Abstract

Diatoms can use light in the blue-green region because they have chlorophyll c (Chlc) in light-harvesting antenna proteins, fucoxanthin and chlorophyll a/c-binding protein (FCP). Chlc has a protonatable acrylate group (–CH=CH–COOH/COO–) conjugated to the porphyrin ring. As the absorption wavelength of Chlc changes upon the protonation of the acrylate group, Chlc is a candidate component that is responsible for photoprotection in diatoms, which switches the FCP function between light-harvesting and energy-dissipation modes depending on the light intensity. Here, we investigate the mechanism by which the absorption wavelength of Chlc changes owing to the change in the protonation state of the acrylate group, using a quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical approach. The calculated absorption wavelength of the Soret band of protonated Chlc is ∼25 nm longer than that of deprotonated Chlc, which is due to the delocalization of the lowest (LUMO) and second lowest (LUMO+1) unoccupied molecular orbitals toward the acrylate group. These results suggest that in FCP, the decrease in pH on the lumenal side under high-light conditions leads to protonation of Chlc and thereby a red shift in the absorption wavelength.

Introduction

Chlorophylls (Chls) are responsible for light absorption, energy transfer, and electron transfer in photosynthetic proteins.1 In brown algae and diatoms, Chlcs (Chlc1, Chlc2, and Chlc3) are widely distributed,2 which have an acrylate moiety (–CH=CH–COOH/COO–) conjugated to the porphyrin ring (Figure 1a).3

Figure 1.

Chlc. (a) Chemical structure of Chlc. Red and blue arrows indicate the orientations of the transition dipole moments along the x- and y-axes, respectively. The chemical group R7 is CH3, CH3, and COOCH3 for Chlc1, Chlc2, and Chlc3, respectively. The chemical group R8 is CH2CH3, CH=CH2, and CH=CH2 for Chlc1, Chlc2, and Chlc3, respectively. The acrylate moiety at the 17 position is a protonation site (–CH=CH–COOH/–COO–). (b) Crystal structure near the two Chlc molecules in FCP (PDB ID: 6A2W(4)). Dotted lines indicate H-bonds. The values indicate distances in Å. FX indicates fucoxanthin. (c) Contributions of HOMO, HOMO–1, LUMO, and LOMO+1 to the Bx, By, Qx, and Qy absorption bands (i.e., the four-orbital model14).

Chlcs are embedded in light-harvesting antenna proteins, fucoxanthin and chlorophyll a/c-binding proteins (FCPs).1,4 The FCP from the pennate diatom, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, contains seven Chla, one Chlc1, one Chlc2, and seven fucoxanthin chromophores in each monomer subunit (Figure 1b).4 FCP belongs to the superfamily of transmembrane light-harvesting complex (LHC) proteins with low sequence similarity to the main LHCI and LHCII subunits of green lineage organisms,5,6 although Chlcs in FCP are replaced with Chla or Chlb in LHCI and LHCII.4,7 The number of fucoxanthin molecules is larger in FCP (five to seven in each monomer4,8) than that of carotenoid molecules in LHCI and LHCII (three or four in each monomer subunit4,9). Chlcs and fucoxanthin molecules in FCP are likely to contribute to the difference in absorption and dissipation features between FCP and LHCI/LHCII. Chlc and fucoxanthin provide an orange-brown color to FCP in diatoms, allowing them to absorb light in the blue-green region.5 In contrast, Chla and Chlb weakly absorb in this region (“green gap”).3 Therefore, diatoms with FCP can effectively use blue-green light, which penetrates deeper into water, whereas green lineage photosynthetic organisms with LHCI and LHCII only weakly use it.5,10 Due to the constant water circulation in the ocean’s surface layer, diatoms are exposed to rapidly changing, high and low light conditions.10,11 To protect against strong light exposure, diatoms have a nonphotochemical quenching (photoprotection) system, in which the excess absorbed energy is dissipated into heat.12 Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy studies showed that FCP exhibits rapid energy-quenching components under excess light conditions.13

The absorption spectrum of Chl is characterized by two main bands, the Soret (B) band (∼400 nm) and the Q band (∼600–800 nm).3 In Chlc, the Soret transition is stronger than the Q transition with an absorption strength ratio of Soret/Q ≃ 10/13. The observed Soret band is a superposition of the Bx and By bands. The four-orbital model can qualitatively explain the origin of the Bx and By bands, wherein the two highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMOs) and two lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMOs) are involved (Figure 1c).14 In the porphyrin ring, the transitions from the HOMO to the LUMO and from the HOMO–1 to the LUMO+1 have a transition dipole moment along the x-axis, whereas the transitions from the HOMO–1 to the LUMO and from the HOMO to the LUMO+1 have a transition dipole moment along the y-axis owing to the symmetry of wavefunctions (Figure 1c). The Bx and By transitions can be expressed by linear combinations of the two transitions having a transition dipole moment along the x- and y-axes, respectively (Figure 1c). The Qx and Qy transitions in the Q band can also be expressed by linear combinations of the two transitions having a transition dipole moment along the x- and y-axes, respectively (Figure 1c).

