Abstract

A candidate vaccine against botulinum neurotoxin serotype A (BoNT/A) was developed by using a Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus replicon vector. This vaccine vector is composed of a self-replicating RNA containing all of the VEE nonstructural genes and cis-acting elements and also a heterologous immunogen gene placed downstream of the subgenomic 26S promoter in place of the viral structural genes. In this study, the nontoxic 50-kDa carboxy-terminal fragment (HC) of the BoNT/A heavy chain was cloned into the replicon vector (HC-replicon). Cotransfection of BHK cells in vitro with the HC-replicon and two helper RNA molecules, the latter encoding all of the VEE structural proteins, resulted in the assembly and release of propagation-deficient, HC VEE replicon particles (HC-VRP). Cells infected with HC-VRP efficiently expressed this protein when analyzed by either immunofluorescence or by Western blot. To evaluate the immunogenicity of HC-VRP, mice were vaccinated with various doses of HC-VRP at different intervals. Mice inoculated subcutaneously with HC-VRP were protected from an intraperitoneal challenge of up to 100,000 50% lethal dose units of BoNT/A. Protection correlated directly with serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay titers to BoNT/A. The duration of the immunity achieved was tested at 6 months and at 1 year postvaccination, and mice challenged at these times remained refractory to challenge with BoNT/A.

Botulism is a disease resulting from the activity of botulinum neurotoxins (BoNT) produced by Clostridium botulinum on the transmission of neuromuscular stimuli (8, 22, 23). The blockage of stimuli produces neuromuscular weakness and flaccid paralysis, which can lead to respiratory failure and death. Food poisoning, infant botulism, and wound botulism are the three most common BoNT diseases affecting humans. The BoNT consists of two polypeptides bound by a disulfide bond, a heavy chain of about 100 kDa and a light chain of about 50 kDa. Seven different serotypes (A through G) of BoNT have been characterized. Previous research has shown that polyclonal antibodies to one serotype can block the effects of the homologous serotype but not of heterologous serotypes (20). The current human vaccine, which is administered under Investigational New Drug status to at-risk laboratory personnel, contains five of the seven serotypes (A to E) and is formulated as a toxoid. The toxoid vaccine is given as a primary series of three inoculations given at 0, 2, and 12 weeks, followed by a booster at 1 year. Since the vaccine is reactogenic in up to 20% of the recipients and contains only five of the seven serotypes, an improved vaccine would be preferable.

Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus is a member of the Alphavirus genus in the Togaviridae family. Alphaviruses contain a 42S single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome encoding four nonstructural proteins (providing the replicase and transcriptase function) and three structural proteins (capsid, E1, and E2). The nonstructural proteins are translated directly from the 42S genomic RNA. The structural proteins are translated from a subgenomic, 26S RNA that is transcribed from the full-length negative strand. The 26S promoter on the negative strand drives transcription of the 26S RNA to levels 10 times that of the 42S genomic RNA (20, 21). Attenuated variants of VEE virus developed initially as live-attenuated vaccine candidates for VEE have also been configured as vaccine vector systems for the expression of heterologous genes (15). The VEE vaccine vector system utilized in the studies described here is composed of an RNA replicon and a bipartite helper system for packaging the replicon into propagation-deficient VEE replicon particles (VRPs). The replicon contains a multiple cloning site immediately downstream of the 26S promoter, which allows insertion of heterologous genes in place of the viral structural genes. The bipartite helper system is composed of two RNAs, one encoding the capsid gene (C) and the other encoding the glycoprotein genes (E3-E2-6K-E1). The glycoprotein genes also contain attenuating mutations which provide an additional level of safety in the unlikely event that multiple RNA recombination events regenerate replication-competent virus (15). After cotransfection of susceptible cells in vitro with the replicon RNA and both helper RNAs, VRPs containing recombinant replicons are produced. Pushko et al. used this system to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of replicons expressing either the Lassa virus nucleocapsid (N) gene or the influenza hemagglutinin gene (15). These researchers observed that cotransfection did not regenerate replication-competent virus, that sequential vaccination of mice against Lassa virus and influenza was possible, and that a protective immune response could be induced in mice against influenza virus.

Previous studies have also shown that guinea pigs and nonhuman primates vaccinated with VRP expressing either the glycoprotein (GP) gene alone or a mixture of VRP expressing either the GP gene or nucleoprotein genes from Marburg virus (MBGV) were protected from an otherwise-lethal challenge of MBGV (10). In a different study, mice were protected and guinea pigs were partially protected by vaccination with a VEE replicon expressing the genes from Ebola virus (14). Nonhuman primates were also partially protected against simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) after vaccination with a mixture of VRP expressing SIV gp160, gp140, and matrix-capsid genes (6).

