Abstract

Currently, there is a substantial research effort to develop near-infrared fluorescent polymethine cyanine dyes for biological imaging and sensing. In water, cyanine dyes with extended conjugation are known to cross over the “cyanine limit” and undergo a symmetry breaking Peierls transition that favors an unsymmetric distribution of π-electron density and produces a broad absorption profile and low fluorescence brightness. This study shows how supramolecular encapsulation of a newly designed series of cationic, cyanine dyes by cucurbit[7]uril (CB7) can be used to alter the π-electron distribution within the cyanine chromophore. For two sets of dyes, supramolecular location of the surrounding CB7 over the center of the dye favors a nonpolar ground state, with a symmetric π-electron distribution that produces a sharpened absorption band with enhanced fluorescence brightness. The opposite supramolecular effect (i.e., broadened absorption and partially quenched fluorescence) is observed with a third set of dyes because the surrounding CB7 is located at one end of the encapsulated cyanine chromophore. From the perspective of enhanced near-infrared bioimaging and sensing in water, the results show how that the principles of host/guest chemistry can be employed to mitigate the “cyanine limit” problem.

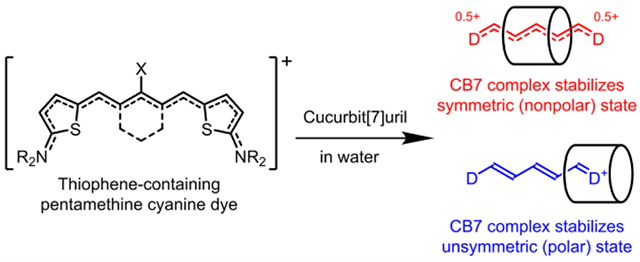

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Compared to visible wavelengths, fluorescence bioimaging in the first near-infrared (NIR I) window of 600 – 900 nm leads to improved performance due to deeper penetration of the light and reduced background signal.1,2 Currently, there is intense research activity to develop camera technology and complementary fluorescent molecular probes for effective operation in the longer near-infrared wavelength region beyond 900 nm (often called NIR-II) where tissue penetration and image contrast is even better.3–6 Roughly speaking, three distinct molecular design strategies have been explored to create organic fluorescent dyes that emit in the NIR-II window: a) donor-acceptor dyes possessing large Stokes shift due to intramolecular charge transfer in the excited state;7,8 b) fluorescent J-aggregates with bathochromic shifts in absorption and emission bands;9,10 c) novel dye chromophores with extended conjugation of π-electrons.11,12 The precise chemical and photophysical performance properties for these future next-generation dyes is determined by the specific demands of the application. Many imaging cases need the highest possible fluorescence brightness, which is a major challenge since fluorescence quantum yields of NIR-II dyes are limited by the energy gap law (often below 1%).13 Alternatively, many sensing or diagnostics applications require molecular strategies to modulate the absorption/emission wavelength or the fluorescence brightness.14 In addition to photophysical performance, in vivo imaging methods require molecular probes with specific physicochemical and biodistribution profiles.15 The simultaneous optimization of these interconnected dye properties is often pursued by conducting an iterative cycle of synthetic modification and testing experiments, a process that can potentially consume large amounts of time and resources.12,16 In this regard, the technical simplicity of dye modification strategies based on non-covalent assembly is quite attractive.17–19

Cyanines are popular fluorescent dyes with a cationic polymethine chromophore and tunable wavelengths.20 The most common cyanine dyes are known commercially and informally as Cy3, Cy5 or Cy7, and there is considerable understanding of the structural factors that control the distribution of π-electrons in the molecular orbital ground and excited states.21,22 In nonpolar solvents, a nonpolar ground state is favored with a symmetric distribution of π-electron density, delocalized positive charge, and close to zero bond length alternation along the polymethine chain (Scheme 1). This nonpolar state favors sharp absorption bands (the transition involves low vibronic coupling) and relatively bright fluorescence. Cyanine dyes with more than seven methines (i.e., beyond Cy7) are known to cross over the “cyanine limit” and undergo a symmetry breaking Peierls transition that favors a ground state with an unsymmetric distribution of π-electron density, localized positive charge, and substantial bond length alternation along the polymethine chain.22,23 A spectral characteristic of this polar, unsymmetric cyanine state is a broad charge-transfer type absorption band in polar solvents like water,11,24 or when there is tight ion-paring with small counter-anions.25,26 The Peierls transition explains why unsymmetric cyanine chromophores exhibit broader absorption bands and lower fluorescence quantum yields compared to symmetrical counterparts.27–29 Since the Peierls transition is energetically favored in water, the “cyanine limit” is a major molecular design roadblock that inhibits ongoing efforts to prepare effective next generation, NIR-II fluorescent cyanine dyes for biomedical imaging and diagnostics.

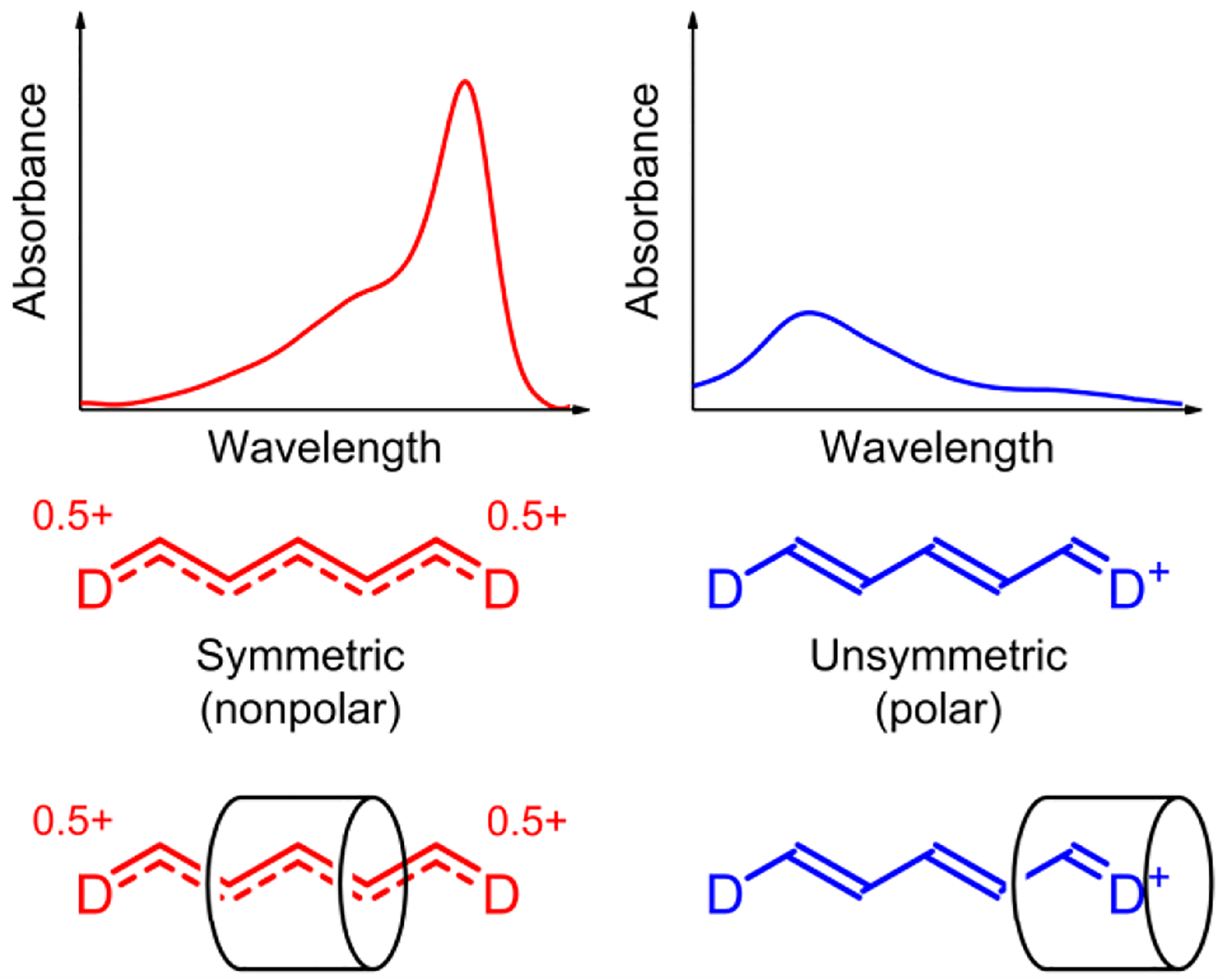

Scheme 1.

(left) Cyanine dye or dye/CB7 complex in a nonpolar state, with a symmetric π-electron distribution and delocalized positive charge, exhibits a relatively sharp and red-shifted absorption band. (right) Cyanine dye or dye/CB7 complex in a polar state, with an unsymmetric π-electron distribution and localized positive charge, exhibits a relatively broad and blue-shifted absorption band

At present, the most common literature method to circumvent the “cyanine limit” in water is to load the dye within the hydrophobic core of self-assembled micelles or related core-shell nanoparticles which reduces the dielectric constant of the microenvironment.30,31 We reasoned that a similar, or even more explicit, reconfiguration of the dye’s solvation sphere might be gained by cyanine dye encapsulation within a rigid, molecular container that has matching spatial dimensions and electrostatic surface.32,33 We were drawn to cucurbit[7]uril (CB7, Scheme 2) as a promising container molecule for NIR cyanine dyes for several reasons. First, CB7 has a symmetric cylinder shape and hydrophobic cavity that can accommodate a cyanine polymethine chain and protect it from the surrounding aqueous solvent. Second, the fixed array of seven polar carbonyl groups at each portal of CB7 can strongly stabilize an encapsulated cationic cyanine dye by cation-dipole interactions. Since cyanine dyes exhibit high polarizability, we expected the rigid, electrostatic surface of a surrounding CB7, which has very low polarizability, to strongly influence the distribution of π-electrons within an encapsulated cyanine dye (Scheme 1).34,35

