Abstract

Patient-centered approaches impact cancer patients’ perceptions and outcomes in different ways. This study explores the impact of patient-centered care practices on cancer patients’ quality-of-care (QOC), self-efficacy, and trust in their doctors. We utilized cross-sectional national survey data from the National Cancer Institute collected between 2017 and 2020. All estimates were weighted using the jackknife method. We used multivariable logistic regression to test our hypotheses adjusted for the demographics of the 1932 cancer patients that responded to the survey. Findings indicate that patient-centered communication resulted in better QOC, self-efficacy, and trust in doctors. In addition, engagement in their care improved patients’ trust in cancer-related information received from doctors. QOC and patients’ trust in doctors were significantly improved with the patients’ understanding of the next steps, addressing feelings, clear explanation of the problems, spending enough time with the clinicians, addressing uncertainty, and involvement in decisions. Patients who were given a chance to ask questions were significantly more likely to trust their doctors. Technology use did not impact any of these interactions. Patient-centered strategies should consider the needs of the patients in the cancer settings to improve overall outcomes. Organizations should also build strategies that are goal-oriented and centered around the patients’ needs, as standard strategies cannot induce the wanted results.

Keywords: patient-centered cancer care, cancer, oncology, communication, trust, self-efficacy, shared decision-making, quality-of-care, technology, electronic health records

Introduction

Patients with cancer must deal with several challenges, including the emotional pressure of diagnosis with a life-threatening disease and the debilitating side effects of medical treatments (1). In addition, patients and their doctors have difficulty coordinating care and facing the challenges of communication patterns and roles (1). These challenges can result in the patients displaying unhelpful behaviors that can undermine their efforts to cope with their illness, treat their condition, and create a healthy lifestyle (1). Efforts to support cancer patients have been focused on incorporating patient-centered communication (PCC) and care to maximize the benefits of current medical discoveries and opportunities (2).

Healthcare stakeholders widely advocate patient-centered care and urge the adoption of patient-centered cancer care (3). However, there is little consensus on what it is and how it is achieved (4). Different conceptualizations and assumptions about measuring and evaluating the impact of patient-centered care are being embraced (3). PCC is a subset of patient-centered care, which is recognized by the National Academy of Medicine as an essential component of defining quality-of-care (QOC) (5). As patient populations and treatment options grow and become more diverse, improved assessment and implementation of PCC are crucial (6). A growing body of evidence supports the relationship between PCC and improvements in adherence to treatment recommendations, management of chronic disease, QOC, and health outcomes (7).

In addition, research demonstrated that PCC impacts QOC in different care settings: surgical, geriatric, primary, etc (8). Considering that QOC is an essential factor in behavioral change (9), it remains essential to strengthen our understanding of how PCC approaches for cancer patients impact perceived QOC. Prior research indicates that cancer patients’ ratings of care quality are associated with the length of the patient–physician relationship, physicians’ information exchange, physicians’ affective behavior, their knowledge of the survivor, and survivors’ perceptions of care coordination (10).

Furthermore, cancer diagnosis causes variability in patients’ perception of quality of life (11). This variability impacted cancer patients’ self-efficacy (11). The usefulness of self-efficacy in oncology has been widely documented (12). For example, during chemotherapy, self-efficacy interventions improved the quality of life and reduced symptoms of distress in patients with breast cancer (13). In chronic care, patient-centeredness approaches were proven to enhance patients’ self-efficacy (14). It is thus essential to investigate the impact of patient-centered cancer care on the patients’ self-efficacy to support their quality of life.

Moreover, patients’ trust in their physicians is crucial to achieving desirable treatment outcomes such as satisfaction and adherence (15). Doctor–patient relationships are characterized by a knowledge and power imbalance that may confuse the patients about the ability of their doctors to be the best source of information for them (15). Because of cancer's potentially life-threatening nature, trust is possibly even more critical in oncology (15). Oncology patients have to weigh complex medical information and decisions and cope with uncertain prognoses, radical treatments, and sometimes limited hope for recovery (16). Patients need to leave their most valuable asset (lives), to their physicians (17), forced to trust them almost unconditionally due to the life-threatening nature of cancer (18). However, there is concern that this solid trust is at risk because healthcare providers are going through organization and approach changes that may lead to a lack of continuity of care and less personal attention for patients (19). It is, thus, essential to explore the impact of patient-centeredness on trust among cancer patients. Additionally, the increased autonomy of patients and improved information access, such as Health Information Technology, may also negatively affect the physician–patient relationship (15).

