Abstract

Viral diseases are causing mayhem throughout the world. One of the zoonotic viruses that have emerged as a potent threat to community health in the past few decades is Nipah virus. Nipah viral sickness is a zoonotic disease whose main carrier is bat. This disease is caused by Nipah virus (NiV). It belongs to the henipavirous group and of the family paramyxoviridae. Predominantly Pteropus spp. is the carrier of this virus. It was first reported from the Kampung Sungai Nipah town of Malaysia in 1998. Human-to-human transmission can also occur. Several repeated outbreaks were reported from South and Southeast Asia in the recent past. In humans, the disease is responsible for rapid development of acute illness, which can result in severe respiratory illness and serious encephalitis. Therefore, this calls for an urgent need for health authorities to conduct clinical trials to establish possible treatment regimens to prevent any further outbreaks.

Keywords: Nipah virus (NiV), Zoonotic, Encephalitis, Epidemiology, Pathology, Septicemia, Seroprevalence

Introduction

Viral diseases are responsible for high amount of mortality and morbidity among different communities throughout the world. Many of these viruses are zoonotic in nature and infect animals first and from them transmitted to humans. Nipah virus (NiV) is a bat-borne pathogen (zoonotic virus), which causes lethal encephalitis in humans and can be transmitted through infected food or directly to humans [1]. The virus causes a variety of diseases ranging from subclinical infections to severe respiratory infections and fatal encephalitis. The virus can also cause serious diseases in animals leading to significant economic losses for farmers [2]. It is one of the many deadly viruses and comes within the order of Mononegavirales; other fatal viruses of this order are Hendra, Ebola, and Marburg [3]. Pteropus fruit bats are considered natural sources of the virus. The first outbreak of Nipah was reported in the year 1999 in Malaysia. This virus was first isolated from a patient from the southwestern Sungai Nipah region of Malaysia. Hence, it is named as Nipah virus (NiV). NiV was discovered in 1998, the first reported outbreak within Sungai Nipah [4].

In India, the first outbreak occurred in Siliguri, West Bengal in 2001 and in 2007, a recurring outbreak was reported from Nadia in West Bengal, India. More recently, in 2018, a new outbreak was recorded in the Kozhikode district in Kerala, a state in southern India where the person affected was said to have contracted NiV from fruit bats [5]. All the outbreaks recorded high mortality rates including 91% of deaths over time in the recent Kerala outbreak. In humans, infection quickly advances to extreme sickness, which causes serious respiratory ailments as well as serious encephalitis [6]. Absence of antibodies or therapeutics to counter this sickness is a major cause why scientists worldwide are trying to develop a powerful NiV immunization and therapy policy. This particular review reports the pathogenesis of Nipah virus and includes studies on the interaction between host and pathogen, host resistance, if any, and its risk factors [7].

Structure

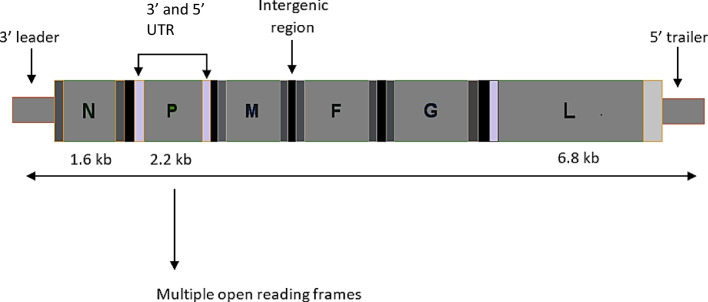

There are various species of Henipavirus. One of them is Henipavirions. It does not have any particular shape; it is pleomorphic to some extent. Its length ranges from 40 to 600 nm in diameter [8]. Enveloped RNA virus possesses a helical symmetry; it is non-segmented and single-stranded. The RNA genome primarily contains six basic genes, and these are nucleocapsid, phosphoprotein, matrix, fusion glycoprotein, attachment glycoprotein, and long polymerase as mentioned in Fig. 1. They have their viral matrix protein shell overlayed by a lipid membrane. The genomic RNA of the core is tightly attached to the nucleocapsid and phosphoprotein proteins. There is a spike made up of F (fusion) protein trimers and G (attachment) protein, which is tetramer in nature and embedded within the lipid membrane [9]. The G protein helps to attach the virus to the surface of host cells via interaction with the conserved mammalian protein family, ephrin b1, b2, or b3 [10]. The fusion protein helps to fuse the membranes of the host cell and the virus, which liberates the virions into the host cell. It also induces swollen cells to fuse with adjacent cells to form massive syncytia.

