Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. Evodiamine, a main component in Chinese medicine, was found to improve cognitive impairment in AD model mice based on several intensive studies. However, evodiamine has high cytotoxicity and poor bioactivity. In this study, several evodiamine derivatives were synthesized via heterocyclic substitution and amide introduction and screened for cytotoxicity and antioxidant capacity. Under the same concentrations, compound 4c was found to exhibit lower cytotoxicity and higher activity against H2O2 and amyloid β oligomers (AβOs) than evodiamine in vitro and significantly improve the working memory and spatial memory of 3 x Tg and APP/PS1 AD mice. Subsequent RNA sequencing and pathway enrichment analysis showed that 4c affected AD-related genes and the AMPK and insulin signaling pathways. Furthermore, we confirmed that 4c recovered PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/Tau dysfunction in vivo and in vitro. In conclusion, 4c represents a potential lead compound for AD therapy based on the recovery of PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway dysfunction.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, evodiamine, Tau hyperphosphorylation, PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway, Aβ pathology

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common type of dementia, is a devastating illness that causes progressive neurodegenerative changes and cognitive decline. AD currently affects 43.8 million people worldwide, and the incidence of AD is expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades (GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators., 2019). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or mutations in more than 100 genes have been linked to the increased risk of AD, including App, Psen1, Psen2, Apoe, Trem2, Pon1, Aph1b, Adam10, Clu, Abca7, Slc24a4, and Tomm40 (Cacace et al., 2016; Nie et al., 2017; Chiba-Falek et al., 2018; Kim, 2018; De Roeck et al., 2019; Bertram and Tanzi, 2020). In addition to genetic factors, several acquired factors have been found to increase AD risk, including cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, neurotoxicity, depression, age, and social culture (Silva et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). Despite the rapid developments in AD pathophysiology, the etiology of AD is complex and a complete understanding of the underlying pathogenic mechanisms is lacking. This limited understanding of its pathogenesis is a barrier to drug discovery, and there is currently no effective therapy for AD. Thus, efforts toward drug discovery for AD are encouraged.

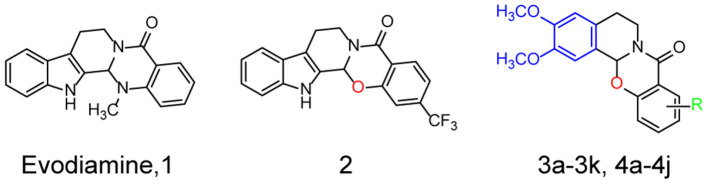

Recently, a number of natural compounds for improving AD symptoms were found, which suggested that natural compounds were potential resources for AD drug discovery (Wang et al., 2016). Authors of previous studies and of the present study reported that evodiamine (Evo, compound 1, Figure 1), a quinazolinone alkaloid isolated from the fruit of Evodiae fructus, improves the pathological symptoms of AD by reducing acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity, inhibiting oxidative stress, and reducing neuroinflammation (Wang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2020; Chou and Yang, 2021). However, evodiamine (Evo) exhibits high cytotoxicity and poor bioactivity (Gavaraskar et al., 2015; Pang et al., 2020). In addition, its highly active derivatives are needed to investigate its mechanism of action. In an earlier study, we reported that the cytotoxicity of evodiamine could be reduced by replacing its nitromethyl group with an oxygen atom (2, Figure 1), thus opening the doors for further research and development of evodiamine derivatives (Pang et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Structures and the optimization strategies of evodiamine, 2, and the target compounds.

Herein, a series of evodiamine derivatives, compounds 3a−3k and 4a−4j, were designed and synthesized according to the strategy of heterocyclic substitution (Figure 1). 1,2-Dimethoxybenzene, a common structural segment in alkaloids, was used to substitute the indole ring. The oxygen atom of compound 2 was maintained and the introduction of an amide group (R) was investigated. The derivatives were screened by assessing their cytotoxicity against human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) and human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells and their anti-H2O2 activity in SH-SY5Y cells. Compared to the other derivatives and evodiamine, compound 4c exhibited the lowest cytotoxicity and highest anti-H2O2 activity. In addition, compound 4c prevented Aβ oligomer- and H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in vitro and improved AD pathology and cognitive behavior in AD mice. Compound 4c compensated for the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway dysfunction in AD mice, providing insights into the molecular mechanisms of AD treatment.

Materials and methods

Chemistry

An Agilent Technologies LC/MSD TOF instrument was used to record the high-resolution mass spectra. Varian Mercury 400 and 100 MHz spectrometers were used to record the 1H and 13C NMR spectra. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Shimadzu LC-20A) with a reverse-phase C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 mm, Shim-pack VP-ODS) was used to determine the purity of the target compounds (all above 95%). The detailed chemical data, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and the high-resolution mass spectra are provided in the Supplementary material.

Cell culture

SH-SY5Y and HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, 11965-92, Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10099-141C, Gibco) and 1% antibiotic penicillin-streptomycin solution (15070063, Gibco) in an incubator at 5% CO2 and 37°C.

Animal treatments

APPswe/PS1ΔE9 double-transgenic mice (APP/PS1mice) and APPswe/PS1M146V/TauP301L triple-transgenic mice (3 x Tg mice) with a C57BL/6J genetic background were bred in our laboratory (Yuan et al., 2011). The APP/PS1 mice exhibit typical senile plaques at 4.5 months, while the 3 x Tg mice develop typical p-Tau accumulation at 8 months (Billings et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2011; Huber et al., 2018). As described previously (Fang et al., 2019), we chose APP/PS1 mice to explore Aβ pathology and 3 x Tg mice to investigate Tau pathology. The mice experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Peking Union Medical College (Approval no. MYW19006).

Male and female 3 x Tg mice and C57BL/6J mice (WT) aged 9 months were randomly assigned to six groups of 12 animals. The WT mice were treated with saline (WT group) or 4c (200 μg/kg, WT-4c-H group) and the 3 x Tg mice were treated with saline (3 x Tg group), 4c (20 μg/kg, 4c-L group; 200 μg/kg, 4c-H group), or evodiamine (200 μg/kg, Evo group) via intraperitoneal injection (IP) every 2 days for 4 weeks. C57BL/6J mice and APP/PS1 mice aged 7 months were assigned to five groups of eight animals. The WT mice were treated with saline (WT group) or 4c (200 μg/kg, WT-4c-H group) and the APP/PS1 mice were treated with saline (APP/PS1 group), 4c (200 μg/kg, 4c-H group), or evodiamine (200 μg/kg, Evo group) by IP every 2 days for 4 weeks.

Determination of the lethal dose 50 (LD50)

SH-SY5Y cells and HepaG2 cells were inoculated into 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells/100 μl/well in six replicates and incubated for 24 h to allow them to adhere to the plate bottom. The cells were co-incubated with different concentrations of evodiamine derivatives (0, 10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 1, 10, 50, and 100 μg/ml) and different concentrations of evodiamine (0, 10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 1, 5, 10, and 50 μg/ml) for 24 h. Cell viability was analyzed using a cell counting kit-8 (CCK8) assay kit (CK04-500, Dojindo). The LD50 was estimated from the compound concentration that resulted in 50% viability.

Evaluation of the effect of evodiamine derivatives on H2O2 resistance

SH-SY5Y cells were inoculated into plates and incubated for 24 h to allow them to adhere to the plate bottom. The cells were then co-incubated with 75 μM H2O2 and an evodiamine derivative at a dose of 10−2, 10−1, or 1 μg/ml or 4c at a dose of 10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, or 1 μg/ml for 24 h and cell viability was analyzed.

Determination of cell death by calcein-AM/PI double staining

SH-SY5Y cells were inoculated into plates and incubated for 24 h to allow them to adhere to the plate bottom. The cells were then co-incubated with 75 μM H2O2 and 4c or Evo at a dose of 10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 0, or 1 μg/ml for 24 h. Next, calcein-AM/PI double staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (C542, Dojindo). The staining solution containing 1 μM calcein-AM and 0.5 μM PI was added to the wells of the plate and incubated for 15 min in an incubator. Finally, the number of living (green) and dead cells (red) were captured using a microscope (BX53; Olympus Corporation).

