Abstract

Racemose neurocysticercosis is an aggressive infection caused by the aberrant expansion and proliferation of the bladder wall of the Taenia solium cyst within the subarachnoid spaces of the human brain. The parasite develops and proliferates in a microenvironment with low concentrations of growth factors and micronutrients compared to serum. Iron is important for essential biological processes, but its requirement for racemose cyst viability and proliferation has not been studied. The presence of iron in the bladder wall of racemose and normal univesicular T. solium cysts was determined using Prussian blue staining. Iron deposits were readily detected in the bladder wall of racemose cysts but were not detectable in the bladder wall of univesicular cysts. Consistent with this finding, the genes for two iron-binding proteins (ferritin and melanotransferrin) and ribonucleotide reductase were markedly overexpressed in the racemose cyst compared to univesicular cysts. The presence of iron in the bladder wall of racemose cysts may be due to its increased metabolic rate due to proliferation.

Keywords: cisticercosis, neurocysticercosis, subarachnoid cyst, Taenia solium, ferritin, ribonucleotide reductase, iron metabolism

1. Introduction

Neurocysticercosis (NCC) is the infection of the central nervous system by larval cysts of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium and is one of the most important causes of seizures and epilepsy worldwide [1]. Cysts develop in the pig, the usual intermediate host or accidentally in humans, after ingestion of eggs containing the hexacanth embryo or oncosphere [2]. Once in the digestive tract, the eggs release oncospheres that penetrate the intestinal mucosa, enter the bloodstream, and lodge in muscles, eye, or brain [1, 2]. Mature vesicular cysts consist of a fluid-filled vesicle containing an invaginated scolex.

Clinical manifestations in NCC are varied but associated with the parasite burden, cyst location, and degree of inflammatory reaction [3]. Racemose NCC is the most severe and difficult to treat form of extraparenchymal NCC [4, 5]. The parasites located in the subarachnoid spaces are characterized by continuous growth of the bladder wall to form a multivesicular membranous structure known as racemose cysts [5].

The composition of the cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) is specialized, less complex and relatively deficient in growth factors and micronutrients compared to blood [6]. Nevertheless, racemose cysts develop and proliferate for long periods in this microenvironment [4]. Although the metabolic requirements of racemose cysts are unknown, this form of T. solium may have adapted to the special composition of the CSF.

Iron is an essential inorganic nutrient that plays an important role in numerous biological processes, including DNA and RNA synthesis, cellular respiration, enzyme activity, and metabolism [7]. Altered iron metabolism has been associated with carcinogenesis, drug resistance and immune evasion [8].

Iron metabolism involving uptake, storage, utilization, and export is highly controlled because free iron is toxic to cells [9]. Increased free iron concentrations in combination with H2O2 generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) through Fenton reactions [10], which can promote DNA strand breaks, mutagenesis, activation of oncogenes, or inhibition of tumor suppressor genes, as well as protein damage, and lipid peroxidation [10]. The toxic effects of free iron are ameloriated by ferritin that stores iron for later use [11].

Despite the fundamental role of iron as a cofactor in several cellular processes, there is little information on the mechanisms for iron uptake in T. solium and its role in the continuous proliferation of the bladder wall in a racemose form. By searching in the T. solium genome for the major iron-binding, and transport proteins, we have identified the genes for ferritin and melanotransferrin. Additionally, we identified the ribonucleotide reductase gene.

Ferritin (FT) is an iron-binding protein made up of 24 subunits of heavy (H) and light (L) chains, forming a spherical structure that can store 4,500 Fe3+ atoms [11]. FT circulates in the serum and is used as a marker of iron levels. High levels of ferritin expression have been associated with different pathologies [12].

Melanotransferrin (MTF) is a homolog of serum iron transport protein transferrin [13]. MTF is mainly anchored to the cell membrane surface showing a bilobed structure; it contains disulfide bonds and an iron-binding site at the N-terminal end. MTF is highly expressed in melanoma cells [13].

Ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) is a key enzyme for de novo synthesis of deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) [14], the building blocks for the replication and repair of DNA [14, 15]. RNR catalyzes the substitution of the 2’-OH of a ribonucleoside di- or triphosphate by a hydrogen atom and uses metals such as iron or manganese as cofactors [16]. The most studied RNRs are the class IA which employs a di-iron center as a cofactor to generate the tyrosyl radical [15, 16]. Eukaryotes have only class Ia RNR enzymes [15].

Using histopathology methods and molecular analysis by quantitative PCR; we compared iron metabolism between two forms of T. solium cysts. Our results demonstrate the presence of iron deposits in the bladder wall of the racemose cysts and a significant increase in the expression levels of FT, MTF, and RNR. These results suggest that they are related to the increased cell proliferation in this anomalous form of the larvae.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental design

Bladder wall tissue samples from univesicular and racemose T. solium cysts were used to identify ferric iron deposits by Prussian blue stain. Additionally, total RNA isolated from univesicular and racemose cysts was used to compare the expression levels of FT, MTF, and RNR.

2.2. Parasite sample collection

Portions of racemose cysts discarded after surgical intervention of NCC patients were collected, anonymized, and transported to the laboratory in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) pH 7.4. The viability of these bladder wall samples was assessed by double staining with methylene blue and mitotracker as previously described [17]. The use of discarded, anonymized racemose NCC samples was approved by the Ethics Committee of Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Neurológicas (INCN) in Lima, Peru (242-2018-DG-INCN).

Naturally infected pigs were purchased from endemic cities of Peru, transported to veterinary facilities of Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (UNMSM) in Lima, and humanely euthanized [18]. Univesicular cysts were removed from the skeletal muscle of infected pigs and transported to the laboratory in PBS pH 7.4 (Gibco-Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 g/ml streptomycin from Gibco-Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD).

Cysts of T. crassiceps ORF strain were maintained by intraperinoneal passage of infected six-week-old female BALB/c mice [19]. The animals were humanely sacrified and the cysts were collected from the abdominal cavity and washed three times with sterile (PBS) pH 7.4.

The protocols for the use of animals were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committees for the Use of Animals of the Veterinary School of UNMSM (Protocol number 006) and UPCH (Protocol numbers 62392 and 101250).

2.3. Sample processing

Sections of cyst bladder walls were either fixed in neutral buffered formalin and paraffin-embedded for histology, or preserved in RNAlater (Qiagen) at −70°C for isolation of total RNA.

2.3.1. Prussian blue stain in bladder wall tissue samples

The iron content in tissue samples was determinated using the iron stain kit (Prussian blue stain) (ab150674, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples of T. solium (6 racemose and 10 univesicular cysts) and T. crassiceps (10 cysts) were cut in 4 μm thick sections and placed on poly-L-lysine coated slides. Sections were deparaffinized at 56°C, rehydrated in solutions with decreasing proportions of ethanol (100% to 70%), then incubated in iron stain solution (combining equal volumes of potassium ferrocyanide and hydrochloric acid solutions) for 3 min. The sections were washed with distilled water, stained with nuclear fast red solution for 5 min, dehydrated in 95% ethanol and then in absolute etanol. Mouse spleen tissue was used as a positive control. Slides were examined with a light microscope (Primo Star, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and photographed with a calibrated camera (AxioCam ICc1, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using AxioVision software (version 4.6, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.3.2. Isolation of total RNA, synthesis of cDNA and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for ferritin, melanotransferrin, and ribonucleotide reductase