Fig. 1.

Structure of Nipah virus (picture reference: adapted from Pillai et al. 2020 under Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license [4]

Etiopathogenesis

NiV or Nipah virus is an infectious disease, which is transmitted initially from animal to human and human to human. This kind of disease can spread through pigs and bats. If humans consume fruits that are already contaminated by any infected pig or bat, then the disease can spread to humans [11]. During summer, several fruits, most notably litchis and mangoes, are consumed by people, particularly children. Bats may bite fruits on trees at night, and these fruits are sold in the market the next morning, making it difficult to determine if the fruits in the trees were eaten by bats or not [12]. The virus can also spread to the human body through the urine and saliva of these creatures. Hence, fruits or saps contaminated with the urine and saliva of an infected animal can also be a potent source of transmission of infection. Bats also may leave their saliva or secretions on trees and hence can infect people while climbing the trees.

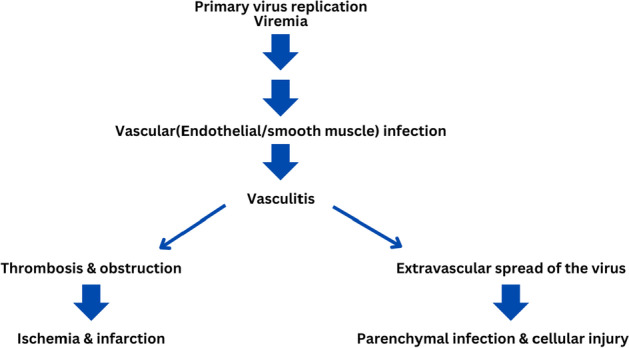

By identifying the antigen, isolating the virus, and using serology, this infection may be tested. Histopathology can be used to carry out detection. To find the Nipah virus in pigs, various tissues, blood, and respiratory secretions have been employed. Additionally, feline blood, urine, and respiratory secretions can all be tested for the virus. Nevertheless, the virus is found in dogs’ brain, spleen, liver, lung, kidney, adrenal gland, and other organs. The disease-causing pathway is explained in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Nipah virus disease-causing pathway

Nipah virus can spread by human respiratory secretions, and it is one of the major sources of human-to-human transmission [13]. Affected individuals can spread it through coughing, sneezing, urine, saliva etc. Cellular interactions are controlled by the fusion (F) and attachment (G) proteins. Two subunits, viz., F1 and F2, by host protease are cleaved by the newly produced precursor (F) protein (F0). The merging peptide of the virus is present within the F1 subunit and helps in virus and host cell binding [14]. The viral M protein is involved in morphogenesis and budding. Antibodies to G proteins are important for neutralizing NiV infectivity [15].

Due to the coordinated efforts of glycoprotein fusion and attachment, it is very natural for the enveloped Henipavirus, which contains NiV, to invade target cells after binding. Interactions between class B ephrin (viral receptor) and NiV glycoprotein (G) in host cells cause conformational changes within the latter, resulting in activation and membrane fusion of F glycoprotein [16]. The Nipah G protein binds to the host ephrin B2/3 receptor and amplifies the conformational change of the G protein that causes F protein refolding [17]. It has been demonstrated that monomeric ephrin B2 fusion causes allosteric changes in Nipah G protein, which paves the way to receptor-activated virus entry into host cells. Presently, viral regulation of host cell machinery has been in the center of focus to understand the nucleolar DNA-damage reply pathway.

