Abstract

Post-acute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (PASC) is a complex condition with multisystem involvement. We assessed patients’ experience with a PASC clinic established at University of Iowa in June 2020. A survey was electronically mailed in June 2021 asking about (1) symptoms and their impact on functional domains using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures (Global Health and Cognitive Function Abilities) (2) satisfaction with clinic services, referrals, barriers to care, and recommended support resources. Survey completion rate was 35% (97/277). Majority were women (67%), Caucasian (93%), and were not hospitalized (76%) during acute COVID-19. As many as 50% reported wait time between 1 and 3 months, 40% traveled >1 h for an appointment and referred to various subspecialities. Participants reported high symptom burden-fatigue (77%), “brain fog” (73%), exercise intolerance (73%), anxiety (63%), sleep difficulties (56%) and depression (44%). On PROMIS measures, some patients scored significantly low (≥1.5 SD below mean) in physical (22.7%), mental (15.9%), and cognitive (17.6%) domains. Approximately 61% to 93% of participants were satisfied with clinical services. Qualitative analysis added insight to their experience with healthcare. Participants suggested potential strategies for optimizing recovery, including continuity of care, a co-located multispecialty clinic, and receiving timely information from emerging research. Participants appreciated that physicians validated their symptoms and provided continuity of care and access to specialists.

Keywords: post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, patient perspectives/narratives, COVID-19, patient satisfaction, clinician–patient relationship, quality of life, survey data, qualitative methods

Introduction

Post-acute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (PASC) is a complex condition with multisystem involvement (1-6). In a longitudinal study, 87.4% of patients who recovered from COVID-19 had at least 1 symptom at 60 days of follow up (7). At 9-month follow up, studies report the presence of 1 or more symptoms in 30% to 36% of survey respondents (8,9). A recent report of 342 patients, showed that 40.7% had at least 1 symptom at 1 year of follow up.(10) The persistence of symptoms can significantly affect patients’ quality of life (1,7,11-13). Medically evaluating these patients is important to avoid erroneously attributing symptoms to PASC and misdiagnosing serious health conditions (14).

Rural areas were disproportionately affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection and people living in underserved communities face unique barriers to optimal care (15,16). According to US Census, over one-third of Iowa population lives in rural areas (17). As of December 9, 2022, more than 877,000 cases and 10,316 deaths have been reported with major outbreaks affecting the diverse work force in meat packaging plants in Iowa, United States (18,19). Mortality rate in some rural counties in Iowa (290 deaths per 100,000) has surpassed the national US mortality rate (200-225 deaths per 100,000) (19). The University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics is the only quaternary-level healthcare facility in Iowa. It is the regional referral center and caters to the healthcare needs of Iowa and neighboring states.

Healthcare institutions must adapt to the needs of the growing patient population with PASC as the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase globally (19). There is a need to understand patients’ perspectives to develop an optimally functioning clinic to provide appropriate care to assist in patient recovery (20-22). Accordingly, we surveyed patients who attended PASC clinic at our large comprehensive academic medical center about their perspectives and experiences.

Methods

Structure of the PASC Clinic

The clinic was staffed by 9 providers (including intensivists and internists). Patients were eligible to be seen 30 days after a documented positive SARS-CoV-2 test (either positive nasopharyngeal reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction or antibody test). Patients who self-referred for possible PASC without confirmed positive test were scheduled with the PASC providers in our center's general internal medicine clinic. The clinic operated one full day per week and cared for an average of 15 to 20 patients per day in 40-minute appointment slots. New patients were triaged by a nurse coordinator for appropriateness of lung testing (not ordered if no respiratory complaints or tested already elsewhere). However, during their first appointment, most patients underwent a pulmonary function test, computed tomography of the chest, laboratory testing (complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel), and screening for anxiety and depression (23,24). Patients were referred for subspecialty evaluation as appropriate.

This study received Institutional Review Board approval (IRB# 202105502). Patients seen in the first year after clinic inception (June 12, 2020) were invited to complete an online survey. Patients were emailed the information about this study and the survey link to the online site to fill out the survey, with 2 weekly reminders sent to nonrespondents.

