Abstract

Objective

Cognitive dysfunction has been observed consistently in a subset of breast cancer survivors. Yet, the precise physiological and processing origins of dysfunction remain unknown. The current study examined the utility of methods and procedures based on cognitive neuroscience to study cognitive change associated with cancer and cancer treatment.

Methods

We used electroencephalogram and behavioral measures in a longitudinal design to investigate pre- versus post-treatment effects on attention performance in breast cancer patients (n = 15) compared with healthy controls (n = 24), as participants completed the revised Attention Network Test, a cognitive measure of alerting, orienting, and inhibitory control of attention.

Results

We found no group differences in behavioral performance from pretest to posttest, but significant event-related potential effects of cancer treatment in processing cue validity: After treatment, patients revealed decreased N1 amplitude and increased P3 amplitude, suggesting a suppressed early (N1) response and an exaggerated late (P3) response to invalid cues.

Conclusions

The results suggest that treatment-related attentional disruption begins in early sensory/perceptual processing and extends to compensatory top-down executive processes.

Keywords: EEG, Attention, Breast cancer, Longitudinal, Executive functioning

Introduction

Nearly 30 years of research has documented a host of cognitive changes in patients treated for breast cancer (Ahles, Root, & Ryan, 2012; Chen et al., 2017; Kam et al., 2016; Van Dyk et al., 2017; Wefel, Saleeba, Buzdar, & Meyers, 2010). Yet, many lingering questions about these treatment-associated decrements remain, including the value of measures and methods based in cognitive neuroscience as a frontline gage of cognitive decline; the specific time course of cognitive processes affected; and the nature of compensatory processes that are frequently used to explain maintenance of performance despite changes in brain structure and function (Ahles & Root, 2018; Horowitz, Suls, & Treviño, 2018). The current study explored the time course of cognitive function in breast cancer in the context of a longitudinal electrophysiological design using the results to inform the roles of compensatory processes and cognitive neuroscience techniques in understanding cancer-related cognitive impairments.

Cognitive Neuroscience Measures and Methods

Cognitive neuroscience measures assess cognitive function at differing levels of ecological validity and sensitivity than standard neuropsychological measures (see Ganz et al., 2013). Discrepancies between self-reported cognitive change and neuropsychological performance have been puzzling (Balash et al., 2013). For example, cancer survivors commonly report memory problems but typically perform normally on clinical measures of memory (Hermelink et al., 2007; Mihuta, Green, Man, & Shum, 2016; Pullens, De Vries, & Roukema, 2010). The limitations of clinical neuropsychological measures to assess relatively subtle changes in cognitive function associated with cancer and cancer treatments have led some investigators to advocate for the use of assessment strategies based on cognitive neuroscience methods that may be able to identify these subtle differences in performance and can be designed to assess specific cognitive processes (e.g., Horowitz et al., 2018; Park et al., 2021; see Wefel, Kesler, Noll, & Schagen, 2015, for review). Further, neuroscience techniques such as the electroencephalogram (EEG), which provides millisecond-level temporal resolution to measure the earliest phases of information processing, can evaluate cognitive processes outside of conscious awareness. The EEG thus presents an ideal method to reveal how early cognitive subprocesses are affected by disease and treatment. Indeed, increasing evidence suggests that these early processes (e.g., filtering irrelevant stimuli, mismatch processing, etc.) are altered in breast cancer survivors (e.g., Melara, Root, Bibi, & Ahles, 2021). The current study sought to probe subtle changes in these cognitive subprocesses within a longitudinal design.

Cognitive Processes Affected by Cancer Treatment

Data from our laboratory provide evidence that the disruption of attention and early executive processes in cancer survivors interferes with the registration of information into memory (Root, Andreotti, Tsu, Ellmore, & Ahles, 2016; see also Cheng et al., 2013). On this account, survivors’ perceptions are accurate, but their capacity to attend to and learn new information is diminished; thus, the problem involves inefficient storage of information rather than the forgetting of learned information (Gaynor et al., 2021).

Several EEG studies have found evidence for alterations in event-related potentials (ERPs) associated with the timing and/or efficiency of attention and memory systems in breast cancer survivors (Kam et al., 2016; Kreukels et al., 2006, 2008; Kreukels, van Dam, Ridderinkhof, Boogerd, & Schagen, 2008; Swainston, Louis, Moser, & Derakshan, 2021). These studies focus on group differences in the magnitude of an ERP component known as P3, a relatively late electrophysiological gage of the salience and ease of classification of stimuli held in working memory, occurring approximately 300 ms after stimulus onset. For example, Kreukels and colleagues (2008) compared survivors who had undergone different chemotherapy regimens (i.e., FEC, CTC, and CMF) with Stage I breast cancer patients who had not received chemotherapy (control). The P3 amplitude and latency were reduced in each of the chemotherapy groups relative to controls, with no concomitant ERP effect of tamoxifen treatment. Similar results have been found with sustained slow-wave (SW) ERP activity, occurring approximately 1,000 ms after stimulus onset (Wirkner et al., 2017). The results suggest that chemotherapy undermines the speed and distinctiveness of stimulus encoding in attention/working memory.

Melara and colleagues (2021) found recently that disruption of these active attentional processes, represented by P3 and SW, may in fact have an even earlier basis in automatic sensory information processing, represented by the P1 and N1 ERP components, occurring approximately 50 and 100 ms after stimulus onset, respectively. The authors reported that suppression of the P1 component to redundant sensory stimulation, evident in healthy matched controls, was absent in breast cancer survivors, suggesting inefficient gating of sensory input. The results, together with corresponding findings in a mouse model of breast cancer chemotherapy (Gandal, Ehrlichman, Rudnick, & Siegel, 2008), point to an early hippocampally based impairment in sensory filtering resulting from treatment exposure (see also Cheng et al., 2017). The purpose of the current study was to use ERPs to investigate the time course of attentional disruption from breast cancer from early sensory/perceptual processes (P1 and N1) to later active attentional processes (P3 and SW).

Previous Longitudinal Research

Extant ERP studies of breast cancer treatment have employed only cross-sectional designs to probe group differences (Kam et al., 2016; Kreukels et al., 2006, 2008; Melara et al., 2021; Swainston et al., 2021; Wirkner et al., 2017; but see Moore, Parsons, Yue, Rybicki, & Siemionow, 2014), with patients often having received treatment years earlier, leaving uncertain the differential effects of disease and treatment on cognitive subprocesses. However, recent brain imaging studies employing longitudinal designs report pre-treatment baseline differences between patients and controls in both anatomical structure (Chen et al., 2020; Deprez et al., 2012; McDonald, Conroy, Ahles, West, & Saykin, 2010, 2012) and neural functioning (Chen et al., 2022; Ferguson et al., 2007; Kesler et al., 2017; Pergolizzi et al., 2019). Thus, the deficits in cognitive function associated with breast cancer may actually precede systemic cancer treatment, implicating long-term inflammatory tumor responses or poor deoxyribonucleic acid repair mechanisms (for an overview, see Ahles & Root, 2018). Here, for the first time, we explore longitudinal changes of breast cancer treatment in electrophysiological functioning (cf., Hung et al., 2020). The ERPs were employed to explore early (P1 and N1) and late (P3 and SW) cognitive subprocesses before and after breast cancer treatment using a standard instrument (Attention Network Test; Spagna, Mackie, & Fan, 2015) that assesses attentional functioning in separate alerting, orienting, validity, and conflict networks.