Pathogenesis of Nipah Virus

During the commencing stage of infection, diagnosis of NiV can be executed in epithelial cells, especially in the bronchiole [18]. Viral antigens have been observed in lungs, specifically in the bronchi and in some cases even in alveoli. Cytokines are secreted due to the swollen epithelium of the respiratory tract because of the infection, thereby ultimately leading to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)-like disorder [19]. Inflammatory mediators such as interleukin granulocyte-colony stimulating issue are also secreted in the airway epithelium during the later stage of infection [20]. From the breathing epithelium, the virus is promulgated to the cells of the endothelium. With progression of infection, the virus can gain access into the bloodstream. Apart from the respiratory, digestive, and execratory systems the brain and other organs can also be a target, which leads to multi-organ failure. In hamster animal models, it is also reported that leukocytes can also be infected with NiV that leads to lethal consequences [13]. Viral genome arrangements are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Arrangement of Nipah viral genome

The virus enters in the central nervous system (CNS) through the blood vessels of the cerebrum known as the choroid plexus. The blood–brain barrier (BBB) can be disrupted due to this infection and ultimately leads to several neurological problems.

In humans, infected CNS may contain nonliving viral particles, which can lead to necrosis. Several recent studies on animal models reported the possibility of the virus immediately entering the central nervous system via the olfactory nerve [11]. The infection can eventually spread through the olfactory bulb. Ultimately, the virus spreads through the whole ventral cortex at the side of the olfactory tubercle [11]. There is some structural information on the proteins and interactions of the viral proteins are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structural information on proteins and interactions with viral proteins

Clinical Manifestations and Symptoms

The primary repository host of the infection is bats of the family Pteropus. In some cases, the intermediate host (pig) can transmit the disease to humans. In comparison to humans, respiratory distress is more severe in the case of pigs. The virus is responsible for bringing about the severity in the respiratory system as well as the nervous system [22]. After exposure to the virus, it takes about 4–14 days for symptoms to appear; hence, the incubation period is about 4–14 days [23].

Symptoms in Humans

Initial symptoms in humans include fever, vomiting, headache, cough, sore throat, and muscle aches. Septicemia may also turn up accompanied by renal system impairment and can also cause bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract [24]. Also, some patients may experience difficulty in breathing, which ranges from atypical pneumonia to acute respiratory perturbation. These are followed by certain severe symptoms like disorientation, drowsiness, mental confusion, seizures, and some neurological signs that indicate encephalitis (brain swelling). The disease may result in coma and death within a few days [25]. It has been statistically found out that the mortality rate of this viral disease is about 40–75%. In the case of Nipah virus survivors, it has been witnessed that some long-term side effects persisted in them like convulsions and certain changes in personality and certain other neurological disorders [26].

Symptoms in Animals

In pigs, this sickness is also named as porcine respiratory and encephalitis syndrome (PRES). Also, it is famous as barking pig syndrome (BPS) (in peninsular Malaysia) or one-mile hack. An acute feverish illness is reported to develop especially in pigs below 6 years of age. Respiratory sickness is accompanied with rapid labored breathing. In the case of animals that are specially confined or allowed restricted movement, the morbidity rate may approach up to 100 percent [10]. Since this involves impairment of the nervous system; hence, muscle twitch, hind leg weakness, tremors, and flaccid or spastic paresis are experienced [27]. In boars or common wild male pigs and in adult females that are sows, a condition has been reported called nystagmus where the eyes make uncontrolled movements, which result in reduced vision and affect balance and coordination. Also, this is responsible for seizures in pigs [6]. In NiV-affected dogs, inflammation of the lungs is experienced. Also, there are other conditions such as necrosis of glomeruli and tubules accompanied by syncytia formation in the kidneys [8].

Infected cats are found to develop endothelial syncytia and vascular abnormalities in their multiple organs. In several other species, for example, guinea pig, hamster, and African green monkey, when they are experimentally infected with NiV, some primary clinical signs are observed. The signs include lesions in the parenchyma in the central nervous system along with severe vascular abnormalities in several multiple organs and weight loss [9].