Instruments

The survey (Supplemental File 1) was drafted using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). We collected demographic data (age, sex, and ethnicity; from the survey as well as from medical records) and asked through the survey about the (1) timing of initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, the highest level of care utilized, symptoms at the time of initial infection, symptoms 3-month postinfection and up to 4 most concerning symptoms at the time of the survey; (2) impact of symptoms on perceived physical and mental health, assessed by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Health-10 item questionnaire (PROMIS GH-10) and effect on cognitive ability assessed by the PROMIS Cognitive Function Abilities 4a-4 item questionnaire (PROMIS CA-4a) (25-27); and (3) experiences with the PASC clinic including wait time for first appointment, distance traveled, satisfaction with services (scheduling, testing, imaging, and staff), referrals provided and completed, barriers, and recommended resources. Besides two open-ended questions (resources that patients think would be helpful in an ideal post-COVID clinic and any other feedback for our post-COVID clinic), participants had option of providing free text responses to most of the questions.

The PROMIS GH-10 is helpful to gather general perception of health efficiently and includes items regarding physical health, pain, fatigue, mental health, social health, and overall health (25). The PROMIS GH-10 generates a general physical health and a general mental health measure. The PROMIS CA-4a assesses patient's perceptions regarding their cognitive abilities in daily life including concentration, memory, and mental acuity. The questions target positive self-assessment of cognitive function (eg, “My mind has been sharp as usual” and “My memory has been as good as usual”). Each question has 5 possible responses. PROMIS measures are universal rather than disease specific, reliable, and validated in diverse research and clinical settings (28,29). These were derived by National Institute of Health (NIH) initiative for use in a wide age range based on psychometric principals with effort to reduce floor and ceiling effects with the item response theory (26,30).

Data Analysis

We compared demographics between survey responders and nonresponders using chi-square tests of independence and independent sample t-tests as appropriate. Symptoms reported during the initial infection and 3-month postinfection were compared within-subjects using the sign test to determine whether symptoms shifted over time and the direction of shift. Internal consistency and reliability of the two PROMIS instruments used in this study was established using a Cronbach's alpha with α = 0.60 being sufficient and α ≥ 0.80 being ideal. The raw scores for PROMIS GH-10 and PROMIS CA-4a were transformed into normatively referenced t-scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 per scoring guide (27,30). These scores were classified as either “normal” defined as mean ±1.49 SDs, or as “significantly reduced” at ≥1.5 SDs below the mean (28,31). All statistical tests were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics v.27 (IBM, inc., Armonk, NY) and P ≤.05 was considered statistically significant. Thematic analysis of the open-ended responses was conducted to identify general themes (32). Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence 2.0 (SQUIRE) reporting guidelines were used to report data in this study (33).

Results

Demographics

Out of the 325 patients seen in the clinic in 1 year, the survey was emailed to 277 patients with a valid electronic mail address. The survey response rate was 35% (97 of 277). Most respondents were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 between March 2020 and April 2021 when the Alpha variant of SARS-CoV-2 was predominant. The mean age of responders (M = 48.7, SD = 14.8) was statistically higher than for nonresponders (M = 44.8, SD = 15.8), p= .049. Respondents were more likely to be White than nonrespondents. The largest racial/ethnicity identity aside from White was Latino/Latinx (n = 22) (Supplemental File 2).

Level of Care Received During Initial COVID-19 Infection

All respondents were at least 64 days from their initial positive test when they completed the survey, with a median interval of 234 days (interquartile range [IQR] = 124). At the time of acute COVID-19 infection, the majority (76%) of study participants were not hospitalized and either self-managed at home, received healthcare through telemedicine and/or made urgent care or emergency room visits. Only, 23 respondents (24%) reported being admitted either to the hospital or intensive care unit (ICU), or both. Men (75%) and women (81.5%) were similarly likely to receive care in an outpatient or home setting, p = .45. Women (22%) and men (28%) were similarly likely to be admitted to the hospital or ICU, p = .47.

