcomes (Tatar et al., 2020). Our results show that patients with OUD who engage in IDU not only respond robustly to HCV treatment as evidenced by HCV cure, but also experience subjective benefits from improved HRQL.

There are some limitations to our study. ANCHOR recruited patients from only two sites, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. The patient population enrolled in ANCHOR was predominantly older, Black, male, and urban, so the applicability of our findings to other subsets of the OUD population is limited. The data in ANCHOR were collected at only three timepoints and provided by self-report, which were not verified using other validated sources. There were only 198 patients enrolled in ANCHOR, though using a mixed effects model for our analysis partially addressed the limitations of our sample size. HCV-PRO scores were only measured for 24 weeks following the start of DAA therapy, so we cannot comment on the change in HRQL and the variables affecting it after Week 24.

Our data demonstrate that patients with OUD actively engaged in substance use experience an improvement in HRQL from receiving HCV treatment unaffected by substance use outcomes. This highlights how HCV treatment provides extrahepatic benefits even for patients who engage in substance use. However, this improvement was not seen in patients who did not achieve SVR or were not receiving MOUD at Week 24. These data reinforce the critical nature of treating and curing HCV in all patients, as well as the importance of making MOUD available to the OUD population. Finally, these data further solidify the large body of evidence showing that ongoing substance use should not prevent people from accessing HCV treatment.

Supplementary Material

Article Highlights.

Hepatitis C cure improves quality of life for opioid use disorder patients

Medications for opioid use disorder improve quality of life during treatment

Substance use outcomes during hepatitis C treatment did not negate quality of life

Patients using substances should not be refused hepatitis C treatment

Medications for opioid use disorder should be offered during hepatitis C treatment

Acknowledgments:

Research for this study was supported by the Office of AIDS Research (grant HHSN269201400012C); the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant R01DA043396-01Al); Gilead Sciences (investigator-initiated grant and drug donation); Merck (investigator-initiated grant and drug donation); and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health (Annual Report Number ZIAMH002922). Elana Rosenthal reports grants and nonfinancial support from Gilead Sciences and Merck to her institution. Sarah Kattakuzhy reports grants and nonfinancial support from Gilead Sciences to her institution. Shayamasundaran Kottilil reports grants and nonfinancial support from Gilead Sciences, grants and nonfinancial support from Merck, and grants from Arbutus Pharmaceuticals during the conduct of this study.

Funding sources

Research to conduct the ANCHOR study was supported by the Office of AIDS

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Credit Author Statement

Max Spaderna: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration

Sarah Kattakuzhy: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition

Sun Jung Kang: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration

Nivya George: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration

Phyllis Bijole: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Emade Ebah: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Rahwa Eyasu: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Onyinyechi Ogbumbadiugha: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Rachel Silk: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Catherine Gannon: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Ashley Davis: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Amelia Cover: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Britt Gayle: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Shivakumar Narayanan: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration

Maryland Pao: Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition

Shayamasundaran Kottilil: Writing – Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition

Elana Rosenthal: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition

Declaration of interests

Elana Rosenthal reports grants and nonfinancial support from Gilead Sciences and Merck to her institution. Sarah Kattakuzhy reports grants and nonfinancial support from Gilead Sciences to her institution. Shayamasundaran Kottilil reports grants and nonfinancial support from Gilead Sciences, grants and nonfinancial support from Merck, and grants from Arbutus Pharmaceuticals during the conduct of this study.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board (HP-00071577)

