Abstract

Examining neural circuits underlying persistent, heavy drinking provides insight into the neurobiological mechanisms driving alcohol use disorder. Facilitated by its connectivity with other parts of the brain such as the nucleus accumbens (NAc), the ventral hippocampus (vHC) supports many behaviors, including those related to reward seeking and addiction. These studies used a well-established mouse model of alcohol (ethanol) dependence. After surgery to infuse DREADD expressing viruses (hM4Di, hM3Dq or mCherry-only) into the vHC and position guide cannula above the NAc, male C57BL/6J mice were treated in the CIE drinking model that involved repeated cycles of chronic intermittent alcohol (CIE) vapor or air (CTL) exposure alternating with weekly test drinking cycles in which mice were offered alcohol (15% v/v) 2-hr/day. Additionally, smaller groups of mice were evaluated for either cFos expression or glutamate release using microdialysis procedures. In CIE mice expressing inhibitory (hM4Di) DREADDs in the vHC, drinking increased as expected, but CNO (3 mg/kg ip) given 30-min before testing did not alter alcohol intake. However, in CTL mice expressing hM4Di, CNO significantly increased alcohol drinking (~30%; p<0.05) to levels similar to the CIE mice. The vHC-NAc pathway was targeted by infusing CNO into the NAc (3 or 10 μM/side) 30-min before testing. CNO activation of the pathway in mice expressing excitatory (hM3Dq) DREADDs selectively reduced consumption in CIE mice back to CTL levels (~35–45%; p<0.05) without affecting CTL alcohol intake. Lastly, activating the vHC-NAc pathway increased cFos expression and evoked significant glutamate release from the vHC terminals in the NAc. These data indicate that reduced activity of the vHC increases alcohol consumption and that targeted, increased activity of the vHC-NAc pathway attenuates excessive drinking associated with alcohol dependence. Thus, these findings indicate that the vHC and its glutamatergic projections to the NAc are involved in excessive alcohol drinking.

Introduction

In medical and economic terms, heavy alcohol drinking causes significant harm to the individual and to society (Carvalho et al., 2019; Rehm et al., 2014; Rehm et al., 2017) and, unfortunately, developing data indicates the recent COVID-19 pandemic has likely worsened these issues (Bailey et al., 2022; Barbosa et al., 2021). Over time, the amount of alcohol drinking can be influenced by a shifting balance between motivational (reward) and aversive processes (Koob & Volkow, 2016) and alcohol’s effects are modified by tolerance, further compounding the problem (Elvig et al., 2021). The persistent exposure to and withdrawal from alcohol produces neurobiological adaptations which can maintain harmful levels of intake. Examining the complex interplay of neural circuits and neurotransmitters, within and between brain regions, provides opportunities to understand the mechanisms driving alcohol use disorder.

Imaging studies found hippocampal atrophy in those with alcohol use disorder compared to healthy controls (Agartz et al., 1999; Beresford et al., 2006; Nagel et al., 2005) and demonstrate that this brain region is not spared the insult of alcohol injury in humans. It is well known that the hippocampus plays a prominent role in mediating spatial orientation, navigation and learning and memory. Lesion and inactivation studies in animal models indicate that the more anterior and dorsal areas of the hippocampus seem to have the largest role in spatial orienting and learning, though these areas do participate in other behaviors (Bannerman et al., 2004; Fanselow & Dong, 2010; Kanoski & Grill, 2015; Pennartz et al., 2011; Strange et al., 2014). The more posterior and ventral areas (ventral hippocampus, vHC) are also involved in processing salient contexts based on studies using social reward (LeGates et al., 2018) and context-mediated drug- (Bossert et al., 2016; Lasseter et al., 2010; Rogers & See, 2007; Sun & Rebec, 2003) and alcohol reinstatement (Marchant et al., 2016).

Interestingly, other reports indicate that the vHC is involved in behaviors beyond processing salience of external cues. For example, lesions or inactivations of the vHC increase food reward (Briggs et al., 2021; Ferbinteanu & McDonald, 2001; Hannapel et al., 2019; Hannapel et al., 2017), increase feeding behavior in novel situations (Bannerman et al., 2002a; Bannerman et al., 2002b), decrease fear and anxiety (Kjelstrup et al., 2002; Maren & Holt, 2004) and increase exploration of aversive contexts (Ito & Lee, 2016; Schumacher et al., 2016). Recent data also suggest a role for the vHC in regulating habit and goal motivated behaviors (Barker et al., 2019; Barker et al., 2016). Together, these reports indicate that experimentally reducing the vHC’s influence will facilitate some behaviors, and in turn, suggest that normal vHC function serves to keep some behaviors in check (Schwarting & Busse, 2017). The complexity of the hippocampus in modulating behaviors is only just beginning to be appreciated (Bryant & Barker, 2020).

In keeping with its complex role, the hippocampus connects widely to other areas of the brain. There is a particularly dense projection from the vHC to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), arising principally from the ventral subiculum and CA1 subregions (Aylward & Totterdell, 1993; Groenewegen et al., 1987; Kelley & Domesick, 1982; Phillipson & Griffiths, 1985; van Groen & Wyss, 1990). Anatomical (Christie et al., 1987), optogenetic (Britt et al., 2012) and electrophysiological evidence (MacAskill et al., 2012; Scudder et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2017) indicate that this pathway is glutamatergic and activates other neurons. Further, previous research reports show that glutamatergic neurotransmission within the NAc is affected by alcohol dependence (Griffin et al., 2014; Griffin et al., 2015) and these adaptations might involve the glutamatergic pathway between the vHC and NAc (Britt et al., 2012; Kircher et al., 2019). The overarching hypothesis guiding these research studies was that the vHC and its projection to the NAc negatively regulate alcohol drinking. To test this hypothesis, a well-established model of alcohol dependence and relapse was used in combination with viral-mediated chemogenetics and site-specific drug administration into the NAc.

METHODS

Subjects

Male C57BL/6J mice (10 weeks of age) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), individually housed and maintained in an AAALAC accredited animal facility under a 12 hr light cycle (lights off 0800). Housing cages were opaque polypropylene measuring 7.5” X 11.5” X 5” with wire lids (Model# N10; Ancore Corp, Bellmore, NY) lined with corncob bedding (1/4” Bed o’cobs, The Andersons Plant Nutrient Co., Maumee, OH). The wire lid held food pellets and glass 50ml water bottles. The food provided was Diet #2918 (Harland Teklad, Madison, WI). The vivarium rooms were maintained at temperatures of 23 ±2°C and 40 ±10% humidity. Mice had free access to food and tap water at all times. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of South Carolina and were consistent with the guidelines of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

General Experimental Design

Mice were given access to alcohol using limited access procedures (described below). After establishing stable alcohol intake, mice were separated into chronic intermittent alcohol exposure (CIE; alcohol dependent) and control (CTL; non-dependent) groups. Briefly, the EtOH group received chronic intermittent exposure to alcohol vapor in inhalation chambers (16 hr/day for four days) while CTL mice were similarly handled but received air exposure (more details below). Limited access drinking sessions were suspended during inhalation exposure. After CIE exposure, mice entered a 72 hr abstinence period and then were tested for voluntary alcohol intake for five consecutive days using limited access conditions as before. Cycles of CIE exposure interspersed with Test weeks of voluntary drinking were repeated several times for both experiments. Figure 1A shows the experimental design used for studies involving limited access alcohol drinking and CIE procedures.

Figure 1.

A) A schematic showing the general experimental design. After surgery, recovery and establishing baseline drinking, dependent (CIE) mice and non-dependent (CTL) mice alternated between weeks of CIE or CTL procedures and weeks of free-choice drinking access. B) Following repeated cycles of exposure, the CIE mice increased alcohol consumption compared to their own baseline level of drinking and the CTL mice at the same time point (^p<0.05 versus baseline; *p<0.05 within time point) but there was no effect of virus expression (mCherry vs hM4Di; n= 8–11/group). C) During the CNO challenge sessions, the CIE mice continued to show the increased drinking phenotype (*p<0.05 between groups). CNO (3 mg/kg ip.) significantly increased drinking in the CTL mice expressing hM4Di (#p<0.05 compared to vehicle) but was without effect in the CIE mice expressing hM4Di. As expected, CNO had no effects in mCherry expressing mice from either group (n=8–11/group). D) An example of mCherry expression within the vHC using DAB staining procedures. E) Shading showing the general extent of bilateral mCherry expression. All data are means ± S.E.M.