Diagnosis

Isolation of the virus, as well as serological testing and assays for viral nucleic acid amplification, is required to confirm the presence of infections in humans and animals. These serological tests are essentially antibody tests that look for antibodies in the blood and give a positive result if infection is present. For NiV confinements and their proliferation, biosafety level-4 (BSL-4) facilities are required. A monoclonal neutralizer-based antigen ELISA has been created for detecting NiV[9]. IgG ELISAs have been utilized for testing pig and human sera, and an IgM mediated ELISA using a recombinant N protein of NiV has been extremely helpful in identifying the viral contamination [20]. Sandwich ELISA using a polyclonal neutralizer to NiV G protein has been created and proved to be a rapid test for diagnosing the disease. By the usage of pseudo-typed particles, a serum balance test for NiV can be performed under BSL-2 conditions. Microsphere measure has been used for the area of antibodies against a glycoprotein (NiVsG) in the sera of pigs and ruminants like goats and steers [21]. ELISA using recombinant full-length N and G protein has been created [22]

Molecular Epidemiology

It has been perceived by nucleotide sequencing that there is no huge distinction in the nucleotide sequences of NiV isolated from throat discharge and cerebrospinal fluid [22]. Nucleotide homology has been done between the sequences from Bangladesh and Malaysia.

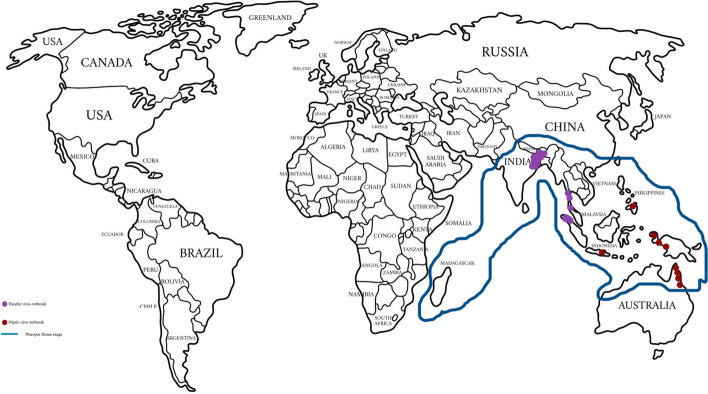

Phylogenetic assessments have been performed on NiV strains from the years 2008 to 2010 in Bangladesh. In view of a nucleotide course of action window, a genotyping plan has been introduced. For sequence classification of NiV, phylogenetic tree analysis is very useful [10]. Phylogenetic investigation showed the close homology of arrangements in sequences from pigs and people during the Malaysian flare-up [23]. Henipavirus outbreak and Pteropus distribution are shown in Fig. 4. Phylogenetic tree showing close homology between Indian and Malaysian strains is mentioned in Fig. 5

Fig. 4.

Henipavirus outbreak and Pteropus distribution map

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree showing close homology between Indian and Malaysian strains

Current Research

Niv enters its target cells via surface glycoproteins, i.e., proteins G and F. G glycoprotein binds attachment to extracellular receptors and the fused protein (f) induces viral cell membranes to invade the cell. Mutations in the NiVG protein that open the way to its full function and access to the receptor-activated virus in host cells. Recently, viral control of mobile devices has been revealed in the target of the nucleolar DNA-damage reaction (DDR) method with the help of inhibiting nucleolar treacle protein that will increase the production of henipavirus (Hendra and Nipah viruses) [19]. Nipah virus can remain viable for a few days in few fruit juices or mango fruits, and at least 7 days in palm milk. Bats act as a breeding ground for many dangerous viruses, including Nipah, rabies, and Marburg viruses. Such viruses are not associated with any major pathological changes within the bat population [24]. Detailed research is needed to identify the ways of transmission of NiV from bats to pigs, pigs to human, and from palm milk to human source. Transmission of NiV occurs by eating contaminated food. Risks include contact, touch, breastfeeding, or exposure to an infected person, thereby making it easier to come in contact with a droplet of NiV infection. More recently, experimental studies with aerosolized NiV in Syrian hamsters have found that NiV droplets (aerosol distribution) may cause NiV transmission during close contact [25]. Drinking fresh palm milk is a very common method, and the use of Tari (ripe palm juice) is a powerful way to transmit the virus. Tari-related Niv infections can be avoided by restricting access to bats to date palm milk [24]. Research using infrared cameras has shown that palm trees are often visited by bats such as Pteropus giganteus, and that from time to time bats lick them. The virus can persist for several days in a sugary solution, i.e., fruit pulp. High seroprevalence of anti-Nipah virus antibodies are reported in Petrous spp [25]. This suggests the fact that the virus has passed through adaptation in order to spread among Pteropusbats. Vaccination of people is an important part of preventing infection of NiV. Prevention also includes vaccination of farm animals such as pigs and horses in permanent habitats [10]. Outbreaks cannot be avoided among livestock in areas where palm milk contamination serves as a first step in the spread of NiV infection. However, if vaccination of cattle is done at a reasonable price, it may appear to be successful in these areas. Despite these trends, pharmaceutical agencies are reluctant to invest in vaccine development courses such as against NiV, which are rare, despite high mortality [26].

