Abstract

Aerosols are abundant on the Earth and likely played a role in prebiotic chemistry. Aerosol particles coagulate, divide, and sample a wide variety of conditions conducive to synthesis. While much work has centered on the generation of aerosols and their chemistry, little effort has been expended on their fate after settling. Here, using a laboratory model, we show that aqueous aerosols transform into cell-sized protocellular structures upon entry into aqueous solution containing lipid. Such processes provide for a heretofore unexplored pathway for the assembly of the building blocks of life from disparate geochemical regions within cell-like vesicles with a lipid bilayer in a manner that does not lead to dilution. The efficiency of aerosol to vesicle transformation is high with prebiotically plausible lipids, such as decanoic acid and decanol, that were previously shown to be capable of forming growing and dividing vesicles. The high transformation efficiency with 10-carbon lipids in landing solutions is consistent with the surface properties and dynamics of short-chain lipids. Similar processes may be operative today as fatty acids are common constituents of both contemporary aerosols and the sea. Our work highlights a new pathway that may have facilitated the emergence of the Earth’s first cells.

Keywords: prebiotic chemistry, origins of life, aerosols, vesicles, protocells

Introduction

Any rotating planet that contains a liquid ocean will generate atmospheric aerosols by wind action at the ocean surface.1−3 Aerosol particles are small (10–4 to 10 μm) and thus are capable of traveling long distances.4 Smaller aerosols coagulate into larger particles that then settle according to the planet’s gravity and atmospheric density.5 On the Earth, this results in a typical particle size of a few microns in diameter,4 a size similar to that of a single bacterium.5 Since organic species preferentially partition to the water surface,1,2,6−8 aqueous marine aerosols can be described as saline solutions encapsulated within an organic film. These films possess fatty acids, such as palmitic, stearic, and oleic acid, and 14–32 carbon fatty alcohols for contemporary aqueous aerosols.9−14 The source of these lipids is the breakdown of biological material; however, shorter-chain versions of these same molecules are prebiotically plausible and, consequently, are likely to have partitioned similarly to interfaces before the emergence of the Earth’s first cells. While in the atmosphere, aerosols sample different temperatures, humidities, and radiation fields, which may alter the chemical composition of the particle. Although much work has centered on the generation and composition of aerosols, little has been geared toward investigating their fate upon landing.

Aerosols could have provided a crucial link between the prebiotic synthesis of biopolymers and the emergence of a protocell, i.e., a growing–dividing lipid compartment containing a replicating genome.15 Aerosols are products of physical–chemical processes at the surface of the Earth, and chemistry at or near the surface of the early Earth has been frequently invoked as a setting for the emergence of the Earth’s first cells. For example, conditions meant to mimic surface environments support the synthesis of all of the major building blocks of life, including amino acids, nucleotides, and lipids.16 However, despite shared chemistry, the synthesis of the full suite of building blocks requires several different conditions, suggesting that multiple, compositionally distinct bodies of water were necessary to provide all of the needed components of a protocell. If true, then mechanisms were necessary to bring the building blocks together. One possibility is that the components of the protocell17,18 were brought together by streams that connected different bodies of water.19 Here, we explore whether aqueous aerosols could have provided an additional mechanism for the mixing of material and the formation of protocells.20

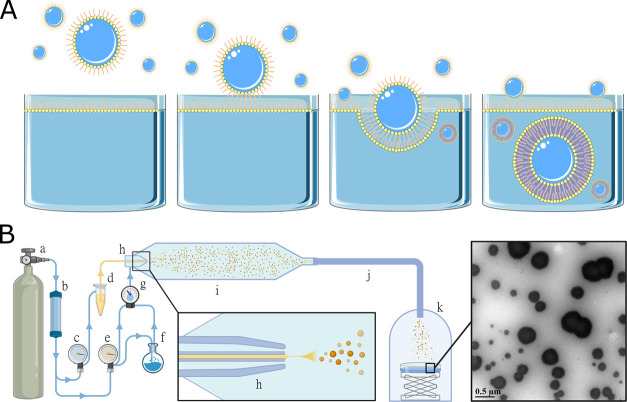

One key, unexplored advantage of aerosols is their potential ability to transform into vesicles upon landing.5 If aerosols were capable of becoming vesicles, then the collection of the building blocks of life from distinct bodies of water could be directly coupled to the formation of cell-sized compartments lined with a lipid bilayer. Since lipids were likely abundant on the early Earth21−23 and in the solar system,24,25 prebiotic lipids were likely present at air–water interfaces. As previously described by Dobson et al.,5 aerosols generated from such bodies of water would have contained what would later become the inner leaflet of a bilayer membrane (Figure 1A). Re-entry into aqueous environments that possessed lipid at the air–water interface would provide the outer leaflet, resulting in cell-sized vesicle compartments capable of housing a protocell. Here, we directly test whether aerosols can transform into vesicles through a mechanism conceptually similar to what has been described for the conversion of water-in-oil droplets to vesicles.26 We find that aqueous aerosols efficiently transform into vesicles upon landing into solutions containing lipids. Considering the high probability of aerosols on the prebiotic Earth and the importance of aerosols to our contemporary environment, our work uncovers previously unexplored contributors to the environment of our planet.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of aerosol to vesicle transformation. (B) Experimental apparatus and workflow. Compressed N2 gas (a) was fed through a drying column (b) to a pressure regulator (c) connected to a reservoir of spray solution (d). Simultaneously, the dry gas fed two mass flow controllers (e) used to regulate the relative humidity of the downstream carrier gas with a water bubbler (f) and a humidity sensor (g). The spray solution and the carrier gas met at the nozzle of a concentric borosilicate glass nebulizer (h). The generated aerosols passed through a flow tube (i) which removed larger droplets due to gravitational settling. The aerosols were conveyed by polyurethane antistatic tubing (j) to a collection chamber (k) containing the landing solution. A transmission electron microscopy (TEM) photograph showing aerosols transformed into vesicles. The spray and landing solutions were 20 mM 2:1 oleic acid/octadecenol with 10 mg·mL–1 ferritin, and 20 mM 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol, respectively. Panel (A) used modified templates from Servier Medical Art, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. Panel (B) was made with BioRender.