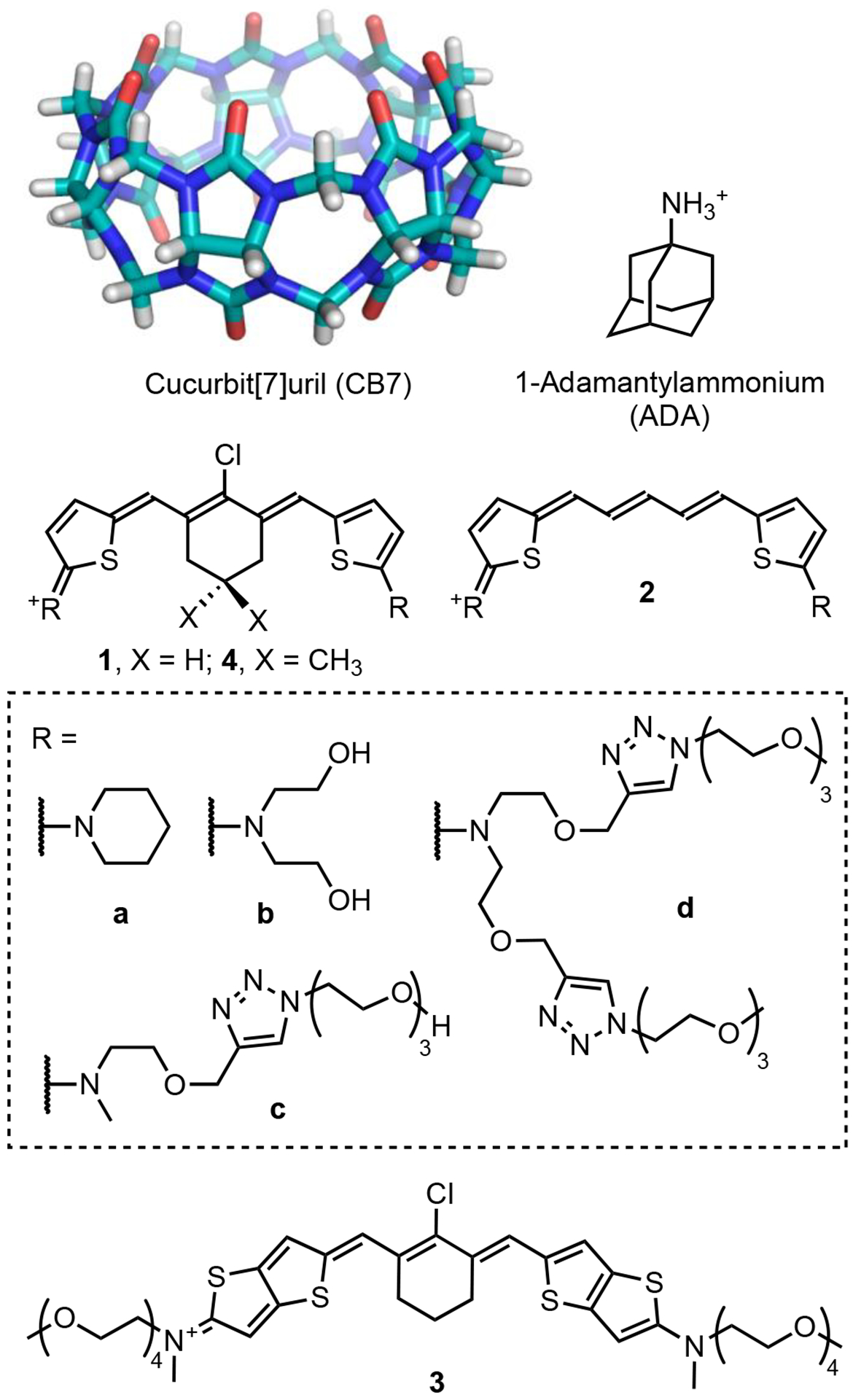

Scheme 2.

Molecules used in this study

While CB7 is known to encapsulate a range of different organic dye structures,36–38 there are very few examples of cyanine dye encapsulation.39 This is because most polymethine cyanine dyes have relatively bulky heterocyclic rings at each end of the chromophore that block dye penetration into the CB7 cavity. Thus, our first molecular design challenge was to devise a cationic polymethine cyanine dye structure with: (a) enough conjugation to produce NIR-I or NIR-II absorption/emission bands, and (b) small enough terminal groups to penetrate the CB7 cavity. We reasoned that the cyanine chromophores in Scheme 2 with 2-aminothiophene and 2-aminothienothiophene end groups would likely satisfy both criteria.40–42 Formally these cyanine dye structures are Cy5 derivatives with a stretch of five methine units, but the extended conjugation provided by the terminal 2-aminothiophene heterocycles lowers the HOMO-LUMO gap such that the absorption/emission wavelengths are substantially red-shifted and occur at the typical wavelengths of Cy7 derivatives.43

The study examined three related cyanine structures. The dyes series 1 and 2 have the same terminal 2-aminothiophene groups which provide very similar Cy7 absorption and emission wavelengths. The homologue 1 differs from 2 by having a central chlorocyclohexenyl ring that increases dye hydrophobicity and enhances threading of the CB7 macrocycle. Cyanine dye 3 also has a central chlorocyclohexenyl ring for strong encapsulation by CB7 and terminal 2-aminothienothiophene groups that extend the chromophore conjugation and move the absorption and emission wavelengths into the NIR-II window. Our studies show, for the first time, how cyanine threading of CB7 can be used to alter the distribution of π-electrons within the cyanine chromophore. From the perspective of enhanced NIR-II bioimaging in water, the results suggests that the principles of host/guest chemistry can be employed to mitigate the “cyanine limit” problem.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis.

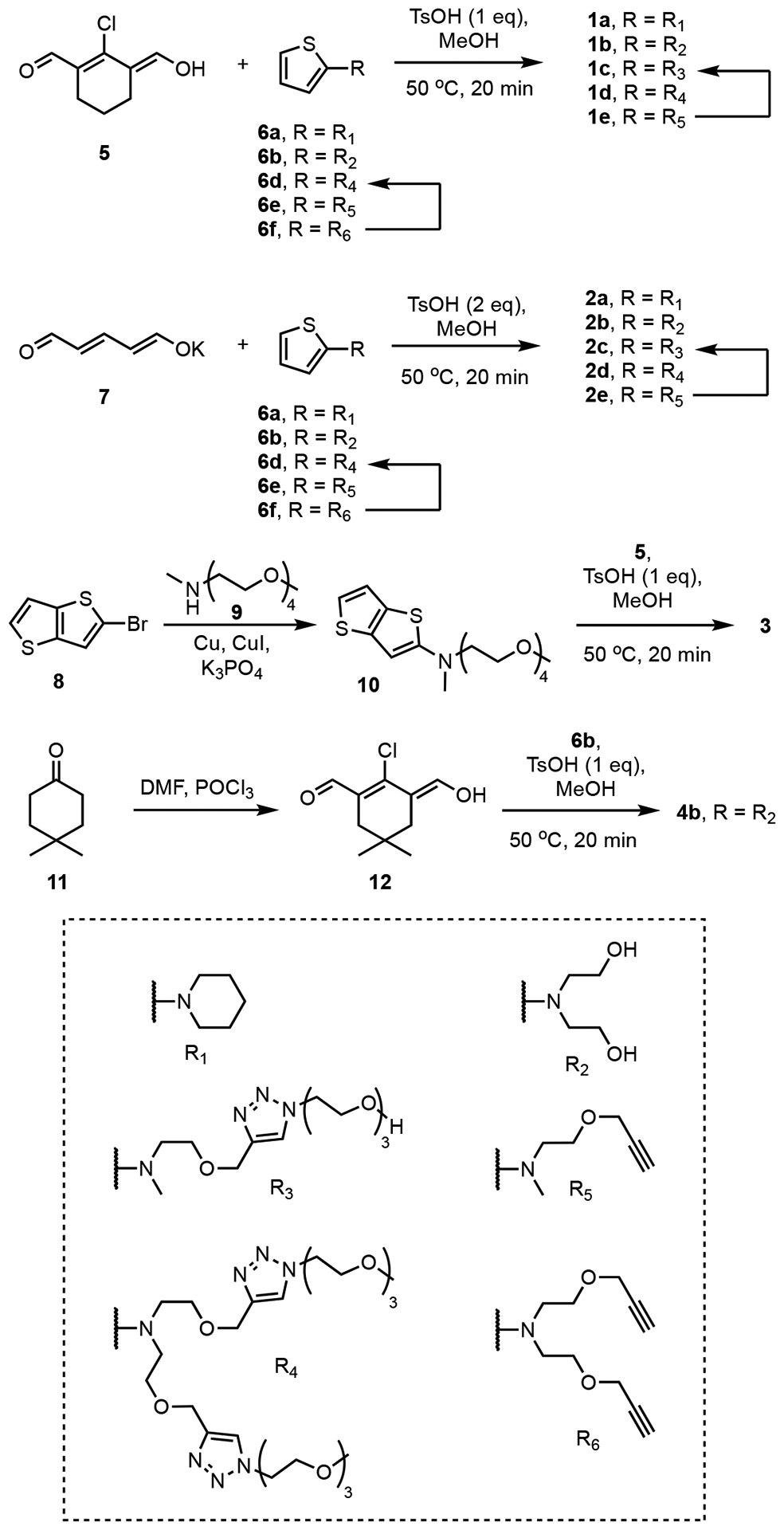

The dyes were prepared in useful synthetic yields by condensation of the appropriate of Vilsmeier-Haack reagent (5, 7 or 12) with 2-aminothiophene derivative 6 (or 2-aminothienothiophene derivative 10) under acidic condition (Scheme 3).40,41,44,45 Each compound was characterized by NMR, mass spectrometry, absorption, and fluorescence spectroscopy. The dyes 1, 2, 3 and 4 with the oxygen-containing terminal chains (R2, R3, R4) were soluble in different solvents ranging from highly polar water to nonpolar dichloromethane (DCM), which enabled solvatochromism studies. 1H NMR spectra in various solvents showed symmetrical spectral patterns at room temperature, and 1H,1H-ROESY spectra for the organic soluble compounds 1a and 2a (Figure S1) were consistent with the molecular conformations shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of cyanine dyes. See Scheme 2 for the structures of compounds 1 – 4.

Dye Spectral Properties and Solvatochromism.

