Abstract

Dysfunction in the prefrontal cortex is commonly implicated in anxiety disorders, but the mechanisms remain unclear. Approach-avoidance conflict tasks have been extensively used in animal research to better understand how changes in neural activity within the prefrontal cortex contribute to avoidance behaviors, which are believed to play a major role in the maintenance of anxiety disorders. Here we first review studies utilizing in vivo electrophysiology to reveal the relationship between changes in neural activity and avoidance behavior in rodents. We then review recent studies that take advantage of optical and genetic techniques to test the unique contribution of specific circuits and cell types to the prefrontal cortical control of anxiety-related avoidance behaviors. This new body of work reveals that behavior during approach-avoidance conflict is dynamically modulated by individual cell types, distinct neural pathways, and specific oscillatory frequencies. The integration of these different pathways, particularly as mediated by interactions between excitatory and inhibitory neurons, represents an exciting opportunity for the future of understanding anxiety.

Keywords: Anxiety, avoidance, prefrontal cortex, rodent, oscillations, interneurons

1. Introduction

Anxiety represents a state of heightened arousal, enhanced vigilance, and general feelings of aversiveness (negative valence) in the absence of an immediate threat. In general, this emotional state is adaptive and promotes avoidance to protect individuals from potential dangers. In contrast, anxiety disorders are characterized by persistent, excessive, and inappropriate anxiety, leading to an impairment of daily life (Kroenke et al., 2007). According to large population-based surveys, 33% of the population are affected by an anxiety disorder during their lifetime (Bandelow and Michaelis, 2015). Despite the high prevalence, the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of anxiety disorders remains poorly understood. Current evidence from clinical and preclinical research suggests anxiety disorders arise from dysfunction in a set of highly interconnected neural circuits, of which the amygdala, ventral hippocampus (vHPC), and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) are key nodes (Calhoon and Tye, 2015; Duval et al., 2015). This review focuses specifically on the mechanisms by which neural activity in the mPFC, regulated by distinct circuits and distinct cell types, drives affective behavioral responses to potential environmental threats. In particular, we highlight the unique oscillatory frequencies, glutamatergic afferent regulation of neuronal network inhibition and the neural circuits mediating PFC top-down control of anxiety-related avoidance behaviors.

Given both the ethical and technical limitations that accompany the use of humans as experimental subjects, researchers have utilized animal models to make significant strides in understanding the precise neural mechanisms in the mPFC that contribute to dysfunctional avoidance behavior seen in anxiety disorders. Although anxiety is a subjective experience that cannot be directly measured in animal models, a diverse array of behavioral tasks has been implemented to quantify anxiety-related behavioral phenotypes. Comprehensive summaries with detailed explanations of these assays have been presented in previous literature (Lister, 1990; Belzung and Griebel, 2001; Kumar et al., 2013). As such, we will not discuss them in detail but instead, provide a brief overview of the most commonly referenced tests (Table 1). For this review, we focus exclusively on summarizing literature measuring unconditioned behavioral responses that are ethologically based, and can be grouped into exploratory and investigation-based tasks. Exploratory-based tasks exploit rodents’ innate aversion to exposed, illuminated environments and their inherent drive to explore novel environments. As such, they are often referred to as approach-avoidance conflict tests and involve exposing the rodent to an arena equipped with a “safe” or “aversive” zones. These tasks have high face validity in that excessive avoidance is a hallmark feature of many anxiety disorders. However, one confound is that these tasks alone cannot distinguish a reduced anxiety phenotype from increased novelty-seeking or impulsive approach behavior (Cryan and Holmes, 2005). Therefore, studies that find reduced avoidance behavior in these exploratory based tasks could follow up with tests for novelty-seeking or impulsivity to make more precise conclusions. Interaction-based paradigms examine naturally occurring social behaviors in rodents. Similar to approach-avoidance conflict, an experimental manipulation that reduces social behaviors may be interpreted as enhanced social avoidance. By testing rodents in both social interaction and exploratory-based avoidance tasks, researchers can determine if behavioral deficits seen in social tests are specific to social exploration or a more generalized avoidance phenotype. Finally, it is important to note avoidances behaviors in rodents have also been extensively studied using conditioned behavioral responses. However, the neural mechanisms driving conditioned behavior to known threats versus unconditioned behavior to potential threats may not be comparable.

Table 1.

An overview of the most common approach-avoidance conflict paradigms

| Paradigm | Behavioral test | Brief description | Referenced in studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploratory-based | Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) | A plus-shaped maze elevated from the ground is composed of two walled off, enclosed arms opposed by two open arms. Time spent in and entries into the open arms are quantified and an anxious phenotype is indicated by greater avoidance of the open arm (Pellow et al., 1985) | (Adhikari et al., 2010, 2011; Gunaydin et al., 2014; Soumier and Sibille, 2014; Adhikari et al., 2015; Felix-Ortiz et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Padilla-Coreano et al., 2016; Ferguson and Gao, 2018; Padilla-Coreano et al., 2019; Cunniff et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021) |

| Elevated zero maze | A modified version of the EPM that contains an elevated ring-shaped platform with two opposite enclosed quadrants and two open quadrants. This design removes the ambiguity associated with the central square of the EPM that intersects the open and closed arms, and is quantified in a similar manner to the EPM. | (Loewke et al., 2021) | |

| Open Field (OF) | A novel, illuminated arena composed of a central zone surrounded by a peripheral zone. Time spent in each zone is quantified, with more time spent in the periphery indicative of an anxious phenotype | (Likhtik et al., 2014; Soumier and Sibille, 2014; Adhikari et al., 2015; Felix-Ortiz et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Page et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021) | |

| Light-dark box | A box divided into two chambers connected by a small opening. One compartment is opaque, dark, and enclosed while the other is brightly lit and transparent. Time spent in the light and crossings between the light and dark zones are quantified, with less time spent indicative of an anxious phenotype (Bourin and Hascoet, 2003) | (Lee et al., 2019) | |

| Novelty suppressed feeding (NSF) | A food deprived animal exposed to food in a novel environment may experience latency to feed. A reduced latency to feed may indicate a decrease in anxiety (Merali et al., 2003) | (Soumier and Sibille, 2014; Padilla-Coreano et al., 2016; Hare et al., 2019; Page et al., 2019) | |

| Interaction-based | Home cage social interaction (Toth and Neumann, 2013) | A juvenile mouse is placed into the home cage of a test mouse | (Felix-Ortiz et al., 2016) |

| Crawley’s three-chambered sociability test (Toth and Neumann, 2013) | A box divided into three chambers, a neutral center chamber opposed by two chambers with holding cups, with one cup providing indirect access to a novel mouse. | (Ferguson and Gao, 2018) |

Using approach-avoidance conflict tasks, researchers have extensively studied the role of mPFC activity in driving anxiety-related behaviors in rodents in combination with other classic methodologies such as lesions, pharmacological manipulations, and electrical stimulation. The results of these studies were a wealth of conflicting evidence, summarized in Table 2. For example, lesion studies and pharmacological experiments demonstrated that inactivation of the mPFC can increase (Jinks and McGregor, 1997; Lisboa et al., 2010), decrease (Maaswinkel et al., 1996; Lacroix et al., 2000; Sullivan and Gratton, 2002; Shah and Treit, 2003; Shah et al., 2004; Goes et al., 2018) or have no effect (Lacroix et al., 2000; Corcoran and Quirk, 2007; Fitzpatrick et al., 2011) on avoidance behaviors. Thus, the role of the mPFC in promoting these behaviors has remained elusive. One possibility is that the contradictory findings result from differential effects of the various manipulations on distinct pathways and cell types within the mPFC (see next section). The advancement and development of technologies for measuring and manipulating discrete neuronal populations have opened new possibilities for testing this idea with unprecedented temporal and spatial resolution. Advances in technology for in vivo recording and neuronal activity imaging within the freely moving rodent and the development of sophisticated techniques for manipulating neurons based on their genetics or projection target have greatly enhanced our ability to interrogate the relationship between mPFC neural activity, connectivity, and regulation of avoidance behaviors.

Table 2.

Lesion and inactivation studies on the mPFC in exploratory and interaction-based tests

| Strain, species and sex | Treatment | Tests | Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wistar rats, male | 0.09 M quinolinic acid, mPFC | Hole board | Increase exploration | (Goes et al., 2018) |

| Sprague Dawley rats, male | 2% lidocaine HCl, PL or IL | Open field | No effect either PL or IL | (Fitzpatrick et al., 2011) |

| Wistar rats, male | 1mM CoCl2, mPFC | Elevated plus maze, light-dark box | Decrease exploration | (Lisboa et al., 2010) |

| Sprague Dawley rats, male | 0.5ng/0.30μl TTX, PL | Open field | No effect | (Corcoran and Quirk, 2007) |

| Sprague Dawley rats, male | 0.175 or 4 nmol/0.5μL muscimol (GABA-A receptor agonist), mPFC | Elevated plus maze | Increase exploration | (Shah et al., 2004) |

| Sprague Dawley rats, male | Ibotenic acid, mPFC | Elevated plus maze, social interaction | Increase exploration and interaction | (Shah and Treit, 2003) |

| Long-Evans rats, male | Ibotenic acid, mPFC | Elevated plus maze | Increase exploration in right lesioned rats | (Sullivan and Gratton, 2002) |

| Wistar rats, male | Ibotenic acid, mPFC | Elevated plus maze, open field | Increase exploration | (Lacroix et al., 2000) |

| Wistar rats, male | Electrolytic lesion (1.0mA for 10s), PL or IL | Elevated plus maze, open field | Decrease exploration | (Jinks and McGregor, 1997) |

| Wistar rats, male | NMDA lesion, PL | Elevated plus maze, open field | Increase exploration in open field only | (Lacroix et al., 1998) |

| Wistar rats, male | Thermolesion (70°C for 60s), PL | Elevated plus maze, open field | Increase exploration in elevated plus maze only | (Maaswinkel et al., 1996) |