Material and Methods

Throughout the work described here, no unexpected or unusually high safety hazards were encountered. Risks and hazards linked to the inhalation of aerosols were mitigated by placing the experimental setup inside a chemical fume hood.

Chemicals

Fatty acids and fatty alcohols were purchased from Nu-Check Prep., Inc. Alexa Fluor 647 hydrazide was from Thermo Fisher Scientific. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All solutions were prepared in ultrapure, deionized water (Synergy Water Purification System, Merck) and their pH adjusted with sodium hydroxide using an Orion Star A211 pH meter with pH and ATC probes from Thermo Scientific (Orion 8157BNUMD). Spray solutions were prepared by adding the desired amount of lipids to an aqueous solution of 10 mM 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (HPTS) and 0.2 M bicine, pH 8.0, unless indicated otherwise. Solutions were vortexed for 2 min and tumbled overnight at 20 rpm at room temperature. Landing solutions were prepared by adding fatty acids and fatty alcohols, at a ratio of 2:1, to a solution of 0.2 M bicine, pH 8.0. The final lipid concentration varied depending on the lipids used and was 0.5 mM for 9-hexadecenoic acid/9-palmitoleyl alcohol (or palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol), 1.0 mM for 9-tetradecenoic acid/9-myristoleyl alcohol (or myristoleic acid/tetradecenol), and 20 mM for decanoic acid/decanol, unless otherwise stated. To ensure homogeneity, solutions were vigorously stirred for 10 min before use. Solutions containing decanoic acid and/or decanol were initially heated to 65 °C to facilitate dissolution.

Experimental Apparatus

The experimental setup (Figure S1) was fed by industrial grade nitrogen gas cylinders from Linde. To ensure dryness and purity, N2 was run through a succession of gas purification columns containing Drierite and 5 Å molecular sieves. The flux of this dry N2 was regulated with pressure and flow controllers. The pressure controller (ElveFlow, OB1 MK3+ base fitted with a 2000 mbar channel) was used to feed the spray solution into the nebulizer through PTFE Teflon capillary tubing. Two flow controllers (Alicat Scientific, MC-Series Gas Mass Flow Controllers) were used in parallel to provide constant mass flow to the nebulizer. The two flow regulators were also used to control the relative humidity of the N2 gas by appending a bubbler filled with ultrapure water to one line. The line with the bubbler generated N2 of 100% relative humidity (RH) was then mixed with the line lacking a bubbler in different flow rate ratios to achieve the desired RH (Figure S2). Unless otherwise stated, the experiments were performed at 60% RH. The RH was continuously monitored throughout the experiments with a temperature and RH sensor from Omega (RH-USB series).

The borosilicate glass nebulizer was custom made by the Glass Shop of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Alberta and consisted of two concentric channels (Figure S3). The spray solution was run through the inner channel while the N2 gas was fed through the outer channel. Nebulization was achieved when the spray solution met the carrier N2 gas at the tip of the nebulizer with a local pressure of 30 psi and a velocity of 7 m·s–1. Nebulization took place inside of a glass flow tube, with an internal volume of 2.4 L. The flow tube allowed for laminar flow and selected against larger droplets. The aerosols were then conveyed through soft polyurethane antistatic tubing (TUS1065B, SMC Pneumatics) from the flow tube to a bell-shaped jar (collection chamber) with an internal volume of 16.5 L. The collection chamber contained a Pyrex Petri dish (diameter = 14 cm) that held the landing solution. The Petri dish was placed on a lab jack inside the collection chamber 10 cm away from the end of the tubing from which the aerosols were expelled. The N2 gas velocity at the air–water interface was 0.5 m·s–1, as measured with an Extech Instruments thermo-anemometer (45118 series). The collection chamber was passively vented through four orthogonal openings at the base of the collection chamber that allowed uncaptured aerosols to exit into the chemical fume hood. A 3D printed skirt was installed around the base of the collection chamber to avoid interference caused by the air flow of the fume hood.

Experimental Procedure

The setup was equilibrated with 3 SLPM of N2 at 60% RH. Then, 20 mL of the landing solution was poured into the landing reservoir, i.e., the Pyrex Petri dish, and incubated for 10 min before being placed inside the collection chamber, i.e., the bell-shaped jar. Next, 0.5 mL of the spray solution was injected into the nebulizer at a pressure of 60 mbar with the pressure controller. One minute after nebulization, the N2 flow within the setup was stopped. The landing reservoir was then taken out of the collection chamber for sampling. Three separate 0.5 mL aliquots were taken from different regions of the landing solution and combined in an Eppendorf tube. From that 1.5 mL sample, 0.5 mL was loaded on a size exclusion column (Sepharose 4B, 45–165 μm bead diameter, Sigma-Aldrich) that was pre-equilibrated with 0.2 M bicine, pH 8.0, supplemented with lipid above the critical aggregate concentration (CAC). Eluted fractions (300 μL) were collected with a Gilson FC 203B fraction collector into a 96-well plate (Thermo Scientific Nunclon Delta Surface). Due to their larger size, vesicles (containing HPTS) eluted faster than free HPTS. Fluorescence was recorded with a SpectraMax i3x plate reader from Molecular Devices with excitation and emission at 452 and 512 nm, respectively. Quantification of the encapsulated and free fluorophore was by peak integration, with Origin’s 2021 Peak Analyzer wizard and calculated as

where aerosol to vesicle transformation (AVT) was determined using Aencasulated dye and Afree dye that were chromatogram peak surface areas of encapsulated and free dye, respectively. All experiments were in triplicate. All glass components of the setup were thoroughly cleaned with ultrapure water, ethanol, and acetone before each experiment. Similarly, soft polyurethane tubes were flushed with ultrapure water and compressed air before each experiment.