Real-time cell status assay

Aβ1–42 oligomers (AβOs) were obtained from Chinapeptides (04010011526, Chinapeptides). The synthesized monomeric peptides were dissolved in cooled 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) and incubated for 60 min at room temperature, followed by placing the peptide–HFIP solution on ice for 10 min and drying at room temperature. The peptide was added to DMSO to form a peptide film, diluted with Ham's F12-free medium to a final concentration of 50 μM, incubated for 24 h at 4°C, and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, with the supernatant being the Aβ oligomers. Finally, it is freeze-dried to a powder. As previously reported (Rodriguez-Garcia et al., 2021), the effects of 4c and evodiamine on AβOs cytotoxicity were detected by a real-time cell analyzer (RTCA-DP, ACEA Biosciences Inc, USA). SH-SY5Y cells were inoculated in E-plates (ACEABiosciences, 00300600890) and cultured for 3 h to allow cell attachment. The medium was then replaced with another medium containing 25 μM AβO alone, 25 μM AβOs with 0.1 μg/ml 4c, or 25 μM AβOs with 0.1 μg/ml evodiamine, respectively. The plates were placed in a real-time cell analyzer under a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 200 h. The cell index (CI) was determined by measuring the cell-to-electrode responses of the cells attached to the E-plates, which represented the cell viability status and cell number. The CI was monitored every 15 min during the 200-h experiment time.

Western blotting

To detect AβOs by western blotting, brain tissues were homogenized in a TBS extraction buffer comprising protease inhibitor (87785, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 mM NaF, 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (78420, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaVO3, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF, 36978, ThermoFisher Scientific) as reported by Zhang et al. (2017).

Western blotting was performed as previously described (Pang et al., 2021). The brain tissue homogenates were separated by SDS–PAGE and electroeluted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Immobilon NC; Millipore). The membranes were initially incubated with primary antibodies overnight (Table 1) followed by HRP-linked secondary antibodies. Finally, the proteins were visualized and analyzed. The antibodies and working dilutions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in this study.

| Primary antibodies | Source | Catalog no. | WB | IHC | IF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6E10 | Biolegend | 803001 | 1:500 | — | 1:150 |

| IBA1 | CST | 17198 | — | — | 1:150 |

| GFAP | Abcam | ab7260 | — | — | 1:200 |

| T231 (p-TAU at Thr231) | Abcam | ab151559 | — | 1:200 | — |

| T181 (p-TAU at Thr181) | Abcam | ab75679 | 1:500 | 1:200 | 1:100 |

| AT8 (p-TAU at Ser202/Thr205) | Thermo Fisher | MN1020 | 1:500 | — | 1:100 |

| p-PI3K | CST | 4228 | 1:500 | — | — |

| PI3K | CST | 4292S | 1:500 | — | — |

| p-AKT (Ser473) | CST | 9271 | 1:1,000 | — | — |

| AKT | CST | 4691s | 1:1000 | — | — |

| p-GSK3α/β (Ser21/9) | CST | 9331s | 1:1,000 | — | — |

| GSK3β | CST | 9315 | 1:1,000 | — | — |

| GAPDH | Abcam | ab201822 | 1:10,000 | — | — |

| TAU5 | Millipore | 577801 | 1:500 | — | — |

| 488 goat anti-mouse IgG | Invitrogen | A11029 | — | — | 1:200 |

| 555 goat anti-rabbit IgG | Invitrogen | A21429 | — | — | 1:200 |

| HRP-anti-mouse IgG | ZSGB-BIO | PV9002 | — | 1:20 | — |

| HRP-t anti-rabbit-IgG | ZSGB-BIO | PV9001 | — | 1:20 | — |

Pathological assay

Mouse brain tissues were fixed, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin and the sections were dewaxed according to a standard procedure. The sections were blocked in 1% BSA for 30 min and then incubated with primary antibodies (Table 1). Then, the sections were applied to immunofluorescent or immunohistochemical staining. For immunofluorescent staining, the sections were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies (Table 1) in a dark box for 1 h, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and mounted with DAPI buffer (ZLI-9557, ZSGB BIO). For immunohistochemical staining, the sections were incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies, washed with PBS, visualized with DAB peroxidase substrate, and mounted in neutral gum. The sections were then scanned under a digital slide scanner (Pannoramic250 FLASH, 3DHISTECH). Image quantification was performed using ImageJ as previously described (Luo et al., 2020).

Cognitive behavior analysis

After 1 month of treatment, the mice were subjected to the Y maze test according to the reported methods (Spangenberg et al., 2019). One mouse was placed in the Y maze for 5 min and its activity was recorded and analyzed by an Ethovision XT system (Noldus Ltd). The percentage of alternations among the three arms was calculated as actual alternations/maximum alternations × 100.

After the Y maze test, the mice were subjected to the Morris water maze (MWM) test according to the reported methods (Pang et al., 2020). For five consecutive days, the mice were trained to look for the platform. The latency in looking for the hidden platform was recorded. On day 6, the mice were placed in a heterolateral quadrant and allowed to explore freely for 60 s in the absence of the platform. During this time, the number of crossings to the previous platform region and target quadrant occupancy were recorded. A video-tracking system was used for recording and analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (15596018, Invitrogen) and used as the template for first-strand cDNA synthesis using a reverse transcription kit (RR047A, TaKaRa). Next, the cDNA was used for qRT-PCR using a QuanStudio™3 Real-Time PCR instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with SYBR Green real-time PCR kits (RR820A, TaKaRa). We detected the mRNA expressions of Adam10, Snca, Caspase7, Ide, and Aph-1b; Gapdh expression was used for normalization. The primers for qRT-PCR are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Gene | Forward sequences | Reverse sequences |

|---|---|---|

| Adam10 | 5′-CTCGTCGGGACCCAGC-3′ | 5′-AAAGGATTTCCATACTGACCTCCC-3′ |

| Snca | 5′-AGCCTGTGCATCTATCTGCG-3′ | 5′-TTGCTCCACACTTTCCGACTT-3′ |

| Caspase7 | 5′-CCTCTGGGACTTTTGCTTTCAG-3′ | 5′-TCATCGGTCATCGTTCCCA-3′ |

| Ide | 5′-GACCACGAGGCTATACGTCC-3′ | 5′-ATTGCCACCCGCACATTTTC-3′ |

| Aph-1b | 5′-TGTTGGCCTATGTTTCTGGCT-3′ | 5′-CAAAGAACACAACGCCCCAG-3′ |

| Gapdh | 5′-GGGTTCCTATAAATACGGACTGC-3 | 5′- CAATACGGCCAAATCCGTTCA-3 |

RNA sequencing analysis

Mice treated with or without 4c were sacrificed and the hippocampal tissues were dissected. RNA isolation, library preparation, Illumina RNA sequencing, and data processing were performed as previously described (Lu et al., 2018). Genes with RPKM <1 were excluded and genes with a |fold change| >1 and a P-value of < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the data by two-tailed unpaired t-tests and a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. A P-value of < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results

Synthesis of evodiamine derivatives

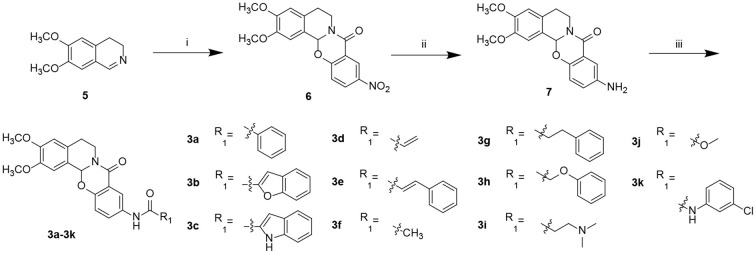

Starting from 6,7-dimethoxy-3,4-dihydroisoquinoline (5, Scheme 1), 5-nitrosalicylic acid was treated with 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride in dichloromethane to give intermediate 6 (Yang et al., 2016). Reduction of 6 by 10% Pd/C under hydrogen resulted in 7. Target compounds 3a–k were furnished by the condensation of 7 with different acids, acyl chlorides, and isocyanates. The synthesis route for exchanging amides to obtain compounds 4a–j is depicted in Scheme 2. Intermediate 8 was prepared from dihydroisoquinoline 5 and 2-hydroxy-5-(methoxycarbonyl) benzoic acid, followed by hydrolysis to afford 9. Finally, compounds 4a–j were furnished by the condensation of acid 9 and different amines.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of target compounds 3a–k. Reagents and conditions: (i) 5-nitrosalicylic acid, 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride, dichloromethane, rt; (ii) 10% Pd/C, hydrogen, methanol, and rt; (iii) 2-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate, N,N-diisopropylethylamine, dichloromethane, and rt.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of target compounds 4a–j. Reagents and conditions: (i) 2-hydroxy-5-(methoxycarbonyl) benzoic acid, 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride, dichloromethane, and rt; (ii) LiOH, methanol: H2O, and rt; and (iii) 2-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate, N,N-diisopropylethylamine, dichloromethane, and rt.