Quantitative PCR was performed on T. solium cysts samples (5 univesicular and 5 racemose). The bladder wall and scolex of each univesicular cyst was separated manually with a scapel for isolation of total RNA. They were homogenized in 1ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for standard RNA isolation, concentrations were determined using a UV spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Products, Wilmington, DE). cDNA was produced from 500 ng of total RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with MultiScribe RT polymerase and random primers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a final volume of 20 μl per reaction. This was followed by incubation for 10 min at 25°C followed by 60 min at 37°C, 5 min at 95°C on a SimpliAmp Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed in 10 μl reaction volumes using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Gene Supermix (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with designed primers for ferritin (TsM_000026400) (Forward: 5’-TGGTGGCCGCATTGTTTA-3’) (Reverse: 5’-CATTGACCTCTCGCTCGATTT-3’), melanotransferrin (TsM_000830600) (Forward: 5’-GAATTCCCGCTCGTCTCATTAT-3’) (Reverse: 5’-TTCCTGGTGCTGCATTAGTC-3’), ribonucleotide reductase (TsM_000697400) (Forward: 5’-CTACGGCGGAAAGGGTTTAT-3’) (Reverse: 5’-AGCGACAATTCATGCCAATAAG-3’) and gapdh genes (TsM_000056400) (Forward: 5’-TCCAAGAGATGAATGCCAATGC-3’) (Reverse: 5’-CAGAAGGAGCCGAGATGATGA-3’). The sequences of the genes are available in the repository (WormBase, https://parasite.wormbase.org/Taenia_solium_prjna170813/Info/Index/ ). qPCR reactions, run in triplicate, used the following cycling parameters: preincubation of 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C, on a Lightcycler 96 System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The bladder wall of univesicular cyst was used as a calibration sample and we expressed the results as relative to the expression of the gapdh (housekeeping gene) using the 2−ΔΔCT formula [20].

2.3.3. Statistical analysis

Non-parametric statistic (Mann-Whitney U test for two groups) were calculated using Prism software (Graphpad, San Diego, CA) for comparisons of the gene expression between bladder wall of both types of T. solium cysts (racemose and univesicular). Differences with P value <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

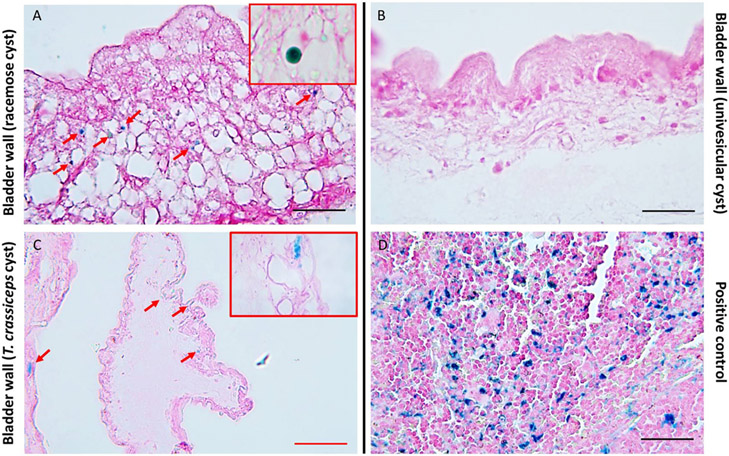

3.1. Racemose cysts of T. solium have iron deposits in the bladder wall.

Using racemose and univesicular cyst tissue samples, we evaluated the iron content by Prussian blue stain. We observed iron deposits only in the bladder wall of the racemose cyst (average: 225 iron deposists per mm2 of tissue); these iron deposits were completely absent in univesicular cysts (Fig. 1A, B). In addition, using samples of T. crassiceps cysts, we observed iron deposits in the bladder wall near to the bud’s development (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1. In situ identification of iron deposits in the bladder wall of T. solium racemose cyst and T. crassiceps.

Prussian blue stain performed on racemose cysts (A), univesicular cyst (B), and T. crassiceps cyst (C). Deposits of ferric iron were observed only in the bladder wall of racemose larvae and T.crassiceps (red arrows). Inserts (red box in A and C) are higher magnification images. Mouse spleen tissue (D) was used as a positive control. Representative images. Red scale bar: 100 μm, black scale bars: 50 μm.