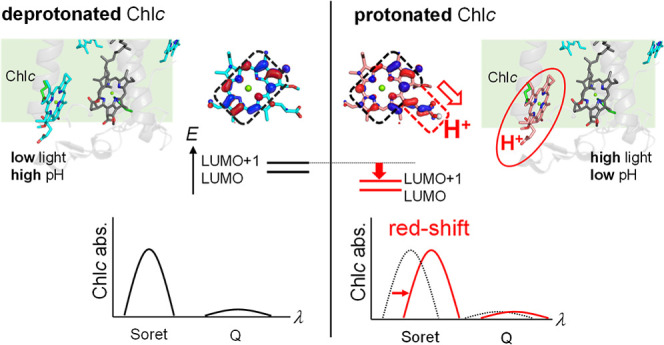

Chlc is the only Chl that has a protonation site (–CH=CH–COOH/COO–). The absorption wavelength of the titratable chromophore often depends on its protonation state. Phenolphthalein exhibits a blue-shift in the absorption wavelength upon protonation and thus it can be used as a pH indicator.15 Deprotonation of phenolphthalein leads to the extension of π-conjugation owing to structural changes, causing the molecule to absorb light in the visible region15 (Figure 2a). The corresponding changes are also observed in p-coumaric acid in photoactive yellow protein (PYP)16 and retinal Schiff base in microbial rhodopsins.17 As p-coumaric acid and retinal Schiff base protonate, their absorption wavelengths change due to the electrostatic interaction of the proton with the molecular orbitals involved in the excitation (i.e., HOMO and LUMO). In PYP, the HOMO of p-coumaric acid is located at the protonatable hydroxyl group. The absorption wavelength of p-coumaric acid decreases by ∼100 nm16 in response to the protonation as the HOMO is stabilized by the electrostatic attractive interaction between an electron on the HOMO and the migrated proton17 (Figure 2b). The stabilization of the HOMO is associated with changes in single/double bond character, that is, the bond alternation effect in the π-conjugated system of p-coumaric acid in response to the protonation.18 In contrast, in microbial rhodopsins, the LUMO of retinal Schiff base is located at the protonatable Schiff base. The absorption wavelength of retinal Schiff base increases by ∼100 nm19 in response to the protonation as the LUMO is stabilized by the electrostatic attractive interaction between an electron on the LUMO and the migrated proton.17

Figure 2.

Mechanism of color tuning depending on the protonation state of the chromophore: (a) phenolphthalein; (b) p-coumaric acid in PYP. Orange regions indicate π conjugated systems. Red and blue ovals represent the HOMO.

In contrast to phenolphthalein, the structure of Chlc is not substantially affected by the protonation state of the acrylate moiety. In addition, four molecular orbitals, which are delocalized over the porphyrin ring, are related to the Soret and Q transitions of Chlc (Figure 1c). As these orbitals are not localized on the protonation site (acrylate moiety), their electrostatic interactions with the proton are likely equal. These suggest that the absorption wavelength of Chlc should not depend on the protonation state of the acrylate moiety.

However, spectroscopic measurements showed that the Soret absorption band of Chlc in FCP differs at pH: two peaks at 471 and 446 nm were observed at low (e.g., pH = 4.6) and high (e.g., pH = 8.0) pH, respectively, and the pKa was determined to be 5.320 The absorption wavelength shift is probably due to protonation (–CH=CH–COOH) and deprotonation (–CH=CH–COO–) of the acrylate moiety.20 The pH value of the lumenal side of the thylakoid membrane in chloroplasts decreases to 5.2–6.0 under high-light conditions.21 The protonation of Chlc at low pH might play a role in the energy dissipation in the FCP photoprotection system. In this study, we investigate the mechanism by which the absorption wavelength of Chlc changes owing to the change in the protonation state of the acrylate moiety using a quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) approach.

Methods

Coordinates and Atomic Partial Charges

The atomic coordinates of FCP were obtained from the X-ray structure from Phaeodactylum tricornutum (PDB ID: 6A2W(4)). During the optimization of the hydrogen atom positions with the CHARMM all-atom force field,22 the positions of all heavy atoms were fixed. The titratable groups were maintained in their standard protonation states (i.e., acidic groups were deprotonated and basic groups were protonated). The atomic partial charges of the amino acids were obtained from the CHARMM2223 parameter set.