Characteristics of Initial SARS-CoV-2 Infection and PASC Illness

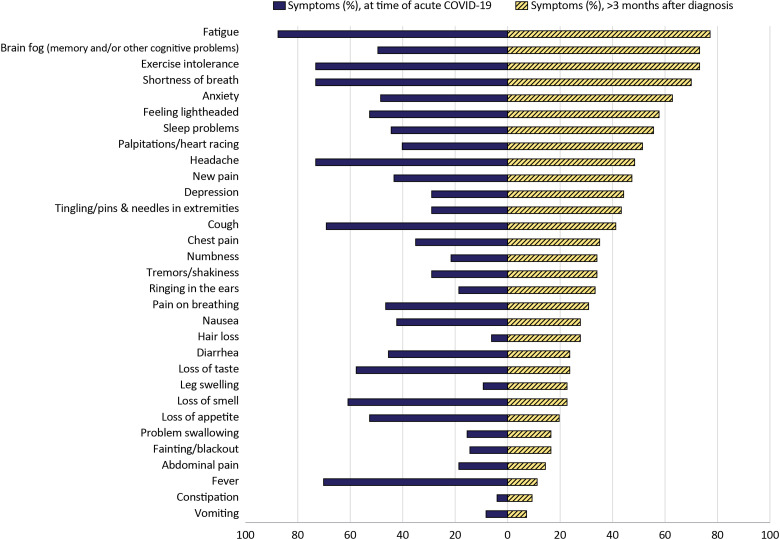

Symptoms were classified into 6 broad body systems: general, neurological/nerves/memory, lung, heart, gastrointestinal, and mental health. At the time of diagnosis, the most common symptoms reported were fatigue (88%), shortness of breath (73%), exercise intolerance (73%), and palpitations or heart racing (73%). The most reported symptoms 3-month post infection included fatigue (77%), “brain fog” or memory or cognitive impairment (73%), exercise intolerance (73%), and shortness of breath (70%; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Symptoms at the time of diagnosis and more than 3 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Abbreviation: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The most concerning symptoms at the time of filling out the survey were fatigue (52%), “brain fog” (39%), and shortness of breath (30%), followed by cough (22%). Women generally reported a higher prevalence of all symptoms compared to men, particularly fatigue (15 percentage points more) and cough (26.2 percentage points more), but far fewer men than women provided answers to this open-ended question (Supplemental File 3). The median number of general symptoms reported was 3.0 for both the initial infection and 3-month postinfection periods; however, 42.3% of participants reported fewer symptoms at 3 months compared to baseline, 20.6% reported more symptoms, and 37.1% reported the same number of symptoms (P = .01) (Supplemental File 4).

Impact on Physical and Mental Health, and Cognition

The total Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the PROMIS GH-10 and PROMIS CA-4a were α = 0.78 and α = 0.96, respectively; thus, both instruments were considered acceptably reliable for our sample. The distribution of scores for PROMIS GH-10 and PROMIS CA-4a at the time of completing the survey are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of PROMIS GH-10 Physical and Mental Health Subscores and the PROMIS Cognitive Function Abilities 4a on t-Distribution (M = 50, SD = 10).

| t-Score | PROMIS GH-10 (α = 0.78) | Cognitive function abilities (α = 0.96) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global physical health | Global mental health | |||||

| n | Valid | n | Valid | n | Valid | |

| ≥ 1.5 SDs below mean | 17 | 22.7% | 14 | 15.9% | 16 | 17.6% |

| Between 1.49 SDs below mean and mean | 44 | 58.7% | 62 | 70.5% | 53 | 58.2% |

| Between mean and 1.49 SDs above mean | 14 | 18.7% | 12 | 13.6% | 22 | 24.2% |

| ≥ 1.5 SDs above mean | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Only participants with responses to all items are included in the calculations.

Abbreviations: PROMIS GH10, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Health-10; SD, standard deviation.

The odds of expressing reduced physical health, mental health, and cognitive function did not differ by sex or initial care (outpatient vs inpatient; Supplemental File 5). In contrast, we found significant differences between patients expressing normal (mean ±1.49 SD) versus significantly reduced (≥1.5 SD) physical health, mental health, and cognitive abilities across 5 of 6 body systems as well as median total symptom burden at 3-month postinfection (Supplemental File 6). Those showing reduced mental health reported double the average of neurological symptoms (6, IQR = 2) compared to those who did not report reduced mental health (3, IQR = 2.25, P < .001). Similarly, the total number of symptoms reported by those with reduced mental health was 7.5 greater (median = 18.5, IQR = 5.25) than participants without (median = 11, IQR = 6.5, P < .001).