Stereotaxic Surgery

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane mixed with medical-grade air (4% induction, 2% maintenance), given a subcutaneous injection of 5 mg/kg carprofen (Pfizer, Inc), and placed in a Kopf stereotaxic instrument with digital display (Model 942). Mice received bilateral infusion of either a virus containing an inhibitory (hM4DI) DREADD or excitatory (hM3Dq) DREADD (AAV(8)-CaMKIIa-hM4Di-mCherry or AAV(8)-CaMKIIa-hM3Dq-mCherry; Addgene, Inc.) or a control virus expressing only mCherry (AAV(8)-CaMKIIa-mCherry; Addgene, Inc.) into the vHC [AP: −3.4 mm, ML: ±3.0 mm, DV: −4.75mm], relative to Bregma (Franklin & Paxinos, 2008). Viral titers were generally >7×1012 and used undiluted. For studies involving microinjections, during the same surgery as the viral infusions, bilateral microinjection guides (Plastics One, Inc) were positioned over the NAc (AP: 1.7 mm; ML: + / − 0.75 mm; DV: −3.9 mm) and secured with light-cured dental resin (Griffin & Middaugh, 2006; Griffin et al., 2007). Mice were given at least 2 weeks of recovery time prior to beginning any experiment.

Limited Access Drinking Procedures

Mice were offered alcohol (15% v/v) to drink in their home cage using 95% ethanol from AAPER (Shelbyville, KY) diluted with tap water (Becker & Lopez, 2004; Griffin, 2014; Griffin et al., 2009b; Lopez & Becker, 2005) but without using a sucrose fading procedure. The 2-hr access periods began 3 hours into the dark phase Monday through Friday. At the start of the access period, the 50 ml water bottle was removed and mice were provided two 15 ml glass bottles with sipper tubes (2” straight, open tip), one bottle containing the alcohol solution and the other tap water. The bottles were placed on opposite sides of the wire cage lid and the side on which the alcohol and water bottles were placed was alternated randomly to avoid side preferences. The amount of alcohol consumed was determined by weighing bottles before and after the access period. Spillage from handling the bottles was corrected for by measuring weights from bottles maintained on empty cages and subtracting these values from the mouse intake values. Mouse body weights were recorded weekly.

Chronic Intermittent Ethanol (CIE) Exposure Procedures

Chronic intermittent ethanol vapor (or air) exposure was delivered in Plexiglas inhalation chambers as previously described (Becker & Lopez, 2004; Griffin, 2014; Griffin et al., 2009b; Lopez & Becker, 2005). Chamber ethanol concentrations were monitored each day and air flow was adjusted to maintain concentrations within a range that yielded stable blood ethanol levels throughout exposure (175–225 mg/dl). Mice were placed in inhalation chambers at 1600 hr and removed 16-hr later at 0800 hr. Before each 16-hr exposure during CIE treatment, EtOH mice were administered ethanol (1.6 g/kg; 8% w/v) and the alcohol dehydrogenase inhibitor pyrazole (1 mmol/kg) to maintain a stable level of intoxication during each cycle of ethanol vapor exposure (Griffin et al., 2009a). CTL mice were handled similarly but received injections of saline and pyrazole. All injections for these procedures were given intraperitoneally in a volume of 20 ml/kg body weight.

Systemic Clozapine-N-Oxide Injections.

Mice were habituated to intraperitoneal (ip.) injections of normal saline (10 ml/kg) given 30 min prior to each alcohol access session throughout the entire study. During the 4th Test week, mice were administered Clozapine-N-Oxide (CNO; Tocris, Inc) dissolved in saline (0.9%) in a cross-over design such that all mice were tested with vehicle and one dose of CNO (3mg/kg; ip.) on separate days. In this case, half of the mice were given saline and the other half were given CNO on Tuesday and the vehicle/drug assignment was reversed on Thursday.

Intra-NAc Microinjection Procedures.

Microinjections were conducted similarly as previously described (Griffin et al., 2014; Haun et al., 2020; Haun et al., 2018). Mice were habituated to the microinjection handling procedures 2–3 times per week beginning with the baseline drinking phase. For any given Test week, microinjections were only administered once per mouse and microinjections were limited to Test 3, 4 or 5 (i.e. after the development of escalated alcohol drinking in the alcohol dependent mice) on Wednesday or Thursday. For these experiments, including an additional Test week allowed more opportunities for microinjections, a time- consuming procedure limiting the number of mice that can be treated prior to drinking while holding the pre-treatment time and drinking start times consistent. Further, mice had 2 microinjections, one of vehicle and one of the active CNO dose in a cross-over design, though some mice only had one injection due to a unilateral or bilateral clog developing after the first injection. A few mice included in the study had 3 microinjections due to experimental errors on the 1st or 2nd microinjection (line leaks, pump on too long). Because the within-subject factor was not consistently held, these data were analyzed using between-subjects ANOVA.

For the procedure itself, 30 min prior to drinking sessions mice were removed from their home cage and gently restrained by hand to insert the bilateral injectors, which extended 0.5 mm beyond the end of the guides. CNO (0, 3 or 10 μM) was diluted in 1X phosphate-buffered saline (Vehicle; diluted from 10X stock Boston Bioproducts, Inc) and delivered at 0.25 μl/min over 2 min with using Harvard Apparatus Pump 11 (Harvard Apparatus, Inc., Holliston, MA). These procedures delivered either 0.571 nanograms/side (3μM) or 1.714 nanograms/side (10μM) of CNO. The injectors were left in place for an additional 2 min to allow for diffusion and the mouse was returned to their home cage.

DAB staining to confirm viral expression.

At the end of the study, mice were sacrificed with deep anesthesia (3 g/kg urethane) followed by transcardiac perfusion using approximately 10 ml ice-cold 1X PBS (diluted from 10X stock Boston Bioproducts, Inc) followed by approximately 12 ml ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brain was post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA and then placed in 30% sucrose until sectioning. Brains were sectioned (40 microns) using a cryostat and floated in 1X PBS prior to immunostaining. All solutions were diluted in PBS with 0.3% Triton-X (PBST), and sections were rinsed in PBS 3 times between each step. Sections were first incubated in a 1% hydrogen peroxide solution for 60 min followed by overnight incubation in primary antibody (1:20,000 rat anti-mCherry, Life Technologies #M11217) diluted in blocking solution (5% normal goat serum in PBST). Sections were then placed in secondary antibody (1:1000 biotinylated goat anti-rat, Jackson Immuno #112–066-003) for 30 min and 1:1000 ABC (Vector Elite Kit, Vector Labs) for 60 min. All rinses and incubations occurred on a rocker at room temperature. Finally, sections were incubated in a solution of 0.05% 3,3’-diaminobenzidine and 0.015% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min.

Fluorescent mCherry and cFos Staining.

This study used mice expressing only unilateral hM3Dq in the vHC (details above, viral infusion only one side) and used to evaluate cFos expression in the NAc. After several weeks of undisturbed recovery from surgery in their home cage in a quiet colony room, mice were administered vehicle (normal saline) or CNO (3mg/kg) via the intraperitoneal route and 90 min later, sacrificed as described in the general Histology methods. All mice were sacrificed between 9 and 11 AM (beginning of dark phase) over 3 days with drug or vehicle groups represented on all days. The brain was post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA and then 30% sucrose until sectioning. Similarly, brains were sectioned at 40 microns and floated in 1X PBS for immunostaining. Sections were incubated in a 1% hydrogen peroxide solution for 60 min followed by overnight incubation in primary antibody (Rat anti-mCherry, Life Technologies #M11217; 1:4000) and later a 60 min incubation with secondary goat anti-rat antibody conjugated to AlexaFluor647 (Goat anti-rat; Invitrogen, Inc; A21247; 1:1000). The primary cFos antibody was from EMD-Millipore (Rabbit anti-cFos; AB457; 1:1000) and the secondary antibody (1:1000) was conjugated to AlexaFluor488 (Goat Anti-rabbit; Invitrogen, Inc; A11034; 1:1000). All rinses and incubations occurred on a rocker at room temperature. Unilateral fluorescent images were captured at 20X magnification using an EVOS inverted digital microscope from the side of the NAc ipsilateral to the viral infusion into the vHC. Counting cFos expressing neurons was automated using ImageJ with the Cell Counter plugin by first converting each image to 16-bit greyscale and setting each image to the same pixel intensity.