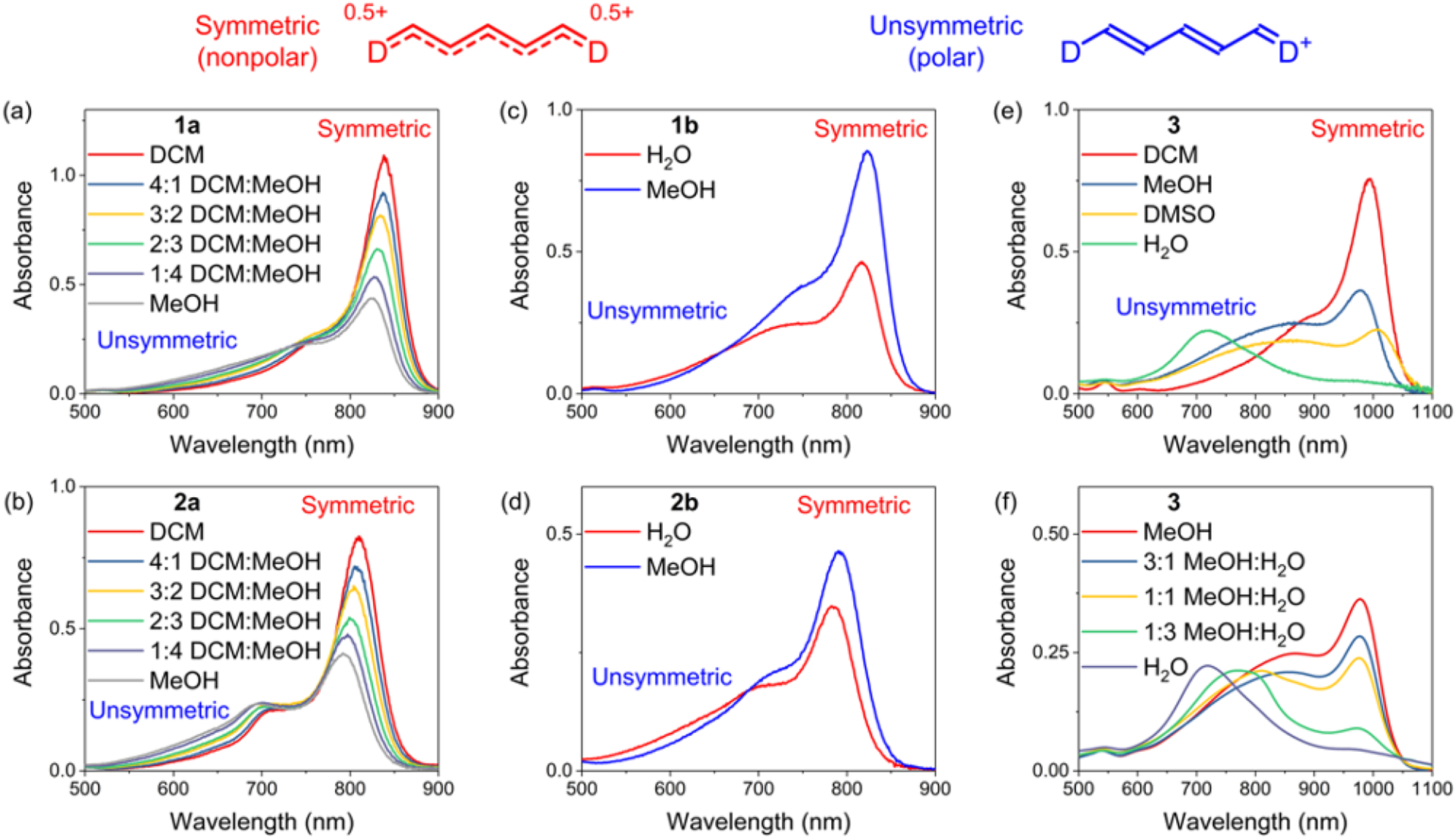

The organic soluble dyes 1a and 2a exhibited relatively sharp absorption bands in DCM with maxima wavelengths of 840 nm and 807 nm, respectively, along with a high-energy vibronic shoulder. With increased solvent polarity (increased percentage of methanol), the peak intensities at these maxima wavelengths (corresponding to a nonpolar state with symmetric distribution of π-electrons) decreased, and in 100% methanol they were about half the value in DCM (Figure 1a–b). Moreover, the increased solvent polarity produced a concomitant increase in absorption over the broad region of 550 – 750 nm (corresponding to a polar state with unsymmetric distribution of π-electrons). Likewise, a comparison of absorption spectra for dyes 1b-d and 2b-d in water and methanol showed the same solvatochromic behavior. That is, changing the solvent from methanol to more polar water produced a decrease in the long-wavelength absorption maxima (nonpolar state) and an increase in absorption from 550 – 750 nm for the polar state (Figure 1c–d and Figure S2, S3) along with a decrease in fluorescence emission intensity.46

Figure 1.

Solvatochromism studies in different solvents of (a) 1a (5 μM), (b) 2a (5 μM), (c) 1b (10 μM), (d) 2b (10 μM), (e and f) 3 (5 μM) at room temperature. The wavelength region in each spectrum, corresponding to a symmetric distribution of π-electrons (nonpolar state) or unsymmetric distribution of π-electrons (polar state), is labeled accordingly.

The extended chromophore dye 3 with terminal 2-aminothienothiophene groups also exhibited the same solvatochromic trend (Figure 1e–f). In DCM the absorption band was relatively narrow with a peak maxima at 992 nm (nonpolar state) and a fluorescence quantum yield of 0.43% which is comparable to many other organic-soluble NIR-II dyes.47,48 Increasing the solvent polarity produced absorption band broadening and a decrease in fluorescence quantum yield. In water the broad shape of the absorption band at 600 – 900 nm was unaltered by changes in dye concentration (Figure S4). Thus, the extensive absorption band broadening in water is not caused by dye self-aggregation, but is attributed to stabilization of a polar cyanine state with an unsymmetric distribution of π-electrons. Overall, cyanine dyes 1 – 3 exhibit the spectral hallmarks of the “cyanine limit” problem; most importantly, they are less fluorescent in polar solvents, especially water due, in large part, to solvent stabilization of an unsymmetric distribution of π-electrons.24,26

Binding Studies.

CB7 is known to have strong affinities in water for hydrophobic and cationic organic guests35 with a molecular shape that matches the dimensions of the CB7 cavity. CB7 threading by dyes 1, 2, and 3, in water was confirmed by independent measurements using absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and 1H NMR spectroscopy.

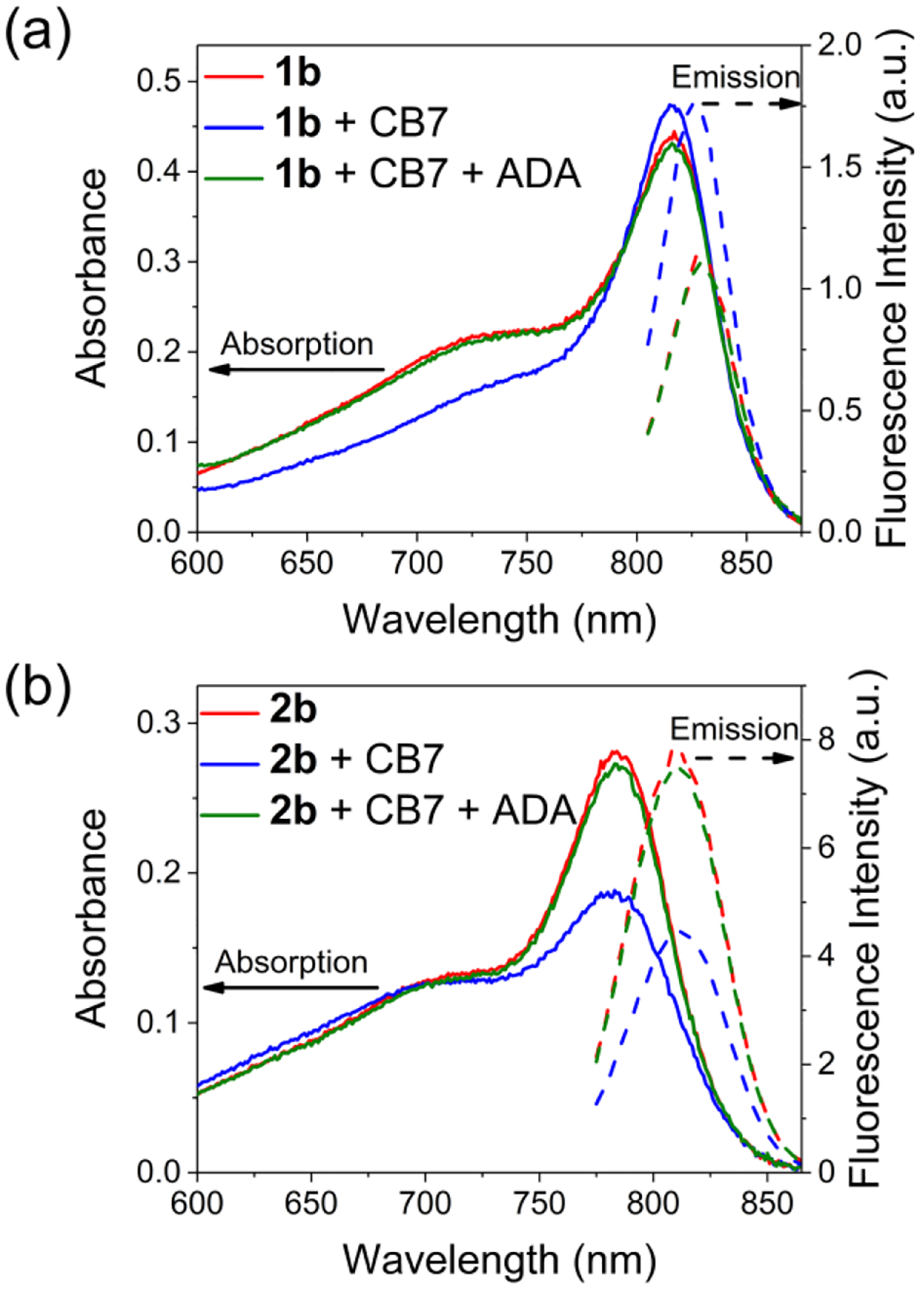

Absorbance and fluorescence titration experiments added aliquots of CB7 to separate solutions of 1b, 1c, 2b, or 2c in water. As shown by the representative absorbance spectra in Figure 2a, Figure S8 and S10, and the quantum yield data in Table 1, addition of CB7 to dye 1b or 1c in water induced the dye to adopt a more polar symmetric π-electron state with a corresponding 40% increase in dye fluorescence intensity. In complete contrast, addition of CB7 to 2b and 2c induced the dye to adopt a more nonpolar unsymmetric π-electron state with a corresponding decrease in dye fluorescence to 55% of the initial value (Figure 2b, Figure S9 and S11).

Figure 2.

Absorption (solid lines) and emission (dashed lines) spectra (5 μM, H2O, room temperature) of (a) 1b and (b) 2b upon adding CB7 (3 eq) and ADA (3 eq). For 1b, λex = 795 nm; for 2b, λex = 765 nm.

Table 1.

Fluorescence emission wavelength, quantum yield (ΦF) for the dyes and their CB7 complexes at room temperature

| Compound | Solvent | λemmax (nm) | ΦF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | H2O | 829 | 0.41 |

| 1b@CB7a | H2O | 827 | 0.53 |

| 2b | H2O | 810 | 2.3 |

| 2b@CB7a | H2O | 810 | 1.6 |

| 3 | DCM | 1043 | 0.43 |

| 3 | H2O | 985 | 0.12 |

| 3@CB7a | H2O | 979 | 0.23 |

Measured using mixture of dye and 3 molar equivalents of CB7.