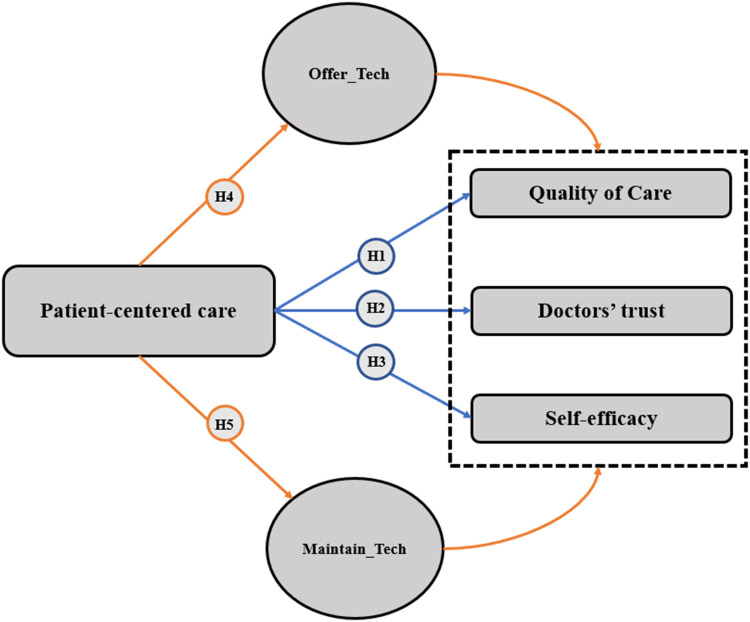

Therefore, we hypothesized that PCC would affect patients’ QOC, self-efficacy, and trust in doctors in cancer care. As illustrated in Figure 1, we also hypothesize that technology used by doctors in healthcare would mediate these relations. In this study, we explore the following hypotheses among cancer patients:

Figure 1.

Hypotheses of the study.

Hypothesis 1 (H1)

PCC is associated with QOC.

Hypothesis 2 (H2)

PCC is associated with doctors’ trust as a source of information.

Hypothesis 3 (H3)

PCC is associated with patients’ self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 4 (H4)

Technology use mediates the effect of PCC on QOC.

Hypothesis 5 (H5)

Doctors’ use of computerized systems to record medical records online mediates the effect of PCC on QOC.

The models analyzed in this study are not intended to validate theories but conceptual frameworks to explore one aspect of how PCC can influence patients’ trust, self-efficacy, and QOC.

Methods

We used a cross-sectional survey from the Health Information National Trends Survey, HINTS data repository administered to accumulate US public data (20). The National Cancer Institute collects these surveys to update health communication practices and usage in the United Systems (20). We used 4 data cycles (2017-2020). Only patients with a cancer history are considered. We used 17 variables from the survey in the study; 5 of them are demographic variables. All the questions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables of the Study.

| Variable | Name of variable | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Use of technology | ||

| Use of technology by providers | Maintain_Tech | Do any of your doctors or other health care providers maintain your medical records in a computerized system? |

| Involving patients in technology use | Offer_Tech | Have you ever been offered online access to your medical records by your healthcare provider? |

| Patient-centered care practices | ||

| Chance to ask questions | ChanceAskQuestions | During the past 12 months, how often did doctors, nurses, or other health professionals give you the chance to ask all the health-related questions you had? |

| Understood next steps | Understoodnextsteps | During the past 12 months, how often do they make sure you understood what you needed to do to take care of your health? |

| Feelings addressed | FeelingsAddressed | During the past 12 months, how often did doctors, nurses, or other health professionals give the attention you needed to your feelings and emotions? |