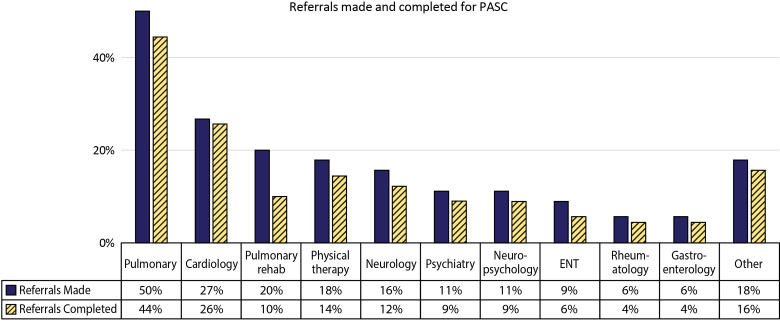

PASC Clinic Care

In total, 50% of patients reported waiting between 1 and 3 months, whereas 37% were seen within 1 month of contacting the clinic for the first appointment. Only 8 patients reported waiting 3 to 4 months for their first appointment. Most (60%) patients traveled <1 hour for their clinic appointment. Over 50% of our participants reported receiving 1 to 3 different specialty referrals after COVID-19 diagnosis, most commonly to pulmonology (50%), cardiology (27%), pulmonary rehabilitation (20%), and physical and occupational therapy (18%; Figure 2). As the symptom burden increased, the number of referrals to various subspecialists increased. There were moderate, positive correlations between total initial symptoms and referrals made (r = 0.45, p < .001) and total initial symptoms and referrals completed (r = 0.44, p ≤ .001).

Figure 2.

Referrals to specialists recommended and completed after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Other included open-ended responses like referral for sleep study, hematology-oncology, acupuncture, and “no referrals were made.” Abbreviation: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; PASC, Post Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2.

Barriers to Completing Specialist Referrals

The most common barriers reported for completing referrals were delays in getting appointments or not getting an appointment (21%) and financial concerns with uncertainty about insurance coverage for tests and appointments (16%). Other barriers included multiple clinic visits with different providers adding the complexity of care (9%), traveling a long distance for appointments (8%), inability to miss work to attend appointments (3%), limitations from symptom burden (3%), and preference for a virtual appointment rather than in-person due COVID-19 infection with in-person care (3%). Other barriers (18%) included responses such as “waiting to see if symptoms get better,” “not sure which specialty to see,” “no referrals were made,” and “insurance will not cover tests/physical therapy.”

Satisfaction With PASC Clinic

Most participants (between 61% and 93%) indicated that they were either “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their experiences and the dissatisfaction rate with all the services was <20% (Supplemental File 7). Physician interaction was rated satisfactory by 80.7% of participants. Approximately 61% to 64% were satisfied with how well we addressed physical and mental health concerns. Scheduling referrals and care-coordination was also rated satisfactory by 66% of participants, scheduling was also identified as an area needing improvement in open-ended comments. However, participants described appreciating when they received quick responses to worries (“I had an incident… and they got me in … right away”).

Resource Needs

Participants were asked to rate how helpful potential candidate resources and services might be in addressing PASC (Table 2). Continuity of care (75%), providing a multispecialty clinic (70.4%), and additional patient education from reliable sources (68.7%) were reported most helpful. Conversely, 30% or more found providing access to social worker, access to a scheduling coordinator, and group therapy interventions to be either “slightly helpful” or “not helpful at all.” Open-ended comments echoed similar themes where participants suggested speedy initial and follow-up appointments, timely referrals, and consistent follow up and coordination would improve patient experience and allay frustration with ongoing symptoms. They described valuing continuity of care and wanting their providers to share information. Requested treatments included cognitive and behavioral rehabilitation or therapy, and cardiac rehabilitation. Additional suggestions included support groups for patients and bilingual services.

Table 2.