Compensatory Mechanisms

Compensatory processes are invoked to explain maintenance of performance despite evidence for changes in brain structure and function. For example, several fMRI studies have reported (compensatory) overactivation in frontal regions in cancer patients both pre- and post-treatment compared with non-cancer controls, but no differences in performance during in-scanner tasks (Ferguson et al., 2007; McDonald et al., 2012; see Andryszak, Wilkosc, Izdebski, & Zurawski, 2017, for a review). These data have been interpreted as supporting the impact of cancer treatments on frontal structures. However, an alternate hypothesis is that increased frontal activation is an attempt to exert executive control when other areas of the brain are functioning non-optimally. For example, Pergolizzi and colleagues (2019) conducted an fMRI study that utilized a visual encoding and retrieval task (country and city scenes) to compare breast cancer patients and controls. Their results demonstrated equivalent task performance but demonstrated increased activation in frontal areas together with decreased activation in posterior brain regions involved in visual processing. Similarly, on a flanker task, Swainston and colleagues (2021) found no performance differences between cancer survivors and controls, but a disruption of response-locked ERPs related to monitoring cognitive performance, followed by a more effortful conscious response to allocate attentional resources after conscious awareness of an error. We consider compensatory executive control as one explanation of the results of the current study.

Current Study

The current study represents a pilot investigation associated with a larger project designed to examine the utility of methods and procedures based on cognitive neuroscience to study the cognitive change associated with cancer and cancer treatment. This is the first longitudinal investigation of electrophysiological changes assessed prior to and following adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. The EEG, which provides millisecond-level temporal resolution to measure the earliest phases of information processing, presents an ideal method to reveal how perceptual and attentional subprocesses may be altered in cancer patients. We recorded electrophysiological measures while patients and healthy controls performed the revised Attention Network Test (ANT-R; Spagna, Mackie, & Fan, 2015), which was used to evaluate four networks of attentional processing—alerting, orienting, validity, and conflict. Both groups were tested at two time points, 4-6 months apart, corresponding in patients to pre- and post-adjuvant treatment of radiation and/or chemotherapy. The ERPs were derived for early (P1 and N1) and late (P3 and SW) network processes and were compared with corresponding behavioral outcomes (RT and accuracy).

Materials and Methods

Participants

Patients (n = 15) were recruited from the Breast Cancer Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Patients were post-surgery for breast cancer between American Joint Committee on Cancer stages 0–3. Control participants (n = 24) were recruited through the Army of Women. All participants were women, fluent English speakers between ages 40 and 75 (see Table 1 for demographics). Exclusion criteria included a previous history of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer), history of radiation, hormonal, or chemotherapy agents, neurodegenerative disorder, stroke or serious head injury, psychosis, bipolar disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, substance use disorders, current unstable psychoactive medications, and a score > 10 on the Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test (Katzman et al., 1983). The Institutional Review Board of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center approved the protocol. Each participant was consented prior to assessment and compensated for participation. Patients and controls were evaluated in pretest and posttest sessions, 4-6 months apart, corresponding in patients to pre- and post-adjuvant treatment of radiation and/or chemotherapy (see Table 2 for treatment summary).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of cancer patients and healthy controls (SD in parentheses); patients were younger and scored more poorly on the WRAT than controls; patients reported significantly greater state anxiety (STAI) at pretest and significantly greater fatigue (FSI) at posttest compared with controls

| Patients (n = 15) | % | Controls (n = 24) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at pretest* | 51.9 (SD = 9.3) | 59.7 (SD = 7.9) | ||

| Race | ||||

| White or Caucasian | 8 | 53.3 | 23 | 95.8 |

| Black or African American | 2 | 13.3 | 0 | — |

| Asian | 4 | 26.7 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Other | 1 | 6.7 | 0 | — |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 | 13.3 | 0 | — |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 13 | 86.7 | 24 | 100.0 |

| Education | ||||

| High school graduate/GED | 1 | 6.7 | 0 | — |

| Assoc. degree/some college | 1 | 6.7 | 4 | 16.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 | 46.7 | 7 | 29.2 |

| Advanced degree | 5 | 33.3 | 13 | 54.2 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 6.7 | 0 | — |

| WRAT score at pretest* | 59.5 (7.2) | 67.3 (1.8) | ||

| STAI score | ||||

| Pretest* | 30.4 (9.2) | 25.1 (6.7) | ||

| Posttest | 31.6 (11.7) | 25.9 (8.9) | ||

| CES-D score | ||||

| Pretest | 5.8 (6.2) | 4.5 (6.2) | ||

| Posttest | 6.5 (7.0) | 4.8 (6.8) | ||

| FSI score | ||||

| Pretest | 21.4 (18.3) | 16.3 (14.5) | ||

| Posttest* | 27.5 (16.6) | 17.2 (14.90) | ||

STAI, State–Trait Anxiety Inventory; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Study-Depression; FSI, Fatigue Symptom Inventory.

* p < .05.

Table 2.

Summary of treatments for 15 breast cancer patients

| Description | Mean days (range) |

|---|---|

| Surgery to baseline | 42.0 (11–93) |

| Hormonal start to T2 | 141.7 (75–181) |

| Radiation end to T2 | 106.1 (0–161) |

| Non-Herceptin end to T2 | 64.3 (34–103) |

| Last Herceptin to T2 | 8.3 (5–14) |

| Mean N (range) | |

| Completed radiation treatments | 18.0 (4–29) |

| Completed non-Herceptin cycles | 12.0 (10–14) |

| Stage | N (%) |

| 0 | 3 (20.0) |

| Ia | 8 (53.3) |

| ib | 1 (6.7) |

| iia | 3 (20.0) |

| Chemotherapy | 3 (20.0) |

| Taxol + Herceptin | 2 (66.7) |

| Navelbine + Herceptin | 1 (33.3) |

| Hormone therapy | 9 (60.0) |

| Nolvadex (tamoxifen citrate) | 7 (77.8) |

| Femara (letrozole) | 2 (22.2) |

| Radiation therapy | 7 (46.67) |

Materials and Procedures

Participants completed a demographics questionnaire, self-reports on sensory and cognitive functioning (Sensory Gating Inventory; Hetrick, Erickson, & Smith, 2012; Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function; Wagner, Lai, Cella, Sweet, & Forrestal, 2004; and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General; Cella et al. 1993), and screenings for depression (Center for Epidemiologic Study-Depression; Radloff, 1977), anxiety (State–Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI]; Spielberger, 2010), fatigue (Fatigue Symptom Inventory [FSI]; Stein, Jacobsen, Blanchard, & Thors, 2004), and intellectual functioning (Wide Range Achievement Test Fourth Edition; Wilkinson & Robertson, 2006).