Previous research has also shown that the nontoxic 50-kDa carboxy-terminal fragment (HC) of the BoNT serotype A (BoNT/A) heavy chain expressed in yeast or in Escherichia coli can protect mice from a lethal challenge of neurotoxin (2, 4). In this study, we have cloned the gene encoding the BoNT/A HC fragment into the VEE replicon vaccine vector (HC-replicon), assembled the HC-replicon into VRP (HC-VRP), and assessed the HC-VRP both in vitro and in vivo. Western blot and immunofluorescence analysis of whole cells infected with HC-VRP or lysates prepared from such cells were used to characterize the HC expression product. To evaluate the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of HC-VRP, mice were inoculated with various doses of HC-VRP, at different intervals, and challenged with increasing amounts of BoNT/A. The results of this study demonstrate that the HC-VRPs are capable of inducing efficient protection against an otherwise-lethal challenge with BoNT/A and define the vaccination schedule required for optimal immunogenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and production of VRP.

The design and construction of the VEE replicon vector system and the Lassa virus nucleocapsid replicon (N-replicon) was described previously (16). The synthetic BoNT/A HC gene was cloned into a shuttle vector (5) as a SalI/HindIII fragment from the pMutAC-1 plasmid previously described by Clayton et al. (4). The synthetic HC gene was then cloned from the shuttle vector into the VEE replicon plasmid as an XbaI/HindIII fragment.

Replicons were assembled into VRPs as previously described (15). Briefly, plasmid templates for the HC-replicon, C-helper, GP-helper, and the N-replicon were linearized by NotI digestion at a unique site adjacent to the VEE sequences, and capped runoff transcripts were prepared in vitro by using T7 RNA polymerase (RiboMAX Large Scale RNA Production System; Promega, Inc., Madison, Wis.). BHK cells were then cotransfected by electroporation (0.4-cm gap cuvette; three pulses, 0.85 kV, 25 μF) with replicon RNA and helper RNAs. VRPs were harvested between 20 and 27 h after transfection and partially purified from cell culture supernatants by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion at 27,000 rpm for 4 to 5 h in an SW28 swinging bucket rotor. The pelleted VRPs were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at −70°C.

Analysis of expression products and titration of VRP.

Subconfluent BHK cell monolayers were infected with HC-VRP or, alternatively, cell suspensions were transfected by electroporation with HC-replicon RNA. After incubation for 20 to 24 h at 37°C, cell lysates were prepared for Western blot analysis, and the proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). HC protein was detected by using horse anti-BoNT/A HC antisera (obtained from Mark Poli, USAMRIID, Fort Detrick, Frederick, Md.) and a chemiluminescence Western blot assay kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, N.J.).

Titers of VRPs were determined by infecting subconfluent BHK cell monolayers in eight-well chamber slides (Nunc, Inc.) with serial dilutions of purified VRP. Cells were fixed with methanol, and antigen-positive cells were visualized by indirect immunofluorescence by using a horse anti-BoNT/A HC antisera and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-horse antibody (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories, Inc.). Cells expressing Lassa virus N protein were detected by direct immunofluorescence with FITC-conjugated antibodies obtained from a monkey anti-Lassa serum. Cell nuclei were stained with 1 μg of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) per ml in VectaShield mounting medium (Vector Labs, Inc., Burlingame, Calif.). The VRP titers are expressed as focus-forming units (FFU), where 1 FFU is equivalent to 1 infectious unit (iu). VRP preparations were monitored for the generation of replication-competent VEE virus by a standard plaque-forming assay in which samples were tested directly and after blind passage of the preparations in BHK cell cultures. No PFU were found in any of the VRP preparations.

Vaccination and challenge of mice.

Groups of 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) (200 μl) at 7-, 14-, 21-, or 28-day intervals (as indicated) with 105, 106, or 107 iu of HC-VRP or with 107 iu of N-VRP (negative control replicon) diluted in PBS. Positive control mice were inoculated s.c. with 0.1 or 0.2 ml of botulinum toxoid vaccine at 28-day intervals. Serum for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was obtained 1 or 2 days before each inoculation and 3 to 5 days before challenge. Mice were challenged intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 100 μl containing 102, 103, 104, or 105 50% median lethal dose (MLD50) units of BoNT/A (as indicated) diluted in PBS containing 0.2% gelatin 30 or 31 days after the last inoculation.

