Abstract

Introduction

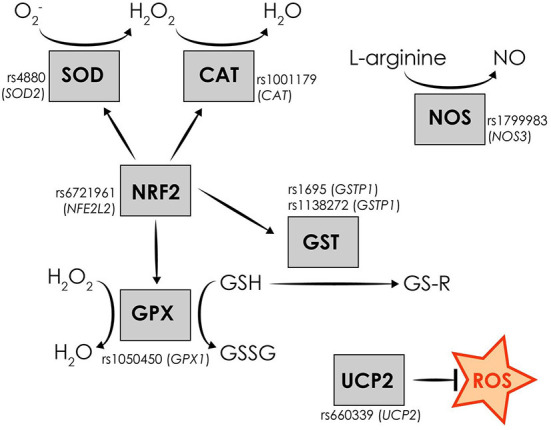

Migraine is a complex disorder with genetic and environmental inputs. Cumulative evidence implicates oxidative stress (OS) in migraine pathophysiology while genetic variability may influence an individuals' oxidative/antioxidant capacity. Aim of the current study was to investigate the impact of eight common OS-related genetic variants [rs4880 (SOD2), rs1001179 (CAT), rs1050450 (GPX1), rs1695 (GSTP1), rs1138272 (GSTP1), rs1799983 (NOS3), rs6721961 (NFE2L2), rs660339 (UCP2)] in migraine susceptibility and clinical features in a South-eastern European Caucasian population.

Methods

Genomic DNA samples from 221 unrelated migraineurs and 265 headache-free controls were genotyped for the selected genetic variants using real-time PCR (melting curve analysis).

Results

Although allelic and genotypic frequency distribution analysis did not support an association between migraine susceptibility and the examined variants in the overall population, subgroup analysis indicated significant correlation between NOS3 rs1799983 and migraine susceptibility in males. Furthermore, significant associations of CAT rs1001179 and GPX1 rs1050450 with disease age-at-onset and migraine attack duration, respectively, were revealed. Lastly, variability in the CAT, GSTP1 and UCP2 genes were associated with sleep/weather changes, alcohol consumption and physical exercise, respectively, as migraine triggers.

Discussion

Hence, the current findings possibly indicate an association of OS-related genetic variants with migraine susceptibility and clinical features, further supporting the involvement of OS and genetic susceptibility in migraine.

Keywords: antioxidant enzymes, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), primary headaches, migraine genetics, redox homeostasis

1. Introduction

Migraine is a complex, disabling primary headache disorder with a high worldwide prevalence, estimated ~15%, female preponderance (3:1 female-to-male ratio), and genetic predisposition (1–3). Typically is characterized by recurrent attacks of moderate to severe throbbing headache, lasting 4–72 h, aggravated by routine physical activity and often accompanied by symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and/or phonophobia (4, 5). About 30% of migraine cases undergo transient, reversible focal neurological symptoms, the so-called aura, occurring usually before the headache phase (6, 7). Migraine clinical diagnosis is based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition (ICHD-III) criteria, which subdivides migraine into two major subtypes with substantial symptomatic overlap, namely migraine without aura (MwoA) and migraine with aura (MwA) (4).

Neurological and vascular mechanisms are believed to be involved in migraine pathophysiology. Main events implicated are cortical spreading depression, activation of the trigeminovascular system, and neurogenic inflammation causing meningeal vasculature changes and the release of various migraine markers. Recent evidence supported an emerging role of metabolic abnormalities, including oxidative stress, in migraine pathogenesis (8, 9). Even though some studies investigating certain markers of oxidative stress are inconsistent, cumulative findings largely indicate an alteration in physiological redox balance in migraine patients characterized by increased oxidative or nitrosative stress and/or reduced antioxidant capacity (10–12). Furthermore, oxidative stress seems to be a common denominator of the most common migraine triggers, which are likely to further enhance oxidative stress levels (13).

Migraine is a multifactorial disease, as most common complex disorders, with a substantial genetic component indicated by family and twin epidemiological studies (14–16). Thus, migraine phenotypes seem to be shaped by genetic susceptibility and exposure to environmental triggers (17, 18). Heritability seems to be more eminent in MwA subtype than MwoA, further supported by the identification of mutations in three ion transporter genes (CACNA1A, ATP1A2, and SCN1A) associated with familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM); a rare monogenic form of MwA (19). The more common subtypes of migraine are mainly polygenic, with a complex interaction between numerous genetic variants, each having a small genetic effect, conferring disease susceptibility (17, 20). Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified multiple genetic variants associated with migraine susceptibility (21–26). In addition, genetic factors seem to influence clinical features of common migraine i.e., earlier age of disease onset, increased migraine frequency in males and higher number of days with medication (27).

Considering the implication of oxidative stress in migraine pathophysiology and the strong genetic component of the disorder, variation in oxidative stress-related genes may contribute to migraine susceptibility. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes encoding for oxidative stress-related proteins may modify protein function resulting in increased oxidative-stress levels associated with various diseases, including migraine. Hence, aim of the current study was to examine the possible association between eight SNPs in oxidative stress-related genes, namely rs4880 (SOD2), rs1001179 (CAT), rs1050450 (GPX1), rs1695 (GSTP1), rs1138272 (GSTP1), rs1799983 (NOS3), rs6721961 (NFE2L2), and rs660339 (UCP2), and the susceptibility to develop migraine and sub-clinical phenotypes, in South-eastern European Caucasian (SEC) clinically examined patients and controls (Table 1, Figure 1). The frequency distribution of the majority of the investigated SNPs, associated with the incidence of various diseases, was previously examined by Katsarou et al. in a Caucasian population of the Southeastern European region (28). Identifying the genetic factors implicated in the susceptibility to develop migraine clinical phenotypes and features may contribute potentially to discover possible diagnostic biomarkers, to uncover key protein molecules and thus understand more accurately the disease pathophysiology, and ultimately to allow early set-up of treatment and more precise therapeutic strategies.

Table 1.

Summary of the investigated oxidative stress-related SNPs.

| Gene | Locus | Protein |

SNP (dbSNP RefSNP) |

Consequence | MAF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | ALL | EUR | |||||

| SOD2 - MnSOD | 6q25.3 | Superoxide Dismutase 2 | rs4880 | Missense Variant (p.Val16Ala) | C | 0.41 | 0.47 |

| CAT | 11p13 | Catalase | rs1001179 | Upstream Transcript Variant | T | 0.13 | 0.23 |

| GPX1 | 3p21.31 | Glutathione Peroxidase 1 | rs1050450 | Missense Variant (p.Pro200Leu) | A | 0.22 | 0.34 |

| GSTP1 | 11q13.2 | Glutathione S-Transferase Pi 1 | rs1695 | Missense Variant (p.Ile105Val) | G | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| rs1138272 | Missense Variant (p.Ala114Val) | T | 0.03 | 0.07 | |||

| NOS3 | 7q36.1 | Nitric Oxide Synthase 3/Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) | rs1799983 | Missense Variant (p.Asp298Glu) | T | 0.18 | 0.34 |

| NFE2L2 | 2q31.2 | Nuclear Factor, Erythroid 2 Like 2 (NRF2) | rs6721961 | Upstream Transcript Variant | T | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| UCP2 | 11q13.4 | Uncoupling Protein 2 | rs660339 | Missense Variant (p.Ala55Val) | A | 0.42 | 0.40 |

Information retrieved from: https://www.genecards.org/ and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/.