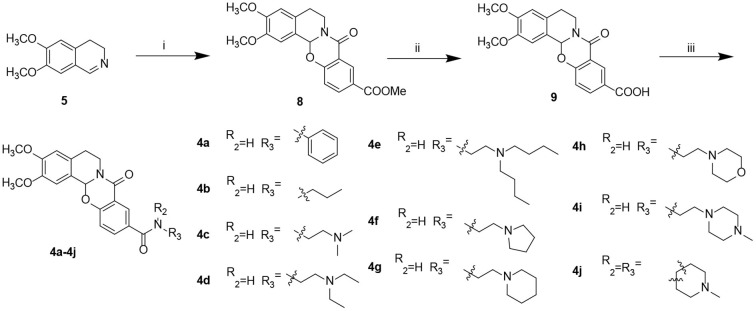

Selection of evodiamine derivatives based on cytotoxicity and anti-H2O2 activity

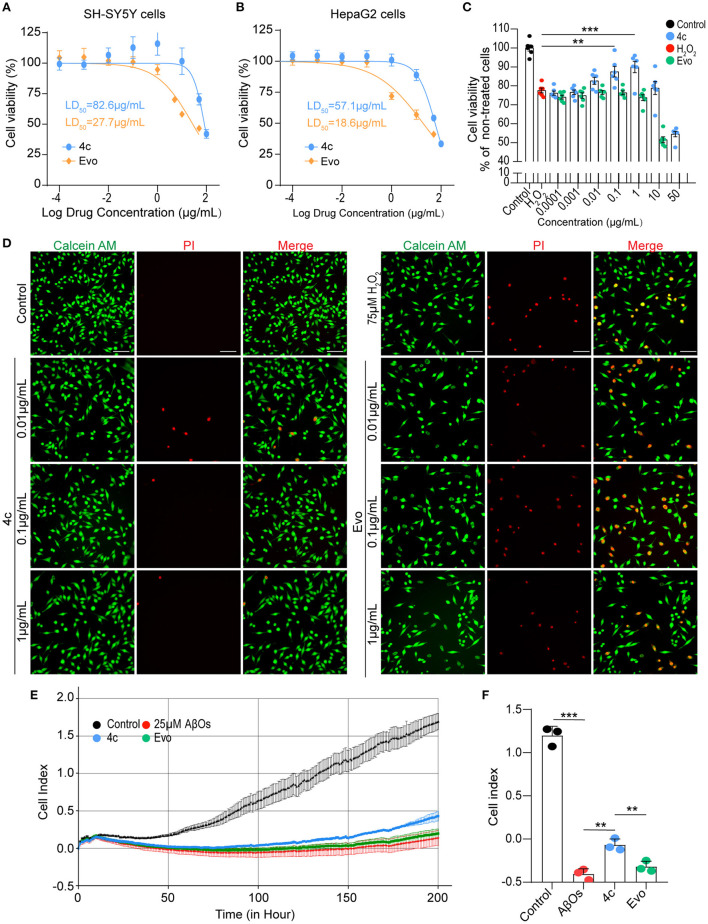

To identify Evo derivatives with lower cytotoxicity and higher anti-H2O2 activity, the cytotoxicity of the derivatives and Evo in SH-SY5Y and HepaG2 cells was evaluated by measuring cell viability. Although several compounds exhibited lower cytotoxicity than Evo and the other derivatives (Figures 2A, B, n = 6), compounds 3d, 3g, and 4c significantly promoted SH-SY5Y cell proliferation (Figure 2A, n = 6; **P < 0.01). Furthermore, the anti-H2O2 activity of the derivatives and Evo in SH-SY5Y cells was assessed by measuring cell viability in the presence of H2O2. Compounds 3b, 3d, 3f, 4b, 4c, 4d, and 4g had higher anti-H2O2 activity than Evo and the other derivatives (Figure 2C, n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). Among all derivatives, 4c had the lowest cytotoxicity, the highest anti-H2O2 activity, and the greatest neuronal cell-proliferation-promoting effect and hence was selected for further study.

Figure 2.

Screening for the cytotoxicity and the anti-H2O2 activity of the evodiamine derivatives. (A, B) SH-SY5Y cells and HepaG2 cells were treated with Evo and Evo derivatives at concentrations of 1, 10, and 50 μg/ml for 24 h. The cytotoxicity of Evo and its derivatives was subsequently assessed by detecting cell viability using CCK8. (C) SH-SY5Y cells were co-incubated with 75 μM H2O2 and different concentrations of Evo derivatives (10−3, 10−2, and 10−1 μg/ml) for 24 h, and cell viability was quantified using CCK8. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

Compound 4c has a higher LD50 and activity against AβOs than evodiamine in vitro

The median lethal doses (LD50) of 4c and Evo in SH-SY5Y and HepaG2 cells were comparatively analyzed. The LD50 of 4c and Evo were 82.6 and 27.7 μg/ml, respectively, in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 3A) and 57.1 and 18.6 μg/ml, respectively, in HepaG2 cells (Figure 3B). Thus, the LD50 of 4c in SH-SY5Y and HepaG2 cells was approximately two-fold higher than that of Evo. Next, the effective concentration of compound 4c against H2O2 in SH-SY5Y cells was determined by measuring the viability of cells treated with 10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 1, or 10, or 50μg/ml 4c. The minimal and optimum effective concentrations of compound 4c against H2O2 in SH-SY5Y cells were 0.01 and 1 μg/ml, respectively (Figure 3C). The induction of cell death by H2O2 was assessed by calcein-AM/PI double staining, which showed that 4c protected SH-SY5Y cells from cell death at concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μg/ml, whereas Evo had no apparent protective effect against cell death (Figure 3D). Furthermore, AβO cytotoxicity was evaluated using a real-time cell analyzer that monitors cell proliferation and viability status in real time. The results showed that compound 4c significantly reduced the AβOs cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells (Figures 3E, F, n = 3; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Determination of the LD50 of 4c and its effects against H2O2 and AβOs. (A, B) The viability of SH-SY5Y and HepaG2 cells was determined by CCK8 after 24 h of exposure to different concentrations of 4c (10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 1, 10, 50, and 100 μg/ml) and Evo (10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 1, 5, 10, and 50 μg/ml). The LD50 values of 4c and Evo were estimated from the concentrations that resulted in 50% cell viability compared with the vehicle control. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 6. (C) SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with 75 μM H2O2 alone or co-incubated with 75 μM H2O2 and different concentrations of 4c or Evo (10−4, 10−3, 10−2, 10−1, 1, 10, and 50 μg/ml) for 24 h. Cell viability was subsequently quantified using CCK8 and normalized to the cell viability of the vehicle control. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 6. (D) SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with 75 μM H2O2 alone and co-incubated with 75 μM H2O2 and different concentrations of 4c or Evo (10−2, 10−1, and 1 μg/ml) for 24 h. The cells were then stained with calcein-AM/PI, and living and dead cells were detected by green or red fluorescence, respectively. n = 3, Scale bar = 100 μm. (E) SH-SY5Y cells were co-incubated with 25 μM AβOs without or with 0.1 μg/ml 4c or Evo in a real-time cell analyzer for 200 h. The cell index, which represents the real-time cell status, was monitored by the analyzer and analyzed by the RTCA software. (F) The cell index of 4c at 200 h was significantly higher than that of Evo. n = 3; **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