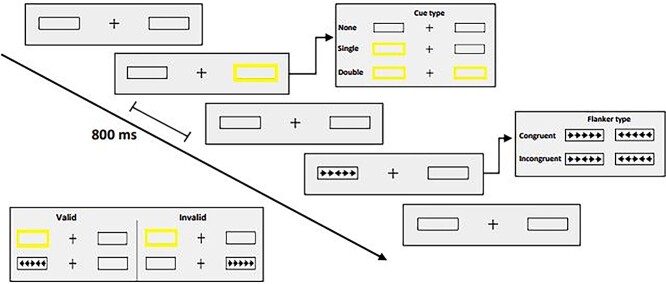

Participants subsequently completed a revised version of the Attention Network Test (ANT-R; Spagna et al., 2015) while electroencephalographic measures were recorded. Each test session of the ANT-R contained 144 experimental trials (preceded by 24 practice trials with feedback). Stimuli were created in Superlab 6.0 (Cedrus Corporation, San Pedro, CA) on a MacBook Pro 2016 laptop computer and were presented to participants at 50 cm on a 27-inch ASUS VG278HV computer monitor with a refresh rate of 60 Hz. On each trial, participants fixated a cross in the center of the screen while a thin black frame appeared on each side of fixation against a gray background (see Fig. 1). A brief yellow flash (i.e., changing the black frames to yellow for 100 ms) created one of three possible cue types: spatial cue (one frame flashed yellow; 96 trials), double cue (both frames flashed yellow; 24 trials), or no cue (no flash; 24 trials). Spatial cues were either valid (appeared in location of array; 72 trials) or invalid (appeared in opposite location; 24 trials). Following the cue (or black frames on no-cue trials), a horizontal array of five black arrows appeared for 500 ms within one of two frames, a center (target) arrow flanked by four (distractor) arrows pointing in the same (congruent trial) or opposite (incongruent trial) direction as the target. Each arrow subtended .58° of visual angle, separated by gaps subtending .06°. Participants were asked to indicate as quickly and accurately as possible the direction (left or right) of the target arrow using a button box response (Cedrus RB740). Cue-to-target onset was held at 800 ms, with a 1,700-ms response window from target onset. Time from target offset to next trial onset ranged from 2,000 to 12,000 ms using an approximation of the exponential distribution.

Fig. 1.

Summary of ANT design used in the study. Participants were asked to indicate the direction (left/right) of the center arrow in a flanker array of congruent or incongruent arrows, with each target preceded by either no cue, a double cue, or a valid or invalid spatial cue.

Data Recording and Analysis

The RT and accuracy scores were calculated for four network effects: orienting (double cue vs. valid cue), alerting (no cue vs. double cue), conflict (incongruent trial vs. congruent trial), and validity (invalid cue vs. valid cue; Spagna et al., 2015). Accuracies <65% (n = 1; patient) and latencies <200 ms and >1,700 ms (2.0% of trials at pretest; 1.6% at posttest) were excluded from analysis (Prashad, Melara, Root, & Ahles, 2022). We performed separate mixed-model repeated-measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) on each network effect using Statistica software, with Group (2 levels: patients and controls) as the between-subjects factor, Time (2 levels: pretest and posttest) and Cue (2 levels; e.g., valid network effect: invalid vs. valid) as within-subject factors, and Age and WRAT as covariates. We used G-power to determine sample size for within-between interactions in ANOVA under the assumption of moderate effect size (.25). Estimated power was .8, alpha = .05, and the critical F = 2.45 (two groups, six measurements, r = .75 among repeated measures, and ε = 1.0), leading to a sample size = 10.

Continuous EEG recording was obtained using BrainVision Recorder (Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany) at a sampling rate of 512 Hz using 16 Ag/AgCl electrodes arranged on an elastic cap. Trials containing mastoid activity >100 μV were removed. Trials contaminated by blinks, eye movements, or other movement artifacts were defined as z-values on the frontal and lower scalp sites exceeding 4.5 in a frequency band between 1 and 140 Hz; artifact trials were removed automatically using a Matlab routine (Fieldtrip; Oostenveld, Fries, Maris, & Schoffelen, 2011). The ERPs were restricted to trials involving a correct behavioral response to targets. Sweep time to each target stimulus (time-locked using Cedrus StimTracker with photodiode) was 1,200 ms, including a 200-ms pre-stimulus (re: target) baseline; signal-averaged waveforms, band-pass-filtered between .1 and 10 Hz, were referenced to linked mastoids. We measured both early (P1 and N1; Di Russo, Martinez, Sereno, Pitzalis, & Hillyard, 2002; Kayser & Tenke, 2006; Näätänen & Picton, 1987; Pincze, Lakatos, Rajkai, Ulbert, & Karmos, 2001) and late (P3 and SW; Donchin & Coles, 1988; Oostenveld & Praamstra, 2001; Picton, 1992; Polich & Herbst, 2000) ERP components separately for each ANT network effect (orienting, alerting, conflict, and validity) across three electrode sites: C3, Cz, and C4. Epochs were identified by visual inspection. The P1 amplitude was defined as the peak positive amplitude 18–54 ms after target onset. The N1 amplitude was defined as the peak negative amplitude 57–143 ms after the target onset. The P3 amplitude was defined as the peak positive amplitude 304–463 ms after target onset. The SW was defined as the average voltage 800–1,000 ms after the target onset.

The ANCOVAs of ERP amplitudes mimicked behavioral analyses, with Group (2 levels: patients and controls) as the between-subjects factor, Time (2 levels: pretest and posttest), Cue (2 levels; e.g., validity network effect: invalid vs. valid) as within-subject factor, and Age and WRAT as covariates. To guard against violations to assumptions of sphericity, all significant results are reported using the Greenhouse-Geiser correction (Greenhouse & Geisser, 1959).

Results

Behavioral Performance

Patients were younger and scored more poorly on the WRAT than controls (see Table 1); we therefore included age and WRAT as covariates in our behavioral and ERP analyses. Patients reported significantly greater state anxiety (STAI) at pretest and significantly greater fatigue (FSI) at posttest compared with controls. Table 3 contains a summary of behavioral performance (RTs and accuracy) for each network score (alerting, orienting, validity, and conflict) and cue type in each group. The correlation between speed and accuracy in the ANT-R, calculated from averaged behavioral scores to each cue, was r = .26, indicating the absence of trade-off between speed and accuracy. Main effects of Cue were found on both behavioral measures for Alerting, (RT: F(1, 37) = 86.98, p < .001, MSe = 2,925.74, η2 = .05; Accuracy: F(1, 37) = 8.15, p < .01, MSe = 2.02, η2 < .01), Orienting (RT: F(1, 37) = 134.65, p < .001, MSe = 2,241.80, η2 = .06; Accuracy: F(1, 37) = 19,817.29, p < .001, MSe = 4.02, η2 = .01), Validity (RT: F(1, 37) = 145.37, p < .001, MSe = 7,695.98, η2 = .21; Accuracy: F(1, 37) = 1,931.92, p < .001, MSe = 40.23, η2 = .01), and Conflict (RT: F(1, 37) = 371.16, p < .001, MSe = 2,154.27, η2 = .15; Accuracy: F(1, 37) = 22.88, p < .001, MSe = 23.22, η2 < .01), confirming that all attentional manipulations were effective. However, there were no effects of Group and no interactions involving Group (ps > .10), indicating that behavioral network effects were equivalent between patients and controls.