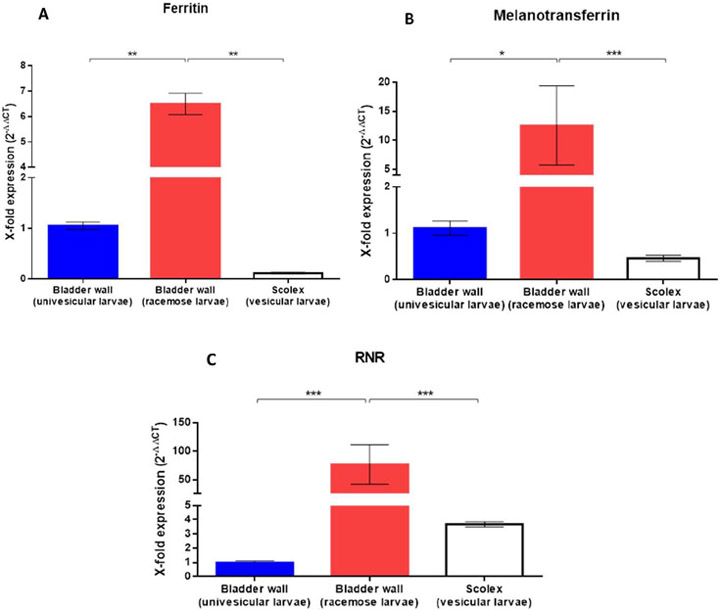

3.2. Expression levels of FT, MTF, and RNR are increased in the racemose cyst of T. solium.

Expression levels of the two iron-binding proteins and RNR were determined by quantitative PCR using specific primers. The expression levels of the three genes were significantly increased in racemose cysts compared to univesicular cysts (FT median: 6.4 in bladder wall of racemose cyst versus 1.0 in bladder wall of univesicular cyst, P value < 0.0022, Mann-Whitney U test); (MTF median: 10.16 in bladder wall of racemose cyst versus 1.0 in bladder wall of univesicular cyst, P value < 0.0121, Mann-Whitney U test); (RNR median: 89.88 in bladder wall of racemose cyst versus 0.06 in bladder wall of univesicular cyst, P value < 0.0004, Mann-Whitney U test) (Fig. 2).

Fig 2. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) for ferritin, melanotransferrin, and ribonucleotide reductase genes.

Quantitative PCR of cDNA from 500 ng of total RNA from racemose cysts compared to the bladder wall and scolex of univesicular cysts. Results are normalized to the housekeeping gapdh gene and expressed as fold increase expression. Statistically significant differences in levels of gene expression are indicated by asterisks (Mann-Whitney U test). Asterisks represent level of significance: *: P <0.05; **: P <0.01; ***: P <0.001

4. Discussion

Racemose NCC is the most aggressive form of the disease, characterized by continuous parasite growth in the subarachnoid space [5]. Patients’ symptoms with this type of infection are due to the mass effect produced by the growth of the parasite and exacerbated local inflammation [4]. The causes that lead to racemose cyst formation, as well as the molecular and metabolic changes leading to proliferation are unknown.

Iron is an indispensable element for multiple essential processes, including the synthesis of cofactors for energy production through the transfer of electrons between mitochondrial respiratory complexes [21]. The data presented herein suggest that the racemose parasites have increased requirements for iron compared to univesicular cysts. This is supported by three findings. First, iron was found within the bladder wall of the racemose cysts and not within the homologous structure of univesicular cysts (Fig. 1A, B). Secondly, mRNA of ferritin, an iron-binding protein, and melanotransferrin, a proposed iron transport protein, are highly expressed in racemose cysts compared to univesicular cysts (Fig. 2A, B). Additionally, the transcription level of ribonucleotide reductase, a third protein that requires iron for activity [22], was highly increased (Fig. 2C). Thirdly, iron deposits were detected near the budding of T. crassiceps (Fig. 1C), a region of proliferation [19]. These data suggest that racemose cysts require more iron to support the growth and proliferation of the bladder wall than vesicular cysts.