For duration-of-immunity studies, five groups (I through V) of 6- to 8-week-old NIH Swiss mice were used. Each group consisted of 40 mice. In sets of 10 mice, the sets were inoculated with either 106 or 107 iu of HC-VRP, 107 iu of N-VRP (negative control), or 0.2 ml of botulinum toxoid vaccine (positive control). All of the groups received the appropriate inoculations at days 0 and 28. Group I was then challenged on day 196. Groups II and V were challenged on day 370. Group III animals received booster inoculations on day 168 and were then challenged on day 370. Group IV animals received booster inoculations on day 341 and were challenged on day 370. A minimum of 10 mice were bled at each time point 2 to 3 days before and at 28-day intervals after the second inoculation. The mice were also bled 2 to 7 days before and 28 to 35 days after challenge. Mice were challenged i.p. with 1,000 MLD50 units of BoNT/A on either day 196 or day 370. Note that, in conducting research using animals, we adhered to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 86-23).

ELISA.

Microtiter plates were coated with BoNT/A (1 μg/ml) in 100 μl of PBS and allowed to absorb overnight at 4°C. After the plates were washed five times with wash buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20), fourfold serial dilutions of serum in blocking buffer (100 μl; PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, 5% dried nonfat milk) were applied to the plates and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After another washing, 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody in blocking buffer (diluted 1:1,000; Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratory) was added to the plates and incubated for an additional hour at 37°C. After a washing step, bound antibody was detected colormetrically by using 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid) (ABTS) as a substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratory). Titers were defined as the reciprocal of the last dilution with an A405 of ≥0.1. Titers of <2.00 and >5.61 log10 were estimated. Serum samples from individual animals were assayed in duplicate. The duplicate measurements were then used to calculate a geometric mean titer for the group.

Statistical analysis.

For ELISA titer data obtained after BALB/c mice were inoculated at different intervals, an analysis of variance with a Student-Newman-Keuls multiple-range test was used to identify differences between the treatment groups. The probability of a type one error was set at 5% (α = 0.05). The Fisher exact test was used to determine statistical differences in survival between groups that received HC-VRP and the negative control group that received N-VRP.

RESULTS

Packaging and expression of the HC-replicon.

The HC-replicon was assembled into VRPs by using the bipartite helper system originally developed by Pushko et al. (15). The amount of packaged HC-replicon obtained in the cell culture supernatants ranged from 1.2 × 107 iu/ml to 4.8 × 107 iu/ml. No replication-competent virus was detected in either the medium from cotransfected cultures or after blind passage of the medium in BHK cell cultures.

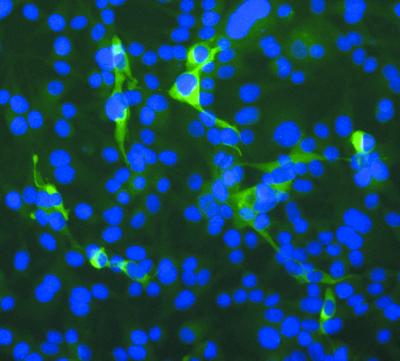

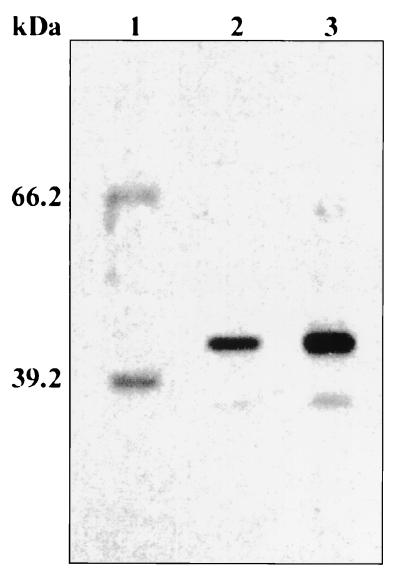

Figure 1 shows a photomicrograph of BHK cells infected with HC-VRP. Antigen-positive cells were detected by using a primary polyclonal horse anti-BoNT/A antibody and a secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated polyclonal goat anti-horse antibody. The staining pattern was consistent with cytoplasmic expression and retention of the HC polypeptide. Extensive nuclear, Golgi, or plasma membrane staining was not observed in BHK cells infected with HC-VRP. Cell lysates generated from BHK cells infected with HC-VRP contained large amounts of HC polypeptide, as demonstrated by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2). VEE replicons expressing HC produced proteins that comigrated on acrylamide gels with protein expressed in Escherichia coli and reacted with antibodies raised to the same protein.

FIG. 1.

Indirect immunofluorescence of BHK cells infected with HC-VRP. BoNT/A HC-positive cells appear green and DAPI-stained cell nuclei appear blue.