II. Definition, anatomy, and physiology of the rodent prefrontal cortex

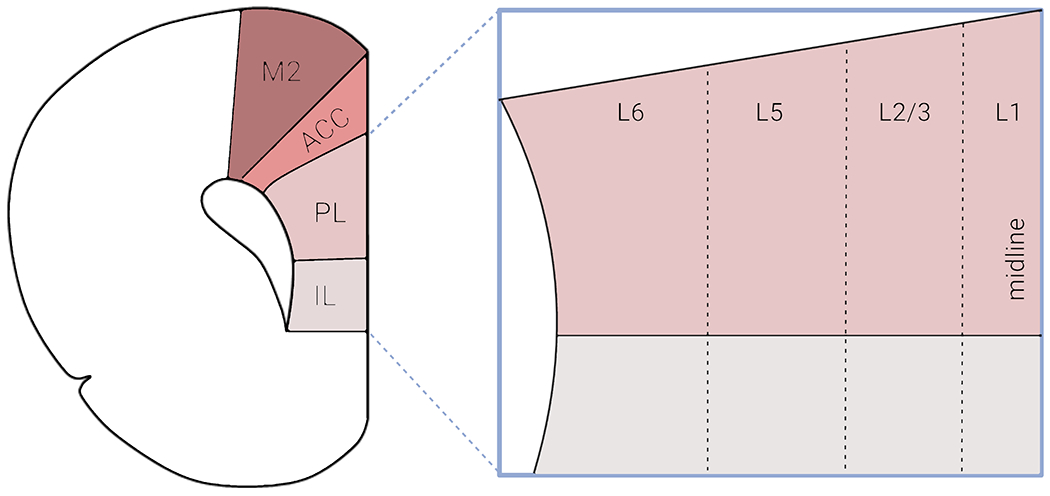

The definition and organization of the rodent mPFC provide an important framework for this review. Located in the frontal lobe, the rodent mPFC is divided into multiple subregions based on connectivity, cytoarchitectural, and functional differences. However, the inclusion and terminology of the various subregions remains a debated topic (Laubach et al., 2018). In this review, we use the term ‘mPFC’ in reference to studies targeting the prelimbic (PL) and infralimbic (IL) cortices, neighboring structures with the PL lying just dorsal to the IL (Figure 1). Despite the similar laminar structures, the PL and IL may be distinguished by differential connectivity with subcortical brain regions (Vertes, 2004; Van De Werd et al., 2010). It is important to note that functional differences have been ascribed to the PL and IL subregions, for example, in terms of fear-conditioned behavior (Sierra-Mercado et al., 2011). However, similar efforts have not been made to define these subregions’ distinct contributions to innate avoidance behaviors discussed herein, and those studies that do are explicitly noted.

Figure 1.

Organization of the rodent medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Schematic depicting a coronal section of the mouse brain and the four major subdivisions typically referred to when using the term ‘mPFC’ – secondary motor cortex (M2), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), prelimbic cortex (PL) and infralimbic cortex (IL). In this review paper, a majority of the papers cited focused exclusively on the PL and IL subregions. The PL and IL are laminarly organized, with layers 1, 2/3, 5 and 6. Rodents lack a prominent layer 4 compared to human and non-human primates. Created with BioRender.com

Like other neocortical regions, the rodent mPFC is a laminarly organized area composed of layers I-VI (Caviness, 1975; Van De Werd et al., 2010), although rodents lack a prominent granular layer IV compared to humans and non-human primates (Uylings and van Eden, 1990; Uylings et al., 2003) (Figure 1). Across these layers, information processing occurs via complex interactions among numerous cell types that can be broadly grouped into two categories: excitatory glutamatergic pyramidal neurons and inhibitory GABAergic interneurons (IN), which account for ~80% and ~20% of the neuronal population, respectively (Gabbott et al., 1997). While the pyramidal neurons propagate signals within the mPFC and to various other brain regions, the GABAergic INs exert tremendous regulatory influence over signal flow within individual and networks of mPFC pyramidal neurons (Isaacson and Scanziani, 2011). Both pyramidal and interneurons can be divided into unique subclasses based on a number of defining features such as cell morphology, physiology, molecular marker expression, or connectivity (DeFelipe and Farinas, 1992; Yang et al., 1996; Gee et al., 2012; Tremblay et al., 2016).

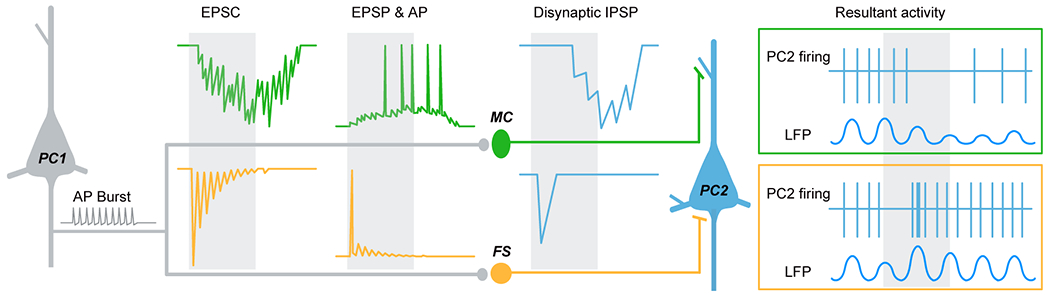

Nearly 100% of cortical GABAergic INs express one of these non-overlapping molecular markers: the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin (PV+), the neuropeptide somatostatin (SST+), or the ionotropic serotonin receptor 5HT3a (5HT3aR+) (Lee et al., 2010; Tremblay et al., 2016). Extensive heterogeneity exists across the IN populations in intrinsic physiological properties and subcellular targeting biases. These unique features offer tremendous diversity in terms of interneuron modulation of pyramidal cell activity (Tremblay et al., 2016). By innervating the perisomatic region of pyramidal cells, PV+ interneurons exert a powerful influence over the output of their target neurons (Naka and Adesnik, 2016). PV+ interneurons receive excitatory-postsynaptic inputs with short-term depression (STD) during burst firing in pyramidal cells (PCs), providing potent inhibition at the burst onset (Lu et al., 2014). This onset-transient inhibition becomes even more powerful when a group of presynaptic excitatory neurons fires action potentials (APs) simultaneously. Therefore PV+ INs may work as a “coincidence detector” during mPFC network activity as reported in the hippocampus and sensory cortex (Pouille and Scanziani, 2004; Silberberg, 2008). On the other hand, SST+ INs preferentially target distal apical dendrites of PCs to modulate the gain of inputs terminating within those subcellular regions (Naka and Adesnik, 2016). SST+ INs receive excitatory synaptic inputs with short-term facilitation (STF), thus providing inhibition to PCs at late stages of the PC burst (Kapfer et al., 2007; Silberberg, 2008; Zhu et al., 2011). In addition, the excitatory synapses onto SST INs also show prolonged asynchronous release (AR) of glutamate, leading to the occurrence of late and persistent barrages of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) in their downstream targets. The strength of these IPSPs depends on the intensity of PC activities. Therefore, SST+ IN firing and the resultant IPSPs could be desynchronized by the asynchronous glutamate release, especially when a high-frequency burst occurs in PCs (Deng et al., 2020). Altogether, these distinct interneuron populations exert tremendous influence over information processing in the mPFC through their corresponding regulation of PC activity (Wester and McBain, 2014; Amilhon et al., 2015) (Figure 2). In section V, we review a recent body of literature that has found effects on avoidance behavior in mice after disrupting activity in PV+ and SST+ INs, and also INs expressing vasointenstinal peptide (VIP+), which share about 40% overlap with 5-HT3aR-expressing INs.

Figure 2.

Differential modulation of pyramidal cell (PC) activity by two types of interneurons. An AP burst in PC (grey) causes both synchronous and asynchronous release (AR) of glutamate at synapses onto SST+ Martinotti cell (MC, green). Synchronous release produces facilitating EPSCs/EPSPs and thus delayed AP firing in MC, while the occurrence of delayed AR desynchronizes and prolongs MC firing, resulting in imprecise and long-lasting inhibition in neighboring PCs (blue). This late-onset slow recurrent inhibition would decrease and desynchronize PC firing for a long period of time, presumably causing a reduction of LFP power (green box). In contrast, the PC burst only causes synchronous release at synapses onto PV+ fast-spiking cells (FS, orange). Because of the strong short-term depression, the initial EPSC/EPSP is normally large in size, resulting in a transient discharge in FS cell and thus early-onset inhibition in neighboring PCs. The sudden presence and withdrawal of this fast recurrent inhibition may enhance the synchronization of downstream PCs, thus increasing the LFP power (orange box). Grey shadows indicate the time window of AP burst of PC1. The figure was modified with permission from Deng and others 2020.