Determination of Aerosol Size

Aerosol size was measured with an optical particle counter (11-D, GRIMM Aerosol Technik, Germany) by sampling directly from inside the collection chamber while aerosolizing ultrapure water. Data were collected at 6 s intervals over 31 equidistant size channels using software 1179_V2-05 (GRIMM Aerosol Technik, Germany), then summed and averaged over the length of the experiment for each size channel.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

When TEM was required, the fluorescent dye in spray mixtures was substituted with 10 mg·mL–1 ferritin from equine spleen (Sigma-Aldrich) to increase electron density within transformed vesicles. TEM images were acquired with a Phillips’ FEI Morgagni 268 scope, operating at 80 kV, with a Gatan Orius CCD camera using the Gatan Digital Micrograph software (version 1.81.78). Samples were prepared by loading 15 μL of a landing solution that was previously exposed to aerosols and subsequently purified by size exclusion chromatography on carbon-coated grids, with support film, purchased from Ted Pella Inc. (part no: 01753-F, F/C, 300 mesh Cu). The samples were left to settle for 3 min, after which the excess solution was blotted off with filter paper. The samples were then stained with uranyl acetate (4% w/v in distilled water, Fisher) and left to dry before imaging.

Microflow Cytometry

Microflow cytometry was performed using an Apogee A60 MP (Apogee Flow Systems, SN 0130) running Histogram Software v6.0.77 and FCM Control v 3.80. Before sample analysis, the system was cleaned using bleach (1%). Sheath and diluent were checked to ensure machine and diluent cleanliness (event rate < 200 events·s–1). The Apogee platform was calibrated using a bead mixture (ApoCal 1524, lot CAL0134); monitoring beads were also analyzed (Apogee Mix 1527, lot CAL0139) as part of daily protocols. Instrument specifications are provided in Table S1 and Supporting Text. Whenever possible, the solutions used to prepare the samples were filtered through 0.22 μm syringe filters. At least 800,000 events from vesicle samples were captured at a flow rate of 1.5 μL·min–1 using the medium angle light-scatter threshold trigger only (set at 33). For confirmation, some samples were reassayed using fluorescence triggering (638 Red, Alexa Fluor 647 (AF647) channel set to 34). The specific fluorescence threshold value (set to 34) for detecting AF647 positive events was defined by increasing the threshold value while running the diluent (0.2 M bicine, pH 8.0) as a sample. Once the noise events being triggered were suitably low from the diluent, the threshold was decreased to make the noise apparent. This setting was checked against samples of landing solution before and after exposure to aerosols. The apparent noise was used as the “negative” population during analysis. To obtain relative size estimates of the vesicles, their refractive index (RI) was estimated. Refractive index oil emulsion standards (RI 1.36–1.59, Cargille Series AAA) were prepared to generate a continuum of particle sizes. Each emulsion was analyzed separately to define a refractive index curve. The vesicles closely aligned with the Apogee silica beads in the 1527 mixture (180–1300 nm, RI 1.43), as well as comparing closely to the 1.42 and 1.44 Cargille oil emulsion standards. The closeness of the refractive index of the sample to the beads means that the silica is a relatively good but ultimately not an exact match and thus some variation in the size is to be expected.

Results and Discussion

To determine if aerosols could transform into vesicles upon entry into an aqueous solution coated with organic acids and alcohols, we assembled a system that included a nebulizer, flow tube, and collection chamber containing a landing solution (Figures 1B and S1). Aerosols were generated by the interaction of aqueous solution with nitrogen gas at the nozzle of a borosilicate glass nebulizer. The flux of aqueous solution and gas was controlled by pressure and mass flow regulators, respectively. The flow rate of the N2 was 3 standard litres per minute (SLPM), producing a carrier gas velocity of 0.5 m·s–1 at the air–water interface of the landing solution. A water bubbler and a humidity sensor allowed for the precise control of relative humidity, which was set to 60% (Figure S2). An estimation of the size of the aerosols was obtained with an integrated optical particle counter. Aerosols were typically between ≤0.25 and 9.4 μm, with a median of 2.5 μm (Figure S4). The nebulized solution contained lipid and the fluorophore 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (HPTS). The screening of the operating parameters above was with oleate (Figure S5), whereas the remaining experiments were with 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol, 2:1 myristoleic acid/tetradecenol, and 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol. Of these, only the short, saturated lipids (C10:0) decanoic acid and decanol are generally considered prebiotically plausible. Assuming Brownian motion of spherical micellar aggregates with a diameter of 3 nm and vesicular aggregates with a diameter of 1 μm, lipids would require between 1.7 ms and 0.2 s to partition to the air–water interface from the center of aerosol droplets 2.5 μm in diameter (Figure S6, Table S3, and Supporting Text). Less time was likely needed due to the turbulence induced by nebulization. Therefore, the time required (>4 s) to travel the ca. 2 m from the nebulizer to the landing solution was sufficient for the formation of a lipid monolayer. Two min after nebulization, aliquots from the landing solution were collected and analyzed by size exclusion chromatography, fluorescence spectroscopy, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Previous studies demonstrated that vesicles composed of longer-chain fatty acids are more stable than vesicles composed of shorter-chain fatty acids.27−29 Similarly, the addition of fatty alcohol to fatty acid vesicles increases stability.30,31 Therefore, we began by testing whether aerosols containing longer-chain fatty acids and fatty alcohol could transform into vesicles. When an aqueous solution containing the fluorophore HPTS and 20 mM 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol was sprayed into a landing solution containing 0.5 mM 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol, size exclusion chromatography revealed that only 3.7 ± 1.5% of the sprayed anionic fluorophore was within the resulting vesicles as opposed to the external, bulk solution (Figure 2A). Size exclusion chromatography separates large vesicles (and encapsulant) from later eluting unencapsulated, free fluorophore.32,33 Quantification by fluorescence spectroscopy reveals, in this case, the efficiency of conversion from aerosols to vesicles. Lower concentrations of lipid in the aerosol spray led to decreased transformation efficiency. For example, when the concentration of lipid in the spray solution was decreased from 20 to 0.5 mM, the transformation efficiency dropped eightfold to 0.5 ± 0.1%, close to the 0.2 ± 0.1% obtained when spraying aqueous solution without lipid present. The concentration of lipid in the landing solution was above the critical aggregate concentration (CAC) (Figure S7 and Table S2) to disfavor the disassembly of formed vesicles.34,35