Protonation Pattern

The protonation pattern was determined based on the electrostatic continuum model, solving the linear Poisson–Boltzmann equation using the MEAD program.24 The difference in electrostatic energy between the two protonation states (i.e., protonated and deprotonated states) in a reference model system was calculated using a known experimentally measured pKa value (e.g., 4.0 for Asp25). Accordingly, the difference between the pKa values of the protein and the reference system was added to the known reference pKa value. The experimentally measured pKa values employed as references were 12.0 for Arg, 4.0 for Asp, 9.5 for Cys, 4.4 for Glu, 10.4 for Lys, 9.6 for Tyr,25 and 7.0 and 6.6 for the Nε and Nδ atoms of His, respectively.26 All other titratable sites were fully equilibrated to the protonation state of the target site during titration. The dielectric constants were set to 4 inside the protein and 80 for water. All computations were performed at 300 K and pH 7.0 with an ionic strength of 100 mM. The linear Poisson–Boltzmann equation was solved using a three-step grid-focusing procedure at resolutions of 2.5, 1.0, and 0.3 Å. The ensemble of protonation patterns was sampled using the Monte Carlo (MC) method with the Karlsberg program.27 The MC sampling yielded the probabilities of the two protonation states (protonated and deprotonated states) of the molecule.

QM/MM Calculations

The geometry was optimized using a QM/MM approach. The restricted density functional theory (DFT) method was employed with the B3LYP functional and LACVP* basis set using the QSite28 program. The QM region was defined as the Chlc molecule (Chlc1 or Chlc2) and the side chain of the residue that served as the ligand of Chlc (Gln143 or His39). All atomic coordinates were fully relaxed in the QM region. The protonation pattern of the titratable residues was implemented in the atomic partial charges of the corresponding MM region. In the MM region, the positions of the H atoms, water molecule near Chlc1 (H2O-510), and basic residue near Chlcs (Lys136 or Arg31) were optimized using the OPLS2005 force field,29 whereas the positions of the other atoms were fixed. See the Supporting Information for the atomic coordinates of the optimized geometries.

Using the optimized geometries, the excitation energies, transition oscillator strengths for 10 excited states, and energy levels of the molecular orbitals of Chlc1 and Chlc2 in the FCP environment were calculated with time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) method. The CAM-B3LYP functional30 and 6-31G* basis set were employed in the GAMESS program.31 The CAM-B3LYP-related parameter μ was set to 0.14.32 A QM/MM approach using the polarizable continuum model (PCM) method with a dielectric constant of 78 for the bulk region was employed. In this region, the electrostatic and steric effects created by the protein environment were explicitly considered in the presence of bulk water. In the PCM method, the polarization points were placed on the spheres with a radius of 2.8 Å from the center of each atom to describe possible water molecules in the cavity.

In this study, different functionals and basis sets were employed between the geometry optimization (B3LYP/LACVP*) and the excitation energy calculation (CAM-B3LYP/6-31G*), as done in previous theoretical studies on Chls.33 Note that the calculated excitation energy did not change essentially when the same functional and basis set were employed in the geometry optimization and excitation energy calculations (CAM-B3LYP/6-31G*) (Figure S1).

To determine the maximum excitation energy, we constituted an absorption spectrum f(E) as a summation of the individual absorption spectra gn(E) for each excitation state with inhomogeneous broadening, described by the Gaussian function:

| 1 |

| 2 |

where E is the light energy, f0n is the oscillator strength of the n-th excited state, En is the excitation energy of the n-th excited state, and c is the standard deviation (0.1 eV). When f(E) reaches its maximum value, it is considered as the absorption energy.

The contribution of the solvation effect of the FCP environment to the absorption energy of Chlc (ΔEtotal) was obtained as the difference in the calculated absorption energy between the FCP environment and vacuum. ΔEtotal was divided into two components: contributions of protein atomic charges (ΔEprotein) and bulk water (ΔEwater). ΔEprotein was obtained as the shift in the calculated absorption energy upon removing the atomic charges in the MM region. ΔEwater was obtained as the difference between ΔEtotal and ΔEprotein (ΔEwater = ΔEtotal – ΔEprotein).