| Explained clearly | ExplainedClearly | During the past 12 months, how often did they explain things so you could understand? |

| Spent enough time | SpentEnoughTime | During the past 12 months, how often did they spend enough time with you? |

| Help with uncertainty | HelpUncertainty | During the past 12 months, how often did they help you deal with feelings of uncertainty about your health or health care? |

| Involved decisions | InvolvedDecisions | During the past 12 months, how often did they involve you in deciding your health care as much as you wanted? (Yes/No) |

| Quality of care perception: | ||

| Quality of care perception | Quality-of-Care | Overall, how would you rate the quality of health care you received in the past 12 months? |

| Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy | Overall, how confident are you that you can take care of your health? |

| Doctors’ trust | Doctors’ Trust | How much do you trust the information about cancer that you get from your doctor? |

| Demographics | ||

| Age | Age | What is your age? |

| Cancer | Cancer history | Have you ever been diagnosed as having cancer? |

| Gender | Gender | Birth gender |

| Education | Education | What is the highest degree obtained? |

| Household income | HH income | What is your (combined) annual household income? 5 Levels |

PCC score was assessed using the following 6 survey items as described in the NCI monograph: “how often did you feel your doctors, nurses, or other health care professionals: (1) gave you a chance to ask health-related questions?” (Exchanging information), (2) gave the attention needed to your emotions?” (Responding to emotion), (3) involved you in decisions as much as you wanted?” (Making decisions), (4) made sure you understood the things you needed to do?” (Enabling self-management), (5) helped you deal with feelings of uncertainty?” (Managing uncertainty), and (6) “how often did you feel you could rely on your doctors, nurses, or other health care professionals?” (Fostering healing relationships). This score was validated and used in other studies using the same database (21,22). Valid responses included always, usually, sometimes, and never. Responses were dichotomized as optimal (always) and suboptimal (usually, sometimes, and never), similar to the analysis by Blanch-Hartigan et al (22). The 6 dichotomized PCC questions generated a continuous, overall PCC score. The 6 dichotomized PCC questions were averaged and transformed to a 0-100 scale. Dichotomizing the variable is an appropriate method to control ceiling effects as in other research with patient ratings (22).

Data Analysis

We merged HINTS’ 4 data cycles and selected only cancer patients. We did not consider participants who did not fully respond to the questions of this study. First, descriptive analysis statistics were conducted. All analyses were performed using the weighted samples described in HINTS reports using a jackknife replication approach with 50 repliaces (23). Survey weighting allows researchers to develop generalizable estimates of the US population (23). We conducted logistic regression analyses to test the hypotheses using chi-square tests of independence to test the collinearity between variables. This method is commonly used for the HINTS data (24).

Results

Initially, 2579 patients responded to the survey. Then we excluded the patients with missing answers (24 patients). As a final filtering, we selected only cancer patients or patients with a cancer history. A final sample of 1932 complete answers were kept. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the respondents.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents.

| Variable | Unweighted population N (%) | Weighted population N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 831 (43.01%) | 110 359 864 (38.5%) |

| Female | 1101 (56.98%) | 110 359 864 (61.5%) | |

| Age | 18-34 | 27 (1.40%) | 176 289 133 (6.00%) |

| 35-64 | 734 (37.99%) | 17 198 940 (32.50%) | |

| ≥ 65 | 1171 (60.61%) | 93 160 924 (61.50%) | |

| Education | < High school | 98 (5.07%) | 176 289 133 (9.35%) |

| High school | 368 (19.04%) | 26 801 681 (15.62%) | |

| College | 1466 (75.89%) | 44 774 573 (75.03%) | |

| Household income | < $20 000 | 313 (16.20%) | 215 072 743 (21.50%) |

| US$20 000 to <US$35 000 | 291 (15.06%) | 61 629 534 (12.57%) | |

| US$35 000 to <US$50 000 | 262 (13.56%) | 36 031 779 (11.23%) | |

| US$50 000 to <US$75 000 | 378 (19.56%) | 32 190 682 (16.44%) | |

| US$75 000 or more | 688 (35.62%) | 47 125 095 (38.26%) | |

A total of 75.89% of the participants went to college, and 60.61% of them were above 64 years old. We adjusted for the demographic variables and ran adjusted logistic regression models as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models’ Results.

