Abstract

Development of vaccines against bovine pneumonia pasteurellosis, or shipping fever, has focused mainly on Mannheimia haemolytica A1 leukotoxin (Lkt). In this study, the feasibility of expressing Lkt in a forage plant for use as an edible vaccine was investigated. Derivatives of the M. haemolytica Lkt in which the hydrophobic transmembrane domains were removed were made. Lkt66 retained its immunogenicity and was capable of eliciting an antibody response in rabbits that recognized and neutralized authentic Lkt. Genes encoding a shorter Lkt derivative, Lkt50, fused to a modified green fluorescent protein (mGFP5), were constructed for plant transformation. Constructs were screened by Western immunoblot analysis for their ability to express the fusion protein after agroinfiltration in tobacco. The fusion construct pBlkt50-mgfp5, which employs the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter for transcription, was selected and introduced into white clover by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Transgenic lines of white clover were recovered, and expression of Lkt50-GFP was monitored and confirmed by laser confocal microscopy and Western immunoblot analysis. Lkt50-GFP was found to be stable in clover tissue after drying of the plant material at room temperature for 4 days. An extract containing Lkt50-GFP from white clover was able to induce an immune response in rabbits (via injection), and rabbit antisera recognized and neutralized authentic Lkt. This is the first demonstration of the expression of an M. haemolytica antigen in plants and paves the way for the development of transgenic plants expressing M. haemolytica antigens as an edible vaccine against bovine pneumonic pasteurellosis.

Mannheimia haemolytica A1 is the principal microorganism responsible for bovine pneumonia pasteurellosis, or shipping fever, a major cause of sickness, death, and economic loss in the feedlot cattle industry (12, 33). Traditional immunization approaches using needle injection of various vaccine preparations have provided some degree of protection. However, needle injection requires the herding and restraint of the animals, inducing additional stress as well as incurring a substantial labor cost. As an alternative, we propose to develop a noninvasive means of delivery of the vaccine via the oral route by using transgenic plants expressing recombinant immunogens. Recent advances in the understanding of transgene expression and recombinant protein accumulation, stability, and processing in plants have allowed the development of novel strategies such as using edible plants for delivery of antigens for active immunization (for reviews, see references 24, 28, and 30).

The leukotoxin (Lkt) of M. haemolytica A1 is one of its major virulence factors (26). Lkt is secreted by M. haemolytica A1 and acts as a pore-forming cytolysin that inserts into the membrane of target cells (3), resulting in osmotic imbalance and cell lysis. This initiates a cascading effect that leads to tissue damage, pneumonia, and death of the animals (1, 4). Lkt is a member of the RTX family of cytolysins (31, 32). Several functional domains have been identified in the typical RTX cytolysin, one of which is a transmembrane hydrophobic region that is involved in insertion of the toxin into the target cells (31, 32). The genetic determinant that codes for Lkt has been characterized extensively in our laboratories. We have carried out genetic manipulation of the lktA gene for high-level expression in Escherichia coli and used this recombinant Lkt (rLkt) in a vaccine for conventional intramuscular injection (5). This rLkt was unable to cause damage to the target cells because it is unstable and loses biological activity rapidly. However, to completely ensure that the rLkt to be used for vaccines is devoid of any biological activities, we constructed derivatives of Lkt by removing the section of the lktA gene that codes for the putative hydrophobic transmembrane domains of the toxin. These derivatives, Lkt66 and the smaller Lkt50, would be incapable of inserting into the membrane and are therefore no longer cytotoxic. However, neutralizing antigenic epitopes of Lkt, mapped to a 227-amino-acid region at the C terminus of the protein (11, 17), were retained in these derivatives.

In this paper, we describe (i) the construction of Lkt66 and demonstrate that Lkt66 is capable of eliciting anti-Lkt neutralizing antibodies, (ii) the creation of transgenic clover plants that express Lkt50 fused with the green fluorescent protein (GFP), and (iii) the characterization of the Lkt50-GFP from clover as a candidate for development of an edible vaccine. GFP was used as a marker to provide a simple and rapid method to screen for expression of the fusion protein in transgenic plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

E. coli DH5α (Table 1) was used as the host for cloning and propagation of plasmids and was cultured in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with thymine (50 μg/ml) and ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml), or kanamycin (50 μg/ml) as necessary. M. haemolytica A1 (ATCC 43270) was used for production of total proteins and was grown in brain heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1Rifr containing the helper plasmid pMP90 (obtained from L. Erickson, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada) was routinely grown in YEP (yeast extract, 10 g/liter; peptone, 10 g/liter; and NaCl, 5 g/liter) supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and gentamicin (25 μg/ml) when required.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | Host strain for cloning | Laboratory stock |

| M. haemolytica A1 | Wild-type strain | ATCC 43270 |

| A. tumefaciens C58c1Rifr | Host strain for plant transformation | L. Erickson |

| Plant strains | ||

| Trifolium repens L. cv. Osceola | White clover for transgenic plant production | Speare Seeds |

| N. tabacum cv. PetH4 | Tobacco for transient gene expression | Laboratory stock |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLKT60 | Vector containing lktA | 27 |

| pLKTΔN | Vector containing lkt66 | This study |

| p35S-GFP | Cloning vector containing wild-type gfp | Clontech |

| p35S-mgfp5-ER | Cloning vector containing mgfp5 | This study |

| p35S-lkt50-mgfp5 | Cloning vector containing lkt50-mgfp5 fusion | This study |

| p35S-mgfp5NS | Cloning vector containing mgfp5 lacking a stop codon | This study |

| pBINmgfp5-ER | Binary vector containing mgfp5 | 14 |

| pBlkt50-mgfp5 | Binary vector containing lkt50-mgfp5 fusion | This study |

| pBmgfp5-lkt50 | Binary vector containing mgfp5-lkt50 fusion | This study |

| pBp mgfp5-ER | Binary vector containing a promoterless mgfp5 | This study |

Recombinant DNA methods, nucleotide sequencing, and PCR.