SNP, Single Nucleotide Polymorphism; MAF, Minor Allele Frequency; ALL, Global; EUR, European.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the investigated oxidative stress-related genetic variants and the function of the encoded oxidative stress-related proteins.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Study population

The current case-control study involved 486 unrelated subjects with SEC origin. A total of 221 subjects (37 males and 184 females) diagnosed by experienced neurologists as migraineurs according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria (ICHD-3), aged between 18 and 72 years (mean ± standard deviation: 41.9 ± 11.3 years), served as case group. The case group was prospectively recruited from specialized headache clinics located in Glyfada and Thessaloniki, Greece, between September 2019 and July 2021. The control group consisted of 265 neurologically healthy individuals (133 males, 132 females) with no personal and family history of migraine or any other headache disorder, aged between 21 and 85 years (mean ± standard deviation: 57.7 ± 12.8 years). Control subjects were recruited from the Neurology Department, University Hospital of Larissa, Greece. Data collected from control subjects included only age and gender. Demographic data of the study population, anthropometric data and the main clinical characteristics of migraine cohort are summarized in Table 2. Each study subject was assigned with a unique serial number to conceal their identity. All study subjects signed a written informed consent. Approval was obtained by the appropriate Ethic Committees (Mediterraneo Hospital, Glyfada, Greece, and University Hospital of Larissa) and the research was performed in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Migraine patients | Headache-free controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 221) | (N = 265) | |||

| Age (years)* | 41.9 ± 11.3 ranged from 18 to 72 | 57.7 ± 12.8 ranged from 21 to 85 | ||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 37 | (16.7) | 133 | (50.2) |

| Female | 184 | (83.3) | 132 | (49.8) |

| BMI (kg/m 2 )* | 24.6 ± 4.2 | – | ||

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 130 | (58.8) | – | |

| Former | 27 | (12.2) | – | |

| Ever | 64 | (29.0) | – | |

| Age of diagnosis (years) * | 20.1 ± 8.2 ranged from 5 to 52 | – | ||

| Positive family history, n (%) | 163 | (73.8) | – | |

| Type of migraine, n (%) | ||||

| 1.1. MwoA | 127 | (57.5) | – | |

| 1.2. MwA | 27 | (12.2) | – | |

| 1.3. CM | 67 | (30.3) | – | |

Values are presented as mean ± SD.

BMI, body mass index; MwoA, Migraine without Aura; MwA, Migraine with Aura; CM, Chronic Migraine.

2.2. DNA extraction and genotyping

Epithelial cells from the participants oral cavity were collected by sterile buccal swabs. Genomic DNA was extracted from the epithelial cell samples using a commercial nucleic acid isolation kit (Nucleospin Tissue; Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co., KG, Düren, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA concentration was determined by Nanodrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) and the samples were stored at −20°C until further analysis. Genotyping for the investigated oxidative stress-related SNPs (rs4880-SOD2, rs1001179-CAT, rs1050450-GPX1, rs1695-GSTP1, rs1138272-GSTP1, rs1799983-NOS3, rs6721961-NFE2L2, and rs660339-UCP2) was carried out by real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction in LightCycler® 480 System (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) using SimpleProbe® probes (LightSNiP assays; TIB Molbiol, Berlin, Germany), followed by melting curve analysis. In particular, DNA samples (50 ng) were amplified using the respective LightSNiP Assay for each SNP and Lightcycler®FastStart DNA Master HybProbe Mix (Roche, Germany), according to the following PCR protocol: initial denaturation for 10 min at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation for 10 s at 95°C, primer annealing for 10 s at 60°C and extension for 15 s at 72°C, followed by melting curve analysis to determine homozygosity for the wild-type alleles, heterozygosity, and homozygosity for the variant alleles.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Continuous data are described as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical data as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Distribution of the continuous variables was examined with Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilks tests. The disease age-at-onset (years), current frequency of migraine attacks (days/month) and typical duration of migraine attacks (hours) were not normally distributed, thus non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney test for two-group comparisons and Kruskal-Wallis test for three-group comparisons) were used to investigate their association with the examined SNPs. Genotype and allele frequencies of the selected SNPs were compared between groups using chi-square (χ2; Pearson or Fischer's exact) tests under co-dominant, dominant, recessive, over-dominant genotypic and allelic inheritance models. Contingency 2 × 2 tables were designed and crude odds ratios (OR) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to examine the association of the investigated SNPs with migraine and migraine subtypes susceptibility, and clinical traits. Logistic regression analysis was also applied to adjust for potential confounding factors including age (continuous), gender (categorical), Body Mass Index (BMI) (continuous), and smoking status (categorical). Two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. However, in some tests the p-value threshold automatically reduced to 0.01 to overcome the multiple tests effect, such as the Bonferroni correction etc. Statistical analyses were carried out by the IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 26.0 for Windows), R language for statistical computing (violin plots extraction) as well as G*Power software for power analysis. Consistency of the genotype frequency distributions with the Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) was examined with chi-square test using the web-based Online Encyclopedia for Genetic Epidemiology studies software (29). Haplotype analyses were carried out using the SHEsis web-based platform (http://analysis.bio-x.cn/myAnalysis.php) (30, 31).

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of association between oxidative stress-related SNPs and migraine susceptibility

Genotype frequencies of the investigated SNPs were consistent with HWE in both case and control groups (p > 0.05), except from the GPX1 rs1050450 which deviated from the HWE in the control group (p = 0.010). The observed genotype and allele frequency distribution of the investigated SNPs did not differ significantly between case and control subjects in any of the genetic inheritance model tested (p > 0.05) in the overall SEC population of the study. A statistically significant difference was observed for the NOS3 rs1799983 variant between migraineurs and control male subjects, as reported in Table 3, although no statistically significant difference was observed between cases and controls in the overall SEC population for the rs1799983 (Table 4). After adjustment, the more common G allele of the rs1799983 (83.8 vs. 65.8%) and homozygous GG genotype (73.0 vs. 43.6%) were statistically more prevalent in male migraineurs compared to the male control group [GG vs. GT + TT: ORadj 2.766 (1.060–7.222), padj = 0.038; G vs. T: OR 2.687 (1.378–5.240), p = 0.003] (Table 3). Hence, homozygosity for the NOS3 rs1799983 more common G allele seems to be associated with substantially increased migraine susceptibility in male population. Stratified analysis based on migraine subtypes showed no statistically significant differences in allele or genotype frequency distributions of the examined SNPs among MwoA, MwA, and chronic migraine (CM) patients and migraine-free controls in any of the genetic inheritance model tested (data not shown).

Table 3.

Genotypic and allelic frequency distribution analysis of the NOS3 rs1799983 variant in male subjects.

| NOS3 rs1799983 | ♂ Migraine cases (N = 37) | ♂ Controls (N = 133) | OR (95% CI) | p | ORadj (95% CI)* | padj* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |||||

| GG | 27 | (73.0) | 58 | (43.6) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –i |

| GT | 8 | (21.6) | 59 | (44.4) | 3.433 (1.441–8.180) | 0.004 | 2.281 (0.807–6.448) | 0.120 |

| TT | 2 | (5.4) | 16 | (12.0) | 3.724 (0.799–17.359) | 0.077 | 5.259 (0.811–34.087) | 0.082 |

| GT + TT | 10 | (27.0) | 75 | (56.4) | 3.491 (1.565–7.789) | 0.002 | 2.766 (1.060–7.222) | 0.038 |

| TT | 2 | (5.4) | 16 | (12.0) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –ii |

| GT | 8 | (21.6) | 59 | (44.4) | 0.922 (0.178–4.776) | 1.000** | 0.423 (0.054–3.325) | 0.413 |

| GT + GG | 35 | (94.6) | 117 | (88.0) | 0.418 (0.092–1.906) | 0.368** | 0.231 (0.036–1.505) | 0.126 |

| GT | 8 | (21.6) | 59 | (44.4) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –iii |

| TT + GG | 29 | (78.4) | 74 | (55.6) | 0.346 (0.147–0.813) | 0.012 | 0.529 (0.194–1.442) | 0.213 |

| G | 62 | (83.8) | 175 | (65.8) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –iv |

| T | 12 | (16.2) | 91 | (34.2) | 2.687 (1.378–5.240) | 0.003 | - | - |

OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

Adjusted for age.

Two-tailed Fisher's Exact test.

Power = 0.839.

Power = 0.882.

Power = 0.933.

Power = 0.933.

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

Table 4.