| Variables | Quality-of-care | Self-efficacy | Doctors’ trust | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | OR | P-value | OR | P-value | OR | ||

| PCC | High | ||||||

| Low | .00 *** | 0.08 [0.03-0.18] | .00*** | 0.56 [0.41-0.76] | .00*** | 0.37 [0.24-0.57] | |

| Chance to Ask Questions | No | ||||||

| Yes | .001** | 0.12 [0.03-0.53] | .940 | 1.93 [0.03-5.87] | .001** | 9.26 [2.3-26.35] | |

| understood Next Steps | No | ||||||

| Yes | .00*** | 6.2 [1.45-27.39] | .414 | 0.51 [0.10-2.56] | .002** | 9.06 [2.27-16.08] | |

| Feelings Addressed | No | ||||||

| Yes | .00*** | 2.6 [8.05-18.46] | .40 | 1.44 [0.60-3.42] | .003** | 3.95 [1.61-9.75] | |

| Explained Clearly | No | ||||||

| Yes | .00*** | 4.50 [1.86-23.81] | .047* | 0.10 [0.01-0.96] | .02* | 6.95 [1.31-16.59] | |

| Spent Enough Time | No | ||||||

| Yes | .001** | 10.55 [2.72-40.90] | .794 | 1.13 [0.43-3.00] | .004** | 4.31 [1.60-11.60] | |

| Help with Uncertainty | No | ||||||

| Yes | .00*** | 18.94 [6.77-38.18] | .44 | 0.78 [0.42-1.45] | .005** | 3.09 [1.41-6.78] | |

| Involved in Decisions | No | ||||||

| Yes | .00*** | 13.35 [3.28-54.25] | .69 | 1.31 [0.34-5.00] | .045* | 2.60 [0.62-10.85] | |

| Gender | Male | ||||||

| Female | .545 | 4.20 [1.76-2.80] | .215 | 1.42 [0.60-3.42] | .415 | 6.95 [1.31-16.59] | |

| Education | < High school | ||||||

| High school | .850 | 6.2 [1.45-17.39] | .208 | 1.12 [0.40-3.21] | .144 | 2.95 [0.62-6.72] | |

| College | .071 | 2.6 [1.05-7.57] | .012* | 1.08 [0.20-5.21] | .177 | 1.37 [0.42-0.75] | |

| Household Income | < $75 000 | ||||||

| $75 000 or more | .092 | 0.11 [0.02-1.32] | .147 | 0.78 [0.01-1.99] | .088 | 1.21 [0.02-8.32] | |

| Age | 18–34 | ||||||

| 35–64 | .01* | 1.22 [0.45-6.54] | .05 | 1.11 [0.17-4.72] | .06 | 1.39 [0.03-5.72] | |

| > = 65 | .05 | 1.01 [0.47-8.14] | .07 | 2.01 [0.72-8.70] | .09 | 2.92 [0.03-6.92] | |

Note: * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratios; PCC, patient-centered communication.

We found that PCC significantly correlated with the QOC, self-efficacy, and doctors’ trust. The better the PCC is, the better patients perceive QOC received, the more they feel that they can take care of their health, and the more they trust the cancer-related information they received from their doctors (odds ratio [OR] = 0.08; OR = 0.56; OR = 0.37).