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of cell lysate from BHK cells infected with HC-VRP. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, lysate from cells infected with HC-VRP; lane 3, BoNT/A HC (E. coli expression product).

Effect of HC-VRP dose on protection against challenge with BoNT/A.

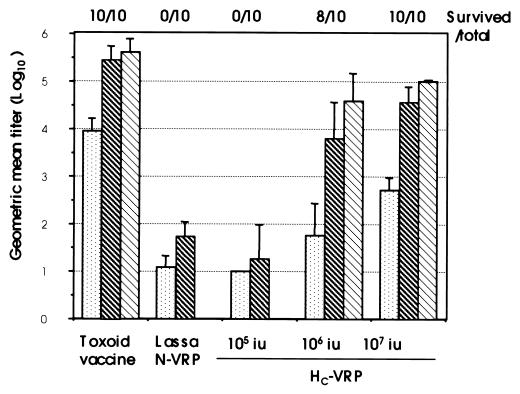

Figure 3 shows the ELISA titers and survival for BALB/c mice inoculated with two doses of 105, 106, or 107 iu of HC-VRP. The amount of HC-VRP (given on days 0 and 28) required to completely protect BALB/c mice from a lethal challenge of 1,000 MLD50 BoNT/A was between 106 and 107 iu per dose. The prechallenge serum ELISA titers from BALB/c mice inoculated with 105, 106, or 107 iu of HC-VRP were 1.27, 3.81, and 4.56 log10, respectively, compared to 1.73 log10 for mice that received N-VRP, the negative control replicon. None of the animals inoculated with 105 iu of HC-VRP or the negative control replicon survived challenge, whereas 8 of 10 and 10 of 10 mice that received 106 or 107 iu of HC-VRP, respectively, survived challenge.

FIG. 3.

Protection and ELISA GMT of BALB/c mice inoculated with different amounts of HC-VRP. Mice were inoculated s.c. at days 0 and 28 with either 0.2 ml of toxoid vaccine, 107 iu of Lassa N-VRP, or the indicated amount of HC-VRP. Mice were challenged on day 59 with 1,000 mLD50 units of BoNT/A. Columns: , Serum obtained on day 26; ▧, prechallenge serum obtained on day 56; ▧, postchallenge serum obtained on day 87. Serum samples from individual animals were assayed in duplicate, and the duplicate measurements were used to calculate the GMT for each group; titers greater than 5.61 log10 and less than 2 log10 were estimated.

Effect of HC-VRP vaccination schedule on protection against challenge with BoNT/A.

Results from animal studies demonstrated that the VEE replicon expressing the 50-kDa HC fragment of BoNT/A could protect mice from a lethal challenge of BoNT/A (Table 1). BALB/c mice inoculated with 107 iu of HC-VRP generally produced a primary antibody response which was maximal at day 19 and remained constant to day 26 (Table 1). Booster inoculations given 7, 14, 21, or 28 days after the primary inoculation induced a secondary antibody response that was 60-to 159-fold greater than the primary response. If both doses of the HC-VRP were given on the same day (i.e., a dose of 2 × 107 iu), the primary antibody response 28 days later was 2.96 log10 compared to 1.73 log10 for mice that received two doses of the control N-VRP at days 0 and 28, and were bled 28 days later. Mice that received the equivalent of two doses of HC-VRP on day 0 were not protected from challenge (1,000 MLD50 units of BoNT/A). However, the time to death was increased from 6 h (for mice that received the N-VRP) to 33 h. Mice that received a booster inoculation on day 7 produced a secondary antibody response of 3.23 log10 with 8 of 10 mice surviving challenge (1 mouse showed symptoms of slight flaccid paralysis). Mice that received booster inoculations on day 14, 21, or 28 produced higher secondary antibody responses of 3.87, 4.44, or 4.56 log10, respectively, with all mice surviving challenge with no apparent symptoms. Thus, at this dose, the most effective vaccination schedule was two doses of HC-VRP given at least 14 days apart.

TABLE 1.

Survival and ELISA titers of BALB/c mice inoculated with HC-VRP at different intervals

| Inoculum | Vaccination days | Log10

ELISA GMTd (SD)

|

Challenge

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-second inoculation | Prechallengee | No. surviving/total no. challengedf | MTD (h)g | ||

| HC-VRP | 0a | 2.96 (0.30) | 0/10 | 33 | |

| HC-VRP | 0 and 7b | 1.04 (0.12) | 3.23 (0.41) | 8/10∗ | 24 |

| HC-VRP | 0 and 14b | 1.66 (0.49) | 3.87 (0.27) | 10/10∗∗ | |

| HC-VRP | 0 and 21b | 2.66 (0.47) | 4.44 (0.50) | 10/10∗∗ | |

| HC-VRP | 0 and 28b | 2.72 (0.25) | 4.56 (0.33) | 10/10∗∗ | |

| N-VRPh | 0 and 28b | 1.10 (0.25) | 1.73 (0.31) | 0/10 | 6 |

| Toxoid | 0 and 28c | 3.96 (0.27) | 5.46 (0.27) | 10/10∗∗ | |

Mice were inoculated with 2 × 107 iu of VRP on day 0.