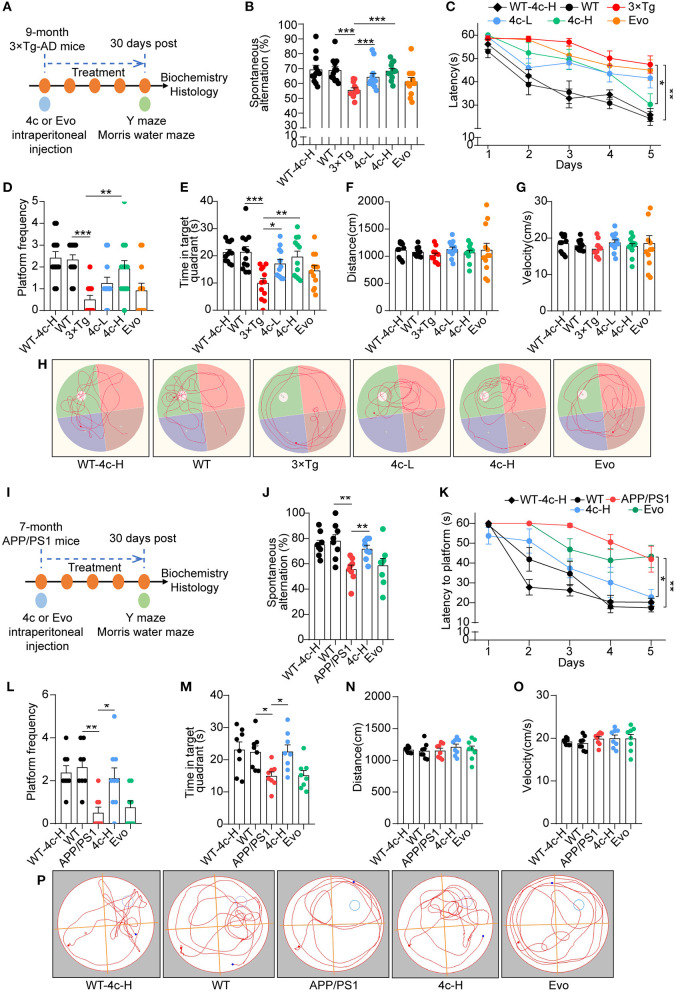

Compound 4c improves working memory and spatial memory in 3 x Tg mice

We evaluated the effects of compound 4c on cognitive decline and Tau-dependent pathology in 3 x Tg mice, which develop more typical Tau phosphorylation than APP/PS1 AD mice (Billings et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2011; Huber et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2019). Nine-month-old 3 x Tg mice were treated with or without 4c or Evo for 4 weeks (Figure 4A). The Y-maze tests showed that compound 4c significantly improved the working memory of 3 x Tg mice in a dose-dependent manner, with increases in the number of spontaneous alternations of 15.6 and 23.1% in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4B, n = 12, ***P < 0.001). In the MWM test, treatment with 20 or 200 μg/kg showed that compound 4c significantly decreased the latent time before exploring the hidden platform, increased the number of platform crossings by 150 and 283.4%, respectively, and increased the target quadrant duration by 71.3 and 97.2%, respectively (Figures 4C–E, n = 12; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). These results showed that compound 4c significantly improved the spatial memory of 3 x Tg mice in a dose-dependent manner. In 3 x Tg AD mice, Evo showed a tendency to improve the working and spatial memories (Figures 4B, E, n = 12). Compound 4c did not alter the cognitive behavior of WT mice in the Y-maze and MWM tests (Figures 4B, E, n = 12), and neither 4c nor Evo affected the swimming speed and distance of the WT and AD mice (Figures 4F, G, n = 12).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the cognitive behavior of 3 x Tg and APP/PS1 AD mice treated with 4c. (A) Schematic diagram of the experimental design for treating 3 x Tg-AD mice with 4c. Six groups of mice were treated every 2 days for 4 weeks: WT with 200 μg/kg 4c (WT-4c-H), WT with vehicle (WT), 3 x Tg with vehicle (3 x Tg), 3 x Tg with 20 μg/kg 4c (4c-L), 3 x Tg with 200 μg/kg 4c (4c-H), and 3 x Tg with 200 μg/kg Evo (Evo). (B) After treatment, all mice were subjected to the Y maze test and the percentage of alternations was calculated. (C) After the Y maze test, the mice were subjected to the MWM test and the latency to find the hidden platform during the 5-day training period was comparatively analyzed. (D, E) The number of platform crossings and time in the target quadrant during the probe trial on day 6 were recorded. (F–H) The distance, velocity, and track examples of the mice in the MWM test were recorded during the probe trial on day 6. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 12; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. (I) Schematic diagram of the experimental design for treating APP/PS1 AD mice with 4c. Five groups of mice were treated every 2 days for 1 month: WT with 200 μg/kg 4c (WT-4c-H), WT with vehicle (WT), APP/PS1 with vehicle (APP/PS1), APP/PS1 with 200 μg/kg 4c (4c-H), and APP/PS1 with 200 μg/kg Evo (Evo). (J) After treatment, working memory was assessed by performing the Y maze test and analyzing the percentage of alternations. (K–M) The treated mice were subjected to the MWM test and the latency to find the hidden platform during the 5-day training period was recorded. On day 6, the spatial memory of the mice was evaluated by monitoring the number of platform crossings and time in the target quadrant. (N–P) The distance, velocity, and track examples of the mice in the MWM were recorded on day 6. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 10; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

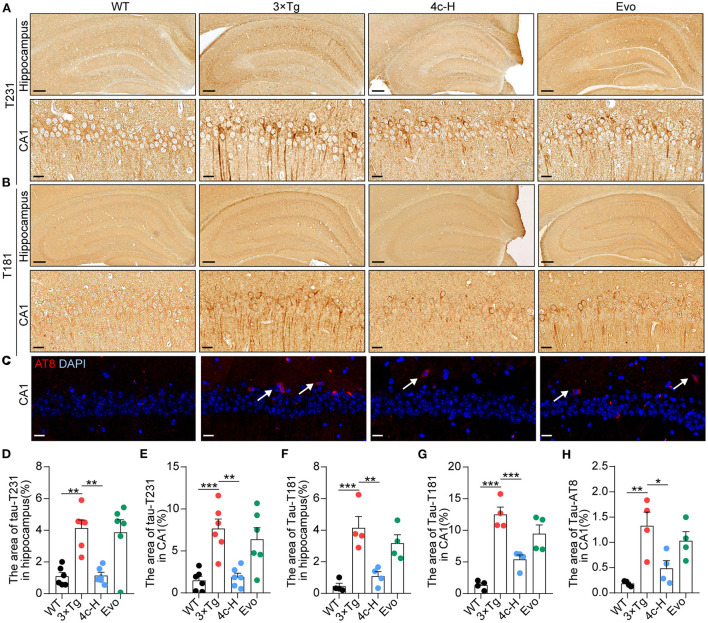

Compound 4c inhibits Tau hyperphosphorylation in 3 x Tg mice

In patients and mice with AD, Ser202/Thr205 (AT8), Thr231 (T231), and Thr181 (T181) of Tau are commonly phosphorylated sites (Hanger et al., 2007; Spillantini and Goedert, 2013; Fang et al., 2019). After the cognitive behavior analysis, the WT and 3 x Tg mice treated with vehicle, 200 μg/kg 4c, or 200 μg/kg Evo were sacrificed, and Tau phosphorylation in hippocampal tissues was assessed by immunohistological staining. Compared with 3 x Tg mice treated with vehicle, compound 4c reduced Tau hyperphosphorylation by 72.4 and 75.3% at T231 and 73.8 and 56.9% at T181 in the hippocampus and the hippocampal CA1 regions, respectively, and by 63.5% at AT8 in the hippocampal CA1 region in 3 x Tg mice (Figures 5A–H, n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). Compared with the 3 x Tg mice treated with vehicle, the 3 x Tg mice treated with Evo exhibited a mild reduction in Tau hyperphosphorylation (Figures 5D–H, n = 6).

Figure 5.