Perceived Helpfulness of Future Resources.

| How helpful do you think each of the following resources could be to you or other patients with post-COVID symptoms? | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Not or slightly helpful | Very or extremely helpful | |

| Continuity of care and regular follow up with same doctor(s) | 8 (9.5) | 63 (75) |

| Physical therapy/occupational therapy (rehabilitation to increase physical strength and exercise capacity) | 14 (17.3) | 50 (61.7) |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation to improve breathing (supervised program) | 13 (16) | 55 (67.9) |

| Informal support group open forum, eg, online support group with other patients with similar experiences | 18 (22.2) | 44 (54.3) |

| Group therapy intervention led by a mental health provider (eg, online, or in-person group meetings) | 24 (30.4) | 34 (43) |

| Personal appointment, one-on-one counseling with a therapist | 17 (20.7) | 38 (46.3) |

| Social worker to connect patients with services (transportation, financial assistance for medical costs) | 31 (38.3) | 34 (42) |

| Coordinator to assist with scheduling medical follow-up appointments | 26 (32.1) | 37 (45.7) |

| Multiple specialty clinic (different doctors located in the same clinic space such as cardiology, pulmonary, psychiatry, etc) | 13 (16) | 57 (70.4) |

| Education and providing reliable information (providing information available from trusted sources, eg, published reputed journals, etc) | 10 (12) | 57 (68.7) |

Qualitative Analysis of Patient's Comments

Overall, 51% of participants responded to the two open-ended questions with answers ranging from 3 to 230 words. We categorized comments into the following broad themes.

Clinician–patient interaction

Participants valued open and timely communication. Some participants perceived that some clinicians valued test results more than patients’ perceptions of their health (“tired of feeling cast off by doctors as just anxiety”). Participants advised clinicians to listen to their patients, specifically about their symptoms in relation to recommendations for exercise which patients felt were beyond their capabilities. In contrast, participants appreciated when they felt clinicians listened (“I have never felt so heard and understood,” “I was extremely pleased to feel validated with my health and symptoms,” and “did not treat me like I was just making stuff up”). Participants understood that knowledge about COVID-19 was evolving, and clinicians were learning along with patients. However, they valued the opportunity to receive treatment and recommendations, including inhalers, pulmonary and physical therapy, and exercise regimens (“I felt like your clinic actually had an idea after testing of something to do to help” and “the treatment I got was spot on, I can get out and do things again”). They expressed frustration if they felt clinicians had limited suggestions for improvement or treatment.

Patient Health

Participants often reported ongoing symptoms and frustration with their slow recoveries. They reported that their PASC symptoms such as fatigue could be exacerbated by overexertion or lack of sleep. Participants also volunteered vivid comments describing PASC's negative impact on their everyday lives and perception of their health before and after COVID-19 infection: “I understand that there aren't a lot [of] answers yet. I'm just sick and tired of being sick and tired. Help!” “I need to be able to multi-task at [demanding] jobs like I used to have… I'm not sure at all that I could do those jobs as well [now].” “I am sleeping 10-12 hours straight to work full time. I am so tired when I get home.” Indeed, for some participants, COVID-19-related health changes and uncertain recovery prospects led to feelings of desperation (“Feeling pretty hopeless…” and “I'm still in pain. I still struggle daily”). In the words of 1 participant, “I feel like a shell of my former self. It's like being trapped in a not doable stage of life.”

Research

Participants wanted to know that clinicians were well-educated on disorders (eg, dysautonomia) and up to date on current research (eg, on hormonal disruption) and experimental therapies. One participant suggested that clinicians seek information across research and clinical centers about “what's worked for them, and things being tried.” In addition, responses indicate that patients are interested in participating in research and want to hear updates from their clinicians (“I wish someone would keep us updated with new advancements” and “I hope we will be notified as treatments become a thing for people with lasting symptoms”). Participants requested further exploration on impact of COVID-19 on hormones, and additional cardiac or pulmonary testing, including during exertion.

Discussion

Our survey study highlighted the experiences of patients with PASC, the impact of symptoms on their health and their experience with healthcare. The timely feedback by patients for a newly developed PASC clinic in the first year helped us understand barriers and identify key areas of improvement. In our PASC clinic, patients were offered particularly detailed assessment including pulmonary evaluation and behavioral health screening at a single visit.