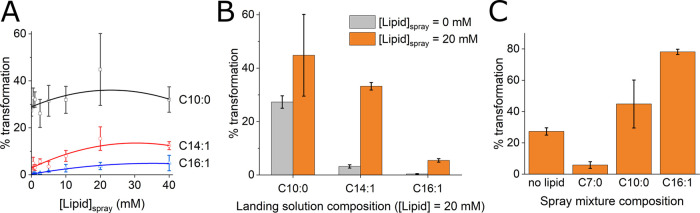

Figure 2.

Effect of lipid composition on aerosol to vesicle transformation efficiency. (A) Aerosol to vesicle transformation efficiency as a function of lipid concentration in the spray solution for lipids of different chain lengths. The composition of the landing solutions was 20 mM C10:1, 1.0 mM C14:1, and 0.5 mM C16:1. Data were fit with a second-order polynomial. (B) Impact of chain length when all landing solutions contained 20 mM lipid. (C) Effect of aerosol lipid composition when landing in 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol. The concentration of lipid in the spray and landing solutions was 20 mM. For all panels, landing and spray solutions always contained 0.2 M bicine, pH 8.0. C7:0, C10:0, C14:1, and C16:1 indicate heptanoic acid, 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol, 2:1 myristoleic acid/tetradecenol, and 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol, respectively. Spray solutions contained 10 mM HPTS. Data are average ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments.

Although shorter-chain lipids form less stable vesicles, the transformation efficiency of aerosols containing lipids two carbons shorter, i.e., 2:1 myristoleic acid/tetradecenol, was improved with respect to aerosols containing 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol when landing in a solution of equivalent composition. Aerosols with 20 mM 2:1 myristoleic acid/tetradecenol transformed fourfold more efficiently than aerosols containing 20 mM palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol (Figure 2A). Aerosols with 2:1 myristoleic acid/tetradecenol also showed a dependence of transformation efficiency on the concentration of lipid (Figure 2A). Greater concentrations of lipid in the aerosols led to the formation of more vesicles in the landing solution until a concentration of 20 mM. The transformation efficiency at 20 and 40 mM lipid within the aerosols was within error. The increased efficiencies at higher concentrations may have reflected the amount of lipid required for the formation of a monolayer. For example, if the footprint of one molecule of myristoleic acid (or tetradecenol) was taken to be 20 Å2,7,36,37 approximately 9.8 × 107 lipid molecules would be needed to form a monolayer at the air–water interface of a 2.5 μm spherical aerosol particle (Supporting Text and Table S4). Forty millimolar 2:1 myristoleic acid/tetradecenol equalled 2 × 108 molecules within the 8.2 fL of a 2.5 μm aerosol particle, which was sufficient for the formation of a monolayer (Table S4 and Figure S8). Concentrations lower than 20 mM were insufficient for covering the entire surface of a 2.5 μm aerosol particle.

Consistent with a trend of shorter lipids better mediating transformation into vesicles, the prebiotically plausible 10-carbon lipids, i.e., 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol, gave the highest efficiency of transformation. 45 ± 15% of aerosols containing 20 mM 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol transformed into vesicles when landing in a solution containing the same composition of lipid, which was 3-fold and 12-fold greater than 2:1 myristoleic acid/tetradecenol and 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol, respectively (Figure 2A). However, unlike longer-chain lipids, 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol did not show a dependence on lipid concentration within the aerosols for transformation into vesicles (Figure 2A). This was true even when the number of lipid molecules was not sufficient for the formation of a monolayer at the air–water interface of the aerosols (Table S4 and Figure S8). This suggested, at least for the case of 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol, that the lipid composition of the landing solution was more important than the composition of the aerosol and also argued against the aerosols predominantly functioning as a carrier of preformed vesicles. Not only did aerosols with concentrations of lipid below the CAC transform into vesicles but also even aerosols without any lipid at all efficiently gave rise to vesicles when landing in 20 mM 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol (Figure 2A–C), which was not the case for landing solutions with lipids of longer chain length (Figures 2B and S9). The formation of vesicles was dependent on the aerosols since the addition of fluorophore without nebulization to a solution containing 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol did not lead to the appearance of vesicles with encapsulated fluorophore (Figure S10).

To gain more insight into the role of the lipids in the landing solution, the concentration of lipid in the aerosols was held constant while varying the concentration of lipid in the landing solution. Contrary to what was observed with varied concentrations of lipid within the aerosols, a clear dependence was observed, with increased concentration of 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol in the landing solution leading to increased transformation efficiency (Figure S11). The effect of lipid concentration of the landing solution left open the possibility that the observed increase in transformation efficiency with 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol with respect to the longer-chain lipids was due to the different concentrations of lipid used as opposed to the intrinsic properties of the lipids. Landing solutions were originally formulated to contain lipid above the CAC to maintain the integrity of any vesicles that formed from aerosols and to possess sufficient lipid to form a monolayer at the air–water interface of the landing solution. Therefore, concentrations ranged from 0.5 mM for 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol to 20 mM for 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol. The lower end, i.e., 0.5 mM lipid, still provided more than 80-fold more molecules than necessary to form a monolayer at the air–water interface of the 0.015 m2 surface of the 20 mL landing solution (Table S5).