Glutamate Microdialysis and HPLC detection.

This study was conducted similarly, with some modifications, to those previously reported (Griffin et al., 2014; Griffin & Middaugh, 2006; Griffin et al., 2015; Griffin et al., 2007). Mice expressed only unilateral hM3Dq in the vHC (details above). During the viral infusion surgery, ipsilateral to the infusion site, a microdialysis guide was positioned above the NAc (CMA7; CMA Microdialysis, Sweden, Inc) using similar coordinates to the microinjection guides, except the DV was −3.7 mm relative to bregma. Mice recovered from surgery for 2 weeks and then began 3 cycles of CIE exposure (or CTL procedures), alternating with weeks of home cage rest, consistent with the design shown in Figure 1A (except there was no voluntary alcohol drinking for this experiment). Approximately 72 to 96 hours after concluding the 3rd week of CIE exposure a CMA7 probe (1mm) was implanted and equilibrated overnight at 0.2 μl/ml using artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). The next day, flow was increased to 0.75 microliters/min through the probe for 2 hrs prior to beginning collection. After collecting three 25-minute baseline samples with plain aCSF, 300 micromolar CNO dissolved in aCSF was reversed perfused for 25 minutes and then plain aCSF resumed for 6 additional samples. Note, the higher dose of CNO was empirically chosen to accommodate the low transfer efficiency of these probes (5–10% for CMA7 probes) and ensuring enough CNO crossed into the interstitial space to activate the vHC terminals. An aliquot (15 μL) of each sample was immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80° C until analysis of glutamate in the perfusate using HPLC with fluorescence detection (Griffin et al., 2014; Griffin et al., 2015).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was conducted in SPSS Version 25. Dependent variables were analyzed by factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures as necessary. For post-hoc analyses, multiple comparisons used Sidak’s test. Student’s t-test was used for between groups comparison. For all analyses, p<0.05 was used as the criteria for significance.

RESULTS

Reducing vHC activity increases drinking in non-dependent mice.

Figure 1 summarizes the results of systemically activating hM4Di in the vHC in dependent and non-dependent mice while drinking alcohol. The design of the experiment was similar to previous publications and is shown in Panel A.

Alcohol Drinking Prior to CNO Challenge.

Mice underwent 3 cycles of CIE exposure prior to challenge with CNO and these data are summarized in Figure 1B. As expected from previous work (Becker & Lopez, 2004; Griffin et al., 2014; Griffin et al., 2021; Haun et al., 2018; Lopez & Becker, 2005), the alcohol dependent (CIE) mice increased alcohol intake significantly over time compared to the relatively stable drinking the CTL group. Further, there was no effect of virus type (mCherry vs hM4Di) on alcohol drinking in either group. This assessment was supported by 3-way ANOVA (2 Groups) X (2 Viruses) X (4 Time points) with Time used as a repeated measure. The 3-way interaction was not-significant [F (3,102) =0.92] and neither was the Time X Virus interaction [F (3,102) =1.249]. However, the Group X Time interaction was significant [F (3,102) =6.370, p = 0.001]. Post-hoc analysis of these data show that the CIE mice consumed more alcohol in the Test drinking weeks compared to the CTL group at the same time point (*p<0.05), as well as their own baseline (^p<0.05).

CNO Challenge.

During Test week 4, mice were challenged with CNO in a cross over design on Tuesday and Thursday of that week to activate the inhibitory DREADD, hM4Di, expressed in vHC glutamatergic neurons. These data are summarized in Figure 1C and are consistent with the data in Figure 1B showing that CIE mice consume more alcohol than CTL mice. Further, the data show that CNO activation of hM4Di DREADDs in the vHC increased alcohol consumption in non-dependent mice. Initially, these data were analyzed using a 3-way ANOVA (2 Groups) X (2 Viruses) X (2 Dose: VEH vs CNO) where Dose was a repeated measure. The 3-way interaction was not significant [F (1,34) =1.660] and neither was the Dose X Group interaction [F (1,340 =0.008]. However, the ANOVA revealed a significant interaction of Virus X Dose [F (1,34) =8.883, p =0.005] indicating that the virus type interacted with CNO challenge.

Additional analyses focused separately on the two different viral groups using a 2-way ANOVA (Group vs Dose), again using Dose as a repeated measure. For the mice expressing only mCherry in the ventral hippocampus, there was no significant interaction [F (1,16) =0.925], nor was there a main effect of Dose [F (1,16) =2.104]. There was, however, a main effect of Group [F (1,16) =11.916, p=0.003], consistent with the increased alcohol consumption by the CIE mice (*p<0.05). Planned comparisons using Sidak’s Post-hoc Test supported the ANOVA indicating significant differences in alcohol consumption between CIE and CTL mice (VEH and CNO conditions both *p<0.05) but did not indicate any other significant differences. The slight decrease in alcohol intake after CNO challenge in the CTL mice was not significant (p=0.09). Thus, CNO did not alter alcohol consumption in CIE and CTL mice expressing the mCherry control virus.

Similar analyses were conducted on the alcohol consumption data from mice expressing hM4Di in the vHC. This analysis did not reveal a significant factor interaction [F (1,18) =0.743] but did indicate significant main effects of Group [F (1,18) =5.996, p =0.025] and Dose [F (1,18) =7.776, p =0.012]. Planned comparisons using Sidak’s Post-hoc Test supported the findings for group differences, but only for the comparison between the CTL and CIE mice after VEH challenge (*p =0.041). No difference was noted between CTL and CIE mice after CNO challenge (p =0.168). While there was a slight increase in alcohol consumption in CIE mice after CNO challenge, this also was not statistically significant (p =0.094). Thus, these data indicate that CNO activation of hM4Di in the vHC increased drinking in CTL mice to amounts observed in CIE mice but did not significantly affect alcohol intake in the CIE mice.

Water Drinking after CNO Challenge.

Because water was also available during the alcohol access session, water consumption was also tracked during this study on days when mice were challenged with CNO. Earlier reports from our laboratory using lickometer systems indicate that water consumption is very low in this limited access paradigm (Griffin et al., 2009b; Griffin et al., 2007). Consistent with the earlier reports, water intake was very low in this experiment. In fact, many values were zero in this experiment during the sessions water was assessed, though some mice did consume some water. No systematic evidence was found to suggest that CNO administration altered water intake in either the hM4Di or the mCherry groups of mice. Because water intake was sparse, no analyses were conducted on these data.

Histology.

Panel D of the figure shows an example of the extent of mCherry DAB staining, with an overall description included in Panel E. Generally, mCherry staining was extensive, being found in all layers of the vHC. Numerous areas outside the vHC also showed staining because of the many efferents arising from the ventral subiculum and CA1 subregions.

Activation of the vHC to NAc pathway increases cFos expression and releases glutamate in the NAc

Figure 2 summarizes the cFos expression and microdialysis experiments.

Figure 2.

A & B) mCherry and cFos co-staining after saline (A) and 3 mg/kg CNO (B) in the NAc. Images were taken with approximately half of the anterior commissure visible, located in the position shown as “AC.” C) Summary of the cFos labeling data showing the significant increase in cFos labeling after CNO administration in hM3Dq expressing mice (*p<0.05; n=5–6/group). D) Concentrations of extracellular glutamate before and after reverse perfusion of CNO through the microdialysis probe. A higher, but non-significant, baseline concentration was noted in the CIE mice but the robust increase in glutamate concentration after CNO was not different between the two groups (*p<0.05; n=3–5/group). All data are means ± S.E.M.

cFos Expression.