Table 3.

Summary of average RT and percent correct (SDs in parentheses) for patients and healthy controls in each of four networks (altering, orienting, conflict, and validity) and six trial types (congruent, incongruent, no cue, double cue, valid cue, and invalid cue) in ANT-R at pretest and posttest; there were no effects of Group and no interactions involving Group (ps > .10), indicating that behavioral network effects were equivalent between patients and controls

| Pretest | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 15) | Controls (n = 24) | ||||

| Network scores (SD) | Network scores (SD) | ||||

| Networks | Alerting | 78.3 (63.5) | 71.8 (62.6) | ||

| Orienting | 91.3 (48.4) | 97.0 (70.6) | |||

| Conflict | 157.2 (60.3) | 158.1 (56.2) | |||

| Validity | 181.6 (84.9) | 169.1 (115.0) | |||

| Trial types | RTs (SD) | Accuracy (SD) | RTs (SD) | Accuracy (SD) | |

| Congruent | 779.9 (121.0) | 95.7 (4.9) | 746.0 (87.0) | 96.7 (4.9) | |

| Incongruent | 937.1 (127.5) | 93.7 (4.6) | 904.1 (103.9) | 91.9 (7.9) | |

| No cue | 955.1 (117.3) | 91.7 (9.4) | 920.2 (109.1) | 90.5 (10.5) | |

| Double cue | 876.8 (118.9) | 93.1 (5.4) | 848.4 (107.5) | 93.6 (6.9) | |

| Valid cue | 785.5 (130.7) | 95.3 (3.5) | 751.4 (96.8) | 95.4 (5.9) | |

| Invalid cue | 967.1 (136.2) | 88.9 (9.7) | 920.5 (116.7) | 90.8 (11.1) | |

| Posttest | |||||

| Network scores (SD) | Network scores (SD) | ||||

| Networks | Alerting | 68.2 (74.2) | 80.4 (54.9) | ||

| Orienting | 98.8 (47.4) | 74.5 (73.9) | |||

| Conflict | 124.8 (37.4) | 148.5 (52.0) | |||

| Validity | 176.3 (65.4) | 164.5 (93.0) | |||

| Trial types | RTs (SD) | Accuracy (SD) | RTs (SD) | Accuracy (SD) | |

| Congruent | 789.8 (142.8) | 95.9 (5.9) | 719.6 (79.7) | 98.6 (2.1) | |

| Incongruent | 914.6 (137.5) | 93.6 (6.7) | 868.1 (96.4) | 92.6 (7.7) | |

| No cue | 945.9 (135.3) | 90.8 (10.8) | 882.1 (92.1) | 89.9 (7.6) | |

| Double cue | 877.6 (162.4) | 93.3 (8.6) | 801.6 (83.4) | 95.8 (6.7) | |

| Valid cue | 778.8 (145.8) | 94.2 (8.6) | 727.1 (97.4) | 97.2 (2.9) | |

| Invalid cue | 955.1 (125.8) | 110.8 (14.8) | 891.6 (86.5) | 107.2 (12.3) | |

ERP Effects

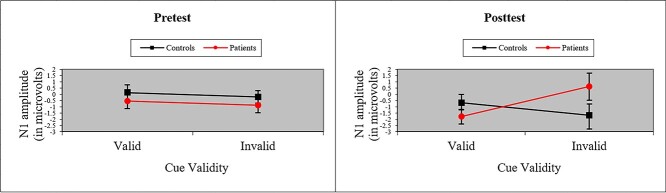

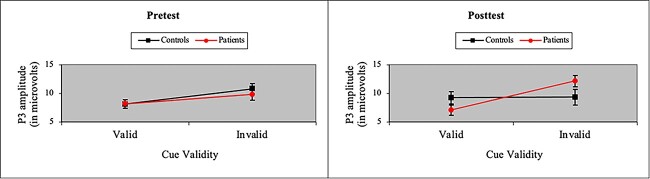

Table 4 contains a summary of peak ERP voltage and latency (P1, N1, P3, and SW components) for each network score (Alerting, Orienting, Validity, and Conflict) and cue type in each group. The ANOVA of ERPs to the target revealed no effects of Group and no interactions involving Group for Alerting, Orienting, or Conflict network scores. However, as depicted in Fig. 2, ANOVA of N1 amplitude to valid and invalid cues (i.e., Validity network) revealed a significant Group × Cue × Time interaction, F(1, 37) = 6.29, p < .05, MSe = 13.11, η2 = .01, with patients showing significant loss of N1 amplitude to invalid cues at posttest, suggesting difficulty re-orienting to targets after treatment. There were no effects of P1 amplitude (ps > .10). An analysis of P1 and N1 latencies of validity cues uncovered a Group × Cue interaction for both components (P1: F(1, 37) = 10.99, p < .01, MSe = 0.0003, η2 = .02; N1: F(1, 37) = 10.19, p < .01, MSe = 0.001, η2 = .03), demonstrating that patients suffered a delay in sensory/perceptual processing of invalid cues even at pre-treatment. Both latency components also revealed a main effect of Cue (P1: F(1, 37) = 18.70, p < .001, MSe = 0.0003, η2 = .04; N1: F(1, 37) = 30.43, p < .001, MSe = 0.001, η2 = .07) because processing was relatively slow to invalid cues.

Table 4.

Summary of peak ERP voltage and latency (P1, N1, P3, and Slow Wave components; SDs in parentheses) for patients and healthy controls in each of four networks (altering, orienting, conflict, and validity) and six trial types (congruent, incongruent, no cue, double cue, valid cue, and invalid cue) in ANT-R at pretest and posttest

| Pretest | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 15) | Controls (n = 24) | |||||||||

| Peak (SD) | Latency (SD) | Peak (SD) | Latency (SD) | |||||||

| Alertness | No cue | Double | No cue | Double | No cue | Double | No cue | Double | ||

| P1 | 0.41 (1.2) | 0.54 (1.3) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.02) | P1 | 1.0 (0.90) | 0.87 (0.97) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.01) | |

| N1 | 0.28 (1.3) | 0.28 (1.6) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.02) | N1 | 0.79 (1.1) | 0.58 (1.3) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | |

| Slow | 0.04 (1.9) | 0.28 (1.4) | Slow | −0.06 (2.6) | 0.91 (2.3) | |||||

| Orienting | Valid | Double | Valid | Double | Valid | Double | Valid | Double | ||

| P1 | 0.83 (1.9) | 0.54 (1.3) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.02) | P1 | 1.9 (1.4) | 0.87 (0.97) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.01) | |

| N1 | −0.54 (2.4) | 0.28 (1.6) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.02) | N1 | 0.14 (3.3) | 0.58 (1.3) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | |

| P3 | 8.1 (2.9) | 4.5 (1.1) | 0.36 (0.05) | 0.35 (0.03) | P3 | 8.1 (3.8) | 4.9 (2.9) | 0.36 (0.03) | 0.35 (0.03) | |

| Slow | 3.7 (6.4) | 0.28 (1.4) | Slow | 3.0 (5.9) | 0.91 (2.3) | |||||

| Congruity | Con | Incon | Con | Incon | Con | Incon | Con | Incon | ||

| P1 | 1.1 (2.1) | 1.7 (1.8) | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.02) | P1 | 1.7 (1.9) | 1.9 (1.5) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.02) | |

| N1 | −0.25 (2.0) | 0.28 (2.3) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | N1 | −0.10 (1.9) | −0.04 (2.9) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | |

| P3 | 7.2 (2.7) | 6.9 (2.4) | 0.36 (0.03) | 0.35 (0.02) | P3 | 7.2 (3.5) | 7.0 (3.8) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.35 (0.02) | |

| Slow | 4.3 (3.0) | 3.6 (1.7) | Slow | 6.0 (5.4) | 6.0 (4.1) | |||||

| Validity | Valid | Invalid | Valid | Invalid | Valid | Invalid | Valid | Invalid | ||

| P1 | 0.83 (1.9) | 2.3 (2.2) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | P1 | 1.9 (1.4) | 2.0 (2.7) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | |

| N1 | −0.54 (2.4) | −0.89 (2.3) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.11 (0.02) | N1 | 0.14 (3.3) | −0.20 (2.5) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | |

| P3 | 8.1 (2.9) | 9.8 (4.0) | 0.36 (0.05) | 0.35 (0.04) | P3 | 8.1 (3.9) | 1.8 (4.5) | 0.36 (0.03) | 0.34 (0.04) | |

| Slow | 3.7 (6.4) | 3.8 (2.9) | Slow | 3.0 (5.9) | 4.6 (4.2) | |||||

| Posttest | ||||||||||

| Peak (SD) | Latency (SD) | Peak (SD) | Latency (SD) | |||||||

| Alertness | No Cue | Double | No Cue | Double | No Cue | Double | No Cue | Double | ||

| P1 | 0.28 (1.2) | −0.10 (0.66) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.02) | P1 | 0.35 (0.85) | 0.46 (1.2) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.01) | |

| N1 | −0.22 (1.4) | −0.34 (1.1) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.08 (0.02) | N1 | −0.16 (1.1) | 0.07 (1.3) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | |

| Slow | 1.5 (3.2) | 1.8 (3.4) | Slow | 0.38 (2.8) | 1.2 (2.9) | |||||

| Orienting | Valid | Double | Valid | Double | Valid | Double | Valid | Double | ||

| P1 | −0.06 (1.7) | −0.10 (0.66) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.02) | P1 | 1.1 (2.1) | 0.46 (1.2) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.01) | |

| N1 | −1.8 (2.3) | −0.35 (1.1) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.08 (0.02) | N1 | −0.66 (3.5) | 0.07 (1.3) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | |

| P3 | 7.0 (3.6) | 5.2 (2.2) | 0.37 (0.05) | 0.34 (0.02) | P3 | 9.2 (5.0) | 5.21 (2.8) | 0.37 (0.04) | 0.35 (0.03) | |

| Slow | 5.6 (5.5) | 1.8 (3.3) | Slow | 5.7 (6.9) | 1.2 (2.9) | |||||

| Congruity | Con | Incon | Con | Incon | Con | Incon | Con | Incon | ||

| P1 | 0.94 (1.7) | 0.35 (1.6) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.02) | P1 | 1.4 (1.8) | 1.1 (2.0) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.02) | |

| N1 | −0.99 (2.5) | −1.2 (1.9) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | N1 | −0.90 (2.9) | −0.72 (2.8) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | |

| P3 | 6.8 (3.4) | 6.2 (3.6) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.35 (0.02) | P3 | 6.8 (4.4) | 6.9 (4.2) | 0.36 (0.03) | 0.36 (0.02) | |

| Slow | 7.0 (5.5) | 7.3 (4.9) | Slow | 7.2 (4.5) | 7.9 (3.7) | |||||

| Validity | Valid | Invalid | Valid | Invalid | Valid | Invalid | Valid | Invalid | ||

| P1 | −0.06 (1.7) | 1.6 (2.9) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | P1 | 1.1 (2.1) | 1.4 (2.6) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | |

| N1 | −1.8 (2.3) | 0.61 (4.2) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | N1 | −0.66 (3.5) | −1.7 (4.0) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.10 (0.02) | |

| P3 | 7.0 (3.6) | 12.2 (3.8) | 0.37 (0.05) | 0.34 (0.03) | P3 | 9.2 (5.0) | 9.3 (6.2) | 0.37 (0.04) | 0.34 (0.03) | |

| Slow | 5.6 (5.5) | 1.4 (8.3) | Slow | 5.7 (6.9) | 6.4 (5.1) | |||||

Fig. 2.

Average amplitude (with standard error bars) of the N1 ERP component to targets following valid and invalid cues for cancer patients and healthy controls at pretest and posttest. Patients showed significant loss of N1 amplitude to invalid cues at posttest, suggesting difficulty re-orienting to targets after treatment.

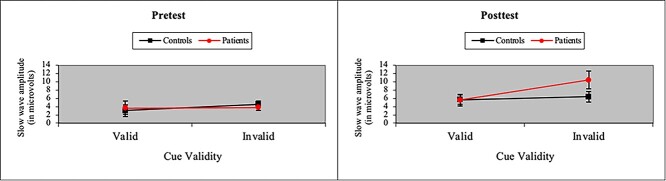

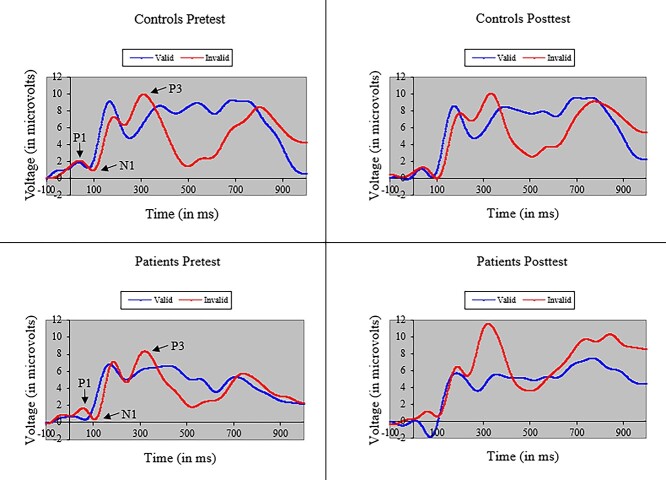

The ANOVA of P3 amplitude in the Validity network also yielded a main effect of Cue (i.e., larger P3 amplitude to invalid cues), F(1, 37) = 16.37, p < .001, MSe = 38.72, η2 = .04. More importantly, we found a P3 treatment effect in patients in processing cue validity. As shown in Fig. 3, we observed a Group × Cue × Time interaction when participants were presented with valid and invalid cues, F(1, 37) = 12.05, p < .01, MSe = 20.78, η2 = .01. However, in contrast to the N1 effect of treatment, the P3 effect arose because P3 amplitude to invalid cues was significantly greater in patients than controls after treatment. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4, a similar, albeit marginal, three-way interaction was observed in SW amplitude, F(1, 37) = 3.63, p = .06, MSe = 60.60, η2 = .03, with SW amplitude to invalid cues greater in patients than controls after treatment. The SW also showed main effects of cue validity (i.e., larger SW amplitude to invalid cues), F(1, 37) = 5.32, p < .05, MSe = 67.63, η2 = .01, and time (i.e., larger SW amplitude at posttest), F(1, 37) = 12.88, p < .001, MSe = 89.86, η2 = .04. Figure 5 depicts grand-averaged ERP waveforms at Cz to targets following valid and invalid cues for cancer patients and healthy controls at pretest and posttest.

