SUMMARY

O-GlcNAc is a dynamic post-translational modification (PTM) that regulates protein functions. In studying the regulatory roles of O-GlcNAc, a major roadblock is the inability to change O-GlcNAcylation on a single protein at a time. Herein, we developed a dual RNA aptamer based approach that simultaneously targeted O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and β-catenin, the key transcription factor of the Wnt signaling pathway, to selectively increase O-GlcNAcylation of the latter without affecting other OGT substrates. Using the OGT/β-catenin dual-specificity aptamers, we found that O-GlcNAcylation of β-catenin stabilizes the protein by inhibiting its interaction with β-TrCP. O-GlcNAc also increases β-catenin’s interaction with EZH2, recruits EZH2 to promoters and dramatically alters the transcriptome. Further, by coupling riboswitches or an inducible expression system to aptamers, we enabled inducible regulation of protein-specific O-GlcNAcylation. Together, our findings demonstrate the efficacy and versatility of dual-specificity aptamers for regulating O-GlcNAcylation on individual proteins.

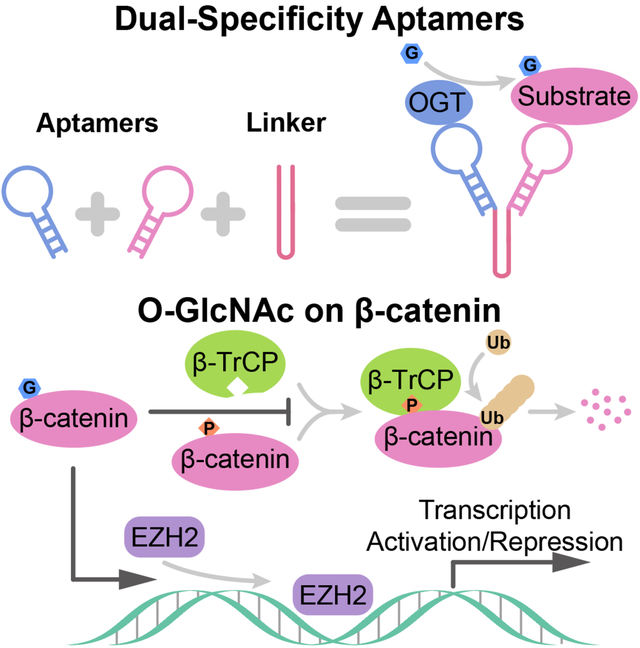

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Zhu and Hart report the development of dual-specificity RNA aptamers for altering O-GlcNAcylation of specific proteins; this work provides a versatile tool kit for studying an elusive post-translational modification.

INTRODUCTION

O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) is a post-translational modification (PTM) attached to serine and threonine residues of more than 8,000 human nucleocytoplasmic proteins1–3. O-GlcNAc is a highly dynamic PTM which is actively added and removed by two enzymes: O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), respectively4–7. As a fast-cycling, nutrient-sensitive PTM, O-GlcNAc regulates many signaling events, interplays with phosphorylation, and regulates protein functions such as intermolecular interactions and degradation. Abnormal O-GlcNAcylation is associated with many human diseases, including cancer and diabetes8.

With current approaches, it is difficult to study the biological functions of O-GlcNAc on a specific protein. OGT and OGA are the sole O-GlcNAc modifying enzymes, any chemical inhibitors or genetic approaches targeting them change O-GlcNAcylation on thousands of proteins simultaneously. O-GlcNAc and phosphate frequently modify the same or proximal sites in a mutually exclusive way. This crosstalk makes studies that use site-directed mutagenesis to convert serine or threonine to other non-modifiable residues difficult to interpret. Moreover, there is no amino acid mimic of O-GlcNAcylation, as there is for phosphorylation. The lack of tools to modify O-GlcNAcylation of a single protein without affecting the many others in the cell has substantially impeded our understanding of the functions of this ubiquitous and essential modification.

To address this problem, Pratt and others have used expressed protein ligation to study O-GlcNAc modified proteins in vitro9,10. In this method, a chemically synthesized, O-GlcNAc modified peptide is ligated to bacterial expressed, unmodified protein portions to generate a full-length protein with O-GlcNAc on certain sites. Proteins produced in this method are completely modified at defined sites but can only be used for in vitro assays. It also requires cysteine residues at the ligation sites. Woo and colleagues used nanobody-tagged OGT or OGA constructs to selectively modify O-GlcNAcylation of target proteins in cells11,12. However, the tight and stable binding of these antibodies to the target proteins make sorting out the biological effects of altered O-GlcNAcylation from the effects of the antibody binding difficult.

Wnt signaling plays essential roles in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and self-renewal of stem cells. Its abnormalities occur in many types of cancer and inheritable disorders13,14. β-catenin is the key transcription factor in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Its functions are regulated by PTMs. In resting cells, β-catenin maintains a low abundance due to the consecutive phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation15,16. Wnt signaling triggers a cascade of events that ultimately stabilizes β-catenin by inhibiting its ubiquitination, causing its nuclear accumulation and activation of downstream genes17. Besides phosphorylation and ubiquitination, the functions of β-catenin are regulated by PTMs including O-GlcNAcylation18.

Here, we developed an RNA-based method that induces protein-specific O-GlcNAcylation under endogenous levels of OGT and OGA, and studied how O-GlcNAc regulates β-catenin. Dual-specificity (DS) aptamers are modular designed RNA that connect two aptamer motifs with a linker domain. In cells, they induce proximity between OGT and a designated protein, and increase O-GlcNAcylation on the substrate. These RNA aptamers have short half-lives in cells and their binding can be controlled by riboswitches. Using DS aptamers, we induced O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-tagged and endogenous proteins and studied the regulatory roles of O-GlcNAc on β-catenin. O-GlcNAc regulates the interactions between β-catenin and a variety of proteins, including the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP, and the epigenetic modifiers EZH2, KAT2A, KAT5 and EP300. Particularly, O-GlcNAcylated β-catenin recruits EZH2 to promoters and shifts the transcriptome in a Wnt-dependent manner. Finally, by coupling riboswitches, or a Tet-On inducible expression system to DS aptamers, we deployed DS aptamers for inducible regulation of O-GlcNAcylation. Beyond O-GlcNAc, DS aptamers also provide us programable tools for the regulation of other PTMs and interactions in a cell.

RESULTS

A Noninhibiting RNA Aptamer Targeting ncOGT Was Generated From SELEX

Discovered in 1990, aptamers are short, single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that bind targets with high affinity and specificity. They have been selected to bind a wide variety of targets from metal ions, small organic molecules, proteins to whole cells19–22. Aptamers are generated from the in vitro selection named Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment (SELEX, Figure 1A), which is an iterative binding, partitioning and amplification process.

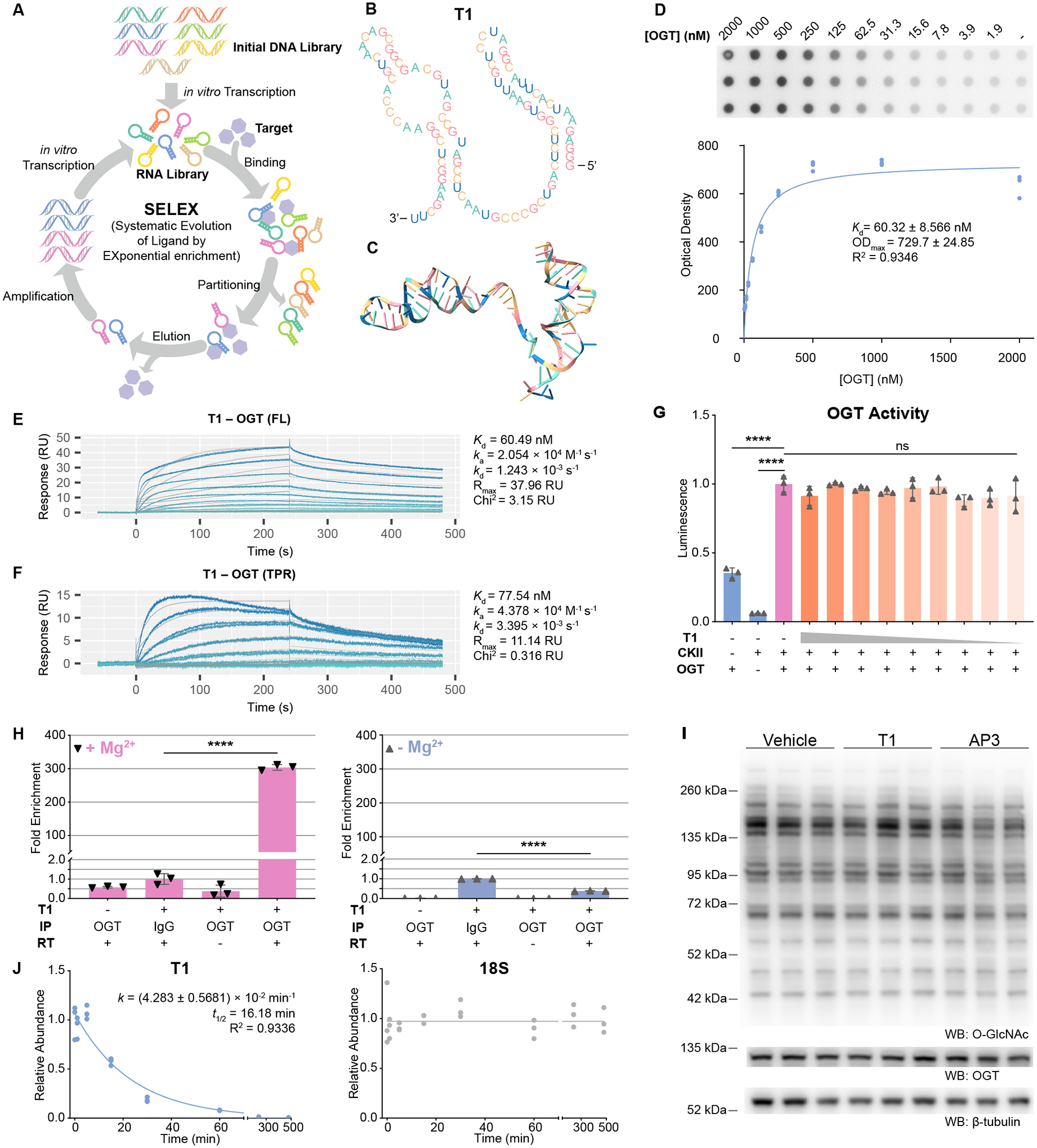

Figure 1. A Noninhibiting RNA Aptamer Targeting ncOGT Was Generated From SELEX.

(A) Schematic of SELEX.

(B) and (C) Predicted secondary (B) and tertiary (C) structures of T1. Nucleotides in the two panels are color coded in the same way.

(D) Radiolabeled Dot-Blot Assay measuring the binding affinity of T1 to full-length ncOGT. Data are fitted to a Michaelis-Menten model (curve).

(E) and (F) Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) characterizing the binding affinity and kinetics of T1 to full-length ncOGT (E), and to the TPR domain (F). Sensorgrams represent OGT concentrations from 1 μM to 977 pM (E) or 1 μM to 488 pM (F), in 2× serial dilutions. Data are fitted to a 1:1 binding model.

(G) UDP-Glo assay of OGT activity in the presence of T1. T1 was included in the indicated reactions (orange) from 2 μM to 7.8 nM in 2× serial dilution. Data are normalized to the positive control reaction (red). N=3.

(H) RNA-IP and RT-qPCR quantification of OGT-bound T1 in cells. OGT was immunoprecipitated from T1-expressing cells, using buffers with Mg2+ (left panel) or without Mg2+ (right panel). Then OGT-bound T1 was quantified by RT-qPCR. Data are normalized to the IgG groups. RT – Reverse Transcriptase. N=3.

(I). Western Blot (WB) analysis of global O-GlcNAcylation in HEK293T cells expressing T1 or AP3. N=3.

(J) Pulse-chase experiments on the half-life of T1 in cells. Cells stably expressing T1 were treated with ActD for the indicated periods. Abundance of T1 was quantified by RT-qPCR (left panel) and normalized to that of 18S rRNA (right panel) and initial timepoint (T=0). Data are fitted to a one-phase decay model (curve). N=3.

One-way ANOVA test in (G), (H). Data are represented as mean ± SD. ns, p ≥ 0.05; ****, p < 0.0001.

To regulate O-GlcNAcylation with DS aptamers, it is a prerequisite that we have a noninhibiting RNA aptamer targeting the nucleocytoplasmic isoform of OGT (ncOGT). Therefore, SELEX was performed. To generate aptamers that bind the non-catalytic domain of OGT, we switched the targets of SELEX between the full-length ncOGT and its tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain (STAR Methods)23. After 11 rounds of SELEX, the sequence T1 was highly enriched in the final RNA library (Figures 1B, 1C).