Determination of Tau phosphorylation in brain tissues. After the MWM test, mice from the WT, 3 x Tg, 4c-H, and Evo groups were sacrificed, and brain tissues were sampled for histological staining. (A, B) Tau phosphorylation was detected via immunohistochemical staining with T231 and T181 antibodies in the mouse hippocampus (scale bar = 200 μm) and hippocampal CA1 region (scale bar = 20 μm). (C) Tau phosphorylation was detected using immunofluorescent staining with the AT8 antibody in the mouse hippocampal CA1 region (white arrowheads indicate AT8-positive cells, scale bar = 20 μm). (D–G) Tau phosphorylation as detected using T231 and T181 antibodies in the hippocampus and the hippocampal CA1 region was quantified by the density of staining using ImageJ. (H) Tau phosphorylation as detected by the AT8 antibody was quantified by red fluorescence. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Compound 4c improves cognitive decline in APP/PS1 mice

The effects of 4c and Evo on cognitive decline were assessed in APP/PS1 mice that express the APPswe and PS1ΔE9 mutant genes and develop a more typical amyloid-dependent pathology than 3 × Tg AD mice (Billings et al., 2005; Tahara et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2011; Huber et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2019). Seven-month-old APP/PS1 mice were treated with 200 μg/kg 4c or Evo or vehicle for 4 weeks (Figure 4I). After treatment, Y maze and MWM tests were performed. In the Y maze test, 4c treatment increased spontaneous alternations by 29.0% compared with the vehicle group (Figure 4J, n = 8; **P < 0.01). In the MWM test, 4c treatment reduced the time to look for the hidden platform, increased the number of platform crossings by 322.2%, and increased the target quadrant duration by 50.3% compared with the vehicle group (Figures 4K–M, n = 8; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). In contrast, Evo did not improve the cognitive behavior of APP/PS1 mice in the Y-maze and MWM tests (Figures 4J–M, n = 8). Compared with WT mice, neither 4c nor Evo treatment altered the swimming speed and distance of APP/PS1 mice (Figures 4N–P).

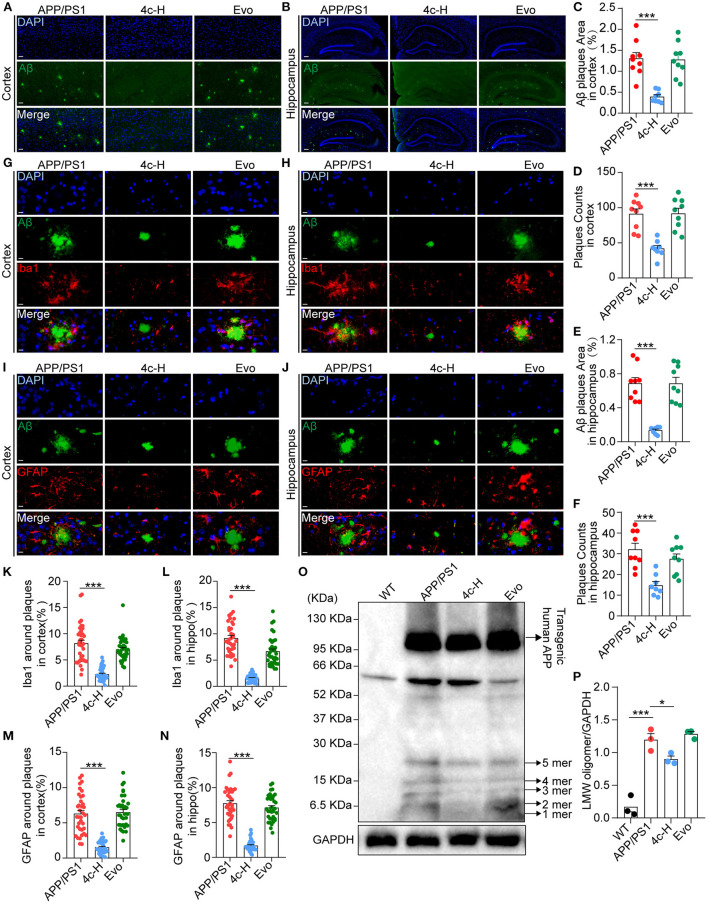

Compound 4c reduces amyloid accumulation and glial cell aggregation in APP/PS1 mice

After the Y-maze and MWM tests, amyloid accumulation and glial cell aggregation were assessed in the cortex and the hippocampus of the APP/PS1 mice treated with vehicle, 4c, or Evo. Immunofluorescent staining with an anti-6E10 antibody showed that, compared with the vehicle, 4c treatment significantly reduced the Aβ plaque number by 54.1 and 54.1% and the Aβ area by 80.4% and 70.0% in the hippocampus and the cortex, respectively (Figures 6A–F, n = 6; ***P < 0.001). Furthermore, western blotting with an anti-6E10 antibody indicated that 4c treatment significantly reduced the accumulation of AβOs in the brain by 24.8% compared with the vehicle (Figures 6O, P, n = 3; *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Observation of Aβ pathology in the brain in APP/PS1 mice. After the cognitive behavior evaluations, mice from the APP/PS1, 4c-H, and Evo groups were selectively sacrificed, and the paraffin sections of the brain were prepared by a standard pathological procedure. (A, B) Aβ in the cortex and hippocampus was observed by immunofluorescence staining with an anti-6E10 antibody (green) and counterstained with DAPI (scale bar = 200 μm). (C–F) The Aβ plaque area and plaque counts in the cortical and hippocampal regions were quantified by ImageJ (n = 9). (G, H, K, L) Microglia around Aβ plaques were observed by double immunofluorescence staining with anti-6E10 (green) and anti-Iba1 (red) antibodies in the cortex and hippocampus. The cell number of microglia around Aβ plaques was also counted (scale bar = 10 μm, n = 6). (I, J, M, N) The astrocytes around Aβ plaques were observed by double immunofluorescence staining with anti-6E10 (green) and anti-GFAP (red) antibodies in the cortex and the hippocampus, and the number of astrocytes around Aβ plaques was counted (scale bar = 10 μm, n = 6). (O, P) Low-molecular weight oligomers (LMW; 1–5 mers) of Aβ in brain tissues were detected by western blotting and quantified using ImageJ (n = 3). Data are represented as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001.

Amyloid β (Aβ) deposition in the brain is accompanied by gliosis in patients and mice with AD (Münch et al., 2003; Frost and Li, 2017), and Aβ-dependent gliosis and inflammation reflect the degree of injury in AD (Kim et al., 2015). Microglia and astrocytes in the brains of APP/PS1 mice were detected by immunofluorescent staining with anti-6E10, anti-Iba1, and anti-GFAP antibodies. Compared with the vehicle, 4c significantly reduced microglial and astrocyte aggregation around Aβ plaques in the hippocampus and the cortex (Figures 6G–N, n = 6; ***P < 0.001). In contrast, Evo did not reduce amyloid accumulation or glial aggregation compared with the vehicle (Figures 6A–N, n = 6).

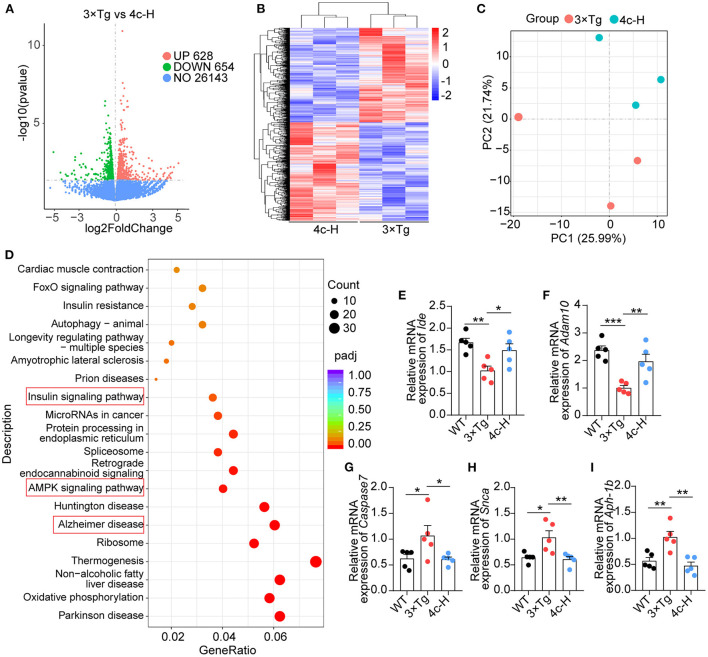

Compound 4c modulates the expression of AD-related genes in 3 x Tg mice

The effects of 4c on gene expression were investigated by performing an RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of the hippocampal tissues of three mice randomly selected from the 200 μg/kg 4c treatment group and the vehicle group. The two groups were compared to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), and 628 upregulated and 654 downregulated DEGs were identified in the 4c group (Figure 7A). The results of clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) showed that the 4c group and the vehicle group were distinct (Figures 7B, C). KEGG analysis showed that the DEGs were enriched in genes related to AD, insulin signaling, AMPK signaling, and oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 7D). The AD-related genes identified by RNA-seq were further confirmed by RT-qPCR, which verified the downregulation of Ide and Adam10 expression and the upregulation of Caspase7, Snca, and Aph-1b expression in 3 x Tg mice compared with WT mice. Treatment of 3 x Tg mice with 4c completely recovered these changes in gene expression (Figures 7E–I, n = 5; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001).