Mice were inoculated with 107 iu of VRP on the days indicated.

Mice were inoculated with 0.2 ml of toxoid vaccine on the days indicated.

Sera from individual animals were assayed in duplicate and used to calculate the log10 GMT for each group; sera were obtained 2 days before the second inoculation and before challenge.

For all pairwise multiple comparisons, P < 0.05, except between the day 0 and 21 group and the day 0 and 28 group.

Mice were challenged with the 1,000 MLD50 units of BoNT/A 28 days after the second inoculation. Comparisons of experimental group survival to N-VRP group survival: ∗, P = 0.0007; ∗∗, P < 0.0001

MTD, mean time to death.

Negative control, Lassa virus nucleocapsid-VRP.

Effect of the BoNT/A challenge dose on protection conferred by HC-VRP.

To determine the level of protection achieved with the HC-VRP, vaccinated mice were challenged with increasing amount of BoNT/A from 100 to 100,000 MLD50 units (Table 2). Two inoculations of 107 iu of HC-VRP given 28 days apart protected all mice from challenge at 100 and 1,000 LD50 units and 8 of 9 or 9 of 10 mice from a challenge of either 10,000 or 100,000 LD50 units of BoNT/A, respectively. The mice that survived showed no effects from the neurotoxin, i.e., no flaccid paralysis. The two mice that failed to survive challenge had ELISA titers of 2.00 and 5.01 log10.

TABLE 2.

Protection in HC-VRP-vaccinated BALB/c mice against increasing challenge doses of BoNT/A

| Replicon dosea | Log10 ELISA GMT (SD)b | Challenge dosec | No. surviving/ total no. challenged | MTDe (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 107 | 4.71 (0.31) | 102 | 10/10 | |

| 107 | 4.71 (0.31) | 103 | 10/10 | |

| 107 | 4.44 (0.88) | 104 | 8/9d | 6 |

| 107 | 4.71 (0.31) | 105 | 9/10 | 24 |

| N-VRPfh | 1.73 (0.31) | 103 | 0/10 | 6 |

| Toxoidgh | 5.46 (0.27) | 103 | 10/10 |

Mice were inoculated s.c. on days 0 and 28.

Sera obtained 2 days before challenge from individual animals were assayed in duplicate and used to calculate the log10 GMT for each group; for all pairwise multiple comparisons, P < 0.05, except between HC-VRP vaccinated groups.

Mice were challenged with the indicated MLD50 units of BoNT/A on day 56.

One animal died during bleeding before challenge.

MTD, mean time to death.

Negative control, Lassa virus nucleocapsid-VRP, with dose of 107 iu.

Positive control; dose was 0.2 ml.

Data are reproduced from Table 1; experiments were run concurrently.

Duration of HC-VRP induced immunity against BoNT/A.