We validated T1 as a noninhibiting aptamer targeting ncOGT in vitro. Binding between T1 and ncOGT was confirmed in Radiolabeled Dot-Blot Assays (Figure 1D), and further characterized in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) (Figure 1E). In both experiments, the dissociation constant (Kd) was measured to be ~60 nM. SPR also shows that T1 recognizes the TPR domain of ncOGT (Figure 1F). To study if T1 inhibits the activity of the enzyme, we performed UDP-Glo OGT activity assays (Figure 1G). No inhibition was observed when T1 was included in the reactions from 7.8 nM to 2 μM, which was ~ 33 times higher than the Kd.

We further validated T1 in living cells. The binding between T1 and OGT in HEK293T cells was confirmed in RNA-IP experiments (Figure 1H). When expressed in cells, T1 was highly enriched on immunoprecipitated OGT protein. This binding requires Mg2+. In RNA-IP reactions containing no Mg2+, T1 was no longer enriched on OGT. The divalent Mg2+ ion facilitates RNA folding by shielding the negative charges on the RNA backbone24,25, and Mg2+ was included in the selection buffer in SELEX. In cells, expression of T1 did not change the global O-GlcNAcylation pattern or the abundance of OGT (Figure 1I). Moreover, in pulse-chase experiments with actinomycin D (ActD) treatment, we found T1 to have a short half-life (16.18 min) in cells. In contrast, 18S rRNA was stable during the 8-hr treatment (Figure 1J).

In conclusion, T1 is an RNA aptamer that binds OGT without inhibiting its enzymatic activity both in vitro and in cells. It is a short-lived RNA in cellular context.

Dual-Specificity Aptamers Increase O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-Tagged Proteins

Next, we conjoined T1 with AP3, an RNA aptamer of GFP26. In these DS aptamers, T1 and AP3 were connected by a linker region. We first designed a series of flexible linkers that were single-stranded, GC-neutral, and that did not interfere with the folding of T1 and AP3 (Figure 2A). Like the individual T1 aptamer, the DS aptamer has a short half-life (8.029 min) in cells (Figure 2B). The nomenclature of all aptamers in this research is illustrated in Table S1.

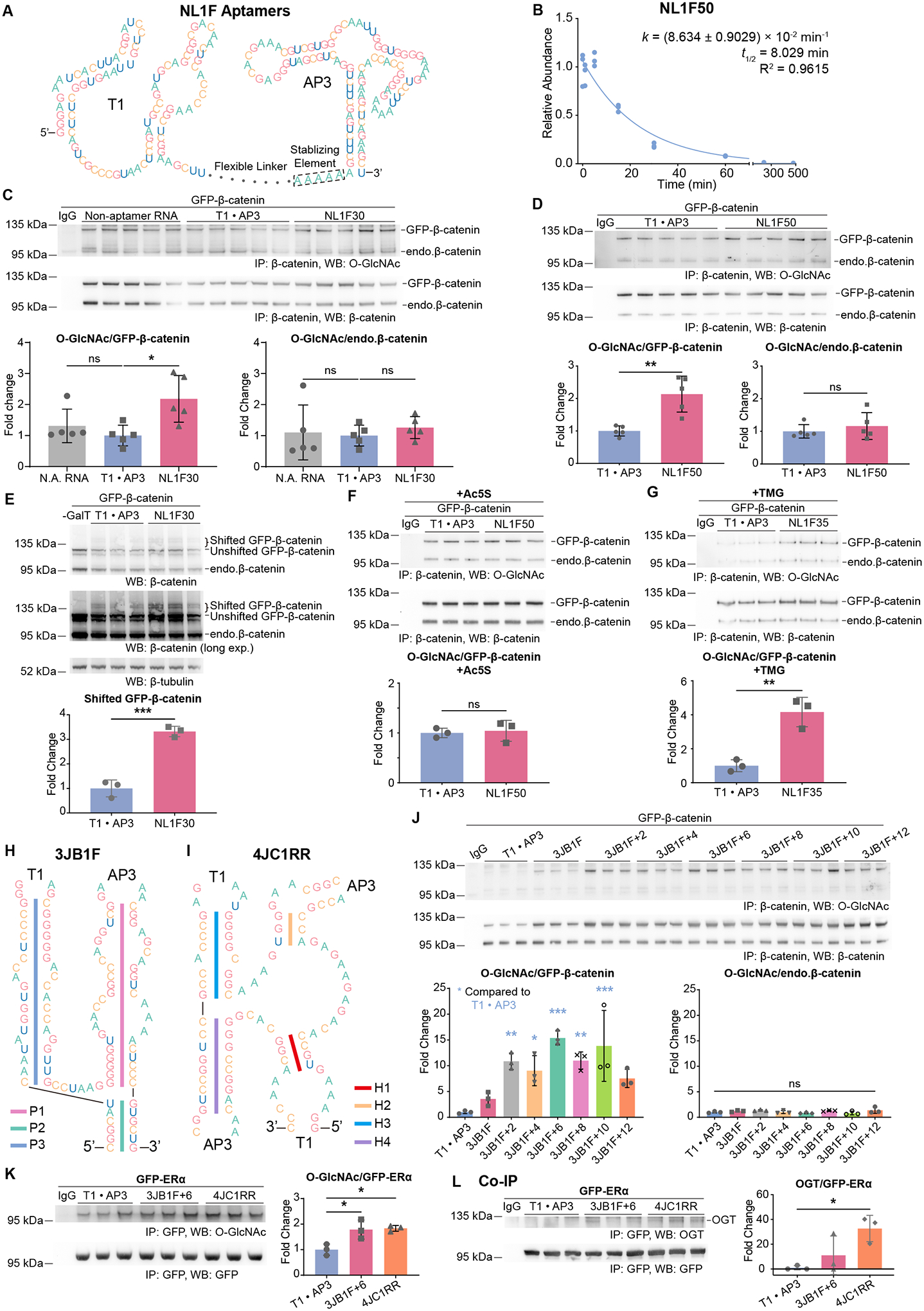

Figure 2. Dual-Specificity Aptamers Increase O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-Tagged Proteins.

(A) Schematic of DS aptamers with flexible linkers (NL1F, T1-linker-AP3). Five adenine residues are inserted upstream of AP3 to stabilize the transcribed U6 terminator.

(B) Pulse-chase experiments on the half-life of NL1F50 (T1–50nt-AP3). Experiments were performed and analyzed in the same way as in Figure 1J. N=3.

(C) and (D) IP-WB on cells expressing GFP-β-catenin and the indicated aptamers. N.A. – Non-aptamer. endo. – endogenous. N=5.

(E) Mass-shift assays on cells expressing GFP-β-catenin and the indicated aptamers. Two blots on β-catenin with short and long exposure time are shown. Intensities of the shifted bands are normalized to that of β-tubulin. N=3.

(F) and (G) IP-WB on cells expressing GFP-β-catenin and the indicated aptamers and treated with 50 μM Ac5S for 20 hr (F) or 2 μM TMG for 6 hr (G). N=3.

(H) and (I) Schematics of the DS aptamers with folded linkers. 3JB1F has a three-way RNA junction (H) and 4JC1RR has a four-way RNA junction (I) as linkers.

(J) Optimization of the folded linker in 3JB1F. IP-WB on cells expressing GFP-β-catenin and the indicated aptamers. N=3.

(K) and (L) IP-WB (K) or Co-IP (L) on HEK293T cells expressing GFP-ERα and the indicated aptamers. N=3.

T1 · AP3 – Individual T1 and AP3 aptamers (control). NL1F30/50 – DS aptamers (T1-linker-AP3) with flexible linkers of 30/50 nt. 3JB1F/4JC1RR – DS aptamers (T1-linker-AP3) with folded linkers. +2/+4/…/+12, serial additions (bp) into the folded linker. Quantitated WB data are normalized to the control groups (T1 · AP3). Aptamers and proteins were expressed from plasmids. One-way ANOVA test in (C), (J), (K), (L). Student’s t-test in other panels. Data are represented as mean ± SD. ns, p ≥ 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Expression of these NL1F DS aptamers significantly increased O-GlcNAcylation of GFP-β-catenin in a specific manner. Protein-specific O-GlcNAcylation was quantified by immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western Blot (WB). In comparison to the individual T1 and AP3 aptamers (T1 · AP3), NL1F30, NL1F35 and NL1F50 up-regulated O-GlcNAc levels on GFP-β-catenin by 2- to 3-fold (Figures 2C, 2D, S2A to S2C). Efficacy of DS aptamers was further confirmed in mass-shift assays, where O-GlcNAc groups were enzymatically labeled with N-azidoacetylgalactosamine (GalNAz), then conjugated to polyethylene glycol (PEG) of 8.5 kDa by strain-promoted alkyne-azide cycloaddition (SPAAC), causing a mobility shift of the protein in WB27. In mass-shift assays, NL1F30 and NL1F50 increased O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-β-catenin by 3.3-fold and 2.9-fold, respectively (Figures 2E, S2F). Increasing the expression of GFP-β-catenin renders NL1F35 ineffective, suggesting that the molar ratio of aptamer to substrate is important for the efficacy of DS aptamers (Figures S2B, S2C). Meanwhile, O-GlcNAc on endogenous β-catenin remained unchanged (Figures 2C, 2D, S2A), and DS aptamers did not affect global O-GlcNAcylation (Figure S2E). These results indicate good selectivity of the DS aptamers. The abundance of GFP-β-catenin was also increased, suggesting a stabilizing effect of O-GlcNAc on this protein (Figure S2E). DS aptamer increased O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-β-catenin in Wnt-stimulated cells (Figure S2G). On GFP-β-catenin, the changes in O-GlcNAcylation arose from its β-catenin portion, as O-GlcNAc on the GFP tag was undetectable (Figure S2D).

Ac4-5SGlcNAc (Ac5S) and thiamet-G (TMG) are highly potent inhibitors of OGT and OGA, respectively28,29. DS aptamers did not induce hyper-O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-β-catenin in Ac5S-treated cells but increased this modification in TMG-treated cells (Figures 2F and 2G). Thus, the activity of OGT is required for aptamer-induced O-GlcNAcylation, while the activity of OGA is not. These observations, together with the observation that the DS aptamers do not change the abundance of OGT and OGA (Figures 3C, 3D), rule out the possibility that aptamer-induced O-GlcNAcylation arise from the potential “off-target” effects of RNA aptamers.

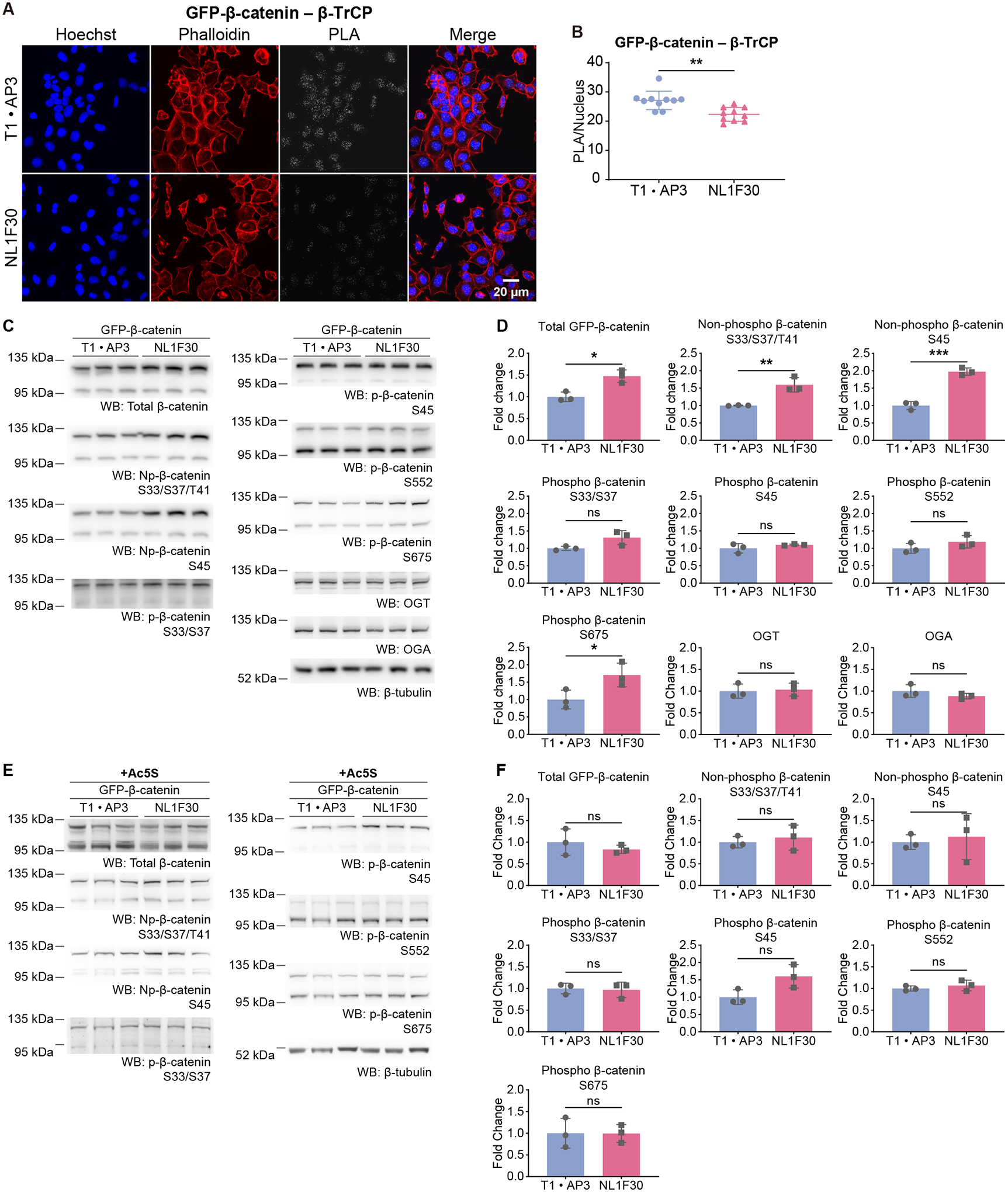

Figure 3. O-GlcNAc Stabilizes GFP-β-catenin by Inhibiting Its Interaction With β-TrCP.