Figure 7.

Transcriptome analysis of hippocampal tissues. Hippocampal tissues from 3 x Tg AD mice treated without or with 4c (i.e., 3 x Tg and 4c-H groups) were selected for transcriptome analysis. (A) Volcano plots of DEGs between the 3 x Tg and 4c-H groups. DEGs were identified by comparing 3 x Tg and 4c-H mice using fold change >1 and P-value <0.05 as the cut-off (n = 3). (B, C) Hierarchical clustering and PCA analysis of the 3 x Tg and 4c-H groups were performed using the normalized RNA-seq read counts. (D) KEGG pathways enriched in the 628 and 654 genes that were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in 4c-H mice compared with the 3 x Tg mice (n = 3). (E–I) AD-related genes (Ide, Adam10, Caspase7, Snca, and Aph-1b) were detected by RT-qPCR and compared among the WT, 3 x Tg, and 4c-H groups (n = 5). Data are represented as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

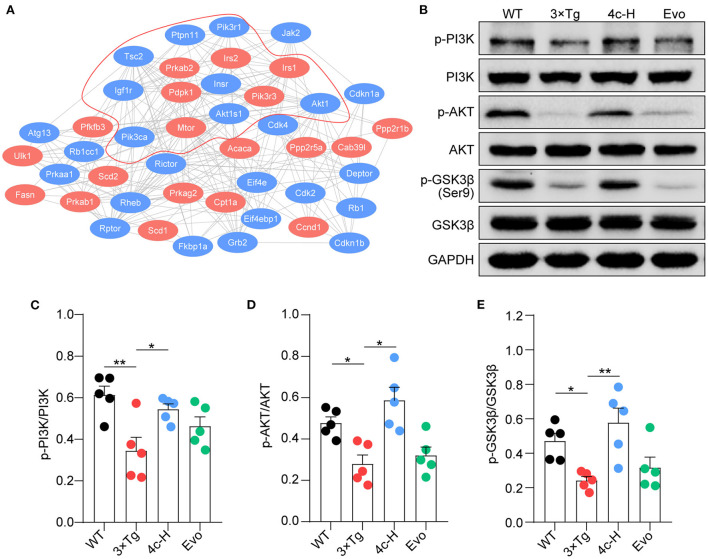

Compound 4c compensates the dysfunction of PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling in 3 x Tg mice

The insulin signaling pathway genes that were enriched in the KEGG analysis were used as seed genes for protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis. The PPI network constructed using STRING included 19 seed proteins and 25 interacting proteins in the insulin signaling pathway (Figure 8A) and suggested that compound 4c may modulate the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway. Confirming the involvement of the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway, we found that PI3K and AKT phosphorylation were inhibited and that GSK3β was activated in 3 × Tg mice treated with vehicle compared with WT mice (Figures 8B–E, n = 5; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). Compared with the vehicle treatment, 4c treatment increased PI3K and AKT phosphorylation and inhibited GSK3β activation in 3 x Tg mice (Figures 8B–E, n = 5; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

Figure 8.

Compound 4c activates the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway. (A) Protein–protein interaction network involving the AMPK signaling pathway. Compound 4c affected the 19 proteins shown in red, and 25 interacting proteins identified by the STRING search are shown in blue. (B) Effects of 4c treatment on p-PI3K, p-AKT, and p-GSK-3β protein expression in 3 x Tg mice. (C–E) Relative protein abundance of p-PI3K/PI3K, p-AKT/AKT, and p-GSK3β/GSK3β in each group. Data are the mean ± SEM, n = 5; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 as indicated in the figure.

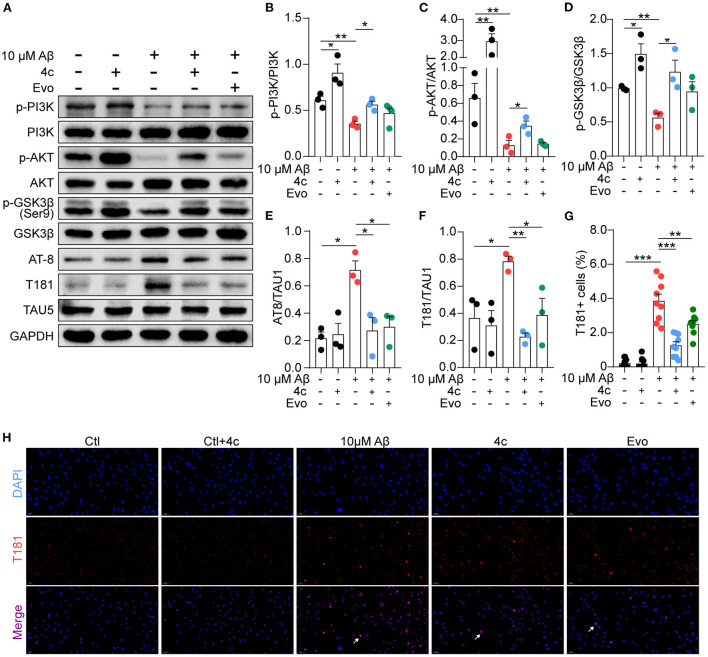

Compound 4c recovers PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/Tau dysfunction caused by Aβ in vitro

Aβ stimulation induces PI3K/AKT/GSK3β dysfunction and results in Tau phosphorylation by regulating the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway (Jeon et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2019). Consequently, the effect of 4c on this signaling pathway was examined in Aβ-treated SH-SY5Y cells. Aβ treatment reduced PI3K and AKT phosphorylation and increased GSK3β activation in SH-SY5Y cells (Figures 9A–D, n = 3; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01), resulting in Tau phosphorylation at AT-8 and T181 (Figures 9A, E, F, n = 3; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). Treatment with 4c dramatically reversed PI3K/AKT/GSK3β dysfunction and Tau phosphorylation induced by Aβ (Figures 9A–F, n = 3; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). The effect of Evo on Tau phosphorylation was smaller than that of 4c. The ameliorative effect of 4c on Tau phosphorylation was further confirmed by an immunofluorescence assay (Figures 9G, H, n = 3; ***P < 0.001).

Figure 9.