Genotypic and allelic frequency distribution analysis of the NOS3 rs1799983 variant between migraine cases and control subjects.

| NOS3 rs1799983 | OR (95% CI) | P -value | OR (95% CI)* | P -value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migraine cases vs. controls | ||||

| GG vs. TT | 1.396 (0.748–2.605) | 0.294 | 1.618 (0.711–3.681) | 0.252 |

| GG vs. GT | 1.188 (0.815–1.732) | 0.371 | 1.112 (0.686–1.803) | 0.666 |

| GT vs. TT | 1.175 (0.628–2.199) | 0.614 | 1.482 (0.610–3.603) | 0.385 |

| GG vs. GT + TT | 1.224 (0.855–1.752) | 0.269 | 1.202 (0.756–1.913) | 0.436 |

| TT vs. GT + GG | 0.779 (0.429–1.415) | 0.412 | 0.632 (0.282–1.415) | 0.264 |

| GT vs. GG + TT | 0.894 (0.624–1.282) | 0.543 | 0.970 (0.609–1.545) | 0.898 |

| G vs. T | 1.182 (0.901–1.550) | 0.226 | - | - |

Adjusted for age and gender.

3.2. Analysis of association between oxidative stress-related SNPs and migraine clinical features

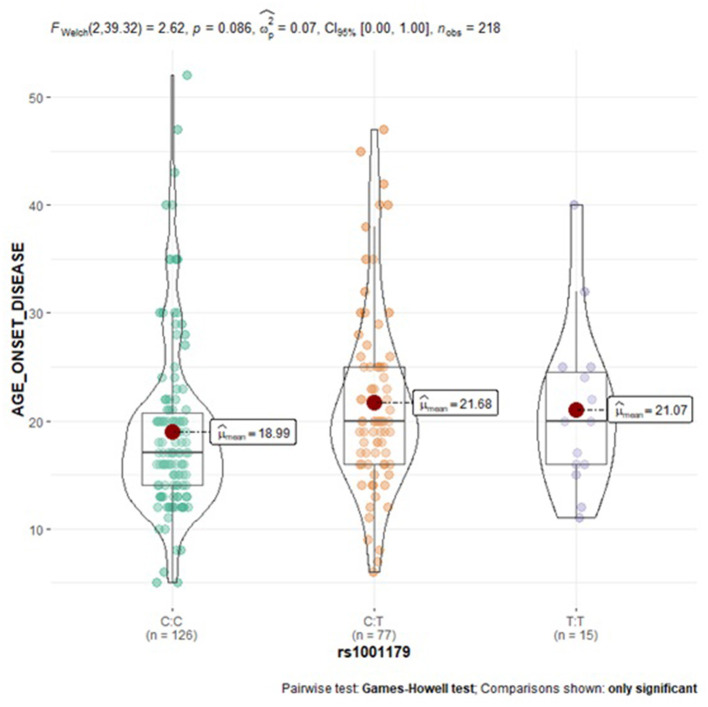

Subgroup analysis of the examined SNPs and disease clinical features (age at onset, attack frequency, and attack duration) in migraine group was performed to assess genotype-phenotype associations. As reported in Table 5, a statistically significant trend of association was revealed for the CAT rs1001179 variant with the disease age at onset. In particular, homozygosity for the minor T allele and heterozygosity were associated with a later age at onset (CT: 21.68 ± 8.40-years-old; TT: 21.07 ± 7.60-years-old) as compared to the homozygosity for the more common C allele (CC: 18.99 ± 8.06-year-old); consequently, the rs1001179 variant T allele may serve as a genetic factor possibly leading to a later age at onset of migraine (Figure 2). Moreover, a statistically significant association between GPX1 rs1050450 variant and migraine attack duration was observed. The rs1050450 variant T allele (40.0 vs. 27.8%) and TT homozygosity (16.4 vs. 7.0%) were significantly more prevalent in patients with longer attack duration (>24 h) as compared to patients with shorter attack duration (≤ 24 h) [C vs. T: OR 1.727 (1.097–2.719), p = 0.018; TT vs. CT + CC: ORadj 0,362 (0.138–0.951), padj = 0.039] (Table 6). In addition, a trend of association was indicated between NOS3 rs1799983 variant T allele and longer attack duration (>24 h); homozygous and heterozygous carriers of the rs1050450 variant T allele (62.5 vs. 37.5%) seem to experience migraine attacks longer than 24 h as compared to homozygous for the more common G allele [G vs. T: OR 1.481 (0.941–2.332), p = 0.089; GG vs. GT + TT: ORadj 1.731 (0.910–3.291), padj = 0.094] (Table 7). No statistically significant association was indicated for the SOD2 rs4880, GSTP1 rs1695, and rs1138272, NFE2L2 rs6721961, and UCP2 rs660339 variants with age at onset, attack frequency and attack duration in the SEC migraine subjects of the current study.

Table 5.

Analysis of the CAT rs1001179 variant association with clinical features in migraineurs.

| CAT rs1001179 | CC | CT | TT | p * | CT+TT | p a ** | CC+CT | p b ** | CC+TT | p c ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migraineurs subjects (N = 218) | 126 | 77 | 15 | 92 | 203 | 141 | ||||

| Age at onset | 18.99 ± 8.06 | 21.68 ± 8.40 | 21.07 ± 7.60 | 0.010d, i | 21.58 ± 8.24 | 0.002 ii | 20.01 ± 8.27 | 0.435 | 19.21 ± 8.01 | 0.006 iii |

| (years) | 17 (5–52) | 20 (6–47) | 20 (11–40) | 20 (6–47) | 19 (5–52) | 17 (5–52) | ||||

| Attack frequency | 10.66 ± 8.26 | 11.56 ± 9.22 | 10.73 ± 7.06 | 0.859 | 11.43 ± 8.88 | 0.605 | 11.00 ± 8.63 | 0.729 | 10.67 ± 8.12 | 0.726 |

| (days/month) | 8 (0.25–30) | 10 (0.33–30) | 10 (2–25) | 10 (0.33–30) | 9 (0.25–30) | 8 (0.25–30) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD and median (min-max). Bold values are considered statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Kruskal-Wallis Test.

Mann-Whitney Test.

CT + TT vs. CC.

CC + CT vs. TT.

CC + TT vs. CT.

CC vs. CT adjusted by the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests p = 0.010.

Power = 0.917.

Power = 0.922.

Power = 0.998.

Figure 2.

Violin plots displaying the mean age at disease onset according to CAT rs1001179 genotype profile in migraine subjects.

Table 6.

Genotypic and allelic frequency distribution analysis of the GPX1 rs1050450 variant in migraineurs according to the typical duration of migraine attacks (≤24 vs. >24 h).

| GPX1 rs1050450 | Attack duration (N = 213) | OR (95% CI) | p | ORadj (95% CI)* | padj * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤24 h (N = 158) | >24 h (N = 55) | |||||||

| N | (%) | n | (%) | |||||

| CC | 81 | (51.3) | 20 | (36.4) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –i |

| CT | 66 | (41.8) | 26 | (47.3) | 1.595 (0.819–3.110) | 0.168 | 1.559 (0.796–3.057) | 0.196 |

| TT | 11 | (7.0) | 9 | (16.4) | 3.314 (1.210–9.077) | 0.023 ** | 3.973 (1.345–11.734) | 0.013 |

| CT + TT | 77 | (48.7) | 35 | (63.6) | 1.841 (0.979–3.463) | 0.057 | 1.784 (0.943–3.375) | 0.075 |

| CT | 66 | (41.8) | 26 | (47.3) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –ii |

| TT | 11 | (7.0) | 9 | (16.4) | 2.077 (0.771–5.595) | 0.143 | 2.223 (0.793–6.232) | 0.129 |

| TT + CC | 92 | (58.2) | 29 | (52.7) | 0.800 (0.432–1.482) | 0.478 | 0.836 (0.448–1.560) | 0.573 |

| TT | 11 | (7.0) | 9 | (16.4) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –iii |

| CT + CC | 147 | (93.0) | 46 | (83.6) | 0.382 (0.149–0.980) | 0.040 | 0.362 (0.138–0.951) | 0.039 |

| C | 228 | (72.2) | 66 | (60.0) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –iv |

| T | 88 | (27.8) | 44 | (40.0) | 1.727 (1.097–2.719) | 0.018 | - | - |

Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, and smoking status.

Two-tailed Fisher's Exact test.

Bold values are considered statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Power = 0.617.

Power = 0.821.

Power = 0.807.

Power = 0.901.

Table 7.