(A) Confocal images of Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) on cells expressing GFP-β-catenin and the indicated aptamers. PLA was performed with antibodies targeting GFP and β-TrCP.

(B) Quantification of (A). PLA puncta are counted and normalized to the number of nuclei in each image. N=10.

(C) to (F) WB on HEK293T cells expressing GFP-β-catenin and the indicated plasmids. In (E), cells were treated with 50 μM Ac5S for 20 hr. (D) and (F) Quantifications of (C) and (E). Intensity of each band is normalized to that of β-tubulin. Np – non-phosphorylated. p – phosphorylated. N=3.

T1 · AP3 – Individual T1 and AP3 aptamers (control). NL1F30 – DS aptamers (T1-linker-AP3) with a flexible linker of 30 nt. Quantitated data are normalized to the control groups (T1 · AP3). Student’s t-test. Data are represented as mean ± SD. ns, p ≥ 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

See also Figure S3.

In addition to the single-stranded flexible linkers, we designed DS aptamers with folded linkers. Three-way and four-way RNA junctions are naturally occurring RNA structures. In family C of three-way junctions, the P1 and P2 helices are coaxially stacked while the P3 helix “bends” towards P1 (Figure 2H)30. These structural properties result in proximity between the two helices. We picked a structure (PDB 1MFQ, S-domain of 7SL RNA) from this family31 and grafted T1 and AP3 onto its helices. By swapping the locations of T1 and AP3, two DS aptamers (3JB1F and 3JB1R) were generated (Figures 2H, S2H). On 3JB1F and 3JB1R, T1 and AP3 were of identical distance but different orientations. To optimize the folded linkers, we introduced serial additions into the P3 helices of 3JB1F and 3JB1R (Figure S1A). Considering that in RNA double helices, addition of 1 bp introduces a rotation of 32.7° but only increases the length by 2.8 Å32, these additions cause notable changes in the orientation of T1/AP3, but minor variations on the distance.

The 3JB1F variants significantly promoted O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-β-catenin (Figure 2J). The original 3JB1F increased this PTM by 3.5-fold, which was dramatically improved by serial additions on its P3 helix. Most of the variants increased O-GlcNAc on GFP-β-catenin by more than 10-fold. Among them, the variant with 6 bp addition (3JB1F+6; Figure S1A) increased this PTM by 15-fold. Notably, the impact of serial additions showed some “periodicity”, which peaked at 6 bp and decreased as additions grew longer. This observation agrees with the structural properties of RNA helices, where addition of 11 bp introduces a 360° rotation. Meanwhile, O-GlcNAcylation of endogenous β-catenin remained unchanged (Figure 2J). 3JB1R increased O-GlcNAcylation of GFP-β-catenin by 2-fold, however, serial additions had little effect (Figure S2I). This observation indicates that on 3JB1R, the orientation of T1 is suboptimal, so that OGT is facing away from its target protein when bound to the complex.

DS aptamers increase O-GlcNAc levels on other GFP-tagged proteins. Here we designed another folded linker. In family π of four-way RNA junctions, the helices H3 and H4 are coaxially stacked while H1 and H2 “swings”, and H2 is attracted to H3 (Figure 2I)33. We picked a structure (PDB 1U9S, specificity domain of A-type ribonuclease P) from this family34, and grafted two copies of T1 and AP3 onto its helices (Figure S1B). This 4JC1RR, as well as 3JB1F+6, increased O-GlcNAc on GFP-tagged Estrogen Receptor α (ERα), Src and AMP-activated protein kinase α2 (AMPKα2) (Figures 2K, S2J, S2L). Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) revealed that 4JC1RR promoted the interactions between OGT and these proteins (Figures 2L, S2K), supporting our hypothesis that DS aptamers increase O-GlcNAcylation by inducing proximity between OGT and its substrates.

In conclusion, DS aptamers with flexible or folded linkers promote interactions between OGT and GFP-tagged proteins and selectively increase O-GlcNAcylation on these substrates.

DS Aptamers Reveal Unmapped O-GlcNAc Sites on β-catenin

Our study reveals unmapped O-GlcNAc sites. Four O-GlcNAc sites have been mapped (Ser23, Thr40, Thr41 and Thr112) on β-catenin18. When all these sites were mutated to alanine, O-GlcNAcylation on this GFP-β-catenin4A mutant was still induced by NL1F30 or 3JB1F+6 (Figures S3A, S3E), though to a lesser extent than on the wild-type protein (Figures 2C, 2J). This induction required the activity of OGT (Figures S3C, S3G). Similar to on the wild-type protein, O-GlcNAc stabilized the 4A mutant (Figures S3B, S3F). Interestingly, though NL1F30 did not induce higher O-GlcNAcylation than 3JB1F+6, it was more effective on stabilizing the protein. The stabilization effects required the activity of OGT (Figures S3D, S3H). These observations suggest that NL1F30 and 3JB1F+6 have different site-selectivity when inducing O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-β-catenin, and that O-GlcNAc on the unidentified sites regulates the stability of β-catenin.

In control experiments without aptamers, O-GlcNAc signal on the 4A mutant was reduced by a bacterial homolog of OGA (CpOGA)35, or by competing the O-GlcNAc antibody with 1 M GlcNAc during WB (Figures S3I, S3J). These results confirm the WB bands to be specific to O-GlcNAc, and that O-GlcNAc on the 4A mutant was not artifacts of aptamer expression.

O-GlcNAc Stabilizes GFP-β-catenin by Inhibiting Its Interaction With β-TrCP

As the key transcription factor of the Wnt signaling pathway, β-catenin is activated by Wnt. Without Wnt, newly synthesized β-catenin is recruited to a destruction complex comprised of Axin, APC, GSK3β and CK1. In the complex, β-catenin is consecutively phosphorylated by CK1 and GSK3β on its Ser45, Thr41, Ser37 and Ser33 residues, ubiquitinated by the SCFβ-TrCP complex and degraded by proteasomes15,16,36. Binding of Wnt to the membrane receptor Frizzled triggers a cascade of signaling events, which ultimately blocks the ubiquitination of phosphorylated β-catenin in the destruction complex17. Stabilized β-catenin saturates the complex, accumulates in the cytoplasm, enters the nucleus, and activates transcription37.

β-TrCP recruits β-catenin that is phosphorylated on Ser33 and Ser37 to the SCFβ-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase, causing its ubiquitination and degradation15,38. In Proximity Ligation Assays (PLA), we found that DS aptamer inhibited the interaction between GFP-β-catenin and β-TrCP (Figures 3A, 3B). We reasoned that impairing this interaction would inhibit the degradation of phosphorylated GFP-β-catenin, therefore saturate the destruction complex, stabilize the newly synthesized, unphosphorylated GFP-β-catenin, and increase the total abundance of this protein (Figures S2E, 3C, 3D, S3B, S3F). DS aptamer increased the non-phosphorylated moiety of GFP-β-catenin regarding Ser33, Ser37, Thr41 and Ser45 (Figures 3C, 3D), agreeing with our hypothesis. Meanwhile, abundance of phosphorylated GFP-β-catenin was unchanged regarding these sites (Figures 3C, 3D), suggesting that O-GlcNAc inhibit the interaction between GFP-β-catenin and β-TrCP not by competing phosphorylation, but likely by steric hinderance since it has a large Stokes radius39. Additionally, DS aptamer increased phosphorylation on Ser675 (Figures 3C, 3D) that enhances the transcriptional activity of β-catenin40. These site-specific phosphorylations on endogenous β-catenin were not changed (Figures 3C, S3K). Changes of site-specific phosphorylation required the activity of OGT (Figures 3E, 3F, S3L), supporting that they were caused by aptamer-induced O-GlcNAcylation.

In conclusion, O-GlcNAc on GFP-β-catenin inhibits its recognition by β-TrCP and stabilizes this protein.

DS Aptamers Increase O-GlcNAcylation on Endogenous β-catenin

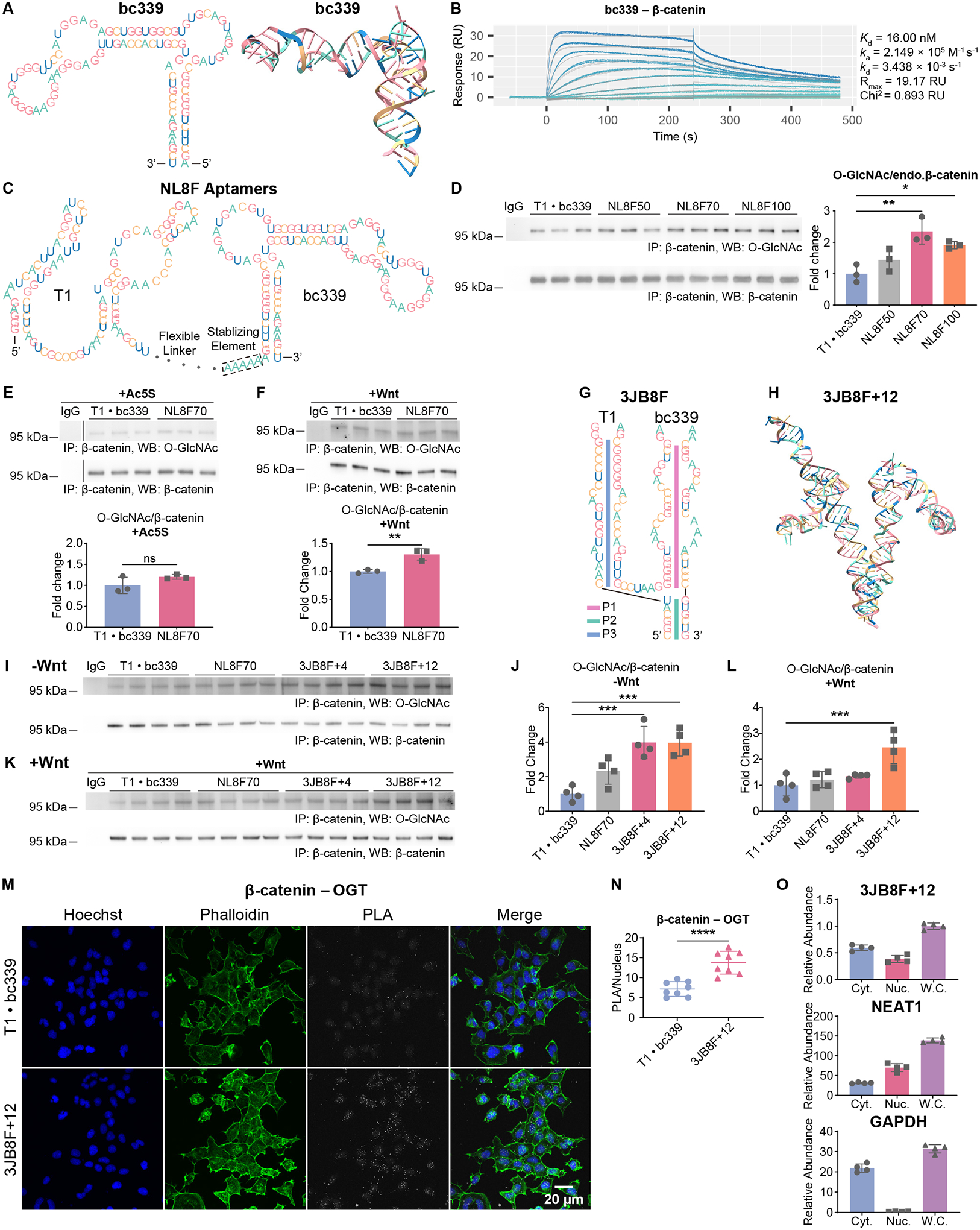

Beyond epitope-tagged proteins, we asked if DS aptamers could regulate O-GlcNAc on endogenous proteins. An RNA aptamer (bc339) targeting β-catenin was generated from SELEX (Figure 4A). We characterized its binding properties by SPR (Figure 4B). The dissociation constant (Kd) between bc339 and β-catenin is 16.00 nM. We connected this aptamer (bc339) to T1 with a series of flexible linkers, thus the NL8F DS aptamers were designed (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. DS Aptamers Increase O-GlcNAcylation on Endogenous β-catenin.