Results

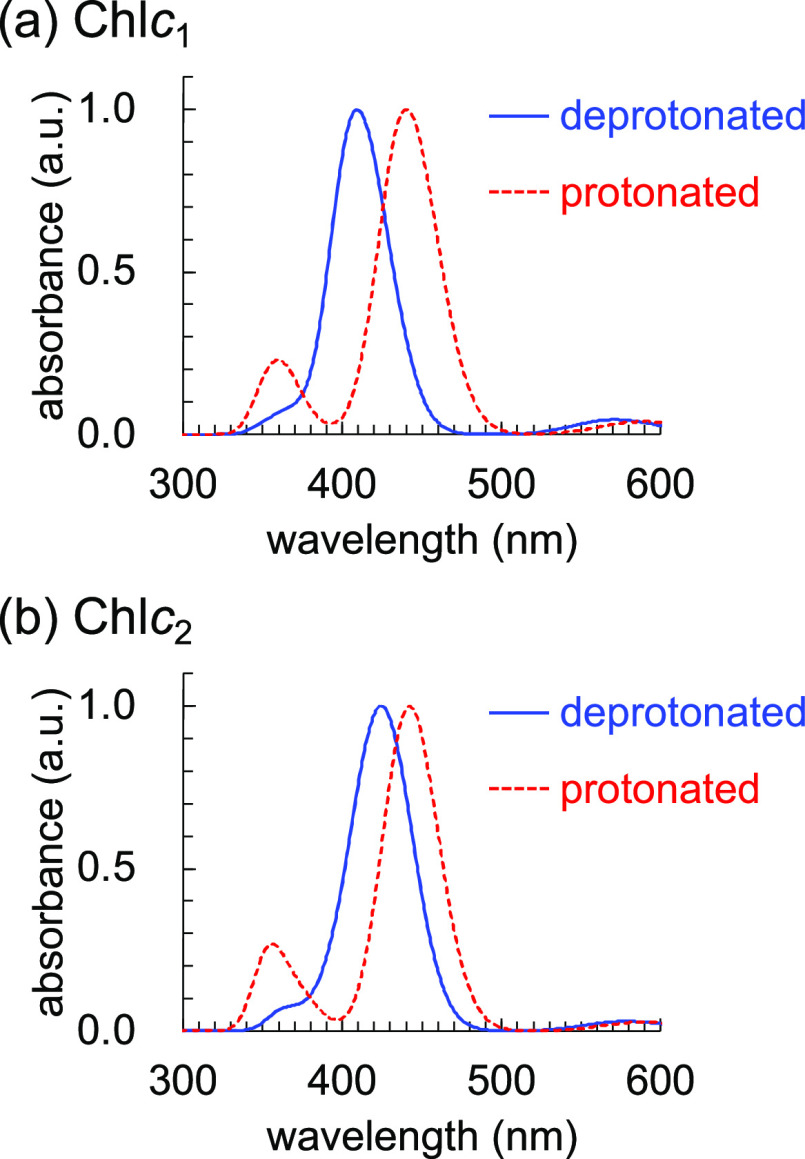

The optimized geometry shows that salt bridges form between the acrylate moiety of Chlc1 and Lys136 and between the acrylate moiety of Chlc2 and Arg31, when Chlc1 and Chlc2 are deprotonated (Figure 3 left). On the other hand, these salt bridges are lost when Chlc1 and Chlc2 are protonated (Figure 3 right). The calculated absorption wavelength of protonated Chlc1 is 31 nm longer than that of deprotonated Chlc1 in FCP (Figure 4a). Similarly, the calculated absorption wavelength of protonated Chlc2 is 18 nm longer than that of deprotonated Chlc2 in FCP (Figure 4b). These results are consistent with the observed pH-dependent change (25 nm) in the Soret absorption band of Chlc in FCP, that is, 471 nm at pH 4.6 and 446 nm at pH 8.0.20 The Q absorption band is also red-shifted upon the protonation of Chlc (Figure S2), although the intensity of the Q band is smaller than that of the Soret band. Notably, an increase in the calculated absorption wavelength upon the protonation of Chlc is also observed in the absence of the FCP environment (in vacuum and water; Figure S3). Thus, the absorption wavelength shift of Chlc predominantly originates from the change in the protonation state of the acrylate moiety instead of the protein environment (e.g., the presence or absence of the salt bridge).

Figure 3.

QM/MM-optimized structures of FCP: (a) with deprotonated and protonated Chlc1; (b) with deprotonated and protonated Chlc2. Values indicate distances in Å. The proton at the acrylate moiety is shown as a white sphere. FX indicates fucoxanthin.

Figure 4.

Calculated absorption spectra of Chlcs. Absorption spectra of deprotonated (solid blue lines) and protonated (dotted red lines) forms of (a) Chlc1 and (b) Chlc2 in the FCP environment.