To date various studies have reported multiple symptoms in PASC (7-10). Our study is in line with previous studies that have reported negative impact on quality of life in COVID-19 survivors (7,8). On PROMIS questionnaires measures, approximately 23% of patients reported having significantly reduced global physical health compared to norms for the general population (ie, ≥1.5 SD below the normative mean). Approximately 16% reported reduced global mental health (PROMIS GH-10 mental health) and 18% reported significant difficulty with cognitive function, again relative to the general population (Table 1). Interestingly, symptoms during acute illness did not relate to reduced scores, but patients who reported multiple symptoms at 3 months scored lowest in PROMIS measures. An increase in mental health symptoms (including anxiety, depression, and sleeping difficulties) was reported by 30% within 3 months of infection. A recent meta-analysis reported high prevalence of anxiety (1 in 3), sleeping difficulties (1 in 4), depression (1 in 5), and post-traumatic disorder (1 in 8) in COVID-19 survivors (34). Multiple other studies are consistent with our findings and emphasize the need to address mental health and sleeping difficulties in patients with PASC (1,3,35-37). We integrated behavioral health assessment in our PASC clinic by incorporating anxiety and depression self-reporting questionnaires. If appropriate based on overall assessment and discussion of screen results with the patients, they were also referred to a psychologist.

The qualitative analysis of patient comments adds nuance and context to some of the quantitative results and highlights the profound impact of symptoms on patients’ everyday lives. Our study echoes results from other qualitative studies where patients with PASC expressed interest in care continuity and multidisciplinary rehabilitation and highlighted the importance of attentive listening by medical providers (4,13,38,39). Therefore, we advocate for adequate appointment time for detailed assessment and counseling (40). Multiple co-located specialties in the same clinic area may not be feasible given multisystemic symptoms which may need several different specialists. However, in our PASC clinic we established several partnerships with different specialties including behavioral health, neuropsychology (follow up for cognitive assessment) and pulmonology (follow up for chronic lung disease) with identified clinical “champions” who provided subspeciality assessment in a timely manner.

Our experience brings to attention the unique challenges and needs of patients seen in our clinic with long wait times for appointments, distances traveled for healthcare assessment and financial concerns with limited access to healthcare. Further referral to different specialties adds to care complexity along with cost and time lost from work and additional travel (41,42). Nevertheless, the appointment wait times and distance traveled reported in this study should be contextualized; our large academic center provides resources for patients across the state and operates the only PASC clinic in the area. Partnering with community leaders at outreach clinics and local resources (eg, physical rehabilitation centers) could strengthen the referral system. We also provided follow-up care with telemedicine for established patients. Although having a social worker or a clinical coordinator to assist with scheduling was perceived helpful only by a small subgroup of participants, clinicians felt that having a dedicated clinical nurse coordinator helped streamline the workflow and functioning of the clinic.

The major limitation of our study was the low survey response rate (35%) which may be due to electronically mailing it months after the clinic visit, poor underlying health (due to PASC symptoms like fatigue, brain fog) and inability to employ further strategies to improve the response rate (eg, follow up—calls). Also, there was a risk of selection bias because, compared to respondents, nonrespondents were younger and more likely to be non-White. The delay could also lead to recall bias about the onset and duration of symptoms. Participants were primarily White women, and the survey was available only in English; therefore, the findings are less generalizable to men, different racial/ethnic groups, and non-English speakers. However, the sample is representative of the demographics of Iowa (17). This study is not generalizable to patients seeking care at community and private settings. Patients with confirmed positive SARS-CoV-2 tests were seen in our PASC clinic which excludes patients who were not tested during the pandemic's initial phase. A large population-based study in France found that a belief of having been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 (even though not confirmed by testing), was associated with having persistent physical symptoms (14). Not all the participants answered the open-ended questions, but our analyses of open-ended responses validated and contextualized the quantitative results.