All DNA cloning and ligation were carried out using standard recombinant DNA techniques (2, 25). E. coli competent cells were transformed either by the CaCl2 method or by electroporation according to our standard laboratory procedure. A. tumefaciens was transformed by electroporation (10). Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli using kits from Qiagen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) or Gibco BRL (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). The constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing at the Laboratory Services Division (University of Guelph) on double-stranded plasmid DNA templates using an ABI 377 Prism automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems International, Foster City, Calif.) based on cycle sequencing with dye-terminator dideoxynucleotides for fluorescence detection of terminated DNA strands.

PCR was carried out in thin-walled Microfuge tubes (Gordon Technologies, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) in a Cetus DNA 480 or a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR System 2400 Thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). PCR primers were synthesized at the Laboratory Services Division. A typical 50-μl reaction mixture contained 10 to 100 ng of template, 50 to 100 pmol of each primer, a 0.2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2 to 4 mM MgSO4 in the PCR buffer supplied by the manufacturer. The reaction included a hot start of 2 to 5 min at 95°C, followed by the addition of 1 U of Taq polymerase (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Quebec, Canada) or Pwo polymerase (Roche Diagnostics) and then 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 45 to 65°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min.

Construction of Lkt66.

The plasmid pLKT60 (Table 1) contains the lktCA genes cloned behind the tac promoter (27) and was used as the starting material for construction of the Lkt derivatives. Plasmid pLKT60 DNA was digested and religated at two NaeI sites located within the lktA sequence (Fig. 1). The ligated DNA was transformed into competent E. coli cells. Plasmid DNA from ampicillin-resistant colonies was isolated and mapped by restriction endonucleases to confirm removal of the NaeI fragment. The DNA was also sequenced using a primer based on the lktA sequence to confirm that the nucleotides across the NaeI site had not been altered. This plasmid was designated pLKTΔN and should express a 66-kDa Lkt derivative.

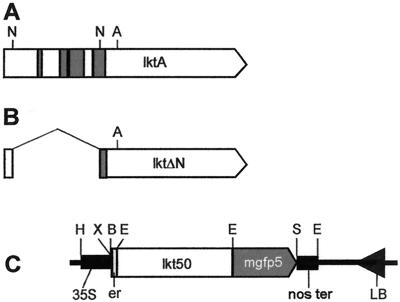

FIG. 1.

Gene maps for Lkt and Lkt derivatives. (A) Map of lktA, which encodes the full-length Lkt102, is shown. Shaded regions (A and B) indicate sequences encoding hydrophobic domains. Deletion of the NaeI fragment results in lktΔN (B), which produces Lkt66. A naturally occurring ApoI site (1349) in lktA was used to construct the fusion gene shown in panel C. PCR was used to add an EcoRI site at position 2701, and the resulting ApoI-EcoRI fragment which encodes Lkt50 was inserted between the signal peptide and GFP coding sequences. (C) Diagram showing part of the T-DNA region of pBlkt50-mgfp5 containing the lkt50-mgfp5 fusion gene and flanking regions from the HindIII (H) restriction site to the left border repeat (LB). Expression of the fusion gene is driven by the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (35S). The fusion gene consists of a signal peptide-encoding sequence (er), lkt50, and mgfp5. The polyadenylation signal from the nopaline synthase gene (nos ter) is found immediately downstream of the fusion gene. Restriction sites and their positions on pBlkt50-mgfp5 are as follows: H, HindIII (4950); X, XbaI (5815); B, BamHI (5821); E, EcoRI (5901, 7254, and 8257); and S, SacI (7990). Numbering of pBlkt50-mgfp5 starts at the pRK2 origin of replication as in pBin19 (8) but goes in the direction of right border to left border.

Production of anti-Lkt66 antibodies in rabbits.

Plasmid pLKTΔN was introduced into E. coli DH5α also harboring the plasmid pWAM716, which carries the hlyBD secretion genes (7). Lkt66 was recovered from the culture supernatant of the E. coli cells using the HlyBD secretion system according to our laboratory procedure (22). Briefly, a log-phase culture of the E. coli grown in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with ampicillin and chloramphenicol was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (0.5 mM) for 1 h. The culture supernatant was recovered after two centrifugation steps at 10,200 × g and concentrated 10-fold using an Amicon (Oakville, Ontario, Canada) ultrafiltration apparatus with a membrane cutoff of 50 kDa. The concentrated fluid was dialyzed extensively against distilled water at 4°C and lyophilized. A small aliquot of the powder (10 mg) was examined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) to confirm the presence of a 66-kDa protein corresponding to the truncated Lkt. The lyophilized powder was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a concentration of 200 μg/ml, and 0.4 ml was injected intramuscularly into rabbits for the production of antibodies as described below.

Construction of the lkt50 and gfp fusion gene.

The binary vector pBINmgfp5-ER, obtained from J. Haseloff (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom), contains the mgfp5-ER gene that encodes the GFP variant mGFP5 which has enhanced expression in plants and is targeted and retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (14). For simplicity, the mGFP5 variant is referred to as GFP in all subsequent descriptions.

The HindIII-SacI fragment from pBINmgfp5-ER containing the mgfp5-ER sequence was used to replace the HindIII-SacI fragment (containing wild-type GFP) of plasmid p35S-GFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) to produce p35S-mgfp5, a smaller vector, for the following manipulations.

To construct an lkt derivative for cloning into plants, the sense primer 5′-CAAGATAATATGAAATTCTTACTGAACTTA, which annealed to positions 1855 to 1884 of lktA (20) containing an ApoI site (underlined), and antisense primer 5′-GCTATGTTTGAGGAATTCATAGTTCTCAAC, which annealed to positions 3237 to 3208 and added an EcoRI site (underlined), were used to amplify a 1.35-kbp fragment that codes for amino acids 451 to 901 of Lkt. The PCR product was digested with ApoI and EcoRI and was cloned into p35S-mgfp5 partially digested with EcoRI. Plasmid DNA from E. coli transformants was isolated and mapped to select for the insertion of the PCR fragment in the correct orientation between the sequence encoding the signal peptide and GFP in p35S-mgfp5, creating p35S-lkt50-mgfp5. Subsequently, the HindIII-SacI fragment that contained the lkt50-mgfp5 sequence was subcloned back into pBINmgfp5-ER between the unique HindIII and SacI site to create pBlkt50-mgfp5 (Fig. 1).