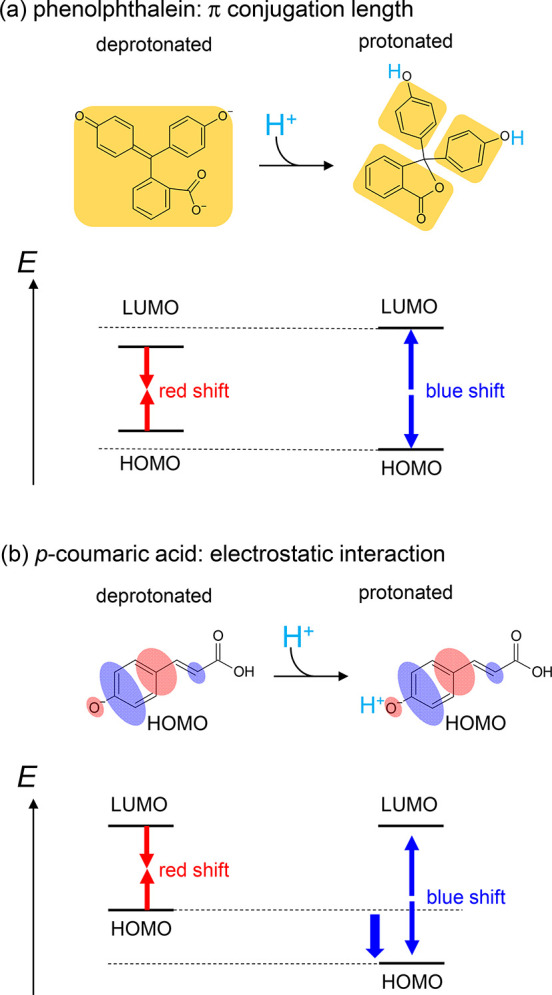

The transitions between two HOMOs (HOMO and HOMO–1) and two LUMOs (LUMO and LUMO+1) contribute to the Soret absorption band of Chlc (Figure 1c).14 These molecular orbitals are stabilized by the protonated acrylate group of Chlc owing to the positive charge of the proton (Figures 5 and S4). Distribution patterns in the HOMO and the HOMO–1 are negligibly affected by the protonation. In contrast, the LUMO and the LUMO+1 are delocalized over the Chlc molecule, especially toward the acrylate moiety, when Chlc is protonated (Figure 5). Therefore, protonation of the acrylate moiety stabilizes the LUMO and the LUMO+1 more largely than the HOMO and the HOMO–1. Thus, the energy differences between the HOMOs and the LUMOs decrease as Chlc protonates, leading to an increase in the absorption wavelength (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of the shift in the absorption energy owing to the protonation of the acrylate moiety. The proton at the acrylate moiety is shown as a white sphere in protonated Chlc. Numerical values of the molecular-orbital energies are not shown for clarity (see Figure S4 for the energy values).

The acrlylate moiety is conjugated to the porphyrin ring of Chlc (Figure 1a). The protonation stabilizes the molecular orbitals of the acrylate moiety ([MO]acrylate) more significantly than those of the porphyrin moiety ([MO]porphyrin) (Figure 6). In deprotonated Chlc, the unoccupied molecular orbitals of the acrylate moiety (e.g., [LUMO]acrylate) are not mixed with the LUMO and the LUMO+1 of porphyrin ([LUMO]porphyrin and [LUMO+1]porphyrin) due to the large energy gap between [LUMO]porphyrin/[LUMO+1]porphyrin and the unstable [LUMO]acrylate (Figure 6a). The protonation of the acrylate moiety stablizes [LUMO]acrylate to the levels of [LUMO]porphyrin and [LUMO+1]porphyrin (Figure 6b). Thus, [LUMO]acrylate is mixed with [LUMO]porphyrin and [LUMO+1]porphyrin to form delocalized [LUMO]Chlc and [LUMO+1]Chlc, as the acrylate moiety protonates (Figures 6b and S5), leading to the stabilization of [LUMO]Chlc and [LUMO+1]Chlc (Figure 5). Thus, the protonation of Chlc increases the absorption wavelengths in the Soret and Q bands.

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of the delocalization of the LUMO and the LUMO+1 toward the acrylate moiety in protonated Chlc. Energy diagrams for molecular orbitals in (a) deprotonated and (b) protonated Chlcs. Numerical values of the molecular-orbital energies are not shown for clarity (see Figure S5 for the energy values). The energy levels of molecular orbitals on porphyrin and acrylate moieties are conceptual references for clarity (not based on calculations).

The electrostatic environment of FCP contributes to an increase in the absorption wavelength of Chlc (Table 1 and Figure S6). The solvation of FCP stabilizes the molecular orbitals of the polar acrylate moiety ([MO]acrylate) more significantly than those of the hydrophobic porphyrin moiety ([MO]porphyrin) (e.g., [HOMO]acrylate; Figure S7). Therefore, the mixture of [LUMO]acrylate and [LUMO]porphyrin (i.e., the delocalization of [LUMO]Chlc toward the acrylate moiety, Figure 6b) is pronounced in the FCP environment (Figure S7c). Thus, [LUMO]Chlc is stabilized more significantly than [HOMO]Chlc and [HOMO–1]Chlc owing to the FCP environment, leading to an increase in the absorption wavelength (Table 1 and Figure S7).

Table 1. Contributions of Solvation to the Absorption Energies of Protonated Chlc1 and Chlc2 in FCP (in meV).

| Chlc1 | Chlc2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| protein | all components | –73 (≈11 nm) | –46 (≈7 nm) |

| Lys136 | –48 (≈7 nm) | – | |

| fucoxanthin307 | –18 (≈3 nm) | – | |

| Arg31a | – | –1 (≈0 nm) | |

| fucoxanthin306 | – | –11(≈2 nm) | |

| bulk water | –73 (≈11 nm) | –84 (≈13 nm) | |

| total | –147 (≈22 nm) | –130 (≈20 nm) |

Discussion

Retinal Schiff base in microbial rhodopsin and p-coumaric acid in PYP have protonation sites and show changes in absorption wavelength depending on the protonation state. Indeed, the absorption wavelength of retinal Schiff base in the protein environment increases by ∼100 nm as it protonates.19 In contrast, the absorption wavelength of the p-coumaric acid in the protein environment decreases by ∼100 nm as it protonates.16

The excitation from the HOMO to the LUMO is the main characteristic of the first excited state in retinal Schiff base and p-coumaric acid.18,34 In the retinal Schiff base, the LUMO is localized on the protonation site (imine group) (Figure 7a).34 As the proton approaches the Schiff base moiety, the LUMO is stabilized more significantly than the HOMO, leading to a decrease in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap (Figure 7a).17 In the p-coumaric acid, the HOMO is localized on the protonation site (hydroxyl group) (Figure 7b). As the proton approaches the hydroxyl group moiety, the HOMO is stabilized more significantly than the LUMO, leading to an increase in the HOMO–LUMO energy gap (Figure 7b).17

Figure 7.