Evidence that the difference in optical response was due to CB7 encapsulation of the dyes included the following experimental results:

In each case, the optical response was completely and rapidly reversed by displacement of the dye from the CB7 cavity. This was achieved by adding adamantylammonium cation (ADA, Scheme 2), a high affinity guest for CB7,49 to the CB7-dye mixture (Figure 2). The stoichiometry of the added ADA matched the molar amount of CB7.

Absorption and fluorescence experiments added CB7 to aqueous solutions of control dyes 1d and 2d which each have two appended triethylene glycol chains at each end of the dye structure that combined are sterically large enough to prevent threading of CB7. As shown in Figure S14, addition of CB7 produced no effect on the dye absorption or fluorescence profile.

Control absorption and fluorescence experiments added CB7 to an aqueous solution of modified dye 4b, an analogue of 1b with two extra methyl groups on the central chlorocyclohexenyl ring that prevent CB7 encapsulation of the molecular core. As shown in Figure S16, addition of CB7 had no effect on the dye absorption or fluorescence profile. This result strongly suggests that CB7 surrounds the center of dye 1b.

The possibility that CB7 binds the protonated form of the encapsulated dyes was ruled out by showing that the absorption spectrum of 1b in acidic buffer exhibits a band at 575 nm (Figure S17), that is absent in CB7 titration experiments.

1H NMR experiments showed that addition of CB7 to dye 1c in D2O produced moderate changes in chemical shift for some dye protons indicating encapsulation of 1c by CB7 (Figure S6).51,52 A very different change in 1H NMR spectrum was observed when CB7 was added to dye 2c in D2O. As shown in Figure S7, there was extensive broadening of the peaks for 2c, consistent with an unsymmetrical host/guest complex structure undergoing dynamic exchange.

Dyes 1b and 2b could not be studied by 1H NMR due to dye self-aggregation at the relatively high concentrations needed for NMR. However, mass spectra of samples containing a binary mixture of CB7 and 1b, or CB7 and 2b in water showed prominent peaks corresponding to 1:1 associated complexes 1a@CB7 and 2a@CB7 (Figure S13). In contrast, there was no mass spectrometry evidence for threading of CB7 by control dyes 1d and 2d with bulky terminal groups. That is, separate mass spectra of binary mixtures of CB7 and 1d, or CB7 and 2d in water showed no peaks corresponding to associated CB7/dye complexes (Figure S15).

The absorption titration experiments produced isotherms (Figure S7–S10) that closely matched a 1:1 binding model and enabled determination of association constants for dye encapsulation by CB7 (Table 2). The association constant for 1b ((1.2 × ± 0.3) 106 M−1) was about 14 times higher than 2b ((8.6 ± 0.8) × 104 M−1), and likewise 1c ((1.5 ± 0.2) × 106 M−1) was about 8 times higher than 2c ((1.6 ± 0.3) × 105 M−1). In both cases, the affinity trends matched the difference in dye hydrophobicity; CB7 affinities were significantly higher for the homologous dyes 1b and 1c whose structures each contain a central chlorocyclohexenyl ring that matches the shape and hydrophobicity of the CB7 cavity.

Table 2.

Association constants (Ka) of CB7 with cyanine dyes in H2O at 298 K, as determined by absorption titration experiments

| Dyes | Ka (M−1) |

|---|---|

| 1b | (1.2 ± 0.3) × 106 |

| 1c | (1.5 ± 0.2) × 106 |

| 2b | (8.6 ± 0.8) × 104 |

| 2c | (1.6 ± 0.3) × 105 |

| 3 | (2.0 ± 0.2) × 107 |

When the above the titrations experiments were repeated in phosphate buffered saline (1X, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), there was no spectral evidence for dye encapsulation by the CB7, in agreement with the well-known fact that sodium cations associate moderately strongly with the polar carbonyls at each portal of the CB7 and inhibit encapsulation of dyes.50,53 The photostability of these new cyanine dyes and dye/CB7 complexes was assessed by conducting simple photobleaching experiments. Separate aqueous solutions of dyes 1c, 2c, and their respective complexes 1c@CB7 and 2c@CB7, were irradiated by a 150 W Xenon lamp with a 620 nm long-pass filter (0.5 mW/cm2). The changes in dye absorbance (Figure S5) indicated moderate susceptibility to photobleaching which is not surprising because the two 2-aminothiophene units within each dye structure are known to react with photogenerated singlet oxygen.54 The surrounding CB7 hardly changed the rate of photobleaching, which is in contrast to the reports of moderate improvement in photostability when cyanine dyes are encaspulated by cyclodextrin.32,33 It is likely that future work could improve the photostabilities of dye series 1 or 2 by making judicious structural modifications of the terminal 2-aminothiophene units.54

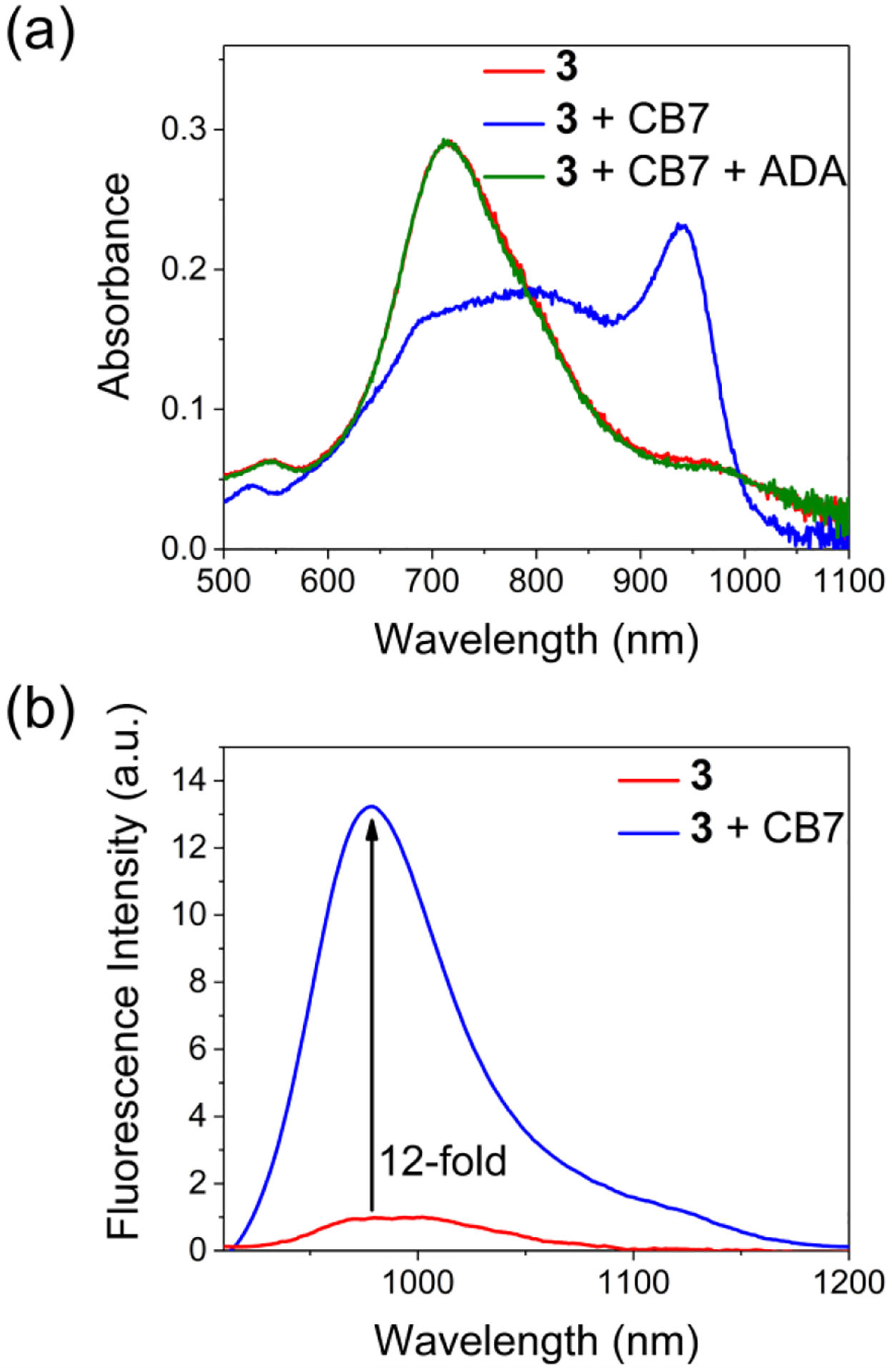

The structure of new cyanine dye 3 contains a chlorocyclohexenyl core and two 2-aminothienothiophene end groups that move the absorption/emission bands into the NIR-II region. Titration experiments (Figure S12) indicated that dye 3 threaded CB7 with 1:1 stoichiometry (confirmed by mass spectrometry, see Figure S13c) and a very high Ka value of (2.0 ± 0.2) × 107 M−1 that reflected the hydrophobic core of the dye molecule. The optical response was completely and rapidly reversed by adding ADA to displace 3 from the CB7 cavity (Figure 3a). Furthermore, encapsulation of cyanine 3 by CB7 produced a large increase in absorption intensity at the maxima wavelength of 940 nm, along with a 78% increase in the fluorescence quantum yield. These two factors combined to produce an impressive 12-fold increase in NIR-II fluorescence intensity at 979 nm (Figure 3b). Thus, CB7 encapsulation of 3 strongly stabilized the dye’s nonpolar, unsymmetric π-electron ground state and greatly increased the fluorescence brightness.

Figure 3.

(a) Absorption spectra indicating encapsulation of 3 (5 μM) by CB7 (1 eq) in H2O, at 298 K, and displacement of the encapsulated 3 by adding adamantylammonium (ADA, 1 eq) as a competing guest, (b) emission spectra of free 3 (5 μM in H2O, at 298 K, λex = 900 nm) and an equimolar admixture with CB7.