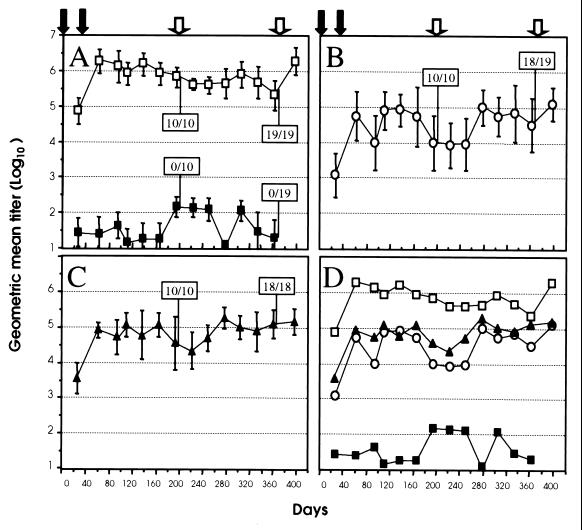

To determine the duration of immunity induced by HC-VRP vaccinations, Swiss mice were given two inoculations of 106 or 107 iu of HC-VRP 28 days apart and then serologically monitored for 13 months (Fig. 4). Two additional groups were inoculated with a third dose of HC-VRP on either day 168 or day 341. The responses in these mice were compared to control animals that received the toxoid vaccine or 107 iu of N-VRP. The peak antibody response in the mice given two doses of 106 iu of HC-VRP was 4.90 log10, which occurred at day 110 (Fig. 4B). Before the 6-month challenge (day 196), the geometric mean titer (GMT) of antibody in the mice was 3.99 log10, which protected all 10 mice from the effects of 1,000 MLD50 units of BoNT/A. The 12-month prechallenge titers in mice were 4.50 log10, which protected 18 of 19 mice challenged with the same amount of toxin. Mice inoculated with 107 iu of HC-VRP produced an antibody response of 5.07 log10 at day 110 (Fig. 4C). The antibody response in mice inoculated with two doses of 107 iu of HC-VRP tended to be higher than in mice similarly inoculated with 106 iu of HC-VRP. The antibody responses before the 6- and 12-month challenges were 4.54 and 5.08 log10, which protected 10 of 10 mice and 18 of 18 mice, respectively. All mice that survived challenge at either 6 or 12 months remained healthy, with no signs of BoNT intoxication. Mice inoculated with the toxoid vaccine produced an antibody response that peaked at 6.28 log10 on day 63. The antibody response decreased with time such that on day 194 (2 days before the 6-month challenge) the titer was 5.81 log10, and 10 of 10 mice survived the 6-month challenge (Fig. 4A). Before the 12-month challenge, the titers in the mice had decreased further to 5.31 log10; but all the mice survived the 12-month challenge with no morbidity. The antibody response in control mice inoculated with N-VRP was negligible at 2.17 and 1.30 log10 before the 6- and 12-month challenges, respectively. As expected, all N-VRP inoculated mice failed to survive challenge.

FIG. 4.

Duration of HC-VRP induced immunity against BoNT/A in Swiss mice. Mice were inoculated s.c. at days 0 and 28 (solid arrows) with either 0.2 ml of toxoid (A, □) or 107 iu of Lassa N-VRP (A, ■) or with 106 iu (B, ○) or 107 iu (C, ▴) of HC-VRP. These results are reproduced in panel D without error bars for comparison. See Materials and Methods for the inoculation schedule. Different groups of mice were challenged on either day 196 or day 370 (open arrows) with 1,000 MLD50 units of BoNT/A. Numbers in boxes indicate survivors versus the total number when challenged at the indicated times. Sera from individual animals were assayed in duplicate, and the duplicate measurements were used to calculate the GMT for a minimum of 10 animals bled in a staggered fashion; titers greater than 5.61 log10 and less than 2.00 log10 were estimated.

Swiss mice given three inoculations of 106 iu of HC-VRP at days 0, 28, and 168 produced eightfold-higher antibody titers (measured on day 335, GMT = 5.70 log10) compared to mice that only received two inoculations on day 0 and 28 (GMT = 4.82 log10). Similarly, mice inoculated with three doses of 107 iu of HC-VRP had a threefold increase in antibody titer (GMT = 5.38 log10) compared to mice that received only two inoculations (GMT = 4.87 log10). Inoculation of mice with three doses of 106 or 107 iu of HC-VRP on days 0, 28, and 341 produced a 10- and 4-fold increases in antibody titers relative to mice that received only two inoculations on days 0 and 28, respectively, when measured on day 363 (GMT = 5.51 and 5.61 log10 compared to 4.51 and 5.07 log10). All mice that received three inoculations of HC-VRP were protected from the effects of BoNT on day 370.

DISCUSSION

Although toxoid preparations for BoNT have proven effective for vaccinating against some serotypes, the production, preparation, and quality control of the required neurotoxins is expensive, labor-intensive, and hazardous. As a result, recent vaccine development efforts have focused on the production of nontoxic recombinant proteins or vectored vaccines. Both E. coli and yeast expression systems have been used in the production of BoNT HC (2, 4).

Vaccines composed of recombinant HC protein have been shown to protect mice from the effects of BoNT/A. Clayton et al. expressed a synthetic HC gene in E. coli (1, 13, 17, 24) and used whole bacterial cell lysates containing the HC polypeptide combined with Freund adjuvant to protect some ICR mice from challenge (4). Subsequently, Byrne et al. developed a method for purification of the HC polypeptide expressed from the synthetic gene in the yeast Pichia pastoris (2) and showed protection in mice vaccinated with purified HC combined with aluminum hydroxide adjuvant (2, 9). Another approach for developing BoNT vaccines has focused on “naked” DNA vaccine vectors. Two research groups have demonstrated that DNA-based vaccines can partially protect animals from challenge with BoNT/A (3, 18).