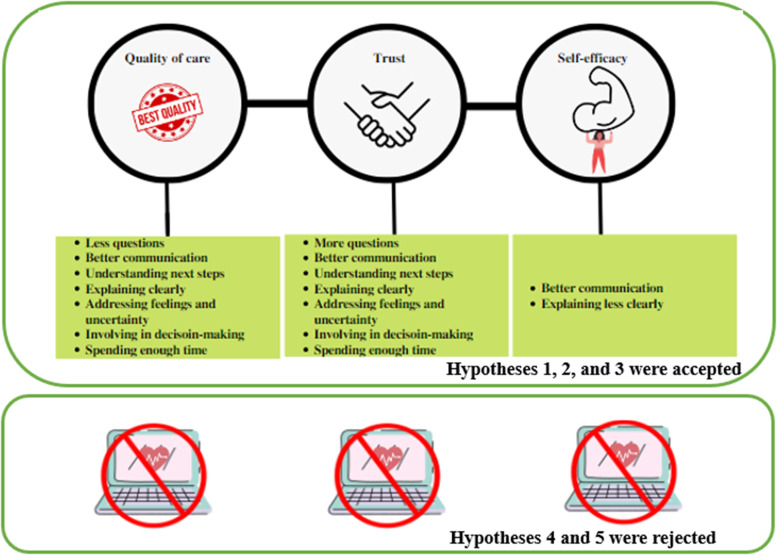

QOC and patients’ trust in doctors were significantly improved with the patients’ understanding of the next steps, addressing feelings, clear explanation of the problems, spending enough time with the clinicians, addressing uncertainty, and involvement in decisions. Patients who were given a chance to ask questions were significantly more likely to trust the information they received from their doctors (OR = 9.26). However, PCC did not improve the patients’ self-efficacy. Self-efficacy was significantly correlated with low PCC (OR = 0.56) and clear explanation (OR = 0.10). We also tested the impact of technology use on these interactions, and found that all the interactions between patients-centeredness and QOC, self-efficacy, and trust were not significant mediating both technology use variables. So, we accept Hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3) and fail to accept H4 and H5.

Discussion

This study examined the impact of PCC on patients’ outcomes (QOC, self-efficacy, and doctors’ trust) in cancer care. The analyses showed that PCC significantly improved the 3 outcomes: self-efficacy, trust in doctors, and QOC. In addition, addressing feelings, understanding the following steps, providing clear and understandable explanations, spending enough time with the patients, and managing uncertainty and involvement in decisions improved the QOC and doctors’ trust. Giving the chance to ask questions improved trust. However, PCC did not improve self-efficacy. Finally, technology use did not impact these relationships between PCC and outcomes. The framework summarizing all the findings is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of the findings.

Patient-Centered Communication

All stakeholder groups in cancer care have expressed interest in improving the quality of cancer care (25). Stakeholder groups, including patients, may have different definitions of quality care, and discrepancies in values may not be reflected in the standards developed by groups (25). Thus, the quality of cancer care must be aligned with the values of each stakeholder (25). The Institute of Medicine confirmed that quality of cancer care requires safety, efficacy, timeliness, and a patient-centered approach coordinated by an interprofessional team with the integration of evidence-based practices (26). Our study focused on the patient-centered approach from a patient's perspective to identify the needs of cancer patients. Quality improvement methodology is established around improving the quality of communication (27). Although communication in public health domains is well recognized, structured communication strategies are not formally incorporated into QOC improvement frameworks (27). The application of communication approaches in quality improvement initiatives remains poorly examined across different sectors (28). In addition, communication is often evaluated individually, for example, by assessing one-to-one interactions between healthcare consumers and providers (29). With the emergence of importance given to communication in cancer care, it remains essential to evaluate the effectiveness of QOC through PCC as we showed the correlation between them. Furthermore, since the focus of cancer care and control efforts has shifted to more individualized and long-term approaches, empowering survivors to take on a more active role in their medical care is becoming a more critical component of cancer survivorship. Extensive literature is supporting effective PCC as a critical factor for the development of effective self-management (7). In this study, we also confirmed that effective communication between cancer patients and providers could significantly increase their participation in their healthcare. Finally, trust is defined as the patient's belief that doctors care for his best interests (30). This study found that PCC strengthens cancer patients’ trust in their doctors. Thus, oncologists can convey their care and empathy and build a trusting ground with their patients through effective communication.