To construct the binary vector containing the mgfp5-lkt50 fusion (pBmgfp5-lkt50), a vector containing mgfp5 lacking a stop codon was first made. A 933-bp PCR product was amplified from p35S-mgfp5 using the sense primer 5′-GATGACGCACAATCCCACTATC, which annealed to the 35S promoter 83 nucleotides upstream of the XbaI site, and the antisense primer 5′-GGAAATTCGAGCTCGTAAAGCTC, which removed the stop codon and added a SacI restriction site (underlined). The PCR product was digested with XbaI and SacI and used to replace mgfp5 in p35S-mgfp5, resulting in p35S-mgfp5NS. The lkt sequence in pBlkt50-mgfp5 was amplified using the sense primer 5′-GCCGAGCTCTTACTGAACTTAAAC, which changed the upstream EcoRI site to a SacI site (underlined), and the antisense primer 5′-TTTACTGAGCTCTTAGTTATCAACAAC which changed the downstream EcoRI site to a SacI site (underlined) and introduced a new stop codon (boldface type). The 1.37-kbp PCR product was digested with SacI and inserted into SacI-digested p35S-mgfp5NS, resulting in p35S-mgfp5-lkt50. The fusion was then subcloned into the binary vector by replacing the EcoRI fragment containing mgfp5-ER in pBINmgfp5-ER with the EcoRI fragment from p35S-mgfp5-lkt50 containing the mgfp5-lkt50 fusion.

Transient expression in tobacco by agroinfiltration.

To assess the expression of transgenes in plants, they were transiently expressed by infiltrating tobacco leaves (Nicotiania tabacum cv. PetH4) with A. tumefaciens cultures containing the various constructs as previously described (6) with modifications. Briefly, A. tumefaciens (carrying the plasmid constructs) was grown in Luria-Bertani broth with 10 mM MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid) (pH 5.6); 20 μM acetosyringone; and antibiotics at 28°C for 16 h. After centrifugation, the culture was resuspended to an optical density at 600 nm of 1 in Murashige and Skoog (MS) (23) salts with 2% sucrose; 0.5 mM MES (pH 5.6); and 100 μM acetosyringone. Infiltrated plants were kept humid by covering with clear plastic bags. After 3 to 4 days, GFP fluorescence could be observed in some cases by fluorescence microscopy (see below). To investigate the transient production of fusion protein, the infiltrated leaf areas were excised and extracted proteins examined by Western immunoblot analysis as described below.

A. tumefaciens-mediated plant transformation.

White clover (Trifolium repens L. cv. Osceola) transformation was performed essentially as described (18) with modifications. White clover seeds obtained from Speare Seeds (Harriston, Ontario, Canada) were surface sterilized and imbibed on 0.5× MS basal medium supplemented with Gamborg's vitamins (9) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and 2% sucrose for 1 to 3 days at room temperature. Hypocotyls were cut from the germinated seeds, leaving a 1- to 2-mm segment of the stalk attached to the cotyledons. Where possible, the apical shoot tip was removed. The two cotyledons were either completely or partially separated but still attached to the bisected hypocotyl. A. tumefaciens for cocultivation was grown in selective YEP to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 to 0.8. Cotyledons were immersed in the A. tumefaciens culture and gently agitated for 40 min. Excess bacterial culture was removed by blotting, and the cotyledons were cocultivated on MS basal medium with Gamborg's vitamins, 3% sucrose, N6-benzyladenine (1 mg/liter), α-naphthaleneacetic acid (0.1 mg/liter; Sigma), 100 μM acetosyringone (Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) and 0.3% phytagel (Sigma), pH 5.5, at room temperature in the dark for 4 to 5 days. The cotyledons were then transferred to selective regeneration medium consisting of MS basal medium with Gamborg's vitamins, N6-benzyladenine (1 mg/liter), α-naphthaleneacetic acid (0.1 mg/liter), kanamycin (100 mg/liter), ticarcillin (250 mg/liter) and clavulanic acid (8.3 mg/liter) (Timentin; Smith Kline Beecham Pharma, Oakville, Ontario, Canada), and 0.3% phytagel, pH 5.8. After 6 weeks, green shoots were isolated and placed in Magenta boxes (Sigma) containing a rooting medium of 0.5× MS basal medium with Gamborg's vitamins, 3% sucrose, kanamycin (100 mg/liter), ticarcillin (250 mg/liter), and clavulanic acid (8.3 mg/liter).

Presence of the transgene in the plantlets was confirmed by PCR using the sense primer 5′-CCACTATCCTTCGCAAGAC, which anneals to the 35S promoter region, and the antisense primer 5′-TGTTGCATCACCTTCACCCTCTC, which anneals to the mgfp5 coding region. Genomic DNA was isolated using a commercial kit (DNeasy Plant Mini Kit; Qiagen). Selected transgenic plantlets were potted in soil and maintained in the greenhouse.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Conventional epifluorescence microscopy was carried out using a Leica (Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada) MZIII fluorescence stereomicroscope with a GFP3 filter set (excitation at 470 nm with a band width of 40 nm; emission at 525 nm with a band width of 50 nm). Laser scanning confocal microscopy (model MRC-600 microscope; Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) was used to visualize GFP fluorescence in transgenic plants. For confocal microscopy, observations were made on plant tissue sections mounted in water.

SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis.