Fig. 3.

Average amplitude (with standard error bars) of the P3 ERP component to targets following valid and invalid cues for cancer patients and healthy controls at pretest and posttest. P3 amplitude to invalid cues was significantly greater in patients than controls after treatment.

Fig. 4.

Average amplitude (with standard error bars) of the SW ERP component (800–1,000 ms after target onset) to targets following valid and invalid cues for cancer patients and healthy controls at pretest and posttest. The amplitude of the slow wave to invalid cues was slightly greater (p = .06) in patients than controls after treatment.

Fig. 5.

Grand-averaged ERP waveforms at Cz to targets following valid and invalid cues for cancer patients and healthy controls at pretest and posttest.

Discussion

In this first longitudinal investigation of electrophysiological change from breast cancer treatment, we sought to evaluate possible neural and behavioral effects of cancer treatment on attentional processing in patients compared with healthy controls in each of four attentional networks—alerting, orienting, validity, and conflict. We found no group differences in behavioral performance from pretest to posttest. However, we did uncover significant ERP effects of cancer treatment in the validity attentional network: After treatment, patients revealed a suppressed early (N1) response, and an exaggerated late (P3) response, to invalid cues. We also found a marginal increase to invalid cues in the sustained SW response.

The Role of Cue Validity in Spatial Attention

The presentation of invalid cues within spatial cuing paradigms, such as the ANT-R, commonly leads to increased activation in the right Temporal–Parietal Junction (TPJ) following target onset (Doricchi, Macci, Silvetti, & Macaluso, 2010). Invalid predictive cues require participants to reorient attention from an incorrect to a correct spatial location once the target is presented. In predictive coding models of visual cognition (Summerfield & Egner, 2009), TPJ activation is thought to generate a prediction error signal within a match/mismatch system requiring later top-down modulation (Macaluso & Doricchi, 2013). Previous ERP research with healthy adults demonstrates that invalid cues trigger an enhanced effect on both early (N1; Eimer, 1993) and late (P3; Gómez, Flores, Digiacomo, Ledesma, & González-Rosa, 2008) ERP components relative to valid cues. In the context of predictive coding, the increased N1 amplitude to incorrectly predicted targets may represent encoding of the prediction error signal, whereas the enhanced P3 amplitude may reflect a context-updating operation and the storage of new corrective information in working memory (Donchin & Coles, 1988).

In the current study, both patients and healthy controls showed the typical enhancement of N1 and P3 components to invalid cues at pretest. However, after breast cancer treatment, these cues engendered in patients a diminution of N1 amplitude and a significant enhancement in P3 amplitude. One interpretation suggests that invalid cues triggered a weaker error signal in sensory/perceptual coding (cf. Swainston et al., 2021), which then required greater top-down control of context updating in later processing to correctly classify target stimuli. The effects of treatment on SW amplitude, a measure of attentional inhibition to irrelevant information (Chen & Melara, 2014), suggest that patients implement sustained inhibitory control of invalid cues, perhaps as a compensatory strategy. The current results suggest a cascade of change from sensory to executive processing, which is in concert with results we have reported previously about cancer survivors (Melara et al., 2021).

Examination of ERP latencies revealed group differences in early neural functioning even at pretest: Patients showed delays in P1 and N1 peaks to invalid cues at both pretest and posttest. Previous research has also identified group differences before treatment (e.g., McDonald et al., 2012) and, as we report in a separate study, even in the current ANT-R paradigm using a different EEG methodology (e.g., frontal alpha asymmetry; Prashad et al., 2022). Our findings here suggest that pre-treatment effects of cancer on the time course of processing may be exacerbated by treatment and lead to further deficits in processing cue validity (e.g., in N1 and P3 amplitudes). Our findings point to delays in sensory/perceptual functioning, as measured by EEG, as a potential neural correlate in pre-treatment cancer patients, which might be employed to predict neural and behavioral losses after treatment.

Absence of Treatment Effects on Behavioral Performance

Chen and colleagues (2014) employed the original ANT paradigm to investigate in a group of survivors the behavioral effects of breast cancer treatment on three attention network scores: alerting, orienting, and conflict (cue validity was not tested). The authors found that survivors (i.e., 1 month after chemotherapy) performed significantly worse than healthy controls in the alerting and conflict networks. In the current study, we found no neural or behavioral effects of group in these networks during either pretest or posttest. Although differences in design and treatment regimen between studies make direct comparisons difficult (e.g., our participants completed the ANT twice [pretest and posttest], whereas participants in Chen et al., 2014 had only a single task exposure), one interpretation for the absence of treatment effects here argues for the emergence of neural deficits of treatment prior to behavioral ones. Indeed, the increased (and sustained) top-down control after treatment seen in the P3 and SW effects to invalid cues may have arisen from greater attentional effort patients exerted to compensate for early sensory (N1) loss of cue information. This explanation fits with neuroimaging studies indicating the operation of compensatory neural mechanisms in survivors to maintain working memory functions (McDonald et al., 2012) and neurotypical levels of performance on cognitive and neuropsychological tests (Hermelink et al., 2007; Pullens et al., 2010). Cancer treatment has been hypothesized to accelerate the effects of aging (Chen et al., 2022), perhaps undermining compensatory strategies. We might anticipate, therefore, that the neurophysiological effects of treatment to cue validity found here precede later behavioral effects to cue validity, and also later behavioral (and neurophysiological) effects of treatment in other network measures, such as orienting and conflict, as Chen et al. (2014) reported. Continued follow-up of these patients as part of the larger study is thus needed to reveal any possible treatment effects that emerge as compensatory mechanisms potentially fail.

Limitations

The current study represents a pilot exploration of the longitudinal effects of cancer treatment. Hence, the sample and effect sizes were small and required replication later with larger samples. Patients were younger and scored more poorly on the WRAT than controls. Moreover, as Table 2 reveals, patients received a variety of treatments, but the small sample size made it impossible to break out the effects of specific treatments. As discussed before, cognitive dysfunction in survivors often only emerges many months after treatment (Chen et al., 2022), necessitating follow-up on these patients at subsequent time points.