Alphavirus replicon vectors have the ability to express high amounts of a foreign protein in eukaryotic cells (12, 15), and such vectors show considerable promise as vaccine vectors for the transient expression of foreign genes in animals. By inserting the synthetic HC gene in the VEE replicon vector, we were able to achieve high-level expression of HC polypeptide in eukaryotic cells as visualized by immunofluorescence of cells infected with HC-VRP and also by Western blot analysis of cell lysates generated after cells were infected with the same HC-VRP. Because alphaviruses replicate in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells (20), expression of the HC gene in the cytoplasm alleviates the difficulties imposed by conventional nuclear transcription of plasmids, i.e., limiting or incompatible transcription factors, mRNA splicing, and transport of the mRNA out of the nucleus (17).

In the studies reported here, VEE replicon vaccines expressing the HC fragment of BoNT/A (HC-VRP) induced a strong antibody response in BALB/c mice that was both dose and schedule dependent. Mice inoculated with the highest dose of HC-VRP (107 iu) produced the greatest antibody responses and were completely protected from challenge. Vaccinations with doses of less than 107 iu stimulated a weaker immune response, which only partially protected the animals. To define an optimal vaccination schedule, mice were inoculated with two doses of 107 iu of HC-VRP separated by 0, 7, 14, 21, or 28 days. The antibody responses induced varied directly with the length of time between the two doses. Inoculations spread out over several weeks stimulated the strongest immune responses, indicating that anamnestic responses were elicited. Complete protection from challenge was observed in groups of mice vaccinated at an interval of 14 days or more between inoculations. However, 80% of the mice were protected with two doses given only 7 days apart. Mice inoculated with two doses of 107 iu of HC-VRP at an interval of 28 days produced the highest antibody responses and were protected against very high doses of toxin (100,000 MLD50 units).

Previous research utilizing viruses as vaccine vectors has shown that animals vaccinated with such vectors often developed high neutralizing responses against the vector, as well as immune responses against the foreign gene (11). In these studies, the VEE replicon vector induced anti-VEE neutralizing antibodies in the outbred mice but not in the BALB/c mice (data not shown). Nevertheless, the anti-BoNT/A antibody responses induced in the outbred mice were higher than those observed in the BALB/c mice. The VEE neutralizing antibody responses may have been stimulated by the presence of viral glycoprotein in the replicon particles themselves, or from copurified cell membrane debris containing VEE glycoprotein, or from a recombination or copackaging event between the replicon and the glycoprotein helper RNA (7, 15, 16, 25). Additional studies are in progress to define the basis for the induction of VEE neutralizing immune responses in the outbred mice.

The duration of immunity and protection induced by HC-VRP was also evaluated and compared to that achieved with the toxoid vaccine. Outbred Swiss mice were found to produce somewhat higher antibody responses than that seen in BALB/c mice, so the outbred mice were then used to evaluate the duration of immunity induced by HC-VRP. We found that two inoculations of 107 iu of HC-VRP given on days 0 and 28 produced both primary and secondary anamnestic antibody responses that efficiently protected these mice from a BoNT/A challenge at 6 and at 12 months postvaccination. Swiss mice inoculated with the toxoid vaccine initially produced somewhat higher antibody responses than those inoculated with two doses of 107 iu of HC-VRP, but the level of toxoid-induced antibody fell over time such that, at 12 months, the response was similar in both groups. No appreciable fall in antibody titers was noted over a period of 12 months in the mice inoculated with two doses of either 106 or 107 iu of HC-VRP. Swiss mice given three inoculations of 106 or 107 iu of HC-VRP, at days 0 and 28, and then boosted again at day 168 or day 341 were also completely protected from challenge at day 370.

Since seven serotypes of BoNT are known, the ease with which genes may be cloned into the VEE replicon make this vector system attractive as a platform for developing multivalent vaccines. Replicon vaccines expressing the remaining six serotypes have been constructed and are being studied for their immunogenicity both individually and in combination. In addition, single replicons expressing several HC genes are also being evaluated. Our use of the VEE replicon as a vaccine vector for inducing immune responses against BoNT demonstrates that prokaryotic genes can also be accurately and efficiently expressed in eukaryotic cells with this vector system and that such expression can elicit a highly protective immune response of long duration.