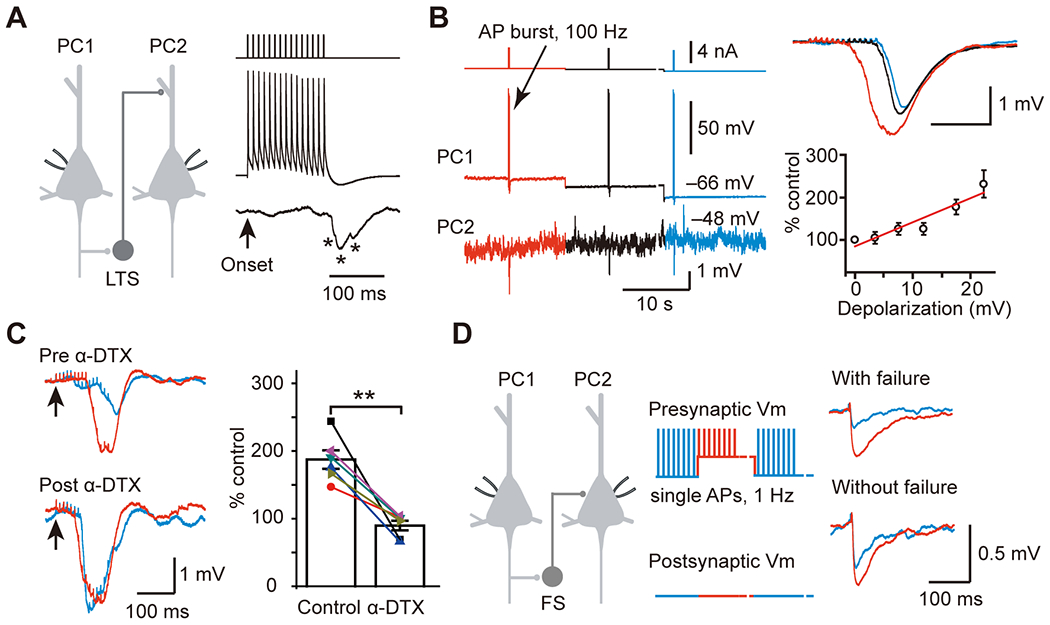

Furthermore, the timing and magnitude of inhibition are also dependent on presynaptic PC Vm state (depolarization or hyperpolarized) associated with rhythmic network oscillations. A single electrical stimulation at a depolarized Vm state will evoke larger and more prolonged inhibition, a potential mechanism for the cessation of an active cortical state. An additional mechanism is that the higher probability of AP generation after the electrical stimulus would cause higher synchronization of spiking activities in PCs (Shu et al., 2003). In comparison with hyperpolarized Vm levels, spikes generated at a depolarized Vm level could induce EPSPs with greater amplitude, and the size of EPSPs is positively linked to presynaptic Vm depolarization levels (Alle and Geiger, 2006; Shu et al., 2006). Thus, it is plausible that PC Vm states also regulate the size and timing of disynaptic inhibition mediated by the two recurrent-inhibition microcircuits, PC→PV→PC and PC→SST→PC (Figure 3) (Zhang et al., 2021). Moreover, axonal Kv1 channels contribute to the Vm-dependent modulation of axonal AP waveform (Shu et al., 2006; Shu et al., 2007) and thus the size of EPSPs in GABAergic interneurons and consequently the size of IPSPs in postsynaptic PCs (Figure 3C) (Zhu et al., 2011). The delicate balance of excitation and inhibition within the mPFC network, termed E/I balance, shaped by is crucial for optimal behavioral performances, including anxiety-related avoidance behavior (Yizhar et al., 2011; Ferguson and Gao, 2018).

Figure 3.

Membrane potential-dependent modulation of recurrent inhibition. A. AP burst (15 APs at 100 Hz) in PC1 induced low-threshold spiking (LTS) cell-mediated slow disynaptic inhibition in PC2. LTS cells are putative SST+ interneurons. * indicates individual IPSPs. Arrow indicates the onset of AP burst in PC1. B. Example PC-PC paired recording showing that the amplitude of slow disynaptic IPSPs was associated with presynaptic Vm levels (color-coded: red represents Vm near the AP threshold, blue represents Vm at the resting membrane potential). Group data show that the peak amplitude of IPSPs is positively correlated with the presynaptic membrane potential depolarization (bottom right). C. Bath application of a KV1 channel blocker α-dendrotoxin (α-DTX, 100 nM) mimicked the depolarization-induced increases of slow disynaptic IPSPs (left, blue) and occluded the increased IPSCs induced by PC depolarization (left, red). Group data indicate no significant additional increases in the amplitude of disynaptic IPSPs after α-DTX application (right). D. The amplitude of fast disynaptic IPSC mediated by FS also depended on presynaptic Vm levels. This figure was modified with permission from Zhu and others 2011.

In addition to mPFC network activity being shaped by diverse classes of INs, the mPFC receives a multitude of long-range excitatory inputs from regions such as, but not limited to, the hippocampus, insular cortex, basal amygdala nuclei, and midline thalamic nuclei (Hoover and Vertes, 2007). The mPFC also receives non-glutamatergic neuromodulatory input from the ventral tegmental area, locus coeruleous, dorsal raphe, and basal forebrain, as reviewed elsewhere (Gao et al., 2021; Yan and Rein, 2021). In return, the mPFC sends robust long-range projections to numerous cortical and subcortical brain regions. Subcortical projecting PCs are localized in deep layers V/VI, whereas cortical projecting PCs are predominately found in superficial layer II/III (Douglas and Martin, 2004). PCs account for a majority of the long-range projection neurons in the mPFC, although a class of long-range GABAergic projections targeting the nucleus accumbens (NAc) was recently identified (Lee et al., 2014). Importantly, the mPFC projects to many brain regions that are implicated in emotional and autonomic control, such as the amygdala, midline thalamic nuclei, the habenula, the striatum, the lateral hypothalamus, and the periaqueductal gray (Vertes, 2004; Gabbott et al., 2005). Therefore, anatomically, the mPFC is a well-positioned hub to guide affective behavioral responses to perceived environmental challenges.

III. Neural recordings in the mPFC

The application of in vivo electrophysiology in behaving animals during approach-avoidance conflict has provided insight into the changes in neural activity within the PFC during exposure to anxiety-provoking environments, from the level of a single neuron to communication across brain regions. In addition, advances in both the size and stability of recording devices have enabled researchers to interrogate both single-unit activity and local field potentials (LFPs), which has allowed assessment of neural spiking and summations of rhythmic neural activity, or neural oscillations in behaving animals (Hong and Lieber, 2019).

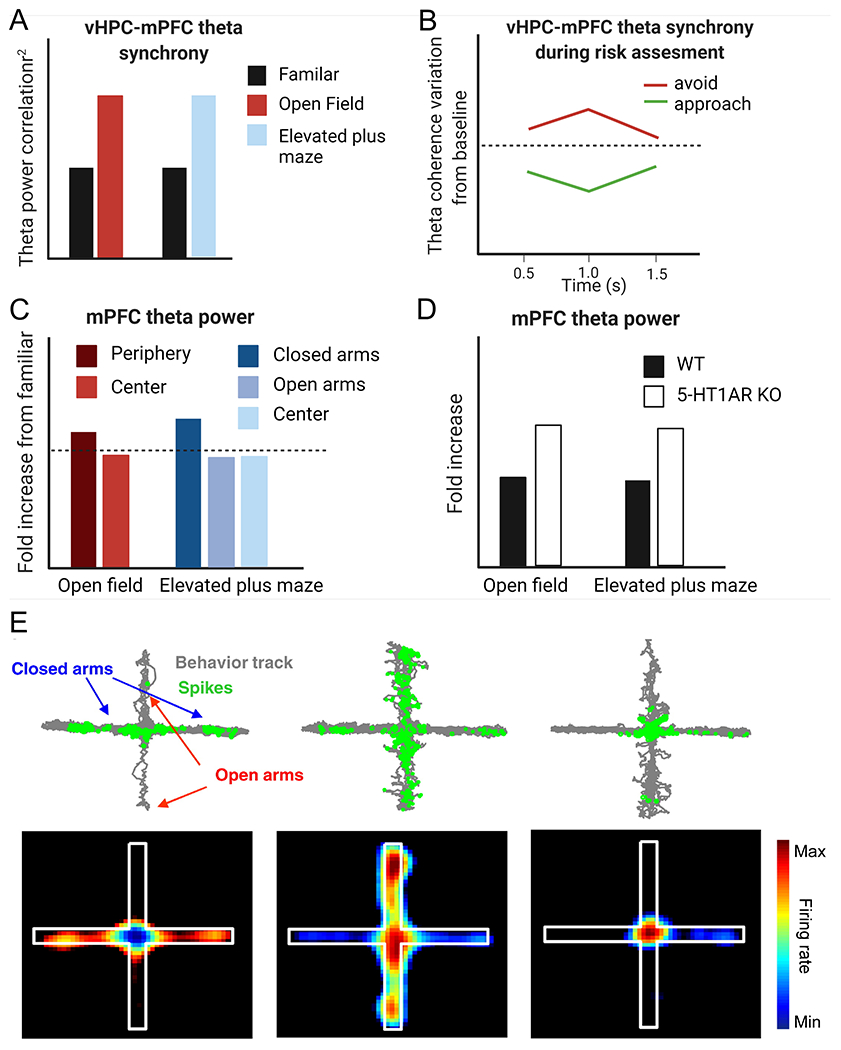

Local field potentials reveal distinct oscillatory changes in the theta-frequency range during approach-avoidance conflict within mPFC circuits

Local field potential (LFP) recordings suggest a high degree of synchrony between the mPFC and the vHPC and the basolateral amygdala (BLA) during the approach-avoidance conflict. The vHPC and mPFC show increased oscillatory synchrony specifically in the theta frequency range (4-12 Hz) during exposure to the open field (OF) or elevated plus maze (EPM) (Adhikari et al., 2010; Jacinto et al., 2016; Cunniff et al., 2020) (Figure 4A). Some studies have shown that vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony increases specifically as mice leave the closed arm and approach the center of the EPM, which may be interpreted as approaching the more anxiogenic regions of the environment (Adhikari et al., 2010; Cunniff et al., 2020). This increase in theta synchrony is absent in mice heterozygous for Pogz (Pogz+/−), a high confidence autism gene (Cunniff et al., 2020). Pogz+/− mice also display reduced anxiety-related avoidance behavior in the EPM, suggesting that heightened vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony may drive this behavior. One study analyzed and compared vHPC-mPFC synchrony during risk-assessment behavior in the EPM by quantifying front paws’ entries and head dips into the open-arm, and found synchrony changes in either full entry into the open-arm (approach action) or retreated into the closed arm (avoidance action) (Jacinto et al., 2016). Interestingly, vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony showed opposing patterns during risk assessment, depending on whether the future action was to approach or avoid the open arms such that avoidance actions were associated with increased vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony while approach actions were associated with a decrease (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

In Vivo neural recordings reveal distinct changes in the mPFC during approach-avoidance conflict. A) vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony is significantly increased in the open field and elevated plus maze (EPM) relative to a familiar environment. B) The change in vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony during risk assessment depends on whether the animals’ future action is to approach (green) or avoid (red). C) Fold increase in mPFC theta power compared to a familiar environment is significantly increased in the more anxiogenic regions (periphery of open field and open arms of elevated plus maze) relative to the other zones. D) mPFC theta power during exposure to the open field or EPM is significantly greater in 5-HT1A KO mice relative to wild-type control mice. E) mPFC single units have task-related firing patterns in the EPM. Upper panel: The gray represents the animals’ track in the EPM, and the green represents the spatial distribution of single units that preferentially fired in the closed arms (left), open arms (middle), or center (right) of the EPM. The lower panel is the spatial firing map of the same single units. Part A, C, and D were modified with permission from Adhikari and others 2010, Elsevier. Part B was modified with permission from Jacinto and others, 2016. Part E was modified with permission from Adhikari and others 2011, Elsevier. Panels A-D were created with BioRender.com.