To prepare plant protein extracts for SDS-PAGE, plant tissue samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground, and homogenized with an extraction buffer consisting of PBS containing 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.5% (wt/vol) Tween 20. One- and two-milliliter aliquots of buffer were used per g (fresh weight) of tobacco and clover tissue, respectively. Plant proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE as described by Lee and Huttner (19). Prestained SDS-PAGE standards (Bio-Rad) were used for molecular mass determinations. For Western immunoblot analysis, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) after SDS-PAGE (29). The membranes were probed with either a rabbit anti-Lkt66 antiserum, a mouse anti-Lkt monoclonal antibody (MAb 601, obtained from S. Srikumaran, University of Nebraska, Lincoln) or a rabbit anti-GFP antiserum (Clontech).

Western immunoblots were also used to detect the production of antibodies against Lkt in rabbits immunized with transgenic plant extracts. In these experiments, an Lkt-containing M. haemolytica A1 cell suspension prepared as previously described (21) was separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with the various rabbit immune sera.

Lkt50-mGFP5 stability.

Clover was harvested and allowed to dry at room temperature and ambient humidity for 1 to 4 days. Proteins were extracted by grinding the tissue in 2 ml of PBS per g (fresh weight) with a Kontes ground-glass tissue grinder followed by centrifugation at 9,300 × g for 10 min. The extract was analyzed by Western immunoblotting using the monoclonal antibody to Lkt.

Preparation of Lkt50-mGFP5 extracts for immunization.

Two different clover extracts were used for immunization. A crude extract was prepared by first grinding clover tissue to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen in a prechilled mortar and pestle. Proteins were extracted using 2 ml of extraction buffer (PBS containing 0.5% [wt/vol] Tween 20) per g (fresh weight). Insoluble material was removed by two rounds of centrifugation at 4°C (30,000 × g for 30 min followed by 130,000 × g for 1 h). The resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size syringe filter (Nalgene, Rochester, N.Y.) and stored at −20°C.

A second extract, enriched with recombinant fusion protein, was prepared by chromatofocusing (Pharmacia, Baie d'Urfé, Quebec, Canada). After grinding of the clover leaf tissue, the proteins were extracted in a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1% (wt/vol) Tween 20 and centrifuged at 130,000 × g as described above. The supernatant was applied to a PBE 94 column equilibrated with 25 mM imidazole-HCl (pH 7.4). Proteins were eluted with Polybuffer 74-HCl (pH 4.0), and 3-ml fractions were collected. Fractions containing Lkt50-GFP fusion protein were identified by Western immunoblotting with the anti-Lkt66 antiserum.

Rabbit immunization.

New Zealand White rabbits (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) were injected intramuscularly with 1 ml of filtered plant extract twice at a 2-week interval. The vaccine preparations contained a combination of saponin (1.5% Quil A; Cederlane Laboratories, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) and aluminum hydroxide (23%) as adjuvant, in a ratio of 3 parts antigen to 1 part adjuvant. A final dose was administered 4 weeks after the second injection. Blood was collected 4 weeks after the final injection of antigen. Two rabbits were immunized with each extract. Serum was analyzed by Western immunoblotting and for Lkt neutralization activity using a modified neutral red cytotoxicity assay (16).

RESULTS

Construction of lktΔN and lkt50

An examination of the nucleotide sequence of lktA revealed the presence of two NaeI sites at positions 616 and 1651 within the gene (Fig. 1). Upon digestion with NaeI and religation of plasmid pLKT60, a 1,035-bp fragment that coded for 345 amino acids containing hydrophobic domains was removed. The resulting Lkt derivative (Lkt66) expressed from lktΔN is expected to lack toxicity and thus is an ideal candidate for further vaccine development studies.

Another derivative was constructed to take advantage of suitable nucleotide sequences for primer design to incorporate restriction sites to amplify the lktA gene for cloning into plants. PCR was used to amplify a 1.35-kbp section of the lktA gene. This fragment coded for amino acids 451 to 901 of Lkt and did not include the N-terminal and the C-terminal regions of Lkt, thus removing potential targeting signals that may interfere with its expression and/or localization in plants. This derivative, lkt50, was used in subsequent cloning of fusion genes into a binary vector for introduction into plants.

Immunogenicity of Lkt66.

To ensure that the Lkt derivatives that lacked the hydrophobic domains were still effective as vaccine candidates, Lkt66 was expressed in E. coli, recovered from the culture supernatant, and used to immunize rabbits. The resulting rabbit anti-Lkt66 antiserum was tested in Western immunoblots as well as for toxin neutralization against the authentic Lkt from M. haemolytica A1. In addition to recognizing Lkt66 as expected (data not shown), anti-Lkt66 antiserum immunostained the full-length Lkt (102 kDa) from M. haemolytica A1 (see Fig. 6A, lane 7). Moreover, anti-Lkt66 antiserum exhibited a neutralizing titer (−log2) of up to 5 (1/32 dilution) against the authentic Lkt. This is similar to the neutralizing titer obtained when the rabbits were immunized with full-length rLkt. These results demonstrated that the hydrophobic regions of the Lkt which were removed are not critical for immunogenicity. The rabbit anti-Lkt66 antiserum was used in subsequent immunoblots in this study.

FIG. 6.

Immunogenicity of Lkt50-GFP produced by white clover. (A) Rabbits (duplicate rabbits used for each treatment) were mock immunized with saline and adjuvant (lanes 1 and 2) or immunized with chromatographic fractions enriched in Lkt50-GFP (lanes 3 and 4) or a saline extract from transgenic clover (lanes 5 and 6). Immune sera were used to probe a total M. haemolytica A1 protein preparation blotted onto nitrocellulose. The rabbit anti-Lkt66 antiserum (lane 7) was used as a positive control. Immune serum from all four rabbits immunized with Lkt50-GFP-containing fractions recognized a 102-kDa band (arrow) migrating identically with full-length Lkt that was immunostained with anti-Lkt66 (lanes 3 to 7). Immune serum from rabbit 41 (panel A, lane 6) was analyzed to see if it cross-reacted with wild-type GFP. Duplicate blots (B and C) were prepared containing M. haemolytica A1 protein extract (lanes 1) and purified recombinant wild-type GFP (Clontech) (lanes 2). Anti-GFP antibodies (B) and rabbit 41 immune serum (C) were used to probe the membranes. Rabbit 41 immune serum was able to detect GFP (panel C, lane 2). These results suggested that the immune serum contained antibodies directed to both Lkt (panel A, lane 6, and panel C, lane 1) and GFP (panel C, lane 2). Migrations of molecular mass markers for both panels B and C (lanes M) are indicated to the left of panel B. Arrows (B and C) show the position of GFP migration.