To better decipher whether lipid concentration or composition was important for the transformation of aerosols into vesicles, the concentration of lipid was set to 20 mM for both the aerosols and landing solutions for different lipid compositions. The data clearly showed that transformation efficiency increased with shorter chain, prebiotically plausible lipids (Figure 2B). Under the same conditions, 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol gave rise to eightfold more vesicles than 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol. The differences in transformation efficiency were even more striking when the aerosols completely lacked lipid and the landing solutions contained 20 mM lipid (Figure 2B). Aerosols that lacked lipid only contained the buffer bicine, Na+, and the fluorophore HPTS. Here again, shorter-chain lipids were better able to convert aqueous aerosol droplets to vesicles. Landing solutions containing 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol converted 8.5-fold and 75-fold more aerosols into vesicles than 2:1 myristoleic acid/tetradecenol and 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol, respectively. To assess the impact of fatty alcohol on transformation efficiency, the fraction of decanol was varied. Pure decanoic acid and pure decanol in the landing solution failed to transform aerosols into vesicles. Conversely, 10–40 mol % decanol (Figure S12), consistent with compositions that form more stable vesicles, showed maximal conversion of aerosols to vesicles.

The data suggested that the lipid composition of the landing solution impacted the transformation efficiency more than the composition of the aerosol and that shorter-chain lipids in the landing solution were particularly well suited for the conversion of aerosols to vesicles. This was likely due to the organization and structure of the lipids at the air–water interface. Surface-specific vibrational sum-frequency generation spectroscopy has previously shown that longer-chain lipids pack tightly at the air–water interface in a crystal-like array, whereas shorter-chain lipids are oriented much more heterogeneously.38 Therefore, longer-chain lipids provide a more rigid, more hydrophobic, and more difficult to traverse barrier into aqueous solution, particularly for incoming aqueous aerosol droplets that lack lipid. Similarly, shorter-chain lipids are more dynamic than longer-chain lipids39,40 and thus would be expected to better accommodate the rearrangements necessary for the formation of a lipid bilayer around the incoming aerosol particle.

If true, then the ideal characteristics of the lipids within the aerosol would be expected to be different from the landing solution. That is, longer-chain lipids that form a more rigid structure would be expected to efficiently transform into vesicles upon entry into a solution containing a more malleable interface consisting of shorter-chain lipids. To test this hypothesis, aerosols containing 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol were sprayed into a landing solution containing 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol. In this case, we observed greatly increased transformation efficiency, with 78 ± 1.6% of the aerosol particles converting to vesicles (Figures 2C and S13). As a control, heptanoic acid, a lipid that does not form vesicles,41 was sprayed into the same landing solution of 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol. Here, only 5.8 ± 2.1% of the aerosols transformed into vesicles.

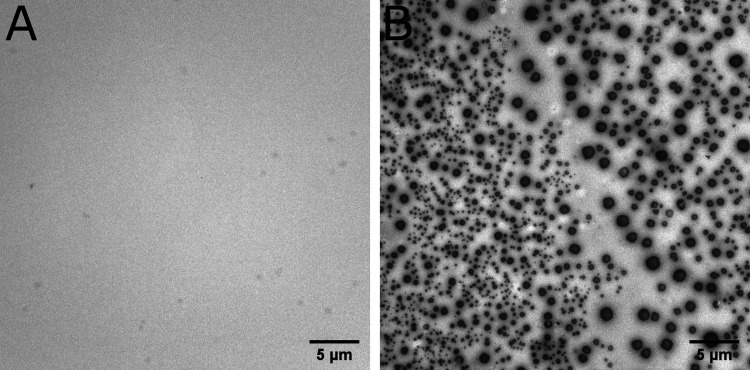

Since longer-chain lipids have a lower CAC, we took advantage of the disparity in lipid concentration between vesicles and bulk solution to acquire images by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Here, 2:1 oleic acid/octadecenol was used in the spray solution so that the resulting vesicles could be purified away from excess lipid by size exclusion chromatography. Vesicles were only observed in the purified landing solution after contact with the aerosols, with a size distribution between 0.2 and 1.75 μm (Figures 3, S14, and S15). Visualization relied on the increased electron density provided by encapsulated ferritin and staining with uranyl acetate. Ferritin alone did not give rise to the formation of spherical structures (Figure S16). Although the presence of lipid vesicles was clear when aerosols were sprayed into landing solutions, it was not possible to determine their lamellarity since the electron density of the encapsulated ferritin provided higher contrast than the membranes. Nevertheless, both unilamellar and multilamellar vesicles have been used as model protocells with each providing specific advantages.42,43 The range of vesicle sizes was consistent with the size of the sprayed aerosols. However, a greater fraction of small vesicles was observed by TEM in comparison to aerosols by light scattering. It is unclear if these differences were due to transformation efficiencies or to the staining procedure required for TEM. To further quantify the size distribution of transformed vesicles, high-resolution microflow cytometry was carried out on an aliquot of landing solution containing 20 mM 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol after exposure to 20 mM 2:1 oleic acid/octadecenol aerosols loaded with 0.6 mM Alexa Fluor 647. The observed relative size estimates were consistent with the TEM data, showing a large number of vesicles less than 180 nm in diameter with the presence of larger vesicles greater than 590 nm (Figure S17).

Figure 3.