Previous studies demonstrate that T. solium cysts establish mechanisms to acquire nutrients from host tissue [23-25]. It has been postulated that the univesicular cyst would uptake haptoglobin-hemoglobin complexes from the host as an iron source [25]. However, the racemose cyst develops in a particular microenvironment, which means that the parasite does not have the same nutritional sources.

The gene expression assays demonstrate a significant increase in mRNA levels of the three evaluated genes suggesting an adaptation of the parasite to uptake and store the sparse iron present in the CSF. However, it is an indirect evaluation of the protein levels present in the parasite. We did not measure the amount and activity of proteins of the expressed genes, which is being contemplated.

Our comparison group was composed of viable muscle cysts samples from pigs pertaining to a study of brain inflammation and damage in porcine NCC, and as such specimens from brain cysts were not available. However, the morphological and histological characteristics of muscle and brain porcine cysts have been compared multiple times in the literature and no significant differences have been noted.

Previously, we reported the presence of proliferative cells in the bladder wall of the racemose cyst of T. solium [17], and these cells have an active MAPK signaling pathway [26]. To ensure cell division, the parasite requires maintaining levels of dNTPs necessary for the synthesis of new DNA molecules. RNR is essential for the proliferation of cells because catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of dNTPs. The overexpression of RNR in racemose cysts suggests a close association between the presence of iron deposits and its participation in the continuous proliferation of the bladder wall.

The univesicular cyst constitutes a non-proliferative latent stage, while the racemose cyst presents different cellular and metabolic characteristics [17, 26]. The use of drugs such a deferoxamine (DFO), a chelating agents with anti-proliferative activity [27], could be tested in combination with praziquantel or albendazole for the treatment of racemose NCC, as an attempt to improve the efficacy of current anthelmintic treatment.

5. Conclusions

The racemose cyst of Taenia solium presents iron deposits in its bladder wall and an altered expression profiles on genes whose protein products, such as ferritin and melanotransferrin, participate in the uptake and storage of this metal. In addition, the parasite presents a significant increase in the expression level of ribonucleotide reductase, an enzyme that requires iron for the synthesis of dNTPs essential for DNA replication. The racemose cyst develops in a particular environment and alterations in iron metabolism suggest adaptations to supply its nutritional demands associated with the continued proliferation of the bladder wall. Alterations in iron metabolism provide potential new therapeutic targets to improve the efficacy of current treatment for racemose NCC.

Highlights.

Racemose neurocysticercosis is the most severe form of extra-parenchymal neurocysticercosis.

The bladder wall of the racemose cysts contains iron deposits compared to univesicular cysts.

Genes encoding proteins involved in iron metabolism are relatively highly expressed in racemose cysts.