Determination of PI3K/AKT/GSK3β and Tau phosphorylation in vitro. A Tau phosphorylation cell model was established by treating SH-SY5Y cells with 10 μM Aβ1-42, and the cells were treated without or with 4c (0.1 μg/ml) or Evo (0.1 μg/ml) for 24 h. (A) The phosphorylation of p-PI3K, p-AKT, p-GSK-3β, and Tau in SH-SY5Y cells was detected by western blot using antibodies recognizing AT-8, T181, and Tau5 (n = 3). (B–F) The phosphorylation ratios compared with total protein were estimated by ImageJ (n = 3). (G, H) Tau phosphorylation was detected by immunofluorescent staining with anti-T181 antibody (n = 9 fields). Data are represented as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

We previously demonstrated that Evo improves AD phenotypes in a mouse model (Yuan et al., 2011). However, Evo exhibits side effects such as a reduction in hepatic cell apoptosis and impairment of the cardiovascular system (Yang et al., 2017). To reduce this cytotoxicity, we synthesized several evodiamine derivatives, compounds 3a−3k and 4a−4j, via heterocyclic substitution using 1,2-dimethoxybenzene to substitute the indole ring. The introduction of amide groups while maintaining the oxygen atom was also investigated. Structurally, compounds 3a−3k and 4a−4j could be considered bioisosteres. Supporting our design strategy, the amide compounds containing the amine group (3i and 4c–i) displayed higher activities against H2O2 and AβOs in vitro with the exception of the double-substituted compound 4j. Compounds 3i, 4c, and 4c displayed lower toxicity than Evo. In particular, the LD50 of 4c in SHSY-5Y and HepaG2 cells was three-fold higher than that of Evo (Figure 2). Compound 4c also exhibited a lower effective dosage for reducing H2O2 cytotoxicity (Figure 2).

Based on these results, 4c was further evaluated in 3 x Tg mice and APP/PS1 mice, which present typical Tau pathology and amyloid-dependent pathology, respectively (Billings et al., 2005; Tahara et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2011; Huber et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2019). Treatment with 4c significantly improved cognitive behavior disorder in both 3 x Tg mice and APP/PS1 mice, and the effective dose of 4c in APP/PS1 mice was 500-fold lower than that of Evo described previously (Yuan et al., 2011) (Figure 4). In addition, treatment of 3 x Tg mice with 4c significantly reduced the hyperphosphorylation of Tau at Ser202/Thr205, Thr231, and Thr181, the common sites of hyperphosphorylation in AD patients and AD mice (Hanger et al., 2007; Spillantini and Goedert, 2013; Fang et al., 2019) (Figure 5). In APP/PS1 mice, 4c treatment significantly reduced the number of senile plaques and amyloid accumulation in the brain and glial aggregation around the plaques (Figure 6), indicating improvements in Aβ-dependent gliosis and neuroinflammation (Kim et al., 2015).

Furthermore, the RNA-seq analysis showed that genes related to AD, insulin signaling, AMPK signaling, and oxidative phosphorylation were enriched in the hippocampal tissues of 3 x Tg mice treated with 4c (Figure 7). RT-qPCR confirmed that the changes in the expression of AD-related genes, including Ide, Adam10, Caspase7, Snca, and Aph-1b, in 3 x Tg mice were recovered by 4c treatment (Figure 7).

KEGG analysis of the RNA sequencing data indicated that the insulin signaling pathway play a role in the mechanism of action of 4c. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is an insulin signaling pathway that regulates glucose metabolism (Caruso et al., 2014). There is growing evidence that AD can be considered “type 3 diabetes” and that abnormal glucose metabolism is an important molecular event in the AD disease process (de la Monte and Wands, 2008; Sedzikowska and Szablewski, 2021). Interruption of the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway is a common event in the AD brain (de la Monte and Wands, 2008; Sedzikowska and Szablewski, 2021). The interruption of PI3K/AKT in AD may inhibit the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which is indirectly involved in amyloid accumulation (O' Neill, 2013; Cao et al., 2021; Querfurth and Lee, 2021). GSK3β is a typical downstream mediator that is inhibited by the PI3K/AKT pathway (Kitagishi et al., 2014). AKT dysfunction may cause abnormal GSK3β activation and Tau hyperphosphorylation in the brain of patients with AD (Takashima, 2006; Hanger et al., 2009; Querfurth and Lee, 2021). Overall, previous studies suggests that PI3K/AKT/GSK3β is a central signaling pathway in AD pathogenesis, namely, Aβ deposition and Tau hyperphosphorylation.

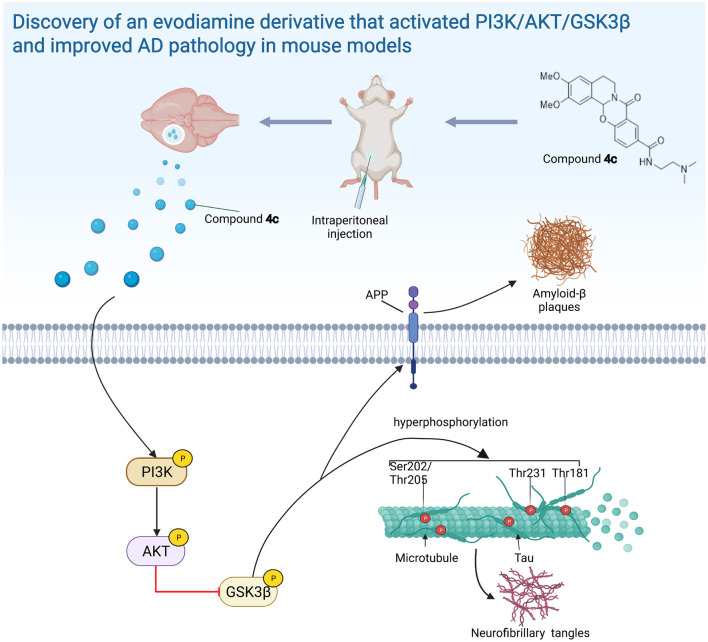

We found that 4c treatment recovered PI3K/AKT/GSK3β dysfunction in 3 x Tg mice (Figure 8). In SH-SY5Y cells, Aβ treatment reduced PI3K/AKT/GSK3β phosphorylation and induced Tau hyperphosphorylation, and 4c treatment ameliorated these effects of Aβ treatment (Figure 9). Our in vitro and in vivo results suggest that the recovery of PI3K/AKT/GSK3β dysfunction is an important mechanism by which 4c mitigates the pathological features of AD (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The evodiamine derivative 4c improves AD pathology via the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway. Compound 4c reversed the impairment of the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway in AD mice, thereby improving AD pathology (diagram was created with BioRender.com).

Conclusion

We successfully synthesized an Evo derivative, compound 4c, via heterocyclic substitution and amide introduction that had much lower cytotoxicity and higher activity. Treatment with compound 4c significantly improved the pathological features of AD in 3 x Tg mice and APP/PS1 mice and activated the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway, a central signaling pathway related to AD pathogenesis. Overall, our results indicate that 4c is a prospective compound for AD therapy based on the recovery of the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway dysfunction.

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra, accession numbers SRR21384922, SRR21384923, SRR21384924, SRR21384925, SRR21384926, and SRR21384927).

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Peking Union Medical College.