(A) Predicted secondary (left panel) and tertiary (right panel) structures of bc339. Nucleotides in the two panels are color coded in the same way.

(B) SPR characterizating the binding affinity and kinetics of bc339. Sensorgrams represent β-catenin concentrations from 1 μM to 122 pM in 2× serial dilutions. Data are fitted to a 1:1 binding model.

(C) Schematic of DS aptamers with flexible linkers (NL8F, T1-linker-bc339). Five adenine residues are inserted upstream of bc339 to stabilize the transcribed U6 terminator.

(D) IP-WB on HEK293T cells expressing the indicated aptamers. N=3.

(E) and (F) IP-WB on HEK293T cells expressing the indicated aptamers and treated with 50 μM Ac5S for 20 hr (E) or Wnt3A-conditioned medium for 4 hr (F). Irrelevant lanes are cropped. N=3.

(G) Schematic of DS aptamers (3JB8F, T1-linker-bc339) with folded linkers.

(H) Predicted tertiary structure of the DS aptamer 3JB8F+12. Nucleotides are color coded in the same way as in (G). Complete sequence and secondary structure prediction are shown in Figure S1C.

(I) to (L) IP-WB on HEK293T cells expressing the indicated aptamers, under −Wnt (I, J) and +Wnt (K, L) conditions. (J) and (L) Quantification of (I) and (K). N=4.

(M) and (N) Confocal images of PLA on HEK293T cells expressing the indicated aptamers. (N) Quantification of (M). Total PLA puncta is counted and normalized to the number of nuclei in each image. N=8.

(O) Subcellular localization of 3JB8F+12. Nucleus and cytoplasm of cells stably expressing 3JB8F+12 was isolated, and RNA in each fraction was quantified by RT-qPCR. RNA abundances are normalized to that of 3JB8F+12 in whole cell lysate (purple bar in upper panel). NEAT1 is a nuclear RNA control. GAPDH is a cytoplasmic RNA control. Cyt. – Cytoplasm. Nuc. – Nucleus. W.C. – Whole Cell. N=4.

T1 · bc339 – Individual T1 and bc339 aptamers (control). NL8F50/70/100 – DS aptamers (T1-linker-bc339) with flexible linkers of 50/70/100 nt. 3JB8F – DS aptamers (T1-linker-bc339) with folded linkers. +4/+12, serial additions (bp) into the folded linker. Quantitated data are normalized to the control groups (T1 · bc339). Aptamers were expressed from plasmids. Student’s t-test in (E), (F), (N). One-way ANOVA test in other panels. Data are represented as mean ± SD. ns, p ≥ 0.05; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

NL8F70 and NL8F100 increased O-GlcNAcylation of endogenous β-catenin by 2.3- and 1.9-fold, respectively (Figure 4D). NL8F100 moderately stabilized β-catenin (Figure S4A). Meanwhile, global O-GlcNAcylation, as well as the abundance of OGT and OGA, remained unchanged (Figure S4A). These results reveal good selectivity of the DS aptamers. Inhibiting OGT prevented aptamer-induced O-GlcNAcylation (Figure 4E). Efficacy of NL8F70 was confirmed in mass-shift assay (Figure S4B). However, when Wnt signaling was activated, efficacy of NL8F70 became less clear (Figures 4F, 4K, 4L).

We also constructed DS aptamers with folded linkers. By replacing the GFP aptamer (AP3) in the 3JB1F constructs with bc339, we designed the 3JB8F constructs (Figures 4G, 4H, S1C). Among them, 3JB8F+12 increased O-GlcNAcylation of β-catenin by 4-fold in the absence of Wnt (Figures 4I, 4J), and by 2.5-fold in the presence of Wnt (Figures 4K, 4L). It also stabilized β-catenin (Figures S4C, S4D). Global O-GlcNAcylation was not changed by 3JB8F+12 under either condition (Figures S4E, S4F). Like other DS aptamers, 3JB8F+12 requires the activity of OGT to induce O-GlcNAcylation under both −Wnt and +Wnt conditions (Figures S4G, S4H).

In PLA and Co-IP, we found that 3JB8F+12 substantially promoted the interaction between OGT and β-catenin (Figures 4M, 4N, S4I). These results support our hypothesis that DS aptamers regulate O-GlcNAcylation by targeting a substrate protein to OGT. We studied the subcellular localization of DS aptamers by nucleus/cytoplasm fractionation and RT-qPCR (Figure 4O). Compared to the RNA species enriched in nucleus (NEAT1) and cytoplasm (GAPDH), 3JB8F+12 localizes in both. Therefore, DS aptamers could regulate O-GlcNAcylation on both nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins.

We constructed another DS aptamer (3JB8R+12) by swapping T1 and bc339 on 3JB8F+12 (Figures S1D, S4J). Though it consists of identical modules, 3JB8R+12 was unable to regulate O-GlcNAcylation of β-catenin under either status of Wnt signaling (Figures S4K and S4L). This observation further supports our hypothesis that not only the distance, but also the orientations of the individual aptamers on the folded linker are critical to the efficacy of DS aptamers.

In conclusion, the T1-linker-bc339 DS aptamers specifically increase O-GlcNAcylation on endogenous β-catenin. DS aptamers could induce O-GlcNAcylation in both nucleus and cytoplasm.

O-GlcNAc Regulates β-catenin’s Interactions With Epigenetic Modifiers and Increases Its Transcriptional Activity

We then studied how O-GlcNAc regulates the functions of β-catenin using DS aptamers. As a transcription factor that does not have a DNA binding domain, the functions of β-catenin heavily rely on its interactions with other proteins, including EZH2, KAT2A and EP30041–43.

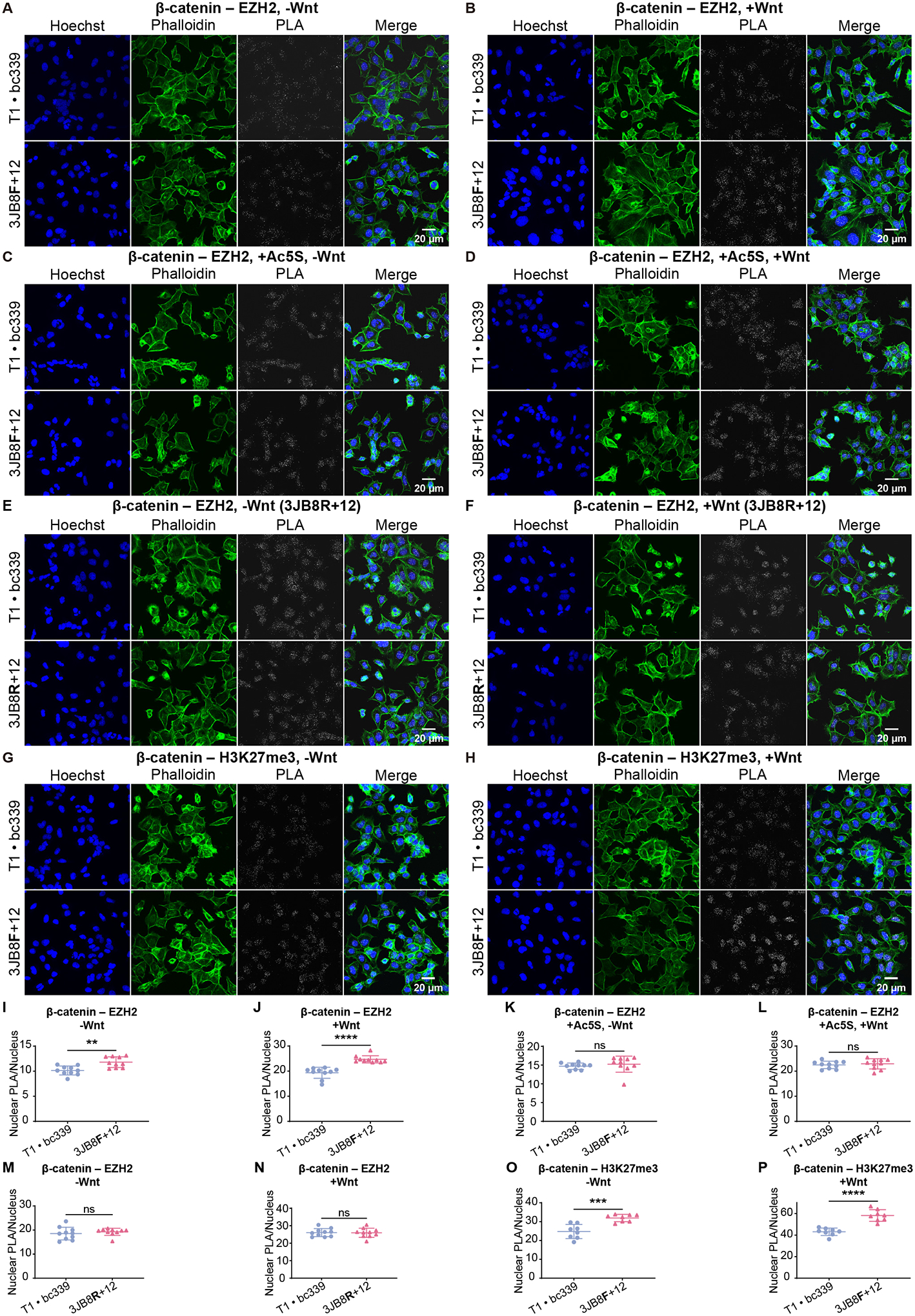

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which plays important roles in gene repression and during development44,45. It catalyzes the tri-methylation of Lys27 on Histone H3 (H3K27me3), which marks silent promoters46. In PLA and Co-IP, we found that the interaction between β-catenin and EZH2 was increased by 3JB8F+12, regardless of the Wnt signaling status (Figures 5A, 5B, 5I, 5J, S4M, S4N). This increase was prevented by inhibition of OGT (Figures 5C, 5D, 5K, 5L). Furthermore, 3JB8R+12, the DS aptamer that does not change O-GlcNAc levels on β-catenin, had no effect on this interaction (Figures 5E, 5F, 5M, 5N). Proximity between β-catenin and H3K27me3 was also increased by 3JB8F+12 (Figures 5G, 5H, 5O, 5P). We conclude that O-GlcNAcylation of β-catenin promotes its interaction with EZH2.

Figure 5. O-GlcNAc Promotes β-catenin’s Interactions With EZH2.

(A) to (H) Confocal images of PLA on HEK293T cells expressing the control aptamers (T1 · bc339) or a DS aptamer (3JB8F+12 or 3JB8R+12), under −Wnt or +Wnt conditions. PLA was performed with antibodies targeting β-catenin and EZH2 or H3K27me3. In (C) and (D), cells were treated with 50 μM Ac5S for 20 hr.

(I) to (P) Quantification of (A) to (H). PLA puncta in nucleus are counted and normalized to the number of nuclei in each image. Student’s t-test, N=10 (I to N) or 8 (O, P). Data are represented as mean ± SD. ns, p ≥ 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

T1 · bc339 – Individual T1 and bc339 aptamers (control). 3JB8F+12/R+12 – DS aptamers (T1-linker-bc339) with folded linkers.

See also Figures S5 and S6.

KAT2A (GCN5) is a histone acetyltransferase that acetylates the Lys9 of histone H3 (H3K9ac). H3K9ac correlates with actively expressed genes47. In PLA, we found that 3JB8F+12 increased the interaction between β-catenin and KAT2A in spite of the Wnt signaling status (Figures S5A, S5B, S5I, S5J). Inhibition of OGT prevented this change (Figures S5C, S5D, S5K, S5L). 3JB8R+12 had no effect on this interaction (Figures S5E, S5F, S5M, S5N). Moreover, 3JB8F+12 also increased the proximity between β-catenin and H3K9ac (Figures S5G, S5H, S5O, S5P). In conclusion, O-GlcNAc on β-catenin enhances its interaction with KAT2A.

3JB8F+12 regulates the interactions between β-catenin and other histone modifiers. It significantly inhibited the interaction between β-catenin and EP300, an acetyltransferase and transcription coactivator (Figures S6A, S6B, S6I, S6J)48. It also impaired the interaction between β-catenin and KAT5 (TIP60), a lysine acetyltransferase that is involved in the regulation of transcription, in DNA repair and in apoptosis (Figures S6C, S6D, S6K, S6L)49. Additionally, this DS aptamer inhibits the interaction between endogenous β-catenin and β-TrCP (Figures S6E, S6F, S6M, S6N), agreeing with our observation on GFP-β-catenin and β-TrCP (Figures 3A, 3B). Negative control experiments revealed good specificity of PLA experiments (Figures S6G, S6H, S6O, S6P).