In contrast to the theta power in the vHPC, which is elevated in a non-specific manner during approach-avoidance conflict tasks, theta power in the mPFC is specifically increased while mice explore the “safer zones” such as the protected periphery of an OF or the enclosed arms of the EPM (Adhikari et al., 2010) (Figure 4C). Moreover, the magnitude of increased mPFC theta power correlates with open arm avoidance, and it is more prominent in serotonin receptor 1A knockout 5HT1AR KO mice (Figure 4D), which serve as a genetic mouse model of anxiety (For a detailed discussion of serotonin regulation of the mPFC and its relation to anxiety, readers are directed to the following reviews (Puig and Gulledge, 2011; Albert et al., 2014)). Another study showed that local infusion of a 5-HT1B receptor agonist into the mPFC reduces theta power and reduces open-arm avoidance in the EPM (Kjaerby et al., 2016). Thus, mPFC theta power may specifically inhibit exploratory behavior (but see (Jacinto et al., 2016)) and evidence suggests this may occur through interactions with BLA (Likhtik et al., 2014). As avoidant mice (those who spend <10% of the time in the center of the OF) move from the center to the periphery of the OF, BLA field potentials and spiking activity entrain to mPFC theta while BLA firing rates decrease (Likhtik et al., 2014). Therefore, theta rhythms originating within the PFC may encode a safety signal to the BLA (Calhoon and Tye, 2015). Collectively, these studies demonstrate a dynamic interplay of theta oscillations and mPFC interactions with the vHPC and BLA that change based on animals’ decisions to approach or avoid.

mPFC neurons show task-related firing patterns with single-unit activity recording in the EPM

Utilizing in vivo recordings in mice, another study characterized single unit PFC neural activity during the approach-avoidance conflict in the elevated plus maze (EPM) (Adhikari et al., 2011). Within the deep layers of the PL subregion, they found that 42% of recorded neurons encoded task-related features of the maze. Some neurons preferentially fired in the open arms while others preferentially fired in the closed arms or the center (Figure 4E). Neurons that fired in the open arm of an EPM also fired when the enclosed arm was made aversive in bright light, suggesting that PFC neurons encode aversive features in the environment rather than just location (Adhikari et al., 2011). The emergence of task-specific firing patterns during the approach-avoidance conflict in the EPM supports the proposed hypothesis that the PFC evaluates possible outcomes in the presence of competing drives (Ridderinkhof et al., 2004; Bissonette et al., 2013; Saunders et al., 2017).

Moreover, mPFC units that phase-lock to vHPC theta have more robust task-related firing patterns in the EPM, suggesting that vHPC inputs may support the mPFC to construct representations of the anxiety-provoking environment. Intriguingly, in both avoidant wild-type mice (those that spend <50% total time in the open arm) and 5-HT1AR KO mice, mPFC neurons failed to differentiate between the open and closed arms. These data suggest that in avoidant animals, mPFC representations of safe and aversive features are not used to guide behavior during the approach-avoidance conflict as these representations do not exist (Adhikari et al., 2011). One possible explanation of this data is that avoidant mice generalize – the entire maze is seen as a threat, leading to a decreased ability to discriminate between the open and closed arms. Another possibility is that, under conditions of low anxiety (non-avoidant animals), the mPFC may utilize encoding of safety and aversion to guide exploratory behavior during approach-avoidance conflict. Under conditions of high anxiety (avoidant animals), the mPFC fails to encode valence-related features of the environment, leading to the expression of anxiety-related phenotypes such as open arm avoidance. However, manipulations that have disrupted mPFC encoding of task related features in the EPM have resulted in anxiolysis(Padilla-Coreano et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2019), making this explanation less likely.

IV. Optogenetics and chemogenetics: causal mechanisms of prefrontal control of anxiety

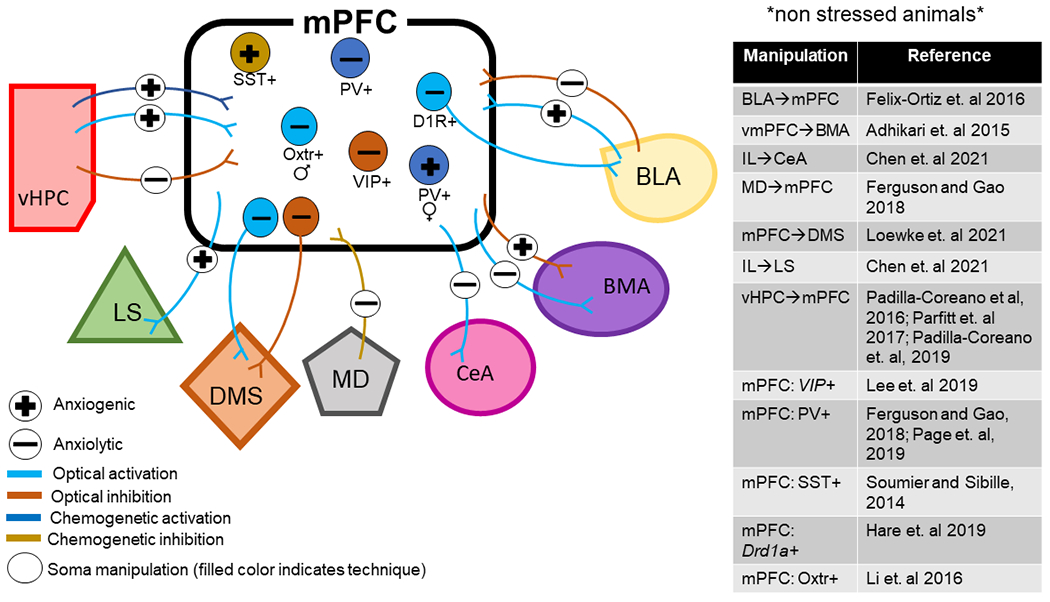

While the studies mentioned above provided substantial insight into the role of the mPFC in regulating anxiety-related behaviors, electrophysiology studies are only correlative and lack genetically defined cellular specificity. As such, these techniques cannot elucidate the causal roles of the specific neural activity and the contribution of distinct neural pathways and cell types. The development of tools enabling manipulation (e.g., optogenetics, chemogenetics) and monitoring (e.g., fiber photometry, two-photon for calcium imaging) genetically defined populations of cells have greatly expanded the scientific toolkit. This section reviews recent studies utilizing these techniques to highlight the causal roles of various prefrontal circuits and cell types in modulating anxiety-related avoidance in rodents. The application of these new tools has revealed that mPFC regulation of avoidance behavior is likely pathway and cell-type specific (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Circuits and cell types of the rodent medial prefrontal cortex play a causal role in behavior during approach-avoidance conflict. BLA – basal lateral amygdala; BMA – basomedial amygdala; CeA – central amygdala; D1R – dopamine receptor subtype 1; DMS – dorsal medial striatum LS – lateral septum; MD – mediodorsal thalamus; mPFC – medial prefrontal cortex; Oxtr – oxytocin receptor; PV – parvalbumin; SST – somatostatin; vHPC – ventral hippocampus; VIP – vasointestinal peptide. Anxiogenic, or producing anxiety, is used in reference to studies where manipulations increased avoidance behaviors whereas anxiolytic, or reducing anxiety, is used in reference to studies where manipulations decreased avoidance behaviors.

Ventral Hippocampus – Prefrontal Pathway

The ventral hippocampus (vHPC) has long been associated with the regulation of behavior during approach-avoidance conflict (Bryant and Barker, 2020). The vHPC sends dense projections to both PL and IL subregions of the rodent prefrontal cortex (Vertes, 2004; Hoover and Vertes, 2007). These projections are known to be glutamatergic and can drive both feedforward excitation and inhibition in multiple interneuron subtypes and distinct projection neurons across different layers of the PL and IL cortices (Abbas et al., 2018; Liu and Carter, 2018; Marek et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019). However, evidence from the combination of ex vivo electrophysiology and optogenetic techniques suggests that vHPC afferents preferentially activate cortico-cortical L5 neurons in the IL, indicating that the primary effect of activating vHPC inputs to the mPFC is excitation of the IL subregion (Liu and Carter, 2018).