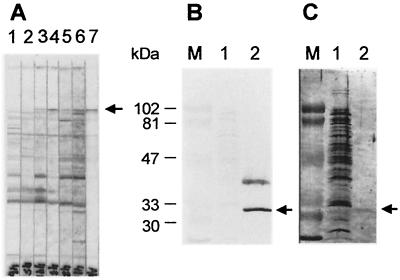

Transient expression of plasmid constructs in tobacco.

Two chimeric constructs, lkt50-mgfp5 and mgfp5-lkt50, were inserted into binary vectors and used to transform A. tumefaciens. For rapid assessment of their ability to direct the production of fusion proteins in plants, these genes were first expressed transiently in tobacco by infiltration. Constructs containing promoterless mgfp5-ER (F. Garabagi, unpublished data) and 35S-driven mgfp5-ER were used as controls for transient expression (Fig. 2A). Three to four days after infiltration, fluorescence was observed by microscopy only in plants injected with A. tumefaciens transformed with plasmid containing 35S-mgfp5-ER. Plants infiltrated with A. tumefaciens containing the promoterless construct exhibited no fluorescence. Little or no fluorescence was observed in the infiltrated regions of plants injected with A. tumefaciens containing either of the lkt50 fusion constructs (data not shown). The infiltrated areas were excised and examined for the presence of fusion protein by Western immunoblotting with rabbit anti-Lkt66. An immunoreactive band of approximately 79 kDa was present only in extracts of plants infiltrated with A. tumefaciens that carried the construct pBlkt50-mgfp5 (Fig. 2B). The size of this protein corresponded to that predicted from the nucleotide sequence of the construct. Thus, it appeared that only in the case in which GFP was fused to the C-terminal side of Lkt50 was there accumulation of a significant amount of the fusion protein. This construct was selected for the production of transgenic white clover lines.

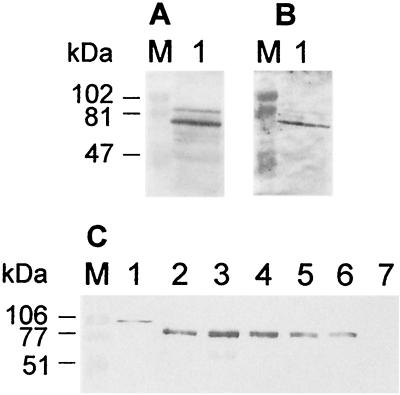

FIG. 2.

Transient expression of chimeric genes in tobacco. (A) Proteins extracted from tobacco leaves infiltrated with A. tumefaciens transformed with constructs containing promoterless mgfp5-ER (lane 1), 35S-mgfp5-ER (lane 2), or 35S-lkt50-mgfp5 (lane 3) were blotted and probed with rabbit anti-Lkt66 antiserum. The resulting Western immunoblot showed that a protein of 79 kDa was present only in lane 3, where the presence of the Lkt-containing fusion protein was expected. (B) The expression of Lkt50-GFP (lane 1) and GFP-Lkt50 after agroinfiltration (lane 2) was analyzed by Western immunoblotting with a rabbit anti-Lkt66 antiserum as described above. A. tumefaciens, transformed with vectors containing either lkt50-mgfp5 (lane 1) or mgfp5-lkt50 (lane 2), was used for infiltration. Only in the case where GFP was fused to the C terminus of Lkt50 (lane 1) was fusion protein expression detected. Migrations of the molecular mass markers are as indicated to the left of each panel.

Transgenic white clover expressing Lkt50-GFP.

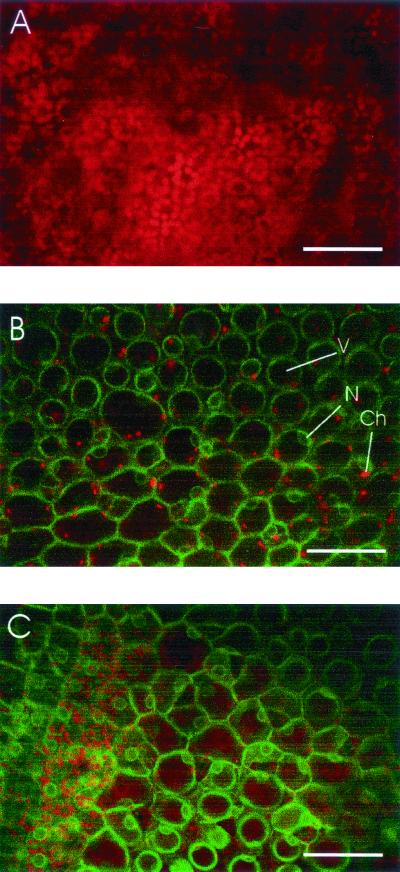

Transgenic clover lines expressing GFP and Lkt50-GFP were produced by A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation. PCR was used to confirm that the transgenes were present in transformed plants (data not shown). By conventional fluorescence microscopy, green fluorescence was easily detected in GFP-expressing plants. Consistent with the results obtained with transient expression, little to no fluorescence was observed in pBlkt-mgfp5-transformed plants. However, when these plants were further examined using laser scanning confocal microscopy, green fluorescence was detected in clover transformed with both the pBINmgfp5-ER and pBlkt50-mgfp5 constructs (Fig. 3B and C). As expected, GFP fluorescence was more intense than that observed for Lkt50-GFP. Leaves from untransformed plants did not exhibit green fluorescence (Fig. 3A). Red chlorophyll fluorescence from chloroplasts was seen in tissues from all plants. The pattern of green fluorescence observed in the clover leaves was consistent with localization of the recombinant protein in the ER (15). Cells contained large vacuoles, resulting in distribution of fluorescence around the cell periphery. The fusion protein exhibited a perinuclear localization and was clearly excluded from the nucleus. A characteristic reticulate network was seen in some cells when the appropriate plane of focus was used.