Using aptamers, we studied how O-GlcNAc regulates β-catenin’s transcriptional activity in Wnt signaling. In TOPFlash assays, 3JB8F+12 elevated the activity of β-catenin in response to Wnt (Figure S7A), which required the activity of OGT (Figure S7B). These results agree with the observations when the O-GlcNAc modifying enzymes was inhibited with genetic or chemical approaches. Knockdown of OGT considerably impaired the activity of β-catenin, which was restored by rescuing this enzyme (Figure S7C). Reducing global O-GlcNAcylation with the OGT inhibitor (Ac5S) impaired the activity of β-catenin, but elevating global O-GlcNAcylation with the OGA inhibitor (TMG) further activated it (Figure S7D). In a control experiment, neither single or double individual aptamers (T1, bc339, T1 · bc339) affected the activity of β-catenin (Figure S7E). In conclusion, O-GlcNAc on β-catenin promotes its activity in response to Wnt. However, the luciferase reporter in TOPFlash assay is encoded on a plasmid and driven by an artificial promoter that contains seven TCF/LEF binding sites. Its expression is highly sensitive to β-catenin but has a different epigenetic context comparing to chromosomal genes. Thus, this assay measures the activity of β-catenin at high sensitivity, but the native regulations on chromosomal genes are not represented.

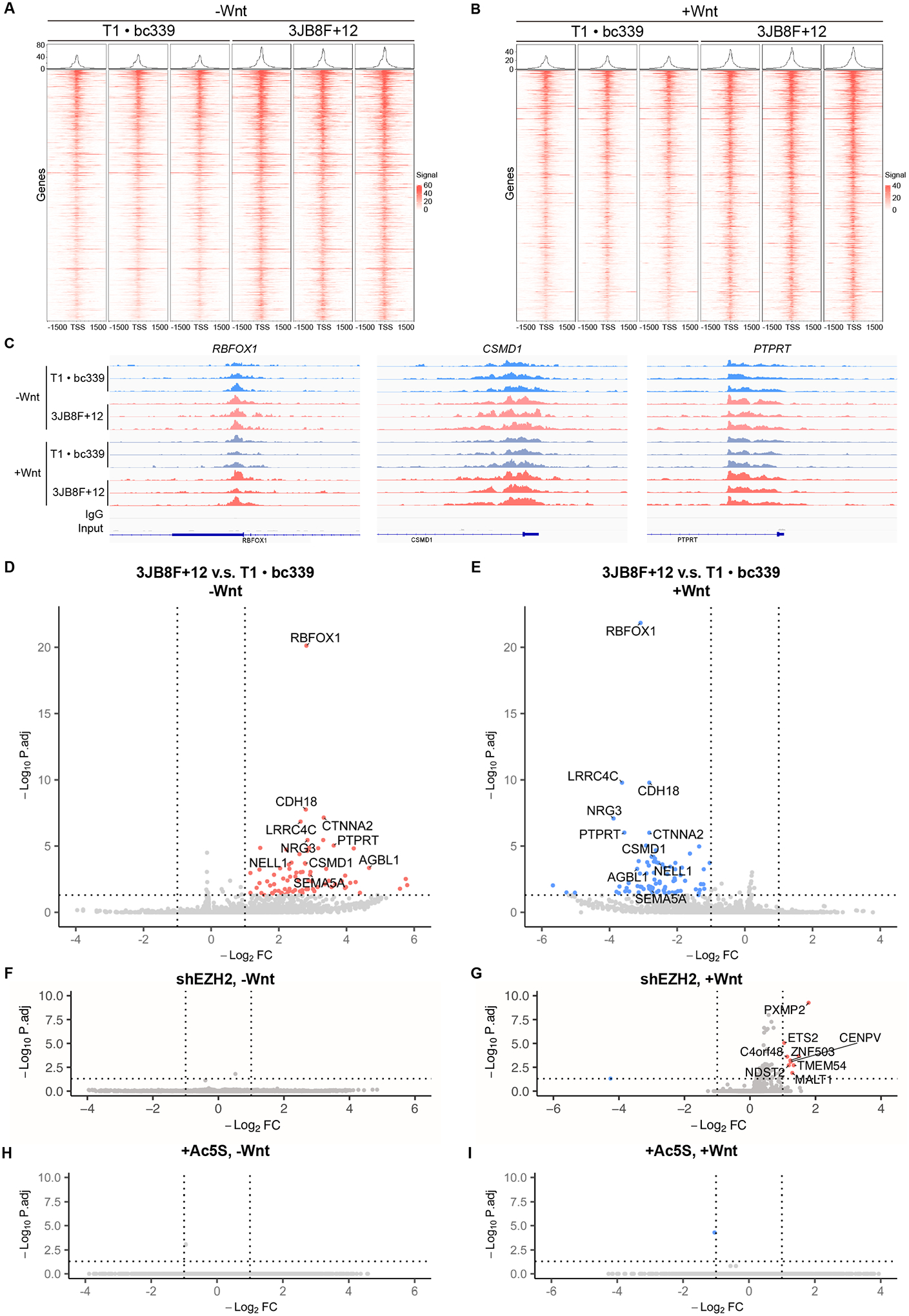

O-GlcNAc on β-catenin Recruits EZH2 to Promoters and Shifts the Transcriptome

Next, we wondered if the enhanced interaction with β-catenin regulates the chromatin binding of EZH2. We performed Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease (CUT&RUN) on HEK293T cells expressing the individual aptamers (T1 · bc339) or the DS aptamer (3JB8F+12)50,51. CUT&RUN sequencing revealed that 3JB8F+12 increased the binding of EZH2 on 923 and 3473 sites in the absence and presence of Wnt, respectively (Figures 6A to 6C; Table S4). The differential binding sites predominantly localized on the promoter regions of the genome (Figures S7F, S7G). All differential binding events of EZH2 were prevented by knocking-down β-catenin, or by inhibiting OGT (Figures S7H, S7I, S7K), indicating they required increased O-GlcNAcylation and β-catenin. In addition, β-catenin is critical to the chromatin localization of EZH2, as its knockdown drastically impaired the promoter binding of EZH2 without affecting its abundance (Figures S7J, S7K). Given that O-GlcNAc on β-catenin enhances its interaction with EZH2 (Figures 5, S4M, S4N), we conclude that the strengthened interaction recruits EZH2 to promoters.

Figure 6. O-GlcNAc on β-catenin Recruits EZH2 to Promoters and Shifts the Transcriptome.

(A) and (B) Heatmap of the differential binding sites of EZH2. CUT&RUN sequencing was performed to HEK293T cells expressing the indicated aptamers and exposed to regular (−Wnt) or Wnt3A-conditioned (+Wnt) medium.

(C) The binding peaks of EZH2 on three promoters under indicated conditions.

(D) to (I) Volcano plot of RNA-seq data. HEK293T cells expressing the control (T1 · bc339) or DS (3JB8F+12) aptamers were treated with regular (−Wnt) or Wnt3A-conditioned (+Wnt) medium. In (F) and (G), EZH2 was knocked-down in cells with a shRNA. In (H) and (I), cells were treated with Ac5S.

T1 · bc339 – Individual T1 and bc339 aptamers (control). 3JB8F+12 – DS aptamer (T1-linker-bc339) with a folded linker.

We further asked if increased O-GlcNAcylation of β-catenin impacts the transcriptome. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) was performed on HEK293T cells expressing either the individual (T1 · bc339) or the DS (3JB8F+12) aptamers, in the absence and presence of Wnt. Surprisingly, the DS aptamer altered the transcriptome in opposite ways depending on the status of Wnt signaling. In the absence of Wnt, 3JB8F+12 promoted the expression of 83 genes. In contrast, when Wnt signaling was activated, 3JB8F+12 repressed the expression of 85 genes (Figures 6D, 6E; Table S5). These differential expressions required both EZH2 and elevated O-GlcNAc, as they were prevented by knocking-down EZH2 or inhibiting OGT (Figures 6F to 6I, S7K). In addition, when EZH2 was knocked-down and Wnt was present, O-GlcNAcylation of β-catenin slightly enhanced the transcription of eight other genes (Figures 6G, 6I). This observation suggests that O-GlcNAc on β-catenin also has mild, EZH2-independent activating effects on transcription, which could be overwritten by its EZH2-dependent repressive effects. Considering that EZH2 is associated with PRC2 that is a transcription repressor, the increased promoter binding of EZH2 may function in the repression of genes caused by O-GlcNAcylation of β-catenin when Wnt signaling was activated. However, the mechanism underlying the activation of genes without Wnt awaits further investigation. As EZH2 was reported to activate the androgen receptor gene independently of PRC2 and its methyltransferase activity52, it is possible that EZH2 activated the genes we observed in the same way. It is also possible that O-GlcNAc on β-catenin recruited some transcription activators to the chromatin when Wnt was absent, which we have not identified in this research.

In conclusion, O-GlcNAc on β-catenin strengthens its interaction with EZH2 and recruits EZH2 to the promoters. Globally, it regulates the transcriptome in two ways: it activates gene expression in the absence of Wnt but represses gene expression when Wnt signaling is activated. Our study reveals a synergistic mechanism that β-catenin regulate gene expression by recruiting histone modifiers.

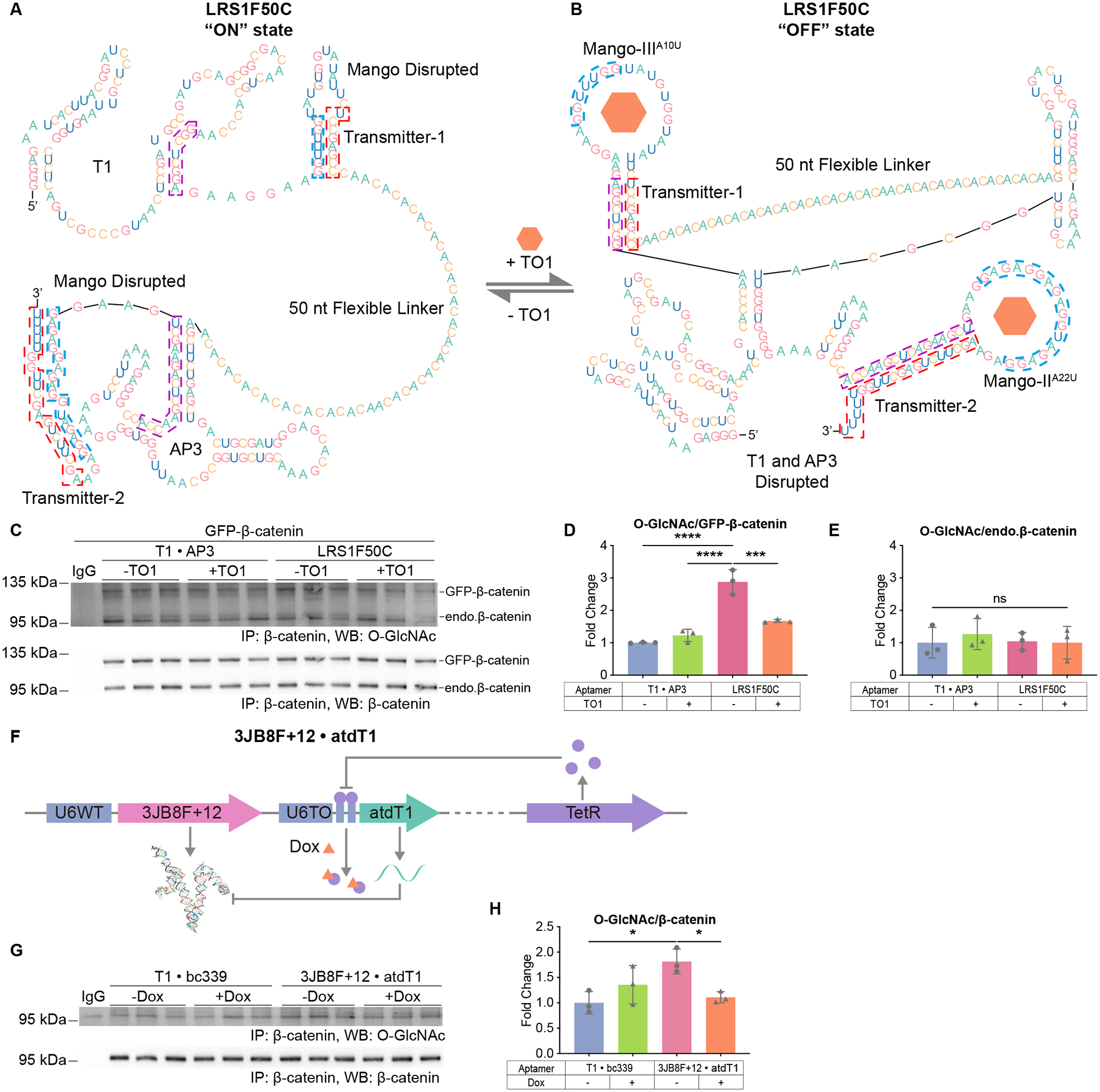

Inducible Regulation of O-GlcNAcylation by Coupling DS Aptamers to Riboswitches or a Tet-On System

DS aptamers allow us to regulate O-GlcNAcylation on a single protein and to study protein-specific effects of this PTM. However, there is a concern about this method: will the normal functions of OGT and substrate proteins be interfered, if DS aptamers remain bound to them? This concern is partly solved by the fact that the individual and dual-specificity aptamers are short-lived (Figures 1J, 2B). Nevertheless, an inducible mechanism that forces the aptamers to dissociate from their targets would be ideal.