As can be seen in the example images shown in Figure 2A and 2B, in mice unilaterally expressing hM3Dq, administration of 3 mg/kg CNO (ip.) robustly increased cFos expression in the NAc. Student’s t-test confirmed the significant increase in overall cFos counts in these mice (Figure 2C; t =16.716, df =9, p<0.0001). Overall, these data are consistent with the expectation that increasing activity of an excitatory pathway increases cFos expression.

Glutamate Microdialysis.

After reverse perfusion of 300 μM CNO, glutamate increased considerably in the post-perfusion samples collected from CTL and CIE mice (Figure 2D). Baseline concentrations were averaged for each mouse and compared against the peak glutamate concentration after the reverse perfusion of CNO was completed. These data were analyzed using a 2 (Group) X 2 (Time) ANOVA where Time was a within-subject factor. The analysis confirmed the significant increase in glutamate response when hM3Dq was activated by CNO as shown by a significant effect of Time (F (1,6) =8.816, p =0.25), though neither Group nor the factor interaction were significant (both F’s<1). Our previous work indicated that CIE mice have higher extracellular glutamate concentrations under baseline conditions, an effect that can be seen in these data, though it did not reach statistical significance. The increase in glutamate with activation of hM3Dq was expected based on many years of electrophysiological validation experiments (MacAskill et al., 2012; Scudder et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2017), and to our knowledge, these are the first data showing pathway specific increases in glutamate in vivo after DREADD activation.

Activation of vHC terminals in the NAc reduces drinking in alcohol dependent mice.

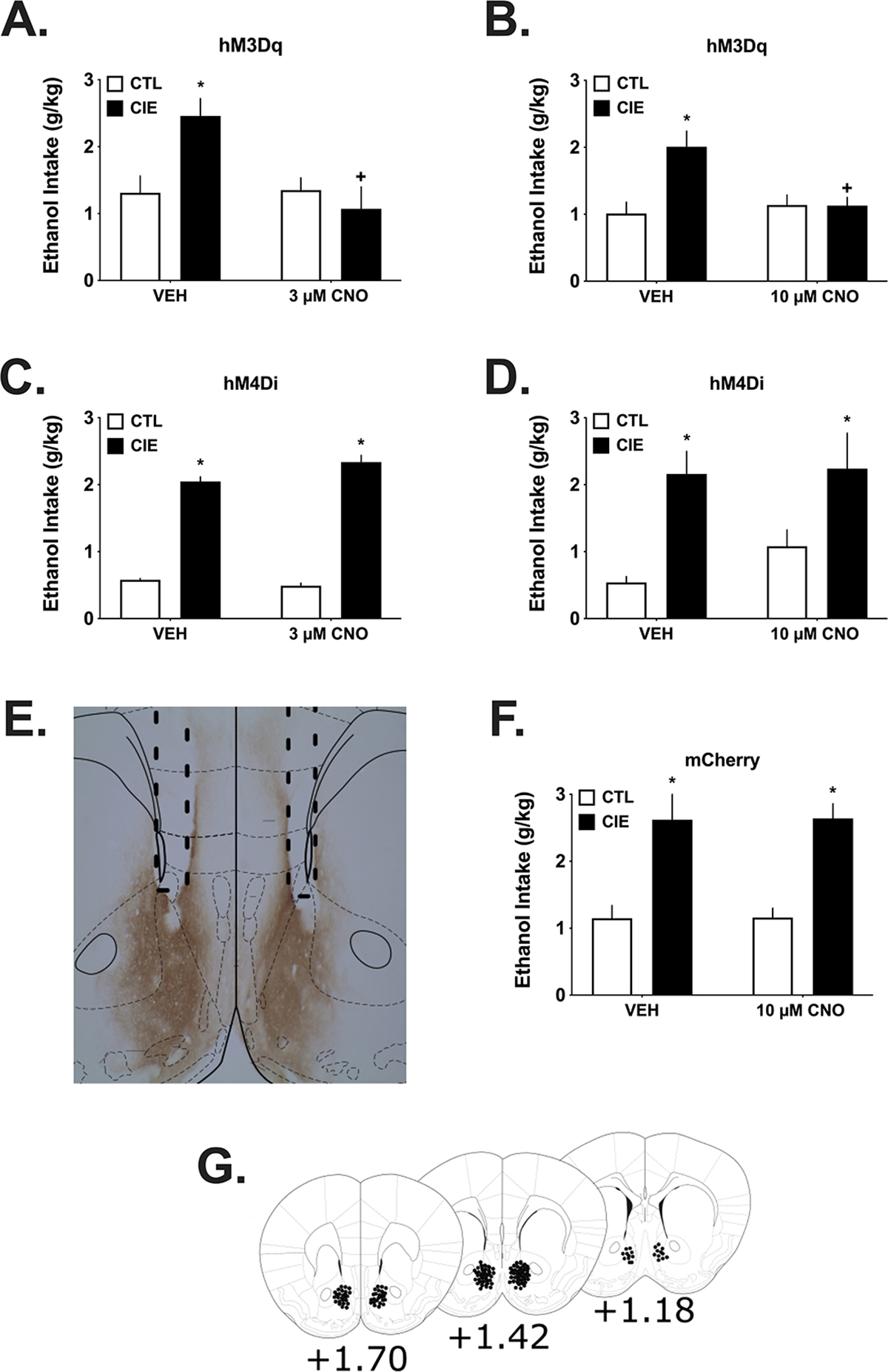

This experiment used several different cohorts of mice expressing either excitatory (hM3Dq) or inhibitory (hM4Di) DREADDs as well as another group of mice expressing only the mCherry tag. The data are summarized in Figure 3. The overall design of these studies was the same as described for the first experiment, except that the studies included a 5th Test week to allow more opportunities for microinjections (see methods).

Figure 3.

These experiments used microinjection procedures to site-specifically deliver CNO or VEH into the NAc of CIE and CTL mice expressing either hM3Dq, hM4Di or mCherry prior to alcohol access. Separate groups were used for each dose of CNO. A & B) In hM3Dq expressing CIE mice, alcohol drinking was reduced by microinjection of both doses of CNO, with no effects on drinking in the CTL mice. As can be seen, CIE mice consumed more alcohol after vehicle (*p<0.05) and their drinking was significantly reduced after intra-NAc CNO compared to vehicle microinjection (+p<0.05; n=5–12/group). C & D) In hM4Di expressing CIE and CTL mice, alcohol drinking was not affected by either CNO dose given directly into the NAc, although a non-significant increase was evident after CNO challenge in CTL mice. CIE mice consumed more alcohol after vehicle and CNO microinjections (*p<0.05; n=4–12/group). E) mCherry staining in the NAc and nearby areas using DAB procedures. Dotted lines show the guide tracts above the NAc. F) Alcohol drinking was not affected by microinjection of the highest CNO dose in mCherry expressing CIE or CTL mice, used as a viral vector control for the groups in the upper panels. As for the other groups used in these experiments, CIE mice consumed more alcohol compared to CTL mice (*p<0.05; n=6–8/group). G) Placements of injector tips extending 0.5 mm below the bottom of the guide. All data are means ± S.E.M.

Activation of the vHC to NAc pathway using intra-NAc CNO.

This experiment examined the possibility that selectively increasing glutamate release from vHC projections in the NAc would alter alcohol drinking. As seen in Figure 3A and 3B, there was a large difference in drinking between the CTL and CIE groups after vehicle microinjection, with the CIE mice by drinking considerably more under these conditions as expected. Microinjection of both the 3 and 10 μM doses of CNO reduced drinking in the CIE groups to intake levels consistent with the CTL mice. These data were analyzed separately by dose.