Genotypic and allelic frequency distribution analysis of the NOS3 rs1799983 variant in migraineurs according to the typical duration of migraine attacks (≤ 24 vs. >24 h).

| NOS3 rs1799983 | Attack duration (N = 220) | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI)* | padj * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 24 h (N = 164) | >24 h (N = 56) | |||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |||||

| GG | 86 | (52.4) | 21 | (37.5) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –i |

| GT | 64 | (39.0) | 29 | (51.8) | 1.856 (0.971–3.548) | 0.060 | 1.780 (0.906–3.500) | 0.094 |

| TT | 14 | (8.5) | 6 | (10.7) | 1.755 (0.603–5.110) | 0.371** | 1.715 (0.572–5.144) | 0.336 |

| GT + TT | 78 | (47.6) | 35 | (62.5) | 1.838 (0.987–3.422) | 0.053 | 1.731 (0.910–3.291) | 0.094 |

| GT | 64 | (39.0) | 29 | (51.8) | 1.0 (reference) | - | - | -ii |

| TT | 14 | (8.5) | 6 | (10.7) | 0.946 (0.330–2.709) | 0.917 | 1.054 (0.350–3.175) | 0.925 |

| TT + GG | 100 | (61.0) | 27 | (48.2) | 0.596 (0.323–1.098) | 0.095 | 0.644 (0.341–1.215) | 0.174 |

| TT | 14 | (8.5) | 6 | (10.7) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –iii |

| GT + GG | 150 | (91.5) | 50 | (89.3) | 0.778 (0.284–2.132) | 0.625 | 0.738 (0.263–2.067) | 0.563 |

| G | 236 | (72.0) | 71 | (63.4) | 1.0 (reference) | – | – | –iv |

| T | 92 | (28.0) | 41 | (36.6) | 1.481 (0.941–2.332) | 0.089 | – | – |

Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, and smoking status.

Two-tailed Fisher's Exact test.

Power = 0.657.

Power = 0.814.

Power = 0.811.

Power = 0.913.

3.3. Analysis of association between oxidative stress-related SNPs and migraine triggers

The most reported migraine triggering factors by the case subjects of the current study were stress (71.5%), alcohol (38.5%), sleep changes (33.0%), weather changes (26.2%), water deprivation (dehydration; 25.3%), and physical activity (19.0%). Since migraine triggers seem to be capable of generating oxidative stress, an association analysis of the investigated oxidative stress-related SNPs and migraine triggers was performed. Statistically significant associations were indicated for the CAT rs1001179 genetic variant with sleep [CT vs. CC + TT: ORadj 0.427 (0.222–0.821), padj = 0.011] and weather [TT vs. CT + CC: ORadj 3.164 (1.022–9.801), padj = 0.046] changes (Table 8); for the GSTP1 Val105/Val114 or “Grs1695T rs1138272” haplotype (GSTP1*C) with alcohol consumption [OR 2.929 (1.210–7.094), p = 0.013] (Table 9); and for the UCP2 rs660339 genetic variant with physical activity as triggering factor for migraine attacks [CC vs. CT + TT: ORadj 2.135 (1.046–4.358), padj = 0.037; C vs. T: OR 1.697 (0.994–2.899), p = 0.051; Table 10].

Table 8.

Association analysis of the CAT rs1001179 variant with migraine triggers.

| Sleep changes | GG | (%) | GA | (%) | AA | (%) | OR (95% CI) | p | ORadj (95% CI)* | padj * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 71) | 46 | (64.8) | 17 | (23.9) | 8 | (11.3) | GG vs. GA vs. AA | - | 0.013 | - | 0.017 i |

| No (n = 131) | 69 | (52.7) | 56 | (42.7) | 6 | (4.6) | GG vs. GA + AA | 1.653 (0.911–2.999) | 0.097 | 1.604 (0.878–2.931) | 0.125 |

| G | (%) | A | (%) | AA vs. GA + GG | 2.646 (0.880–7.955) | 0.087** | 2.816 (0.923–8.593) | 0.069 | |||

| Yes (n = 142) | 109 | (76.8) | 33 | (23.2) | GA vs. GG + AA | 0.422 (0.221–0.804) | 0.008 | 0.427 (0.222–0.821) | 0.011 ii | ||

| No (n = 262) | 194 | (74.0) | 68 | (26.0) | G vs. A | 1.158 (0.718–1.866) | 0.547 | - | - | ||

| Weather changes | GG | (%) | GA | (%) | AA | (%) | |||||

| Yes (n = 57) | 32 | (56.1) | 18 | (31.6) | 7 | (12.3) | GG vs. GA vs. AA | 0.154 | 0.117iii | ||

| No (n = 145) | 83 | (57.2) | 55 | (37.9) | 7 | (4.8) | GG vs. GA + AA | 0.956 (0.515–1.774) | 0.887 | 0.964 (0.510–1.822) | 0.910 |

| G | (%) | A | (%) | AA vs. GA + GG | 2.760 (0.922–8.262) | 0.071** | 3.164 (1.022–9.801) | 0.046 iv | |||

| Yes (n = 114) | 82 | (71.9) | 32 | (28.1) | GA vs. GG + AA | 0.755 (0.394–1.449) | 0.398 | 0.717 (0.366–1.403) | 0.331 | ||

| No (n = 290) | 221 | (76.2) | 69 | (23.8) | G vs. A | 0.800 (0.490–1.306) | 0.372 | - | - |

Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, and smoking status.

Two-tailed Fisher's Exact test.

Bold values are considered statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Power = 0.975.

Power = 0.999.

Power = 0.975.

Power = 0.999.

Table 9.

Haplotype association analysis of the GSTP1 rs1138272 and rs1695 variants with alcohol as migraine trigger.

| Alcohol consumption | OR (95% CI) | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1695 | rs1138272 | Yes (%) | No (%) | |||||

| H1 | A | C | 105.00 | (69.1) | 169.00 | (76.1) | 0.701 (0.441–1.112) | 0.130 |

| H2 | G | C | 32.00 | (21.1) | 45.00 | (20.3) | 1.049 (0.630–1.745) | 0.854 |

| H3 | G | T | 15.00 | (9.9) | 8.00 | (3.6) | 2.929 (1.210–7.094) | 0.013 i |

Bold values are considered statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Power = 0.820.

Table 10.

Association analysis of the UCP2 rs660339 variant with physical activity as migraine trigger.

| Physical activity | CC | (%) | CT | (%) | TT | (%) | OR (95% CI) | p | ORadj (95% CI)* | padj * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 39) | 20 | (51.3) | 15 | (38.5) | 4 | (10.3) | CC vs. CT vs. TT | - | 0.110 | - | 0.111i |

| No (n = 159) | 53 | (33.3) | 80 | (50.3) | 26 | (16.4) | CC vs. CT + TT | 2.105 (1.036–4.279) | 0.037 | 2.135 (1.046–4.358) | 0.037 |

| C | (%) | T | (%) | TT vs. CT + CC | 0.585 (0.191–1.786) | 0.341 | 0.588 (0.189–1.826) | 0.358 | |||

| Yes (n = 78) | 55 | (70.5) | 23 | (29.5) | CT vs. CC + TT | 0.617 (0.302–1.263) | 0.184 | 0.599 (0.290–1.237) | 0.166ii | ||

| No (n = 318) | 186 | (58.5) | 132 | (41.5) | C vs. T | 1.697 (0.994–2.899) | 0.051 | - | - |

Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, and smoking status.

Bold values are considered statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Power = 0.441.

Power = 0.709.