Negative-stained TEM images at 2200× magnification of a landing solution purified by size exclusion chromatography before (A) and after (B) contact with aerosols. The landing solution contained 20 mM 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol. Aerosols possessed 20 mM 2:1 oleic acid/octadecenol and 10 mg·mL–1 ferritin. Both solutions were in 0.2 M bicine, pH 8.0.

Conclusions

The conversion of aerosols to vesicles with our laboratory setup is efficient, revealing potential environmental processes that have largely not been investigated. Although we sought to probe the role of aerosols in prebiotic chemistry, the types of fatty acids used in this study are common constituents of contemporary aerosols. Similar studies exploiting solution conditions that mimic the contemporary environment may reveal previously unexplored effects of natural and anthropogenic aerosols on our planet.

Today, water covers 70% of the Earth’s surface and is a major source of chemically diverse aerosols in the troposphere and stratosphere.44,45 On the prebiotic Earth, 90% of the surface is thought to have been covered by oceans, indicating that much of the generated aerosols settled back into aqueous solution. These aerosols would have contributed to the mixing and transport of molecules through anemochory, or dispersal by wind. Here, fluorophore was used as a proxy for the transport of molecules from one aqueous solution to another. In addition to transporting cargo, aerosols can function as a medium for chemical synthesis, as previously seen with the phosphorylation of nucleosides46,47 and the synthesis of purines and dihydroxy compounds by Miller-like, spark-discharge experiments with aqueous aerosols.48 The more hydrophobic environment at the air–water interface also facilitates the types of dehydration reactions that are pervasive throughout biology, such as the formation of peptide bonds.49,50 At high altitude, aerosols would have been more exposed to UV light and magnetically polarized cosmic rays which would have likely led to further synthesis and a selection for photostable molecules.51−56 Importantly, the ability of aerosols to transport and synthesize the building blocks of life is coupled to a capacity to convert to cell-sized lipid vesicles when in the presence of prebiotic lipids. The resulting protocellular compartments also ensure that the contents of the aerosols are not diluted into the large volume of the landing solution. The ideal landing solutions identified in this study contain decanoic acid and decanol, a lipid composition that gives rise to model protocells that were previously shown to grow, divide, and acquire nutrients.39,42,57,58 Therefore, aerosols are compatible with previous conceptions of protocells and thus may represent a heretofore unexplored pathway that facilitated the emergence of the Earth’s first cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. R. Zhao for helpful discussions and Dr. K. Norton (microscopy facility, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta) for TEM images. The authors thank V. Bizon, P. Crothers, J. Dibbs, and D. Kelm for help in building the experimental setup through machine fabrication and glass blowing (facilities at the Department of Chemistry, University of Alberta). The authors are grateful for support from the Simons Foundation (290358FY19) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) [RGPIN-2020-04375]. F.C. acknowledges a NSERC Undergraduate Student Research Award (USRA-563183-2021).

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online supplementary material. In addition, data are openly available at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7378326.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.2c00328.

Additional calculations; photographs of the experimental setup, borosilicate glass nebulizer, and negative-stained TEM images at different magnifications of transformed vesicles; figures showing flow mixtures used to reach the desired relative humidity, size distribution of aerosols reaching the collection chamber, effect of flow rate and relative humidity on aerosol to vesicle transformation of oleic acid mixtures, theoretical travel time of lipid molecules or structures from the center of an aerosol particle to its air–water interfacial layer, critical aggregate concentrations for lipid mixtures, percentage of the surface covered by lipids for a 2.5 μm aerosol, aerosol to vesicle transformation of a spray solution without lipids, negative control for fluorophore self incapsulation in the landing solution in the absence of aerosols, impact of lipid concentration and composition in the landing solution, aerosol to vesicle transformation efficiency of 2:1 palmitoleic acid/hexadecenol aerosols landing in 2:1 decanoic acid/decanol, size distribution of transformed vesicles in landing solutions taken from TEM images, and microflow cytometry (Figures S1–S17); microflow cytometer settings, critical aggregate concentration of lipid mixtures, estimated molecular diameters of fatty acids and alcohols, surface area covered by lipids of a 2.5 μm aerosol particle, and theoretical surface films available for each landing solution (Tables S1–S5) (PDF)