Acknowledgments

Membership of the Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru is provided in the Acknowledgments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garcia HH, Gonzalez AE, Gilman RH. Taenia solium cysticercosis and its impact in neurological diseade. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 2020; 33(3): e00085–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawlowski ZS. Taenia solium: Basic biology and Transmission. In: Singh G, Prabhakar S. Taenia solium Cysticercosis from basic to clinical science. NY, USA: CABI Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nash TE, Garcia HH. Diagnosis and treatment of neurocysticercosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol 2011; 7: 584–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nash TE, O’Connell EM, Hammoud DA, Wetzler L, Ware JM, Mahanty S. Natural history of treated subarachnoid neurocysticercosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 2020; 102 (1): 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleury A, Carrillo-Mezo R, Flisser A, Sciutto E, Corona T. Subarachnoid basal neurocisticercosis: focus on the most severe form of the disease. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther 2011; 9(1): 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spector R, Robert Snodgrass S, Johanson CE. A balanced view of the cerebrospinal fluid composition and functions: Focus on adult humans. Exp. Neurol 2015; 273:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponka P Cellular iron metabolism. Kidney International. 1999; 55, Suppl 69:S2–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown RAM, Richardson KL, Kabir TD, Trinder D, Ganss R, Leedman PJ. Altered iron metabolism and impact in cancer biology, metastasis, and immunology. Front. Oncol 2020; 10:476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogdan AR, Miyazawa M, Hashimoto K, Tsuji Y. Regulators of iron homeostasis: new players in metabolism, cell death, and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci 2016; 41(3): 274–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon SJ, Stockwell. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat. Chem. Biol 2014; 10(1): 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacKenzie EL, Iwasaki K, Tsuji Y. Intracellular iron transport and storage: from molecular mechanism to heatlh implications. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 2008; 10: 997–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knovich MA, Storey JA, Coffman LG, Torti SV. Ferritin for the clinician. Blood Rev. 2009; 23(3): 95–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suryo Rahmanto Y, Bal S, Loh KH, Yu Y, Richardson DR. Melanotransferrin: search for a function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012; 1820(3): 237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductase. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2006; 75: 681–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torrents E Ribonucleotide reductases: essential enzymes for bacterila life. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol 2014; 4: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene BL, Kang G, Cui C, Bennati M, Nocera DG, Drennan CL, et al. Ribonucleotide reductases: structure, chemistry, and metabolism suggest new therapeutic targets. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2020; 89: 45–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orrego MA, Verastegui MR, Vasquez CM, Koziol U, Laclette JP, Garcia HH, et al. Identification and culture of proliferative cells in abnormal Taenia solium larvae: Role in the development of racemose neurocysticercosis. Plos Negl Trop Dis. 2021; 15(3):e0009303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzales AE, Bustos JA, Jimenez JA, Rodriguez ML, Ramirez MG, Gilman RH, et al. Efficacy of diverse antiparasitic treatments for cisticercosis in the pig model. Am.J.Trop.Med.Hyg 2012; 87(2): 292–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson P, White AC, Lewis DE, Thornby J, David E, Weinstock J. Sequential expression of the neuropeptides substance P and somastostain in granulomas associated with murine cysticercosis. Infect. Immun 2002; 78(8): 4534–4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta CT) method. Methods. 2001; 25(4): 402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane DJ, Merlot AM, Huang ML, Bae DH, Jansson PJ, Sahni S, et al. Cellular iron uptake, trafficking and metabolism: key molecules and mechanisms and their roles in disease. Biochi. Biophys. Act 2015; 1853: 1130–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puig S, Ramos-Alonso L, Romero AM, Martínez-Pastor MT, The elemental role of iron in DNA synthesis and repair. Metallomics. 2017; 9: 1483–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Illescas O, Carrero JC, Bobes RJ, Flisser A, Rosas G, Laclette JP. Molecular characterization, functional expression, tissue localization and protective potential of a Taenia solium fatty acid-binding protein. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 2012; 186: 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodríguez-Contreras D, Skelly PJ, Landa A, Shoemaker CB, Laclette JP. Molecular and functional characterization and tissue localization of 2 glucose transporter homologues (TGTP1 and TGTP2) from the tapeworm Taenia solium. Parasitology. 1998; 117: 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarrete-Perea J, Toledano-Magaña Y, De la Torre P, Sciutto E, Bobes RJ, Soberón X, et al. Role of porcine serum haptoglobin in the host-parasite relationship of Taenia solium cysticercosis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol 2016; 207(2): 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orrego MA, Verastegui MR, Vasquez CM, Garcia HH, Nash TE. Proliferative cells in racemose neurocysticercosis have an active MAPK signaling pathway and respond to metformin treatment. Int. J. Parasitol 2022; S0020-7519(22)00016–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donfrancesco A, Deb G, Dominici C, Pileggi D, Castello MA, Helson L. Effects of a single course of deferoxamine in neuroblastoma patients. Cancer Res. 1990; 50: 4929–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]