Time and Information Needs Among Cancer Patients

Quality of cancer care entails providing patients with ample information, and clinicians are often criticized for insufficient information sharing (31). While clinicians are expected to provide information, the expectations are very general and confusing and can be challenging to implement in practice despite extensive research on information-giving (31). A cancer diagnosis can induce uncertainty, fear, and loss that can be alleviated by information (32). Patients’ needed amount of data varies and may even change throughout their illness (32). In turn, these attitudes are reflected in patients’ efforts to obtain more information or resist information offered to them (32). When patients are diagnosed with cancer, their suffering is often compounded by inadequate information about disease trajectories and information sharing.

Giving patients the required information at the right time and amount can empower them and help them cope with their illnesses. In this study, we found that explaining things clearly to cancer patients and introducing the next treatment steps helped them gain trust in their providers and improved their QOC. However, asking too many questions might also create confusion in how they perceived things related to cancer treatment, which may influence their QOC in a negative way. Some cancer patients think that “searching for information on themselves can give them more information than the costly appointments with the medical professionals (33).” This self-efficacy is essential, but without control over the type of information a patient has access to, it remains hard to control their perceptions and ensure their adherence to suitable treatment plans. Being exposed to too much information from different sources can harm due to potential confusion, especially since existing healthcare systems are becoming more and more market-oriented (33). Thus, it is essential for patients to access trustworthy and sufficient information during their treatment path to maintain a good relationship with the doctors and trust the medical services received.

Involvement in Decision-Making

Involving cancer patients in decision-making remains of the same importance as information sharing (34). Clinicians and patients need to share various types of information to provide optimal care to patients with complex illnesses (35). Physicians rely on medical evidence, clinical training, and experience, while patients rely on their knowledge (35). Neither party owns all the necessary information (35). Clinicians and patients must exchange knowledge in both directions to avoid silent misdiagnosis. Patients may not know all their options and outcomes, and clinicians may be unaware of patients’ circumstances and preferences (36). Research has shown that involving cancer patients in treatment decisions can improve their QOC, physical function, patient satisfaction, and quality of life (37). Patients diagnosed with breast and prostate cancer who were experiencing a passive role in treatment decision-making were experiencing more significant distress and lower quality of life (38). Researchers have increasingly highlighted the mismatch between the level of involvement patients prefer and what they believe they want in decision-making for cancer treatment in the last 2 decades (39). Patient-centered care aims to put individual patients and their preferences at the center, and utilize patient-reported outcomes, and shared decision-making (SDM) (40). A shared decision-making process refers to how the patient and the doctor actively participate in the treatment decision-making process (34). Their objective is to exchange relevant information, balance risks, and benefits, and reach a common understanding of which treatment option is best for this individual (34). This study showed that involving patients in their own care helps improve their care quality. Contrary to studies showing that cancer patients’ trust does not change with SDM (41), we found that more involvement in decision-making correlates with higher trust towards doctors as a source of information. However, we found that shared decision-making does not support their self-efficacy. In fact, although SDM has benefits, it may also pose risks resulting from cognitive biases and undue influence of patients’ environments (42). It inherently assumes that patients are capable of taking in complex information from providers at the most vulnerable time in their lives and sensitizing it to make rational choices and decisions (42). Fear or responsibility can, thus, confuse the patients to take care of themselves instead of improving their self-efficacy.

Emotional Support and Uncertainty

Effective relationship based on emotional bonding is critical in cancer care (43). During their illness, cancer patients experience several physical, mental, psychological, and social problems (44). Emotional support is essential in safe, high-quality patient and family-centered care (45,46). This study showed that emotional support and helping patients with uncertainty could improve the quality of cancer care and patients’ trust in doctors. It is critical for healthcare organizations to embed emotional support in the care process since it would improve the patient experience, enhance the effectiveness of services, improve the working culture of health professionals, and prevent clinician burnout. Health organizations need to provide appropriate structures and processes for staff to deliver emotional support.