FIG. 3.

Laser confocal microscopy of transgenic white clover expressing Lkt50-GFP. A section of clover leaf was mounted in water and observed by confocal microscopy. Images from two channels (red for chlorophyll fluorescence and green for GFP fluorescence) were merged to produce the micrographs shown. Leaves from untransformed clover (A) do not exhibit the green fluorescence that is present in transgenic clover expressing Lkt50-GFP (B) or GFP (C). The patterns of green fluorescence in panels B and C were similar and are consistent with an ER localization. Fluorescence intensity in GFP-expressing plants was higher than that observed in Lkt50-GFP-expressing plants but was normalized in this figure to facilitate comparison. The bar in each panel indicates 100 μm. Vacuoles (V), nuclei (N), and chloroplasts (Ch) are indicated in panel B.

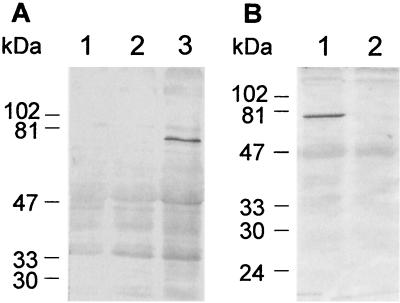

Expression of a recombinant fusion protein containing both Lkt50 and GFP epitopes was confirmed by Western immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4A and B). Both rabbit anti-Lkt66 and rabbit anti-GFP recognized a protein of 79 kDa. Preliminary scanning densitometric analysis of gels and Western immunoblots of extracts from one of the Lkt50-GFP-expressing clover lines suggested that the recombinant fusion protein constituted approximately 1% of the soluble proteins extracted from transgenic clover. This corresponds to approximately 18 μg of Lkt50-GFP per g (fresh weight) of plant tissue.

FIG. 4.

Expression of Lkt50-GFP in transgenic white clover. Expression of Lkt50-GFP in transgenic white clover was analyzed by Western immunoblotting. Duplicate blots of proteins extracted from one transgenic line were immunostained with either rabbit anti-Lkt66 antiserum (panel A, lane 1) or an anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (Clontech) (B). Molecular masses of the prestained SDS-PAGE standards (panels A and B, lanes M) are indicated at the left. Both antibodies detected a protein of similar size, providing evidence that a fusion protein containing both Lkt and GFP sequences was indeed produced by the transgenic clover. In addition, the size of the fusion protein observed was close to 79 kDa, as predicted from the nucleotide sequence. Stability of the Lkt50-GFP fusion protein was also examined (C). Protein extracts prepared from fresh transgenic clover (lane 2) or from transgenic clover dried for 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, or 4 days at ambient temperatures (lanes 3 to 6, respectively) were analyzed by Western immunoblotting. The blot was probed with the monoclonal antibody 601 against Lkt. As controls, M. haemolytica A1 supernatant (20 times concentrated) containing full-length Lkt and an extract from wild-type clover were loaded in lanes 1 and 7, respectively. Migrations of molecular mass markers (lane M) are shown on the left. After 4 days of drying at ambient temperatures, there does not appear to be significant loss of the Lkt50-GFP fusion protein.

To assess the stability of the fusion protein in harvested plants, transgenic clover expressing Lkt50-GFP was harvested and allowed to dry at ambient temperatures. After 3 days, the clover tissue retained approximately 20% of its initial fresh weight. Protein extracts were prepared from plant material at different stages of drying and analyzed by Western immunoblotting. After 4 days of drying, there did not appear to be significant degradation of the fusion protein (Fig. 4C). No lower-molecular-weight immunoreactive species were observed at any stage. Dried wild-type clover did not give rise to any immunoreactive bands.

Immunogenicity of Lkt50-GFP produced by transgenic white clover.

To determine if Lkt50-GFP synthesized by clover was able to elicit an immune response, rabbits were immunized with either a saline extract or an Lkt50-GFP-enriched chromatographic fraction prepared from transgenic clover.

The Lkt50-GFP-enriched fractions were produced by chromatofocusing. A soluble protein extract prepared from transgenic clover was applied to a PBE 94 column, and resulting fractions were analyzed by Western immunoblotting (Fig. 5). Most of the fusion protein eluted in fractions 6 to 8 (Fig. 5B); these fractions were used for rabbit immunization. The fusion protein could be partially separated from ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (rubisco, the most abundant protein in plant tissue), most of which eluted in fractions 5 and 6 (Fig. 5A). Under the conditions used in the fractionation, Lkt50-GFP was stable to degradation as indicated by the absence of any major lower-molecular-weight immunoreactive bands in the fractions.

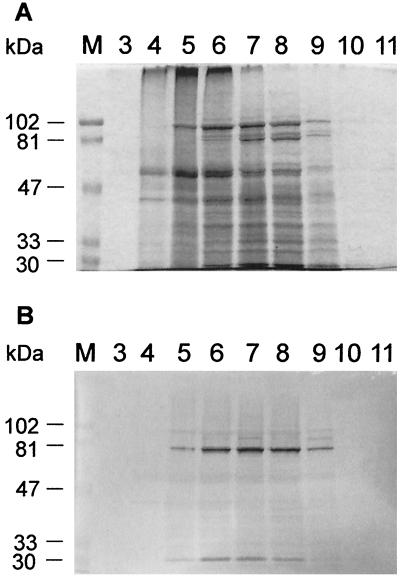

FIG. 5.

Preparation of Lkt50-GFP-enriched fractions for immunization. A protein extract was prepared from transgenic white clover and fractionated by chromatofocusing. Column fractions were analyzed by Coomassie blue staining of gels after SDS-PAGE (A) and Western immunoblotting (B). The fraction number is indicated on the top, and molecular mass markers (lanes M) are indicated at the left. These results show that Lkt50-GFP (panel B, fractions 6, 7, and 8) could be separated from rubisco (strongly staining band migrating at around 56 kDa) and other high-molecular-weight material (panel A, fractions 5 and 6).