Conclusion

Our participants reported high PASC symptom burden, which adversely impacted multiple functional domains. Although waiting times to be scheduled and travel distances could be lengthy, participants appreciated that physicians validated their symptoms and provided continuity of care and access to specialists. Healthcare systems and policymakers should focus on providing accessible, comprehensive, and patient-centered integrated PASC care.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-6-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-7-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff at University of Iowa Post-COVID-19 clinic who assisted in caring for our patients. The authors would like to thank Kristina Greiner for her editing assistance.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: AG, LG, and KFH were involved in study concept and design; AG and MS in acquisition of the data. MS, PBB, and KD conducted data analysis/interpretation. AG drafted/prepared the manuscript. RMH and APC contributed toward critical revision.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NCATS) under Award Number UL1TR002537.

ORCID iD: Alpana Garg https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9497-0141

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak TA, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P, Zandi MS, Lewis G, David AS. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611-27. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellan M, Soddu D, Balbo PE, Baricich A, Zeppegno P, Avanzi GC, Baldon G, Bartolomei G, Battaglia M, Battistini S, Binda V, Borg M, Cantaluppi V, Castello LM, Clivati E, Cisari C, Costanzo M, Croce A, Cuneo D, De Benedittis C, et al. Respiratory and psychophysical sequelae among patients with COVID-19 four months after hospital discharge. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2036142. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021;1486(1):90-111. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladds E, Rushforth A, Wieringa S, et al. Persistent symptoms after COVID-19: qualitative study of 114 "long COVID" patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1144. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-06001-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aiyegbusi OL, Hughes SE, Turner G, Aiyegbusi OL, Hughes SE, Turner G, Rivera SC, McMullan C, Chandan JS, Haroon S, Price G, Davies EH, Nirantharakumar K, Sapey E, Calvert MJ, et al. Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: a review. J R Soc Med. 2021;114(9):428-42. doi: 10.1177/01410768211032850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y, Redfield S, Austin JP, Akrami A, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carfi A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Gemelli Against C-P-ACSG. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, McDonald D, Magedson A, Wolf CR, Chu HY. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210830. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zayet S, Zahra H, Royer PY, et al. Post-COVID-19 syndrome: nine months after SARS-CoV-2 infection in a cohort of 354 patients: data from the first wave of COVID-19 in Nord Franche-Comte Hospital, France. Microorganisms. 2021;9(8):1719. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9081719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wynberg E, van Willigen HDG, Dijkstra M, Boyd A, Kootstra NA, van den Aardweg JG, van Gils MJ, Matser A, de Wit MR, Leenstra T, de Bree G, de Jong MD, Prins M, Agard I, Ayal J, Cavdar F, Craanen M, Davidovich U, Deuring A, van Dijk A, Ersan E, del Grande L, Hartman J, et al. Evolution of COVID-19 symptoms during the first 12 months after illness onset. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(1):e482-90. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McFann K, Baxter BA, LaVergne SM, et al. Quality of life (QoL) is reduced in those with severe COVID-19 disease, post-acute sequelae of COVID-19, and hospitalization in United States adults from northern Colorado. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11048. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taboada M, Moreno E, Carinena A, Rey T, Pita-Romero R, Leal S, Sanduende Y, Rodríguez A, Nieto C, Vilas E, Ochoa M, Cid M, Seoane-Pillado T, et al. Quality of life, functional status, and persistent symptoms after intensive care of COVID-19 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126(3):e110-3. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chasco EE, Dukes K, Jones D, Comellas AP, Hoffman RM, Garg A. Brain fog and fatigue following COVID-19 infection: an exploratory study of patient experiences of long COVID. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(23):15499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matta J, Wiernik E, Robineau O, Carrat F, Touvier M, Severi G, de Lamballerie X, Blanché H, Deleuze J-F, Gouraud C, Hoertel N, Ranque B, Goldberg M, Zins M, Lemogne C, Kab S, Renuy A, Le-Got S, Ribet C, Wiernik E, Goldberg M, Zins M, Artaud F, et al. Association of self-reported COVID-19 infection and SARS-CoV-2 serology test results with persistent physical symptoms among French adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(1):19-25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callaghan T, Lueck JA, Trujillo KL, Ferdinand AO. Rural and urban differences in COVID-19 prevention behaviors. J Rural Health. 2021;37(2):287-95. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang CH, Schwartz GG. Spatial disparities in coronavirus incidence and mortality in the United States: an ecological analysis as of May 2020. J Rural Health. 2020;36(3):433-45. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bereau USC. Quick facts, Iowa. Accessed December 9, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/IA.