REFERENCES

- 1.Binz T, Kurazono H, Wille M, Frevert J, Wernars K, Meimann H. The complete sequence of botulinum neurotoxin type A and comparison with other clostridial neurotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9153–9158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne M P, Smith T J, Montgomery V A, Smith L A. Purification, potency, and efficacy of the botulinum neurotoxin type A binding domain from Pichia pastorisas a recombinant vaccine candidate. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4817–4822. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4817-4822.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton J, Middlebrook J L. Vaccination of mice with DNA encoding a large fragment of botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Vaccine. 2000;18:1855–1862. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton M A, Clayton J M, Brown D R, Middlebrook J L. Protective vaccination with a recombinant fragment of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin serotype A expressed from a synthetic gene in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2738–2742. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2738-2742.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis N L, Brown K W, Johnston R E. A viral vaccine vector that expresses foreign genes in lymph nodes and protects against mucosal challenge. J Virol. 1996;70:3781–3787. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3781-3787.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis N L, Caley I J, Brown K W, Betts M R, Irlbeck D M, McGrath K M, Connell M J, Montefiori D C, Frelinger J A, Swanstrom R, Johnson P R, Johnston R E. Vaccination of macaques against pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus with Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon particles. J Virol. 2000;74:371–378. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.371-378.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geigenmüller-Gnirke U, Weiss B, Wright R, Schlesinger S. Complementation between Sindbis viral RNAs produces infectious particles with a bipartite genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3253–3257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatheway C L. Botulism. In: Balows A, Hausler J W J, Ohashi M, Turano A, editors. Laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases: principles and practice. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag Inc.; 1988. pp. 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heimlich J, Regnier F, White J, Hem S. The in vitro displacement of adsorbed model antigens from aluminum-containing adjuvants by interstitial proteins. Vaccine. 1999;17:2873–2881. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hevey M, Negley D, Pushko P, Smith J, Schmaljohn A. Marburg virus vaccines based upon alphavirus replicons protect guinea pigs and nonhuman primates. Virology. 1998;251:28–37. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kündig T M, Kalberer C P, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R M. Vaccination with two different vaccinia recombinant viruses: long-term inhibition of secondary vaccination. Vaccine. 1993;11:1154–1158. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90079-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liljeström P, Garoff H. A new generation of animal cell expression vectors based on the Semliki Forest virus replicon. Biotechnology. 1991;9:1356–1361. doi: 10.1038/nbt1291-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makoff A J, Oxer M D, Romanos M A, Fairweather N F, Ballantine S. Expression of tetanus toxin fragment C in E. coli: high-level expression by removing rare codons. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:10191–10202. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.24.10191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pushko P, Parker M, Geisbert J, Negley D, Schmaljohn A, Jahrling P, Smith J, editors. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicon vector: immunogenicity studies with Ebola NP and GP genes in guinea pigs. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pushko P, Parker M, Ludwig G V, Davis N L, Johnston R E, Smith J F. Replicon-helper systems from attenuated Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus: expression of heterologous genes in vitro and immunization against heterologous pathogens in vivo. Virology. 1997;239:389–401. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raju R, Subramaniam S V, Hajjou M. Genesis of Sindbis virus by in vivo recombination of nonreplicative RNA precursors. J Virol. 1995;69:7391–7401. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7391-7401.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romanos M A, Makoff A J, Fairweather N F, Beesley K M, Slater D E, Rayment F B, Payne M M, Clare J J. Expression of tetanus toxin fragment C in yeast: gene synthesis is required to eliminate fortuitous polyadenylation sites in AT-rich DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1461–1467. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.7.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shyu R H, Shaio M F, Tang S S, Shyu H F, Lee C F, Tsai M H, Smith J E, Huang H H, Wey J J, Huang J L, Chang H H. DNA vaccination using the fragment C of botulinum neurotoxin type A provided protective immunity in mice. J Biomed Sci. 2000;7:51–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02255918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith L A. Development of recombinant vaccines for botulinum neurotoxin. Toxicon. 1998;36:1539–1548. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss E G, Strauss J H. Structure and Replication of the alphavirus genome. In: Schlesinger S, Schlesinger M, editors. The Togaviridae and the Flaviviridae. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 35–90. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss J H, Strauss E G. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:491–562. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.491-562.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugiyama H. Clostridial botulinumneurotoxin. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:419–448. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.3.419-448.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tacket C O, Rogawski M A. Botulism. In: Simpson L L, editor. Botulinum neurotoxin and tetanus toxin. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1989. pp. 351–378. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson D E, Brehm J K, Oultram J D, Swinfield T J, Shone C C, Atkinson T, Melling J, Minton N P. The complete amino acid sequence of the Clostridium botulinumtype A neurotoxin, deduced by the nucleotide sequence analysis of the encoding gene. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss B G, Schlesinger S. Recombination between Sindbis virus RNAs. J Virol. 1991;65:4017–4025. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4017-4025.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]