Schematic illustration of changes in the absorption energy upon protonation: (a) retinal Schiff base in microbial rhodopsins; (b) p-coumaric acid in PYP; (c) Chlc in FCP.

The color-tuning mechanism in Chlc in FCP is different from those in retinal Schiff base in microbial rhosopsins and p-coumaric acid in PYP: the absorption wavelength is predominantly affected by localization/delocalization of the LUMO and the LUMO+1 depending on the protonation state of the acrylate moiety (Figure 7c). In contrast to the energy levels of the molecular orbitals delocalized over the porphyrin ring, those of the acrylate moiety are sensitive to the presence/absence of the proton. The energy level of [LUMO]acrylate is lowered to those of [LUMO]porphyrin and [LUMO+1]porphyrin only when the acrylate moiety is protonated (Figure 6). Thus, the LUMO and the LUMO+1 are delocalized toward the acrylate moiety only when the acrylate moiety is protonated, leading to stabilizations of the LUMO and the LUMO+1 and an increase in the absorption wavelength (Figure 7c).

Although Chlcs are located only on the stromal side in the FCP crystal structure from Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Figure 1b),4 cryo-electron microscopic analysis showed that Chlcs are also located on the lumenal side of the photosystem II–FCP (PSII–FCP) complex structure from the diatom Chaetoceros gracilis(8) (Figure 8). In photosynthesis, protons are released toward the lumenal side of the thylakoid membrane of chloroplasts, and the pH values on the lumenal side decrease as the reaction proceeds. Thus, the pH value on the lumenal side varies between ∼5 and ∼8 depending on the light intensity of the environment.21,35 Under normal low-light conditions, the lumenal Chlc is deprotonated at high pH (e.g., ∼8) (Figure 8a). In contrast, under high-light conditions, the pH value on the lumenal side decreases (e.g., to ∼5), and the lumenal Chlc can be protonated, causing a red shift in the absorption wavelength of Chlc in the blue-green light region (e.g., 471 nm20) (Figure 8b). This absorption wavelength shift of Chlc may affect efficiency of energy transfers and play a role in the photoprotection system of FCP in diatoms.

Figure 8.

Absorption wavelength shift and light intensity: (a) low-light condition—Chlc is deprotonated at high pH; (b) high-light condition—Chlc is protonated at low pH, and the Soret and Q bands of Chlc are red-shifted. The cofactor arrangement of the PSII–FCP complex structure is shown.8 Note that Chlc1-303 and -309 in the PSII–FCP complex structure correspond to Chlc1 and Chlc2 in the isolated FCP crystal structure,4 respectively.

Conclusions

The calculated absorption wavelength of protonated Chlc is ∼20–30 nm longer than that of deprotonated Chlc irrespective of the presence or absence of the FCP environment (Figures 4 and S3), which is consistent with the observed pH-dependent change (i.e., 25 nm) in the Soret absorption band of Chlc in FCP.20 The absorption wavelength shift of Chlc predominantly originates from the change in the protonation state of the acrylate moiety instead of the protein environment (e.g., the presence or absence of a salt bridge). The LUMO and the LUMO+1 are stabilized more significantly than the HOMO and the HOMO–1 by the protonated acrylate moiety owing to the delocalization of the LUMO and the LUMO+1 toward the acrylate moiety (Figure 5). The delocalization of the LUMO and the LUMO+1 occurs as Chlc protonates. This is because the energy level of [LUMO]acrylate is lowered to the energy levels of [LUMO]porphyrin and [LUMO+1]porphyrin by the protonated acrylate moiety (Figure 6). The delocalization and stabilization of the LUMO and the consequent increase in the absorption wavelength are pronounced in the solvation of FCP (Table 1 and Figure S7).

In FCP, the size of the LUMO and the LUMO+1 of Chlc is extended toward the acrylate moiety upon protonation. This is the origin of the absorption wavelength shift of Chlc. In contrast, in p-coumaric acid in PYP and retinal Schiff base in microbial rhodopsins, the size of the molecular orbitals does not change upon protonation. The absorption wavelength shifts of p-coumaric acid and retinal Schiff base originate from electrostatic interactions between electrons and the migrated proton (Figure 7).