Through a combination of optogenetics and in vivo electrophysiological recordings, a technique known as photo-tagging, one study revealed that mPFC-projecting vHPC neurons are enriched with information about the safe and aversive features in the anxiety-provoking environments (Ciocchi et al., 2015). Targeted photoinhibition or chemogenetic inhibition of vHPC terminals in the mPFC decreases anxiety-related avoidance in the EPM, OF, and novelty suppressed feeding (NSF) tests (Padilla-Coreano et al., 2016; Parfitt et al., 2017). Additionally, optical inhibition of vHPC→mPFC reduces theta synchrony in this circuit and ablates mPFC task-specific firing patterns in the EPM (Padilla-Coreano et al., 2016). On the other hand, chemogenetic activation of the vHPC→mPFC pathway enhances anxiety-related phenotypes (Parfitt et al., 2017). To study the causal role of vHPC→mPFC communication in the theta frequency range in regulating avoidance behaviors, Padilla-Coreano and colleagues (Padilla-Coreano et al., 2019) utilized optogenetics to mimic naturally occurring oscillations by delivering light of varying frequencies in either a continuous oscillatory sinusoidal or pulsatile pattern to vHPC terminals in the mPFC expressing an excitatory opsin. They found that oscillatory (but not pulsatory) stimulation of mPFC projecting vHPC neurons at 8 Hz (rather than 2 Hz or 20 Hz) increased open arm avoidance in the EPM and maximally enhanced vHPC→mPFC synchrony and transmission (Padilla-Coreano et al., 2019). Moreover, 8-Hz oscillatory stimulation enhanced phase locking of mPFC neurons to vHPC theta specifically in the open arms, the aversive zones. These findings combined with prior results (Padilla-Coreano et al., 2016; Parfitt et al., 2017) demonstrate that vHPC inputs to the mPFC exert bidirectional control over anxiety-related avoidance behaviors, and that theta frequency activity in this circuit conveys an anxiogenic signal and plays an important role in sustaining information transfer during the approach-avoidance conflict.

Prefrontal ↔ Amygdala Pathways

The amygdala plays a major role in determining whether environmental stimuli are interpreted as a threat. Much like the mPFC, the amygdala is a heterogeneous brain region composed of multiple interconnected nuclei that are functionally and morphologically distinct. Broadly, the amygdala can be divided into the BLA [consisting of a lateral (LA), basal (BA), and basomedial (BM) nuclei and the central amygdala (CeA; made up of the lateral and medial subdivisions)]. In contrast to the vHPC→mPFC circuit, early tract tracing studies demonstrated reciprocal connectivity between the mPFC and the amygdala. Long-range afferent input from the amygdala to the mPFC comes from the BLA exclusively, whereas the mPFC sends top-down projections to multiple amygdala nuclei such as the BA, BM, and CeA. While both the PL and IL subregions project to the BLA and CeA, only the IL predominately innervates the basomedial amygdala (BMA) (Vertes, 2004; Gabbott et al., 2005)

Similar to the vHPC and the mPFC, a subset of neurons within the BLA have been shown to track anxiety-like behavior in the EPM and OF (Wang et al., 2011), but it remains unknown whether these anxiety-encoding BLA cells communicate with subregions of the mPFC. Optical activation of BLA terminals in the mPFC increased avoidance in the EPM, OFT, and home cage social interaction, whereas inhibition elicits the opposite effects (Felix-Ortiz et al., 2016). While this study did not differentiate between BLA inputs to the PL versus the IL subregions of the mPFC, recent evidence suggests that BLA afferents form anatomically distinct connections within the PL and IL subregions, and also play functionally different roles in conditioned fear expression and extinction (for a detailed review, see (Giustino and Maren, 2015)). Thus, resolving the specific functional roles of BLA inputs to the PL versus the IL in unconditioned avoidance behaviors may reveal unique findings. Although BLA afferents are glutamatergic, activation of BLA-mPFC neurons may drive anxiety-related avoidance through feedforward inhibition in the PFC local circuits. Indeed, evidence suggests optical activation of BLA inputs can drive both feedforward excitation and inhibition (Little and Carter, 2013; Cheriyan et al., 2016; McGarry and Carter, 2016). However, the predominate influence appears to be inhibitory, specifically through the recruitment of PV+ and SST+ interneurons (McGarry and Carter, 2016). Interestingly, PV+ and SST+ interneurons that receive afferent input from the BLA directly innervate mPFC neurons that project back to the BLA, raising the possibility that activation of BLA-mPFC circuitry may drive innate avoidance through feedforward inhibition that results in less mPFC output back to the BLA. However, this assumption has not been tested directly.

A recent study tested mPFC top-down control of anxiety via the amygdala in mice by targeting PCs in the dorsal mPFC (cingulate cortex and rostral PL) and the ventral mPFC (ventral IL and peduncular cortex) with an excitatory or inhibitory opsin and an optical fiber above the amygdala. They found that vmPFC-amygdala neurons, but not dmPFC-amygdala neurons, exert bidirectional control over anxiety-related phenotypes during approach-avoidance conflict (Adhikari et al., 2015). Specifically, vmPFC-amygdala activation resulted in reduced open arm avoidance and decreased respiratory rate in the EPM and OF, whereas inhibition had the opposite effects. However, this study also raised questions about the mechanisms behind these findings. By looking at fluorescent-labeled axon terminals in the amygdala, the authors concluded dmPFC primarily innervates the BLA, whereas the vmPFC primarily innervates the BMA. Based on this, they proposed that vmPFC regulation of the BMA mediates the observed anxiety-related phenotype. However, directly inhibiting BM-projecting vmPFC neurons using an intersectional viral approach was not able to recapitulate the phenotype observed when manipulating vmPFC terminals in the amygdala. These results suggest that some other nuclei besides the BM may mediate the anxiolytic effects of vmPFC inhibition in the amygdala.

Interestingly, a recent study specifically injected an excitatory or inhibitory opsin in the IL subregion of the mPFC, and stimulated axon terminals in the CeA. They found that optical activation decreased anxiety-related avoidance in the EPM and OF test, while inhibition had an opposite effect (Chen et al., 2021). Another study showed that optogenetic excitation of dopamine receptor D1 (DRD1)-expressing neurons in the mPFC decreases avoidance behaviors in the EPM and NSF test 24 hours following stimulation. These effects are partially recapitulated by stimulating DRD1 mPFC neuronal terminals in the BLA (Hare et al., 2019). Altogether, the present data suggest enhancing mPFC top-down control of the amygdala reduces anxiety-related avoidance behaviors. However, more studies targeting specific mPFC and amygdala subregions using intersectional viral approaches are needed for a complete understanding of how this regulation occurs via distinct subregions in both the mPFC and the amygdala. Nevertheless, the present data provide strong evidence that reciprocal interactions between the amygdala and the mPFC play a causal role in regulating anxiety-related avoidance behaviors.

Extending outside the emotional triad: additional pathways beyond the hippocampus and amygdala

In addition to the vHPC and BLA, the mPFC receives extensive glutamatergic input from numerous thalamic nuclei. In particular, the mediodorsal thalamus (MD) input to the mPFC has been extensively studied for its role in cognitive behaviors such as working memory and cognitive flexibility. However, recent evidence from our lab also demonstrates a role for this pathway in regulating anxiety-related avoidance and social deficits (Ferguson and Gao, 2018). Specifically, chemogenetic inhibition of the MD alters the balance of excitation to inhibition (E/I balance) by decreasing inhibitory neurotransmission within the mPFC, resulting in decreased sociability and open arm avoidance in the EPM. Chemogenetic activation of PV+ interneurons in the mPFC rescued the behavioral deficits and restored E/I balance, suggesting that a loss of PV+ mediated inhibition underlies the reduction in sociability and anxiolytic effect of inhibiting the MD-mPFC pathway (Ferguson and Gao, 2018). Interestingly, optical inhibition of MD-mPFC afferents has no impact on anxiety-related behavior in mice, nor does it disrupt mPFC encoding task-related features in the EPM (Padilla-Coreano et al., 2016). The discrepancies in these results may be explained by the use of different techniques to manipulate the MD-mPFC circuit. While optogenetics achieves precise control of neuronal firing with brief pulses of light, chemogenetics provides the opportunity to modulate neuronal activity for several hours with the administration of a designer drug (Vlasov et al., 2018). Perhaps the longer time frame of MD inhibition achieved with chemogenetics is needed to disrupt the E/I balance in the mPFC (Ferguson and Gao, 2018), and in turn, regulate avoidance behaviors.

Nonetheless, taken together, the results suggest that MD inputs are not required for mPFC encoding of the anxiogenic environment, but MD-specific regulation of E/I balance through PV+ interneurons in the mPFC may modulate anxiety-related phenotypes. Furthermore, the mPFC forms strong reciprocal connections with the MD and many other thalamic nuclei that are important for emotional processing, such as the paraventricular thalamus (Barson et al., 2020). However, more work is needed to understand whether and how these pathways interact with the mPFC microcircuit to regulate avoidance behaviors.

Further, the mPFC sends dense glutamatergic projections to many brain regions implicated in anxiety disorders beyond the amygdala, such as the bed nucleus stria terminalis (BNST), the striatum, the lateral septum (LS), and the hypothalamus. Some studies have applied optogenetics to test the causal role of mPFC neurons that project to some of these brain regions. For example, a recent study showed that optical activation of mPFC terminals in the lateral septum (LS) increased open arm avoidance in the EPM, and interestingly this effect persisted beyond the period of light stimulation. Conversely, optical and chemogenetic inhibition of the IL→LS pathway decreased open arm avoidance, thus having an anxiolytic effect (Chen et al., 2021). At the same time, Loewke and colleagues reported that optogenetic stimulation of mPFC neurons that project to the dorsal medial striatum (DMS) decreased anxiety-related avoidance, whereas inhibition of these neurons increased avoidance (Loewke et al., 2021). Combined with the data from the mPFC→amygdala pathway, these findings show that activating different mPFC outputs (e.g., amygdala versus LS vs. DMS) can have opposing effects on behavior during approach-avoidance conflict. The fact that different mPFC neural circuits play unique roles in regulating behavior during approach-avoidance conflict may explain the contradictory findings between early studies using more generalized techniques to inhibit or excite the entire mPFC.

V. Cell-type-specific effects: unique classes of GABAergic INs exert distinct effects on anxiety

A diverse subpopulation of GABAergic INs is crucial for information processing within the mPFC by gating long-range afferent inputs and allowing for dynamic modulation of the gain of PC responses (see section II) and, in turn, regulation of multiple complex behaviors (Yang et al., 2021). A key question of interest that can now be addressed with newly emergent techniques is what distinct roles genetically defined populations of mPFC interneurons (INs) play in regulating prefrontal activity and subsequent anxiety-related behaviors. This section focuses on the differential contribution of mPFC IN subtypes expressing the molecular markers vasointestinal peptide (VIP+), somatostatin (SST+), and parvalbumin (PV+) to the innate avoidance behaviors.