4. Discussion

Cumulative evidence points toward migraine as a conserved adaptive response that ameliorates detrimental oxidative stress and rebalances energy homeostasis in the brain, associated with reproductive or survival advantages as signified by its high prevalence and its correlation with common genetic polymorphisms (11, 32). Besides several biochemical studies revealing diverse metabolic abnormalities in migraineurs, genetic studies assist the hypothesis that migraine patients show an increased vulnerability to oxidative stress, impaired mitochondrial functioning and/or metabolic derangements (11, 12). In addition, migraine often appears as a symptom to other oxidative stress associated concomitant diseases, such as brain tumors and fibromyalgia, further supporting an association between migraine and redox imbalance (33–36). Furthermore, oxidative stress seems to be a common metabolic denominator for the most frequently reported migraine triggers (13). Genetic susceptibility can contribute to decreased antioxidant capacity or increased oxidative stress (37). In the current study, it was hypothesized that an “oxidation predisposed” genetic make-up according to the investigated single nucleotide variants may be associated with the susceptibility to develop migraine and/or diverse clinical phenotypes and features. Thus, the current study analyzed the genotypic and allelic frequency distribution of eight genetic variants in oxidative-stress related proteins (rs4880-SOD2, rs1001179-CAT, rs1050450-GPX1, rs1695-GSTP1, rs1138272-GSTP1, rs1799983-NOS3, rs6721961-NFE2L2, and rs660339-UCP2) in clinically confirmed migraine subjects and a headache-free control group with SEC origin, in order to investigate their association with migraine susceptibility and diverse clinical phenotypes.

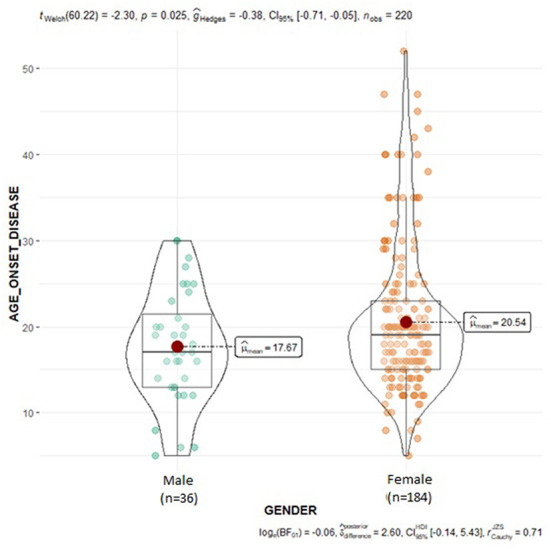

The NOS3 gene, encoding for endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) enzyme, is mapped on chromosome 7 (7q35–36) and consists of 26 exons (38). The rs1799983 missense variant in exon 7 of the NOS3 gene is a guanine (G) to thymine (T) replacement (G894T), resulting in the amino acid substitution Glu298Asp (39). This genetic variant may modify eNOS function and has been associated by some studies with decreased NO levels in carriers of the variant T (298Asp) allele (40–42). Borroni et al. suggested that eNOS Asp298 homozygosity is an independent risk factor for MwA (43), while subsequent studies found no association between rs1799983 variation and migraine susceptibility (37, 44–49). In addition, Eroz et al. observed that heterozygosity (GT) and homozygosity for the variant T allele (TT) were significantly more prevalent in migraineurs compared to control subjects (50). Although accordingly with most prior studies, no significant association between migraine susceptibility and rs1799983 variant was observed in the overall SEC population of the current study, subgroup analysis demonstrated that homozygosity for the more common G allele of the rs1799983 variant in the NOS3 gene seems to be associated with remarkably increased migraine susceptibility in the male population of the current study; thus, NOS3 rs1799983 may serve as an independent risk factor for migraine susceptibility in male population. Besides diverse ethnical background, the observed inconsistency of the findings concerning the association of the rs1799983 with migraine susceptibility may be attributable to the greater percentage of female participants in most studies due to the female preponderance of migraine; consequently, the results largely reflect the association of the NOS3 genetic variant with migraine in female population. Genetic influence seems to be more robust in male migraineurs, as suggested by findings from GWAS in migraine, probably due to the considerable environmental and hormonal effect on disease prevalence in females (27). The aforementioned data in addition to the evidence for an association between stronger migraine family history and lower age-at-onset (27), could also possibly explain the lower age-at-onset observed in male patients of the current study compared to female migraineurs (Figure 3). Furthermore, in the overall migraine population, the NOS3 rs1799983 variant T allele showed a trend of association with migraine attack duration longer than 24 h, with homozygous and heterozygous carriers of the variant T allele experiencing longer migraine attacks as compared to homozygous for the more common G allele. Likewise, in a study by Güler et al., the rs1799983 TT genotype was significantly more prevalent in patients with headache duration >24 h compared to patients with duration <24 h (51). Contrarily, no significant association of the NOS3 rs1799983 variant with attack duration was observed in a study by Eröz et al. (50).

Figure 3.

Violin plots displaying the mean age at disease onset in male and female migraine subjects.

The gene encoding for catalase (CAT), a crucial endogenous antioxidant enzyme which detoxifies hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), is located on chromosome 11 (11p13) (52). The rs1001179 (C262T) variant in the promoter region of the CAT gene causes alteration at the transcription factor binding site (53, 54). The variant T allele seems to confer enhanced transcriptional rate, while data concerning the influence of the rs1001179 on enzyme activity are controversial (55). Saygi et al. reported no significant differences in CAT rs1001179 genotype or allele frequency distribution among children and adolescents with MwA, MwoA, and controls (56). Similarly, Gentile et al. found no significant differences in genotype and allele frequencies between female chronic migraine population and healthy controls (37). Although not correlated to migraine and migraine subtypes per se, accordingly with previous studies, the rs1001179 variant in the CAT gene seems to delay disease onset in the migraine population of the current study; TT and CT genotypes were associated with a later age at onset, feasibly indicating a delayed migraine onset for the carriers of the variant T allele. In addition, homozygosity for the variant T allele of the CAT rs1001179 seems to be associated with sleep and weather changes as triggering factors inducing migraine attacks. Epidemiological data showed a correlation between early migraine onset and enhanced relative risk in first-degree relatives, indicating a genetic component in migraine onset (27). Therefore, the findings of the current study point toward CAT as a candidate disease modifying genetic factor.

The enzyme glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) is a major endogenous selenium-dependent antioxidant in defense against oxidative stress. The human GPX1 gene encoding for glutathione peroxidase is located on chromosome 3 (3p21) and contains the non-synonymous rs1050450 variant which is a C to T alteration in exon 2, resulting in an amino acid substitution from proline (Pro) to leucine (Leu) (57, 58). This genetic variant is associated with altered enzyme activity and may potentially influence a person's antioxidant capacity. In particular, the minor T (Leu) allele has been associated with decreased GPx1 activity (54, 59–61). To the author's knowledge, this is the first study investigating the relationship of the GPX1 rs1050450 variant and migraine phenotypes. The results of the current study indicated an association between GPX1 rs1050450 variant and migraine attack duration. In particular, a significantly more frequent prevalence of the variant T allele and TT homozygosity was observed in patients with longer attack duration (>24 h) compared to patients with shorter attack duration (≤24 h); thus, the presence of the variant T allele seems to be related with prolonged migraine attacks in the SEC migraine population of the study. A study by Alp et al. indicated a significant negative correlation between total thiol (-SH) levels and headache duration in patients with MwoA (62). Considering the correlation of the variant T allele with reduced GPX1 activity and the negative correlation of the total -SH levels with migraine attack duration, carriers of the T allele may experience longer attack duration due to reduced antioxidant capacity and thus reduced ability to neutralize oxidants possibly leading in prolonged migraine attacks.

Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) constitutes a family of phase II xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes that catalyze the conjugation of reduced glutathione (GSH) with hydrophobic electrophilic compounds to generate readily excretable or less toxic metabolites; thus, they can detoxify various harmful substances including reactive oxygen species (ROS) (63, 64). Several factors can influence the activity of this antioxidant enzyme including polymorphic genetic variants (65). The GSTP1 gene is located on chromosome 11 (11q13) (66). The most reported GSTP1 genetic variants are the rs1695; an A to G transition at nucleotide 313 resulting in an isoleucine (Ile) to valine (Val) substitution (I105V) in exon 5, and the rs1138272; a G to T transition at nucleotide 341 resulting in an alanine (Ala) to valine (Val) (A114V) substitution in exon 6. These genetic variants result in decreased enzyme activity and detoxification capacity of the protein (67, 68). The current study did not detect any significant association of the GSTP1 variants with the susceptibility to develop migraine or migraine subtypes and clinical phenotypes. Likewise, Gentile et al. found no significant association of the rs1645 variant with CM susceptibility (37). Nevertheless, a significant association of alcohol consumption reported as migraine trigger with the presence of the variant allele haplotype of GSTP1 rs1695 and rs1138272 [Val105/Val114 or Grs1695T rs1138272 (GSTP1*C) haplotype] was revealed in the migraine cohort of the current study. Alcohol consumption can increase brain oxidative stress through various mechanisms, mainly due to its metabolism by CYP2E1 enzyme and the subsequent production of ROS (69). The isoenzyme Glutathione S-Transferase Pi 1 (GSTP1) can promote brain detoxification and cell protection by modifying the effect of neurotoxins and OS products (70). The Val105/Val114 haplotype is associated with lower enzymatic activity leading to incomplete catabolization of toxicants and potentially to higher oxidative stress levels (67). Therefore, the investigated functional genetic variants, which result in the substitution of two amino acids in the enzyme active site altering its activity and therefore its antioxidant function (71), may render the brain more vulnerable to oxidative damage reinforced by alcohol consumption.

Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) is an anion transporter located in the inner mitochondrial membrane (72). UCP2 is widely expressed, including immune system and subcortical brain structures, and is involved in oxidative stress, cellular homeostasis, energy production, and cell survival. A major function of UCP2 is dissipating proton gradient energy and suppressing the generation of ROS (73, 74). UCP2 downregulation is associated with enhanced oxidative stress and inflammation (75). Hence, UCP2 acts protectively against cell death induced by ROS in the central nervous system (76). The UCP2 gene is located on chromosome 11 (11q13) (77). One of the most reported UCP2 variant is the missense variant rs660339 in exon 4, a C to T transition, resulting in an amino acid substitution at position 55 of the UCP2 (Ala55Val) which seems to modify the uncoupling degree and consequently protein activity (72). In particular, the Val/Val genotype has been associated with lower degree of uncoupling, increased metabolic efficiency, lesser fat oxidation, reduced energy expenditure, higher exercise efficiency, higher risk of obesity and diabetes, elevated atherogenic index, and greater weight loss compared to the Ala/Val and Ala/Ala genotypes (77, 78). UCP2 demonstrates tissue specific physiological effects as suggested by its tissue-specific regulation e.g., in the brain UCP2 functions as a regulator of oxidative stress. Therefore, the effects of UCP2 variants may be tissue depended (77). The results of the current study indicated no significant association of the UCP2 rs660339 variant with migraine susceptibility and clinical phenotypes. However, a significant association was revealed with physical activity as triggering factor for migraine attacks; CC (Ala/Ala) genotype and C (Ala) allele were significantly more prevalent among migraineurs reporting physical activity as migraine trigger. Ahmetov et al. suggested an association between the variant T (Val) allele and higher maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) (79, 80). Additionally, a large cross-sectional population-based study by Hagen et al. revealed an inverse correlation between peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) and migraine in adults aged between 20 and 50 years, with significantly enhancing prevalence of migraine with lower VO2peak. Furthermore, a strong association of physical activity with migraine aggravation was observed in adult subjects younger than 50 years-old in the lowest VO2peak quantile. Consequently, the authors suggested that the inverse relationship between headache and VO2peak may be elucidated by shared genetic predisposition factors between migraine and low VO2peak status (81). Taken together, the findings of the current study may indicate UCP2 gene as a candidate genetic factor predisposing to both migraine and low VO2peak, with homozygous patients for the UCP2 rs660339 wild-type C (Ala) allele reporting more frequently intense physical activity as migraine trigger possibly due to lower VO2peak levels. To the authors' knowledge, this is the first report investigating the association of the UCP2 rs660339 variant with migraine phenotypes and features. Further larger-scale studies estimating VO2max levels alongside the identification of the genotypic profile for the rs660339 variant and possibly additional variants in the UCP2 gene are needed to validate the findings of the current study.