Conclusions

The current study is the first to demonstrate a longitudinal effect of breast cancer treatment on electrophysiological functioning (see also Hung et al., 2020). The results indicate that after treatment patients have difficulty reorienting attention to targets when distracted with misleading cues, a disruption that begins in early sensory/perceptual processing and extends to top-down executive processes. The study points to the value of measures and methods based in cognitive neuroscience as a frontline gage of cognitive decline, potentially revealing how early cognitive subprocesses are affected by disease and treatment.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (R01 CA218496).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Contributor Information

Robert D Melara, Department of Psychology, City College, City University of New York, New York, New York, USA.

Tim A Ahles, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science Services, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Neelam Prashad, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science Services, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Madalyn Fernbach, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science Services, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

Jay A Edelman, Department of Biology, City College, City University of New York, New York, New York, USA.

James Root, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science Services, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

References

- Ahles, T. A., & Root, J. C. (2018). Cognitive effects of cancer and cancer treatments. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 425–451. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles, T. A., Root, J. C., & Ryan, E. L. (2012). Cancer- and cancer treatment-associated cognitive change: An update on the state of the science. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(30), 3675–3686. 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andryszak, P., Wilkosc, M., Izdebski, P., & Zurawski, B. (2017). A systemic literature review of neuroimaging studies in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Contemporary Oncology (Pozn), 21(1), 6–15. 10.5114/wo.2017.66652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balash, Y., Mordechovich, M., Shabtai, H., Giladi, N., Gurevich, T., & Korczyn, A. D. (2013). Subjective memory complaints in elders: Depression, anxiety, or cognitive decline? Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 127(5), 344–350. 10.1111/ane.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella, D. F., Tulsky, D. S., Gray, G., Sarafian, B., Linn, E., Bonomi, A., et al. (1993). The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 11(3), 570–579. 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B. T., Chen, Z., Patel, S. K., Rockne, R. C., Wong, C. W., Root, J. C., et al. (2022). Effect of chemotherapy on default mode network connectivity in older women with breast cancer. Brain Imaging and Behavior., 16(1), 43–53. 10.1007/s11682-021-00475-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B. T., Ye, N., Wong, C. W., Patel, S. K., Jin, T., Sun, C. L., et al. (2020). Effects of chemotherapy on aging white matter microstructure: A longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging study. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 11(2), 290–296. 10.1016/j.jgo.2019.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., & Melara, R. D. (2014). Rejection positivity predicts trial-to-trial reaction times in an auditory selective attention task: A computational analysis of inhibitory control. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 585. 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., Li, J., Ren, J., Hu, X., Zhu, C., Tian, Y., et al. (2014). Selective impairment of attention networks in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy treatment. Psycho-Oncology, 23(10), 1165–1171. 10.1002/pon.3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., Li, J., Zhang, J., He, X., Zhu, C., Zhang, L., et al. (2017). Impairment of the executive attention network in premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 75, 116–123. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H., Li, W., Gong, L., Xuan, H., Huang, Z., Zhao, H., et al. (2017). Altered resting-state hippocampal functional networks associated with chemotherapy-induced prospective memory impairment in breast cancer survivors. Scientific Reports, 7, 45135. 10.1038/srep45135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H., Yang, Z., Dong, B., Chen, C., Zhang, M., Huang, Z., et al. (2013). Chemotherapy-induced prospective memory impairment in patients with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 22(10), 2391–2395. 10.1002/pon.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez, S., Amant, F., Smeets, A., Peeters, R., Leemans, A., Van Hecke, W., et al. (2012). Longitudinal assessment of chemotherapy-induced structural changes in cerebral white matter and its correlation with impaired cognitive functioning. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(3), 274–281. 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Russo, F., Martinez, A., Sereno, M. I., Pitzalis, S., & Hillyard, S. A. (2002). Cortical sources of the early components of the visual evoked potential. Human Brain Mapping, 15(2), 95–111. 10.1002/hbm.10010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donchin, E., & Coles, M. G. (1988). Is the P300 component a manifestation of context updating? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 11(3), 357–374. 10.1017/S0140525X00058027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doricchi, F., Macci, E., Silvetti, M., & Macaluso, E. (2010). Neural correlates of the spatial and expectancy components of endogenous and stimulus-driven orienting of attention in the Posner task. Cerebral Cortex, 20(7), 1574–1585. 10.1093/cercor/bhp215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimer, M. (1993). Spatial cueing, sensory gating and selective response preparation: An ERP study on visuo-spatial orienting. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section, 88(5), 408–420. 10.1016/0301-0511(93)90009-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, R. J., Ahles, T. A., Saykin, A. J., McDonald, B. C., Furstenberg, C. T., Cole, B. F., et al. (2007). Cognitive-behavioral management of chemotherapy-related cognitive change. Psycho-Oncology, 16(8), 772–777. 10.1002/pon.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandal, M. J., Ehrlichman, R. S., Rudnick, N. D., & Siegel, S. J. (2008). A novel electrophysiological model of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairments in mice. Neuroscience, 157(1), 95–104. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, P. A., Bower, J. E., Kwan, L., Castellon, S. A., Silverman, D. H., Geist, C., et al. (2013). Does tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) play a role in post-chemotherapy cerebral dysfunction? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 30, S99–S108. 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor, A. M., Ahles, T. A., Ryan, E., Schofield, E., Li, Y., Patel, S. K., et al. (2021). Initial encoding deficits with intact memory retention in older long-term breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship.. 10.1007/s11764-021-01086-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, C. M., Flores, A., Digiacomo, M. R., Ledesma, A., & González-Rosa, J. (2008). P3a and P3b components associated to the neurocognitive evaluation of invalidly cued targets. Neuroscience Letters, 430(2), 181–185. 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse, S. W., & Geisser, S. (1959). On methods in the analysis of profile data. Psychometrika, 24(2), 95–112. 10.1007/BF02289823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hermelink, K., Untch, M., Lux, M. P., Kreienberg, R., Beck, T., Bauerfeind, I., et al. (2007). Cognitive function during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: Results of a prospective, multicenter, longitudinal study. Cancer, 109(9), 1905–1913. 10.1002/cncr.22610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick, W. P., Erickson, M. A., & Smith, D. A. (2012). Phenomenological dimensions of sensory gating. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(1), 178–191. 10.1093/schbul/sbq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, T. S., Suls, J., & Treviño, M. (2018). A call for a neuroscience approach to cancer-related cognitive impairment. Trends in Neurosciences, 41(8), 493–496. 10.1016/j.tins.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung, S. H., Mutti Jaswal, S., Neil-Sztramko, S. E., Kam, J. W. Y., Niksirat, N., Liu-Ambrose, T., et al. (2020). A hypothesis-generating study using electrophysiology to examine cognitive function in colon cancer patients. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 35(2), 226–232. 10.1093/arclin/acz051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam, J. W. Y., Brenner, C. A., Handy, T. C., Boyd, L. A., Liu-Ambrose, T., Lim, H. J., et al. (2016). Sustained attention abnormalities in breast cancer survivors with cognitive deficits post chemotherapy: An electrophysiological study. Clinical Neurophysiology, 127(1), 369–378. 