The unique impact of CB7 on dye optical properties was highlighted by a series of control experiments that tested some closely related macrocycles. Addition of β-cyclodextrin to separate aqueous solutions of each dye produced virtually no effect, indicating negligible dye encapsulation. Mixing dye 1c with γ-cyclodextrin produced a small decrease in the dye absorption and emission intensity (Figure S18). Whereas, mixing the more hydrophobic dye 3 with one molar equivalent of γCD produced a substantial change in the dye’s absorption spectrum, indicating strong supramolecular association. The encapsulation of 3 by unsymmetrical γCD induced a moderate red-shift of wavelength for the maximum absorption peak but the effect was much less than the red-shift induced by CB7 (Figure S19). It is apparent that the chromophore for encapsulated dye 3 is more polar and unsymmetrical when it is inside γCD, than when 3 is inside CB7.32

Molecular Structures of the CB7/Dye Complexes

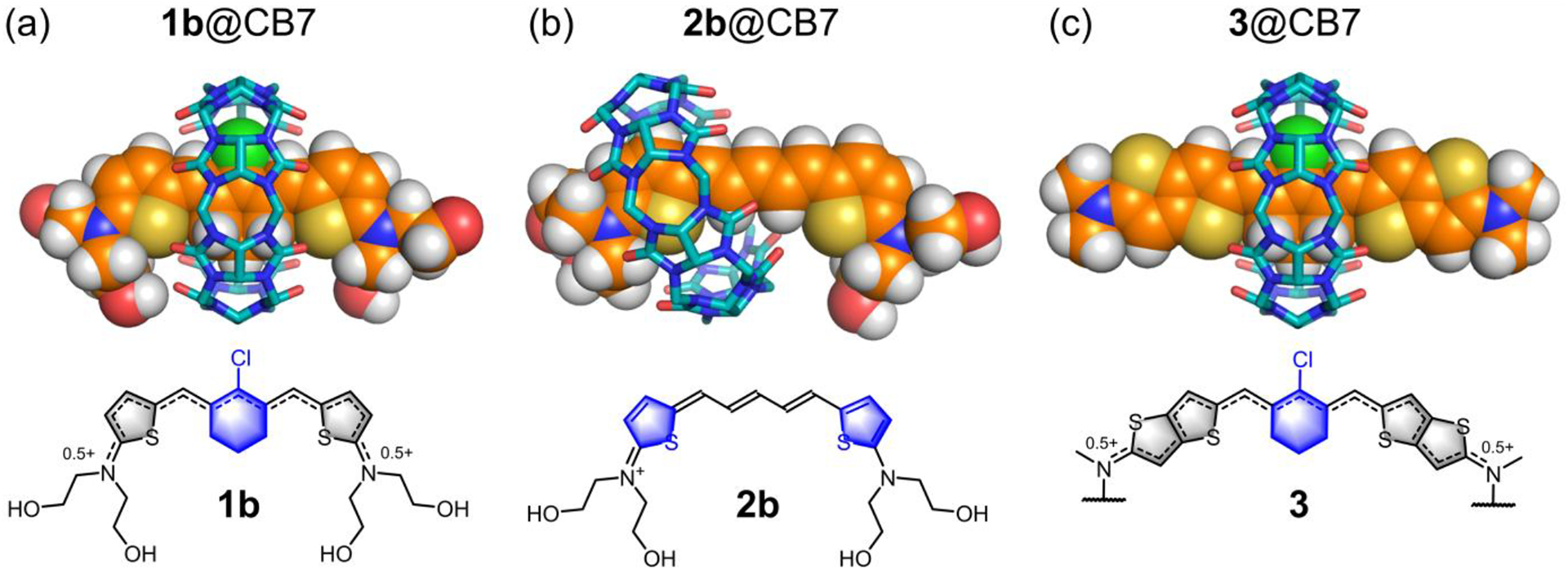

The affinity trend for CB7 threading by dyes 1, 2, and 3 correlates with the difference in dye hydrophobicity. That is, association constants were significantly higher for the dyes 1 and 3 whose structures contain a central chlorocyclohexenyl ring that matches the shape and hydrophobicity of the CB7 cavity. CB7 encapsulation of the central chlorocyclohexenyl ring is apparently the supramolecular process that enhances the fluorescence emission for 1 and 3, since no spectral change was observed when CB7 was added to dye 4, whose central chlorocyclohexenyl ring has two extra methyl groups that prevent penetration into the CB7 cavity (Figure S16). Multiple factors could possibly cause the complexation-induced changes in NMR chemical shift for 1c@CB7,52 therefore, the NMR data does not allow discernment between a complex that is primarily a single, relatively static structure or an ensemble average of interconverting co-conformational isomers.

The surrounding CB7 affects the dye photophysical properties in two ways. First, the CB7 sterically inhibits energy transfer from the dye excited state to the water solvation shell, with the expectation that supramolecular protection is highest when the CB7 is located over the core of the dye molecule.55–57 Second, the surrounding CB7 alters the distribution of π-electrons within an encapsulated cyanine dye. Additional detail concerning this second point was gained by examining computational models of the supramolecular complexes. Using density functional theory (DFT), local low-energy structures were generated for two limiting co-conformational isomers of 1c@CB7 and 2c@CB7, one isomer with the CB7 surrounding the center of the dye and the other with the CB7 positioned over one of the terminal thiophene units. We ignored the calculated energy values for two reasons, (a) the local low-energy supramolecular structures may not to be the global low-energy structures, and (b) the difference in interaction energies for a related pair of co-conformational isomers is likely to be much smaller than the uncertainty of the calculations. Rather, we focused on the difference in calculated dipole moments for the co-conformational isomers as a more meaningful output property of the calculations. As summarized in Table S3, the calculated dipole moment is much smaller for the co-conformational isomer that locates the surrounding CB7 over the center of the dye, consistent with a more symmetric distribution of π-electrons in the chromophore. Taken together, the experimental and calculational data strongly suggest that the changes in dye absorption and fluorescence properties upon dye threading of CB7 are primarily caused by the supramolecular structures shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(top) DFT calculated structures of (a) 1b@CB7, (b) 2b@CB7 and (c) 3@CB7 in water at 298 K. (bottom) Chemical structures of the encapsulated cyanine dye with the CB7 binding sites highlighted in blue. The polyethylene glycol chains of 3 were shortened to methyl groups.

CONCLUSION

This study reports several new fluorescent pentamethine cyanine dyes, each with terminal 2-aminothiophene heterocycles that extend the dye conjugation so that the absorption and emission maxima bands are well into the near-infrared region. The shapes of the terminal 2-aminothiophene heterocycles are narrow enough to penetrate the cavity of CB7, and the order of association constants in water is 3 > 1 > 2 which correlates with dye hydrophobicity. The precise location of the surrounding CB7 relative to the dye (the complex co-conformation) determines the effect of the CB7 on the dye absorption profile and fluorescence brightness. The results with highly conjugated 3 are especially notable since the free dye displays optical signatures of the “cyanine limit” problem. That is, dye 3 exhibits extensive solvatochromism due to stabilization of a symmetry breaking Peierls transition in polar solvents. In water, dye 3 adopts a polar, ground state with an unsymmetric distribution of π-electron density and localized positive charge that produces a very broad dye absorption profile and low fluorescence quantum yield which is typically undesired in fluorescence imaging. When 3 is encapsulated within CB7, the surrounding CB7 is located primarily around the dye’s central chlorocyclohexenyl ring (Figure 4c), and the chromophore adopts a more symmetrical π-electron state that produces a sharper absorption band and 12-fold higher fluorescence brightness at 979 nm. The same supramolecular effects are observed with homologous cyanine dye system 1 (Figure 4a) and together the two examples (CB7 encapsulation of dyes 1 or 3) demonstrate a supramolecular solution to the “cyanine limit” problem. In principle, this supramolecular strategy can be generalized as a new way to enhance the fluorescence quantum yield of highly conjugated cyanine dyes for improved performance in long wavelength NIR-II fluorescence imaging.17,19,58,59

In the case of cyanine dye system 2, the opposite supramolecular effect is observed. That is, the absorption profile is broadened and the fluorescence is partially quenched upon dye encapsulation, which is a rare finding since the vast majority of fluorescent dyes become brighter when encapsulated by CB7.36–38,60 The result is attributed to formation of an unsymmetrical CB7-dye complex which induces the dye to adopt a polar symmetric π-electron state with a localized positive charge at one end of the chromophore (Figure 4b). Discovery of a near-infrared dye system that exhibits “turn-on” fluorescence when the partially quenched dye is displaced from CB7 (Figure 2b) is practically important as it provides a development path towards improved “turn-on” fluorescent sensors for many types of drugs and bioactive molecules.36,50,61,62 We envision future designs of near-infrared dye displacement assays that could use either a binary cyanine/CB7 admixture for operation in low salt aqueous solutions or alternatively a covalent conjugate of the two components for more complex media such as blood, serum, or urine.50

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General methods.

Column chromatography was performed using Biotage SNAP Ultra or Sfar columns. 1H, 13C and ROESY NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 500 NMR spectrometer. Chemical shifts are presented in ppm and referenced by residual solvent peak. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was performed using a time-of-flight (TOF) analyzer with electrospray ionization (ESI). Absorption spectra were recorded on an Evolution 201 UV/vis spectrometer with Thermo Insight software. Fluorescence spectra were collected on Horiba Fluoromax4 fluorometer or Fluoromax Plus fluorometer with an InGaAs detector and FluoroEssence software.

Synthesis.

Vilsmeier-Haack reagents 5,63 7,64 and aminothiophene 6a,65 6b,66 6e,67 6f66 were synthesized according to the literature procedures. Vilsmeier-Haack reagents 5 and 12 was stored under hexane at −20 °C. Aminothiophene and aminothienothiophene compounds were stored as toluene solutions (10–30 wt %) at −20 °C under inert atmosphere due to their moderate stability.

Compound 6d.

A mixture of 6f (240 mg, 911 μmol, 1 eq), 1-azido-2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethane (517 mg, 2.73 mmol, 3 eq), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (17.0 mg, 20.5 μmol, 0.05 eq) and one drop of 2,6-lutidine in DCM (10 mL) was refluxed under argon atmosphere for 12 h. Solvent was removed and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, 0–8% MeOH in DCM) to afford 6d as a gray oil (450 mg, 77%, Rf = 0.5 in DCM/MeOH = 10/1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 7.79 (s, 2H), 6.70 (dd, J = 5.5, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 5.86 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (s, 4H), 4.48 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 4H), 3.82 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 4H), 3.66 – 3.28 (m, 30H).13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 127.4, 125.1, 124.9, 109.3, 101.8, 71.9, 70.3, 70.2, 69.4, 67.5, 64.2, 58.7, 55.6, 53.9, 50.0. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C28H48N7O8S+ 642.3280, found 642.3296.

General procedure for the synthesis of dyes 1, 2 and 4.

Vilsmeier-Haack reagent 5, 7 or 12 (290 μmol, 1 eq) and p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (290 μmol, 1 equivalent for 5 and 12; 580 μmol, 2 equivalent for 7) were dissolved in methanol (5 mL) in a two-neck flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, a septum and a condenser. The air in the flask was expelled using vacuum line. The flask was then refilled with argon and heated to 50 °C with stirring. A solution of aminothiophene 6 (637 μmol, 2.2 eq) in methanol (5 mL) was injected through the septum by syringe. The reaction color suddenly turned red and then dark-green after approximately 1 min. After 20 min, the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography.

Compound 1a (tosylate salt).