Future Prospects

Over the past few decades, Nipah viral pathogenesis alongside the transmission mechanism has been in the focus for extensive research. This knowledge can be greatly improved in the coming decades [27]. It is important to note in this regard that rational use of this understanding must be used to achieve Nipah vaccine in clinical trials on humans, as well as in reducing the risk factors to prevent infection [28]. Prevention of this zoonotic disease is of utmost importance. Scientists have created a global outbreak network and a response network especially in the aftermath of epidemics in Bangladesh and India and recognized the need for improved communication between veterinary and medical services about the disease [29]. By involving more than one industry and multi-sector strategies, some robust prevention strategies can be developed and implemented [29]. In addition, people should be aware of food hygiene in addition to public hygiene.

Conclusion

Despite several warnings in the past 2 decades, regular outbreaks of NiV have led to numerous mortalities and morbidities in both humans and animals. Additionally, due to its pandemic potential, prevention of this disease is of critical importance due to its capability of causing a significant physical and economic burden and high mortality. Therefore, this calls for an urgent need for health authorities to conduct clinical trials to establish possible treatment regimens to prevent any further outbreaks of NiV.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Harit, A.K., Ichhpujani, R.L., Gupta,S. Gill,K.S.,Lal,S. Ganguly, N.K. (2006) et al. Nipah/Hendra virus outbreak in Siliguri, West Bengal, India in 2001. Indian J Med Res. 123, 553–560 [PubMed]

- 2.Bowden TA, Aricescu AR, Gilbert RJ, Grimes JM, Jones EY, Stuart DI. Nat StructMol Biol. 2008;15:567. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broder CC. Henipavirus outbreaks to antivirals: The current status of potential therapeutics. Current Opinion Virology. 2012;2(2):176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SomanPillai V, Krishna G, ValiyaVeettil M. Nipah virus: Past outbreaks and future containment. Viruses. 2020;12(4):465. doi: 10.3390/v12040465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for disease control and prevention Outbreak of Hendra-likevirus-Malaysia and Singapore, 1998–1999 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 48 (1999), pp.265–269 [PubMed]

- 6.Centers for disease control and prevention Update outbreak of Nipah virus -Malaysia and Singapore. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1999;48(1999):335–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chua KB. Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia. J ClinVirol. 2003;26:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halpin K, Hyatt AD, Fogarty R, Middleton D, Bingham J, Epstein JH. Pteropid bats are confirmed as the reservoir hosts of henipaviruses: A comprehensive experimental study of virus transmission. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2011;85:946–951. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hossain MJ, et al. Clinical presentation of Nipah virus infection in Bangladesh. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46:977–984. doi: 10.1086/529147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD, Ali MM, Ksiazek TG, Kuzmin I. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence. Bangladesh Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:2082–2087. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein JH, Rahman S, Zambriski J, Halpin K, Meehan G, Jamaluddin AA, et al. Feral cats and risk for Nipah virus transmission Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1178–1179. doi: 10.3201/eid1207.050799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua KB, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, Harcourt BH, Tamin A, Lam SK, et al. Nipah virus: A recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus Science. 2000;288:1432–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.K.E.Lee,T.Umapathi,C.B.Tan,H.T.Tjia,T.S.Chua,H.M.Oh,etal. (1999) The neurological manifestations of Nipah virus encephalitis, a novel paramyxovirus AnnNeurol.46, 428–432 [PubMed]