Technology use in PCC

Some healthcare organizations worldwide provide patients with online access to their electronic medical records (EMRs) to involve them in healthcare processes (47). Patients’ access to their EMRs serves as a cornerstone in the efforts to increase engagement and improve outcomes (48). Despite findings from other studies showing that EMRs play a supporting role for patients in cancer care (48). we found that offering access to EMRs did not help improve the impact of PCC on patients’ outcomes in this study. A study published by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology shows patients who recently were diagnosed with cancer view their EHR data at higher rates than those who never were diagnosed with cancer or survivors. However, they are still not viewing their records at a very high rate (49). A higher percentage of individuals with a recent cancer diagnosis experienced gaps in information exchange than individuals with no previous cancer diagnosis (49). Future studies should explore how to leverage technologies to better support patient-centered communication in cancer care.

Limitations

Our study has a few limitations. HINTS is a cross-sectional survey. It evaluates measures related to cancer communication, HIT, the prevalence of diseases, and perceived risks of cancer over time. As a result, it provides an overview of perceptions in a defined population. Future studies should consider the same approaches and interventions to gather longitudinal data to generate a more robust outcome. Finally, missing values (nonresponses) in cross-sectional studies can lead to bias in the outcome, particularly when nonresponders have far different characteristics from respondents.

Conclusion

According to our study, PCC impacts cancer patients’ QOC, doctors’ trust, and self-efficacy. In addition, addressing feelings, understanding the following steps, clearly explaining, spending enough time with the patients, and managing uncertainty and involvement in decisions improved the QOC and doctors’ trust. However, PCC did not improve self-efficacy. These findings have implications for healthcare systems to train their doctors to improve PCC in cancer care. These institutions also need to provide support to PCC in cancer care. To ensure better results, patient-centered strategies should also consider various patients’ needs in cancer settings. Finally, organizations should build strategies that are goal-oriented, as standard strategies cannot induce the desired outcomes.

Acknowledgements

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research on the National Institute of Health under award number R15NR018965. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

ORCID iD: Onur Asan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9239-3723

References

- 1.Badr H, Carmack CL, Diefenbach MA. Psychosocial interventions for patients and caregivers in the age of new communication technologies: opportunities and challenges in cancer care. J Health Commun. 2015;20(3):328‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein RM, Street Jr RL. PCC in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. 2007.