Prepared according to the general procedure from 5 and 6a. The product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 0 – 8% MeOH in DCM) as a green solid. (160 mg, 86%). M.p. = 157 – 159 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 7.81 (s, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.53 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.65 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.57 (br s, 8H), 2.65 (br s, 4H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 1.86 (br s, 2H), 1.72 (m, 12H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 172.8, 147.8, 146.4, 142.6, 140.4, 136.6, 128.6, 128.5, 126.4, 125.8, 111.6, 52.7, 28.0, 25.6, 23.2, 21.1, 20.2. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C26H32ClN2S2+ 471.1690, found 471.1703.

Compound 2a (tosylate salt).

Prepared according to the general procedure from 7 and 6a. The product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 0 – 8% MeOH in DCM) as a green solid. (100 mg, 61%). M.p. = 82 – 85 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 7.64 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (t, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 6.80 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 6.57 (dd, J = 13.0, 12.5 Hz, 2H), 3.60 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 8H), 2.27 (s, 3H), 1.69 (br s, 8H), 1.64 (br , 4H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 171.1, 152.4, 144.2, 143.3, 141.6, 140.4, 129.2, 128.6, 125.8, 122.2, 111.7, 52.7, 25.5, 23.2, 20.2. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C23H29N2S2+ 397.1767, found 397.1769.

Compound 1b (trifluoroacetate salt).

Prepared according to the general procedure from 5 and 6b. The reaction mixture was mixed with NH4PF6 (200 mg) and then purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 5 – 15% MeOH in DCM) to afford the PF6− salt. The PF6− salt was loaded on a C18 reverse phase column and eluted with MeOH with 0.1% TFA, green fractions were combined and evaporated under reduced pressure to afford the product as a green solid (170 mg, 86%). M.p. = 185 – 187 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 8.05 (s, 2H), 7.66 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 4H), 3.85 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 4H), 2.84 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H), 1.99 (p, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H).13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 174.0, 148.8, 146.0, 137.3, 128.3, 126.3, 111.9, 58.7, 57.4, 28.1, 21.2. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C24H32ClN2O4S2+ 511.1481, found 511.1487.

Compound 2b (trifluoroacetate salt).

Synthesized according to the same procedure as 1b from 7 and 6b. Green solid (150 mg, 67%). M.p. = 130 – 133 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 7.60 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 13.4 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (t, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 6.56 (dd, J = 13.4, 12.9 Hz, 2H), 5.03 (s, 4H), 3.69 (br s, 8H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 172.0, 153.4, 143.1, 142.3, 128.9, 121.8, 112.0, 58.7, 57.4. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C21H29N2O4S2+ 437.1563, found 437.1564.

Compound 1d (tosylate salt).

Prepared according to the general procedure from 5 and 6d. The product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 5 – 15% MeOH in DCM) as a green gummy solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 8.00 (s, 4H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.65 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 4.60 (s, 8H), 4.54 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 8H), 3.85 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 8H), 3.83–3.48 (m, 48H), 3.32 (s, 12H), 2.77 (br s, 4H), 2.36 (s, 3H), 1.97 (br s, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 173.8, 148.9, 146.1, 144.7, 144.2, 137.5, 128.6, 128.4, 126.4, 125.9, 124.8, 124.6, 112.2, 71.8, 70.3, 70.2, 70.1, 69.1, 67.0, 63.8, 57.9, 54.9, 50.2, 28.2, 21.2, 20.1. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C64H100ClN14O16S2+ 1419.6566, found 1419.6569.

Compound 2d (tosylate salt).

Prepared according to the general procedure from 7 and 6d. The product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 5 – 15% MeOH in DCM) as a green gummy solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 7.98 (s, 4H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (t, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.60 (dd, J = 13.3, 12.4 Hz, 2H), 6.55 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 4.60 (s, 8H), 4.54 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 8H), 3.85 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 8H), 3.83–3.49 (m, 48H), 3.32 (s, 12H), 2.37 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 171.7, 153.7, 144.2, 143.4, 142.5, 140.4, 129.0, 128.7, 125.8, 124.8, 124.7, 122.1, 112.3, 71.8, 70.3, 70.2, 70.1, 69.1, 67.0, 63.8, 58.0, 55.0, 50.2, 20.3. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C61H97N14O16S2+ 1345.6643, found 1345.6639.

Compound 1e (tosylate salt).

Prepared according to the general procedure from 5 and 6e. The product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 0 – 8% MeOH in DCM) as a green solid. (170 mg, 84%). M.p. = 131 – 134 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 7.99 (s, 2H), 7.85 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 6.82 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 4.17 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 4H), 3.85 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 4H), 3.74 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 4H), 3.30 (s, 6H), 2.76 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.49 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 1.91 (p, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 174.0, 151.3, 146.8, 146.2, 137.6, 128.6, 128.4, 126.2, 125.8, 122.3, 111.5, 79.1, 75.2, 66.6, 58.0, 55.7, 41.4, 28.1, 21.2, 20.1. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C28H32ClN2S2+ 527.1588, found 527.1561.

Compound 2e (tosylate salt).

Prepared according to the general procedure from 7 and 6e. The product was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 0 – 8% MeOH in DCM) as a green solid. (130 mg, 71%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 7.72 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (d, J = 13.3 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (t, J = 12.5 Hz, 2H), 6.50 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 6.46 (dd, J = 13.3, 12.5 Hz, 2H), 4.19 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 6H), 3.82 – 3.80 (m, 14H), 2.90 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 2.36 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 171.9, 153.6, 143.4, 143.4, 142.5, 140.4, 129.0, 128.7, 125.8, 121.9, 111.6, 79.2, 75.3, 66.6, 58.0, 55.6, 41.4, 20.2. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C25H29N2O2S2+ 453.1665, found 453.1683.

Compound 1c (chloride salt).

A mixture of 1e (45.0 mg, 66.8 μmol, 1 eq), 2-[2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy]ethanol (35.0 mg, 200 mmol, 3 eq), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (5 mg) and one drop of 2,6-lutidine in DCM (5 mL) was stirred under argon atmosphere for 24 h. Solvent was removed and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, 10–20% MeOH in DCM) to afford the tosylate salt of 1c. To increase the water solubility, the tosylate salt was converted to chloride salt by passing through a Dowex 22 resin (Chloride form) column eluting with methanol. The green fraction was collected and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to afford 1c as a green sticky solid (35 mg, 51%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 8.02 (s, 2H), 7.78 (s, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 6.57 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 4.58 (s, 4H), 4.47 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 4H), 3.85 – 3.40 (m, 28H), 3.26 (s, 6H), 2.81 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 4H), 2.74 (p, J = 6.1 Hz, 4H).13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 173.9, 146.2, 144.2, 137.4, 128.4, 126.1, 124.8, 118.6, 111.6, 72.5, 70.2, 70.2, 69.1, 66.9, 63.7, 61.0, 55.8, 50.2, 41.5, 28.1, 21.2. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C40H58ClN8O8S2+ 877.3502, found 877.3522.

Compound 2c (chloride salt).

Synthesized according to the same procedure as 1c. Green solid (45% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 8.04 (s, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 13.4 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (dd, J = 13.4, 12.9 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (t, J = 12.9 Hz, 2H), 6.54 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 4.65 (s, 4H), 4.58 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 4H), 3.89 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 4H), 3.84 (s, 6H), 3.66 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 4H), 3.62 – 3.59 (m, 12H), 3.52 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 4H), 3.33 (br s, 4H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 171.9, 153.5, 144.2, 143.29, 142.4, 129.0, 124.8, 121.8, 111.7, 72.4, 70.2, 70.2, 69.1, 66.9, 63.7, 61.0, 55.7, 50.2, 41.6. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C37H55N8O8S2+ 803.3579, found 803.3561.

Compound 10.

A mixture of 841 (1.00 g, 4.56 mmol, 1 eq), 968 (3.03 g, 13.7 mmol, 3 eq), copper (58.0 mg, 913 μmol, 0.2 eq), copper(I) iodide (174 mg, 913 μmol, 0.2 eq) and tripotassium phosphate (2.91 g, 13.7 mmol, 3 eq) in 2-dimethylaminoethanol (20 mL) was stirred at 70 °C for 24 h under argon atmosphere. The reaction was diluted with water (100 mL) and extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 100 mL). The organic extracts were combinded and dried over sodium sulfate. The solvent was removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography (SiO2, 50% EtOAc in hexane) to afford 10 as a yellow oil (250 mg, 15%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 7.04 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.05 (s, 1H), 3.69 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.65 – 3.59 (m, 10H), 3.55 – 3.50 (m, 2H), 3.45 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.36 (s, 3H), 3.00 (s, 3H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 159.9, 139.3, 120.2, 119.4, 94.5, 72.0, 70.7, 70.7, 70.7, 70.7, 70.6, 68.5, 59.1, 55.3, 41.1. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M+H]+ calcd for C16H26NO4S2+ 360.1298, found 360.1298.

Compound 3 (Chloride salt).

Vilsmeier-Haack reagent 5 (50.0 mg, 290 μmol, 1 eq) and p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (49.9 mg, 290 μmol, 1 eq) were dissolved in methanol (5 mL) in a two-neck flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, a septum and a condenser. The air in the flask was expelled using vacuum line. The flask was then refilled with argon and heated to 50 °C with stirring. A solution of 10 (229 mg, 637 μmol, 2.2 eq) in methanol (5 mL) was injected through the septum by syringe. The reaction color suddenly turned purple and then dark-green after ~1 min. After 30 min, the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography (5 – 15% MeOH in DCM) to afford the tosylate salt of 3. To increase the water solubility, the tosylate salt was converted to chloride salt by passing through a Dowex 22 resin (Chloride form) column eluting with methanol. The deep green fraction was collected and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to afford 3 as a black-green solid (160 mg, 54%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 8.02 (s, 2H), 7.68 (s, 2H), 6.60 (s, 2H), 4.62 (s, 6H), 3.80 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 4H), 3.77 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 4H), 3.65 – 3.48 (m, 24H), 3.33 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 6H), 2.86 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 2.00 (p, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H). 13C{1H} NMR was not obtained due to aggregation at millimolar concentration in serval solvents. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C40H57ClN2O8S4+ 856.2681, found 856.2672.

Compound 12.

A 100 mL round bottom flask containing DMF (2.45 mL, 31.7 mmol, 4 eq) and DCM (2 mL) was chilled in an ice bath. POCl3 (2.22 mL, 23.8 mmol, 3 eq) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred vigorously at room temperature for 30 min to afford the Vilsmeier intermediate. Commercially available compound 11 (1.00 g, 7.92 mmol, 1 eq) in DCM (2 mL) was added to the Vilsmeier intermediate. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 3 h. DCM was evaporated under reduced pressure then ice-water mixture (~ 50 mL) was added. The mixture was sonicated to suspend the orange oil and kept in fridge (~4 °C) overnight. During this time yellow solid formed, which was collected by filtration, washed with cold water, hexane and vacuum dried for 1 h at room temperature to give the known compound 1269 (840 mg, 53%) which was stored at – 20 °C with hexane. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 10.86 (s, 1H), 10.10 (s, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 2.18 (s, 2H), 2.12 (s, 2H), 0.87 (s, 6H).