We designed inducible DS aptamers by incorporating riboswitch elements. Riboswitches are naturally derived or artificially designed RNA that change their conformations upon binding of ligands53,54. They usually contain three modules: a sensor that is a ligand-binding aptamer; an actuator that carries out downstream effects; and a transmitter sequence that couples the two55. In our design, two sets of riboswitches were incorporated into the DS aptamer NL1F50. In the newly generated inducible DS aptamer LRS1F50C (Figures 7A, 7B), the fluorogenic “Mango” aptamers serve as sensors56,57. TO1-biotin (TO1), the ligand of Mango, is a non-toxic, membrane permeable molecule that binds Mango with low nanomolar affinity58. The T1 and AP3 aptamers are the actuators, since it is their binding that the riboswitches aim to regulate. The transmitter elements were designed so that they bind the core sequences of Mango in the absence of TO1, but switch to bind T1 and AP3 in the presence of TO1 (STAR Methods). As a result, addition of TO1 triggers the folding of Mango, which disrupts the folding of T1 and AP3 and “turns off” the function of the DS aptamer (Figures 7A, 7B). In cells, LRS1F50C increased O-GlcNAcylation on GFP-β-catenin by 3-fold without affecting that of endogenous β-catenin, and it was inactivated by TO1 (Figures 7C to 7E).

Figure 7. Inducible Regulation of O-GlcNAcylation by Coupling DS Aptamers to Riboswitches or a Tet-On System.

(A) and (B) Schematics of LRS1F50C and its conformation transitions. The transmitter elements are boxed in red, their alternative binding sequences are boxed in blue and purple. (A) The “ON” state of LRS1F50C. (B) The “OFF” state of LRS1F50C.

(C) to (E) IP-WB on cells expressing GFP-β-catenin and the indicated aptamers, and treated with 750 μM TO1 (+TO1) or equal volume of DMF (−TO1). (D) and (E) Quantification of (C). N=3.

(F) Schematic of controlling 3JB8F+12 with a Tet-On system.

(G) and (H) IP-WB on cells transfected with the indicated plasmids, and treated with Dox (+Dox) or equal volume of DMSO (−Dox). (H) Quantification of (G). N=3.

Two-way ANOVA test. Data are represented as mean ± SD. ns, p ≥ 0.05; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

We also used a Tet-On inducible expression system to control the function of DS aptamers. In this system, 3JB8F+12 is constitutively expressed, driven by a wild-type U6 promoter (U6WT). An antidote RNA of T1 (atdT1) is expressed under an inducible promoter (U6TO), which combines a truncated U6 promoter with two Tet operator elements. Doxycycline (Dox) activates the expression of atdT1, which disrupts the folding of 3JB8F+12 (Figure 7F). In cells, this system induced O-GlcNAcylation on endogenous β-catenin in the absence of Dox, and addition of Dox rendered it inactive (Figures 7G, 7H). Since aptamers are short-lived in cells (Figures 1J, 2B), inducible expression could allow the dynamic control of DS aptamers at high time-resolution.

Taken together, using riboswitches or the Tet-On system, we showed the proof-of-principle that DS aptamers can be used for inducible regulation of protein-specific O-GlcNAcylation. Further optimization on the riboswitches and the Tet-On system are necessary to improve the specificity and dynamic ranges of these tools.

DISCUSSION

We developed DS aptamers that induce protein-specific O-GlcNAcylation, without changing the activity of OGT or OGA, or tagging these enzymes that interferes with their normal functions. Using these tools, we found that O-GlcNAc regulates β-catenin by tuning its interactions with other proteins like β-TrCP and EZH2. Riboswitches or inducible expression systems can be used for the dynamic control of DS aptamers. The modular feature endows DS aptamers broad potential applications, such as regulating other PTMs, facilitating the formation of protein complexes, and even inducing proximity between proteins and/or organelles.

Unmapped O-GlcNAc Sites on β-catenin

Our research reveals unmapped O-GlcNAc sites on β-catenin (Figures S3A to S3J). We also find that O-GlcNAc on β-catenin regulates its interactions with KAT2A and EP300 (Figures S5, S6). Considering that β-catenin binds EP300 and KAT5 via its C-terminus41,59, and that O-GlcNAc interplays with phosphate on Ser675 (Figure 3C), some of the unmapped sites probably reside in this region. O-GlcNAc stabilizes the GFP-β-catenin4A mutant (Figures S3B, S3F). Since O-GlcNAc stabilizes β-catenin by inhibiting its interaction with β-TrCP (this study), which recognizes phosphorylation on Ser33 and Ser3715, some of the unmapped sites could be near this region. Mapping these sites will be important for investigating the site-specific effects of O-GlcNAc in the future.

Critical Roles of the Linker in DS Aptamers

The linker domain, which critically affects the efficacy of DS aptamers, can adopt either flexible or folded structures. Our optimization of the folded linkers reveals that in a DS aptamer, both the distance between the two individual aptamers and their orientations are important factors. Folded linkers tend to increase the efficacy of DS aptamers (Figures 2C, 2D, 2J; 4D, 4F, 4I to 4L), probably because 1) they induce higher degrees of proximity than flexible linkers; and 2) the folding of these linkers is highly spontaneous (ΔG ≪ 0), which facilitates the folding of the aptamer motifs. Meanwhile, the rigidity of folded linkers seems to reduce the degrees of freedom of the bound proteins, so that some variations of these DS aptamers do not increase O-GlcNAcylation. Therefore, when using these DS aptamers to target a new protein, an optimization that covers 0 – 11 bp variations of the RNA helix (0 – 360° rotation) will be needed. Alternative choices are folded linkers with more flexibility, like the 4-way RNA junction we used in this study (Figure 2I). In this linker, the H1 and H2 helices “swings”, which provides the bound proteins higher degrees of freedom.

The rigidity of folded linkers could provide better site-selectivity when inducing O-GlcNAcylation. Though NL1F30 is no more effective than 3JB1F+6 on inducing O-GlcNAcylation on the GFP-β-catenin mutant (Figures S3A, S3E), it is much more effective in stabilizing the protein (Figures S3B, S3F), indicating that the two DS aptamers have different site-selectivity. On 3JB1F+6, the rigid RNA helix restricts the bound proteins so that only certain O-GlcNAc sites on β-catenin are accessible to OGT, thus O-GlcNAcylation is preferably induced on these residues. Therefore, the substrate protein could be “rotated” gradually by introducing serial additions or deletions to the RNA helix where it resides, and O-GlcNAc on different sites can be induced.

Limitations of the Study

We used IP-WB and mass-shift assay to detect O-GlcNAc on β-catenin. Antibodies of β-catenin were used to precipitate the protein in IP, or to detect its shifted bands in WB. However, most available antibodies recognize β-catenin on its N- or C- terminus, where O-GlcNAc sites are identified or indicated in this study. We have found that O-GlcNAc and PEG at or near the epitope inhibits antibody recognition, thus the aptamer-induced O-GlcNAcylation in this study may be underestimated.

We show proof-of-principle of using riboswitches and Tet-On system to control DS aptamers, further optimization is needed on their designs. Also, the T1 and bc339 aptamers can be optimized for higher affinity and shorter lengths. Our data suggests unidentified O-GlcNAc sites on β-catenin but we did not map them, thus the site-selectivity of DS aptamers are speculative. In future studies, site-mapping will be needed to confirm the physiological relevance of the aptamer-induced O-GlcNAcylation in this study. The mechanism of EZH2-dependent transcription activation and repression also awaits investigation.

STAR METHODS

RESOURSE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Gerald W. Hart (gwhart@jhmi.edu).

Materials Availability

Plasmids generated in this study have been deposited to Addgene. Cell lines generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a complete Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

CUT&RUN-seq and RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table. All other data have been deposited at Figshare and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The DOI is listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-O-GlcNAc IgM (strain CTD110.6) | Comer et al.81 Produced in the lab | N/A |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-OGT (AL28) | Iyer et al.82 Produced in the lab | N/A |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-OGT (AL24) | Kreppel et al.80 Produced in the lab | N/A |

| Chicken polyclonal anti-OGA IgY (345) | Butkinaree et al.83 Produced in the lab | N/A |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-β-Catenin (clone 14) | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 610153; RRID: AB_397555 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-β-Catenin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 9562; RRID: AB_331149 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-β-Catenin | ProteinTech | Cat#: 17565-1-AP; RRID: AB_2088102 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Non-phospho (Active) β-Catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41) (D13A1) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 8814; RRID: AB_11127203 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Non-phospho (Active) β-Catenin (Ser45) (D2U8Y) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 19807; RRID: AB_2650576 |

| Recombinant Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-β-Catenin (Ser33/37) (4HCLC) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 711404; RRID: AB_2633009 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-β-Catenin (Ser45) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 9564; RRID: AB_331150 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-β-Catenin (Ser552) (D8E11) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 5651; RRID: AB_10831053 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-β-Catenin (Ser675) (D2F1) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 4176, RRID: AB_1903923 |

| Recombinant Rabbit monoclonal anti-GFP | Invitrogen | Cat#: G10362; RRID: AB_2536526 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-GFP (3E6) | Invitrogen | Cat#: A-11120; RRID: AB_221568 |

| GFP-Trap Magnetic Agarose | ProteinTech | Cat#: gtma-10; RRID: AB_2631358 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-β-TrCP | Invitrogen | Cat#: PA5-106884; RRID: AB_2854548 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-EZH2 (D2C9) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 5246; RRID: AB_10694683 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-EP300 (clone NM11) | Active Motif | Cat#: 61401; RRID: AB_2716754 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-KAT2A/GCN5L2 (C26A10) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 3305; RRID: AB_2128281 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-KAT5 | ProteinTech | Cat#: 10827-1-AP; RRID: AB_2128431 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-H3K27me3 (C36B11) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 9733; RRID: AB_2616029 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-H3K9ac (C5B11) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 9649; RRID: AB_823528 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-β-Tubulin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 2146; RRID: AB_2210545 |

| Normal Rabbit IgG | Millipore | Cat#: 12-370; RRID: AB_145841 |

| Normal Rabbit IgG | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: 2729; RRID: AB_1031062 |

| Mouse IgG1 Isotype Control (MOPC-21) | Invitrogen | Cat#: MA1-10406; RRID: AB_2536774 |

| Goad anti-Mouse IgM (μ-chain specific) polyclonal secondary antibody, HRP-conjugated | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: A8786; RRID: AB_258413 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (Heavy Chain), Superclonal recombinant secondary antibody, HRP-conjugated | Invitrogen | Cat#: A27036; RRID: AB_2536099 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), Superclonal recombinant secondary antibody, HRP-conjugated | Invitrogen | Cat#: A28177; RRID: AB_2536163 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Stellar Competent Cells: E. coli HST08 strain | TaKaRa | Cat#: 636766 |

| NiCo21 (DE3) Competent E. coli | New England BioLabs | Cat#: C2529H |

| Biological samples | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| TransIT-X2 | Mirus Bio | Cat#: MIR 6000 |

| Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | Gibco | Cat#: 10567014 |

| Fetal bovine serum (FBS) | Gibco | Cat#: 16140071 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Gibco | Cat#: 15140163 |

| Hygromycin B | Gibco | Cat#: 10687010 |

| Puromycin dihydrochloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: P8833 |

| TrypLE Express Enzyme | Gibco | Cat#: 12604013 |

| 2-Propanol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: I9516-500mL; CAS: 67-63-0 |

| Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | New England BioLabs | Cat#: M0491 |

| SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase | Invitrogen | Cat#: 18090010 |

| TOPO TA Cloning Kit for Sequencing | Invitrogen | Cat#: 450030 |

| Amine Coupling Kit | GE Healthcare/Cytiva | Cat#: BR100050 |

| Antarctic Phosphatase | New England BioLabs | Cat#: M0289 |

| [γ−32P]-ATP | American Radiolabeled Chemicals | Cat#: ARP 0102F-250 μCi |

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase | New England Biolabs | Cat#: M0201 |

| Acid-Phenol: Chloroform, pH 4.5 | Invitrogen | Cat#: AM9720 |

| Phenol: Chloroform, pH 8.05 | Invitrogen | Cat#: 15593031 |

| Yeast tRNA | Invitrogen | Cat#: AM7119 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | New England BioLabs | Cat#: B9001 |

| IPTG | Invitrogen | Cat#: 15529019 |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Roche | Cat#: 11873580001 |

| Lysozyme | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 89833 |

| PreScission Protease | GenScript | Cat#: Z02799 |

| PMSF | Roche | Cat#: 10837091001 |

| DNA Polymerase I, Large (Klenow) Fragment | New England BioLabs | Cat#: M0210 |

| Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 78426 |

| RNaseOUT Recombinant Ribonuclease Inhibitor | Invitrogen | Cat#: 10777019 |

| Ribonucleoside Vanadyl Complex | New England BioLabs | Cat#: S1402 |

| TURBO DNase | Invitrogen | Cat#: AM2238 |

| GalTY289L | Gift from K. Moremen | N/A |

| UDP-GalNAz | Chemily | Cat#: SN02012 |

| Amino-dPEG12-Tris (dPEG12-Tris(m-dPEG11)3)3 | Quanta BioDesign | Cat#: 10482 |

| DBCO-NHS ester | Click Chemistry Tools | Cat#: A133 |

| Iodoacetamide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: I1149 |

| Dichloromethane | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: D65100 |

| TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat#: 4444557 |

| TRIzol Reagent | Invitrogen | Cat#: 15596026 |

| 16% Formaldehyde (w/v), Methanol-free | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 28908 |

| TO1-3PEG-Biotin | Applied Biological Materials (abm) | Cat#: G955 |

| CKII peptide (PGGSTPVSSANMM) | Synthesized by JHMI Synthesis & Sequencing Facility | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 23227 |

| UDP-Glo Glycosyltransferase Assay kit | Promega | Cat#: V6971 |

| In-Fusion HD Cloning Plus kit | TaKaRa Bio | Cat#: 638909 |

| Purelink Fast Low Endotoxin Midi Plasmid Purification kit | Invitrogen | Cat#: A35892 |

| Pierce Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 88802 |

| Ni-NTA Agarose | Qiagen | Cat#: 30210 |

| Pierce Glutathione Agarose Beads | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 16100 |

| NuPAGE 4 to 12%, Bis-Tris, 1.0 mm, Midi Protein Gel, 20-well | Invitrogen | Cat#: WG1402BOX |

| Amersham Hybond P 0.2 PVDF membrane | GE Healthcare/Cytiva | Cat#: 10600021 |

| SuperSignal West Femto ECL Substrate | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 34095 |

| SuperSignal West Pico PLUS ECL Substrate | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 34577 |

| PARIS Kit | Invitrogen | Cat#: AM1921 |

| Duolink PLA Reagents | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#: DUO92001, DUO92005, DUO92013, DUO82049 |

| AlexaFluor 488 phalloidin | Invitrogen | Cat#: R37110 |

| AlexaFluor 555 phalloidin | Invitrogen | Cat#: R37112 |

| ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant with NucBlue Stain | Invitrogen | Cat#: P36985 |

| CUTANA ChIC/CUT&RUN Kit | EpiCypher | Cat#: 14-1048 |

| Qubit 1X dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Invitrogen | Cat#: Q33230 |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep with Sample Purification Beads | New England BioLabs | Cat#: E7103L |

| NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (96 Unique Dual Index Primer Pairs) | New England BioLabs | Cat#: E6440S |

| Nano-Glo Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System | Promega | Cat#: N1610 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Human Reference Genome GRCh38.p13 | Ensembl | http://www.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Info/Index |

| Escherichia coli Reference Genome ASM584v2 (str. K12 substr. MG1655) | Ensembl Bacteria | https://bacteria.ensembl.org/Escherichia_coli_str_k_12_substr_mg1655_gca_000005845/Info/Index |

| CUT&RUN Sequencing Data (Raw and Analyzed) | This paper | GEO: GSE190172 |

| CUT&RUN Sequencing Data, shβ-catenin samples (Raw and Analyzed) | This paper | GEO: GSE214775 |

| CUT&RUN Sequencing Data, Ac5S treated samples (Raw and Analyzed) | This paper | GEO: GSE214774 |

| RNA Sequencing Data (Raw and Analyzed) | This paper | GEO: GSE189378 |

| RNA Sequencing Data, Ac5S treated samples (Raw and Analyzed) | This paper | GEO: GSE189622 |

| RNA Sequencing Data, shEZH2 samples (Raw and Analyzed) | This paper | GEO: GSE214777 |

| Raw and analyzed data of this paper | This paper | Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17129945.v4 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HEK293T | ATCC | Cat#: CRL-3216, RRID: CVCL_0063 |

| L Wnt-3A | Willert et al.79 ATCC | Cat#: CRL-2647; RRID: CVCL_0635 |

| T1 | This paper | N/A |

| NL1F50 | This paper | N/A |

| 3JB8F+12 | This paper | N/A |

| shβ-catenin | This paper | N/A |

| shEZH2 | This paper | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| DNA oligos for SELEX, see Table S6 | This paper | N/A |

| Primers and Probes for TaqMan Assays, see Table S6 | This paper | N/A |

| Aptamer Sequences, see Table S7 | This paper | N/A |

| DNA oligo: NH2-T24: /5AmMC6/TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT | Chang et al.73 Synthesized by IDT | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pET24a-ncOGT-FL | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190821 |

| pET24a-ncOGT-TPR | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190822 |

| pET28a-β-catenin | Gift from R. Moon, unpublished | RRID: Addgene_17198 |

| pGEX-6P-1-CpOGA | Rao et al.35 | N/A |

| pEGFP-β-catenin_WT | Murase et al.76 | RRID: Addgene_16071 |

| pEGFP-β-cateninS23A, T40A, T41A, T112A | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190824 |

| pEGFP-C1-ERα | Stenoien et al.77 | RRID: Addgene_28230 |

| mEmerald c-SRC | Gift from M. Davidson, unpublished | RRID: Addgene_54118 |

| GFP-AMPKα2 | Hudson et al.78 | N/A |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-T1 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190825 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-AP3 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190826 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-17-6 (Non-aptamer RNA) | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190827 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-T1-U6-AP3 (T1 ∙ AP3) | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190828 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-NL1F30 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190829 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-NL1F35 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190830 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-NL1F50 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190831 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1F | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190832 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1F+2 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190833 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1F+4 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190834 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1F+6 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190835 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1F+8 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190836 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1F+10 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190837 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1F+12 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190838 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1R | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190839 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1R+2 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190840 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1R+4 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190841 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1R+6 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190842 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1R+8 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190843 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1R+10 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190844 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB1R+12 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190845 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-4JC1FF | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190846 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-4JC1RR | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190847 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-bc339 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190848 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-T1-U6-bc339 (T1 ∙ bc339) | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190849 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-NL8F50 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190850 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-NL8F70 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190851 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-NL8F100 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190852 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB8F+4 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190853 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB8F+12 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190854 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-3JB8R+12 | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190855 |

| pSilencer2.1-U6-LRS1F50C | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190856 |

| TOPFlash | Veeman et al.85 | RRID: Addgene_12456 |

| FOPFlash | Veeman et al.85 | RRID: Addgene_12457 |

| pNL1.1.TK[Nluc/TK] | Promega | Cat#: N1501 |

| TRC2-pLKO.5-scrambled | Sigma | Cat#: SHC216 |

| TRC2-pLKO.5-shOGT | Sigma | Cat#: TRCN0000286200 |

| TRC2-pLKO-shβ-catenin | Sigma | Cat#: TRCN0000314921 |

| pLKO.1-shEZH2 | Sigma | Cat#: TRCN0000040077 |

| pMD2.G | Gift from D. Trono, unpublished | RRID: Addgene_12259 |

| psPAX2 | Gift from D. Trono, unpublished | RRID: Addgene_12260 |

| pcDNA3.1-OGT_opt | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190858 |

| pcDNA3.1-empty | This paper | RRID: Addgene_190859 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| cutadapt | Martin65 | https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/ |

| Trim Galore! | Krueger et al.88 | https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore |

| FASTAptamer | Alam et al.66 | https://github.com/FASTAptamer/FASTAptamer |

| RNAfold webserver | Lorenz et al.67 | http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi |

| RNAStructure, version 6.3 | Reuter and Mathews68 | https://rna.urmc.rochester.edu/RNAstructure.html |

| RNAComposer | Popenda et al.69 Antczak et al.70 | http://rnacomposer.cs.put.poznan.pl/ |

| QRNAS | Stasiewicz et al.71 | http://genesilico.pl/software/standalone/qrnas |

| UCSF ChimeraX | Pettersen et al.72 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| Biacore Evaluation Software | GE Healthcare/Cytiva | 29310602 |

| ggplot2 | Wickham74 | https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org |

| Fiji | Schindelin et al.75 | https://imagej.net/software/fiji/ |

| BioVoxxel Toolbox | Brocher86 | https://imagej.net/plugins/biovoxxel-toolbox |

| HISAT2 | Kim et al.89 | http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/ |

| featureCounts | Liao et al.90 | http://subread.sourceforge.net/ |

| annotateMyIDs | Dunning91 | https://github.com/markdunning/galaxy-annotateMyIDs |

| DESeq2 | Love et al.92 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| EnhancedVolcano | Blighe et al.93 | https://github.com/kevinblighe/EnhancedVolcano |

| Bowtie2 | Langmead and Salzberg96 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| samtools | Li et al.97 | http://www.htslib.org/ |

| bedtools | Quinlan and Hall98 | https://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ |

| SEACR | Meers et al.99 | https://github.com/FredHutch/SEACR |

| The Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) | Robinson et al.105 | http://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/home |

| Diffbind | Stark and Brown100 Ross-Innes et al.101 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DiffBind.html |

| ChIPseeker | Yu et al.102 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/ChIPseeker.html |

| profileplry | Carroll and Barrows103 | https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/profileplyr.html |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Other | ||

| Biacore T100 SPR system | GE Healthcare/Cytiva | |

| Sensor Chip PEG, Series S | GE Healthcare/Cytiva | Cat#: 29239810 |

| Slide-A-Lyzer G2 Dialysis Cassettes, 20K MWCO | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 87735 |

| Vivaspin protein concentrator, 30K MWCO | GE Healthcare/Cytiva | Cat#: 28932235 |

| SpectraMax i3x | Molecular Devices | |

| iBright FL 1500 Imaging System | Invitrogen | Cat#: A44115 |

| 8-well Chamber Slide w/ removable wells | Thermo Scientific | Cat#: 154941 |

| HybEZ II Hybridization System | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat#: 321710 |

| Amersham Imager 600 RGB | GE Healthcare/Cytiva | Cat#: 29-0834-67 |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell Lines

The HEK293T (CRL-3216) and L Wnt-3A (CRL-2647) cell lines were obtained from ATCC. The T1, NL1F50 and 3JB8F+12 cell lines were generated by transfecting the respective plasmids into HEK293T cells using TransIT-X2 (Mirus Bio, MIR 6000), and selected with 500 μg/mL hygromycin. Cell lines expressing shβ-catenin and shEZH2 were generated by lentiviral transduction of HEK293T cells, and selected with 1 μg/mL puromycin. Experimental details are described below.

METHOD DETAILS

SELEX

Library Construction

Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) was based on previous publications60–62. DNA oligos used in SELEX are listed in Table S6. The initial single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) libraries (L1-N60-ncs for OGT aptamers, L2-N50-ncs for β-catenin aptamers) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA), using a customized recipe (A: 29%, C: 29%, G: 19%, T: 23%) for the random regions. ssDNA libraries were purified by Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE, Invitrogen EC6875BOX) and eluted from gel with Probe Elution Buffer (0.5 M Sodium Acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS). Purified ssDNA was converted to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) by annealing to L1–5’-T7-cs (for OGT aptamers) or L2–5’-T7-cs (for β-catenin aptamers) and Klenow extension (NEB M0210). RNA libraries were synthesized from PAGE-purified dsDNA libraries by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (NEB M0251). RNA libraries were PAGE-purified, precipitated with isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich I9516–500mL), washed with 70% ethanol and dissolved in nuclease-free water.

Partition and Amplification

To improve target specificity and to minimize PCR bias, “Toggle SELEX” and “RAPID-SELEX” was applied in the partition and amplification steps63,64. Detailed schemes of partition and amplification are described in Table S2. Partition of library was performed in Aptamer Binding Buffer (ABB, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.5) for OGT aptamers, or Intracellular Buffer (IB, 20 mM HEPES, 110 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 0.4 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KH2PO4, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.2) for β-catenin aptamers. Each RNA library and its desired target protein were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr with rotation. The target proteins were either pre-immobilized on His-tag binding magnetic beads (MB, Invitrogen 10103D), or captured by nitrocellulose membrane disks (NC, Millipore HATF02500) after incubation. Unbound RNA sequences were washed away with 1 mL of ABB or IB. Elution of bound RNA was either by Proteinase K (Thermo Scientific EO0492) digestion at 37 °C for 30 min followed by denaturation in 100μL formamide (Thermo Scientific 17899) at 95°C for 2 minutes, or with 300 mM imidazole. Eluted RNA was converted to cDNA using SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen 18090010) and RT primers (L1–3’-const-ncs for OGT aptamers; L2–3’-const-ncs for β-catenin aptamers), then PCR amplified using Taq Polymerase (NEB M0273L) for 16 cycles. Counter selection (CS) was included in indicated rounds with 1 μg Hexa-His peptide (Abbiotec 350220) immobilized onto MB. In certain rounds of selection, eluted RNA was proceeded to the next selection cycles without amplification, in order to reduce amplification bias and time consumption64. Eluted RNA in the final cycles was converted to cDNA by RT-PCR (Invitrogen 18090010).