For the mice microinjected with 3 μM CNO, the 2 (Group) X 2 (Drug) ANOVA found a significant factor interaction (F (1,27) =4.67, p =0.040). However, the Group factor was not significant (F(1,27) =3.275, p =0.081) nor was Drug F(1,27) =1.64, p =0.214. Post-hoc analysis of these data showed that CIE mice were drinking more under Vehicle conditions (p =0.005) than the CTL mice and that 3 μM CNO significantly reduced drinking in the CIE mice compared to vehicle (p =0.001 within group).

In the cohort of mice challenged with 10 μM CNO, there was again a significant factor interaction (F (1,31) =7.25, p =0.011) though the Group factor (F(1,31) =3.948, p =0.096) and Drug factor (F(1,31) = 5.23, p = 0.029) not being significant. Similar to the analyses above, post-hoc analysis of these data showed that CIE mice were drinking more under Vehicle conditions (p = 0.002) than the CTL mice and that 10 μM CNO significantly reduced drinking in the CIE mice compared to vehicle (p = 0.019 within group).

Inhibition of the vHC to NAc pathway using intra-NAc CNO.

These cohorts of mice were used to examine the possibility that inhibiting glutamate release by the vHC to NAc pathway alters drinking. Again, the CIE procedures significantly increased drinking by the CIE mice after vehicle microinjections, as can be seen in Figures 3C and 3D. However, microinjection of either the 3 μM or the 10 μM doses of CNO did not affect drinking. There appears to be a trend for CTL mice to drink more after administration of the 10 μM CNO dose but this was not significant according to a planned comparison (p>0.05).

With the groups of hM4Di mice, separate analyses for the 3 and 10 μM data only revealed significant effects of Group, consistent with the greater drinking by CIE mice under both vehicle and CNO conditions. For the 3 μM cohort, the 2(Group) X 2(Dose) ANOVA found that Group was significant (F (1,37) =53.65, p<0.0001) but there was no effect of Drug or a factor interaction (both F<1). Similarly for the 10 μM cohort analysis, Group was significant (Group F (1,17) =21.392, p<0.0001) but not (Drug F (1,17) =1.056, p = 0.319) or the interaction (F (1,17) <1).

mCherry expression and Intra-NAc CNO.

The cohort of mice expressing only the mCherry tag that was used to visualize expression of the DREADD constructs did not show any effects with the highest dose of intra-NAc CNO (10 μM) used in these studies (Figure 3F). The analysis revealed there was a strong effect of Group (F (1,23) = 28.463, p<0.0001), consistent with the greater amount of drinking by the CIE mice that can be seen in these data. However, neither the Drug factor nor the factor interaction were significant (both F<1). These data support the idea that expression of an active DREADD receptor (e.g. hM3Dq) is required to affect drinking.

Histology.

Figure 3E shows an example of mCherry DAB staining (reddish brown staining) and the dotted lines indicate position of the guide cannula. Figure 3G shows microinjector tip placements (dots).

DISCUSSION

These results show that chemogenetic inhibition of the ventral hippocampus (vHC) increased alcohol drinking in non-dependent (CTL) mice with little change in drinking by the alcohol dependent (CIE) mice. Conversely, chemogenetic activation of the vHC terminals in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) reduced alcohol drinking by the CIE mice, with no effects on drinking in the CTL mice. Further, chemogenetic activation of the vHC terminals in the NAc increased cFos expression and released glutamate, confirming earlier research regarding the glutamatergic nature of these projection neurons. Collectively, these data are consistent with the guiding hypothesis and indicate that the vHC and its glutamatergic pathway to the NAc normally function to keep alcohol consumption at lower levels and this inhibitory function is disrupted by alcohol dependence, permitting greater alcohol intake.

Mice rendered alcohol dependent significantly increase their alcohol drinking compared to non-dependent animals (Becker & Lopez, 2004; Griffin, 2014; Lopez & Becker, 2005). Findings using similar procedures have been reported by other laboratories in mice (DePoy et al., 2013; Dhaher et al., 2008; Finn et al., 2007; Jeanes et al., 2011) and rats (Gilpin et al., 2008; Hansson et al., 2008; O’Dell et al., 2004; Roberts et al., 1996). Increased drinking caused by alcohol dependence is undoubtedly due to adaptations in specific neurobiological systems that regulate alcohol drinking and the present data indicate that the vHC and the vHC to NAc pathway are involved in these adaptations. A variety of studies suggest that increased neuronal activity caused by chronic alcohol exposure may drive increased drinking (Griffin et al., 2014; Griffin et al., 2015; Kircher et al., 2019; Marty & Spigelman, 2012; Padula et al., 2015). However, as the present data indicate, reduced neuronal function in some brain regions is another possibility that may contribute to higher levels of alcohol intake. Similarly, it was reported that reduced activity of the infralimbic projections to the NAc was associated with increased drinking (Pfarr et al., 2015) and another study reported similar findings in the context of sucrose consumption (Barker et al., 2017).

Therefore, the vHC appears to exert an inhibitory influence on alcohol drinking behavior which is attenuated by the development of alcohol dependence. Previous literature proposed that the hippocampus is part of a behavioral inhibition circuit in the brain that keeps certain behaviors in check (McNaughton, 2006; Schwarting & Busse, 2017). Other recent work has explored this concept by modeling approach-avoidance behaviors in rodents. In these studies, data indicate that inhibition of vHC circuitry increases approach behaviors to contexts that were previously avoided (Ito & Lee, 2016; Schumacher et al., 2016). Relevant to the present study are earlier data indicating an inhibitory role of the hippocampus on consummatory behavior (Bannerman et al., 2002b). Further, it has been reported that chemogenetic inhibition of the vHC, after finishing a meal, increases feeding when rats are presented their next meal (Hannapel et al., 2019; Hannapel et al., 2017). Thus, the findings in this report extend earlier work to include excessive alcohol drinking.

The current data show that activating vHC terminals within the NAc reduces drinking by alcohol dependent mice requires a note of caution for future in vivo experiments. The subiculum of the vHC is a seizure prone region (de Guzman et al., 2006; Levesque & Avoli, 2021). Bilaterally expressing excitatory DREADD receptors (hM3Dq) in the vHC and activating them using systemically administered CNO can produce seizure activity in mice (W. Griffin, unpublished observations). Hence, the use of either unilateral expression or targeted administration of CNO (microinjections) when hM3Dq was expressed in the vHC in the present studies. Limiting CNO exposure to the NAc only using microinjection procedures did not produce any seizure activity. Importantly, the CIE and CTL mice continued to drink alcohol, though as reported, drinking in the CIE mice was reduced to levels of the CTL mice.

Consistent with a variety of earlier publications (Britt et al., 2012; Christie et al., 1987; MacAskill et al., 2012; Scudder et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2017), the cFos and microdialysis results presented here show that the vHC-NAc pathway is excitatory and releases glutamate when activated. Although the strong increase in cFos expression was found after systemic CNO administration raising the possibility of that perhaps collateral pathways could be involved, the microdialysis data shown here was collected following a local challenge with reverse perfusion of CNO and showed a large increase in extracellular glutamate specific to the vHC-NAc pathway. While it was noted that the dependent mice had a slightly higher basal concentration of NAc glutamate in the dependent mice in keeping with previous findings (Griffin et al., 2014; Griffin et al., 2015), there was no clear difference between the groups in terms of CNO-evoked glutamate release in this small study. Because other reports have noted that presynaptic glutamate release from the vHC-NAc pathway is increased by CIE (Jeanes et al., 2011; Jeanes et al., 2014; Kircher et al., 2019), this suggests the need for further experiments with different concentrations of CNO to distinguish the two groups or, perhaps, that microdialysis is a less sensitive measure of CNO-evoked glutamate release than electrophysiologic measurements.