Compound 4b (trifluoroacetate salt).

Synthesized according to the same procedure as 1b from 12 and 6b. Green solid (88 mg, 53%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 8.11 (s, 2H), 7.68 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 6.74 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 8H), 3.85 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 8H), 2.64 (s, 4H), 1.12 (s, 6H). 13C{1H} NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6, 25 °C) δ (ppm): 182.9, 155.9, 155.2, 146.3, 136.7, 133.0, 122.0, 67.5, 66.5, 50.2, 39.1, 37.5. HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C26H36ClN2O4S2+ 539.1800, found 539.1783.

Photostability measurements.

A solution of dye (5 μM) or dye/CB7 (3 eq) complex in water was placed in a 1 mL cuvette that was exposed to air and irradiated at a distance of 5 cm by a 150 W Xenon lamp with a 620 nm long-pass filter (0.5 mW/cm2). An absorbance spectrum was recorded every 2 min. The normalized maximum absorbance of dyes were plotted against time.

Relative fluorescence quantum yield measurements.

Fluorescence quantum yield measurements used indocyanine green (Φf = 13.5% in ethanol and 4.5% in water for NIR-I)70 or IR-1061 (Φf = 0.59% in dichloromethane for NIR-II)48 as reference standards. The dye concentrations were adjusted to the absorption value of 0.08 at 740 nm or 900 nm. The fluorescence spectrum of each solution was obtained with excitation at 740 nm or 900 nm, and the integrated area was used in the quantum yield calculation by the following equation:

where η is the refractive index of the solvent (ηwater = 1.333 and ηDCM = 1.424), I is the integrated fluorescence intensity, and A is the absorbance at a chosen wavelength. The estimated error for this method is ±10%.

Association constant determinations.

Absorption titration experiments were carried out at 298 K using quartz cuvettes (1 mL, 10 mm path length). Solutions of dye with varying molar equivalents of CB7 were equilibrated in water for 30 seconds and then the absorption and emission spectra were collected. Association constants were determined by plotting the change in absorbance intensity versus molar equivalents using the Bindfit software.71,72

Molecular modeling.

The input structures of two co-conformational isomers for each dye@CB7 complex (CB7 located over the center or one end of the dye) were created by hand, and in each case the geometry was optimized by ORCA (5.0.1) using the B97–3c method in water (CPCM model).73 The single point energy and dipole moment for each complex was calculated using Gaussian16/C.01 with the BHandHLYP/6–311G* functional/basis set in water (CPCM model).22,25

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful for funding support from the US NIH (R35GM136212) and helpful computational advice from Professor O. Wiest.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021

Data for determination of fluorescence quantum yield and NMR determination of dye molecular conformation, copies of spectral data for each compound, titration data and plotted isotherms, molecular modeling output files (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hilderbrand SA; Weissleder R Near-Infrared Fluorescence: Application to in Vivo Molecular Imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2010, 14 (1), 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Frangioni JV In Vivo Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2003, 7 (5), 626–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Wang F; Wan H; Ma Z; Zhong Y; Sun Q; Tian Y; Qu L; Du H; Zhang M; Li L; Ma H; Luo J; Liang Y; Li WJ; Hong G; Liu L; Dai H Light-Sheet Microscopy in the near-Infrared II Window. Nat. Methods 2019, 16 (6), 545–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Lei Z; Zhang F Molecular Engineering of NIR-II Fluorophores for Improved Biomedical Detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60 (30), 16294–16308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Li B; Zhao M; Zhang F Rational Design of Near-Infrared-II Organic Molecular Dyes for Bioimaging and Biosensing. ACS Mater. Lett 2020, 2 (8), 905–917. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Liu P; Mu X; Zhang X-D; Ming D The Near-Infrared-II Fluorophores and Advanced Microscopy Technologies Development and Application in Bioimaging. Bioconjug. Chem 2019, 31 (2), 260–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Qian G; Dai B; Luo M; Yu D; Zhan J; Zhang Z; Ma D; Wang ZY Band Gap Tunable, Donor-Acceptor-Donor Charge-Transfer Heteroquinoid-Based Chromophores: Near Infrared Photoluminescence and Electroluminescence. Chem. Mater 2008, 20 (19), 6208–6216. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Antaris AL; Chen H; Cheng K; Sun Y; Hong G; Qu C; Diao S; Deng Z; Hu X; Zhang B; Zhang Bo, Zhang X;Yaghi OY; Alamparambil ZR; Hong X; Cheng Z; Dai H A Small-Molecule Dye for NIR-II Imaging. Nat. Mater 2016, 15 (2), 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Chen W; Cheng CA; Cosco ED; Ramakrishnan S; Lingg JGP; Bruns OT; Zink JI; Sletten EM Shortwave Infrared Imaging with J-Aggregates Stabilized in Hollow Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (32), 12475–12480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sun C; Li B; Zhao M; Wang S; Lei Z; Lu L; Zhang H; Feng L; Dou C; Yin D; Xu H; Cheng Y; Zhang F J-Aggregates of Cyanine Dye for NIR-II in Vivo Dynamic Vascular Imaging beyond 1500 nm. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (49), 19221–19225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Swamy MMM; Murai Y; Monde K; Tsuboi S; Jin T Shortwave-Infrared Fluorescent Molecular Imaging Probes Based on π-Conjugation Extended Indocyanine Green. Bioconjug. Chem 2021, 32 (8), 1541–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Cosco ED; Caram JR; Bruns OT; Franke D; Day RA; Farr EP; Bawendi MG; Sletten EM Flavylium Polymethine Fluorophores for Near- and Shortwave Infrared Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56 (42), 13126–13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Friedman H; Cosco E; Atallah T; Jia S; Sletten E; Caram J Establishing Design Principles for Emissive Organic SWIR Chromophores from Energy Gap Laws. Chem 2021, 7 (12), 3359–3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chen C; Tian R; Zeng Y; Chu C; Liu G Activatable Fluorescence Probes for “Turn-On” and Ratiometric Biosensing and Bioimaging: From NIR-I to NIR-II. Bioconjug. Chem 2020, 31 (2), 276–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).van Duijnhoven SMJ; Robillard MS; Langereis S; Grüll H Bioresponsive Probes for Molecular Imaging: Concepts and in Vivo Applications. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2015, 10 (4), 282–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Michie MS; Götz R; Franke C; Bowler M; Kumari N; Magidson V; Levitus M; Loncarek J; Sauer M; Schnermann MJ Cyanine Conformational Restraint in the Far-Red Range. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139 (36), 12406–12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gnaim S; Scomparin A; Eldar-Boock A; Bauer CR; Satchi-Fainaro R; Shabat D Light Emission Enhancement by Supramolecular Complexation of Chemiluminescence Probes Designed for Bioimaging. Chem. Sci 2019, 10 (10), 2945–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Peck EM; Liu W; Spence GT; Shaw SK; Davis AP; Destecroix H; Smith BD Rapid Macrocycle Threading by a Fluorescent Dye-Polymer Conjugate in Water with Nanomolar Affinity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (27), 8668–8671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Roland FM; Peck EM; Rice DR; Smith BD Preassembled Fluorescent Multivalent Probes for the Imaging of Anionic Membranes. Bioconjug. Chem 2017, 28 (4), 1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Zhu S; Tian R; Antaris AL; Chen X; Dai H Near-Infrared-II Molecular Dyes for Cancer Imaging and Surgery. Adv. Mater 2019, 31 (24), 1900321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Levitus M; Ranjit S Cyanine Dyes in Biophysical Research: The Photophysics of Polymethine Fluorescent Dyes in Biomolecular Environments. Q. Rev. Biophys 2011, 44 (1), 123–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Xu W; Leary E; Sangtarash S; Jirasek M; González MT; Christensen KE; Abellán Vicente L; Agrait N; Higgins SJ; Nichols RJ; Lambert CJ; Anderson HL A Peierls Transition in Long Polymethine Molecular Wires: Evolution of Molecular Geometry and Single-Molecule Conductance. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143 (48), 20472–20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tolbert LM; Zhao X Beyond the Cyanine Limit: Peierls Distortion and Symmetry Collapse in a Polymethine Dye. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119 (14), 3253–3258. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Pengshung M; Neal P; Atallah TL; Kwon J; Caram JR; Lopez SA; Sletten EM Silicon Incorporation in Polymethine Dyes. Chem. Commun 2020, 56 (45), 6110–6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Eskandari M; Roldao JC; Cerezo J; Milián-Medina B; Gierschner J Counterion-Mediated Crossing of the Cyanine Limit in Crystals and Fluid Solution: Bond Length Alternation and Spectral Broadening Unveiled by Quantum Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142 (6), 2835–2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bouit P-A; Aronica C; Toupet L; Le Guennic B; Andraud C; Maury O Continuous Symmetry Breaking Induced by Ion Pairing Effect in Heptamethine Cyanine Dyes: Beyond the Cyanine Limit. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132 (12), 4328–4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Pisoni DS; Todeschini L; Borges ACA; Petzhold CL; Rodembusch FS; Campo LF Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Cyanine Dyes. Synthesis, Spectral Properties, and BSA Association Study. J. Org. Chem 2014, 79 (12), 5511–5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Stackova L; Muchova E; Russo M; Slavicek P; Stacko P; Klan P Deciphering the Structure-Property Relations in Substituted Heptamethine Cyanines. J. Org. Chem 2020, 85 (15), 9776–9790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Usama SM; Inagaki F; Kobayashi H; Schnermann MJ Norcyanine-Carbamates Are Versatile Near-Infrared Fluorogenic Probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143 (15), 5674–5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Tao Z; Hong G; Shinji C; Chen C; Diao S; Antaris AL; Zhang B; Zou Y; Dai H Biological Imaging Using Nanoparticles of Small Organic Molecules with Fluorescence Emission at Wavelengths Longer than 1000 nm. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52 (49), 13002–13006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Liu Y; Li Y; Koo S; Sun Y; Liu Y; Liu X; Pan Y; Zhang Z; Du M; Lu S; Qiao X; Gao J; Wang X; Deng Z; Meng X; Xiao Y; Kim JS; Hong X Versatile Types of Inorganic/Organic NIR-IIa/IIb Fluorophores: From Strategic Design toward Molecular Imaging and Theranostics. Chem. Rev 2022, 122 (1), 209–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Buston JEH; Young JR; Anderson HL Rotaxane-Encapsulated Cyanine Dyes : Enhanced Fluorescence Efficiency and Photostability. Chem Commun 2000, 905–906. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Yau CMS; Pascu SI; Odom SA; Warren JE; Klotz EJF; Frampton MJ; Williams CC; Coropceanu V; Kuimova MK; Phillips D; Barlow S; Brédas J-L; Marder SR; Millarf V; Anderson HL Stabilisation of a Heptamethine Cyanine Dye by Rotaxane Encapsulation. Chem. Commun 2008, 25, 2897–2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Marquez C; Nau WM Polarizabilities inside Molecular Containers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2001, 40 (23), 4387–4390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Assaf KI; Nau WM Cucurbiturils: From Synthesis to High-Affinity Binding and Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44 (2), 394–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Sinn S; Biedermann F Chemical Sensors Based on Cucurbit[n]uril Macrocycles. Isr. J. Chem 2018, 58 (3–4), 357–412. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Koner AL; Nau WM Cucurbituril Encapsulation of Fluorescent Dyes. Supramol. Chem 2007, 19 (1–2), 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Dsouza RN; Pischel U; Nau WM Fluorescent Dyes and Their Supramolecular Host/Guest Complexes with Macrocycles in Aqueous Solution. Chem. Rev 2011, 111 (12), 7941–7980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Gadde S; Batchelor EK; Weiss JP; Ling Y; Kaifer AE Control of H-and J-Aggregate Formation via Host- Guest Complexation Using Cucurbituril Hosts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130 (50), 17114–17119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Keil D; Hartmann H; Moschny T Synthesis and Characterization of 1,3-Bis-(2- Dialkylamino-5-Thienyl)-Substituted Squarains - a Novel Class of Intensively Coloured Panchromatic Dyes. Dye. Pigment 1991, 17 (1), 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Liu W; McGarraugh HH; Smith BD Fluorescent Thienothiophene-Containing Squaraine Dyes and Threaded Supramolecular Complexes with Tunable Wavelengths between 600–800 nm. Molecules 2018, 23 (9), 2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Idris M; Bazzar M; Guzelturk B; Demir HV; Tuncel D Cucurbit[7]uril-Threaded Fluorene-Thiophene-Based Conjugated Polyrotaxanes. RSC Adv. 2016, 6 (100), 98109–98116. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Usama SM; Thompson T; Burgess K Productive Manipulation of Cyanine Dye π-Networks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58 (27), 8974–8976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Exner RM; Cortezon-Tamarit F; Pascu SI Explorations into the Effect of Meso-Substituents in Tricarbocyanine Dyes: A Path to Diverse Biomolecular Probes and Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60 (12), 6230–6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Levitz A; Marmarchi F; Henary M Introduction of Various Substitutions to the Methine Bridge of Heptamethine Cyanine Dyes Via Substituted Dianil Linkers. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 2018, 17, 1409–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).The fluorescence quantum yield for the linear cyanine dye system 2 was 5–10 times higher than cyanine system 1 whose structure contains a central chlorocyclohexenyl ring (Table 1 and S2), a trend that has been reported before. see ref 28 and; König SG; Krämer R Accessing Structurally Diverse Near-Infrared Cyanine Dyes for Folate Receptor-Targeted Cancer Cell Staining. Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23 (39), 9306–9312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Semonin OE; Johnson JC; Luther JM; Midgett AG; Nozik AJ; Beard MC Absolute Photoluminescence Quantum Yields of IR-26 Dye, PbS, and PbSe Quantum Dots. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2010, 1 (16), 2445–2450. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Hoshi R; Suzuki K; Hasebe N; Yoshihara T; Tobita S Absolute Quantum Yield Measurements of Near-Infrared Emission with Correction for Solvent Absorption. Anal. Chem 2019, 92 (1), 607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Liu S; Ruspic C; Mukhopadhyay P; Chakrabarti S; Zavalij PY; Isaacs L The Cucurbit[n]uril Family: Prime Components for Self-Sorting Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127 (45), 15959–15967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Hu C; Grimm L; Prabodh A; Baksi A; Siennicka A; Levkin PA; Kappes MM; Biedermann F Covalent Cucurbit[7]uril-Dye Conjugates for Sensing in Aqueous Saline Media and Biofluids. Chem. Sci 2020, 11 (41), 11142–11153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Xu W; Kan J; Redshaw C; Bian B; Fan Y; Tao Z; Xiao X A Hemicyanine and Cucurbit[n]uril Inclusion Complex: Competitive Guest Binding of Cucurbit[7]uril and Cucurbit[8]uril. Supramol. Chem 2019, 31 (7), 457–465. [Google Scholar]