Utilizing fiber photometry, a recent study recorded calcium transients from VIP+, SST+, or PV+ INs near the PL/IL border while mice explored the EPM (Lee et al., 2019). Their results showed that VIP+ INs displayed the strongest task-related firing patterns relative to SST+ and PV+ cells, with high firing rates seen in the center and open arms of the EPM. Importantly, optogenetic inhibition of VIP+ INs decreases anxiety-related avoidance only when stimulation is given within these zones. Using a dual-color microendoscope, which allows for simultaneous imaging of genetically encoded calcium indicators and delivery of light for optogenetic control, the authors showed that inhibiting VIP+ INs disrupts mPFC encoding of safe and aversive features of the EPM. Interestingly, the behavioral effects of optically inhibiting VIP+ cells in the EPM strongly correlated with the magnitude of disruption in mPFC representations of the EPM. Moreover, optical inhibition of VIP+ INs maximally decreases anxiety-related avoidance behavior when vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony is high (Lee et al., 2019). Therefore, vHPC theta rhythms may selectively recruit VIP+ INs to induce anxiety-related avoidance behaviors and support network-level representations of the EPM.

Although PV+ and SST+ INs were not found to track task-related features in the EPM as strongly as VIP+ INs, evidence suggests both PV and SST+ IN populations exert complex effects on behavior during approach-avoidance conflict. Unlike the disinhibitory effect of VIP+ cells, PV+ INs exert powerful inhibitory control over PC firing by synapsing at the perisomatic regions (Naka and Adesnik, 2016). One study demonstrated that acute activation of PV+ INs in male rats decreases open arm avoidance in the EPM utilizing an excitatory chemogenetic construct driven by a PV promotor (Ferguson and Gao, 2018). Conversely, utilizing transgenic PV-Cre mice, another study showed that chronic (but not acute) chemogenetic activation of PV+ INs increases avoidance behaviors the OF and NSF test of female mice exclusively (Page et al., 2019), suggesting that PV+ INs activity may differentially contribute to anxiety-related avoidance behaviors in males and females. At the same time, other studies have reported null effects of manipulating PV+ INs on behavior during approach-avoidance conflict (Yizhar et al., 2011; Bicks et al., 2020). Therefore, more research is needed to understand the nuanced ways PV+ INs may mediate distinct pathways in the mPFC to regulate anxiety-related avoidance behaviors.

Similarly, using transgenic SST-IRES-Cre mice and inhibitory chemogenetic tools, Soumier and Sibille (Soumier and Sibille, 2014) showed that acute versus chronic inhibition of SST+ INs in the PL subregion elicited opposing effects on anxiety-related behaviors. Specifically, acute chemogenetic inhibition of SST+ INs was anxiogenic in the EPM and NSF, whereas chronic inhibition elicited anxiolytic effects in these assays (Soumier and Sibille, 2014). Moreover, a subset of SST+ INs expressing oxytocin receptors in the PFC had been identified as functionally important exclusively in males but not females mice. Specifically, optical activation of these neurons enhances anxiety-related avoidance in the EPM and OFT, whereas genetic ablation exerts anxiogenic effects (Li et al., 2016). In contrast, these oxytocin receptor-expressing SST+ INs modulate socio-sexual behaviors (Nakajima et al., 2014) and prosocial activity (Li et al., 2016) in female mice.

VI. Conclusions, potential mechanisms, and future directions

On the whole, evidence supports a strong role for theta frequency communication and distinct mPFC circuits and cell types in driving anxiety-related avoidance behaviors. However, many outstanding questions remain (see Box 1). Neurons in the mPFC differentiate between the open and closed arms of the EPM; this suggests that the mPFC is capable of encoding safe and aversive features within anxiety-provoking environments, although the identity of these neurons remains unknown. These representations may be driven by vHPC theta rhythms that recruit VIP+ INs.

Box 1. Outstanding questions and future directions.

The studies summarized above provide compelling evidence that a variety of distinct long-range afferent input (vHPC, BLA, MD) to the mPFC can modulate the expression of anxiety-related phenotypes in rodents. What is less clear, however, is the mechanisms by which the mPFC parses out multiple sources incoming information and divides that information among distinct output populations to drive or inhibit anxiety-related behaviors. In contrast to afferent input, the investigation into different mPFC output populations in the regulation of anxiety-related behaviors is understudied and warrants future investigation.

While it is known the mPFC encodes anxiety-related contextual information, it remains to be determined if this information is represented in projection-defined mPFC neurons or transmitted to downstream structures.

What microcircuits in the mPFC and the interconnected brain regions contribute to the alteration of network oscillations, particulary in the theta frequency range, during approach-avoidance conflict?

Via what mPFC cell types and circuits do neuromodulators exert effects on regulate anxiety?

It is unclear whether and how the results summarized in this manuscript relate to females. Almost all the studies summarized herein have been conducted in male mice exclusively. Females display two times higher prevalence rates than males. Therefore, understanding how mPFC neural mechanisms contribute to anxiety-related avoidance behaviors in females is of the utmost importance.

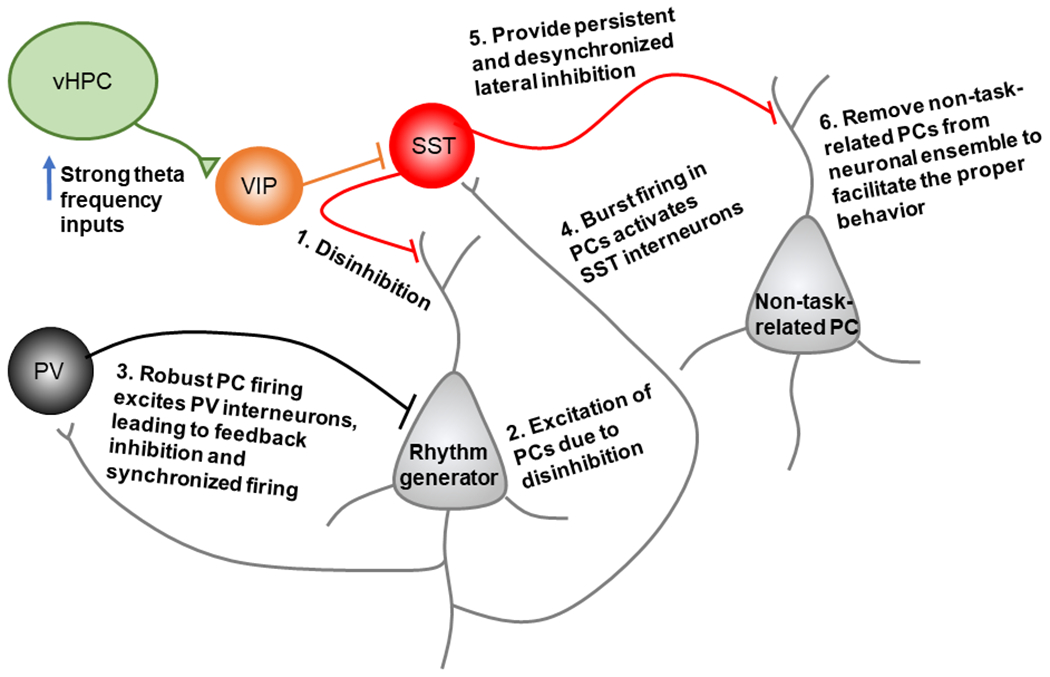

Theta power within the mPFC is positively correlated with anxiety-like behaviors, and theta frequency communication in the vHPC-mPFC circuit can drive avoidance of innate anxiety-provoking environments. Theta rhythm is critically modulated by PV+ or SST+ INs in the hippocampus (Amilhon et al., 2015; Park et al., 2020). Interneurons in mPFC are also key modulators in internal cortical theta rhythms. When vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony is high, VIP+ INs are recruited and then inhibit SST+ INs to disinhibit nearby PCs (Zhang et al., 2014). We hypothesize that synchronized firing of PCs should excite PV+ INs robustly; in return, PCs may receive feedback inhibition from PV+ INs to act as a rhythm generator in theta frequencies (Figure 6). Indeed, evidence suggests phasic inhibition of PV+ INs in the mPFC drives local theta phase-resetting, which is important for expressing conditioned fear behavior (Courtin et al., 2014). It is plausible that SST+ INs could also be reactivated by the rhythm generator, but only in the absence of vHPC inputs. Because of the PC activity-dependent properties of SST+ INs, they are likely more sensitive to bursting PCs, and then provide lateral inhibition to the distal dendrites of those PCs not task-related (Zhang et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2016), resulting in a high signal-to-noise ratio to facilitate the proper behavior. The persistent and desynchronized inhibition from SST+ INs (Deng et al., 2020) would guarantee to silence those non-task-related PCs, preventing a sudden withdraw of inhibition that may cause rebound activity and PC synchronization (Hilscher et al., 2017). This is different from those task-related PCs that discharge simultaneously when a sudden withdraw of inhibition from PV+ INs. Thus, PV+ INs play an essential role in mPFC theta generation via powerful and precise feedback inhibition. However, SST+ INs may control the ensemble size of PCs (Stefanelli et al., 2016) via long-lasting and imprecise inhibition. Altered SST+ function in the mPFC 5-HT1AR KO mice could explain why the magnitude of mPFC theta is larger in these animals, although this hypothesis has yet to be tested directly. Perhaps mice with avoidant behavior have reduced function of SST+ INs (Soumier and Sibille, 2014; Lin and Sibille, 2015; Fee et al., 2017), leading to increased recruitment of PCs to the network and consequent higher theta rhythm power.

Figure 6.