- 3.McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, et al. Measuring PCC in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(7):1085‐95. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cegala DJ, Street Jr RL. Interpersonal dimensions of health communication. Handbook of Communication Science. 2010:401‐18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plsek P; Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC National Academies Pr, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oncology ASoC. The state of cancer care in America, 2016: a report by the American society of clinical oncology. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2016;12(4):339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff. 2010;29(8):1489‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf DM, Lehman L, Quinlin R, Zullo T, Hoffman L. Effect of PCCs on patient satisfaction and QOC. J Nurs Care Qual. 2008;23(4):316‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vos ML, van der Veer SN, Graafmans WC, et al. Implementing quality indicators in intensive care units: exploring barriers to and facilitators of behaviour change. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, Clauser SB, Oakley-Girvan I. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor's perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreitler S, Peleg D, Ehrenfeld M. Stress, self-efficacy and quality of life in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer. 2007;16(4):329‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marks R, Allegrante JP. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part II). Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(2):148‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lev EL, Owen SV. Counseling women with breast cancer using principles developed by Albert Bandura. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2000;36(4):131‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finney Rutten LJ, Hesse BW, St. Sauver JL, et al. Health self-efficacy among populations with multiple chronic conditions: the value of PCC. Adv Ther. 2016;33(8):1440‐51. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0369-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillen MA, De Haes HC, Smets EM. Cancer patients’ trust in their physician—a review. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(3):227‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seetharamu N, Iqbal U, Weiner JS. Determinants of trust in the patient–oncologist relationship. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5(4):405‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baier A. Trust and antitrust. Ethics. 1986;96(2):231‐60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mechanic D, Meyer S. Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(5):657‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skirbekk H. Negotiated or taken-for-granted trust? Explicit and implicit interpretations of trust in a medical setting. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy. 2009;12(1):3‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finney Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Skolnick VG, Davis T, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Data resource profile: the national cancer institute’s health information national trends survey (HINTS). Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(1):17‐17j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swoboda CM, Fareed N, Walker DM, Huerta TR. The effect of cancer treatment summaries on PCC and QOC for cancer survivors: a pooled cross-sectional HINTS analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(2):301‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanch-Hartigan D, Chawla N, Beckjord EI, et al. Cancer survivors’ receipt of treatment summaries and implications for PCC and QOC. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1274‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westat. Health information national trends survey 4 (HINTS 4): cycle 4 methodology report. National Cancer Institute Bethesda, MD; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elkefi S, Choudhury A, Strachna O, Asan O. Impact of health perception and knowledge on genetic testing decisions using the health belief model. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics. 2022;6:e2100117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess LM, Pohl G. Perspectives of quality care in cancer treatment: a review of the literature. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6(6):321‐9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levit LA, Balogh E, Nass SJ, Ganz P. Delivering high-quality cancer care: charting a new course for a system in crisis. National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper A, Gray J, Willson A, Lines C, McCannon J, McHardy K. Exploring the role of communications in quality improvement: a case study of the 1000 lives campaign in NHS Wales. J Commun Healthc. 2015;8(1):76‐84. doi: 10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodman J, Truss † C. The medium and the message: communicating effectively during a major change initiative. Journal of Change Management. 2004;4(3):217‐28. doi: 10.1080/1469701042000255392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner Journal. 2010;10(1):38‐43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q. 2001;79(4):613‐39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendick N, Young B, Holcombe C, Salmon P. Telling “everything” but not “too much”: the surgeon’s dilemma in consultations about breast cancer. World J Surg. 2011;35(10):2187‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leydon GM, Boulton M, Moynihan C, et al. Cancer patients’ information needs and information seeking behaviour: in depth interview study. Br Med J. 2000;320(7239):909‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greco C. Too much information, too little power: the persistence of asymmetries in doctor-patient relationships. Anthropol Now. 2020;12(2):53‐60. doi: 10.1080/19428200.2020.1826178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hahlweg P, Kriston L, Scholl I, et al. Cancer patients’ preferred and perceived level of involvement in treatment decision-making: an epidemiological study. Acta Oncol (Madr). 2020;59(8):967‐74. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1762926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. Br Med J. 2017;357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. Br Med J. 2012;345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Arora NK, et al. Association of actual and preferred decision roles with patient-reported QOC: shared decision making in cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):50‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hack TF, Degner LF, Watson P, Sinha L. Do patients benefit from participating in medical decision making? Longitudinal follow-up of women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer. 2006;15(1):9‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noteboom EA, May AM, van der Wall E, de Wit NJ, Helsper CW. Patients’ preferred and perceived level of involvement in decision making for cancer treatment: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncology. 2021;30(10):1663‐79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engelhardt EG, Smets EM, Sorial I, Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, Hillen MA. Is there a relationship between shared decision making and breast cancer patients’ trust in their medical oncologists? Med Decis Making. 2020;40(1):52‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldman AE. Cognitive biases, dark patterns, and the ‘privacy paradox’. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;31:105‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aghaei MH, Vanaki Z, Mohammadi E. Emotional bond: the nature of relationship in palliative care for cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020;26(1):86‐94. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_181_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rangachari D, Smith TJ. Integrating palliative care in oncology: the oncologist as a primary palliative care provider. Cancer J. 2013;19(5):373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tzelepis F, Sanson-Fisher RW, Zucca AC, Fradgley EA. Measuring the quality of PCCs: why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:831‐5. doi: 10.2147/ppa.S81975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heath C, Sommerfield A, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(10):1364‐71. doi: 10.1111/anae.15180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ricciardi L, Mostashari F, Murphy J, Daniel JG, Siminerio EP. A national action plan to support consumer engagement via e-health. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):376‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rexhepi H, Åhlfeldt R-M, Cajander Å, Huvila I. Cancer patients’ attitudes and experiences of online access to their electronic medical records: a qualitative study. Health Informatics J. 2018;24(2):115‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christian Johnson M. Access and Use of Electronic Health Information by Individuals with Cancer: 2017-2018.