Certain limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. Firstly, the study population was limited to SEC migraineurs and headache-free controls to avoid biased introduced by genetic variability within different populations, possibly rendering the findings relevant only for this specific population. Secondly, the sample size was relatively small, particularly in migraine subgroups, thus the effect of low frequency alleles might not be detected. Moreover, the functional implication of the investigated genetic variants on the encoded antioxidant proteins and other related biomarkers was not examined, restricting the acquisition of additional information. Finally, the current study examined only a limited number of oxidative stress-related SNPs. Since migraine is a multifactorial disease influenced by multiple genes, the combined role of the examined genes and other functional genes and loci in migraine susceptibility and clinical phenotypes in SEC and other populations needs to be further investigated.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the study provides supportive evidence for potential implication of OS-related SNPs in migraine susceptibility and associated clinical phenotypes and features, i.e., age-at-onset, attack duration, and migraine triggers, in a SEC case-control population. Migraine is a common multifactorial disorder with several small effect size genetic variants, together with environmental factors conferring disease susceptibility. Unraveling the genetic susceptibility of migraine phenotypes and features could potentially contribute to disease diagnosis, to more accurate understanding of disease pathophysiology, and eventually to the identification of novel targets for therapeutic treatment. An enigma although remains the magnitude of genetic susceptibility for migraine phenotypes and clinical features and if this is relevant for both genders to the same degree. While oxidative stress and genetic variability seem to play a key role in the pathophysiology of migraine, the precise link between these factors has not been fully understood yet. The current study examines for the first time the potential association of multiple common oxidative-stress related genetic variants with migraine susceptibility and clinical phenotypes in a SEC population. The possible association of certain OS-related genetic variants with migraine features indicated by the current study further supports the involvement of OS-related mechanisms in migraine pathophysiology. Nonetheless, larger-scale multicenter studies are needed to extend and further validate the current findings in SEC and other populations, considering gene-gene and gene environment interactions. The current findings could potentially assist in migraineurs risk stratification strategies and contribute to precision diagnosis and therapy of migraine.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Mediterraneo Hospital, Glyfada, Greece and University Hospital of Larissa Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MP conceptualized the study, performed the research and data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. MP and M-SK designed the experiments. ND supervised the study. MV, VS, EVD, and ED contributed to clinical data and specimen collection. MP and AK analyzed the specimens. ND, VS, and ED revised the study. AR revised the data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, Hoffmann J, Schankin C, Akerman S. Pathophysiology of migraine: A disorder of sensory processing. Physiol Rev. (2017) 97:553–622. 10.1152/physrev.00034.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashina M. Migraine. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:1866–76. 10.1056/NEJMra1915327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qubty W, Patniyot I. Migraine pathophysiology. Pediatr Neurol. (2020) 107:1–6. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society . The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. (2018) 38:1–211. 10.1177/0333102417738202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liampas I, Siokas V, Mentis AA, Aloizou A, Dastamani M, Tsouris Z, et al. Serum homocysteine, pyridoxine, folate, and vitamin B12 levels in migraine: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Headache J Head Face Pain. (2020) 60:1508–34. 10.1111/head.13892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodick DW. A phase-by-phase review of migraine pathophysiology. Headache J Head Face Pain. (2018) 58:4–16. 10.1111/head.13300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai J, Dilli E. Migraine aura: Updates in pathophysiology and management. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. (2020) 20:17. 10.1007/s11910-020-01037-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geyik S, Altunisik E, Neyal AM, Taysi S. Oxidative stress and DNA damage in patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. (2016) 17:10. 10.1186/s10194-016-0606-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan J, Asoom LI, Al Sunni A, Al Rafique N, Latif R, Saif S, et al. Genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, management, and prevention of migraine. Biomed Pharmacother. (2021) 139:111557. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernecker C, Ragginer C, Fauler G, Horejsi R, Möller R, Zelzer S, et al. Oxidative stress is associated with migraine and migraine-related metabolic risk in females. Eur J Neurol. (2011) 18:1233–9. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross EC, Lisicki M, Fischer D, Sándor PS, Schoenen J. The metabolic face of migraine—From pathophysiology to treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. (2019) 15:627–43. 10.1038/s41582-019-0255-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross EC, Putananickal N, Orsini AL, Vogt DR, Sandor PS, Schoenen J, et al. Mitochondrial function and oxidative stress markers in higher-frequency episodic migraine. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:1–12. 10.1038/s41598-021-84102-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borkum JM. Migraine triggers and oxidative stress: A narrative review and synthesis. Headache J Head Face Pain. (2016) 56:12–35. 10.1111/head.12725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honkasalo ML, Kaprio J, Winter T, Heikkilä K, Sillanpää M, Koskenvuo M. Migraine and concomitant symptoms among 8167 adult twin pairs. Headache J Head Face Pain. (1995) 35:70–8. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3502070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulder EJ, Van Baal C, Gaist D, Kallela M, Kaprio J, Svensson DA, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on migraine: A twin study across six countries. Twin Res. (2003) 6:422–31. 10.1375/136905203770326420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ducros A. Genetics of migraine. Rev Neurol. (2021) 177:801–8. 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutherland HG, Griffiths LR. Genetics of migraine: Insights into the molecular basis of migraine disorders. Headache J Head Face Pain. (2017) 57:537–69. 10.1111/head.13053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siokas V, Liampas I, Aloizou A-M, Papasavva M, Bakirtzis C, Lavdas E, et al. Deciphering the role of the rs2651899, rs10166942, and rs11172113 polymorphisms in migraine: A meta-analysis. Medicina. (2022) 58:40491. 10.3390/medicina58040491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Boer I, Van Den Maagdenberg AMJM, Terwindt GM. Advance in genetics of migraine. Curr Opin Neurol. (2019) 32:413–21. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Den Maagdenberg AMJM, Nyholt DR, Anttila V. Novel hypotheses emerging from GWAS in migraine? J. Headache Pain. (2019) 20:956. 10.1186/s10194-018-0956-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anttila V, Stefansson H, Kallela M, Todt U, Terwindt GM. Genome-wide association study of migraine implicates a common susceptibility variant on 8q22.1. Nat Genet. (2010) 42:869–73. 10.1038/ng.652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anttila V, Winsvold BS, Gormley P, Kurth T, Bettella F, McMahon G, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat Genet. (2013) 45:912–7. 10.1038/ng.2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freilinger T, Anttila V, de Vries B, Malik R, Kallela M, Terwindt GM, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies susceptibility loci for migraine without aura. Nat Genet. (2012) 44:777–82. 10.1038/ng.2307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persico AM, Verdecchia M, Pinzone V, Guidetti V. Migraine genetics: Current findings and future lines of research. Neurogenetics. (2015) 16:77–95. 10.1007/s10048-014-0433-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gormley P, Anttila V, Winsvold BS, Palta P, Esko T, Pers TH, et al. Meta-analysis of 375,000 individuals identifies 38 susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat Genet. (2016) 48:856–66. 10.1038/ng.3598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hautakangas H, Winsvold BS, Ruotsalainen SE, Bjornsdottir G, Harder AVE, Kogelman LJA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of 102,084 migraine cases identifies 123 risk loci and subtype-specific risk alleles. Nat Genet. (2022) 54:152–60. 10.1038/s41588-021-00990-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelzer N, Louter MA, van Zwet EW, Nyholt DR, Ferrari MD, van den Maagdenberg AMJM, et al. Linking migraine frequency with family history of migraine. Cephalalgia. (2019) 39:229–36. 10.1177/0333102418783295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsarou M, Giakoumaki M, Papadimitriou A, Demertzis N, Androutsopoulos V, Drakoulis N. Genetically driven antioxidant capacity in a Caucasian Southeastern European population. Mech Ageing Dev. (2017) 172:1–5. 10.1016/j.mad.2017.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Day INM. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing of biological ascertainment for mendelian randomization studies. Am J Epidemiol. (2009) 169:505–14. 10.1093/aje/kwn359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi YY, He L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. (2005) 15:97–8. 10.1038/sj.cr.7290272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z, Zhang Z, He Z, Tang W, Li T, Zeng Z, et al. A partition-ligation-combination-subdivision EM algorithm for haplotype inference with multiallelic markers: Update of the SHEsis (http://analysis.bio-x.cn). Cell Res. (2009) 19:519–23. 10.1038/cr.2009.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loder E. What is the evolutionary advantage of migraine? Cephalalgia. (2002) 22:624–32. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cordero MD, Cano-García FJ, Alcocer-Gómez E, De Miguel M, Sánchez-Alcázar JA. Oxidative stress correlates with headache symptoms in fibromyalgia: Coenzyme Q10 effect on clinical improvement. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e35677. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C-H, Sheu J-J, Lin Y-C, Lin H-C. Association of migraines with brain tumors: A nationwide population-based study. J Headache Pain. (2018) 19:111. 10.1186/s10194-018-0944-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matschke V, Theiss C, Matschke J. Oxidative stress: The lowest common denominator of multiple diseases. Neural Regen Res. (2019) 14:238. 10.4103/1673-5374.244780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genc S, Pennisi M, Yeni Y, Yildirim S, Gattuso G, Altinoz MA, et al. Potential neurotoxic effects of glioblastoma-derived exosomes in primary cultures of cerebellar neurons via oxidant stress and glutathione depletion. Antioxidants. (2022) 11:1225. 10.3390/antiox11071225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gentile G, Negro A, D'Alonzo L, Aimati L, Simmaco M, Martelletti P, et al. Lack of association between oxidative stress-related gene polymorphisms and chronic migraine in an Italian population. Expert Rev Neurother. (2015) 15:215–25. 10.1586/14737175.2015.1001748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marsden PA, Heng HHQ, Scherer SW, Stewart RJ, Hall AV, Shi XM, et al. Structure and chromosomal localization of the human constitutive endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene. J Biol Chem. (1993) 268:17478–88. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85359-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joshi MS, Mineo C, Shaul PW, Bauer JA. Biochemical consequences of the NOS3 Glu298Asp variation in human endothelium: Altered caveolar localization and impaired response to shear. FASEB J. (2007) 21:2655–63. 