Previous work has shown that there are CIE-induced reductions in mGluR2 receptor expression in the NAc (Griffin et al., 2021) as well as down-regulated GLT-1 expression (Griffin et al., 2021). mGluR2 and GLT-1 are important proteins in glutamatergic signaling. Intriguingly, previous electrophysiological experiments in the NAc following voluntary alcohol drinking and CIE exposure indicates that the AMPA/NMDA ratio and long-term depression (LTD) are reduced in the NAc (Jeanes et al., 2011; Jeanes et al., 2014; Kircher et al., 2019) and, further, this same research group found abrogated LTD and increased Ca-permeable AMPA receptor expression specifically in the vHC-D1 medium spiny neuron (MSN) synapses in the NAc (Kircher et al., 2019). In addition to the direct connections of vHC projections with D1 MSNs in the NAc, there are also direct connections with parvalbumin-expressing neurons (Meredith & Wouterlood, 1990) that were originally discovered to participate in feed-forward inhibition of synaptic signaling in the NAc (Pennartz & Kitai, 1991). More recent work has identified that this feed-forward inhibitory circuit within the nucleus accumbens is important to a variety of behaviors (Pisansky et al., 2019; Scudder et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2017). Because activation of the vHC terminals in the NAc of CIE mice reduced drinking (but not in the CTL mice), this suggests that the feed-forward inhibitory circuit maybe compromised by alcohol dependence and is a possible mechanism to examine in future studies.

Chemogenetic inhibition of vHC activity did not significantly increase alcohol drinking in the CIE mice. It is possible that the lack of a further increase in drinking by the CIE mice could simply be attributed to a ceiling effect related to time and/or volume constraints of the limited access procedure. B6 mice can more than double their alcohol intake from ~2 g/kg to ~4.5 g/kg within 2-hours while drinking 20% alcohol (v/v) and administered the kappa receptor agonist U50488 (Haun et al., 2020). Given that the current experiments used 15% alcohol (v/v), it is possible that time and/or volume limited the alcohol intake in this study. Alternatively, there could be a simple limit to the contribution of the vHC in terms of regulating the amount of alcohol consumed. This alternative idea is supported by the observation that the opposite manipulation, chemogenetic activation, did not influence drinking in the CTL mice. Nevertheless, additional experiments are necessary to determine if chemogenetic inhibition of the ventral hippocampus in CIE mice can increase drinking even further.

In the current study, water intake was measured and there was no systematic evidence that chemogenetic inhibition of the vHC changed water consumption. Still, given the generally low water intake overall (see results), it is premature to suggest that the effect of vHC inhibition is specific to alcohol while natural reinforcers like food and sucrose are unaffected. In fact, some reports indicate the involvement of the vHC in negatively regulating feeding behavior (Briggs et al., 2021; Ferbinteanu & McDonald, 2001; Hannapel et al., 2019; Hannapel et al., 2017), findings broadly consistent with the present findings. On the other hand, a recent paper showed that optogenetically activating the vHC to NAc pathway could condition a flavor preference to a sucrose solution (Yang et al., 2020), underscoring the complexity of vHC function and, in light of the data presented here, indicating that there are potential differences in the role of vHC in drinking natural reinforcers versus alcohol. While some of these previous findings might suggest a lack of selectivity towards alcohol, it worth noting that activating the excitatory pathway only reduced drinking in alcohol dependent mice and not the CTL mice. Thus, the development of alcohol dependence appears to confer some selectivity on the function of the vHC-NAc pathway towards alcohol drinking.

An important future extension of the current work will be to examine the function of the vHC and the vHC-NAc pathway in females in the context of alcohol dependence, as only males were used in the present study. It has been previously reported that sex influences alcohol intake; however, there is a similar increase in alcohol drinking following CIE procedures (Huitron-Resendiz et al., 2018; Lopez et al., 2020). Some evidence suggests that while male and female rats respond in broadly similar ways to chronic alcohol, the mechanisms underlying those responses may be different. It has been shown that, in general, the vHC region in male and female rats is more responsive to chronic alcohol than the dorsal hippocampus and, further, that males and females show a negative affective response to alcohol withdrawal (Almonte et al., 2017; Bach et al., 2021b; Ewin et al., 2019). However, using electrophysiological procedures, male CIE rats show increased synaptic excitability (Almonte et al., 2017; Ewin et al., 2019), likely related to alterations in synaptic inputs from the amygadala (Bach et al., 2021a), while female CIE rats show a decreased synaptic excitability (Bach et al., 2021b). Coupled with sex differences in the expression and function of the glutamatergic system [Reviewed: (Giacometti & Barker, 2020)], there are important reasons to examine the role of sex in future studies.

The inhibitory role of the vHC and the vHC-NAc pathway in alcohol drinking may broadly relate to the development of tolerance in alcohol dependence. For example, repeated exposure to alcohol renders subjects tolerant to the aversive properties of alcohol (Lopez et al., 2012; May et al., 2015). Because other reports indicate the vHC is involved in processing aversion (Ito & Lee, 2016; Kjelstrup et al., 2002; Maren & Holt, 2004; Schumacher et al., 2016), this raises the possibility that alcohol dependence-induced adaptations within the vHC and vHC-NAc pathway reduce the aversive qualities of alcohol, permitting greater alcohol intake. Alternatively, because there is evidence of the involvement of the vHC in feeding behaviors (Briggs et al., 2021; Hannapel et al., 2019; Hannapel et al., 2017), it is possible that the negative valence of alcohol’s effects (i.e. aversion) is irrelevant and the vHC and vHC-NAc pathway simply process interoceptive cues regarding the state of intoxication. Alcohol dependence also produces tolerance to the interoceptive cues of alcohol, requiring higher doses for subjects to respond appropriately in classical discrimination procedures (Becker & Baros, 2006; Crissman et al., 2004). In this case, alcohol-dependent blunting of intoxication signals may also allow higher intake to occur. To the extent that either interoceptive cues or aversive effects influence the amount of alcohol consumed, tolerance to these effects may permit higher alcohol intake in the CIE mice. More experiments are needed to understand the role of the vHC and vHC-NAc pathway in tolerance to alcohol and the impact on alcohol drinking.

In conclusion, reduced function of the vHC permits more alcohol drinking by non-dependent (CTL) mice. On the other hand, activating the glutamatergic terminals in the NAc arising from the vHC, reduced the high drinking in the alcohol dependent (CIE) mice. Much of the work in earlier reports demonstrating a supporting role for the hippocampus in various behaviors relied on permanent or reversible lesions. Emerging work, using more selective approaches, is revealing the complex function of this heterogenous structure as well as its interactions with other brain areas and its involvement in alcohol use disorder.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Using inhibitory DREADDs, reducing activity of the ventral hippocampus (vHC) significantly increases drinking in non-dependent mice to the level of intake achieved by alcohol dependent mice in the CIE model.

Using excitatory DREADDs, increasing activity of the vHC to nucleus accumbens (NAc) pathway, increases cFos expression and glutamate release in the NAc.

DREADD-induced activation of the vHC terminals in the NAc in dependent mice reduced ethanol drinking to similar levels as the non-dependent mice.

These data indicate that the vHC and the glutamatergic vHC-NAc pathway are involved in negatively regulating alcohol drinking.

Acknowledgements:

Superb technical assistance was provided by Laura Ralston, Sarah K. Brown, Sarah Reasons, Suzanna Donato, Alexa Lane, Reilly Kilpatrick. Funding provided by R21AA024881 (WCG), P50AA010761 (WCG, HCB, MFL, JJW), UO1AA014095 (HCB), U24AA020929 (HCB) & VA Medical Research (HCB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Agartz I, Momenan R, Rawlings RR, Kerich MJ, & Hommer DW (1999). Hippocampal volume in patients with alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almonte AG, Ewin SE, Mauterer MI, Morgan JW, Carter ES, & Weiner JL (2017). Enhanced ventral hippocampal synaptic transmission and impaired synaptic plasticity in a rodent model of alcohol addiction vulnerability. Sci Rep 7: 12300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylward RL, & Totterdell S (1993). Neurons in the ventral subiculum, amygdala and entorhinal cortex which project to the nucleus accumbens: their input from somatostatin-immunoreactive boutons. J Chem Neuroanat 6: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EC, Ewin SE, Baldassaro AD, Carlson HN, & Weiner JL (2021a). Chronic intermittent ethanol promotes ventral subiculum hyperexcitability via increases in extrinsic basolateral amygdala input and local network activity. Sci Rep 11: 8749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach EC, Morgan JW, Ewin SE, Barth SH, Raab-Graham KF, & Weiner JL (2021b). Chronic Ethanol Exposures Leads to a Negative Affective State in Female Rats That Is Accompanied by a Paradoxical Decrease in Ventral Hippocampus Excitability. Frontiers in neuroscience 15: 669075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KL, Sayles H, Campbell J, Khalid N, Anglim M, Ponce J, et al. (2022). COVID-19 patients with documented alcohol use disorder or alcohol-related complications are more likely to be hospitalized and have higher all-cause mortality. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 46: 1023–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Deacon RM, Offen S, Friswell J, Grubb M, & Rawlins JN (2002a). Double dissociation of function within the hippocampus: spatial memory and hyponeophagia. Behavioral neuroscience 116: 884–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Lemaire M, Yee BK, Iversen SD, Oswald CJ, Good MA, et al. (2002b). Selective cytotoxic lesions of the retrohippocampal region produce a mild deficit in social recognition memory. Experimental brain research 142: 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Rawlins JN, McHugh SB, Deacon RM, Yee BK, Bast T, et al. (2004). Regional dissociations within the hippocampus--memory and anxiety. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 28: 273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa C, Cowell AJ, & Dowd WN (2021). Alcohol Consumption in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. J Addict Med 15: 341–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JM, Bryant KG, & Chandler LJ (2019). Inactivation of ventral hippocampus projections promotes sensitivity to changes in contingency. Learn Mem 26: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JM, Glen WB, Linsenbardt DN, Lapish CC, & Chandler LJ (2017). Habitual Behavior Is Mediated by a Shift in Response-Outcome Encoding by Infralimbic Cortex. eNeuro 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JM, Lench DH, & Chandler LJ (2016). Reversal of alcohol dependence-induced deficits in cue-guided behavior via mGluR2/3 signaling in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233: 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, & Baros AM (2006). Effect of duration and pattern of chronic ethanol exposure on tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in C57BL/6J mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 319: 871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, & Lopez MF (2004). Increased ethanol drinking after repeated chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal experience in C57BL/6 mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28: 1829–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beresford TP, Arciniegas DB, Alfers J, Clapp L, Martin B, Beresford HF, et al. (2006). Hypercortisolism in alcohol dependence and its relation to hippocampal volume loss. J Stud Alcohol 67: 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert JM, Adhikary S, St Laurent R, Marchant NJ, Wang HL, Morales M, et al. (2016). Role of projections from ventral subiculum to nucleus accumbens shell in context-induced reinstatement of heroin seeking in rats. Psychopharm 233: 1991–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs SB, Hannapel R, Ramesh J, & Parent MB (2021). Inhibiting ventral hippocampal NMDA receptors and Arc increases energy intake in male rats. Learn Mem 28: 187–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt JP, Benaliouad F, McDevitt RA, Stuber GD, Wise RA, & Bonci A (2012). Synaptic and behavioral profile of multiple glutamatergic inputs to the nucleus accumbens. Neuron 76: 790–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KG, & Barker JM (2020). Arbitration of Approach-Avoidance Conflict by Ventral Hippocampus. Frontiers in neuroscience 14: 615337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho AF, Heilig M, Perez A, Probst C, & Rehm J (2019). Alcohol use disorders. Lancet 394: 781–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, Summers RJ, Stephenson JA, Cook CJ, & Beart PM (1987). Excitatory amino acid projections to the nucleus accumbens septi in the rat: a retrograde transport study utilizing D[3H]aspartate and [3H]GABA. Neuroscience 22: 425–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crissman AM, Studders SL, & Becker HC (2004). Tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol following chronic inhalation exposure to ethanol in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Pharmacol 15: 569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Guzman P, Inaba Y, Biagini G, Baldelli E, Mollinari C, Merlo D, et al. (2006). Subiculum network excitability is increased in a rodent model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus 16: 843–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePoy L, Daut R, Brigman JL, MacPherson K, Crowley N, Gunduz-Cinar O, et al. (2013). Chronic alcohol produces neuroadaptations to prime dorsal striatal learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 14783–14788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaher R, Finn D, Snelling C, & Hitzemann R (2008). Lesions of the extended amygdala in C57BL/6J mice do not block the intermittent ethanol vapor-induced increase in ethanol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvig SK, McGinn MA, Smith C, Arends MA, Koob GF, & Vendruscolo LF (2021). Tolerance to alcohol: A critical yet understudied factor in alcohol addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 204: 173155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewin SE, Morgan JW, Niere F, McMullen NP, Barth SH, Almonte AG, et al. (2019). Chronic Intermittent Ethanol Exposure Selectively Increases Synaptic Excitability in the Ventral Domain of the Rat Hippocampus. Neuroscience 398: 144–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS, & Dong HW (2010). Are the dorsal and ventral hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron 65: 7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferbinteanu J, & McDonald RJ (2001). Dorsal/ventral hippocampus, fornix, and conditioned place preference. Hippocampus 11: 187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn DA, Snelling C, Fretwell AM, Tanchuck MA, Underwood L, Cole M, et al. (2007). Increased Drinking During Withdrawal From Intermittent Ethanol Exposure Is Blocked by the CRF Receptor Antagonist d-Phe-CRF(12–41). Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 939–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, & Paxinos G (2008) The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, Third Edition. 3rd edn. Academic Press: San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Giacometti LL, & Barker JM (2020). Sex differences in the glutamate system: Implications for addiction. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 113: 157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin NW, Richardson HN, Lumeng L, & Koob GF (2008). Dependence-induced alcohol drinking by alcohol-preferring (P) rats and outbred Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 1688–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC 3rd (2014). Alcohol dependence and free-choice drinking in mice. Alcohol 48: 287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC 3rd, Haun HL, Hazelbaker CL, Ramachandra VS, & Becker HC (2014). Increased extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens promotes excessive ethanol drinking in ethanol dependent mice. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 39: 707–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC 3rd, Lopez MF, & Becker HC (2009a). Intensity and duration of chronic ethanol exposure is critical for subsequent escalation of voluntary ethanol drinking in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33: 1893–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC 3rd, & Middaugh LD (2006). The influence of sex on extracellular dopamine and locomotor activity in C57BL/6J mice before and after acute cocaine challenge. Synapse 59: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC 3rd, Ramachandra VS, Knackstedt LA, & Becker HC (2015). Repeated Cycles of Chronic Intermittent Ethanol Exposure Disrupt Glutamate Homeostasis in Mice. Front Pharmacol 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC, Haun HL, Ramachandra VS, Knackstedt LA, Mulholland PJ, & Becker HC (2021). Effects of ceftriaxone on ethanol drinking and GLT-1 expression in ethanol dependence and relapse drinking. Alcohol 92: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC, Lopez MF, Yanke AB, Middaugh LD, & Becker HC (2009b). Repeated cycles of chronic intermittent ethanol exposure in mice increases voluntary ethanol drinking and ethanol concentrations in the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology 201: 569–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC, Middaugh LD, & Becker HC (2007). Voluntary ethanol drinking in mice and ethanol concentrations in the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res 1138: 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Vermeulen-Van der Zee E, te Kortschot A, & Witter MP (1987). Organization of the projections from the subiculum to the ventral striatum in the rat. A study using anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. Neuroscience 23: 103–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannapel R, Ramesh J, Ross A, LaLumiere RT, Roseberry AG, & Parent MB (2019). Postmeal Optogenetic Inhibition of Dorsal or Ventral Hippocampal Pyramidal Neurons Increases Future Intake. eNeuro 