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman, R., Brown, T., Fuld, P., Peck, A., Schechter, R., & Schimmel, H. (1983). Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140(6), 734–739. 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser, J., & Tenke, C. E. (2006). Principal components analysis of Laplacian waveforms as a genericmethod for identifying ERP generator patterns: I. Evaluation with auditory oddball tasks. Clinical Neurophysiology, 117(2), 348–368. 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesler, S. R., Rao, A., Blayney, D. W., Oakley-Girvan, I. A., Karuturi, M., & Palesh, O. (2017). Predicting long-term cognitive outcome following breast cancer with pre-treatment resting state fMRI and random forest machine learning. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 555. 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreukels, B. P., Hamburger, H. L., deRuiter, M. B., vanDam, F. S., Ridderinkhof, K. R., Boogerd, W., et al. (2008). ERP amplitude and latency in breast cancer survivors treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Clinical Neurophysiology, 119(3), 533–541. 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreukels, B. P., Schagen, S. B., Ridderinkhof, K. R., Boogerd, W., Hamburger, H. L., Muller, M. J., et al. (2006). Effects of high-dose and conventional-dose adjuvant chemotherapy on long-term cognitive sequelae in patients with breast cancer: An electrophysiologic study. Clinical Breast Cancer, 7(1), 67–78. 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreukels, B. P., vanDam, F. S., Ridderinkhof, K. R., Boogerd, W., & Schagen, S. B. (2008). Persistent neurocognitive problems after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Clinical Breast Cancer, 8(1), 80–87. 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso, E., & Doricchi, F. (2013). Attention and predictions: Control of spatial attention beyond the endogenous-exogenous dichotomy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 685. 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, B. C., Conroy, S. K., Ahles, T. A., West, J. D., & Saykin, A. J. (2010). Gray matter reduction associated with systemic chemotherapy for breast cancer: A prospective MRI study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 123(3), 819–828. 10.1007/s10549-010-1088-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, B. C., Conroy, S. K., Ahles, T. A., West, J. D., & Saykin, A. J. (2012). Alterations in brain activation during working memory processing associated with breast cancer and treatment: A prospective functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(20), 2500–2508. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melara, R. D., Root, J. C., Bibi, R., & Ahles, T. A. (2021). Sensory filtering and sensory memory in breast cancer survivors. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 52(4), 246–253. 10.1177/1550059420971120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihuta, M. E., Green, H. J., Man, D. W. K., & Shum, D. H. K. (2016). Correspondence between subjective and objective cognitive functioning following chemotherapy for breast cancer. Brain Impairment, 17(3), 222–232. 10.1017/BrImp.2016.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, H. C., Parsons, M. W., Yue, G. H., Rybicki, L. A., & Siemionow, W. (2014). Electroencephalogram power changes as a correlate of chemotherapy-associated fatigue and cognitive dysfunction. Support Care Cancer, 22(8), 2127–2131. 10.1007/s00520-014-2197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näätänen, R., & Picton, T. (1987). The N1 wave of the human electric and magnetic response to sound: A review and an analysis of the component structure. Psychophysiology, 24(4), 375–425. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostenveld, R., Fries, P., Maris, E., & Schoffelen, J. M. (2011). FieldTrip: Open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2011, 156869. 10.1155/2011/156869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostenveld, R., & Praamstra, P. (2001). The five percent electrode system for high-resolution EEG and ERP measurements. Clinical Neurophysiology, 112(4), 713–719. 10.1016/S1388-2457(00)00527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. Y., Lee, H., Sohn, J., An, S. K., Namkoong, K., & Lee, E. (2021). Increased resting-state cerebellar-cortical connectivity in breast cancer survivors with cognitive complaints after chemotherapy. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–9. 10.1038/s41598-021-91447-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pergolizzi, D., Root, J. C., Pan, H., Silbersweig, D., Stern, E., Passik, S. D., et al. (2019). Episodic memory for visual scenes suggests compensatory brain activity in breast cancer patients: A prospective longitudinal fMRI study. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 13(6), 1674–1688. 10.1007/s11682-019-00038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picton, T. W. (1992). The P300 wave of the human event-related potential. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 9(4), 456–479. 10.1097/00004691-199210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincze, Z., Lakatos, P., Rajkai, C., Ulbert, I., & Karmos, G. (2001). Separation of mismatch negativity and the N1 wave in the auditory cortex of the cat: A topographic study. Clinical Neurophysiology, 112(5), 778–784. 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich, J., & Herbst, K. L. (2000). P300 as a clinical assay: Rationale, evaluation, and findings. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 38(1), 3–19. 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prashad, N., Melara, R. D., Root, J. C., & Ahles, T. A. (2022). Pre-treatment breast cancer patients show neural differences in frontal alpha asymmetry. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 1–9. 10.1177/15500594221074860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullens, M. J., De Vries, J., & Roukema, J. A. (2010). Subjective cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 19(11), 1127–1138. 10.1002/pon.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Root, J. C., Andreotti, C., Tsu, L., Ellmore, T. M., & Ahles, T. A. (2016). Learning and memory performance in breast cancer survivors 2 to 6 years post-treatment: The role of encoding versus forgetting. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 10(13), 593–599. 10.1007/s11764-015-0505-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagna, A., Mackie, M. A., & Fan, J. (2015). Supramodal executive control of attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 65. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C. D. (2010). State-Trait anxiety inventory. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. 1(1). 10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, K. D., Jacobsen, P. B., Blanchard, C. M., & Thors, C. (2004). Further validation of the multidimensional fatigue symptom inventory-short form. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 27(1), 14–23. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield, C., & Egner, T. (2009). Expectation (and attention) in visual cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(9), 403–409. 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swainston, J., Louis, C., Moser, J., & Derakshan, N. (2021). Neurocognitive efficiency in breast cancer survivorship: A performance monitoring ERP study. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 168, 9–20. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyk, K., Hunter, A. M., Ercoli, L., Petersen, L., Leuchter, A. F., & Ganz, P. A. (2017). Evaluating cognitive complaints in breast cancer survivors with the FACT-Cog and quantitative electroencephalography. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 166(1), 157–166. 10.1007/s10549-017-4390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, L. I., Lai, J. S., Cella, D., Sweet, J., & Forrestal, S. (2004). Chemotherapy-related cognitive deficits: Development of the FACT-Cog instrument. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 27(S10). [Google Scholar]

- Wefel, J. S., Kesler, S. R., Noll, K. R., & Schagen, S. B. (2015). Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA: a Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 65(2), 123–138. 10.3322/caac.21258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wefel, J. S., Saleeba, A. K., Buzdar, A. U., & Meyers, C. A. (2010). Acute and late onset cognitive dysfunction associated with chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer, 116(14), 3348–3356. 10.1002/cncr.25098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, G. S., & Robertson, G. J. (2006). WRAT4: Wide range achievement test. Psychological Assessment Resources., 52(1), 57–60. 10.1177/0034355208320076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wirkner, J., Weymar, M., Löw, A., Hamm, C., Struck, A., Kirschbaum, C., et al. (2017). Cognitive functioning and emotion processing in breast cancer survivors and controls: An ERP pilot study. Psychophysiology, 54(8), 1209–1222. 10.1111/psyp.12874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]