Author Contributions

S.N. and S.S.M conceptualized research. S.N. designed the experimental apparatus. S.A.S. and M.A.-G. participated in preliminary discussions. S.N., A.B., and F.C. performed research. D.P. carried out microflow cytometry experiments. S.N., A.B., and S.S.M. analyzed data. S.N and S.S.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Griffith E. C.; Tuck A. F.; Vaida V. Ocean–Atmosphere Interactions in the Emergence of Complexity in Simple Chemical Systems. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 2106–2113. 10.1021/ar300027q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuck A. The Role of Atmospheric Aerosols in the Origin Of Life. Surv. Geophys. 2002, 23, 379–409. 10.1023/A:1020123922767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason B. J. Bursting of Air Bubbles at the Surface of Sea Water. Nature 1954, 174, 470–471. 10.1038/174470a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seinfeld J. H.; Pandis S. N.. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson C. M.; Ellison G. B.; Tuck A. F.; Vaida V. Atmospheric Aerosols as Prebiotic Chemical Reactors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 11864–11868. 10.1073/pnas.200366897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungwirth P.; Tobias D. J. Specific Ion Effects at the Air/Water Interface. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 1259–1281. 10.1021/cr0403741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison G. B.; Tuck A. F.; Vaida V. Atmospheric Processing of Organic Aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. 1999, 104, 11633–11641. 10.1029/1999JD900073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson D. J.; Anderson D. Adsorption of Atmospheric Gases at the Air–Water Interface. 2. C 1 −C 4 Alcohols, Acids, and Acetone. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 871–876. 10.1021/jp983963h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gagosian R. B.; Peltzer E. T.; Zafiriou O. C. Atmospheric Transport of Continentally Derived Lipids to the Tropical North Pacific. Nature 1981, 291, 312–314. 10.1038/291312a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duce R. A.; Mohnen V. A.; Zimmerman P. R.; Grosjean D.; Cautreels W.; Chatfield R.; Jaenicke R.; Ogren J. A.; Pellizzari E. D.; Wallace G. T. Organic Material in the Global Troposphere. Rev. Geophys. 1983, 21, 921–952. 10.1029/RG021i004p00921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barger W. R.; Garrett W. D. Surface Active Organic Material in Air over the Mediterranean and over the Eastern Equatorial Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. 1976, 81, 3151–3157. 10.1029/JC081i018p03151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gagosian R. B.; Zafiriou O. C.; Peltzer E. T.; Alford J. B. Lipids in Aerosols from the Tropical North Pacific: Temporal Variability. J. Geophys. Res. 1982, 87, 11133–11144. 10.1029/JC087iC13p11133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tervahattu H.; Juhanoja J.; Kupiainen K. Identification of an Organic Coating on Marine Aerosol Particles by TOF-SIMS. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2002, 107, ACH18-1–ACH18-7. 10.1029/2001JD001403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tervahattu H.; Hartonen K.; Kerminen V.-M.; Kupiainen K.; Aarnio P.; Koskentalo T.; Tuck A. F.; Vaida V. New Evidence of an Organic Layer on Marine Aerosols. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 2002, 107, AAC1-1–AAC1-8. 10.1029/2000JD000282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak J. W.; Bartel D. P.; Luisi P. L. Synthesizing Life. Nature 2001, 409, 387–390. 10.1038/35053176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mirazo K.; Briones C.; de la Escosura A. Prebiotic Systems Chemistry: New Perspectives for the Origins of Life. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 285–366. 10.1021/cr2004844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gözen I.; Köksal E. S.; Põldsalu I.; Xue L.; Spustova K.; Pedrueza-Villalmanzo E.; Ryskulov R.; Meng F.; Jesorka A. Protocells: Milestones and Recent Advances. Small 2022, 18, 2106624 10.1002/smll.202106624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin N.; Douliez J. Fatty Acid Vesicles and Coacervates as Model Prebiotic Protocells. ChemSystemsChem 2021, 3, e2100024 10.1002/syst.202100024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritson D. J.; Battilocchio C.; Ley S. V.; Sutherland J. D. Mimicking the Surface and Prebiotic Chemistry of Early Earth Using Flow Chemistry. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1821 10.1038/s41467-018-04147-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith E. C.; Rapf R. J.; Shoemaker R. K.; Carpenter B. K.; Vaida V. Photoinitiated Synthesis of Self-Assembled Vesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3784–3787. 10.1021/ja5006256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luisi P. L.The Emergence of Life: From Chemical Origins to Synthetic Biology, 2th ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Monnard P.-A.; Walde P. Current Ideas about Prebiological Compartmentalization. Life 2015, 5, 1239–1263. 10.3390/life5021239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oro J. Chemical Synthesis of Lipids and the Origin of Life. J. Biol. Phys. 1995, 20, 135–147. 10.1007/BF00700430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deamer D. W.; Pashley R. M. Amphiphilic Components of the Murchison Carbonaceous Chondrite: Surface Properties and Membrane Formation. Origins Life Evol. Biospheres 1989, 19, 21–38. 10.1007/BF01808285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavin D. P.; Alexander C. M. O.; Aponte J. C.; Dworkin J. P.; Elsila J. E.; Yabuta H.. The Origin and Evolution of Organic Matter in Carbonaceous Chondrites and Links to Their Parent Bodies. In Primitive Meteorites and Asteroids; Elsevier, 2018; pp 205–271. [Google Scholar]