The absorption wavelength of Chlc differs at pH on the thylakoid lumenal side of FCP. Under high-light conditions, the low pH environment facilitates the protonation of Chlc, which induces a red shift in the absorption wavelength (Figure 8).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by JST CREST (JPMJCR1656 to H.I.), JSPS KAKENHI (JP18H05155, JP18H01937, JP20H03217, and JP20H05090 to H.I.; JP16H06560 and JP18H01186 to K.S. and JP22J22246 to M.T.), and the Interdisciplinary Computational Science Program in CCS, University of Tsukuba.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcb.2c07232.

Absorption spectra of Chlcs in FCP calculated using different functionals and basis sets; Soret and Q bands in the calculated absorption spectra of deprotonated and protonated Chlc1 and Chlc2 in FCP; calculated absorption spectra of Chlcs in the absence of the FCP environment; changes in the energy levels of four molecular orbitals, LUMO+1, LUMO, HOMO, and HOMO–1, upon protonation of the acrylate moiety in FCP; molecular orbitals in deprotonated and protonated Chlc1; calculated absorption spectra of Chlcs in different solvents; and contribution of the FCP environment to the energy levels of the molecular orbitals in protonated Chlc (PDF)

QM/MM-optimized geometries (TXT)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kuczynska P.; Jemiola-Rzeminska M.; Strzalka K. Photosynthetic pigments in diatoms. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5847–5881. 10.3390/md13095847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchel C. Light harvesting complexes in chlorophyll c-containing algae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2020, 1861, 148027. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M.; Lindsey J. S. Absorption and fluorescence spectral database of chlorophylls and analogues. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 136–165. 10.1111/php.13319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Yu L. J.; Xu C.; Tomizaki T.; Zhao S.; Umena Y.; Chen X.; Qin X.; Xin Y.; Suga M.; et al. Structural basis for blue-green light harvesting and energy dissipation in diatoms. Science 2019, 363, eaav0365 10.1126/science.aav0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchel C. Evolution and function of light harvesting proteins. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 172, 62–75. 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durnford D. G.; Aebersold R.; Green B. R. The fucoxanthin-chlorophyll proteins from a chromophyte alga are part of a large multigene family: structural and evolutionary relationships to other light harvesting antennae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1996, 253, 377–386. 10.1007/s004380050334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Zhao S.; Pi X.; Kuang T.; Sui S. F.; Shen J. R. Structural features of the diatom photosystem II-light-harvesting antenna complex. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 2191–2200. 10.1111/febs.15183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao R.; Kato K.; Kumazawa M.; Ifuku K.; Yokono M.; Suzuki T.; Dohmae N.; Akita F.; Akimoto S.; Miyazaki N.; et al. Structural basis for different types of hetero-tetrameric light-harvesting complexes in a diatom PSII–FCPII supercomplex. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1764. 10.1038/s41467-022-29294-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mazor Y.; Borovikova A.; Caspy I.; Nelson N. Structure of the plant photosystem I supercomplex at 2.6 Å resolution. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17014. 10.1038/nplants.2017.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang J.; Yu L. J.; Wang W.; Yan Q.; Kuang T.; Qin X.; Shen J. R. Structure of plant photosystem I-light harvesting complex I supercomplex at 2.4 Å resolution. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 1367–1381. 10.1111/jipb.13095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liu Z.; Yan H.; Wang K.; Kuang T.; Zhang J.; Gui L.; An X.; Chang W. Crystal structure of spinach major light-harvesting complex at 2.72 Å resolution. Nature 2004, 428, 287–292. 10.1038/nature02373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Standfuss J.; Terwisscha van Scheltinga A. C.; Lamborghini M.; Kühlbrandt W. Mechanisms of photoprotection and nonphotochemical quenching in pea light-harvesting complex at 2.5 Å resolution. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 919–928. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannakis E.; H.M. van Stokkum I.; Fey H.; Büchel C.; van Grondelle R. Spectroscopic characterization of the excitation energy transfer in the fucoxanthin-chlorophyll protein of diatoms. Photosynth. Res. 2005, 86, 241–250. 10.1007/s11120-005-1003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks A.; Schaven K.; Bruce D. Diverse mechanisms for photoprotection in photosynthesis. Dynamic regulation of photosystem II excitation in response to rapid environmental change. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1847, 468–485. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss R.; Lepetit B. Biodiversity of NPQ. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 172, 13–32. 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao R.; Yokono M.; Ueno Y.; Suzuki T.; Kumazawa M.; Kato K. H.; Tsuboshita N.; Dohmae N.; Ifuku K.; Shen J. R.; et al. Enhancement of excitation-energy quenching in fucoxanthin chlorophyll a/c-binding proteins isolated from a diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum upon excess-light illumination. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2021, 1862, 148350. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Gouterman M. Spectra of porphyrins. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1961, 6, 138–163. 10.1016/0022-2852(61)90236-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Weiss C. The Pi electron structure and absorption spectra of chlorophylls in solution. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1972, 44, 37–80. 10.1016/0022-2852(72)90192-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W.; Ma H. Spectroscopic probes with changeable π-conjugated systems. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 8732–8744. 10.1039/c2cc33366j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff W. D.; van Stokkum I. H.; van Ramesdonk H. J.; van Brederode M. E.; Brouwer A. M.; Fitch J. C.; Meyer T. E.; van Grondelle R.; Hellingwerf K. J. Measurement and global analysis of the absorbance changes in the photocycle of the photoactive yellow protein from Ectothiorhodospira halophila. Biophys. J. 1994, 67, 1691–1705. 