Library Sequencing and Data Analysis

For OGT aptamers, the final DNA library was cloned into the pCR4-TOPO plasmid using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen 450030) and transformed into Chemically Competent E. coli cells (TaKaRa 636766). 84 colonies were subjected to plasmid purification and Sanger-sequencing at the JHMI Synthesis & Sequencing Facility. Frequency of all resulted sequences were calculated, and the most represented sequence (T1) was chosen for validation.

For β-catenin aptamers, enriched DNA libraries from rounds 5 and 8 were submitted for Next-Generation Sequencing at the JHMI Transcriptomics and Deep Sequencing Core Facility, on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer.

Analysis of the sequencing data started from trimming of the sequencing adaptors and the constant flanking regions using cutadapt65. Enrichment analysis was carried out using FASTAptamer66. Frequencies of all sequences in each library were counted and clustered based on their similarity. Enrichment of each cluster was assessed across different SELEX rounds. The most enriched sequence (bc339) was chosen for validation.

RNA Structure Prediction

Secondary structures of RNA were predicted using the RNAfold webserver67 and drawn with StructureEditor in the RNAStructure 6.3 package68. Tertiary structures were predicted using RNAComposer69,70, refined by QRNAS71, and visualized with UCSF ChimeraX72.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

For SPR, Multi Cycle Kinetics was performed on a Biacore T100 (GE Healthcare/Cytiva) instrument at 25 °C, following the protocol by Chang et al.73. In assay preparation, an amine-modified T24 DNA linker (NH2-T24) was immobilized to ~100 RU in both reference and test flow cells on a sensorchip PEG (GE Healthcare/Cytiva 29239810), using the Amine Coupling Kit (GE Healthcare/Cytiva BR100050). RNA of T1 or bc339 with a A28 tail on the 3’-end were diluted to 100 nM in ABB (T1) or IB + 200 mM NaCl (bc339). Diluted RNA solutions were denatured at 65 °C for 5 min and re-folded at room temperature for 5 min. At the beginning of each cycle, the A28-tagged RNA solutions were injected into the test flow cell and captured by the immobilized T24 DNA linker. Protein analytes were diluted in ABB (OGT) or IB (β-catenin) and injected sequentially into both reference and test flow cells, at a rate of 30 μL/min. Concentrations tested are listed in the figure legends. Each concentration was duplicated. At the end of each cycle, surface was regenerated with 25 mM of NaOH for 30 sec at 30 μL/min, which removed the captured RNA and protein. Data was analyzed using the Biacore Evaluation Software (GE Healthcare/Cytiva), where the overlaid sensorgrams were fitted into a 1:1 binding model. Curves were exported and replotted with ggplot274 for better illustration.

Radiolabeled Dot-Blot Assay

Radio-Labeling of RNA

For end preparation, the terminal phosphate groups of RNA were removed by Antarctic Phosphatase (NEB M0289). Then the 5’-end of 200 pmol RNA was labeled with 10 μCi of [γ−32P]-ATP (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, ARP 0102F-250 μCi) using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (NEB M0201). Labeled RNA was extracted with Acid-Phenol: Chloroform, pH4.5 (Invitrogen AM9720), precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol, and dissolved in nuclease-free water.

Dot-Blot Assay

Radiolabeled RNA was diluted in ABB, denatured at 65 °C for 5 min and re-folded at room temperature for 5 min. Then 100 nM of RNA was incubated with multiple concentrations (see figure legends) of purified ncOGT at 37 °C for 30 min. The volume of each assay was 50 μL. 1 μM yeast tRNA (Invitrogen AM7119) and 50 μg/mL Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, NEB B9001S) were included as non-specific competitors. After incubation, the reactions were filtered sequentially through a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham 10600042) and a Nylon membrane (Invitrogen AM10102), on a Bio-Dot Microfiltration Apparatus (Bio-Rad 170–6545). Membranes were washed with 100 μL ABB to remove unbound RNA. Washed membranes were air-dried and exposed to a film (Amersham 28906836) for 2 hr. The film was developed and scanned, and the image was analyzed with Fiji75. Quantified data was fitted into a Michaelis-Menten model using GraphPad Prism.

Protein Expression and Purification

Bacterial Expression of Recombinant Proteins

For OGT-FL, TPR and β-catenin: NiCo21 (DE3) Competent E.coli (NEB C2529H) transformed with a plasmid (pET24a-ncOGT-FL, pET24a-TPR or pET28a-β-catenin) was inoculated into 50 mL LB medium for overnight culture at 37 °C, 250 rpm. On Day 2, the whole culture was transferred into 500 mL LB medium, and the growth was observed by measuring its OD600 every 30 min. When the OD600 reached 1.2, the whole culture was cooled on ice for 15 min. Protein expression was induced by adding 200 μM (OGT-FL and TPR) or 500 μM (β-catenin) IPTG (Invitrogen 15529019). Then the culture was continued at 16 °C, 180 rpm for 24 hr. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C, 5000 rcf for 15 min and washed with cold PBS.

For CpOGA: NiCo21 (DE3) cells transformed with pGEX-6P-1-CpOGA35 was cultured and induced in the same way as above, except that protein expression was induced with 200 μM IPTG at 22°C, 250 rpm for 24 hr.

Protein Purification

For OGT-FL, TPR and β-catenin: All steps in protein purification were performed at 4 °C. Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche 11873580001) was added into the Stock, Lysis, Wash and Elution Buffers below. Bacterial pellet was re-suspended in 10 mL Stock Buffer (50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Cells were lysed by adding 10 mL Lysis Buffer (Stock Buffer + 10 mM Imidazole, 1% Triton X-100, and 10 mg/ml Lysozyme (Thermo Scientific 89833)) and incubate on ice for 30 min. Lysate was homogenized by sonication on ice for 5 cycles of 12 sec ON, 30 sec OFF at power 4 (Fisher Scientific F550), centrifugation at 13,000 rcf for 15 min and collection of the supernatant. The supernatant was loaded onto a chromatography column packed with 2 mL Ni-NTA agarose slurry (Qiagen 30210) and passed the column twice under gravity flow. Then the column was washed with 45 mL Wash Buffer (Stock Buffer + 30 mM Imidazole), and protein was eluted with 4 mL Elution Buffer (Stock Buffer + 250 mM Imidazole). Elute was dialyzed three times against 4 L of Dialysis Buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl and 0.2 mM PMSF (Roche 10837091001) in a dialysis cassette (20K MWCO, Thermo Scientific 87735). The first and third dialysis were for 3 hr, and the second was for overnight. Dialyzed protein solution was concentrated with a Vivaspin protein concentrator (30K MWCO, Cytiva 28932235). Protein concentration was measured by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific 23227). Purified proteins were stored at −80 °C for up to a year.

For CpOGA: Bacterial pellet was re-suspended and lysed in the same way as above, except that the Stock Buffer and Lysis Buffer were replaced with Buffer A (50 mM HEPES, 250 mM NaCl, pH7.5) and Lysis Buffer A (Buffer A + 10 mg/mL lysozyme). The cleared lysate was loaded to an equilibrated column packed with 2 mL Glutathione Agarose Beads (Thermo Scientific 16100). The loaded column was capped and rotated for 2.5 hr at 4 °C, to capture the GST-tagged CpOGA from lysate. Then lysate was allowed to pass through the column by gravity, and the beads was washed with 20 mL Buffer A. The CpOGA protein was eluted by cleaving the GST-tag. The cleavage was performed by adding 100 U PreScission Protease (GenScript Z02799–100U) in 5 mL Cleavage Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.0 at 25 °C) to the column, and rotating for overnight at 4 °C. The elute was collected and dialyzed against 4 L of 1x TBS for overnight at 4 °C in a dialysis cassette (20K MWCO, Thermo Scientific 87735). The dialyzed protein solution was concentrated, quantified and stored as above.

OGT Activity Assay (UDP-Glo)

Activity of OGT was measured using the UDP-Glo Glycosyltransferase Assay kit (Promega V6971), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Assays were performed on a white 96-well half-area plate (Corning CLS3992–25EA). Each reaction contains 0.625 ng OGT, 50 μM CKII peptide substrate (PGGSTPVSSANMM, JHMI Synthesis & Sequencing Facility), 10 μM yeast tRNA and various concentrations (see figure legends) of RNA aptamer in 12.5 μL ABB. Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and 12.5 μL UDP Detection Reagent was added to each reaction. After incubation at room temperature for 1 hr, luminescence was measured on a Plate Reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Cells were cultured in DMEM with 1 g/L glucose, pyruvate and GlutaMAX (Gibco, 10567022), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated Fetal bovine serum (Gibco 16140071), 200 U/mL penicillin and 200 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco 15140163). Culture medium was changed daily. Cells were cultured in a 37 °C incubator (Heracell VIOS 160i) with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. For subculturing, cells were rinsed with PBS, monodispersed with TrypLE (Gicbo 12604013) and counted on a cell counter (Nexcelom Auto 1000). Cells were discarded when their passage numbers reached 15.

For plasmid transfection in 10 cm dishes, 2×106 HEK293T cells were seeded per dish, and transfection was done after 24 hr (at 40% – 60% confluency). Desired amounts of plasmids were dissolved in 100 μL Opti-MEM medium (Gibco 51985034), and TransIT-X2 Transfection Reagent (Mirus Bio, MIR 6000) was added at a ratio of 4 μL of Reagent per 1 μg of DNA. The mixture was gently mixed, incubated at room temperature for 20 min and distributed evenly into the culture dish. Medium was changed to fresh DMEM at 6 hr post-transfection. Plasmid usage in transfection: To target OGT to GFP-β-catenin, 0.1 μg of GFP-β-catenin76 and 1 μg of each aptamer-encoding plasmid were co-transfected per 10 cm dish. To target OGT to other GFP-tagged proteins, 0.5 μg of GFP-Src (gift from M. Davidson, unpublished), or 1 μg of GFP-ERα/GFP-AMPKα277,78 and 2 μg of each aptamer-encoding plasmid were co-transfected per 10 cm dish. To target OGT to endogenous β-catenin, 1.5 μg of each plasmid was transfected per 10 cm dish. For cells cultured in different containers, the number of cells, amounts of DNA and transfection reagent were adjusted according to the bottom area of the container.

For cell treatments, Ac4-5SGlcNAc (Ac5S) was added into medium at 50 μM, for 20 hr; Thiamet-G (TMG) was used at 2 μM for 6 hr; TO1-biotin (TO1) was used at 750 nM for 8 hr. Wnt stimulation was by 50% (v/v) Wnt3A-conditioned medium for 4 hr.

Generation of Stable Cell Lines

For cells stably expressing T1, NL1F50 and 3JB8F+12: the desired plasmids were transfected into HEK293T cells as above and selected with 500 μg/mL hygromycin B (Gibco 10687010) in culture medium. The selection started at 24 hr post-transfection and lasted for ~3 weeks, till most of cells died and the survived cells grew confluent. Then the cells were sub-cultured and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Cells expressing shβ-catenin and shEZH2 were generated by lentiviral transduction.

Production of Lentivirus

6×105 HEK293T cells were seeded on a 6 cm dish. After 24 hr, 1 μg of shβ-catenin (Sigma TRCN0000314921) or 1 μg of shEZH2 (Sigma TRCN0000040077) plasmids was co-transfected with 0.75 μg of psPAX2 (Addgene 12260) and 0.25 μg of pMD2.G (Addgene 12259). Culture medium was replenished at 6 hr post-transfection. Culture continued without medium change, and the first batch of medium was harvested at 48 hr post-transfection. Medium was replenished and the second bath of medium was harvested at 72 hr post-transfection. The two batches were combined, spun at 1250 rpm for 5 min to remove cell pellet, and stored at −80 °C in 1 mL aliquots.

Lentiviral Transduction and Selection

6×105 HEK293T cells were seeded on a 6 cm dish. After 24 hr, culture medium was changed to fresh DMEM with 8 μg/mL DEAE-Dextran, and 1 mL of thawed lentivirus solutions was added to the cell, and mixed by gently rocking. Culture medium was changed at 24 hr post-transfection. Antibiotic selection started at 48 hr post-transfection with 1 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich P8833) in medium, and continued till most cells died and the survived cells grew confluent. Then the cells were sub-cultured and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Production of Wnt3A-Conditioned Medium

L Wnt-3A cells79 was sub-cultured at 1:10 in 15 cm dishes. Medium glucose level was monitored twice daily with OneTouch Ultra 2 meter and OneTouch Ultra Blue test strips. When glucose was below 20 mg/dL, it was replenished with 100 g/L glucose solution (Sigma-Aldrich G8270) that was filtered through 0.2 μm PES filter (Whatman 6896–2502), to about 120 mg/dL. The first batch of medium was harvested on the fourth day of culture, and fresh DMEM was added to the cells. Culture continued for another three days, and the second batch of medium was harvested. The two batches were combined, filtered through a 0.2 μm PES bottle-top filter (Fisher Scientific FB12566510), and stored at 4 °C for up to 6 months. This conditioned medium was diluted to 50% (v/v) with regular DMEM for cell treatment.

Molecular Cloning

For molecular cloning, we used the seamless cloning method using the In-Fusion HD Cloning Plus kit (TaKaRa Bio 638909), following manufacturer’s protocol.