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannapel RC, Henderson YH, Nalloor R, Vazdarjanova A, & Parent MB (2017). Ventral hippocampal neurons inhibit postprandial energy intake. Hippocampus 27: 274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson AC, Rimondini R, Neznanova O, Sommer WH, & Heilig M (2008). Neuroplasticity in brain reward circuitry following a history of ethanol dependence. The European journal of neuroscience 27: 1912–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haun HL, Griffin WC, Lopez MF, & Becker HC (2020). Kappa opioid receptors in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis regulate binge-like alcohol consumption in male and female mice. Neuropharmacology 167: 107984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haun HL, Griffin WC, Lopez MF, Solomon MG, Mulholland PJ, Woodward JJ, et al. (2018). Increasing Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in medial prefrontal cortex selectively reduces excessive drinking in ethanol dependent mice. Neuropharmacology 140: 35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huitron-Resendiz S, Nadav T, Krause S, Cates-Gatto C, Polis I, & Roberts AJ (2018). Effects of Withdrawal from Chronic Intermittent Ethanol Exposure on Sleep Characteristics of Female and Male Mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42: 540–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, & Lee AC (2016). The role of the hippocampus in approach-avoidance conflict decision-making: Evidence from rodent and human studies. Behav Brain Res 313: 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanes ZM, Buske TR, & Morrisett RA (2011). In vivo chronic intermittent ethanol exposure reverses the polarity of synaptic plasticity in the nucleus accumbens shell. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 336: 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanes ZM, Buske TR, & Morrisett RA (2014). Cell type-specific synaptic encoding of ethanol exposure in the nucleus accumbens shell. Neurosci 277: 184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoski SE, & Grill HJ (2015). Hippocampus Contributions to Food Intake Control: Mnemonic, Neuroanatomical, and Endocrine Mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, & Domesick VB (1982). The distribution of the projection from the hippocampal formation to the nucleus accumbens in the rat: an anterograde- and retrograde-horseradish peroxidase study. Neuroscience 7: 2321–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher DM, Aziz HC, Mangieri RA, & Morrisett RA (2019). Ethanol Experience Enhances Glutamatergic Ventral Hippocampal Inputs to D1 Receptor-Expressing Medium Spiny Neurons in the Nucleus Accumbens Shell. J Neurosci 39: 2459–2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjelstrup KG, Tuvnes FA, Steffenach HA, Murison R, Moser EI, & Moser MB (2002). Reduced fear expression after lesions of the ventral hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99: 10825–10830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, & Volkow ND (2016). Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3: 760–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasseter HC, Xie X, Ramirez DR, & Fuchs RA (2010). Sub-region specific contribution of the ventral hippocampus to drug context-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuroscience 171: 830–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGates TA, Kvarta MD, Tooley JR, Francis TC, Lobo MK, Creed MC, et al. (2018). Reward behaviour is regulated by the strength of hippocampus-nucleus accumbens synapses. Nature 564: 258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque M, & Avoli M (2021). The subiculum and its role in focal epileptic disorders. Rev Neurosci 32: 249–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, & Becker HC (2005). Effect of pattern and number of chronic ethanol exposures on subsequent voluntary ethanol intake in C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology 181: 688–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, Griffin WC 3rd, Melendez RI, & Becker HC (2012). Repeated cycles of chronic intermittent ethanol exposure leads to the development of tolerance to aversive effects of ethanol in C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36: 1180–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, Reasons SE, Carper BA, Nolen TL, Williams RL, & Becker HC (2020). Evaluation of the effect of doxasozin and zonisamide on voluntary ethanol intake in mice that experienced chronic intermittent ethanol exposure and stress. Alcohol 89: 37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAskill AF, Little JP, Cassel JM, & Carter AG (2012). Subcellular connectivity underlies pathway-specific signaling in the nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci 15: 1624–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant NJ, Campbell EJ, Whitaker LR, Harvey BK, Kaganovsky K, Adhikary S, et al. (2016). Role of Ventral Subiculum in Context-Induced Relapse to Alcohol Seeking after Punishment-Imposed Abstinence. J Neurosci 36: 3281–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, & Holt WG (2004). Hippocampus and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats: muscimol infusions into the ventral, but not dorsal, hippocampus impair the acquisition of conditional freezing to an auditory conditional stimulus. Behavioral neuroscience 118: 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty VN, & Spigelman I (2012). Long-lasting alterations in membrane properties, k(+) currents, and glutamatergic synaptic currents of nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons in a rat model of alcohol dependence. Frontiers in neuroscience 6: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May CE, Haun HL, & Griffin WC 3rd (2015). Sensitization and Tolerance Following Repeated Exposure to Caffeine and Alcohol in Mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39: 1443–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton N (2006). The role of the subiculum within the behavioural inhibition system. Behav Brain Res 174: 232–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, & Wouterlood FG (1990). Hippocampal and midline thalamic fibers and terminals in relation to the choline acetyltransferase-immunoreactive neurons in nucleus accumbens of the rat: a light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol 296: 204–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel BJ, Schweinsburg AD, Phan V, & Tapert SF (2005). Reduced hippocampal volume among adolescents with alcohol use disorders without psychiatric comorbidity. Psychiatry Res 139: 181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell LE, Roberts AJ, Smith RT, & Koob GF (2004). Enhanced alcohol self-administration after intermittent versus continuous alcohol vapor exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28: 1676–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padula AE, Griffin WC 3rd, Lopez MF, Nimitvilai S, Cannady R, McGuier NS, et al. (2015). KCNN Genes that Encode Small-Conductance Ca-Activated K Channels Influence Alcohol and Drug Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 40: 1928–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz CM, Ito R, Verschure PF, Battaglia FP, & Robbins TW (2011). The hippocampal-striatal axis in learning, prediction and goal-directed behavior. Trends Neurosci 34: 548–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz CM, & Kitai ST (1991). Hippocampal inputs to identified neurons in an in vitro slice preparation of the rat nucleus accumbens: evidence for feed-forward inhibition. J Neurosci 11: 2838–2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfarr S, Meinhardt MW, Klee ML, Hansson AC, Vengeliene V, Schonig K, et al. (2015). Losing Control: Excessive Alcohol Seeking after Selective Inactivation of Cue-Responsive Neurons in the Infralimbic Cortex. J Neurosci 35: 10750–10761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson OT, & Griffiths AC (1985). The topographic order of inputs to nucleus accumbens in the rat. Neurosci 16: 275–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisansky MT, Lefevre EM, Retzlaff CL, Trieu BH, Leipold DW, & Rothwell PE (2019). Nucleus Accumbens Fast-Spiking Interneurons Constrain Impulsive Action. Biol Psychiatry 86: 836–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Dawson D, Frick U, Gmel G, Roerecke M, Shield KD, et al. (2014). Burden of disease associated with alcohol use disorders in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 1068–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Gmel GE, Gmel G, Hasan OSM, Imtiaz S, Popova S, et al. (2017). The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease-an update. Addiction 112: 968–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Cole M, & Koob GF (1996). Intra-amygdala muscimol decreases operant ethanol self-administration in dependent rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 20: 1289–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JL, & See RE (2007). Selective inactivation of the ventral hippocampus attenuates cue-induced and cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking in rats. Neurobiology of learning and memory 87: 688–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher A, Vlassov E, & Ito R (2016). The ventral hippocampus, but not the dorsal hippocampus is critical for learned approach-avoidance decision making. Hippocampus 26: 530–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarting RK, & Busse S (2017). Behavioral facilitation after hippocampal lesion: A review. Behav Brain Res 317: 401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudder SL, Baimel C, Macdonald EE, & Carter AG (2018). Hippocampal-Evoked Feedforward Inhibition in the Nucleus Accumbens. J Neurosci 38: 9091–9104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange BA, Witter MP, Lein ES, & Moser EI (2014). Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nat Rev Neurosci 15: 655–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, & Rebec GV (2003). Lidocaine inactivation of ventral subiculum attenuates cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J Neurosci 23: 10258–10264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groen T, & Wyss JM (1990). Extrinsic projections from area CA1 of the rat hippocampus: olfactory, cortical, subcortical, and bilateral hippocampal formation projections. J Comp Neurol 302: 515–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang AK, Mendoza JA, Lafferty CK, Lacroix F, & Britt JP (2020). Hippocampal Input to the Nucleus Accumbens Shell Enhances Food Palatability. Biol Psychiatry 87: 597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Yan Y, Li KL, Wang Y, Huang YH, Urban NN, et al. (2017). Nucleus accumbens feedforward inhibition circuit promotes cocaine self-administration. PNAS 114: E8750–E8759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]