Pre- and postimmunization sera were obtained from rabbits and tested for the presence of antibodies by Western immunoblotting (Fig. 6). All rabbits receiving extracts containing Lkt50-GFP as antigen produced antibodies directed against the authentic Lkt from M. haemolytica A1 (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 to 6). Preimmune sera (data not shown) and sera from mock-immunized rabbits (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 to 2) did not immunostain Lkt.

In addition to stimulating production of antibodies against Lkt, the fusion protein was also able to induce anti-GFP antibody production. Rabbit immune serum contained antibodies that weakly recognized wild-type GFP (Clontech) on Western immunoblots (Fig. 6C).

To determine if neutralizing antibodies were present in the rabbit sera, a toxin neutralization assay was performed (16). All rabbits immunized with Lkt50-GFP extracts as antigen exhibited neutralizing titers (−log2) up to 4 (1/16 dilution) (Table 2). Sera from rabbits immunized with wild-type white clover extract (data not shown), sera from mock-immunized rabbits, or preimmune sera from all the rabbits failed to neutralize Lkt (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Neutralizing titers of sera from rabbits immunized with Lkt50-GFP fusion protein

| Immunogen | Rabbit no. | Neutralizing antibody titera of serum

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-immune | Bleed 2 | Bleed 3 | Bleed 4 | ||

| Lkt50-GFP (saline extract) | 41 | — | — | 4 | 3.5 |

| Lkt50-GFP (saline extract) | 42 | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Lkt50-GFP (column fraction) | 43 | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Lkt50-GFP (column fraction) | 44 | — | — | 1.5 | 1 |

| Mock | 45 | — | — | — | — |

| Mock | 46 | — | — | — | — |

Values are mean reciprocal log2 serum dilutions giving at least 50% neutralization of toxicity; sera were assayed in duplicate. —, no neutralization activity.

DISCUSSION

As a member of the RTX family of toxins, the cytotoxic activity of Lkt is mediated by its ability to insert and form transmembrane pores in the plasma membrane of susceptible host cells, eventually leading to cell lysis. The hydrophobic regions in the Lkt protein have been implicated in mediating pore formation (31, 32). The lktAΔN derivative which expressed the Lkt66 molecule is an excellent candidate for use in a vaccine. With the removal of most of the hydrophobic domains, Lkt66 should be rendered incapable of inserting into the target cells to cause cytotoxicity. On the other hand, it still retains immunogenicity, as shown by its ability to elicit rabbit antibodies which neutralized authentic Lkt. Thus, we anticipate that if Lkt66 were used as a vaccine in calves, it would drive an immune response against the Lkt of M. haemolytica A1. A smaller derivative completely lacking all hydrophobic regions (Lkt50) was made during the subcloning of lktAΔN into the binary vector for A. tumefaciens-mediated plant transformation. This Lkt50 contained all of the antigenic regions of Lkt66 and produced an Lkt neutralizing response in rabbits, suggesting that it would also be useful as a vaccine candidate. Indeed, when proteins containing either Lkt66 or Lkt50 sequences were injected into rabbits, both antigens were able to elicit the production of toxin neutralizing antibodies.

GFP was used in this present study as a marker to enable rapid screening, to allow the monitoring of transgene expression, and to facilitate simple Mendelian analysis of inheritance. In addition, with the current concerns about transgene movement in the environment, GFP could be used as a reporter for tracking transgenic plants in the field (13).

Using stable transformed transgenic plants to study transgene expression usually requires several months' work. To rapidly assess whether the transgene construct will be expressed at significant levels in plants, we used a more convenient transient-expression assay by infiltrating tobacco leaves with A. tumefaciens carrying plasmid constructs. These studies do not require regeneration of plants after transformation and thus permit assessment of gene expression within a few days by examining transgenic protein expression directly by both fluorescence and Western immunoblotting. In our studies, agroinfiltration allowed us to identify the Lkt50-GFP construct as the choice for continued studies and transformation into white clover. This was crucial for subsequent plant transformation experiments since there was no previous documentation of the expression of M. haemolytica genes in plants. With a different codon usage bias, it is entirely possible that lkt is not expressed at significant levels in plants and would require extensive codon replacements before it could be used for expression in the transgenes. The failure of the GFP-Lkt50 construct to produce significant amounts of the fusion protein could be due to unknown factors that may cause inefficient or unstable transcription or translation, improper folding of the polypeptide, or rapid degradation of the fusion protein. While GFP is reported to be generally functional with both N- and C-terminal additions, our results underscore the limitations of this generalization.

Using conventional epifluorescence microscopy, little if any fluorescence was observed in Lkt50-GFP-expressing plants, even though the presence of fusion protein was detected by Western immunoblot analysis. By confocal microscopy, a more sensitive technique for visualizing fluorescence, we were able to observe fluorescence in Lkt50-GFP-expressing plants but at a lower intensity that that for plants expressing GFP alone. Even though both constructs were expressed from the same 35S promoter, it may be possible that less fusion protein was produced in the transgenic plants than in plants expressing GFP alone. An alternative explanation may be that the recombinant GFP was not able to properly fold when fused to Lkt50, resulting in reduced levels of fluorescence.

The Lkt50-GFP5 fusion protein contains an N-terminal signal peptide derived from Arabidopsis vacuolar basic chitinase and the C-terminal ER-retention sequence HDEL. Previous observations have indicated that higher levels of fluorescence in transgene products could be achieved if GFP entered the secretory pathway and was sequestered in the lumen of the ER (14, 15). Targeting proteins to the ER may improve maturation and accumulation and may protect plant cells from the phototoxic effects of GFP (14, 15). A significantly higher level of fluorescence has been observed in transgenic plants expressing mGPF5 than in plants expressing the wild-type GFP that localizes to the cytoplasm (F. Garabagi, personal communication).