References

- Ahn SH, Choe WH, Kim YJ, Heo J, Latarska-Smuga D, Kang J, & Paik SW (2020). Impact of Interferon-Based Treatment on Quality of Life and Work-Related Productivity of Korean Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. Gut and Liver, 14(3), 368–376. 10.5009/gnl18100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RT, Baran RW, Dietz B, Kallwitz E, Erickson P, & Revicki DA (2014). Development and initial psychometric evaluation of the hepatitis C virus-patient-reported outcomes (HCV-PRO) instrument. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 23(2), 561–570. 10.1007/s11136-013-0505-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RT, Baran RW, Erickson P, Revicki DA, Dietz B, & Gooch K (2014). Psychometric evaluation of the hepatitis C virus patient-reported outcomes (HCV-PRO) instrument: Validity, responsiveness, and identification of the minimally important difference in a phase 2 clinical trial. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 23(3), 877–886. 10.1007/s11136-013-0519-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua S, Greenwald R, Grebely J, Dore GJ, Swan T, & Taylor LE (2015). Restrictions for Medicaid Reimbursement of Sofosbuvir for the Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(3), 215–223. 10.7326/M15-0406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bråbäck M, Brådvik L, Troberg K, Isendahl P, Nilsson S, & Håkansson A (2018). Health Related Quality of Life in Individuals Transferred from a Needle Exchange Program and Starting Opioid Agonist Treatment. Journal of Addiction, 2018, 3025683. 10.1155/2018/3025683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, & Bradley KA (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelo A, Mello CEB, Teixeira R, Madruga JVR, Reuter T, Pereira LMMB, Silva GF, Álvares-DA-Silva MR, Zambrini H, & Ferreira PRA (2018). HEPATITIS C IN THE BRAZILIAN PUBLIC HEALTH CARE SYSTEM: BURDEN OF DISEASE. Arquivos De Gastroenterologia, 55(4), 329–337. 10.1590/S0004-2803.201800000-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). 2019 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/Figure3.1.htm [Google Scholar]

- Dalgard O, Litwin AH, Shibolet O, Grebely J, Nahass R, Altice FL, Conway B, Gane EJ, Luetkemeyer AF, Peng C-Y, Iser D, Gendrano IN, Kelly MM, Haber BA, Platt H, Puenpatom A, & CO-STAR Investigators. (2022). Health-related quality of life in people receiving opioid agonist treatment and treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 1–12. 10.1080/10550887.2022.2088978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, Ward J, & Wodak A (1991). The reliability and validity of a scale to measure HIV risk-taking behaviour among intravenous drug users. AIDS (London, England), 5(2), 181–185. 10.1097/00002030-199102000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, Leung J, Grebely J, Vickerman P, Stone J, Cunningham EB, Trickey A, Dumchev K, Lynskey M, Griffiths P, Mattick RP, Hickman M, & Larney S (2017). Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: A multistage systematic review. The Lancet. Global Health, 5(12), e1192–e1207. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30375-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evon DM, Stewart PW, Amador J, Serper M, Lok AS, Sterling RK, Sarkar S, Golin CE, Reeve BB, Nelson DR, Reau N, Lim JK, Reddy KR, Di Bisceglie AM, & Fried MW (2018). A comprehensive assessment of patient reported symptom burden, medical comorbidities, and functional well being in patients initiating direct acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C: Results from a large US multi-center observational study. PloS One, 13(8), e0196908. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagundes RN, de Ferreira LEVVC, & de Pace FHL (2020). Health-related quality of life and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C with therapy with direct-acting antivirals agents interferon-free. PloS One, 15(8), e0237005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0237005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormley MA, Akiyama MJ, Rennert L, Howard KA, Norton BL, Pericot-Valverde I, Muench S, Heo M, & Litwin AH (2021). Changes in health-related quality of life for HCV-infected people who inject drugs on opioid agonist treatment following sustained virologic response. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, ciab669. 10.1093/cid/ciab669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebely J, Dalgard O, Conway B, Cunningham EB, Bruggmann P, Hajarizadeh B, Amin J, Bruneau J, Hellard M, Litwin AH, Marks P, Quiene S, Siriragavan S, Applegate TL, Swan T, Byrne J, Lacalamita M, Dunlop A, Matthews GV, … SIMPLIFY Study Group. (2018). Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): An open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. The Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 3(3), 153–161. 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30404-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanmer J, Cizik AM, Gulek BG, McCracken P, Swart ECS, Turner R, & Kinsky SM (2022). A scoping review of US insurers’ use of patient-reported outcomes. The American Journal of Managed Care, 28(6), e232–e238. 10.37765/ajmc.2022.89162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcellin F, Roux P, Protopopescu C, Duracinsky M, Spire B, & Carrieri MP (2017). Patient-reported outcomes with direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: Current knowledge and outstanding issues. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 11(3), 259–268. 10.1080/17474124.2017.1285227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Guh DP, Sun H, Oviedo-Joekes E, Brissette S, Marsh DC, Schechter MT, & Anis AH (2011). Health related quality of life trajectories of patients in opioid substitution treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2–3), 259–264. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2022). Health-Related Quality of Life & Well-Being. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/health-related-quality-of-life-well-being

- Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. (2022). Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: A modelling study. The Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 7(5), 396–415. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00472-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read P, Lothian R, Chronister K, Gilliver R, Kearley J, Dore GJ, & van Beek I (2017). Delivering direct acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C to highly marginalised and current drug injecting populations in a targeted primary health care setting. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 47, 209–215. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal ES, Silk R, Mathur P, Gross C, Eyasu R, Nussdorf L, Hill K, Brokus C, D’Amore A, Sidique N, Bijole P, Jones M, Kier R, McCullough D, Sternberg D, Stafford K, Sun J, Masur H, Kottilil S, & Kattakuzhy S (2020). Concurrent Initiation of Hepatitis C and Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in People Who Inject Drugs. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 71(1), 1715–1722. 10.1093/cid/ciaa105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed YA, Phoon A, Bielecki JM, Mitsakakis N, Bremner KE, Abrahamyan L, Pechlivanoglou P, Feld JJ, Krahn M, & Wong WWL (2020). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Utilities in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 23(1), 127–137. 10.1016/j.jval.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz N, Bruggmann P, & Brunner N (2018). Direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C infection among people receiving opioid agonist treatment or heroin assisted treatment. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 62, 74–77. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte B, Schmidt CS, Manthey J, Strada L, Christensen S, Cimander K, Görne H, Khaykin P, Scherbaum N, Walcher S, Mauss S, Schäfer I, Verthein U, Rehm J, & Reimer J (2020). Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes of Direct-Acting Antivirals for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Among Patients on Opioid Agonist Treatment: A Real-world Prospective Cohort Study. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 7(8), ofaa317. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severe B, Tetrault JM, Madden L, & Heimer R (2020). Co-Located hepatitis C virus infection treatment within an opioid treatment program promotes opioid agonist treatment retention. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 213, 108116. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Palmer J, Cerri K, & Valentine W (2015). Achieving sustained virologic response in hepatitis C: A systematic review of the clinical, economic and quality of life benefits. BMC Infectious Diseases, 15, 19. 10.1186/s12879-015-0748-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M, Keeshin SW, Mailliard M, & Wilson FA (2020). Cost-effectiveness of Universal and Targeted Hepatitis C Virus Screening in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2015756. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley D, Elliott L, Cunningham-Burley S, & Whittaker A (2015). Health-Related Quality of Life for individuals with hepatitis C: A narrative review. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 26(10), 936–949. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi Z, & Henry L (2015). Systematic review: Patient-reported outcomes in chronic hepatitis C--the impact of liver disease and new treatment regimens. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 41(6), 497–520. 10.1111/apt.13090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson I, Muir AJ, Pol S, Zeuzem S, Younes Z, Herring R, Lawitz E, Younossi I, & Racila A (2020). Not Achieving Sustained Viral Eradication of Hepatitis C Virus After Treatment Leads to Worsening Patient-reported Outcomes. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 70(4), 628–632. 10.1093/cid/ciz243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Zeuzem S, Dusheiko G, Esteban R, Hezode C, Reesink HW, Weiland O, Nader F, & Hunt SL (2014). Patient-reported outcomes assessment in chronic hepatitis C treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin: The VALENCE study. Journal of Hepatology, 61(2), 228–234. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.