- (52). The direction and magnitude of complexation induced changes in chemical shift are often used as spectroscopic clues to elucidate the structure of a host guest complex. But in this case (threading of CB7 by dye 1c or 2c), the complexation induced changes in chemical shift (Figure S6) cannot be interpreted with structural certainty because of two confounding factors;; Self-aggregation of free dye (1c or 2c) at the relatively high concentrations needed for NMR induces anisotropic shielding effects; for example, there is a substantial difference between the 1H NMR spectrum for free 1c in water (see Figure S6) where it is self-aggregated, and the spectrum for free 1c in CD3CN where it is monomeric (see Supporting Information page S24);; At room temperature, about 5–10% of free heptamethine cyanine dye molecules do not exist in the all-trans conformational state (i.e., a small fraction of the chromphore conformation adopts cis bond rotamers, see;; Rüttger F; Mindt S; Golz C; Alcarazo M; John M Isomerization and Dimerization of Indocyanine Green and a Related Heptamethine Dye. European J. Org. Chem 2019, 2019 (30), 4791–4796). [Google Scholar]; Since CB7 threading forces the encapsulated heptamethine cyanine dye (1c or 2c) to adopt an extended all-trans conformation, the complexation induced isomerization may alter the dye chemical shifts in ways that are independent of the shielding provided by the surrounding CB7. In the particular case of 1c@CB7, the complexation induced changes in chemical shift could be due to a complex that is single, relatively static structure or an ensemble average of interconverting co-conformational isomers.

- (53).Zhang S; Grimm L; Miskolczy Z; Biczók L; Biedermann F; Nau WM Binding Affinities of Cucurbit[n]urils with Cations. Chem. Commun 2019, 55 (94), 14131–14134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Song X; Fanelli MG; Cook JM; Bai F; Parish CA Mechanisms for the Reaction of Thiophene and Methylthiophene with Singlet and Triplet Molecular Oxygen. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116 (20), 4934–4946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Yang Q; Ma H; Liang Y; Dai H Rational Design of High Brightness NIR-II Organic Dyes with SDADS Structure. Acc. Mater. Res 2021, 2 (3), 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Matikonda SS; Hammersley G; Kumari N; Grabenhorst L; Glembockyte V; Tinnefeld P; Ivanic J; Levitus M; Schnermann MJ Impact of Cyanine Conformational Restraint in the Near-Infrared Range. J. Org. Chem 2020, 85 (9), 5907–5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Maillard J; Klehs K; Rumble C; Vauthey E; Heilemann M; Fuerstenberg A Universal Quenching of Common Fluorescent Probes by Water and Alcohols. Chem. Sci 2021, 12 (4), 1352–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Peck EM; Battles PM; Rice DR; Roland FM; Norquest KA; Smith BD Pre-Assembly of Near-Infrared Fluorescent Multivalent Molecular Probes for Biological Imaging. Bioconjug. Chem 2016, 27 (5), 1400–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Beatty MA; Hof F Host-Guest Binding in Water, Salty Water, and Biofluids: General Lessons for Synthetic, Bio-targeted Molecular Recognition. Chem. Soc. Rev 2021, 50 (8), 4812–4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Lee EC; Kim HJ; Park SY Reversible Shape-Morphing and Fluorescence-Switching in Supramolecular Nanomaterials Consisting of Amphiphilic Cyanostilbene and Cucurbit[7]uril. Chem. - Asian J 2019, 14 (9), 1457–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Grimm LM; Sinn S; Krstić M; D’Este E; Sonntag I; Prasetyanto EA; Kuner T; Wenzel W; De Cola L; Biedermann F Fluorescent Nanozeolite Receptors for the Highly Selective and Sensitive Detection of Neurotransmitters in Water and Biofluids. Adv. Mater 2021, 33 (49), 2104614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Sinn S; Spuling E; Bräse S; Biedermann F Rational Design and Implementation of a Cucurbit[8]uril-Based Indicator-Displacement Assay for Application in Blood Serum. Chem. Sci 2019, 10 (27), 6584–6593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Samanta A; Vendrell M; Das R; Chang Y-T Development of Photostable Near-Infrared Cyanine Dyes. Chem. Commun 2010, 46 (39), 7406–7408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Urbitsch F; Elbert BL; Llaveria J; Streatfeild PE; Anderson EA A Modular, Enantioselective Synthesis of Resolvins D3, E1, and Hybrids. Org. Lett 2020, 22 (4), 1510–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Klikar M; Jelίnková V; Růžičková Z; Mikysek T; Pytela O; Ludwig M; Bureš F Malonic Acid Derivatives on Duty as Electron-Withdrawing Units in Push-Pull Molecules. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2017, 2017 (19), 2764–2779. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Spence GT; Lo SS; Ke C; Destecroix H; Davis AP; Hartland GV; Smith BD Near-Infrared Croconaine Rotaxanes and Doped Nanoparticles for Enhanced Aqueous Photothermal Heating. Chem. - Eur. J 2014, 20 (39), 12628–12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Liu W; Peck EM; Hendzel KD; Smith BD Sensitive Structural Control of Macrocycle Threading by a Fluorescent Squaraine Dye Flanked by Polymer Chains. Org. Lett 2015, 17 (21), 5268–5271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Klein JJ; Hecht S Synthesis of a New Class of Bis(thiourea)hydrazide Pseudopeptides as Potential Inhibitors of β-Sheet Aggregation. Org. Lett 2012, 14 (1), 330–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Funabiki K; Matsui M; Yoshida T; Sugiyama N; Otsuka A Sensitizing Organic Dye, Dye-Sensitized Photoelectric Conversion Element Using It, and Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Using It, JP 2007220412 A, 2007.

- (70).Rurack K; Spieles M Fluorescence Quantum Yields of a Series of Red and Near-Infrared Dyes Emitting at 600 – 1000 nm. Anal. Chem 2011, 83 (4), 1232–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Bindfit 0.5, http://app.supramolecular.org/bindfit.

- (72).Hibbert DB; Thordarson P The Death of the Job Plot, Transparency, Open Science and Online Tools, Uncertainty Estimation Methods and Other Developments in Supramolecular Chemistry Data Analysis. Chem. Commun 2016, 52 (87), 12792–12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Brandenburg JG; Bannwarth C; Hansen A; Grimme S B97–3c: A Revised Low-Cost Variant of the B97-D Density Functional Method. J. Chem. Phy 2018, 148 (6), 064104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.