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80643-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimura M.; Tamura H.; Saito K.; Ishikita H. Absorption wavelength along chromophore low-barrier hydrogen bonds. iScience 2022, 25, 104247. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergi A.; Grüning M.; Ferrario M.; Buda F. Density functional study of the photoactive yellow protein’s chromophore. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 4386–4391. 10.1021/jp002270+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst O. P.; Lodowski D. T.; Elstner M.; Hegemann P.; Brown L. S.; Kandori H. Microbial and animal rhodopsins: structures, functions, and molecular mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 126–163. 10.1021/cr4003769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano N.; Mizoguchi T.; Fujii R. The pH-dependent photophysical properties of chlorophyll-c bound to the light-harvesting complex from a diatom, Chaetoceros calcitrans. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2018, 358, 379–385. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2017.09.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B. Carotenoids and photoprotection in plants - a role for the xanthophyll zeaxanthin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1990, 1020, 1–24. 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90088-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks B. R.; Bruccoleri R. E.; Olafson B. D.; States D. J.; Swaminathan S.; Karplus M. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 1983, 4, 187–217. 10.1002/jcc.540040211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKerell A. D.; Bashford D.; Bellott M.; Dunbrack R. L.; Evanseck J. D.; Field M. J.; Fischer S.; Gao J.; Guo H.; Ha S.; et al. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3586–3616. 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashford D.; Karplus M. pKa’s of ionizable groups in proteins: atomic detail from a continuum electrostatic model. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 10219–10225. 10.1021/bi00496a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki Y.; Tanford C. Acid-base titrations in concentrated guanidine hydrochloride. Dissociation constants of the guanidinium ion and of some amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 736–742. 10.1021/ja00980a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tanokura M. 1H nuclear magnetic resonance titration curves and microenvironments of aromatic residues in bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A. J. Biochem. 1983, 94, 51–61. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tanokura M. 1H-NMR study on the tautomerism of the imidazole ring of histidine residues: I. Microscopic pK values and molar ratios of tautomers in histidine-containing peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1983, 742, 576–585. 10.1016/0167-4838(83)90276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tanokura M. 1H-NMR study on the tautomerism of the imidazole ring of histidine residues: II. Microenvironments of histidine-12 and histidine-119 of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1983, 742, 586–596. 10.1016/0167-4838(83)90277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabenstein B.; Knapp E.-W. Calculated pH-dependent population and protonation of carbon-monoxy-myoglobin conformers. Biophys. J. 2001, 80, 1141–1150. 10.1016/s0006-3495(01)76091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSite. Version 5.8; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2012.; b Murphy R. B.; Philipp D. M.; Friesner R. A. A mixed quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) method for large-scale modeling of chemistry in protein environments. J. Comput. Chem. 2000, 21, 1442–1457. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Philipp D. M.; Friesner R. A. Mixed ab initio QM/MM modeling using frozen orbitals and tests with alanine dipeptide and tetrapeptide. J. Comput. Chem. 1999, 20, 1468–1494. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L.; Maxwell D. S.; Tirado-Rives J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225–11236. 10.1021/ja9621760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai T.; Tew D. P.; Handy N. C. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. 10.1016/j.cplett.2004.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. W.; Baldridge K. K.; Boatz J. A.; Elbert S. T.; Gordon M. S.; Jensen J. H.; Koseki S.; Matsunaga N.; Nguyen K. A.; Su S.; et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14, 1347–1363. 10.1002/jcc.540141112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K.; Suzuki T.; Ishikita H. Absorption-energy calculations of chlorophyll a and b with an explicit solvent model. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2018, 358, 422–431. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2017.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Saito K.; Mitsuhashi K.; Ishikita H. Dependence of the chlorophyll wavelength on the orientation of a charged group: Why does the accessory chlorophyll have a low site energy in photosystem II?. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2020, 402, 112799. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Tamura H.; Saito K.; Ishikita H. Acquirement of water-splitting ability and alteration of the charge-separation mechanism in photosynthetic reaction centers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 16373–16382. 10.1073/pnas.20008951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mitsuhashi K.; Tamura H.; Saito K.; Ishikita H. Nature of asymmetric electron transfer in the symmetric pathways of photosystem I. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 2879–2885. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c10885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K.; Hayashi S.; Hasegawa J.; Nakatsuji H. Theoretical studies on the color-tuning mechanism in retinal proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007, 3, 605–618. 10.1021/ct6002687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer D. M.; Sacksteder C. A.; Cruz J. A. How acidic is the lumen?. Photosynth. Res. 1999, 60, 151–163. 10.1023/A:1006212014787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.