10.1096/fj.06-7088com [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Funke S, Risch A, Nieters A, Hoffmeister M, Stegmaier C, Seiler CM, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in genes related to oxidative stress (GSTP1, GSTM1, GSTT1, CAT, MnSOD, MPO, eNOS) and survival of rectal cancer patients after radiotherapy. J Cancer Epidemiol. (2009) 2009:1–6. 10.1155/2009/302047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yanar K, Çakatay U, Aydin S, Verim A, Atukeren P, Özkan NE, et al. Relation between endothelial nitric oxide synthase genotypes and oxidative stress markers in larynx cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2016) 2016:1–8. 10.1155/2016/4985063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo Z, Jia A, Lu Z, Muhammad I, Adenrele A, Song Y. Associations of the NOS3 rs1799983 polymorphism with circulating nitric oxide and lipid levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med J. (2019) 95:361–71. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-136396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borroni B, Rao R, Liberini P, Venturelli E, Cossandi M, Archetti S, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (Glu298Asp) polymorphism is an independent risk factor for migraine with aura. Headache. (2006) 46:1575–9. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00614.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toriello M, Oterino A, Pascual J, Castillo J, Colás R, Alonso-Arranz A, et al. Lack of association of endothelial nitric oxide synthase polymorphisms and migraine. Headache. (2008) 48:1115–9. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacClellan LR, Howard TD, Cole JW, Stine OC, Giles WH, O'Connell JR, et al. Relation of candidate genes that encode for endothelial function to migraine and stroke. Stroke. (2009) 40:1–18. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.557462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schürks M, Kurth T, Buring JE, Zee RYL. A candidate gene association study of 77 polymorphisms in migraine. J Pain. (2009) 10:759–66. 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.01.326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gruber HJ, Bernecker C, Lechner A, Weiss S, Wallner-Blazek M, Meinitzer A, et al. Increased nitric oxide stress is associated with migraine. Cephalalgia. (2010) 30:486–92. 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01964.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonçalves FM, Martins-Oliveira A, Speciali JG, Luizon MR, Izidoro-Toledo TC, Silva PS, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase haplotypes associated with aura in patients with migraine. DNA Cell Biol. (2011) 30:363–9. 10.1089/dna.2010.1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonçalves FM, Luizon MR, Speciali JG, Martins-Oliveira A, Dach F, Tanus-Santos JE. Interaction among nitric oxide (NO)-related genes in migraine susceptibility. Mol Cell Biochem. (2012) 370:183–9. 10.1007/s11010-012-1409-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eröz R, Bahadir A, Dikici S, Tasdemir S. Association of endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms (894G/T,−786T/C, G10T) and clinical findings in patients with migraine. Neuromolecular Med. (2014) 16:587–93. 10.1007/s12017-014-8311-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Güler S, Gürkan H, Tozkir H, Turan N, Çelik Y. An investigation of the relationship between the enos gene polymorphism and diagnosed migraine. Balk J Med Genet. (2014) 17:49–59. 10.2478/bjmg-2014-0074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang C-D, Sun Y, Chen N, Huang L, Huang J-W, Zhu M, et al. The role of catalase C262T gene polymorphism in the susceptibility and survival of cancers. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:26973. 10.1038/srep26973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu K, Liu X, Wang M, Wang X, Kang H, Lin S, et al. Two common functional catalase gene polymorphisms (rs1001179 and rs794316) and cancer susceptibility: Evidence from 14,942 cancer cases and 43,285 controls. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:62954–65. 10.18632/oncotarget.10617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ayuso P, García-Martín E, Agúndez JAG. Variability of the genes involved in the cellular redox status and their implication in drug hypersensitivity reactions. Antioxidants. (2021) 10:1–24. 10.3390/antiox10020294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saify K, Saadat I, Saadat M. Influence of A-21T and C-262T genetic polymorphisms at the promoter region of the catalase (CAT) on gene expression. Environ Health Prev Med. (2016) 21:382–6. 10.1007/s12199-016-0540-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saygi S, Erol I, Alehan F, Yalçln YY, Kubat G, Ataç FB. Superoxide dismutase and catalase genotypes in pediatric migraine patients. J Child Neurol. (2015) 30:1586–90. 10.1177/0883073815575366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.da Rocha TJ, Silva Alves M, Guisso CC, de Andrade FM, Camozzato A, de Oliveira AA, et al. Association of GPX1 and GPX4 polymorphisms with episodic memory and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. (2018) 666:32–7. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teimoori B, Moradi-shahrebabak M, Razavi M, Rezaei M, Harati-Sadegh M, Salimi S. The effect of GPx-1 rs1050450 and MnSOD rs4880 polymorphisms on PE susceptibility: A case- control study. Mol Biol Rep. (2019) 46:6099–104. 10.1007/s11033-019-05045-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jablonska E, Gromadzinska J, Reszka E, Wasowicz W, Sobala W, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, et al. Association between GPx1 Pro198Leu polymorphism, GPx1 activity and plasma selenium concentration in humans. Eur J Nutr. (2009) 48:383–6. 10.1007/s00394-009-0023-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang TS, Prior SL, Li KW, Ireland HA, Bain SC, Hurel SJ, et al. Association between the rs1050450 glutathione peroxidase-1 (C > T) gene variant and peripheral neuropathy in two independent samples of subjects with diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2012) 22:417–25. 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dragicevic B, Suvakov S, Jerotic D, Reljic Z, Djukanovic L, Zelen I, et al. Association of SOD2 (rs4880) and GPX1 (rs1050450) gene polymorphisms with risk of balkan endemic nephropathy and its related tumors. Medicina. (2019) 55:435. 10.3390/medicina55080435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alp R, Selek S, Alp SI, Taşkin A, Koçyigit A. Oxidative and antioxidative balance in patients of migraine. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2010) 14:877–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao H, Liu C, Song S, Zhang C, Ma Q, Li X, et al. GPX1 Pro198Leu polymorphism and GSTP1 Ile105Val polymorphisms are not associated with the risk of schizophrenia in the Chinese Han population. Neuroreport. (2017) 28:969–72. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yan H, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Liu J, Jin L, Pang Y, et al. Associations of AHR, CYP1A1, EPHX1, and GSTP1 genetic polymorphisms with small-for-gestational-age infants. J Matern Neonatal Med. (2019) 34:2807–15. 10.1080/14767058.2019.1671336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y, Sun LP, Xing CZ, Xu Q, He CY, Li P, et al. Interaction between GSTP1 Val Allele and H. pylori infection, smoking and alcohol consumption and risk of gastric cancer among the Chinese population. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:1–7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang S, Zhang J, Jun F, Bai Z. Glutathione S-transferase pi 1 variant and squamous cell carcinoma susceptibility: A meta-analysis of 52 case-control studies. BMC Med Genet. (2019) 20:22. 10.1186/s12881-019-0750-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vibhuti A, Arif E, Deepak D, Singh B, Qadar Pasha MA. Genetic polymorphisms of GSTP1 and mEPHX correlate with oxidative stress markers and lung function in COPD. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2007) 359:136–42. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Safarinejad MR, Dadkhah F, Asgari MA, Hosseini SY, Kolahi AA, Iran-Pour E. Glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms (GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1) and male factor infertility risk a pooled analysis of studies. Urol J. (2012) 9:541–8. 10.22037/uj.v9i3.1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mansoori AA, Jain SK. Molecular links between alcohol and tobacco induced DNA damage, gene polymorphisms and patho-physiological consequences: A systematic review of hepatic carcinogenesis. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. (2015) 16:4803–12. 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.12.4803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Sousa Barros JB, de Faria Santos K, Azevedo RM, de Oliveira RPD, Leobas ACD, da Cruz Pereira Bento D, et al. No association of GSTP1 rs1695 polymorphism with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A case-control study in the Brazilian population. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:1–15. 10.1371/journal.pone.0247024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Burim RV. Polymorphisms in glutathione S-transferases GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 and cytochromes P450 CYP2E1 and CYP1A1 and susceptibility to cirrhosis or pancreatitis in alcoholics. Mutagenesis. (2004) 19:291–8. 10.1093/mutage/geh034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heise V, Zsoldos E, Suri S, Sexton C, Topiwala A, Filippini N, et al. Uncoupling protein 2 haplotype does not affect human brain structure and function in a sample of community-dwelling older adults. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0181392. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bechmann I, Diano S, Warden CH, Bartfai T, Nitsch R, Horvath TL. Brain mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2): A protective stress signal in neuronal injury. Biochem Pharmacol. (2002) 64:363–7. 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01166-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li J, Jiang R, Cong X, Zhao Y. UCP2 gene polymorphisms in obesity and diabetes, and the role of UCP2 in cancer. FEBS Lett. (2019) 593:2525–34. 10.1002/1873-3468.13546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou Y, Simmons D, Hambly BD, McLachlan CS. Interactions between UCP2 SNPs and telomere length exist in the absence of diabetes or pre-diabetes. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:33147. 10.1038/srep33147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hass DT, Barnstable CJ. Uncoupling protein 2 in the glial response to stress: Implications for neuroprotection. Neural Regen Res. (2016) 11:1197–200. 10.4103/1673-5374.189159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rose G, Crocco P, de Rango F, Montesanto A, Passarino G. Further support to the uncoupling-to-survive theory: The genetic variation of human UCP genes is associated with longevity. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:1–7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gamboa R, Huesca-Gómez C, López-Pérez V, Posadas-Sánchez R, Cardoso-Saldaña G, Medina-Urrutia A, et al. The UCP2−866G/A, Ala55Val and UCP3-55C/T polymorphisms are associated with premature coronary artery disease and cardiovascular risk factors in Mexican population. Genet Mol Biol. (2018) 41:371–8. 10.1590/1678-4685-gmb-2017-0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ahmetov II, Popov DV, Astratenkova IV, Druzhevskaya AM, Missina SS, Vinogradova OL, et al. The use of molecular genetic methods for prognosis of aerobic and anaerobic performance in athletes. Hum Physiol. (2008) 34:338–42. 10.1134/S0362119708030110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ahmetov II, Fedotovskaya ON. Current Progress in Sports Genomics. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc. (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hagen K, Wisløff U, Ellingsen Ø, Stovner LJ, Linde M. Headache and peak oxygen uptake: The HUNT3 study. Cephalalgia. (2016) 36:437–44. 10.1177/0333102415597528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.