- 14.Kerry RG, et al. Nano-based approach to combat emerging viral (NIPAH virus) infection Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology. Biology and Medicine. 2019;18:196–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Harcourt BH, Yu M, Tamin A, Rota PA, Bellini WJ, et al. Molecular biology of Hendra and Nipah viruses. Microbes and Infection. 2001;3:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andrea M, Weingartl H. Organ-and endotheliotropism of Nipah virus infections in vivo and in vitro. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2009;102(12):1014–1023. doi: 10.1160/TH09-05-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MohdNor MN, Gan CH, Ong BL. Nipah virus infection of pigs in peninsular Malaysia. Revue Scientifique et Technique. 2000;19:160–165. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.1.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochani RK, Batra S, Shaikh A, Asad A. Nipah virus-the rising epidemic: A review. Le Infezioni in Medicina. 2019;27(2):117–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parashar UD, et al. Case-control study of risk factors for human infection with a new zoonotic Paramyxovirus, Nipah virus, during a 1998–1999 outbreak of severe encephalitis in Malaysia. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2000;181:1755–1759. doi: 10.1086/315457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paton NI, et al. Outbreak of Nipah-virus infection among abattoir workers in Singapore. The Lancet. 1999;354:1253–1256. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Harcourt BH, Yu M, Tamin A, Rota PA, Bellini WJ. Molecular biology of Hendra and Nipah viruses Microbes Infect. 2001;3:279–287. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LubyS P, GurleyE S, Hossain MJ. Transmission of human infection with Nipah virus Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1743–1748. doi: 10.1086/647951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luby SP, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Blum LS, Husain MM, Gurley E, Khan R, Ahmed BN, Rahman S, Nahar N, Kenah E, Comer JA, Ksiazek TG. Food borne transmission of Nipah virus. Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1888–1894. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh RK, Dhama K, Chakraborty S, Tiwari R, Natesan S, Khandia R, Munjal A, Vora KS, Latheef SK, Karthik K, Singh Malik Y, Singh R, Chaicumpa W, Mourya DT. Nipah virus: Epidemiology, pathology, immunobiology and advances in diagnosis, vaccine designing and control strategies - a comprehensive review. The Veterinary Quarterly. 2019;39(1):26–55. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2019.1580827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siva S, Chong H, Tan C. Ten year clinical and serological outcomes of Nipah virus infection. Neurology Asia. 2009;14:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradel-Tretheway BG, Zamora JLR, Stone JA, Liu Q, Li J, Aguilar HC. (2019) Nipah and Hendra virus glycoproteins induce comparable homologous but distinct heterologous fusion phenotypes. J Virol. 14, 93(13):e00577–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Steffen DL, Xu K, Nikolov DB, Broder CC. Henipavirus mediated membrane fusion, virus entry and targeted therapeutics. Viruses. 2012;4(2):280–308. doi: 10.3390/v4020280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yabukarski F, Lawrence P, Tarbouriech N, Bourhis JM, Delaforge E, Jensen MR, Ruigrok RW, Blackledge M, Volchkov V, Jamin M. Structure of Nipah virus unassembled nucleoprotein in complex with its viral chaperone. Nat StructMol Biol. 2014;21(9):754–759. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadav, P.D.; Raut, C.G.; Shete, A.M.; Mishra, A.C.; Towner, J.S.; Nichol, S.T. (2012) Detection of Nipah virus RNA in fruit bat (Pteropus giganteus) from India Am J Trop Med Hyg. 87, 576–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Further Reading

- 30.Journal reference: 1. Haselbeck, A. and Hösel, W. (1993) Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 42, 207–219.

- 31.Chapter in book: 2. Gaastra, W. (1984), in Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 2: Nucleic Acids (Walker, J. M.,ed.), Humana, Totowa, NJ, pp. 333–341.

- 32.Book reference: 3. Franks, F. (1993) Protein Biotechnology, 2nd ed., Humana, Totowa, NJ

- 33.Report/Document: 4. Macgregor, S. (1993), PhD thesis, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK.

- 34.Online: 5. Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. Available from: wwwcancerorg. Accessed December 31, 2006.