Our results demonstrate that using plants to produce bacterial antigen as a vaccine component is a viable strategy. We showed that an Lkt fragment synthesized by plants was able to induce an immune response in rabbits that led to the production of antibodies that neutralized the authentic Lkt. Protein stability is important for vaccine harvest, production, and storage. Our results also indicated that the fusion protein was relatively stable in harvested material in the absence of refrigeration. Plants are economical to grow and can yield a high level of recombinant proteins. While alfalfa may be the optimal supplement for animal feed, white clover is a reasonable alternative, and the present study paves the way for continuing research into the development of an edible vaccine using a variety of transgenic plants expressing antigens of M. haemolytica A1. Experiments are in progress to assess the immunogenicity of plant-derived antigen in cattle and the effectiveness of feeding this transgenic material in stimulation of a mucosal immune response against the Lkt of M. haemolytica A1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Ontario Cattlemen's Association, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Strategic Grants Program, and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs.

We thank Betty-Ann McBey for assistance with the rabbit immunization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann M R, Brogden K A. Response of the ruminant respiratory tract to Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinkenbeard K D, Mosier D A, Confer A W. Transmembrane pore size and role of cell swelling in cytotoxicity caused by Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin. Infect Immun. 1989;57:420–425. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.420-425.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Confer A W, Clinkenbeard K D, Murphy G L. Pathogenesis and virulence of Pasteurella haemolytica in cattle: an analysis of current knowledge and future approaches. In: Donachie W, Lainson F A, Hodgson J C, editors. Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, and Pasteurella. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlon J A, Shewen P E, Lo R Y C. Efficacy of recombinant leukotoxin in protection against pneumonic challenge with live Pasteurella haemolytica A1. Infect Immun. 1991;59:587–591. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.2.587-591.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.English J J, Davenport G F, Elmayan T, Vaucheret H, Baulcombe D C. Requirement of sense transcription for homology-dependent virus resistance and trans-inactivation. Plant J. 1997;12:597–603. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felmlee T, Pellett S, Welch R A. Alterations of amino acid repeats in the Escherichia coli hemolysin affect cytolytic activity and secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frisch D A, Harris-Haller L W, Yokubaitis N T, Thomas T L, Harden S H, Hall T C. Complete sequence of the binary vector Bin 19. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:405–409. doi: 10.1007/BF00020193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamborg L O, Miller R A, Ojima K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp Cell Res. 1968;50:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(68)90403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelvin S B, Schilperoort R A. Plant molecular biology manual. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerbig D G, Cameron M R, Struck D K, Moore R N. Characterization of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody to Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1734–1739. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.1734-1739.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin D. Economic impact associated with respiratory disease on beef cattle. In: Vestweber J, St. Jean G, editors. Veterinary clinics of North America: food animal practice. W. B. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Co.; 1997. pp. 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper B K, Mabon S A, Leffel S M, Halfhill M D, Richards H A, Moyer K A, Stewart C N., Jr Green fluorescence protein as a marker for expression of a second gene in transgenic plants. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1125–1129. doi: 10.1038/15114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haseloff J, Siemering K R. The uses of green fluorescent protein in plants. In: Chalfie M, Kain S, editors. Green fluorescent protein: properties, applications, and protocols. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1998. pp. 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haseloff J, Siemering K R, Prasher D C, Hodge S. Removal of a cryptic intron and subcellular localization of green fluorescent protein are required to mark transgenic Arabidopsis plants brightly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2122–2127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodgins D C, Shewen P E. Vaccination of neonatal colostrum deprived calves against Pasteurella haemolytica A1. Can J Vet Res. 2000;64:3–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lainson F A, Murray J, Davies R C, Donachie W. Characterization of epitopes involved in the neutralization of Pasteurella haemolytica serotype A1 leukotoxin. Microbiology. 1996;142:2499–2507. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-9-2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larkin P J, Gibson J M, Mathesius U, Weinman J J, Gartner E, Hall E, Tanner G J, Rolfe B G, Djordjevic M A. Transgenic white clover. Studies with the auxin-responsive promoter, GH3, in root gravitropism and lateral root development. Transgenic Res. 1996;5:325–335. doi: 10.1007/BF01968942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee R W H, Huttner W B. Tyrosine-O-sulfated proteins of PC12 pheochromocytoma cells and their sulfation by a tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:11326–11334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo R Y C, Strathdee C A, Shewen P E. Nucleotide sequence of the leukotoxin genes of Pasteurella haemolytica A1. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1987–1996. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.1987-1996.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo R Y C, Mellors A. The isolation of recombinant plasmids expressing secreted antigens of Pasteurella haemolytica A1 and the characterization of an immunogenic 60 kDa antigen. Vet Microbiol. 1996;51:381–391. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo R Y C, Watt M-A, Gryoffy S, Mellors A. Preparation of recombinant glycoprotease of Pasteurella haemolytica A1 utilizing the Escherichia coli α-hemolysin secretion system. FEMS Microb Lett. 1994;116:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter L, Kipp P B. Transgenic plants as edible vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1999;240:159–176. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60234-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shewen P E, Wilkie B N. Cytotoxin of Pasteurella haemolytica acting on bovine leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1982;35:91–94. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.1.91-94.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strathdee C A. Molecular characterization of the Pasteurella haemolytica leukotoxin determinant. Ph.D. thesis. Guelph, Ontario, Canada: University of Guelph; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tacket C O, Mason H S. A review of oral vaccination with transgenic vegetables. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:777–783. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walmsley A M, Arntzen C J. Plants for delivery of edible vaccines. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2000;11:126–129. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welch R A. Pore-forming cytolysis of gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:521–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welch R A, Bauer M E, Kent A D, Ledds J A, Moayeri M, Regassa L B, Swenson D L. Battling against host phagocytes: the wherefore of the RTX family of toxins. Infect Agents Dis. 1995;4:254–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yates W D G. A review of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, shipping fever pneumonia and viral-bacterial synergism in respiratory disease of cattle. Can J Comp Med. 1982;46:225–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]