Hypothetical model supported by the recent literature, where strong theta frequency inputs from ventral hippocampal (vHPC) recruits VIP interneurons in the rodent medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). The activation of VIP interneurons creates a disinhibitory effect within the mPFC microcircuit, leading to pyramidal cell (PC) activation. Synchronous PC firing leads to robust PV interneuron activation, and in return, PCs may receive feedback inhibition from PV+ interneurons to act as a rhythm generator in theta frequencies. The internal theta rhythm generator may reactivate SST+ interneurons, resulting in persistent and desynchronized lateral inhibition to non-task-related PCs.

Altogether, current evidence points to extensive diversity and complexity in how unique glutamatergic afferents engage the mPFC microcircuit and in turn regulate anxiety. Through the use of optogenetic and chemogenetic tools, recent research has revealed that inputs from the vHPC, BLA, and MD are capable of driving anxiety-related avoidance behavior via distinct mechanisms in the mPFC. However, more work is needed to understand how unique afferent inputs engage distinct populations of mPFC INs, and how these INs in turn, regulate activity in mPFC output populations to guide approach-avoidance behavior. Addressing these questions will require a systematic comparison of multiple glutamatergic or neuromdulatory inputs and their resulting effects on IN activity during approach-avoidance conflict behavior. The importance of combining tools for both manipulation and monitoring of distinct neural circuits, cell types, and brain regions is exemplified by recent findings. For example, Lee and colleagues show that optical inhibition of VIP+ INs only reduces avoidance behavior when the light is delivered in specific zones of the EPM where VIP+ activity is highest (Lee et al., 2019). Moreover, the behavioral effects of inhibiting VIP+ INs depend on the strength of vHPC-mPFC theta synchrony, which indicates that VIP+ INs do not simply excite or inhibit cells that drive open-arm avoidance. This may be true for other GABAergic IN populations, as distinct behavioral effects have been seen with chronic versus acute inhibition of SST+ and PV+ INs. The pattern and duration of stimulation used in future experiments may also be necessary, as delivering light in an oscillatory pattern rather than a pulsatile pattern exerted distinct effects on both anxiety-related avoidance behavior and neural communication in the vHPC-mPFC circuit (Padilla-Coreano et al., 2019). Finally, while there is conclusive evidence that VIP+, PV+, and SST+ IN populations all play unique roles in regulating mPFC neural activity to control avoidance behavior, there are undoubtedly other molecularly-defined IN subtypes that have yet to be explored. For example, in light of recent evidence that vHPC afferents engage cholecystokinin (CCK+) INs in the IL cortex (Liu et al., 2020), future studies may be interested in determining whether these cells play a relevant role in avoidance behavior.