Author contributions

LiaZ, YY, and SPang designed the research plan. YY, SL, and HC prepared the compounds. SPang, WD, SG, NL, XG, SPan, and XZ prepared the AD mice models. SPang and ZL performed mice treatment and behavior tests. SPang, XQ, and LiZ performed tissue collection, histology analyses, and mechanism exploration. LiaZ and YY audited the experimental procedures. LiaZ, YY, and SPang analyzed the data, wrote and/or revised the manuscript, and had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF0710702), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31970508), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, 2021-I2M-1-034), and the Drug Innovation Major Project (2018ZX09711-001-005).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2022.1025066/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bertram L., Tanzi R. E. (2020). Genomic mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 30, 966–977. 10.1111/bpa.12882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings L. M., Oddo S., Green K. N., McGaugh J. L., LaFerla F. M. (2005). Intraneuronal abeta causes the onset of early Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron 45, 675–688. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacace R., Sleegers K., Van Broeckhoven C. (2016). Molecular genetics of early-onset Alzheimer's disease revisited. Alzheimers Dement. 12, 733–48. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B., Zeng M., Zhang Q., Zhang B., Cao Y., Wu Y., et al. (2021). Amentoflavone ameliorates memory deficits and abnormal autophagy in aβ(25-35)-induced mice by mtor signaling. Neurochem. Res. 46, 921–934. 10.1007/s11064-020-03223-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso M., Ma D., Msallaty Z., Lewis M., Seyoum B., Al-janabi W., et al. (2014). Increased interaction with insulin receptor substrate 1, a novel abnormality in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 63, 1933–1947. 10.2337/db13-1872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba-Falek O., Gottschalk W. K., Lutz M. W. (2018). The effects of the tomm40 poly-t alleles on Alzheimer's disease phenotypes. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 692–698. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C. H., Yang C. R. (2021). Neuroprotective studies of evodiamine in an okadaic acid-induced neurotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 5347. 10.3390/ijms22105347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Monte S.M., Wands J.R. (2008). Alzheimer's disease is type 3 diabetes-evidence reviewe d. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2, 1101–13. 10.1177/193229680800200619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Roeck A., Van Broeckhoven C., Sleegers K. (2019). The role of abca7 in Alzheimer's disease: evidence from genomics, transcriptomics and methylomics. Acta Neuropathol. 138, 201–220. 10.1007/s00401-019-01994-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang E. F., Hou Y., Palikaras K., Adriaanse B. A., Kerr J. S., Yang B., et al. (2019). Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 401–412. 10.1038/s41593-018-0332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z., Tang Y., Ying J., Tang C., Wang Q. (2020). Traditional chinese medicine for anti-Alzheimer's disease: berberine and evodiamine from evodia rutaecarpa. Chin. Med. 15, 82. 10.1186/s13020-020-00359-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost G. R., Li Y. M. (2017). The role of astrocytes in amyloid production and Alzheimer's disease. Open Biol. 7, 170228. 10.1098/rsob.170228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavaraskar K., Dhulap S., Hirwani R. R. (2015). Therapeutic and cosmetic applications of evodiamine and its derivatives–a patent review. Fitoterapia 106, 22–35. 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators . (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 88–106. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30403-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanger D. P., Anderton B. H., Noble W. (2009). Tau phosphorylation: the therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends Mol. Med. 15, 112–9. 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanger D. P., Byers H. L., Wray S., Leung K. Y., Saxton M. J., Seereeram A., et al. (2007). Novel phosphorylation sites in tau from Alzheimer brain support a role for casein kinase 1 in disease pathogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 23645–54. 10.1074/jbc.M703269200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C. M., Yee C., May T., Dhanala A., Mitchell C. S. (2018). Cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: amyloid-beta vs. tauopathy. J. Alzheimers Dis. 61, 265–281. 10.3233/JAD-170490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S., Park J. E., Lee J., Liu Q. F., Jeong H. J., Pak S. C., et al. (2015). Illite improves memory impairment and reduces aβ level in the tg-appswe/ps1de9 mouse model of Alzheimer?s disease through akt/creb and gsk-3β phosphorylation in the brain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 160, 69–77. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. Y., Kim H. V., Jo S., Lee C. J., Choi S. Y., Kim D. J., et al. (2015). Epps rescues hippocampus-dependent cognitive deficits in app/ps1mice by disaggregation of amyloid-β oligomers and plaques. Nat. Commun. 6, 8997. 10.1038/ncomms9997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H. (2018). Genetics of Alzheimer's disease. Dement. Neurocogn. Disord. 17, 131–136. 10.12779/dnd.2018.17.4.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagishi Y., Nakanishi A., Ogura Y., Matsuda S. (2014). Dietary regulation of pi3k/akt/gsk-3β pathway in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 6, 35. 10.1186/alzrt265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D., Wang J., Li J., Guan F., Zhang X., Dong W., et al. (2018). Meox1 accelerates myocardial hypertrophic decompensation through gata4. Cardiovasc. Res. 114, 300–311. 10.1093/cvr/cvx222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R., Su L. Y., Li G., Yang J., Liu Q., Yang L. X., et al. (2020). Activation of ppara-mediated autophagy reduces Alzheimer disease-like pathology and cognitive decline in a murine model. Autophagy 16, 52–69. 10.1080/15548627.2019.1596488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münch G., Apelt J., Rosemarie Kientsch E., Stahl P., Lüth H. J., Schliebs R., et al. (2003). Advanced glycation endproducts and pro-inflammatory cytokines in transgenic tg2576 mice with amyloid plaque pathology. J. Neurochem. 86, 283–9. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Y., Luo D., Yang M., Wang Y., Xiong L., Gao L., et al. (2017). A meta-analysis on the relationship of the pon genes and Alzheimer disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 30, 303–310. 10.1177/0891988717731825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O' Neill C. (2013). Pi3-kinase/akt/mtor signaling: impaired on/off switches in aging, cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Gerontol. 48, 647–653. 10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang S., Dong W., Liu N., Gao S., Li J., Zhang X., et al. (2021). Diallyl sulfide protects against dilated cardiomyopathy via inhibition of oxidative stress and apoptosis in mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 24, 852. 10.3892/mmr.2021.12492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang S., Sun C., Gao S., Yang Y., Pan X., Zhang L., et al. (2020). Evodiamine derivatives improve cognitive abilities in app(swe)/ps1(δe9) transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Animal Model Exp. Med. 3, 193–199. 10.1002/ame2.12126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querfurth H., Lee H. K. (2021). Mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mtor) complexes in neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 16, 44. 10.1186/s13024-021-00428-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Garcia A., Lynn R. C., Poussin M., Eiva M. A., Shaw L. C., O'Connor R. S., et al. (2021). Car-t cell-mediated depletion of immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages promotes endogenous antitumor immunity and augments adoptive immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 12, 877. 10.1038/s41467-021-20893-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedzikowska A., Szablewski L. (2021). Insulin and insulin resistance in Alzheimer's disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9987. 10.3390/ijms22189987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M. V. F., Loures C. M. G., Alves L. C. V., de Souza L. C., Borges K. B. G., Carvalho M. D. G. (2019). Alzheimer's disease: risk factors and potentially protective measures. J. Biomed. Sci. 26, 33. 10.1186/s12929-019-0524-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg E., Severson P. L., Hohsfield L. A., Crapser J., Zhang J., Burton E. A., et al. (2019). Sustained microglial depletion with csf1rinhibitor impairs parenchymal plaque development in an Alzheimer's disease model. Nat. Commun. 10, 3758. 10.1038/s41467-019-11674-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini M. G., Goedert M. (2013). Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 12, 609–22. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70090-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara K., Kim H. D., Jin J. J., Maxwell J. A., Li L., Fukuchi K., et al. (2006). Role of toll-like receptor signalling in abeta uptake and clearance. Brain 129, 3006–3019. 10.1093/brain/awl249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A. (2006). Gsk-3 is essential in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 9, 309–17. 10.3233/JAD-2006-9S335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Y., Liu J. G., Li H., Yang H. M. (2016). Pharmacological effects of active components of chinese herbal medicine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 44, 1525–1541. 10.1142/S0192415X16500853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Ma L., Li S., Cui K., Lei L., Ye Z., et al. (2017). Evaluation of the cardiotoxicity of evodiamine in vitro and in vivo. Molecules 22, 943. 10.3390/molecules22060943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhu C., Zhang M., Huang S., Lin J., Pan X., et al. (2016). Condensation of anthranilic acids with pyridines to furnish pyridoquinazolones via pyridine dearomatization. Chem. Commun. 52, 12869–12872. 10.1039/C6CC07365D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S. M., Gao K., Wang D. M., Quan X. Z., Liu J. N., Ma C. M., et al. (2011). Evodiamine improves congnitive abilities in samp8 and app(swe)/ps1(deltae9) transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 32, 295–302. 10.1038/aps.2010.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Sun C., Jin Y., Gao K., Shi X., Qiu W., et al. (2017). Dickkopf 3 (dkk3) improves amyloid-β pathology, cognitive dysfunction, and cerebral glucose metabolism in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 60, 733–746. 10.3233/JAD-161254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. X., Tian Y., Wang Z. T., Ma Y. H., Tan L., Yu J. T., et al. (2021). The epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease modifiable risk factors and prevention. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 8, 313–321. 10.14283/jpad.2021.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang J., Wang C., Li Z., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. (2018). Pharmacological basis for the use of evodiamine in Alzheimer's disease: antioxidation and antiapoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1527. 10.3390/ijms19051527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z. Y., Zhang Y. Q., Zhang Y. H., Wei X. Z., Wang H., Zhang M., et al. (2019). The protective underlying mechanisms of schisandrin on sh-sy5y cell model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 82, 1019–1026. 10.1080/15287394.2019.1684007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra, accession numbers SRR21384922, SRR21384923, SRR21384924, SRR21384925, SRR21384926, and SRR21384927).