- Pautot S.; Frisken B. J.; Weitz D. A. Production of Unilamellar Vesicles Using an Inverted Emulsion. Langmuir 2003, 19, 2870–2879. 10.1021/la026100v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cape J. L.; Monnard P.-A.; Boncella J. M. Prebiotically Relevant Mixed Fatty Acid Vesicles Support Anionic Solute Encapsulation and Photochemically Catalyzed Trans-Membrane Charge Transport. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 661–671. 10.1039/c0sc00575d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansy S. S.; Szostak J. W. Thermostability of Model Protocell Membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 13351–13355. 10.1073/pnas.0805086105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer S. E.; Deamer D. W.; Boncella J. M.; Monnard P.-A. Chemical Evolution of Amphiphiles: Glycerol Monoacyl Derivatives Stabilize Plausible Prebiotic Membranes. Astrobiology 2009, 9, 979–987. 10.1089/ast.2009.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnard P.-A.; Deamer D. W. Membrane Self-Assembly Processes: Steps toward the First Cellular Life. Anat. Rec. 2002, 268, 196–207. 10.1002/ar.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendón A.; Carton D. G.; Sot J.; García-Pacios M.; Montes L.-R.; Valle M.; Arrondo J.-L. R.; Goñi F. M.; Ruiz-Mirazo K. Model Systems of Precursor Cellular Membranes: Long-Chain Alcohols Stabilize Spontaneously Formed Oleic Acid Vesicles. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 278–286. 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski H. V.; Penas M.; Saunders K. The Study of Lipid Aggregates in Aqueous Solution: Formation and Properties of Liposomes with an Encapsulated Metallochromic Dye. J. Chem. Educ. 1994, 71, 347 10.1021/ed071p347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco C. D.; Torino D.; Mansy S. S. Vesicle Stability and Dynamics: An Undergraduate Biochemistry Laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 2014, 91, 1228–1231. 10.1021/ed400105q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luisi P. L. Are Micelles and Vesicles Chemical Equilibrium Systems?. J. Chem. Educ. 2001, 78, 380 10.1021/ed078p380. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morigaki K.; Walde P.; Misran M.; Robinson B. H. Thermodynamic and Kinetic Stability. Properties of Micelles and Vesicles Formed by the Decanoic Acid/Decanoate System. Colloids Surf., A 2003, 213, 37–44. 10.1016/S0927-7757(02)00336-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pockels A. Surface Tension. Nature 1891, 43, 437–439. 10.1038/043437c0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson A. W.; Gast A. P.. Physical Chemistry of Surfaces, 6th ed.; Wiley: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Seki T.; Yu X.; Zhang P.; Yu C.-C.; Liu K.; Gunkel L.; Dong R.; Nagata Y.; Feng X.; Bonn M. Real-Time Study of on-Water Chemistry: Surfactant Monolayer-Assisted Growth of a Crystalline Quasi-2D Polymer. Chem 2021, 7, 2758–2770. 10.1016/j.chempr.2021.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toparlak Ö. D.; Wang A.; Mansy S. S. Population-Level Membrane Diversity Triggers Growth and Division of Protocells. JACS Au 2021, 1, 560–568. 10.1021/jacsau.0c00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Kamp F.; Hamilton J. A. Dissociation of Long and Very Long Chain Fatty Acids from Phospholipid Bilayers. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 16055–16060. 10.1021/bi961685b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Z. R.; Kessenich B. L.; Hazra A.; Nguyen J.; Johnson R. S.; MacCoss M. J.; Lalic G.; Black R. A.; Keller S. L. Prebiotic Membranes and Micelles Do Not Inhibit Peptide Formation During Dehydration. ChemBioChem 2022, 23, e202100614 10.1002/cbic.202100614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T. F.; Szostak J. W. Coupled Growth and Division of Model Protocell Membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5705–5713. 10.1021/ja900919c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindt J. T.; Szostak J. W.; Wang A. Bulk Self-Assembly of Giant, Unilamellar Vesicles. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 14627–14634. 10.1021/acsnano.0c03125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D. M.; Thomson D. S.; Mahoney M. J. In Situ Measurements of Organics, Meteoritic Material, Mercury, and Other Elements in Aerosols at 5 to 19 Kilometers. Science 1998, 282, 1664–1669. 10.1126/science.282.5394.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrook A. M.; Murphy D. M.; Thomson D. S. Observations of Organic Material in Individual Marine Particles at Cape Grim during the First Aerosol Characterization Experiment (ACE 1). J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103, 16475–16483. 10.1029/97JD03719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda A. D.; Li Z.; Joo T.; Benham K.; Burcar B. T.; Krishnamurthy R.; Liotta C. L.; Ng N. L.; Orlando T. M. Prebiotic Phosphorylation of Uridine Using Diamidophosphate in Aerosols. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13527 10.1038/s41598-019-49947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam I.; Lee J. K.; Nam H. G.; Zare R. N. Abiotic Production of Sugar Phosphates and Uridine Ribonucleoside in Aqueous Microdroplets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 12396–12400. 10.1073/pnas.1714896114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Bermejo M.; Menor-Salván C.; Osuna-Esteban S.; Veintemillas-Verdaguer S. Prebiotic Microreactors: A Synthesis of Purines and Dihydroxy Compounds in Aqueous Aerosol. Origins Life Evol. Biospheres 2007, 37, 123–142. 10.1007/s11084-006-9026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith E. C.; Vaida V. In Situ Observation of Peptide Bond Formation at the Water-Air Interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 15697–15701. 10.1073/pnas.1210029109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Qiao L.; He J.; Ju Y.; Yu K.; Kan G.; Guo C.; Zhang H.; Jiang J. Water Microdroplets Allow Spontaneously Abiotic Production of Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 5774–5780. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c01083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapf R. J.; Vaida V. Sunlight as an Energetic Driver in the Synthesis of Molecules Necessary for Life. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 20067–20084. 10.1039/C6CP00980H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Globus N.; Blandford R. D. The Chiral Puzzle of Life. Astrophys. J., Lett. 2020, 895, L11 10.3847/2041-8213/ab8dc6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janicki M. J.; Roberts S. J.; Šponer J.; Powner M. W.; Góra R. W.; Szabla R. Photostability of Oxazoline RNA-Precursors in UV-Rich Prebiotic Environments. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 13407–13410. 10.1039/C8CC07343K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Wu L.-F.; Kufner C. L.; Sasselov D. D.; Fischer W. W.; Sutherland J. D. Prebiotic Photoredox Synthesis from Carbon Dioxide and Sulfite. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 1126–1132. 10.1038/s41557-021-00789-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfio C.; Valer L.; Scintilla S.; Shah S.; Evans D. J.; Jin L.; Szostak J. W.; Sasselov D. D.; Sutherland J. D.; Mansy S. S. UV-Light-Driven Prebiotic Synthesis of Iron–Sulfur Clusters. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 1229–1234. 10.1038/nchem.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton C. T.; de La Harpe K.; Su C.; Law Y. K.; Crespo-Hernández C. E.; Kohler B. DNA Excited-State Dynamics: From Single Bases to the Double Helix. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2009, 60, 217–239. 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansy S. S.; Schrum J. P.; Krishnamurthy M.; Tobé S.; Treco D. A.; Szostak J. W. Template-Directed Synthesis of a Genetic Polymer in a Model Protocell. Nature 2008, 454, 122–125. 10.1038/nature07018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Flaherty D. K.; Kamat N. P.; Mirza F. N.; Li L.; Prywes N.; Szostak J. W. Copying of Mixed-Sequence RNA Templates inside Model Protocells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5171–5178. 10.1021/jacs.8b00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online supplementary material. In addition, data are openly available at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7378326.