Thus, while caveats exist, more work is required to define the exact micro and macro-circuit mechanisms, the delicate balance of excitation and inhibition in the mPFC, as mediated by intra-connectivity via diverse IN populations and long-range connections with other prominent nuclei in the limbic system, appears to play an integral role in regulating anxiety-related avoidance behaviors. Several studies outlined in this paper have highlighted the neural circuit and cell-type-specific ways in which the mPFC regulates behavior during approach-avoidance conflict (Figure 4). Yet, more work is needed for a comprehensive understanding of the differing mPFC neural circuits that contribute to avoidance behavior, especially given the extensive connectivity between the mPFC and other brain regions involved in emotional and autonomic control. Also, considering the critical role of the mPFC in both emotion and cognition, understanding these mechanisms will shed light on the effects of anxiety on cognitive behaviors such as decision-making and cognitive flexibility (Park and Moghaddam, 2017). Revealing the integration of different afferent pathways, particularly as mediated by interactions between excitatory and inhibitory neurons, and how they converge onto distinct efferent pathways, represents an exciting opportunity for the future understanding of anxiety.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01MH085666, R21MH121836, and Pennsylvania Commonwealth SAP# 4100085747 (CURE 2020) to W. J. Gao, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31630029 and 32000680), and Shanghai Municipal of Science and Technology Project (Grant 20JC1419500).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abbas AI, Sundiang MJM, Henoch B, Morton MP, Bolkan SS, Park AJ, Harris AZ, Kellendonk C, Gordon JA (2018) Somatostatin Interneurons Facilitate Hippocampal-Prefrontal Synchrony and Prefrontal Spatial Encoding. Neuron 100:926–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A, Topiwala MA, Gordon JA (2010) Synchronized activity between the ventral hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex during anxiety. Neuron 65:257–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A, Topiwala MA, Gordon JA (2011) Single units in the medial prefrontal cortex with anxiety-related firing patterns are preferentially influenced by ventral hippocampal activity. Neuron 71:898–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A, Lerner TN, Finkelstein J, Pak S, Jennings JH, Davidson TJ, Ferenczi E, Gunaydin LA, Mirzabekov JJ, Ye L, Kim SY, Lei A, Deisseroth K (2015) Basomedial amygdala mediates top-down control of anxiety and fear. Nature 527:179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert PR, Vahid-Ansari F, Luckhart C (2014) Serotonin-prefrontal cortical circuitry in anxiety and depression phenotypes: pivotal role of pre- and post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptor expression. Front Behav Neurosci 8:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Geiger JRP (2006) Combined Analog and Action Potential Coding in Hippocampal Mossy Fibers. Science 311:1290–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amilhon B, Huh CY, Manseau F, Ducharme G, Nichol H, Adamantidis A, Williams S (2015) Parvalbumin Interneurons of Hippocampus Tune Population Activity at Theta Frequency. Neuron 86:1277–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelow B, Michaelis S (2015) Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience 17:327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barson JR, Mack NR, Gao WJ (2020) The Paraventricular Nucleus of the Thalamus Is an Important Node in the Emotional Processing Network. Front Behav Neurosci 14:598469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzung C, Griebel G (2001) Measuring normal and pathological anxiety-like behaviour in mice: a review. Behavioural brain research 125:141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicks LK, Yamamuro K, Flanigan ME, Kim JM, Kato D, Lucas EK, Koike H, Peng MS, Brady DM, Chandrasekaran S, Norman KJ, Smith MR, Clem RL, Russo SJ, Akbarian S, Morishita H (2020) Prefrontal parvalbumin interneurons require juvenile social experience to establish adult social behavior. Nat Commun 11:1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonette GB, Powell EM, Roesch MR (2013) Neural structures underlying set-shifting: roles of medial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. Behavioural brain research 250:91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KG, Barker JM (2020) Arbitration of Approach-Avoidance Conflict by Ventral Hippocampus. Frontiers in neuroscience 14:615337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoon GG, Tye KM (2015) Resolving the neural circuits of anxiety. Nat Neurosci 18:1394–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness VS, Jr. (1975) Architectonic map of neocortex of the normal mouse. The Journal of comparative neurology 164:247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Wu JL, Hu NY, Zhuang JP, Li WP, Zhang SR, Li XW, Yang JM, Gao TM (2021) Distinct projections from the infralimbic cortex exert opposing effects in modulating anxiety and fear. The Journal of clinical investigation 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheriyan J, Kaushik MK, Ferreira AN, Sheets PL (2016) Specific Targeting of the Basolateral Amygdala to Projectionally Defined Pyramidal Neurons in Prelimbic and Infralimbic Cortex. eNeuro 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciocchi S, Passecker J, Malagon-Vina H, Mikus N, Klausberger T (2015) Brain computation. Selective information routing by ventral hippocampal CA1 projection neurons. Science (New York, NY) 348:560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Quirk GJ (2007) Activity in prelimbic cortex is necessary for the expression of learned, but not innate, fears. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 27:840–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtin J, Chaudun F, Rozeske RR, Karalis N, Gonzalez-Campo C, Wurtz H, Abdi A, Baufreton J, Bienvenu TC, Herry C (2014) Prefrontal parvalbumin interneurons shape neuronal activity to drive fear expression. Nature 505:92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Holmes A (2005) The ascent of mouse: advances in modelling human depression and anxiety. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4:775–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunniff MM, Markenscoff-Papadimitriou E, Ostrowski J, Rubenstein JL, Sohal VS (2020) Altered hippocampal-prefrontal communication during anxiety-related avoidance in mice deficient for the autism-associated gene Pogz. eLife 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Farinas I (1992) The pyramidal neuron of the cerebral cortex: morphological and chemical characteristics of the synaptic inputs. Progress in neurobiology 39:563–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Li J, He Q, Zhang X, Zhu J, Li L, Mi Z, Yang X, Jiang M, Dong Q, Mao Y, Shu Y (2020) Regulation of Recurrent Inhibition by Asynchronous Glutamate Release in Neocortex. Neuron 105:522–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, Martin KA (2004) Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annual review of neuroscience 27:419–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval ER, Javanbakht A, Liberzon I (2015) Neural circuits in anxiety and stress disorders: a focused review. Therapeutics and clinical risk management 11:115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fee C, Banasr M, Sibille E (2017) Somatostatin-positive gamma-aminobutyric acid Interneuron deficits in depression: cortical microcircuit and therapeutic perspectives. Biological psychiatry 82:549–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz AC, Burgos-Robles A, Bhagat ND, Leppla CA, Tye KM (2016) Bidirectional modulation of anxiety-related and social behaviors by amygdala projections to the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 321:197–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BR, Gao WJ (2018) Thalamic Control of Cognition and Social Behavior Via Regulation of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acidergic Signaling and Excitation/Inhibition Balance in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Biol Psychiatry 83:657–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick CJ, Knox D, Liberzon I (2011) Inactivation of the prelimbic cortex enhances freezing induced by trimethylthiazoline, a component of fox feces. Behavioural brain research 221:320–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PL, Dickie BG, Vaid RR, Headlam AJ, Bacon SJ (1997) Local-circuit neurones in the medial prefrontal cortex (areas 25, 32 and 24b) in the rat: morphology and quantitative distribution. The Journal of comparative neurology 377:465–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PL, Warner TA, Jays PR, Salway P, Busby SJ (2005) Prefrontal cortex in the rat: projections to subcortical autonomic, motor, and limbic centers. The Journal of comparative neurology 492:145–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W-J, Yang S-S, Mack NR, Chamberlin LA (2021) Aberrant maturation and connectivity of prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia—contribution of NMDA receptor development and hypofunction. Molecular psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee S, Ellwood I, Patel T, Luongo F, Deisseroth K, Sohal VS (2012) Synaptic activity unmasks dopamine D2 receptor modulation of a specific class of layer V pyramidal neurons in prefrontal cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 32:4959–4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustino TF, Maren S (2015) The Role of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex in the Conditioning and Extinction of Fear. Front Behav Neurosci 9:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goes TC, Almeida Souza TH, Marchioro M, Teixeira-Silva F (2018) Excitotoxic lesion of the medial prefrontal cortex in Wistar rats: Effects on trait and state anxiety. Brain research bulletin 142:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare BD, Shinohara R, Liu RJ, Pothula S, DiLeone RJ, Duman RS (2019) Optogenetic stimulation of medial prefrontal cortex Drd1 neurons produces rapid and long-lasting antidepressant effects. Nat Commun 10:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilscher MM, Leão RN, Edwards SJ, Leão KE, Kullander K (2017) Chrna2-Martinotti Cells Synchronize Layer 5 Type A Pyramidal Cells via Rebound Excitation. PLoS biology 15:e2001392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G, Lieber CM (2019) Novel electrode technologies for neural recordings. Nat Rev Neurosci 20:330–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover WB, Vertes RP (2007) Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain structure & function 212:149–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Scanziani M (2011) How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron 72:231–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto LR, Cerqueira JJ, Sousa N (2016) Patterns of Theta Activity in Limbic Anxiety Circuit Preceding Exploratory Behavior in Approach-Avoidance Conflict. Front Behav Neurosci 10:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks AL, McGregor IS (1997) Modulation of anxiety-related behaviours following lesions of the prelimbic or infralimbic cortex in the rat. Brain Res 772:181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapfer C, Glickfeld LL, Atallah BV, Scanziani M (2007) Supralinear increase of recurrent inhibition during sparse activity in the somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci 10:743–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerby C, Athilingam J, Robinson SE, Iafrati J, Sohal VS (2016) Serotonin 1B Receptors Regulate Prefrontal Function by Gating Callosal and Hippocampal Inputs. Cell Rep 17:2882–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B (2007) Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of internal medicine 146:317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Bhat ZA, Kumar D (2013) Animal models of anxiety: a comprehensive review. Journal of pharmacological and toxicological methods 68:175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix L, Spinelli S, Heidbreder CA, Feldon J (2000) Differential role of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices in fear and anxiety. Behavioral neuroscience 114:1119–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubach M, Amarante LM, Swanson K, White SR (2018) What, If Anything, Is Rodent Prefrontal Cortex? eNeuro 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AT, Vogt D, Rubenstein JL, Sohal VS (2014) A class of GABAergic neurons in the prefrontal cortex sends long-range projections to the nucleus accumbens and elicits acute avoidance behavior. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 34:11519–11525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AT, Cunniff MM, See JZ, Wilke SA, Luongo FJ, Ellwood IT, Ponnavolu S, Sohal VS (2019) VIP Interneurons Contribute to Avoidance Behavior by Regulating Information Flow across Hippocampal-Prefrontal Networks. Neuron 102:1223–1234.e1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Hjerling-Leffler J, Zagha E, Fishell G, Rudy B (2010) The largest group of superficial neocortical GABAergic interneurons expresses ionotropic serotonin receptors. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30:16796–16808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Nakajima M, Ibanez-Tallon I, Heintz N (2016) A Cortical Circuit for Sexually Dimorphic Oxytocin-Dependent Anxiety Behaviors. Cell 167:60–72.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtik E, Stujenske JM, Topiwala MA, Harris AZ, Gordon JA (2014) Prefrontal entrainment of amygdala activity signals safety in learned fear and innate anxiety. Nat Neurosci 17:106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LC, Sibille E (2015) Somatostatin, neuronal vulnerability and behavioral emotionality. Molecular psychiatry 20:377–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa SF, Stecchini MF, Correa FM, Guimaraes FS, Resstel LB (2010) Different role of the ventral medial prefrontal cortex on modulation of innate and associative learned fear. Neuroscience 171:760–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister RG (1990) Ethologically-based animal models of anxiety disorders. Pharmacology & therapeutics 46:321–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JP, Carter AG (2013) Synaptic mechanisms underlying strong reciprocal connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 33:15333–15342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Carter AG (2018) Ventral Hippocampal Inputs Preferentially Drive Corticocortical Neurons in the Infralimbic Prefrontal Cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 38:7351–7363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Dimidschstein J, Fishell G, Carter AG (2020) Hippocampal inputs engage CCK+ interneurons to mediate endocannabinoid-modulated feed-forward inhibition in the prefrontal cortex. eLife 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewke AC, Minerva AR, Nelson AB, Kreitzer AC, Gunaydin LA (2021) Frontostriatal Projections Regulate Innate Avoidance Behavior. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 41:5487–5501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Tucciarone J, Lin Y, Huang ZJ (2014) Input-specific maturation of synaptic dynamics of parvalbumin interneurons in primary visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111:16895–16900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaswinkel H, Gispen WH, Spruijt BM (1996) Effects of an electrolytic lesion of the prelimbic area on anxiety-related and cognitive tasks in the rat. Behavioural brain research 79:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek R, Jin J, Goode TD, Giustino TF, Wang Q, Acca GM, Holehonnur R, Ploski JE, Fitzgerald PJ, Lynagh T, Lynch JW, Maren S, Sah P (2018) Hippocampus-driven feed-forward inhibition of the prefrontal cortex mediates relapse of extinguished fear. Nat Neurosci 21:384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry LM, Carter AG (2016) Inhibitory Gating of Basolateral Amygdala Inputs to the Prefrontal Cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 36:9391–9406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka A, Adesnik H (2016) Inhibitory Circuits in Cortical Layer 5. Front Neural Circuits 10:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Görlich A, Heintz N (2014) Oxytocin Modulates Female Sociosexual Behavior through a Specific Class of Prefrontal Cortical Interneurons. Cell 159:295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Coreano N, Bolkan SS, Pierce GM, Blackman DR, Hardin WD, Garcia-Garcia AL, Spellman TJ, Gordon JA (2016) Direct Ventral Hippocampal-Prefrontal Input Is Required for Anxiety-Related Neural Activity and Behavior. Neuron 89:857–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Coreano N, Canetta S, Mikofsky RM, Alway E, Passecker J, Myroshnychenko MV, Garcia-Garcia AL, Warren R, Teboul E, Blackman DR, Morton MP, Hupalo S, Tye KM, Kellendonk C, Kupferschmidt DA, Gordon JA (2019) Hippocampal-Prefrontal Theta Transmission Regulates Avoidance Behavior. Neuron 104:601–610.e604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page CE, Shepard R, Heslin K, Coutellier L (2019) Prefrontal parvalbumin cells are sensitive to stress and mediate anxiety-related behaviors in female mice. Scientific reports 9:19772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt GM, Nguyen R, Bang JY, Aqrabawi AJ, Tran MM, Seo DK, Richards BA, Kim JC (2017) Bidirectional Control of Anxiety-Related Behaviors in Mice: Role of Inputs Arising from the Ventral Hippocampus to the Lateral Septum and Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 42:1715–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Moghaddam B (2017) Impact of anxiety on prefrontal cortex encoding of cognitive flexibility. Neuroscience 345:193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K, Lee J, Jang HJ, Richards BA, Kohl MM, Kwag J (2020) Optogenetic activation of parvalbumin and somatostatin interneurons selectively restores theta-nested gamma oscillations and oscillation-induced spike timing-dependent long-term potentiation impaired by amyloid β oligomers. BMC biology 18:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F, Scanziani M (2004) Routing of spike series by dynamic circuits in the hippocampus. Nature 429:717–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig MV, Gulledge AT (2011) Serotonin and prefrontal cortex function: neurons, networks, and circuits. Molecular neurobiology 44:449–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof KR, Ullsperger M, Crone EA, Nieuwenhuis S (2004) The role of the medial frontal cortex in cognitive control. Science (New York, NY) 306:443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B, Lin H, Milyavskaya M, Inzlicht M (2017) The emotive nature of conflict monitoring in the medial prefrontal cortex. International journal of psychophysiology : official journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology 119:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AA, Treit D (2003) Excitotoxic lesions of the medial prefrontal cortex attenuate fear responses in the elevated-plus maze, social interaction and shock probe burying tests. Brain Res 969:183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AA, Sjovold T, Treit D (2004) Inactivation of the medial prefrontal cortex with the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol increases open-arm activity in the elevated plus-maze and attenuates shock-probe burying in rats. Brain Res 1028:112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Hasenstaub A, McCormick DA (2003) Turning on and off recurrent balanced cortical activity. Nature 423:288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Yu Y, Yang J, McCormick DA (2007) Selective control of cortical axonal spikes by a slowly inactivating K+ current. PNAS 104:11453–11458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, Hasenstaub A, Duque A, Yu Y, McCormick DA (2006) Modulation of intracortical synaptic potentials by presynaptic somatic membrane potential. Nature 441:761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Mercado D, Padilla-Coreano N, Quirk GJ (2011) Dissociable roles of prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, ventral hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala in the expression and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 36:529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg G (2008) Polysynaptic subcircuits in the neocortex: spatial and temporal diversity. Current opinion in neurobiology 18:332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumier A, Sibille E (2014) Opposing effects of acute versus chronic blockade of frontal cortex somatostatin-positive inhibitory neurons on behavioral emotionality in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 39:2252–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanelli T, Bertollini C, Lüscher C, Muller D, Mendez P (2016) Hippocampal Somatostatin Interneurons Control the Size of Neuronal Memory Ensembles. Neuron 89:1074–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan RM, Gratton A (2002) Behavioral effects of excitotoxic lesions of ventral medial prefrontal cortex in the rat are hemisphere-dependent. Brain Res 927:69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]