- 18.Saitone TL, Aleks Schaefer K, Scheitrum DP. COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in U.S. meatpacking counties. Food Policy. 2021;101:102072. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coronavirus Covid-19 Global Cases by the Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at John Hopkins University(JHU). COVID-19 Map John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre, 2020. December 3, 2022. Accessed December, 3, 2022. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- 20.Long COVID: let patients help define long-lasting COVID symptoms. Nature. 2020;586(7828):170. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02796-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sykes DL, Holdsworth L, Jawad N, Gunasekera P, Morice AH, Crooks MG. Post-COVID-19 symptom burden: what is long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung. 2021;199(2):113-9. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00423-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendelson M, Nel J, Blumberg L, Madhi SA, Dryden M, Stevens W, Venter FWD, et al. Long-COVID: an evolving problem with an extensive impact. S Afr Med J. 2020;111(1):10-2. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v111i11.15433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873-80. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai JS, Wagner LI, Jacobsen PB, Cella D. Self-reported cognitive concerns and abilities: two sides of one coin? Psychooncology. 2014;23(10):1133-41. doi: 10.1002/pon.3522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.HealthMeasures. PROMIS global health scoring manual, 2021. Accessed October 25, 2021. http://www.healthmeasures.net/images/PROMIS/manuals/PROMIS_Global_Scoring_Manual.pdf.

- 28.HealthMeasures. PROMIS score cut points, 2021. Accessed October 25, 2021. https://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/promis/promis-score-cut-points.

- 29.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, Amtmann D, Bode R, Buysse D, Choi S, Cook K, DeVellis R, DeWalt D, Fries JF, Gershon R, Hahn EA, Lai J-S, Pilkonis P, Revicki D, Rose M, Weinfurt K, Hays R. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Cella D, Gershon R, et al. Representativeness of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system internet panel. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1169-78. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terwee CB, Peipert JD, Chapman R, Lai J-S, Terluin B, Cella D, Griffith P, Mokkink LB. Minimal important change (MIC): a conceptual clarification and systematic review of MIC estimates of PROMIS measures. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(10):2729-54. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02925-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (standards for QUality improvement reporting excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):986-92. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, Ba DM, Parsons N, Poudel GR, Lekoubou A, Oh JS, Ericson JE, Ssentongo P, Chinchilli VM, et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2128568. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C, Poletti S, Vai B, Bollettini I, Melloni EMT, Furlan R, Ciceri F, Rovere-Querini P, Benedetti F. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:594-600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):1013-22. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kyzar EJ, Purpura LJ, Shah J, Cantos A, Nordvig AS, Yin MT. Anxiety, depression, insomnia, and trauma-related symptoms following COVID-19 infection at long-term follow-up. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;16:100315. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kingstone T, Taylor AK, O'Donnell CA, Atherton H, Blane DN, Chew-Graham CA. Finding the 'right' GP: a qualitative study of the experiences of people with long-COVID. BJGP Open. 2020;4(5). doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lutchmansingh DD, Knauert MP, Antin-Ozerkis DE, Chupp G, Cohn L, Dela Cruz CS, Ferrante LE, Herzog EL, Koff J, Rochester CL, Ryu C, Singh I, Tickoo M, Winks V, Gulati M, Possick JD. A clinic blueprint for post-coronavirus disease 2019 RECOVERY: learning from the past, looking to the future. Chest. 2021;159(3):949-58. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(Suppl 1):S34-40. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00263.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hub RHI. Healthcare access in rural communities. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/healthcare-access.

- 42.Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015;129(6):611-20. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-6-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-7-jpx-10.1177_23743735231151539 for Patient Experiences with a Tertiary Care Post-COVID-19 Clinic by Alpana Garg, Maran Subramain, Patrick B Barlow, Lauren Garvin, Karin F Hoth, Kimberly Dukes, Richard M Hoffman and Alejandro P Comellas in Journal of Patient Experience